1. Introduction

The exploration of bimetallic Fe-Pt alloys has long garnered significant attention due to their intriguing properties and promising applications in various fields such as ultra-high density data storage, spintronics, catalysis, and nanotechnology [1, 2, 3, 4]. As indicated by their binary stability phase diagram [5], there have been three well-known and widely reported structures of Fe-Pt alloys which are chemically ordered. These include the tetragonal L10 -FePt phase which exhibits ferromagnetic ordering, and the face-centered cubic (FCC) phases FePt3 and Fe3Pt, both crystallizing in the space group with L12-type crystal symmetry. The latter two phases support both antiferromagnetic and ferromagnetic magnetic ordering [6]. These alloys have been previously investigated both experimentally and computationally and have been found to exhibit excellent thermodynamic, vibrational and mechanical stability. Moreover, they possess desirable magnetic properties due to large magnetic moments, large uniaxial magnetocrystalline anisotropy (MCA) energies originating from spin-orbit interactions and asymmetry of spin up and down in the electronic density of states [7, 8, 9]. Variations in crystallization and chemical composition significantly influence their magnetic behavior, electronic structure, and lattice dynamics. For instance, although both Fe and Pt contribute to the magnetic moments, Fe contributes approximately eight times more than Pt, thereby making the magnetic behavior predominantly dependent on the Fe content [10]. The -FePt phase crystallizes at temperatures below 1570 K in equiatomic Fe:Pt concentration, while the FCC structures crystallize around 25 % and 75 % Fe contents at temperatures below 1120 K and 1620 K, respectively [11]. The tetragonal L10 FePt shows one of the highest MCA energy ranging from to along the magnetically easy axis [001], making it a promising candidate to overcome superparamagnetic limit, which is the loss data due to thermally activated fluctuations of magnetization [12, 13]. It consists of alternating stacked atomic layers of Fe and Pt atoms along [100] direction similar to the AuCu structure, leading to a tetragonal distortion along the -axis. As per the previous communication, the cubic Fe3Pt and FePt3 alloys exhibit the highest MCA energies of (0.375 meV) and (0.055 meV) along the [100] easy axis [12]. In the Fe-rich Fe3Pt alloy, Fe atoms occupy the corner lattice positions, while Pt atoms are located at face-centered positions. Conversely, in the Pt-rich FePt3 alloy, Pt atoms occupy the corner positions, and Fe atoms are situated at the face-centered positions.

In addition, the L12 face-centered cubic (austenitic) Fe3Pt alloy is reported to exhibit strong magnetoelastic coupling and undergoes a thermoelastic martensitic transformation from the ordered L1₂ phase into low-temperature martensitic structures, which inherently depend on the degree of order of the L12 structure [14, 15]. One such martensite structure is the body-centered tetragonal (BCT) Fe3Pt phase, which crystallizes in the I4/mmm space group [16, 17]. The equilibrium cell parameters of the I4/mmm bulk structure as produced by X-ray diffraction are and [18]. It was found that the spin up Fe states in the density of states (DOS) in this martensite structure are situated below the Fermi level, while the spin down states overlaps above the Fermi, indicating a pronounced spin asymmetry. Consequently, this spin polarization results in relatively large magnetic moments of 2.61 and 2.82 for Fe1 and Fe2 atoms, respectively. Moreover, Pt atoms were also found to exhibit a finite magnetic moment of 0.45 , suggesting a degree of spin polarization induced by hybridization with neighboring Fe atoms [16]. Our previous communication further reported magnetic moments of 2.744 for Fe and 0.45 Pt along with the MCA energy of 1.364 meV along the [001] easy axis [12], which are higher than those of the austenitic Fe3Pt.

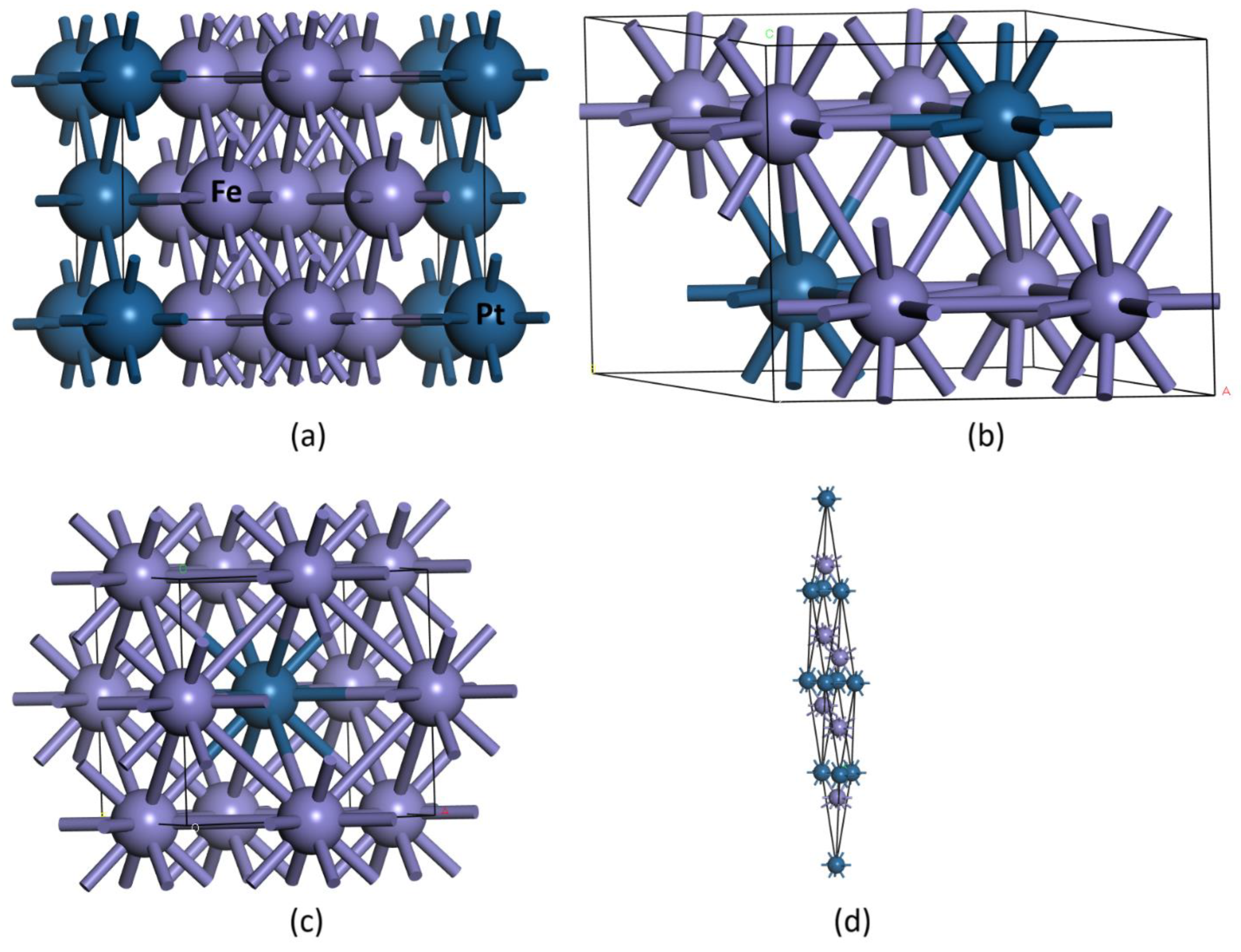

The structural models of other Fe

3Pt martensite phases have long been proposed, however, their properties remain unstudied [19]. According to the Materials Explorer within the Materials Project database [20, 21], three additional martensitic phases of Fe

3Pt are predicted to exist whose structural, thermodynamic, magnetic and mechanical properties are not yet fully explored. These correspond to the

P4/mmm,

, and

R3m space groups as shown in

Figure 1. The

–Fe

3Pt phase crystallizes at approximately 55 K in an orthorhombic lattice characterized by primitive lattice parameters

as determined by XRD. The structure comprises two crystallographically distinct Fe sites. This orthorhombic structure is an intermediate phase, appearing between face-centered tetragonal (FCT1) (

) and FCT2 (

) [15]. The system considered in this current work is a conventional

-centered (centering doubles the number of lattice points along one direction) orthorhombic Fe

3Pt which is equivalent, but twice the volume and number of atoms (eight) as the primitive (four atoms) reported in literature. In the first site, Fe atoms adopt a two-coordinate geometry, bonded to two Fe and two Pt atoms, whereas the second Fe site exhibits eightfold coordination with neighboring Fe atoms. The Pt atoms display a four-coordinate geometry, each bonded to four Fe atoms, completing the orthorhombic network. The

–Fe

3Pt phase exhibits a USi

2-type structure and crystallizes in a body centered tetragonal (BCT) lattice. This phase forms through a thermoelastic transformation. During the formation, the tetragonality ratio

shifts from 1 to 0.79 at the transformation temperature, signifying a discontinuous lattice distortion characteristic of a first-order martensitic transformation [15, 17]. The structure contains two inequivalent Fe sites. Each Fe atom is coordinated by eight Fe and four Pt atoms, forming distorted FeFe

8Pt

4 cuboctahedra. These polyhedra interconnect through corner-, edge-, and face-sharing with neighboring FeFe

8Pt

4 and PtFe

12 units, forming a highly integrated three-dimensional framework. The Pt atoms are twelvefold coordinated by Fe atoms, generating PtFe

12 cuboctahedra that are similarly interconnected through shared corners, edges, and faces with surrounding FeFe

8Pt

4 polyhedra. The

–Fe

3Pt phase crystallizes in a rhombohedral centered hexagonal or trigonal lattice. Each Fe atom is surrounded by nine Fe and three Pt atoms, forming distorted FeFe

9Pt

3 cuboctahedra that share corners, edges, and faces with adjacent FeFe

9Pt

3 and PtFe

6Pt

6 polyhedra. The Pt atoms are coordinated by six Fe and six Pt atoms, creating PtFe

6Pt

6 cuboctahedra that link through corner-, edge-, and face-sharing, producing a robust trigonal framework. Lastly, the

-Mn

3Ir structure served as a prototype for Fe

3Pt, since Fe and Mn as well as Pt and Ir are chemically analogous neighboring transition metals with comparable atomic radii and electronic configurations. Such substitution preserves the symmetry and coordination environment, enabling reliable DFT modeling of synthetical Fe–Pt system within the same crystallographic framework. This is beta Cu

3Ti and Mn

3Ga type structure which crystallizes in the hexagonal lattice with eight atoms in a primitive cell [22, 23]. Fe is bonded to four equivalent Pt atoms to form a mixture of distorted corner, edge, and face-sharing FePt

4 cuboctahedra. Pt is bonded to twelve equivalent Fe atoms to form a mixture of corner and face-sharing PtFe

12 cuboctahedra.

The magnetic, thermodynamic and mechanical properties of these four martensite phases are yet to be systematically explored either experimentally or theoretically, which limits a comprehensive understanding of the structure–property relationships and the potential functional applicability in advanced magnetic and electronic technologies. Experimental exploration of these alloys may be challenging due to the complexities associated with detecting such phases arising from dynamical effects on diffraction reflections [16]. However, the development of density functional theory (DFT)-based first-principles methods enables theoretical exploration and optimization of L12 bimetallic alloys by accurately calculating the interatomic forces acting on the nuclei [24, 25, 26]. The current study focuses on the structural, thermodynamic, magnetic, electronic and mechanical properties of the four martensite Fe3Pt bimetallic alloys at 0K to assess their stability and deduce their suitability as magnetic materials. We have employed the density functional theory (DFT) quantum mechanical method embedded in the CASTEP code to perform first-principles quantum mechanical calculations on Fe3Pt alloys. Our computational findings revealed that three martensite Fe3Pt alloys exhibit excellent thermodynamic and mechanical stability and magnetic moments comparable to those of the extensively studied Fe-Pt alloys.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Structural Properties

The equilibrium cell parameters, densities and enthalpies of formation of the four martensite Fe

3Pt structure as shown in

Table 1 were obtained by performing full geometry optimization. The experimental volume for the orthorhombic

-Fe

3Pt and lattice parameters of the previously reported austenitic

-Fe

3Pt are given in parenthesis to validate DFT calculations against existing experimental data. The calculated lattice parameters of

-Fe

3Pt are more than 99 % in agreement with experimental data [34] and previous calculations [8], while the optimized volume of

-Fe

3Pt in 96 % in agreement with the XRD results [15]. These agreements indicate that the employed approach correctly predicts the ground state properties of Fe

3Pt alloys. The conventional hexagonal

-Fe

3Pt structure shows the largest unit cell volume and smallest density corresponding to weaker interatomic interactions. The enthalpies of formation (

) were computed according to equation 1,

where

is the total ground state energy of Fe

3Pt formula unit and

the elemental energies of Fe and Pt atoms. Negative enthalpies of formation indicate the release of energy when forming a compound (exothermic reaction) and thus thermodynamic stability of the compounds in relation to its constituent elements, i.e.

. Our DFT calculations predict that all the four martensite Fe

3Pt alloys are thermodynamically stable due to negative enthalpies of formation. Expectedly, the enthalpy of formation values of austenitic

and martensite

,

,

and

are similar since they have the same stoichiometry and elemental reference state.

3.2. Magnetic Properties

Table 2 presents the calculated spin polarized magnetic moments and charge distribution characteristics of the four considered Fe

3Pt crystal structures derived from Mulliken atomic population analysis. The magnetic moments are calculated as the difference between spin up and spin down (

) charge densities. Moreover, the average of Fe1 and Fe2 were taken when quantifying the total spin moment per formula unit. The calculated total moments for

,

,

and

are 3.01

, 3.04

, 2.94

and 2.97

, respectively. These values are comparable with those reported for other Fe-Pt alloys and bimetallic systems of similar composition [10, 35, 36]. For all space groups, the Fe atoms exhibit substantial local magnetic moments compared to Pt, indicative of strong ferromagnetic ordering within the Fe sublattice and large spin–orbit effects from Pt. Moreover, in all the structures, the spin up (

) for both Fe1 and Fe2 are more densely than the spin down (

) revealing pronounced spin asymmetry in the electronic density of states and confirming strong magnetic polarization within the system.

Our DFT calculations reveal that the orthorhombic space group possesses the largest Fe1 magnetic moment (2.98 ), followed by the hexagonal (), while the trigonal and tetragonal display relatively decreased moment values of 2.87 and 2.83 , respectively. This may be attributed to the increase of restrictions on independent lattice parameters and angles, i.e. symmetry from orthorhombic to tetragonal, which slightly decreases the exchange splitting, consistent with increased Fe–Pt orbital hybridization. The smaller variation in Fe2 moments indicates comparable local environments across the structures, except for the P6₃/mmc phase, where Fe occupies only one unique crystallographic site due to higher symmetry. The Pt atoms exhibit relatively small induced magnetic moments, ranging from 0.12 to 0.30 , arising from Fe–Pt hybridisation and spin polarization of Pt 5d orbitals. -Fe3Pt shows the largest Pt moment (0.30 ), whereas the phase displays the smallest (0.12 ).

The Hirshfeld partitioning of electron density into atomic contributions further confirms the dominance of Fe atoms in the overall magnetic behavior. The Fe1 moments range from 2.72 to 2.83 , while Fe2 moments vary between 2.45 to 2.68 In contrast, Pt contributes only 0.35-0.57 , consistent with the induced magnetization mechanism. The structure again exhibits the highest overall Fe magnetization, while the phase shows a marginally reduced value, reflecting differences in local coordination and exchange interactions.

Hirshfeld charge analysis indicates notable charge redistribution between Fe and Pt atoms. Fe atoms possess positive charges (+0.07 to +0.27 e), signifying electron donation, while Pt atoms carry negative charges (−0.46 to −0.79 e), confirming their role as electron acceptors. The phase shows the highest charge transfer (-0.79 e), suggesting stronger Fe–Pt bonding and more effective hybridization.

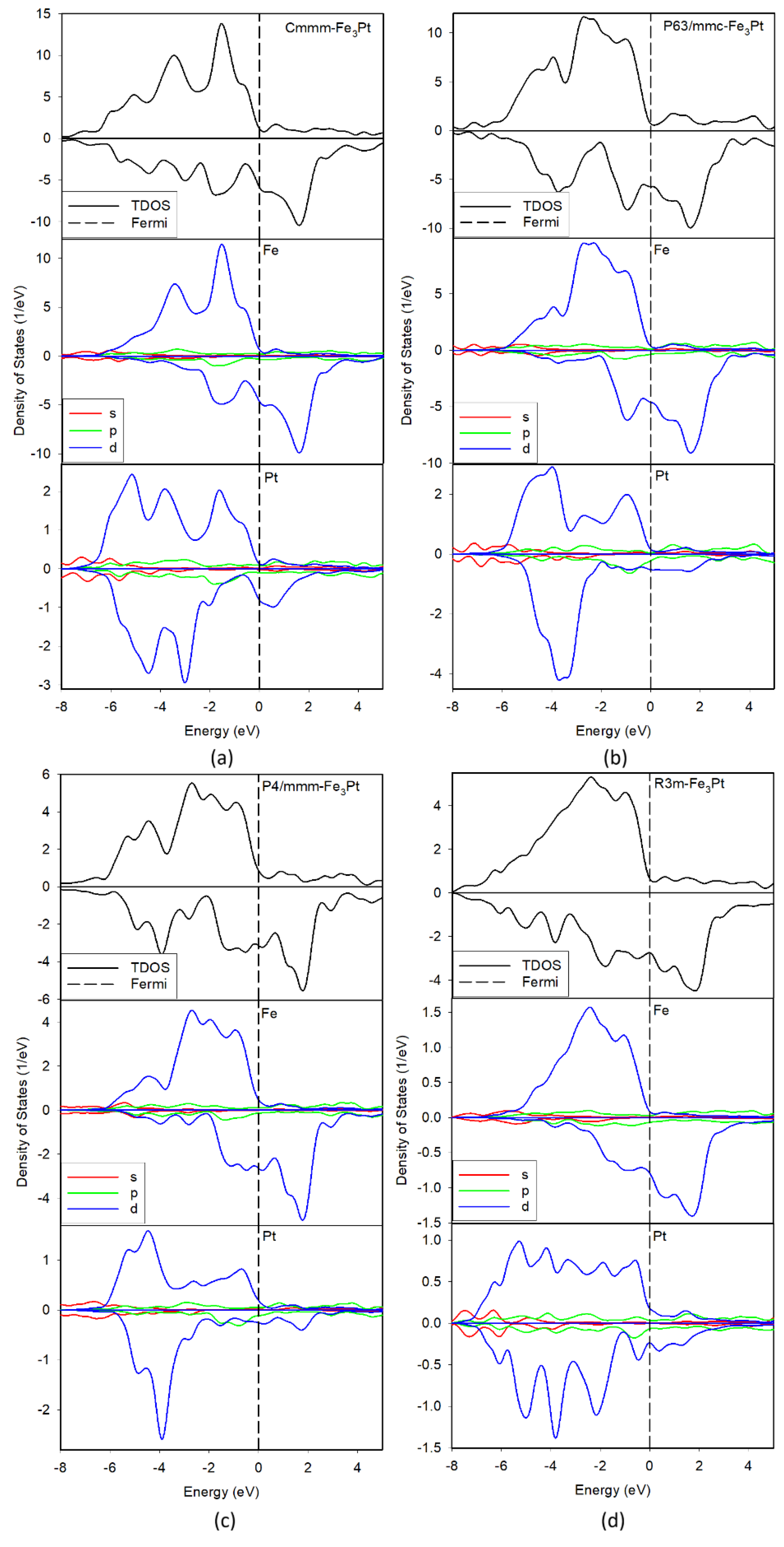

3.3. Electronic Structure

Figure 2 presents the electronic total and orbital-projected spin polarized density of states (DOS) for the martensitic Fe

3Pt, with the Fermi level set as the origin of the energy scale. As anticipated, all the investigated Fe

3Pt alloys display metallic behavior, as indicated by the finite density of states at the Fermi level arising from the overlap of valence and conduction bands, most prominently in the spin-down states. In all total DOS plots, the spin-up states are predominantly located below the Fermi level, whereas the spin-down states extend into the conduction band above the Fermi level, reflecting a pronounced spin asymmetry which indicates spin polarization and gives rise to substantial magnetic moments and strong ferromagnetic character consistent with previous experimental findings on Fe

3Pt thin films [37]. Notably, the

phase exhibits a further strong asymmetry (enhanced spin polarization) in the valence states between −4 eV and −2 eV, consistent with its highest calculated magnetic moment. There exist shallow pseudo-gaps near the Fermi level, indicating enhanced Fe-Pt hybridization and electronic stability for all phases.

The orbital-projected DOS shows a dominant contribution from Fe 3d states in the total plots, with minor contribution from the Pt 5d states hybridizing with Fe d-bands. Moreover, there exist strong spin asymmetry in Fe states and weaker in Pt. This strong exchange splitting reflects localized Fe moments stabilized by the low structural symmetry. Furthermore, the strong spin polarization arises from the Fe 3d orbitals, while Pt-5d orbitals show small but non-zero induced moments, contributing slightly to the total magnetization.

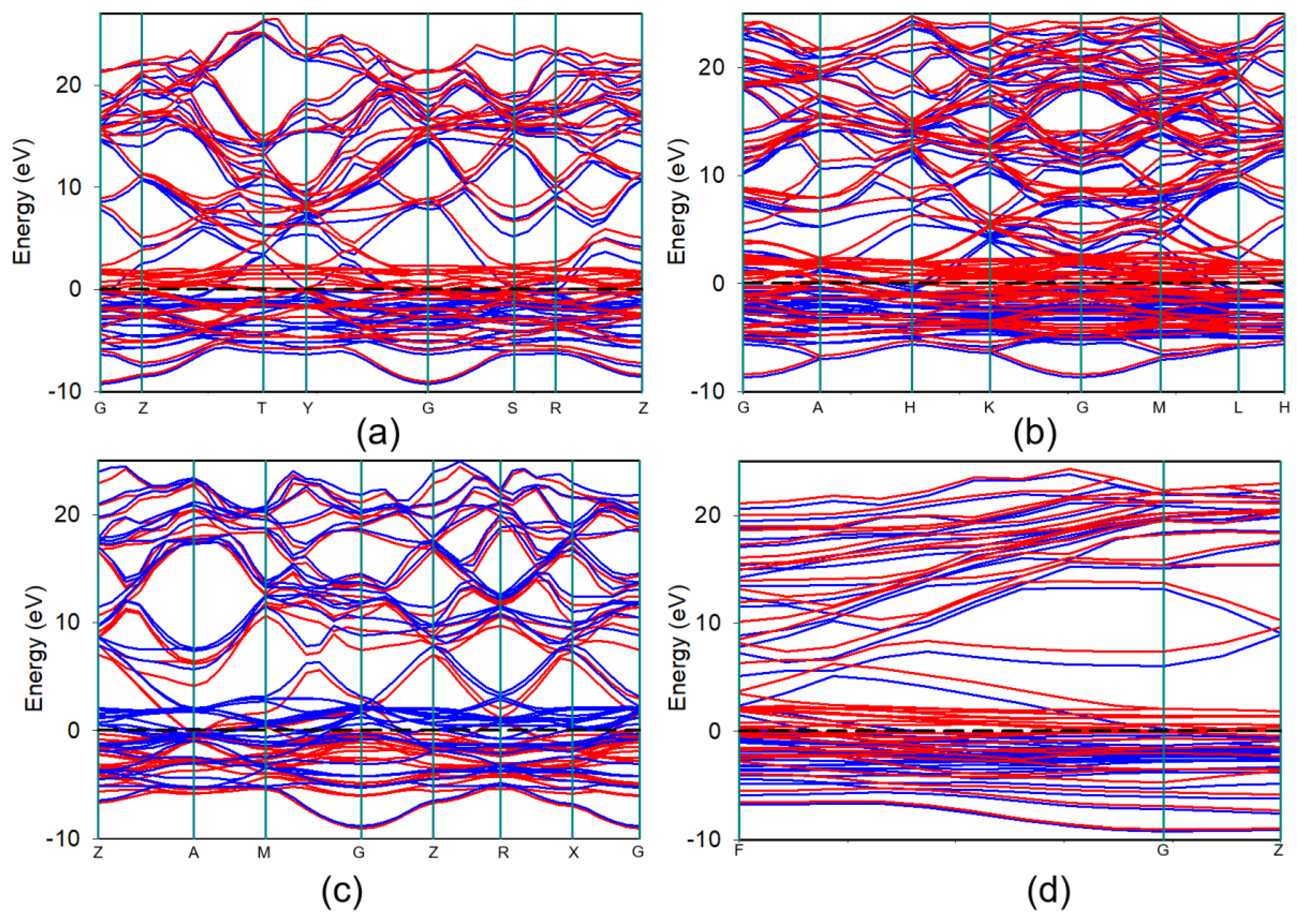

The electronic properties of these systems were further analyzed using the band structure along high symmetry direction in the Brillouin zone as presented in

Figure 3. All four structures exhibit metallic characteristics, as evidenced by the continuous overlap of energy bands at the Fermi level and the finite DOS at

and transitioning of electron wave highest to lowest energy levels through the Brillouin zone [38]. Moreover, there exists a clear spin splitting: red and blue bands diverge near the Fermi level. Interestingly, the

phase shows almost similar spin up (red) and spin down (blue) bands, indicating nearly degenerate spins.

3.4. Mechanical Properties

Table 3 shows the calculated independent elastic constants (

) and derived macroscopic properties of the orthorhombic, hexagonal, tetragonal and trigonal Fe

3Pt alloys at 0 K. CASTEP uses the generalized Hooke’s law shown in equation 2) to fit the linear relationship between stress and strain components in the elastic regime to compute the independent elastic constants.

where

and

are the Voigt notation components of the stress and strain tensor, respectively. Calculation and elastic constants and macroscopic mechanical properties are crucial in understanding the intrinsic mechanical stability, bonding nature and deformation behavior of solid-state materials. For any solid-state crystal lattice to be considered mechanically stable, certain stability conditions as postulated by Born must be satisfied [39].

Hexagonal crystals possess five independent elastic constants, while the tetragonal contain six due to the added

. Since the Laue classes of the hexagonal and tetragonal crystal lattice have similar elastic matric, their Born necessary stability conditions are also similar and are given as [40]:

The condition

is redundant for hexagonal crystal lattices. The trigonal or rhombohedral lattice has 6 independent elastic constants and like the hexagonal one

dependent. The following four conditions are sufficient for stability:

The orthorhombic crystal lattice with lower symmetry contains larger number (nine) independent elastic constants and the born stability conditions are:

The independent elastic constants of the orthorhombic , tetragonal and trigonal structures are positive and obey all the necessary Born stability conditions, which indicates mechanical stability. In contrast, the phase exhibits anomalous elastic constants, due to a negative value which violates the Born stability criteria. Such behavior signifies mechanical instability, suggesting that this hypothetical hexagonal structure cannot exist under ambient conditions and would spontaneously transform into a lower-symmetry, more stable phase with space group [11, 41]. The elastic stiffness coefficients , , and for the -Fe3Pt are relatively high, above 224.53 GPa, which signifies a strong resistance to axial deformation along all crystallographic directions. Furthermore, the off-diagonal and are also large, indicating considerable interplanar coupling, while the comparatively smaller shear constant (36.270 GPa) reveals moderate shear anisotropy. The -Fe3Pt structure shows moderately high values of and , indicating fair axial stiffness. However, its small value (12.11 GPa) reflects weak shear resistance, implying significant anisotropy in its mechanical response. The -Fe3Pt phase displays intermediate stiffness with and , while the relatively small off-diagonal value (5.36 GPa) indicates limited shear coupling.

The corresponding macroscopic mechanical properties representing a polycrystalline aggregate using Voigt–Reuss–Hill (VRH) averaging schemes were computed from the independent elastic constants to determined deformation characteristics [42].

Table 4 summarizes the expressions and descriptions of the calculated macroscopic properties.

The Pphase shows large bulk modulus and shear modulus further confirming its robustness and greater resistance to compression, while the relatively high Young’s modulus indicates good stiffness and metallic bonding characteristics. Moreover, the Pugh () ratio greater than the critical value 1.5 of ductility and brittleness and Poisson’s ratio () classifies this phase as ductile, while the positive anisotropy factor (A = 1.97) that diverge from unity suggests moderate elastic anisotropy.

The calculated Poisson’s ratio ranges from 0.33 to 0.40, except for are within the error limit (0.320.09) and similar to recorded in most alloys [11, 43]. Consistent with the negative , the hexagonal , shows a negative shear modulus and Pugh ration. Its Poisson ration is 0.76 which is beyond the metallic limit (~0.5), indicating that this phase exhibits extreme lateral expansion when compressed (or contraction when stretched), very high ductility, low shear resistance, and strong anisotropic bonding or magnetostrictive behavior. This phase likely reflects magnetoelastic softening, not purely mechanical elasticity. The bulk modulus (179.09 GPa) of the phase is relatively larger than the shear (38.75 GPa), leading and larger Pugh ratio, confirming a ductile but less rigid nature relative to the orthorhombic phase. The moderate Poisson’s ratio (0.40) also supports a metallic and ductile bonding character. Similar behavior is observed for the .

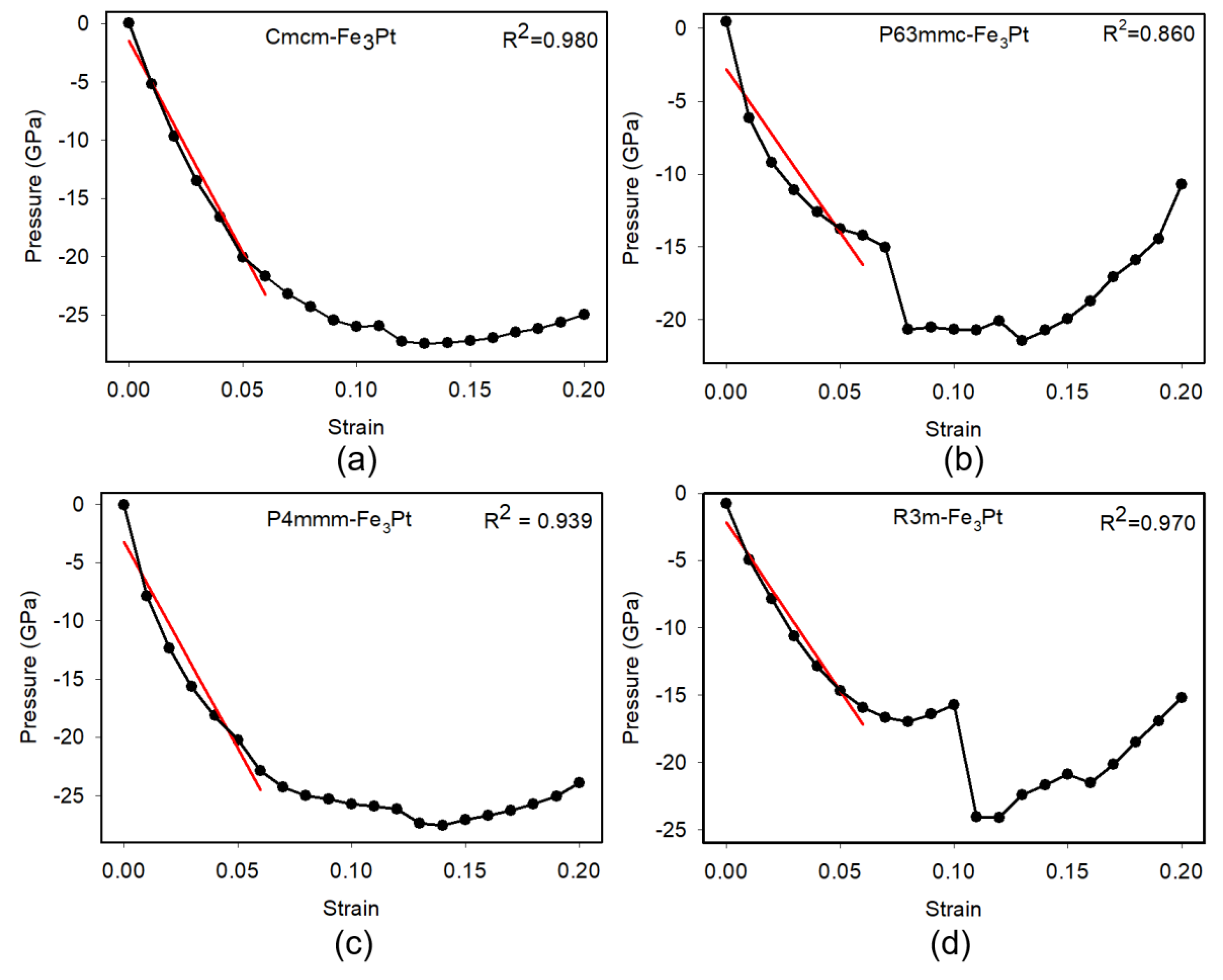

To further analyze the mechanical properties of the martensite Fe

3Pt alloys, we plotted stress vs strain profiles which represent the elastic response of crystal systems under applied strain, from which elastic constants and mechanical stability are evaluated.

Figure 4 illustrates the calculated stress vs strain relationships for the

,

,

, and

phases of Fe

3Pt. The

,

and

structures exhibit smooth and well-defined linear elastic regions, 0% ≤ Strain ≤ 10% (red line) with strong correlations between the fitted and computed data (

and 0.970, respectively). This excellent agreement confirms excellent elastic behavior, numerical accuracy, mechanical stability with the elastic regime and validates the reliability of the derived elastic constants. Conversely, the hypothetical

-Fe₃Pt phase displays a noticeable deviation from linearity even at small strains, reflected by a relatively low

. The irregular stress response suggests internal atomic relaxations or numerical instabilities during deformation, which consistent with the observed negative

elastic constant and shear modulus values. This behavior indicates that although predicted to be thermodynamically stable, the hypothetical

–Fe

3Pt phase is mechanically unstable and prone to soft-mode distortions under elastic perturbation. Therefore, the combination of stress vs strain analysis and correlation fitting provides a robust means of assessing the elastic consistency and mechanical resilience of crystal systems.