1. Introduction

Females around the world have many preconceived notions and misconceptions about menstruation and this topic is considered a taboo for discussion. Although we assume that educated women and college-going girls have the basic knowledge and positive attitude towards this natural phenomenon and follow healthy and hygienic habits, we may be wrong. Adolescent girls in low- and middle-income settings follow myths, taboos, and socio-cultural restrictions, creating barriers to acquiring accurate information about menstruation. The failure to fully acknowledge the physical reality of women has a range of serious impacts alongside experiences of shame [

1]. This limits their daily and routine activities, and in most cases, adult women themselves are unaware of the biological facts of menstruation or the good hygienic practices required, instead, they pass on cultural taboos and restrictions to be observed [

2,

3,

4,

5].

The management of menstruation is a public health issue since the cumulative duration of menstruation represents almost eight years of a woman’s entire life span [

6]. Menstrual hygiene (MH) practices depend on factors such as geographic origins, cultural and socioeconomic influences, education, and information received. The choice and use of products such as type of sanitary protection, also depend on multiple factors specific to each woman (e.g., menstrual flow, duration of menstrual period, and personal preferences) [

7,

8,

9]. Incorrect MH practices also pose health hazards like urinary and reproductive tract infections, which can have both short and long-term health implications [

10].

The population in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) consists of different nationalities, religions, and cultures. No study is done in UAE to assess the Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice (KAP) of MH. In a recent study in UAE, it was found that mothers of girls with a disability commonly seek medical help to delay/halt puberty due to concerns about MH [

11].

The Middle East and Central Asia Guidelines on Female Genital Hygiene only mentions sanitary napkins, menstrual cup, and tampons as menstrual hygiene products with their usage guidance [

12].

Having comprehensive evidence on the KAP of MH in a multicultural community will help us to compare the beliefs, practices, and taboos. This will help us formulate awareness strategies and help the community as a whole.

This study is aimed at assessing the KAP of MH among the female students and faculty of RAK Medical and Health Sciences University (RAKMHSU) in the UAE.

Research Question:

1) What is the level of knowledge of menstrual hygiene, attitude about menses, and practices of MH among the females in a medical and health sciences University?

2) Is there a difference between faculty and students in the KAP measures for MH?

2. Materials and Methods

This is an observational, cross-sectional questionnaire survey conducted among the students, and faculty of all constituent colleges of RAKMHSU between February and June of 2023. The ethical approval was obtained from the RAKMHSU Research and Ethics Committee [RAKMHSU-REC-167-2022/23-F-M]. Consecutive sampling was used to include all the eligible persons.

Study setting

This study is done among the faculty and students of RAK Medical and Health Sciences University, Ras Al Khaimah, United Arab Emirates, constituting of RAK College of Medical Sciences, RAK College of Nursing, RAK College of Dentistry and RAK College of Pharmacy.

Study Participants

Inclusion criteria included all female faculty, staff and students of RAKMHSU. Exclusion criteria 1. Male faculty and staff 2. Women who are postmenopausal.

Power analysis using Sample Size Calculator software available at Calculator.net was carried out to determine the required sample size. In this study, the significance level (α) for p-values was set at 5%; population size at 600, and confidence intervals (CI) at 95%. This calculation provided the minimum required sample size (n = 245) that is to be recruited to generate adequately sized subgroups to ensure the statistical robustness of analyses.

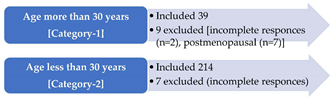

For the convenience of comparison, the participants were divided into 2 categories; those who are less than 30 years of age, and those who are 30 years of age or older.

Data Collection

All female students and faculty meeting the criteria were approached for informed consent. Once they agreed and gave written consent, the questionnaire was used to collect responses.

A structured questionnaire was used to collect the responses. Data was collected between February and June of 2023.

Study instrument

The researchers followed the guideline for developing a questionnaire [

13] and prepared a structured self-administered questionnaire based on the available literature [

14,

15]. It was then validated in a pilot group. The initial version of the questionnaire was prepared after a review of the relevant literature [

14,

15]. It contained 32 items (Questionnaire version 1). We invited faculty members (N=10) from the institution to screen the questionnaire for content. We then invited 10 other participants to test the questionnaire for general readability and comprehension. We tested the overall reliability and the Cronbach α obtained was 0.78, suggestive of acceptable internal consistency. The final Questionnaire consisted of 21 questions including the demographic data of students & faculty, characteristics of their menstrual cycle (2 questions), items related to KAP related to menstruation (10 questions), and items related to MH products (9 questions).

Data analysis

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 24.0 was used for data analysis. Descriptive statistics (percentage) and univariate analysis was used to describe the characteristics of the respondents. A bivariate analysis using a chi-square test was done for the comparisons and a p-value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Profile of Participants

In this study, two age categories (less than 30 years and more than 30 years) were used. The 1st category mainly included female faculty and the 2nd category included students.

A total of 253 females participated in the survey, the majority being students and less than 30 years of age [

Table 1]. The participants were from all 4 constituent colleges of RAKMHSU [College of Medicine, Nursing, Pharmacy and Dentistry]. 94.5% of category-1 were postgraduates (n=37) and 92% (n=197) of category-2 were undergraduates.

The majority of participants in each category were from the Middle east and Africa (30%) Followed by Indians (25.8%). All the participants were literate and of middle to higher socioeconomic status.

3.2. Menstrual History

In this section, the age of the onset of first menstruation (menarche), the menstrual pattern, and pain during menstruation among the participants are discussed. The answers in ranges are put to identify abnormalities in menstruation if present. When abnormalities were found, participants were counseled and referred for consultation in the health care facility.

The age of the menarche among the respondents in both categories was between 11-15 years and the duration of bleeding was between 2-7 days. The categories did not also significantly differ regarding cycle length. However, cycles were regular (94.9%), not associated with dysmenorrhea (69.2%), and did not significantly affect day-to-day life (79.4%) in older women compared to women less than 30 years of age. Younger women perceived their cycle to be heavy significantly more than older women (p<.05) [

Table 2].

Table 2.

Menstrual History.

Table 2.

Menstrual History.

3.3. Knowledge about menstrual hygiene

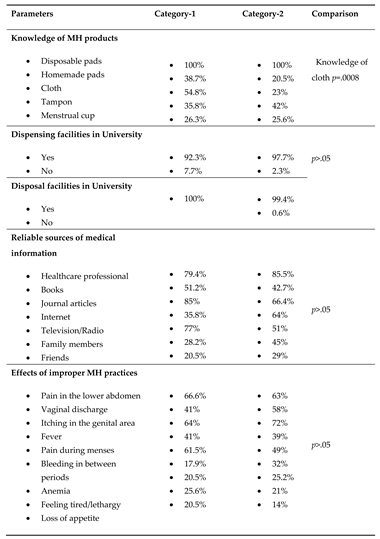

Sanitary measures available

All the participants were well aware of disposable sanitary pads as a product used during menstruation (100%). The knowledge of the homemade pads, cloth, and menstrual cup was limited in general in all participants. The older women were significantly more aware of menstrual cloth then the females under 30 years of age (p<.05) [

Table 3].

Table 3.

Knowledge of MH.

Table 3.

Knowledge of MH.

Disposal and Dispensing facilities in the university

All the participants were well aware of these facilities available in the university, although older women were less aware of dispensing units in the university.

Reliable sources for medical information

The most reliable source of information for participants were physicians and health care providers followed by journal articles. While women in category-1 preferred books and television more than the younger women, the latter relied on the internet as a source of information. However, the differences were not statistically significant.

Implications of improper menstrual hygiene practices

Almost everyone had some knowledge of the implications of improper MH, it was inadequate. The features of genital infection were known to participants in both categories but more than 70 % were unaware of dysmenorrhea, intermenstrual bleeding, lethargy and anemia as the consequences.

3.4. Attitude regarding menses and menstrual hygiene

Reaction when first menstruated

While the most common reaction was being scared and telling another female in the household like mother, grandmother, or sister, almost 10%-15% did not remember their first reaction. Most of the participants have mixed interplay of reactions. Women younger than 30 years were significantly more annoyed than women above 30 years, whereas older women were significantly more embarrassed and happy [

Table 4].

Table 4.

Attitude of menstruation and MH.

Table 4.

Attitude of menstruation and MH.

Is menstrual blood unhygienic?

The attitude was mixed with almost 1/3rd of women in each category thinking menstrual blood to be unhygienic. There was however no difference between the two categories of women in their attitudes.

Is menstruation a personal/ female matter?

More women above the age of 30 years had the opinion that menstruation is a female/ personal matter, to be kept to oneself only, not to talk about openly. Younger women were more open to talking about it. The difference was statistically significant (p=.0005).

Do you feel menstruation is very annoying and you are just tolerating menses?

Almost half of the women under 30 years (48.9%) perceived menstruation as annoying. Younger women were significantly more likely to think that they are only tolerating menstruation than older women (p=.003).

3.5. Practice of menstrual hygiene

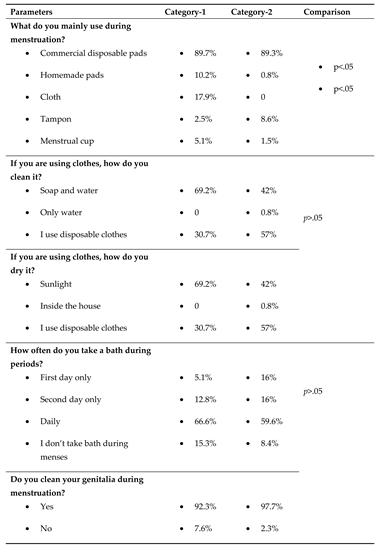

Use of products, cleaning and drying

Commercially available disposable sanitary pads were most commonly used by women irrespective of age (89-90%). Tampons were preferred by younger women and menstrual cups were preferred by older women, but the absolute use is less as compared to pads. The difference was not statistically significant. However, menstrual cloth was exclusively used by women above 30 years of age, and homemade pads were significantly more used in older women compared to younger women [

Table 5].

Although the use of reusable material is very limited in this study, when participants were asked about cleaning and drying, should they be using a reusable one, everyone agreed on washing with soap and water with sun drying.

Taking a bath during menses and cleaning

The result is mixed with the majority of women agreeing that they take baths daily during menses. 8% of younger women and 15% of older women do not take baths during their periods. There was almost an equal proportion of females taking a bath only on the 1st or 2nd day. Almost all the participants in our study (>90%) clean the genitalia regularly during menses and wash their hands before and after changing sanitary measures. There was no statistically significant difference between the groups regarding this.

Frequency of changing

The majority of participants use disposable sanitary pads and change them 3 or more times a day as required. Those who used menstrual clothes and homemade pads are used to changing it more often, whereas those using tampons change it twice daily. There were 3 participants using menstrual cups in our study, and it is changed once or twice daily as required.

Disposal and Use of university facilities

With the exception of those participants using menstrual cups and reusable measures, almost all the participants use dedicated bins for disposal, toilet bins when such bins are unavailable, and none in the toilet or outside. However, the preference for paper or plastic is equal among participants. These results are not different among the groups. The “others” belong to those using reusable measures. The university disposal and dispensing facilities are used by the majority of participants either always or sometimes. 15% of women in category-1 and 4% in Category 2 had never used these facilities.

4. Discussion

Menstruation is a normal physiological process and MH practice is an essential component of health in females.

This study was done at a medical and health sciences university, and anatomy and physiology of menstruation is a part of the curriculum. Hence, these questions although initially a part of version-1 of the questionnaire, were not included. This is in contrast with other studies done among students where knowledge of menstruation was assessed [

16,

17].

Our study indicates normal menstrual history in the majority of the participants including menarche and characteristics of cycle. This is in accordance with the studies in South Asian, middle eastern, and African countries having similar populations [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. Furthermore, more than half of the women had dysmenorrhea. It is similar to other studies in the same age group [

17,

23].

The knowledge about MH in our study was good, this being a medical and health sciences university. However, the younger women were relatively unaware of menstrual clothes and older women were relatively unaware of menstrual cups. No single material product is likely to be preferred by all females always and the preferences vary due to different reasons. In our study the knowledge and use of menstrual cups as well as cloth are minimal.

Menstrual cloth- These are fabric pieces (new or old) worn externally, in underwear or tied to the waist. It can usually be reused for up to 1 year. It is cheap, environment friendly, and universally available. Proper washing and drying are crucial for safe use, to avoid abnormal vaginal discharge, skin irritations, and urogenital infections. When single-use clothes are used, proper disposal facilities are essential [

24].

Reusable pad- Reusable pads are worn externally in underwear, and held in place usually by snaps. They can be reused for approximately one year. Proper washing and drying are crucial for safe use. Improper use is associated with skin irritation, urinary tract infections, and bacterial vaginosis. They produce significantly less solid waste than single-use, disposable materials [

24].

Disposable sanitary pads- Disposable pads are worn externally to the body, and are available in most places. They are disposed of after a maximum of 8 hours or earlier if required. They are often preferred as they are reliable, hygienic, comfortable, easy to use and do not require to be cleaned. As pads are disposed of after one use, proper disposal facilities are essential. Affordable, high-quality biodegradable disposable pads are the need of the hour but not readily available [

24].

Tampons- Tampons are absorbent materials that are inserted into the vagina. They expand by absorbing menstrual flow and also avoid leakage. They can be worn maximum for up to 8 hours, after which they are removed, and disposed of. They can be worn with an intrauterine device. The prevalence of its use is low due to fear of pain, fear of tampon getting stuck and sociocultural barriers as they have to be inserted into the vagina. Tampon use is associated with toxic shock syndrome, a rare but potentially fatal disease, especially if not changed on time. Acceptability is gradually increasing with proper education and discussions. Soap for handwashing and access to clean water is important to avoid UTIs and vaginal infections. They create large amounts of waste as they need to be disposed of after single use [

24].

Menstrual cup- The menstrual cup is a non-absorbent bell-shaped device made of silicon that is inserted into the vagina to collect menstrual flow. It creates a seal and is held in place by the walls of the vagina. It collects three times more blood than pads or tampons and needs to be rinsed and re-inserted every 6-12 hours. After each menstrual cycle the cup must be boiled for 5-10 minutes. These cups can be reused for 5-10 years. Use is low due to fear and sociocultural issues but there is increasing interest on the acceptability of cups as convenient, environmentally friendly option. Menstrual cups are perceived as better than pads or cloths due to ease and discretion of washing, drying and storing, comfort, leakage protection, odour development, quality and length of wear. No underwear is needed for its use. Based on literature from high- and low-income countries, no significant health risks like toxic shock syndrome, infections and skin irritations are reported, since they do not disrupt vaginal flora and pH. They can be worn with an intrauterine device. The amount of water required for boiling, is far less than reusable pads or clothes [

24].

The knowledge about the implications of improper MH was also not adequate. While Urinary tract infection and reproductive tract infections were well recognized as complications of poor MH manifested by vaginal discharge, itching in the vulva, lower abdominal pain, and sometimes fever. Improper MH practices can lead to menstrual abnormalities and, anemia manifested by tiredness and loss of appetite [

25]. This can also lead to long-term consequences like chronic pelvic pain and subfertility.

In our study, women younger than 30 years were significantly more annoyed than women above 30 years, whereas older women were significantly more embarrassed. This can be due to the fact that the older were more likely to be unaware of menstruation at the time of their menarche. The prevalence of dysmenorrhea and irregular menses is higher in younger women in our study, favoring the feeling of annoyance in a set up high-stress educational environment like a University.

A third of the participants in our study perceived menstrual blood as unhygienic. This may be due to deep-rooted social and cultural beliefs. The physiology of menstruation is well known for a very long period of time. Therefore, there seems no reason for this notion to persist that menstruation is unhygienic or that menstruating women are “impure” [

26]. Cultural norms and religious taboos on menstruation are often compounded by traditional associations with evil spirits, shame and embarrassment surrounding sexual reproduction [

27,

28,

29]. Gender discrimination also plays a part in the belief of menstruation or female reproductive issues as impure [

30]. This can also explain the reluctance of participants to talk about it openly and perceive it as personal or female matter. The younger women in our study felt significantly less likely to think so and are open about talking about it.

Most of the participants in our study used commercially available disposable products. This is in accordance with an analysis carried out by FSG in 2016 showing over 75% of women and girls in high- and upper-middle-income countries use commercially produced products [

31]. A study in Korea among nurses also showed that 89% use disposable sanitary pads and use of menstrual cups in only 1.6% of participants [

32].

Participants were well aware of the importance of proper cleaning and drying of reusable products in our study. There are considerable differences of practice regarding taking a bath during menses. There is no clear evidence in the literature regarding this. While sharing a bath is considered not acceptable due to deep-rooted beliefs of impure blood, it is important to maintain hygiene during menses [

33,

34]. Around 66% of women in our study reported that they take a bath daily during menses. This is in accordance with other studies from Afghanistan, India, Pakistan, and Africa [

17,

18,

35,

36]. As long as the genital area is regularly cleaned, hand wash hygiene is maintained and products are cleaned/ changed regularly following the recommended time period, MH can be maintained.

There are a few other studies showing beliefs about menstruation among students affecting the MH practices [

37]. A study in Nepal indicates factors influencing MH KAP were cultural beliefs, stigma, poverty, and illiteracy. Various qualitative studies also point to cultural beliefs as the cornerstone of MH practices [

16]. However, in our study, the beliefs are not explored and poverty and illiteracy did not play a role in the KAP measures.

5. Conclusions

As this study was carried out in a medical and health sciences University, good knowledge and practices of MH were expected. This study revealed differences in menstrual history and attitude among older and younger women. The attitude and beliefs vary among the participants, due to sociocultural factors and age differences, despite being in medical and health sciences. Physicians and healthcare providers play a vital role in providing appropriate evidence-based knowledge about healthy practices and overcoming taboos.

Supplementary Materials

Questionnaire

Author Contributions

Rajani Dube (RD), and Huma Zaidi (HZ) contributed to the research in the following roles-Conception and design of the study: RD, HZ. Proposal writing: HZ, RD. Acquisition of data: HZ, RD. Analysis and/or interpretation of data: RD. Drafting the manuscript: RD, HZ. Revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content: RD, HZ. Approval of the version of the manuscript to be Published: HZ, RD.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of the Ministry of Health and Prevention, UAE. Approval number- RAKMHSU-REC-167-2022/23-F-M

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data is available with the corresponding author and can be provided on reasonable request. It has not been deposited in any repository.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Goldblatt, B.; Steele, L. Bloody unfair: inequality related to menstruation — considering the role of discrimination law. SSRN Electron J. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House S, Mahon T, Cavill S. Menstrual hygiene matters: A resource for improving menstrual hygiene around the world. First Edit. London, UK: WaterAid; 2012. 1–354 p. 3.

- Morrison J, Basnet M, Bhatta A, Khimbanjar S, Baral S. ANALYSIS OF MENSTRUAL HYGIENE PRACTICES IN NEPAL: The Role of WASH in Schools Programme for Girls Education 2016. Nepal; 2018.

- Mohammed, S.; Larsen-Reindorf, R.E. Menstrual knowledge, sociocultural restrictions, and barriers to menstrual hygiene management in Ghana: Evidence from a multi-method survey among adolescent schoolgirls and schoolboys. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0241106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WaterAid. Is menstrual hygiene and management an issue for adolescent school girls? WaterAid/Anita Pradhan A comparative study of four schools in different settings of Nepal [Internet]. Kupondole, Lalitpur, Nepal; 2009. Available online: www.wateraid.org/nepal.

- Gavrilyuk, O.; Braaten, T.; Weiderpass, E.; Licaj, I.; Lund, E. Lifetime number of years of menstruation as a risk index for postmenopausal endometrial cancer in the Norwegian Women and Cancer Study. Acta Obstet. et Gynecol. Scand. 2018, 97, 1168–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romo, L.F.; Berenson, A.B. Tampon Use in Adolescence: Differences among European American, African American and Latina Women in Practices, Concerns, and Barriers. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2012, 25, 328–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czerwinski, B.S. Variation in Feminine Hygiene Practices as a Function of Age. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2000, 29, 625–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerwinski, B.S. Adult feminine hygiene practices. Appl. Nurs. Res. 1996, 9, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabwera, H.M.; Shah, V.; Neville, R.; Sosseh, F.; Saidykhan, M.; Faal, F.; Sonko, B.; Keita, O.; Schmidt, W.-P.; Torondel, B. Menstrual hygiene management practices and associated health outcomes among school-going adolescents in rural Gambia. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0247554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deeb, A.; Akle, M.; Al Zaabi, A.; Siwji, Z.; Attia, S.; Al Suwaidi, H.; Al Qahtani, N.; Ehtisham, S. Maternal attitude towards delaying puberty in girls with and without a disability: a questionnaire-based study from the United Arab Emirates. BMJ Paediatr. Open 2018, 2, e000306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arab H, Almadani L, Tahlak M, Chawla M, Ashouri M, et al. The Middle East and Central Asia Guidelines on Female Genital Hygiene. REPRINTED FROM BMJ ME. 2011;19:99-106.

- Artino, A.R., Jr.; La Rochelle, J.S.; DeZee, K.J.; Gehlbach, H. Developing questionnaires for educational research: AMEE Guide No. 87. Med Teach. 2014, 36, 463–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upashe, S.P.; Tekelab, T.; Mekonnen, J. BMC Women's Health. BMC Women’s Heal. 2015, 15, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.-U.; Luby, S.P.; Halder, A.K.; Islam, K.; Opel, A.; Shoab, A.K.; Ghosh, P.K.; Rahman, M.; Mahon, T.; Unicomb, L. Menstrual hygiene management among Bangladeshi adolescent schoolgirls and risk factors affecting school absence: results from a cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e015508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, S.; Bhattarai, S.; Aro, A.R. ’Menstrual blood is bad and should be cleaned’: A qualitative case study on traditional menstrual practices and contextual factors in the rural communities of far-western Nepal. SAGE Open Med. 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakhi, R.; Jalalzai, S.; Ahmadi, Z.; Almaszada, R.; Zarghoon, F.N.; Mohammadi, R.; Ahmad, H.; Mazhar, S.; Faqirzada, M.; Hamidi, M. Knowledge, Beliefs, and Practices Related to Menstruation Among Female Students in Afghanistan. Int. J. Women’s Heal. 2023, ume 15, 1139–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansoor, H.; Salman, M.; Asif, N.; Mustafa, Z.U.; Nawaz, A.S.; Mohsin, J.; Arif, B.; Sheikh, A.; Hira, N.E.; Shehzadi, N.; et al. Menstrual knowledge and practices of Pakistani girls: A multicenter, cross-sectional study. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adinma, E.D.; Adinma, J.I.B. Perceptions and practices on menstruation amongst Nigerian secondary school girls. Afr. J. Reprod. Heal. 2008, 12, 74–83. [Google Scholar]

- Akter, M.; Khatun, S.; Biswas, H.B.; Kim, H.S. Knowledge of menstruation and the practice of hygiene among adolescent girls in Bangladesh. East African Scholars J Med Sci. 2020, 2, 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neyazi A, Faizi G, Afzali H, Ahmadi M, Razaqi N, et al. Assessment of knowledge, attitude and practice about the menstruation among secondary school girls in Herat, Afghanistan - A cross sectional study, 27 August 2021, PREPRINT (Version 1) available at Research Square. Available online: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-847912/v1.

- Chaudhury, S.; Kumari, S.; Sood, S.; Davis, S.; Chaudhury, S. Knowledge and practices related to menstruation among tribal adolescent girls. Ind. Psychiatry J. 2021, 30, 160–S165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanchan, Y.; Rizwana, S.; Charu, S.; Kalpna, G.; Jitendra, J. , et al. Menstrual pattern in medical students and their knowledge and attitude towards it. Int J Med Health Res. 2018, 4, 19–22. [Google Scholar]

- Guide to menstrual hygiene materials. United Nations Children’s Fund. First edition. 19. 20 May. Available online: www.unicef.org.

- Bali, S.; Sembiah, S.; Jain, A.; Alok, Y.; Burman, J.; Parida, D. Is There Any Relationship between Poor Menstrual Hygiene Management and Anemia? – A Quantitative Study Among Adolescent Girls of the Urban Slum of Madhya Pradesh. Indian journal of community medicine : official publication of Indian Association of Preventive & Social Medicine. 2021, 46, 550–553. [Google Scholar]

- Anand, T.; Garg, S. Menstruation related myths in India: strategies for combating it. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2015, 4, 184–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanie Kaiser. Menstrual Hygiene Management. 2008. Available online: http://www.sswm.info/content/menstrual-hygiene-management (accessed on 12 August 2022).

- UNICEF. Bangladesh: Tackling menstrual hygiene taboos. Sanitation and Hygiene Case Study No. 10. 2008. Available online: http://www.unicef.org/wash/files/10_case_study_BANGLADESH_4web.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2022).

- Mukherjee, A.; Lama, M.; Khakurel, U.; Jha, A.N.; Ajose, F.; Acharya, S.; Tymes-Wilbekin, K.; Sommer, M.; Jolly, P.E.; Lhaki, P.; et al. Perception and practices of menstruation restrictions among urban adolescent girls and women in Nepal: a cross-sectional survey. Reprod. Heal. 2020, 17, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten, VT. Menstrual hygiene: A neglected condition for the achievement of several millennium development goals. Europe External Policy Advisors. 2007. Available online: http://www.eepa.be/wcm/component/option, com_remository/func, startdown/id, 26/.

- FSG (2016). Available online: https://www.fsg.org/publications/opportunity-address-menstrual-health-and- gender-equity.

- Choi, H.; Lim, N.-K.; Jung, H.; Kim, O.; Park, H.-Y. Use of Menstrual Sanitary Products in Women of Reproductive Age: Korea Nurses’ Health Study. Osong Public Heal. Res. Perspect. 2021, 12, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiq MA, Salih AA. Knowledge and Practice of Adolescent Females about Menstruation in Baghdad. J. Gen. Pr. 2013, 2, 138. [CrossRef]

- Morley, W. Common myths about your period. 2014. Available online: http://www.womenshealth.answers.com/menstruation/common-myths-about-your-period (accessed on 12 August 2022).

- Savanthe, A.; Nanjundappa, V. Menstruation: a cross-sectional study on knowledge, belief, and practices among adolescent girls of junior colleges, Kuppam, Andhra Pradesh. Int. J. Med Sci. Public Heal. 2016, 5, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siabani, S.; Charehjow, H.; Babakhani, M. Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices (KAP) Regarding Menstruation among School Girls in West Iran: A Population Based Cross-Sectional Study. 2018, 6, 8075–8085. [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, K.K.; Alkharan, A.; Abukhamseen, D.; Altassan, M.; Alzahrani, W.; Fayed, A. Knowledge, readiness, and myths about menstruation among students at the Princess Noura University. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2018, 7, 1197–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).