1. Introduction

Perceptual experience has been defined by modern neurobiological models of consciousness as a phenomenon that emerges from the interaction between interoceptive and proprioceptive processes on the one hand and exteroceptive information on the other [1, 2, 3]

Exteroceptive perception, proprioception, and interoception are closely intertwined: the way we perceive a face, a facial expression, or a scene is influenced by the muscular, vegetative, affective, and emotional tone of our body and influences our behavioral response [

4]. The embodied mind theory approach, considering cognitive processes as the result of an integration between body, brain, and surrounding environment, recognizes the illusory nature of the objectivity of perception [

5]. This attribution of equal dignity to the external and internal environments and the conception of a mind embodied in the individual's being in the world is also shared by Gestalt psychotherapy.

Gestalt psychotherapy shares this non-dualistic conception of human experience with the embodied approach, but takes it beyond the purely cognitive dimension towards a radically relational and phenomenological understanding. In the Gestalt paradigm, in fact, the body is not simply the biological substrate of the mind, nor a mere executor of cognitive processes: it is the primary organ of contact, the place where experience becomes present and meaningful in the encounter with the environment [4, 6].

This conception of the body as an organ of contact introduces a particularly fertile theoretical perspective for understanding the relationship between interoception and personality. In the theory of the organism-environment field, developed by Gestalt, experience is neither purely 'internal' nor purely 'external', but emerges at the boundary of contact between organism and environment, in a continuous co-creation of meanings [7, 8]. In this perspective, interoception does not simply represent the perception of isolated bodily signals but constitutes a fundamental dimension of this contact process: it is through sensitivity to internal states that the organism orients itself in the field, regulates its functioning, and shapes its experience of itself.

The "es" function, in Gestalt theory, represents the pre-reflective and bodily dimension of the perceptual field, which encompasses sensorimotor memories, affective states, and patterns of organismic arousal [

7]. It constitutes the subjective substrate of perception, influencing what emerges as "figure" from the undifferentiated "background" of the field. The "id" is therefore based on bodily and emotional experiences—that is, on deeply interoceptive processes—which influence perception and are in turn modified by perception itself, in a dynamic and inseparable circularity. This circularity directly recalls modern neurobiological models of consciousness that describe perceptual experience as the result of the integration of interoceptive, proprioceptive, and exteroceptive processes [1, 9].

What makes the Gestalt perspective particularly relevant to the present reflection is its ability to offer a phenomenological bridge between neuroscientific data on interoception and the psychological understanding of personality. Neuroscience describes

how the body communicates with the brain through afferent pathways and specific brain structures: Gestalt redefines this communication in the context of lived experience and the relationship with the environment. Personality, therefore, rather than being traced back to brain configurations or psychometric traits, represents the form that the contact process takes over time, the relatively stable mode through which an organism organizes its own arousal, perceives and responds to the field, and regulates the boundary between itself and the environment [

6].

Interoception therefore represents a fundamental dimension through which this process of organization takes place. Sensitivity or insensitivity to one's internal states, accuracy or distortion in their perception, the ability to trust or distrust bodily sensations—all dimensions of interoception—are fundamental aspects of how a person contacts themselves and the world. Greater interoceptive sensitivity, for example, can translate into a more reflective and internalized mode of contact (introversion), or greater vulnerability to emotional arousal (neuroticism), depending on how that sensitivity is integrated into the overall functioning of the organism.

In summary, Gestalt theory offers a conceptual paradigm that can serve as a unifying framework for integrating neuroscientific evidence on interoception with psychological models of personality [4, 6, 7, 8]. Three elements make this perspective particularly promising:

Overcoming mind-body dualism: Gestalt conceives of human experience as a unitary process that unfolds at the contact boundary, avoiding both biological reductionism and cognitive abstraction. In this framework, interoceptive processes and personality traits are not separate entities to be correlated, but co-emergent aspects of a single organismic process.

The relational dimension: while many approaches to interoception treat it as a predominantly individual and introspective phenomenon, Gestalt situates it in the context of the organism-environment relationship. Interoception is not only self-perception, but orientation in the field, regulation of contact, modulation of relational presence.

The focus on process: Gestalt does not limit itself to describing states or traits, but focuses on the dynamic processes through which experience is organized moment by moment. This allows us to understand personality not as a fixed structure, but as a relatively stable processual pattern of organismic self-regulation, rooted in recurring modes of perception, arousal, and contact.

This article does not intend to present new empirical data, but to propose a theoretical-conceptual reflection on the relationship between interoceptive processes and personality traits, with the aim of integrating neuroscientific, psychological, and Gestalt perspectives into a unified mind-body model.

2. Methodology

This work is a theoretical-conceptual reflection based on an integrative narrative review approach. Peer-reviewed articles published between 2000 and 2024 in the PubMed, PsycINFO, and Scopus databases were selected, covering the topics of "interoception," "personality traits," "Gestalt therapy," and "embodied cognition." We selected articles that explicitly addressed interoception, personality traits, embodied self-regulation, or phenomenological approaches to mind–body integration, emphasizing empirical studies of psychophysiological correlates of personality (extraversion–introversion, neuroticism–stability) and theoretical work linking neuroscientific evidence to experiential or relational frameworks. The analysis focused on identifying areas of theoretical convergence and potential lines of empirical research.

3. Interoception: Definitions and Models

In the context of this theoretical reflection, interoception is a key construct for understanding the link between body, emotion, and personality. It describes the way in which individuals experience and attribute meaning to internal physiological states, forming an essential basis for self-awareness and emotional regulation processes.

Interoception differs from exteroception, which is the perception of stimulation coming from outside the body, and proprioception, which is the perception of the body's position in space [

10]. Generally, interoceptive signals are considered to be those related to hunger, satiety, itching, thirst, muscular, bladder, gastrointestinal, respiratory, and cardiac effort, temperature, blood (pH, glucose level), vasomotor flushing, air hunger, shivering, sensual touch, genital sensation, bruising, headache, broken bones, and many other visceral sensations [

11]. Definitions of this construct tend to consider as interoceptive those bodily signals that are sent through lamina 1 to the anterior insula or anterior cingulate cortex [

12], or through the cranial nerves (vagus and glossopharyngeal) to the nucleus of the solitary tract [

13].

An important aspect of interoception, currently the subject of scientific debate, is the multiple levels of cognitive representation at which this phenomenon can occur implicit homeostasis, conscious perception of a signal without recognition of the specific signal, recognition without the need for a verbal label, and verbal labeling of the signal [

14]. Measurements of interoception, therefore, concern different levels of this hierarchy.

In order to distinguish between objective, subjective, and metacognitive aspects of interoception, Garfinkel and Critchley (2013) developed a tripartite model that distinguishes this construct into three aspects or levels of processing [

15]: interoceptive accuracy, which is the process of accurately detecting internal bodily sensations; interoceptive sensitivity, which represents the individual's self-reported beliefs about their own attention and accuracy in perceiving internal signals; and finally, interoceptive awareness, which represents a metacognitive measure of the correspondence between objective interoceptive accuracy and self-assessed interoceptive sensitivity.

With regard to the measurement of this construct, most studies on interoceptive accuracy have relied almost exclusively on measures of heartbeat counting (HCT) or discrimination (HDT). Respiratory and gastric tests are also measures used to assess interoceptive ability. There are also self-assessment measures that evaluate self-reported interoception, or interoceptive sensitivity [

15], such as the Body Perception Questionnaire (BPQ) [

16] and the Multidimensional Assessment of Interoceptive Awareness (MAIA) [

17].

In psychology and cognitive neuroscience, interoception has been studied mainly in relation to the phenomenon of emotional processing: interoceptive accuracy, which is fundamental for detecting emotional signals and judging emotional intensity [

18], is related to emotional lability [

19] , emotion regulation [20; 21], focus on arousal [

22], and emotional intensity [20, 23, 24, 25, 26] and reduced pain tolerance [27, 28]. There are also associations between specific internal states and particular emotions, such as that between disgust and cardiac and gastric activity [

29], anger and increased heart rate and temperature [30, 31], fear and increased heart rate and blood pressure [30, 32], and surprise and increased skin conductance and decreased pulse blood volume (variation in blood volume per heartbeat).

In addition to this, some studies have shown that, in addition to influencing self-focused emotional processing, interoceptive abilities are linked to greater reactivity to the emotions of others [33, 34, 35].

Given the importance of interoception in typical functioning, which affects not only emotional processing but also learning and decision-making, many studies have investigated interoceptive impairment in various psychopathological conditions: atypical interoception is, in fact, ubiquitous in all psychiatric and neurological conditions [36, 37, 38]. Most of the existing work on interoception and psychopathology, however, consists of correlational designs, suggesting that the relationship between these two phenomena is complex and potentially variable depending on the conditions [14, 39].

Taken together, this evidence suggests that interoception is a fundamental dimension of subjective experience and psychological regulation. Not only does it enable the perception of bodily states, but it also acts as a bridge between somatic experience and processes of meaning-making, thus paving the way for integration with personality models and psychotherapeutic theories that recognize the body as a locus of awareness and relationship.

3.1. Terminological Clarifications: Interoception and Arousal

The construct of interoception and the concept of physiological arousal are often used interchangeably in the literature but represent distinct theoretical concepts. Physiological arousal refers to the objective level of activation of the autonomic nervous system, measurable by cardiovascular and electrodermal parameters. Interoception represents the subjective perception and interpretation of these physiological states [40, 41].

In this article, when referring to Eysenck's personality theory and the ARAS (ascending reticular activating system), we distinguish between basal arousal and the perception of arousal. The former represents an individual's objective level of neural excitation, which varies systematically and is higher in introverts and lower in extroverts. The perception of arousal (interoception) represents the subjective awareness and cognitive evaluation of basal arousal.

In the Gestalt perspective, the term "excitement" is used in a broader and more phenomenological sense, referring not only to physiological arousal but also to the energy mobilized by the organism in response to an emerging need, with a strong component of meaning and intentionality [

4].

This distinction will be important for understanding how neuroscientific data on arousal translates into the language of embodied experience and relationship.

4. Personality: Neuropsychological and Psychological Perspectives

The study of personality has always been a central theme in psychology, as it reflects the uniqueness of the individual and their way of perceiving, feeling, and acting in the world. In this article, the integrated perspective links the analysis of personality with that of interoception, both interpreted as ways in which the organism organizes internal and external experience, maintaining a dynamic balance between arousal, regulation, and contact [

42].

According to Eysenck's personality theory (1967), individual behavior is linked to relatively stable and partly hereditary traits. [

43]. Personality differences, attributable to biological factors, depend on the balance between excitatory and inhibitory neural mechanisms. Eysenck's model distinguishes three main traits: extraversion, neuroticism, and psychoticism, associated with two fundamental brain systems: the reticular-cortical and reticular-limbic circuits, regulated by the ARAS (ascending reticular activating system) in the reticular formation of the brainstem [43, 44].

Extraversion-introversion is influenced by the arousal of the reticular-cortical circuit in response to external stimuli. In introverts, the ARAS generates high neural activation, inducing behaviors aimed at limiting external stimulation. In extroverts, on the other hand, the ARAS is less active, promoting stimulus-seeking behaviors to compensate for underactivation [45, 46].

Neuroticism is related to the arousal of the limbic reticular circuit in response to emotional stimuli. Individuals with high levels of neuroticism show greater excitement to emotional stimuli, while more emotionally stable individuals show more restrained responses [45, 46]. Neuroimaging evidence confirms the relationship between personality traits and the structure/functioning of specific brain regions [

47]. Based on these data, it can be hypothesized that those with high introversion and neuroticism exhibit higher autonomic activity than those who are extroverted and emotionally stable.

Cardiovascular and electrodermal measures are common tools for observing differences in arousal between personality types [

46]. Studies such as those by Richards and Eves (1991) [

48] and Matthews and Gilliland (1999) [

46] have confirmed that introverts show an increase in heart rate in response to auditory stimuli, a result consistent with that observed by Harvey and Hirschmann (1980) [

49]. On an electrodermal level, Wilson (1990) [

50] found higher levels of skin conductance in introverts, which was confirmed by Matthews and Gilliland (1999) [

46]. More recent studies emphasize the importance of neuroticism: Norris et al. (2007) [

51] found that it predicts greater electrodermal reactivity to aversive visual stimuli, while Reynaud et al. (2012) observed more intense skin responses to scary movies in neurotic subjects [

52].

Considering this evidence and the characteristics of personality traits related to arousal, a correlation between personality type and sensitivity to internal stimuli, i.e., interoception, seems plausible. Neuropsychological models, therefore, can serve as a bridge between bodily and mental functioning, suggesting that personality traits reflect stable modes of interoceptive regulation. In this sense, introversion and neuroticism could be associated with greater sensitivity to internal states, while extroversion and emotional stability could be associated with less interoceptive resonance, favoring a more embodied understanding of the self.

5. Interoception and Personality: Theoretical Convergences

The analysis of interoception and personality shows relevant theoretical convergences: both describe how the organism regulates its internal states in relation to the context, translating physiological processes into relatively stable subjective experiences. Neuropsychological and psychophysiological models indicate that personality is not only cognitive, but a dynamic set of bodily, emotional, and relational patterns, suggesting possible relationships between personality and interoception

According to biological personality theory, one would expect a close connection between sensory interoception and personality types related to arousal. Sensory behavioral measures, such as heart rate detection, are direct tools for investigating the relationship between actual (personality-related) and perceived (interoceptive) arousal.

Some evidence supports this idea, although existing studies have focused primarily on heart rate detection tasks or unidimensional questionnaires such as the BPQ [

53], making it difficult to draw definitive conclusions. For example, using Eysenck's theory, neuroticism stability could be linked to higher-order interoceptive dimensions, such as the ability to “trust” one's bodily sensations, as assessed by the MAIA.

The reticular-limbic circuit, responsible for neuroticism, regulates emotional reactivity to stimuli and subsequent experiences [

47]. Neurotic individuals, characterized by high sensitivity to bodily stimuli and greater concern about them, may find it difficult to respond affirmatively to MAIA questions such as “I trust my bodily sensations.”

Although research is still limited, examining different interoceptive dimensions in relation to personality may guide future studies. Some studies have investigated traits such as sensation seeking [

54], psychopathy, narcissism, and Machiavellianism [

55], while few have considered extraversion-introversion and neuroticism-stability.

For example, Pollatos et al. (2007) [

25] found a positive correlation between trait anxiety and interoceptive awareness (heartbeat perception score), which can be explained by the increased reactivity of the autonomic system in anxious individuals. Critchley et al. (2004) and Dunn et al. (2010) [56, 57] observed similar results in fMRI studies. Ewing et al. (2017) [

58] showed that poor sleep quality increases interoceptive sensitivity in people with anxiety and/or depression. Ehlers et al. (2000) found greater interoceptive awareness in subjects with panic disorder [

59].

Studies on subclinical populations, such as those by Mallorquí-Bagué et al. (2014) [

60], show relationships between state anxiety and interoceptive sensitivity, with more pronounced effects in hypermobile subjects. Overall, this evidence suggests a positive link between interoception and anxiety, and indirectly with traits such as neuroticism, which predicts trait anxiety [

61] and greater autonomic arousal [

43].

Ferentzi et al. (2017) highlighted the scarcity of empirical studies on the relationship between personality and interoception [

62]: their study found no significant correlations between extroversion-introversion or neuroticism-stability and interoceptive sensitivity, while a relationship with somatosensory amplification emerged. In contrast, Lyyra and Parviainen (2018) observed a positive association between interoceptive accuracy and introversion [

63].

The available literature shows mixed results due to the variety of measures and tasks used, as well as the predominantly university sampling, an important factor considering the effect of age and gender on interoception [64, 65, 66, 54].

In summary, theoretical and empirical evidence suggests that the neural mechanisms of interoception overlap with those related to extroversion-introversion and neuroticism-stability, hypothesizing that greater interoceptive sensitivity is associated with introversion and neuroticism, while lower sensitivity is associated with emotional stability and openness.

5.1. Critical analysis of Empirical Evidence: Mixed Results and Possible Explanations

The empirical literature on the relationship between interoception and personality presents conflicting results that warrant further discussion. While some research supports the hypothesis of a correlation between greater interoceptive sensitivity and introversion-neuroticism, other studies find no significant associations.

Lyyra and Parviainen (2018) [

63] reported a positive association between interoceptive accuracy (measured with a heartbeat discrimination task) and introversion, using both the Karolinska Scales of Personality and the Adult Temperament Questionnaire. Similarly, several correlational studies have documented positive associations between neuroticism and interoceptive sensitivity in clinical and subclinical populations [24, 56, 59]. These findings are consistent with Eysenck's theory of the relationship between basal arousal and personality.

However, Ferentzi et al. (2018), in a study of university students, found no significant correlations between extraversion-introversion or neuroticism-stability (measured with the Big Five Inventory) and interoceptive sensitivity (measured with the Body Awareness Questionnaire) [

62]. They found a correlation only with somatosensory amplification, which reflects a tendency to interpret bodily sensations as symptoms of illness, rather than an ability to detect them accurately. This discrepancy suggests that the relationship between personality and interoception may be more complex than a simple direct association.

The presence of such discrepancies in the empirical landscape could be explained by three methodological factors. First, the studies described used different operationalizations of interoception. Lyyra and Parviainen used an objective measure of accuracy, namely a behavioral cardiac discrimination task, while Ferentzi et al. used a self-administered body awareness questionnaire, which is a subjective measure [63, 62]. As described in Garfinkel and Critchley's tripartite model, accuracy and awareness represent distinct aspects of interoception. It is possible that personality traits correlate differently with each aspect: for example, neuroticism may be associated with greater self-reported sensitivity (hypervigilant concern with bodily sensations) but not necessarily with greater objective accuracy in detecting signals.

The sample chosen may represent another methodological factor responsible for the empirical divergences observed. Ferentzi et al. used only university students, while Lyyra and Parviainen included participants of various age groups [62, 63]. The effects of gender [

66] and age [

64] on interoception have been documented. It is possible that the relationship between personality and interoception manifests differently at different stages of life or across genders.

Furthermore, a gap in the literature is the role of conscious regulation and cognitive interpretation of interoceptive signals. For example, a neurotic individual may have high interoceptive accuracy that allows them to detect bodily signals but even higher self-managed sensitivity due to anxious hypervigilance. An emotionally stable individual may have moderate interoceptive sensitivity but superior metacognitive awareness [

15]. These fine distinctions are not always captured by the measures used in studies.

Based on the available theoretical and empirical evidence, it can be hypothesized with reasonable confidence that introversion is associated with greater interoceptive accuracy. It is plausible, although requiring further verification, that neuroticism correlates with greater self-managed sensitivity and metacognitive impairment. Finally, it is proposed as a working hypothesis that emotional stability is characterized by integrated interoceptive awareness. This gradual model, which distinguishes empirically supported aspects from more speculative ones, provides a basis for future empirical investigations using Garfinkel and Critchley's comprehensive tripartite model, rather than unidimensional measures of interoception, and sets the stage for the Gestalt reinterpretation that follows.

5.2. Toward a Gestalt Interpretation: Personality Traits as Embodied Contact Style

The theoretical and empirical evidence outlined thus far suggests that the neural foundations of interoception functionally overlap with those of arousal-related personality traits, particularly extraversion-introversion and neuroticism-stability.

This psychophysiological correlation, however significant, does not exhaust our understanding of the phenomenon. This is where the Gestalt perspective offers an essential interpretative contribution, allowing us to move from describing correlations to understanding the process through which interoception and personality co-constitute each other in lived experience.

In Gestalt theory, the body represents the "measure" of experience: it is through its resonances, tensions, and rhythms that the organism continuously evaluates the quality of contact with the environment [

5]. In this perspective, interoception, rather than a mere detection of discrete physiological signals (heartbeat, muscle tension, gastric activity), constitutes the background tone of the subjective field, the affective tone through which the organism feels present to itself and to the world.

When we talk about interoceptive sensitivity in this article, it is important to distinguish between the neurobiological level of arousal and the phenomenological level of embodied experience. At the neurobiological level of arousal, introverts have a higher basal arousal; at the phenomenological level, this translates into an experience of a denser and more activated internal field. The ability to perceive, tolerate, and modulate this activation (interoception) is therefore the bridge between neurobiological data and lived experience.

From this perspective, personality traits could be understood as relatively stable modes of organizing arousal and contact, rooted in characteristic interoceptive patterns. This aspect differs from the main traits discussed.

Introversion and increased interoceptive sensitivity: Introverts, characterized by greater reactivity of the ascending reticular activating system (ARAS) and therefore higher basal arousal levels [

43], would experience a noisier and more stimulating internal field. In Gestalt terms, we could say that introverts have a greater density of figures emerging from the interoceptive field

: bodily sensations, affective states, and visceral resonances tend to emerge more easily in the figure, requiring attention and processing. This explains both the tendency to withdraw from excessive external stimuli (which would add further excitement to an already activated system) and the preferential orientation towards the internal world. The greater interoceptive accuracy of introverts, documented empirically [

63], could represent a constitutive feature of their contact style: they would be more "tuned in" to their own bodies because the body speaks louder.

Extroversion and exteroceptive orientation: Extroverts, on the other hand, with a less reactive ARAS and therefore lower basal arousal, experience a relatively 'quiet' internal field. Bodily sensations tend to remain in the background and do not easily emerge into the foreground. This would explain the active search for external stimulation: extroverts need more environmental input to reach optimal levels of arousal. In terms of contact, it can be hypothesized that extroverts are predominantly oriented toward the outside world, toward others, toward action in the world. Lower interoceptive sensitivity would not necessarily represent a deficit, but rather an adaptive characteristic of this style that allows the individual to have more fluid and relaxed contact with the environment, unburdened by excessive bodily self-monitoring.

Neuroticism and interoceptive dysregulation: Neuroticism, related to the hyperreactivity of the reticular-limbic circuit to emotional stimuli [

43], could be understood gestaltically as a difficulty in modulating emotional arousal. Neurotic individuals not only perceive interoceptive signals more intensely (as documented by correlations with autonomic arousal), but also tend to interpret them dysfunctionally, as signals of danger or loss of control. This recalls the "Trust" dimension of MAIA [

17]: the difficulty in trusting one's bodily sensations would represent an interruption of intimate contact with oneself. In Gestalt terms, this dynamic is reminiscent of the clinical picture of impairment of the ego function of the self, although this connection remains an interpretative hypothesis to be verified empirically. According to this perspective, the individual is unable to take actions that satisfy their needs and interrupts contact with themselves and their environment through contact interruption mechanisms. These mechanisms are anachronistic responses to past situations and may no longer be functional in the present. In this dynamic, arousal does not flow naturally towards contact and its resolution, but is held back, monitored anxiously, and amplified by the attention focused on it. This would create a vicious circle in which interoceptive hypervigilance increases arousal, which in turn fuels anxiety and hypervigilance.

Emotional stability and interoceptive integration: Emotional stability, on the other hand, would seem to be characterized by an integrated capacity for self-regulation, in which interoceptive signals are perceived in a balanced way, neither ignored nor amplified, and used as reliable guides for action. From a Gestalt perspective, this dynamic could be seen in the light of the proper functioning of the two functions of the Self (Ego function and Personality function) [

4]: the organism accurately perceives its bodily and emotional needs, integrates them into the context of the field, and mobilizes the energy necessary for their satisfaction without excess or deficiency. The body becomes an ally in contact, not an obstacle or a source of concern.

The Gestalt contact cycle [4, 67], which includes the phases of pre-contact, contact initiation, full contact, and post-contact, has a rhythmic pattern that is reflected in the oscillations of interoceptive states. In pre-contact, a vague bodily sensation emerges that signals a need; in contact-taking, bodily arousal intensifies and focuses; in full contact, there is a peak of activation and involvement; in post-contact, the organism relaxes and integrates the experience. From a Gestalt perspective, when the natural contact/withdrawal movement of the cycle is interrupted and goes out of rhythm, pathology emerges. Different personality traits may correspond to different modulations of this interoceptive rhythm.

Introverts may have a slower, more internalized rhythm, with a prolonged pre-contact phase characterized by careful processing of emerging sensations. Extroverts may experience faster transitions, with less processing in the pre-contact phase and more energy in the full contact phase with the environment and post-contact (focus on the environment). Finally, neurotics may show difficulties in transitions, with a pre-contact phase characterized by anticipatory anxiety and a post-contact phase compromised by an inability to let go of excitement. In such cases, the contact cycle tends to manifest itself in a discontinuous and fragmented manner, rather than in a fluid flow of self-regulation.

The Gestalt perspective allows us to understand personality not as a set of abstract traits or as the mere result of neurobiological configurations, but as an embodied gestalt: a relatively stable processual configuration of perception, arousal, contact, and regulation that emerges from the continuous interaction between organism and environment and is rooted in characteristic interoceptive patterns.

In this framework, interoception would represent the voice of the body in the organism-environment dialogue: through sensitivity to internal states, the organism orients itself, evaluates, decides, and acts [

68]. Personality, then, could be considered as the characteristic way in which an individual "listens" to this voice, whether they amplify or attenuate it, whether they trust or distrust it, whether they integrate it fluently into the contact process or experience it as a source of discomfort and concern.

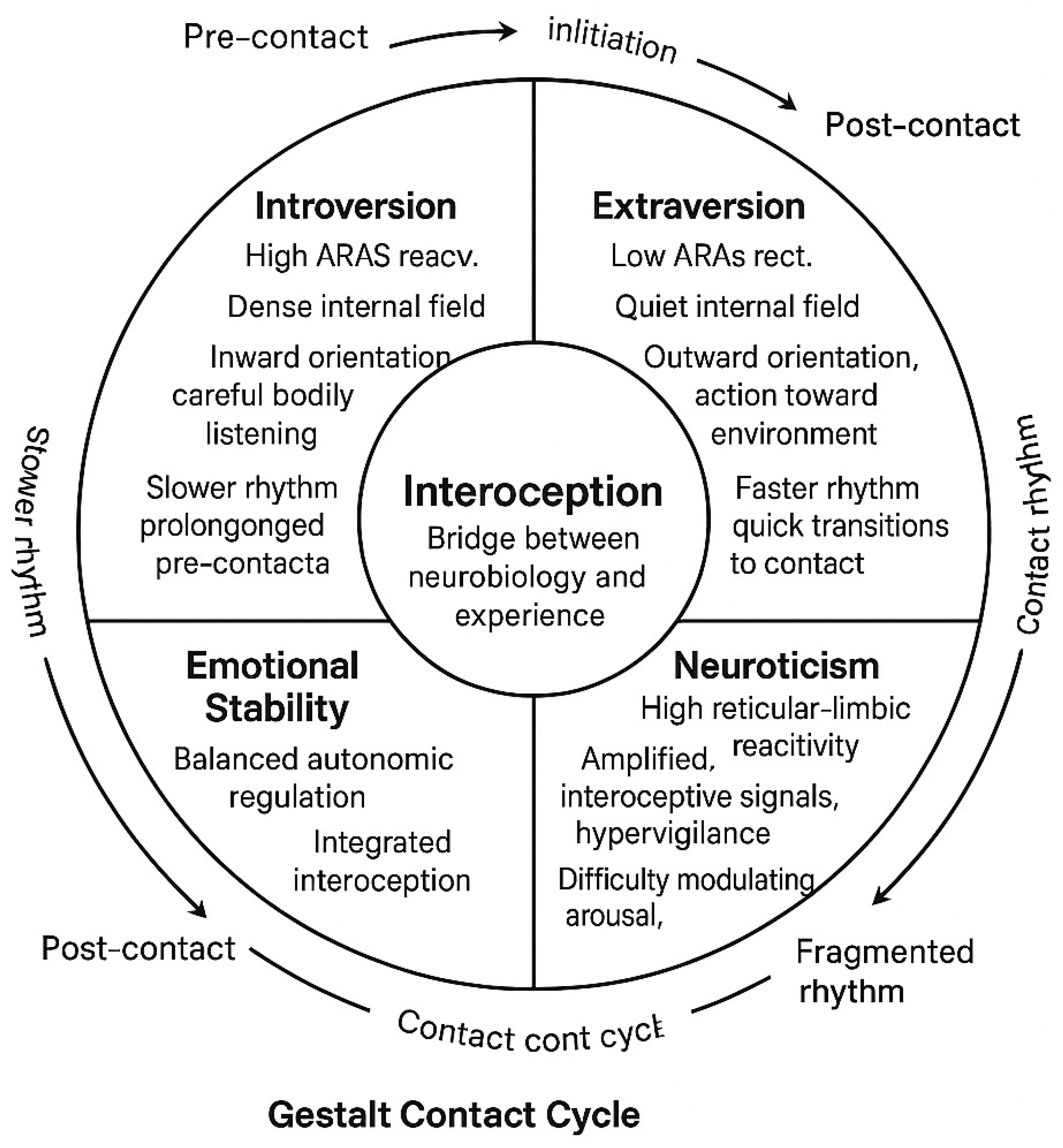

Table 1 and

Figure 1 illustrate the proposed integrative model, showing how interoception bridges neurobiological arousal and lived experience, shaping distinct Gestalt contact styles and rhythmic patterns associated with different personality traits.

The model illustrates how interoception functions as a bridge between neurobiology and lived experience, shaping distinct rhythmic patterns of the Gestalt contact cycle across different personality traits (introversion, extraversion, neuroticism, and emotional stability).

6. Discussion and Implications for Social Sciences

This article has proposed considering interoception not as an isolated process, but as the core through which the neurobiological patterns of personality are embodied in lived experience. By integrating neuroscientific evidence, personality models, and the Gestalt perspective, a unified theoretical framework emerges that transcends the mind-body dualism.

6.1. The Integrated Model: from Neurobiology to Relational Meaning

At the neurobiological level, the ascending reticular activating system (ARAS) and the reticular-limbic circuit modulate the organism's basal level of arousal [

43]. These circuits generate arousal patterns that manifest as specific bodily states: cardiac acceleration, muscle tension, visceral activation. Interoception, through insular and anterior cingulate cortex circuits, transforms these physiological signals into neural representations accessible to consciousness [12, 15].

However, neural translation does not exhaust the phenomenon. At the phenomenological-experiential level, these signals become embodied meanings: heart palpitations are not just sympathetic activation, but become "fear," "excitement," "anxiety" in the concreteness of lived experience. Gestalt field theory illuminates this passage: interoceptive signals constitute the "background tone" of the organism-environment field, the affective tone that colors perception and guides action. Interoception is not the perception of isolated elements, but the manifestation of the figure-ground dynamic through which the organism continuously organizes its experience.

At the relational and behavioral level, according to the Gestalt perspective, this process can be interpreted as the crystallization of stable modes of contact: personality. In this theoretical framework, the introvert's greater interoceptive sensitivity may represent not a neurological deficit, but an adaptive feature of a contact style that favors internal processing. The extrovert's search for stimulation would reflect a less "noisy" interoceptive field, which requires more external input. The neurotic's pattern of interoceptive hypermonitoring and distrust of bodily sensations would represent, instead, an interruption of the contact cycle in which arousal is retained and amplified by anxiety, generating a vicious circle of dysregulation.

Emotional stability, on the other hand, would seem to be characterized by an integrated capacity for self-regulation in which interoceptive signals are accurately perceived, interpreted in a balanced way, and used as reliable guides for action. A possible Gestalt interpretation For Gestalt, this represents the proper functioning of the two functions of the Self (Ego function and Personality function) [

4]: the organism perceives its own bodily and emotional needs, integrates them into the relational context, and mobilizes the energy necessary for conscious contact.

The Gestalt reading of the neuroscientific evidence on interoception does not intend to propose an overlap between models belonging to different levels of analysis, but rather their functional coherence. Neuroscience describes the physiological mechanisms of internal regulation and arousal, while the phenomenological and relational perspective of Gestalt offers a language for understanding how these processes are experienced and expressed in subjective and interpersonal experience. In this sense, the proposed integration does not aim to explain neurobiological phenomena in psychotherapeutic terms, but to promote a conceptual translation between the bodily and experiential planes, recognizing both as complementary aspects of the same embodied self-regulatory process.

6.2. Clinical and Applicative Implications

This integrated model suggests that psychotherapeutic intervention should aim at the conscious integration of interoceptive processes, not their elimination or cognitive control. In Gestalt practice, working on awareness in the here and now [

5] allows the client to recognize their characteristic interoceptive pattern and to experience new ways of connecting with their body and environment. For a neurotic individual, therapeutic work could focus on awareness of interoceptive hypervigilance and the development of trust in one's bodily sensations, reducing the use of contact interruption mechanisms that push the individual to avoid and escape the experience of contact. For an extrovert, therapy could involve consciously exploring their capacity for internal contact, developing access to more reflective dimensions of experience.

Understanding personality in the light of more or less stable interoceptive patterns allows us to abandon a pathologizing view of individuals' relational and behavioral difficulties. From this perspective, they take on the connotation of organic adaptations that have served a useful function for the survival of individuals in a specific phase of life. Therefore, they can be renegotiated in the context of an authentic relationship and conscious contact such as that established between patient and therapist in a Gestalt setting.

6.3. Implications for the Social Sciences, Education, and Organizational Contexts

Although this article is rooted in the neuroscientific understanding of personality and psychotherapeutic practice, the proposed integrated model has significant implications for broader fields of social sciences. This section briefly explores these connections.

Understanding personality as a configuration of characteristic interoceptive patterns offers a new perspective on how individuals learn [

69]. Students with more pronounced introversion profiles may benefit from learning environments that value internal reflection, deep processing, and mindful contact with their own cognitive processes. Conversely, students with higher extroversion profiles may thrive in collaborative learning contexts with greater external stimulation and social interaction. Recognizing that these styles reflect stable modes of interoceptive self-regulation, rather than deficits or capricious preferences, could support a more inclusive and personalized pedagogy. Furthermore, developing somatic awareness programs in schools could help students recognize their characteristic interoceptive patterns and regulate their behavior more consciously [

70].

In the organizational context, understanding personality as an embodied contact style has implications for communication, teamwork, and leadership style. Leaders with heightened interoceptive sensitivity may excel in emotional reading and empathetic support of employees, but may be vulnerable to excessive emotional involvement. Conversely, leaders with lower interoceptive sensitivity may be less vulnerable to emotional stress, but may have difficulty recognizing the emotional needs of teams. Organizations that implement body awareness and self-regulation programs based on Gestalt practice may improve communication, reduce burnout, and promote a more mindful and relational work environment [71, 72].

At the public health level, the proposed integrated model emphasizes the importance of body awareness and self-regulation as protective factors for psychological well-being. Communities that promote somatic awareness practices—such as body scans, mindful movement, and dance movement therapy—may facilitate better emotional regulation and a reduction in stress- and trauma-related symptoms. Furthermore, recognizing how different personality traits correlate with distinct interoception patterns could inform more targeted public health intervention strategies, particularly for neurotic individuals who may benefit from interventions focused on trust in bodily signals and reduction of hypervigilance.

The theoretical implications outlined open up multiple avenues for future research, including ethnographic studies on the processes through which individuals with different personality profiles experience and interpret organizational and cultural contexts, as well as evaluative research on the effectiveness of body awareness programs in educational and organizational settings. Cross-cultural comparative analyses aimed at investigating differences in the interpretation and valorization of interoceptive sensitivity between Eastern and Western cultural traditions are also particularly relevant.

7. Future Directions and Research Implications

This article has proposed a theoretical-conceptual reflection on the relationship between interoception and personality, integrating neuroscientific evidence, psychological models of personality, and the phenomenological-relational perspective of Gestalt psychotherapy. The main contribution is to propose that personality cannot be reduced to either brain configurations or abstract psychometric constructs, but can be defined in light of the interoceptive and relational processes through which an organism stably modulates its contact with the environment.

7.1. Limitations and Methodological Considerations

It is important to emphasize that this work is a theoretical-conceptual reflection, not an empirical study. Although the neuroscientific and psychophysiological evidence cited supports the proposed hypotheses, the explicit connection between the three areas (neurobiology, interoception, and Gestalt personality) remains largely speculative and requires empirical validation. Furthermore, the existing literature presents significant methodological biases: studies on interoception have mainly focused on measuring cardiac awareness (heartbeat detection task), underrepresenting other interoceptive dimensions (gastrointestinal, respiratory, thermoregulatory). This limits the generalizability of the conclusions. Most studies have used small samples (university students), raising questions about the transferability of results to populations that differ in age, culture, and clinical context.

The Gestalt reinterpretation proposed in this work is a hermeneutic operation that aims to integrate empirical data into a coherent phenomenological-relational framework [

73]. This methodological approach is consistent with the tradition of second-generation affective neuroscience and embodied cognition, which recognize the need to integrate neuroscientific levels of analysis with phenomenological and experiential dimensions [74, 75]. Integrative approaches such as interpersonal neurobiology [

76] have demonstrated the fruitfulness of models that link neurobiological patterns to relational and processual dynamics without biological reductionism. Although not directly verifiable through individual empirical studies, this type of theoretical synthesis performs an essential heuristic function: it generates testable hypotheses, guides future research, and offers clinicians conceptual frameworks for understanding complex phenomena that elude one-dimensional perspectives.

7.2. Future Research Directions

Future research should aim to empirically validate the proposed theoretical connections between interoceptive processes and personality traits. Longitudinal and cross-sectional studies could explore how individual differences in accuracy, sensitivity, and interoceptive awareness (assessed, for example, using the Multidimensional Assessment of Interoceptive Awareness, MAIA) [17, 77] relate to the main personality dimensions measured using standardized instruments (such as the NEO-PI-R or the Big Five Inventory) [78, 79].

The integration of subjective and physiological measure, such as heart rate variability, electrodermal activity, and brain imaging of the insular and cingulate regions, would allow for a multilevel analysis capable of linking biological regulation, subjective awareness, and personality expression.

From a psychosocial perspective, research could investigate how interoceptive sensitivity influences emotional regulation, empathy, and interpersonal behaviors in everyday contexts. For example, individuals with greater body awareness may show finer affective attunement and greater relational competence, while low interoceptive sensitivity may be associated with externalizing tendencies or lower emotional awareness. These hypotheses could be tested in educational, clinical, and organizational contexts to assess how interventions focused on interoception or mindfulness affect emotional competence, stress regulation, and relational well-being [80, 81].

Further comparative and cross-cultural studies could also clarify how sociocultural norms influence the interpretation and regulation of bodily sensations, highlighting the role of interoception as a mediator between biological processes and social behavior. Experimental interventions aimed at enhancing body awareness could provide practical guidance for improving self-regulation, resilience, and well-being in different populations. With solid empirical support, the proposed theoretical integration could contribute to a broader and more embodied understanding of personality and social functioning.

8. Conclusions

This paper has proposed an integrated theoretical model that links interoception and personality through the lenses of embodied cognition and Gestalt theory. The central argument suggests that personality should not be considered a static set of traits or cognitive constructs, but rather a dynamic pattern of bodily and relational regulation that reflects the way in which the individual comes into contact with the environment.

By linking neuroscientific evidence on interoception with phenomenological and relational approaches, the article highlights the mind-body unity as the foundation of human experience.

This integrated perspective offers important implications for psychology and the social sciences. Understanding personality as an embodied and relational process opens up new avenues for intervention in educational, clinical, and organizational settings. Promoting interoceptive awareness can foster the development of emotional skills, empathy, and self-regulation abilities, contributing to improved relationship quality and psychological health in social and professional contexts.

Although this contribution remains conceptual in nature, it provides a coherent and fertile theoretical framework for future empirical research on the influence of bodily processes in personality formation and social behavior.

A psychology that recognizes the body as an active organ of perception and meaning represents a decisive step toward a more holistic and ecologically valid understanding of the human being.

Data Availability Statement

This article is a theoretical and conceptual reflection based on an integrative narrative review of previously published studies. No new empirical data were collected or generated; therefore, data sharing is not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing financial or non-financial interests.

Ethical Approval Statement: This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and the Ethical Code for Research in Psychology of the Italian Association of Psychology (AIP), approved in 2015 and updated in July 2022 to comply with GDPR regulations. Since the study did not involve clinical interventions or the collection of sensitive data requiring formal approval from an ethics committee, obtaining a specific ethical approval code was not necessary. However, all procedures adhered to ethical standards to protect participants, ensuring anonymity, data confidentiality, and obtaining informed consent.

References

- Carvalho, G.B.; Damasio, A. Interoception and the origin of feelings: A new synthesis. BioEssays 2021, 43, 2000261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pessoa, L. The Entangled Brain: How Perception, Cognition, and Emotion are Woven Together; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Francesetti, G. The phenomenal field: the origin of the self and the world. Phenom. J. Int. J. Psychopathol. Neurosci. Psychother. 2024, 6, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perls, F.S.; Hefferline, R.F.; Goodman, P. Gestalt Therapy: Excitement and Growth in the Human Personality; Dell Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Foglia, L.; Wilson, R.A. Embodied cognition. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Cogn. Sci. 2013, 4, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francesetti, G. From individual symptoms to psychopathological fields: Towards a field perspective on clinical human suffering. Br. Gestalt J. 2015, 24, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robine, J.-M. Il Rivelarsi del sé nel Contatto: Studi di Psicoterapia della Gestalt; FrancoAngeli: Milan, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Spagnuolo Lobb, M. The Now-for-Next in Psychotherapy. Gestalt Therapy Evolution; Gestalt Books: Siracusa, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Seth, A.K.; Friston, K.J. Active interoceptive inference and the emotional brain. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2016, 19, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherrington, C.S. Observations on the scratch-reflex in the spinal dog. J. Physiol. 1906, 34, 1–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalsa, S.S.; Lapidus, R.C. Can interoception improve the pragmatic search for biomarkers in psychiatry? Front. Psychiatry 2016, 7, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, A.D. How do you feel? Interoception: The sense of the physiological condition of the body. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2002, 3, 655–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Critchley, H.D.; Harrison, N.A. Visceral influences on brain and behavior. Neuron 2013, 77, 624–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, R.; Murphy, J.; Bird, G. Atypical interoception as a common risk factor for psychopathology: A review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 130, 470–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garfinkel, S.N.; Critchley, H.D. Interoception, emotion and brain: New insights link internal physiology to social behaviour. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2013, 8, 231–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porges, S.W. Body Perception Questionnaire; University of Maryland, Laboratory of Developmental Assessment: College Park, MD, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Mehling, W.E.; Price, C.; Daubenmier, J.; Acree, M.; Bartmess, E.; Stewart, A. The multidimensional assessment of interoceptive awareness (MAIA). PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e48230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechara, A.; Naqvi, N. Listening to your heart: Interoceptive awareness as a gateway to feeling. Nat. Neurosci. 2004, 7, 102–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schandry, R. Heart beat perception and emotional experience. Psychophysiology 1981, 18, 483–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fumoso, M.; Elia, M.; Siliprandi, E.; Ferrara, F. Anxiety and interoceptive awareness: An experimental study. Psychology 2012, 3, 422–426. [Google Scholar]

- Kever, A.; Pollatos, O.; Vermeulen, N.; Grynberg, D. Interoceptive sensitivity facilitates both antecedent- and response-focused emotion regulation strategies. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2015, 87, 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, L.F.; Quigley, K.S.; Bliss-Moreau, E.; Aronson, K.R. Interoceptive sensitivity and self-reports of emotional experience. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 87, 684–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, B.M.; Herbert, C.; Pollatos, O. On the relationship between interoceptive awareness and alexithymia: Is interoceptive awareness related to emotional awareness? J. Pers. 2011, 79, 1149–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollatos, O.; Herbert, B.M.; Matthias, E.; Schandry, R. Heart rate response after emotional presentation is modulated by interoceptive awareness. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2007, 63, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollatos, O.; Traut-Mattausch, E.; Schroeder, H.; Schandry, R. Interoceptive awareness mediates the relationship between anxiety and the intensity of unpleasant feelings. J. Anxiety Disord. 2007, 21, 931–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vienna, S.; Zhang, J.; Scherg, M. Effects of emotional visual stimulation on temporal characteristics of interoceptive brain waves. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2000, 43, 243–254. [Google Scholar]

- Pollatos, O.; Füstös, J.; Critchley, H.D. On the generalised embodiment of pain: How interoceptive sensitivity modulates cutaneous pain perception. Pain 2012, 153, 1680–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainauli, A. Through the eyes of Gestalt therapy: The emergence of existential experience on the contact boundary. Phenom. J. Int. J. Psychopathol. Neurosci. Psychother. 2025, 7, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, N.A.; Gray, M.A.; Gianaros, P.J.; Critchley, H.D. The embodiment of emotional feelings in the brain. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 12878–12884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekman, P.; Levenson, R.W.; Friesen, W.V. Autonomic nervous system activity distinguishes among emotions. Science 1983, 221, 1208–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, R.D.; Wilhelm, F.H.; Gross, J.J. All in the mind’s eye? Anger rumination and reappraisal. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 94, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, G.E.; Weinberger, D.A.; Singer, J.A. Cardiovascular differentiation of happiness, sadness, anger, and fear following imagery and exercise. Psychosom. Med. 1981, 43, 343–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terasawa, Y.; Moriguchi, Y.; Tochizawa, S.; Umeda, S. Interoceptive sensitivity predicts sensitivity to the emotions of others. Cogn. Emot. 2014, 28, 1435–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiou, E.; Mai, S.; Fernandez, K.C.; Pollatos, O. I see neither your fear, nor your sadness – interoception in adolescents. Conscious. Cogn. 2018, 60, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chick, C.F.; Rounds, J.D.; Hill, A.B.; Anderson, A.K. My body, your emotions: Viscerosomatic modulation of facial expression discrimination. Biol. Psychol. 2019, 147, 107779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulus, M.P.; Stein, M.B. Interoception in anxiety and depression. Brain Struct. Funct. 2010, 214, 451–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaronson, S.T.; Sears, P.; Ruvuna, F.; Bunker, M.; Conway, C.R.; Dougherty, D.D.; et al. A 5-Year observational study of patients with treatment-resistant depression treated with vagus nerve stimulation or treatment as usual. Am. J. Psychiatry 2017, 174, 640–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshkevari, E.; Rieger, E.; Musiat, P.; Treasure, J. An investigation of interoceptive sensitivity in eating disorders using a heartbeat detection task and a self-report measure. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2014, 22, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlando, G. Gestalt Therapy and Panic attacks: Base Relational Model, life cycle and clinic in GTK. Phenom. J. Int. J. Psychopathol. Neurosci. Psychother. 2020, 2, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, A.D. How do you feel—now? The anterior insula and human awareness. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2009, 10, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seth, A.K.; Friston, K.J. Active interoceptive inference and the emotional brain. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2016, 371, 20160007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lommatzsch, A.; Cirasino, D.; De Fabrizio, M.; Orlando, S.; Terzi, C.; Antoncecchi, M. The Working on the emotion of anger in panic disorder: a phenomenological-existential and Gestalt psychotherapy approach. Phenom. J. Int. J. Psychopathol. Neurosci. Psychother. 2024, 6, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eysenck, H. The Biological Basis of Personality; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck, H.J.; Eysenck, S.B.G. Personality and Individual Differences: A Natural Science Approach; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Maltby, J.; Day, L.; Macaskill, A. Personality, Individual Differences and Intelligence; Pearson Education Limited: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, G.; Gilliland, K. The personality theories of H. J. Eysenck and J. A. Gray: A comparative review. Pers. Individ. Differ. 1999, 26, 583–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.L.; Kumari, V. Hans Eysenck's interface between the brain and personality: Modern evidence on the cognitive neuroscience of personality. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2016, 103, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, M.; Eves, F.F. Personality, temperament and the cardiac defense response. Pers. Individ. Differ. 1991, 12, 999–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, F.; Hirschmann, R. The influence of extraversion and neuroticism on heart rate responses to aversive visual stimuli. Pers. Individ. Differ. 1980, 1, 97–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, G.D. Personality, time of day, and arousal. Pers. Individ. Differ. 1990, 11, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, C.J.; Larsen, J.T.; Cacioppo, J.T. Neuroticism is associated with larger and more prolonged electrodermal responses to emotionally evocative pictures. Psychophysiology 2007, 44, 823–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynaud, E.; El Khoury-Malhame, M.; Rossier, J.; Blin, O.; Khalfa, S. Neuroticism modifies psychophysiological responses to fearful films. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e32413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garfinkel, S.N.; Seth, A.K.; Barrett, L.F.; Suzuki, K.; Critchley, H.D. Knowing your own heart: Distinguishing interoceptive accuracy from interoceptive awareness. Biol. Psychol. 2014, 104, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuckerman, M.; Buchsbaum, M.S.; Murphy, D.L. Sensation seeking and its biological correlates. Psychol. Bull. 1980, 88, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, M.; Hughes, S. Feeling me feeling you: Links between the dark triad and internal body awareness. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2015, 86, 308–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Critchley, H.D.; Wiens, S.; Rotshtein, P.; Öhman, A.; Dolan, R.J. Neural systems supporting interoceptive awareness. Nat. Neurosci. 2004, 7, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, B.D.; et al. Listening to your heart: How interoception shapes emotion experience and intuitive decision making. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 21, 1835–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, D.L.; Manassei, M.; van Praag, C.G.; Philippides, A.O.; Critchley, H.D.; Garfinkel, S.N. Sleep and the heart: Interoceptive differences linked to poor experiential sleep quality in anxiety and depression. Biol. Psychol. 2017, 127, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertan, D.; Hingray, C.; Burlacu, E.; Sterlé, A.; El-Hage, W. Post-traumatic stress disorder following childbirth. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallorquí-Bagué, N.; Garfinkel, S.N.; Engels, M.; Eccles, J.A.; Pailhez, G.; Bulbena, A.; Critchley, H.D. Neuroimaging and psychophysiological investigation of the link between anxiety, enhanced affective reactivity and interoception in people with joint mobility. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinbarg, R.E.; Mineka, S.; Bobova, L.; Craske, M.G.; Vrshek-Schallhorn, S.; Griffith, J.W. . & Anand, D. Testing a hierarchical model of neuroticism and its cognitive facets: Latent structure and prospective prediction of first onsets of anxiety and unipolar mood disorders during 3 years in late adolescence. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2016, 4, 805–824. [Google Scholar]

- Ferentzi, E.; Drew, R.; Tihanyi, B.T.; Köteles, F. Interoceptive accuracy and body awareness–Temporal and longitudinal associations in a non-clinical sample. Physiol. Behav. 2018, 184, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyyra, P.; Parviainen, T. Behavioral inhibition underlies the link between interoceptive sensitivity and anxiety-related temperamental traits. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalsa, S.S.; Rudrauf, D.; Feinstein, J.S.; Tranel, D. The pathways of interoceptive awareness. Nat. Neurosci. 2009, 12, 1494–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzoi, S.L.; Kessenich, J.J.; Sugrue, P.A. Gender differences in the experience of body awareness: An experiential sampling study. Sex Roles 1989, 21, 499–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabauskaitė, A.; Baranauskas, M.; Griškova-Bulanova, I. Interoception and gender: What aspects should we pay attention to? Conscious. Cogn. 2017, 48, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salonia, G. La Psicoterapia della Gestalt: Ermeneutica e Clinica; FrancoAngeli: Milan, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Capparelli, T.; Langella, C.; Giannetti, C.; Scognamiglio, R.; Messina, M. Phenomenology of Shame: a Review on Genesis and Developments. Phenom. J. Int. J. Psychopathol. Neurosci. Psychother. 2022, 4, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geniola, N.; Cini, A.; Ballotti, S.; Roti, S.; Gabriele, G.; Verardo, A. Well-being and quality of life for the psychotherapist: a research proposal. Phenom. J. Int. J. Psychopathol. Neurosci. Psychother. 2025, 7, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehling, W.E.; Wrubel, J.; Stewart, A. Body awareness training in education: Applications and outcomes. Mindfulness 2018, 9, 847–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woldt, A.L.; Toman, S.M. (Eds.) Gestalt Therapy: History, Theory, and Practice; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, L.S. Emotion–focused therapy. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. Int. J. Theory Pract. 2004, 11, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quattrini, P.; Cini, A. Theory, Practice and Technique: Self-supervision in Gestalt psychotherapy. Phenom. J. Int. J. Psychopathol. Neurosci. Psychother. 2020, 2, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, E. Mind in Life: Biology, Phenomenology, and the Sciences of Mind; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Colombetti, G. The Feeling Body: Affective Science Meets the Enactive Mind; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel, D.J. The Developing Mind: How Relationships and the Brain Interact to Shape Who We Are, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Di Sarno, A.D.; Barone, M.; De Masis, M.; Di Gennaro, R.; Fabbricino, I.; Forino, A.A.; Luceri, J.F. Validity and effectiveness of Gestalt Play Therapy: a proposal for defining a shared research protocol. Phenom. J. Int. J. Psychopathol. Neurosci. Psychother. 2025, 7, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.T.; McCrae, R.R. Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) Professional Manual; Psychological Assessment Resources: Odessa, FL, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- John, O.P.; Donahue, E.M.; Kentle, R.L. The Big Five Inventory-Versions 4a and 54; University of California, Berkeley, Institute of Personality and Social Research: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Cini, A.; Oliva, S.; Quattrini, G.P. Well - Being: a proposal research on Gestalt therapy efficacy. Phenom. J. Int. J. Psychopathol. Neurosci. Psychother. 2019, 1, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roti, S.; Berti, F.; Geniola, N.; Zajotti, S.; Calvaresi, G.; Defraia, M.; Cini, A. A Gestalt journey: how the well-being changes during a Gestalt treatment. Phenom. J. Int. J. Psychopathol. Neurosci. Psychother. 2023, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).