3.1. Changes in Soil N and C Pools, N Balance, and N and C Sequestration

The changes in inorganic N expressed in total equivalent soil mass (inorganic Nem) from 2012 to 2017 were −77, 50, and 107 kg inorganic Nem ha-1 for the TC0N, TDM, and TSU, respectively. These changes in inorganic Nem reflect the sum of the changes in NO3-N expressed in equivalent soil mass (NO3-Nem) and NH4-N expressed in equivalent soil mass (NH4-Nem). The changes in soil organic N expressed in equivalent soil mass (soil organic Nem) were 0, 708, and −597 kg soil organic Nem ha-1 for TC0N, TDM, and TSU, respectively. Thus, the total changes in total soil N expressed in equivalent soil mass (total soil Nem) were −77, 758, and −490 kg N ha-1 for TC0N, TDM, and TSU, respectively. These changes in total soil Nem suggest that N from the soil organic Nem pool of the TSU treatment was being lost. These findings of soil organic Nem losses are in agreement with the soil organic Cem losses, suggesting there is active soil microbial biomass in a tilled system that is not only contributing to these dynamics and transformations (and thus contributing to N cycling) but also in this case to N losses from the system (e.g., losses of N from the organic N pool).

This loss of N from the total soil N

em of TSU agrees with a previous N balance study conducted for a no-till continuous corn system at this site that found N is being lost from the total soil N

em and soil organic N

em pools [

7]. The loss of 98 kg N ha

-1yr

-1 from the TSU treatment in this five-yr. N balance study is four times higher than the loss observed in the NT study (24 kg N ha

-1yr

-1) that was conducted with a 13-yr. N balance at this site [

7]. The greater N losses from the total soil N

em and soil organic N

em pools observed with the TSU treatment than with the NT studies agree with findings from various studies that have reported greater C losses from tilled systems than no-till systems [

31,

32,

33,

34]. We did not detect N being lost from the soil organic N

em pool with the TC0N using the Delgado et al. (2023) [

7] peer-reviewed method that used the P<0.18 level. We suggest that five years was not enough time to detect these changes in soil organic N

em loss from the TC0N at P<0.18. The negative N loss detected in total soil N

em with TC0N (−77 kg total soil N

em ha

-1) suggests that the control plots are also losing N from the soil organic N

em pool at this site. The NH

4-N

em of TC0N increased across the soil profile while the NO

3-N

em decreased across the soil profile, an additional indication that N was being lost from the soil organic N

em with TC0N and/or that a significant amount was removed with the harvested grain and bailed out of the TC0N. In contrast to these findings of losses of soil organic N

em with no-till and tilled systems fertilized with inorganic N, the TDM is sequestering N in the soil at a rate of 126 kg N ha

-1 yr

-1.

While the 2012 to 2017 losses of TSU soil organic N

em were occurring, TSU was also losing −1190 kg ha

-1 of soil organic C expressed in equivalent soil mass (soil organic C

em; −198 kg C ha

-1yr

-1). We were not able to detect the loss of soil organic C

em from the TC0N at P<0.18. We suggest that five years was not enough time to detect these changes in soil organic C

em loss from the TC0N at P<0.18. In contrast, we found that the manure-fertilized plots are sequestering C in the soil at a rate of 2830 kg C ha

-1 y

-1, for a total of 17,000 kg C ha

-1 sequestered from spring 2012 to fall 2017. The dry manure C content of 16.7% for the TDM measured in our laboratory was similar to the C content of 17% that has been reported in the literature for feedlot cattle manure [

27].

The TDM plots received a total of 424,000 kg dry manure ha-1, which contained 62,300 kg C ha-1 and 4538 kg N ha-1, respectively. Although we don’t know how much C was sequestered from the manure versus how much was sequestered from crop residue (e.g., roots), if we divide the C sequestration by the total C applied with the manure, we estimate that about 27% of the applied C with manure was sequestered in the soil. If we also account for the fact that applying inorganic N and tilling the system (TSU) generates a loss of 1190 kg C ha-1, then TDM sequestered 43% of the applied C with manure compared to the tilled system receiving inorganic fertilizer. This is important for farmers to know if they are interested in seeking potential compensation for sequestering C in their agricultural system.

The total organic or inorganic N fertilizer inputs were 2097, 1070, and 0 kg N ha

-1 with TDM, TSU, and TC0N, respectively. We applied an additional 121 kg N ha

-1 with the irrigation water to all the plots. Using the same method as Delgado et al. (2023) [

7], we found that the estimation of atmospheric N inputs at the site was 31.2 kg N ha

-1 for 2012 to 2017.

The amount of N removed with the harvested grain was 373, 809, and 855 kg N ha-1 for the TC0N, TDM, and TSU treatments, respectively; with bailing and removal of crop residue after harvesting, the amount of N removed was 193, 436, and 373 kg N ha-1 for the TC0N, TDM, and TSU treatments, respectively. An N balance accounting for changes in the soil N pools in the 0 to 120 cm soil profile found that the system nitrogen use efficiency (NUESys) for TDM is 86.3%, which is higher than the NUESys for TSU (60.2%). The TDM loss of 13.7% of the N inputs to the environment is lower than the 39.8% observed with TSU. For total N mass loss, the N balance found that the N loss from TSU from 2012 to 2017 of 488 kg N ha-1 was higher than that of TDM, which was 309 kg N ha-1. The higher NUESys of TDM compared to TSU was not just because TDM removed more nitrogen (a total of 1250 kg N ha-1 compared to 1230 kg N ha-1 removed with TSU); rather, the N balance reveals that the key reason is that TDM sequestered a large amount of N in the soil organic N (708 kg N ha-1) while TSU resulted in a loss of 597 kg N ha-1 of soil organic N from 2012 to 2017. This loss is the mineralization of practically 100 kg N ha-1 that was available for corn uptake but instead escaped to the environment.

Although the manure system (TDM) was sequestering C and N, it still had an average loss of 300 kg N ha

-1, for an average 50 kg N ha

-1yr

-1, exceeding the average loss of 40 kg N ha

-1 yr

-1 under no tillage with the 202 kg N ha

-1 rate reported by Delgado et al. (2023) [

7] at this site. These findings show that tilled systems (TSU) are losing significant C and N at a higher rate than the no-till system at this site, and that although on a percentage basis the manure system is sequestering C and N, with significant increases in total N balance, the amount of N lost from the system is still significantly higher than the amount of N lost with a no-till system. The rate of soil organic C

em and soil organic N

em sequestration for the 0 to 7.6 cm and 7.6 to 15 cm depths was higher with manure (TDM, TDMAP) than the rate of soil organic C

em and soil organic N

em losses with inorganic N (TSU, TUF, P<0.05,

Table S25).

3.2. Effects of Organic and Inorganic N Inputs on Soil Parameters: 2012 to 2017

For the 2012 to 2017 period, we did not detect any differences in total inorganic C expressed in equivalent soil mass at any of the depths from 0 to 120 cm (P<0.05,

Table S6). In contrast, total extractable P expressed in equivalent soil mass (extractable P

em) started to increase quickly after the first year of manure application, and extractable P

em was significantly higher for TDM, TDMAP, and TDMSU (the manure treatments) than the other treatments (P<0.05,

Table S6). This signal of higher extractable P

em was also observed for the 7.6 to 15 cm and 15 to 30 cm depths with just one application of manure. Higher extractable P

em content was constantly observed with the manure treatments in 2013, 2014, and 2016 (P<0.05,

Table S6). For example, in 2016 the average extractable P

em for the manure treatments was 103, 103, and 27 kg P ha

-1 for the 0 to 7.6, 7.6 to 15, and 15 to 30 cm depths, respectively (P<0.05,

Table S6), which was higher than the average extractable P

em for TSU and TC0N of 13, 9, and 5 kg P ha

-1 for the 0 to 7.6, 7.6 to 15, and 15 to 30 cm depths, respectively (P<0.05,

Table S6). All manure-treated plots had significantly higher extractable P

em than the inorganic-N-fertilized treatments and the control plots receiving no inorganic N fertilizer or manure (extractable P

em of TDM, TDMAP, and TDMSU > extractable P

em of TSU, TUF and TC0N; P<0.05).

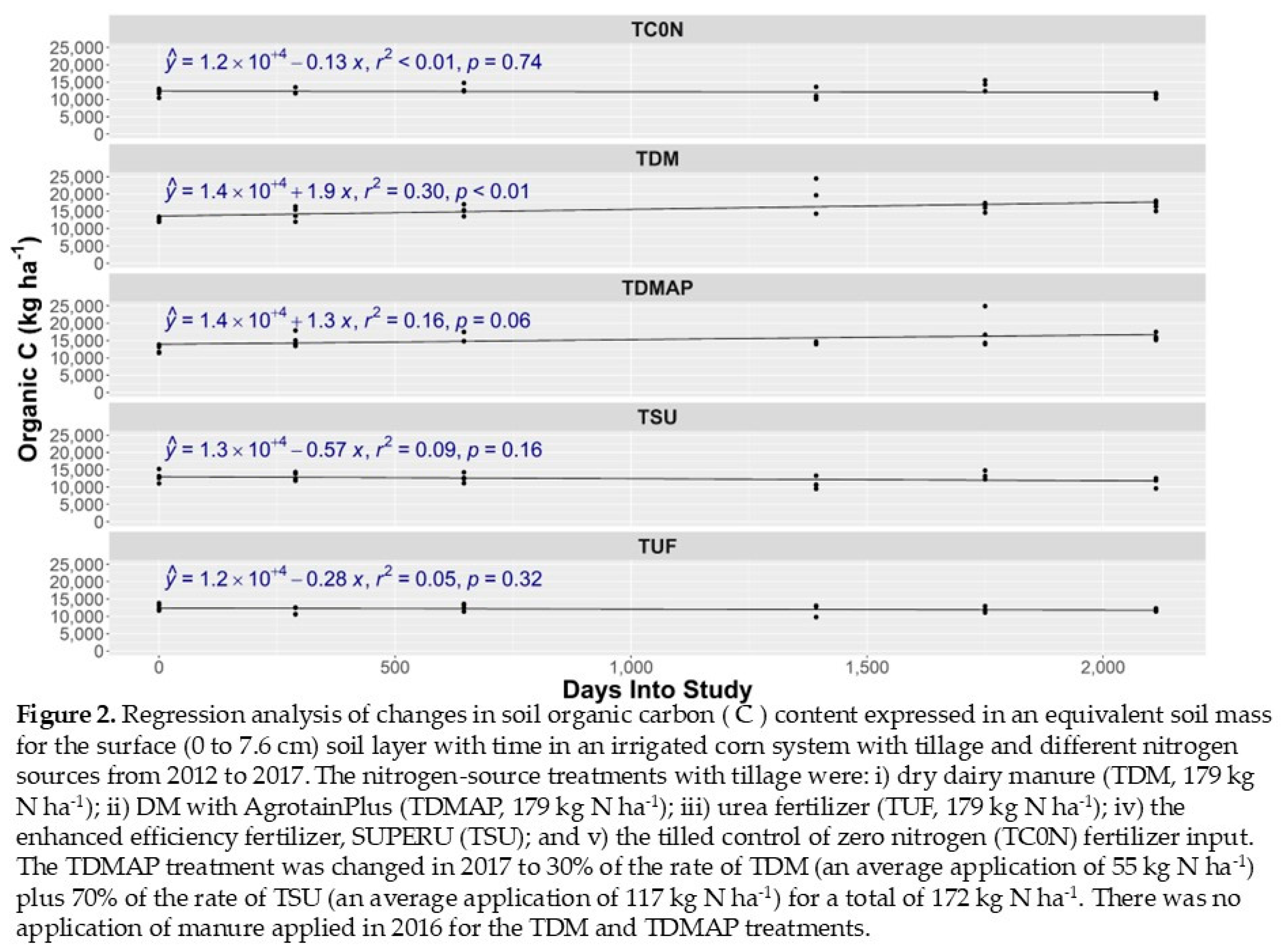

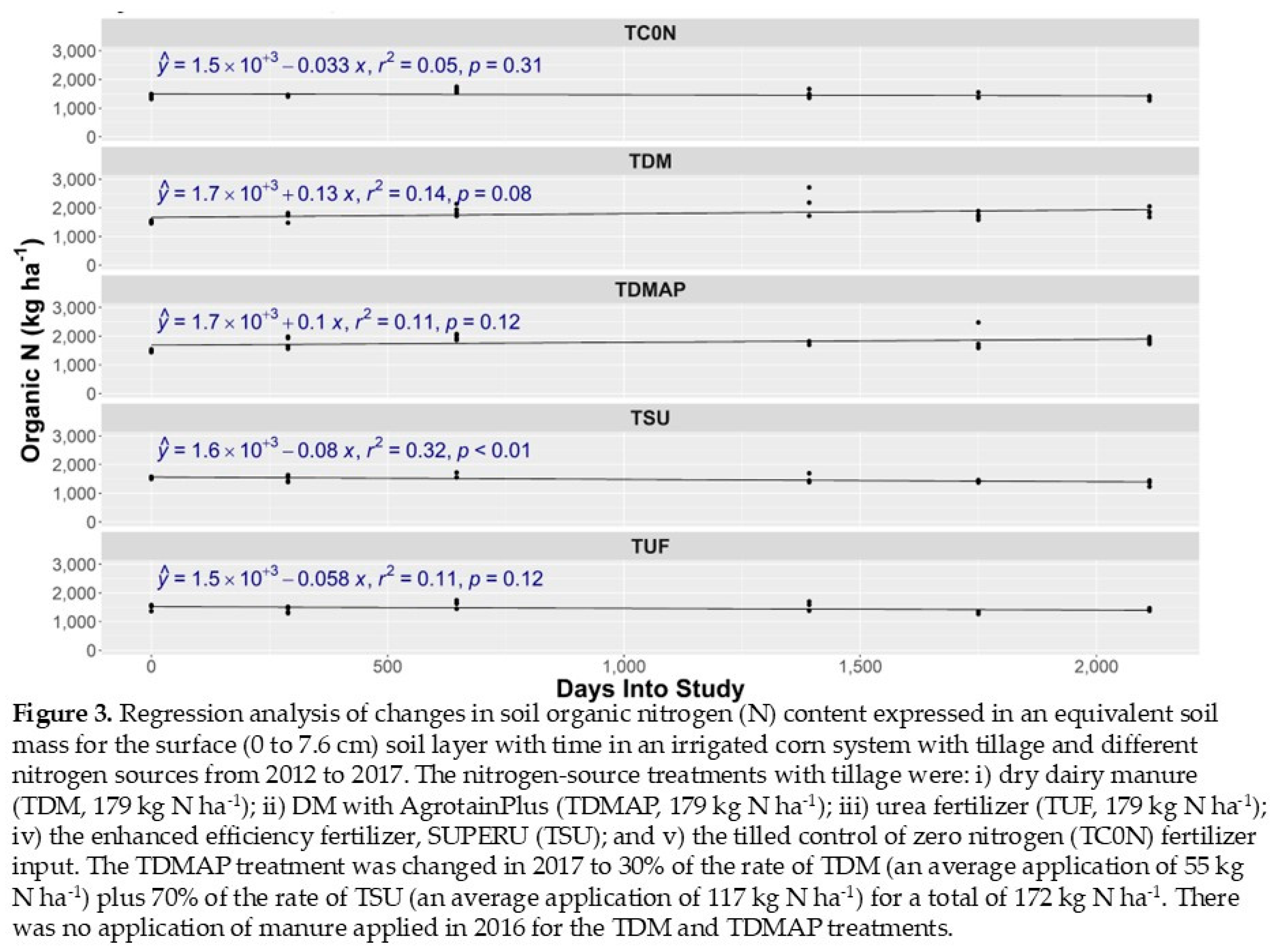

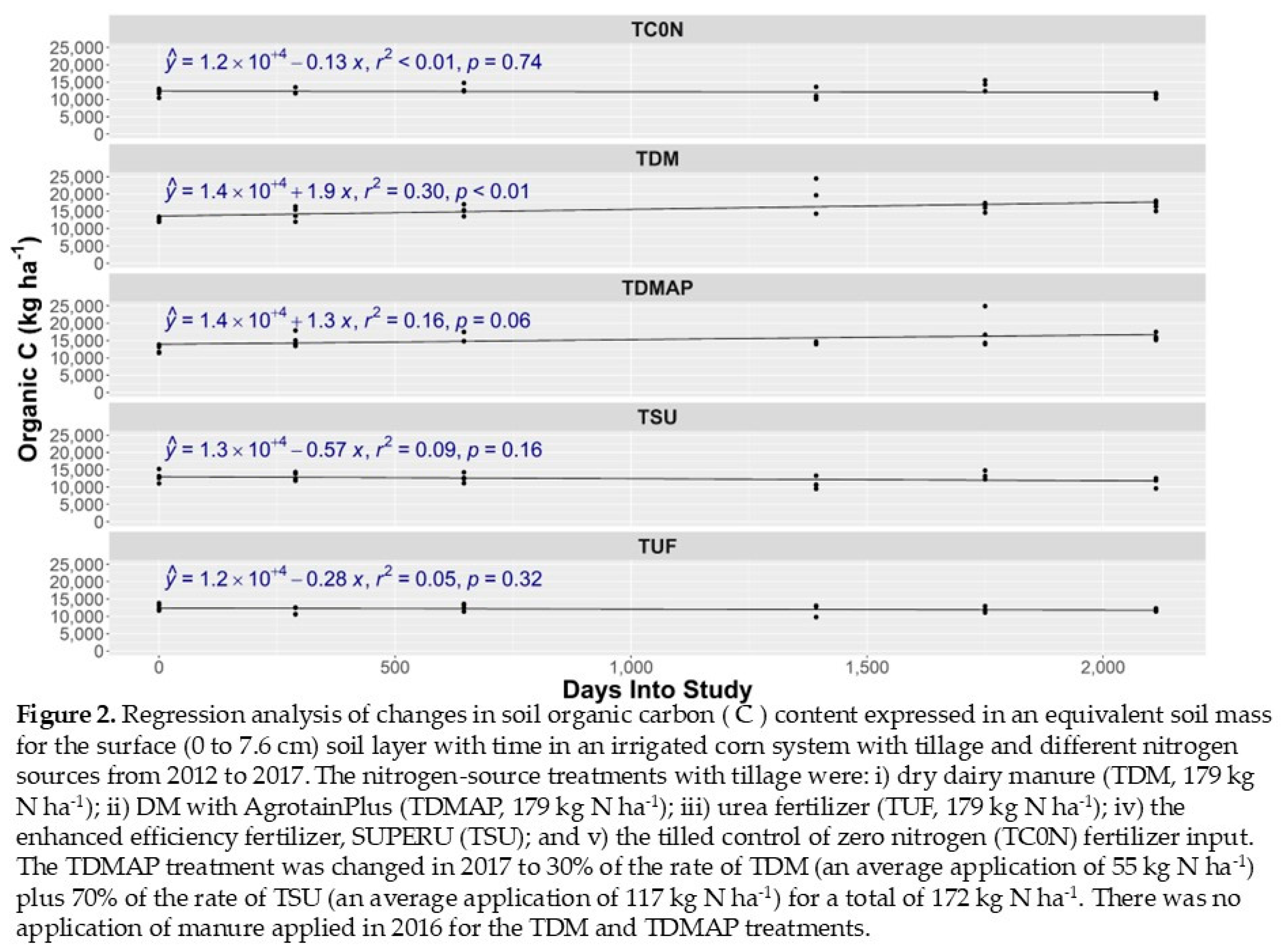

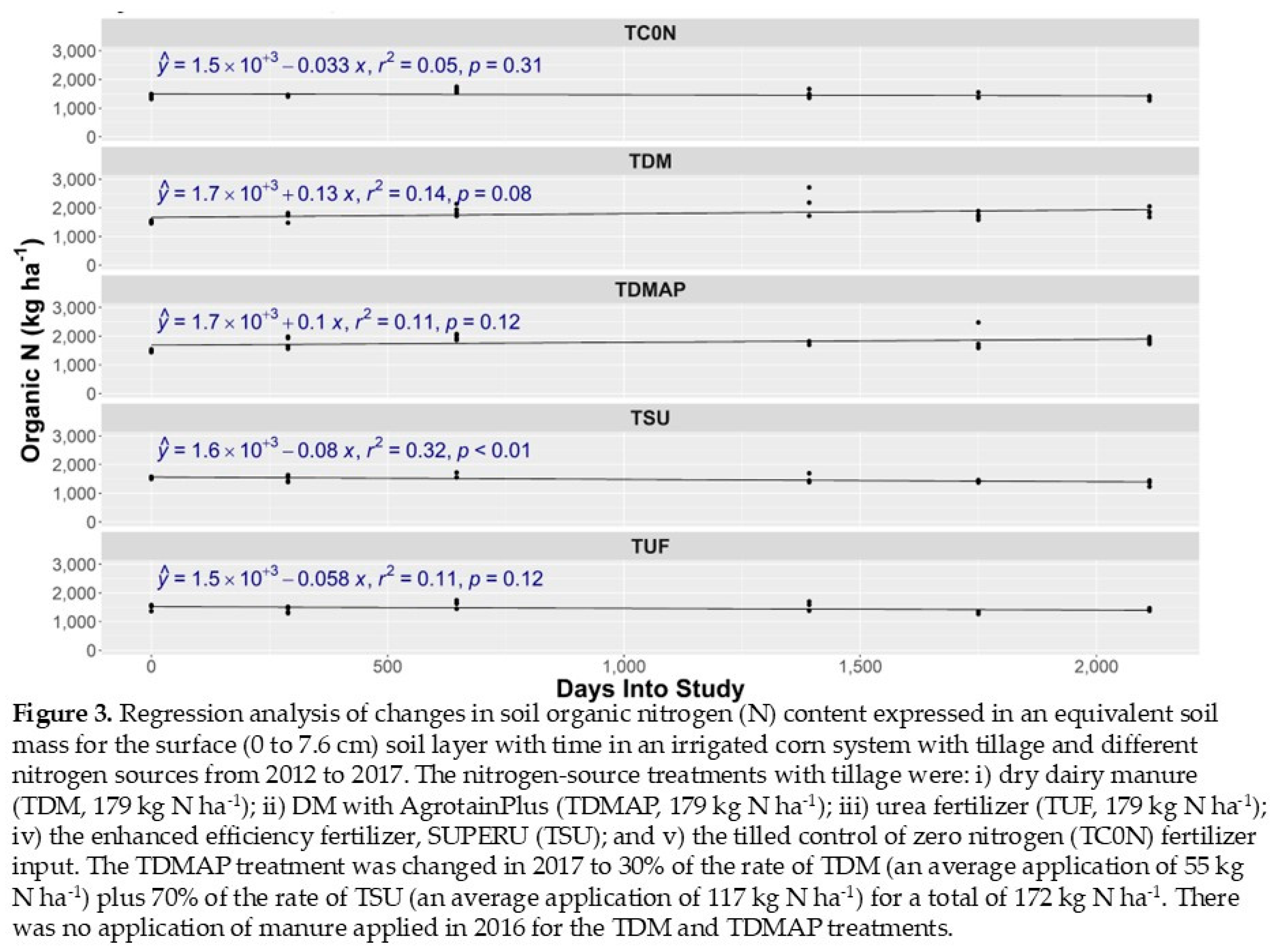

Similarly to extractable P

em, we detected significant increases in soil organic C

em at the 0 to 7.6 cm soil depth with the TDM and TDMAP treatments in 2012, which were higher than TSU, TUF, and TC0N in 2012, and through 2013 to 2017 (P<0.05,

Table 1,

Table S6; Figure 2). By 2015, the average soil organic C

em of TDM and TDMAP was 16,800, 17,200, and 29,900 kg C ha

-1 at the 0 to 7.6, 7.6 to 15, and 15 to 30 cm depths, respectively, which exceeded the average soil organic C

em of the TUF, TSU, and T0N of 11,400, 11,900 and 21,300 kg C ha

-1 at the 0 to 7.6, 7.6 to 15, and 15 to 30 cm depths, respectively (P<0.05,

Table 1,

Table 2; Figure 2, Figure 3;

Table S6). Similarly to the observed immediate increases in extractable P

em and soil organic C

em, there was also an immediate increase in soil organic N

em in 2012, that continued during 2013, 2015, 2016, and 2017 (P<0.05,

Table 2,

Table S6; Figure 3). The average soil organic N

em values for TDM and TDMAP were 1,850 and 1,910 kg N ha

-1 for the 0 to 7.6 and 7.6 to 15 cm soil depths, respectively, which exceeded the average soil organic N

em values of 1,380 and 1,440 for TSU, TUF, and TC0N, respectively (P<0.05,

Table S6).

The total soil C expressed in equivalent soil mass (total soil C

em) with the TDM was higher than the total soil C

em for TC0N, TSU, and TUF in the top 30 cm in 2014, 2015, and 2017 (P<0.05,

Table S6). The average total soil N

em with TDM and TDMAP was higher from 2012 to 2017 than with TC0N, TSU, and TUF. In 2017, the average total soil N

em values for TDM and TDMAP of 1,876 and 1,940 kg N ha

-1 at the 0 to 7.6 and 7.6 to 15 cm depths, respectively, were higher than those of the TC0N, TSU, and TUF treatments, which averaged 1,410 and 1,470 kg N ha

-1 for the 0 to 7.6 and 7.6 to 15 cm depths, respectively (P<0.05,

Table S6).

3.3. Effects of Organic and Inorganic N Inputs on Soil Parameters: 2012 to 2022

Similarly to the changes that we observed in extractable P

em (

Table 3) we detected changes in inorganic N

em in 2013, 2018, 2019, and 2022, when lower inorganic N

em was detected for TC0N at various depths from 0 to 120 cm (P<0.05,

Table S6). We also detected differences in inorganic N

em between the organic and inorganic N inputs at the lower depths of 30 to 61 cm, and occasionally at even greater depths, in 2013, 2018, and 2019 (P<0.05,

Table S6). This suggests that inorganic NO

3 was being moved to lower depths and perhaps leaching out of the system, in agreement with findings by Delgado et al. (2023) [

7]. The differences in NO

3-N

em were observed constantly from 2013 to 2019 and from 2021 to 2022 in fall soil sampling events, with TC0N constantly having the lower NO

3-N

em content. This supports the conclusion that organic and inorganic N fertilizer inputs increased NO

3-N

em levels above background levels and that NO

3-N

em is one of the pathways for movement of inorganic N

em through the soil profile and out of the system. The data shows constantly higher NO

3-N

em levels above control levels at the 30 to 61 cm depths, and even up to the 150 to 180 cm soil depths (P<0.05,

Table S6). The inorganic N fertilizer sources consistently had higher concentrations at the lower depths, and we only detected higher concentrations for the manure treatments at the 15 to 30 cm depth. These results suggest that among all the organic and inorganic N inputs, the inorganic N fertilizer sources were more mobile, contributing to the movement of NO

3-N

em to greater soil depths, and thus higher NO

3-N

em than the non-fertilized TC0N and manure plots (TDM and TDMAP) at this site (P<0.05,

Table S6).

Table 1.

Differences in soil organic carbon (C) content expressed in equivalent soil mass at the surface (0 to 7.6 cm) soil layer among treatments receiving different nitrogen sources (nitrogen sources with tillage study) in an irrigated, continuous corn system grown from 2012 to 2023¥ β.

Table 1.

Differences in soil organic carbon (C) content expressed in equivalent soil mass at the surface (0 to 7.6 cm) soil layer among treatments receiving different nitrogen sources (nitrogen sources with tillage study) in an irrigated, continuous corn system grown from 2012 to 2023¥ β.

| Year$ |

TDM |

|

TUF |

TSF |

TC0N |

| ----------------------------------------------------- kg C ha-1 ----------------------------------------------------------- |

| 2012-Spring |

12,575 aA |

12,523 aA |

12,685 aA |

13,011 aA |

11,934 aA |

| 2012-Fall |

14,377 abAB |

15,100 aA |

11,555 bB |

13,060 abAB |

12,231 abAB |

| 2013-Fall |

15,257 abAB |

16,135 aA |

12,661 bB |

12,594 bB |

13,056 bB |

| 2015-Fall |

19,473 aA |

14,186 abAB |

11,870 bB |

11,016bB |

11,263 bB. |

| 2016-Fall |

16,217 aAB |

17,465 aA |

11,924 aB |

13,322 aAB |

13,662 aAB |

| 2017-Fall |

16,670aA |

16,045 aA¶

|

11,752 bB |

11,474 bB |

11184 bB |

Table 2.

Differences in soil organic nitrogen (N) content expressed in equivalent soil mass at the surface (0 to 7.6 cm) soil layer among treatments receiving different nitrogen sources (nitrogen sources with tillage study) in an irrigated, continuous corn system grown from 2012 to 2023¥ β.

Table 2.

Differences in soil organic nitrogen (N) content expressed in equivalent soil mass at the surface (0 to 7.6 cm) soil layer among treatments receiving different nitrogen sources (nitrogen sources with tillage study) in an irrigated, continuous corn system grown from 2012 to 2023¥ β.

| Year$ |

TDM |

|

TUF |

TSF |

TC0N |

| ----------------------------------------------------- kg N ha-1 ----------------------------------------------------------- |

| 2012-Spring |

1503 aA |

1482 aA |

1502 aA |

1542 aA |

1425 aA |

| 2012-Fall |

1693 abAB |

1782 aA |

1403 cC |

1503 bcBC |

1431 bcC |

| 2013-Fall |

1904 aA |

1974 aA |

1619 bB |

1606 bB |

1637 bB |

| 2015-Fall |

2205 aA |

1777 abAB |

1555 bB |

1480bB |

1486 bB |

| 2016-Fall |

1728 abAB |

1858 aA |

1305 bB |

1410 abB |

1435 abAB |

| 2017-Fall |

1854aA |

1845 aA |

1407 bB |

1373 bB |

1369 bB |

Table 3.

Differences in total soil extractable phosphorous (P) expressed in equivalent soil mass at the surface (0 to 7.6 cm) soil layer among treatments receiving different nitrogen sources (nitrogen sources with tillage study) in an irrigated, continuous corn system grown from 2012 to 2023¥ β.

Table 3.

Differences in total soil extractable phosphorous (P) expressed in equivalent soil mass at the surface (0 to 7.6 cm) soil layer among treatments receiving different nitrogen sources (nitrogen sources with tillage study) in an irrigated, continuous corn system grown from 2012 to 2023¥ β.

| Year$ |

TDM |

|

TUF |

TSF |

TC0N |

| ----------------------------------------------------- kg P ha-1 ----------------------------------------------------------- |

| 2012-Spring |

38 aA |

18 abB |

17 abB |

14 bB |

21 abAB |

| 2012-Fall |

54 aA |

72 aA |

7 bB |

9 bB |

9 bB |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| 2013-Fall |

78 aA |

91 aA |

13 bB |

18 bB |

13 bB |

| 2016-Fall |

103 aA |

104 aA |

9 bB |

16 bB |

15 bB |

We did not detect practically any differences in NH

4-N

em among the treatments (TDM, TDMAP, TC0N, TUF, and TSU) in all sampled soil depths (0 to 180 cm) from spring 2012 to fall 2022 (P<0.05,

Table S6). Only on one occasion in the fall of 2021 at a depth of 15 to 30 cm did we identify a difference in NH

4-N

em between the control and SU treatments (P<0.05,

Table S6). Although there were no differences among treatments, the NH

4-N

em was increasing for TDM, TSU, and TC0N (P<0.05,

Table S9). Additionally, soil organic N

em and C

em were increasing for the manure treatments (TDM, TDMAP) and were decreasing for the inorganic-N-fertilized or non-fertilized treatments (TC0N, TUF and TSU; P<0.05,

Table S9). This strongly suggests that the microbial biomass was active and playing a major role in sequestering C and/or N, increasing soil organic matter C and N for the manure treatments (TDM, TDMAP, TDMSU; P<0.05,

Table S9), and releasing C and N from the soil organic matter with the inorganic-N-fertilized treatments and/or non-fertilized treatments (TC0N and TSU; P<0.05,

Table S9). Additionally, the differences that we saw among treatments in NO

3-N

em from 2012 to 2017 are also an indicator that the microbial biomass was active and contributing to the mineralization process that contributed to these changes in C and N content of the soil organic matter. These changes suggest there was increased mineralization and/or nitrification from the added N fertilizer (manure N and inorganic N) that was contributing to changing NH

4-N to NO

3-N and/or also being taken up by the corn growing in these plots. Delgado et al. (2023) [

7] also found that NH

4-N

em was increasing for the no-till plots at this site; however, we suggest that our data support that there was a quick transformation of NH

4-N

em to NO

3-N

em, contributing to no significant difference due to treatments in NH

4-N

em, but contributing to significant differences due to treatments in NO

3-N

em (P<0.05,

Table S6).

3.4. Effects of Organic and Inorganic N Inputs on Yields and N Uptake (2012-2023)

Silage (R5.5): We found that all organic and inorganic N inputs increased silage yields beyond TC0N during 2012, from 2015 to 2018, and in 2022 (P<0.05,

Table S10). In 2013, 2014, 2019, and 2022, the two manure treatments had higher silage yields than TC0N (P<0.05,

Table S10). In 2021, only the TDMSU silage yields were higher than those of TC0N (P<0.05,

Table S10). In 2019 and 2021, the silage production of TSU was higher than that of TC0N (P<0.05,

Table S10). In 2020 and 2023, the organic and inorganic N inputs did not increase the silage yields above TC0N (P<0.05,

Table S10). In summary, for the vast majority of years from 2012 to 2023, both organic and inorganic N inputs increased the silage yields over those of TC0N (P<0.05,

Table S10). Among organic and inorganic comparisons in 2021 and 2022, the TDMSU had higher silage production than TSU, suggesting a positive effect of adding manure with EEF vs. adding the EEF alone (P<0.05,

Table 4,

Table S10).

Physiological maturity (R6): We found that all organic and inorganic N inputs increase total aboveground biomass production above those of TC0N every year from 2012 to 2023 (P<0.05,

Table S10). Comparison of organic and inorganic N inputs revealed that in 2016 the R6 aboveground biomass production with TUF and TSU were higher than with the TDM and TDMAP; however, this was the year that we did not apply manure, showing that the manure application from 2012 to 2015 did not have sufficient recycling of N to maximize aboveground production (P<0.05,

Table S10). When organic and inorganic N inputs were applied only in 2020, 2021, and 2022, total biomass production at R6 with TDMSU was higher than TSU, supporting the hypothesis that there was a positive interaction effect of adding manure with EEF vs. EEF alone (P<0.05,

Table S10).

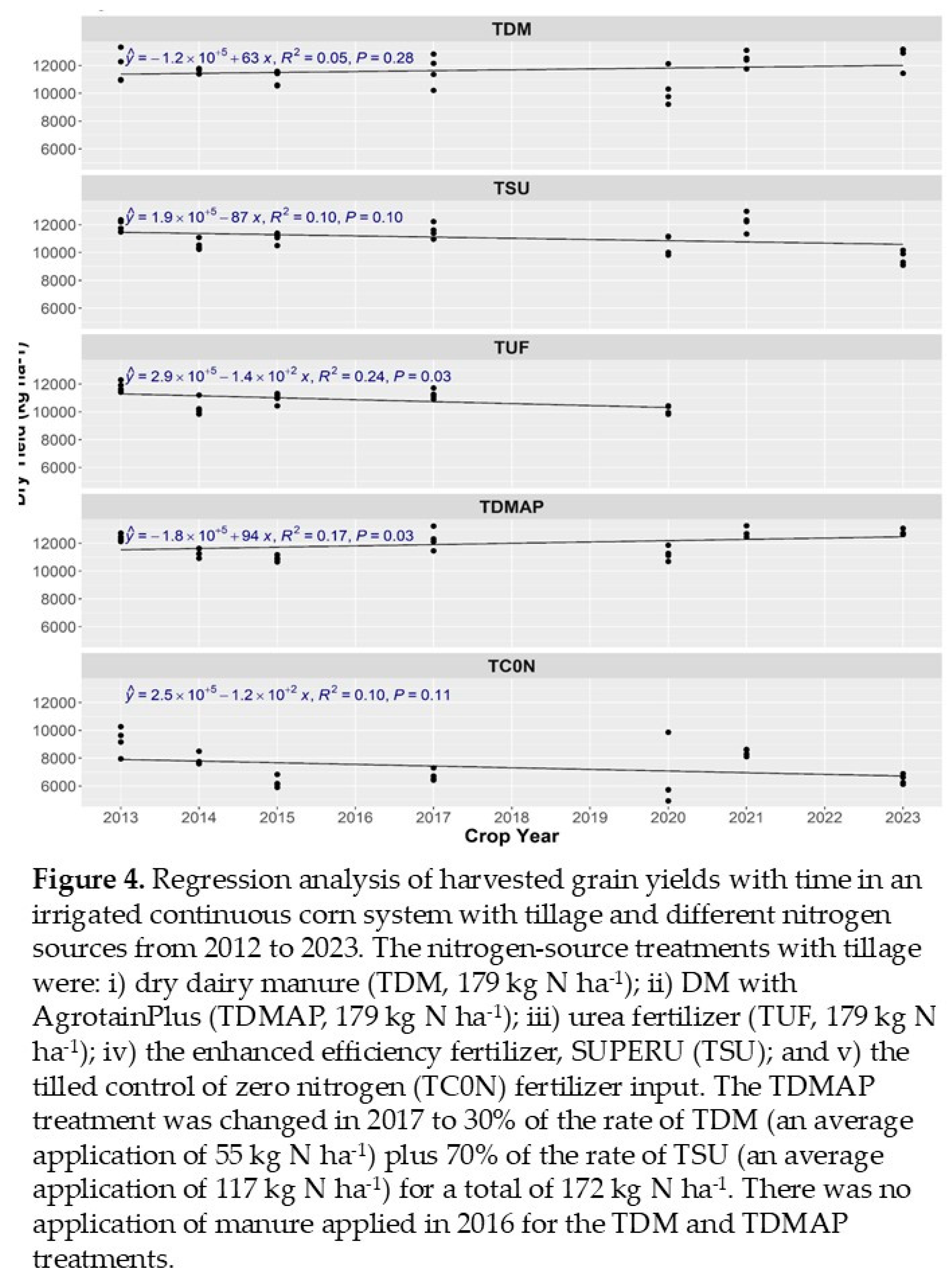

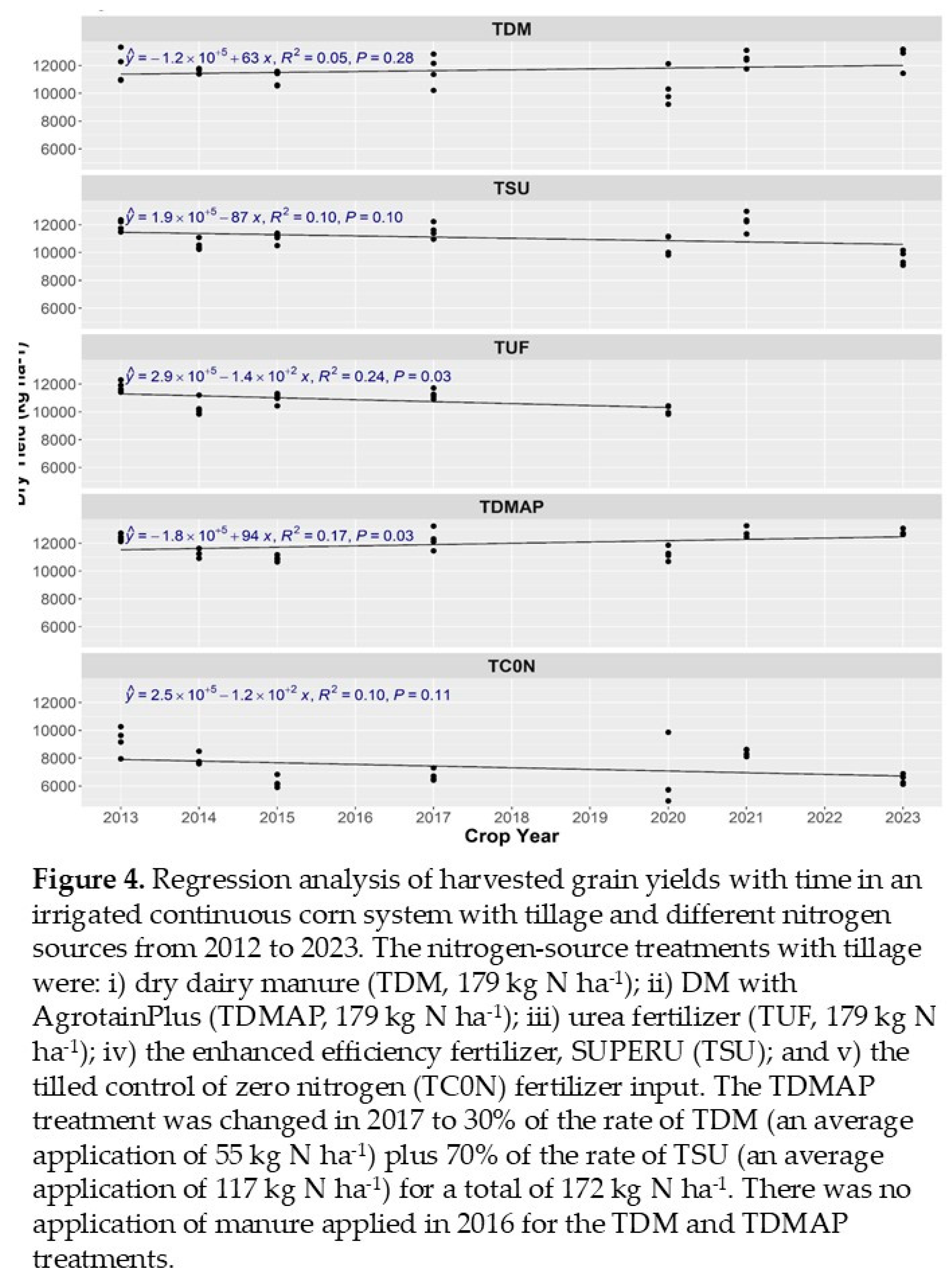

Harvested grain: We found that all organic and inorganic N inputs increased harvested grain yields above those of TC0N every year from 2012 to 2023 (P<0.05,

Table S10). Comparison of organic and inorganic N inputs revealed that in 2016 the TUF and TSU harvested grain yields were higher than those of the manure treatments; however, this was the year that we did not apply manure (P<0.05,

Table S10), showing that the manure application from 2012 to 2015 did not have sufficient recycling of N to maximize harvested grain production (P<0.05,

Table S10). Comparison of organic and inorganic N inputs when N inputs were applied, found that in 2014 harvested yields of TDM were higher than those of TUF (P<0.05,

Table S10) and that in 2023 the harvested yields of TDMSU and TDM were higher than TSU, suggesting a positive effect of adding manure with EEF compared to EEF alone (P<0.05,

Table S10).

N uptake at R5.5: We found that all organic and inorganic N inputs increased total N uptake aboveground silage (R5) production above that of TC0N every year from 2012 to 2022, except in 2016 and 2020 (P<0.05,

Table S10). A comparison of organic and inorganic N inputs found that only in 2016 was the N uptake from inorganic N sources (TSU and TU) with silage production higher than that of TC0N, but the organic manure treatments were not higher than TC0N (P<0.05,

Table S10). This shows that the N cycling from the applied manure from 2012 to 2015 did not cycle enough N to maximize N uptake with the manure treatments to increase N uptake beyond that of the control plots, but it was high enough to have N uptake with the manure treatments in the year that the manure was not applied, so it was not different from the plots with inorganic N inputs (P<0.05,

Table S10). There were no differences in N uptake in 2020 among treatments (P<0.05,

Table S10). In 2023, only TDMSU had significantly higher N uptake than TC0N, but it was not different from TDM and TSU (P<0.05,

Table S10). However, the TDM and TSU treatments did not have higher N uptake than TC0N (P<0.05,

Table S10).

N uptake at R6.0: We found that all organic and inorganic N inputs increased total N uptake aboveground biomass production at R6 beyond TC0N every year from 2012 to 2023 (P<0.05,

Table S10). Comparison of organic and inorganic N inputs revealed that in 2016 the N uptake of aboveground biomass at R6 from TSU and TUF was higher than that of TDM, and that it was higher for TSU than TDMAP. This shows that the N cycling from the applied manure from 2012 to 2015 did not cycle enough N to maximize N uptake with the manure treatments at R6 (P<0.05,

Table S10). Since the N uptake from TC0N in 2016 (the year that manure N was not applied) was 91 kg N ha

-1 and the N uptake average for TDM and TDMAP in 2016 was 167 kg N ha

-1, we estimate that the applied manure from 2012 to 2015 was cycling 76 kg N ha

-1 that was taken up by the TDM and TDMAP aboveground biomass at R6 (167 kg N ha

-1 − 91 kg N ha

-1 = 76 kg N ha

-1). Since we did not apply manure N in 2016 to the TDM and TDMAP plots, and the average N uptake of the TDM and TDMAP was 76 kg N ha

-1 higher than the control (non-N-fertilized plots; TC0N), this clearly shows that N was being cycled from manure N sources at a high N rate, illustrating the importance of accounting for N sources applied in previous years (P<0.05,

Table S10). Additionally, among organic and inorganic comparisons, when N inputs were applied only in 2021, we detected a difference among N inputs, with TDMSU resulting in higher N uptake than the TDM and TSU treatments, supporting the hypothesis that manure applications with EEF had a positive effect of recovering N compared to EEF alone (P<0.05,

Table S10).

N uptake at harvest of grain: We found that all organic and inorganic N inputs increased total N uptake content by the harvested grain above TC0N every year from 2012 to 2022 (P<0.05,

Table S10). Comparison of organic and inorganic N inputs found that in 2016 when manure was not applied, the harvested grain N uptake from TSU and TUF were higher than with TDM and TDMAP (P<0.05,

Table S10). This shows that the N cycling from the applied manure from 2012 to 2015 did not cycle enough N to maximize N uptake by the harvested grain (P<0.05,

Table S10). Since the harvested grain N uptake from TC0N was 61 kg N ha

-1 and the N uptake average from the two manure treatments was 87 kg N ha

-1, the N cycling from the applied manure from 2012 to 2015 absorbed by the grain was estimated at 26 kg N ha

-1 (87 kg N ha

-1 − 61 kg N ha

-1 = 26 kg N ha

-1). Additionally, among organic and inorganic comparisons, when N inputs were applied only in 2014 and 2023, the N content of the grain yield of TDM and TDMAP was higher than that of TSU and TUF (P<0.05,

Table S10). In 2023, TDM and TDMSU resulted in higher harvested grain N uptake than TSU (P<0.05,

Table S10).

NUEs: The NUE of the total aboveground biomass at R6 was not significantly different among treatments in 8 of the 12 years in the 2012 to 2023 period (P<0.05,

Table S10); only in 2018 (TUF > TDM), 2019 (TDM > TUF), 2020 (TDMSU > TUF) and 2021 (TDMSU > TSU and TDM) (P<0.05,

Table S10). Since we only had TDMSU since 2017, in two of the seven years TDMSU had higher NUE than the other treatments (TDM, TSU, and/or TUF; P<0.05,

Table S10). These results suggest that the application of manure with EEF may contribute to increased NUE of manure systems beyond SU alone or manure alone. Similarly, in eight of the 11 years there were no significant differences in silage NUE among treatments (P<0.05,

Table S10). Due to the onset of the covid pandemic, silage samples were not collected in 2020; silage NUEs were only significant in 2012 (TUF > TDMA), 2015 (TSU and TUF > TDM), and 2022 (TDMSU > TDM and TSU). This suggests that when we detected the differences in three of the 12 years, the advantages in NUE were for the inorganic N fertilizer treatments or a combination of inorganic fertilizer and manure treatments, rather than the organic (manure) treatments (P<0.05,

Table S10). We suggest that the continued N cycling from manure contributes to increased availability of N and increased NUE at the later harvesting stages of R6 and harvested grain, with relative advantages to TDM and/or TDMSU compared to just inorganic N fertilizer, which can potentially be vulnerable to losses early in the growing season via various loss mechanisms, while the manure can function as a slow-release fertilizer and continue to cycle N from manure from the R5.5 to R6 stages and then move the N that was taken up to the harvested grain.

The NUE of the harvested grain was more dynamic with only five of the 12 years (less than half) not being significant (P<0.05,

Table S10). We found differences in 2012 (TSU > TDMA and TDM; TUF>TDMA), 2013 (TDMA > TUF); 2014 (TDM and TDMA > TUF and TSU); 2017 (TDMSU > TUF, TDM); 2018 (TSU > TDM); 2021 (TDMSU>TDM) and 2023 (TDMSU, TDM > TSU). In the first year (2012), the NUE was higher with TSU and TUF than with TDM. Out of the other six years that we saw differences in NUE, in four years the NUE was higher with one or both of the manure treatments than at least one of the inorganic N treatments. In three of the seven years that we had the TDMSU treatment, TDMSU had higher NUE for the harvested grain. This supports the conclusion that after a year of manure applications, the cycling of the N from previous application starts contributing to higher N uptake and higher NUE compared to other treatments. It also supports the conclusion that combined applications of manure and EEF contribute to increased NUE compared to other treatments (P<0.05,

Table S10).

3.5. Harvested Grain Yields and Harvested Grain Yield N Content from 2012 to 2023: TDM and TSU vs. NT and ST

We compared the grain yields and grain yield N content of TDM and TSU to those of NT202 and ST202 by year. From 2012 to 2023, the grain yields of TDM were higher than the yields of NT202 in 2014, 2021, 2022, and 2023 (P<0.05,

Table S11). The NT202 treatment resulted in higher yields than those of TDM only in 2016, when there was no manure applied to the TDM (P<0.05,

Table S11). Thus, in four of the 11 years that manure was applied, the average yields of TDM were higher than those of NT202 (P<0.05,

Table S11). In the 11 years that manure was applied, the average yield of TDM (11,000 kg ha

-1) was higher than the average yield with NT202 (9,820 kg ha

-1;

Table S11). The comparison between TDM and ST202 was done only from 2012 to 2019 when the ST study was stopped. The yields of TDM were higher than yields of ST202 only in 2014 (P<0.05,

Table S12). The ST202 treatment had higher yields than TDM only in 2016, when there was no manure applied to the TDM (P<0.05,

Table S12). The yield of TDM was higher than that of ST202 in only one of the 7 years (P<0.05,

Table S12). In the 7 years that manure was applied, the average yield of TDM (10,800 kg ha

-1) was higher than the average yield of ST202 (10,100 kg ha

-1;

Table 5,

Table S12).

During the 2012 to 2020 period, the grain yield of TUF was higher than that of NT202 in 2017 and 2019, suggesting a small advantage of TUF over the NT202 plots (P<0.05,

Table S13). In the 9 years that urea was applied and tillage was implemented, the average yield of TUF (10,700 kg ha

-1) was higher than that of NT202 (

Table S13; 9,830 kg ha

-1). These studies suggest that compared to NT202, tilling and TUF contribute to higher yields (P<0.05,

Table S13). The yields were not higher with the NT202 than TUF in any of the 9 years of this period (P<0.05,

Table S13).

For the 2012 to 2019 period, the grain yield of TUF was higher than that of ST202 in 2017 and 2019 (P<0.05,

Table S17). In two of 8 years, TUF had higher average yields than ST202, suggesting a small advantage of the TUF over the ST202 plots. In the 8 years that urea was applied and tillage was implemented, the average yield of TUF (10,800 kg ha

-1) was higher than that of ST202 (

Table S17; 10,200 kg ha

-1). These studies suggest that compared to ST202, tilling and UF contributes to higher yields. The grain yield was not higher with the NT202 than the TUF in any of the 8 years of this period (P<0.05,

Table S17).

During the 2012 to 2016 period, the grain yields of TDMAP were higher than with NT202 in 2013 and 2014 (P<0.05,

Table S14), suggesting a small advantage of TDMAP over the NT202 plots. These studies suggest that compared to NT202, the combination of tillage and manure with AgrotainPlus contributes to higher yields. The NT202 treatment had higher yields than TDMAP only in 2016, the year that the manure was not applied to the TDMAP plots (P<0.05,

Table S14). In the four years that manure was applied with AgrotainPlus, the average yield of TDMAP (11,300 kg ha

-1) was higher than that of NT202 (10,200 kg ha

-1;

Table S14).

For the 2012 to 2016 period, the grain yields of TDMAP were higher than those of ST202 in 2014 (P<0.05,

Table S18), suggesting a small advantage of TDMAP over the ST202 plots. These studies suggest that compared to ST202, tilling and manure application with AgrotainPlus contributes to higher yields. The ST202 had higher yields than the TDMAP only in 2016, the year that the manure was not applied to the TDMAP plots. In the four years that manure was applied with AgrotainPlus, the average yield of TDMAP (11,300 kg ha

-1) was higher than that of ST202 (10,400 kg ha

-1;

Table S18).

For the 2012 to 2023 period, the grain yield of TSU was higher than that of NT202 in 2013, 2017, 2020, and 2023 (P<0.05,

Table S15). In four of 12 years, TSU had higher average yields than NT, suggesting a small advantage with TSU over the NT202 plots. In the 12 years that SU was applied and tillage was implemented, the average yield of TSU (10,800 kg ha

-1) was higher than that of NT202 (9820 kg ha

-1;

Table S15).

For the 2012 to 2019 period, the grain yields of TSU were higher than those of ST202 in 2017, 2018, and 2019 (P<0.05,

Table S16); however, in 2016 the yields of ST202 were higher than those of TSU (P<0.05,

Table S16). In three of the eight years, TSU had higher average yields than ST202. In the 8 years that SU was applied and tillage was implemented, the average yield of TSU (11,000 kg ha

-1) was higher than those of ST202 (10,200 kg ha

-1;

Table S16). These studies suggest that compared to no till and strip tillage, tilling and adding manure and/or SU contributes to higher yields.

For the 2017 to 2023 period, the grain yields of TDMSU were higher than those of NT202 in four of the seven years (2017, 2020, 2021, and 2023; P<0.05,

Table S23), suggesting an advantage of TDMSU over the NT202 plots. These studies suggest that compared to NT202, tilling and manure application with SU contributes to higher yields. The NT202 did not have higher yields than the TDMSU in any of the seven years. For the 2017 to 2019 period, the yields of TDMSU were higher than those of ST202 in two of the three years (2017 and 2019; P<0.05,

Table S24), suggesting an advantage of TDMSU over the ST202 plots. These studies suggest that compared to ST202, tilling and manure application with SU contributes to higher yields. The ST202 did not have higher yields than TDMSU in any of the seven years.

These results are agreement with studies at this site that found that cultivation contributed to higher yields than no till from 2001 to 2007 [

23]. These plots, which had been under no tillage since 2000 and were found to have lower yields than cultivated plots support the conclusions of other studies that have found that grain yields of NT start to decrease compared to cultivated systems [

21,

22,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39]. This result shows that after almost two decades of NT, the average yield is lower compared to cultivated systems (P<0.05,

Tables S11, S13, S14, and S15). Additionally, on average cultivated systems had higher yields than strip till systems (P<0.05,

Tables S12, S16, S17, and S18). Our assessment comparing NT and ST found that there were no differences between long-term no till and long-term strip till from 2012 to 2019, which aligns with findings from Delgado et al. [

7] (P<0.05; Table 19).

3.6. Harvested Grain N Content from 2012 to 2023: TDM and TSU vs. NT and ST

The TDM achieved greater grain yield N content than the NT202 treatment in 2014 and 2021 and was also higher than ST202 in 2014 and 2017 (P<0.05,

Tables S11 and S12). The ST202 treatment had greater grain N than TDM in the year that there was not a manure application (P<0.05,

Table S12). The data suggest that average grain N for manure is higher with TDM than the NT202 and ST202 treatments (P<0.05,

Tables S11 and S12).

For the 2012 to 2020 period, the grain yield N content of TUF was higher than the grain N of NT202 in 2013, 2015, and 2017 (P<0.05,

Table S13), suggesting an advantage of the TUF over the NT202 plots. The grain N was not higher with NT202 than TUF in any of the 9 years (P<0.05,

Table S13). For the 2012 to 2019 period, the grain N of TUF was higher than the grain N of ST202 in 2017, 2018, and 2019 (P<0.05,

Table S17), suggesting an advantage of the TUF over the ST202 plots. These studies suggest that compared to ST202, tillage and UF application contributes to higher grain N. The grain N was not higher with NT202 than TUF in any of the 8 years.

For the 2012 to 2016 period, the grain yield N content of TDMAP was higher than that of NT202 in 2013 and 2014 (P<0.05,

Table S4), suggesting an advantage of TDMAP over NT202, and that tillage and manure contributes to higher grain N. The grain N was not higher with NT202 than TDMAP in any of the 4 years, including 2016 when manure was not applied. For the 2012 to 2016 period, the grain N of TDMAP was higher than that of ST202 in 2014 (P<0.05,

Table S18), suggesting an advantage of TDMAP over the ST202. The ST202 treatment had higher grain N than TDMAP only in 2016, the year that the manure was not applied to the TDMAP plots (P<0.05,

Table S18).

For the 2017 to 2022 period, the grain N of TDMSU was higher than that of NT202 in four of the six years (2017, 2019 to 2021; P<0.05,

Table S23), suggesting an advantage of TDMSU over the NT202 plots. These studies suggest that compared to NT202, tilling and manure application with SU contributes to higher grain N. The NT202 did not have higher grain N than TDMASU in any of the six years. For the 2017 to 2019 period, the grain N of TDMSU was higher than that of ST202 in all years (P<0.05,

Table S24), suggesting an advantage of TDMSU over the ST202 plots. These studies suggest that compared to ST202, tilling and manure application with SU contributes to higher grain N. The ST202 did not have higher grain N than TDMASU in any of the seven years.

3.8. Summary of Agronomic Production System Results from 2012 to 2023

Analysis of the effects of organic and inorganic N inputs on aboveground biomass production at silage (R5), physiological maturity (R6), and harvest of grain shows that during the first 8 years of the 2012 to 2023 period (excluding 2016, when no manure was applied), the grain yield of TDM was higher than that of TUF in only one year (2014). However, from 2020 to 2023, there were significantly higher yields with the manure treatments than the inorganic N fertilizer treatments. Significant agronomic yield increases were found in 2020 for aboveground biomass at R6 (DMSU > SU); in 2021 for biomass at R6 (DMSU > SU); in 2022 for biomass at R6 (DMSU >SU) and silage yields (DMSU and DM > SU); and in 2023 for grain yield (DMSU and DM > SU). These results suggest that there is a synergistic effect when DM is applied with SU, contributing to higher aboveground biomass production and harvested yields than DM or SU alone.

Table 6.

Differences in harvested grain yields of corn grown in an irrigated system among different tillage management systems receiving zero N fertilizer input (control) from 2012 to 2023¥ β.

Table 6.

Differences in harvested grain yields of corn grown in an irrigated system among different tillage management systems receiving zero N fertilizer input (control) from 2012 to 2023¥ β.

| Year$ |

TC0N |

NTC0N |

SNTC0N |

| ----------------------------------------------- kg dry weight ha-1 -------------------------------------------------- |

| 2012 |

6589 a |

4789 b |

4160 b |

| 2013 |

9256 a |

5694 b |

5851 b |

| 2014 |

7879 a |

4952 b . |

5057 b. |

| 2015 |

6256 a |

5989 a |

5668 a |

| 2016 |

6129a |

4906 b |

5815 ab |

| 2017 |

6739 a |

5359 b |

5965 b |

| 2018 |

7099 a |

5158 a |

5727 ba |

| 2019 |

5842 a |

3959 b |

5126 ab |

| 2020 |

6565 a |

4175 a |

NA |

| 2021 |

8408 a |

6346 b |

NA |

| 2022 |

5220 a |

4054 a |

NA |

| 2023 |

6473 a |

4640 b |

NA |

Tilled systems receiving manure applications at this site with minimal erosion and irrigated with an aboveground sprinkler had higher agronomic productivity for continuous corn than tilled systems that received inorganic N fertilizer applications. When long-term comparisons of the manure systems with tillage were compared to long-term NT and ST systems that were receiving inorganic N fertilizer, tilled systems with manure applications had the advantage in agronomic productivity. Similarly, when the long-term inorganic systems that received inorganic N fertilizer as an input were compared to the long-term NT and ST systems, tilled systems receiving inorganic N fertilizer had an advantage over NT and ST systems receiving inorganic N fertilizer.

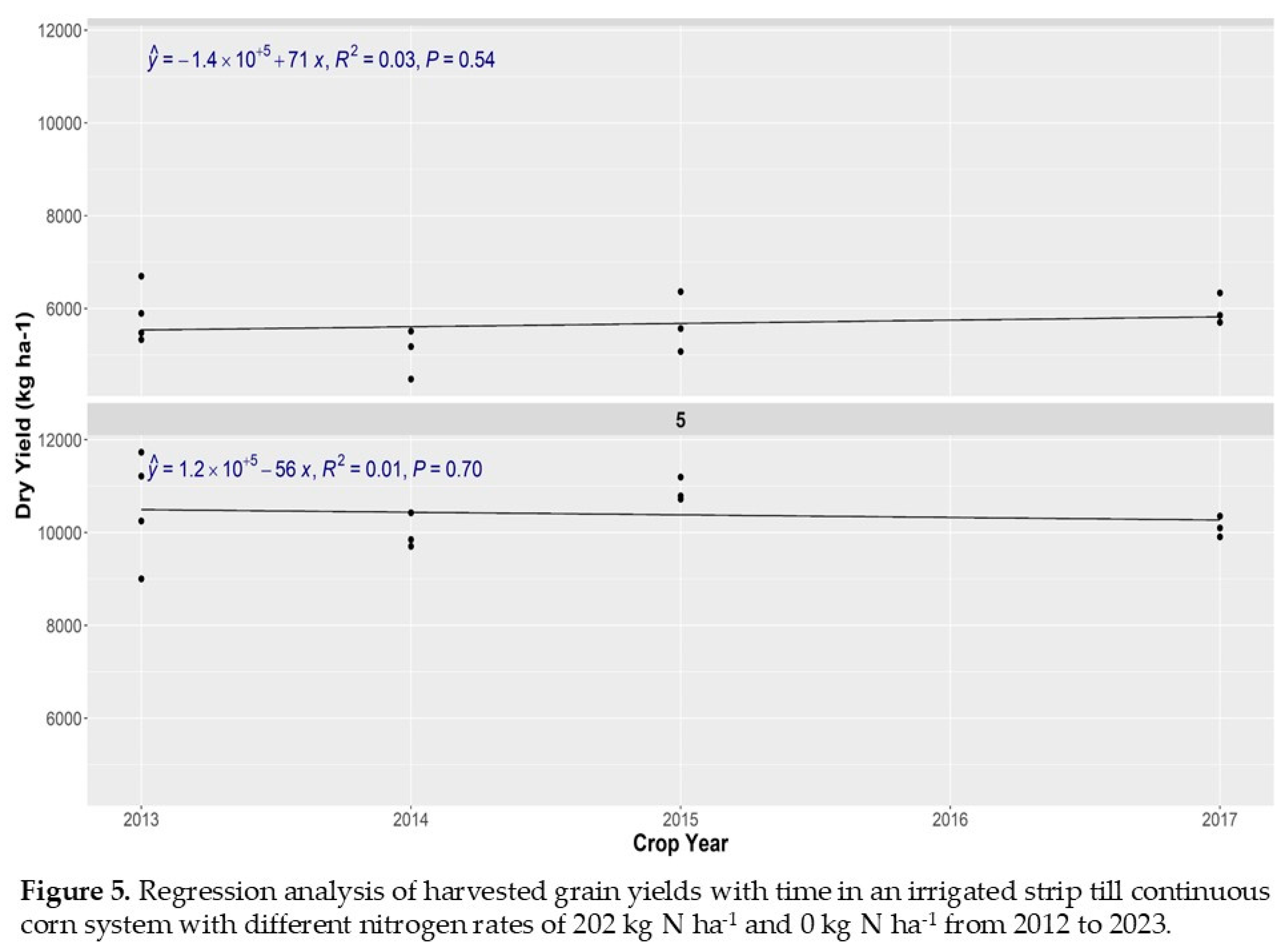

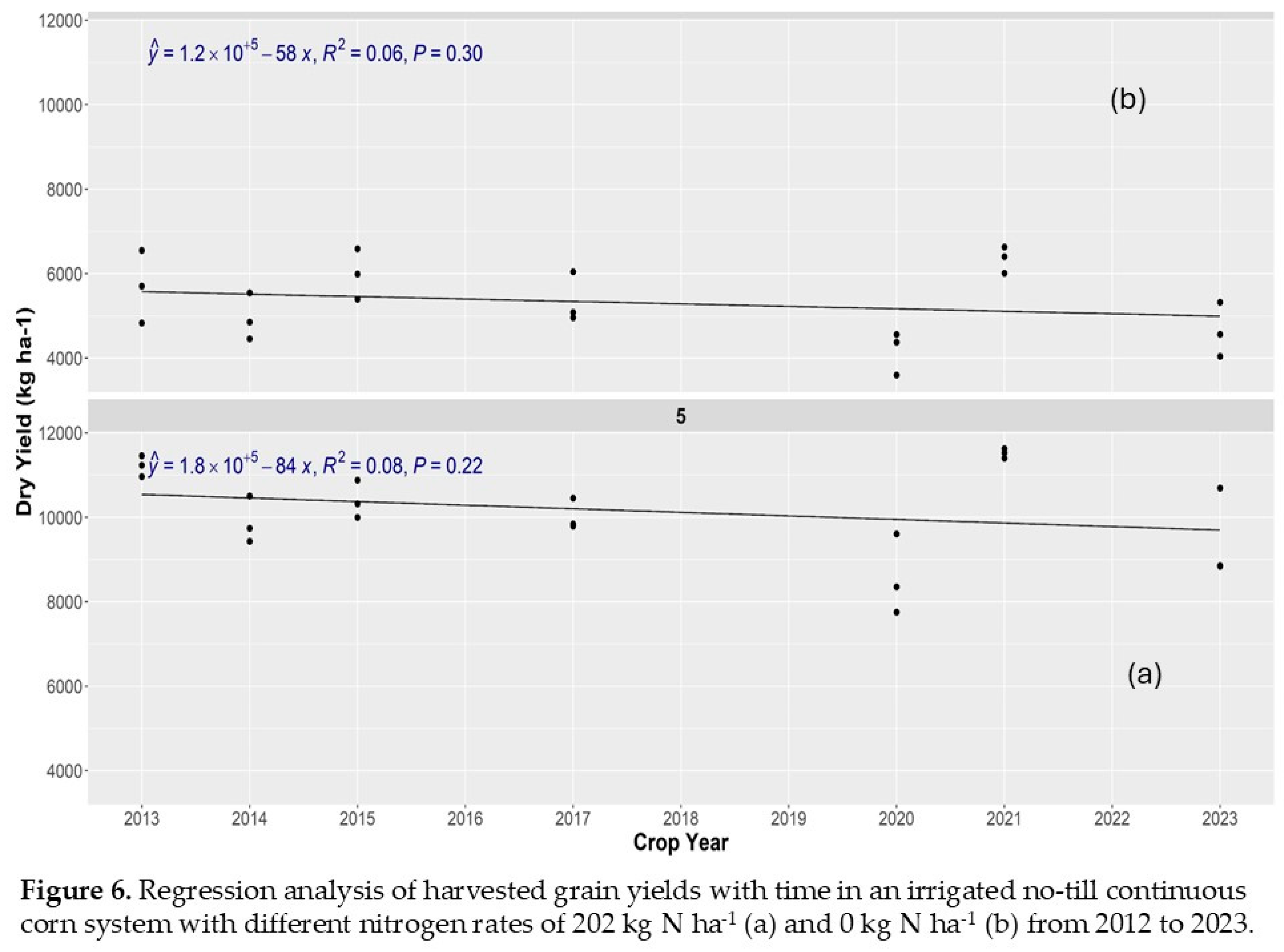

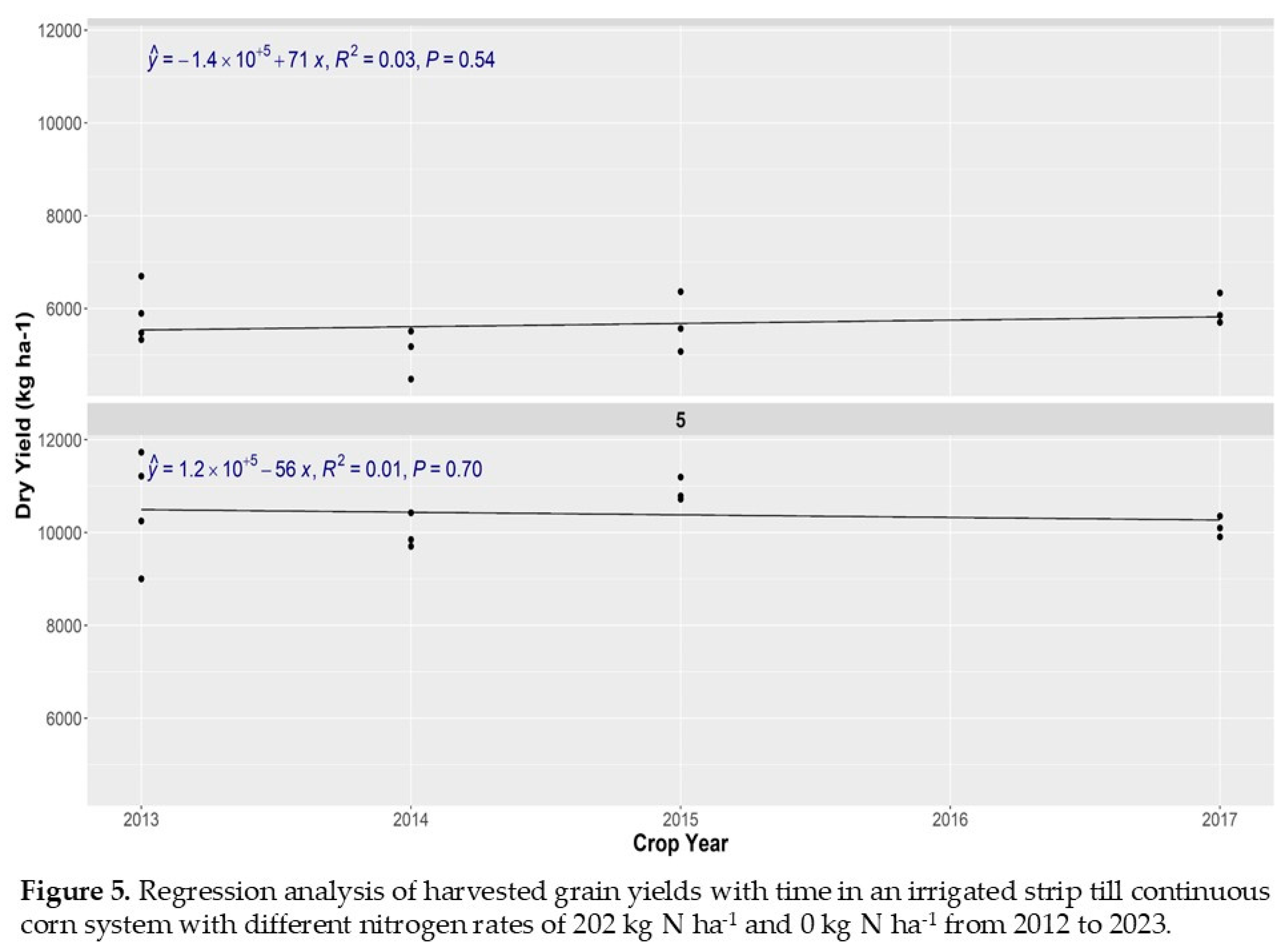

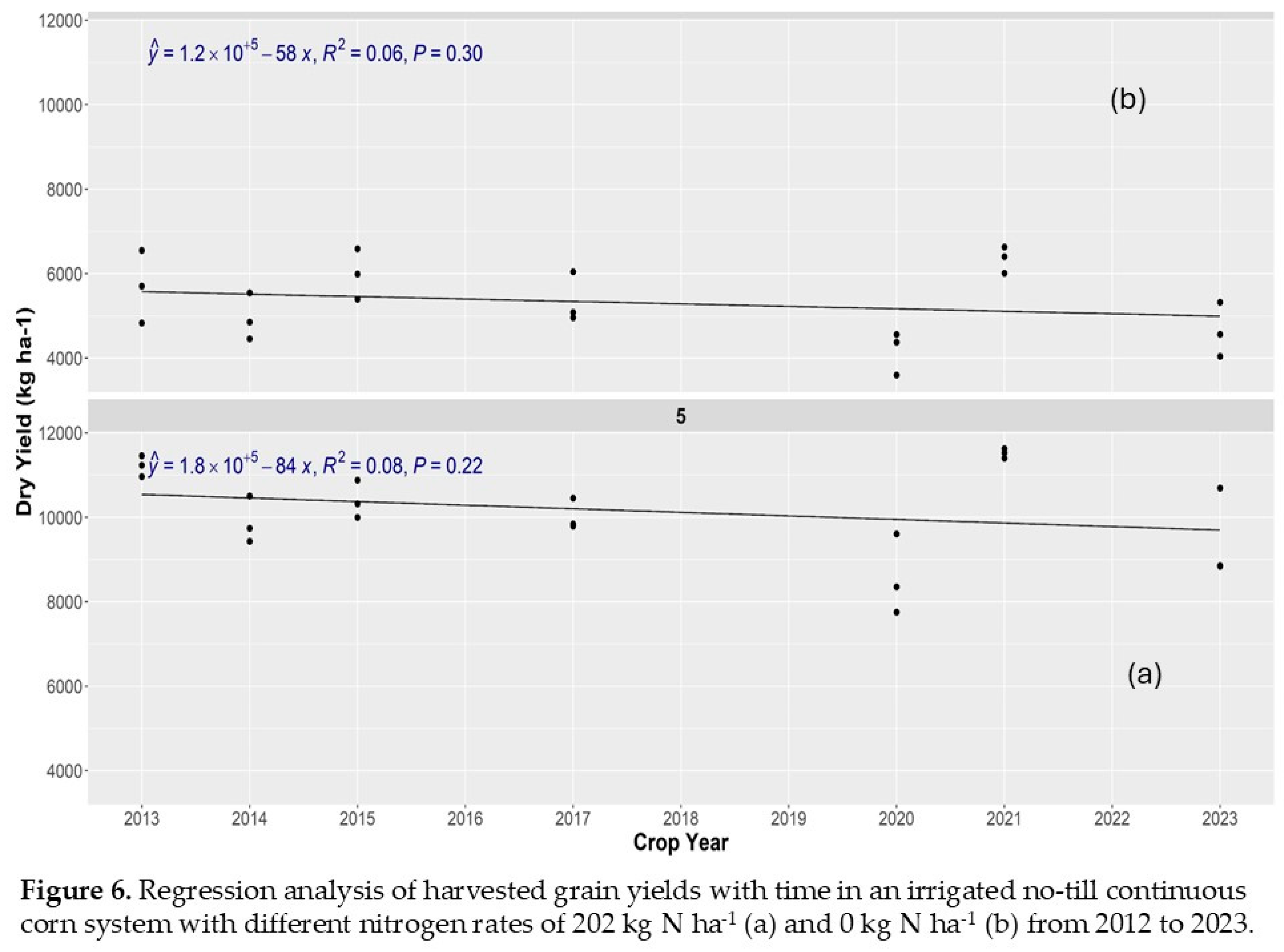

We conducted a long-term analysis of the harvested yields with time. Regarding agronomic sustainability, our findings were that the yields of the manure treatments were stable with time and/or were increasing when compared to the yields of the inorganic-N-fertilized treatments, which were decreasing with time (Figs 4). We similarly found that the conservation agriculture practices of NT and ST with 202 kg N ha

-1 of inorganic fertilizer had stable harvested grain yields that were not decreasing with time. In a previous work we had found that climate change is occurring in Fort Collins and that irrigation is a practice to adapt to climate change [

7]; however, the yields were not changing with time. In the present work, which monitored long-term yields of manure and inorganic N systems under tillage and NT and ST, we found that agronomic sustainability was highest for tilled systems receiving manure, followed by NT and ST systems receiving inorganic N, and lowest for tilled systems receiving inorganic N (Figs 5, 6). Regarding yield productivity, we found that tilled systems receiving manure outperformed tilled inorganic N systems, which outperformed NT and ST. We found that although tilled systems receiving inorganic N currently have higher yields, if the agronomic productivity continues to decrease with time, NT and ST systems receiving inorganic N may become more comparable to tilled systems receiving inorganic N in the long term.

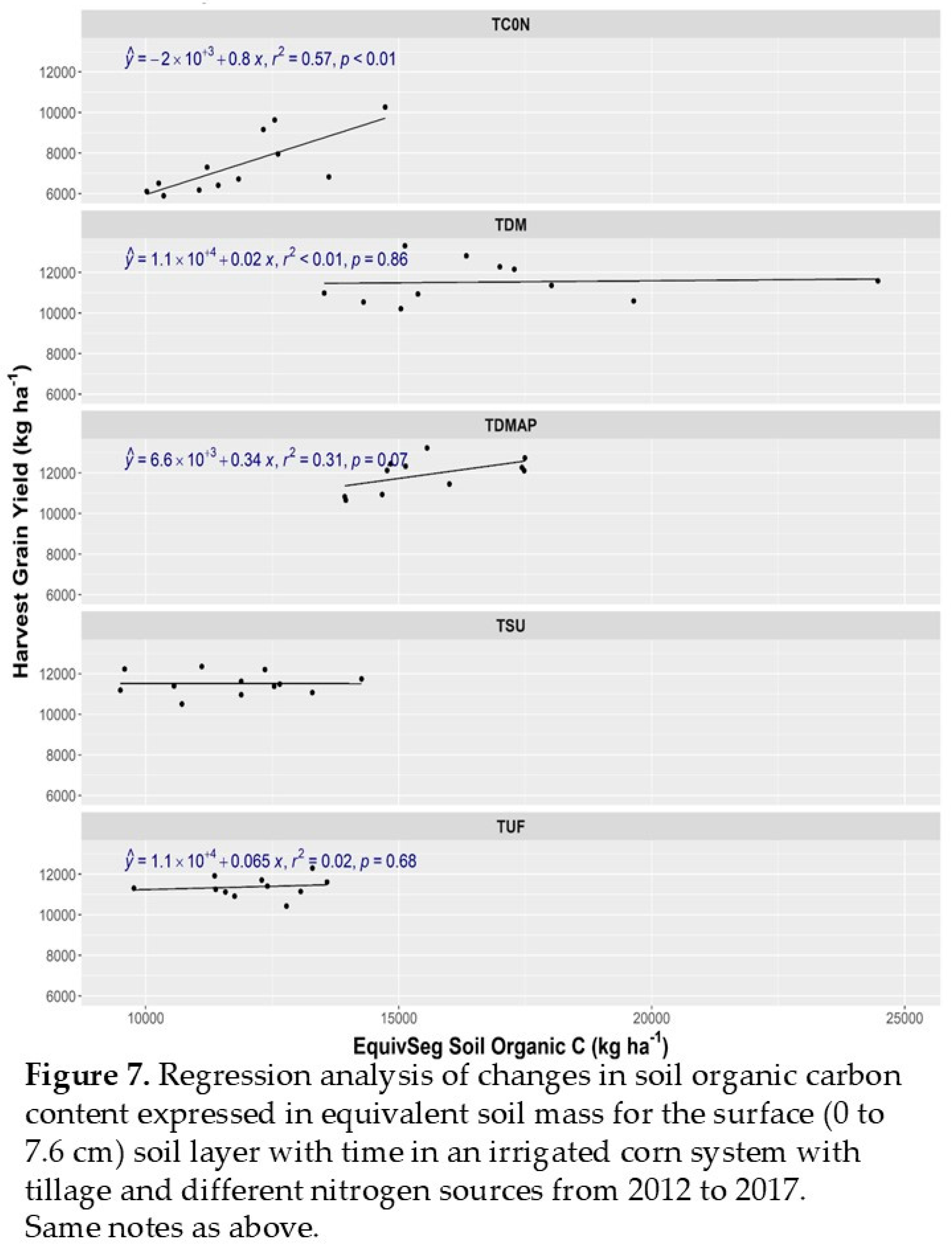

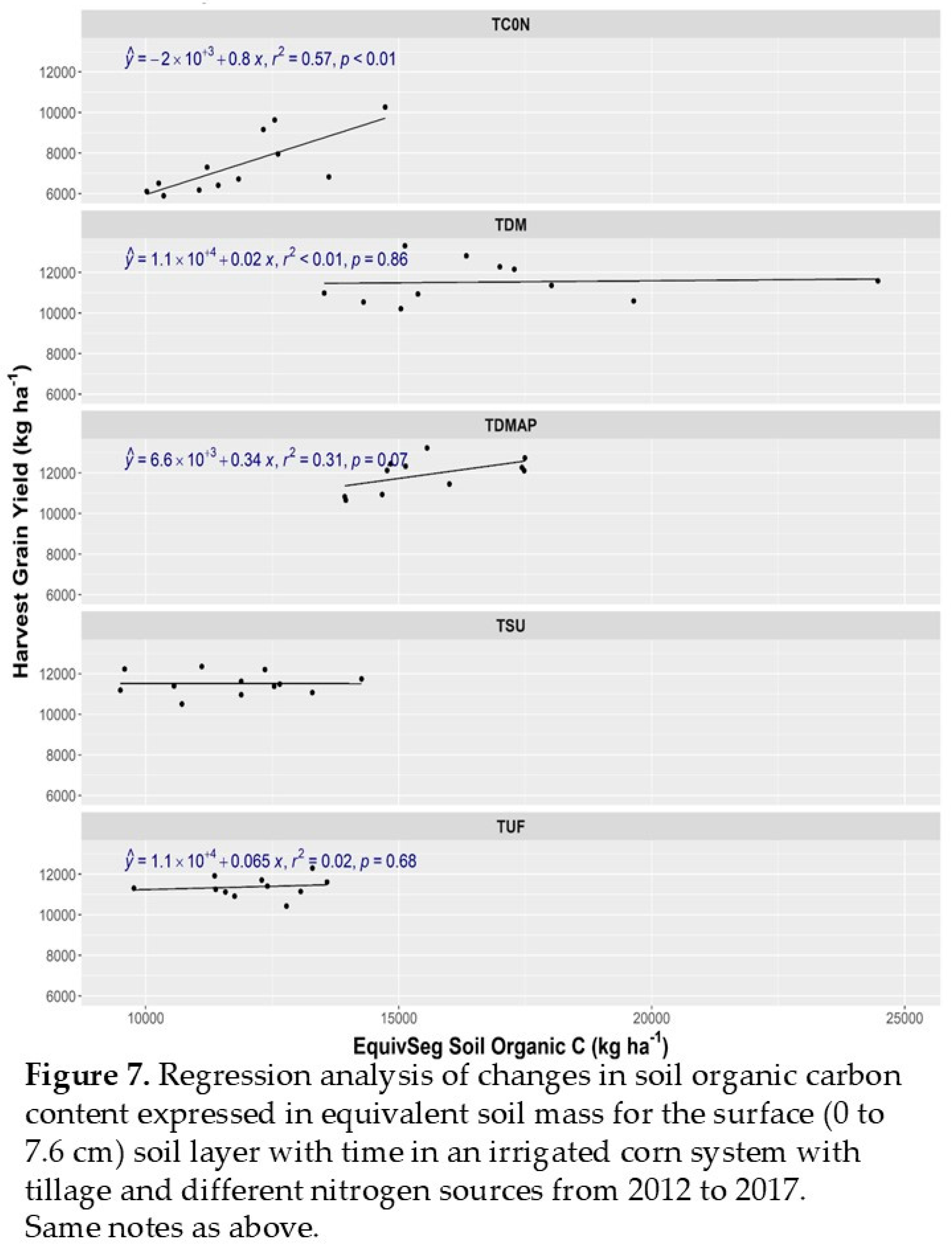

We suggest that one of the reasons for these findings related to agronomic productivity and sustainability with time could be the positive relationships between yields and soil organic C content in the surface soil (Figure 7). As far as agronomic sustainability, the tilled systems receiving manure applications had increased soil organic C and N content. While the tilled systems with manure applications were sequestering C and N in the soil organic matter pool, the tilled systems with inorganic N fertilizer were losing organic C and organic N (Figs. 2, 3). The N cycled from manure applications from current and previous years is significant and contributed to higher N uptake by aboveground biomass (R5.5 and R6) and harvested grain. These desirable increases in N cycling are contributing to higher NUE for the manure systems than the inorganic N fertilizer systems with a tillage system. The mobility of N in the NO

3-N pool was higher with the inorganic N fertilizer systems than with the manure systems, and more changes were detected at lower depths with the inorganic N fertilizer systems. These desirable changes in soil health properties such as C sequestration, greater cycling of N, higher system N use efficiencies, and lower N losses are contributing to increased yields and greater yield stability (with no decrease in yields with time) compared to tilled systems receiving inorganic N fertilizer, which are seeing decreasing yields with time (Figure 4). Independently of these effects, the inorganic systems under tillage have higher agronomic productivity as far as grain yield than NT and ST systems (

Table 5,

Table 6). Although application of manure was identified as a good agronomic management practice to increase yields and sustain productivity with time, the best combination appears to be the enhanced efficiency fertilizer (70% of N input) with manure organic N (30% of N input), a combination which appears to have a synergistic effect that increases agronomic productivity (

Table 5).