Submitted:

24 October 2025

Posted:

27 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

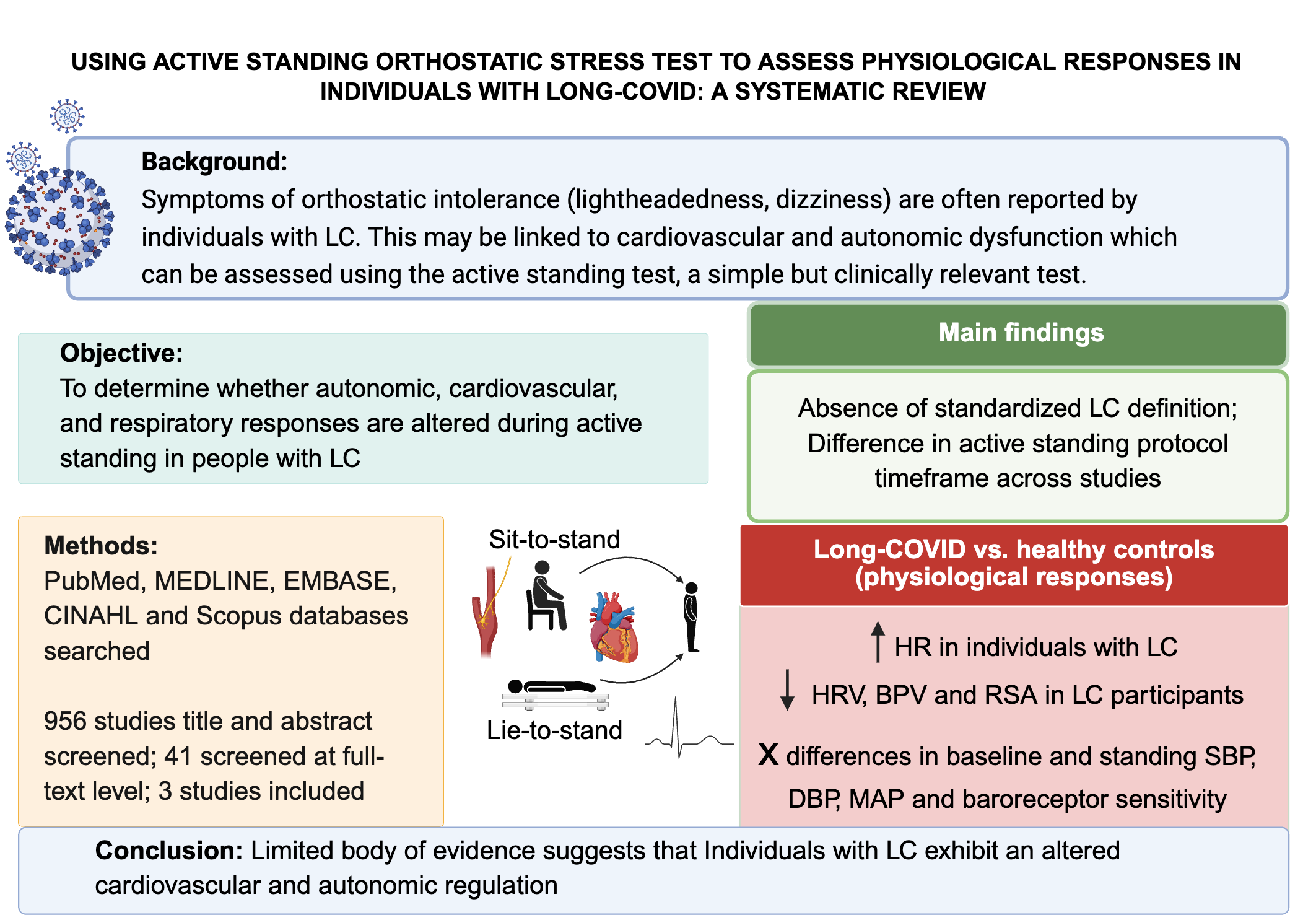

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility and Screening Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Quality and Risk of Bias Assessment

2.5. Data Analysis and Synthesis

3. Results

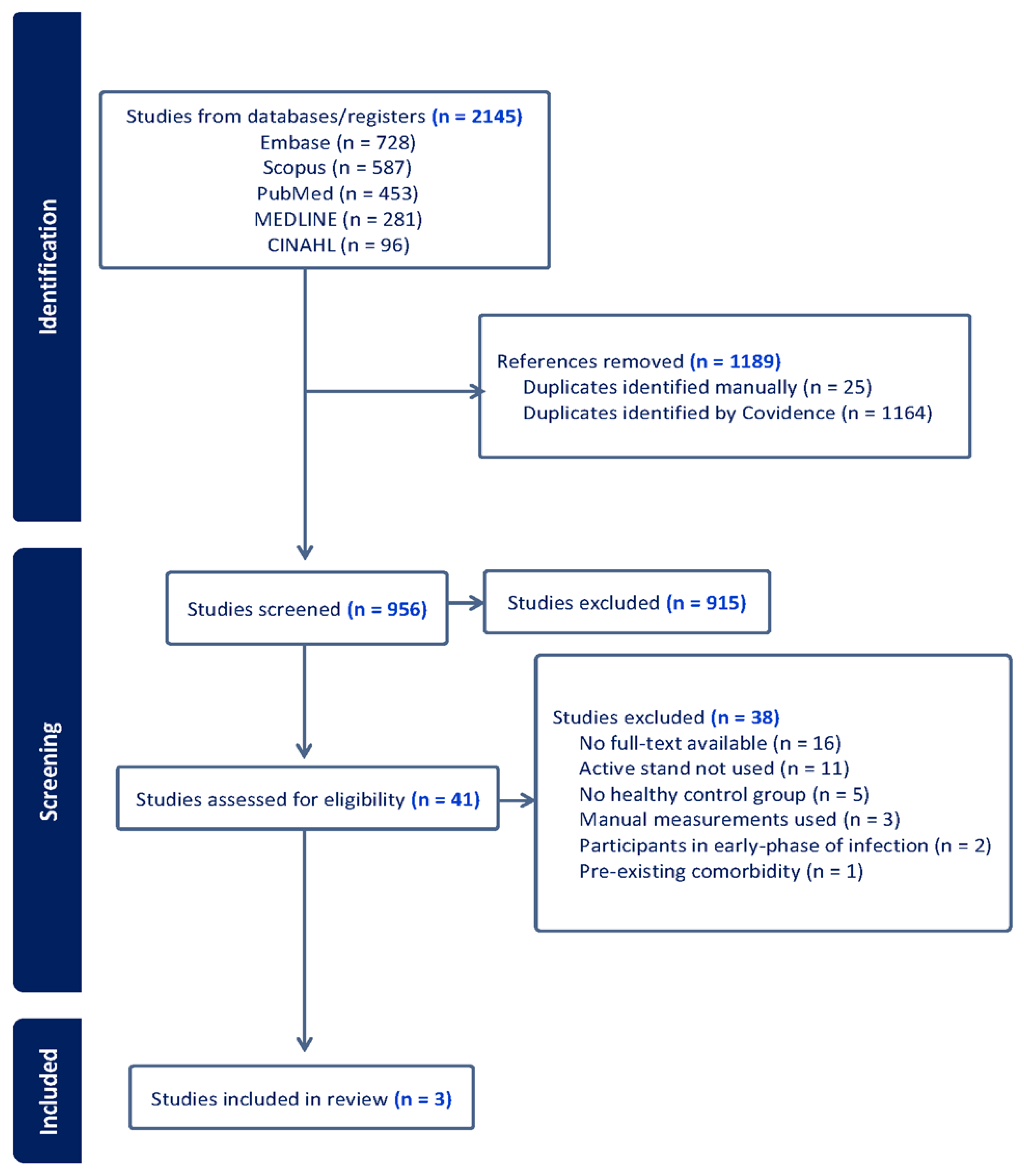

3.1. Study Selection and Search Strategy

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Definitions and Diagnostic Criteria

3.4. Heart Rate Responses

3.5. Blood Pressure Responses

3.6. Time Domain Heart Rate Variability Responses

3.7. Frequency Domain Heart Rate Variability Responses

3.8. Respiratory Responses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Identifying Information

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BRSv | Vagal baroreflex sensitivity |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| DBP | Diastolic blood pressure |

| HC | Health controls |

| HF | High frequency |

| HR | Heart rate |

| HR | Heart rate variability |

| IQR | Inter-quartile range |

| LC | Long-COVID |

| LC-IOH | Long-COVID and initial orthostatic hypotension |

| LC-None | Long-COVID but no abnormalities |

| LC-POTS | Long-COVID and post orthostatic tachycardia syndrome |

| LF | Lower frequency |

| LF/HF ratio | Lower to higher frequency ratio |

| LFSBP | Low-frequency systolic blood pressure |

| MAP | Mean arterial pressure |

| NASEM | National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine |

| NICE | National Institutes for Health and Care Excellence. |

| OH | Orthostatic hypotension |

| PASC | Post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection |

| pNN50 | Percentage of successive R-R intervals differing by more than 50ms |

| POTS | Post orthostatic tachycardia syndrome |

| RMSSD | Root-mean square of successive R-R interval differences |

| SBP | Systolic blood pressure |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SDNN | Standard deviation of R-R intervals |

| TP | Total Power |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. A Long COVID Definition: A Chronic, Systemic Disease State with Profound Consequences; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Soriano, J.B.; Murthy, S.; Marshall, J.C.; Relan, P.; Diaz, J.V. A clinical case definition of post-COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, e102–e107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, H.E.; McCorkell, L.; Vogel, J.M.; Topol, E.J. Long COVID: Major findings, mechanisms and recommendations. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Ramirez, D.C.; Normand, K.; Zhaoyun, Y.; Torres-Castro, R. Long-Term Impact of COVID-19: A Systematic Review of the Literature and Meta-Analysis. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, F.; De Caterina, R.; Fedorowski, A. Orthostatic hypotension epidemiology, prognosis, and treatment. J. AM Coll. Cardiol. 2015, 66, 848–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernon, S.D.; Funk, S.; Bateman, L.; Stoddard, G.J.; Hammer, S.; Sullivan, K.; Bell, J.; Abbaszadeh, S.; Lipkin, W.I.; Komaroff, A.L. Orthostatic Challenge Causes Distinctive Symptomatic, Hemodynamic and Cognitive Responses in Long COVID and Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 917019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormiston, C.K.; Świątkiewicz, I.; Taub, P.R. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome as a sequela of COVID-19. Hear. Rhythm. 2022, 19, 1880–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaghan, A.; Jennings, G.; Xue, F.; Byrne, L.; Duggan, E.; Romero-Ortuno, R. Orthostatic Intolerance in Adults Reporting Long COVID Symptoms Was Not Associated with Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 833650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.; Wieling, W.; Axelrod, F.B.; Benditt, D.G.; Benarroch, E.; Biaggioni, I.; Cheshire, W.P.; Chelimsky, T.; Cortelli, P.; Gibbons, C.H.; et al. Consensus statement on the definition of orthostatic hypotension, neurally mediated syncope and the postural tachycardia syndrome. Clin. Auton. Res. 2011, 21, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diab, A.M.; Carleton, B.C.; Goralski, K.B. COVID-19 pathophysiology and pharmacology: What do we know and how did Canadians respond? A review of Health Canada authorized clinical vaccine and drug trials. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2021, 99, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finucane, C.; van Wijnen, V.K.; Fan, C.W.; Soraghan, C.; Byrne, L.; Westerhof, B.E.; Freeman, R.; Fedorowski, A.; Harms, M.P.M.; Wieling, W.; et al. A practical guide to active stand testing and analysis using continuous beat-to-beat non-invasive blood pressure monitoring. Clin. Auton. Res. 2019, 29, 427–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McJunkin, B.; Rose, B.; Amin, O.; Shah, N.; Sharma, S.; Modi, S.; Kemper, S.; Yousaf, M. Detecting initial orthostatic hypotension: a novel approach. J. Am. Soc. Hypertens. 2015, 9, 365–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dall, P.M.; Kerr, A. Frequency of the sit to stand task: An observational study of free-living adults. Appl. Ergon. 2010, 41, 58–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wieling, W.; Kaufmann, H.; E Claydon, V.; van Wijnen, V.K.; Harms, M.P.M.; Juraschek, S.P.; Thijs, R.D. Diagnosis and treatment of orthostatic hypotension. Lancet Neurol. 2022, 21, 735–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieling, W.; Krediet, C.T.P.; van Dijk, N.; Linzer, M.; Tschakovsky, M.E. Initial orthostatic hypotension: Review of a forgotten condition. Clin. Sci. 2007, 112, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blitshteyn, S.; Whitelaw, S. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) and other autonomic disorders after COVID-19 infection: a case series of 20 patients. Immunol. Res. 2021, 69, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G, J.A.G.-H.; Galarza, E.J.; Fermín, O.V.; González, J.M.N.; Tostado, L.M.F.Á.; Lozano, M.A.E.; Rabasa, C.R.; Alvarado, M.d.R.M. Exaggerated blood pressure elevation in response to orthostatic challenge, a post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC) after hospitalization. Auton. Neurosci. 2023, 247, 103094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osuchowski, M.F.; Winkler, M.S.; Skirecki, T.; Cajander, S.; Shankar-Hari, M.; Lachmann, G.; Monneret, G.; Venet, F.; Bauer, M.; Brunkhorst, F.M.; et al. The COVID-19 puzzle: Deciphering pathophysiology and phenotypes of a new disease entity. Lancet Respir. Med. 2021, 9, 622–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.L.; Whaley, P.; Thayer, K.A.; Schünemann, H.J. Identifying the PECO: A framework for formulating good questions to explore the association of environmental and other exposures with health outcomes. Environ. Int. 2018, 121, 1027–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, G.A.; Shea, B.; O’Connell, D.; Peterson, J.; Welch, V.; Losos, M.; Tugwell, P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomized Studies in Meta-Analyses; Our Research; The Ottawa Hospital Research Institute: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Herzog, R.; Álvarez-Pasquin, M.J.; Díaz, C.; Del Barrio, J.L.; Estrada, J.M.; Gil, Á. Are healthcare workers’ intentions to vaccinate related to their knowledge, beliefs and attitudes? A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modesti, P.A.; Reboldi, G.; Cappuccio, F.P.; Agyemang, C.; Remuzzi, G.; Rapi, S.; Perruolo, E.; Parati, G. Panethnic Differences in Blood Pressure in Europe: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0147601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hira, R.; Baker, J.R.; Siddiqui, T.; Patel, A.; Valani, F.G.A.; Lloyd, M.G.; Floras, J.S.; Morillo, C.A.; Sheldon, R.S.; Raj, S.R.; et al. Attenuated cardiac autonomic function in patients with long-COVID with impaired orthostatic hemodynamics. Clin. Auton. Res. 2025, 35, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seeley, M.-C.; Gallagher, C.; Ong, E.; Langdon, A.; Chieng, J.; Bailey, D.; Page, A.; Lim, H.S.; Lau, D.H. High Incidence of Autonomic Dysfunction and Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome in Patients with Long COVID: Implications for Management and Health Care Planning. Am. J. Med. 2023, 138, 354–361.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, B.; Kunal, S.; Bansal, A.; Jain, J.; Poundrik, S.; Shetty, M.K.; Batra, V.; Chaturvedi, V.; Yusuf, J.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; et al. Heart rate variability as a marker of cardiovascular dysautonomia in post-COVID-19 syndrome using artificial intelligence. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol. J. 2022, 22, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, P.; Mukerji, S.S.; Alabsi, H.S.; Systrom, D.; Marciano, S.P.; Felsenstein, D.; Mullally, W.J.; Pilgrim, D.M. Multisystem Involvement in Post-Acute Sequelae of Coronavirus Disease 19. Ann. Neurol. 2022, 91, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bielecka, E.; Sielatycki, P.; Pietraszko, P.; Zapora-Kurel, A.; Zbroch, E. Elevated Arterial Blood Pressure as a Delayed Complication Following COVID-19—A Narrative Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Campen, C.L.M.C.; Rowe, P.C.; Visser, F.C. Two different hemodynamic responses in ME/CFS patients with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome during head-up tilt testing. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorowski, A.; Olsén, M.F.; Nikesjö, F.; Janson, C.; Bruchfeld, J.; Lerm, M.; Hedman, K. Cardiorespiratory dysautonomia in post-COVID-19 condition: Manifestations, mechanisms and management. J. Intern. Med. 2023, 294, 548–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.S.; Miller, A.J.; Ejaz, A.; Molinger, J.; Goyal, P.; MacLeod, D.B.; Swavely, A.; Wilson, E.; Pergola, M.; Tandri, H.; et al. Cerebral Blood Flow in Orthostatic Intolerance. J. Am. Hear. Assoc. 2025, 14, e036752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Matos, D.G.; de Santana, J.L.; Aidar, F.J.; Cornish, S.M.; Giesbrecht, G.G.; Mendelson, A.A.; Duhamel, T.A.; Villar, R. Cardiovascular regulation during active standing orthostatic stress in older adults living with frailty: A systematic review. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2025, 136, 105894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Study (Year) |

Country |

Study Design |

Sample size |

Proportion of females (%) | Age (mean ± SD, median [IQR])/[CI] (years) | Definition of long-COVID | Active standing protocol (Timeframe) |

Outcome Measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shah et al. (2022) | India | Prospective single center | PASC = 92 HC = 120 |

41% 46% |

PASC = 50.6 ± 12.1 HC = 51.8 ± 4.2 |

Descriptive definition; no organizational source | 5 min supine, 3 min. stand |

Heart rate variability |

| Seeley et al. (2023) | Australia | Prospective comparative | PASC = 30 POTS = 33 HC = 33 |

82% 94% 82% |

PASC = 37 [15] POTS = 28 [14] HC = 28 [23] |

WHO’s Delphi Consensus |

10 min supine, 10 min standing | Respiratory sinus arrhythmia, heart rate and blood pressure responses |

| Hira et al. (2025) | Canada | Cross-sectional | PASC = 94 HC = 33 |

81% 76% |

PASC = 42 [36, 53] HC = 49 [30, 62] |

NICE guideline |

10 min supine, 10 min standing | Heart rate variability, blood pressure variability, Baroreflex sensitivity, Blood pressure and heart rate responses |

| Study (Year) | Supine HR Findings | Standing HR Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Shah et al. (2022) | LC: 88 ± 15 bpm HC: 78 ± 11 bpm p = 0.0001 |

LC-OH: 99 ± 18 bpm No-OH: 86 ± 14 bpm p = 0.006 HC: not reported. |

| Seeley et al. (2023) | PASC: 72 ± 13 bpm POTS: 79 ± 12 bpm HC: 68 ± 9 bpm Group (p = 0.003) PASC > HC (p = 0.05) PASC < POTS p: not reported |

∆HR (0-10 min) PASC: 36 [30–47] bpm POTS: 46 [34–59] bpm HC: 15 [9–20] bpm Group (p = 0.001) PASC > HC (p = 0.001) PASC ~ POTS (p = 0.1) |

| Hira et al. (2025) | LC: 67 [62–75] bpm HC: 61 [56–70] bpm p = 0.01 Subgroups: LC-IOH: 67 [61–77] bpm LC-POTS: 68 [65–75] bpm LC-none: 63 [57–73] bpm HC: 61 [56–70] bpm Group (p = 0.023) LC-none ~ HC (p = 0.999) LC-none ~ LC-POTS (p = 0.283) LC-none ~ LC-IOH (p = 0.063) LC-POTS ~ LC-IOH (p = 0.999) |

LC: 89 [77–106] bpm HC: 78 [69–87] bpm p = 0.001 Subgroups: LC-IOH: 85 [77–93] bpm LC-POTS: 114 [103–131] bpm LC-none: 80 [70–88] bpm HC: 78 [69–87] bpm Group (p < 0.001) LC-none ~ HC (p = 0.999) LC-none < LC-POTS (p = 0.001) LC-none ~ LC- IOH (p = 0.279) LC-POTS > LC-IOH (p = 0.001) |

| Variable |

Shah et al. (2022) |

Seeley et al. (2023) |

Hira et al. (2025) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SBP-supine (mmHg) | Absolute values not reported | No significant group differences (p = 0.12). No absolute values reported |

LC: 119 [109–132] mmHg HC: 119 [114–124] mmHg p = 0.683. Subgroup: LC-IOH: 130 [123–143] mmHg LC-none: 113 [105–119] mmHg LC-POTS: 112 [103–123] mmHg LC-IOH > LC-none (p = 0.001). LC-IOH > LC-POTS (p = 0.001). |

| DBP-supine (mmHg) | Absolute values not reported | No data reported for DBP in supine | LC: 71 [64–77] mmHg HC: 67 [64–72] mmHg p = 0.065 Subgroup: LC-IOH: 76 [67–79] mmHg LC-none: 67 [63–73] mmHg LC-POTS: 66 [63–73] mmHg LC-IOH > LC-none (p = 0.001). LC-IOH > LC-POTS (p = 0.009). |

| MAP-supine (mmHg) | Not reported | Not reported | LC: 87 [80–95] mmHg HC: 85 [80–91] mmHg p = 0.268 Subgroup: LC-IOH: 94 [87–100] mmHg LC-none: 81 [78–89] mmHg LC-POTS: 81 [77–92] mmHg LC-IOH > LC-none (p = 0.001). LC-IOH > LC-POTS (p = 0.001). |

|

LFSBP supine (mmHg²) |

Not reported | Not reported | LC: 4.06 [2.69–6.62] mmHg² HC: 5.15 [3.77–9.37] mmHg² LC-none < HC (p = 0.001) |

| Variable | (Shah et al., 2022) | (Hira et al., 2025) |

|---|---|---|

| RMSSD | LC:13.9 ± 11.8 ms HC: 19.9 ± 19.5 ms LC < Controls (p = 0.01) Subgroup: Graded reduction by COVID severity (p = 0.0001) Asymptomatic: 24.2 ms Mild: 16.3 ms Moderate: 9.3 ms Severe: 7.2 ms |

Supine: No significant group-level differences. Standing: LC: 15 [8.9–22] ms HC: 18 [13–32] ms LC < HC (p = 0.011). Subgroup: LC-IOH: 15 [9.60–27] ms LC-none: 19 [16–38] ms LC-POTS: 9.72 [7.37–13] ms LC-POTS < LC-none (p = 0.001) LC-POTS < LC-IOH (p = 0.024) |

| SDNN | LC: 16.9 ± 12.9 ms HC: 22.5 ± 17.6 ms LC < Controls (p = 0.01) |

Supine: No significant group-level differences. Standing: LC: 31 [22–43] ms HC: 40 [32–55] ms; LC < HC (p = 0.001). Subgroup: LC-none: 37 [28–51] ms LC-POTS: 27 [20–33] ms LC-POTS < LC-none (p = 0.018) |

| pNN50 | Not reported |

Supine: No significant group-level differences. Standing: LC: 0.23 [0–0.87] ms HC: 0.78 [0.11–2.72] ms LC < HC (p = 0.011).Subgroup: LC-IOH: 2.46 [0.32–7.44]% LC-none: 0.83 [0–2.50]% LC-POTS: 8.12 [3.10–13]% LC-POTS > LC-none (p = 0.039) LC-POTS > LC-IOH (p = 0.026) |

| Variable | Supine Findings | Standing Findings |

|---|---|---|

| HF | No significant difference between LC and HC. Subgroup: HC: 1136 [262–3121] ms2 LC-none: 1919 [725–4921] ms2 LC-IOH: 1384 [339–2036]ms2 LC-POTS: 2166 [1112–4419] ms² Group (p = 0.026) LC-POTS > LC-IOH (p = 0.028) |

LC: 315 [95–730] ms² HC: 349 [260–1190] ms² LC < HC (p = 0.042) Subgroup: HC: 349 [260–1190] ms2 LC-none: 578 [337–1881] ms2 LC-IOH: 296 [98–871 ]ms2 LC-POTS: 100 [51–339] ms² Group (p < 0.001) LC-none > LC-POTS (p = 0.001). |

| LF | No significant differences between LC and HC. Subgroup: HC: 1484 [603–4210] ms² LC-none: 2130 [1142–4393] ms2 LC-IOH: 1429 [643–2778] ms2 LC-POTS: 2680 [1889–4938] ms² Group (p = 0.015) LC-POTS > LC-IOH (p = 0.012) |

LC: 1203 [483–2212] ms² HC: 1901 [935–4008] ms² LC < HC (p = 0.008) Subgroup: HC: 1901 [935–4008] ms² LC-none: 1806 [1106–3932] ms2 LC-IOH: 974 [428–1941] ms2 LC-POTS: 1080 [298–1671] ms² Group (p = 0.001) LC-POTS < LC-none (p = 0.020) |

| TP | No significant differences between LC and HC. Subgroup: HC: 689 [2547–17839] ms² LC-none: 7702 [4681–14480] ms2 LC-IOH: 5975 [3321–11206] ms2 LC-POTS: 9415 [5096–16398] ms² Group (p = 0.057) LC-POTS > LC-IOH (p = 0.030) |

LC: 3313 [1773–5559] ms² HC: 5342 [3410–10550] ms² LC < HC (p < 0.001) Subgroup: HC: 5342 [3410–10550] ms² LC-none: 4938 [301–9406] ms2 LC-IOH: 3269 [1757–5130] ms2 LC-POTS: 2619 [1413–3949] ms² Group (p = 0.001) LC-POTS < LC-none (p = 0.006) |

| BRSv | No significant differences between LC and HC. Subgroup: HC: 6.89 [4.94–11.4] ms/mmHg LC-none: 10.7 [5.35–17.0] ms/mmHg LC-IOH: 6.24 [4.11–10.0] ms/mmHg LC-POTS: 9.81 [8.47–16.0] ms/mmHg Group (p = 0.001) LC-POTS > LC-IOH (p = 0.010) LC-IOH > LC-none (p = 0.001) |

No significant differences between LC and controls. Subgroup: Controls: 3.97 [2.93–6.41] ms/mmHg] LC-none: 5.33 [3.34–7.06] ms/mmHg LC-IOH: 2.77 [1.76–5.11] ms/mmHg LC-POTS: 2.85 [1.44–3.93] ms/mmHg Group p = 0.001 LC-POTS < LC-none (p = 0.001) LC-IOH < LC-none (p = 0.005) |

| LF/HF ratio | No significant differences between groups or subgroups. | No significant differences between groups or subgroups. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).