1. Introduction

Transitioning from supine or sitting to a standing upright posture is marked by a rapid transient drop in blood pressure (BP), generating a stimulus for the autonomic nervous system (ANS) to compensate for this BP drop [

1,

2]. This hemodynamic challenge activates compensatory mechanisms, including an increase in sympathetic activity and a reduction in parasympathetic tone [

3]. These responses facilitate vasoconstriction and an increase in heart rate (HR), contributing to the rapid short-term compensatory BP response and maintenance of cerebral perfusion and brain blood flow [

4,

5].

As we age, the ANS undergoes a gradual decline that impacts its response during postural transitions [

6]. This age-related autonomic change is characterized by compromised baroreceptor sensitivity to activate the sympathetic nervous system [

7]. Also, the decline in vagal tone further limits the rapid withdrawal of parasympathetic influence necessary for a timely HR increase [

5]. Additionally, decreased responsiveness of adrenergic receptors in the heart and vasculature contributes to a less effective sympathetic output [

7]. Changes in chemoreceptor function and a decline in muscle pump further contribute to the inability to counteract orthostatic stress [

5,

7]. A delayed onset of these mechanisms can result in prolonged hypotension during postural transitions, elevating the risk of dizziness, lightheadedness, altered vision from retinal hypoperfusion, and falls [

5].

Heart rate variability (HRV) is a key marker of autonomic balance that reflects the interplay between sympathetic and parasympathetic activity [

8]. In older adults, HRV is generally reported to be reduced, indicating diminished parasympathetic modulation and impaired autonomic response [

8]. Although studies suggest a decline in HRV with aging [

9,

10], the literature remains inconclusive, as some findings indicate that HRV parameters, such as root mean square successive difference (RMSSD) and standard deviation of R-R intervals (SDRR), may be preserved in healthy older individuals [

11,

12].

Another factor related to older adults is the deterioration of the cardiac parasympathetic modulation (CPM), in which the ∆HR 30:15 ratio can be used as a marker of this deterioration [

13]. Despite its established relevance in assessing autonomic function [

13], its role in BP regulation during active standing orthostatic stress has not been thoroughly investigated in older adults. To date, no studies have specifically examined autonomic responses through a CPM analysis during active standing orthostatic stress using a lower gravitational stress (sit-to-stand) and a higher gravitational stress (lie-to-stand) , comparing older adults and younger adults.

As we get older, the function of baroreceptors, primary sensors for BP fluctuations, becomes impaired, which significantly contributes to the overall reduction in autonomic responses [

14]. Evidence has shown that, in older adults, BP regulation can be challenging during standing due to the decline in baroreceptor sensitivity (stretch receptors located in the aortic arch and carotid sinus) and cardiac baroreflex gain [

14,

15,

16]. Although existing literature has emphasized the key role of baroreflex in hemodynamic regulation, studies have yet to investigate their response across specific time intervals following active standing. To address this gap, our study analyzed cardiac baroreflex gain (CBG) in four critical specific phase time points 30s (phase 1), 60s (phase 2), 180s (phase 3), and 420s (phase 4), with the aim of determining whether the ANS can regulate BP (indicating preserved function) and how it compensates when function is impaired.

This study primarily aimed to (1) describe and compare HRV at baseline, (2) assess CPM response immediately on standing (∆HR 30:15), and (3) evaluate CBG responses at 30s (phase 1), 60s (phase 2), 180s (phase 3), and 420s (phase 4): when transitioning from (1) sit-to-stand (lower orthostatic stress challenge) and (2) lie-to-stand (higher orthostatic stress challenge). Secondarily, it also aimed to (4) compare the incidence of OI symptoms between younger and older adults. To address these objectives, we formulated four hypotheses: compared to younger adults, older adults will show (i) a lower HRV (time and frequency domains); (ii) greater CPM (∆HR 30:15) on standing; (iii) reduced CBG, particularly at 30s (phase 1) and 60 s (phase 2), but no differences are anticipated at 180s (phase 3) and 420 s (phase 4). At this point, the CBG responses are sufficient to bring hemodynamic parameters to more stable values. (iv) Older adults will report a higher incidence of OI symptoms than younger adults. The observed responses in older adults can be attributed to age-related deterioration in autonomic regulatory mechanisms, an imbalance between sympathetic and parasympathetic influences, increased CPM, and a reduction in baroreceptor-mediated autonomic control, resulting in a higher incidence of OI symptoms.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This was an observational cross-sectional study that adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) [

17] and the Sex and Gender Equity in Research (SAGER) [

18] reporting guidelines.

2.2. Settings

This study took place at the Applied Research Centre within the Faculty of Kinesiology and Recreation Management at the University of Manitoba between August 2022 and August 2023. Ethical approval was granted by the University of Manitoba Health Research Ethics Board (approval number - HE2022-0058).

2.3. Participants

A convenience sampling strategy was employed to recruit participants. Older adults were drawn from Dr. Todd Duhamel's database at the University of Manitoba -which comprises ~1,000 females who previously participated in the Women's Advanced Risk-assessment in Manitoba (WARM) Hearts study - as well as from the Centre on Aging database (University of Manitoba), and in-person visits to Men's Shed and retirement or care homes in Winnipeg. For younger adults, recruitment was done by telephone, email, social media platforms (including Facebook, Instagram, and X), advertisements, flyers, posters, and word of mouth.

The sample included both male and female participants divided into two distinct age groups: younger adults (18-30 years) and older adults (60-79 years). Eligibility required that individuals be in these specific age ranges and identify their sex at birth as either female or male. Participants with a history of cardiovascular conditions, such as ischemic heart disease, acute myocardial infarction, stroke, percutaneous coronary intervention, coronary artery bypass surgery, congestive heart failure, psychiatric disorders, and severe cognitive impairment, or who were pregnant, were excluded from the study.

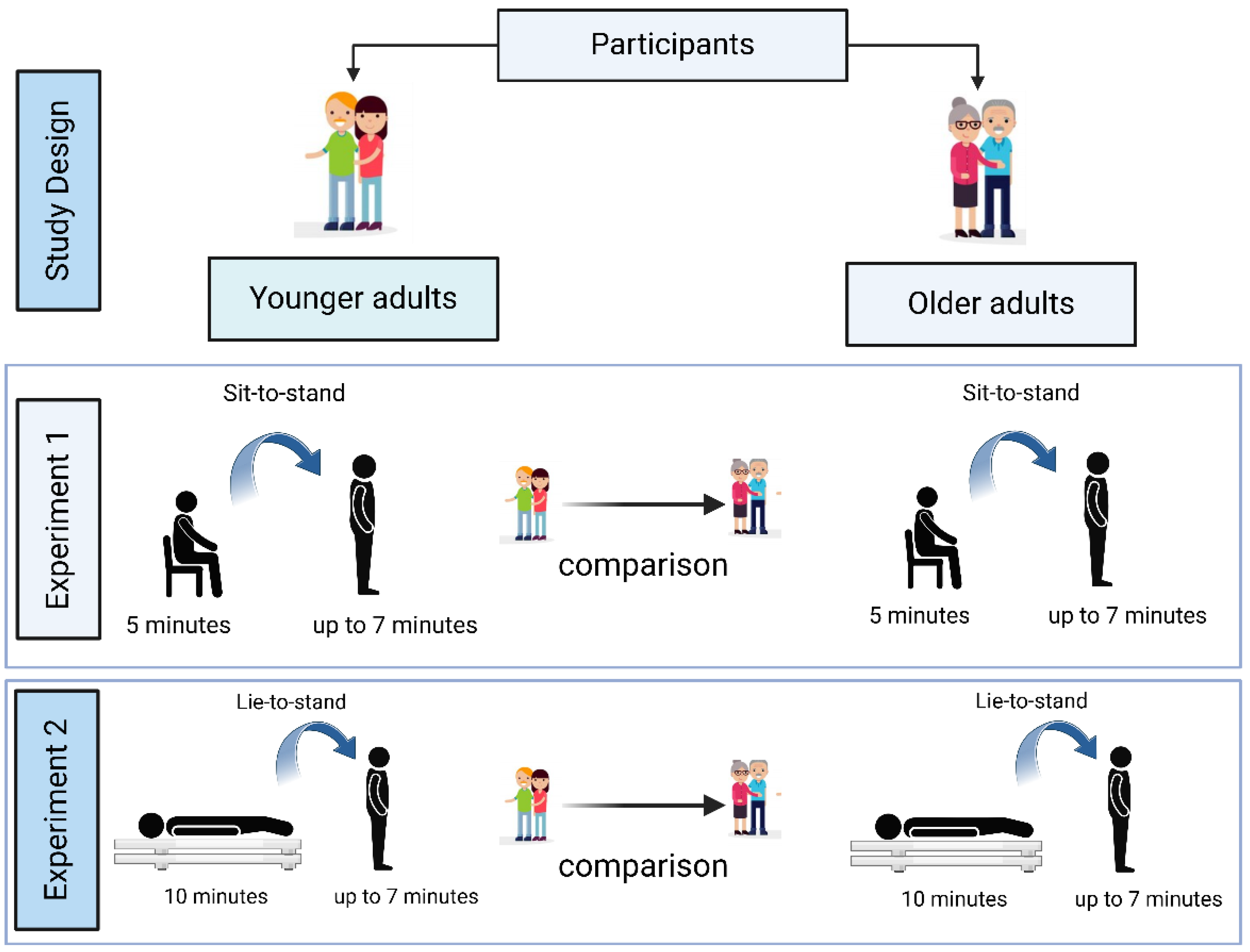

Eighty-eight participants underwent orthostatic stress challenges in two experimental conditions: sit-to-stand (Experiment 1) and lie-to-stand (Experiment 2) (

Figure 1).

2.4. Data Collection

Participants were given preparatory instructions 48 hours before their appointment. Upon arrival, they read and signed an informed consent form. Before the assessments, a trained researcher measured resting HR and BP to verify that each participant met the safety criteria outlined by the Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology (CSEP) guidelines [

19].

After obtaining informed consent and completing familiarization procedures, participants performed two active standing orthostatic stress tests (sit-to-stand and lie-to-stand) with BP measured continuously on a beat-by-beat basis using a FinometerTM Pro Device (Finapres Medical System BV, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). Immediately following the test, participants were asked about any symptoms such as dizziness, light-headedness, or faintness to assess orthostatic intolerance (OI). All assessments were conducted in a quiet room maintained at 22.0 ± 1.0°C with humidity and barometric pressure at ambient. Testing occurred on weekdays between 8:30 and 11:30 am to minimize circadian cycle influences. The order of the sit-to-stand and lie-to-stand conditions was randomized and counterbalanced among participants.

2.4.1. Demographic and Anthropometric Measurements

Demographic information, including sex assigned at birth, age, and date of birth, was collected to characterize the sample. In addition, anthropometric and body composition assessments were conducted. Body mass (kg) was measured using an InBody© 270 device (InBody CO., Ltd, Cerritos, CA, USA), and height (m) was measured using a mobile stadiometer (SECA, Frankfurt, Germany).

2.4.2. Assessment of Heart Rate Variability, Cardiac Parasympathetic Modulation, and Cardiac Baroreflex Gain

HRV, CPM, and CBG were obtained by extracting information from the electrocardiogram (ECG) and Finometer (Finapres Medical System, Arnhem, The Netherlands) [

20] and recorded using LabChart 8.0 (ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, USA) at a sampling frequency of 1 kHz. The ECG signals were subjected to a 5-30 Hz bandpass filter for R peak detection, except during the 30 seconds before and 90 seconds after standing, when the raw signal was preserved and Finometer calibration was manually disabled. Cardiovascular parameters during the sit-to-stand and lie-to-stand tests were analyzed with a custom macro for R-R interval detection. The R-R intervals obtained from the ECG served as the basis for HR calculation.

Arterial pressure was recorded non-invasively via photoplethysmography at the middle finger of the left hand (Finometer - Finapres Medical System, Arnhem, The Netherlands) [

20]. BP calibration was initially performed using the manufacturer’s standard protocol and subsequently refined through manual calibration with an automated BP monitor (ARSIMAI, BSX516, Munster, Germany). Approximately five minutes before each procedure, finger and brachial pressures were adjusted using the return-to-flow calibration. Finger circumference was measured to select the appropriate cuff size. The height correction system was used to adjust the reconstructed BP from the finger arterial pressure wave to the brachial arterial pressure wave (heart) throughout the assessments.

Systolic blood pressure (SBP) and HR data were then stored and transferred to a custom Matlab application (Matlab R2024; The MathWorks Inc, Natick, MA, USA). Once the data were imported from LabChart into the Matlab application, noise and motion artifacts were filtered using a two-step process. Initially, a median filter was applied, followed by a low-pass filter with a cutoff frequency of 0.05 rad/sample, as determined by scalogram analysis. Lastly, a 5-second moving average filter was employed to smooth the signal and isolate the parameters of interest [

21,

22]. Following data import, interpolation was applied to correct for delays induced by resampling at 1 Hz. The onset of active standing was defined as time zero, with baseline values assigned as negative and positive values representing short-term compensatory responses.

2.4.3. Heart Rate Variability

HRV was obtained by continuous beat-by-beat measurements during supine position using a three-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) module collected at a 1 kHz sampling rate (Finometer, Finapres Medical System, Arnhem, The Netherlands) according to the guidelines from the

European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing Electrophysiology [

23]. HRV data were analyzed in time and frequency domains using at least 5 minutes or a window of ≥ 256 beats. The HRV data was preprocessed through the HRV module (LabChart 8, ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, USA). The module detects and extracts RR intervals and automatically differentiates between normal and ectopic beats. In the time domain, mean RR intervals, the standard deviation of RR intervals (SDRR), and the root mean square of successive RR intervals (RMSSD) were assessed to evaluate the sympathetic and parasympathetic activity. Spectral analysis of frequency domain variables was estimated using the Fast Fourier transform model. Low-frequency (LF) (0.04-0.15 Hz) and high-frequency (HF) (0.15-0.45 Hz) spectral components were collected in absolute values of power (ms

2). The low-frequency/high-frequency ratio (LF/HF) was calculated from the absolute values of LF and HF.

2.4.4. Cardiac Parasympathetic Modulation

Cardiac parasympathetic modulation (CPM) was measured using the HR 30:15 ratio of the minimum and maximum HR around the 30

th and 15

th heartbeats after standing [

13]. The HR used for the CPM calculation was obtained from the R-R intervals (ECG- module, Finometer, Finapres Medical System, Arnhem, The Netherlands). This measurement is generally used in clinical settings to assess the autonomic cardiovascular reflex function and detect early signs of autonomic dysfunctions [

24,

25]. It provides insight into the heart’s ability to respond to stress (e.g., postural transition), which could support the diagnosis of conditions that can affect cardiovascular stability, mainly in people with underlying health issues [

24,

25].

2.4.5. Cardiac Baroreflex Gain

Cardiac baroreflex gain (CBG) was adapted from the proposed method by the Autonomic Disorders Consortium [

26] by calculating the change in HR divided by the drop in SBP (ΔHR/ΔSBP ratio) divided into four critical specific phase time points: 30 s (phase 1), 60 s (phase 2), 180 s (phase 3), and 420 s (phase 4) after active standing orthostatic stress, expressed as bpm.mmHg

-1 [

26]. This phase-specific assessment of adaptive CBG responses identifies differences in autonomic regulation during the short-term compensatory responses. The HR used for this calculation was obtained from the R-R intervals (ECG - module, Finometer, Finapres Medical System, Arnhem, The Netherlands). SBP was obtained from the arterial pressure non-invasively via photoplethysmography at the middle finger of the left hand (Finometer, Finapres Medical System, Arnhem, The Netherlands) [

20]. Calibration procedures (return-to-flow and finger and brachial arterial pressures adjustments), appropriate cuff size, and height correction system adjustments were the same as previously described. CBG assessment is typically used in clinical settings for evaluating BP regulation during active standing, identifying issues with autonomic control that could lead to orthostatic intolerance (e.g., dizziness) [

27].

2.5. Sample Size

The sample size was determined a priori using the G*Power software (Heinrich Heine University, Dusseldorf, Germany) [

28], based on data obtained from an internal pilot with 16 participants and equal distribution between groups. A t-test (two independent means) comparing the differences in the CPM (HR 30:15), derived from the minimum and maximum HR observed around the 30

th and 15

th beats after standing, with an α level of 0.05. For the sit-to-stand experiment, the analysis indicated a statistical power of 0.81 and an effect size of 1.17, based on mean ± SD values of 0.87 ± 0.06 for younger adults and 0.93 ± 0.04 for older adults, which resulted in an estimated total sample of 20 participants (10 per group). In the lie-to-stand experiment, the estimated power was 0.80 with an effect size of 1.74, using mean ± SD values of 0.82 ± 0.07 for younger adults and 0.91 ± 0.02 for older adults, resulting in a total of 10 participants (5 per group).

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Data normality was evaluated using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Variables with a parametric distribution were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) along with the corresponding 95% confidence interval (95% CI), while non-parametric variables were summarized as the median with interquartile range (IQR) and their minimum and maximum values. For sample characterization, continuous data was presented using these descriptive statistics, and categorical data were reported as absolute numbers and relative percentages. Additionally, the Chi-Square test was utilized to assess differences in categorical variables.

An unpaired Student t-test was used to compare differences between the younger adults and older adults for both the sit-to-stand and lie-to-stand conditions, while the Mann-Whitney U test was applied to non-parametric data. To control for multiple comparisons,

p-values were adjusted using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure with a false discovery rate of 0.05, thereby limiting the expected proportion of false positives among significant findings [

29]. Significant results were reported based on the corrected

p-values, highlighting the tests that met the adjusted threshold of

p < 0.05.

Effect sizes were calculated using Cohen’s

d for parametric data [

30] and by the R coefficient (non-parametric data) [

31] with classifications set as low (≤0.05), medium (0.06–0.25), high (0.26–0.50), and very high (>0.50) [

30]. All analyses were done using R

® (Version 4.1.1, Vienna, Austria).

3. Results

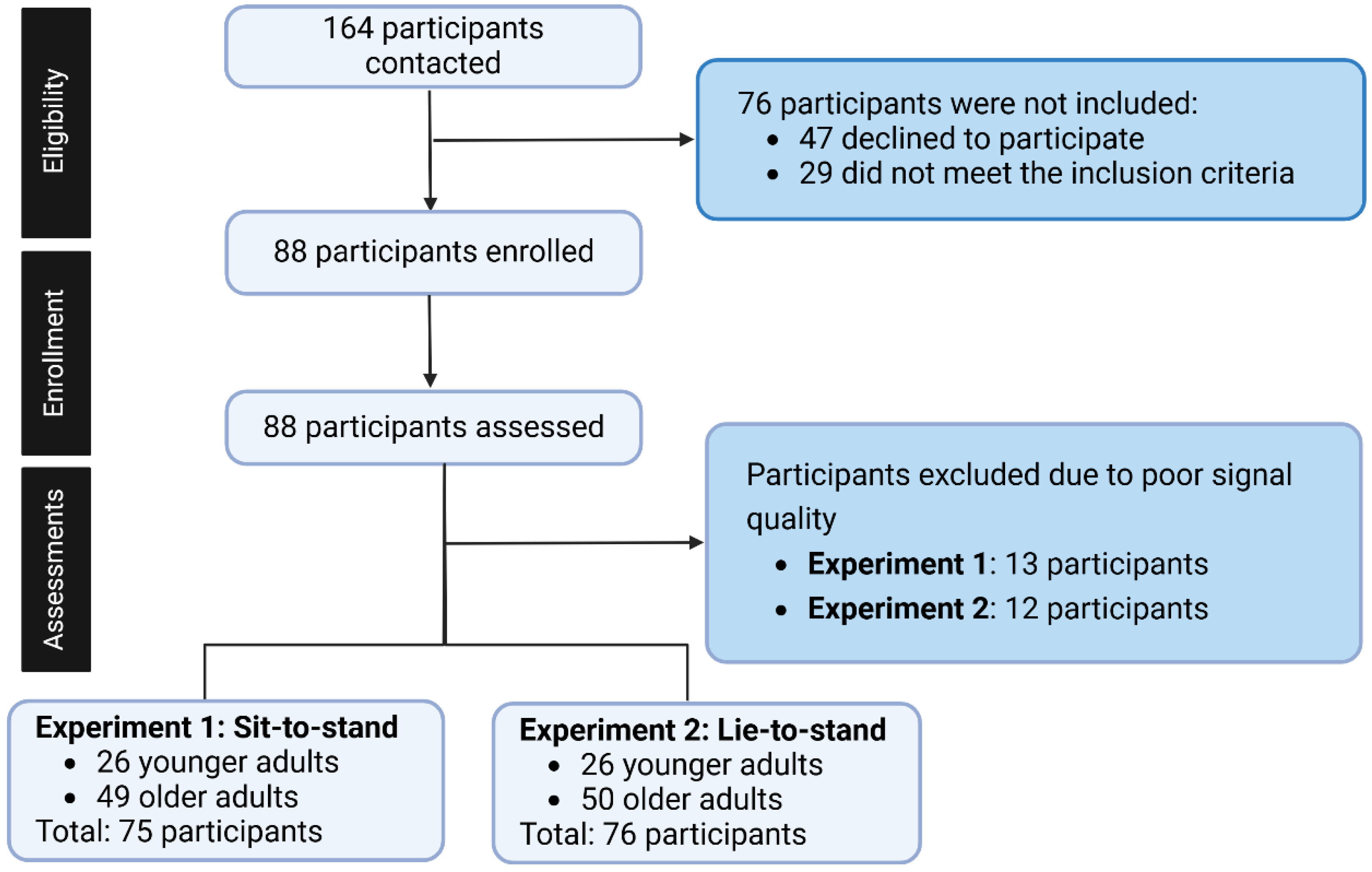

Eligibility was assessed using a screening questionnaire developed by our research team to evaluate each participant’s health status. Due to poor signal quality, 13 participants were excluded from Experiment 1 and 12 from Experiment 2. As a result, Experiment 1 included 26 younger adults and 49 older adults, while Experiment 2 consisted of 26 younger adults and 50 older adults. HRV at baseline, CPM (HR 30:15) immediately on standing, and CBG at 30 s, 60 s, 180 s, and 420 s were compared between younger adults and older adults in experiments 1 and 2 (

Figure 2).

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of younger adults (18 - 30 years) and older adults (60 - 79 years) for sex distribution, anthropometric measurements, and the incidence of OI. Younger adults had an equal distribution of females and males in both experiments. For experiment 1, 71.5% of the older adults were female, and 28.5% were male, whereas in experiment 2, 70% were female and 30% were male. Older adults exhibited a higher body mass index (BMI) and shorter stature compared to younger adults, although no significant differences in body mass were observed. Additionally, older adults were more likely to experience OI than younger adults.

Table 2 presents HRV responses in the time and frequency domains comparing younger adults and older adults at baseline in the supine position. Older adults exhibited lower SDRR and RMSSD (time domain), lower LF and HF, and higher LF/HF ratio (frequency domain) compared with younger adults. There were no statistically significant differences in RR intervals between groups.

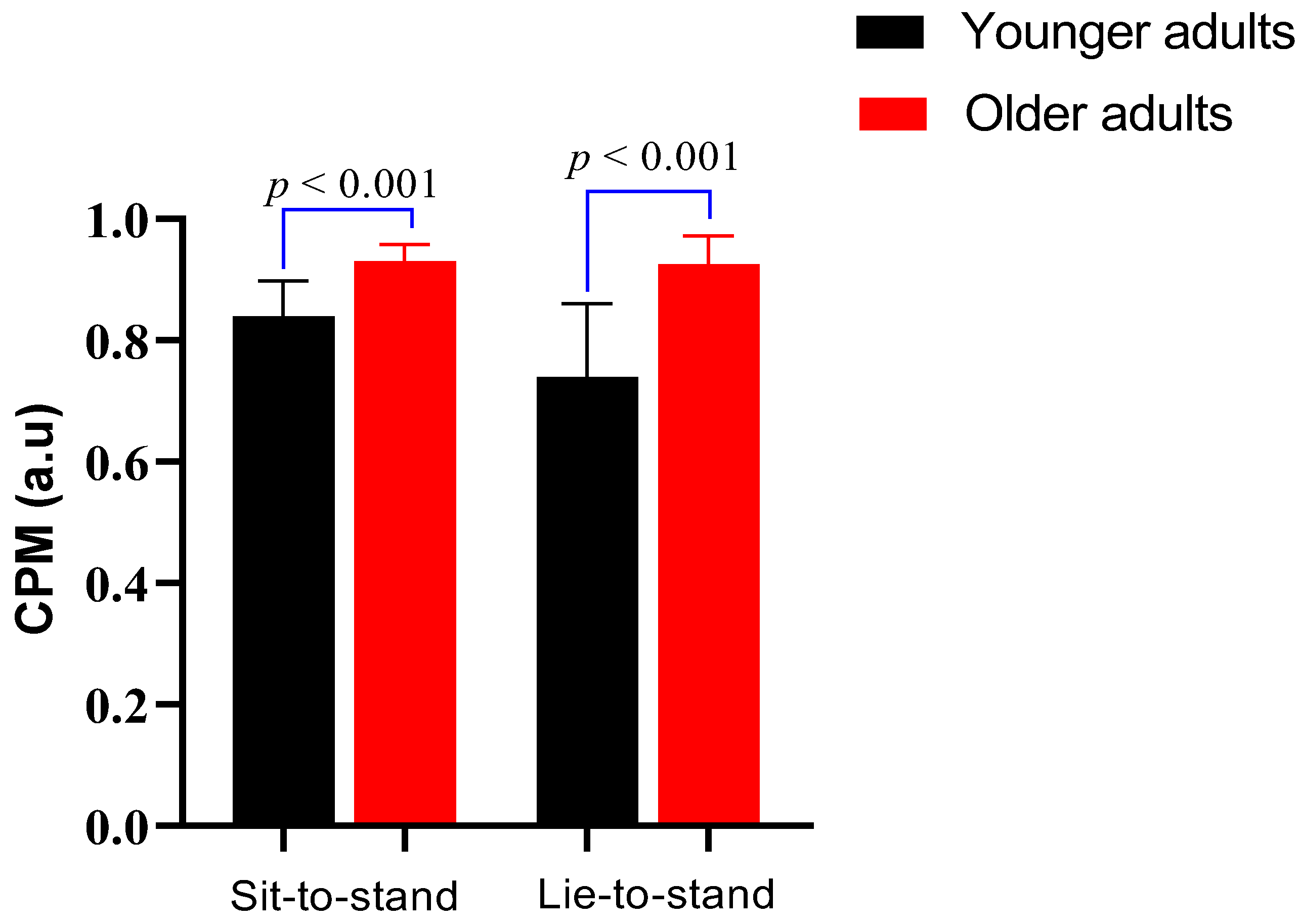

3.2. Cardiac Parasympathetic Modulation Responses During Active Standing Orthostatic Stress

Figure 3 shows the CPM comparison between younger adults and older adults during the sit-to-stand and lie-to-stand transitions. During the sit-to-stand test (lower orthostatic stress challenge), CPM was exhibited as median values with interquartile range. Older adults had a significantly higher CPM (0.9, IQR: 0.1) compared to younger adults (0.8, IQR: 0.1) (

p < 0.001). During the lie-to-stand test (higher orthostatic stress challenge), CPM was expressed as a mean and standard deviation. Older adults showed a higher CPM (0.9 ± 0.1) than younger adults (0.7 ± 0.1) (

p < 0.001).

3.3. Cardiac Baroreflex Gain Responses During Active Standing Orthostatic Stress Across Specific Phase Time Points

In the sit-to-stand transition, no differences in phase 1 (0-30s) were observed between groups. However, older adults showed lower CBG values from phases 2-4 (30-420 s). In the lie-to-stand, older adults showed lower CBG values in phases 3 (60-180 s) and 4 (300-420 s), but no differences in phases 1 (0-30 s) and 2 (30-60 s) (

Table 3).

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to analyze together HRV (time and frequency domains), CPM (ΔHR 30:15) and CBG across distinct specific phase time points comparing older adults and younger adults during two distinct active-standing orthostatic stresses: sit-to-stand and lie-to-stand. Our findings indicate that older adults had reduced autonomic activity measured through the HRV, higher CPM, lower CBG from phases 2-4, and higher symptoms of OI.

4.1. Heart Rate Variability Responses

In the time domain analysis, there were no statistically significant differences between older adults and younger adults in RR intervals during both transitions. Kawaguichi et al. [

33] reported no statistically significant differences in RR intervals at baseline between older adults and younger adults, supporting the results of the current study. Additionally, in this study, older adults exhibited lower SDRR and RMSSD compared to younger adults in both conditions, which corroborated the results of Grassler et al. [

34] and Kawaguchi et al. [

33].

The reduced SDRR and RMSSD observed in older adults in our study indicate a decline in HRV, which is commonly associated with diminished parasympathetic modulation [

8]. Our data shows significantly lower SDRR and RMSSD values in older adults compared to younger adults, supporting the understanding of reduced vagal tone in older adults [

35]. This diminished vagal tone is particularly relevant during postural transitions, where parasympathetic withdrawal and sympathetic activation must occur in a coordinated manner to maintain autonomic regulation [

8].

In the frequency domain, our results showed that older adults exhibited lower LF and HF power compared to younger adults in both postural transitions, along with a higher LF/HF ratio. These findings align with those of Grassler et al., [

34], who reported significantly reduced LF and HF power in older adults compared to younger adults. Similarly, Kawaguchi et al., [

33] also observed that older adults had lower LF and HF compared to younger individuals, along with a higher LF/HF ratio in older adults than in younger adults. The reduction in LF and HF power in older adults suggests an overall decline in autonomic activity [

8]. A lower LF indicates reduced sympathetic modulation and diminished baroreflex sensitivity, while a lower HF reflects impaired parasympathetic activity [

36]. The higher LF/HF ratio observed in older adults points to a shift towards sympathetic dominance and reduced vagal tone. This shift is associated with reduced CBG and a greater likelihood of OI, as observed in our results.

4.2. Cardiac Parasympathetic Modulation

The ∆HR 30:15 ratio, a marker of autonomic cardiovascular reflex function, was analyzed in this study, being the first comparison of this variable between older adults and younger adults. In both conditions, older adults exhibited a higher CPM compared to younger adults. The elevated ∆ HR 30:15 ratio observed in older adults in our study suggests a slower withdrawal of parasympathetic tone and delayed activation of the sympathetic nervous system during active standing orthostatic stress. This autonomic imbalance impairs the rapid cardiovascular adjustments necessary to maintain adequate perfusion pressure, particularly during the early phases of orthostatic stress [

4,

37]. The reduced ability to promptly engage in sympathetic activity compromises HR and vascular resistance responses [

5]. This might contribute to greater transient drops in BP and increase the risk of OH and OI in older individuals [

4].

4.3. Cardiac Baroreflex Gain Responses Across Specific Phase Time Points During Active Standing Orthostatic Stress

It was observed in this study that older adults exhibited significantly lower CBG compared to younger adults from phases 2 to 4 (30 s to 420 s) during sit-to-stand and from phases 3 and 4 (180 s - 420 s) during lie-to-stand. Evidence demonstrates consistent results reporting that older adults had lower CBG compared to younger adults at the 5

th minute after lie-to-stand [

38], using a sequence method analysis [

39], and the Valsalva maneuver [

40].

In the present study, the observed decline in CBG among older adults during the later phases of both sit-to-stand and lie-to-stand transitions is primarily driven by age-related impairments in baroreceptor function, arterial compliance, and autonomic regulation [

14]. Age is associated with increased arterial stiffness, particularly in the carotid sinus and aortic arch, which reduces the mechanosensitivity of baroreceptors and impairs their ability to detect and respond to acute fluctuations in BP [

4]. This diminished mechanotransduction results in a blunted baroreflex response, as evidenced by Monahan et al. [

14] who demonstrated a strong positive relationship between carotid artery compliance and cardiovagal BRS. Additionally, age-related alterations in neural integration within the nucleus tractus solitarius and reduced vagal efferent responsiveness contribute to delayed and attenuated HR adjustments during postural stress [

7]. The findings by Lai et al., [

39] and Kim et al., [

41] further support this physiological mechanism, highlighting significantly lower BRS in older adults compared to younger individuals.

4.4. Symptoms of Orthostatic Intolerance

The comparison of OI symptoms between older adults and younger adults is limited in the literature, making direct age-group analyses challenging. As expected, older adults exhibited a higher prevalence of OI symptoms (14%) compared to younger adults (0%). Given the scarcity of direct comparisons, the discussion will focus on the physiological mechanisms underlying this difference. The higher OI symptoms indicate an age-related decline in cardiovascular-autonomic regulation. This disparity suggests that older adults have impairments in baroreflex sensitivity [

39], reduced parasympathetic modulation [

7], and diminished vascular response [

37], all of which contribute to compromised hemodynamic stability during postural transitions. The increased susceptibility to OI in older adults may reflect attenuated compensatory mechanisms, including delayed vasoconstriction and inadequate cardiac output adjustments [

4,

37], leading to transient cerebral hypoperfusion and symptomatic manifestations.

4.5. Implications for Older Adults’ Health and Clinical Practice

The findings of this study provide insight into age-related autonomic dysfunction and its relevance to older adults’ health. While the primary focus was on physiological mechanisms, the observed impairments, like reduced HRV, diminished CBG, increased parasympathetic modulation, and higher incidence of OI, have direct implications for clinical care and healthy aging. These alterations compromise the ability to regulate blood pressure during everyday postural transitions, such as rising from a bed or chair, increasing the risk of dizziness, falls, and death in older populations [

1,

42].

Our results showed the importance of incorporating beat-to-beat cardiovascular and autonomic assessments into routine geriatric evaluations. For example, using continuous non-invasive blood pressure monitoring during chair rise or tilt-table testing can help detect subtle impairments in compensatory responses that may not be captured with conventional intermittent measurements [

2,

43]. This approach is particularly relevant for older adults with multimorbidity, polypharmacy, or unexplained falls [

2], supporting fall risk, OH and OI management.

In clinical and rehabilitation settings, our data support the development of individualized interventions and strategies to reduce orthostatic stress (OH and OI). For example, teaching older adults to perform ankle pumps or leg crossing before standing can activate the muscle pump and help maintain venous return [

44,

45]. Advising them to pause briefly in a seated or semi-recumbent position before rising fully may allow time for autonomic responses to adjust. Adequate hydration (e.g., encouraging water intake of ~1.5-2 L/day) and the use of compression stockings in selected individuals are additional strategies to stabilize blood pressure [

42,

46].

Structured exercise programs targeting autonomic improvements, such as moderate-intensity walking, chair-based resistance exercises, or supervised balance training, can enhance baroreflex sensitivity and autonomic function [

47]. Follow-up assessments (e.g., re-testing CBG, CPM, HRV, after weeks of exercise) can help clinicians monitor progress and tailor interventions over time [

48,

49]. Similarly, medication reviews should focus on deprescribing or adjusting agents that blunt autonomic responses, such as certain antihypertensives (e.g., alpha-blockers or vasodilators), where appropriate [

50].

Finally, older adults' education is essential. Providing them with practical information on recognizing early symptoms of orthostatic intolerance (e.g., lightheadedness when rising, blurry vision, fatigue), along with guidance on when to seek medical attention, can empower proactive self-management [

2,

51]. Simple tools like symptom diaries or blood pressure logs may be used to monitor trends and inform healthcare decisions [

2,

42].

Translating physiological mechanistic findings into concrete clinical strategies, this research helps bridge the gap between physiological aging and applied geriatric care, supporting functional independence, safety, and quality of life in the growing population of older adults.

4.6. Limitations

Some limitations should be considered regarding this study. Although HRV was analyzed using both time- and frequency-domain, these analyses were conducted only at baseline, which may not fully observe the autonomic fluctuations occurring after active standing. The use of short-term or ultra-short HRV analyses may provide additional insights into the dynamic interplay between sympathetic and parasympathetic modulation in response to active standing orthostatic stress. Future studies may incorporate these approaches to offer a more detailed dynamic characterization of autonomic regulation after standing.

CBG was assessed at specific time points (30 s, 60 s, 180 s, and 420 s), which may not fully show the continuous dynamic fluctuations in baroreflex function throughout the active standing orthostatic stress. While this approach provides information on the short-term compensatory responses at critical times during active standing orthostatic stress, it may not account for transient variations or phase-dependent adaptations. Alternative methodologies, such as the sequence method [

27], which detects spontaneous changes in SBP and RR intervals to estimate baroreflex sensitivity in real-time, or transfer function analysis [

27], which evaluates baroreflex function across different frequency bands, may offer a more comprehensive representation of baroreflex regulation.

The use of convenience sampling may limit the generalizability of the findings to broaden older adult populations. Participants were primarily recruited through existing databases, local organizations, and community centers, which may have introduced sampling bias by favoring individuals who are more socially engaged or physically mobile. As a result, the sample may not fully represent socially isolated older adults, potentially underestimating the variability in autonomic responses to orthostatic stress within the general aging population. Future studies employing probabilistic sampling methods could help improve external validity and better capture the heterogeneity of responses across diverse subgroups of older adults.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, older adults exhibited greater autonomic dysfunction during active standing orthostatic stress, as evidenced by reduced HRV, impaired cardiac parasympathetic modulation (reflected by a higher HR 30:15 ratio), diminished CBG, and a higher incidence of OI symptoms. These findings indicate that older adults presented autonomic dysfunction, affecting the compensatory mechanisms, leading to a reduced ability to regulate BP and maintain cerebral perfusion during postural transitions. This impairment likely contributes to the higher incidence of OI symptoms in older adults (14%) compared to younger adults (0%), as the diminished autonomic response may result in delayed cardiovascular adjustments, increasing susceptibility to dizziness or lightheadedness on standing. Our findings contribute to a better understanding of older adults' short-term compensatory autonomic responses impairment and orthostatic intolerance with potential implications for fall risk prevention, geriatric care, and rehabilitation.

Author Contributions

DGM: Writing, review and editing, writing, original draft, formal analysis, data curation, visualization. JLS: review, editing, and data curation. FJA, ANS, RRO, SMC, and GGG: review and editing, visualization. TAD and RV: writing, review, editing, supervision, formal analysis, and conceptualization.

Funding

This research was supported in part by the Manitoba Medical Service Foundation (MMSF #2021-11), Centre on Aging Research Fellowship (University of Manitoba), University of Manitoba Retirees Association Scholarship, Center on Aging Betty Havens Memorial Graduate Fellowship, and Jack MacDonell Scholarship for Research in Aging).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval was granted by the University of Manitoba Health Research Ethics Board (approval number - HE2022-0058).

Data Availability: Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

ANS - Autonomic Nervous System

BP - Blood Pressure

BRS - Baroreflex Sensitivity

CBG - Cardiac Baroreflex Gain

CI - Confidence Interval

CO - Cardiac Output

CPM - Cardiac Parasympathetic Modulation

CSEP - Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology

DBP - Diastolic Blood Pressure

ECG - Electrocardiogram

ES - Effect Size

HF - High-Frequency Power

HR - Heart Rate

HRV - Heart Rate Variability

IQR - Interquartile Range

LF - Low-Frequency Power

LF/HF - Low-Frequency to High-Frequency Ratio

MAP - Mean Arterial Pressure

OA - Older Adults

OI - Orthostatic Intolerance

OH - Orthostatic Hypotension

RMSSD - Root Mean Square of Successive Differences

RR - R-R Interval (Interval between Heartbeats)

SBP - Systolic Blood Pressure

SAGER - Sex and Gender Equity in Research

SD - Standard Deviation

SDRR - Standard Deviation of RR Intervals

STROBE - Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology

YA - Younger Adults

References

- Ricci, F.; De Caterina, R.; Fedorowski, A. Orthostatic Hypotension: Epidemiology, Prognosis, and Treatment. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015, 66, 848–860. [CrossRef]

- Fedorowski, A.; Ricci, F.; Hamrefors, V.; Sandau, K.E.; Hwan Chung, T.; Muldowney, J.A.S.; Gopinathannair, R.; Olshansky, B. Orthostatic Hypotension: Management of a Complex, But Common, Medical Problem. Circ. Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. 2022, 15, E010573. [CrossRef]

- Finucane, C.; van Wijnen, V.K.; Fan, C.W.; Soraghan, C.; Byrne, L.; Westerhof, B.E.; Freeman, R.; Fedorowski, A.; Harms, M.P.M.; Wieling, W.; et al. A Practical Guide to Active Stand Testing and Analysis Using Continuous Beat-to-Beat Non-Invasive Blood Pressure Monitoring. Clin. Auton. Res. 2019, 29, 427–441. [CrossRef]

- Wehrwein, E.A.; Joyner, M.J. Regulation of Blood Pressure by the Arterial Baroreflex and Autonomic Nervous System. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2013, 117, 89–102. [CrossRef]

- Wieling, W.; Karemaker, J.M. Measurement of Heart Rate and Blood Pressure to Evaluate Disturbances in Neurocardiovascular Control. Auton. Fail. 2013, 290–306. [CrossRef]

- David E. Mohrman; Lois Jane Hellet Cardiovascular Physiology; 8th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, 2010; ISBN 978-0-07-179312-4.

- Christopher J. Mathias and Roger Bannister Autonomic Failure: A Textbook of Clinical Disorders of the Autonomic Nervous System; 5th ed.; Oxford University Press, 2013; ISBN 9788578110796.

- Billman, G.E. Heart Rate Variability - A Historical Perspective. Front. Physiol. 2011, 2 NOV, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Jandackova, V.K.; Scholes, S.; Britton, A.; Steptoe, A. Are Changes in Heart Rate Variability in Middle-Aged and Older People Normative or Caused by Pathological Conditions? Findings from a Large Population-Based Longitudinal Cohort Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2016, 5, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Parvaneh, S.; Howe, C.L.; Toosizadeh, N.; Honarvar, B.; Slepian, M.J.; Fain, M.; Mohler, J.; Najafi, B. Regulation of Cardiac Autonomic Nervous System Control across Frailty Statuses: A Systematic Review. Gerontology 2015, 62, 3–15. [CrossRef]

- Reardon, M.; Malik, M. Changes in Heart Rate Variability with Age. PACE - Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 1996, 19, 1863–1866. [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, D.T.; Ivanov, P.C. Fractal Scale-Invariant and Nonlinear Properties of Cardiac Dynamics Remain Stable with Advanced Age: A New Mechanistic Picture of Cardiac Control in Healthy Elderly. Am. J. Physiol. - Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2007, 293, 1–54. [CrossRef]

- Ewing, A.D.J.; Campbell, I.W.; Murray, A.; Neilson, J.M.M.; Clarke, B.F. Diabetes Immediate Autonomic Neuropathy In. 1978, 1, 145–147.

- Monahan, K.D. Effect of Aging on Baroreflex Function in Humans. Am. J. Physiol. - Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2007, 293. [CrossRef]

- Mol, A.; Maier, A.B.; van Wezel, R.J.A.; Meskers, C.G.M. Multimodal Monitoring of Cardiovascular Responses to Postural Changes. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Borst, C.; Van Brederode, J.F.M.; Wieling, W. Mechanisms of Initial Blood Pressure Response to Postural Change. Clin. Sci. 1984, 67, 321–327. [CrossRef]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for Reporting Observational Studies. Int. J. Surg. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Heidari, S.; Babor, T.F.; De Castro, P.; Tort, S.; Curno, M. Sex and Gender Equity in Research: Rationale for the SAGER Guidelines and Recommended Use. Res. Integr. Peer Rev. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines for Older Adults 65 Years and Older; CSEP, Ed.; Ottawa, 2011;

- Guelen, I.; Westerhof, B.E.; Van Der Sar, G.L.; Van Montfrans, G.A.; Kiemeneij, F.; Wesseling, K.H.; Bos, W.J.W. Finometer, Finger Pressure Measurements with the Possibility to Reconstruct Brachial Pressure. Blood Press. Monit. 2003, 8, 27–30. [CrossRef]

- Van Der Velde, N.; Van Den Meiracker, A.H.; Stricker, B.H.C.; Van Der Cammen, T.J.M. Measuring Orthostatic Hypotension with the Finometer Device: Is a Blood Pressure Drop of One Heartbeat Clinically Relevant? Blood Press. Monit. 2007, 12, 167–171. [CrossRef]

- Mol, A.; Slangen, L.R.N.; Trappenburg, M.C.; Reijnierse, E.M.; van Wezel, R.J.A.; Meskers, C.G.M.; Maier, A.B. Blood Pressure Drop Rate after Standing up Is Associated with Frailty and Number of Falls in Geriatric Outpatients. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9. [CrossRef]

- Malik, M.; Camm, A.J.; Bigger, J.T.; Breithardt, G.; Cerutti, S.; Cohen, R.J.; Coumel, P.; Fallen, E.L.; Kennedy, H.L.; Kleiger, R.E.; et al. Heart Rate Variability. Standards of Measurement, Physiological Interpretation, and Clinical Use. Eur. Heart J. 1996, 17, 354–381. [CrossRef]

- Balcıoğlu, A.S. Diabetes and Cardiac Autonomic Neuropathy: Clinical Manifestations, Cardiovascular Consequences, Diagnosis and Treatment. World J. Diabetes 2015, 6, 80. [CrossRef]

- Duque, A.; Mediano, M.F.F.; De Lorenzo, A.; Rodrigues Jr, L.F. Cardiovascular Autonomic Neuropathy in Diabetes: Pathophysiology, Clinical Assessment and Implications. World J. Diabetes 2021, 12, 855–867. [CrossRef]

- Norcliffe-Kaufmann, L.; Kaufmann, H.; Palma, J.A.; Shibao, C.A.; Biaggioni, I.; Peltier, A.C.; Singer, W.; Low, P.A.; Goldstein, D.S.; Gibbons, C.H.; et al. Orthostatic Heart Rate Changes in Patients with Autonomic Failure Caused by Neurodegenerative Synucleinopathies. Ann. Neurol. 2018, 83, 522–531. [CrossRef]

- La Rovere, M.T.; Pinna, G.D.; Raczak, G. Baroreflex Sensitivity: Measurement and Clinical Implications. Ann. Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2008, 13, 191–207. [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A Flexible Statistical Power Analysis Program for the Social, Behavioral, and Biomedical Sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [CrossRef]

- Yoav Benjamini and Yosef Hochberg Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. 1995, 57, 289–300.

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 1992, 1, 98–101. [CrossRef]

- Kerby, D.S. The Simple Difference Formula: An Approach to Teaching Nonparametric Correlation. Compr. Psychol. 2014, 3, 11.IT.3.1. [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.; Wieling, W.; Axelrod, F.B.; Benditt, D.G.; Benarroch, E.; Biaggioni, I.; Cheshire, W.P.; Chelimsky, T.; Cortelli, P.; Gibbons, C.H.; et al. Consensus Statement on the Definition of Orthostatic Hypotension, Neurally Mediated Syncope and the Postural Tachycardia Syndrome. Auton. Neurosci. Basic Clin. 2011, 161, 46–48. [CrossRef]

- Kawaguchi, T.; Uyama, O.; Konishi, M.; Nishiyama, T.; Iida, T. Orthostatic Hypotension in Elderly Persons during Passive Standing: A Comparison with Young Persons. Journals Gerontol. - Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2001, 56, 273–280. [CrossRef]

- Grässler, B.; Dordevic, M.; Darius, S.; Vogelmann, L.; Herold, F.; Langhans, C.; Halfpaap, N.; Böckelmann, I.; Müller, N.G.; Hökelmann, A. Age-Related Differences in Cardiac Autonomic Control at Resting State and in Response to Mental Stress. Diagnostics 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- Droguett, V.S.L.; Santos, A.D.C.; de Medeiros, C.E.; Marques, D.P.; do Nascimento, L.S.; Brasileiro-Santos, M.D.S. Cardiac Autonomic Modulation in Healthy Elderly after Different Intensities of Dynamic Exercise. Clin. Interv. Aging 2015, 10, 203–208. [CrossRef]

- Acharya, U.R.; Joseph, K.P.; Kannathal, N.; Lim, C.M.; Suri, J.S. Heart Rate Variability: A Review. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 2006, 44, 1031–1051. [CrossRef]

- Mohrman;, D.L.H. Cardiovascular Physiology; 8th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education, 2013; ISBN 0071793119.

- Kim, Y.S.; Bogert, L.W.J.; Immink, R. V.; Harms, M.P.M.; Colier, W.N.J.M.; Van Lieshout, J.J. Effects of Aging on the Cerebrovascular Orthostatic Response. Neurobiol. Aging 2011, 32, 344–353. [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.H.; Yuan, Y.; Liang, Y.X.; Yu, J.H. Comparison of Aging Effect between Cardiac Complexity and Baroreceptor Sensitivity. Proc. - 2021 Int. Conf. Inf. Technol. Biomed. Eng. ICITBE 2021 2021, 287–291. [CrossRef]

- Monahan, K.D.; Dinenno, F.A.; Seals, D.R.; Clevenger, C.M.; Desouza, C.A.; Tanaka, H. Age-Associated Changes in Cardiovagal Baroreflex Sensitivity Are Related to Central Arterial Compliance. Am. J. Physiol. - Hear. Circ. Physiol. 2001, 281, 284–289. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.S.; Bogert, L.W.J.; Immink, R. V.; Harms, M.P.M.; Colier, W.N.J.M.; Van Lieshout, J.J. Effects of Aging on the Cerebrovascular Orthostatic Response. Neurobiol. Aging 2011, 32, 344–353. [CrossRef]

- Dani, M.; Dirksen, A.; Taraborrelli, P.; Panagopolous, D.; Torocastro, M.; Sutton, R.; Lim, P.B. Orthostatic Hypotension in Older People: Considerations, Diagnosis and Management. Clin. Med. J. R. Coll. Physicians London 2021, 21, E275–E282. [CrossRef]

- Liguori, I.; Russo, G.; Coscia, V.; Aran, L.; Bulli, G.; Curcio, F.; Della-Morte, D.; Gargiulo, G.; Testa, G.; Cacciatore, F.; et al. Orthostatic Hypotension in the Elderly: A Marker of Clinical Frailty? J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2018, 19, 779–785. [CrossRef]

- Krediet, C.T.P.; Van Lieshout, J.J.; Bogert, L.W.J.; Immink, R. V.; Kim, Y.S.; Wieling, W. Leg Crossing Improves Orthostatic Tolerance in Healthy Subjects: A Placebo-Controlled Crossover Study. Am. J. Physiol. - Hear. Circ. Physiol. 2006, 291, 1768–1772. [CrossRef]

- Ten Harkel, A.D.J.; Van Lieshout, J.J.; Wieling, W. Effects of Leg Muscle Pumping and Tensing on Orthostatic Arterial Pressure: A Study in Normal Subjects and Patients with Autonomic Failure. Clin. Sci. 1994, 87, 553–558. [CrossRef]

- Logan, A.; Freeman, J.; Pooler, J.; Kent, B.; Gunn, H.; Billings, S.; Cork, E.; Marsden, J. Effectiveness of Non-Pharmacological Interventions to Treat Orthostatic Hypotension in Elderly People and People with a Neurological Condition: A Systematic Review. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2556–2617. [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.; Levine, B.D. Exercise and the Autonomic Nervous System. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2013, 117, 147–160. [CrossRef]

- Fecchio, R.Y.; de Sousa, J.C.S.; Oliveira-Silva, L.; da Silva Junior, N.D.; Pio-Abreu, A.; da Silva, G. V.; Drager, L.F.; Low, D.A.; Forjaz, C.L.M. Effects of Dynamic, Isometric and Combined Resistance Training on Blood Pressure and Its Mechanisms in Hypertensive Men. Hypertens. Res. 2023, 46, 1031–1043. [CrossRef]

- Bellavere, F.; Cacciatori, V.; Bacchi, E.; Gemma, M.L.; Raimondo, D.; Negri, C.; Thomaseth, K.; Muggeo, M.; Bonora, E.; Moghetti, P. Effects of Aerobic or Resistance Exercise Training on Cardiovascular Autonomic Function of Subjects with Type 2 Diabetes: A Pilot Study. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2018, 28, 226–233. [CrossRef]

- Wahba, A.; Shibao, C.A.; Muldowney, J.A.S.; Peltier, A.; Habermann, R.; Biaggioni, I. Management of Orthostatic Hypotension in the Hospitalized Patient: A Narrative Review. Am. J. Med. 2022, 135, 24–31. [CrossRef]

- Fedorowski, A.; Melander, O. Syndromes of Orthostatic Intolerance: A Hidden Danger. J. Intern. Med. 2013, 273, 322–335. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).