1. Introduction

Nutrition consists of food intake directly related to the body's needs. Life is maintained with food; it contains nutrients essential for growth, functionality [

1], protection [

2,

3], restoration of body issues [

4,

5], and regulation of metabolic processes in health and disease [

6,

7,

8]. Moreover, food is deeply integrated into people's social life. Homemade foods, for example, could be expressions of personal feelings that highlight interhuman relationships. Preparing and eating specific food are traditional aspects of various communities during the most significant lifetimes [

9,

10].

From farm to fork, a complex system involves linked processes of production, aggregation, processing, packaging, distribution, and disposal of final food products to potential consumers. However, while 9.2% of the global population (about 700 million people) live in extreme poverty and cannot afford daily food to survive, a third part of the food produced in the world is lost or wasted [

11]. FAO estimates that over 30-40% of total food production can be lost before market distribution due to inappropriate post-harvest storage, processing, or transportation (over 40-50% of root crops, fruits and vegetables, 30% of cereals and fish, and 20% of oilseeds). Other causes consist of food overproduction, which exceeds demands due to the availability of crop subsidies, and the safe food removal from the market or supermarket shelves due to urgent regulations [

11]. Finally, consumers who buy more food than their families can eat and their household habits could be other important factors that lead to food waste (FW). Therefore, the FAO proposed Save Food [

12], a global initiative involving numerous public and private sector partners in reducing loss and waste [

11].

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) marked September 29 as the International Day of Awareness of Food Loss and Waste (IDAFLW). This day significantly contributes to highlighting the emerging FW problem [

12]. Eurostat 2023 reported that around 10% of food for EU consumers (at retail, food services, and households) could be wasted. Over 37 million people cannot afford a quality meal every second day. UNEP Food Waste Index 2024 shows that around 1.05 billion tons of food waste were generated in 2022: 12% from retail, 28% from food services, and 60% from households. Considering FW per capita/year, Greece is in the highest position with 142 Kg, and Russia in the lowest, with 33 kg [

13], according to the United Nations Environment Program report from 2021.

Reducing FW is a substantial support against climate change because it has an enormous environmental impact, generating 16% of the total Greenhouse Gas emissions from the EU food system. Moreover, saving nutritive food for those in need, helping to eradicate hunger and malnutrition, and preserving money for households, companies, and farms could be other essential benefits of FW diminution [

12].

Celebrated annually in Romania on October 16, the National Day of Food and Combating Food Waste is an opportunity to remember that lack of food, hunger, and malnutrition can affect any country in the world and that global actions are needed to reduce the amount of wasted food. In Romania, Law No. 217/2016 on reducing food waste regulates the activity of economic operators in the agri-food sector. According to this law, food waste is when food leaves the human consumption circle due to degradation and is destroyed. Following the current legislation, consumers have access to reduced prices for food before they expire, and the procedure for food donations to non-governmental organizations has been simplified [

14]. Eurostat reports that Romanian households allocated 26.4% of total consumption expenditure to food and non-alcoholic beverages in 2020, while in the EU, the average is 14.8%. More than 4 million Romanians have difficulties in daily food purchases, while every year, a third of the food purchased is thrown away; food waste for our country was 70 Kg/per capita/year (as for the Czech Republic and Slovakia), estimated to be 1,353,077 tons/year, according to the report of the United Nations Environment Program [

13] from 2021. 70% of food waste comes from public catering, retail services, and households (over 50% – 47 million tons) [

13]. Thus, household food waste is one of the major obstacles to meeting global emission targets, and its level significantly varies within a year. For example, holiday marketing campaigns promote images of lavish meals and stocking up on various delicacies [

15], compared with the rest of the year. Thus, people buy more than they need or prepare exaggerated portions [

16,

17]. These practices often result in a wide variety of foods on the table, which may not be fully consumed. Lack of planning or knowledge of how to store and recycle food can lead to it being thrown away instead of used effectively.

Therefore, it is still hard to control the FW from households [

18,

19,

20]. In this context, the present study aims to investigate the food waste in Romanian households. It also evaluates the attitudes, respondents' behaviors, knowledge, and perceptions about food waste by obtaining direct information from the participants.

4. Discussion

The adult participants (aged 18 to over 65) in the present study were divided into five age groups according to Employment Rate data indicators [

24], aiming to appreciate their financial status. Working-aged people are [18-64] years old: [18-24] is considered an early working age group, [25-54] is prime working, and [55-64] is older working. In 2023, in Romania, the employment rate for early workers [18-24] was 18.7%, while for the older ones [55-64] was 51.0%. The highest employment rate of the working-age population was registered for graduates of a higher level of education (89.8%), 65.6% of persons with a medium level of education, and 36.9% of low-level ones. The prime workers were divided into 3 different age groups (25-34, 35-44, and 45-54). Potential differences (involvement in postgraduate studies, family life leading to children < 18 years, more household members, different daily working programs, and incomes) are responsible for FB and FC behaviors and FW level. The age group over 65 includes pensioners – they generally have modest incomes and risks of potential health problems due to aging processes. In the present study, the respondents were personal contacts, colleagues, and relatives of research team members, predominating early and prime workers (93.66%) with high study levels (84.33%) from urban areas (88%).

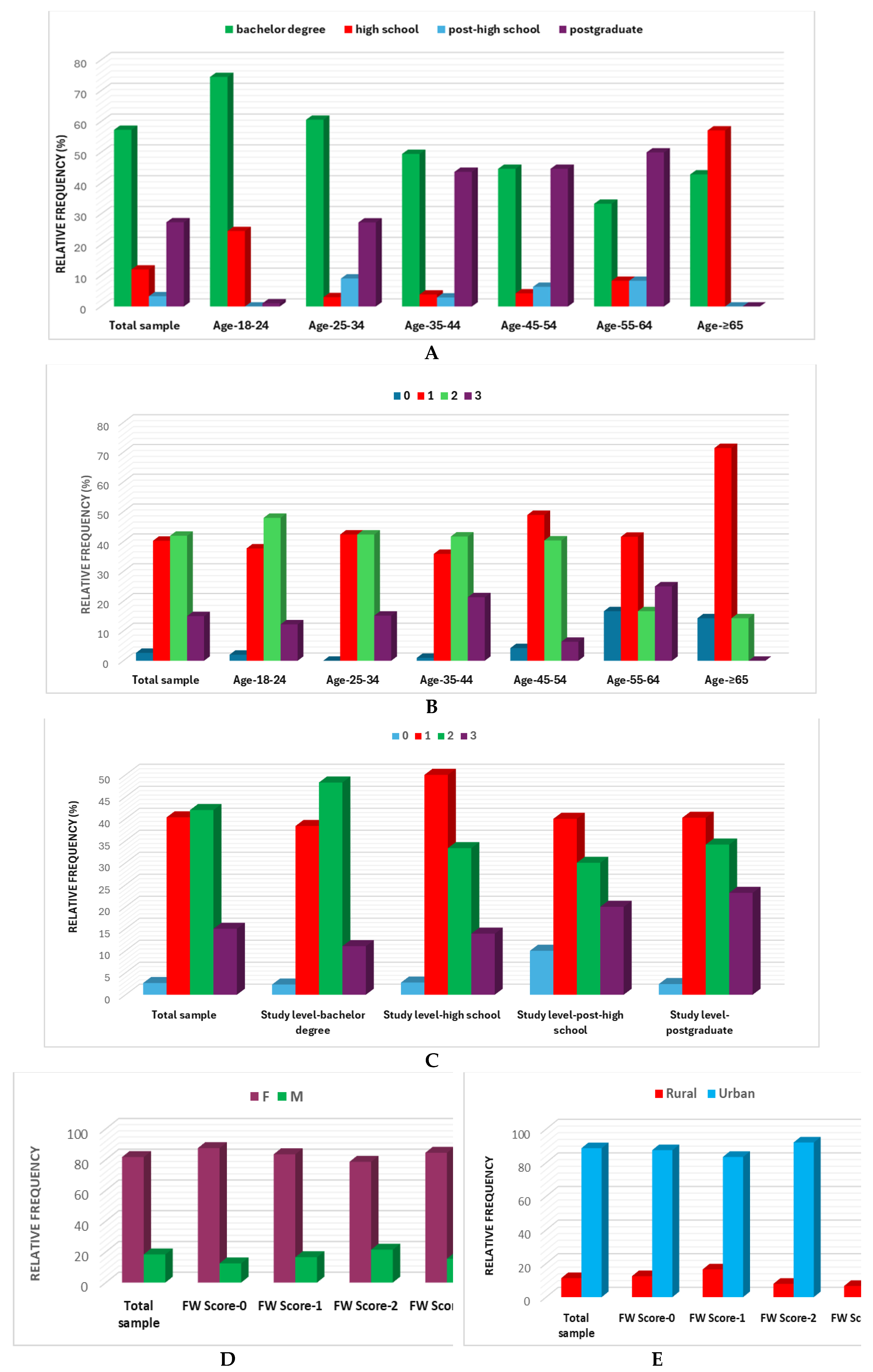

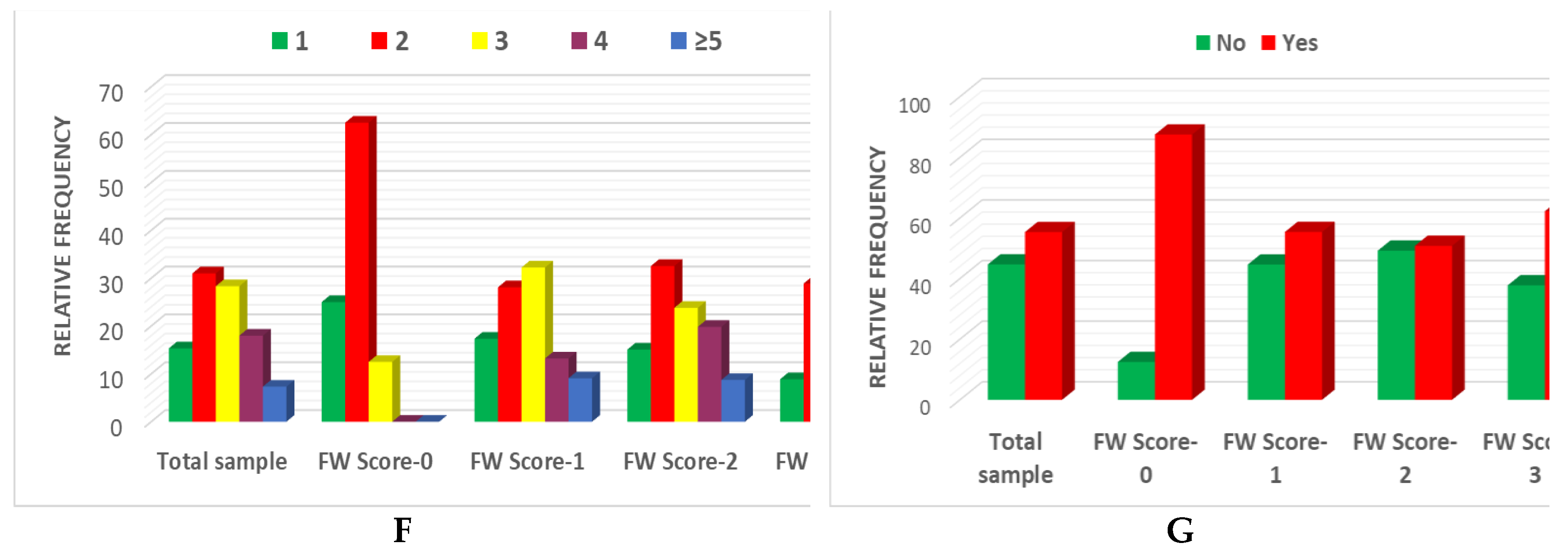

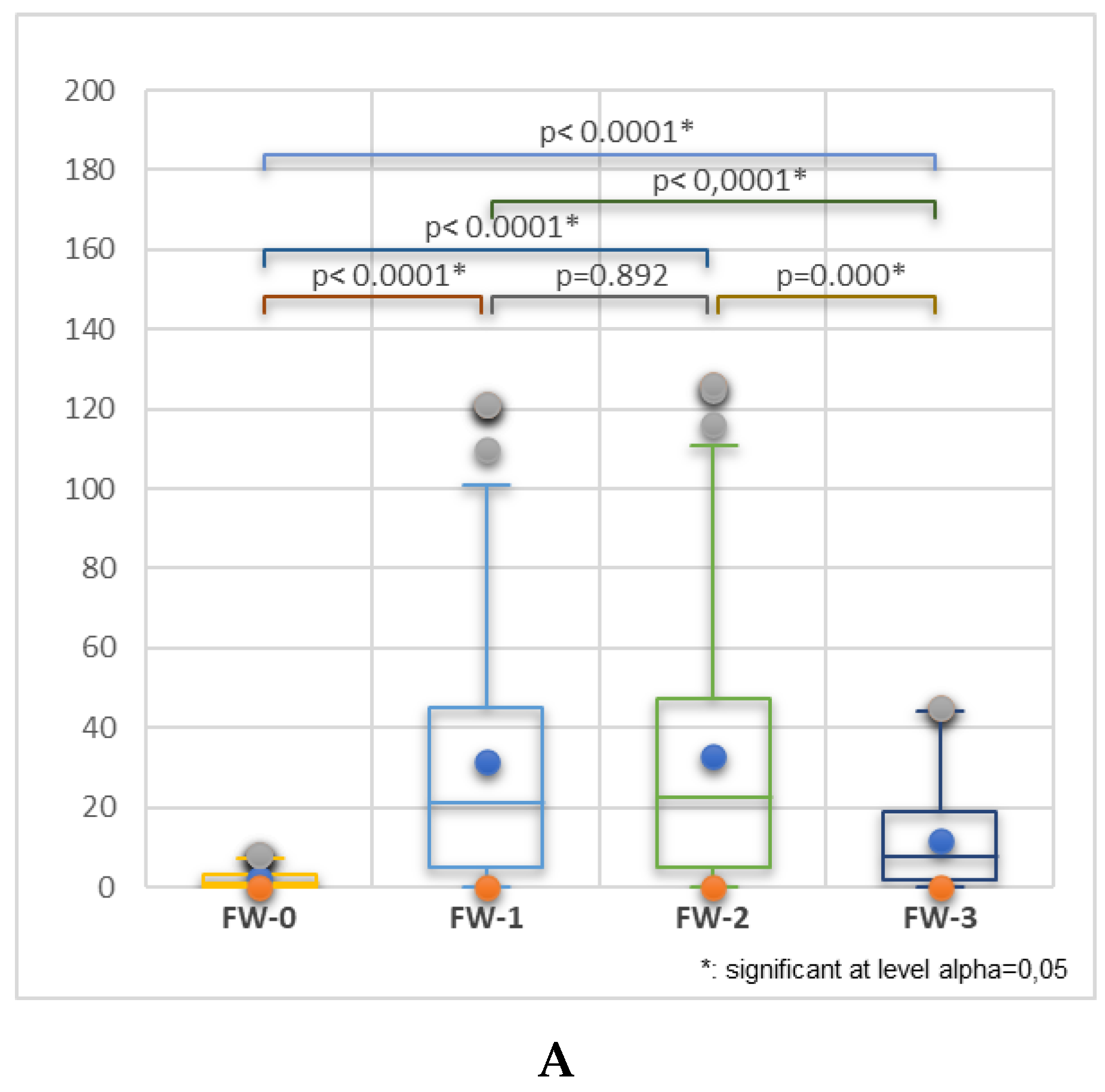

The factors mentioned above could explain our results regarding FW-level. It is significant (60.30%) in the [18-44] age group and considerably decreases with the age and employment status of participants - from 44.24% in the [45-64] active workers to 14.29% in >65 years old pensioners. Our results also show that males recorded higher FW levels than females (61.81% vs. 55.91%); the same for urban residency (59.39%) vs. rural (38.23%). Moreover, the FW level increases with study level (48.61% in high school studies vs. 58.31% in bachelor's degree). All data are similar to those reported in previous studies [

25] and fit with the representative individual profile for food waste in Romania: a male consumer under 35 years old, with a high study level of education, living alone in an urban zone [

26].

FP depends on a preferred diet. Adopting a healthier, more sustainable diet simplifies the food purchasing process. Planning meals involves a rigorous shopping list and avoiding the impulse to buy. Supporting local food producers through buying local food is a great help for farmers and small businesses in their communities. Understanding food labeling helps to avoid the ones with unhealthy ingredients. The substantial difference between "best before" and "use-by" dates refers to food safety - the "use-by" date inscription means that eating it after is not safe for the human body.

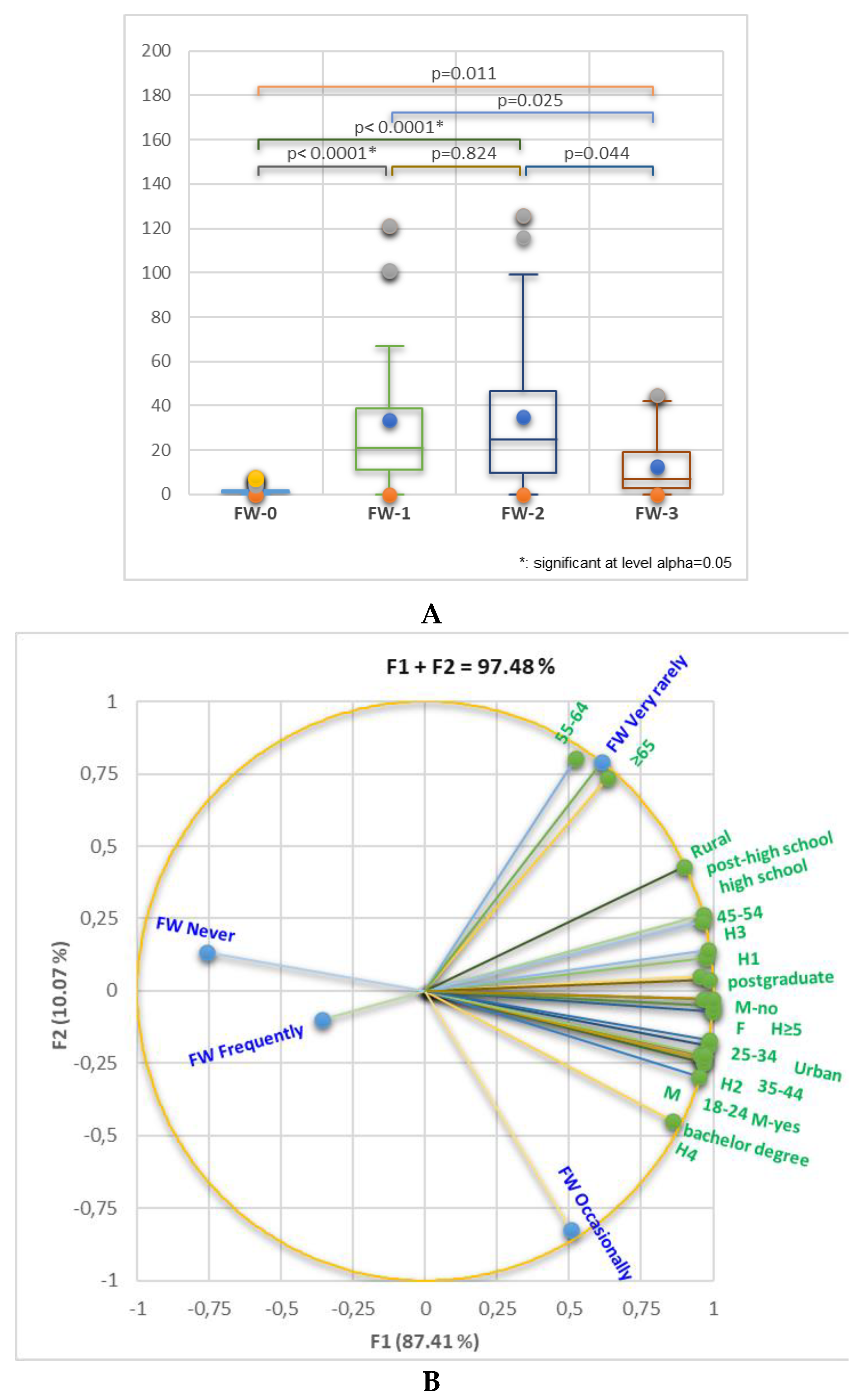

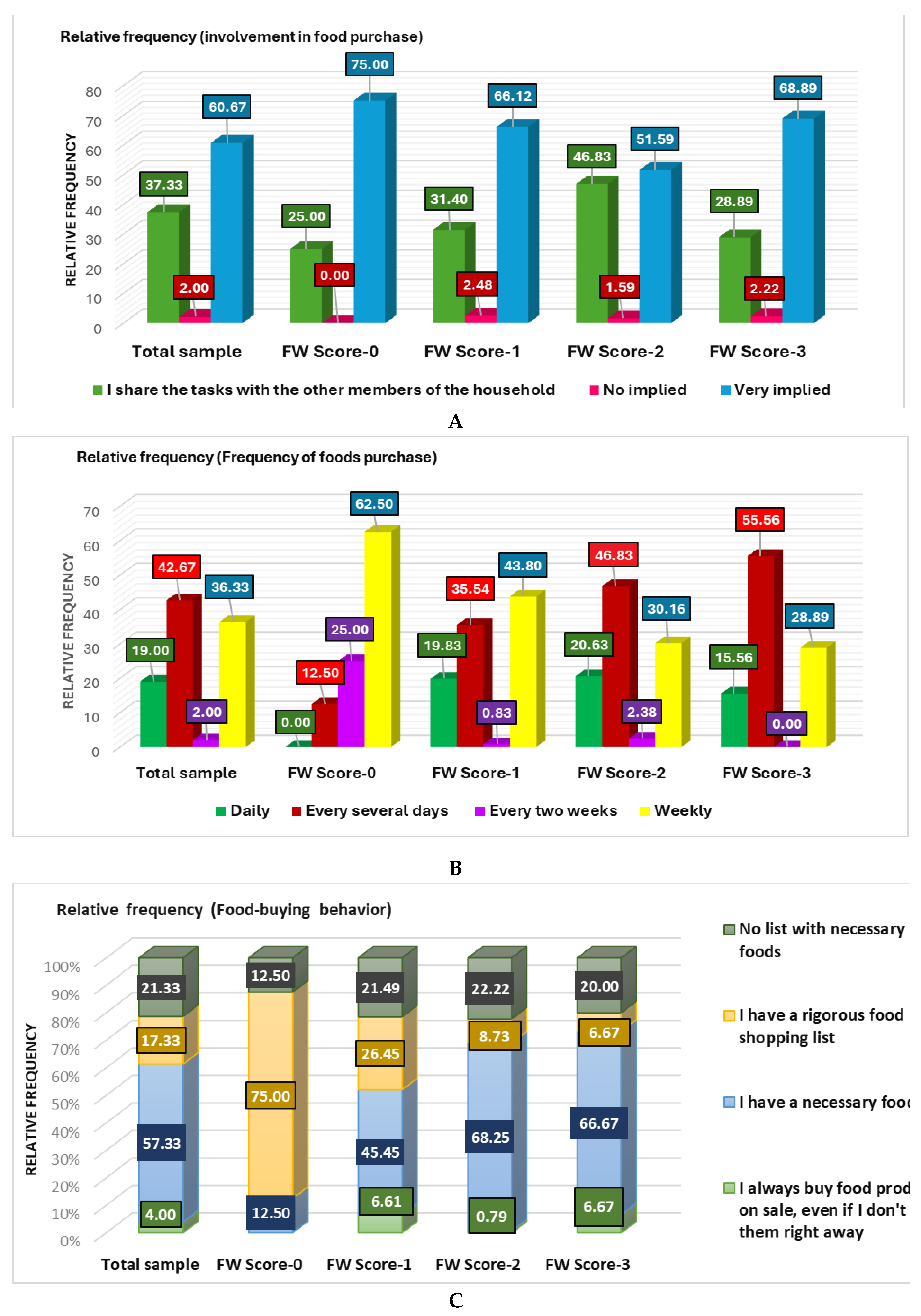

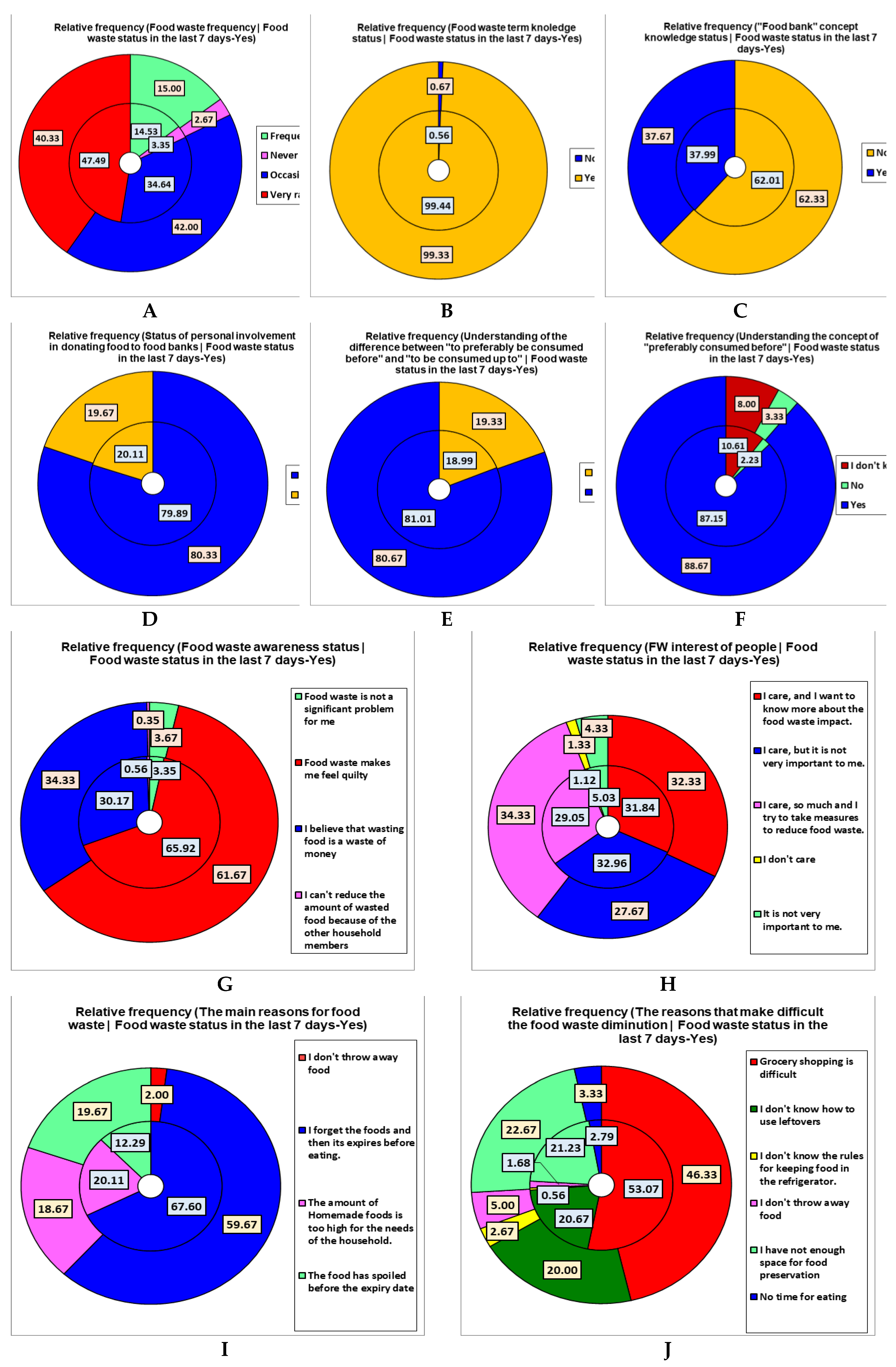

In our study, most of the respondents know about food waste (99.33%), understand the concept of "preferably consumed before "(88.66%), and "the difference between "to preferably be consumed before" and "to be consumed up to" (80.66%). Almost 66% of them are involved in FP; moderate differences were recorded between the groups with low frequency of waste food (FW-0 and FW-1) and those with higher frequency (FW-2 and FW-3): 75% and 66.12% vs. 51.595 and 68.89%. Of the cohort, 16% buy food daily, 42,67% every several days, 36,33% weekly, and 2% every 2 weeks. Most of the FW-0 group buy food weekly (62.50%), followed by FP every 2 weeks (25%) and every several days (12.5%). All FW-1 —FW-3 groups buy food daily (19.83% of FW-1, 20.63% of FW-2, and 15.56% of FW-3), every several days (in increasing order, 35.54% of FW-1, 46.83% of FW-2 and 55.56% of FW-3), weekly (in decreasing order, 43.80% of FW-1, 30.16% of FW-2 and 28.89% of FW-3) and every 2 weeks 0.83% of FW-1 and 2.38% of FW-2).

In the present study, of the total cohort, 57.33% have a shopping list but always buy other supplementary groceries, 17.33% have a rigorous shopping list and respect it, and 21.55% do not have a necessary food list. Only 4% declared, "I always buy food on sale, even if I don't use it right away." 75% of the FW-0 group have a rigorous shopping list. This percentage drastically decreases in order: FW-1 (26.45%), FW-2 (8.73%), and FW-3 (6.67%). The necessary food list always supplemented with other groceries is used by 45.45% of FW-1, and in similar percentages, by FW-2 and FW-3 (68.25% and 66.67%, respectively). No list stated all FW-1, 2, and 3 in similar percentages (21.49%, 22.22%, and 20.00%). "I always buy food on sale, even if I don't use it right away," stated only 0.79% of the FW-2 group and 6.61% and 6.67% of FW-1 and FW-3. 2.67% and 13.33% of the total cohort always and frequently buy food on sale. Surprisingly, the highest percentages were recorded in the FW-0 group (12.5% and 25% respectively). On the other hand, FW-0 has the highest percentage of respondents that "never buy food-on-sale" (37.5% vs. 20.33% of the total cohort). Minimal differences were registered between the total cohort and all other FW groups regarding the frequency of food-on-sale buying.

The European Food Information Council (EUFIC) proposed a series of tools to prevent or diminish FW, consisting of planning meals, knowing food preservation, understanding 'use by' vs. 'best before' dates, using the available foods, avoiding serving too much; sharing extra food with others; repurpose waste where possible [

27]. Respecting food involves knowing the process that goes into making it. Food production knowledge is a way back to the farmers and their hard work. Food waste means wasting the labor, effort, investment, and resources (water, seeds, feed, etc.) consumed for producing it, as well as the resources for transporting and processing it [

28].

Home cooking wastes less food and uses less energy; the environmental impact is minimal when homemade food is mainly based on vegetables. National Resources Defense Council's report "Wasted" [

29] reveals that restaurants produce around 2-4 times the waste of food stores, retail supercenters, and wholesale distributors combined; only 2 percent of the food discarded is donated. People who cook more meals at home, avoid eating out, have healthier diets with more plant-based and other sustainable food, are less overweight, and spend less money on food overall [

30]. When farmers and local producers are the principal food sources, home cooking could become sustainable - preparing a meal and eating a dish ensure food waste diminution, suitable protection of the natural environment, and affordable prices [

31]. Thus, rural residents' considerably lower FW levels than urban residents could be explained.

FW interest and education are essential in reducing FW [

32]. Various courses are organized for interested people to investigate the causes of food loss and waste and evaluate their effects on the planet (food security, sustainability, and climate change) [

33]. Exploring the causes of food waste causes and suggesting solutions for FW diminution could help to improve the Romanian food system's sustainability [

34].

In the present study, 66.66% of the cohort was interested in FW associated with early measures to reduce FW or desire to know more about FW. In comparison, low and missing interest are more negligible (27.67%, 4.33%, and 1.33%). In the FW-0 and FW-1 groups, the components highlight a great interest in the FW process (62.5% and 25% vs.48.76% and 31.40%, respectively). FW interest significantly decreased in FW-2 and FW-3 (23.02% and 35.71% vs. 22.22% and 26.67% respectively). On the other hand, consumers expressed rather negative attitudes towards FW; they felt bad about wasting food and were concerned when they threw food away. As expected, negative emotions are associated with considerable intentions to diminish FW. Negative feelings lead to higher levels of food waste [

35]. Consumers are more concerned about the financial consequences of food waste and try to diminish it [

35]. Both aspects are evident in our study. FW guilty feelings increase directly proportional to FW frequency, from FW-0 to FW-3 (37.50% to 73.33%).

The perception of FW as a waste of money appears to be constructive, reducing the FW level. The financial level substantially varies with age; age influences food purchase, cooking behavior, and understanding and responsibility for FW.

Our study shows that the respondents from the urban zone have a great interest in FW, purchase foods daily or for several days, and opt for home cooking weekly, 2-3 times a week, and 2-3 times a month. Those from rural zones have a very high FW interest and prefer FP weekly. The respondents aged > 65 always prefer buying food on sale and rigorously respect the necessary food list, probably due to their small incomes. Families with children < 18 years old show various preferences for food on sale purchases. They motivate FW by stating that" "HMF amount is too much," "Grocery shopping is difficult," Food was forgotten," and "HMF leftovers use unknown."The [35-44] age category records the highest FW frequency, followed by [18-24]. Similar data were also reported by Dumitru et al. l [

25].

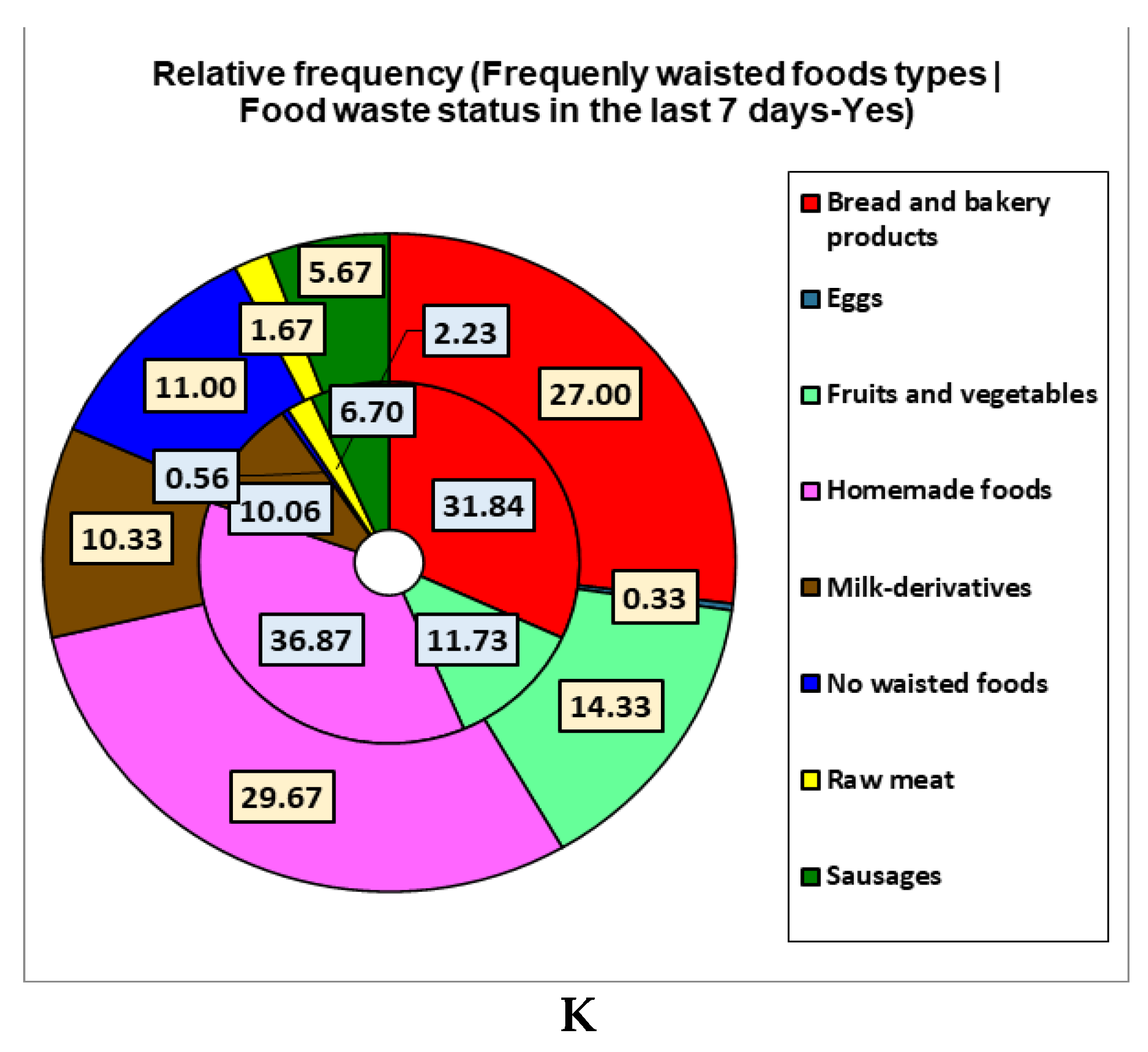

The results of the present study reveal a substantial FW level (FW-2 + FW-3 = 57%), while 4.5 million Romanian people live in poverty. The main reason for FW was" I forget the food, and it expires before eating" (59.66%), followed by the other 2 with similar relative frequencies (around 19%): "The amount of Homemade foods is too high for the needs of the household" and "The food has spoiled before the expiry date." Our results are similar to those of Dumitru et al. [

25].

Moreover, the participants evidenced 3 essential aspects that make difficult the FW diminution: "Grocery shopping is difficult" (46.33%), "I do not have enough space for food preservation" (22.66%), and "I don't know how to use leftovers" (20%). However, only 37.66% of respondents know about the Food Bank concept, and only 19.66% donate food to the Food Bank; they belong to the active workers group.

Considering all the aspects mentioned earlier, several civil society initiatives have been conducted in different regions of Romania to diminish household food waste [

35]. For example, community refrigerators for donated non-perishable food were placed in various zones of Bucharest; they are checked every hour by a General Directorate of Social Assistance guard [

26]. For around 15 years, the Vasiliada Association has been running the "Meal of Joy" project in 2 Romanian counties by partnering with the most known food companies [

36]. This association collects commercially non-available food that is 100% safe for consumption and distributes it to needy people [

26]. In other cities, social store associations collect food products from households and various companies with their own cars equipped with refrigeration systems and sell them to poor beneficiaries at very low prices [

26]. Romanian Food Banks Federation has 9 regional food banks and feeds the people in need with safe food products from over-stocks, mislabeling, and marketing campaigns. Currently, Romanian Food Banks collaborate with 121 donor companies, and since 2016, almost 18.00 tons of food have been distributed to around 225.000 persons [

37].

On the other hand, the awareness campaigns combat FW behavior in Romanian customers [

38]. The Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (MADR) is involved in various projects to educate consumers regarding food loss and waste (awareness-raising campaigns, school activities, seminars and training, and events). Currently, the MADR collaborates with the Ministry of Education for an informal campaign called 'You can also protect the planet! Together, we start reducing food waste, aiming to inform scholars about food waste's economic, social and environmental impacts[

39].

The present study has several limitations. The most significant is that the study database consists of self-reported information on household food waste collected as survey responses. Thus, the sample is not representative of the Romanian population because the selection was probabilistic as subjects wanted to fill in an online form. A few inadvertences were remarked in the no FW group, revealing discrepancies between self-reported data in FW frequency appreciation and detailed food waste investigation. The PCA correlation and heat maps support the mentioned observations. These aspects confirm the relativeness of FW-level analysis based on online questionnaires.

Another limitation is the cohort's medium size and relative uniformity – due to the limited number and diversity of the individuals who were announced and consequently accessed and completed the online questionnaire. Additionally, some respondent categories are minimally represented: males, people with rural residence, and old age.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization. E.M. and V.P.; methodology. E.M. and V.P.; software. E.M. and V.P.; validation. E.M.; formal analysis. V.P.; investigation. A.D., A.R., E.I.I., M.L., and V.M.M.; resources. O.K., D.L., E.A.O., and I.A.P.; data curation. A.D., A.R., E.I.I., M.L., and V.M.M.; writing—original draft preparation. E.M. and V.P.; writing—review and editing. E.M., A.D., V.P., A.R., E.I.I., M.L., O.K., D.L., E.A.O., V.M.M. and I.A.P.; visualization. E.M., A.D., V.P., A.R., E.I.I., M.L., O.K., D.L., E.A.O., V.M.M. and I.A.P.; supervision. E.M., D.L., and E.A.O.; project administration. E.M., D.L., and E.A.O.; funding acquisition. O.K., D.L., E.A.O., and I.A.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

(A) Study levels and the age of participants. (B-G) Socio-demographic factors and FW frequency: (B) Age (C) Study level (D) Sex; (E) Rezidence zone (rural and urban); (F) Family members number; (G) Children < 18 years.

Figure 1.

(A) Study levels and the age of participants. (B-G) Socio-demographic factors and FW frequency: (B) Age (C) Study level (D) Sex; (E) Rezidence zone (rural and urban); (F) Family members number; (G) Children < 18 years.

Figure 2.

(A) Kruskal-Wallis analysis for FW-0, FW-1, FW-2, and FW-3 comparison considers general data of respondents. Bonferroni corrected significance level = 0.0083. (B) Correlation between age groups (18-24, 25-34, 35-44, 45-54, 55-64, ≥65) gender (male (M)/female (F)), education level (high school, residence, number of household members (H1—H≥5), the presence of children (minors < 18 years, M-yes/M-no), residence (rural/urban) and the FW-level (FW0—FW3).

Figure 2.

(A) Kruskal-Wallis analysis for FW-0, FW-1, FW-2, and FW-3 comparison considers general data of respondents. Bonferroni corrected significance level = 0.0083. (B) Correlation between age groups (18-24, 25-34, 35-44, 45-54, 55-64, ≥65) gender (male (M)/female (F)), education level (high school, residence, number of household members (H1—H≥5), the presence of children (minors < 18 years, M-yes/M-no), residence (rural/urban) and the FW-level (FW0—FW3).

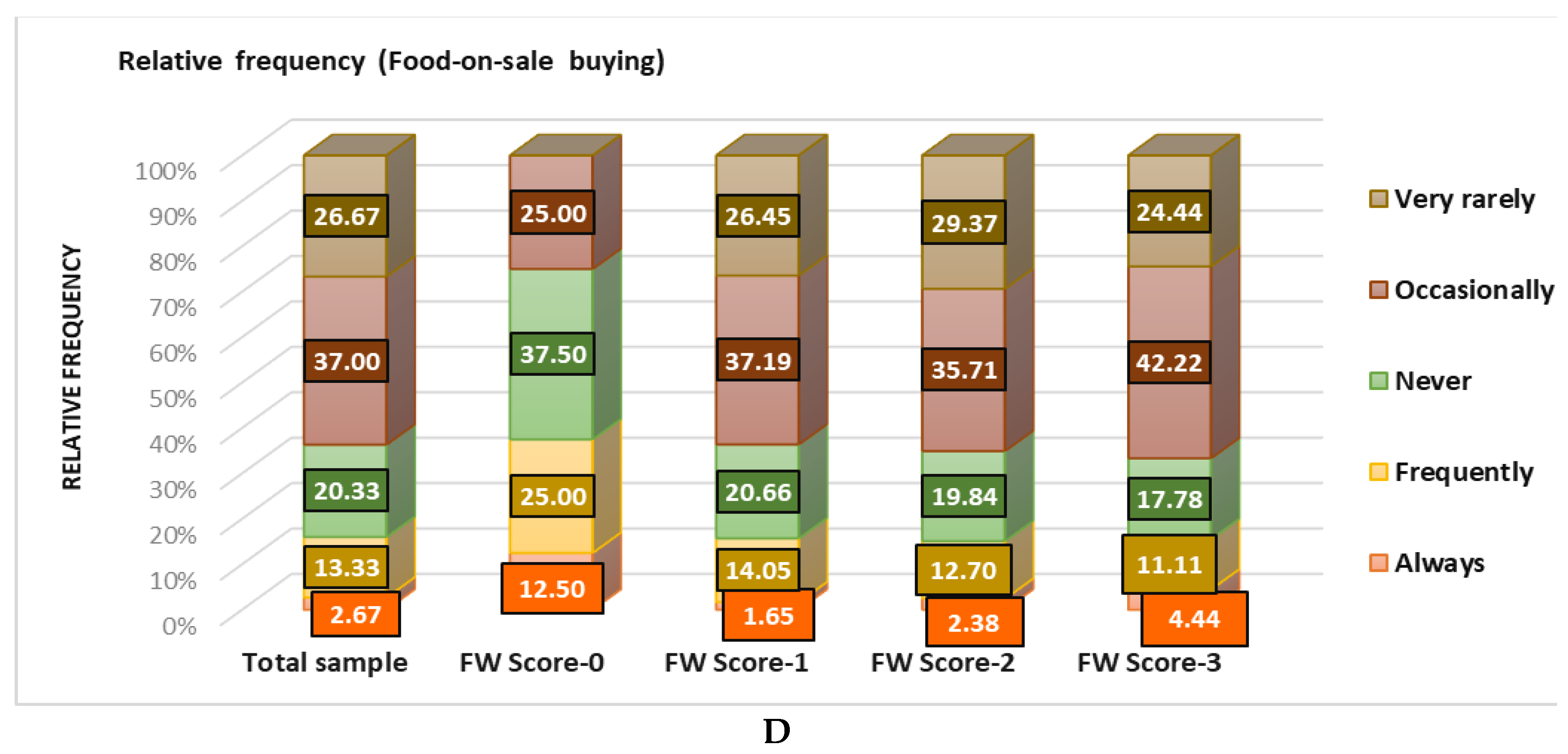

Figure 3.

FP behavior correspondence to FW score: (A) Involvement in food purchase; (B) Frequency of food purchase; (C) Food buying behavior; (D) Food-on-sale buying.

Figure 3.

FP behavior correspondence to FW score: (A) Involvement in food purchase; (B) Frequency of food purchase; (C) Food buying behavior; (D) Food-on-sale buying.

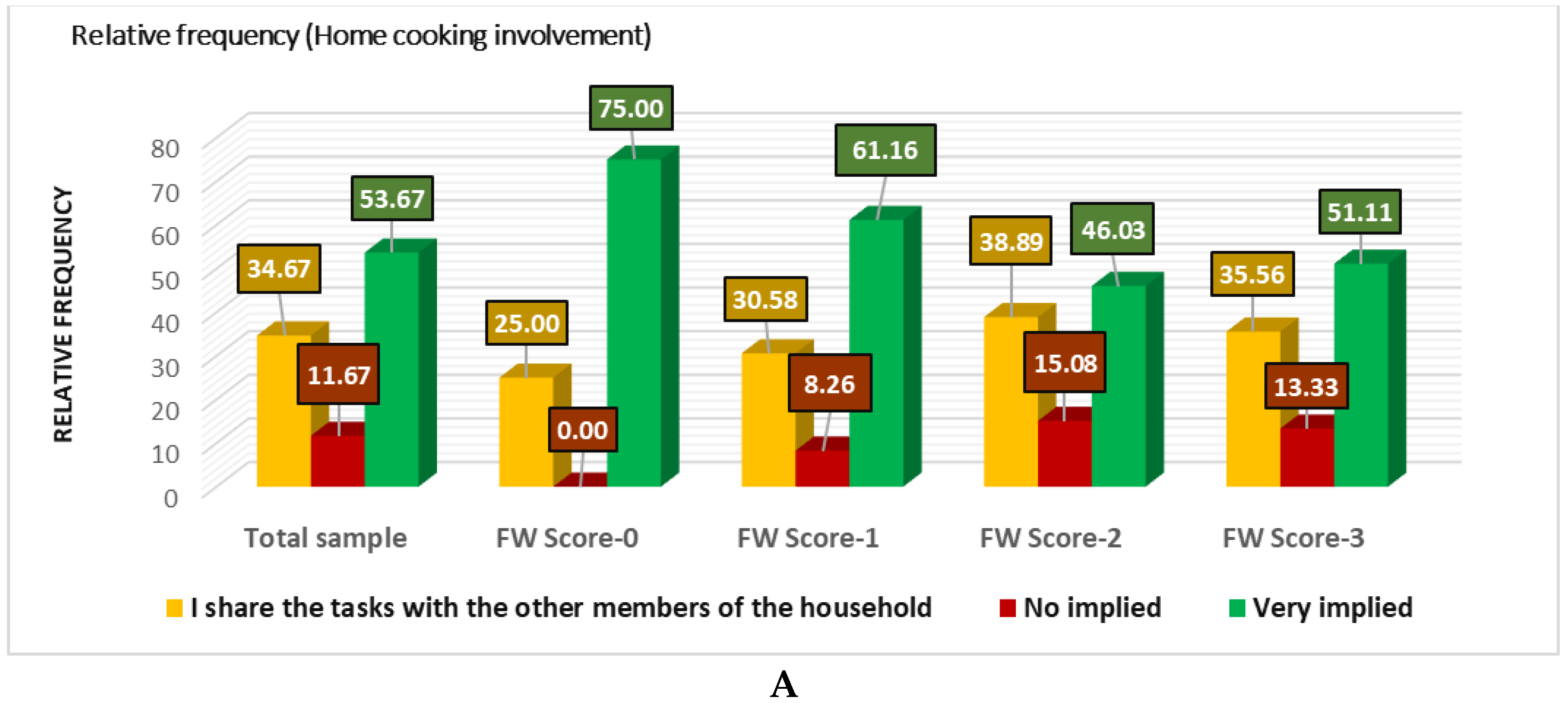

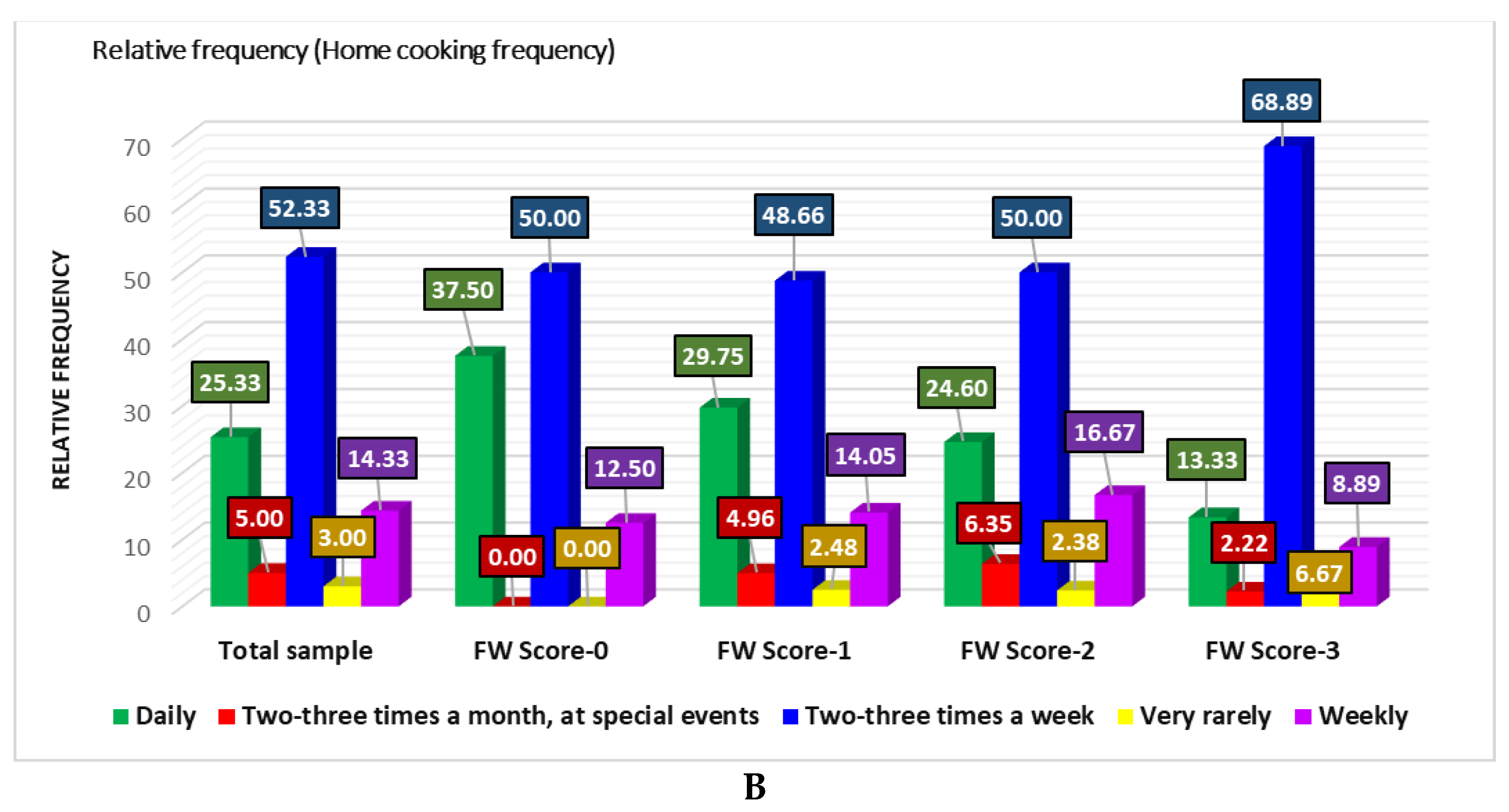

Figure 4.

HC behavior in concordance with FW frequency: (A) Home cooking involvement; (B) Home cooking frequency.

Figure 4.

HC behavior in concordance with FW frequency: (A) Home cooking involvement; (B) Home cooking frequency.

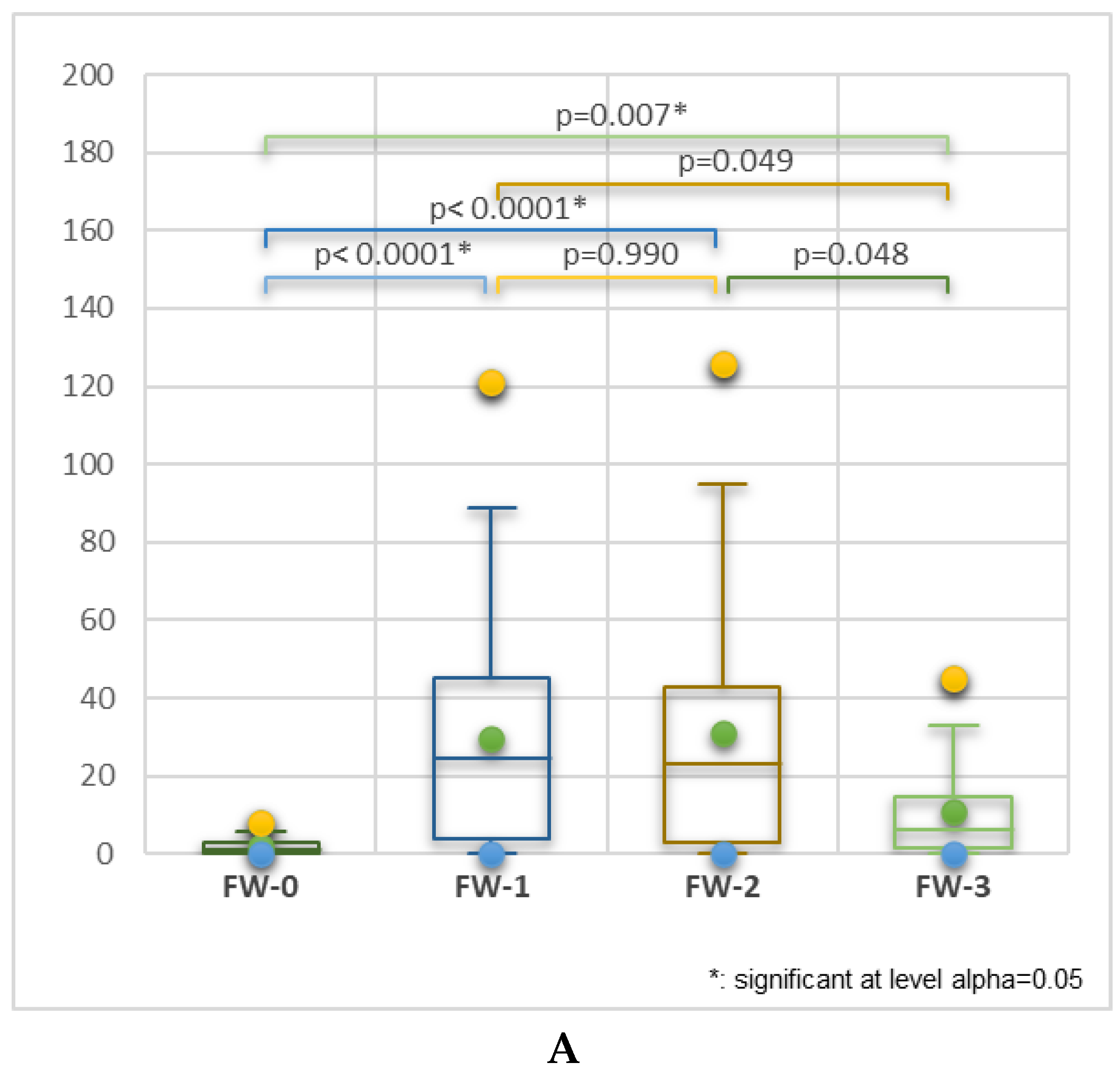

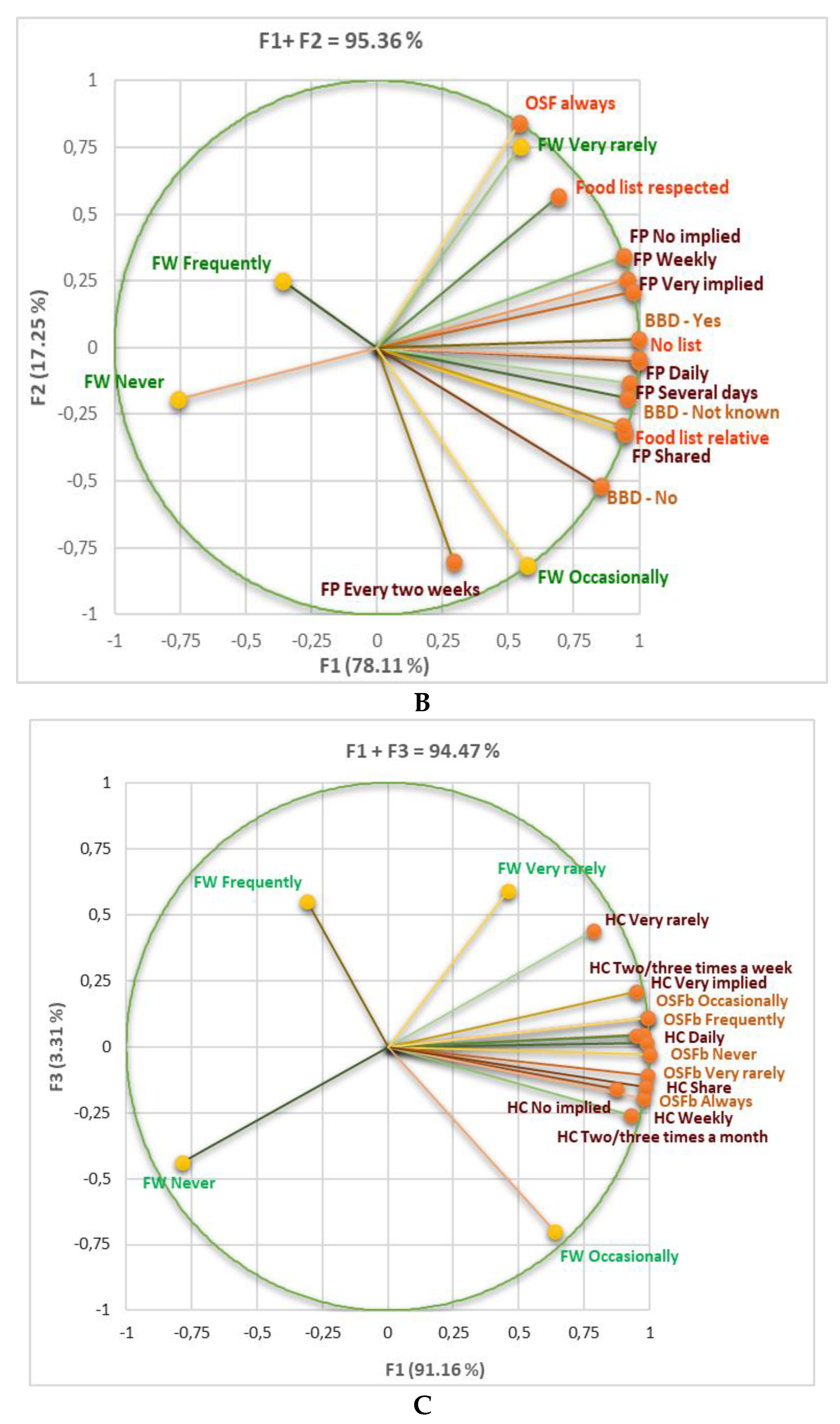

Figure 5.

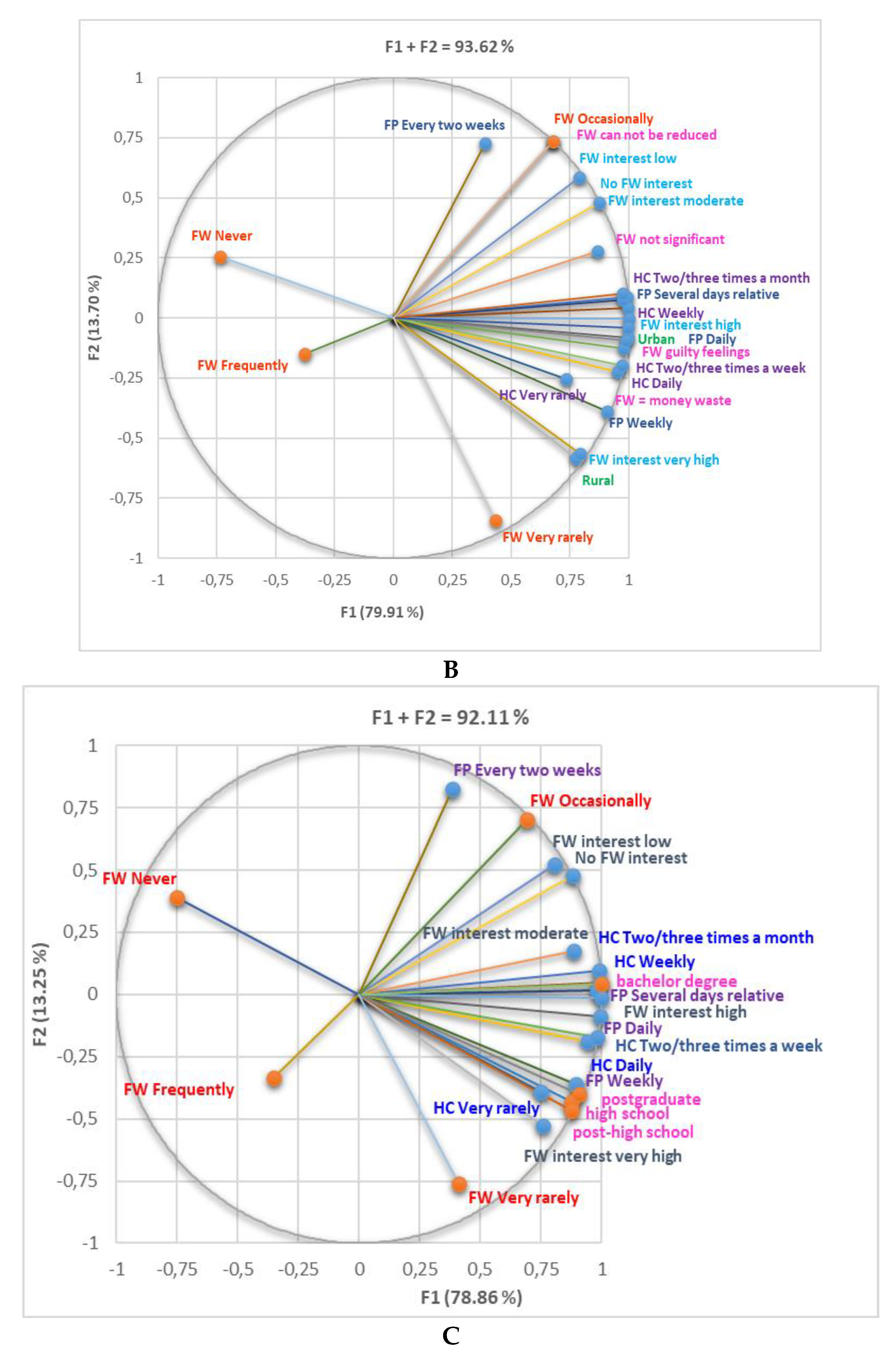

(A) Kruskal-Wallis's analysis for FW-0, FW-1, FW-2, and FW-3 comparison considers food buying and homemade food cooking behavior data. Bonferroni corrected significance level = 0.0083. (B) Correlation between FW-level (FW-0—FW-3) and food purchase (FP) aspects: involvement in FP, food-on-sale buying preference, FP frequency, food buying behavior, and BBD knowledge status; (C) Correlation between food cooking aspects: frequency, involvement, OSFb preference; FP = food purchase, FC = food cooking, BBD = best before date, OSF = food-on-sale (with a low BBD), OSFb = food on sale buying; HC = home cooking, FW = food waste.

Figure 5.

(A) Kruskal-Wallis's analysis for FW-0, FW-1, FW-2, and FW-3 comparison considers food buying and homemade food cooking behavior data. Bonferroni corrected significance level = 0.0083. (B) Correlation between FW-level (FW-0—FW-3) and food purchase (FP) aspects: involvement in FP, food-on-sale buying preference, FP frequency, food buying behavior, and BBD knowledge status; (C) Correlation between food cooking aspects: frequency, involvement, OSFb preference; FP = food purchase, FC = food cooking, BBD = best before date, OSF = food-on-sale (with a low BBD), OSFb = food on sale buying; HC = home cooking, FW = food waste.

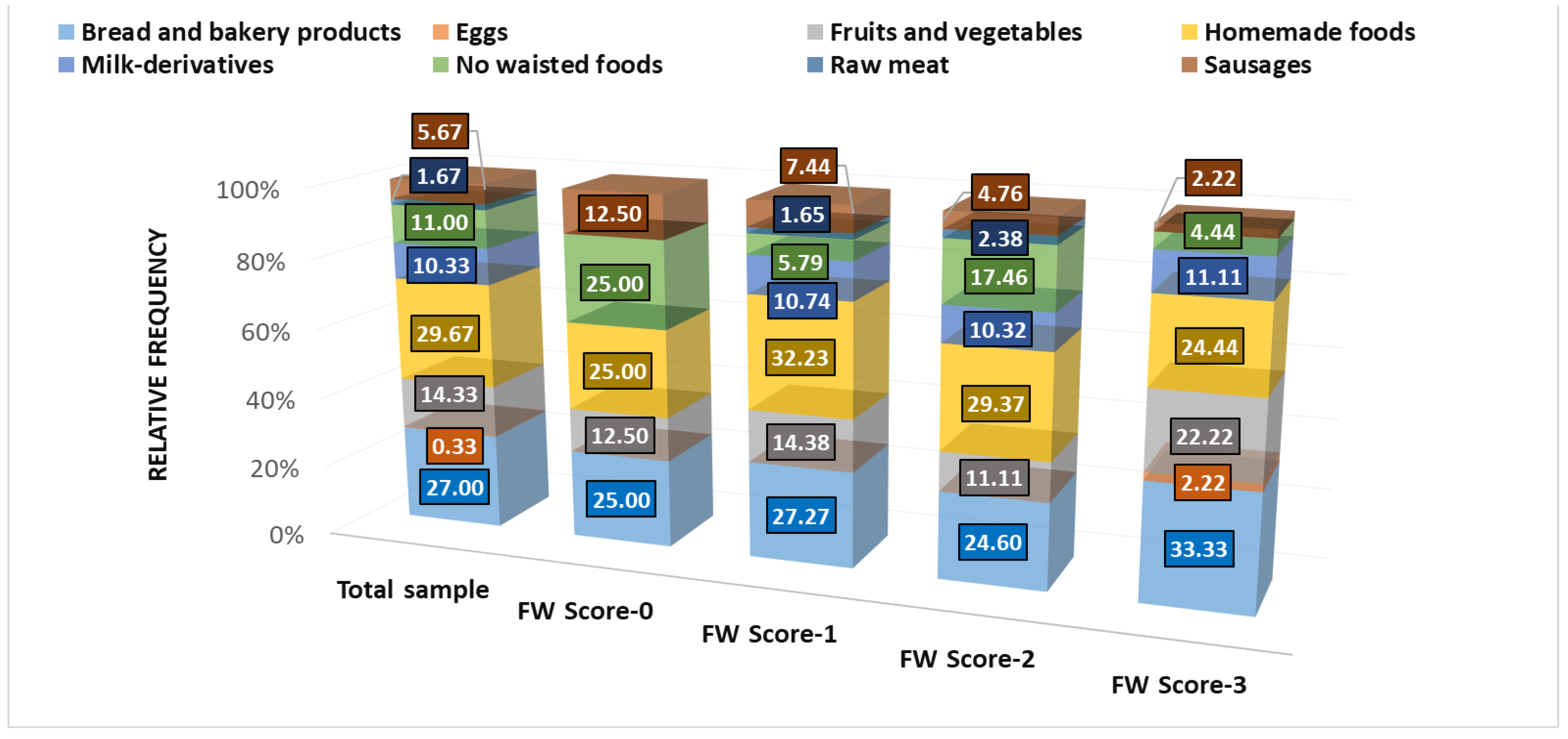

Figure 6.

The most frequently wasted foods.

Figure 6.

The most frequently wasted foods.

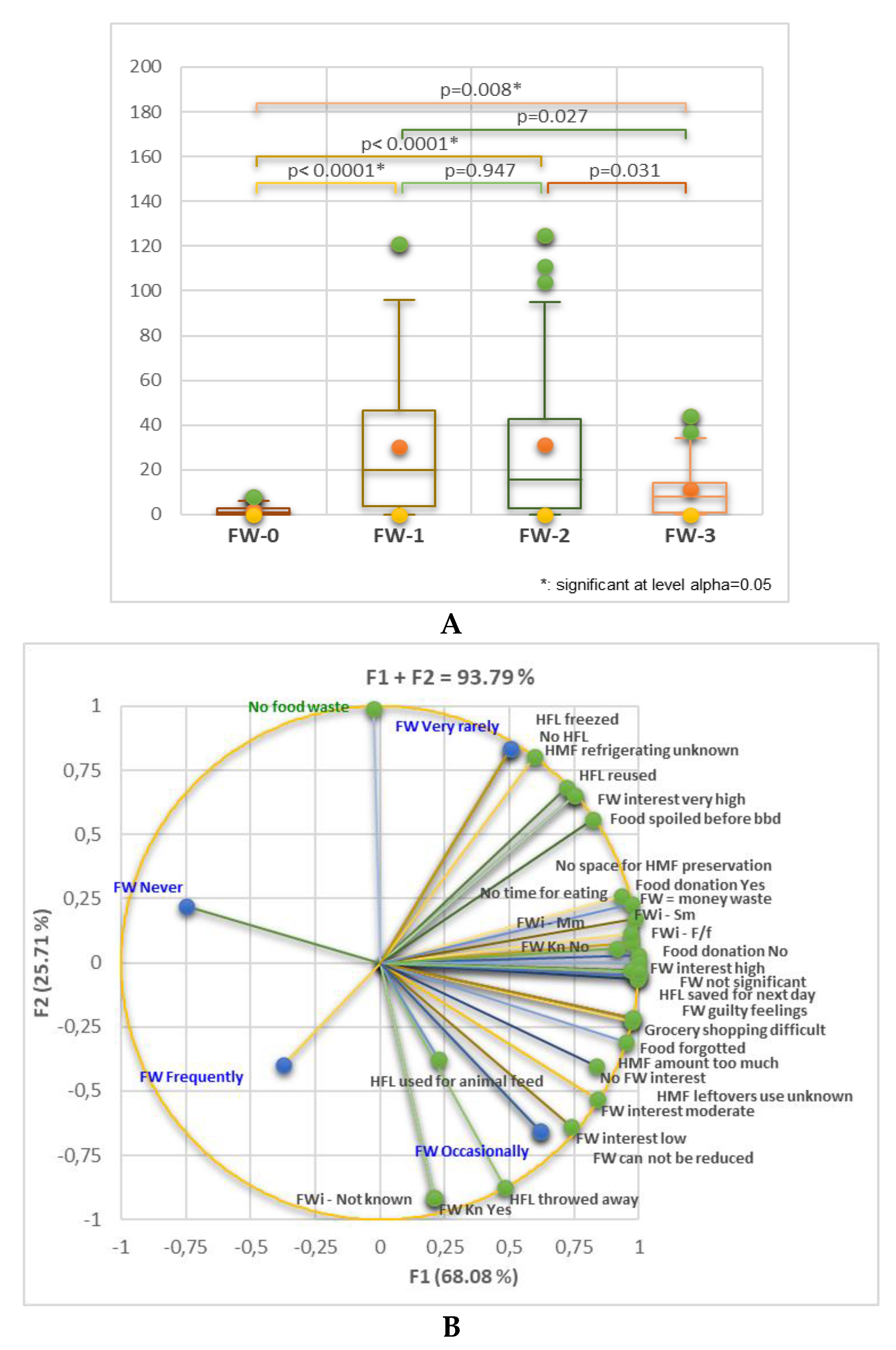

Figure 7.

(A) Kruskal-Wallis's analysis for FW-0, FW-1, FW-2, and FW-3 comparison considers all data related to FW, registered in

Table 1. Bonferroni corrected significance level = 0.0083.

(B) Correlation between FW-level (FW-0—FW-3) and the aspects involved in FW.

(C) Frequently wasted food is expressed as a relative frequency (%) in each FW group compared to the total cohort. FW = food waste; kn = knowledge; FWi = food waste information; F/f = family and friends; Mm = mass media; Sm = social media; HMF = homemade food; HFL = homemade food leftovers.

Figure 7.

(A) Kruskal-Wallis's analysis for FW-0, FW-1, FW-2, and FW-3 comparison considers all data related to FW, registered in

Table 1. Bonferroni corrected significance level = 0.0083.

(B) Correlation between FW-level (FW-0—FW-3) and the aspects involved in FW.

(C) Frequently wasted food is expressed as a relative frequency (%) in each FW group compared to the total cohort. FW = food waste; kn = knowledge; FWi = food waste information; F/f = family and friends; Mm = mass media; Sm = social media; HMF = homemade food; HFL = homemade food leftovers.

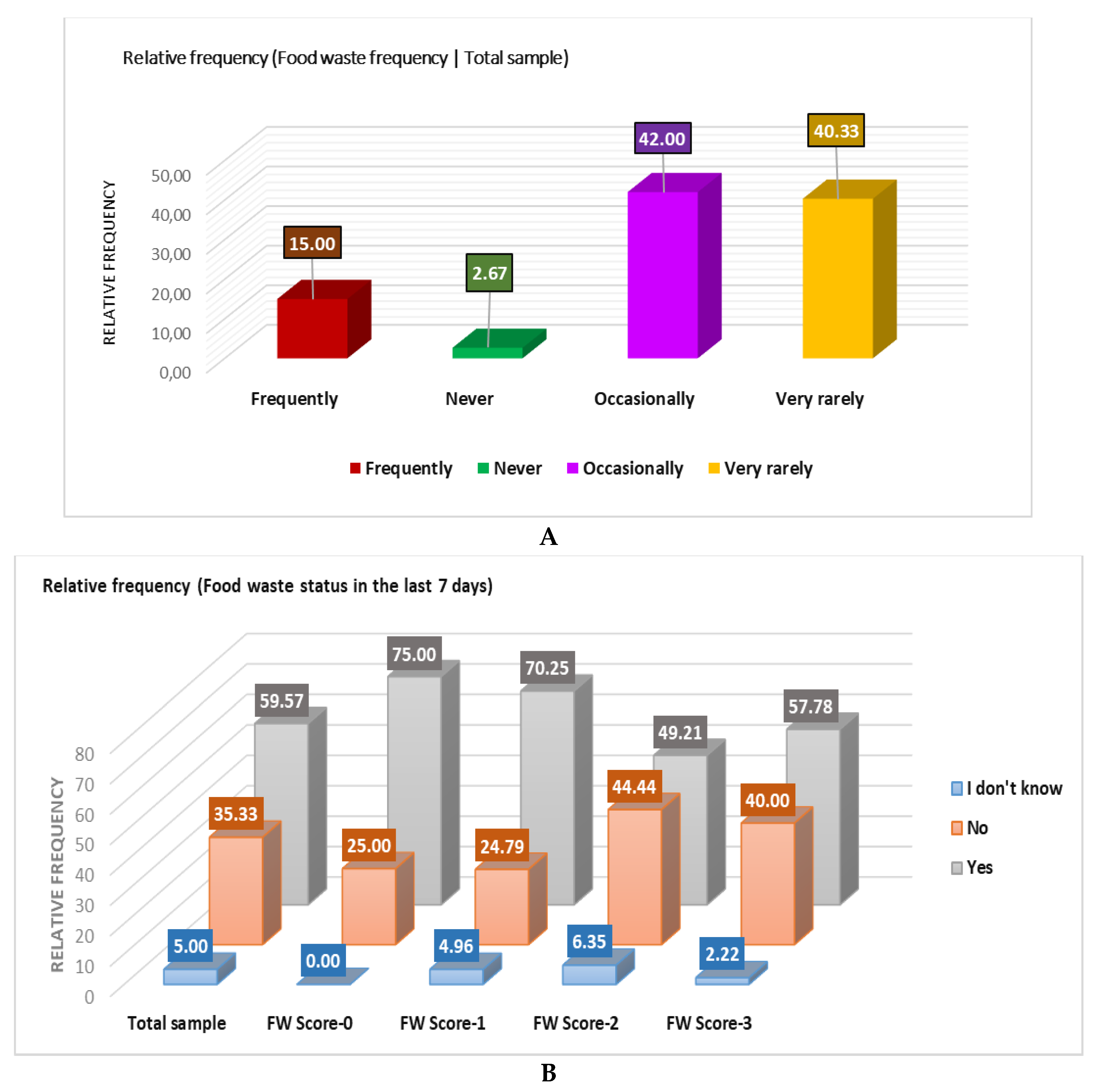

Figure 8.

The correspondence between FW score (A) and FW status in the last 7 days (B).

Figure 8.

The correspondence between FW score (A) and FW status in the last 7 days (B).

Figure 9.

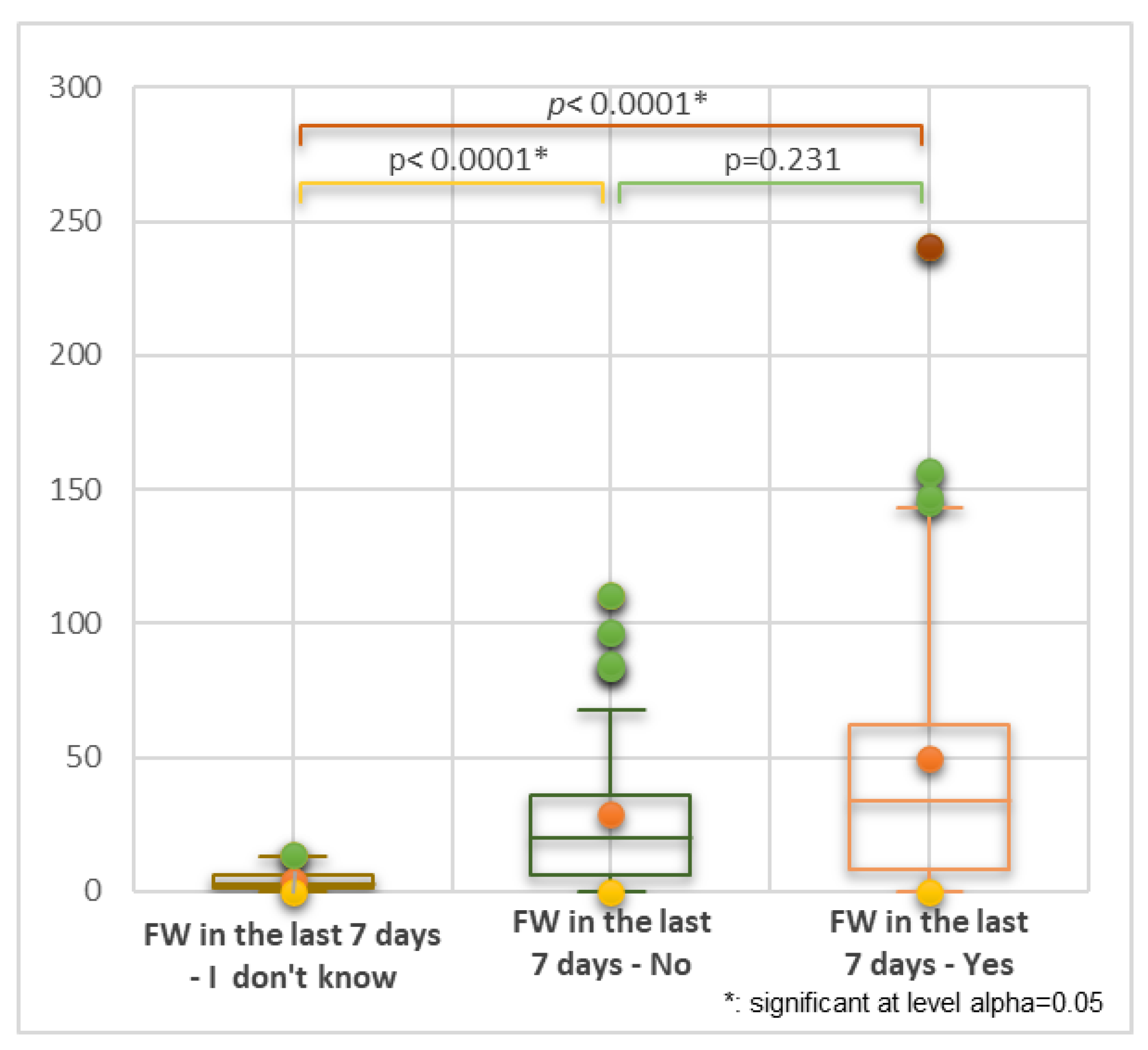

Kruskal-Wallis analysis of all three groups of FW status in the last 7 days. Bonferroni corrected significance level = 0.0167.

Figure 9.

Kruskal-Wallis analysis of all three groups of FW status in the last 7 days. Bonferroni corrected significance level = 0.0167.

Figure 10.

Food waste in the last 7 days' positive status (Yes) and related variable parameters (relative frequency%) compared with the total cohort. (A) FW-score; (B) Food waste term knowledge status; (C) Foodbank concept knowledge status; (D). Status of personal involvement in donating foods; (E) Status of understanding the difference between "to preferably be consumed before" and "to be consumed up to"; (F) Status of understanding the concept of "preferably consumed before"; (G) Food waste awareness status; (H). Status of FW personal interest; (I) The main reasons for food waste; (J) The reasons for making difficult food waste diminution; (K) Frequently wasted food types.

Figure 10.

Food waste in the last 7 days' positive status (Yes) and related variable parameters (relative frequency%) compared with the total cohort. (A) FW-score; (B) Food waste term knowledge status; (C) Foodbank concept knowledge status; (D). Status of personal involvement in donating foods; (E) Status of understanding the difference between "to preferably be consumed before" and "to be consumed up to"; (F) Status of understanding the concept of "preferably consumed before"; (G) Food waste awareness status; (H). Status of FW personal interest; (I) The main reasons for food waste; (J) The reasons for making difficult food waste diminution; (K) Frequently wasted food types.

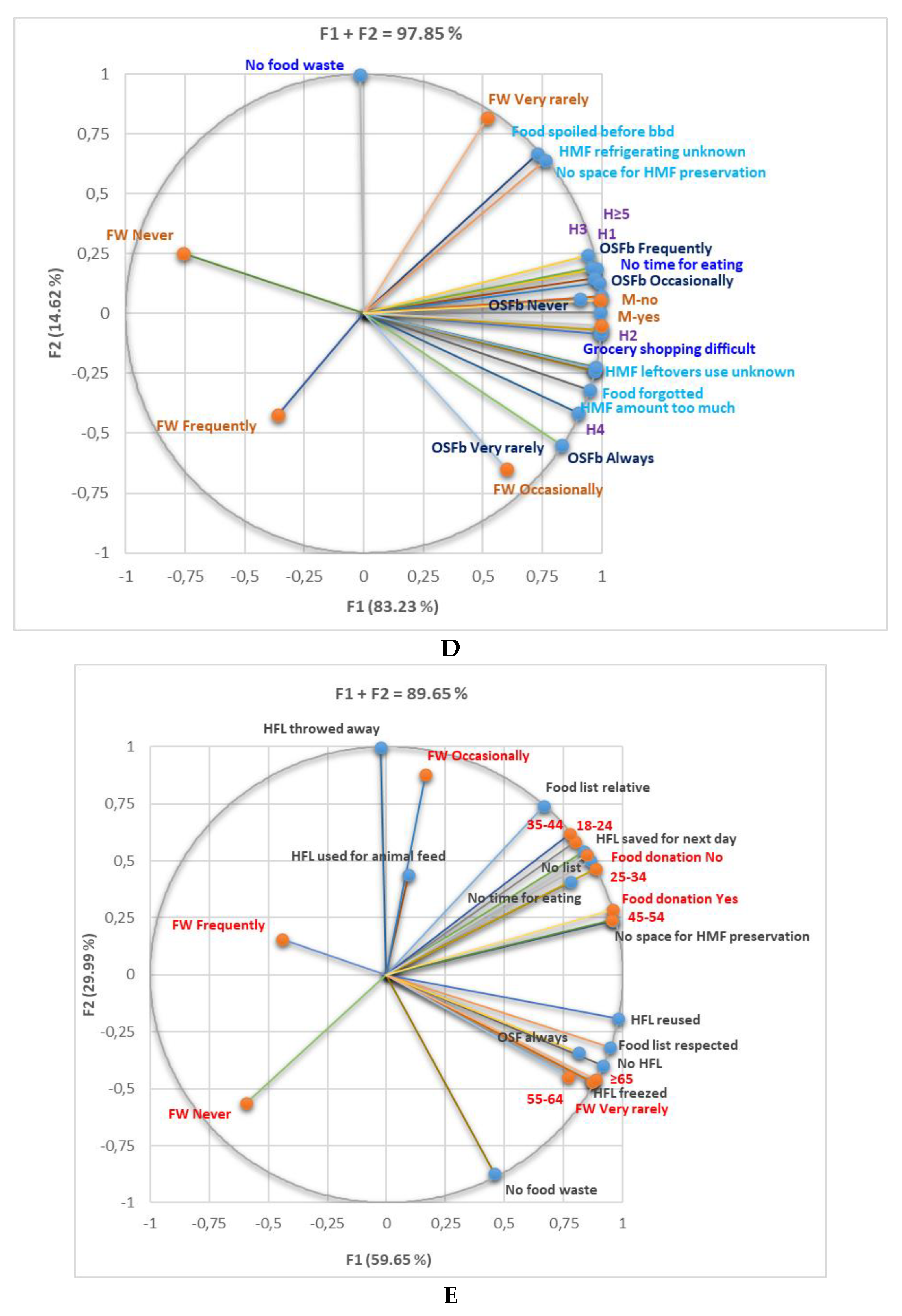

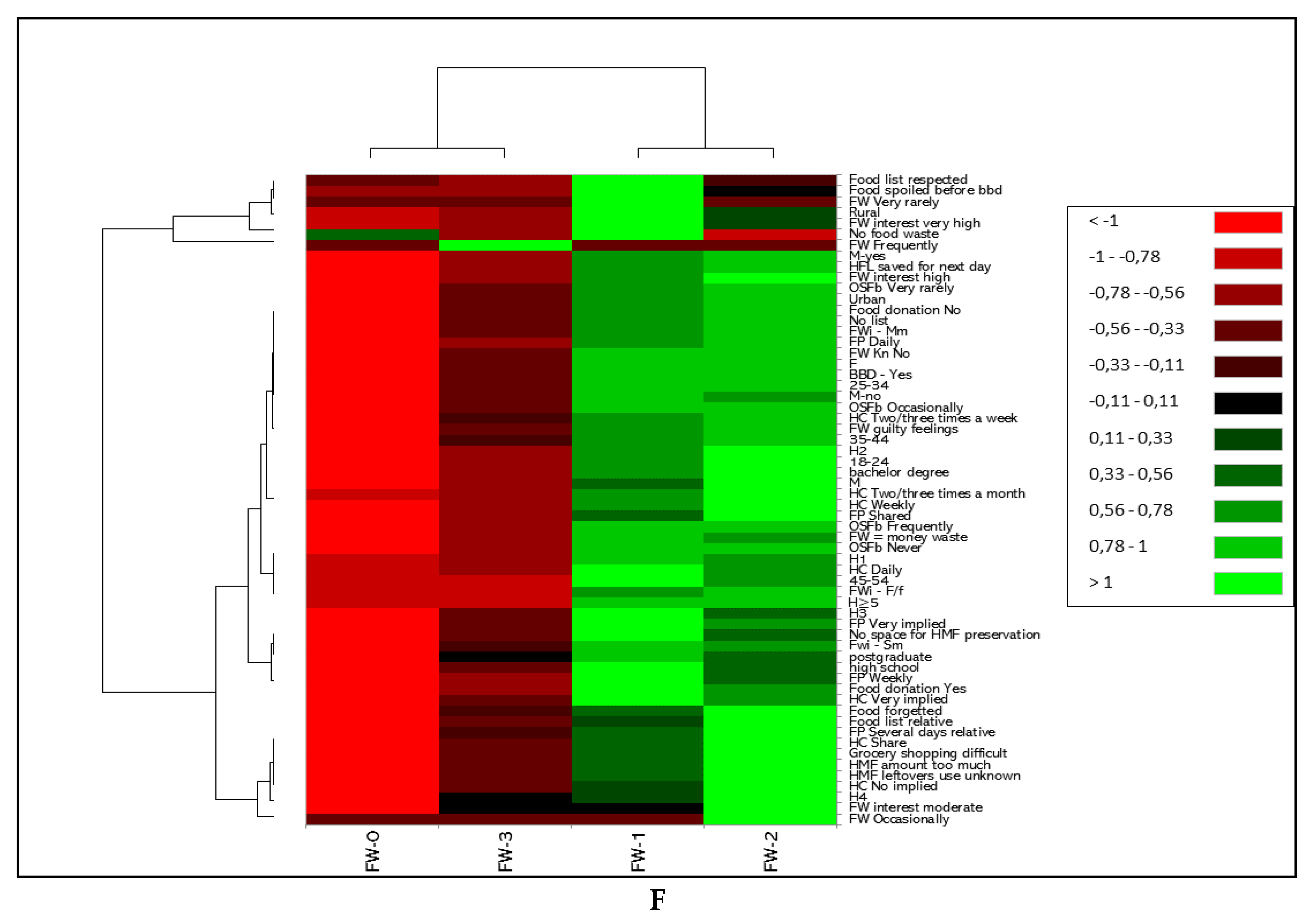

Figure 11.

(A) Kruskal-Wallis's FW-0, FW-1, FW-2, and FW-3 comparison considers all data (general and related to FP and FW) registered in Tables 1-3. Bonferroni corrected significance level = 0.0083. (B-E) Correlation between FW-level (FW-0—FW-3), general data, and the aspects involved in FP and FW. (F) Heat maps with significant differences between all FW-scored groups. FW = food waste; kn = knowledge; FWi = food waste information; F/f = family and friends, Mm = mass media; Sm = social media; HMF = homemade food; HFL = homemade food leftovers; H1-H4-H≥5 = the number of household members.

Figure 11.

(A) Kruskal-Wallis's FW-0, FW-1, FW-2, and FW-3 comparison considers all data (general and related to FP and FW) registered in Tables 1-3. Bonferroni corrected significance level = 0.0083. (B-E) Correlation between FW-level (FW-0—FW-3), general data, and the aspects involved in FP and FW. (F) Heat maps with significant differences between all FW-scored groups. FW = food waste; kn = knowledge; FWi = food waste information; F/f = family and friends, Mm = mass media; Sm = social media; HMF = homemade food; HFL = homemade food leftovers; H1-H4-H≥5 = the number of household members.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of all 300 respondents and FW-scores.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of all 300 respondents and FW-scores.

| Parameter |

Category |

T |

F |

M |

p-value |

| Frequency / Relative frequency |

N |

% |

N |

% |

N |

% |

T/F |

F/M |

T/M |

| Age (years) |

Total |

300.00 |

100.00 |

245.00 |

81.67 |

55.00 |

18.33 |

0.68 |

0.04* |

0.04* |

| 18-24 |

98.00 |

32.67 |

82.00 |

33.47 |

16.00 |

29.09 |

| 25-34 |

33.00 |

11.00 |

28.00 |

11.43 |

5.00 |

9.09 |

| 35-44 |

103.00 |

34.33 |

80.00 |

32.65 |

23.00 |

41.82 |

| 45-54 |

47.00 |

15.67 |

40.00 |

16.33 |

7.00 |

12.73 |

| 55-64 |

12.00 |

4.00 |

9.00 |

3.67 |

3.00 |

5.45 |

| ≥65 |

7.00 |

2.33 |

6.00 |

2.45 |

1.00 |

1.82 |

| Study level |

Bachelor's degree |

172.00 |

57.33 |

140.00 |

57.14 |

32.00 |

58.18 |

0.77 |

0.16 |

0.14 |

| High school |

36.00 |

12.00 |

28.00 |

11.43 |

8.00 |

14.55 |

| Post-high school |

10.00 |

3.33 |

9.00 |

3.67 |

1.00 |

1.82 |

| Postgraduate |

82.00 |

27.33 |

68.00 |

27.76 |

14.00 |

25.45 |

| Residence |

Rural |

34.00 |

11.33 |

27.00 |

11.02 |

7.00 |

12.73 |

0.87 |

0.43 |

0.40 |

| Urban |

266.00 |

88.67 |

218.00 |

88.98 |

48.00 |

87.27 |

| Family membersnumber |

1 |

46.00 |

15.33 |

33.00 |

13.47 |

13.00 |

23.64 |

0.53 |

0.01* |

0.01* |

| 2 |

93.00 |

31.00 |

79.00 |

32.24 |

14.00 |

25.45 |

| 3 |

85.00 |

28.33 |

68.00 |

27.76 |

17.00 |

30.91 |

| 4 |

54.00 |

18.00 |

46.00 |

18.78 |

8.00 |

14.55 |

| ≥5 |

22.00 |

7.33 |

19.00 |

7.76 |

3.00 |

5.45 |

| Children < 18 years |

No |

134.00 |

44.67 |

109.00 |

44.49 |

25.00 |

45.45 |

0.31 |

0.02* |

0.02* |

| Yes |

166.00 |

55.33 |

136.00 |

55.51 |

30.00 |

54.55 |

| FW Score |

FW-0 |

8.00 |

2.67 |

7.00 |

2.86 |

1.00 |

1.82 |

0.72 |

0.09 |

0.08 |

| FW-1 |

121.00 |

40.33 |

101.00 |

41.22 |

20.00 |

36.36 |

| FW-2 |

126.00 |

42.00 |

99.00 |

40.41 |

27.00 |

49.09 |

| FW-3 |

45.00 |

15.00 |

38.00 |

15.51 |

7.00 |

12.73 |