Submitted:

25 October 2025

Posted:

27 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Nutritional Value of Food Industry By-Products

3. Feedstuffs

4. Environmental Benefits

4.1. Greenhouse Gas Emission Reduction

4.2. Land and Water Use

4.3. Food Waste Mitigation

4.4. Circular Economy Integration

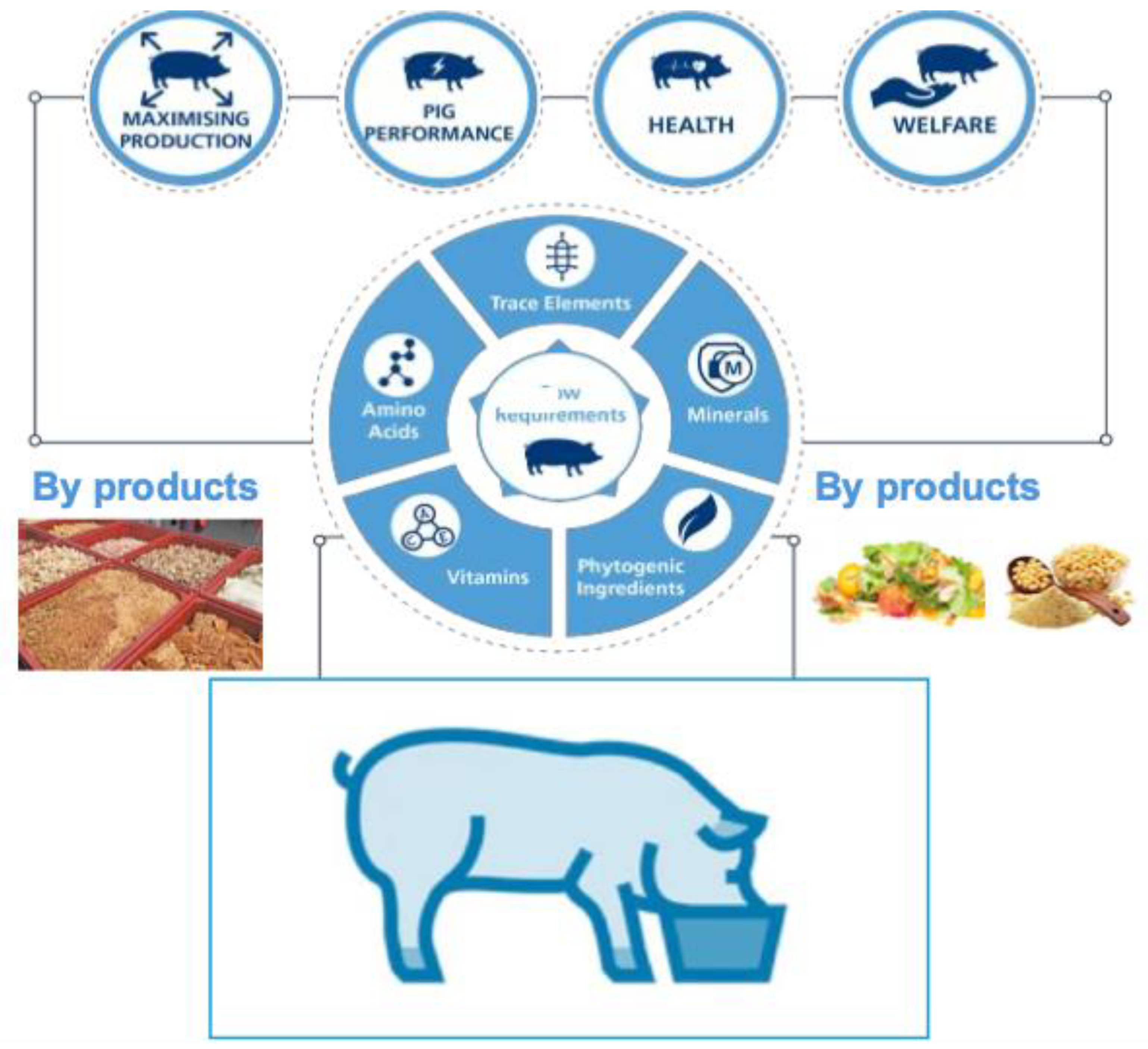

4.5. Beneficial Effects on Animal Health, Welfare and Performance

4.6. Alignment with the UN Sustainable Development Goals

5. Challenges and Limitations

6. Future Perspectives

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GHG | Greenhouse gas |

| FFPs | Former Food Products |

| SDGs | Sustainable development goals |

| FCR | Feed conversion ratio |

| ADG | Average daily gain |

| EU | European Union |

| UK | United Kingdom |

| LCA | Life cycle assesment |

| MUFA | Monounsaturated fatty acid |

| PUFA | Polyunsaturated fatty acid |

| ADFI | Average daily feed intake |

| BW | Body weight |

| VFA | Volatile fatty acids |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

References

- van Dijk, M.; Morley, T.; Rau, M.L.; Saghai, Y. A Meta-Analysis of Projected Global Food Demand and Population at Risk of Hunger for the Period 2010–2050. Nat. Food 2021, 2, 494–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcon, W.P.; Naylor, R.L.; Shankar, N.D. Rethinking Global Food Demand for 2050. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2022, 48, 921–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vastolo, A.; Serrapica, F.; Cavallini, D.; Fusaro, I.; Atzori, A.S.; Todaro, M. Editorial: Alternative and Novel Livestock Feed: Reducing Environmental Impact. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 1441905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praveen, B.; Sharma, P. A Review of Literature on Climate Change and Its Impacts on Agriculture Productivity. J. Public Aff. 2019, 19, e1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güneralp, B.; Reba, M.; Hales, B.U.; Wentz, E.A.; Seto, K.C. Trends in Urban Land Expansion, Density, and Land Transitions from 1970 to 2010: A Global Synthesis. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 044015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, M.; de Boer, I.J.M. Comparing Environmental Impacts for Livestock Products: A Review of Life Cycle Assessments. Livest. Sci. 2010, 128, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, T.; Maqsood, M.A.; Kanwal, S.; Hussain, S.; Ahmad, H.R.; Sabir, M. Fertilizers and Environment: Issues and Challenges. In Crop Production and Global Environmental Issues; Hakeem, K.R., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 575–598. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.W.; Gormley, A.; Jang, K.B.; Duarte, M.E. Current status of global pig production: an overview and research trends. Anim. Biosci. 2024, 37, 719–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salemdeeb, R.; zu Ermgassen, E.K.H.J.; Kim, M.H.; Balmford, A.; Al-Tabbaa, A. Environmental and health impacts of using food waste as animal feed: A comparative analysis of food waste management options. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 871–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, L.; Ferreira, M.; Domingos, I.; Oliveira, V.; Rodrigues, C.; Ferreira, A.; Ferreira, J. Life Cycle Assessment of Pig Production in Central Portugal: Environmental Impacts and Sustainability Challenges. Sustainability 2025, 17, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutt, T. Commercial Pig Farming Scenario, Challenges, and Prospects. In Commercial Pig Farming; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Luciano, A.; Tretola, M.; Ottoboni, M.; Baldi, A.; Cattaneo, D.; Pinotti, L. Potentials and challenges of former food products (food leftover) as alternative feed ingredients. Animals 2020, 10, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAuliffe, G.A.; Chapman, D.V.; Sage, C.L. A Thematic Review of Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) Applied to Pig Production. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2016, 56, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andretta, I.; Hickmann, F.M.W.; Remus, A.; Franceschi, C.H.; Mariani, A.B.; Orso, C.; Kipper, M.; Létourneau-Montminy, M.-P.; Pomar, C. Environmental Impacts of Pig and Poultry Production: Insights From a Systematic Review. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 750733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makkar, H.P.S.; Ankers, P. Towards Sustainable Animal Diets: A Survey-Based Study. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2014, 198, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Quelen, F.; Brossard, L.; Wilfart, A.; Dourmad, J.-Y.; Garcia-Launay, F. Eco-Friendly Feed Formulation and On-Farm Feed Production as Ways to Reduce the Environmental Impacts of Pig Production Without Consequences on Animal Performance. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 689012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Govoni, C.; Chiarelli, D.D.; Luciano, A.; Ottoboni, M.; Perpelek, S.N.; Pinotti, L.; Rulli, M.C. Global assessment of natural resources for chicken production. Adv. Water Resour. 2021, 154, 103987–103997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govoni, C.; Chiarelli, D.D.; Luciano, A.; Pinotti, L.; Rulli, M.C. Global assessment of land and water resource demand for pork supply. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 074003–074015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinotti, L.; Luciano, A.; Ottoboni, M.; Manoni, M.; Ferrari, L.; Marchis, D.; Tretola, M. Recycling food leftovers in feed as opportunity to increase the sustainability of livestock production. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 294, 126290–126303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flachowsky, G.; Meyer, U. Challenges for plant breeders from the view of animal nutrition. Agriculture 2015, 5, 1252–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachong Kum, S.; Voccia, D.; Grimm, M.; Froldi, F.; Suciu, N.A.; Lamastra, L. Reducing the Environmental Impacts of Pig Production Through Feed Reformulation: A Multi-Objective Life Cycle Assessment Optimisation Approach. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lestingi, A. Alternative and Sustainable Protein Sources in Pig Diet: A Review. Animals 2024, 14, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, J.V.; Andersen, H.M.-L.; Kristensen, T.; Schlægelberger, S.V.; Udesen, F.; Christensen, T.; Sandøe, P. Multidimensional Sustainability Assessment of Pig Production Systems at Herd Level—The Case of Denmark. Livest. Sci. 2023, 270, 105208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamborg, C. , Sandøe, P. Sustainability in farm animal breeding: a review. Livest. Prod. Sci. 2005, 92, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations, 2020. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- Lassaletta, L.; Estellés, F.; Beusen, A.H.W.; Bouwman, L.; Calvet, S.; van Grinsven, H.J.M.; Doelman, J.C.; Stehfest, E.; Uwizeye, A.; Westhoek, H. Future Global Pig Production Systems According to the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 665, 739–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papakonstantinou, G.I.; Voulgarakis, N.; Terzidou, G.; Fotos, L.; Giamouri, E.; Papatsiros, V.G. Precision Livestock Farming Technology: Applications and Challenges of Animal Welfare and Climate Change. Agriculture 2024, 14, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zu Ermgassen, E.K.H.J.; Phalan, B.; Green, R.E.; Balmford, A. Reducing the land use of EU pork production: Where there’s will, there’s a way. Food Policy 2016, 58, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldini, C.; Gardoni, D.; Guarino, M. A critical review of the recent evolution of Life Cycle Assessment applied to milk production. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 421–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, J. M. Re-defining efficiency of feed use by livestock. Animal, 2011, 5, 1014–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Termatzidou, S.-A.; Dedousi, A.; Kritsa, M.-Z.; Banias, G.F.; Patsios, S.I.; Sossidou, E.N. Growth Performance, Welfare and Behavior Indicators in Post-Weaning Piglets Fed Diets Supplemented with Different Levels of Bakery Meal Derived from Food By-Products. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makkar, H.P.S. Feed resources and their sustainability for animal production. Anim. Front. 2017, 7, 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Giromini, C.; Ottoboni, M.; Tretola, M.; Marchis, D.; Gottardo, D.; Caprarulo, V.; Baldi, A.; Pinotti, L. Nutritional evaluation of former food products (ex-food) intended for pig nutrition. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2017, 34, 14361445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luciano, A.; Tretola, M.; Mazzoleni, S.; Rovere, N.; Fumagalli, F.; Ferrari, L.; Comi, M.; Ottoboni, M.; Pinotti, L. Sweet vs. Salty Former Food Products in Postweaning Piglets: Effects on Growth, Apparent Total Tract Digestibility and Blood Metabolites. Animals 2021, 11, 3315–3326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luciano, A.; Espinosa, C.D.; Pinotti, L.; Stein, H.H. Standardized total tract digestibility of phosphorus in bakery meal fed to pigs and effects of bakery meal on growth performance of weanling pigs. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2022, 284, 115148–115157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinotti, L.; Ferrari, L.; Fumagalli, F.; Luciano, A.; Manoni, M.; Mazzoleni, S.; Govoni, C.; Rulli, M.C.; Lin, P.; Bee, G.; Tretola, M. ; Review: Pig-based bioconversion: the use of former food products to keep nutrients in the food chain. Animal 2023, 2, 100918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correddu, F.; Lunesu, M.F.; Buffa, G.; Atzori, A.S.; Nudda, A.; Battacone, G.; Pulina, G. Can agro-industrial by-products rich in polyphenols be advantageously used in the feeding and nutrition of dairy small ruminants? Animals 2020, 10, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasta, V. , Luciano, G. The effects of dietary consumption of plants secondary compounds on small ruminants’ products quality. Small Rumin. Res. 2011, 101, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simitzis, P.E.; Deligeorgis, S.G. Agroindustrial by-products and animal products: A great alternative for improving food-quality characteristics and preserving human health, in: Food Quality: Balancing Health and Disease. Elsevier, 2018; pp. 253–290.

- Regulation (EC) No 767/2009. The impact of Regulation (EC) 767/2009 on the practice of feed advertising in Europe, /: at: https; (accessed on 24 July 2025)2357.

- Furnols, M.F.; Realini, C.; Montossi, F.; Sañudo, C.; Campo, M.; Oliver, M.; Nute, G.; Guerrero, L. Consumer’s purchasing intention for lamb meat affected by country of origin, feeding system and meat price: A conjoint study in Spain, France and United Kingdom. Food Qual. Prefer. 2011, 22, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.D.; Kim, H.Y.; Jung, H.J.; Ji, S.Y.; Chowdappa, R.; Ha, J.H.; Song, Y.M.; Park, J.C.; Moon, H.K.; Kim, I.C. The effect of fermented apple diet supplementation on the growth performance and meat quality in finishing pigs. Anim. Sci. J. 2009, 80, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.; Cho, J.; Hwang, O.; Yang, S.; Park, K.; Choi, D.; Yoo, Y.; Kim, I. Effects of fermented diets including grape and apple pomace on amino acid digestibility, nitrogen balance and volatile fatty acid (VFA) emission in finishing pigs. J. Anim. Vet. Adv. 11, 3444–3451. [CrossRef]

- Pieszka, M.; Szczurek, P.; Bederska-Łojewska, D.; Migdał, W.; Pieszka, M.; Gogol, P.; Jagusiak, W. The effect of dietary supplementation with dried fruit and vegetable pomaces on production parameters and meat quality in fattening pigs. Meat Sci. 2017, 126, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julia, S.; Dieter, T.; Hermann, L.; Heinrich, H.D.M.; Michael, W.P. The influence of apple-or red-grape pomace enriched piglet diet on blood parameters, bacterial colonisation, and marker gene expression in piglet white blood cells. Food Nutr. Sci. 2011, 2, 366–376. [Google Scholar]

- Sehm, J.; Lindermayer, H.; Dummer, C.; Treutter, D.; Pfaffl, M. The influence of polyphenol rich apple pomace or red--wine pomace diet on the gut morphology in weaning piglets. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2007, 91, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikusika, O.O.; Akinmoladun, O.F.; Mpendulo, C.T. Enhancement of the Nutritional Composition and Antioxidant Activities of Fruit Pomaces and Agro-Industrial Byproducts through Solid-State Fermentation for Livestock Nutrition: A Review. Fermentation 2024, 10, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.R.; Hassan, Y.I.; Das, Q.; Lepp, D.; Hernandez, M.; Godfrey, D.V.; Orban, S.; Ross, K.; Delaquis, P.; Diarra, M.S. Dietary organic cranberry pomace influences multiple blood biochemical parameters and cecal microbiota in pasture-raised broiler chickens. J. Funct. Foods 2020, 72, 104053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluschke, A.M.; Williams, B.A.; Zhang, D.; Gidley, M.J. Dietary pectin and mango pulp effects on small intestinal enzyme activity levels and macronutrient digestion in grower pigs. Food Funct. 2018, 9, 991–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Qing, Y.; Yu, Q.; Tang, X.; Chen, G.; Fang, R.; Liu, H. By-product feeds: Current understanding and future perspectives. Agriculture 2021, 11, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.H.; Son, A.R.; Le, S.; Kim, B.G. Effects of dietary tomato processing byproducts on pork nutrient composition and loin quality of pigs. Asian J. Anim. Vet. Adv. 2014, 9, 775–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera-Soto, J.; Mendez-Llorente, F.; López-Carlos, M.A.; Ramírez-Lozano, R.; Carrillo-Muro, O.; Escareno-Sanchez, L.; Medina-Flores, C. Effect of fer mentable liquid diet based on tomato silage on the performance of growing finishing pigs. Interciencia 2014, 39, 428–431. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, G.M.; Park, B.K. Effects of fermented carrot by-product diets on growth performances, carcass characteristics and meat quality in fattening pigs. Acta Agric. Scand. A Anim. Sci. 2023, 72, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liotta, L.; Chiofalo, V.; Lo Presti, V.; Chiofalo, B. In vivo performances, carcass traits, and meat quality of pigs fed olive cake processing waste. Animals 2019, 9, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliopoulos, C.; Papadomichelakis, G.; Voitova, A.; Chorianopoulos, N.; Haroutounian, S.A.; Markou, G.; Arapoglou, D. Improved Antioxidant Blood Parameters in Piglets Fed Diets Containing Solid-State Fermented Mixture of Olive Mill Stone Waste and Lathyrus clymenum Husks. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boontiam, W. , Wachirapakorn, C., Wattanachai, S. Growth performance and hematological changes in growing pigs treated with Cordyceps militaris spent mushroom substrate. Vet. World 2020, 13, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Peng, Y.; He, J.; Xiao, D.; Chen, C.; Li, F.; Huang, R.; Yin, Y. Dietary mulberry leaf powder affects growth performance, carcass traits and meat quality in finishing pigs. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2019, 103, 1934–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, Y.-T.; Lo, H.H.; Awad, A.; Salman, H. Potato wastewater treatment, in: Handbook of Industrial and Hazardous Wastes Treatment. CRC Press, 2004; pp. 894–951.

- Gerber, P.J.; Steinfeld, H.; Henderson, B.; Mottet, A.; Opio, C.; Dijkman, J.; Falcucci, A.; Tempio, G. Tackling Climate Change through Livestock: A Global Assessment of Emissions and Mitigation Opportunities.; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2013; ISBN 92-5-107920-X. [Google Scholar]

- Mielcarek-Bocheńska, P.; Rzeźnik, W. Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Agriculture in EU Countries—State and Perspectives. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zervas, G.; Tsiplakou, E. An Assessment of GHG Emissions from Small Ruminants in Comparison with GHG Emissions from Large Ruminants and Monogastric Livestock. Atmos. Environ. 2012, 49, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gislason, S.; Birkved, M.; Maresca, A. A Systematic Literature Review of Life Cycle Assessments on Primary Pig Production: Impacts, Comparisons, and Mitigation Areas. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 42, 44–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferket, P.R.; Van Heugten, E.; Van Kempen, T.A.T.G.; Angel, R. Nutritional Strategies to Reduce Environmental Emissions from Nonruminants. J. Anim. Sci. 2002, 80, E168–E182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andretta, I.; Hauschild, L.; Kipper, M.; Pires, P.G.S.; Pomar, C. Environmental Impacts of Precision Feeding Programs Applied in Pig Production. Animal 2018, 12, 1990–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagar, N.A.; Pareek, S.; Sharma, S.; Yahia, E.M.; Lobo, M.G. Fruit and Vegetable Waste: Bioactive Compounds, Their Extraction, and Possible Utilization. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2018, 17, 512–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosales, T.K.O.; Fabi, J.P. Valorization of polyphenolic compounds from food industry by-products for application in polysaccharide-based nanoparticles. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1144677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avila-Nava, A.; Medina-Vera, I.; Toledo-Alvarado, H.; Corona, L.; Márquez-Mota, C.C. Supplementation with antioxidants and phenolic compounds in ruminant feeding and its effect on dairy products: a systematic review. J. Dairy Res. 2023, 90, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammerer, D.R. , Kammerer, J., Valet, R., Carle, R. Recovery of polyphenols from the by-products of plant food processing and application as valuable food ingredients. Food Res. Intern.

- Waqas, M.; Salman, M.; Sharif, M.S. Application of polyphenolic compounds in animal nutrition and their promising effects. J. Anim. Feed Sci. 2023, 14, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez-Gómez, V.; González-Barrio, R.; Periago, M.J. Interaction between Dietary Fibre and Bioactive Compounds in Plant By-Products: Impact on Bioaccessibility and Bioavailability. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press. 2021.

- Sossidou, E.N.; Banias, G.F.; Batsioula, M.; Termatzidou, S.-A.; Simitzis, P.; Patsios, S.I.; Broom, D.M. Modern Pig Production: Aspects of Animal Welfare, Sustainability and Circular Bioeconomy. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahazi, M. A.; Hoseinifar, S. H. ; Jafari,V.; Hajimoradloo, A.; Van Doan, H.; and Paolucci, M. Dietary Supplementation of Polyphenols Positively Affects the Innate Immune Response, Oxidative Status, and Growth Performance of Common Carp, Cyprinus carpio L, Aquaculture 2020, 17.

- Georganas, A.; Kyriakaki, P.; Giamouri, E.; Mavrommatis, A.; Tsiplakou, E.; Pappas, A. Mediterranean agro-industrial by-products and food waste in pig and chicken diets: which way forward? Livest. Sci. 2024, 289, 105584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, H.; Li, Y.; Wu, S.; He, J. Natural plant polyphenols contribute to the ecological and healthy swine production. J Anim Sci Biotechnol. 2024, 15, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Meo, M.C.; Licaj, I.; Varricchio, R.; De Nisco, M.; Stilo, R.; Rocco, M.; Bianchi, A.R.; D’Angelo, L.; De Girolamo, P.; Vito, P.; Zarrelli, A.; Varricchio, E. Functional Feed with Bioactive Plant-Derived Compounds: Effects on Pig Performance, Muscle Fatty Acid Profile, and Meat Quality in Finishing Pigs. Animals 2025, 15, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nudda, A. , Carta, S., Correddu, F., Caratzu, M. F., Cesarani, A., Hidalgo, J., Pulina, G., & Lunesu, M. F. A meta-analysis on use of agro-industrial by-products rich in polyphenols in dairy small ruminant nutrition. Animal, 1015. [Google Scholar]

- Riahi, C.; Badia, A.D.; Oscar, C.; Raquel, C.; Giuseppe, M.; Prentza, Z; Papatsiros, V. G. Detoxification of emerging mycotoxins in broiler chickens using an innovative liquid anti-mycotoxins solution. Veterinaria 2025, 61, N. [Google Scholar]

- Papakonstantinou, G. .; Meletis, E.; Petrotos, K.; Kostoulas, P.; Tsekouras, N.; Kantere, M.C.; Voulgarakis, N.; Gougoulis, D.; Filippopoulos, L.; Christodoulopoulos, G.; Athanasiou, L.V.; Papatsiros VG. Effects of a Natural Polyphenolic Product from Olive Mill Wastewater on Oxidative Stress and Post-Weaning Diarrhea in Piglets. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1356. [Google Scholar]

- Papatsiros, V.G.; Eliopoulos, C.; Voulgarakis, N.; Arapoglou, D.; Riahi, I.; Sadurní, M.; Papakonstantinou, GI. Effects of a Multi-Component Mycotoxin-Detoxifying Agent on Oxidative Stress, Health and Performance of Sows. Toxins 2023, 15, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papatsiros, V.G.; Katsogiannou, E.G.; Papakonstantinou, G.I.; Michel, A.; Petrotos, K.; Athanasiou, L.V. Effects of Phenolic Phytogenic Feed Additives on Certain Oxidative Damage Biomarkers and the Performance of Primiparous Sows Exposed to Heat Stress under Field Conditions. Antioxidants, 2022, 11, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papatsiros, V.G.; Papakonstantinou, G.I.; Katsogiannou, E.; Gougoulis, D.A.; Voulgarakis, N.; Petrotos, K.; Braimaki, S.; Galamatis, D.A.; El-Sayed, A.; Athanasiou, L.V. Effects of a Phytogenic Feed Additive on Redox Status, Blood Haematology, and Piglet Mortality in Primiparous Sows. Stresses 4, 293–307. [CrossRef]

- Papatsiros, V.G.; Papakonstantinou, G.I.; Voulgarakis, N.; Eliopoulos, C.; Marouda, C.; Meletis, E.; Valasi, I.; Kostoulas, P.; Arapoglou, D.; Riahi, I.; Christodoulopoulos, G.; Psalla, D. Effects of a Curcumin/Silymarin/Yeast-Based Mycotoxin Detoxifier on Redox Status and Growth Performance of Weaned Piglets under Field Conditions. Toxins 16, 168. [CrossRef]

- Ait-Sidhoum, A.; Guesmi, B.; Cabas-Monje, J.; Roig, J.M.G. The Impact of Alternative Feeding Strategies on Total Factor Productivity Growth of Pig Farming: Empirical Evidence from Eu Countries. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2021, 19, e0106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, S.; Grassauer, F.; Arulnathan, V.; Sadiq, R.; Pelletier, N. A review of life cycle impacts of different pathways for converting food waste into livestock feed. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 46, 310–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hal, O.; de Boer, I.J.M.; Muller, A.; de Vries, S.; Erb, K.-H.; Schader, C.; Gerrits, W.J.J.; van Zanten, H.H.E. Upcycling food leftovers and grass resources through livestock: Impact of livestock system and productivity. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 219, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA. Food and feed safety vulnerabilities in the circular economy. EFSA Support. Publ. 2022, 19, EN–7226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA FEEDAP Panel. Guidance on the assessment of the safety of feed additives for the target species. EFSA J, 2017, 15, 5021. [Google Scholar]

- Poore, J.; Nemecek, T. Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Science 2018, 360, 987–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridoutt, B.G.; Pfister, S. A revised approach to water footprinting to make transparent the impacts of consumption and production on global freshwater scarcity. Global Environ. Change 2010, 20, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomar, C.; Remus, A. Precision pig feeding: A breakthrough toward sustainability. Anim. Front. 2019, 9, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dourmad, J.-Y.; Ryschawy, J.; Trousson, T.; Bonneau, M.; Gonzalez, J.; Houwers, H.W.J.; Hviid, M.; Zimmer, C.; Nguyen, T.L.T.; Morgensen, L. Evaluating environmental impacts of contrasting pig farming systems with life cycle assessment. Animal 2014, 8, 2027–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serra, V.; Salvatori, G.; Pastorelli, G. Dietary Polyphenol Supplementation in Food Producing Animals: Effects on the Quality of Derived Products. Animals 2021, 11, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlaicu, P.A.; Untea, A.E.; Varzaru, I.; Saracila, M.; Oancea, A.G. Designing Nutrition for Health—Incorporating Dietary By-Products into Poultry Feeds to Create Functional Foods with Insights into Health Benefits, Risks, Bioactive Compounds, Food Component Functionality and Safety Regulations. Foods 2023, 12, 4001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firoiu, D.; Ionescu, G.H.; Cismaș, C.M.; Costin, M.P.; Cismaș, L.M.; Ciobanu, Ș.C.F. Sustainable Production and Consumption in EU Member States: Achieving the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDG 12). Sustainability 2025, 17, 1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabato, W.; Getnet, G.T.; Sinore, T.; Nemeth, A.; Molnár, Z. Towards Climate-Smart Agriculture: Strategies for Sustainable Agricultural Production, Food Security, and Greenhouse Gas Reduction. Agronomy 2025, 15, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. The European Green Deal. 2019.

- European Commission. A Farm to Fork Strategy for a fair, healthy and environmentally-friendly food system. Communication from the Commission, COM(2020) 381 final, Brussels.

- Shurson, G.C.; Urriola, P.E. Sustainable swine feeding programs require the convergence of multiple dimensions of circular agriculture and food systems with One Health. Anim. Front. 2022, 12, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| By-product | Major nutrients | Potential inclusion Rate | Beneficial effects | References |

| Whey |

|

10–15% of diet |

|

[29] |

| Brewers’ spent grains |

|

15–25% |

|

[30] |

| Bakery waste |

|

10–20% |

|

[10,31] |

| Fruit/vegetable pulp |

|

5–15% |

|

[9] |

| Oilseed meals |

|

5–20% |

|

[32] |

| Approach | Evaluated impacts | References |

| Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) | Quantification of GHG emissions, energy demand, land and water use, and overall resource efficiency | [10] |

| Growth performance trials | Average daily gain (ADG), feed conversion ratio (FCR), and carcass characteristics | [30] |

| Nutritional analysis | Determination of crude protein, amino acid profile, fiber content, and energy digestibility | [29] |

| Waste diversion metrics | Measurement of the proportion of food residues redirected from landfills to feed use | [9] |

| Economic assessment | Evaluation of feed cost reduction and profitability associated with by-product utilization | [28] |

| By-Product | Age | Type | Concentration | Effects | Reference |

| Apple | Finishing pigs | Fermented apple supplement | 2% w/w | Improved growth performance and feed quality | [42] |

| Finishing pigs | Apple pomace | 10 or 20% w/w | Promotion of beneficial bacteria Reduced volatile fatty acids emissions Increased FCR |

[43,44] | |

| Piglets | Apple pomace | 3.5% w/w | Beneficial effects on gut microbiota and blood parameters | [45,46] | |

| Finishing pigs | Fermented apple pomace with Lactobacillus plantarum | Enhanced feed efficiency, Lowered ADFI without effect on animal’s final BW and back fat thickness |

[47] | ||

| Grape pomace | Finishing pigs | Fermented Grape pomace with Lactobacillus plantarum |

Improved beneficial bacteria and reduced VFA emissions in faeces | [43] | |

| Strawberry | Growing pigs | Fermented Strawberry pomace with Lentinus edodes | Positive effect on the lean tissues | [48] | |

| Mango | Growing pigs | Mango pulp | 15% w/w | Improved the efficiency of starch Protein digestion to a certain extent |

[49,50] |

| Tomato | Pigs | Tomato residues | 3% or 5% w/w | Slight affection in pork’s meat attributes | [51] |

| Finishing pigs | Tomato silage | 30% w/w | Promotion of growth performance | [52] | |

| Carrot | Finishing pigs | Carrot wastes | 20–25% w/w | Increase of FCR Improved meat quality |

[44,53] |

| Olive | Growing-finishing pig | Olive Cake Processing Waste |

5, 10% w/w | Reduced backfat thickness and intramuscular fat Changed their fatty acid content Increased levels of MUFA and PUFA Improved-quality indices |

[54] |

| Piglets | Fermented Mixture of Olive Mill Stone Waste and Lathyrus clymenum pericarp with Pleurotus ostreatus | 5% w/w | Improved antioxidant blood parameters | [55] | |

|

Cordyceps. militarisspent mushroom substrate |

Growing pigs | Cordyceps. militaris spent mushroom substrate | 2g/kg | Improved growth performance and immunoglobulin secretion Enhanced antioxidant activity Reduced cholesterol, and MDA’s levels |

[56] |

| Mulberry | Finishing pigs | Mulberry leaves | 3,6,9,12% w/w | Higher loin-eye area and increased crude protein’s levels Enhanced inosine monophosphate content and amino acids in muscle tissues |

[57] |

| Strawberry | Finishing pigs | Strawberry pomace | 10% w/w | improved fatty acid composition in pork meat | [44] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).