Submitted:

27 October 2025

Posted:

28 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Viability Using Flow Cytometry (FACS)

2.2. Knockdown by siRNAs

2.3. Overexpression of DJ-1

2.4. Western Blot

2.5. Reverse Transcription PCR (RT-PCR) and PCR

2.6. RNA-Seq

2.7. Bioinformatic Analysis

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

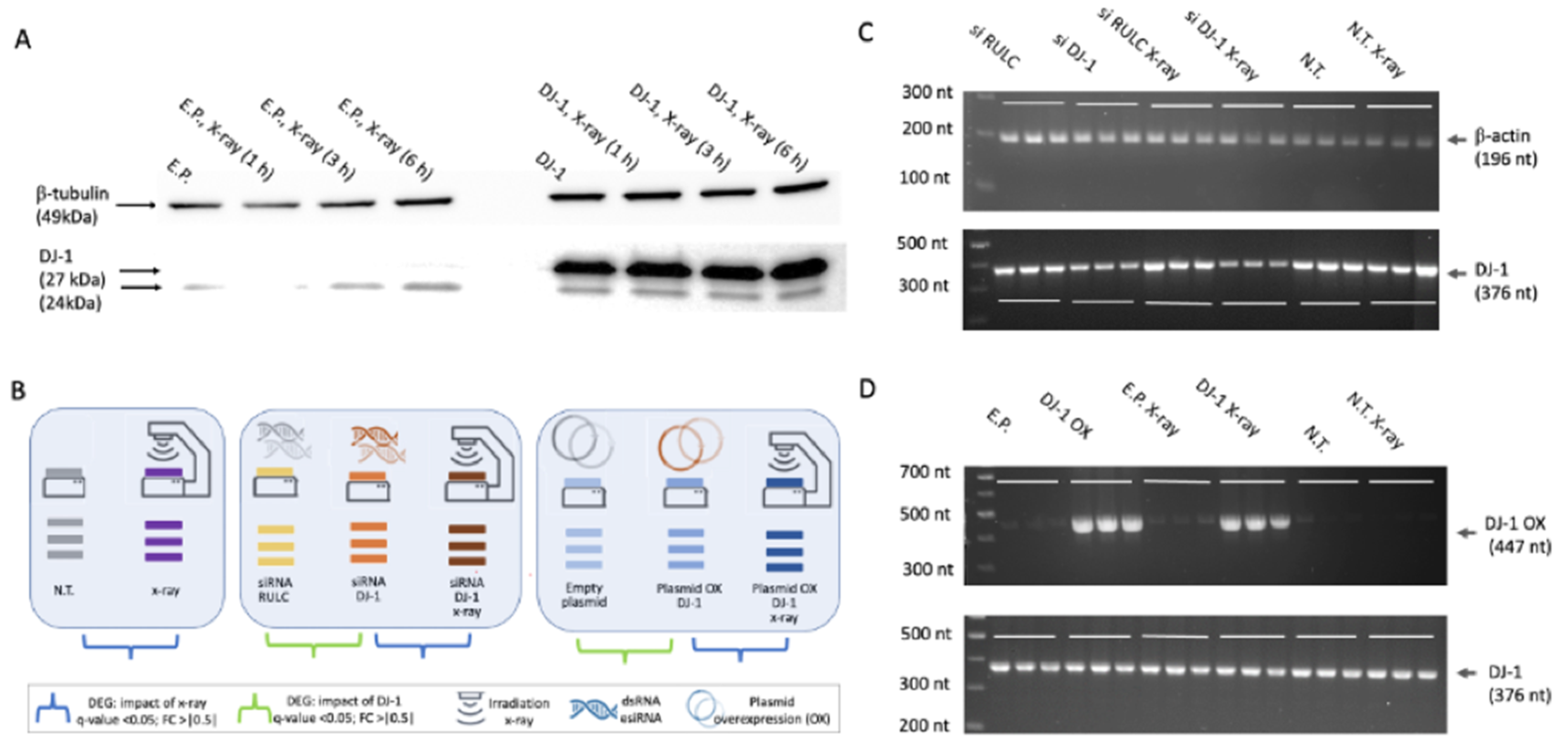

3.1. DNA Damage Response by X-Ray Irradiation

3.2. Testing the Impact of X-Ray Irradiation in Cells Ranges by Different Levels of DJ-1

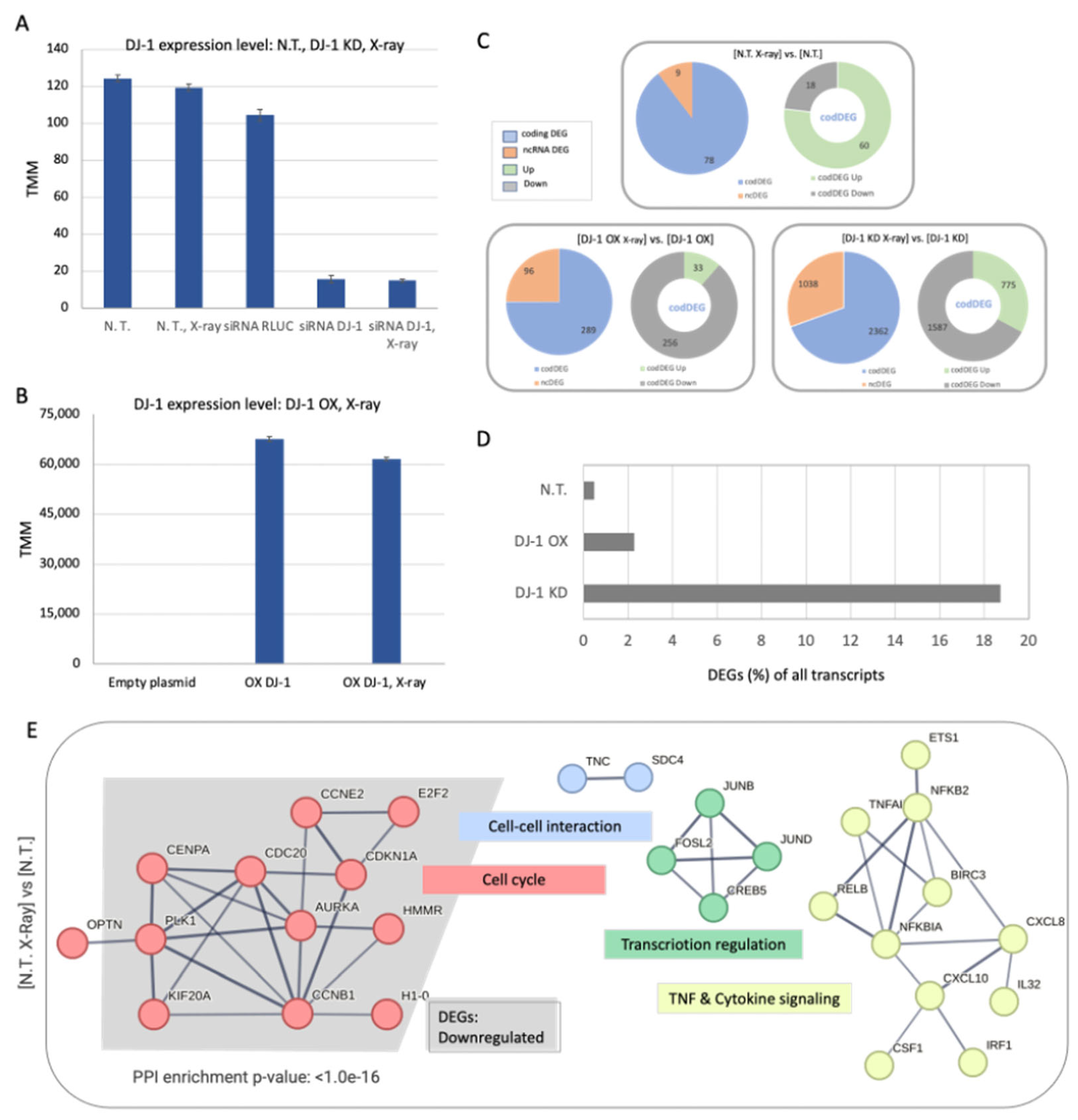

3.3. Global Statistics of Transcriptomes of Cells Exposed to X-Ray

3.4. Naïve Cells Display a Limited but Coordinated Response to X-Ray Irradiation

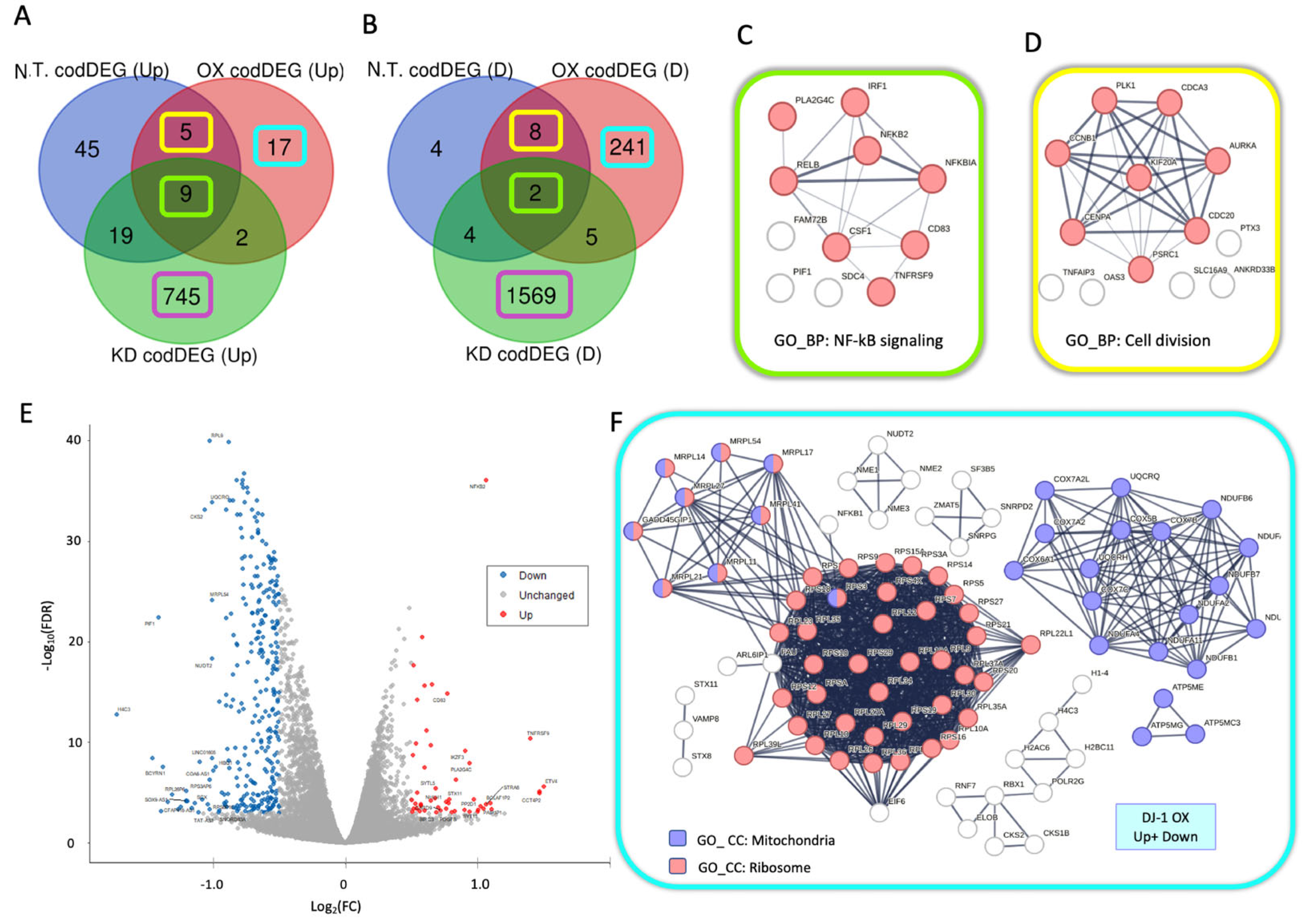

3.5. Downregulation in Ribosomal and Mitochondrial Transcripts Dominates DJ-1 Overexpression

3.6. Induction of ncRNAs in Response to X-Ray Irradiation

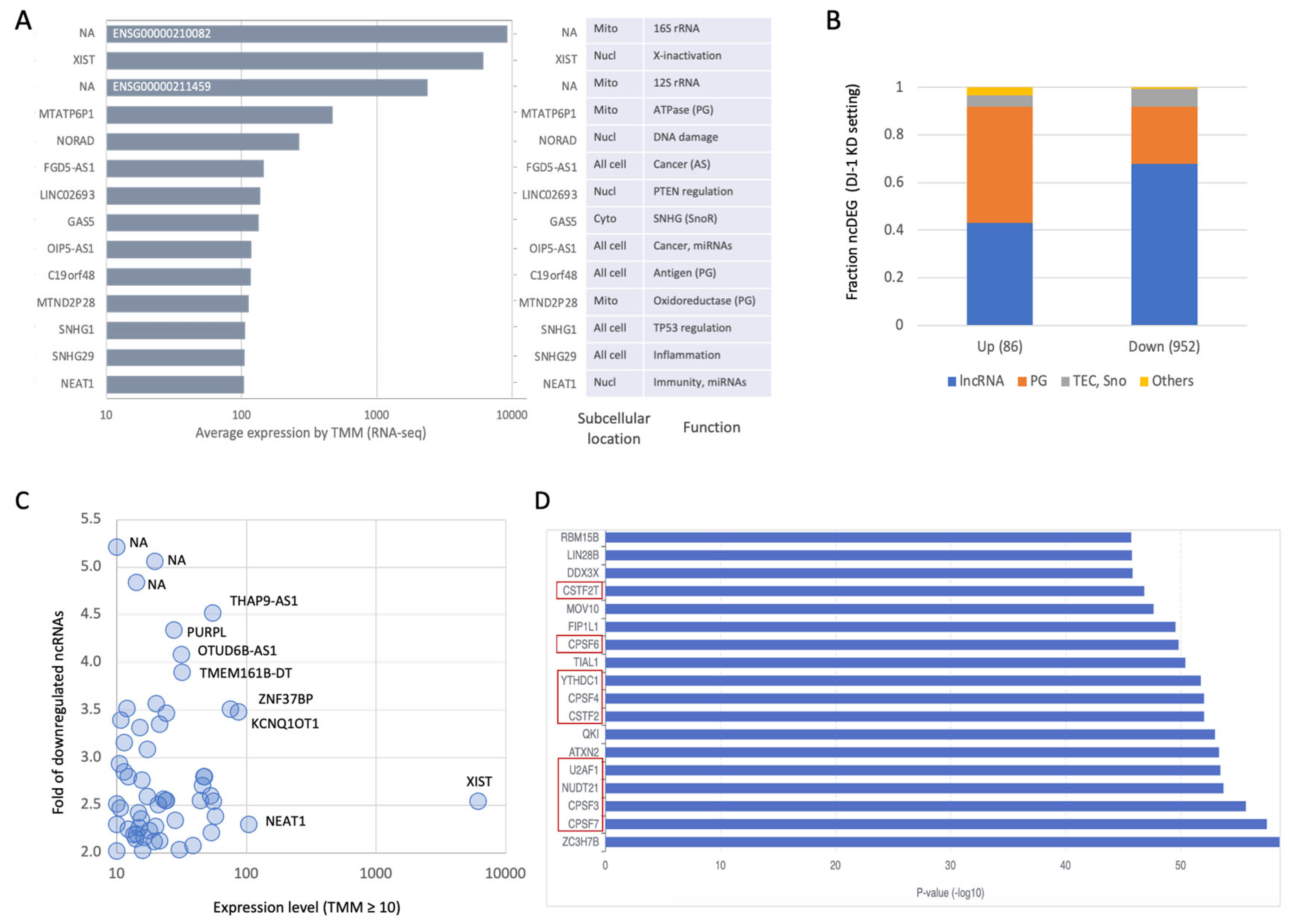

3.7. X-Ray Irradiation on siRNA DJ-1 KD Resulted in a Global Dysregulation of ncRNA Transcription

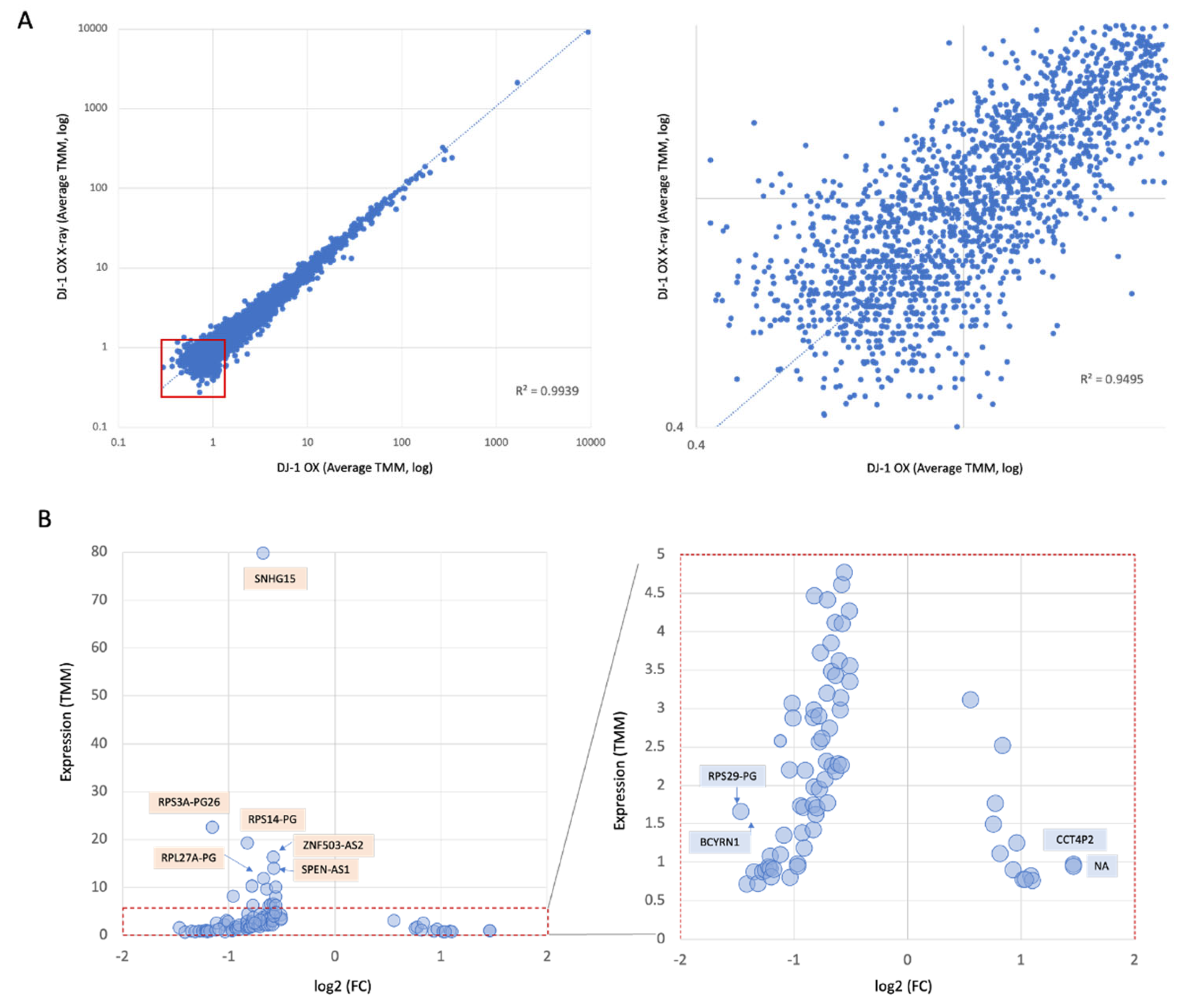

3.8. A Tight Control on ncRNA Transcription Landscape Following X-Ray Irradiation in DJ-1 OX Cells

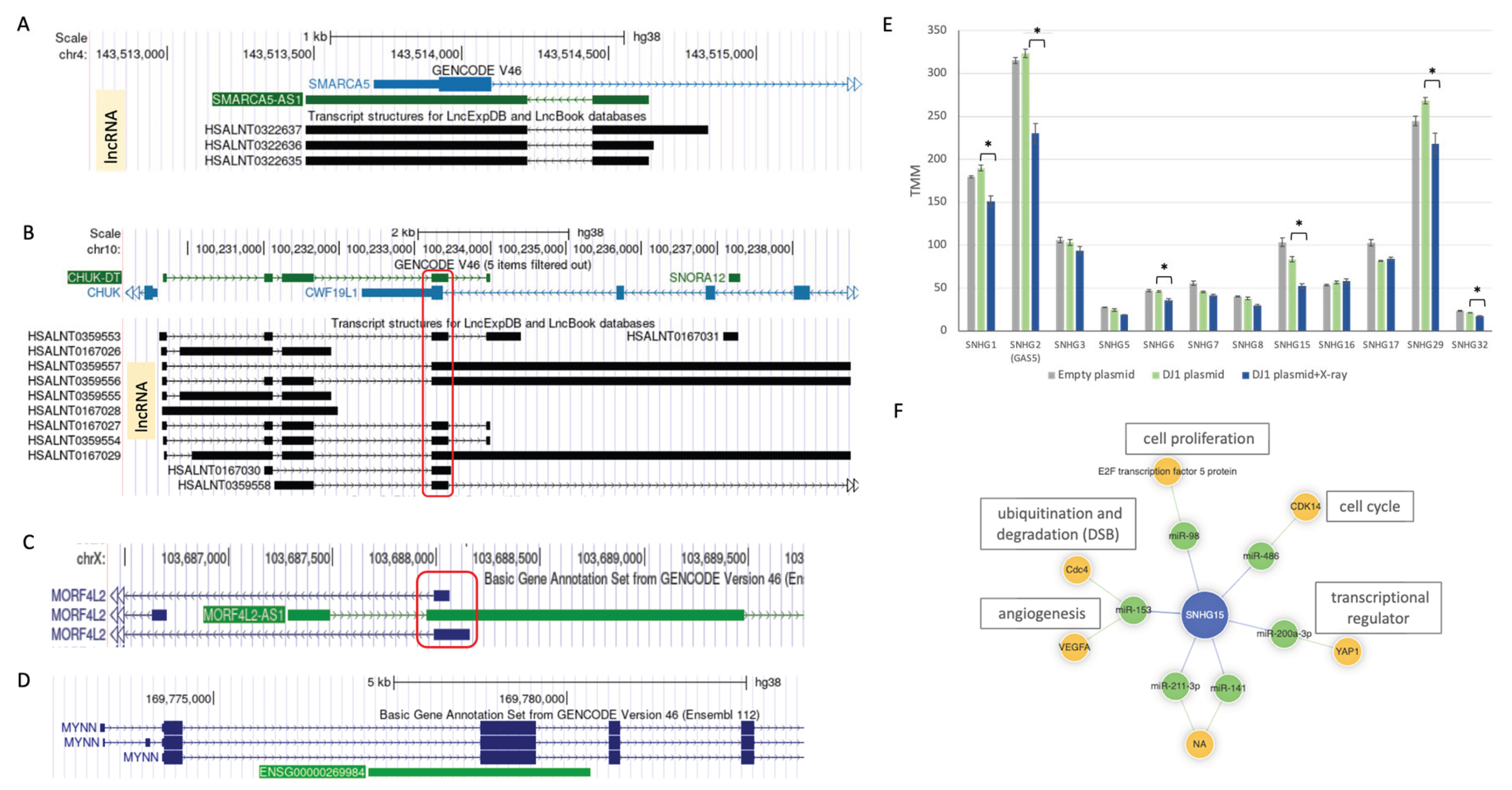

3.9. Potential Functions of ncRNAs as Antisense in Response to X-Ray Irradiation

3.10. Suppression of SNHG Family Members Following X-Ray Irradiation in DJ-1 OX Cells

3.11. Cells with Overexpressed or Depleted DJ-1 Resulted in an Inverse Expression Trend

3.12. Enrichment of Cell Cycle Arrest and Chromatin Functional Classes Under Varying DJ-1 Expression Levels

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AGO2 | Argonaute 2 |

| DDR | DNA damage response |

| DEG | differentially expressed genes |

| DSB | double-strand break |

| HR | homologous recombination |

| KD | knockdown |

| N.T. | not treated |

| ncRNA | non-coding RNA |

| NHEJ | non-homologous end joining |

| Nt | nucleotides |

| OX | overexpression |

| PCA | principal component analysis |

| PD | Parkinson's disease |

| protein-protein interaction (PPI) | |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| TF | transcription factor |

| TMM | trimmed mean of the M-values normalization |

References

- Biosa, A.; Sandrelli, F.; Beltramini, M.; Greggio, E.; Bubacco, L.; Bisaglia, M. Recent findings on the physiological function of DJ-1: Beyond Parkinson's disease. Neurobiology of disease 2017, 108, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riepe, C.; Zelin, E.; Frankino, P.A.; Meacham, Z.A.; Fernandez, S.G.; Ingolia, N.T.; Corn, J.E. Double stranded DNA breaks and genome editing trigger loss of ribosomal protein RPS27A. FEBS J 2022, 289, 3101–3114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Yang, B.; He, Q.; Weng, Q. Role of DJ-1 in immune and inflammatory diseases. Frontiers in immunology 2020, 11, 529121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ariga, H.; Takahashi-Niki, K.; Kato, I.; Maita, H.; Niki, T.; Iguchi-Ariga, S.M. Neuroprotective function of DJ-1 in Parkinson's disease. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2013, 2013, 683920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolgacheva, L.P.; Berezhnov, A.V.; Fedotova, E.I.; Zinchenko, V.P.; Abramov, A.Y. Role of DJ-1 in the mechanism of pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease. Journal of Bioenergetics and Biomembranes 2019, 51, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahle, P.J.; Waak, J.; Gasser, T. DJ-1 and prevention of oxidative stress in Parkinson's disease and other age-related disorders. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2009, 47, 1354–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inberg, A.; Linial, M. Protection of pancreatic β-cells from various stress conditions is mediated by DJ-1. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2010, 285, 25686–25698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.-M.; Jang, H.-J.; Choi, S.Y.; Park, S.-A.; Kim, I.S.; Yang, Y.R.; Lee, Y.H.; Ryu, S.H.; Suh, P.-G. DJ-1 contributes to adipogenesis and obesity-induced inflammation. Scientific reports 2014, 4, 4805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.Y.; Lu, S.-Y.; Sivasubramaniyam, T.; Revelo, X.S.; Cai, E.P.; Luk, C.T.; Schroer, S.A.; Patel, P.; Kim, R.H.; Bombardier, E. DJ-1 links muscle ROS production with metabolic reprogramming and systemic energy homeostasis in mice. Nature communications 2015, 6, 7415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Chen, S. DJ-1 in neurodegenerative diseases: Pathogenesis and clinical application. Progress in Neurobiology 2021, 204, 102114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ma, X.; Fujioka, H.; Liu, J.; Chen, S.; Zhu, X. DJ-1 regulates the integrity and function of ER-mitochondria association through interaction with IP3R3-Grp75-VDAC1. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2019, 116, 25322–25328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, B.K.; Urano, Y.; Saito, Y.; Noguchi, N. Redox-sensitive DJ-1 protein: an insight into physiological roles, secretion, and therapeutic target. Redox Experimental Medicine 2022, 2022, R96–R115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M.A. The role of cysteine oxidation in DJ-1 function and dysfunction. Antioxidants & redox signaling 2011, 15, 111–122. [Google Scholar]

- Girotto, S.; Cendron, L.; Bisaglia, M.; Tessari, I.; Mammi, S.; Zanotti, G.; Bubacco, L. DJ-1 is a copper chaperone acting on SOD1 activation. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2014, 289, 10887–10899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, S.E.; Mouradian, M.M. Cytoprotective mechanisms of DJ-1 against oxidative stress through modulating ERK1/2 and ASK1 signal transduction. Redox biology 2018, 14, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, L.; Johnson, D.A.; Johnson, J.A. Keap1-Nrf2 activation in the presence and absence of DJ-1. European Journal of Neuroscience 2010, 31, 967–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakkittukandiyil, A.; Sajini, D.V.; Karuppaiah, A.; Selvaraj, D. The principal molecular mechanisms behind the activation of Keap1/Nrf2/ARE pathway leading to neuroprotective action in Parkinson's disease. Neurochemistry International 2022, 156, 105325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, R.H.; Peters, M.; Jang, Y.; Shi, W.; Pintilie, M.; Fletcher, G.C.; DeLuca, C.; Liepa, J.; Zhou, L.; Snow, B.; et al. DJ-1, a novel regulator of the tumor suppressor PTEN. Cancer Cell 2005, 7, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.H.; Brooke, S.M.; Zemlyak, I.; Sapolsky, R.M. Evidence for caspase effects on release of cytochrome c and AIF in a model of ischemia in cortical neurons. Neurosci Lett 2010, 469, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, W. Novel insights into PARK7 (DJ-1), a potential anti-cancer therapeutic target, and implications for cancer progression. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2020, 9, 1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adjemian, S.; Oltean, T.; Martens, S.; Wiernicki, B.; Goossens, V.; Vanden Berghe, T.; Cappe, B.; Ladik, M.; Riquet, F.B.; Heyndrickx, L.; et al. Ionizing radiation results in a mixture of cellular outcomes including mitotic catastrophe, senescence, methuosis, and iron-dependent cell death. Cell Death Dis 2020, 11, 1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Liu, X.; Zhao, T.; Li, F.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, P.; Hirayama, R.; Chen, W.; Jin, X.; Zheng, X.; et al. Comparable radiation sensitivity in p53 wild-type and p53 deficient tumor cells associated with different cell death modalities. Cell Death Discov 2021, 7, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.X.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.L.; Wei, Q.; Lin, R.R.; Kang, R.; Ruan, Y.; Lin, Z.H.; Xue, N.J.; Zhang, B.R.; et al. Nuclear DJ-1 Regulates DNA Damage Repair via the Regulation of PARP1 Activity. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawai, H.; Domae, N. Discrimination between primary necrosis and apoptosis by necrostatin-1 in Annexin V-positive/propidium iodide-negative cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2011, 411, 569–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rieger, A.M.; Nelson, K.L.; Konowalchuk, J.D.; Barreda, D.R. Modified annexin V/propidium iodide apoptosis assay for accurate assessment of cell death. J Vis Exp 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohar, K.; Giladi, E.; Eliyahu, T.; Linial, M. Oxidative Stress and Its Modulation by Ladostigil Alter the Expression of Abundant Long Non-Coding RNAs in SH-SY5Y Cells. Noncoding RNA 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzam, T.; Raskin, A.; Makovitzki, A.; Brem, H.; Vierling, P.; Lineal, M.; Domb, A.J. Cationic polysaccharides for gene delivery. Macromolecules 2002, 35, 9947–9953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, M.A.; Currie, M.J.; Robinson, B.A.; Dachs, G.U. Optimizing transfection of primary human umbilical vein endothelial cells using commercially available chemical transfection reagents. Journal of biomolecular techniques: JBT 2010, 21, 66. [Google Scholar]

- Zohar, K.; Linial, M. Knockdown of DJ-1 Resulted in a Coordinated Activation of the Innate Immune Antiviral Response in HEK293 Cell Line. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, J.; Gao, Y.; Li, Y.; Feng, C.; Song, C.; Ning, Z.; Zhou, X.; Zhao, J.; Feng, M.; et al. LncSEA: a platform for long non-coding RNA related sets and enrichment analysis. Nucleic Acids Res 2021, 49, D969–D980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Fang, J.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Mao, M.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, L.; Pian, C. NcPath: a novel platform for visualization and enrichment analysis of human non-coding RNA and KEGG signaling pathways. Bioinformatics 2023, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogakou, E.P.; Pilch, D.R.; Orr, A.H.; Ivanova, V.S.; Bonner, W.M. DNA double-stranded breaks induce histone H2AX phosphorylation on serine 139. Journal of biological chemistry 1998, 273, 5858–5868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zohar, K.; Linial, M. Knockdown of DJ-1 Resulted in a Coordinated Activation of the Innate Immune Antiviral Response in HEK293 Cell Line. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 7550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlattner, U. The Complex Functions of the NME Family-A Matter of Location and Molecular Activity. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, H.; Feng, X.; Liu, M.; Gong, H.; Zhou, X. SnoRNA and lncSNHG: Advances of nucleolar small RNA host gene transcripts in anti-tumor immunity. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1143980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booy, E.P.; Gussakovsky, D.; Choi, T.; McKenna, S.A. The noncoding RNA BC200 associates with polysomes to positively regulate mRNA translation in tumor cells. J Biol Chem 2021, 296, 100036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toiber, D.; Erdel, F.; Bouazoune, K.; Silberman, D.M.; Zhong, L.; Mulligan, P.; Sebastian, C.; Cosentino, C.; Martinez-Pastor, B.; Giacosa, S. SIRT6 recruits SNF2H to DNA break sites, preventing genomic instability through chromatin remodeling. Molecular cell 2013, 51, 454–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smeenk, G.; Wiegant, W.W.; Marteijn, J.A.; Luijsterburg, M.S.; Sroczynski, N.; Costelloe, T.; Romeijn, R.J.; Pastink, A.; Mailand, N.; Vermeulen, W.; et al. Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation links the chromatin remodeler SMARCA5/SNF2H to RNF168-dependent DNA damage signaling. J Cell Sci 2013, 126, 889–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Lv, S.; Wu, M.; Wang, X.; Deng, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, K.; Zhao, H.; Zhu, X.; Ye, M. HOTAIR-EZH2 inhibitor AC1Q3QWB upregulates CWF19L1 and enhances cell cycle inhibition of CDK4/6 inhibitor palbociclib in glioma. Clinical and Translational Medicine 2020, 10, 182–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, L.; Ju, H.-q.; Yang, Z.; Ge, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, F.; Yang, L.; Gong, H.; Shi, C.; Qu, L. Mitochondrial long non-coding RNA GAS5 tunes TCA metabolism in response to nutrient stress. Nature metabolism 2021, 3, 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Watabe, K.; Zhang, X.; Bai, C.; Xu, M.; Wu, F.; Mo, Y.Y. Negative regulation of lncRNA GAS5 by miR-21. Cell Death Differ 2013, 20, 1558–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Zhang, Y. Depression of lncRNA MINCR antagonizes LPS-evoked acute injury and inflammatory response via miR-146b-5p and the TRAF6-NFkB signaling. Mol Med 2021, 27, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Ji, F.; Sun, X.; Liu, H.; Zhang, C. LncRNA SNHG15 Promotes Oxidative Stress Damage to Regulate the Occurrence and Development of Cerebral Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury by Targeting the miR-141/SIRT1 Axis. J Healthc Eng 2021, 2021, 6577799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, Y.; Ma, Z.; Lu, J.; Feng, J. LncRNA SNHG15: A new budding star in human cancers. Cell Prolif 2020, 53, e12716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, Q.; Qiu, M. Long noncoding RNA SNHG15 promotes human breast cancer proliferation, migration and invasion by sponging miR-211-3p. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2018, 495, 1594–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zohar, K.; Giladi, E.; Eliyahu, T.; Linial, M. Alteration in long noncoding RNAs in response to oxidative stress and ladostigil in SH-SY5Y cells. bioRxiv 2022, 2022.2002. 2020.481187. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, H.; Fu, K.; Wang, D.; Mu, C.; Wang, G. Oxidized DJ-1 interacts with the mitochondrial protein BCL-XL. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2011, 286, 35308–35317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, M.; Graos, M.; Anjo, S.I.; Manadas, B. Modulation of signaling pathways by DJ-1: An updated overview. Redox Biol 2022, 51, 102283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.-X.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.-L.; Wei, Q.; Lin, R.-R.; Kang, R.; Ruan, Y.; Lin, Z.-H.; Xue, N.-J.; Zhang, B.-R. Nuclear DJ-1 Regulates DNA Damage Repair via the Regulation of PARP1 Activity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 8651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, P.L.; Purman, C.; Porter, S.I.; Nganga, V.; Saini, A.; Hayer, K.E.; Gurewitz, G.L.; Sleckman, B.P.; Bednarski, J.J.; Bassing, C.H.; et al. DNA double-strand breaks induce H2Ax phosphorylation domains in a contact-dependent manner. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 3158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryankalayil, M.J.; Bylicky, M.A.; Martello, S.; Chopra, S.; Sproull, M.; May, J.M.; Shankardass, A.; MacMillan, L.; Vanpouille-Box, C.; Dalo, J.; et al. Microarray analysis identifies coding and non-coding RNA markers of liver injury in whole body irradiated mice. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Liao, W.J.; Liao, J.M.; Liao, P.; Lu, H. Ribosomal proteins: functions beyond the ribosome. J Mol Cell Biol 2015, 7, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golomb, L.; Volarevic, S.; Oren, M. p53 and ribosome biogenesis stress: the essentials. FEBS letters 2014, 588, 2571–2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindström, M.S.; Bartek, J.; Maya-Mendoza, A. p53 at the crossroad of DNA replication and ribosome biogenesis stress pathways. Cell Death & Differentiation 2022, 29, 972–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moll, U.M.; Petrenko, O. The MDM2-p53 interaction. Mol Cancer Res 2003, 1, 1001–1008. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Deisenroth, C.; Zhang, Y. RP-MDM2-p53 Pathway: Linking Ribosomal Biogenesis and Tumor Surveillance. Trends Cancer 2016, 2, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimta, A.A.; Tigu, A.B.; Braicu, C.; Stefan, C.; Ionescu, C.; Berindan-Neagoe, I. An Emerging Class of Long Non-coding RNA With Oncogenic Role Arises From the snoRNA Host Genes. Front Oncol 2020, 10, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huldani, H.; Gandla, K.; Asiri, M.; Romero-Parra, R.M.; Alsalamy, A.; Hjazi, A.; Najm, M.A.A.; Fawaz, A.; Hussien, B.M.; Singh, R. A comprehensive insight into the role of small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs) and SNHGs in human cancers. Pathol Res Pract 2023, 249, 154679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, W.; Ba, Z.; Gao, M.; Wu, Y.; Ma, Y.; Amiard, S.; White, C.I.; Rendtlew Danielsen, J.M.; Yang, Y.G.; Qi, Y. A role for small RNAs in DNA double-strand break repair. Cell 2012, 149, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraemer, A.; Anastasov, N.; Angermeier, M.; Winkler, K.; Atkinson, M.J.; Moertl, S. MicroRNA-mediated processes are essential for the cellular radiation response. Radiat Res 2011, 176, 575–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, J.; Peng, C.; Pei, W.; Zhu, W.; Zhang, S.; Cao, H.; Qi, X.; Tong, J.; Jiao, Y. A novel role of long non-coding RNAs in response to X-ray irradiation. Toxicology In Vitro 2015, 30, 536–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Ren, P.; Zhang, Y.; Gong, B.; Yu, D.; Sun, X. Long non-coding RNA GAS5 increases the radiosensitivity of A549 cells through interaction with the miR-21/PTEN/Akt axis. Oncol Rep 2020, 43, 897–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakur, S.; Cahais, V.; Turkova, T.; Zikmund, T.; Renard, C.; Stopka, T.; Korenjak, M.; Zavadil, J. Chromatin Remodeler Smarca5 Is Required for Cancer-Related Processes of Primary Cell Fitness and Immortalization. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, J.; Lou, S.; Ying, M.; Yang, B. DJ-1 as a human oncogene and potential therapeutic target. Biochemical pharmacology 2015, 93, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, J.; Ren, H.; Jia, N.; Fei, E.; Zhou, T.; Jiang, P.; Wu, M.; Wang, G. DJ-1 decreases Bax expression through repressing p53 transcriptional activity. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2008, 283, 4022–4030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ensembl | Gene name | Typea | Gene Description | # exons |

Size (nt) | Hybb | Trend OX |

Trend KD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ENSG00000225569 | CCT4P2 | PG | chaperonin w TCP1 subunit 4 PG2 | 3 | 1548 | S | U | D |

| ENSG00000234084 | NA | Lnc | Novel | 3 | 577 | C | U | D |

| ENSG00000242600 | NA | TPG | mannose binding lectin 1, PG | 4 | 758 | - | U | D |

| ENSG00000245112 | SMARCA5-AS1 | L-AS | SMARCA5 AS RNA 1 | 2 | 1149 | C | U | D |

| ENSG00000269984 | NA | L-AS | novel, AS of MYNN | 2 | 3143 | C | U | D |

| ENSG00000198221 | NA | L-DT* | AFDN DT | 2 | 4095 | S | D | D |

| ENSG00000218426 | RPL27AP6 | PG | 60S ribosomal protein L27a PG | 1 | 447 | S | D | U |

| ENSG00000226415 | NA | PG | triosephosphate isomerase 1 PG1 | 1 | 750 | S | D | U |

| ENSG00000229931 | NA | L-AS | ATXN1 AS RNA 1 | 3 | 1913 | - | D | D |

| ENSG00000231154 | NA | L-AS | MORF4L2 AS RNA 1 | 3 | 2086 | C | D | D |

| ENSG00000236778 | INTS6-AS1 | L-AS* | INTS6 AS RNA 1 | 2 | 4305 | - | D | D |

| ENSG00000276168 | RN7SL1 | mis. | RNA of signal recognition particle | 1 | 299 | - | D | U |

| Class (LncSEA) |

Set | # (query) |

Size of set | P-value | Adj. p-value | Jaccard | Simpson a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H3K4me2-3 | 25 | 1802 | 1.80E-23 | 9.00E-23 | 0.014 | 0.455 | |

| H3T11P | 20 | 1863 | 1.84E-16 | 4.60E-16 | 0.011 | 0.364 | |

| RNA Histone Modification | H3K122ac | 20 | 1991 | 6.48E-16 | 1.08E-15 | 0.010 | 0.364 |

| H2AFX | 6 | 945 | 2.59E-04 | 3.24E-04 | 0.006 | 0.109 | |

| Chromatin Regulators | NCOA1 | 3 | 48 | 1.32E-05 | 3.99E-03 | 0.030 | 0.063 |

| Experimental Validated Function |

cancer progression | 7 | 307 | 1.68E-08 | 9.07E-07 | 0.020 | 0.127 |

| cell metastasis | 6 | 264 | 1.93E-07 | 6.94E-06 | 0.019 | 0.109 | |

| cell cycle | 5 | 143 | 2.57E-07 | 6.94E-06 | 0.026 | 0.091 | |

| proliferation | 8 | 838 | 1.16E-06 | 2.51E-05 | 0.009 | 0.145 | |

| RNA Protein Interaction | DDX3X | 26 | 961 | 6.65E-32 | 6.69E-28 | 0.026 | 0.473 |

| ATXN2 | 26 | 1032 | 4.20E-31 | 2.11E-27 | 0.025 | 0.473 | |

| CSTF2T | 26 | 1328 | 2.75E-28 | 9.23E-25 | 0.019 | 0.473 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).