1. Introduction

Neurogenesis, the process by which new neurons are formed within the brain, occurs both during embryonic development and, to a more limited extent, in the adult brain. For decades, the prevailing view held that neurons do not multiply after development. The first indication to the contrary came in 1962, when Altman reported autoradiographic evidence of neuronal proliferation in adult rats [

1].

Two decades later, Bayer et al. provided additional evidence for neuronal proliferation in the adult mammalian brain [

2]. Although recent literature remains divided, with some studies supporting [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9] and others questioning [

10,

11,

12] the extent and significance of human adult neurogenesis (for review, see [

13]), its potential contribution to human brain function and to the pathogenesis of neuropsychiatric disorders cannot be dismissed. Among brain regions where neurogenic activity has been reported, the hippocampus consistently exhibits the highest rates [

14].

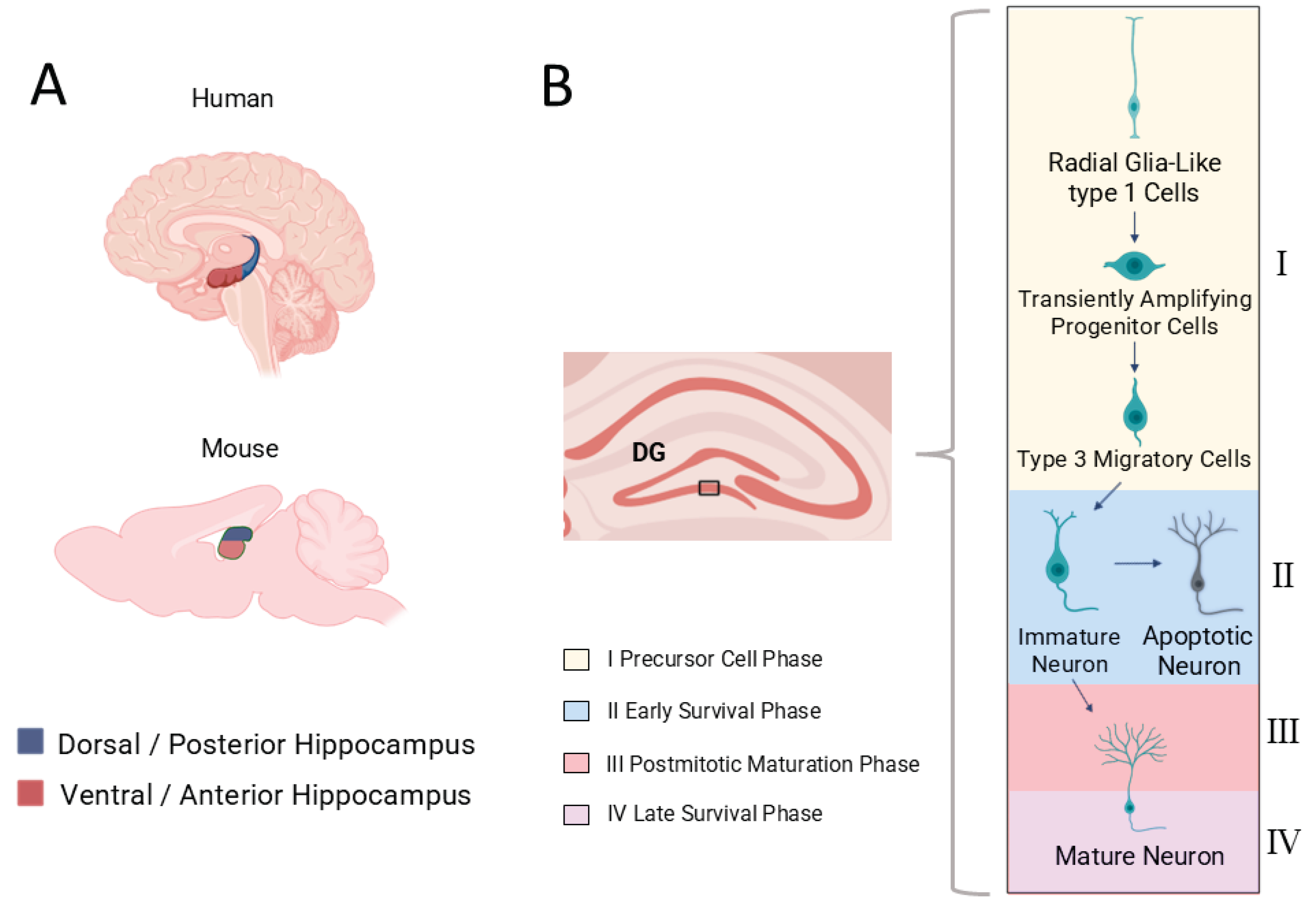

The hippocampus subserves a wide range of functions, including spatial navigation and cognition [

15,

16], learning and memory consolidation [

15,

17] and emotional processing [

18]. AHN occurs in the subgranular zone (SGZ) of the hippocampal dentate gyrus (DG), where newborn granule cells are generated and integrated into existing hippocampal circuits [

19], linking experience to structural plasticity. Importantly, the hippocampus is not functionally uniform. It displays a longitudinal (dorsoventral or septotemporal) specialization, with the dorsal portion being more involved in spatial and cognitive processing, and the ventral portion contributing to emo-tional and stress-related regulation [

20]. Growing evidence suggests that AHN also exhibits region-specific regulatory mechanisms and behavioral outcomes [

21]. These dorsoventral distinctions, discussed in detail in

Section 4, provide an anatomical framework for understanding how diverse physiological, behavioral, and pathological factors exert distinct influences on cognition and emotion.

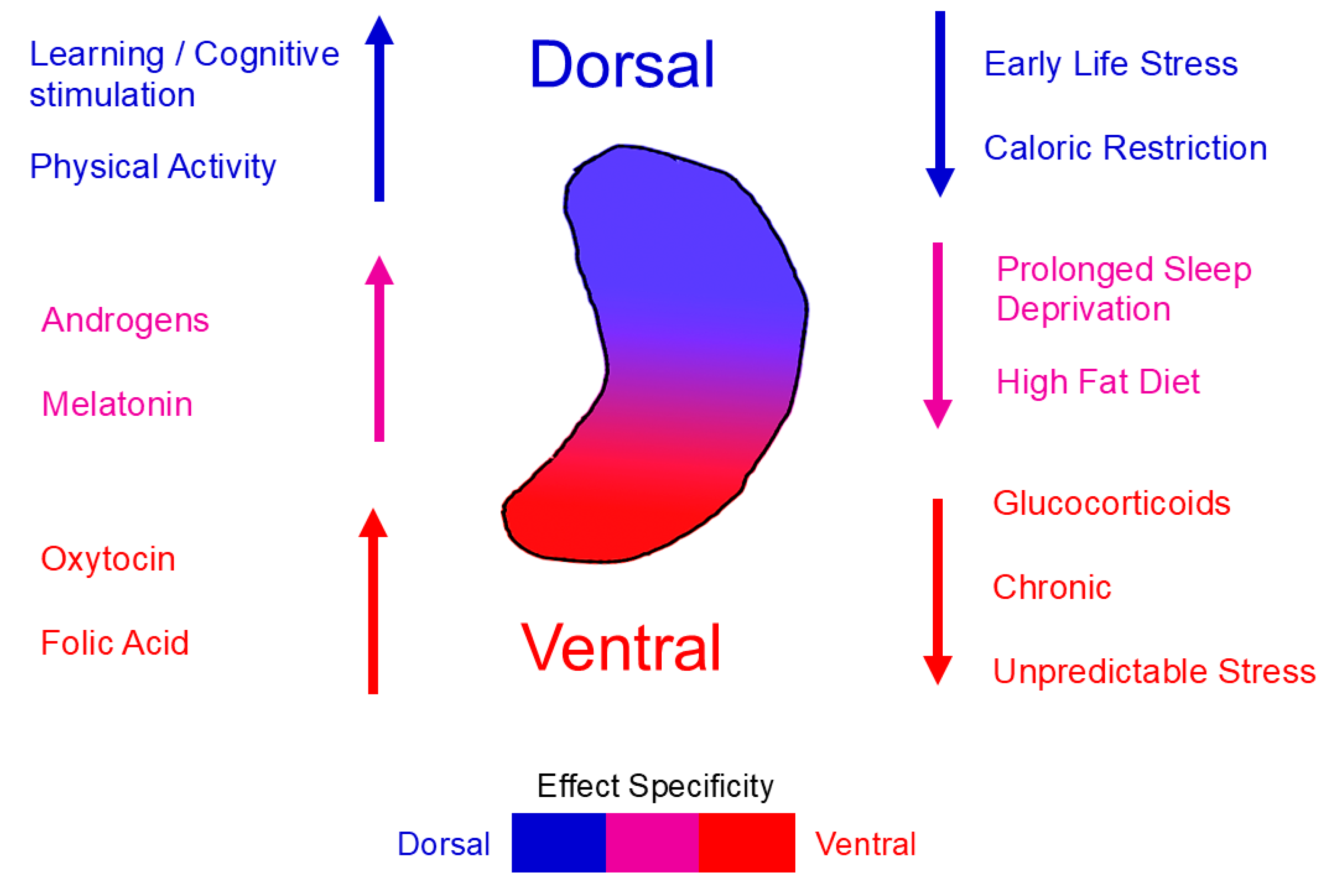

The discovery of AHN and its capacity to reshape neural plasticity has prompted intensive investigation into how intrinsic and extrinsic factors modulate its levels. Modifiable influences, such as hormonal environment, behavior and diet are of particular interest due to their potential to reveal molecular mechanisms through which lifestyle impacts brain function. Notably, several studies indicate that some of these factors appear to differentially affect AHN along the hippocampal axis, suggesting that both baseline neurogenesis and regional plasticity may determine the direction and magnitude of their effects. Recognizing these dorsoventral distinctions provides a framework for understanding how diverse physiological, behavioural, and pathological factors exert distinct influences on cognition and emotion.

While numerous reviews have summarized modulators of AHN [

22,

23,

24] , this subregional perspective is largely overlooked. The goal of this review is therefore to synthesize evidence on the most widely studied modifiers of AHN in animal models and humans, with explicit attention to subregion-specific effects along the hippocampal dorsoventral axis. We further examine how these mechanisms relate to neuropsychiatric disease, highlighting their potential translational and therapeutic implications.

2. Adult Neurogenesis in the Hippocampus: Brief Historical Overview and Basic Mechanisms

Despite the increasing interest and research being conducted on adult neurogenesis over the past decades, there is still notable controversy on whether its presence is significant enough in humans, with some claiming that it is purely an evolutionary remnant, especially in organisms with high cognitive function [

12]. However, there have been some studies which support that a considerable level of adult neurogenesis does in fact exist in humans. The first indication of neurogenic activity taking place in the adult human hippocampus came into light in 1998, when Eriksson et al, administered a birth-dating marker, Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) in 5 middle-aged patients and observed newly born neurons (BrdU +) expressing factors such as calbindin in the postmortem evaluation of their hippocampi [

25]. Following this report, many studies explored the extent of adult neurogenesis in humans. One of the most striking and controversial studies that have been conducted to this end measured the quantity of the isotope

14C in hippocampal neurons following the above-ground nuclear bomb tests between 1945 and 1963 [

26]. In the aftermath of these tests,

14C was released in the atmosphere and was absorbed by plants. Humans consumed products from these plants or meat from animals feeding on them which contained

14C and this isotope was absorbed and used by dividing cells in their adult organisms. Spalding et al, found large quantities of

14C in the hippocampal DG that were consistent with 700 new neurons being born in each hippocampus per day and an annual turnover of 1.75% of the hippocampal neurons within the renewing fraction [

26]. These groundbreaking results have faced criticism with some authors arguing that postmitotic neurons can integrate

14C through other mechanisms than cell division, such as DNA repair or methylation [

12]. However, Spalding et al, claim that the amount of

14C they detected in the adult hippocampus is too high to be explained just by these mechanisms alone and that an underlying neurogenic activity more accurately reflects these findings [

26]. Nevertheless, even if levels of AHN in humans are minimal, clarifying the underlying mechanisms could still yield insights with potential translational relevance.

AHN has been reported to be mediated by Neural Stem Cells (NSCs) that reside in niches mainly in the SGZ of the hippocampal DG, where they remain quiescent. It has been proposed that AHN can be divided into four phases: The precursor cell phase (I), the early survival phase (II), the postmitotic maturation phase (III) and the late survival phase (IV) [

27] (

Figure 1). Different cell types are present in each phase which can be identified by specific protein-markers they express. In the precursor cell phase, radial glia-like stem cells of three types can be identified. Radial glia-like type 1 cells (expressing the markers GFAP, Nestin, BLBP, Sox2) give rise to radial glia-like type 2a (expressing the markers GFAP

+/-, Nestin, BLBP, Sox2) and 2b (expressing the markers Nestin, DCX, PSA-NCAM, NeuroD, Prox1) cells. Type 2 cells, also known as Transiently Amplifying Progenitor cells (TAPs), exhibit high proliferative activity, in contrast to their successors, type 3 cells (expressing DCX, PSA-NCAM, NeuroD and Prox1), which are mainly involved in migration into the granular layer. In the early survival phase, new-born neurons (expressing Calretinin, NeuN, DCX, PSA-NCAM, NeuroD and Prox1) either survive or undergo apoptosis [

27]. The fate of these newly born neurons can be influenced by multiple factors which we will be discussing later in this review. The postmitotic maturation phase follows the early survival phase and facilitates synaptogenesis. New neurons in this phase have a lower threshold for long term potentiation than their older equivalents and exhibit increased synaptic plasticity. Finally, the late survival stage refers to the morphological maturation of the newborn neurons who have emerged from the thousands of neuroblasts originally generated and have established functional connections within the existing circuitry [

27]. Interestingly, several studies have reported differing sensitivities of the dorsal and ventral DG to various stimuli that induce or impair AHN.

3. Factors Modifying Hippocampal Neurogenesis

3.1. Hormones

Hormones are soluble chemical messengers produced and secreted by endocrine glands in multicellular organisms. They contribute to homeostasis by acting in multiple organs, such as the brain. Their action is mediated through intracellular or extracellular receptors which are expressed at certain target cells. Research over the past years has underscored the neurogenic impact of various hormones in the hippocampus, which could involve stimulatory, inhibitory or neuroprotective outcomes. Although circulating hormone levels are not directly modifiable, they can be easily influenced either by other factors such as diet and behavior or by extrinsic administration

3.1.1. Cortisol / Corticosterone

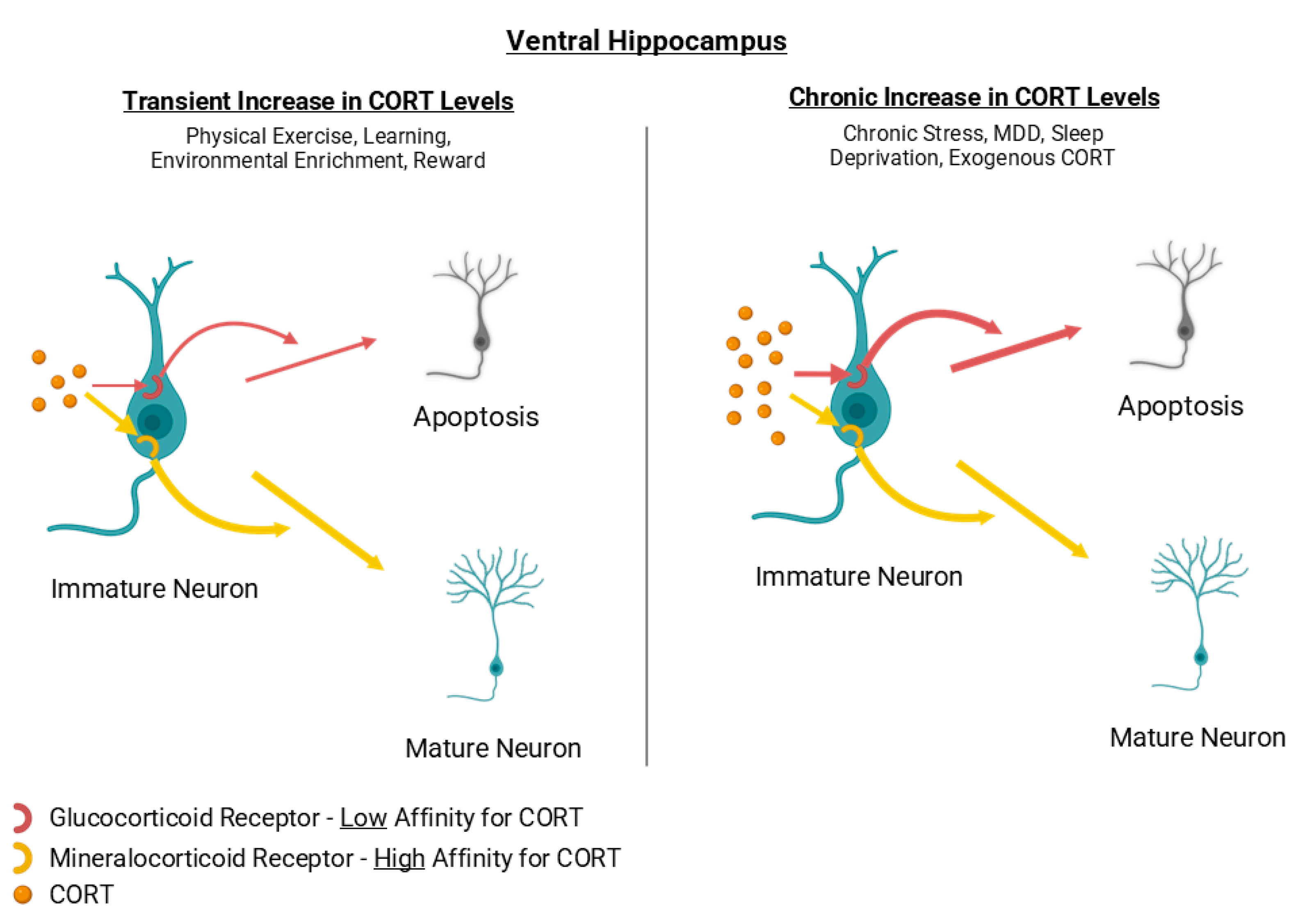

Cortisol in human and corticosterone in rodents, collectively referred to as CORT, are steroid hormones synthesized by the zona fasciculata of the adrenal glands. CORT is involved in multiple functions such as immunosuppression and the metabolism of proteins, lipids and carbohydrates. Its secretion is regulated by the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis and typically increases in response to stress. As a steroid hormone, CORT mainly exerts its action through intracellular glucocorticoid receptors (GRs) or mineralocorticoid receptors (MRs). The cortisol-receptor complex binds to specific element DNA motifs or interacts with transcription factors (e.g. NF-κB, STAT3 and AP-1) in the target cell’s nucleus to modulate gene expression.

MR and GR are abundantly expressed in hippocampal neurons, with MRs exhibiting ~10-fold higher affinity for CORT than GRs [

28,

29]. Pharmacological studies report that MR agonists and GR antagonists have been associated with a positive effect on hippocampal neurogenesis [

30,

31,

32]. Conversely, prolonged CORT exposure has been shown to reduce hippocampal neurogenesis [

33,

34,

35] and the ventral hippocampus seems to have an increased intrinsic sensitivity to CORT than its dorsal counterpart [

36]. Recently, Wang et. al (2024) have suggested that p21 (kinase inhibitor promoting cycle arrest) overexpression with subsequent accumulation of ROS might be the culprit mechanism behind the CORT-induced deficits in hippocampal neurogenesis [

33].

At the same time, many authors argue that moderate-to-high circulating CORT levels are also associated with an increase in hippocampal neurogenesis. Physical exercise, enriched environment, sexual experience as well as learning have all been correlated with both elevated neurogenic rates and higher circulating CORT levels [

23,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43] . However, it has been suggested that the rewarding nature of these activities may lead to the activation of mechanisms that overcome the negative effects of high CORT levels resulting in an overall increase in neurogenesis [

30]. Other authors suggest that there is an optimal level of circulating CORT that favors neurogenic activity, and any factor that either increases or decreases this level could lead to diminished rates of AHN [

31].

Taken together, chronically elevated CORT, due to persistent stress or exogenous administration, tends to suppress AHN, with a ventral-biased vulnerability, while moderate to high CORT levels have been reported to bolster AHN [

36]. Considering MR/GR pharmacology and receptor affinity, low-to-moderate CORT levels likely support AHN primarily through MR-dominant signalling, whereas sustained high CORT levels inhibit AHN via GR-dominant signalling [

44]. Activities that produce transient CORT elevations [

23,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43], may enhance AHN by maintaining favourable MR/GR balance, whereas conditions that produce chronic CORT elevations [

45] can impair AHN through GR saturation and downstream anti-proliferative pathways [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

44] (

Figure 2) . Further work should delineate the exact impact of CORT levels on hippocampal neuron proliferation in both the dorsal and ventral hippocampus. In summary, glucocorticoid-induced suppression of AHN is not uniform along the dorsoventral axis of the hippocampus. The ventral DG, which is more responsive to stress and emotional regulation, displays greater vulnerability to corticosterone elevation, whereas the dorsal segment shows comparatively milder and more transient effects.

3.1.2. Estrogens

Estrogens are a group of steroid hormones that are known for their major role in the development the female reproductive system. Outside of this traditional function, estrogens also have considerable effects on multiple organs and tissues, such as the bone, liver, blood vessels, skin, fat and central nervous system. The three most dominant types of estrogen are 17β-estradiol, estrone and estriol. 17β-estradiol is mainly produced by the ovaries, estriol is produced by the placenta and estrone is produced in adipose tissue via aromatization. Estrogens primarily exert their action through intracellular nuclear receptors (ERα and ERβ) but also through membrane-bound receptors G protein-coupled estrogen receptor 1 (GPER1), ER-X and Gq-mER [

46].

ERα and ERβ and GPER1 receptors are expressed widely in the brain, with ERβ mainly being found in the hippocampal DG [

47]. GPER1 deficiency has been shown to impair neurogenesis in the hippocampus, indicating that GPER1 could play a role in the induction of hippocampal neurogenesis [

48]. Multiple researchers have noted that estradiol stimulates AHN and cell proliferation of adult female rats in a time and dose-dependent manner. The dose of estradiol that has been most associated with positive effects in hippocampal neurogenesis is 10 μg. Acute administration of estradiol has been correlated with increased cell proliferation and survival in the hippocampus, while chronic administration has been associated with the opposite effects [

49,

50,

51]. Research regarding estrogen’s impact on the male hippocampus, however, has been scarce. There are indications that survival of young granule neurons in the male DG is increased after estradiol administration [

52]. Many authors also highlight the fact that even though most experiments are being conducted with estradiol, which is a potent estrogen, different types of estrogen can also have different effects on neurogenesis. Estrone administration, for example, has been associated by many with a decreased neurogenic potential, especially when it comes to cell proliferation [

49,

51]. In addition, aromatase inhibition has been reported to augment AHN levels in middle-aged female mice [

53].

Regarding the regional impact of estrogens on AHN, available evidence remains limited. In one study, the phytoestrogen daidzein enhanced neurogenesis in both the ventral and dorsal hippocampus, with more prominent effects dorsally [

54]. Overall, estrogens tend to transiently enhance AHN in female rodents, whereas prolonged or chronic exposure may reduce hippocampal cell proliferation, suggesting a complex, time-dependent regulation. The negative impact of chronic estrone administration also needs further evaluation, as this hormone is elevated in obesity due to increased aromatization of androgens in adipose tissue [

55]. Taken together, these findings indicate that estrogens exert regionally distinct influences on AHN along the hippocampal longitudinal axis. Experimental data suggest that estrogen-induced proliferation and neuronal differentiation are generally stronger in the dorsal DG, consistent with its cognitive specialization, whereas ventral neurogenesis appears less robust or more transiently modulated, potentially reflecting differences in ER distribution and stress-related signaling between the two poles of the hippocampus.

3.1.3. Androgens

Androgens are a group of steroid hormones responsible for the development of the male reproductive system. They also have anabolic actions in the musculoskeletal system. The main androgens found in mammals are testosterone and Dihydrotestosterone. Testosterone is produced and secreted by Leydig cells in the testis and can be converted to DHT by 5α-reductase in peripheral tissue. Androgens mainly exert their actions by binding to intracellular Androgen Receptors (AR) and modulating the expression of multiple genes in the target cells.

ARs are expressed in multiple regions of the brain, such as the hippocampus [

56]. Many researchers report a positive correlation trend between long-derm androgen administration and the survival of new hippocampal neurons in both the dorsal and the ventral hippocampus, with statistically significant benefit being observed only in young male rats [

56,

57,

58]. On the contrary, anabolic steroid androgens, which are commonly used among athletes, have been shown to abolish the positive neurogenic effects of exercise [

59]. Overall, androgens, with the exception of anabolic steroids, seem to be beneficial to AHN in an age and sex specific pattern, favouring only young males and only if administered chronically.

Evidence on the dorsoventral specificity of androgen effects on AHN remains limited, although some findings suggest that androgenic modulation may exhibit regional differences. Testosterone and its metabolites appear to enhance cell proliferation and neuronal survival predominantly in the dorsal DG [

57,

60], consistent with its role in cognitive and spatial processes, whereas effects in the ventral region are weaker or context-dependent [

61] This gradient may reflect variations in AR density, local aromatization to estrogens, and the distinct functional circuitry of the dorsal and ventral hippocampus. For instance, AR expression is somewhat higher in the dorsal hippocampus [

61,

62], suggesting greater responsiveness in this region. Conversely, alterations in androgen/estrogen balance, such as those induced by aromatase inhibition, can enhance ventral neurogenesis [

53]. Together, these findings indicate that androgenic modulation acts in a region-dependent and context-sensitive manner along the hippocampal longitudinal axis.

3.1.4. Oxytocin

Oxytocin is a peptide hormone mainly synthesized in the hypothalamus and secreted into the bloodstream by the posterior pituitary gland. Acting through its transmembrane G-protein-coupled receptor (OXTR), oxytocin regulates multiple physiological and behavioral functions, including parturition, uterine contraction, milk ejection, sexual behavior, and social interaction [

63,

64]

OXTR is abundantly expressed in the hippocampus of rodents but appears much less prevalent in the human hippocampus [

65,

66].

Research on the impact of oxytocin on AHN remains limited, though several studies indicate that chronic intranasal or peripheral oxytocin administration increases neurogenic activity, particularly in the ventral DG [

67,

68]. Peripheral oxytocin treatment can even counteract the inhibitory effects of stress and glucocorticoids on hippocampal cell proliferation [

64]. However, other studies reported reduced neurogenesis following oxytocin administration under acute treatment paradigms [

69], suggesting that the duration and route of administration critically determine its neurogenic outcome.

Evidence on the dorsoventral specificity of oxytocin’s effects on AHN remains limited. In adult rats, systemic or intracerebral oxytocin administration promotes social interaction and stress resilience but exerts modest or inconsistent effects on hippocampal cell proliferation overall [

69]. Nevertheless, the behavioral domains influenced by oxytocin, such as social bonding, anxiety regulation, and affective processing, are functions predominantly mediated by the ventral hippocampus [

70,

71]. Neurogenesis in the ventral DG has been linked to the modulation of stress-related and emotional behaviors [

72], suggesting that oxytocin’s neuromodulatory actions may preferentially influence this hippocampal segment. Although direct comparisons of dorsal and ventral neurogenic responses to oxytocin are scarce, current evidence supports a model in which ventral AHN is particularly sensitive to oxytocin-mediated regulation, consistent with the peptide’s broader role in emotional adaptation and social cognition.

3.1.5. Thyroid Hormones

Thyroid hormones (THs), primarily triiodothyronine (T3) and thyroxine (T4), are peptide hormones synthesized and secreted by the thyroid gland. They exert their effects through intracellular and membrane-associated thyroid hormone receptors (TRs), including TRα1, TRα2, and TRβ1, which are widely expressed in the adult brain [

73,

74]. THs play essential roles in regulating metabolism, homeostasis, and neurodevelopment.

Experimental models indicate that hypothyroid states reduce the survival and differentiation of adult DG cell progenitors in both mice and rats [

75,

76,

77]. In contrast, hyperthyroidism has been associated with enhanced neuronal differentiation and postmitotic progenitor survival in mice [

76], though such effects were not replicated in rats [

75], suggesting species-dependent variability. To date, no studies have explicitly examined the impact of THs on neurogenesis along the dorsoventral hippocampal axis. Nevertheless, indirect evidence suggests potential region-specific effects. TRα and TRβ are differentially distributed across hippocampal subregions [

78].

Moreover, TH signaling interacts with neurotrophic and glucocorticoid pathways [

79,

80], both of which show stronger regulatory impact in the ventral hippocampus. This raises the possibility that TH modulation could influence dorsal neurogenesis more directly through receptor-mediated transcriptional control, while exerting indirect or stress-linked effects ventrally via endocrine cross-talk.

In summary, hypothyroidism appears to impair, and hyperthyroidism to potentially enhance, AHN, but species differences and methodological variability complicate interpretation. Future research should clarify how TH receptor distribution and signaling intersect with dorsoventral specialization to determine regional susceptibility or plasticity within the adult hippocampus, as well as their relevance to human neurogenesis.

3.1.6. Melatonin

Melatonin is an indoleamine hormone primarily synthesized and secreted by the pineal gland, typically in response to darkness. It regulates circadian rhythm, core body temperature, energy metabolism, and immune function, and also exerts potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects. Melatonin acts mainly through its G-protein–coupled receptors MT1 and MT2, which are distributed throughout the mammalian brain, including the hippocampus. MT1 receptors are abundantly expressed across the hippocampus, whereas MT2 receptors show higher density in the CA3 region [

81].

Several studies have investigated melatonin’s role in AHN. Pinealectomy in rats markedly decreases the number of newborn hippocampal neurons, an effect reversed—and even surpassed—by chronic melatonin supplementation [

82]. Consistent findings demonstrate that melatonin primarily enhances neuronal survival and differentiation, rather than cell proliferation, thereby potentiating the effects of other pro-neurogenic stimuli such as physical exercise [

83,

84,

85,

86]. Melatonin’s neuroprotective role is further supported by studies showing attenuation of AHN deficits induced by hyperglycemia, glucocorticoid exposure, or manganese toxicity [

87,

88,

89]. Additionally, melatonin administration improves recovery after ischemic injury, promoting neuronal regeneration possibly through MT2-mediated signaling [

90,

91]. Collectively, these findings establish melatonin as a robust enhancer of hippocampal neurogenesis and neuronal resilience. Its beneficial effects appear to stem largely from antioxidant and anti-inflammatory actions that improve survival and maturation of newborn neurons.

Regarding dorsoventral specificity, evidence points to a ventral predominance of melatonin’s neurogenic and behavioral effects. In rodents, melatonin treatment ameliorates stress-induced anxiety and depression-like behaviors, functions mediated primarily by ventral hippocampal circuits [

71,

92]. Moreover, activation of MT2 receptors has been shown to promote AHN and antidepressant-like outcomes through upregulation of Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) and modulation of glucocorticoid signaling [

93,

94]. Although direct dorsal–ventral comparisons remain limited, these data suggest that melatonin preferentially enhances ventral DG plasticity, consistent with its role in emotional regulation and stress resilience. Future work should aim to clarify whether melatonin’s pro-neurogenic actions extend equivalently to dorsal hippocampal domains involved in cognitive processes.

3.1.7. Growth Hormone, IGF-1

Growth Hormone (GH) is a peptide hormone synthesized, stored and secreted by somatotropic cells in the anterior pituitary gland. It plays a major role in somatic growth, regulating bone and organ development as well as lipid and mineral metabolism. Although GH acts directly on tissues through growth hormone receptors (GHRs), many of its effects are mediated indirectly by insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1). GH stimulates the synthesis of IGF-1 in the liver and peripheral tissues, and IGF-1 in turn promotes tissue growth via its membrane-bound receptor tyrosine kinase (IGF1R).

Both GHRs and IGF1Rs are expressed in multiple brain regions, including the hippocampus [

95,

96]. Peripheral administration of GH or IGF-1 increases cell proliferation in the hippocampal formation [

97,

98], and several studies suggest that exercise-induced neurogenesis is partly mediated by upregulation of circulating GH and IGF-1 [

99,

100]. These trophic hormones enhance neurogenesis by promoting angiogenesis, synaptic plasticity, and neuronal survival through BDNF- and Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF)-dependent pathways [

101,

102,

103]

To date, no studies have directly examined the impact of GH or IGF-1 on neurogenesis across the dorsoventral axis of the hippocampus. However, indirect evidence suggests region-specific modulation. Exercise and growth factor signaling preferentially engage ventral hippocampal circuits associated with stress resilience and emotional regulation [

71,

92], implying that GH/IGF-1–mediated neurogenesis may be more dynamically regulated in this region. Conversely, the dorsal hippocampus, enriched in GH receptor expression, could support GH-driven enhancement of spatial and cognitive processes [

104,

105]

Collectively, GH and IGF-1 appear to positively modulate hippocampal cell proliferation and survival, but their region-specific influence along the hippocampal longitudinal axis remains to be determined. Future studies should address whether these hormones differentially regulate ventral (emotional) and dorsal (cognitive) neurogenesis, particularly in the context of exercise and aging.

3.1.8. Erythropoietin

Erythropoietin (EPO) is a peptide hormone that is mainly synthesized in the kidneys in response to hypoxia and stimulates erythropoiesis (proliferation and differentiation of erythrocyte precursors). It exerts its actions via its membrane receptors (EPO-R) which are expressed at target cells.

EPO-R expression is observed in various brain cell types, including hippocampal neural progenitor cells [

106]. There are reports indicating that EPO enhances neurogenesis and inhibits apoptosis of new-born cells in the hippocampal DG [

107,

108]. Other researchers have observed increased rates of neurogenesis correlated with increased levels of EPO due to cognitive challenge-induced hypoxia in hippocampal neurons [

109]. Furthermore, the impact of EPO in neurogenesis could suggest another mechanism through which the positive neurogenic effects of exercise are mediated [

110]. Nevertheless, to our knowledge, there have not been reports yet exploring EPO’s effect on neurogenesis in the ventral compared to the dorsal hippocampus.

Overall, there has been some evidence that supports a positive neurogenic effect of EPO in the hippocampus, but further research could explore its exact action along the hippocampal longitudinal axis.

3.2. Behavior

3.2.1. Physical Activity

Physical activity has long been associated with improved brain health and cognitive performance. Light aerobic exercise enhances multitasking and executive function in young adults [

111], while chronic intermittent voluntary running in mice produces long-lasting benefits on learning and memory [

112]. These findings have prompted extensive investigation into the molecular mechanisms underlying the neurogenic and cognitive effects of exercise.

Human imaging studies reveal that regular aerobic activity in late adulthood increases anterior hippocampal gray matter volume, a region enriched in adult neurogenesis, suggesting that the beneficial cognitive effects of exercise may be mediated by increased neuronal production [

113,

114]. In both rodents and humans, physical activity elevates circulating growth factors such as IGF-1, BDNF, and VEGF [

115,

116], which together promote synaptic plasticity, angiogenesis, and neurogenesis in the hippocampal formation [

38,

100]. More recently, irisin, a myokine secreted by skeletal muscle during exercise, has been shown to exert anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects, contributing to activity-induced hippocampal neurogenesis [

117,

118]. The adipokine adiponectin may similarly support the pro-neurogenic and cognitive benefits of physical exercise [

119]. Furthermore, ablation of newborn neurons following running abolishes the typical exercise-induced improvements in cognition and memory [

120], demonstrating that AHN plays a causal role in mediating exercise-driven brain plasticity. It should be noted, however, that excessive or prolonged voluntary running can sometimes reduce neurogenesis, possibly due to increased physiological stress and glucocorticoid release [

121].

Regarding the distribution of exercise-induced neurogenesis along the hippocampal dorsoventral axis, most studies report stronger effects in the dorsal DG, consistent with its role in spatial learning and cognitive processing [

38,

83,

122]. For example, it has been demonstrated that environmental enrichment combined with voluntary exercise preferentially enhanced dorsal neurogenesis, which correlated with improved spatial performance, whereas ventral neurogenesis contributed more to stress resilience and affective behavior [

123]. Other studies, however, observed increases in both dorsal and ventral subregions, suggesting that exercise engages distinct neurogenic pools depending on intensity, duration, and hormonal context. Overall, physical activity enhances AHN through systemic and local trophic factors, with dorsal neurogenesis predominantly supporting cognitive gains and ventral neurogenesis mediating emotional regulation and stress adaptation. Clarifying the parameters that shift this balance may help optimize exercise-based interventions for cognitive and affective disorders.

3.2.2. Sleep

Sleep is divided into Rapid Eye Movement (REM) and non-Rapid Eye Movement Non-REM (NREM) sleep. REM sleep comprising 25% of total sleep time, is characterized by random rapid movement of the eyes with beta waves being recognized on electroencephalogram (EEG) recordings. NREM is further divided into Stage 1 (N1), Stage 2 (N2) and Stage 3 (N3). N1 is the lightest sleep stage and comprises 5% of total sleep time with theta waves being observed on EEG. N2 sleep is deeper than N1, comprises 45% of total sleep time and sleep spindles along with K complexes can be seen on EEG. Finally, N3 is the deepest non-REM sleep, comprises 25% of total sleep time and the EEG at this stage consists of delta waves which have the lowest frequency and the highest amplitude [

124].

Adequate sleep is essential for optimal brain function, influencing cognition, memory, and mood regulation [

125,

126,

127]. Since these processes are closely linked to AHN, numerous studies have examined how sleep and neurogenesis interact. Sleep deprivation, fragmentation, or restriction consistently reduce neurogenic potential, impairing newborn neuron proliferation, survival, and differentiation (for review see [

24]). Prolonged or repeated sleep loss has been shown to decrease neurogenesis and cell proliferation in both the dorsal and ventral DG [

128]. Furthermore, the decrease in DCX-labeled cells was more pronounced in the ventral hippocampus than in the dorsal region [

128]

However, as sleep deprivation also constitutes a potent stressor, elevated glucocorticoid levels may mediate part of the observed neurogenic suppression [

129]. Distinguishing direct effects of disrupted sleep from stress-related mechanisms therefore remains an important experimental challenge.

Beyond general suppression, sleep and its disruption appear to influence AHN differentially along the dorsoventral hippocampal axis. While studies in rodents have shown that sleep deprivation preferentially impairs neurogenesis in the ventral DG, corresponding with increases in anxiety-like behaviors [

130], it has also been reported that REM sleep deprivation can also reduce cell proliferation in the dorsal DG and impair hippocampal-dependent spatial memory [

131].

These findings suggest that sleep disturbances may predominantly affect ventral neurogenesis [

128,

129], consistent with the ventral hippocampus’s sensitivity to stress and emotional regulation. This is further supported by findings presented by O’Leary and Cryan [

71], as well as by Tanti and Belzung [

132], who provide comprehensive reviews demonstrating that stress affects multiple stages of AHN preferentially in the ventral rather than the dorsal hippocampus. Additionaly, Perera et al. [

133] showed in non-human primates that chronic stress reduced immature neurons in the anterior (ventral equivalent) but not posterior hippocampus, and this effects was correlated with stress-induced anhedonia.

Future studies should employ experimental designs that disentangle the direct neurogenic effects of sleep architecture from those mediated by stress hormones. Such differentiation is crucial, as therapeutic strategies targeting glucocorticoid signaling may protect ventral neurogenesis, while interventions enhancing sleep quality and REM integrity could preferentially restore dorsal and ventral neurogenic balance.

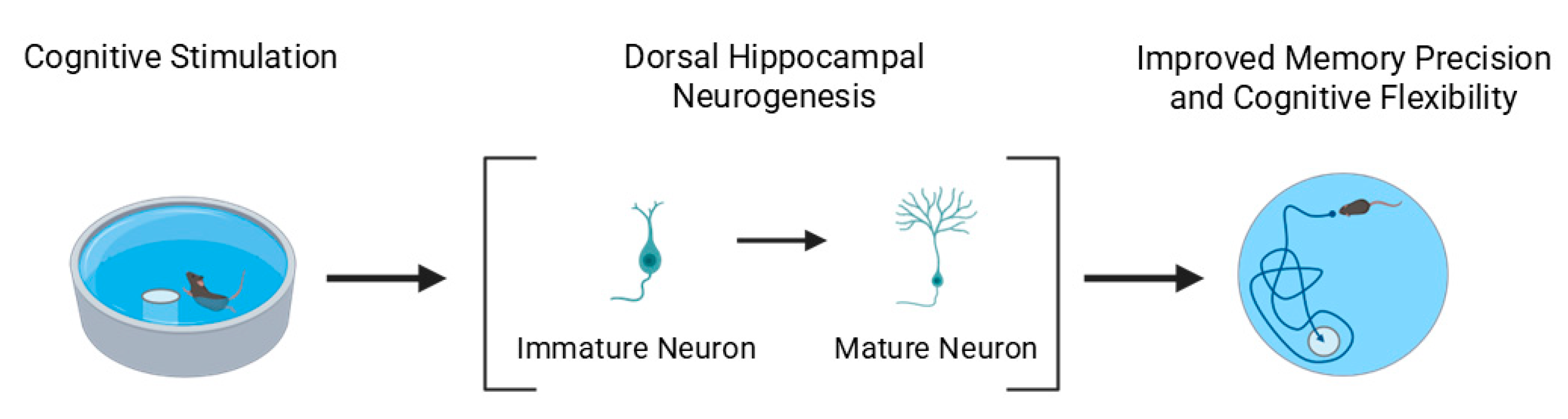

3.2.3. Learning

The process of learning has long been associated with the hippocampal formation, and since high neurogenic activity occurs in this region, AHN has been proposed as a mechanism supporting learning and memory.

The relationship between learning and neurogenesis appears to be bidirectional. Inhibition of neurogenic potential in animal models disrupts contextual learning and memory performance [

134,

135], while specific learning tasks enhance AHN by increasing the survival of newborn granule cells [

136]. Training paradigms such as trace conditioning, stimulus contiguity conditioning, long-delay conditioning, and the Morris water maze are associated with elevated neurogenic rates [

137]. Moreover, the complexity of the task and the degree of hippocampal engagement correlate positively with the survival and integration of new neurons [

137,

138,

139].

The increased survival of newborn hippocampal neurons has been linked to improved memory precision and cognitive flexibility. For example, in the Morris water maze, mice with enhanced neurogenesis exhibit more spatially precise navigation and greater adaptability when the hidden platform is relocated, reflecting improved memory updating and reduced perseveration [

140].

Although most data derive from rodent studies, evidence suggests similar adaptive processes in humans. Neuroimaging and neuropsychological assessments of London taxi drivers, who undergo extensive spatial training, revealed increased posterior hippocampal gray matter volume compared with controls and bus drivers [

141,

142]. This structural enlargement corresponded to superior performance in spatial navigation and landmark proximity judgments but reduced recall of complex non-spatial visual patterns, indicating a potential functional specialization and trade-off in hippocampal processing. These findings support the concept that persistent cognitive demands can induce hippocampal remodeling—possibly involving AHN—favoring memory improvements in domain-relevant circuits.

Regarding the dorsoventral axis, converging evidence indicates that learning-related increases in neurogenesis are more pronounced in the dorsal hippocampus, which is primarily involved in spatial and contextual learning [

123,

143] (

Figure 3). In contrast, ventral hippocampal neurogenesis appears to contribute more to emotionally charged or reward-based learning [

144]. For instance, learning paradigms with strong emotional valence or stress components, such as fear conditioning or reward anticipation, recruit ventral DG circuits where neurogenesis facilitates adaptive behavioral responses [

145]. Thus, dorsal neurogenesis supports cognitive precision and spatial mapping, whereas ventral neurogenesis underlies motivational and affective learning, reflecting complementary but distinct roles along the hippocampal longitudinal axis.

3.2.4. Rewarding Experience

The reward system comprises a network of interconnected brain regions responsible for evaluating, predicting, and anticipating rewarding stimuli, as well as motivating behavior and generating the sensation of pleasure. The orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) compute the expected value of potential rewards and the effort required to obtain them. This information is integrated by the ventromedial (vmPFC) and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) to guide decision-making on reward pursuit [

146]. When rewards are obtained, dopaminergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) signal deviations between expected and actual outcomes (reward prediction errors) [

147,

148]. If outcomes are as good as or better than predicted, these neurons increase firing toward limbic and cortical targets, including the prefrontal cortex, cingulate gyrus, nucleus accumbens (NAc), hippocampus, and amygdala. Dopaminergic input to the amygdala and cingulate gyrus generates the emotional experience of pleasure, while projections to the hippocampus facilitate long-term memory consolidation of rewarding events, enabling their future recall [

148].

Although research directly investigating the effects of rewarding experiences on AHN is still limited, available data suggest that repeated engagement in rewarding behaviors can enhance neurogenic activity. For example, sexual experience, which robustly activates the reward system [

149], increases neuronal proliferation in the hippocampal DG of both young and middle-aged rats [

150]. These effects partially restore age-related declines in neurogenesis and improve performance in cognitive tasks [

151].

Beyond behavioral experiences, dopamine, the principal neurotransmitter in reward processing, exerts direct neurogenic effects. Dopaminergic stimulation enhances the proliferation of neural precursor cells and the survival of newborn neurons in the DG [

152,

153], likely via D1/D2 receptor–mediated modulation of BDNF and CREB signaling cascades. This suggests that reward-related dopaminergic activity may couple motivational states to hippocampal structural plasticity.

Although no studies have systematically examined dorsoventral differences in reward-related AHN, converging evidence supports a ventral predominance. The ventral hippocampus is functionally connected to the NAc and amygdala, and neurogenesis in the ventral DG has been shown to modulate reward sensitivity, stress resilience, and affective regulation [

144,

145]In contrast, dorsal hippocampal neurogenesis contributes more to cognitive flexibility and spatial memory, which can also influence reward learning indirectly [

123]. These findings collectively suggest that rewarding experiences, as well as their dopaminergic reinforcement, may primarily recruit ventral hippocampal neurogenic circuits, aligning with the emotional and motivational functions of this subregion. Future research should explore how distinct rewarding stimuli (e.g., social interaction, novelty seeking, or food-related rewards) differentially influence dorsal and ventral neurogenesis and whether these effects contribute to adaptive versus maladaptive motivational behaviors.

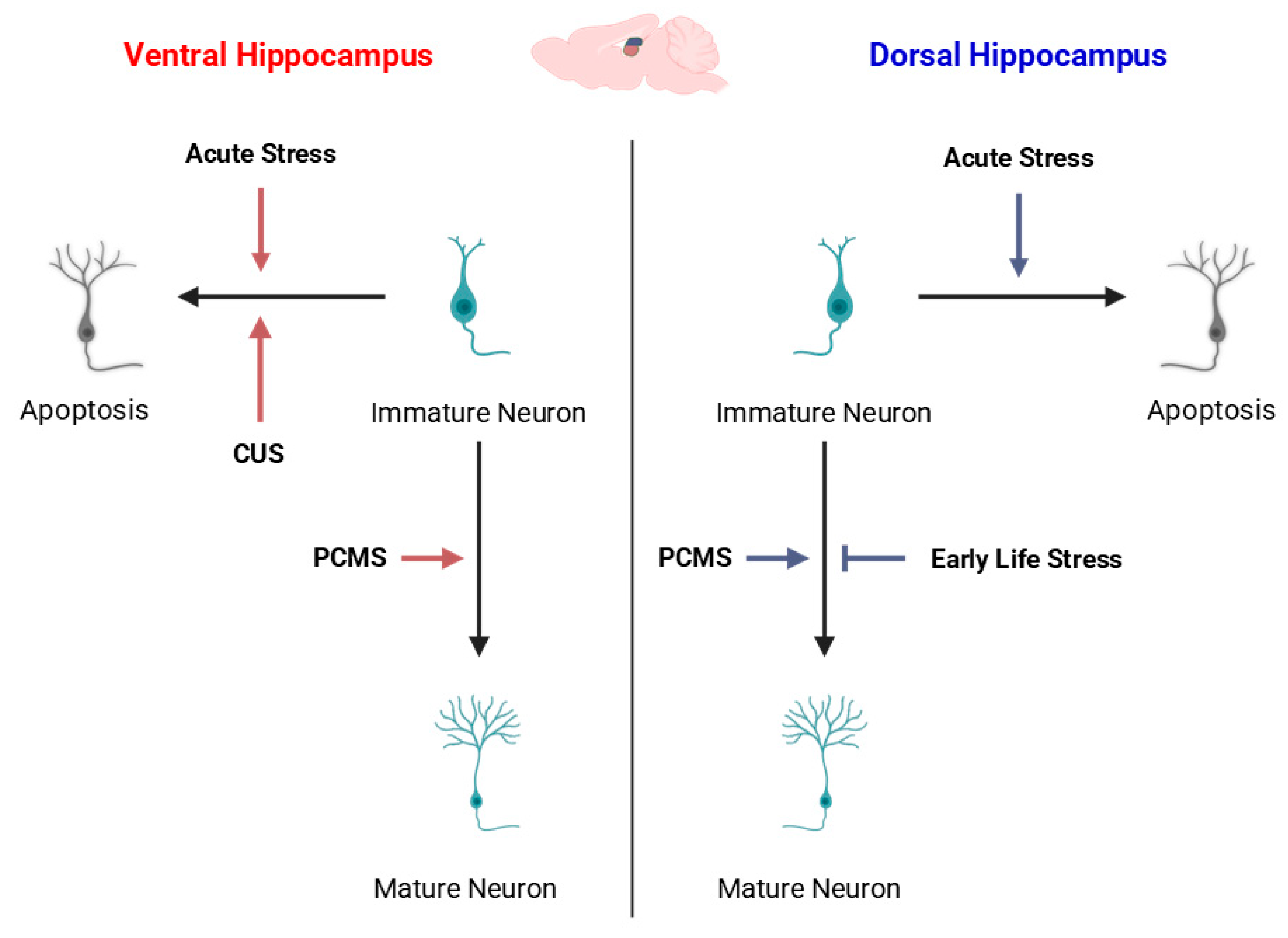

3.2.5. Stress

Stress is defined as a physiological response to demanding environmental or psychosocial conditions which can cause uncertainty about future situations or events. Normally, its induction better prepares the organism to overcome these challenges and to reachieve homeostasis. A balanced stress response is essential for the optimal functionality of these organisms but conditions which cause extreme acute or chronic stress can lead to various negative effects.

Stress exerts profound effects on brain structure and function, and the hippocampus is one of the primary neural targets of stress-induced remodeling. The impact of stress on AHN depends on its duration, intensity, and controllability. Acute stress may transiently suppress progenitor proliferation, whereas chronic or unpredictable stress paradigms consistently produce long-lasting reductions in AHN [

154,

155]. The underlying mechanisms involve sustained activation of the HPA axis, resulting in elevated glucocorticoid levels that impair neuronal proliferation, differentiation, and survival [

156,

157]. In addition, stress-induced inflammatory cytokines, oxidative stress, and decreased trophic signaling—particularly BDNF downregulation—further contribute to reduced neurogenesis [

72,

158]

Experimental models such as chronic restraint stress, chronic unpredictable mild stress (CUMS), and social defeat have consistently shown diminished cell proliferation and neuronal differentiation within the DG [

150,

159] (

Figure 4). These reductions in AHN are accompanied by behavioral correlates of depression and anxiety, suggesting that decreased neurogenesis contributes to stress-related psychopathology [

152]. Pharmacological or behavioral interventions that reduce HPA axis hyperactivity or increase trophic signaling (e.g., antidepressants, environmental enrichment, voluntary exercise) can partially restore AHN and alleviate these behavioral deficits [

155]

The effects of stress are not uniform along the hippocampal dorsoventral axis

. A growing body of evidence demonstrates that ventral hippocampal neurogenesis is particularly sensitive to stress exposure, whereas dorsal neurogenesis is relatively more resilient. Chronic stress paradigms preferentially suppress cell proliferation and reduce immature neuron numbers in the ventral DG [

72,

157]. Conversely, the dorsal hippocampus, which is primarily involved in spatial and cognitive functions, exhibits smaller or transient changes in proliferative activity following similar stress conditions [

71]. This regional asymmetry is in line with functional specialization since the ventral hippocampus regulates emotional and stress-related responses, while the dorsal hippocampus supports cognitive processing and memory.

Moreover, recovery of ventral neurogenesis following chronic stress correlates closely with antidepressant efficacy and behavioral normalization, emphasizing its role as a key mediator of emotional resilience [

92,

145]. In contrast, dorsal neurogenesis appears to contribute more to the restoration of cognitive flexibility after stress cessation. Overall, stress primarily targets the ventral AHN, reflecting its integration into limbic–endocrine circuits. Future studies should aim to delineate the molecular determinants of this regional vulnerability and to clarify how interventions that selectively restore ventral AHN might enhance emotional resilience without perturbing cognitive function.

3.3. Diet and Nutritional Modifiers of AHN

The relationship between nutrition and brain health has been thoroughly studied and it is now widely accepted that a balanced diet throughout an organism’s lifetime is of great importance in order to achieve optimal brain function. The World Health Organization (WHO) considers a healthy diet to be a principal preventative factor for the development of cognitive decline and dementia [

160]. To better understand the impact of nutrition on mental health, researchers have studied the molecular mechanisms involved. Evidence suggests that synaptic plasticity and hippocampal neurogenesis are significantly affected by both the amount and the type of food consumed [

22]. Many of these dietary and hormonal factors exert region-specific influences along the hippocampal axis, a distinction further examined in the following section.

3.3.1. Caloric Restriction & High Fat Diet

The restriction of caloric intake without the induction of malnutrition, known as caloric restriction (CR), has been associated with multiple health benefits and extended longevity [

161]. In the hippocampus, CR influences the adult neurogenic process, though results remain inconsistent across studies. Some authors report that CR increases the number of newborn cells in the DG [

162,

163], possibly through the enhanced release of BDNF [

164]. Others, however, suggest that CR may decrease the neurogenic potential of neural progenitor cells [

165,

166,

167]. Age appears to be an important moderating factor: younger animals may be more susceptible to CR-induced reductions in neurogenesis, whereas older individuals often show maintained or improved neurogenic capacity under CR conditions [

165].

Staples et al. [

167] provided important insights into the phase- and region-specific effects of CR along the hippocampal dorsoventral axis. Their findings indicate that CR enhances the proliferation of neural progenitors while simultaneously reducing the survival of newborn neurons, and that these effects are confined to the ventral DG. In contrast, the same study found a reduction in total granule cell number restricted to the dorsal DG, whereas the ventral subregion remained unaffected. This apparent bidirectional impact underlines the need to assess AHN not only by cell counts but also by the functional integration of newborn neurons into hippocampal circuits. Region-specific vulnerability suggests that dietary interventions may exert paradoxical effects on cognition versus mood regulation, thereby enhancing emotional adaptability via ventral neurogenesis while potentially impairing dorsal, cognition-related plasticity.

Diets rich in saturated fats represent the opposite metabolic condition and are established risk factors for obesity, coronary artery disease, and several cancers [

160]. Mounting evidence indicates that high-fat diets (HFDs) also impair brain health, leading to cognitive deficits and accelerated neurodegenerative processes such as dementia and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [

168,

169,

170,

171]. The neurobiological mechanisms underlying these effects involve significant disruption of hippocampal neurogenesis, with the ventral hippocampus showing greater susceptibility to diet-induced damage than other subregions [

172,

173,

174]. This inhibition of AHN is believed to arise from neuroinflammatory processes, mediated by activation of M1-type microglia, which release pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1 (IL-1), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) [

173,

174,

175]. Microglia express Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), which normally recognizes bacterial lipopolysaccharides (LPS), but can also be activated by oxidized low-density lipoproteins (LDL) generated during lipid metabolism [

176,

177,

178]. Activation of this pathway promotes microglial polarization toward the M1 pro-inflammatory phenotype, producing an inflammatory environment that is unfavorable to neurogenesis, leading to decreased proliferation and differentiation of newborn neurons [

179].

Collectively, these findings reveal that caloric restriction and high-fat diet exert opposing effects on hippocampal neurogenesis, and that these effects are regionally distinct along the dorsoventral axis. While CR may differentially modulate proliferation and survival between dorsal and ventral hippocampus, HFDs predominantly compromise ventral neurogenic integrity through inflammatory mechanisms. Understanding how energy balance interacts with hippocampal subregional specialization will be critical for designing dietary interventions aimed at optimizing both cognitive and emotional brain health.

3.3.2. Vitamins and Other Nutritional Factors

Vitamins and micronutrients are essential for neurodevelopment, neuronal maintenance, and neurotransmission, and their deficiencies are major contributors to central and peripheral nervous system disorders. Several vitamins play particularly important roles in AHN by regulating cell proliferation, differentiation, and survival.

B-complex vitamins, including vitamin B12 and folic acid, are critical for DNA synthesis and methylation, and therefore indispensable for NSC proliferation. Folic acid deficiency has been associated with reduced neurogenic rates—especially in the ventral hippocampus, where emotional and stress-regulatory circuits are more sensitive to metabolic disturbances [

180]. Vitamin B1 (thiamine) deficiency, which causes Wernicke encephalopathy, dramatically decreases the survival of newborn hippocampal neurons [

181]. This reduction likely contributes to the cognitive and memory deficits seen in Wernicke’s pathology, due to the strong interconnectivity between the mammillary bodies and hippocampus involved in episodic memory formation and confabulation [

181,

182].

Vitamin A (retinol), through its active metabolite retinoic acid (RA), functions as both an antioxidant and a regulator of gene expression. Vitamin A deficiency reduces hippocampal neurogenesis, likely through impaired cell proliferation, whereas RA supplementation restores it [

183]. Conversely, chronic RA administration, as used in some dermatological treatments, has been reported to suppress AHN [

184], underscoring the need for precise dose regulation.

Vitamin C (ascorbic acid), a potent antioxidant and enzymatic cofactor, enhances hippocampal neurogenesis and counteracts D-galactose–induced brain aging by promoting newborn neuron maturation [

185]. Postnatal vitamin C deficiency reduces total hippocampal neuron counts in guinea pigs [

186]. Overall, vitamin C appears to support neurogenesis not only in the hippocampus but also in other neurogenic niches (for review, see [

187]).

Among trace elements, zinc is particularly important for neurogenic integrity. Zinc supplementation promotes survival of neuronal progenitor cells, likely through the inhibition of apoptosis [

188]. Similarly, selenium supports AHN by increasing neural progenitor survival and reducing neuroinflammation. Its role is mediated via PI3K/Akt/Nrf2 and BDNF/TrkB signaling pathways [

189]. Although regional differences have not yet been systematically explored, selenium’s neuroprotective role may extend preferentially to the ventral hippocampus, where oxidative and inflammatory stress are more prominent.

Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, including eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), are essential for maintaining neuronal membrane fluidity and synaptic function. DHA supplementation increases hippocampal neurogenesis by enhancing newborn neuron survival [

190], while long-term dietary EPA/DHA intake reverses age-related declines in neurogenesis [

191]. These effects may be more pronounced in the ventral hippocampus, consistent with the antidepressant and anxiolytic effects of omega-3 fatty acids and the ventral region’s role in emotional regulation.

Flavonoids, a broad class of plant-derived polyphenols, have received considerable attention for their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and neuroprotective effects. They modulate oxidative stress and neuroinflammation and may act directly on neuronal progenitors to promote proliferation and differentiation (for review, see [

192]). Curcumin, the yellow polyphenolic pigment found in Curcuma longa (turmeric), shares similar properties. It enhances AHN by rescuing newborn neurons from apoptosis and activating the Wnt/β-catenin pathway while increasing BDNF expression [

193,

194].

Collectively, these findings highlight the essential role of vitamins, trace elements, and bioactive dietary compounds in maintaining AHN. While evidence for dorsoventral specificity remains limited, deficiencies in vitamins such as folate or nutrients affecting oxidative and inflammatory homeostasis appear to impair ventral neurogenesis preferentially, potentially leading to emotional dysregulation. In contrast, nutrients that enhance synaptic and trophic signaling (e.g., omega-3 fatty acids, vitamin A, curcumin) may also strengthen dorsal neurogenesis linked to cognitive resilience. Future work should address how specific micronutrient pathways interact with hippocampal subregional specialization to support both cognitive and emotional health.

Table 1.

A summary of the most important nutritional factors affecting AHN along with examples of foods that contain them in high concentrations.

Table 1.

A summary of the most important nutritional factors affecting AHN along with examples of foods that contain them in high concentrations.

| Nutritional Factor |

Effect on AHN |

Examples of Foods with High Concentrations |

References |

| High-Fat |

Decrease |

Processed meat, Butter, Full-Fat dairy products |

[172]

[195] |

| Folic Acid |

Increase |

Leafy green vegetables, legumes, whole grains, egg yolk, liver, citrus fruit |

[180]

[196] |

| Vitamin B1 |

Increase |

Brown rice, whole grains, pork, poultry, soybeans, nuts, peas, dried beans |

[181]

[197] |

| Vitamin E |

Increase |

Wheat germ oil, sunflower seeds, almonds, hazelnuts, peanuts, broccoli, spinach |

[198]

[199]

|

| Vitamin A |

Increase |

Pumpkin, carrot, squash, sweet potato, mango, papaya, poultry, fish, red grapefruit, collards |

[183]

[200] |

| Vitamin C |

Increase |

Citrus fruits, berries, tomatoes, potatoes, green leafy vegetables |

[187]

[201] |

| Zinc |

Increase |

Beef, legumes, poultry, cereals, pork |

[188]

[202] |

| Omega-3 Fatty Acids |

Increase |

Fish, poultry, dairy |

[191]

[203] |

| Flavonoids |

Increase |

Red wine, tea, peppers, blueberries, strawberries, apples, spinach, onions |

[192]

[204] |

| Curcumin |

Increase |

Turmeric, yellow curry |

[193] |

| Selenium |

Increase |

Seafood, meats, eggs and dairy products |

[189] |

4. AHN in a Dorsoventral Perspective

The hippocampus exhibits a remarkable functional and structural differentiation along its dorsoventral axis, which extends from the dorsal (septal) to the ventral (temporal) pole. This organization is accompanied by distinct, yet interrelated, behavioural and cognitive functions subserved by each region: the dorsal hippocampus is primarily engaged in spatial and cognitive processing, whereas the ventral hippocampus is preferentially involved in emotion, stress regulation, and affective behaviour [

205,

206], which are accompanied by specializations at the molecular and cellular levels [

20,

206,

207,

208]. Correspondingly, AHN also displays regional heterogeneity in baseline activity, regulation, and functional relevance [

145,

209,

210].

4.1. Dorsoventral Heterogeneity of Neurogenesis

Early studies suggested that cell proliferation and immature neuron density (marked by doublecortin expression) were higher in the dorsal DG of rodents, implying a predominance of neurogenesis related to cognitive functions [

54,

143]. However, subsequent research revealed that mature adult-born neurons are more numerous in the ventral DG, indicating that overall neuronal addition may actually favor the ventral region. This contradiction could be the result of increased newborn neuron survival in the ventral hippocampus and be dependent on species, age, and environmental conditions.

In marmosets, for example, a relatively homogeneous distribution of doublecortin (DCX)-positive neurons was observed along the septotemporal axis [

210], whereas in rodents, dorsal enrichment in proliferation coexists with stronger neurogenic modulation in the ventral domain under specific physiological or stress conditions [

123,

211]. Furthermore, this apparent paradox suggests that regional differences in survival rates and maturation kinetics are critical determinants of final neurogenic output.

In general, baseline levels of progenitor proliferation and immature neuron density are higher in the dorsal DG, and cognitive stimulation through environmental enrichment and learning paradigms tends to preferentially enhance dorsal neurogenesis [

123,

143] supporting its tonic role in information encoding, spatial learning, and pattern separation in the dorsal hippocampus [

54,

143]. In contrast, the ventral DG typically exhibits lower baseline neurogenesis, but it shows increased sensitivity to environmental, hormonal, and emotional stimuli. Chronic stress paradigms, such as social defeat and unpredictable chronic stress, preferentially suppress ventral neurogenesis, while antidepressant treatments predominantly restore neurogenesis in this same region. Neurogenesis in the ventral hippocampus is preferentially affected by stress, antidepressants, and neuromodulators [

71,

72,

92](O’Leary et al., 2014; Alvarez-Contino et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2023). For instance, chronic stress or elevated Tau expression selectively suppresses ventral neurogenesis and promotes anxiety-like behaviour [

72], whereas antidepressant treatments such as fluoxetine or GALR2/Y1R agonists restore neurogenesis primarily in the ventral DG and alleviate depressive phenotypes [

92,

212]. Thus, while the dorsal hippocampus maintains stable, tonic neurogenesis supporting cognitive operations, the ventral hippocampus is dynamically regulated by stress hormones, immune signals, and antidepressant treatments, reflecting its emotional and adaptive plasticity. This regional specialization aligns with the established functional dichotomy with the dorsal hippocampus involved mainly in spatial/cognitive processing and the ventral hippocampus more involved in emotional/stress regulation.

4.2. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Dorsoventral Differences

The molecular mechanisms underlying dorsoventral differences in neurogenesis are increasingly understood. For instance, the miR-17-92 cluster, is more highly expressed in the ventral DG, promoting neurogenesis and exerting antidepressant-like effects [

213]. Similarly, region-specific signalling via neuregulin-1 and β₂-adrenergic or GABAergic pathways selectively promote ventral neurogenesis and emotional resilience [

92,

214,

215,

216]. Conversely, dorsal neurogenesis is preferentially modulated by learning and cognitive stimulation, with higher increases in the dorsal hippocampus following environmental enrichment, physical activity, and training tasks [

123,

143]. Transcription factors such as AP2γ or JNK1 influence proliferation and neuronal differentiation with predominant effects in the dorsal hippocampus, consistent with its cognitive specialization [

216,

217], reinforcing a distinction between cognitive-tonic and emotional-plastic neurogenic segmentation of the hippocampus. On the other hand, the miR-17-92 cluster shows higher expression in the ventral hippocampus and promotes neurogenesis with antidepressant-like effects [

213,

218]. In addition, JNK1 inhibition produces preferential enhancement of neurogenesis in the ventral hippocampus [

216]. Also, the secreted frizzled-related protein 3 (sfrp3) exhibits a dorsoventral gradient that could potentially contribute to differential adult NSC activity between dorsal and ventral regions [

219,

220].

Norepinephrine and potassium chloride treatment significantly preferentially enhance neurosphere formation in temporal (ventral-equivalent) hippocampal progenitors regions compared with septal (dorsal-equivalent) ones, indicating higher intrinsic excitability and responsiveness of ventral neural stem cells [

221,

222].

4.3. Functional Implications

Selective regulation of neurogenesis along this axis produces behaviourally dissociable outcomes, thereby supporting a dual neurogenic system. Neurogenesis in the dorsal hippocampus contributes to pattern separation, spatial learning, and memory precision, whereas ventral-born neurons integrate into circuits regulating affective and stress responses [

144,

145]. Suppression of ventral neurogenesis increases anxiety and stress susceptibility [

72], while enhancement of ventral hippocampus neurogenesis confers stress resilience and antidepressant-like effects [

145,

212]. Importantly, neurogenic responses to environmental or pharmacological modulation, including exercise, enriched environments, or antidepressant drugs, show regionally distinct outcomes. Manipulations that potentiate dorsal neurogenesis correlates with cognitive flexibility and spatial memory performance [

123,

143]. Environmental enrichment or voluntary exercise can upregulate neurogenesis in both hippocampal segments but contributes differentially to behavioural improvement: dorsal neurogenesis supports cognitive recovery, whereas ventral neurogenesis appears to mediate emotional normalization [

123]. Interestingly, adult-born neurons in both dorsal and ventral hippocampus contribute to contextual fear conditioning, but likely through distinct mechanisms. Dorsal adult-born neurons may contribute to the acquisition and recall of context representations, while ventral adult-born neurons may modulate the ability of these representations to activate fear via hippocampal projections to the amygdala [

223,

224,

225,

226]. These findings indicate that behavioural outcomes depend on the spatial locus of neurogenesis activation.

4.4. Integrative Perspective

Taken together, these findings support a bidirectional model in which dorsal and ventral neurogenesis function as complementary systems for adaptive behaviour. The dorsal hippocampus functions as a stable, cognition-oriented generator with higher tonic neurogenic output, and the ventral hippocampus, characterized by lower baseline activity but greater modulatory plasticity, may function as a flexible regulator of affective behaviour, supporting emotional adaptation to environmental and physiological challenges. As illustrated in

Figure 5, modulatory influences exhibit distinct dorsoventral profiles, highlighting their predominant regional effects and directionality on AHN. This spatial specialization may have evolved to allow parallel yet integrated regulation of cognition and emotion via distinct neurogenic domains. Variability in dorsoventral neurogenesis patterns across species [

210,

227] and experimental models add further complexity to this framework, and suggest that region-specific susceptibility to stress, hormones, or disease factors could underlie differential neuropsychiatric vulnerabilities across species, thereby pointing to important clinical implications. For instance, understanding that ventral neurogenesis preferentially responds to antidepressant treatments while dorsal neurogenesis supports cognitive enhancement could inform precision medicine approaches for psychiatric and neurological conditions. The clinical implications of AHN will be further discussed in

Section 5.

Table 2.

Summary of factors affecting AHN that have been studied along the hippocampal longitudinal axis.

Table 2.

Summary of factors affecting AHN that have been studied along the hippocampal longitudinal axis.

| Factor |

Effect on Ventral AHN |

Effect on Dorsal AHN |

References |

| Learning |

No change / Decrease |

Increase |

[143,228] |

| Chronic Unpredictable Stress |

Decrease |

No change |

[156] |

| Early Life Stress |

No change |

Decrease |

[158] |

| Physical Activity |

No change / Increase |

Increase |

[38,83,122] |

| Prolonged Sleep Deprivation |

Decrease |

Decrease |

[128] |

| Caloric Restriction |

Increase / Decrease |

Decrease |

[167] |

| High-Fat Diet |

Decrease |

Decrease |

[173] |

| Folic Acid |

Increase |

No change / Increase |

[180] |

| Cortisol |

Decrease* |

No change / Decrease* |

[36] |

| Estrogens |

Increase / No change /

Decrease ** |

Increase / Decrease ** |

[49,54] |

| Androgens |

Increase |

Increase |

[58] |

| Oxytocin |

Increase |

No change |

[68] |

| Melatonin |

Increase |

Increase |

[83] |

5. Neuropsychiatric Implications

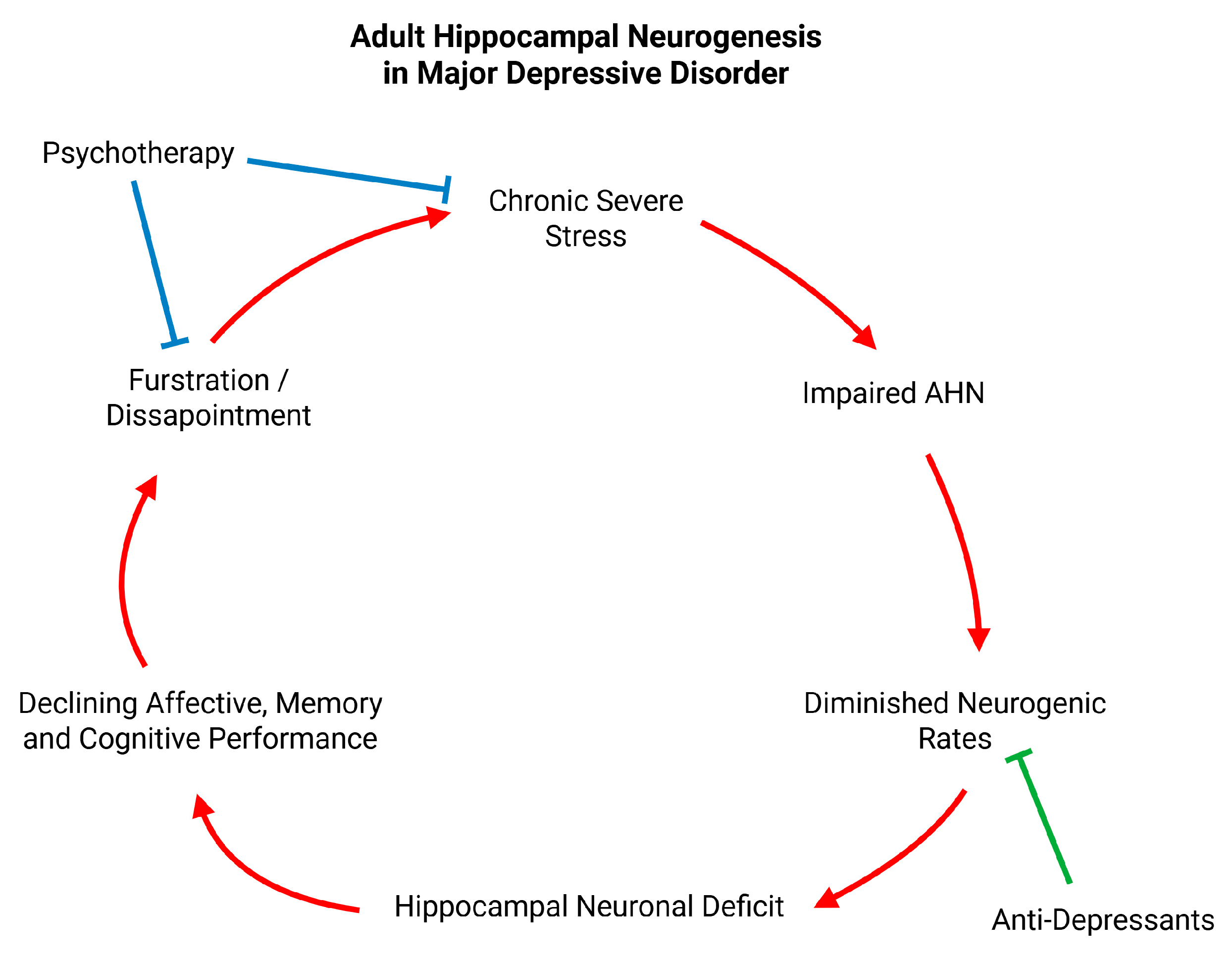

Many of the factors that influence the rates of adult Neurogenesis AHN have also been associated with multiple neuropsychiatric disorders, characterized by cognitive, emotional, and motivational dysregulation, such as Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), Schizophrenia and AD. This observation led to the assumption that adult Neurogenesis AHN may play a role in the pathogenesis and prognosis of these diseases with recent evidence further supporting this theory [

229]. The dorsoventral differentiation of AHN provides a valuable anatomical and functional framework to interpret these alterations. Disorders with predominant cognitive impairments may involve dysfunction of dorsal neurogenesis, whereas those characterized by emotional dysregulation, anxiety, or motivational disturbances are more likely associated with ventral deficits. Reduced ventral neurogenesis is a recurring feature across mood and stress-related disorders, whereas symptoms associated with dorsal deficits are often prodromal in conditions marked by cognitive impairment such as AD.

5.1. Major Depressive Disorder & Anxiety Disorders

MDD is a psychiatric disorder classically characterized by persistent depressed mood and loss of interest in activities that were previously enjoyed by the diseased individual (anhedonia). When symptoms are severe, patients might experience suicidal ideation and / or resort to self-harm [

230]. Anxiety disorders are either chronic or episodic/situational states characterized primarily by excessive fear, worry, or nervousness that is disproportionate to the situation and interferes with daily functioning. Evidence shows reduced AHN in models of MDD and anxiety, particularly within the ventral hippocampus, which integrates stress, serotonergic, and neuroendocrine inputs [

72,

145].

Multiple studies have been conducted to explore structural differences in patients with MDD with evidence indicating that the hippocampi of the diseased are usually characterized by reduced gray matter volume. This finding is positively correlated with the duration of the illness [

231,

232]. However, evidence is not sufficient to support causality.

In addition, acute and severe forms of MDD are associated with an elevated cortisol response [

45] which is detrimental to newborn neuron proliferation. These findings indicate that reduced rates of AHN could explain a part of MDD pathogenesis [

233]. This hypothesis is further supported by the fact that the same factors which have been found to be beneficial for the mood of MDD patients, such as healthy diet and lifestyle, are also shown to have positive effects in neurogenic activity. Moreover, anti-depressants used for the treatment of MDD, such as Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs), Tricyclic Antidepressants (TCAs) and Monoamine oxidase Inhibitors (MAOIs) have been shown to significantly increase the rates of AHN through an increase in the number and maturation neural progenitor cells [

212,

234,

235,

236,

237]. These neurogenic enhancements seem to in fact be essential for the positive effect of anti-depressants, since mice with abolished neurogenic potential fail to show behavioral improvement following chronic anti-depressant administration [

238,

239]. Chronic stress, glucocorticoid excess, and pro-inflammatory states suppress ventral proliferation and neuronal differentiation, effects that can be reversed by antidepressant treatment or by stimulation of neurotrophic signaling [

71,

92,

212]. Antidepressants such as SSRIs, Agomelatine or GALR2/Y1R agonists preferentially restore neurogenesis in the ventral domain, paralleling the normalization of emotional behavior [

212,

240,

241]. The neurobiological mechanism through which the neurogenic benefits of anti-depressants are mediated is potentially related to the activation of the Wnt pathway in neural progenitor cells, induced by the increase of Serotonin levels and the subsequent activation of 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) receptors and increased BDNF release. [

242,

243]. The activation of the Wnt pathway through this mechanism has particularly been observed in the newborn neurons located in the Ventral Hippocampus [

243]. Another proposed mechanism through which antidepressants and serotonin enhance AHN levels is through the increase of hippocampal BDNF levels [

244,

245].

However, whether enhanced neurogenesis is a cause or consequence of antidepressant efficacy remains unresolved. Longitudinal imaging or biomarker studies could clarify if AHN recovery precedes mood improvement, thereby testing the neurogenesis hypothesis of depression more directly.

Furthermore, it should be noted that Nonpharmacologic treatments of MDD, such as Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT) and vagus nerve stimulation, have also been associated with significantly enhanced AHN [

246].

From a more psychological and clinical perspective, a potential mechanism through which these neuronal deficits seen in the hippocampus of untreated MDD patients can lead to the expression of MDD symptomatology is the dysfunction of the existing and constantly diminishing circuitry to provide emotional variability to the patient. This mechanism could partly account for the persistent depressive mood and anhedonia observed in patients with MDD (

Figure 6). The birth of new neurons could enhance the function of the ventral hippocampus and offer the patient an increase of emotional diversity apart from the persistent depressed mood MDD is characterized by. Additionally, researchers have shown that the neuronal deficits in the dorsal hippocampus of MDD patients can also lead to a diminished memory performance [

247]. This subpar performance can interfere with the patient’s daily life and can lead to their frustration and disappointment which can further negatively impact their mood. This cycle of events can confine MDD patients in a depressive state and psychiatric intervention at this stage should be deemed necessary (

Figure 6).

It should be noted, however, that although decreased neurogenic rates can not solely lead to depressive behaviors [

248], we propose that decreased neurogenic rates can diminish the ability of an individual to psychologically overcome daily psychosocial stressors and can therefore predispose to the development and unfavorable prognosis of MDD. In addition to depression, reduced AHN has also been observed in chronic anxiety models, consistent with the ventral hippocampus’ role in affective regulation [

155]. While the evidence base is smaller, these findings suggest that impaired neurogenesis may contribute more broadly to stress-related psychopathology.

5.2. Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is a chronic neuropsychiatric disorder, in which the patient experiences positive symptoms, such as hallucinations, delusions, disorganized speech and behaviour, as well as negative symptoms, such as impaired cognitive performance, social isolation, reduced motivation and flat affect. These symptoms cause patients to face significant disability, impairing their ability to function in daily life and can reduce their life expectancy by approximately 13-15 years [

249].

The brains of patients suffering from Schizophrenia have been well studied by researchers with results indicating that the hippocampi are among the key regions affected. More specifically, a meta-analysis comparing patients suffering from chronic schizophrenia and healthy controls showed that the average hippocampal volume was significantly smaller in schizophrenia patients [

250]. In addition, altered AHN has also been described in schizophrenia, though evidence is more heterogeneous. Neurodevelopmental models and patient studies suggest reduced proliferation and impaired integration of new granule cells in the DG [

246,

251]. There have been reports of decreased expression of cell proliferation markers and impaired maturation of newborn neurons in the adult hippocampus of schizophrenia patients, indicating that the structural differences mentioned above could be attributed to low neurogenic potential [

246]. Weissleder et. al. have explored the pathological origin of these observations and suggested that an increase in immune cell and macrophage population could explain this neurogenic impairment [

252]. It should be noted, however, that since Schizophrenia has strong heritability and usually presents at a young age, the genetic component of the disease cannot be dismissed. Many genes have been associated with an increased risk for schizophrenia development with DISC1, Dgcr8, FEZ1, NPAS3, SNAP-25 and a-CaMKII being of great interest. Notably, all of these genes not only predispose to schizophrenia but are also significantly important in the neurogenic process, playing roles in NSC proliferation and newborn neuron maturation [

246]. Moreover, a recent study showed that a mutation in the Neuregulin 1 Nuclear Signaling Pathway can cause a dysregulation of schizophrenia susceptibility genes and lead to significantly reduced synaptic plasticity NSC proliferation, even further supporting the existence of an association between Schizophrenia and Neurogenesis [

253].

Cognitive and negative symptoms, including working-memory deficits and contextual disorganization, are likely associated with dorsal hippocampal dysfunction, given the dorsal domain’s role in cognitive mapping and mnemonic precision. Conversely, positive and affective symptoms, such as stress-sensitive hallucinations or emotional dysregulation, may reflect ventral hippocampal hyperactivity and aberrant coupling with limbic regions [

254]. In rodent models, ventral hippocampal hyperexcitability drives dopaminergic dysregulation in the VTA and NAc, a hallmark of psychosis [

255]. If adult-born ventral neurons normally function to modulate or buffer this excitatory output, impaired ventral AHN could exacerbate the limbic overdrive underlying positive symptoms. Conversely, deficient dorsal AHN could impair contextual binding and contribute to cognitive disorganization.

In summary, while Schizophrenia symptoms cannot solely be attributed to low neurogenic rates, the disease’s underlying pathophysiology could lead to impaired AHN which could explain some of the structural differences and the symptoms that the patients present with, especially the ones related to cognitive and affective functions. The genes that have been implicated to predispose individuals to schizophrenia could play such an important role in the birth and maturation of neurons, that both the developing and developed brain are affected. A possibility that can also not be excluded, however, is that these adult hippocampal neurogenic deficits observed in schizophrenia patients, could also be resultant from the emotional flattening and stress that these individuals experience. In addition, schizophrenia may involve a bidirectional imbalance along the dorsoventral axis of the hippocampus: ventral hippocampus overactivity with reduced inhibitory neurogenic modulation, and dorsal hippocampus under-recruitment impairing cognitive integration. Further research needs to be conducted to determine the exact role of the known predisposing genes in the neurogenic process and the precise role of dorsal and ventral hippocampus neurogenesis in the development of schizophrenia symptoms.

5.3. Alzheimer’s Disease

AD is a neurodegenerative disorder and the most common form of dementia, a condition characterized by cognitive decline which significantly impairs an individual’s ability to meet their basic needs independently. AD patients experience a progressive deterioration in memory performance, attention, reasoning ability, speech production and comprehension [

256].

A characteristic finding in brains of AD patients is significant brain atrophy and neuronal death in many brain areas, including the hippocampal formation. This degeneration is thought to be caused by the impaired clearance and accumulation of senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in the affected brain tissue [

257,