1. Introduction

The stress induced by performing daily activities, such as getting up from bed or a chair, presents significant physiological challenges due to the abrupt gravitational shift in blood distribution. These challenges demand rapid, coordinated, and integrated dynamic adaptive cardiovascular responses to maintain cerebral blood perfusion and flow [

1]. On standing, blood pressure (BP) transiently drops, and cerebral blood flow decreases, requiring immediate compensatory adjustments to stabilize hemodynamic responses [

1]. Effective dynamic control and regulation of the cardiovascular system is necessary for maintaining homeostasis and functionality when facing these external challenges [

2]. Failure to properly regulate these responses can result in homeostatic dysregulation [

3], common with advancing age. As we get older, the efficiency of these compensatory responses diminishes, often resulting in impaired BP control and regulation as well as reduced cerebral perfusion [

4]. One common manifestation of this dysregulation is orthostatic hypotension (OH).

While previous studies have described key physiological impairments related to OH [

5,

6,

7], much of the research has relied on single time-point measurements or narrow time windows [

8,

9,

10]. These approaches fail to capture the dynamic and time-sensitive nature of cardiovascular compensation that unfolds across several minutes following orthostatic stress. To address this limitation, the current study analyzes cardiovascular responses in a phase-specific manner, capturing the temporal profile of compensatory mechanisms from the initial seconds to several minutes after standing. This phase-specific approach was developed based on time intervals to capture key phases of cardiovascular regulation following active standing.

Another critical but unexplored aspect of postural regulation in older adults is the coordination or matching between cardiac output (CO) and systemic vascular resistance (SVR) after active standing orthostatic stress [

1]. In young adults, this CO-SVR matching occurs within the first seconds after standing, with a proportional increase in CO and decrease in SVR, leading to BP recovery through these compensatory responses [

1], but these data are lacking in older adults, who are at higher risk of OH.

This study aimed to describe and compare short-term cardiovascular compensatory responses between younger adults (18-30 years) and older adults (60-79 years) during sit-to-stand (lower orthostatic stress) and lie-to-stand (higher orthostatic stress). It was hypothesized that: 1) older adults will show reduced and delayed responses in SBP, DBP, MAP, SVR, HR, and CO responses, particularly during early phases after standing. 2) SV values will be higher in older adults across all phases, reflecting compensatory reliance on SV due to attenuated HR response. 3) CO-SVR matching will be delayed in older adults.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design

This is an observational cross-sectional study that used the Strengthening Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) [

11] as a reporting guideline.

Settings

This study was conducted at the Applied Research Centre, Faculty of Kinesiology and Recreation Management, University of Manitoba, from August 2022 until August 2023. The study received approval from the University of Manitoba Health Research Ethics Board (approval number - HE2022-0058).

Participants

Participants were recruited using a convenience sampling strategy from Dr. Todd Duhamel's database (University of Manitoba), which contains ~1000 females who volunteered in the Women's Advanced Risk-assessment in Manitoba (WARM) Hearts study; the Centre on Aging database (University of Manitoba); visits to Men's Shed (community hubs where males gather to share skills, learn, and support each other in a welcoming environment); and retirement/care homes located in Winnipeg, Canada. Phone calls, emails, social media platforms (Facebook, Instagram, X), ads, flyers, and posters were also used as recruitment strategies, particularly for younger adults. People interested in participating contacted researchers by email or phone.

Eligibility was determined using a customized screening questionnaire designed by our research laboratory. Participants were included in the study if they were younger (18-30 yrs) or older (60-79 yrs) adults and identified their sex at birth as female or male. Participants were excluded if they had a history of ischemic heart disease, acute myocardial infarction, stroke, percutaneous coronary intervention, coronary artery bypass surgery, congestive heart failure, psychiatric disorders, severe cognitive impairment, or pregnancy. Common age-related conditions, such as hypertension, were not exclusionary and are reported in the results section.

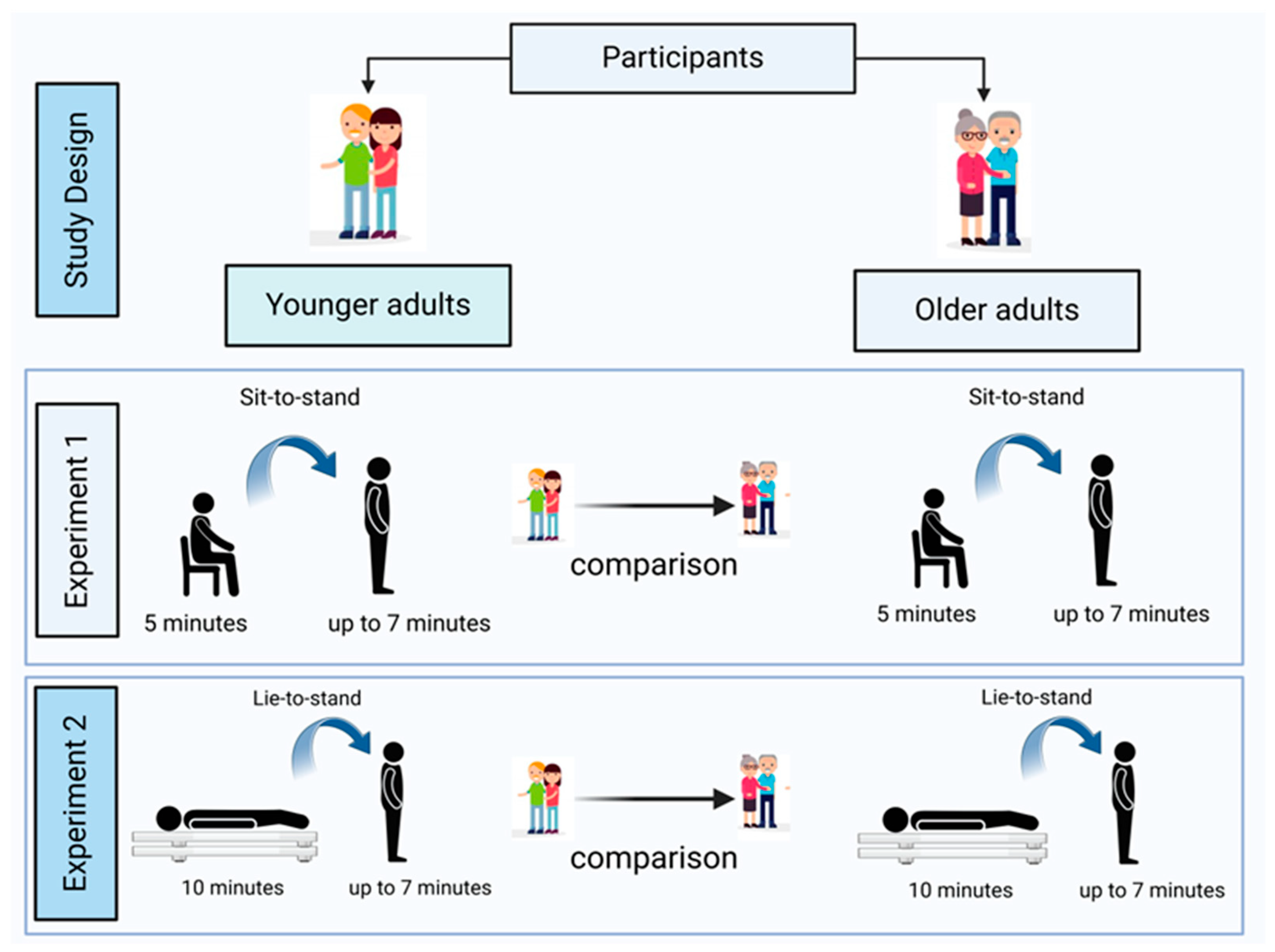

All participants completed both the sit-to-stand (Experiment 1) and lie-to-stand (Experiment 2) orthostatic stress challenges in a randomized and counterbalanced order (

Figure 1). Variables regarding baseline, immediate responses on standing, dynamic short-term cardiovascular compensatory responses, and CO-SVR matching were compared between younger adults and older adults in Experiments 1 and 2. Participants received pre-instructions 48 hours before the lab visit. On the day of this visit, they read and signed an informed consent form after having all their questions and/or concerns addressed by the researchers.

Data Collection

Prior to testing, measurements of resting HR and BP were taken by a trained researcher to ensure participants’ safety, following the procedures adopted by the Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology (CSEP) guidelines [

12]. After consent and familiarization, participants underwent active standing orthostatic stress challenges with non-invasive beat-by-beat BP monitoring (Finometer

TM Pro Device, Finapres Medical System BV, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). The study was performed in a quiet room with a temperature of 22.0 ± 1.0°C and humidity and barometric pressure at ambient between 8:30 and 11:30 am on weekdays to minimize circadian cycle influence.

Demographic and Anthropometric Measurements

Demographic (sex assigned at birth, age, and date of birth), anthropometric, and body composition measurements were collected to characterize the sample. Measurements included body mass (kg) and height (m) assessed using an InBody© 270 device (InBody CO., Ltd, Cerritos, CA, USA) and a SECA mobile stadiometer (SECA, Frankfurt, Germany), respectively. Medication used was recorded through participants’ self-reports but was not controlled, and more details were provided in the results section. None of the participants reported being on hormone replacement therapy.

Assessment of Cardiovascular Responses

HR was recorded continuously on a beat-by-beat basis using a 3-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) module (Finapres Medical System, Arnhem, The Netherlands) at a sampling frequency of 1 kHz, with HR derived from R-R intervals. Continuous non-invasive beat-by-beat measurements of SBP, DBP, and MAP were obtained from the arterial pressure signal (photoplethysmography) at the middle finger of the left hand (Finometer, Finapres Medical System, Arnhem, The Netherlands) [

13]. The device was calibrated (return-to-flow method), finger circumference was measured to ensure the correct cuff size, and a height correction system was adjusted for hand position relative to heart level. SV was estimated using the Modelflow algorithm (Finometer, Finapres Medical System, Arnhem, The Netherlands) [

14]. CO was derived by HR and SV (CO = SV x HR), and systemic vascular resistance (SVR) was derived by dividing MAP by CO (SVR = MAP/CO).

Sample Size

The sample size was determined a priori using the G*Power software (Heinrich Heine University, Dusseldorf, Germany)[

15], based on data from an internal pilot study, involving 16 participants (8/group). The power analysis was conducted using a t-test for the difference between two independent group means (younger adults vs older adults) obtained from the amplitude of the overshoot or undershoot measured within 30 seconds after the nadir. The analysis used an α level of 0.05 and demonstrated an actual power of 0.80 with an effect size of 0.69, derived from the mean ± SD values for younger adults (6.83 ± 6.96 mmHg) and older adults (2.36 ± 5.93 mmHg), resulting in an estimated total sample of 54 participants (27/group). A larger sample of older adults was intentionally collected to account for the increased likelihood of data loss in this population due to signal artifacts and noise, particularly during dynamic postural tasks. Oversampling was used to ensure that adequate statistical power and to retain sufficient data for the planned analyses.

Data Analysis

Data from the Finometer were acquired and processed on a beat-by-beat basis using LabChart 8.0 (ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, CO, USA). ECG data were filtered with a 5-30 Hz bandpass to detect R peaks, except for the 30 seconds before and 90 seconds after standing, during which the raw signal was preserved, and Finometer calibration was manually disabled. When ECG traces were of poor quality, analysis was performed on the pressure waveform peaks. BP was calibrated using standard procedures described by the company, followed by a manual calibration (automated BP monitor - ARSIMAI, BSX516, Munster, Germany). Data was saved and transferred to a custom Matlab app for further analyses (Matlab R2024; The MathWorks Inc, Natick, MA, USA). In the Matlab app, noise and motion artifacts were removed using a median filter followed by a low-pass filter (cut-off = 0.05 rad/sample based on scalogram analysis) and a 5-second moving average to smooth the signal and extract parameters of interest [

16,

17]. Then, the data was interpolated and corrected for delays introduced by resampling at 1 Hz.

Variables Extracted and Analyzed During Active Standing

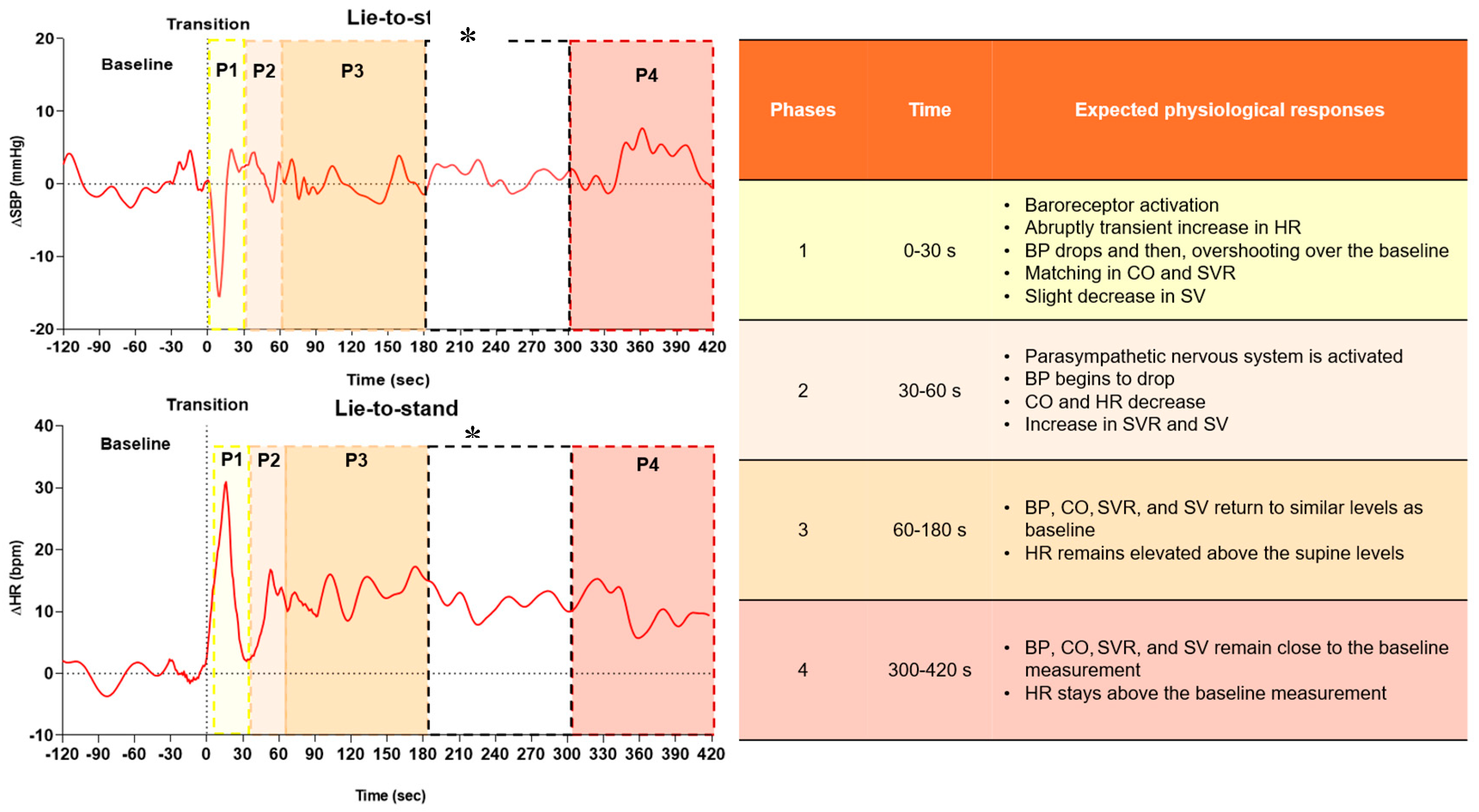

Baseline values were determined as the average of the 2 minutes before standing. In the first 30 seconds after standing, the lowest values of SBP, DBP, MAP, and SVR, and the highest values of HR, CO, and SV were analyzed. Peak values were defined as the highest value reached within 30 seconds following standing. Short-term cardiovascular compensatory responses were defined as the highest point reached after the drop. These responses were divided into four specific phases, as follows: phase 1 (0-30 s), phase 2 (30-60 s), phase 3 (60-180 s), and phase 4 (300-420 s), reflecting cardiovascular regulation after active standing orthostatic stress. This phased approach is based on expected physiological responses in healthy adults (reference response) and specific times regarding OH classifications (initial orthostatic hypotension, classical orthostatic hypotension, delayed orthostatic hypotension) [

18]. Such an approach enables a detailed assessment of adaptive responses and differences in cardiovascular regulation between older adults and young adults (

Figure 2).

Statistical Analysis

The normality of the data was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Continuous variables (e.g., SBP, DBP) with a parametric distribution were reported as mean ± SD, along with the 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Non-parametric continuous variables were reported as median with interquartile range (IQR) and minimum and maximum values. For sample characterization, continuous data (e.g., height, body mass) were presented as mean ± SD, 95% CI, minimum, and maximum values, while categorical data (e.g., sex, educational level) were reported as absolute numbers and relative percentages. The Chi-square test was used to compare categorical variables.

For comparison data between groups (younger vs. older), the Mann-Whitney U test was applied. To adjust for multiple hypothesis testing, the p-values were corrected using the Benjamini-Hochberg adjustment [

21], with the false discovery rate (FDR) set at 0.05. Significant results were reported based on the corrected p-values.

For continuous variables, effect sizes were calculated to quantify the magnitude of between-group differences. For parametric data, Cohen’s d was used [

22]; for non-parametric data [

23] the correlation coefficient r was applied. Effect size was classified as low (≤ 0.05), medium (0.06-0.25), high (0.26-0.50), and very high (> 0.50) [

22]. Correlations between CO and SVR at 0-30 s (phase 1), 30-60 s (phase 2), 60-180 s (phase 3), and 300-420 s (phase 4) were analyzed using Pearson or Spearman correlation, depending on the data distribution. Correlation magnitudes were interpreted as small (r = 0.10-0.29), medium (r = 0.30-0.49), and large (r ≥ 0.50) [

22]. All analyses were conducted using R

® (Version 4.1.1, Vienna, Austria), with statistical significance set at α < 0.05.

3. Results

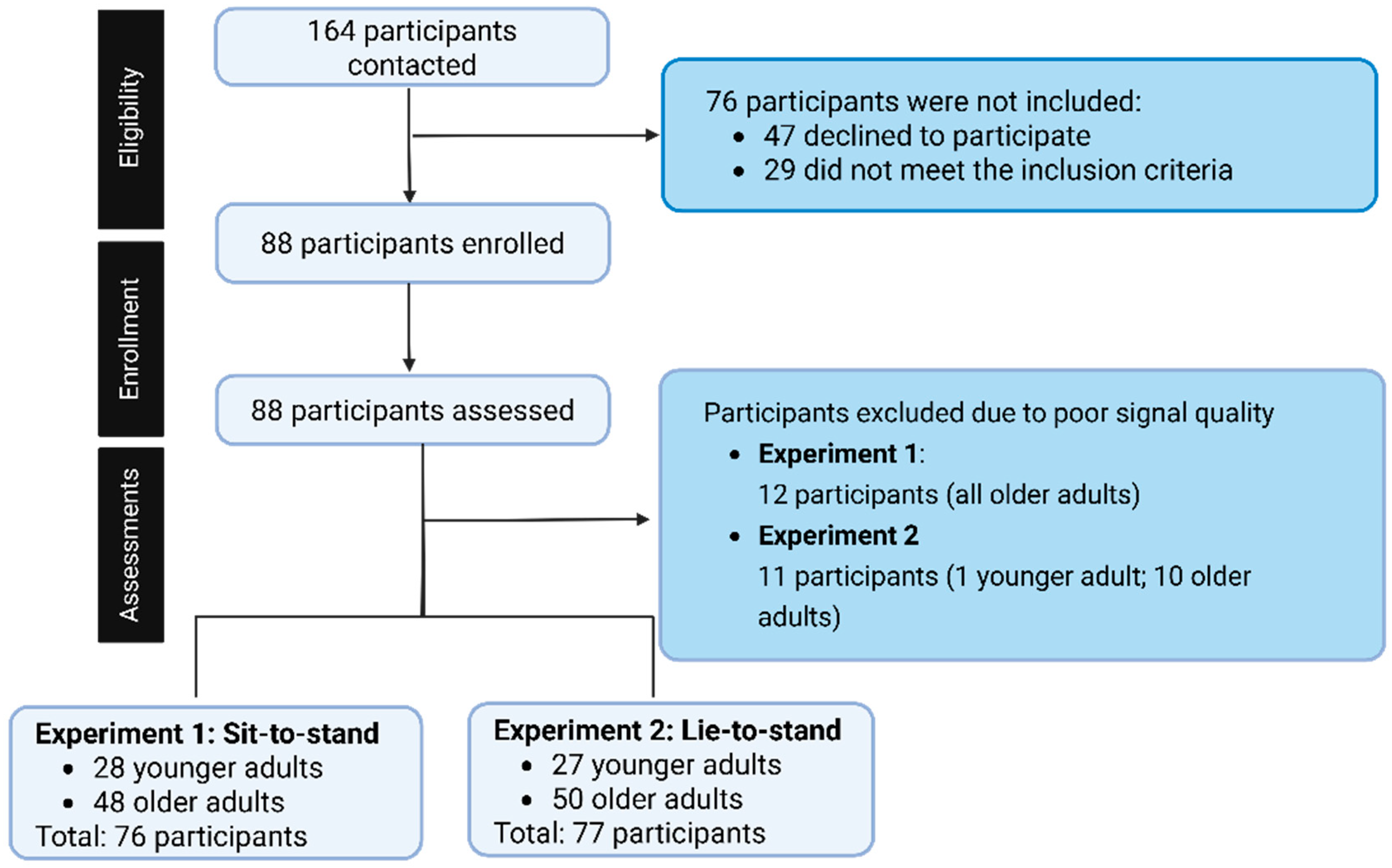

In the sit-to-stand transition, data from 12 participants were excluded from the analysis, where a final sample size was 28 younger adults and 48 older adults. In the lie-to-stand, 11 participants were excluded from the analysis, resulting in a final sample size of 27 younger adults and 50 older adults (

Figure 3). Data was excluded due to poor signal quality (e.g., noisy, motion artifacts).

In terms of sex distribution, 70% of the older adults were female and 30% were older males, while the younger adults sample consisted of 50% females and 50% males. Anthropometric data showed that older adults had a higher BMI and were shorter than younger adults, but there were no statistically significant differences in body mass. Regarding older adults’ cardiovascular medication, 27% of participants were on calcium channel blockers (n = 14), 13% on beta-blockers (n = 7), 10% on diuretics (n = 5), 8% on ACE inhibitors (n = 4), and 8% on angiotensin receptor blockers (n = 4). Also, only 2 of the younger adults (7%) were on psychotropic medications.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics of younger adults and older adults.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics of younger adults and older adults.

| Experiment 1 (sit-to-stand) |

| Variable |

Younger adults |

|

Older adults |

|

p |

| Sex |

n |

% |

|

n |

% |

|

|

| Female |

14 |

50 |

---- |

34 |

70↑ |

---- |

<0.001* |

| Male |

14 |

50↑ |

---- |

14 |

30 |

---- |

<0.001* |

| Experiment 2 (lie-to-stand) |

| Variable |

Younger adults |

|

Older adults |

|

p |

| Sex |

n |

% |

|

n |

% |

|

|

| Female |

13 |

48↑ |

---- |

35 |

70↑ |

---- |

<0.001* |

| Male |

14 |

52↑ |

---- |

15 |

30 |

---- |

<0.001* |

| Anthropometric data |

Mean ± SD |

CI 95% |

Min; Max |

Mean ± |

CI 95% |

Min; Max |

|

| Age (years) |

21.0 ± 2.3 |

20.8; 22.6 |

18.0; 28.0 |

70.5 ± 3.9↑ |

69.3; 71.5 |

63.0; 78.0 |

<0.001* |

| Height (m) |

1.73 ± 0.07 |

1.69; 1.76 |

1.56; 1.86 |

1.64 ± 0.08↓ |

1.62; 1.66 |

1.46; 1.84 |

<0.001* |

| Body mass |

67.6 ± 11.9 |

62.9-72.2 |

42.6; 90.5 |

73.7 ± 15.4 |

69.4; 78.0 |

42.5; 110.0 |

0.07 |

| BMI (kg/m2) |

22.6 ± 3.38 |

21.3-23.9 |

16.5; 30.4 |

27.3 ± 5.6↑ |

25.8; 28.9 |

17.1; 48.4 |

<0.001* |

| Hypertension |

n |

% |

---- |

n |

% |

---- |

---- |

| |

0 |

0 |

|

20 |

40 |

|

<0.001* |

| Diabetes |

n |

% |

---- |

n |

% |

---- |

|

| |

0 |

0 |

|

2 |

4 |

|

0.53 |

| Medications |

n |

% |

---- |

n |

% |

---- |

|

| Cardiovascular Medications |

0 |

0 |

---- |

20 |

40 |

---- |

<0.001* |

| Psychotropic Medications |

2 |

7 |

--- |

7 |

14 |

---- |

0.47 |

Sit to Stand Responses

During sit-to-stand, at baseline, older adults exhibited higher SBP, DBP, MAP, and SVR, while HR, CO, and SV were lower compared to younger adults. Immediately on sit-to-stand, older adults experienced a greater drop in SBP, DBP, MAP, SVR, lower HR and CO peaks, and larger SV peak values compared to younger adults. Additionally, SBP, DBP, and MAP short-term cardiovascular compensatory responses showed no statistically significant differences between older adults and younger adults during phases 1 (0-30 s) and 2 (30-60 s). However, older adults exhibited higher values in phases 3 (60-180 s) and 4 (300-420 s), except for DBP. Older adults also had lower SVR values in phases 1 and 2, but no differences in phases 3 and 4. In older adults, HR had lower values and SV had higher values across all phases compared to younger adults. CO values were lower in phases 1 and 4, but no differences were observed in phases 2 and 3 (

Table 2).

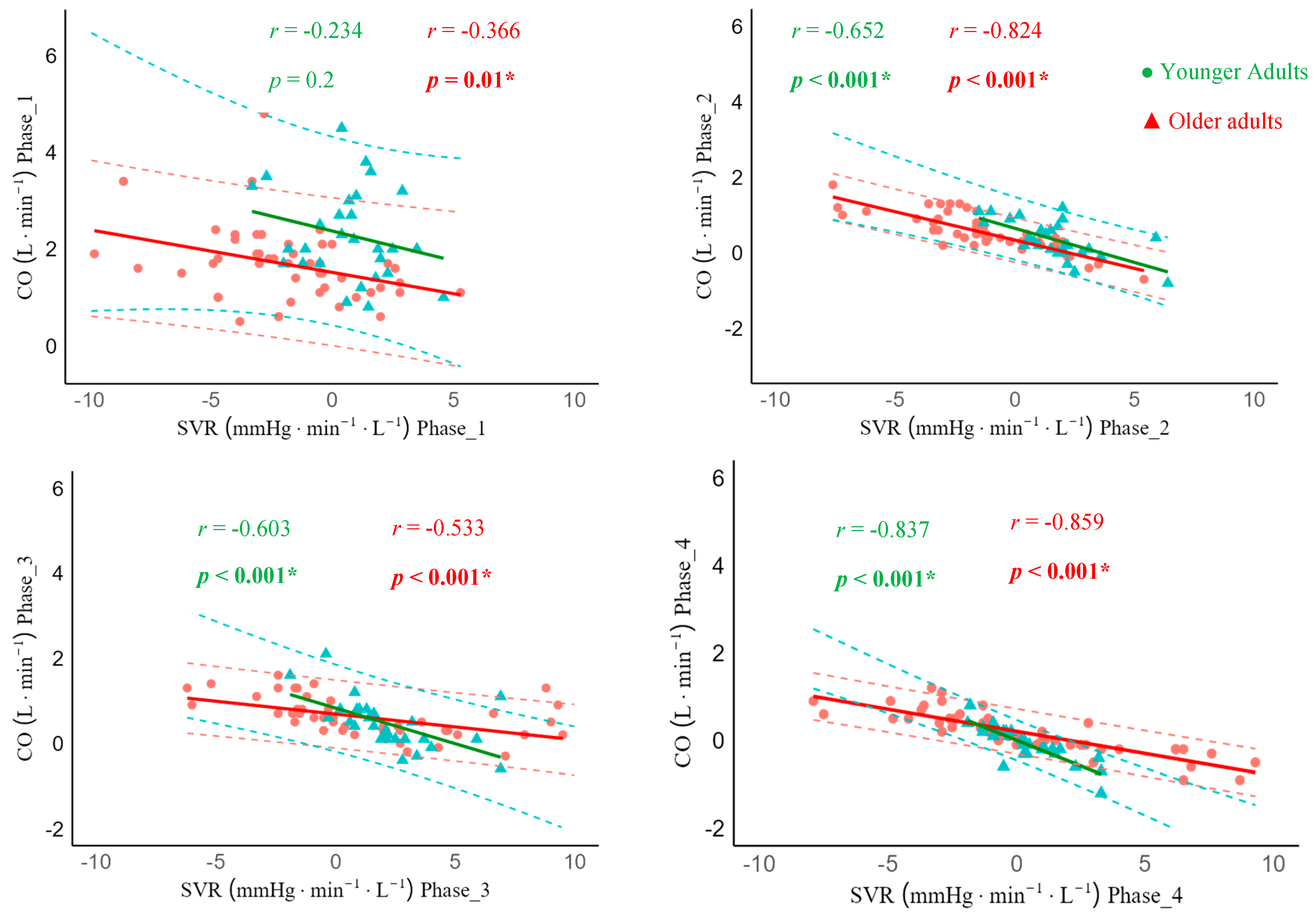

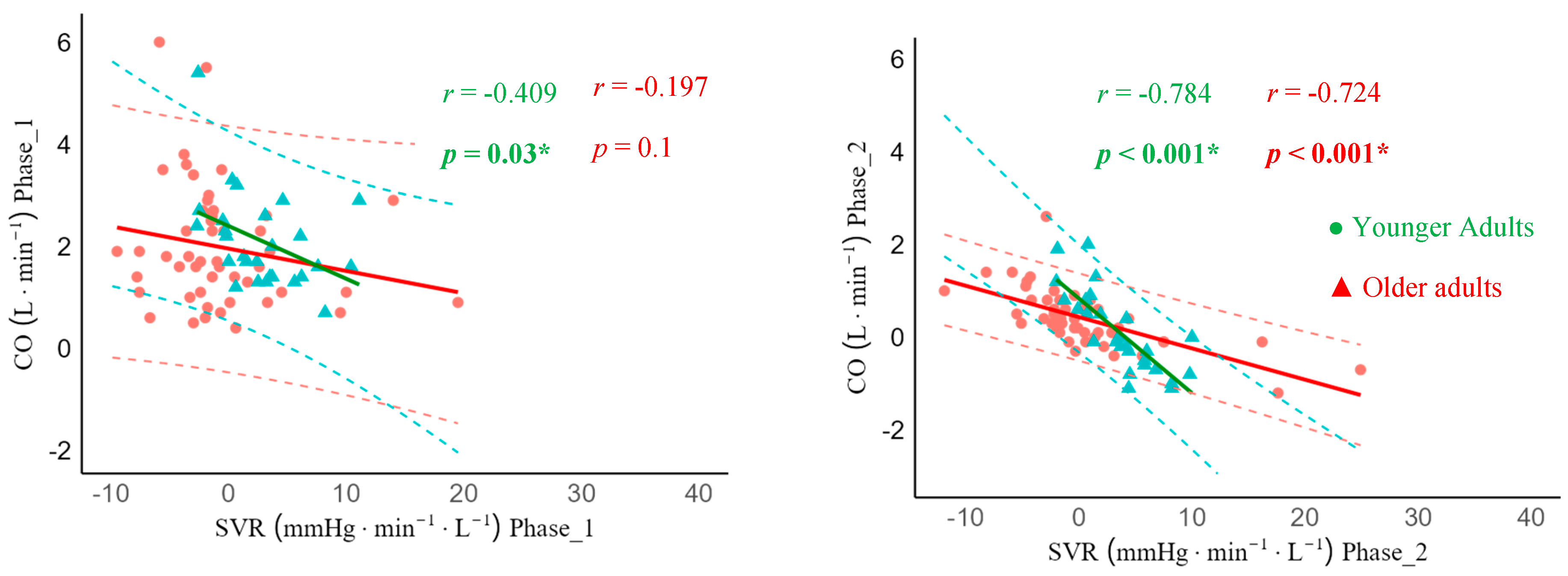

Regarding ΔCO-ΔSVR matching, in sit-to-stand, younger adults demonstrated a non-significant correlation in phase 1 (r = -0.234, 95% CI -0.569; 0.137, p = 0.2). However, a significant strong negative correlation was observed from phases 2-4 (phase 2: r = -0.652, 95% CI -0.825; -0.369, p < 0.001, phase 3: r = -0.603, 95% CI -0.797; -0.296, p < 0.001), and phase 4: r = -0.837, 95% CI -0.922; -0.674, p < 0.001). Older adults showed moderate and strong significant negative correlations between ΔCO and ΔSVR in all phases (phase 1: r = -0.366, 95% CI -0.534; -0.011, p = 0.01, phase 2: r = -0.824, 95% CI -0.898; -0.704, p < 0.001), phase 3: r = -0.533, 95% CI -0.710; -0.293, p < 0.001), and phase 4: r = -0.859, 95% CI -0.919; -0.761, p < 0.001) (

Figure 4).

Lie to Stand Responses

During lie-to-stand, older adults exhibited higher SBP, DBP, MAP, and SVR, while CO and SV were lower compared to younger adults, with no differences in HR. Older adults experienced a greater drop in SBP, DBP, MAP, and SVR, lower HR peak, higher SV peak, and no differences in CO peak values (

Table 3). Furthermore, older adults’ SBP, DBP, MAP, and SVR short-term compensatory responses were lower in phases 1 and 2, but similar in phases 3 and 4 than younger adults. However, HR values were lower, and SV values were higher in phases 1-3 but not in phase 4 in older adults. No statistically significant differences were observed in CO across all phases between older adults and younger adults (

Table 3).

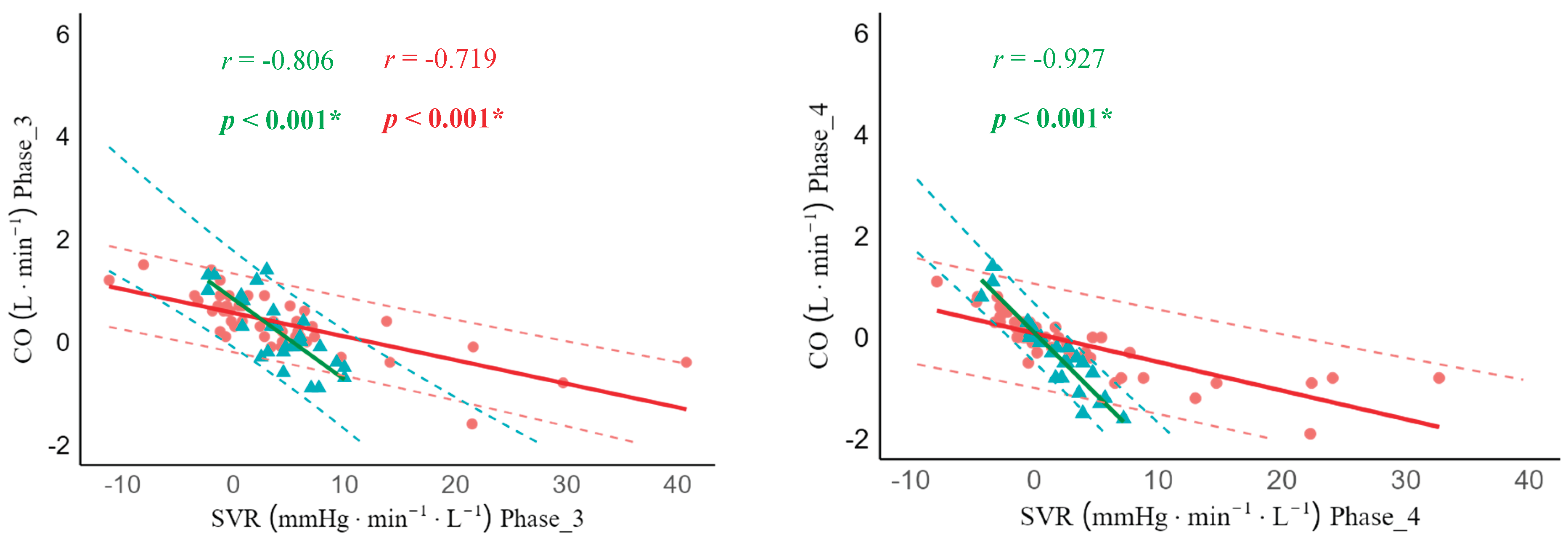

In lie-to-stand, there was moderate and strong significant negative correlations between ΔCO and ΔSVR across all phases in younger adults (phase 1: r = -0.409, 95% CI -0.683; -0.034, p = 0.03), phase 2: r = -0.784, 95% CI -0.897; -0.575, p < 0.001), phase 3: r = -0.806, 95% CI -0.908; -0.614, p < 0.001), and phase 4: r = -0.927,95% CI -0.966; -0.844, p < 0.001). Unlike younger adults, the ΔCO and ΔSVR correlation was not statistically significantly different in older adults in phase 1 (r = -0.197, 95% CI -0.430; 0.118, p = 0.1), but strong statistically significant in phase 2 (r = -0.724, 95% CI -0.804; -0.486, p < 0.001), phase 3 (r = -0.719, 95% CI -0.834; -0.553, p < 0.001), and phase 4 (r = -0.908, 95% CI -0.824; -0.531, p < 0.001) (

Figure 5).

4. Discussion

Although previous studies have examined the effect of age on short-term cardiovascular compensatory responses [

6,

7], our study is the first to analyze phase-specific cardiovascular responses, including the initial, early, late, and delayed periods, in younger adults and older adults during both sit-to-stand and lie-to-stand transitions. The main findings indicate that immediately on standing, older adults experienced a larger drop in SBP, DBP, MAP, and SVR, as well as blunted increases in HR and CO, but exhibited higher SV responses. Older adults had attenuated short-term compensatory responses in phases 1 (initial) and 2 (early) across SBP, DBP, MAP, SVR, CO, and HR. They also showed a lower peak HR and CO response, alongside a larger SV compensatory response throughout phases 1 to 4. Regarding the matching between ΔCO and ΔSVR, which reflects the timing of BP regulation, older adults exhibited significant negative correlations across all phases (1-4) during sit-to-stand and phases 2-4 during lie-to-stand transition. These findings indicated that under lower gravitational stress, older adults were able to regulate BP within 30 seconds of standing, but younger adults could not. However, during the lie-to-stand transition, significant negative correlations were observed in phases 2-4, indicating that older adults require more time (30-60 s) to regulate BP effectively.

Short-Term Cardiovascular Compensatory Responses Across Phases During Active Standing Orthostatic Stress

The short-term cardiovascular compensatory phases (1-4) and expected physiological responses are described in

Figure 2. To date, no study has directly compared the short-term time course of cardiovascular compensation between older and younger adults in all these phases following active standing orthostatic stress. Therefore, this discussion primarily draws on a limited number of studies that examined these responses separately by age group, as well as studies involving passive maneuvers (head-up tilt), despite the inherent differences between active and passive postural transitions.

In this study, SBP, DBP, and MAP responses during sit-to-stand did not differ between older and younger adults in the first 30 seconds (phase 1). However, during lie-to-stand, older adults showed slower BP recovery, requiring more than 30 s (phase 2) to return to initial values. Consistent with our results, Ten Harkel et al. [

26] reported that SBP and DBP returned to baseline within 20 seconds in younger males (22-40 years old) after lie-to-stand. Finucane et al. [

5] investigated 4475 middle-aged and older adults (62.8 ± 9.2 years) during lie-to-stand and reported delayed SBP stabilization, within 20-30 s in males and 30 s in females aged 50-69 years, but up to 60 s in males and 90 s in females aged ≥ 70 years. Similarly, DBP stabilization occurred within 40 s for those aged 50-69 years, but did not return to baseline in those aged ≥ 70 years.

In the current study, during phases 1 (0-30 s) and 2 (30-60 s), older adults exhibited diminished SVR response compared to younger adults in both conditions, consistent with previous studies [

9,

27]. Additionally, older adults demonstrated a blunted HR short-term compensatory response across all phases during both active standing orthostatic stress, consistent with the findings from Wieling et al. [

7] and Kim et al. [

27]. Wieling et al. [

7] reported lower HR in older adults at 1, 2, and 5 minutes after lie-to-stand, while Kim et al., [

27] observed smaller HR increases in older adults at 5 minutes after standing. In contrast, CO responses in the present study were similar between groups across all phases. Interestingly, older adults showed a higher SV compensatory response in all phases (1 to 4) of sit-to-stand and in phases 1 to 3 of lie-to-stand. Partially agreeing with our results, Wieling et al. [

7] found no age-related differences in CO percentage changes at 1 and 2 minutes after lie-to-stand, although they did not report a greater CO drop in older adults at 5 minutes. The authors also reported a smaller SV percentage drop in older adults at 1, 2, and 5 minutes on standing.

Cardiac Output and Systemic Vascular Resistance Matching Responses During Active Standing Orthostatic Stress

During postural transitions, the coordination/matching between ΔCO and ΔSVR is essential for maintaining MAP and ensuring adequate cerebral blood flow [

4,

25]. This is the first study to examine the correlation between ΔCO and ΔSVR across specific phases, aiming to determine the timing of BP regulation relative to baseline values. Given the novelty of this analysis, the discussion focuses on the physiological aspects of cardiovascular responses. During sit-to-stand, older adults exhibited a significant negative correlation between CO and SVR across all phases, whereas younger adults showed this correlation from phases 2 to 4. In lie-to-stand, older adults showed a significant negative correlation from phases 2 to 4, while younger adults displayed this correlation across all phases.

These findings indicate that older adults regulate BP within 30 s (phase 1) during sit-to-stand, demonstrating that they can still compensate under a lower gravitational stress challenge, unlike younger adults, who took longer to regulate BP in lower gravitational stress. This delayed regulation in younger adults may be partially explained by their greater vascular compliance, which facilitates peripheral blood pooling and may delay venous return and subsequent BP recovery in lower gravitational stress [

25]. Additionally, the relatively lower gravitational stress of the sit-to-stand transition may not be sufficient to provoke substantial autonomic or hemodynamic modulation in individuals with preserved cardiovascular regulatory capacity [

28]. Another factor that may partially explain this response in younger adults is the speed of transition. Younger adults likely stand up more quickly than older adults, which may require slightly more time for the cardiovascular system to adjust due to the rapid gravitational shift [

29,

30], a factor that may not affect older adults in the same way.

In contrast, in lie-to-stand, older adults exhibit delayed BP regulation, achieving matching between ΔCO-ΔSVR after 30 s (phase 2). This delayed response may reflect the diminished efficiency of cardiovascular and autonomic compensatory responses, including slower baroreflex activation [

4], delayed vasoconstriction [

25], and reduced autonomic response [

31]. Consequently, older adults exhibited impaired rapid responses to counteract the sudden BP drop and increased blood pooling in the lower extremities under higher orthostatic stress.

Limitations

This study has limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. Medication used was recorded but not controlled, which could have influenced cardiovascular responses during active orthostatic stress. Many older adults take antihypertensives, beta-blockers, or diuretics, which may affect HR, BP, and vascular resistance [

32]. While these medications may have impacted compensatory responses under investigation, they also reflect real-world conditions, making the findings more applicable to the community-dwelling older population.

In young female participants, the menstrual cycle phase was not controlled. However, its impact on cardiovascular responses remains controversial in the literature. Studies have suggested that estrogen levels influence vascular tone [

4,

33] and hemodynamic responses during postural transitions [

34,

35]. Conversely, other studies report no significant effects on hemodynamic responses [

36,

37]. Therefore, whether and how the menstrual cycle affected our results, and the extent of this influence, remains uncertain. However, it is unlikely to have substantially altered the overall findings of this study. Sex and frailty are potential confounders that should be acknowledged as limitations. Future research should explore how these factors impact cardiovascular responses during active standing orthostatic stress.

5. Conclusions

Older adults experienced a more pronounced drop in BP and SVR, along with delayed short-term compensatory responses compared to young adults, indicating impairments in cardiovascular regulation. They also showed a blunted HR compensatory response during both transitions. Despite this, SV was higher in older adults, indicating a greater reliance on SV as a compensatory response to attenuating BP drops. Regarding BP stabilization, older adults required more time under higher gravitational orthostatic stress, achieving regulation between 30 and 60 s after standing (phase 2), but not under lower gravitational stress (phase 1). Overall, our findings highlight that older adults exhibit delayed and less effective short-term cardiovascular responses during active standing, which may contribute to increased risk of orthostatic hypotension, orthostatic intolerance, or falls in daily life.

Author Contributions

DGM: project administration, review and editing, writing original draft, formal analysis, data curation, visualization. JLS: review, editing, and data curation. FA, SC, GG, AS, SR, RO: review and editing, visualization. TD and RV: project administration, writing, review, editing, supervision, formal analysis, and conceptualization.

Funding

This research was partially supported by the Manitoba Medical Service Foundation (#2021-11) (RV), Centre on Aging, University of Manitoba Research Fellowship (RV), University of Manitoba Retirees Association Scholarship (DM), Center on Aging Betty Havens Memorial Graduate Fellowship (DM), and Jack MacDonell Scholarship for Research in Aging (DM).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval was granted by the University of Manitoba Health Research Ethics Board (approval number - HE2022-0058) on 26 April 2022.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

ACE - Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme

ARB - Angiotensin Receptor Blocker

BMI - Body Mass Index

BP - Blood Pressure

CI - Confidence Interval

CO - Cardiac Output

CO-SVR - Cardiac Output-Systemic Vascular Resistance matching

CSEP - Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology

DBP - Diastolic Blood Pressure

ECG - Electrocardiogram

FDR - False Discovery Rate

HR - Heart Rate

IQR - Interquartile Range

MAP - Mean Arterial Pressure

OA - Older Adults

OH - Orthostatic Hypotension

OI - Orthostatic Intolerance

SBP - Systolic Blood Pressure

SD - Standard Deviation

STROBE - Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology

SV - Stroke Volume

SVR - Systemic Vascular Resistance

YA - Younger Adults

References

- van Wijnen, V.K.; Hove, D. Ten; Finucane, C.; Wieling, W.; van Roon, A.M.; Ter Maaten, J.C.; Harms, M.P.M. Hemodynamic Mechanisms Underlying Initial Orthostatic Hypotension, Delayed Recovery and Orthostatic Hypotension. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2018, 19, 786–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Matos, D.G.; de Santana, J.L.; Aidar, F.J.; Cornish, S.M.; Giesbrecht, G.G.; Mendelson, A.A.; Duhamel, T.A.; Villar, R. Cardiovascular Regulation during Active Standing Orthostatic Stress in Older Adults Living with Frailty: A Systematic Review. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2025, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorowski, A.; Fanciulli, A.; Raj, S.R.; Sheldon, R.; Shibao, C.A.; Sutton, R. Cardiovascular Autonomic Dysfunction in Post-COVID-19 Syndrome: A Major Health-Care Burden. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehrwein, E.A.; Joyner, M.J. Regulation of Blood Pressure by the Arterial Baroreflex and Autonomic Nervous System. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2013, 117, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finucane, C.; O’Connell, M.D.L.; Fan, C.W.; Savva, G.M.; Soraghan, C.J.; Nolan, H.; Cronin, H.; Kenny, R.A. Age-Related Normative Changes in Phasic Orthostatic Blood Pressure in a Large Population Study: Findings from the Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA). Circulation 2014, 130, 1780–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, E. PHYSIOLOGICAL RESPONSES TO POSTURAL CHANGE YOUNG AND OLD HEALTHY INDIVIDUALS IN ThE SYr ~ DROME of Postural Hypotension Increases in Incidence with Increasing Age so That up to 20070 of Old People Suffer from the Syndrome ( Rodstein and Zeman , 1957 ; Joh. 1983, 17, 445–451.

- Wieling, W.; Veerman, D.P.; Dambrink, J.H.A.; Imholz, B.P.M. Disparities in Circulatory Adjustment to Standing between Young and Elderly Subjects Explained by Pulse Contour Analysis. Clin. Sci. 1992, 83, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawaguchi, T.; Uyama, O.; Konishi, M.; Nishiyama, T.; Iida, T. Orthostatic Hypotension in Elderly Persons during Passive Standing: A Comparison with Young Persons. Journals Gerontol. - Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2001, 56, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.J.; Hughes, C. V.; Ptacin, M.J.; Barney, J.A.; Tristani, F.E.; Ebert, T.J. The Effect of Age on Hemodynamic Response to Graded Postural Stress in Normal Men. Journals Gerontol. 1987, 42, 406–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.A.; Fasler, J.J. Age-Related Changes in Autonomic Function: Relationship with Postural Hypotension. Age Ageing 1983, 12, 206–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for Reporting Observational Studies. Int. J. Surg. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines for Older Adults 65 Years and Older; CSEP, Ed.; Ottawa, 2011.

- Guelen, I.; Westerhof, B.E.; Van Der Sar, G.L.; Van Montfrans, G.A.; Kiemeneij, F.; Wesseling, K.H.; Bos, W.J.W. Finometer, Finger Pressure Measurements with the Possibility to Reconstruct Brachial Pressure. Blood Press. Monit. 2003, 8, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finapres Medical Systems FinometerTM User’s Guide 2005.

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A Flexible Statistical Power Analysis Program for the Social, Behavioral, and Biomedical Sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Velde, N.; Van Den Meiracker, A.H.; Stricker, B.H.C.; Van Der Cammen, T.J.M. Measuring Orthostatic Hypotension with the Finometer Device: Is a Blood Pressure Drop of One Heartbeat Clinically Relevant? Blood Press. Monit. 2007, 12, 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mol, A.; Slangen, L.R.N.; Trappenburg, M.C.; Reijnierse, E.M.; van Wezel, R.J.A.; Meskers, C.G.M.; Maier, A.B. Blood Pressure Drop Rate after Standing up Is Associated with Frailty and Number of Falls in Geriatric Outpatients. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Ortuno, R.; Cogan, L.; Fan, C.W.; Kenny, R.A. Intolerance to Initial Orthostasis Relates to Systolic BP Changes in Elders. Clin. Auton. Res. 2010, 20, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, C.H.; Freeman, R. Delayed Orthostatic Hypotension: A Frequent Cause of Orthostatic Intolerance. Neurology 2006, 67, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, J.I.; Moon, J.; Kim, D.Y.; Shin, H.; Sunwoo, J.S.; Lim, J.A.; Kim, T.J.; Lee, W.J.; Lee, H.S.; Jun, J.S.; et al. Delayed Orthostatic Hypotension: Severity of Clinical Symptoms and Response to Medical Treatment. Auton. Neurosci. Basic Clin. 2018, 213, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoav Benjamini and Yosef Hochberg Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. 1995, 57, 289–300.

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 1992, 1, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerby, D.S. The Simple Difference Formula: An Approach to Teaching Nonparametric Correlation. Compr. Psychol. 2014, 3, 11.IT.3.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.S.; Bogert, L.W.J.; Immink, R. V.; Harms, M.P.M.; Colier, W.N.J.M.; Van Lieshout, J.J. Effects of Aging on the Cerebrovascular Orthostatic Response. Neurobiol. Aging 2011, 32, 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohrman;, D.L.H. Cardiovascular Physiology; 8th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education, 2013; ISBN 0071793119.

- Ten Harkel, A. D.J., Van Lieshout J. J., W.W. Assessment of Cardiovascular Reflexes: Influence of Posture and Period Preceding Rest. Eurorehab 1990, 147–153. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.S.; Bogert, L.W.J.; Immink, R. V.; Harms, M.P.M.; Colier, W.N.J.M.; Van Lieshout, J.J. Effects of Aging on the Cerebrovascular Orthostatic Response. Neurobiol. Aging 2011, 32, 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeidifard, F.; Medina-Inojosa, J.R.; Supervia, M.; Olson, T.P.; Somers, V.K.; Prokop, L.J.; Stokin, G.B.; Lopez-Jimenez, F. The Effect of Replacing Sitting With Standing on Cardiovascular Risk Factors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Mayo Clin. Proc. Innov. Qual. Outcomes 2020, 4, 611–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Bruïne, E.S.; Reijnierse, E.M.; Trappenburg, M.C.; Pasma, J.H.; De Vries, O.J.; Meskers, C.G.M.; Maier, A.B. Standing Up Slowly Antagonises Initial Blood Pressure Decrease in Older Adults with Orthostatic Hypotension. Gerontology 2017, 63, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, J.D.; O’Connell, M.D.L.; Nolan, H.; Newman, L.; Knight, S.P.; Kenny, R.A. Impact of Standing Speed on the Peripheral and Central Hemodynamic Response to Orthostasis: Evidence from the Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing. Hypertension 2020, 75, 524–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieling, W.; Karemaker, J.M. Measurement of Heart Rate and Blood Pressure to Evaluate Disturbances in Neurocardiovascular Control. Auton. Fail. 2013, 290–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.; Abuzinadah, A.R.; Gibbons, C.; Jones, P.; Miglis, M.G.; Sinn, D.I. Orthostatic Hypotension: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 72, 1294–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stice, J.P.; Lee, J.S.; Pechenino, A.S.; Knowlton, A.A. Estrogen, Aging and the Cardiovascular System. Future Cardiol. 2009, 5, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Q.; Vangundy, T.B.; Shibata, S.; Auchus, R.J.; Williams, G.H.; Levine, B.D. Menstrual Cycle Affects Renal-Adrenal and Hemodynamic Responses during Prolonged Standing in the Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome. Hypertension 2010, 56, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankhwar, V.; Urvec, J.; Steuber, B.; Schmid Zalaudek, K.; Salon, A.; Hawliczek, A.; Bergauer, A.; Aljasmi, K.; Abdi, A.; Naser, A.; et al. Effects of Menstrual Cycle on Hemodynamic and Autonomic Responses to Central Hypovolemia. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Q.; Okazaki, K.; Shibata, S.; Shook, R.P.; Vangunday, T.B.; Galbreath, M.M.; Reelick, M.F.; Levine, B.D. Menstrual Cycle Effects on Sympathetic Neural Responses to Upright Tilt. J. Physiol. 2009, 587, 2019–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claydon, V.E.; Younis, N.R.; Hainsworth, R. Phase of the Menstrual Cycle Does Not Affect Orthostatic Tolerance in Healthy Women. Clin. Auton. Res. 2006, 16, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).