1. Introduction

1.1. Background

One-third of the world’s food production is wasted (FAO, 2013), significantly impacting climate change, food insecurity, and resource waste (Jobson et al., 2024). Consequently, the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 12.3 sets an international target to halve food waste by 2030 (United Nations, 2015). Achieving this goal requires implementing effective prevention measures to enable consumers to reduce their food waste (Casonato et al., 2023).

Nonomura (2020) and Porpino (2016) identified behaviors influencing household food waste generation, including unplanned shopping, improper storage methods during preservation and management, forgetting food items in the refrigerator, inadequate management of leftovers, and over-preparation or leftovers during consumption. Among countermeasures for these behaviors, refrigerator management actions to use up stored food in the refrigerator differ from shopping behaviors or storage and cooking techniques. Failure in refrigerator management directly leads to discarding food. Proper management, however, holds significant potential to reduce the unused ingredients and leftover food that constitute a large portion of food waste (Waitt & Phillips, 2016; Hebrok & Boks, 2017; Yamakawa, 2020).

Initiatives to encourage household food waste reduction behaviors often rely on information provision (Hebrok & Boks, 2017; Stöckli et al., 2018; Yamakawa, 2020). However, informational interventions are generally considered to have limited effectiveness (Stöckli et al., 2018; Simões et al., 2022; Casonato et al., 2023). Non-informational interventions include those utilizing nudges or environmental modifications through physical devices (Farr-Wharton et al., 2014b; van der Werf et al., 2021; Cooper et al., 2023; van Herpen et al., 2023; European Commission Joint Research Centre, 2023; Boulet & Lauren, 2024), and food management apps based on information and communication technology (ICT) (Ganglbauer et al., 2013; Farr-Wharton et al., 2014a; Vogels et al., 2018; Mathisen & Johansen, 2022; European Commission Joint Research Centre, 2023). Smartphones are readily accessible to many consumers; therefore, interventions utilizing smartphone apps and similar tools hold significant potential for reducing household food waste (Castro et al., 2023). Furthermore, ICT tools and apps are expected to be powerful tools for policy implementation, as they have the potential to reach consumers across various socioeconomic strata (Vogels et al., 2018).

In our previous research, the use of smartphone photography and food management apps as ICT tools had a marginally significant effect on reducing food waste. The previous study identified three target behaviors within refrigerator management actions to help use up stored food, including “search for food that should be eaten quickly”, “move it to a visible place”, and “use the foods that should be eaten quickly”. The results suggested that these actions improved refrigerator organization and effectively reduced food waste (Seta et al., 2025). On the other hand, using a food management app for refrigerator inventory management presented challenges related to the burden of data entry. Additionally, the motivation to use the app and to reduce food waste relied solely on information provision. Consequently, reducing the burden when utilizing ICT tools and developing interventions to motivate users beyond information provision are key challenges. This study examined two non-informational intervention strategies to address these challenges: (1) self-monitoring to directly promote target behaviors and (2) interventions utilizing gamification to increase motivation.

1.2. Literature Review

1.2.1. Interventions Involving Self-Monitoring

Interventions that track behaviors can be considered a form of self-monitoring. Self-monitoring involves tracking one’s performance by recording actions and their outcomes, thereby gaining information about both past and present behaviors (Orji & Moffatt, 2018; Nkwo et al., 2021). Self-monitoring has applications in health and education and has gained recognition as an effective tool for behavioral change (Michie et al., 2009; Page et al., 2020; Guo, 2022; Morrow et al., 2022; Cooper et al., 2023). When faced with an objective, self-monitoring leads to self-awareness of the gap between the goal and the current state, thereby activating motivation to bridge that gap. In experiments within the food waste field, the food waste diary (hereafter referred to as the diary) serves as an equivalent to self-monitoring. In a journal format, the diary is intended primarily to measure food waste volume by recording discarded food items and the reasons for disposal (Ganglbauer et al., 2012, 2015; Hartikainen et al., 2025). Moreover, reporting food waste is also expected to increase awareness of waste volume, thereby potentially reducing it (Visschers et al., 2016).

Pelt et al. (2020) introduced an awareness-based intervention using a one-week diary to make participants aware of their own waste, and the diary intervention was compared with a classical information-based method. In this study, researchers provided information and instruction to all the participants through door-to-door interventions. Quantitative analysis of food waste through composition analysis showed no effect of the diaries on reducing food waste in the awareness-based group. However, descriptions in the participants’ diaries indicated an impact on their awareness. The one-week diary period may have been too short to instigate behavioral change. This situation leaves unresolved the potential of self-monitoring through recording personal behavior to foster awareness and behavioral change. Furthermore, although a diary may be intended to be used solely for measurement purposes in intervention studies, it may still contribute to reducing food waste (Leverenz et al., 2019). Studies examining the impact of self-reporting using direct measurements also found that the more frequently measurements were taken, the greater the reduction in food waste (Ramos et al., 2024).

Wada & Shinagawa (2018) conducted a study with university students using a self-evaluation sheet for behaviors to reduce food waste. The participants recorded whether they implemented a total of eight reduction behaviors during the purchasing, cooking, and consumption stages over a one-week period. Questionnaires assessing perceptions and awareness regarding food waste were administered before and after the intervention to analyze changes in awareness. The results showed a significant difference in “cooking only what can be eaten”, with changes also observed in awareness related to using up ingredients, eating everything prepared, and keeping track of refrigerator contents. While their study observed the influence of the evaluation sheet on awareness related to behavior, it did not evaluate actual behavioral change. Furthermore, generated food waste was not measured.

While such intervention studies involving self-monitoring are rare, some suggest a degree of effectiveness. However, they cause a burden to the subject that is not insignificant, such as estimating or measuring food waste quantities in diaries and noting disposal reasons. Therefore, applying this approach directly in the present intervention study was considered difficult. To reduce this burden, an approach like that of Wada and Shinagawa (2018) was considered, involving simple recording of reduction behaviors for self-monitoring. To our knowledge, no studies to date have set up a control group, measured food waste quantities, and verified the effectiveness of interventions using self-monitoring aimed at reducing household food waste.

1.2.2. Gamification-Based Interventions

In recent years, there has been an increase in the use of gamification to positively motivate behavior (Riar et al., 2022; Santos et al., 2025). Gamification refers to the application of game design elements to non-game contexts to increase motivation and engagement (Deterding et al., 2011; Huotari & Hamari, 2017). Common game elements (strategy types) used to increase motivation include points, badges, and leaderboards (Soma et al., 2020; Hamari et al., 2014). Points visualize a user’s engagement and experience within the game and are considered a form of reward (Zichermann & Cunningham, 2011; Mathisen & Johansen, 2022). Badges are visual indicators of progress, serving as motivators, psychological rewards, and goal-setting tools (Zichermann & Cunningham, 2011; Kyewski & Krämer, 2018). Leaderboards display players’ score rankings and are used for individual goal-setting, but they also increase motivation through competitive awareness by comparing players within the game (Zichermann & Cunningham, 2011; Landers et al., 2017). Approximately half of the current research on gamification has been in educational settings, followed by health and physical exercise. In studies that established a control group and performed quantitative analysis, over 60% showed positive results (Koivisto & Hamari, 2019).

A notable study applying gamification to reduce food waste at home was undertaken by Soma et al. (2020). They implemented an intervention using an online game that reinforced information. In the game, the participants earned points by correctly answering food waste quizzes and received monetary rewards based on their points. Two other types of informational intervention groups and a control group were also established. Compared with the other groups, the game group produced approximately 30% less food waste, and the change in food waste volume after the intervention was significantly different (p = 0.07) for the game group compared with the control group. The game group comprised 26 participating households, and food waste volume was measured via composition analysis (Soma et al., 2020). Other studies on consumer app development and usability evaluation suggest that gamification has an impact on awareness and knowledge, but the effectiveness of such interventions in reducing food waste has not been verified (Haas et al., 2022; Venessa & Aripradono, 2023).

In this context, gamification-based interventions appear to have motivational effects on behavior. While Soma et al. introduced such interventions for reducing household food waste, the points were linked to economic incentives, making it unclear whether the effect was due to gamification itself or the monetary reward. In other words, we are unaware of any studies that have specifically evaluated whether gamification can reduce household food waste solely through motivational effects arising from its psychological impact.

1.3. Purpose of This Study

As suggested in

Section 1.2, in this study, the challenges of ICT-based intervention tools identified by Seta et al. (2025) are addressed by utilizing gamification in self-monitoring to track target behaviors. Therefore, this study aims to quantitatively analyze the effectiveness of interventions involving self-monitoring and gamification, using food waste weight measurement data from the intervention and control groups, clarifying its impact on related behaviors.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Intervention Design

2.1.1. Target Behaviors

Following the approach adopted by Seta et al. (2025), three specific actions were selected as participant target behaviors within refrigerator management practices aimed at using up food inventory at home: “search” for food that should be eaten quickly, “move” food that should be eaten quickly to a visible place, and “use” food that should be eaten quickly. These actions simplify refrigerator management into a straightforward sequence of searching, moving, and using food items. They are easy to implement, have potential for widespread adoption, and form a combination of actions that can be perceived as effective, with suggested efficacy in reducing food waste (Yamakawa, 2020; Seta et al., 2025). While one target action, “use”, pertains to the cooking context, in this study “finish meals” was added from the consumption context to the above three actions, resulting in four target behaviors.

2.1.2. Theoretical Framework for Intervention Strategies

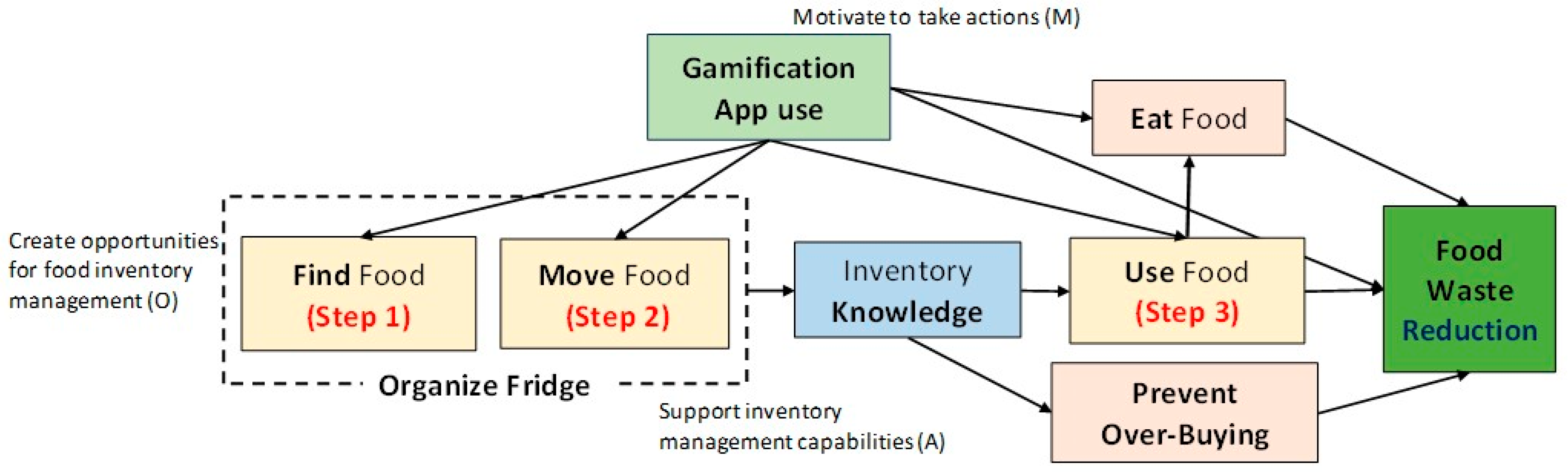

Following Seta et al. (2025), the MOA framework (Ölander & ThØgersen, 1995) was adopted as the theoretical basis for designing intervention strategies. The MOA framework posits that motivation, opportunity, and ability are necessary for action. It is frequently used as a theoretical framework for designing interventions aimed at reducing household food waste and has demonstrated effectiveness (von Kameke & Fischer, 2018; Soma et al., 2021; Cooper et al., 2023; van Herpen et al., 2023; Seta et al., 2025). In our previous intervention using the support tools, the focus was on ability (A) within the MOA framework, specifically improving knowledge and skills for refrigerator management, whereas opportunity (O) was created through the use of support tools. Motivation (M) was addressed solely through an informational intervention (Seta et al., 2025). This study also used an informational intervention to influence motivation. Additionally, it employed a non-informational intervention, tracking one's own behaviors in a food waste reduction self-monitoring app (hereafter, the self-monitoring app), to create opportunities for the target behaviors. Furthermore, it aimed to further enhance motivation for the target behaviors through game elements integrated into the app. Regarding ability, participants were generally considered to possess the necessary skills for the target behavior. Therefore, it was hypothesized that changes in motivation and opportunity would prompt the behavior. Furthermore, it was expected that the target behaviors would promote refrigerator organization and improve inventory knowledge, and that this ripple effect would enhance the ability to manage food, leading to further reductions in food waste.

2.1.3. Intervention Method 1: Information Provision

The informational intervention for participants in the intervention group was provided through an online briefing session and leaflet distribution as described by Seta et al. (2025). The content covered the importance of refrigerator management in reducing food waste, easy-to-practice target behaviors to achieve food waste reduction (“search”, “move”, and “use”), and instructions for using the self-monitoring app to encourage target behaviors.

2.1.4. Intervention Method 2: Food Waste Reduction Self-Monitoring App

As a non-informational intervention, participants were asked to use the gamified self-monitoring app designed to support and motivate the practice of four target behaviors: “search”, “move”, “use”, and “finish meals”. The researchers determined the necessary functions and specifications for the app, while the development and image creation were outsourced to a company with experience in similar app development. The app was created in Japanese.

The developed app enables daily self-monitoring by allowing users to evaluate and record their level of implementation for five items by answering the following five questions.

1. Did you check for foods to be eaten quickly? (corresponding to “search”)

2. Did you move the foods to be eaten quickly to a visible place? (“move”)

3. Did you prioritize using the foods to be eaten quickly? (“use”)

4. Did you finish eating your meal? (“finish meals”)

5. Did any food waste occur during this day?

Questions 1–4 correspond to the four target behaviors to help reduce food waste and were rated on a three-point scale as “Not great”, “So-so”, or “Perfect”. Question 5 assessed food waste quantity, rated as “Quite a bit”, “A little”, or “None”. For questions 1–3, considering the possibility of eating out, a “Not applicable” button was also provided.

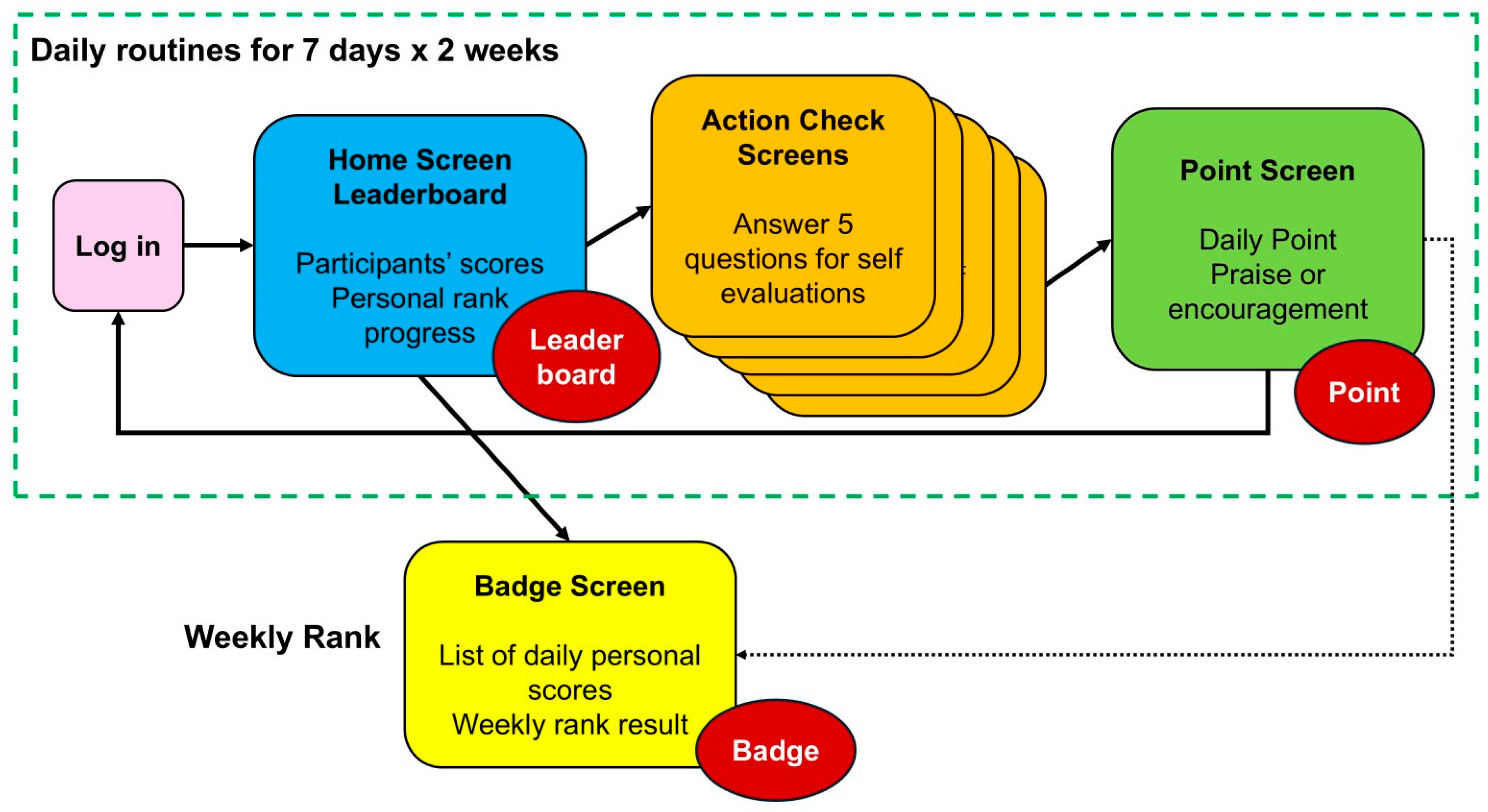

Figure 1 illustrates game elements used in the self-monitoring app.

The key game elements of points, badges, and leaderboards (PBL) were incorporated into the app structure. Points (P) were derived from self-assessment during behavior checks. For all five items, high ratings were given 20 points, medium ratings were given 10 points, and low ratings were given 5 points. “Not applicable” was assigned the same 10 points as a medium rating. Daily points were a total of these scores up to a maximum of 100 points. Daily points were displayed immediately after recording, accompanied by a message. This aimed to provide motivation by displaying messages of praise for high performance and messages of encouragement to try harder for lower performance.

Badges (B) were earned based on weekly cumulative scores, with four tiers: Bronze (0–349 points), Silver (350–489), Gold (490–629), and Platinum (630–700). Badges were awarded weekly and reset at the start of each new week, encouraging participants to maintain motivation for the following week.

The leaderboard (L) displayed a list of individual cumulative scores for the week up to that point, ordered from highest to lowest. It was placed on the home screen, which was the first screen displayed each time the user logged into the app.

2.2. Hypotheses

The hypotheses underlying this study are outlined below. The anticipated impact process of the intervention is shown in

Figure 2. Since this study focuses on the intervention’s effect on reducing food waste, hypothesis formulation centered on the relationships between the intervention and behavioral change, the intervention and food waste reduction, and behavioral change and changes in the amount of food waste.

Hypothesis 1 (H1): An intervention using the self-monitoring app leads to more frequently searching for food that should be used sooner.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): An intervention using the self-monitoring app leads to more frequently moving food that should be used sooner.

Hypothesis 3 (H3): An intervention using the self-monitoring app leads to an increase in knowledge of the refrigerator inventory.

Hypothesis 4 (H4): An intervention using the self-monitoring app leads to the more frequent use of food that should be used sooner.

Hypothesis 5 (H5): If food that should be used sooner is used more frequently, then food waste will be reduced.

Hypothesis 6 (H6): An intervention using the self-monitoring app leads to a reduction in over-buying.

Hypothesis 7 (H7): Reductions in over-buying will reduce food waste.

Hypothesis 8 (H8): An intervention using the self-monitoring app leads to more meals being finished.

Hypothesis 9 (H9): If more meals are finished, food waste will be reduced.

Hypothesis 10 (H10): An intervention using the self-monitoring app leads to a reduction in food waste.

2.3. Participants

A priori power analysis was conducted using G*Power 3.1 (Faul et al., 2007, 2009) to determine the sample size required for verification. For two groups across three periods (baseline, intervention, and follow-up), with a moderate effect size f of 0.25 (Cohen, 1988), a significance level of 5% (α = 0.05), and a target power of 80% (1 – β = 0.8), the required sample size was calculated as 82 participants in total, requiring a minimum of 41 participants per group. For the two phases (pre- and post-intervention), 130 participants were required, necessitating a minimum of 65 per group.

We publicly recruited 130 individuals aged 30 years or older who managed their meals at home and lived in a household with two or more members. Recruitment was conducted in September 2024 through municipal newsletters, websites, and other channels in six municipalities in Kyoto Prefecture, and through press release websites in Japan. As a result, a total of 152 individuals applied from across Japan (88% female). Six individuals who could not be verified and 15 who had not disposed of any food waste in the past two weeks were excluded. Twenty participants were randomly selected and excluded from the particularly large number of applicants aged in their 30s. This resulted in a total of 110 accepted applicants (39 in their 30s, 36 in their 40s, 29 in their 50s, and 6 aged 60 or older). Due to the low number of applicants in their 60s, 20 participants were recruited from a research company panel, bringing the total to 26 in this age group. This resulted in a total of 130 selected participants. Withdrawals and dropouts left a final panel of 126 participants. Participants who completed the entire study period and who responded to all three questionnaire surveys received a compensatory gift certificate worth 6,000 yen.

2.4. Methods

A six-week experiment was conducted between October 2024 and March 2025. During the six-week experimental period, the amount of food waste was measured by all participants by separating avoidable food waste into designated waste bins. The first part of this study comprised four consecutive weeks, including a two-week baseline period for measurement only, followed by a two-week intervention period during which the intervention group used the self-monitoring app. Approximately three months after the end of the intervention period, a two-week follow-up period was established, again focusing solely on measurement as during the baseline period.

As the intervention group, 63 households were selected by systematic sampling, aiming to achieve as much balance as possible across age, gender, household size, and frequency of food waste disposal reported in the pre-study questionnaire. The remaining 63 households were assigned to the control group.

The intervention involved providing a briefing session to the intervention group participants as described in

Section 2.1.3. Subsequently, during the two-week intervention period, participants were asked to use the self-monitoring app described in

Section 2.1.4 as a non-informational intervention. Meanwhile, the control group participants were asked to continue their baseline lifestyle unchanged during the intervention period.

During the follow-up period approximately three months after the end of the intervention period, participants in both groups were asked to continue their lifestyles prior to the follow-up period while placing any food waste generated into a dedicated waste bin.

2.5. Food Waste Definition and Measurement Method

In this study, food waste was defined as avoidable food waste, consistent with Seta et al. (2025), and included unused food and leftovers as defined by Okayama et al. (2021). Food waste in this study basically followed the definition of the Japanese government, which is food that is edible but discarded. However, for measurement purposes, participants were asked not to place liquids in the dedicated waste bins. Regarding containers and packaging, if they were lighter than the food itself, they were to be placed in the waste bin as is. If the food contents were lighter than the packaging, participants were asked to remove the packaging and to discard the food contents only. While the Japanese government’s definition includes excessive removal (see Note 1) in food waste, this study did not include it. The measurement method was explained during an online briefing session for all participants before the baseline period began (with the opportunity to view a video as well). Leaflets summarizing the content of the briefing session were also distributed to all the participants’ households.

To measure food waste, the cloud-based measurement method adopted by Seta et al. (2025) was used. Specifically, a system combining a 20 L waste container with a mat-type automatic weighing device was used, and measurement data was transmitted and collected in the cloud system through a Wi-Fi router.

Note 1. Excessive removal refers to the removal of edible parts during the process of removing inedible parts, such as peeling vegetables too thickly.

2.6. Questionnaire Surveys

The questionnaire surveys were essentially the same as those used by Seta et al. (2025) and were conducted online using Google Forms. The surveys were administered three times: before the experiment began, after the intervention, and after the follow-up period ended. The surveys asked about the extent to which participants had practiced food waste reduction behaviors over the past two weeks, as well as their awareness and motivations regarding food waste and dietary habits. The questions also covered refrigerator content management and food waste disposal frequency. Participants in the intervention group were also asked to evaluate the intervention measures.

2.7. Internet Survey by Online Panels

To determine whether the measurement method adopted in this study had an impact on the subjects’ behavior, questionnaire surveys using online panels without food waste measurement were administered in parallel with the experiment described in

Section 2.4. Online panels were selected through a screening survey to match the conditions of the experimental participants, resulting in 130 individuals, 88 of whom responded to all three surveys. The questionnaire items were identical to those used in the experiment, except for questions directly related to the experiment, and the response period was the same as that for the experimental participants.

2.8. Analysis

This study focused its analysis on data from the baseline and intervention periods to emphasize the direct impact of the intervention. To analyze the intervention effect, a two-way mixed ANOVA was used. This design treated the food waste amount measured by the cloud-based measurement system and the degree of implementation of 13 food waste reduction behaviors (5-point scale) as dependent variables, with group (intervention group and control group) and period (baseline and intervention) as factors. This allowed verification of the intervention's effect on food waste amount and its effect on food waste reduction behaviors. Regarding the relationship between behaviors and food waste amount, correlation analyses were performed for the change in food waste amount (pre-intervention − post-intervention) and the change in 13 behaviors (pre-intervention − post-intervention). IBM SPSS Statistics 29 was used for the analyses.

This study was reviewed by the Ethics Committee of Kyoto Prefectural University and approved on August 30, 2024 (Application No. 320).

3. Results

3.1. Changes in Food Waste and Effects of the Self-Monitoring App Intervention

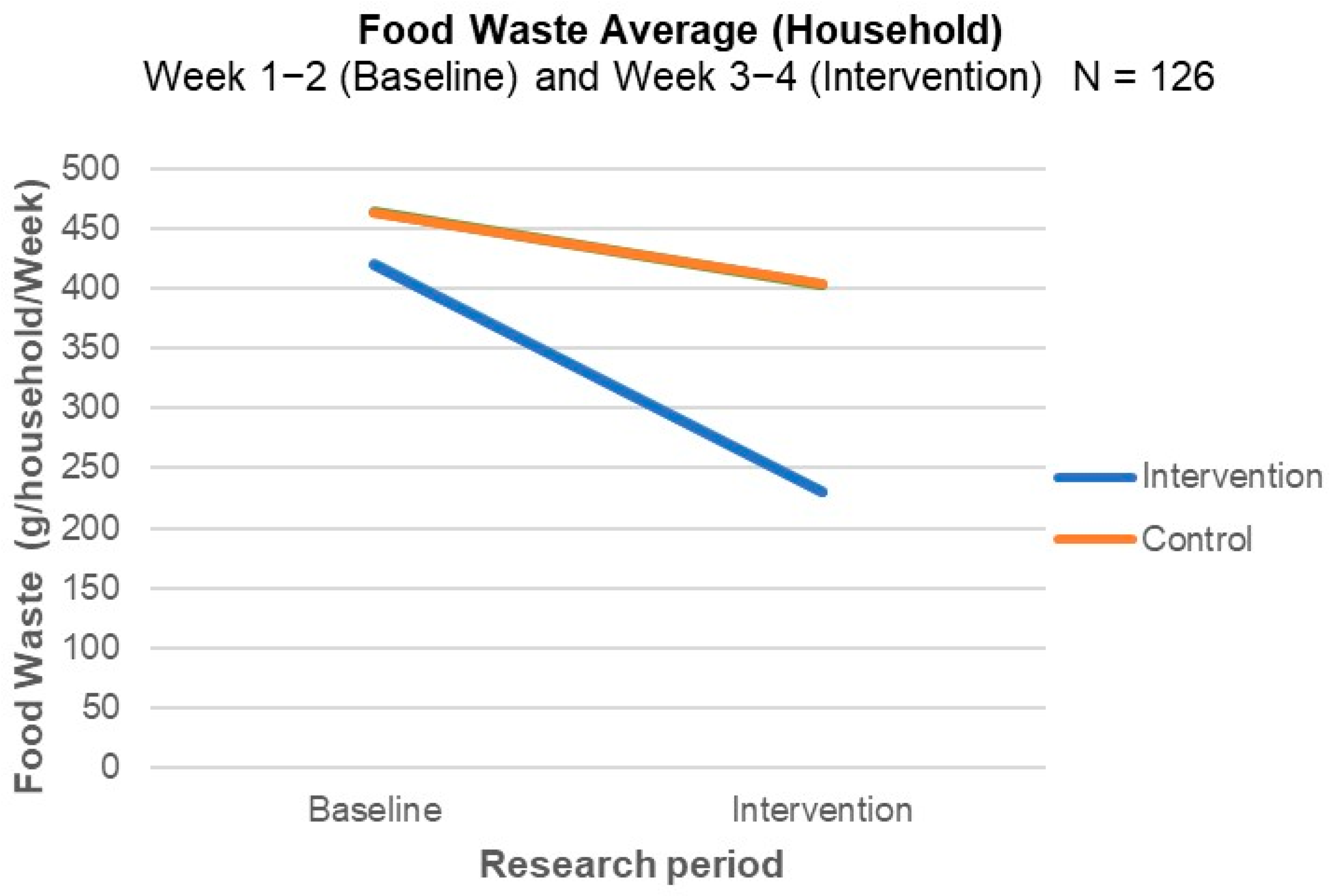

Figure 3 shows the average food waste amount per household per week during the baseline and intervention periods for the intervention and control groups. The intervention group reduced food waste by 190 g per household per week (45% reduction) after the intervention. The interaction in a two-way mixed ANOVA (F(1,124) = 3.124,

p = 0.080) showed a marginally significant effect. The simple main effect for the intervention group (−189.4**) was significant, albeit with a small effect size (

d = 0.341). In contrast, the control group reduced food waste by 60 g per household per week (13% reduction). The reduction was relatively small compared with that in the intervention group, and the simple main effect was not significant. Hence, H10 (an intervention using the self-monitoring app leads to a reduction in food waste) was supported to some extent.

Symbols indicating the significance level of the analysis results for mean differences are as follows: ** < 1%, * < 5%, + < 10%.

3.2. Effects of Food Waste Measurement

A cloud-based automatic weighing system was used to measure the amount of food waste. However, 79% of the intervention group and 70% of the control group responded that separating food waste and using the dedicated bins “greatly influenced” or “somewhat influenced” their food waste reduction behavior. To analyze the impact of food waste measurement on the intervention and control groups, the frequency of food waste disposal among online panels, as described in

Section 2.7, was measured using the same questions as for the control group. A two-way mixed ANOVA was conducted using the waste frequency data from the experimental control group and the online panels before and after the intervention period. The results showed no significant effect on leftovers from served meals (F(1,146) = 0.012,

p = 0.912), leftovers from unserved meals (F(1,142) = 0.340,

p = 0.561), unused fresh food (F(1,143) = 1.238,

p = 0.268), or unused items (F(1,147) = 0.143,

p = 0.706).

We also analyzed differences in disposal frequency between the intervention and control groups, and we found a significant interaction for unused fresh food (F(1,120) = 9.513, p = 0.003). The mean difference in the simple main effect was −0.233* for the intervention group, indicating a significantly lower rate after the intervention, whereas the control group showed a significantly higher rate of 0.274*. For leftovers from served meals, the mean difference for the intervention group was −0.323*, indicating a significantly lower rate than that for the control group, but the interaction was not significant.

3.3. Effects of the Intervention on Food Waste Reduction Behaviors and Their Association with Food Waste Reduction

Table 1 shows the effects of the intervention on 13 food waste reduction behaviors and the relationships between changes in these behaviors and changes in the amount of food waste. For each behavior, the interaction and simple main effects from the two-way mixed ANOVA are shown, as well as the correlation coefficients between behavioral changes and changes in food waste. Each behavior was classified into action types and linked to hypotheses. Furthermore, hypotheses related to food waste reduction behaviors (H1–H9) were tested based on the results in

Table 1. A hypothesis was considered supported if the analysis results for all related actions were significant. If all or some related actions showed marginal significance (

p < 0.10) and/or some were significant, the hypothesis was considered partially supported. If none of the results reached marginal significance, the hypothesis was considered not supported. The test results are shown in

Table 2.

Among the four target behaviors, behaviors related to “search” and “move” showed significant interactions and simple main effects, supporting both H1 and H2. The interaction and simple main effect of “Frequency of organizing the refrigerator”, which is related to “search” and “move”, were also significant. H4, which is related to the third target behavior “use”, was partially supported. While the interaction for “Used food that should be eaten quickly as a priority” was not significant, both the interaction and simple main effect for “Used up food in the refrigerator” were significant. H5 was considered not supported, as the correlation between the change in the three behaviors measured in the usage context (“Used food that should be eaten quickly as a priority”, “Used up food in the refrigerator”, and “Made a quantity that I could eat up”) and the change in food waste was not significant. Regarding the last target behavior, “Tried to eat up the food I cooked”, the interaction showed a marginally significant effect, and the simple main effect was significant. Thus, H8 was partially supported. Furthermore, H9 was supported because the correlation between changes in “Tried to eat up the food I cooked” and changes in food waste was significant. For H3, concerning inventory knowledge, the interaction and simple main effect of the two behaviors related to refrigerator inventory knowledge, “Knew inventory in the refrigerator” and “Kept track of the expiration dates” were significant, but inventory knowledge during shopping, “Had trouble recalling food inventory at home” was not significant, so H3 was partially supported. Regarding purchasing behavior, H6 and H7 showed significant interactions and simple main effects for duplicate purchases and purchase quantity, “Bought the same item twice” and “Was careful how much I bought”, but not for excessive purchase suppression, “Bought too much”. Since the correlation between excessive purchase suppression and food waste quantity was significant, both hypotheses were partially supported.

3.4. Evaluation of the Self-Monitoring App by Participants

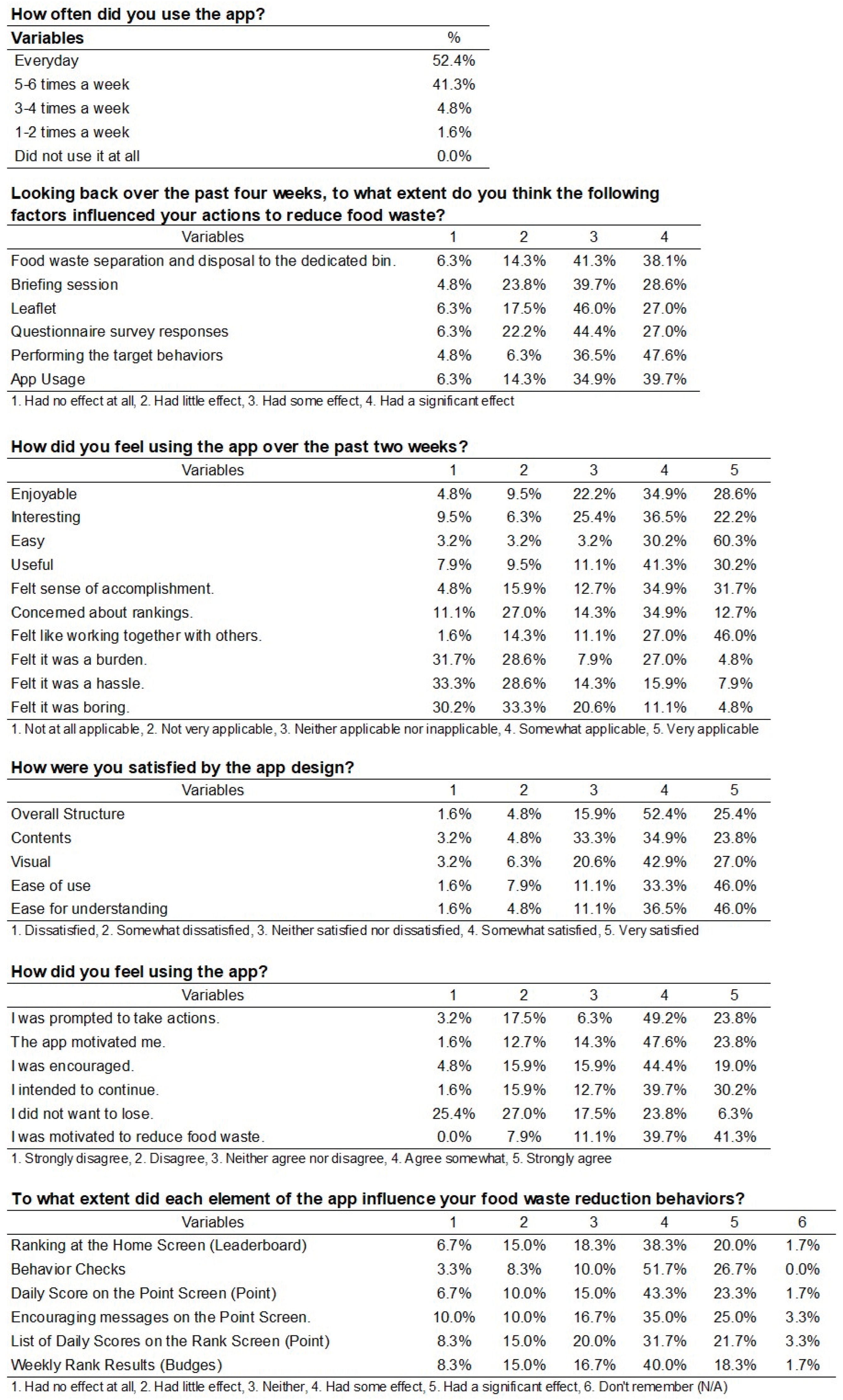

The participants in the intervention group were asked about their usage levels and their evaluation of the effectiveness and usability of the self-monitoring app. The results are shown in

Appendix A. Descriptions in this section we combined the highest and the second highest scales (e.g. “had a significant effect” and “had some effect”). The vast majority (94%) used the app five or more times per week and 75% of participants reported being influenced by using the self-monitoring app. As for the impacts of specific app features, 78% of the participants rated “Behavior checks” as influential, 67% rated “Daily score” as influential, 60% rated “Encouraging messages” as influential, 58% rated “Leaderboard” as influential, and 58% rated “Badges” as influential. Regarding the perceived burden of app use, 24% “Felt it was a hassle” and 32% “Felt it was a burden”. Conversely, positive evaluations related to ease of use were high, with 90% choosing “Easy”, 83% “Ease of understanding”, and 79% “Ease of use”. For impressions of the app, “Made me want to reduce food waste” (81%) was the highest, followed by “Prompted me to take actions” (73%) and “Motivated me” (71%). Regarding awareness related to others, 30% of the participants selected “I didn’t want to lose”, 48% selected “I paid attention to the rankings”, and 73% selected “I felt like I was working together with others”.

4. Discussion

4.1. Impact of the Intervention on Target Behaviors and Effectiveness in Reducing Food Waste

We were concerned that the act of measurement (the requirement to dispose of avoidable food waste separately in a designated bin) might affect the results rather than the effects of the intervention. However, as shown in

Section 3.2, while the food waste measurement had a psychological impact on participants in the control group, it had little effect on the frequency of food waste disposal and the results suggest that its impact on the amount of food waste was also minimal.

As shown in

Section 3.3, the intervention significantly increased two of the four target behaviors, namely “search” and “move”. These behaviors led to increased refrigerator organization frequency and improved inventory knowledge, including knowledge about expiration dates and the amount of stock. These effects may have influenced shopping behavior, with participants potentially avoiding duplicate purchases and paying more attention to purchase quantity. In the usage stage, “eat up the food” and “use up the foods” were significant. In summary, many behaviors related to reducing food waste appeared to be influenced by the intervention using the self-monitoring app.

Nine of the ten hypotheses in this study were supported or partially supported. The only hypothesis not supported was H5, which concerned “priority use”. In our previous study (Seta et al., 2025), “priority use” also had no significant interaction effect, but the mean difference in simple main effects was significant for the group that used smartphones to take pictures inside of the refrigerator and marginally significant for the food management app group, with a significant correlation with food waste quantity. In this study, the baseline mean score for “priority use” in the intervention group was 4.083, the highest among groups in this and previous experiments. Consequently, there was limited room for improvement through the intervention, which may have weakened the observed relationship between behavioral change and food waste reduction.

In our previous study (Seta et al., 2025), pre- and post-intervention differences in food waste amount (g/household/week), reduction rates, and effect sizes (Cohen’s

d) were as follows: organizing tools (176 g, 51%, 0.695), photos (177 g, 43%, 0.519), and app (129 g, 29%, 0.379). The values for this study (190 g, 45%, 0.341) reported in

Section 3.1 indicate a reduction rate comparable to that of the photos group in Seta et al. (2025) and an effect size comparable to that of the app group. Furthermore, in Soma et al. (2020), the food waste reduction per person for the game group was approximately 30%, which was lower than the reduction achieved in this study. The intervention in this study achieved effects generally equivalent to or superior to those of the app intervention in Seta et al. (2025) or the game group in Soma et al. (2020).

4.2. Effect of Gamification on Motivation

Based on the participants’ app evaluations shown in

Section 3.4, many participants were influenced by the self-monitoring and game elements included in the app, which prompted behaviors and led to motivation.

In Soma et al. (2020), participants earned points by correctly answering quizzes, and the value of the coupons they received varied based on the number of points earned. This suggests the influence of economic incentives. In contrast, in this study, all the participants received the same gift certificate as compensation, regardless of the ranking or the points they earned. Despite the absence of economic incentives, many participants in the intervention group were motivated by points, suggesting that the psychological reward of points was effective for motivation. The points and praise earned with each daily self-evaluation using the self-monitoring app, along with the leaderboard displayed on the home screen (that is, the use of gamification), appeared to increase motivation, impact food waste reduction behaviors, and lead to reduced food waste. Although the leaderboard was intended to increase motivation by fostering competitiveness, only 30% of the participants reported feeling competitive, whereas 73% felt that they were working together with others. Given that participants could only recognize others when viewing the leaderboard, it is plausible that the leaderboard in this study promoted a greater sense of collaborative engagement rather than competition (Morschheuser et al., 2019; Riar et al., 2022; Grech et al., 2024). Gamification is recognized as beneficial not only for personal motivation but also as a method to induce and sustain collective, cooperative behavior, such as cooperative actions among strangers in online games (Koivisto & Hamari, 2019). This finding is consistent with prior research.

4.3. Effect of Reducing Burden

The perceived burden of the intervention was a problem identified in our previous study (Seta et al., 2025). In this study, 32% of the participants reported feeling burdened by the app and 24% felt it was troublesome. In contrast, the previous study found that a majority (77%) of food management app users perceived the app’s activities as troublesome. The intervention in this study halved the incidence of these feelings, suggesting that it effectively reduced the perceived burden. High ratings for “easy”, “understandable”, and “user-friendly” also suggest a reduction in psychological burden.

5. Conclusions

This study aimed to reduce household food waste by targeting four behaviors, namely, “search”, “move”, “use”, and “finish meals”. The first three behaviors had their effectiveness proven in Seta et al. 2025, and the last one was added in this study. To directly encourage these target behaviors while reducing the perceived burden of the ICT tool and increasing motivation, we designed and conducted an intervention experiment using a gamified food waste behavior self-monitoring app. To evaluate its effectiveness, a cloud-based weighing system was used to measure food waste amount.

The average weekly food waste amount per household decreased by 190 g (45%) in the intervention group. A two-way mixed ANOVA showed a marginally significant interaction effect, suggesting that the intervention had a modest but meaningful effect on reducing food waste. Compared to the food waste reduction rates and effect sizes (d) in Seta et al. (2025), the self-monitoring app demonstrated effects generally equivalent to those of food management apps and photo-based approaches. Furthermore, analyzing the impact of food waste reduction behaviors and testing hypotheses revealed that the intervention encouraged the target behaviors “search” and “move”, leading to a more organized refrigerator interior. This may have increased inventory awareness, curbing over-purchasing and promoting the behavior “finish meals”. Motivation was shown to increase due to the influence of game elements. Furthermore, participants’ perceived burden was lower compared to that in the Seta et al. (2025) intervention.

The contribution of this study lies in the use of self-monitoring, an intervention method rarely employed before, to directly promote food waste reduction behavior. The effectiveness of this intervention was rigorously examined through quantitative analysis utilizing a control group. Furthermore, this study is one of few in this field to utilize gamification, demonstrating that psychological rewards alone can be effective, without economic incentives. These findings are expected to contribute to future ICT-based interventions and policy development.

6. Limitations

A primary limitation of the current study is that the intervention effects were only examined at the individual level. Examining the intervention effects on group-level efforts (e.g., in neighborhood or other community groups) remains an important topic for future research. Furthermore, the study targeted individuals who voluntarily applied to participate, so the sample may not be representative of Japan’s population, as many participants may already have had some motivation to reduce their food waste. Finally, although the study included a follow-up period of approximately three months after the intervention, it did not address long-term effects. Discussions on long-term effects will be reported separately.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported financially by the Environment Research and Technology Development Fund (JPMEERF20223M03) of the Environmental Restoration and Conservation Agency of the Ministry of Environment of Japan.

Detritus is the journal to which this paper has been submitted.

Funding

This research was supported financially by the Environment Research and Technology Development Fund (JPMEERF20223M03) of the Environmental Restoration and Conservation Agency of the Ministry of Environment of Japan.

Ethical Approval

This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Kyoto Prefectural University (Application No. 320, 30 August 2024).

Data Availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Preprint Statement

This manuscript has been submitted to Detritus Journal for peer review. The editorial office has approved posting this preprint on a preprint platform during the review process. The manuscript constitutes an important part of the author’s doctoral dissertation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all study participants for their cooperation and the technical staff involved in the development of the gamified self-monitoring app.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Responses of the Intervention Group to the Post-Study Survey on the Self-Monitoring App (N = 63).

References

- Boulet, M., & Lauren, N. (2024). Nudging Householders to Reduce Avoidable Food Waste: The OzHarvest Use It Up Tape. Sustainability, 16(12), 5132. [CrossRef]

- Casonato, C., García-Herrero, L., Caldeira, C., & Sala, S. (2023). What a waste! Evidence of consumer food waste prevention and its effectiveness. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 41, 305–319. [CrossRef]

- Castro, C., Chitikova, E., Magnani, G., Merkle, J., & Heitmayer, M. (2023). Less Is More: Preventing Household Food Waste through an Integrated Mobile Application. Sustainability, 15(13), 10597. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed). L. Erlbaum Associates.

- Cooper, A., Lion, R., Rodriguez-Sierra, O. E., Jeffrey, P., Thomson, D., Peters, K., Christopher, L., Zhu, M. J. H., Wistrand, L., Van Der Werf, P., & Van Herpen, E. (2023). Use-up day and flexible recipes: Reducing household food waste by helping families prepare food they already have. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 194, 106986. [CrossRef]

- Deterding, S., Dixon, D., Khaled, R., & Nacke, L. (2011). From game design elements to gamefulness: Defining “gamification.” Proceedings of the 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference on Envisioning Future Media Environments - MindTrek ’11, 9. [CrossRef]

- European Commission Joint Research Centre (2023). Evaluation of consumer food waste prevention interventions. Publications Office. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2760/224541.

- FAO. (2013). Food wastage footprint: Impacts on natural resources: summary report. FAO.

- Farr-Wharton, G., Choi, J. H.-J., & Foth, M. (2014a). Food talks back: Exploring the role of mobile applications in reducing domestic food wastage. Proceedings of the 26th Australian Computer-Human Interaction Conference on Designing Futures: The Future of Design, 352–361. [CrossRef]

- Farr-Wharton, G., Choi, J. H.-J., & Foth, M. (2014b). Technicolouring the fridge: Reducing food waste through uses of colour-coding and cameras. Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Mobile and Ubiquitous Multimedia - MUM ’14, 48–57. [CrossRef]

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A.-G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 1149–1160. [CrossRef]

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. [CrossRef]

- Ganglbauer, E., Fitzpatrick, G., & Comber, R. (2013). Negotiating food waste: Using a practice lens to inform design. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, 20(2), 1–25. [CrossRef]

- Ganglbauer, E., Fitzpatrick, G., & Güldenpfennig, F. (2015). Why and what did we throw out?: Probing on Reflection through the Food Waste Diary. Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1105–1114. [CrossRef]

- Ganglbauer, E., Fitzpatrick, G., & Molzer, G. (2012). Creating visibility: Understanding the design space for food waste. Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Mobile and Ubiquitous Multimedia, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Grech, E. M., Briguglio, M., & Said, E. (2024). A field experiment on gamification of physical activity – Effects on motivation and steps. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 184, 103205. [CrossRef]

- Guo, L. (2022). The effects of self-monitoring on strategy use and academic performance: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Educational Research, 112, 101939. [CrossRef]

- Haas, R., Aşan, H., Doğan, O., Michalek, C. R., Karaca Akkan, Ö., & Bulut, Z. A. (2022). Designing and Implementing the MySusCof App—A Mobile App to Support Food Waste Reduction. Foods, 11(15), 2222. [CrossRef]

- Hamari, J., Koivisto, J., & Sarsa, H. (2014). Does Gamification Work? -- A Literature Review of Empirical Studies on Gamification. 2014 47th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, 3025–3034. [CrossRef]

- Hartikainen, H., Kostensalo, J., & Riipi, I. (2025). Tackling the challenges of food waste diary studies—Testing strategies with Finnish data. Waste Management, 202, 114844. [CrossRef]

- Hebrok, M., & Boks, C. (2017). Household food waste: Drivers and potential intervention points for design – An extensive review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 151, 380–392. [CrossRef]

- Huotari, K., & Hamari, J. (2017). A definition for gamification: Anchoring gamification in the service marketing literature. Electronic Markets, 27(1), 21–31. [CrossRef]

- Jobson, D., Karunasena, G. G., Nabi, N., Pearson, D., & Dunstan, E. (2024). A Systematic Review of Pre-Post Studies Testing Behaviour Change Interventions to Reduce Consumer Food Waste in the Household. Sustainability, 16(5), 1963. [CrossRef]

- Koivisto, J., & Hamari, J. (2019). The rise of motivational information systems: A review of gamification research. International Journal of Information Management, 45, 191–210. [CrossRef]

- Kyewski, E., & Krämer, N. C. (2018). To gamify or not to gamify? An experimental field study of the influence of badges on motivation, activity, and performance in an online learning course. Computers & Education, 118, 25–37. [CrossRef]

- Landers, R. N., Bauer, K. N., & Callan, R. C. (2017). Gamification of task performance with leaderboards: A goal setting experiment. Computers in Human Behavior, 71, 508–515. [CrossRef]

- Leverenz, D., Moussawel, S., Maurer, C., Hafner, G., Schneider, F., Schmidt, T., & Kranert, M. (2019). Quantifying the prevention potential of avoidable food waste in households using a self-reporting approach. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 150, 104417. [CrossRef]

- Mathisen, T. F., & Johansen, F. R. (2022). The Impact of Smartphone Apps Designed to Reduce Food Waste on Improving Healthy Eating, Financial Expenses and Personal Food Waste: Crossover Pilot Intervention Trial Studying Students’ User Experiences. JMIR Formative Research, 6(9), e38520. [CrossRef]

- Michie, S., Abraham, C., Whittington, C., McAteer, J., & Gupta, S. (2009). Effective techniques in healthy eating and physical activity interventions: A meta-regression. Health Psychology, 28(6), 690–701. [CrossRef]

- Morrow, A., Walker, K., Calder-MacPhee, N., & Ozakinci, G. (2022). The active ingredients of physical activity and / or dietary workplace-based interventions to achieve weight loss in overweight and obese healthcare staff: A systematic review. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 45(3), 331–349. [CrossRef]

- Morschheuser, B., Hamari, J., & Maedche, A. (2019). Cooperation or competition – When do people contribute more? A field experiment on gamification of crowdsourcing. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 127, 7–24. [CrossRef]

- Nkwo, M., Suruliraj, B., & Orji, R. (2021). Persuasive Apps for Sustainable Waste Management: A Comparative Systematic Evaluation of Behavior Change Strategies and State-of-the-Art. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence, 4, 748454. [CrossRef]

- Nonomura, M. (2020). Consumers and Household Food Waste: Attitudes, Behaviors, and Food Waste Reduction Interventions. Material Cycles and Waste Management Research, 31(4), 253–261. [CrossRef]

- Okayama, T., Watanabe, K., & Yamakawa, H. (2021). Sorting Analysis of Household Food Waste—Development of a Methodology Compatible with the Aims of SDG12.3. Sustainability, 13(15), 8576. [CrossRef]

- Ölander, F., & ThØgersen, J. (1995). Understanding of consumer behaviour as a prerequisite for environmental protection. Journal of Consumer Policy, 18(4), 345–385. [CrossRef]

- Orji, R., & Moffatt, K. (2018). Persuasive technology for health and wellness: State-of-the-art and emerging trends. Health Informatics Journal, 24(1), 66–91. [CrossRef]

- Page, E. J., Massey, A. S., Prado-Romero, P. N., & Albadawi, S. (2020). The Use of Self-Monitoring and Technology to Increase Physical Activity: A Review of the Literature. Perspectives on Behavior Science, 43(3), 501–514. [CrossRef]

- Pelt, A., Saint-Bauzel, R., Barbier, L., & Fointiat, V. (2020). Food waste: Disapproving, but still doing. An evidence-based intervention to reduce waste at household. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 162, 105059. [CrossRef]

- Porpino, G. (2016). Household Food Waste Behavior: Avenues for Future Research. Journal of the Association for Consumer Research, 1(1), 41–51. [CrossRef]

- Ramos, G. J., Borges, J. A. R., Domingues, C. H. D. F., & Van Herpen, E. (2024). Reducing food waste by simply measuring it: Insights from interventions to reduce household food waste. British Food Journal, 126(2), 812–833. [CrossRef]

- Riar, M., Morschheuser, B., Zarnekow, R., & Hamari, J. (2022). Gamification of cooperation: A framework, literature review and future research agenda. International Journal of Information Management, 67, 102549. [CrossRef]

- Santos, E., Sevivas, C., & Carvalho, V. (2025). Managing Food Waste Through Gamification and Serious Games: A Systematic Literature Review. Information, 16(3), 246. [CrossRef]

- Seta, Y., Yamakawa, H., Okayama, T., Watanabe, K., & Nonomura, M. (2025). The Effects of Interventions Using Support Tools to Reduce Household Food Waste: A Study Using a Cloud-Based Automatic Weighing System. Sustainability, 17(14), 6392. [CrossRef]

- Simões, J., Carvalho, A., & Gaspar De Matos, M. (2022). How to influence consumer food waste behavior with interventions? A systematic literature review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 373, 133866. [CrossRef]

- Soma, T., Li, B., & Maclaren, V. (2020). Food Waste Reduction: A Test of Three Consumer Awareness Interventions. Sustainability, 12(3), 907. [CrossRef]

- Soma, T., Li, B., & Maclaren, V. (2021). An evaluation of a consumer food waste awareness campaign using the motivation opportunity ability framework. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 168, 105313. [CrossRef]

- Stöckli, S., Niklaus, E., & Dorn, M. (2018). Call for testing interventions to prevent consumer food waste. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 136, 445–462. [CrossRef]

- United Nations. (2015). General Assembly. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda.

- Van Der Werf, P., Seabrook, J. A., & Gilliland, J. A. (2021). “Reduce Food Waste, Save Money”: Testing a Novel Intervention to Reduce Household Food Waste. Environment and Behavior, 53(2), 151–183. [CrossRef]

- Van Herpen, E., Wijnen, T., Quested, T., Reynolds, C., & Sharda, N. (2023). Convenient tools and social norms: Measuring the effectiveness of an intervention to reduce household food waste. Journal of Cleaner Production, 429, 139604. [CrossRef]

- Venessa, K., & Aripradono, H. W. (2023). Usage of Gamification and Mobile Application to Reduce Food Loss and Waste: A Case Study of Indonesia. Journal of Information Systems and Informatics, 5(1), 102–122. [CrossRef]

- Visschers, V. H. M., Wickli, N., & Siegrist, M. (2016). Sorting out food waste behaviour: A survey on the motivators and barriers of self-reported amounts of food waste in households. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 45, 66–78. [CrossRef]

- Vogels, J. W. P. M., van der Haar, S., Zeinstra, G., & Bos-Brouwers, H. (2018). ICT tools for food management and waste prevention at the consumer level (No. D1.5; REFRESH, pp. 1–64). Available online: https://eu-refresh.org/sites/default/files/WP1.5%20report%20FINAL.pdf.

- von Kameke, C., & Fischer, D. (2018). Preventing household food waste via nudging: An exploration of consumer perceptions. Journal of Cleaner Production, 184, 32–40. [CrossRef]

- Wada, N., & Shinagawa, T. (2018). Relationship between Consumer’s Consciousness and Behavior on Food Waste in General Households. Journal of Environmental Information Science, 32, 179–184. [CrossRef]

- Waitt, G., & Phillips, C. (2016). Food waste and domestic refrigeration: A visceral and material approach. Social & Cultural Geography, 17(3), 359–379. [CrossRef]

- Yamakawa, H. (2020). Towards Policy Development for Preventing Household Food Waste. Material Cycles and Waste Management Research, 31(4), 262–272. [CrossRef]

- Zichermann, G., & Cunningham, C. (2011). Gamification by design: Implementing game mechanics in web and mobile apps. O’Reilly Media, Inc.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).