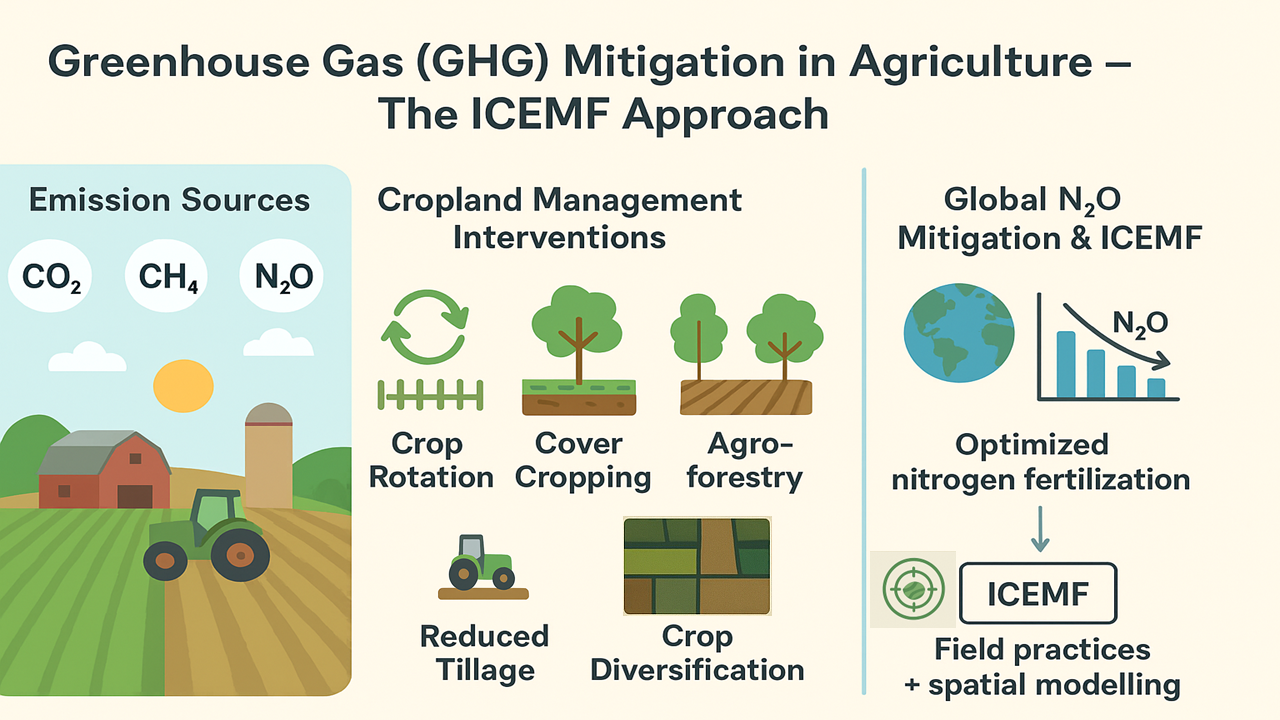

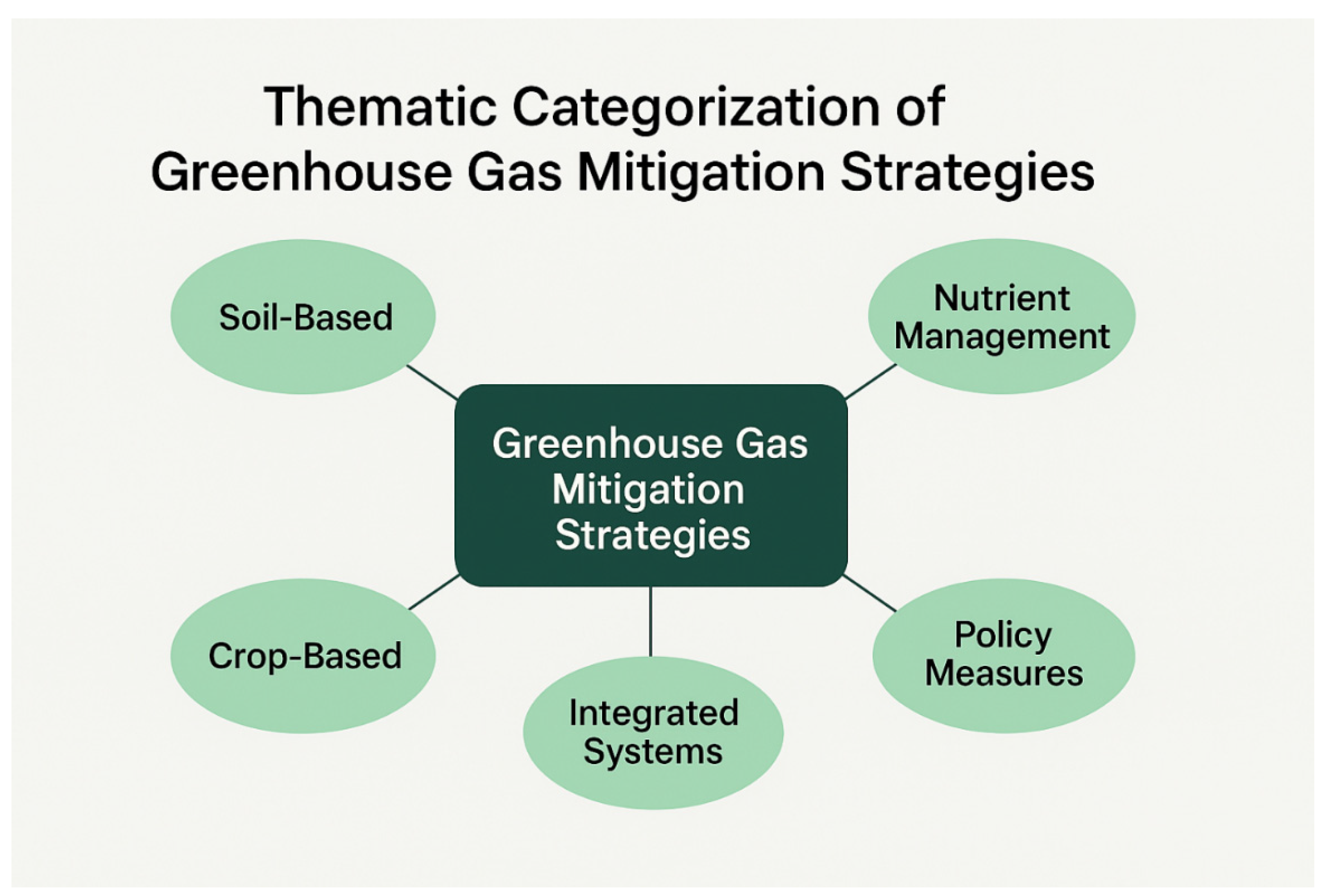

Figure 2 shows thematic analysis of the reviewed literature reveals that mitigation strategies in agricultural crop systems can be broadly grouped into five categories: soil-based approaches (e.g., biochar application, conservation tillage), crop-based practices (e.g., diversification, agroforestry, cover cropping), nutrient management (e.g., precision fertilization, 4R stewardship), integrated systems (e.g., crop–livestock recoupling, constructed wetlands), and policy or socio-economic interventions (e.g., carbon trading, CSA policies). This categorization highlights both the diversity and interconnectedness of approaches, with many practices offering co-benefits such as enhanced soil health, improved productivity, and resilience to climate variability. However, adoption remains uneven, and their effectiveness is often context-specific, emphasizing the need for adaptive frameworks like the ICEMF to harmonize local practices with global climate targets.

3.1. Sources and Trends of Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Agriculture

Agricultural systems contribute significantly to global GHG emissions, primarily through CO₂, CH₄, and N₂O [

66]. Soil organic matter degradation, excessive fertilizer use, and land-use change release CO₂, while enteric fermentation and flooded rice fields are major sources of CH₄, N₂O arises mainly from nitrogen fertilizer application and manure management, with its high global warming potential making it a critical focus for mitigation [

67]. Recent studies indicate that global agricultural emissions have steadily increased over the past decades, with hotspots in Asia, Latin America, and Sub-Saharan Africa driven by crop intensification and rising fertilizer demand [

68,

69]. Seasonal variations, cropping intensity, and irrigation practices further influence emission patterns, underlining the complexity of agricultural GHG dynamics [

70,

71].

The study by Akram and Ali [

72] examines the convergence hypothesis of GHG emissions across 93 countries from 1980 to 2017. Using the Phillips and Sul test, the study finds evidence of divergence in emissions trends, suggesting that countries follow different convergence paths. Clustering algorithms identify five distinct convergence clubs, indicating the need for region-specific policies.

Figure 3 present the Greenhouse gas emissions in the agriculture sector across 93 Countries (1980-2017), as a group, based on the Phillips and Sul Panel Club Convergence Test. The findings emphasize the importance of considering these divergent paths when designing GHG mitigation strategies and the impact of policy transfers across countries. The study suggests that countries in Clubs 1– 4 should adopt agricultural policies from Club 5, where GHG emissions are lower, particularly focusing on cleaner energy. Strategies to reduce GHG emissions include improving sector efficiency, fostering innovation, reducing deforestation, and using cleaner energy with subsidies. Additionally, addressing poverty and adopting low-cost energy technologies in agriculture are key to sustainable development in lower- and middle-income countries.

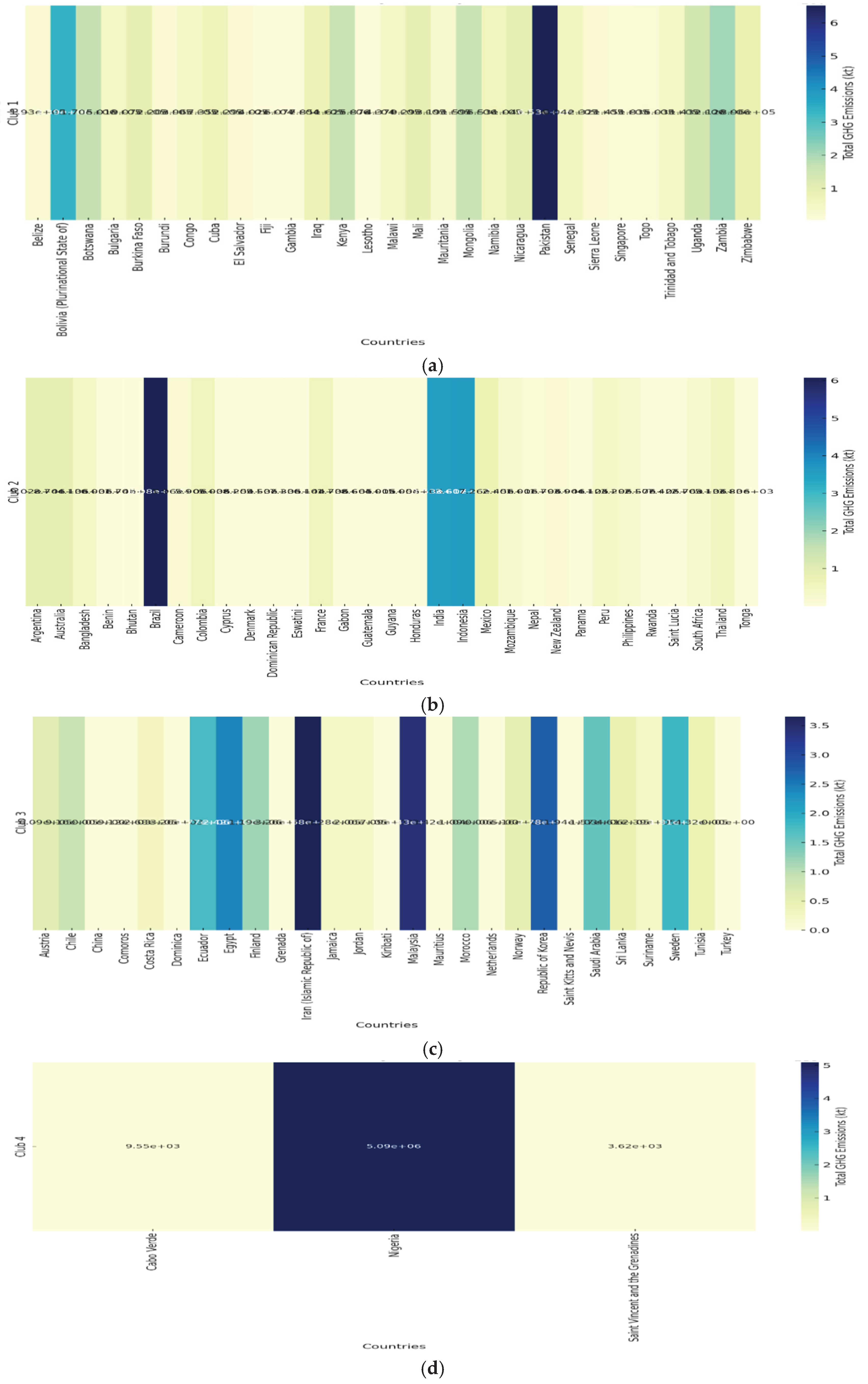

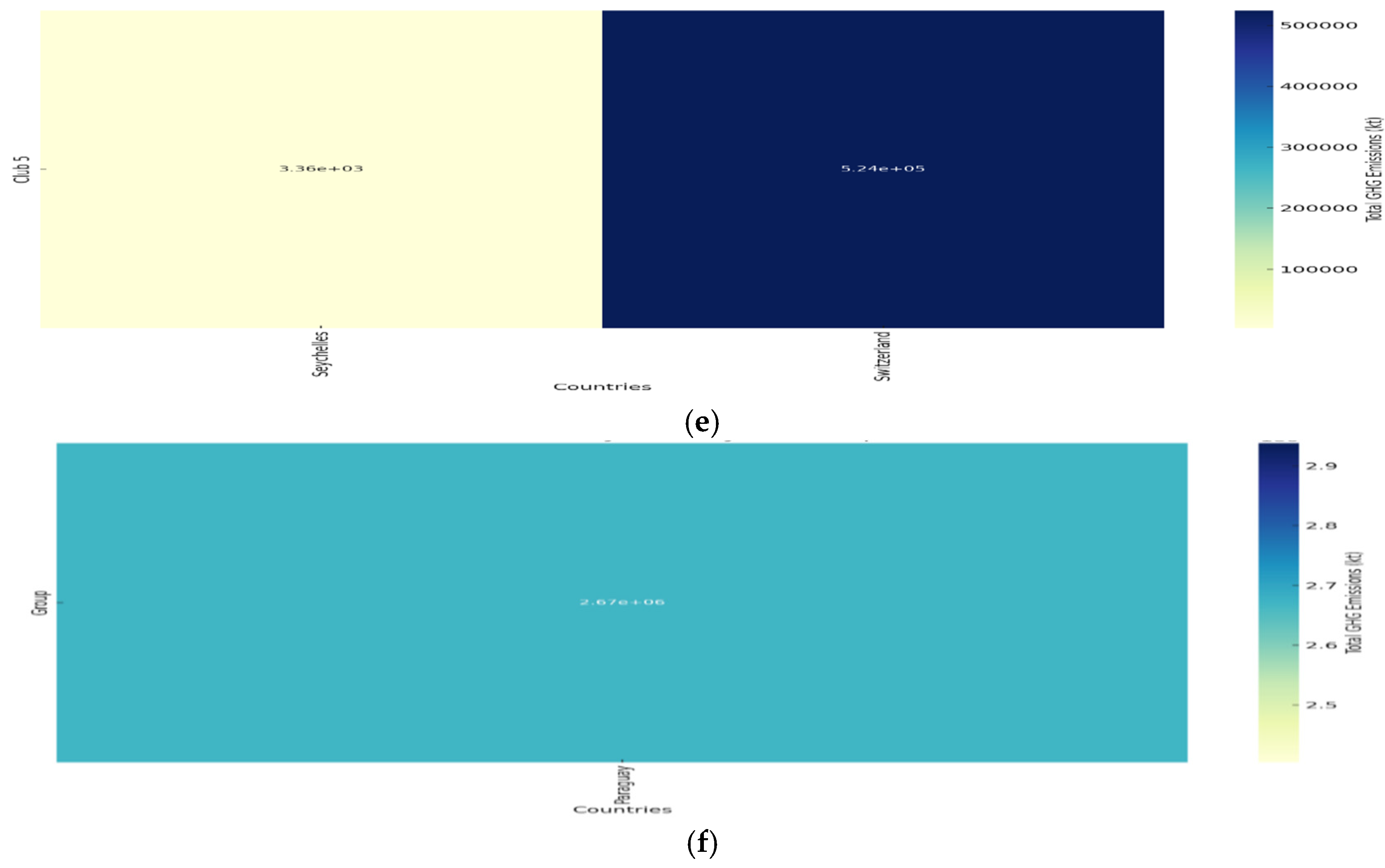

Building on the study by Akram and Ali (2021)[

72], which examines the convergence hypothesis of GHG emissions across 93 countries from 1980 to 2017, we have generated heatmaps for each of the identified convergence clubs, showing total emissions from 1990 to 2020. The heatmaps visually represent the emissions trends within each club, highlighting the divergent paths observed in the study. These visualizations support the need for region-specific GHG mitigation strategies, emphasizing the importance of targeted policies that reflect the unique emission patterns of each club. The findings underscore the role of tailored interventions to address the emissions disparities across countries. The data for these heatmaps is sourced from the FAOSTAT Database (FAO, 2020).

Figure 4 presents heatmaps illustrating the total greenhouse gas emissions (in kilotons) across five regional convergence clubs, as identified through the Phillips and Sul convergence test [

72]. These heatmaps visually represent emissions trends from 1990 to 2020, highlighting the disparities in emission patterns across regions. This regional analysis underscores the need for context-specific mitigation strategies and informs the ICEMF framework by emphasizing the importance of spatially explicit emission modeling.

Mukwada, Taylor [

73] reported that the trends also reveal significant regional disparities. Developed countries have shown modest declines in emissions due to improved nutrient-use efficiency, conservation tillage, and climate-smart practices, while developing nations continue to face steep increases as agricultural expansion meets food security demands. Studies highlight that rice and maize systems dominate CH₄ and N₂O contributions, respectively, while wheat and soybean systems contribute substantial CO₂ through soil and land-use related emissions [

74]. Moreover, climate change feedback loops, including rising temperatures and extreme weather events, exacerbate emission rates and reduce the mitigation capacity of soils [

75]. Although progress has been made in quantifying emissions, gaps remain in capturing indirect sources such as post-harvest processes and regional variability in emission factors, emphasizing the need for refined monitoring frameworks and targeted interventions [

76].

Table 2 presents a summary of key studies highlighting the sources and trends of greenhouse gas emissions in agriculture, their drivers, and regional or system-specific notes.

3.2. Evaluation of Crop and Soil Management Practices

Crop and soil management practices are central to reducing GHG emissions from agriculture. Conservation tillage, cover cropping, and crop diversification have been shown to enhance soil organic carbon stocks and reduce CO₂ release by minimizing soil disturbance and improving residue retention [

77]. Agroforestry systems contribute to long-term carbon sequestration while also providing ecosystem services such as biodiversity support and microclimate regulation [

78]. Biochar application has emerged as a promising soil amendment, capable of enhancing soil structure, microbial activity, and long-term carbon storage while mitigating CH₄ and N₂O fluxes [

79]. In temperate agricultural regions, biochar demonstrates substantially more consistent and predictable soil CO

2 emissions mitigation effects compared to no-till agriculture, which exhibits high climate and soil-dependent variability [

80]. Biochar application increases soil organic carbon sequestration by 61% across temperate zones [

80], with moderate confidence intervals between 36 - 90%, and decreases annual CO

2 emissions by 13.0–17.6% within 1–2 years [

81], whereas no-till effectiveness in temperate regions depends critically on soil texture, organic carbon content, and precipitation patterns [

82], with future projections showing declining mitigation potential of only 1.4 - 1.7 Mg ha⁻¹ over 30 years under climate change scenarios [

83]. The superior consistency of biochar in temperate climates stems from its intrinsic recalcitrance, with 97% of biochar carbon persisting in stable form with mean residence times of approximately 556 years [

84], rendering it largely independent of temperate climate fluctuations in temperature and precipitation. In contrast, no-till effectiveness in temperate regions is fundamentally constrained by soil-specific properties and temporal dynamics of seasonal carbon fluxes [

85], making it a less reliable climate mitigation strategy compared to biochar application. Biochar reduced N

2O emissions by 16.2% based on meta-analysis of 119 paired observations from 18 studies [

86], whereas no-till agriculture reduced N

2O by 11% (95% CI: -19 to -1%) from 212 observations across 40 studies [

87], indicating substantially greater variability in no-till effectiveness (

Table 3).

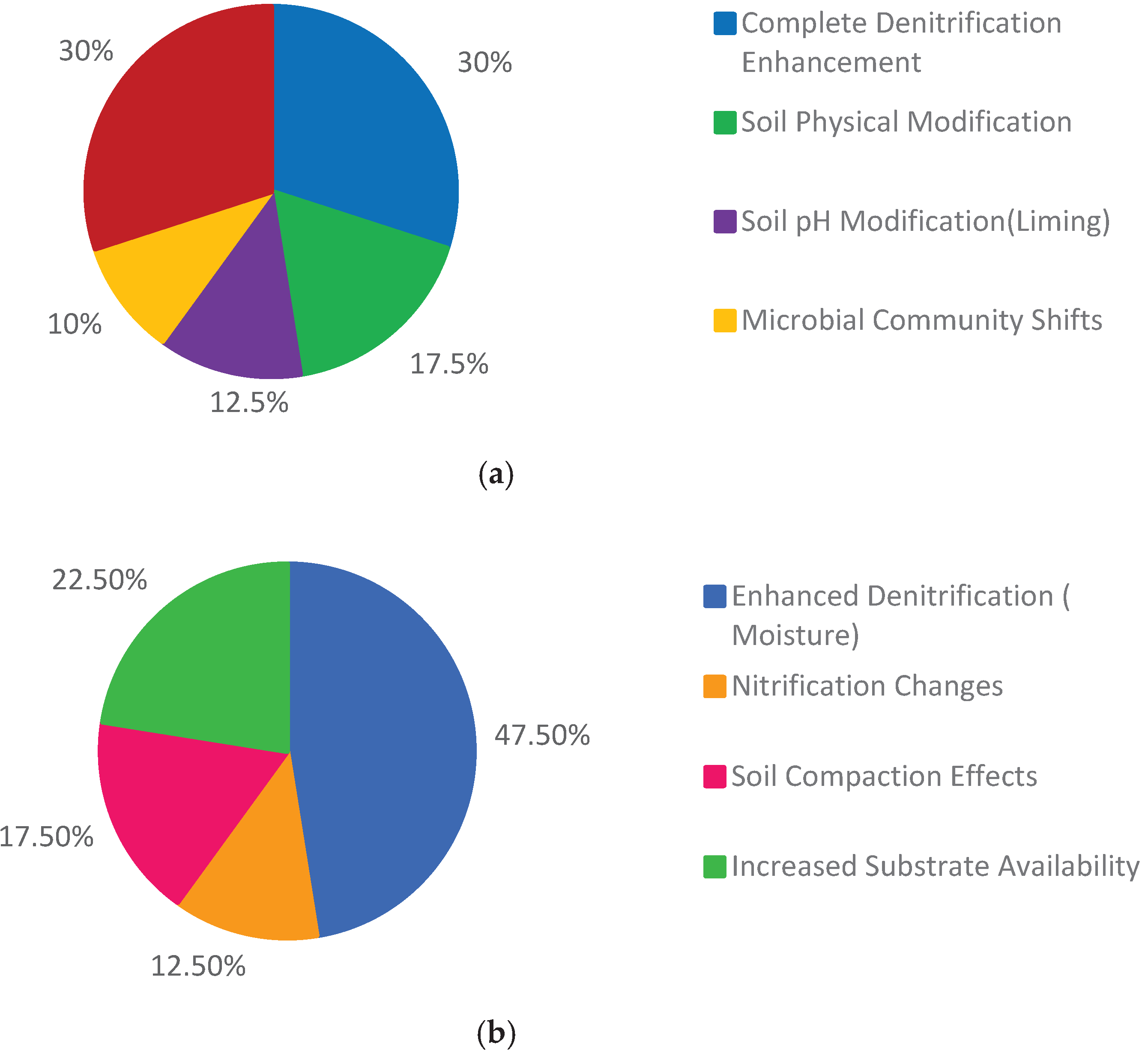

Research has identified multiple interconnected mechanisms through which biochar reduces soil N

2O emissions in agricultural systems. Rather than operating through a single pathway, biochar's effectiveness derives from synergistic interactions among five primary mechanisms, each contributing differentially to overall N

2O reduction (

Figure 5 a). Nitrogen immobilization and adsorption represent the first major mechanism (30% of effect), operating through direct adsorption of NH₄⁺ and NO₃⁻ onto biochar's aromatic carbon surface, thereby reducing substrate availability for nitrification and denitrification pathways that produce N

2O [

91]. Complete denitrification enhancement represents the second dominant mechanism (30% of effect), functioning through biochar's electron shuttle effect that facilitates electron transfer to soil denitrifying microorganisms and promotes the final reduction of N

2O to N

2 through upregulation of nosZ genes encoding N

2O reductase [

92].

Three secondary mechanisms contribute the remaining 40% of mitigation effect: soil physical modification (17.5%) through increases in mesopore size and specific surface area that enhance aeration; soil pH modification (12.5%) through the liming effect that reduces nitrification in acidic soils; and microbial community shifts (10%) that reduce ammonia-oxidizing archaea while promoting N

2O-reducing bacteria [

91,

93]. These interconnected mechanisms produce consistent field-observed N

2O reductions of 18-54%, with substantially greater reductions (84%) when biochar is combined with nitrogen fertilization [

88,

89,

94].

The high variability in no-till N

2O responses ranging from 19% reductions to 70% increases [

87,

90] stems from the fundamentally production-enhancing nature of its primary mechanisms (

Figure 5 b). Unlike biochar, which operates through multiple N

2O reduction pathways, no-till's mechanisms predominantly enhance conditions favorable for N

2O production. The dominant mechanism, enhanced denitrification through moisture accumulation (47.5%), creates anaerobic microsites where incomplete denitrification predominates. No-till significantly increased soil denitrification by 85% compared to conventional tillage, with a 33% increase in the (nirK + nirS)/nosZ gene ratio, indicating that N

2O is released rather than being further reduced to N

2 [

95]. This moisture-induced denitrification is particularly problematic in humid temperate regions where water-filled pore space frequently exceeds 70%, creating sustained anaerobic conditions. Substrate availability from residue accumulation (22.5%) and soil compaction effects (17.5%) further promote N

2O production by providing carbon for denitrifiers and restricting oxygen penetration [

95,

96]. Variable nitrification responses (12.5%) add complexity depending on local moisture regimes [

96]. The mechanistic basis for no-till's inconsistency contrasts fundamentally with biochar's reliability. Where biochar's mechanisms actively convert N

2O to N

2 and immobilize nitrogen substrates, no-till's mechanisms create conditions favoring N

2O production. This explains why meta-analysis shows conservation tillage increased N

2O by 17.8% on average [

90], despite some studies reporting reductions. For temperate regions prioritizing consistent N

2O mitigation, biochar's reduction-focused mechanisms represent a more reliable approach than no-till's production-enhancing pathways.

Crop rotation is a key practice in sustainable farming, involving the sequence of planting various crops in the same field over multiple seasons to enhance soil fertility and productivity. It is distinct from other methods, such as intercropping and monoculture (monocropping) [

97]. Crop rotation increases soil carbon sequestration and lowers CO

2 emissions [

98]. The case study by Lötjönen and Ollikainen [

99] outlines the environmental benefits of crop rotation over monoculture, particularly in terms of reduced fertilization needs, lower nitrogen runoff, and decreased greenhouse gas emissions. Rotating legumes, like clover-wheat, also lowers GHGs emissions and nitrogen runoff [

99,

100]. Crop rotation helps reduce CO

2 emissions by improving soil organic matter (SOM) and minimizing the need for tillage and fertilizers. Systems that incorporate legumes and perennials enhance carbon input and sequestration over time [

101,

102]. Al-Musawi, Vona [

103] highlights the significance of various crop rotation systems for both agricultural and environmental sustainability. The authors explain that crop rotation can notably improve soil structure and organic matter levels, as well as boost nutrient cycling. Additionally, when legumes are incorporated into rotations instead of monoculture systems in Europe, soil organic carbon increases by up to 18%. This practice also helps reduce greenhouse gas emissions, promote carbon sequestration, and lower nutrient leaching and pesticide runoff. Legume-based rotations also influence other greenhouse gases. By improving nitrogen efficiency, these rotations can decrease N

2O emissions by as much as 39% [

104]. In flooded rice systems, rotating with upland crops like maize or sorghum can reduce CH

4 emissions by up to 84% by interrupting anaerobic soil conditions [

105]. Similarly, improved irrigation techniques, such as alternate wetting and drying (AWD) in rice systems, have demonstrated the potential to lower CH₄ emissions without reducing yields [

106]. These strategies underscore the technical viability of soil- and crop-based interventions, though their outcomes are often highly context-specific and influenced by environmental and management factors [

107].

Despite their potential, significant challenges limit the widespread adoption of these practices. Research indicates variability in mitigation outcomes due to soil type, climate conditions, and crop management intensity, making generalized recommendations difficult [

108]. For example, while no-till farming may enhance soil carbon in temperate zones, its benefits in tropical systems remain inconsistent [

109]. Economic and social barriers, including high costs of inputs, lack of farmer awareness, and limited access to technologies, also hinder uptake [

110]. Moreover, long-term impacts are not always well documented, with short-term studies dominating the literature and leaving uncertainties about sustainability over decades [

111]. Addressing these gaps requires integrative approaches that combine technical innovations with enabling policies, financial incentives, and knowledge-sharing networks to promote scalable, farmer-centered solutions [

112].

Table 4 summarizes key studies on crop and soil management practices, highlighting their potential for GHG mitigation along with associated challenges and limitations.

3.3. Nitrous Oxide Mitigation through Nutrient Management

Agricultural systems are responsible for significant emissions of N₂O, one of the most potent greenhouse gases, mainly due to the application of nitrogen fertilizers and the use of manure. Nutrient management strategies therefore play a pivotal role in reducing N₂O emissions. The “4R” framework right source, right rate, right time, and right placement of fertilizers has consistently been shown to improve nitrogen use efficiency and curb unnecessary losses to the atmosphere [

113]. The adoption of enhanced efficiency fertilizers, including slow-release formulations and nitrification inhibitors, further reduces emission intensity while maintaining crop productivity [

114]. Precision agriculture technologies such as site-specific nutrient application and sensor-guided irrigation are also gaining traction for optimizing inputs and minimizing hotspots of N₂O production [

115]. In rice-based systems, the integration of water-saving irrigation with balanced nutrient management offers significant reductions in both N₂O and CH₄ emissions, supporting multiple climate benefits [

116].

However, widespread adoption of these approaches faces both technical and socio-economic challenges. Regional disparities in fertilizer access, affordability, and farmer training often limit implementation in smallholder-dominated agricultural systems [

117]. In some contexts, nitrification inhibitors and enhanced efficiency fertilizers remain prohibitively expensive, while their long-term environmental effects are still debated [

118]. Additionally, studies highlight a lack of harmonized emission factors for diverse cropping systems, leading to uncertainty in estimating mitigation potential at larger scales [

119]. Research also underscores the need for long-term field experiments to validate laboratory or short-duration results, particularly in tropical and semi-arid regions [

120]. Without supportive policies, subsidies, and knowledge-sharing mechanisms, the effectiveness of nutrient management as a mitigation strategy will remain underutilized [

121,

122].

Table 5 outlines key studies on nutrient management strategies for nitrous oxide mitigation, emphasizing technical advances, adoption barriers, and future research needs.

3.4. Socio-Economic and Policy Dimensions of Adoption

While technical interventions for reducing GHG emissions in agriculture are well established, their large-scale adoption is often constrained by socio-economic realities.

Farmers face barriers such as limited access to credit, insecure land tenure, and inadequate extension services, all of which reduce their willingness or ability to invest in sustainable practices [

123]. Studies show that adoption rates of conservation tillage, precision nutrient management, and agroforestry remain low in developing regions despite their proven benefits, largely due to upfront costs and perceived risks [

124]. Knowledge gaps and lack of training further hinder uptake, especially among smallholder farmers, who form the backbone of global food production [

125]. Gender and social inequalities also influence adoption, as women farmers often have less access to resources, technologies, and decision-making platforms [

126].

Policy frameworks play a decisive role in shaping adoption outcomes. Well-designed incentives, including subsidies for biochar, carbon credits for agroforestry, and payments for ecosystem services, can accelerate the uptake of mitigation practices [

127]. However, the effectiveness of such policies depends on transparent monitoring, verification, and enforcement mechanisms [

128]. Market-based approaches, such as carbon trading, are gaining prominence, but they often overlook small-scale farmers and risk exacerbating inequalities [

129]. Integrated CSA policies that combine financial support, capacity building, and technology dissemination are essential to overcome these limitations [

129]. Strengthening institutional support, aligning national climate commitments with local agricultural strategies, and promoting participatory approaches to policy design can further enhance adoption [

130,

131].

Table 6 synthesizes socio-economic and policy dimensions affecting the adoption of agricultural GHG mitigation practices, highlighting barriers, incentives, and institutional mechanisms.

3.5. Integrated Approaches and Future Pathways

The complexity of GHG emissions in agriculture highlights the need for integrated approaches that combine technical, ecological, and socio-economic dimensions.

Studies increasingly point to the effectiveness of multi-practice systems, such as combining conservation tillage with biochar application and precision nutrient management, which generate cumulative benefits for carbon sequestration, yield stability, and emission reduction [

132]. Integrated crop–livestock systems offer another pathway, recycling organic residues and manure to enhance soil fertility while lowering N₂O and CH₄ emissions [

133]. Similarly, CSA frameworks emphasize regenerative practices, diversification, and resilience-building measures that address both mitigation and adaptation needs [

134]. The use of digital tools, including remote sensing, artificial intelligence, and decision-support systems, has further strengthened the potential of integrated strategies by enabling more accurate monitoring and site-specific interventions [

135].

Looking forward, the future of agricultural GHG mitigation depends on scaling these integrated approaches through supportive policies and international cooperation. Long-term field experiments and region-specific trials are essential to validate the durability and effectiveness of proposed strategies [

136]. Emerging innovations such as microbial amendments, carbon farming markets, and recoupled energy–agriculture systems offer promising new avenues but require careful socio-economic and environmental assessment [

137]. Bridging the gap between smallholder realities and global climate goals remains a critical challenge, calling for inclusive financing mechanisms, equitable access to technologies, and participatory governance [

138]. By uniting scientific advances with farmer-driven practices and robust institutional frameworks, integrated approaches provide a pathway for achieving sustainable and verifiable emission reductions in line with international climate targets [

139,

140,

141].

Table 7 compiles key studies on integrated approaches and future pathways, emphasizing technological, ecological, financial, and policy innovations for agricultural GHG mitigation.

The application of ICEMF in practice requires addressing key barriers such as financial limitations, technology adoption, and socio-economic contexts. Case studies from regions where mitigation strategies have been implemented (e.g., agroforestry in Sub-Saharan Africa) could help validate the framework and refine its predictions. Future research should prioritize long-term field experiments and integrate more localized data to test ICEMF's scalability. Moreover, exploring socio-economic barriers to adoption, such as access to capital and knowledge gaps, will be crucial in improving the practical applicability of the ICEMF framework in different agricultural systems.