1. Introduction

Globally, and particularly within the European Union (EU), the ban on antibiotic growth promoters and the therapeutic use of zinc oxide has markedly influenced pig production practices. The reduction in therapeutic zinc oxide levels has heightened the clinical risk of edema disease caused by E. coli, prompting renewed industry focus on these issues [

1]. Recent surveys indicate that over 50% of German farms have animals testing positive for the verotoxin gene, indicating a susceptibility to edema disease [

2]. In Europe, post-weaning diarrhea (PWD) is a leading cause of economic loss, with mortality rates reaching up to 20-30% in severe cases. PWD is further exacerbated by the presence of

E. coli strains that exhibit resistance to conventional treatments and antibiotics [

3,

4]. PWD together with pathogenic

E. coli not only compromises piglet survival but also impedes growth and escalates medical treatment costs, directly affecting farm profitability.

The weaning process and the transition to solid feed is a critical period for piglets. Optimal early-stage nutrition is crucial for ensuring piglet health and well-being. During the initial three to five days post-weaning, it is common for piglets to exhibit minimal to no feed intake. This period of reduced intake deprives the intestinal lumen of essential nutrients, resulting in adverse physiological effects such as intestinal villus atrophy, diminished enzyme activity, impaired nutrient absorption, increased intestinal permeability, and inflammation [

5]. Collectively, these conditions contribute to reduced body weight (BW) gain during this critical phase. Additionally, the presence of unabsorbed nutrients, particularly proteins, within the intestinal lumen can lead to undesirable fermentation processes, which are recognized risk factors for digestive disorders and diseases [

5]. It is well-established that achieving high feed intake shortly after weaning is associated with improved gastrointestinal tract development and enhanced performance throughout the nursery stage, regardless of initial BW [

5,

6].

The weaning challenge and ban on therapeutic use of ZnO have led to improvements in animal management, facility hygiene, prophylactic vaccination strategies and has necessitated significant changes in nutritional strategies at weaning. In response to the need to prevent PWD and reduce weaning mortality, European post-weaning diets have undergone significant modifications. These adjustments include the incorporation of high-quality digestible proteins, organic acids, synthetic amino acids, and a substantial reduction in overall dietary protein levels. Whereas commercial weaning diets once commonly contained protein levels around 20%, current formulations have reduced protein content to approximately 15-16%. However, this reduction of dietary crude protein negatively impacts animal performance during the nursery phase, resulting in nursery-end weights that fall below the expected 24-26 kg, a benchmark typical of recent years. This creates a dilemma in Europe: the use of low-protein diets at weaning to mitigate PWD yet accepting reduced performance during the nursery stage.

Spray-dried plasma (SDP) is a safe and functional protein that offers a promising solution to this dilemma by supporting sustained growth and mitigating health challenges. SDP is rich in bioactive peptides, growth factors, amino acids, and vitamins, all of which retain their biological activity post-processing [

7]. SDP is not only a functional and highly digestible protein that supports growth and helps reducing health challenges in piglets, but it also contributes to sustainable farming practices. As a by-product of the meat industry, SDP aligns with the principles of the circular economy by upcycling materials that would otherwise go to waste. This reduces the environmental footprint of livestock production, making SDP a key ingredient in balancing piglet performance and sustainability.

Traditionally, SDP has been incorporated into pig starter diets, calf milk replacers, and broiler feed [

8,

9,

10,

11]. The functional components of dietary SDP enhance intestinal integrity and modulate the immune system, thereby mitigating the adverse effects of inflammation and stress [

7]. Moreover, dietary SDP has shown a systemic effect with beneficial effects on other mucosal tissues, including lung-associated lymphoid tissue [

12] and has been associated with improved growth performance and reduced mortality, particularly under conditions of environmental or pathological stress [

8,

13]. Consequently, SDP is considered as a potential alternative to antibiotics and therapeutic level of ZnO [

8,

14]. Furthermore, SDP is a highly digestible protein that can be incorporated into weaning diets with higher protein levels without increasing the risk of PWD, thus improving overall performance by the end of the nursery period. Pigs fed diets with SDP have consistently been shown to enhance feed intake during the early weaning period, thereby avoiding the intestinal issues associated with low intake during these critical days.

The objective of the current studies was to evaluate the effects of incorporating porcine SDP into pig diets under two different nutritional strategies, lower and higher (normal) protein and standardized ileal digestible (SID) lysine levels across three nursery feeding phases.

2. Materials and Methods

Two concurrent studies were conducted at two different farms to evaluate the effectiveness of spray-dried porcine plasma under two different nutritional strategies using lower or higher (normal) protein, SID lysine and ME diets fed during three nursery feeding phases. Farm 1 used low protein diets in phase 1 (15.88%), phase 2 (17.10%) and phase 3 (17.5%), whereas Farm 2 used normal protein diets (20.5%, 20.0% and 18.2%) for phases 1, 2 and 3 respectively.

The first study was conducted at Farm 1 (Commercial/research facility located in Fraga, Huesca, Spain). The center consists of 7 identical rooms (373.2 m²), each equipped with 52 slatted floor pens of 6m², with individual feeders and drinkers per pen. Stocking density was set at a minimum of 0.25 m² per animal to provide a maximum of 24 piglets averaging 25 kg BW at the end of the experiment. Each room was equipped with floor heating and sensors for temperature, relative humidity (RH), CO

2 and NH

3 to control the dynamic ventilation system. The ventilation rate depended on the measured inside temperature and the age of the piglets, thereby keeping the temperature as close as possible to the requested temperature schedule and minimizing NH

3 and CO

2 content of the inside air. The light schedule was set as 24L:0D for the first two days and from day 3 onwards animals were subjected to a 9L:15D light schedule. In this study, pigs were fed low protein diets across three nursery feed phases with respective feeding durations of 14, 14 and 13 days during the 42-day study. All pigs received a common prestarter feed the day of placement before allocating them to their treatments groups the following day to start the experiment. Three treatment groups included: a CONTROL group fed phase 1, 2 and 3 control diets without SDP; a P1SDP group fed a phase 1 diet with 3.5% SDP, followed by the control phase 2 and 3 diets; and a P1+P2SDP group fed the phase 1 diet with 3.5% SDP, a phase 2 diet with 1.5% SDP, and the control phase 3 diet (

Table 1). At Farm 1, 24-day-old (Danbred x Pietrain) piglets were weaned and assigned by sex and initial body weight to 12 pens/treatment with 24 pigs/pen (288 pigs/treatment; 864 total pigs). That study was approved by the AB-Neo Animal Care Committee and the animals in this study were raised and treated according to the Directive 2010/63/EU of 22 September 2010, according to the recommendation of the European Commission 2007/526/CE covering the accommodation and care of animals used for experimental and other scientific purposes, and the Spanish Royal Decree 118/2021 which established the basic rules applicable for the protection of animals used in experimentation and other scientific purposes.

The second study was conducted at Farm 2 (IRTA research farm, Mas Bové, Tarragona, Spain) where 96 pigs were housed in a weaning room with 24 pens (1.84 m

2) providing 0.46 m

2 per pig. Each pen contained a single feeder with four eating spaces and one water drinking bowl to allow

ad libitum feed and water consumption. The facilities were not cleaned and disinfected before the start of the trial in order to provide an unspecific challenge to the animals to mirror commercial conditions. The rooms were provided with automatic heating, forced ventilation, and completely slatted floors. Pigs were fed higher (normal) protein diets across three nursery phases with feeding durations of 14 days per phase in the 42-day study. As for Farm 1, there were three treatment groups including a CONTROL, P1SDP and P1+P2SDP (

Table 2). The main difference at Farm 2 was that the phase 1 diet contained 5% SDP and the phase 2 diet contained 2% SDP. At this farm, 26-day-old ([Large White x Landrace] x Pietrain) piglets were weaned and assigned by sex and initial body weight to 8 pens/treatment with 4 pigs/pen (32 pigs/treatment; 96 total pigs). As in the case of Farm 1, the animals in this study were raised and treated according to the Directive 2010/63/EU of 22 September 2010, according to the recommendation of the European Commission 2007/526/CE covering the accommodation and care of animals used for experimental and other scientific purposes, and the Spanish Royal Decree 118/2021 principles for animal care and experimentation. This study was also approved by IRTA’s Ethical Committee for Animal Experimentation (CEEA).

2.1. Performance and Feed Intake

In Farm 1, pen weights were recorded on day 1, 15, 29 and 42 of the study. In Farm 2, pigs were individually weighed on day 0, 14, 28 and 42 of the study. In both studies, at the end of each feeding phase the remaining feed in each hopper was recorded to calculate average daily feed intake (ADFI) and feed conversion ratios (FCR) per feeding phase. The remaining feed from the previous phase was kept to a minimum but not removed before the next feeding phase was supplied in Farm 1 but fully removed at each phase change for Farm 2. Animals had ad libitum access to feed and water throughout the entire evaluation period. Every morning, all hoppers were checked visually and those needing to be refilled were filled automatically by a pneumatic feed distribution system in Farm 1 and manually from independent feed bags prepared for each pen in Farm 2.

2.2. Mortality and Morbidity

The general health status of the animals was monitored daily and registered throughout the trial. Details of any treatments administered to trial pigs were recorded (date, medication, dosage and reason of treatment) along with any details of pig removals to sick pens. Mortality was registered daily, and animals exhibiting poor performance were excluded from the evaluation and counted as culled animals (including pig weight at the point of removal). Every morning, the number of dead and culled piglets and their respective body weights (BW) were registered to allow for corrections in ADFI, FCR, ADG, as well as the reason of removal/death in Farm 1. For farm 2, in addition, the individual weight of the piglets remaining in the pen of the dead/culled animal were also registered and used for the corrections.

2.3. Diarrhea Score

Feces from each pen were visually examined in the morning to determine the incidence of post-weaning diarrhea and ascertain the health status of the pigs. It was assessed daily during the first 3 weeks and after that 3 days/week. At farm 1, fecal score was assessed using a subjective score on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 to 4 (1 = normal feces; 2 = moist feces; 3 = diarrhea; 4 = severe diarrhea/watery diarrhea). At farm 2, fecal score evaluation used a score on a 5-points scale ranging from 0 to 4 (0 = firm and shaped; 1 = soft and shaped; 2 = soft without shaped; 3 = loose; 4 = watery). In both farms, fecal score was conducted most of the time by the same person

2.4. Statistical Analaysis

Data were analyzed using the General Linear Model procedure of JMP (version 17.0) with the pen serving as the experimental unit for all growth performance analyses. Non-normal data or data displaying heteroscedasticity (mortality, culling, and treated animals) were analyzed using a Generalized Linear Mixed Model with Poisson distribution for goodness of fit Chi-squared test. Treatment was included in the model as main effects with initial body weight included as a covariate. Diarrhea days were analyzed using a Goodness of Fit Chi-squared test. P values of < 0.05 were classed as significant and those between 0.05-0.1 were considered trends. Significantly different means were separated using the Tukey’s HSD post-hoc test. All data are reported as Least Square Means except for diarrhea days and number of medicated animals, which are presented as count data.

3. Results

In the study conducted at Farm 1 using low protein diets, the performance benefits of SDP were evident during phase 1, with higher average daily gain (ADG) and average daily feed intake (ADFI) despite using a lower inclusion level of SDP than recommended (3.5% vs 5%). However, no additional performance advantage was noted with SDP inclusion during phase 2, in which a tendency for increased ADFI and worse FCR were observed. However, during phase 3 when all pigs were fed a common diet, there was a tendency for better FCR for pigs that had been fed SDP in phase 1. For the overall performance results, pigs fed SDP in phase 1 or in both phases 1 and 2 had higher ADG versus the control group. No incidences of diarrhea were observed for any treatment group during any phase of the study (

Table 3).

There were no significant differences among treatment groups for mortality, culling, mortality + culling and total medications, expressed as percentage of initial number of pigs (

Table 4).

In the study conducted at Farm 2, pigs were fed diets with normal protein and energy levels during all three phases, along with the recommended SDP inclusion levels for phases 1 and 2 (5% and 2%, respectively). During phase 1, there were no significant performance or fecal score differences among treatment groups (

Table 5).

During phase 2, pigs in the P1+P2SDP group exhibited higher ADG, and ADFI compared to the CONTROL and P1SDP groups and higher BW relative to the CONTROL group. During phase 3, when all groups were fed an identical phase 3 control diet, pigs from the P1+P2SDP group tended to have higher phase 3 final BW, with no significant differences among groups for other parameters. The P1SDP group had intermediate BW compared to the other two groups.

Overall, there was a tendency for pigs in the P1+P2SDP group to have higher ADG than the CONTROL group, while that of the P1SDP group was intermediate. No differences in fecal scores were observed among treatments in the Farm 2 study and again no incidence of diarrhea was observed for any group.

Three piglets did not complete the trial. They were removed with signs of meningitis (one from treatment P1SDP and two from treatment P1+P2SDP).

4. Discussion

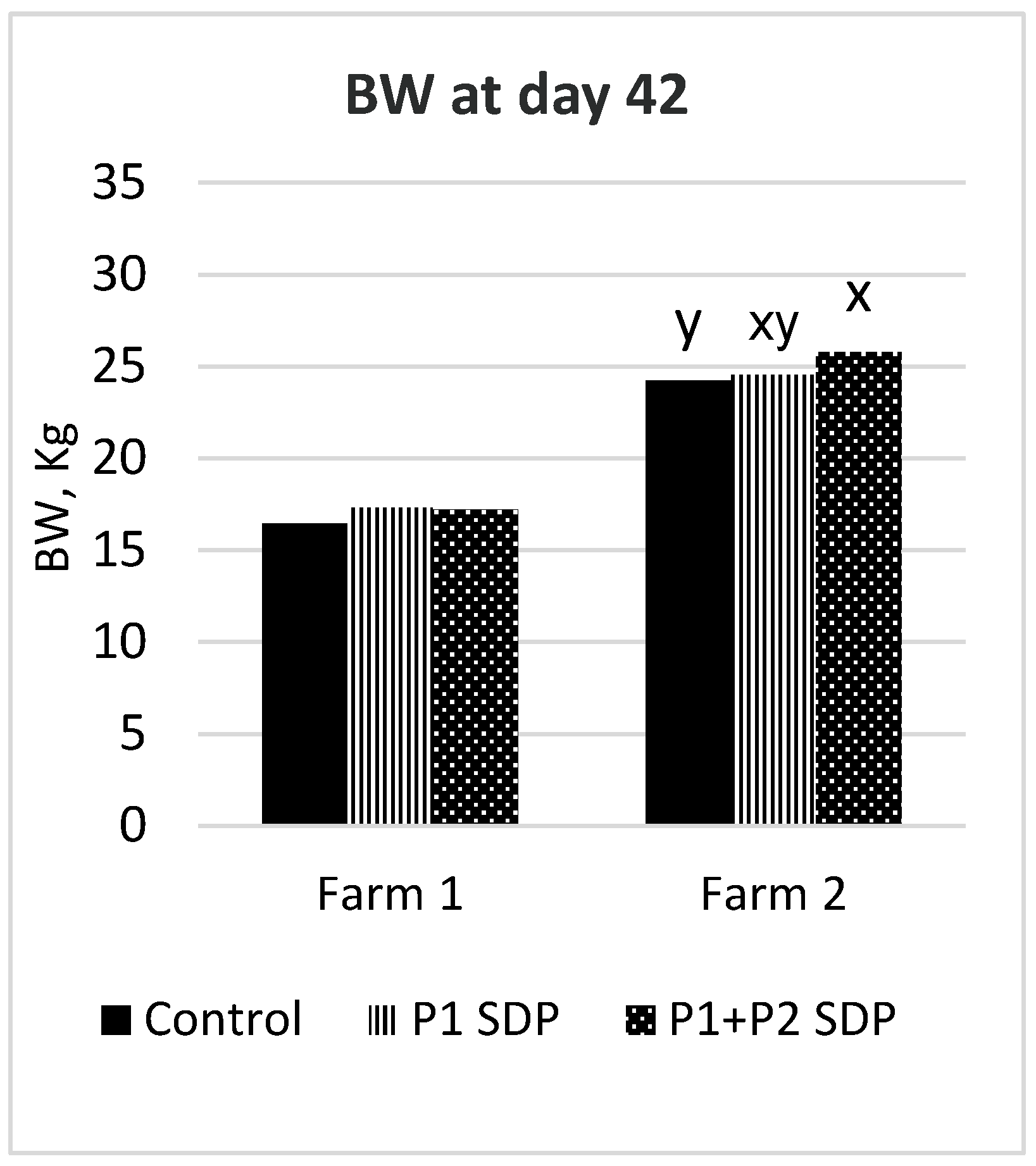

Although the two studies were run at research facilities with commercial and academic farm conditions that used different pig genetics, pig health status, pigs per pen and management practices, a comparative summary of the final day 42 BW differences by Farm in

Figure 1 provides European pig producers valuable insights into the expected outcomes of these two nutritional strategies using low or normal protein diets, particularly in the context of adding SDP in phase 1 and/or phase 2 diets devoid of pharmaceutical levels of zinc oxide.

Since the European Union’s ban on the therapeutic use of zinc oxide in 2022, post-weaning diets have undergone significant modifications to prevent post-weaning diarrhea and reduce nursery mortality. This regulatory shift has led to improvements in animal management, facility cleanliness, and prophylactic vaccination strategies, but it has also needed substantial changes in nutritional approaches at weaning. These adjustments have included the use of highly digestible proteins, organic acids, synthetic amino acids, and a marked reduction in overall dietary protein levels. For instance, SEGES, the Danish Feed Research Centre, has provided recommendations to Danish farmers for formulating weaning diets in the absence of high levels of zinc oxide. These recommendations emphasize nursery diets incorporating barley, potato protein, amino acid supplementation, reduced or eliminated soybean meal in initial diets, and the inclusion of benzoic acid and highly digestible proteins such as whey protein and SDP (

https://landbrugsavisen.dk/svin/her-er-tre-seges-bud-p%C3%A5-zinkfrit-frav%C3%A6nningsfode).

Understanding and addressing these nutritional and health challenges during weaning is critical for pig producers to improve piglet outcomes and maintain farm profitability. In the current landscape, it is common to see weaning diets with protein levels around 15-16% to avoid indigestible proteins in the gut that could foster the growth of pathogenic bacteria [

15,

16,

17,

18]. However, these lower protein levels can negatively impact animal performance during the nursery phase, leading to final weights that fall short of the 24-26 kg typically expected at the end of this period.

In the study conducted at Farm 1, despite using a lower inclusion level of SDP than recommended (3.5% vs. 5%), the performance benefits of SDP were evident during the initial 15-day period, with higher ADG and ADFI observed. However, no additional performance advantage was noted with SDP inclusion during the second and third periods. For the overall period ADG was higher for pigs in the SDP groups versus the control group. Therefore, relative to the control group, pigs receiving SDP in Phase 1 were 0.88 kg heavier, and pigs receiving SDP in both Phases 1 and 2 were 0.75 kg heavier, at the end of the study. These findings align with previous research highlighting the benefits of SDP in Phase 1 diets [

8,

13]. The lack of improved performance with SDP during Phase 2 in this study could be attributed to the lower inclusion level of SDP (1.5%) and/or the restrictive low protein and energy levels used in the phase 1 and 2, which may have limited growth potential, because ADG was similar across treatments during this period. Our results agree with those of Bailey et al. [

19] in which the authors fed 6% SDP in low protein diets during phase 1 (d1-14) and 2% SDP in phase 2 (d15-28) and they also did not observe performance benefits of this combination compared to just using SDP in the phase 1 diet. The same authors suggest that the low CP diets that are generally fed to pigs in the initial first or second weeks when pigs are more susceptible to diarrhea, if fed for longer periods, may lead to growth losses that pigs may not compensate later in life [

19,

20,

21], as confirmed in our study. Furthermore, there were no differences in fecal scores among treatments containing SDP versus control diets.

In contrast, the study conducted at Farm 2 employed higher protein levels during Phases 1 and 2, along with the recommended SDP inclusion levels for these phases (5% and 2%, respectively). Although no statistically significant differences in performance were observed during Phase 1 (0-14 days), this may be due to the lower number of animals per replicate and higher variability of the data. Indeed, from a numerical point of view, piglets in the SDP groups (P1SDP and P1+P2SDP) were heavier, had higher ADG and ADFI, and better FCR compared to the control group. In Phase 2 (days 14-28), pigs fed SDP exhibited significantly higher BW, ADG, and ADFI compared to the control group, and those receiving SDP only during the first 14 days had intermediate BW but similar ADG and ADFI to the control group. By the end of the nursery phase (day 42), final BW was 1.54 kg higher in the group fed SDP during both Phase 1 and 2 compared to the control group, confirming results from Castelo et al., [

22] that reported performance benefits and reduced E. coli K88 fecal shedding of non-restricted protein nursery diets with SDP included in phase 1 and 2 diets. In the study by Bailey et al. [

19] using 2% SDP in phase 2 normal CP diets after pigs had received low CP diets with 6% SDP in phase 1 improved performance compared with the phase 2 control and the group with SDP only fed during phase 1, proving the benefits of supplementing SDP for longer periods especially after transitioning from a low phase 1 protein diet to higher phase 2 protein diet.

When comparing the relative performance across both trials, during the first period, pigs in the control groups increased their body weight by 23%, while pigs in the SDP groups showed increases of 30-36%. During Phase 2, the control groups exhibited a BW increase of 61% and 57% at Farm 1 and Farm 2, respectively, with SDP groups showing increases of 55-61%, the highest being in the treatment with SDP inclusion in Phase 2 at Farm 2. However, in the common final phase without SDP (days 28/29 to 42), pigs at Farm 1 increased their BW by 43% across all treatments, while those at Farm 2 increased their BW by 67-71%. Notably, the diet composition during the common period, without SDP, was similar in protein levels between the two nutritional strategies (17.5% and 18.2% for Farms 1 and 2, respectively), with slightly higher metabolizable energy (ME) for Farm 1 (3312 kcal/kg) compared to Farm 2 (3280 kcal/kg). The lower specifications for essential amino acids in the Farm 1 diet may partially explain the differences observed during this period. Synthetic amino acids like L-Lysine, DL-Methionine and L-Threonine were supplemented to the low CP diet, however, the reduced growth performance may be due not only to the lower levels of these amino acids, but also to the limited amount of branched-chain AA and other essential and non-essential AAs in these diets that positively affect feed intake and protein deposition in the muscle of pigs [

23,

24].

Furthermore, it was observed that the initial BW of pigs at Farm 2 was approximately 1.7 kg heavier than that of control pigs at Farm 1. This initial weight difference could contribute to the performance disparity between the pigs, as each kilogram difference at weaning is expected to translate to a 2-3 kg difference by the end of the nursery phase [

5]. However, the final BW difference at the end of the nursery was 7.45 kg greater for the control group at Farm 2 compared to Farm 1, suggesting that the low-protein diet strategy employed at Farm 1 may have contributed to limited pig growth during the nursery phases (

Figure 1).

The primary motivation for reducing protein levels in Phase 1 and 2 diets in Europe following the ban on therapeutic levels of zinc oxide has been to mitigate post-weaning diarrhea and reduce mortality, particularly during the first and second weeks after weaning [

25]. Without the pharmacological protection of zinc oxide, the clinical risk of edema disease caused by

E. coli has re-emerged as a significant concern for the industry. More than 50% of surveyed German farms have reported animals positive for the verotoxin gene, indicating a widespread susceptibility to edema disease [

2]. Miller et al. [

26] identified two distinct peaks of fecal looseness during phases 1 and 2 of the nursery periods: the first around day 4, corresponding to infections with

E. coli K88 and Rotavirus A, and the second around day 17, associated with

E. coli F18 infection. Supporting this, Spanish nursery farms reported a drastic increase in the prevalence of

E. coli F18 (from 18% to 28%) and STX2e (from 19% to 34%) between 2022 and 2023 [

27], suggesting a clear impact of the zinc oxide ban on the rising presence of these pathogens.

In our study, conducted at Farm 1, no significant differences in overall fecal scores were observed between treatments, indicating an absence of PWD issues during the trial. Similarly, there were no significant differences in mortality or morbidity between treatments. Notably, the treatment group receiving SDP during phases 1 and 2 exhibited the lowest numerical mortality and culling rates, particularly during phase 2, and required less medication, compared to the treatment group receiving SDP only in phase 1. This suggests that although the reduced protein phase 2 diet may have limited performance gains from SDP, the animals’ health status was improved by including SDP in phase 2 diet. These findings align with the well-documented health benefits associated with SDP [

7,

13]. Similarly, Bailey et al., [

19] feeding pigs with Low CP diet during the first period found that supplementing SDP was correlated with improved intestinal barrier and protein utilization and lower activation of the immune system that resulted in improved performance during that period and lower fecal score.

Additionally, at Farm 2, despite having higher protein levels in the nursery diets, no PWD problems were observed during the study. This suggests that higher dietary protein levels are not necessarily correlated with increased diarrhea incidence, and that other factors, such as farm conditions, management practices, and overall farm status, play critical roles in preventing PWD. Deng et al., [

28] proved that the addition of very digestible animal protein like fish meal, poultry meal or SDP in phases 1, 2 and 3 replacing 0%, 33%, 66% or 100% of soy protein concentrate linearly increased final BW, ADG and ADFI without reporting diarrhea problems, like what we observed in our study. In addition, Bailey et al. [

19] reported improved protein utilization as indicated by lower plasma urea N when pigs were fed normal CP phase 2 diets containing SDP. Therefore, SDP can be considered a key ingredient in nursery diets, effectively addressing the challenge of reducing dietary protein to prevent PWD, while simultaneously improving growth performance, even in the absence of therapeutic levels of zinc oxide.

5. Conclusions

In summary, our results suggest that the prolonged use of low-protein diets in weaning strategies may negatively impact nursery performance. However, the inclusion of SDP as a functional and highly digestible ingredient enables European pig producers to increase protein levels in post-weaning diets without elevating the risk of diarrhea. Incorporating SDP in phase 2 diets not only enhances nursery performance but also it may reduce mortality and the need for medication associated with stress during this critical period. Additionally, the use of SDP supports sustainable farming practices by promoting resource efficiency and reducing the environmental impact of pig production.

These findings underscore the potential of SDP to improve piglet performance and health during the crucial post-weaning phase, providing a viable nutritional strategy to resolve the challenge of using low-protein diets to mitigate the risk of post-weaning diarrhea while avoiding the associated growth restrictions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.P., Y.S., L.B., S.T., J.C. and D.T..; methodology, J.P., L.B. and D.T.; software, L.B., L.S. and D.T.; validation, L.B., L.S., S.T. and D.T.; formal analysis, L.B., L.S., N.T. and D.T.; investigation, L.B., L.S. N.T. and D.T.; resources, J.P., S.T. and D.T.; data curation, L.B., L.S. and D.T.; writing—original draft preparation, J.P., Y.S. and J.C.; writing—review and editing, J.P., Y.S., L.B., L.S., S.T., J.C, N.T. and D.T.; visualization, J.P., S.T. and D.T.; supervision, J.P.; project administration, J.P., S.T. and D.T.; funding acquisition, J.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Funding for this study was provided by APC Europe, S.L.U., Granollers, Spain. We also acknowledge the support of the Spanish Ministry of Industry and Tourism (grant reference PERTE PAG-020100-2023-125).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal involved in this study were raised and treated according to the Directive 2010/63/EU of 22 September 2010, according to the recommendation of the European Commission 2007/526/CE covering the accommodation and care of animals used for experimental and other scientific purposes, and the Spanish guidelines for the care and use of animals in research (B.O.E. number 34, Real Decreto 53/2013).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data from this study are provided in the manuscript. The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have read the journal’s policy, and the authors of this manuscript have the following competing interests: J.P. is employed by APC Europe, S.L.U. Granollers, Spain; Y.S., JC. and J.P. are employed by APC LLC, Ankney, US. Both companies manufacture and sell spray-dried animal plasma. However, the companies had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest. This does not alter the authors’ adherence to all journal policies on sharing data and materials.

References

- Uemura, R.; Katsuge, T.; Sasaki, Y.; Goto, S.; Sueyoshi, M. Effects of zinc supplementation on Shiga toxin 2e-producing Escherichia coli in vitro J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2017, 79(10). 1637–1643.

- Berger, P.I.; Hermanns, S.; Kerner, K.; Schmelz, F.; Schüler, V.; Ewers, C.; Bauerfeind, R.; Doherr, M.G. Cross-sectional study: prevalence of oedema disease Escherichia coli (EDEC) in weaned piglets in Germany at pen and farm levels. Porc. Health Manag. 2023, 9, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhouma, M.; Fairbrother, J.M.; Beaudry, F.; Letellier, A. Post weaning diarrhea in pigs: Risk factors and non-colistin-based control strategies. Acta Vet. Scand. 2017, 59, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Renzhammer, R.; Vetter, S.; Dolezal, M.; Schwarz, L.; Käsbohrer, A.; Ladinig, A. Risk factors associated with post-weaning diarrhoea in Austrian piglet-producing farms. Porc. Health Manag. 2023, 9, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabà., L.; Hulshof, T.G.; Venrooij, K.C.M.; Van Hees, H.M.J. Variability in feed intake the first days following weaning impacts gastrointestinal tract development, feeding patterns, and growth performance in nursery pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 2024, 102, skad419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabler, N.K.; Burrough, E.R. 24 Intestinal function and integrity in health and disease: current knowledge in swine. J. Anim. Sci. 2023, 101 (Suppl. 2), 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Bosque, A.; Miró, L.; Amat, C.; Polo, J.; Moretó, M. The anti-inflammatory effect of spray-dried plasma is mediated by a reduction in mucosal lymphocyte activation and infiltration in a mouse model of intestinal inflammation. Nutrients 2016, 8, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrallardona, D. Spray dried animal plasma as an alternative to antibiotics in weanling pigs—A review. Asian-Australas. J. Anim.Sci 2010, 23, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.M.; Crenshaw, J.D.; Gonzalez-Esquerra, R.; Polo., J. Impact of spray-dried plasma on intestinal health and broiler performance. Microorganisms, 2019; 7, 219. [Google Scholar]

- Henrichs, B.S.; Brost, K.N; Hayes, C.A.; Campbell, J.M.; Drackley, J.K. Effects of spray-dried bovine plasma protein in milk replacers fed at a high plane of nutrition on performance, intestinal permeability, and morbidity of Holstein calves. J Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 7856–7870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadour, H.V.; Parsons, B.W.; Utterback, P.L.; Campbell, J.M.; Parsons, C.M.; Emmert, J.L. Metabolizable energy and amino acid digestibility in spray-dried animal plasma using broiler chick and precision-fed rooster assays. Poult. Sci. 2022, 101, 101807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maijó, L.; Miró, L.; Polo, J.; Campbell, J.; Russell, L.; Crenshaw, J.; Weaver, E.; Moretó, M.; Pérez-Bosque, A. Dietary plasma proteins attenuate the innate immunity response in a mouse model of acute lung injury. Br. J. Nutr. 2011, 107, 867–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balan, P.; Staincliffe, M.; Moughan, P.J. Effects of spray-dried animal plasma on the growth performance of weaned piglets—A review. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2021, 105, 699–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, H.G.; Campbell, J.M.; Lee, J.T. Evaluation of spray-dried plasma in broiler diets with or without bacitracin methylene disalicylate. 2 J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2019, 28, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lallès, J.P.; Boudry, G.; Favier, C.; Le Floc’h, N.; Luron, I.; Montagne, L.; Oswald, I.P.; Pié, S.; Piel, C.; Sève, B. Gut function and dysfunction in young pigs: Physiology. Anim. Res. 2004, 53, 301–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Htoo, J.K.; Araiza, B.A.; Sauer, W.C.; Rademacher, M.; Zhang, Y.; Cervantes, M.; Zijlstra, R.T. Effect of dietary protein content on ileal amino acid digestibility, growth performance, and formation of microbial metabolites in ileal and cecal digesta of early weaned pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 2007, 85, 3303–3312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heo, J.M.; Kim, J.C.; Hansen, C.F.; Mullan, B.P.; Hampson, D.J.; Pluske, J.R. Effects of feeding low protein diets to piglets on plasma urea nitrogen, faecal ammonia nitrogen, the incidence of diarrhoea and performance after weaning. Arch. Anim. Nutr. 2008, 62, 343–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, D.; Zhu, W.; Hang, S. Effects of low-protein diet on the intestinal morphology, digestive enzyme activity, blood urea nitrogen, and gut microbiota and metabolites in weaned pigs. Arch. Anim. Nutr. 2019, 73, 287–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, H.M.; Fanelli, N.S.; Campbell, J.M.; Stein, H.H. Addition of spray-dried plasma in phase 2 diets for weanling pigs improves growth performance, reduces diarrhea incidence, and decreases mucosal pro-inflammatory cytokines. Animals 2024, 14, 2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limbach, J.; Espinosa, C.; Perez Calvo, E.; Stein, H. Effect of dietary crude protein level on growth performance, blood characteristics, and indicators of intestinal health in weanling pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 2021, 99, skab166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Wang, G.; Cai, S.; Zeng, X.; Qiao, S. Advances in low-protein diets for swine. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2018, 9, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelo, P.G.; Rodrigues, L.A.; Gabardo, M.P.; Carvalho, R.M.; Moreno, A.M.; Coura, F.M.; Heinemann, M.B.; Rosa, B.O. , Brustolini, A.P.L.; Araújo, I.C.S.; Fontes, D.O. A dietary spray-dried plasma feeding programme improves growth performance and reduces faecal shedding of nursery pigs challenged with enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli K88. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. (Berl). 2023; 107, 3, 581–588. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, S.; Bidner, T.D.; Payne, R.L.; Southern, L.L. Growth performance of 20- to 50-kilogram pigs fed low-crude-protein diets supplemented with histidine, cystine, glycine, glutamic acid, or arginine. J. Anim. Sci. 2011, 89, 3643–3650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Wei, H.; Cheng, C.; Xiang, Q.; Pang, J.; Peng, J. Supplementation of branched-chain amino acids to a reduced-protein diet improves growth performance in piglets: Involvement of increased feed intake and direct muscle growth-promoting effect. Br. J. Nutr, 2016; 115, 2236–2245. [Google Scholar]

- Bonetti, A.; Tugnoli, B.; Piva, A.; Grilli, E. Towards zero zinc oxide: feeding strategies to manage post-weaning diarrhea in piglets. Animals 2021, 11, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.A.; Mendoza, O.F.; Shull, C.M.; Burrough, E.R.; Spencer, J.D.; Gabler, N.K. ; 142 Evaluation of dietary fiber in health challenged nursery pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 2023, 101 (Suppl. 2), 94–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, D. ¿Dónde están los cerdos que nos faltan? ¿Por qué nos faltan cerdos? In Poceedings of the XLIII Anaporc Congress, Burgos, Spain, 4-5 October 2023.

- Deng, Z.; Duarte, M.E.; Jang, K.B.; Kim, S.W. Soy protein concentrate replacing animal protein supplements and its impacts on intestinal immune status, intestinal oxidative stress status, nutrient digestibility, mucosa-associated microbiota, and growth performance of nursery pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 2022, 100(10), skac255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).