1. Introduction

Understanding the biological effects of low-dose ionizing radiation (LDIR) is important since healthcare workers and the general public are exposed to varied levels of radiation [

1]. Toward this,

in vitro studies using humans, non-human animals, and cloned cells have been conducted. However, the biological effects of LDIR remain unclear as direct means of evaluating or understanding these effects are unavailable [

2,

3]. In humans, IR induces the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which induce genotoxic stress and alter DNA damage reactions, enabling its application in the interventional radiology of cancer [

4,

5]. High-dose IR causes DNA lesions, indicating that many proteins act on the DNA to alter important cellular events, such as cell cycle regulation, signaling, replication, transcription, and DNA repair [

6,

7,

8,

9]. RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) have recently been proposed as new players in DNA damage response by acting on the chromatin region [

10,

11,

12]. However, transcriptional response in conjunction with DNA repair proteins and LDIR-mediated post-transcriptional gene regulation by RBPs has not been studied.

Human antigen R (HuR)—an RBP—acts as a survival factor in IR (10 Gy/various time points)-induced DNA damage by modulating the translation of a subset of target mRNAs [

13]. However, the impact of low-dose-rate IR (<5 Gy/h) on HuR-mediated post-transcriptional gene regulation needs to be explored using a transcriptome-wide approach. Ultraviolet (UV) crosslinking and immunoprecipitation (CLIP) with high-throughput sequencing—the most widely used transcriptomic approach for mapping RNA-protein interaction sites—has opened new avenues for understanding the complex interaction network between RBPs and RNAs within the cell [

14,

15,

16]. Over the past decade, more derivatives of CLIP-based methods have been developed to overcome technical challenges and increase efficiency [

17,

18,

19,

20]. Most CLIP-derivative methods rely on irradiating cells with UV light to induce covalent bond formation between proteins and directly associated RNAs. Considering that physical inducer of crosslinking, such as UV light, can induce molecular crosslinking between RBPs and RNAs, we aimed to investigate whether IR could induce crosslinking between RNAs and proteins, revealing its contribution to post-transcriptional gene regulation [

21].

Here, we used LDIR-CLIP sequencing to capture the HuR-RNA interactome to identify HuR target mRNAs under LDIR exposure to understand the biological effects of LDIR in pathophysiological conditions, such as cancer. Our results revealed that LDIR did not affect HuR localization or phosphorylation; however, the stability of the HuR protein following 12 h irradiation at 0.05 Gy correlated with the decreased stability of HuR target mRNAs. These findings indicate that LDIR exposure for a relatively long duration may exert biological effects.

2. Results

2.1. LDIR Promotes Crosslinking of RNA-Binding Protein HuR with Its Target RNAs

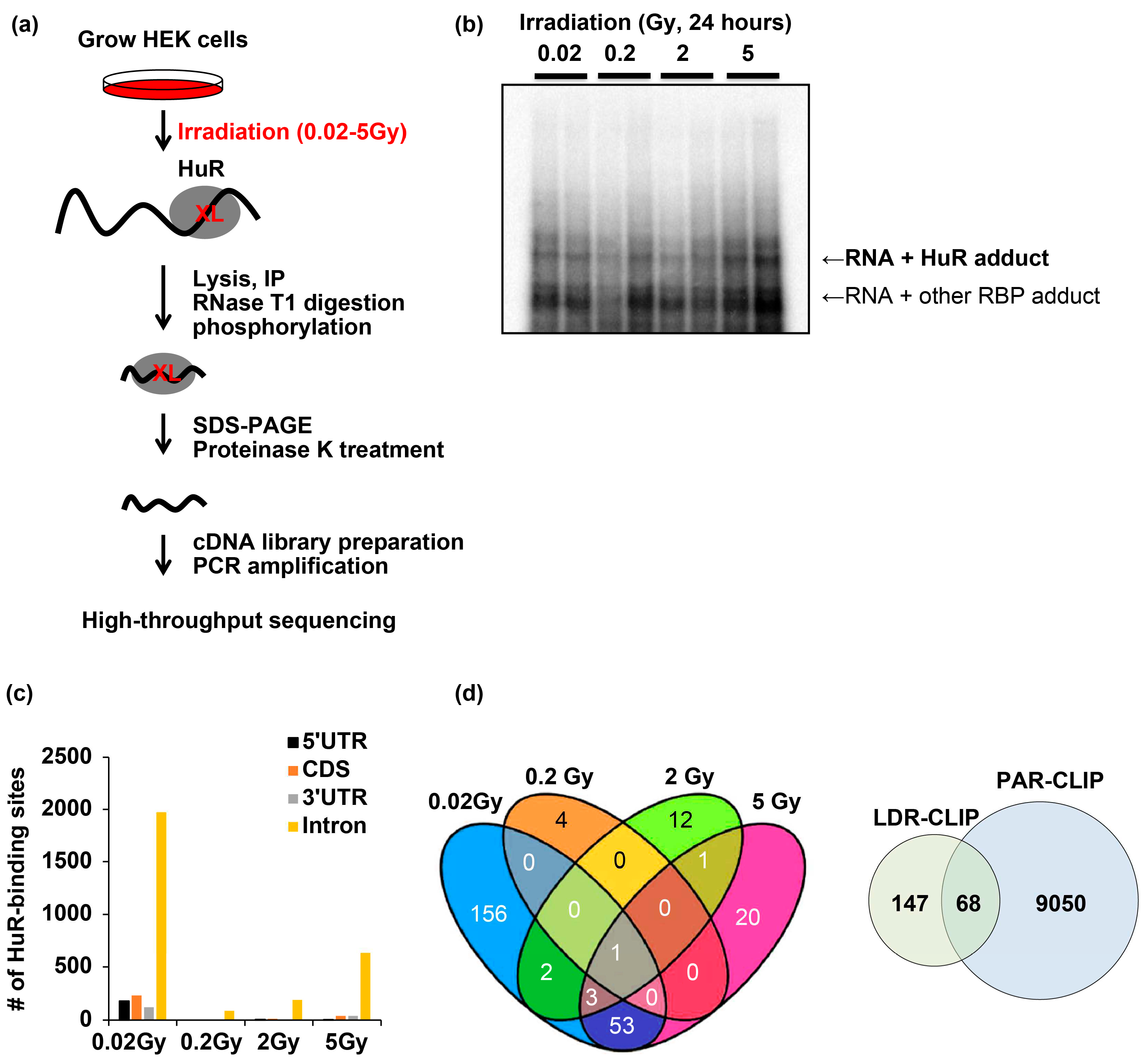

To profile transcripts crosslinked with RBP HuR (

Figure 1a), we irradiated human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells at doses of 0.02–5 Gy. After 24 h irradiation, the cells were lysed and centrifuged, and the supernatant was collected. After HuR immunoprecipitation and RNase T1 digestion, the protected RNA fragments were phosphorylated and subjected to SDS-PAGE. Autoradiography of RNA fragments crosslinked with HuR was performed to determine the complex size using SDS-PAGE (

Figure 1b). Next, the complex was isolated and treated with proteinase K to purify RNAs that were then used for cDNA library preparation, PCR amplification, and high-throughput RNA sequencing.

HuR LDIR-CLIP sequencing identified RNA fragments crosslinked to HuR and protected from RNase T1-mediated digestion. The largest number of independent RNA fragments was profiled after 24 h irradiation at doses of 0.02–5 Gy. In the 0.02 Gy-irradiated samples, 179 instances of crosslinking occurred in the 5′ untranslated region (UTR), 231 in the codon-determining sequences (CDS), 120 in the 3′ UTR, and 1973 in the intronic sequences across 2517 transcripts. (

Figure 1c,

Supplementary Table S1). Moreover, 53 common transcripts were isolated after 0.02 and 5 Gy irradiation (

Figure 1d,

Left), and 68 transcripts overlapped with HuR PAR-CLIP, which was 0.9% of the total reads from the previous PAR-CLIP analysis [

15] (

Figure 1d,

Right, Supplementary Table S2). These results demonstrate that LDIR promotes HuR crosslinking with RNAs in a dose-dependent manner.

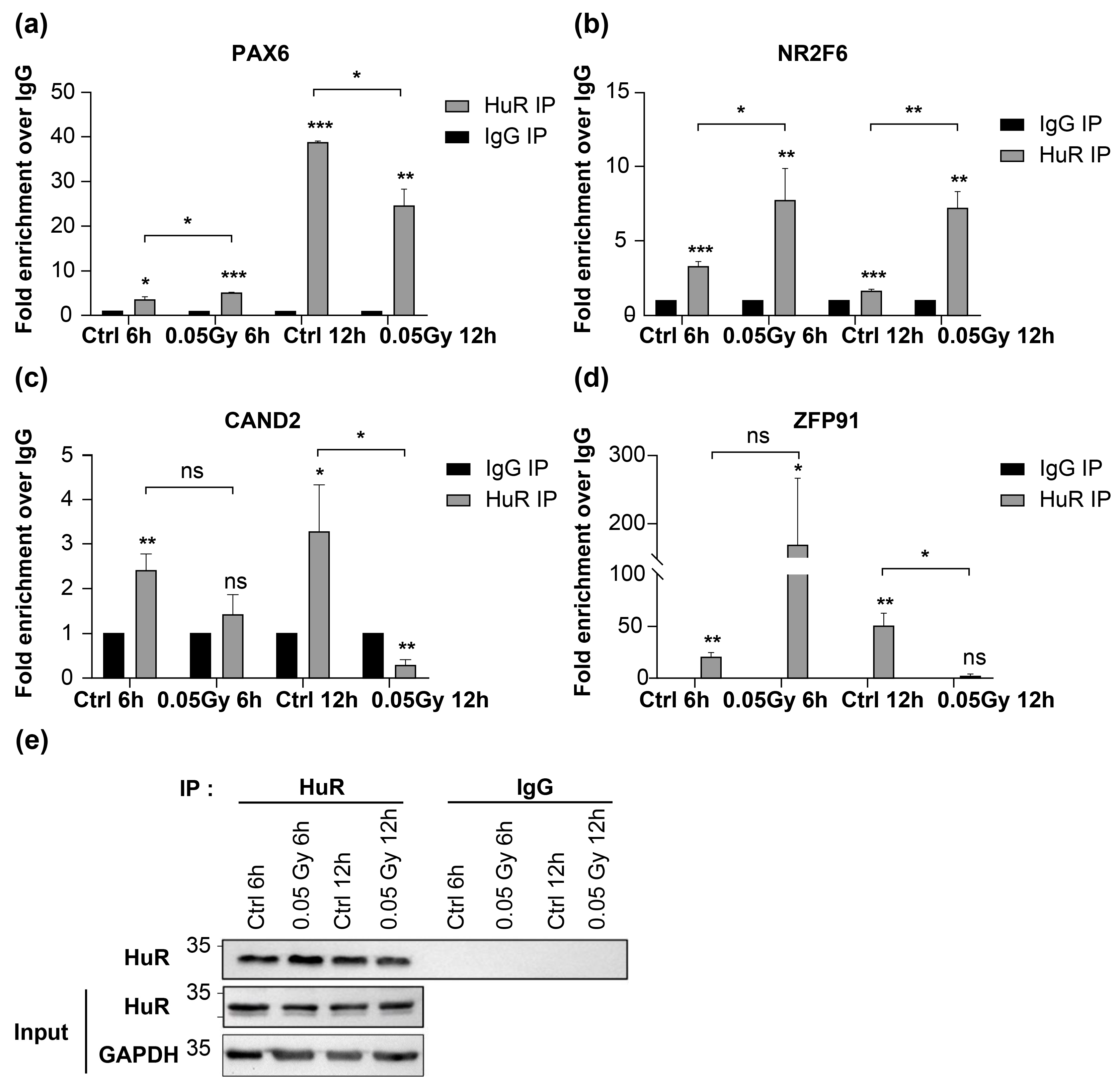

To verify crosslinking of HuR and bound transcripts, we selected transcripts containing HuR-bound sequences in their CDS and UTRs owing to the roles of HuR in target mRNA stability, localization, and translation. We focused on transcriptional regulators that broadly affect gene expression in response to LDIR.

PAX6 (5′ UTR),

NR2F6 (5′ UTR),

CAND2 (5′ UTR), and

ZFP91 (5′ UTR and CDS) were exclusively detected in the 0.02 Gy group following LDIR-CLIP sequencing and HuR PAR-CLIP. Moreover, HuR RIP RT-qPCR analysis revealed enrichment of these transcripts in HuR immunopellets, although the relative enrichment of the transcripts varied irrespective of 0.05 Gy irradiation in HEK293 cells (

Figure 2a–2d). Additionally, we confirmed the successful immunoprecipitation of HuR from each sample (

Figure 2e). Therefore, LDIR-CLIP sequencing is a tool for investigating the biochemical interactions between HuR and target mRNAs in human cell lines.

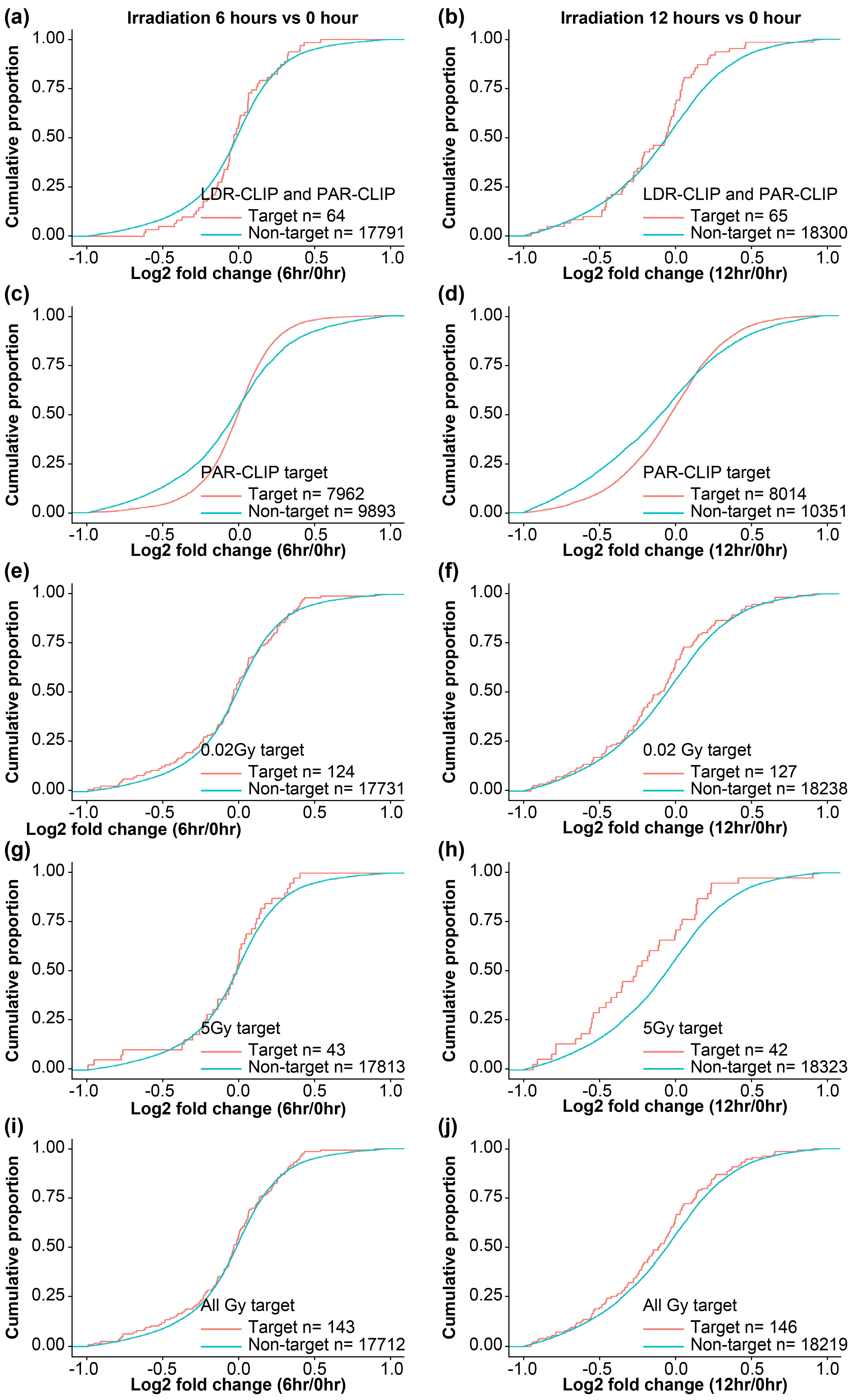

2.2. LDIR Modulates the Stability of HuR-Crosslinked mRNAs

To evaluate the consequences of HuR and its target mRNA interaction upon LDIR exposure, we generated high-throughput RNA-sequencing datasets using total RNA isolated from HEK293 cells with or without exposure to 0.02 and 5 Gy irradiation after 6 or 12 h (

Supplementary Table S3). Cumulative distribution function (CDF) plots were generated by dividing a group of transcripts profiled using PAR-CLIP analysis [

15] and/or LDIR-CLIP sequencing to determine changes in HuR target RNA expression (

Figure 3). We observed similar patterns of HuR target RNAs using LDIR-CLIP and PAR-CLIP (

Figure 3a, 3b). Moreover, 0.05 Gy irradiation stabilized HuR target RNAs detected by PAR-CLIP, shifting the cumulative distribution function slightly to the right after 12 h compared with that after 6 h (

Figure 3c, 3d). We selected HuR target RNAs from LDIR-CLIP following 0.02 Gy irradiation (

Figure 1e) from the total RNA-seq. Our results revealed that 0.02 Gy irradiation slightly reduced the expression of a subset of HuR target RNAs detected using LDIR-CLIP (

Figure 3e, 3f). Similarly, 5 Gy irradiation reduced the expression of a subset of HuR target RNAs detected using LDIR-CLIP (

Figure 3g, 3h). Comparison of the target RNAs obtained after treatment with all the tested doses of irradiation with the non-target RNAs showed that LDIR decreased the expression of HuR target RNAs at 6 and 12 h exposure to LDIR (

Figure 3i, 3j), indicating that LDIR reduced the expression of a subset of HuR target RNAs detected using LDIR-CLIP in HEK293 cells; this prompted us to hypothesize that LDIR negatively impacts the expression of HuR target genes (

Figure 4).

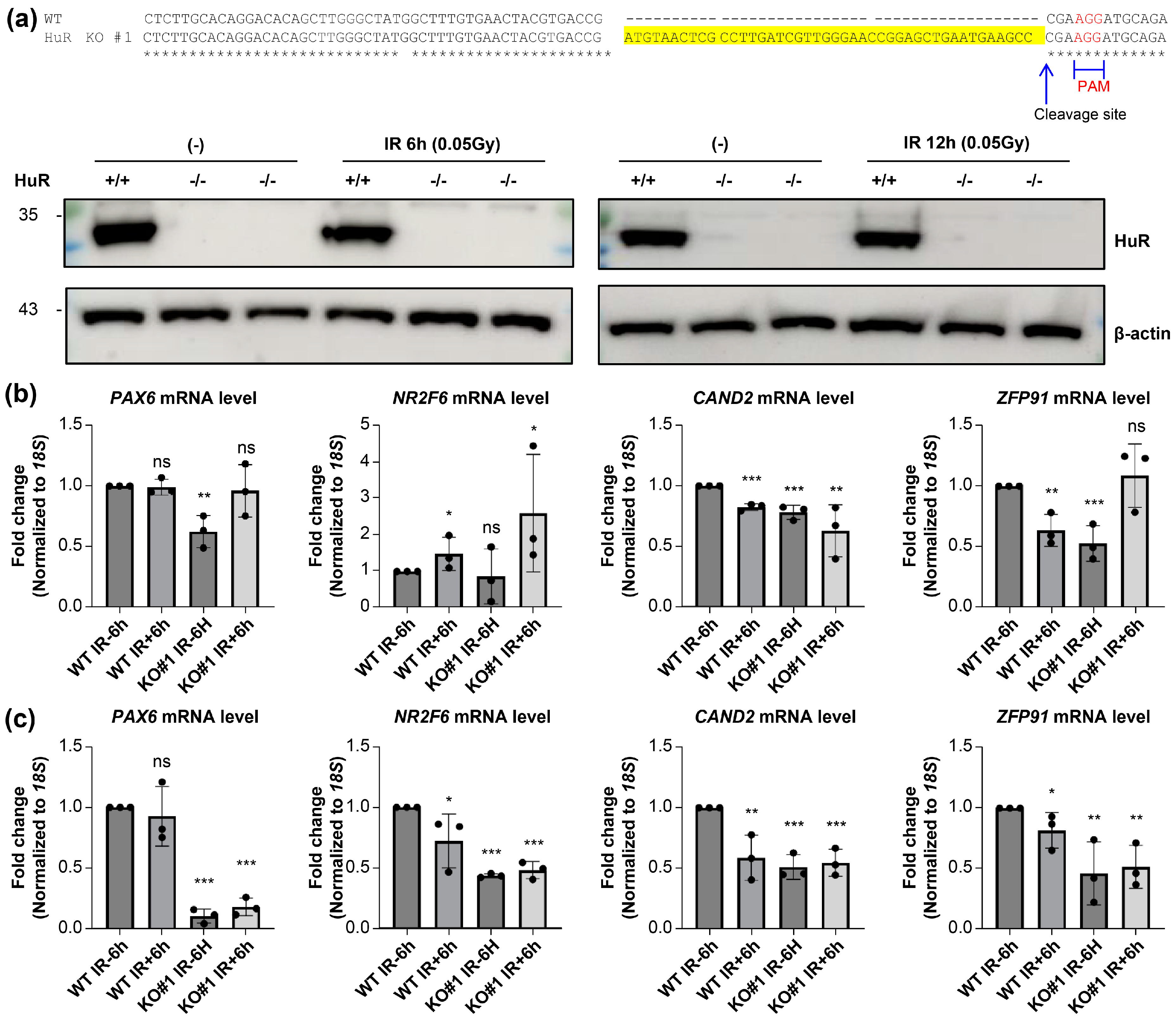

Next, we generated a HuR KO cell line using the CRISPR/Cas9 system to investigate whether LDIR-mediated repression of gene expression was HuR-dependent (

Figure 4a and

Supplementary Figure S1a). Although we did not observe significant changes following 6 h irradiation at 0.05 Gy (

Figure 4b), 12 h exposure to 0.05 Gy irradiation reduced the steady-state expression levels of HuR target genes, consistent with the observation that HuR KO considerably decreased the levels of HuR target mRNAs (

Figure 4c). This implies that LDIR suppressed HuR activity, leading to decreased expression of HuR target genes, consistent with previous observations that HuR stabilizes its target mRNAs [

22,

23,

24].

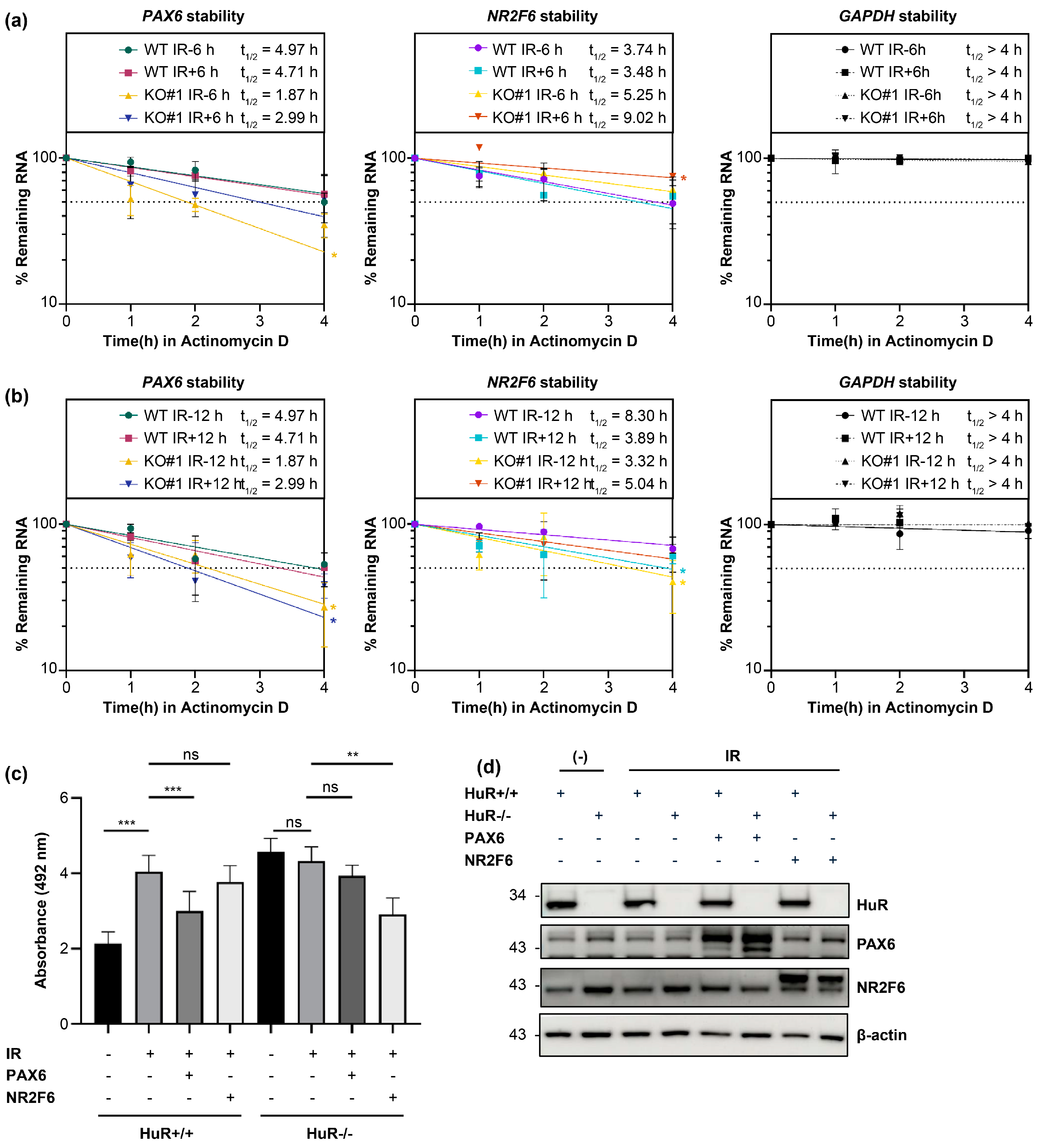

We next confirmed whether HuR KO and LDIR modulate the stability of HuR target mRNAs by measuring their stability. We treated HEK293 cells with actinomycin D 30 min before 0.05 Gy irradiation to shut off mRNA transcription. We harvested and lysed the cells at 0, 1, 2, and 4 h post-irradiation and performed RT-qPCR to measure the stability of these mRNAs. The stability of

GAPDH—a HuR non-target mRNA—in HuR KO did not change significantly after 0.05 Gy irradiation. However, we observed that 1) 0.05 Gy irradiation in wild-type (WT) decreased the stability of HuR target mRNAs, and prolonged exposure (0.05 Gy/12 h) showed a more profound impact than 0.05 Gy/6 h, consistent with the observation that 12 h exposure decreased the steady-state levels of target mRNAs more significantly than 6 h exposure. 2) HuR KO without 0.05 Gy irradiation significantly decreased the half-life of HuR target mRNAs, and 3) HuR KO with 0.05 Gy/6 or 12 h irradiation fluctuated the stability of HuR target mRNAs depending on the incubation time (

Figure 5a, 5b and

Supplementary Figure S1b, 1c).

Furthermore, we observed no changes in the protein levels of HuR target mRNAs. This is because the incubation time (6 and 12 h) was insufficient to alter their translational levels. Little or no amount of HuR was crosslinked upon LDIR, barely influencing the expression of target genes (

Figure 5d), indicating that HuR increased and decreased the stability of HuR target mRNAs under normal conditions and upon 0.05 Gy irradiation, respectively.

To examine the molecular mechanisms by which HuR affects the decay of target mRNAs upon LDIR exposure, we hypothesized that LDIR influences HuR function by altering the stability of HuR target mRNAs. Cellular stress can influence the nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling of HuR, leading to changes in the landscape of HuR target RNAs [

25,

26]. We observed no influence on the HuR subcellular location after 0.05 Gy irradiation (

Supplementary Figure S2a). Notably, HuR has numerous phosphorylation residues, and post-translational modification can influence the subcellular localization of HuR, and binding of HuR to target mRNAs [

27,

28,

29]. We observed that the phosphorylation status of HuR was not influenced by 0.05 Gy irradiation regardless of the exposure time compared with that in the control group (

Supplementary Figure S2b and S2C). HuR protein stability can be modulated to maintain cellular homeostasis in response to stresses, such as heat shock [

30]. Interestingly, HuR protein stability slightly increased with the irradiation dose compared with that in the control (

Supplementary Figure S2d), suggesting that HuR levels might increase when the irradiant energy crosses a certain threshold. These results indicate that LDIR did not influence the phosphorylation and cellular distribution of HuR but could increase the stability of HuR protein.

Finally, we investigated whether LDIR-influenced cell viability depended on HuR target genes. We overexpressed PAX6 and NR2F6, confirmed our results using western blot analysis (

Figure 5d), and measured the cell viability after 6 days of 0.05 Gy irradiation (

Figure 5c). We found that 0.05 Gy irradiation increased the cell viability of WT compared with WT without irradiation. However, the cell viability of HuR KO cells subjected to 0.05 Gy irradiation did not change significantly, indicating that HuR was required to increase cell viability. Furthermore, PAX6 overexpression in WT subjected to 0.05 Gy irradiation decreased the cell viability compared with WT (without PAX6 overexpression) subjected to 0.05 Gy irradiation. PAX6 overexpression in HuR KO cells subjected to 0.05 Gy irradiation did not significantly change the cell viability. This indicates that PAX6 depletion might be required for HuR-mediated cell viability after 0.05 Gy irradiation. Moreover, we observed no change in the cell viability after 0.05 Gy irradiation, and NR2F6 overexpression reduced cell viability with no change in PAX6 overexpression in HuR KO subjected to irradiation. This confirms that PAX6 depletion might be required for HuR-mediated cell viability after 0.05 Gy irradiation.

3. Discussion

IR modulates several biological processes, which, in turn, affect post-transcriptional gene regulation. To gain insights into the effect of LDIR on gene expression at the RNA level, we investigated changes in the HuR-bound RNA transcriptome following LDIR exposure in HEK293 cells. LDIR-CLIP sequencing showed that IR rather than UV light-regulated the post-transcriptome. Moreover, the number of HuR target RNAs identified using LDIR-CLIP sequencing was much lower than that identified using HuR PAR-CLIP.

It is plausible that LDIR produces ROS, such as H

2O

2, which could contribute to HuR oxidation and RNA crosslinking stochastically with much less efficiency than UV light [

31]. LDIR-induced RNA modification could alter RNA base sequence and thus decrease the sensitivity of RBP-RNA interactions [

12,

32,

33]. A relatively high dose of IR (10 Gy) reportedly promotes global dissociation of the HuR-mRNA complex [

34]. Consistent with this observation, we found that the overall number of HuR-binding sites on target mRNAs was decreased after irradiation at >0.2 Gy compared with that observed at 0.02 Gy irradiation in HEK293 cells. The assembly and remodeling of RBP-RNA complexes are dynamic and influenced by time- and space-dependent stochastic fluctuations in the expression and localization of RBP. In our study, LDIR did not affect HuR localization or phosphorylation; however, the stability of the HuR protein following 12 h irradiation at 0.05 Gy correlated with the decreased stability of HuR target mRNAs. These findings indicate that LDIR exposure for a relatively long duration may exert biological effects.

Here, we report the role of HuR in mediating the biological effects of LDIR. In a previous study, the 3ʹ UTR of p53 bound to HuR in a UVC-dependent manner

in vitro and

in vivo. HuR-overexpressing RKO cells displayed elevated p53 levels; however, cells with reduced HuR expression showed markedly diminished p53 translation [

35]. Cold-inducible RNA-binding protein (CIRP), or A18 hnRNP or CIRBP, is a cold-shock RNA-binding protein induced by various cellular stresses. Sun et al. [

36] reported that decreased expression of CIRP-induced colony formation and reduced cell viability after irradiation. Additionally, CIRP knockdown cells demonstrated a high DNA damage rate and decreased cell cycle arrest after irradiation. Therefore, in CIRP knockdown cells subjected to irradiation-induced DNA damage, fewer DNA repair processes increased the apoptosis rate [

37].

In this study, we discovered new targets, such as

PAX6,

ZFP91,

NR2F6, and

CAND2, whose expression was controlled by HuR in response to LDIR. Studies have shown that suppressing PAX6 expression increases cell proliferation, decreases apoptosis, and regulates cell cycle arrest in human retinoblastoma [

38] and corneal epithelial cells [

39]. In our study, increased cell viability in response to LDIR decreased in HuR WT cells overexpressing PAX6 but not in HuR KO cells. However, NR2F6 overexpression did not consistently regulate cell viability in LDIR-exposed HuR WT cells. NR2F6 expression reportedly regulates proliferation; particularly, NR2F6 knockdown significantly inhibits lung cancer cells via miR-142-3p [

39,

40]. Therefore, we presumed that NR2F6 RNA expression did not decrease, but PAX6 expression increased in response to LDIR due to a difference in the regulation mechanism of these genes.

Our study has some limitations. First, the exact sites of LDIR-mediated HuR-RNA crosslinking were unclear. Further exploration of molecular events and factors that influence LDIR-mediated crosslinking efficiencies will help elucidate the influence of LDIR on gene regulation. Second, the LDIR effect was similar to that observed when HuR was knocked out in terms of decreased steady-state levels and stability of target mRNA, suggesting that LDIR effects could be HuR-dependent. Therefore, the underlying mechanism(s) by which mRNAs crosslink with HuR upon LDIR exposure needs to be explored.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that HuR can be crosslinked with a set of target RNAs upon LDIR exposure. Furthermore, HuR target mRNAs may be degraded due to the aberrant HuR-mRNA complex formation. Our approach provides a tool for studying post-transcriptional gene regulation in response to LDIR exposure.

4. Methods

4.1. Cell Culture, Plasmids, Transfection, and Irradiation

HEK293 cells were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA) and cultured following the manufacturer’s instructions. Cas9- and sgRNA-expressing vectors pX458 (Addgene #48138) were constructed to generate HuR KO HEK293 cells. pEGFPC2-Pax6 and pDC316-EGFP-mNR2F6 were used to overexpress PAX6 and NR2F6, respectively. pDC316-EGFP-mNR2F6 plasmid DNA was kindly provided by Yan Lu from Fudan University. Plasmid DNAs were transfected into HEK293 and HuR KO HEK293 cell lines using Lipofectamine 2000 (Lipofectamine2000, #MAN0007824, Invitrogen, a subsidiary of Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA, USA). HEK293 and HuR KO HEK293 cells were exposed to 0.05 Gy of γ-rays from a 137Cs irradiation source (Eckert & Ziegler, Berlin, Germany) at a dose rate of 0.22 mGys-1. The transfected cells were harvested 24 h after irradiation.

4.2. Generation of Human HuR Knockout Cell Lines

For CRISPR/Cas9 constructs, we used the pX458 plasmid transiently expressing sgRNA and wild-type SpCas9. Three sgRNAs for HuR were inserted into the pX458 plasmid linearized with BbsI. The primers used for cloning are listed in

Supplementary Table S4.

Genomic DNA was isolated using a Wizard® Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA) and amplified using Phusion polymerase (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) with primers spanning the target sequence from approximately 80 bp upstream to 80 bp downstream of the cleavage site of CRISPR-Cas9. We used a 100 ng template per sample for the first round of PCR amplification. PCR products were purified using a QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen, a subsidiary of Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). For the second-round PCR, 20 ng purified PCR products from the first round were annealed with an Illumina adapter and barcode sequences. The primers used for PCR are listed in

Supplementary Table S4. The resulting products were isolated, purified, mixed, and subjected to 150 paired-end sequencing cycles on the HiSeq system (Illumina, San Diego, Ca, USA). Next, deep-sequencing data were sorted and analyzed with a reference WT sequence using a Cas-Analyzer (

http://www.rgenome.net/cas-analyzer), with the comparison range (R) parameter set to 50, minimum frequency (n) to 1, and WT marker range (r) to 5. To increase accuracy, the extracted data were filtered based on the read number, and the read numbers of WT sequences (same target sequence but in different contexts, including sequencing errors) were combined as a single WT sequence.

Approximately 20,000 cells were seeded in six-well plates containing 3 mL Opti-MEM without penicillin/streptomycin and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. For HuR knockout, 1 μg HuR CRISPR/Cas9 KO plasmid was added to the transfection media to a final volume of 150 μL (solution A). Additionally, 10 μL of Lipofectamine 2000 (Lipofectamine™ 2000, #MAN0007824, Invitrogen) was added to the transfection media to a final volume of 150 μL (solution B). After 5 min, solution A was added to solution B and incubated at 22 °C for 10 min. Afterward, the mixture was added to each well, and the cells were further incubated for 24 h before sorting.

Subsequently, the transfected cells were washed, rinsed with ice-cold phosphate buffer saline, and trypsinized for 5 min in an incubator. Next, the trypsinized cells were transferred into a 15 mL tube and centrifuged at 1,200 rpm for 5 min. The resulting pellets were resuspended in 1 mL culture medium, and green fluorescent protein-positive HuR knockout cell populations were sorted into 3 mL culture media using a FACS Aria cell sorter (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Finally, the cells were analyzed for indel frequency and western blotting.

4.3. MTS Assays

Irradiated cells were seeded into 96-well plates (2 × 103 cells/well; in four replicates) and cell proliferation was quantified using an MTS Assay Kit (CellTiter 96® AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay, #G3580; Promega Corporation) following the manufacturer’s instructions. First, approximately 40 μL MTS solution was added to 200 μL culture media with cells after days 0, 1, 3, and 6 and the mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. Next, cell viability was measured at 492 nm using a Tristar3 Multimode Reader (Berthold Technologies, Bad Wildbad, Germany), and the results were analyzed using MikroWin 2010 software.

4.4. Western Blotting

Total proteins were lysed from cells irradiated on day 6 using ice-cold lysis buffer (PRO-PREP™ Protein Extraction Solution, #17801, iNTRON Biotechnology, Seongnam-si, Gyeonggi -do, Republic of Korea) containing a protease inhibitor (Protease Inhibitor Cocktail powder, #P2714, Sigma-Aldrich, a subsidiary of Merk KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). Next, the lysed protein concentration was measured using BCA reagents (Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Kit, #23227, Thermo Fisher Scientific), and proteins were resolved using 4%–12% gradient SDS-PAGE (Bolt™ Bis-Tris Plus Gels, #MAN0007902, Invitrogen). Afterward, they were transferred onto PVDF membranes (Immobilo-P, #IPVH00010, MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, USA) using a semi-dry electroblotting system (Power Blotter System, #PB0012 and #PB0013, Invitrogen). Next, the membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk or BSA in TBST and probed using primary antibodies against HuR (ms, Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc, Santa Cruz, CA, USA, #sc-5261), phospho-HuR [

40], NR2F6 (ms, Proteintech, Deerfield, IL, USA, #60117-2-lg), PAX6 (rb, Invitrogen, #42-6600), Beta-actin (ms, Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc, #sc-47778), and GAPDH (ms, Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc, #sc-47724). The unbound primary antibodies were washed with TBST, and the membranes were incubated with secondary antibodies at room temperature (22 ℃) for 1 h. Lastly, the protein bands were analyzed using an ECL reagent (ECL Select western blotting Detection Reagent, #RPN2235, Amersham, a subsidiary of GE Healthcare, Waukesha, IL, USA) and a gel documentation system (ImageQuant800, Amersham).

4.5. Phos-tag SDS-PAGE Electrophoresis

HuR phosphorylation was measured by supplementing SDS-polyacrylamide gels (10%) with Phos-tag AAL solution (Wako, Tokyo, Japan, # 304-93525) following the manufacturer’s recommendations. Next, the gels were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane using a transfer buffer containing 0.1% SDS, followed by a standard western blotting procedure.

4.6. LDIR-CLIP-Sequencing Analysis

For HuR LDIR-CLIP, we irradiated HEK293 cells with IR (0.02–5 Gy) to induce RNA and protein cross-linking. Next, the cells were harvested and lysed in three equivalent cell pellet volumes of NP-40 lysis buffer. The resulting cell lysates were treated with 1 U/mL RNase T1 (Fermentas, a subsidiary of Thermo Fisher Scientific), and HuR was immunoprecipitated using HuR antibody (#sc-5261) bound to Protein G Dynabeads. Afterward, the RNA fragments bound to the beads were trimmed using 100 U/mL RNase T1, and the beads were washed with lysis buffer and resuspended in one bead volume of dephosphorylation buffer. Next, the RNA fragments were dephosphorylated and radioactively labeled with [g32P]-ATP. Afterward, the protein-RNA complexes were separated using SDS-PAGE and visualized using autoradiography. The radioactive bands at 36.1 kDa were recovered, and the protein-RNA complex was electroeluted from the gel. Subsequently, the proteins were removed by digestion with 0.2 mg/mL proteinase K buffer (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Lastly, RNA was recovered using acidic phenol/chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation and converted into a cDNA library for sequencing on an Illumina platform. The processed reads were aligned to the reference genome (GRCh37/hg19) using the Bowtie algorithm (0.12.7).

4.7. Ribonucleoprotein Immunoprecipitation

Total cells were lysed in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.5% NP-40) on ice for 10 min and centrifuged at 13,000 rpm at 4 °C for 15 min. Next, the lysates (1–2 mg) were incubated with 1 μg antibody against HuR (#sc-5261) or control IgG (#sc-2025) at 4 °C overnight and incubated with protein A/G Sepharose beads (Santa Cruz, #sc-2003) at 4 °C with gentle rotation for 2 h. Finally, the beads were washed five times with NT2 buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, and 0.05% NP-40), and RNA isolated from the immunopellets via acidic phenol extraction was subjected to RT-qPCR.

4.8. RNA-seq

Total RNA was extracted from HEK-293 cells subjected to LDIR irradiation (0.05 Gy) for the indicated periods and subjected to deep sequencing. Total RNA sequencing was performed on an Illumina GA-II instrument. For RNA-seq, the total RNA quality and quantity were assessed on an Agilent 2100-Bioanalyzer. Afterward, 100 ng RNA was used for first- and second-strand cDNA synthesis, and single-primer isothermal amplification was performed using NuGEN Ovation RNA-sequencing System V2 Kits following the manufacturer’s protocol. The kit amplified polyA-tailed and non-polyA-tailed RNAs and removed the ribosomal RNA. Next, the amplified cDNA was sheared to an average size of 250–450 bases. A sequencing library was prepared using Illumina ChIpSeq Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, the ends of the fragments were repaired using T4 DNA polymerase. Next, Escherichia coli DNA Pol I large fragment (Klenow polymerase), T4 polynucleotide kinase, and adenines were added to the 3′ end. Subsequently, adapters were ligated to 250–300 bp DNA fragments, followed by electrophoresis on a 4% agarose gel. Next, 18 PCR amplification cycles were performed, followed by cluster generation and sequencing on an Illumina Genome Analyzer (GA-II). Sequencing was performed for 42 cycles, and the generated images were analyzed using the Firecrest program, followed by base calls using the Bustard program, which is part of the Illumina Analysis Pipeline package. For RNA-sequencing analysis, the quality of bases was checked using the FASTQC program, and the bases were aligned to the human HG19 genome using the Tophat program, Bowtie algorithm, and Ensembl hg19 (v62) as gene model annotations, followed by genomic mapping. Next, the aligned reads were assembled into transcripts (known and novel) using the Cufflinks program, with Ensembl hg19 (v62) transcripts as a guide. Afterward, fragments per kilobase of the exon model per million mapped reads were calculated after fragment bias correction and normalization to the total hits. Lastly, significant changes in transcript expression levels were calculated using the Cuffdiff program with a false discovery rate of <0.1 and a minimum of five alignments. Data were visualized using the UCSC Genome Browser.

4.9. mRNA Stability Assay

Half-lives of HuR target mRNAs were measured using RT-qPCR. After 6 or 12 h incubation following 0.05 Gy irradiation, the cells were treated with actinomycin D (2.5 μg/mL) to inhibit transcription. Finally, RNA was extracted at various time points to measure the levels of HuR target mRNAs and GAPDH mRNA, and their half-lives were calculated.

4.10. Quantitative RT-PCR Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from cells using TRIzol (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #15596026) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, 1 μg total RNA was reverse-transcribed using random hexamer oligonucleotides and reverse transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific (#EP0753). Real-time PCR was performed using SYBR Green (Thermo Fisher, #A25918) on a QuantStudio3 real-time PCR detection system. Primers used in this study are listed in

Supplementary Table S4.

4.11. Statistical and Reproducibility Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9 software. Comparisons between the two groups were performed using the Student’s t-test. All experiments were repeated at least twice. All error bars represent the means ± standard deviation (SD).

4.12. Data Availability

LDIR- and RNA-sequencing data and the other resources generated in this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

J.W.L., H.-J.Y., K.-W.M., and T.G.S. conceived and designed the research. J.W.L., H.M., J.-H.K., S.K. performed most of the experiments with contributions from Y.-K.K., M.J.S., K.K., C.W.H., H.B.P., M.K., C.L., S.H.C., and J.-W.K. J.W.L., H.M., and S.K analyzed data. J.W.L., J.-H.Y., K.-W.M., and T.G.S. wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank Editage (

www.editage.co.kr) for their assistance with English language editing. This work was supported by the National Research and Development Program funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT, & Future Planning through the Dongnam Institute of Radiological & Medical Sciences under grants [grant numbers 50490-2021, 50495-2022, and 50493-2023]. Funding for open access charges was provided by the Ministry of Science, ICT, and Future Planning. J.W.L., M.J.S., K.K., and K.-W.M. were supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (NRF-2022R1A2C4001528). H.M., S.K., and J.-H.Y. were supported by the start-up fund from the Medical University of South Carolina.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Maqsudur Rashid, A.; Ramalingam, L.; Al-Jawadi, A.; Moustaid-Moussa, N.; Moussa, H. Low dose radiation, inflammation, cancer and chemoprevention. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2019, 95, 506–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullenders, L.; Atkinson, M.; Paretzke, H.; Sabatier, L.; Bouffler, S. Assessing cancer risks of low-dose radiation. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2009, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Han, Z.; Luo, Q.; Wang, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhou, L.; Zuo, H. Radiotherapy modulates tumor cell fate decisions: a review. Radiat. Oncol. 2022, 17, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, R.-X.; Zhou, P.-K. DNA damage response signaling pathways and targets for radiotherapy sensitization in cancer. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valerie, K.; Yacoub, A.; Hagan, M.P.; Curiel, D.T.; Fisher, P.B.; Grant, S.; Dent, P. Radiation-induced cell signaling: inside-out and outside-in. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2007, 6, 789–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iliakis, G.; Wang, Y.; Guan, J.; Wang, H. DNA damage checkpoint control in cells exposed to ionizing radiation. Oncogene 2003, 22, 5834–5847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santivasi, W.L.; Xia, F. Ionizing radiation-induced DNA damage, response, and repair. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014, 21, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sage, E.; Shikazono, N. Radiation-induced clustered DNA lesions: Repair and mutagenesis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2017, 107, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutertre, M.; Lambert, S.; Carreira, A.; Amor-Guéret, M.; Vagner, S. DNA damage: RNA-binding proteins protect from near and far. Trends Biochem Sci. 2014, 39, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.-K.; Lin, W.-L.; Chen, Z.; Liu, H.-w. PARP-1–dependent recruitment of cold-inducible RNA-binding protein promotes double-strand break repair and genome stability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2018, 115, E1759–E1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaric, J.A.; Wüst, S.; Panier, S. New Faces of old Friends: Emerging new Roles of RNA-Binding Proteins in the DNA Double-Strand Break Response. Front Mol Biosci. 2021, 8, 668821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masuda, K.; Abdelmohsen, K.; Kim, M.M.; Srikantan, S.; Lee, E.K.; Tominaga, K.; Selimyan, R.; Martindale, J.L.; Yang, X.; Lehrmann, E.; et al. Global dissociation of HuR-mRNA complexes promotes cell survival after ionizing radiation. EMBO J. 2011, 30, 1040–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kishore, S.; Jaskiewicz, L.; Burger, L.; Hausser, J.; Khorshid, M.; Zavolan, M. A quantitative analysis of CLIP methods for identifying binding sites of RNA-binding proteins. Nat. Methods. 2011, 8, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hafner, M.; Landthaler, M.; Burger, L.; Khorshid, M.; Hausser, J.; Berninger, P.; Rothballer, A.; Ascano, M., Jr.; Jungkamp, A.C.; Munschauer, M.; et al. Transcriptome-wide identification of RNA-binding protein and microRNA target sites by PAR-CLIP. Cell 2010, 141, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Nostrand, E.L.; Pratt, G.A.; Shishkin, A.A.; Gelboin-Burkhart, C.; Fang, M.Y.; Sundararaman, B.; Blue, S.M.; Nguyen, T.B.; Surka, C.; Elkins, K.; et al. Robust transcriptome-wide discovery of RNA-binding protein binding sites with enhanced CLIP (eCLIP). Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 508–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasakis, D.G.; Jacob, A.; Konstantinidou, P.; Meguro, K.; Claypool, D.; Cekan, P.; Haase, A.D.; Hafner, M. A non-radioactive, improved PAR-CLIP and small RNA cDNA library preparation protocol. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter, D.F.; Miao, W.; Yang, X.; Goda, G.A.; Ji, A.L.; Donohue, L.K.H.; Aleman, M.M.; Dominguez, D.; Khavari, P.A. easyCLIP analysis of RNA-protein interactions incorporating absolute quantification. Nat. Commun 2021, 12, 1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blue, S.M.; Yee, B.A.; Pratt, G.A.; Mueller, J.R.; Park, S.S.; Shishkin, A.A.; Starner, A.C.; Van Nostrand, E.L.; Yeo, G.W. Transcriptome-wide identification of RNA-binding protein binding sites using seCLIP-seq. Nat. Protoc. 2022, 17, 1223–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hafner, M.; Katsantoni, M.; Köster, T.; Marks, J.; Mukherjee, J.; Staiger, D.; Ule, J.; Zavolan, M. CLIP and complementary methods. Nat. Rev. Method. Prim. 2021, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.K.; Kim, J.A.; Park, S.J.; Kim, J.K.; Heo, K.; Yang, K.M.; Son, T.G. Low-dose radiation activates Nrf1/2 through reactive species and the Ca(2+)/ERK1/2 signaling pathway in human skin fibroblast cells. BMB Rep. 2013, 46, 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Huang, A.; Zhang, A.; Zhou, C. HuR promotes breast cancer cell proliferation and survival via binding to CDK3 mRNA. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 91, 788–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinman, M.N.; Lou, H. Diverse molecular functions of Hu proteins. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008, 65, 3168–3181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajasingh, J. The many facets of RNA-binding protein HuR. Trends Cardiovasc. Med.. 2015, 25, 684–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.S.; Tang, P.W.; Welles, J.E.; Pan, W.; Javed, Z.; Elhaw, A.T.; Mythreye, K.; Kimball, S.R.; Hempel, N. HuR-dependent SOD2 protein synthesis is an early adaptation to anchorage-independence. Redox Biol. 2022, 53, 102329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Song, J.; Gao, Y.; Huang, S.; Dou, R.; Zhong, P.; Huang, G.; Han, L.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, X.; et al. Hypoxia-induced HIF-1α/lncRNA-PMAN inhibits ferroptosis by promoting the cytoplasmic translocation of ELAVL1 in peritoneal dissemination from gastric cancer. Redox Biol. 2022, 52, 102312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmohsen, K.; Pullmann, R., Jr.; Lal, A.; Kim, H.H.; Galban, S.; Yang, X.; Blethrow, J.D.; Walker, M.; Shubert, J.; Gillespie, D.A.; et al. Phosphorylation of HuR by Chk2 regulates SIRT1 expression. Mol. Cell. 2007, 25, 543–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filippova, N.; Yang, X.; King, P.; Nabors, L.B. Phosphoregulation of the RNA-binding protein Hu antigen R (HuR) by Cdk5 affects centrosome function. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 32277–32287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, J.H.; Abdelmohsen, K.; Srikantan, S.; Guo, R.; Yang, X.; Martindale, J.L.; Gorospe, M. Tyrosine phosphorylation of HuR by JAK3 triggers dissociation and degradation of HuR target mRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 1196–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelmohsen, K.; Srikantan, S.; Yang, X.; Lal, A.; Kim, H.H.; Kuwano, Y.; Galban, S.; Becker, K.G.; Kamara, D.; de Cabo, R.; et al. Ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis of HuR by heat shock. EMBO J. 2009, 28, 1271–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, N.; Corcoran, D.L.; Nusbaum, Jeffrey D.; Reid, David W.; Georgiev, S.; Hafner, M.; Ascano, M.; Tuschl, T.; Ohler, U.; Keene, Jack D. Integrative Regulatory Mapping Indicates that the RNA-Binding Protein HuR Couples Pre-mRNA Processing and mRNA Stability. Mol. Cell 2011, 43, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendel, M.; Delaney, K.; Pandey, R.R.; Chen, K.-M.; Wenda, J.M.; Vågbø, C.B.; Steiner, F.A.; Homolka, D.; Pillai, R.S. Splice site m6A methylation prevents binding of U2AF35 to inhibit RNA splicing. Cell 2021, 184, 3125–3142.e3125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, C.J.T.; Pan, T.; Kalsotra, A. RNA modifications and structures cooperate to guide RNA–protein interactions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, F.; Wei, J.; Cui, X.; Yu, C.; Ni, W.; Bungert, J.; Wu, L.; He, C.; Qian, Z. Post-translational modification of RNA m6A demethylase ALKBH5 regulates ROS-induced DNA damage response. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, 5779–5797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazan-Mamczarz, K.; Galbán, S.; de Silanes, I.L.; Martindale, J.L.; Atasoy, U.; Keene, J.D.; Gorospe, M. RNA-binding protein HuR enhances p53 translation in response to ultraviolet light irradiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003, 100, 8354–8359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, W.; Bergmeier, A.P.; Liao, Y.; Wu, S.; Tong, L. CIRP Sensitizes Cancer Cell Responses to Ionizing Radiation. Radiat. Res. 2021, 195, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, B.; Wang, Y.; Li, B. Suppression of PAX6 promotes cell proliferation and inhibits apoptosis in human retinoblastoma cells. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2014, 34, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouyang, J.; Shen, Y.C.; Yeh, L.K.; Li, W.; Coyle, B.M.; Liu, C.Y.; Fini, M.E. Pax6 overexpression suppresses cell proliferation and retards the cell cycle in corneal epithelial cells. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2006, 47, 2397–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, W.J.; Jakic, B.; Labi, V.; Woelk, J.; Derudder, E.; Baier, G.; Hermann-Kleiter, N. A role for the nuclear receptor NR2F6 in peritoneal B cell homeostasis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.l.; Guan, H.q.; Yang, H.b.; Chen, Y.; Huang, X.y.; Chen, L.; Shen, Z.f.; Wang, L.x. The expression and biological effect of NR2F6 in non-small cell lung cancer. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.H.; Abdelmohsen, K.; Lal, A.; Pullmann, R., Jr.; Yang, X.; Galban, S.; Srikantan, S.; Martindale, J.L.; Blethrow, J.; Shokat, K.M.; et al. Nuclear HuR accumulation through phosphorylation by Cdk1. Genes Dev. 2008, 22, 1804–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

A subset of RNAs targeted by RNA-binding protein HuR was identified using the LDIR-CLIP method. a) Schematic diagram of LDIR-CLIP-sequencing analysis. b) Autoradiograph of RNA fragments crosslinked with HuR upon irradiation at doses of 0.02–5 Gy for 24 h. c) Number of HuR-binding sites on CDS, UTR, and introns following irradiation at 0.02–5 Gy for 24 h. d) (Left) Venn diagrams summarizing the transcripts associated with HuR following irradiation at 0.02–5 Gy for 24 h. (Right) Number of RNA fragments commonly identified using LDIR-CLIP and PAR-CLIP. LDIR, low-dose ionizing radiation. Original blot image is presented in supplementary figure 3; CLIP, crosslinking immunoprecipitation; HuR, human antigen R; UTR, untranslated region; CDS, codon-determining sequences.

Figure 1.

A subset of RNAs targeted by RNA-binding protein HuR was identified using the LDIR-CLIP method. a) Schematic diagram of LDIR-CLIP-sequencing analysis. b) Autoradiograph of RNA fragments crosslinked with HuR upon irradiation at doses of 0.02–5 Gy for 24 h. c) Number of HuR-binding sites on CDS, UTR, and introns following irradiation at 0.02–5 Gy for 24 h. d) (Left) Venn diagrams summarizing the transcripts associated with HuR following irradiation at 0.02–5 Gy for 24 h. (Right) Number of RNA fragments commonly identified using LDIR-CLIP and PAR-CLIP. LDIR, low-dose ionizing radiation. Original blot image is presented in supplementary figure 3; CLIP, crosslinking immunoprecipitation; HuR, human antigen R; UTR, untranslated region; CDS, codon-determining sequences.

Figure 2.

LDIR affects the binding of HuR with target mRNAs. a–d) HuR RIP-qPCR of RNAs profiled in LDIR-CLIP-seq. e) Representative western blot analyzing the relative levels of HuR in samples is shown in (a–d). Original blot images are presented in supplementary figure 3. Data represent the mean ± SD from N = 2 independent experiments. *: p < 0.05; **: p < 0.01, ***: p < 0.001, ns: p > 0.05 from Student’s t-test. HUR, human antigen R; LDIR, low-dose ionizing radiation; CLIP, crosslinking immunoprecipitation.

Figure 2.

LDIR affects the binding of HuR with target mRNAs. a–d) HuR RIP-qPCR of RNAs profiled in LDIR-CLIP-seq. e) Representative western blot analyzing the relative levels of HuR in samples is shown in (a–d). Original blot images are presented in supplementary figure 3. Data represent the mean ± SD from N = 2 independent experiments. *: p < 0.05; **: p < 0.01, ***: p < 0.001, ns: p > 0.05 from Student’s t-test. HUR, human antigen R; LDIR, low-dose ionizing radiation; CLIP, crosslinking immunoprecipitation.

Figure 3.

Comparison of LDIR-CLIP and PAR-CLIP regarding altered gene expression upon LDIR. a, c, e, g, i) Cumulative distribution fraction (CDF) plots of transcripts targeted by HuR after 6 h irradiation. b, d, f, h, j) CDF plots of transcripts targeted by HuR after 12 h irradiation. LDIR, low-dose ionizing radiation; CLIP, crosslinking immunoprecipitation.

Figure 3.

Comparison of LDIR-CLIP and PAR-CLIP regarding altered gene expression upon LDIR. a, c, e, g, i) Cumulative distribution fraction (CDF) plots of transcripts targeted by HuR after 6 h irradiation. b, d, f, h, j) CDF plots of transcripts targeted by HuR after 12 h irradiation. LDIR, low-dose ionizing radiation; CLIP, crosslinking immunoprecipitation.

Figure 4.

Changes in levels of HuR targeted RNA following LDIR. a) (Top) Schematic diagram of deep-sequencing data showing the genomic locus with CRISPR guide sequence (yellow), PAM motif (red), and predicted cleavage site (arrow). (Bottom) Western blot analysis of HEK293 cells expressing the sgRNA targeting the control region or HuR gene. b, c) RT-qPCR to detect PAX6, NR2F6, CAND2, and ZFP91 expression in HuR+/+ and -/- cells upon 0.05 Gy irradiation for 6 h (b) or 12 h (c). Original blot images are presented in supplementary figure 3. Data represent the mean ± SD from N = 3 independent experiments. *: p < 0.05; **: p < 0.01, ***: p < 0.001, ns: p > 0.05 from Student’s t-test. LDIR, low-dose ionizing radiation; HUR, human antigen R.

Figure 4.

Changes in levels of HuR targeted RNA following LDIR. a) (Top) Schematic diagram of deep-sequencing data showing the genomic locus with CRISPR guide sequence (yellow), PAM motif (red), and predicted cleavage site (arrow). (Bottom) Western blot analysis of HEK293 cells expressing the sgRNA targeting the control region or HuR gene. b, c) RT-qPCR to detect PAX6, NR2F6, CAND2, and ZFP91 expression in HuR+/+ and -/- cells upon 0.05 Gy irradiation for 6 h (b) or 12 h (c). Original blot images are presented in supplementary figure 3. Data represent the mean ± SD from N = 3 independent experiments. *: p < 0.05; **: p < 0.01, ***: p < 0.001, ns: p > 0.05 from Student’s t-test. LDIR, low-dose ionizing radiation; HUR, human antigen R.

Figure 5.

LDIR destabilizes HuR-bound mRNAs to enhance cell viability. a, b) mRNA stability of PAX6, NR2F6, and GAPDH mRNAs following 0.05 Gy irradiation for 6 h (b) or 12 h in HuR+/+ and -/- cells. Data represent the mean ± SD performed from N = 3 independent experiments. *: p < 0.05 from Student’s t-test. c) Viability of HuR+/+ and -/- cells upon 0.05 Gy irradiation at 6 days when PAX or NR2F6 was re-introduced. d) HuR KO, PAX6, or NR2F6 overexpression was confirmed using western blot analysis. Beta-actin was used as an endogenous control. Original blot images are presented in supplementary figure 3. Data represent the mean ± SD from N = 4 independent experiments. **: p < 0.01, ***: p < 0.001, ns: p > 0.05 from Student’s t-test. LDIR, low-dose ionizing radiation; HUR, human antigen R.

Figure 5.

LDIR destabilizes HuR-bound mRNAs to enhance cell viability. a, b) mRNA stability of PAX6, NR2F6, and GAPDH mRNAs following 0.05 Gy irradiation for 6 h (b) or 12 h in HuR+/+ and -/- cells. Data represent the mean ± SD performed from N = 3 independent experiments. *: p < 0.05 from Student’s t-test. c) Viability of HuR+/+ and -/- cells upon 0.05 Gy irradiation at 6 days when PAX or NR2F6 was re-introduced. d) HuR KO, PAX6, or NR2F6 overexpression was confirmed using western blot analysis. Beta-actin was used as an endogenous control. Original blot images are presented in supplementary figure 3. Data represent the mean ± SD from N = 4 independent experiments. **: p < 0.01, ***: p < 0.001, ns: p > 0.05 from Student’s t-test. LDIR, low-dose ionizing radiation; HUR, human antigen R.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).