1. Introduction

The rapid evolution of digital media platforms has fundamentally transformed content consumption patterns, particularly among younger generations who have grown up immersed in the digital ecosystem. The emergence of short-form video platforms such as TikTok and Instagram has introduced unprecedented changes in how individuals engage with digital content, creating new behavioral phenomena that challenge traditional understanding of media consumption and its psychological implications. These platforms have introduced novel consumption patterns including “binge-scrolling,” characterized by diminished self-control and temporal disorientation during rapid sequential video consumption (Park & Jung, 2024). The integration of infinite scroll mechanisms has intensified platform dependence, with users frequently exceeding intended usage durations while experiencing reduced cognitive engagement (Wang, 2023).

Contemporary digital consumption is particularly pronounced among Generation Alpha (born after 2010) and Generation Z (born 1995 to 2010), who represent a fundamental paradigm shift in digital media engagement. These cohorts are distinguished from previous generations by their status as true digital natives who integrate technology seamlessly into daily routines from early childhood (Dunas & Vartanov, 2020; Šramová & Pavelka, 2023). Unlike previous generations who engaged in more passive, scheduled media consumption, these cohorts demonstrate intentional, selective, and highly interactive engagement patterns, with a pronounced preference for mobile-first, on-demand content across platforms like TikTok and Instagram (Cifuentes-Ambra et al., 2023; Laor & Galily, 2022).

The scale of digital engagement among these generations has reached unprecedented levels, with profound implications for cognitive development and behavioral patterns. Screen time among Generation Alpha and Generation Z has escalated dramatically, with the average 17-19-year-old spending approximately 6 hours daily on mobile digital devices (Manwell et al., 2022). These digital natives demonstrate complex multitasking behaviors, frequently using smartphones as second screens while engaging with other media content (Yeşilyurt & Karaduman, 2025). Current research indicates that Generation Z students spend 9 hours or more per day on smartphones and social media, with 70% acknowledging internet addiction (Ahmed, 2019). While media consumption remained stable until 2010, it increased significantly by 2014, particularly among teenagers (Zdanowicz et al., 2020).

This excessive digital consumption has given rise to the culturally significant concept of “brain rot,” which has emerged as a metaphor for the perceived cognitive decline and mental exhaustion associated with overconsumption of low-quality digital content, particularly among younger generations (Özpençe, 2024; Yousef et al., 2025). Brain rot refers to the deterioration of mental or intellectual abilities due to overconsumption of trivial, repetitive, or low-value online content. This phenomenon represents growing societal concerns about how constant exposure to trivial online material can erode attention spans, critical thinking abilities, and emotional well-being in the digital age (Abdo & Pego-Fernandes, 2025; Sage, 2025). The cultural resonance of this term, exemplified by its designation as Oxford’s Word of the Year 2024, reflects widespread anxieties about technology’s impact on cognitive health and meaningful communication (Yazgan, 2025).

The concerns surrounding excessive digital consumption are increasingly supported by empirical research revealing significant neurobiological and cognitive consequences. Existing neuroscience research reveals concerning impacts of excessive digital stimulation on developing brains, with studies demonstrating significant cognitive, emotional, and behavioral consequences. Research indicates that prolonged screen exposure is associated with impaired learning and memory acquisition, reduced academic performance, and altered brain structure and function (Neophytou et al., 2019). Excessive digital media use correlates with increased rates of anxiety, depression, and behavioral problems in youth (Manwell et al., 2022), while chronic overuse can disrupt normal brain maturation processes, particularly in regions responsible for emotional regulation and executive function (Nivins et al., 2024; Small et al., 2022; Yousef et al., 2025).

The addictive potential of digital platforms is further explained by their strategic neurobiological targeting mechanisms. Social media platforms strategically employ intermittent reinforcement schedules through algorithmic delivery of unpredictable rewards such as likes, comments, and notifications, which potently activate the brain’s dopamine reward pathways (Lindström et al., 2021). These variable reinforcement patterns engage midbrain limbic dopamine systems, particularly through social prediction error mechanisms in the ventral tegmental area, where dopamine neurons encode differences between expected and received social rewards (Solié et al., 2021). The unpredictable nature of these social rewards creates heightened anticipation and reinforces repeated engagement behaviors, establishing patterns like those observed in substance addiction (De et al., 2025; Wang & Wang, 2025).

Concurrent with these neurobiological changes, digital devices are increasingly replacing traditional cognitive processes, leading to measurable neuroplastic changes in brain structure and function. The phenomenon of cognitive offloading, defined as the use of external tools or actions to reduce mental effort in memory tasks (Gilbert et al., 2016), has become particularly relevant. While this strategy enhances immediate task performance, particularly under high cognitive load conditions (Morrison & Richmond, 2020), research demonstrates complex long-term consequences for memory consolidation. Specifically, cognitive offloading can diminish memory retention for offloaded information—termed the “Google effect” unless individuals maintain explicit intentions to remember (Grinschgl et al., 2020).

Despite the growing recognition of these phenomena, current assessment tools remain inadequate for measuring contemporary digital consumption patterns. Current digital addiction and problematic internet use scales face significant limitations when applied to contemporary content consumption patterns, particularly those involving short-form, algorithm-driven platforms. Most existing scales require further validation work and demonstrate inconsistent psychometric properties across different populations and contexts (Omrawo et al., 2023; Tiego et al., 2019), while traditional measures were primarily developed and validated for adult populations, leaving gaps in assessment tools for younger demographics.

Existing measures fail to capture the unique aspects of short-form content overconsumption because they were designed for longer-form digital engagement rather than the rapid, repetitive consumption cycles characteristic of platforms like TikTok (Griffiths, 2021; Kokshagina et al., 2023; Omrawo et al., 2023; Pastor, 2025). The advanced algorithmic systems that personalize content delivery create uniquely addictive patterns that differ substantially from traditional social media addiction, yet there remains an absence of valid and specific psychometric tools to assess these emerging forms of digital addiction (Kokshagina et al., 2023; Pastor, 2025).

To address these critical gaps in assessment capabilities, this study aims to develop and validate the Brain Rot Scale (BRS), a new tool designed to assess digital content overconsumption patterns among Generation Alpha and Generation Z. The BRS aims to capture the unique characteristics of contemporary short-form, algorithm-driven content consumption behaviors that existing digital addiction measures fail to adequately assess. Through rigorous psychometric evaluation, the study aims to establish the BRS as a specialized tool for measuring the cognitive, behavioral, and emotional consequences of excessive consumption of low-quality digital content. This research aims to provide researchers, clinicians, and educators with an empirically-validated instrument to identify problematic digital consumption patterns among digital natives, addressing the critical gap in assessment tools for emerging forms of internet behavioral addiction.

1.1. Literature Review

1. Transformation of Digital Media Consumption Patterns

The emergence of short-form video platforms has fundamentally transformed media consumption patterns among digital natives, creating a paradigmatic shift from traditional passive, scheduled viewing to active, algorithm-driven engagement characterized by continuous scrolling behaviors. This transformation represents more than a simple technological evolution; it constitutes a complete restructuring of how individuals interact with digital content and process information. Research demonstrates that infinite scrolling mechanisms contribute to perceived loss of self-control and negative internal states, creating psychological experiences that users find difficult to regulate independently (Park & Jung, 2024). The behavioral patterns associated with these platforms are characterized by binge-scrolling behaviors that are driven by satisfaction and dependence on cognitive consumption values, establishing sustained engagement cycles that exceed users’ initial intentions and conscious awareness (Zhang et al., 2024). These consumption patterns generate significant data inefficiencies, with substantial mobile data allocated to unwatched content (Zhang et al., 2023), while fostering addictive behaviors that raise concerns about user well-being and sustainable digital media engagement (Szalkowski et al., 2025; Zhang et al., 2024). The technological architecture of contemporary platforms significantly impairs users’ capacity to retain behavioral intentions through constant context switching, creating cognitive disruption that undermines deliberate decision-making processes and goal-directed behavior (Chiossi et al., 2023). Research demonstrates that increased consumption of short-form content is linked to poor sustained attention capabilities, despite this relationship being independent of consumption duration, suggesting that the rapid switching nature of content rather than time spent is the critical factor in attention degradation (Lin et al., 2024). The continuous engagement facilitated by these platforms is further reinforced through flow experiences and cognitive lock-in mechanisms that maintain user attention through serendipitous content discovery, creating a perpetual cycle of consumption that becomes increasingly difficult to interrupt voluntarily (Yang et al., 2023).

2. Neurobiological Mechanisms of Digital Platform Addiction

The addictive potential of digital platforms is grounded in well-established neurobiological mechanisms that demonstrate remarkable similarities to traditional substance addiction pathways. Digital platform addiction shares fundamental neurobiological mechanisms with traditional substance addiction, particularly through dopamine-mediated reward pathways and striatal circuits underlying craving and compulsive behavior (Antons et al., 2020; Weinstein & Lejoyeux, 2020). Both addiction types demonstrate heightened activation in reward regions like the ventral tegmental area and nucleus accumbens, alongside reduced activity in executive control areas, impairing decision-making and inhibitory control mechanisms essential for self-regulation (Poisson et al., 2021). The strategic implementation of intermittent reinforcement schedules through unpredictable digital rewards creates particularly potent activation of dopamine systems, establishing powerful conditioning mechanisms that drive continued engagement beyond conscious intention. Intermittent reinforcement from unpredictable digital rewards potently activates dopamine systems, while social prediction errors in the ventral tegmental area drive platform engagement through unexpected social feedback delivered through sophisticated algorithmic systems (Mestre-Bach & Potenza, 2023). This neurobiological process underlies the compelling nature of social media use, as dopamine-mediated reward learning drives users to maximize social reward acquisition through continued platform engagement (Schultz, 2024). These neurobiological processes result in measurable neuroplastic changes that reflect the brain’s adaptation to digital engagement patterns. Neuroplastic changes, including reduced gray-matter volume and altered white-matter density, occur in both digital and substance addictions, though digital engagement uniquely affects sensory, motor, and cognitive processing regions (Dresp-Langley & Hutt, 2022). Research demonstrates that digital technology engagement produces structural modifications, including increased gray matter volume in frontal regions associated with goal achievement and deduction (Hongo et al., 2023), while virtual reality-based cognitive training enhances neural activity through increased alpha and beta EEG power (Gangemi et al., 2023). These neuroplastic adaptations reflect the brain’s dynamic reorganization of functional networks during human-machine interaction (Zhang et al., 2022), with gamified learning environments promoting cognitive enhancement and emotional regulation through network reorganization (Kumar et al., 2024).

3. Cognitive Offloading and Memory Consolidation Alterations

The phenomenon of cognitive offloading through digital devices has fundamentally altered memory consolidation processes and cognitive development patterns, particularly among Generation Alpha and Generation Z who have integrated digital systems into their cognitive architecture from early developmental stages. This transformation is exemplified by the well-documented “Google effect,” where individuals demonstrate significantly reduced retention for information they believe is reliably stored in external digital systems (Schooler & Storm, 2021). The decision-making process underlying cognitive offloading reflects sophisticated value-based metacognitive evaluation, where users continuously balance cognitive effort expenditure against perceived memory utility and accessibility (Gilbert, 2024). The decision to engage in cognitive offloading is primarily driven by metacognitive evaluations of memory confidence rather than actual memory ability, with individuals demonstrating value-based decision-making processes when balancing cognitive effort against memory retention needs (Gilbert, 2024; Hu et al., 2019). While cognitive offloading can enhance immediate task performance, particularly under high cognitive load conditions (Morrison & Richmond, 2020), and improve memory retention for non-offloaded information through “saving-enhanced memory” effects, excessive reliance on digital systems contributes to a phenomenon termed “digital dementia.” This condition is characterized by attention deficits, memory impairment, and structural brain changes that occur during critical developmental periods when cognitive architecture is still forming (Ali et al., 2024). Empirical research indicates that 84.5% of students actively utilize smartphones as external memory systems, with significant correlations observed between this reliance and increased rates of depression, anxiety, and reduced emotional intelligence (Mohan & Ponnusamy, 2023; Musa & Ishak, 2021). This cognitive-efficiency trade-off underscores the complex metacognitive processes underlying digital dependency decisions among younger generations and highlights the multifaceted nature of contemporary digital consumption patterns that extend beyond simple entertainment or communication purposes.

4. Assessment Limitations and Measurement Gaps

Current assessment methodologies for digital consumption patterns demonstrate significant limitations when applied to contemporary short-form, algorithm-driven content engagement behaviors. Existing digital addiction and problematic internet use scales face significant limitations when applied to contemporary content consumption patterns, particularly those involving short-form, algorithm-driven platforms that operate through fundamentally different engagement mechanisms than traditional digital media (Griffiths, 2021; Kokshagina et al., 2023; Omrawo et al., 2023; Pastor, 2025). Most existing scales require extensive additional validation work and demonstrate inconsistent psychometric properties across different populations and contexts, while traditional measures were primarily developed and validated for adult populations, leaving significant gaps in assessment tools specifically designed for younger demographics who represent the primary consumers of contemporary digital content (Omrawo et al., 2023; Tiego et al., 2019). The rapid, repetitive consumption cycles characteristic of platforms like TikTok differ substantially from the longer-form digital engagement patterns for which current assessment tools were originally designed and validated. The advanced algorithmic systems that personalize content delivery create uniquely addictive patterns that differ substantially from traditional social media addiction mechanisms, yet there remains an absence of valid and specific psychometric tools to assess these emerging forms of digital behavioral addiction (Kokshagina et al., 2023; Pastor, 2025). Short video addiction represents an emerging form of internet behavioral addiction characterized by dependent and excessive use patterns that significantly affect decision-making processes, necessitating specialized measurement instruments that can accurately capture these contemporary digital consumption behaviors among Generation Alpha and Generation Z.

Neurobiological research, cognitive psychology, and cultural recognition of digital overconsumption phenomena have led to the development of specialized assessment tools. The “brain rot” phenomenon, characterized by cognitive decline and mental exhaustion from low-quality digital content, has gained attention due to its cultural resonance. This highlight concerns technology’s impact on cognitive health and meaningful communication, especially among younger generations who engage with algorithm-driven platforms. The lack of empirically validated assessment tools is a significant limitation in research and clinical practice.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

This study employed a two-phase design utilizing separate samples for exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to ensure robust psychometric validation of the Brain Rot Scale. The EFA sample comprised 403 Egyptian participants ranging in age from 8 to 24 years (M = 15.014, SD = 4.66), while the CFA sample consisted of 897 Egyptian participants within the same age range (M = 17.035, SD = 3.954). Both samples were specifically selected to represent Generation Alpha (born after 2010) and Generation Z (born 1995-2010) populations, which constitute the primary target demographic for assessing digital content overconsumption behaviors. The demographic characteristics of both samples are presented in

Table 1.

Table 1 shows that gender distribution is balanced, with males comprising 50.9% of the EFA sample and 53.0% of the CFA sample. Rural residents are predominant, accounting for 72.7% of the EFA sample and 72.0% of the CFA sample. Educational attainment varies between the samples, with primary school students being the largest group. Mobile phones are the predominant platform for digital content consumption, used by 66.0% of EFA participants and 63.9% of CFA participants. Multiple device usage is reported by 19.4% of EFA participants and 17.6% of CFA participants, while tablets, laptops, and computers show lower usage frequencies.

2.2. Instrument Development

The Brain Rot Scale (BRS) was developed to address the critical gap in psychometric instruments capable of assessing contemporary digital content overconsumption patterns among Generation Alpha and Generation Z. The initial instrument comprised 21 items specifically designed to capture the cognitive, behavioral, and emotional consequences associated with excessive consumption of low-quality digital content, particularly the short-form, algorithm-driven content characteristic of platforms. The scale prioritizes digital natives’ unique consumption behaviors.

The original scale was developed in Arabic for cultural and linguistic suitability, using a 5 point Likert format to measure digital content consumption behaviors. Subsequently, the instrument underwent professional translation into English by specialized translators with expertise in psychological assessment tools. The translation process employed forward and backward translation procedures to maintain semantic equivalence and conceptual integrity across languages. Content validity was established through expert review by specialists in educational psychology, clinical psychology, and mental health, who evaluated each item for relevance, clarity, and alignment with digital content overconsumption. Expert feedback was used to refine wording and ensure comprehensive coverage of the phenomenon.

2.3. Procedure

Data collection was conducted using digital survey platforms to effectively reach the target demographic of Generation Alpha and Generation Z participants. The recruitment strategy employed convenience sampling methods appropriate for accessing populations with high digital engagement. Participants were recruited through various digital channels, including social media platforms and educational institutions, to ensure diverse representation within the specified age range. The survey administration protocol was designed to minimize participant burden while ensuring comprehensive data collection for robust psychometric analysis.

The survey protocol included completion of the BRS items alongside demographic questionnaires capturing relevant participant characteristics. Demographic variables included age, gender, residence type (urban/rural), educational level, and primary device type used for digital content consumption. The inclusion of device type information was particularly important given the platform-specific nature of digital content overconsumption behaviors. Data collection was conducted in controlled conditions to minimize external influences on participant responses, with clear instructions provided for scale completion.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The study used SPSS version 27 and AMOS version 26, following established psychometric validation procedures for scale development research. A sequential two-phase design was used, starting with exploratory factor analysis on the first sample to identify the underlying factor structure of the BRS. The factorability of the correlation matrix was assessed using the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy and Bartlett’s test of sphericity. Principal component analysis with varimax rotation was employed to extract factors with eigenvalues greater than 1.0, ensuring clear factor differentiation. Items with factor loadings below 0.40 or substantial cross-loadings exceeding 0.30 were considered for removal.

Confirmatory factor analysis was subsequently conducted on the independent CFA sample to test the factor structure identified through exploratory procedures. Maximum likelihood estimation was utilized to evaluate model parameters and assess overall model fit. Multiple goodness-of-fit indices were examined to provide comprehensive evaluation of model adequacy, including the chi-square goodness-of-fit test, Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), and Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI). Acceptable model fit was defined according to established psychometric criteria: CFI and TLI values ≥ 0.90, RMSEA values ≤ 0.08, and GFI values ≥ 0.90.

The reliability assessment of a scale was conducted using internal consistency indices, Cronbach’s alpha, McDonald’s omega, and Guttman’s lambda coefficients. Composite reliability and average variance extracted were used to assess convergent validity, with values ≥ 0.70 and AVE ≥ 0.50 indicating adequate validity. Item-total correlations were used to evaluate individual items’ contribution to overall scale reliability and identify problematic items. Construct validity was assessed through factor loadings, inter-factor correlations, and overall model fit indices. All statistical analyses were conducted with α = 0.05 as the criterion for statistical significance.

3. Results

The factorability of the correlation matrix was assessed prior to conducting exploratory factor analysis. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy was .891, exceeding the recommended threshold of .70, indicating that the data were appropriate for factor analysis. Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (χ2 = 1898.193, df = 210, p < .001), confirming that correlations among items were sufficient for factor analysis.

Principal component analysis with varimax rotation was conducted on the 21 initial items. The analysis revealed three factors with eigenvalues greater than 1.0, which collectively explained 39.673% of the total variance. Factor 1 accounted for 26.736% of the variance, Factor 2 explained 6.588%, and Factor 3 contributed 6.349% of the variance. Items with factor loadings below .40 or substantial cross-loadings exceeding .30 were removed, resulting in a final 17-item scale (BRS-17).

The rotated component matrix revealed a clear three-factor structure (

Table 2). Factor 1, labeled “Attention Dysregulation,” comprised 7 items (loadings ranging from .517 to .651) that captured difficulties with sustained attention, focus maintenance, and cognitive control in digital environments. Factor 2, “Digital Compulsivity,” included 6 items (loadings from .452 to .732) reflecting compulsive checking behaviors, failed attempts at screen time reduction, and immediate response to digital notifications. Factor 3, “Cognitive Dependency,” contained 5 items (loadings from .461 to .700) measuring reliance on digital devices for basic cognitive functions and information storage.

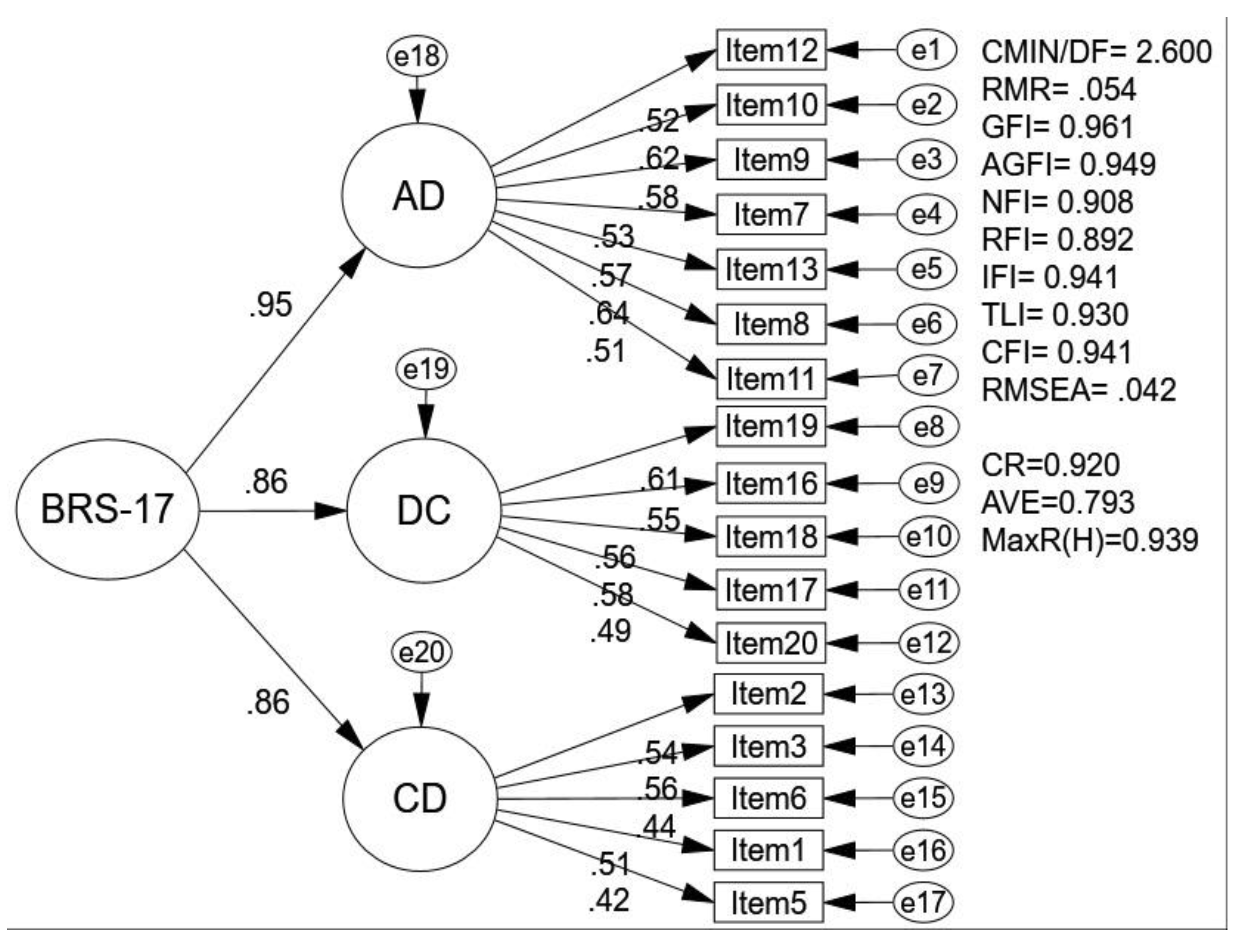

The three-factor structure identified through EFA was tested using confirmatory factor analysis on the independent CFA sample (n = 897). Maximum likelihood estimation was employed to evaluate the proposed model. The CFA results supported the three-factor structure of the BRS-17, with all factor loadings being statistically significant and ranging from .42 to .78.

Multiple goodness-of-fit indices were examined to assess model adequacy (

Figure 1). The chi-square test was significant (χ

2 = 301.630, df = 116, p < .001), which is common in large samples. The chi-square to degrees of freedom ratio (CMIN/DF = 2.600) was within acceptable limits (< 3.0). The Comparative Fit Index (CFI = .941) and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI = .930) both exceeded the recommended threshold of .90, indicating good model fit. The Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA = .042, 90% CI [.036, .048]) was below the acceptable threshold of .08, with a PCLOSE value of .985, suggesting close fit. The Goodness of Fit Index (GFI = .961) and Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI = .949) also demonstrated acceptable model fit.

Internal consistency reliability was assessed using multiple coefficients to provide comprehensive evaluation of scale reliability. The overall BRS-17 demonstrated excellent internal consistency, with McDonald’s omega (ω = .853), Cronbach’s alpha (α = .852), and Guttman’s lambda-2 (λ2 = .854) all exceeding the recommended threshold of .70. The average inter-item correlation (.254) fell within the optimal range of .15-.50, indicating appropriate item homogeneity without redundancy.

Inter-factor correlations were examined to assess discriminant validity among the three factors. All correlations were statistically significant (p < .01) and ranged from moderate to strong (

Table 3). Attention Dysregulation correlated .597 with Digital Compulsivity and .565 with Cognitive Dependency. Digital Compulsivity showed a correlation of .487 with Cognitive Dependency. These correlations suggest that while the factors are related, they represent distinct aspects of digital content overconsumption, supporting the multidimensional nature of the construction.

Convergent validity was evaluated through composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE). The overall scale demonstrated strong convergent validity with CR = .920 (> .70) and AVE = .793 (> .50), indicating that the factors adequately explain the variance in their respective indicators. The maximum reliability coefficient (MaxR(H) = .939) further supported the scale’s reliability.

The BRS-17 demonstrated robust psychometric properties across both exploration and confirmatory analyses. The three-factor structure (Attention Dysregulation, Digital Compulsivity, and Cognitive Dependency) was psychometrically sound and theoretically meaningful. The scale showed excellent internal consistency, adequate model fit indices, and strong evidence for construct validity. These findings support the BRS-17 as a reliable and valid instrument for assessing digital content overconsumption among Generation Alpha and Generation Z populations.

4. Discussion

The development and validation of the Brain Rot Scale (BRS-17) represents a significant advancement in the assessment of digital content overconsumption among Generation Alpha and Generation Z. The rigorous psychometric evaluation conducted across two independent samples demonstrates that the BRS-17 is a reliable and valid instrument capable of capturing the unique characteristics of contemporary digital media consumption behaviors that existing measures have failed to adequately assess (Omrawo et al., 2023; Griffiths, 2021; Kokshagina et al., 2023).

The three-factor structure that emerged from our analyses—Attention Dysregulation, Digital Compulsivity, and Cognitive Dependency—provides a comprehensive framework for understanding the multidimensional nature of digital content overconsumption. This structure aligns with theoretical conceptualizations of problematic digital media use while addressing the specific cognitive, behavioral, and emotional consequences associated with excessive consumption of short-form, algorithm-driven content.

The Attention Dysregulation factor captures the fundamental cognitive disruptions that characterize brain rot phenomena. The items loading on this factor reflect difficulties with sustained attention, focus maintenance, and cognitive control that are increasingly prevalent among digital natives. These findings are consistent with neuroscience research demonstrating that excessive digital stimulation can impair learning and memory acquisition while altering brain structure and function, particularly in regions responsible for executive function (Neophytou et al., 2019; Nivins et al., 2024; Small et al., 2022). The emergence of attention dysregulation as a distinct factor supports growing concerns about how constant exposure to rapid-fire digital content may be eroding cognitive capacities essential for deep learning and meaningful engagement with complex information (Yousef et al., 2025; Sage, 2025).

Digital Compulsivity, as the second factor, encompasses the behavioral manifestations of problematic digital engagement, including compulsive checking behaviors, failed attempts at screen time reduction, and immediate responsiveness to digital notifications. This dimension reflects the neurobiological processes underlying social media addiction, where platforms strategically employ intermittent reinforcement schedules through algorithmic delivery of unpredictable rewards (Lindström et al., 2021). The factor structure validates concerns about how these variable reinforcement patterns engage midbrain limbic dopamine systems, creating patterns like those observed in substance addiction (De et al., 2025; Solié et al., 2021; Wang & Wang, 2025;). The identification of phantom vibration syndrome as a component of digital compulsivity particularly underscores the extent to which digital dependency has become embodied in users’ sensory experiences.

The Cognitive Dependency factor addresses perhaps the most concerning aspect of brain rot: the replacement of traditional cognitive processes with digital alternatives. Items loading on this factor reveal how users increasingly rely on external digital sources for basic cognitive functions, from memory storage to navigation and information retrieval. This finding resonates with research on cognitive offloading, where the use of external tools reduces mental effort but potentially diminishes memory retention for offloaded information—termed the “Google effect” (Gilbert et al., 2016; Grinschgl et al., 2020). The emergence of cognitive dependency as a distinct factor suggests that digital content overconsumption may be fundamentally altering how individuals process, store, and retrieve information, with implications for cognitive autonomy and intellectual development (Gilbert, 2024; Morrison & Richmond, 2020).

The strong inter-factor correlations observed in our study indicate that these three dimensions, while distinct, are interconnected aspects of a broader phenomenon. This interconnectedness suggests that digital content overconsumption operates as a systemic issue affecting multiple cognitive and behavioral domains simultaneously. The moderate to strong correlations between factors support the conceptualization of brain rot as a multidimensional construct while maintaining the utility of examining its component dimensions separately.

The excellent psychometric properties of the BRS-17, including high internal consistency reliability and strong model fit indices, establish confidence in the instrument’s measurement precision. The scale’s convergent validity, demonstrated through appropriate composite reliability and average variance extracted values, confirms that the factors adequately capture their intended constructs. These psychometric strengths are particularly important given the novelty of the brain rot construct and the need for precise measurement tools in this emerging area of research.

The cultural and linguistic development of the BRS-17 in Arabic, with subsequent professional translation to English, addresses important considerations of cultural validity in psychological assessment. The successful validation across these linguistic contexts suggests that brain rot phenomena transcend cultural boundaries, reflecting universal concerns about digital technology’s impact on cognitive functioning. This cross-linguistic validity enhances the potential for international research collaboration and comparative studies across different cultural contexts.

The demographic characteristics of our samples, particularly the predominance of rural participants and the diversity of educational levels, strengthen the generalizability of our findings beyond urban, highly educated populations. The prevalence of mobile phone usage among participants aligns with global trends in digital media consumption and ensures that our instrument captures behaviors relevant to the primary platforms where brain rot phenomena occur.

However, several limitations must be acknowledged. The cross-sectional design of our study precludes conclusions about causality or the developmental trajectory of brain rot symptoms. Future longitudinal research is needed to examine how digital content overconsumption patterns evolve over time and their long-term consequences for cognitive development. Additionally, while our sample included Generation Alpha and Generation Z participants, the relative representation of these cohorts varied, potentially limiting specific conclusions about generational differences in brain rot manifestations.

The reliance on self-report measures, while appropriate for initial scale development, introduces potential biases related to social desirability and introspective accuracy. Future research should incorporate objective measures of digital usage patterns, cognitive performance assessments, and neuroimaging techniques to provide convergent validation of self-reported brain rot symptoms. The integration of ecological momentary assessment methods could also enhance understanding of how brain rot symptoms manifest in real-world contexts.

The clinical and educational implications of BRS-17 are substantial. For clinicians, the scale provides a standardized tool for identifying problematic digital consumption patterns that may require intervention. The multidimensional structure allows for targeted assessment of specific problem areas, informing personalized treatment approaches. Educators can utilize the BRS-17 to identify students at risk for digital-related cognitive difficulties and implement appropriate support strategies.

From a research perspective, the BRS-17 opens new avenues for investigating the mechanisms underlying digital content overconsumption and its consequences. Future studies should examine the relationships between BRS-17 scores and objective cognitive performance measures, academic achievement, and mental health outcomes. Cross-cultural validation studies would enhance understanding of how brain rot phenomena manifest across different societies and technological contexts.

The development of intervention strategies targeting the specific dimensions identified in the BRS-17 represents another crucial research direction. Attention training programs, digital wellness interventions, and cognitive rehabilitation approaches could be evaluated using the BRS-17 as an outcome measure. The scale’s sensitivity to change over time should be established through longitudinal intervention studies.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the Brain Rot Scale (BRS-17) fills a critical gap in the assessment of contemporary digital content overconsumption behaviors among digital natives. Its robust psychometric properties, theoretically grounded factor structure, and practical utility make it a valuable tool for researchers, clinicians, and educators concerned with the cognitive implications of our increasingly digital world. As digital technologies continue to evolve and permeate daily life, instruments like the BRS-17 will be essential for monitoring and addressing their impact on human cognitive functioning and well-being.

Author Contributions

M.M. & M.H.: conceptualization. A.H. & S.A.: literature review. A.I.: methodology, data analysis. M.N.: review-editing and writing, original manuscript preparation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Deanship of Scientific Research at King Faisal University for providing the research fund for publishing research [Grant KFU252401].

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Education at Al-Azhar University, Dakahlia, Egypt. “The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Faculty of Education at Al-Azhar University, Dakahlia, Egypt (Ref. No. EDU-REC-2025-038).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The researchers would like to thank the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Faisal University for providing the research fund for publishing research [Grant KFU252401].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BRS |

Brain Rot Scale |

| CFA |

confirmatory factor analysis |

| EFA |

exploratory factor analysis |

References

- Abdo, C.; Pego-Fernandes, P. Hostages to Social Networks and Mental Health. São Paulo Medical Journal 2025, 143, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, N. Generation Z’s smartphone and social media usage: A survey. Journalism and mass communication 2019, 9(3), 101–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Z.; Janarthanan, J.; Mohan, P. Understanding digital dementia and cognitive impact in the current era of the internet: A review. Cureus 2024, 16(9), e70029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antons, S.; Brand, M.; Potenza, M. Neurobiology of cue-reactivity, craving, and inhibitory control in non-substance addictive behaviors. Journal of the Neurological Sciences 2020, 415, 116952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiossi, F.; Haliburton, L.; Ou, C.; Butz, A. M.; Schmidt, A. Short-form videos degrade our capacity to retain intentions: Effect of context switching on prospective memory. In Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; Article 30. Association for Computing Machinery, 2023; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cifuentes-Ambra, C.; Samacá-Salamanca, E.; Martínez-Estrella, E.; García-Rivero, A. Generation Z in Chile, Colombia, México, and Panama: Interests and new digital consumption habits. Their use of Instagram and TikTok. El Profesional de la información 2023, 32(2), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De, D.; El Jamal, M.; Aydemir, E.; Khera, A. Social Media Algorithms and Teen Addiction: Neurophysiological Impact and Ethical Considerations. Cureus 2025, 17(1), e77145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dresp-Langley, B.; Hutt, A. Digital addiction and sleep. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19(11), 6910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drigas, A.; Sideraki, A. Brain neuroplasticity leveraging virtual reality and brain–computer interface technologies. Sensors 2024, 24(17), 5725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunas, D.; Vartanov, S. Emerging digital media culture in Russia: modeling the media consumption of Generation Z. Journal of Multicultural Discourses 2020, 15(2), 186–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangemi, A.; De Luca, R.; Fabio, R. A.; Lauria, P.; Rifici, C.; Pollicino, P.; Marra, A.; Olivo, A.; Quartarone, A.; Calabrò, R. S. Effects of virtual reality cognitive training on neuroplasticity: A quasi-randomized clinical trial in patients with stroke. Biomedicines 2023, 11(12), 3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, S. J. Cognitive offloading is value-based decision making: Modelling cognitive effort and the expected value of memory. Cognition 247 2024, 105783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, M. D. Internet use disorders: What’s new and what’s not? Journal of Behavioral Addictions 2021, 9(4), 934–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinschgl, S.; Papenmeier, F.; Meyerhoff, H. S. Consequences of cognitive offloading: Boosting performance but diminishing memory. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology 2021, 74(9), 1477–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hongo, T.; Yakou, T.; Yoshinaga, K.; Kano, T.; Miyazaki, M.; Hanakawa, T. Structural neuroplasticity in computer programming beginners. Cerebral Cortex 2023, 33(9), 5375–5381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Luo, L.; Fleming, S. M. A role for metamemory in cognitive offloading. Cognition 2019, 193, 104012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokshagina, O.; Reinecke, P. C.; Karanasios, S. To regulate or not to regulate: Unravelling institutional tussles around the regulation of algorithmic control of digital platforms. Journal of Information Technology 2023, 38(2), 160–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Sharma, T.; Varghese, S. S.; Mishra, A. Neuroplasticity and cognitive enhancement through gamified learning: Psychological and neurophysiological perspectives. International Journal of Future Multidisciplinary Research 2024, 6(6), 33016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laor, T.; Galily, Y. Who’S Clicking on On-Demand? Media Consumption Patterns of Generations Y & Z. Technology in Society 70 2022, 102016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.-H.; Chung, Y.-J.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Yen, Y.-T.; Li, C.-C.; Cherng, F.-Y. Understanding the effects of short-form videos on sustained attention. Extended Abstracts of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; Article 352. Association for Computing Machinery, 2024; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindström, B.; Bellander, M.; Schultner, D. T.; Chang, A.; Tobler, P. N.; Amodio, D. M. A computational reward learning account of social media engagement. Nature Communications 2021, 12, 1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manwell, L.; Tadros, M.; Ciccarelli, T.; Eikelboom, R. Digital dementia in the internet generation: excessive screen time during brain development will increase the risk of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias in adulthood. Journal of integrative neuroscience 2022, 21(1), 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestre-Bach, G.; Potenza, M. N. Neural mechanisms linked to treatment outcomes and recovery in substance-related and addictive disorders. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience 2023, 25(1), 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, S.; Ponnusamy, P. A comparative study on the cognitive functions and psychological factors associated with Google effect among college students. International Journal of Indian Psychology 2023, 11(4), 1481–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moody, T.; Gaddipati, H.; Siddarth, P.; Small, G.; Lee, J.; Bookheimer, S.; Jalil, J.; Kaufman, A. Brain health consequences of digital technology use. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience 2020, 22(2), 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, A. B.; Richmond, L. L. Offloading items from memory: Individual differences in cognitive offloading in a short-term memory task. Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications 2020, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, N.; Ishak, M. S. The phenomenon of Google effect, digital amnesia and nomophobia in academic perspective. Cyberspace: Jurnal Pendidikan Teknologi Informasi 2021, 5(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemirovskaya, E. Generation Z media consumption practices in social media. Сoциoдинамика 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neophytou, E.; Manwell, L. A.; Eikelboom, R. Effects of excessive screen time on neurodevelopment, learning, memory, mental health, and neurodegeneration: A scoping review. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction 2019, 19(3), 724–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nivins, S.; Sauce, B.; Liebherr, M.; Judd, N.; Klingberg, T. Long-term impact of digital media on brain development in children. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 13030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omrawo, C.; Ioannidis, K.; Grant, J. E.; Lutz, N.; Chamberlain, S. R.; Stein, D. J.; Tiego, J.; Kidd, M.; Lochner, C. A cross-national validation of the Internet Severity and Activities Addiction Questionnaire (ISAAQ). Comprehensive Psychiatry 122 2023, 152378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özpençe, A. Brain rot: Overconsumption of online content (An essay on the publicness social media). Journal of Business Innovation and Governance 2024, 7(2), 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Jung, Y. Unveiling the dynamics of binge-scrolling: A comprehensive analysis of short-form video consumption using a Stimulus-Organism-Response model. Telematics Informatics 2024, 95, 102200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor, J. J. Artificial intelligence applied by very large online platforms and search engines to mitigate systemic online risks. Cuadernos de Derecho Transnacional 2025, 17(1), 308–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poisson, C. L.; Engel, L.; Saunders, B. T. Dopamine circuit mechanisms of addiction-like behaviors. Frontiers in Neural Circuits 2021, 15, 752420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sage, R. Stop brain rot! Why we must give narrative language priority. Journal of Research in Education and Pedagogy 2025, 2(2), 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schooler, J. N.; Storm, B. C. Saved information is remembered less well than deleted information, if the saving process is perceived as reliable. Memory 2021, 29(9), 1101–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, W. A dopamine mechanism for reward maximization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2024, 121(20), e2316658121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Small, G. W.; Lee, J.; Kaufman, A.; Jalil, J.; Siddarth, P.; Gaddipati, H.; Moody, T. D.; Bookheimer, S. Y. Brain health consequences of digital technology use. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience 2022, 22(2), 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solié, C.; Girard, B.; Righetti, B.; Tapparel, M.; Bellone, C. VTA dopamine neuron activity encodes social interaction and promotes reinforcement learning through social prediction error. Nature Neuroscience 25 2022, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šramová, B.; Pavelka, J. Generation Alpha Media Consumption During Covid-19 and Teachers’ Standpoint. Media and Communication 2023, 11(4), 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szalkowski, G. A.; Windekilde, I. M.; Johansen, C. Towards sustainable short-form video: Modelling solutions for social and environmental challenges. F1000Research 2025, 14, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiego, J.; Lochner, C.; Ioannidis, K.; Brand, M.; Stein, D. J.; Yücel, M.; Grant, J. E.; Chamberlain, S. R. Problematic use of the Internet is a unidimensional quasi-trait with impulsive and compulsive subtypes. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Wang, S. The emotional reinforcement mechanism of and phased intervention strategies for social media addiction. Behavioral Sciences 2025, 15(5), 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Research on the User Experience of Infinite Up-scrolling on Chinese Short Video Software Douyin. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media 2023, 4, 954–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, A.; Lejoyeux, M. Neurobiological mechanisms underlying internet gaming disorder. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience 2020, 22(2), 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zhang, S.; Diao, Z.; Sun, D. What motivates users to continue using current short video applications? A dual-path examination of flow experience and cognitive lock-in. Telematics and Informatics 85 2023, 102050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazgan, A. The problem of the century: Brain rot. OPUS Journal of Society Research 2025, 22(2), 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeşilyurt, A.; Karaduman, S. Current cases of and motivations for second screen use by generation Z: university students. Atlantic Journal of Communication 2025, 33(2), 198–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousef, A.; Alshamy, A.; Tlili, A.; Metwally, A. Demystifying the new dilemma of brain rot in the digital era: A review. Brain Sciences 2025, 15(3), 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zdanowicz, N.; Reynaert, C.; Jacques, D.; Lepiece, B.; Dubois, T. Screen Time and (Belgian) Teenagers. Psychiatria Danubina 2020, 32 Suppl 1, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Yu, H.; Han, R.; Li, F.; Li, H. DUASVS: A mobile data saving strategy in short-form video streaming. IEEE Transactions on Services Computing 2023, 16(2), 1066–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Ariffin, S. Keep scrolling: An investigation of short video users’ continuous watching behavior. Information and Management 2024, 61(6), 104014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, W.; Lu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Study on the diversity of mental states and neuroplasticity of the brain during human-machine interaction. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2022, 16, 921058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).