1. Introduction

Eating disorders (EDs) represent a complex and growing public health concern, particularly during adolescence—a developmental period marked by rapid biological, psychological, and social transformations. These changes contribute to heightened vulnerability to body image concerns and maladaptive eating behaviors (Steiner et al., 2003; Smink, van Hoeken, & Hoek, 2012). Contemporary research confirms that EDs do not arise from a single cause but result from a multifactorial interplay of biological, psychological, nutritional, and sociocultural influences (Culbert, Racine, & Klump, 2015).

The term ‘eating disorders’ encompasses psychiatric conditions such as anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN), and binge eating disorder (BED)—all characterized by persistent disturbances in eating behavior, distorted body image, and rigid attitudes toward food and weight (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). According to DSM-5 criteria, these disorders often co-occur with comorbid mental health conditions such as depression, anxiety, or obsessive-compulsive symptoms and are associated with severe physical and psychosocial consequences, including malnutrition, stunted growth, impaired social functioning, and elevated mortality risk (Fairburn & Harrison, 2003). Recent national cohort data also underscore the high comorbidity between Anorexia Nervosa and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD), with shared risk predictors and complex diagnostic trajectories (Zhu et al., 2025). Their consequences range from malnutrition and impaired growth to chronic health problems and elevated mortality (Arcelus et al., 2011).

Globally, it is estimated that 4–6% of adolescents meet diagnostic criteria for an ED during their teenage years (Volpe et al., 2016; Qian et al., 2021). However, subclinical disordered eating behaviors—including chronic dieting, binge eating, and compensatory behaviors—are significantly more prevalent, affecting up to one-third of adolescents, with higher rates among girls (Mitchison et al., 2020). In Mediterranean countries such as Cyprus, although national epidemiological data remain limited, emerging evidence shows rising levels of body dissatisfaction and unhealthy dieting behaviors, often driven by cultural ideals emphasizing thinness and physical attractiveness (Argyrides & Alexiou, 2020).

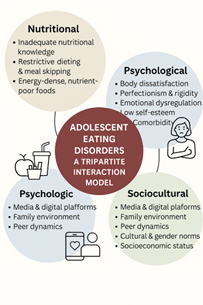

The etiology of EDs is best understood through a tripartite model that highlights the interaction of three interrelated domains:

- -

Nutritional and dietary attitudes, including restrictive eating, meal skipping, low nutritional literacy, and distorted beliefs about food and body control;

- -

Psychological vulnerabilities, such as low self-esteem, perfectionism, emotional dysregulation, and anxiety;

- -

Sociocultural pressures, including thin-ideal internalization, peer comparisons, and social media exposure.

These factors are not isolated but act synergistically. For instance, an adolescent with low self-esteem (psychological), regularly exposed to idealized body images on social media (sociocultural), and lacking basic nutritional understanding (dietary) is at significantly elevated risk for developing disordered eating patterns (Vicent et al., 2023; Rodgers et al., 2020). Protective factors—such as supportive family communication, emotional regulation skills, and media literacy—can moderate these risks (Neumark-Sztainer et al., 2006).

Recent research has also emphasized the importance of mindful eating in promoting healthier relationships with food. A cross-sectional study of Cypriot and Greek adults found that mindful eating was associated with improved sleep, more stable BMI, and better overall health outcomes (Andreou et al., 2024). While primarily studied in adults, these findings support the integration of mindfulness strategies into adolescent nutrition education to promote psychological regulation and reduce the risk of disordered eating.

While adolescence is undoubtedly a time of vulnerability, it also presents a crucial window for early prevention and intervention. Schools, as central institutions in adolescent life, are uniquely positioned to influence health-related attitudes and behaviors. Studies have shown that school-based programs incorporating nutrition education, body image resilience, and social-emotional learning can significantly reduce ED risk factors (Yager, Diedrichs, & Ricciardelli, 2013). Moreover, multi-stakeholder collaboration involving educators, mental health professionals, and families enhances the reach and effectiveness of early prevention.

Despite progress in understanding the etiology of EDs, several critical gaps remain. The majority of existing literature is based on Western populations, leaving Mediterranean countries like Cyprus underrepresented in both epidemiological and intervention research. Cultural factors—including traditional gender roles, collectivist family structures, and unique beauty norms—may shape how ED risk factors manifest in these settings (Argyrides & Kkeli, 2015). Furthermore, many studies examine risk factors in isolation, without accounting for the cumulative or interacting effects across domains. There is a need for integrative models that reflect the full complexity of adolescent development and social context.

This narrative review aims to synthesize current evidence on the nutritional, psychological, and sociocultural determinants of eating disorders in adolescents. By adopting an integrative tripartite framework, the review seeks to:

- 1.

Clarify how these risk domains interact and compound one another, particularly during adolescence;

- 2.

Highlight the preventive potential of school-based interventions and educator engagement in reducing ED vulnerability.

The innovative contribution of this review lies in its multi-domain synthesis with a specific focus on Mediterranean contexts and the preventive role of education systems—a dimension that remains underexplored in current literature.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Aim

This study was conducted as a narrative literature review, aiming to synthesize contemporary research on the nutritional, psychological, and sociocultural determinants of eating disorders (EDs) in adolescents. The narrative review approach was chosen to enable a broad, integrative perspective, capturing multidisciplinary findings not always addressed in systematic reviews.

2.2. Search Strategy

A systematic search was conducted across four major academic databases: PubMed, Scopus, PsycINFO, and Google Scholar. The search covered the period January 2000 to March 2025, with literature published in English or Greek.

A structured search strategy was applied using combinations of predefined keywords and Boolean operators. The core terms included: “eating disorders”, “adolescents”, “body image”, “nutritional attitudes”, “psychological risk factors”, “sociocultural influences”, and “school-based prevention”.

Reference lists of included studies were also screened for additional relevant sources.

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion Criteria

Studies were considered eligible if they:

- -

Focused on adolescents aged 12–19 years;

- -

Examined at least one of the three domains: nutritional, psychological, or sociocultural factors in EDs;

- -

Were peer-reviewed articles published in English or Greek;

- -

Were published between 2010 and 2025.

Exclusion Criteria

Studies were excluded if they:

- -

Focused solely on adults or on clinical treatment of EDs;

- -

Were case reports, editorials, or opinion pieces;

- -

Were not available in full text.

2.4. Screening and Selection Process

The initial database search yielded 230 articles. After removing duplicates, titles and abstracts were screened for relevance. A total of 58 studies met the inclusion criteria and were selected for full-text review. Studies were critically examined for relevance, methodological rigor, and thematic contribution.

Data were synthesized narratively, emphasizing the interactions between risk factors and identifying preventive strategies in school and community contexts.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

This study is based entirely on previously published, publicly available literature and did not involve human participants or animal subjects. Therefore, no ethical approval was required. All referenced studies were assumed to have obtained ethical approval from their respective institutions.

2.6. Use of Generative AI Tools

During manuscript preparation, the authors made limited use of ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-4) for language clarity, grammar enhancement, and reference formatting. All generated outputs were critically reviewed, edited, and approved by the authors. The AI tool was not used to generate scientific content, data, or interpretation.

2.7. Limitations of the Methodology

As a narrative review, this study does not follow the PRISMA checklist or conduct a formal quality appraisal. Potential limitations include:

- -

Reduced replicability compared to systematic reviews;

- -

Selection bias due to non-standardized data extraction;

- -

Language bias due to exclusion of non-English/Greek publications.

Despite these limitations, the narrative approach enabled a comprehensive synthesis across disciplines and geographies, with particular relevance to Mediterranean populations—a group often underrepresented in ED prevention literature.

3. Results

This section presents the synthesized findings of the narrative review, organized into three key domains: nutritional attitudes and practices, psychological and behavioral factors, and sociocultural influences. These domains interact and overlap in shaping the onset, maintenance, and impact of eating disorders (EDs) in adolescence. Tables and structured analysis offer a cohesive representation of these interactions, as well as symptomatology and consequences. Each sub-section also highlights relevant implications for school-based prevention.

3.1. Nutritional Attitudes and Practices in Adolescence

Adolescence is a pivotal period for establishing eating habits, yet findings from multiple studies reveal widespread unhealthy dietary practices, poor nutritional literacy, and distorted beliefs around food and body weight. These behaviors not only function as direct risk factors for eating disorders (EDs) but also mediate broader psychological and sociocultural vulnerabilities (Contento, 2011; Levine & Smolak, 2018).

3.1.1. Inadequate Nutritional Knowledge and Misinformation

Numerous studies confirm that adolescents lack fundamental knowledge of nutrition guidelines, particularly regarding macronutrients and balanced meals. Misunderstandings—such as labeling entire food groups like fats or carbs as "bad"—contribute to restrictive and unbalanced diets (O’Dea, 2005; Neumark-Sztainer et al., 2006). Social media has become a major vector for nutritional misinformation. Adolescents frequently engage with content promoting detoxes, fasting regimens, or elimination diets lacking scientific grounding. This exposure is associated with poor diet quality and increased body dissatisfaction, particularly among girls (Levine & Smolak, 2018; Fardouly & Vartanian, 2016; Glaser et al., 2024).

3.1.2. Restrictive Dieting and Skipping Meals

Evidence consistently shows that restrictive dieting during adolescence is a key predictor of disordered eating. Behaviors such as calorie counting, meal skipping, and mono-diets (e.g., only juice or only protein) are linked to the onset of binge–restrict cycles (Stice & Shaw, 2002; Stice et al., 2017). Adolescents who skip breakfast are especially vulnerable, with studies linking this behavior to poor academic performance, irritability, and compensatory overeating later in the day (Rampersaud et al., 2005; Tanofsky-Kraff et al., 2005). These behaviors are also influenced by peer norms and appearance concerns, particularly in weight-conscious environments.

3.1.3. Consumption of Energy-Dense, Nutrient-Poor Foods

Paradoxically, while some adolescents restrict intake, others engage in excessive consumption of high-calorie, low-nutrient foods. Convenience, low cost, and marketing of such products contribute to diets rich in sugary drinks, processed snacks, and fast food (Story, Neumark-Sztainer & French, 2002; Harris et al., 2009). These behaviors may stem from emotional triggers or be part of peer-driven eating, reinforcing cycles of guilt, restriction, and compensatory eating (Loth et al., 2014).

3.1.4. Determinants of Food Choice

Food choices are not made in isolation. Studies show that adolescents are heavily influenced by taste preferences, peer behaviors, media advertising, and price (Steptoe, Pollard & Wardle, 1995; Salvy et al., 2012). Peer groups may reinforce poor eating behaviors, normalize restrictive trends, or encourage high-volume snacking, depending on group norms.

3.1.5. Cultural and Regional Trends

Research in Mediterranean countries, including Cyprus, reveals a shift away from traditional dietary practices toward more Westernized patterns. Although the Mediterranean diet is associated with positive health outcomes, studies show increasing adolescent reliance on fast food, rising body dissatisfaction, and dieting culture (Hebestreit et al., 2017; Argyrides & Alexandrou, 2020). This nutritional Westernization is often accompanied by cultural tensions, especially where food remains a symbol of family or identity but is also scrutinized through appearance-focused lenses.

3.1.6. Intersections with Psychological and Sociocultural Factors

Nutritional practices are closely tied to psychological constructs such as perfectionism, low self-esteem, and emotional regulation difficulties (Vicent et al., 2023; Bills et al., 2023). Adolescents who restrict food often exhibit cognitive rigidity and are more likely to internalize thin ideals, especially when exposed to curated social media content (Rodgers et al., 2020; Bonfanti et al., 2025).

3.2. Psychological and Behavioral Factors in Adolescent Eating Disorders

Psychological and behavioral vulnerabilities play a central role in both the onset and maintenance of eating disorders (EDs) in adolescence. While disordered nutritional practices may be the most visible indicators, internal psychological traits such as low self-esteem, perfectionism, and emotional dysregulation—often in combination with external pressures—create a complex risk environment. This section explores key psychological and behavioral mechanisms associated with EDs, based on a synthesis of multidisciplinary research.

3.2.1. Body Dissatisfaction and Internalization of Thin Ideals

Body dissatisfaction is one of the most consistently documented predictors of eating disorders. Adolescents often internalize socially constructed ideals of thinness or muscularity, which become benchmarks for self-worth (Stice & Shaw, 2002; Neumark-Sztainer et al., 2006). These ideals are perpetuated by media exposure and peer environments, fueling negative body image, especially among girls. Research indicates that adolescents with high levels of internalization of thin ideals are significantly more likely to engage in dieting, body monitoring, and disordered eating (Levine & Smolak, 2018; Rodgers et al., 2016).

3.2.2. Perfectionism and Cognitive Rigidity

Maladaptive perfectionism, defined by excessively high self-imposed standards and inflexible thinking, is strongly associated with the development of EDs (Shafran et al., 2002). Adolescents with perfectionist tendencies often adopt rigid dietary rules and experience intense guilt following minor deviations. These traits have been linked with chronic restriction, binge–purge cycles, and obsessive focus on body control (Vicent et al., 2023). Cognitive rigidity further exacerbates vulnerability by reducing adaptability and reinforcing black-and-white thinking about food and body image.

3.2.3. Emotional Dysregulation and Stress

Difficulties in emotional recognition, regulation, and expression are core psychological features linked to ED behaviors. Adolescents with emotional dysregulation are more likely to use food as a maladaptive coping mechanism—either through restriction (as a means of control) or binge eating (as a response to distress) (Whiteside et al., 2007; Mason et al., 2016). Stressful events, particularly those involving appearance-related teasing or academic pressure, have been shown to amplify these behaviors (Bacopoulou et al., 2018; Mallorquí-Bagué et al., 2018).

3.2.4. Low Self-Esteem and Identity Development

Low self-esteem is both a risk and maintenance factor for disordered eating. When adolescents link their self-worth to physical appearance, body dissatisfaction can erode identity stability and fuel maladaptive behaviors (Cella et al., 2020). During this developmental stage, issues related to identity formation are critical. EDs may become a way to assert control, gain recognition, or align with peer expectations. Interventions targeting positive identity development and self-acceptance have been shown to reduce risk (Harter, 2012).

3.2.5. Comorbidity with Other Psychological Disorders

EDs frequently co-occur with other psychiatric conditions, including anxiety disorders, depression, and obsessive-compulsive disorder (Hudson et al., 2007; Santomauro et al., 2021). In some cases, ED behaviors may emerge as coping strategies: e.g., restrictive eating may offer a sense of control in anxiety, while binge eating may be a temporary escape from depressive affect (Kaye et al., 2004; Udo & Grilo, 2019). This overlap underscores the need for integrative diagnostic and therapeutic approaches.

3.2.6. Behavioral Manifestations and Risk Patterns

Observable behaviors such as secretive eating, food hoarding, excessive exercise, and avoidance of meals may serve as early indicators of ED risk (Levine & Smolak, 2018). These subclinical behaviors, while not always pathologic in isolation, often escalate when combined with emotional vulnerability and social pressures. Repeated dieting and emotional eating in adolescence are particularly predictive of transition to full-threshold EDs (Stice et al., 2017).

3.2.7. Emotional Eating and Loss of Control

Emotional eating—defined as eating in response to negative emotions rather than hunger—has been strongly linked with binge eating tendencies. Adolescents experiencing sadness, loneliness, or anxiety may turn to calorie-dense comfort foods as an emotional regulator, often followed by guilt and shame (Tanofsky-Kraff et al., 2005; Zhu, 2025). This creates a maladaptive cycle that reinforces poor emotional coping and ED behaviors.

3.2.8. Fear of Fatness and Weight-Related Anxiety

Fear of weight gain is a hallmark of anorexia nervosa but also pervades subclinical eating concerns. Adolescents frequently express anxiety around “getting fat,” leading to restriction, purging, or over-exercising. Studies have found that weight-related fears often emerge as early as 10–12 years old and are intensified by social and media influences (Levine & Smolak, 2018).

3.2.9. Rumination and Preoccupation with Appearance

Cognitive rumination—repetitive focus on appearance-related concerns—has been found to predict body dissatisfaction and ED symptoms. Adolescents may spend excessive time mirror-checking, comparing with peers, or rehearsing perceived flaws. This mental preoccupation detracts from academic and social functioning and deepens vulnerability (Rodgers et al., 2016; Bonfanti et al., 2025).

3.2.10. Social Withdrawal and Interpersonal Difficulties

Social isolation is both a consequence and a risk factor for EDs. Adolescents may withdraw from social eating contexts, avoid peer interactions, or experience strained relationships due to preoccupation with food and body image. This loss of social support increases psychological vulnerability and may perpetuate the disorder (Lavender et al., 2015; Griffiths et al., 2015).

3.2.11. Guilt, Shame, and Moralization of Food

EDs often involve distorted beliefs around food as morally “good” or “bad.” Adolescents may experience intense guilt following food consumption or equate eating with moral failure. This emotional reaction reinforces cycles of restriction, bingeing, and purging, particularly in those with perfectionistic traits (Mallorquí-Bagué et al., 2018; Stice et al., 2017).

3.2.12. Self-Objectification and Appearance Monitoring

Self-objectification—the internalization of the observer’s perspective—leads adolescents to monitor their appearance chronically and devalue non-appearance traits. This can be particularly harmful for girls and gender-diverse youth, who face heightened societal scrutiny. Studies link self-objectification with greater body shame and ED symptoms (Fardouly et al., 2018; Perloff, 2014).

3.2.13. Appearance-Based Peer Comparison

Peer environments are key developmental spaces where adolescents form self-concept. Comparing appearance with friends or classmates can escalate body dissatisfaction, particularly in competitive or appearance-focused groups. This comparison process is magnified by social media, where curated images foster unrealistic standards (Fardouly & Vartanian, 2016; Holland & Tiggemann, 2016).

3.2.14. Gender Differences and Expression of Psychological Risk

ED symptoms may differ by gender due to societal expectations. While girls tend to internalize thin ideals, boys may pursue muscularity, leading to muscle dysmorphia, excessive exercise, and supplement misuse (Ricciardelli & McCabe, 2004; Mitchison & Mond, 2015). These differing expressions underscore the importance of gender-sensitive prevention.

3.2.15. Interaction with Sociocultural and Nutritional Risk Factors

Psychological vulnerabilities are rarely isolated. Perfectionism may intensify the impact of media ideals; emotional dysregulation may result in binge eating when exposed to calorie-dense foods. Family dieting culture can reinforce existing insecurities. These intersections highlight the need for integrated, multi-domain prevention efforts (Rodgers et al., 2016; Tanofsky-Kraff et al., 2005).

3.3. Sociocultural Influences on Adolescent Eating Disorders

Sociocultural influences serve as critical external determinants that interact with nutritional and psychological vulnerabilities to shape the risk profile for eating disorders (EDs) during adolescence. This life stage is particularly sensitive to societal norms around body image, belonging, and appearance. Cultural ideals, family modeling, peer dynamics, socioeconomic status, and globalization act not only as individual factors but as interconnected forces that can amplify or mitigate ED risks. The following subsections examine these influences in detail.

3.3.1. Media and Digital Platforms

Media and social networking platforms are among the most powerful sociocultural influences on adolescents’ body image. Adolescents are frequently exposed to unrealistic beauty standards through traditional media (television, magazines) and, increasingly, digital environments. Research has consistently shown that exposure to thin and fit ideals contributes to body dissatisfaction and increased risk of disordered eating behaviors (Levine & Smolak, 2018; Perloff, 2014; Fardouly & Vartanian, 2016).

Recent studies highlight the dangers of active engagement with social media platforms—such as photo editing, posting selfies, or following fitness influencers—which reinforces appearance-based self-worth and body surveillance (Holland & Tiggemann, 2016; Fardouly et al., 2018; Glaser et al., 2024). Algorithm-driven content curation further creates feedback loops that intensify exposure to idealized body images, magnifying the impact on vulnerable adolescents (Bonfanti et al., 2025).

3.3.2. Family Environment

Family dynamics exert a profound influence on adolescents’ eating behaviors, body image, and self-perception. Parental modeling of restrictive dieting, body dissatisfaction, or weight-based talk can normalize maladaptive attitudes in children and adolescents (Rodgers & Chabrol, 2009; Neumark-Sztainer et al., 2008). Studies show that adolescents whose parents emphasize appearance or practice restrictive eating themselves are at higher risk for internalizing those norms.

Conversely, positive family environments characterized by body acceptance, open communication, and balanced nutrition can function as protective buffers. However, family risk is not limited to parents—sibling teasing and comparisons have also been found to increase vulnerability to ED symptoms (McHale et al., 2001). These findings reinforce the bidirectional nature of family influence, which can either mitigate or magnify sociocultural pressures.

3.3.3. Peer Dynamics and School Culture

Peers significantly influence adolescents’ self-concept, dietary practices, and body image. Negative peer experiences such as teasing, bullying, and appearance-based comparisons have been consistently associated with body dissatisfaction and eating pathology (Eisenberg et al., 2003; Lie et al., 2021). Competitive dieting, group dieting challenges, and exclusion based on appearance are particularly harmful.

School environments can either reinforce harmful norms or act as platforms for change. While weight stigma and lack of inclusive representation in curricula can heighten risk, schools also hold the potential to reduce ED vulnerability through targeted health education programs, anti-bullying policies, and body diversity initiatives (Yager & O’Dea, 2010). Peer-led prevention and inclusive messaging in schools have shown promise in reducing body dissatisfaction and promoting healthier norms.

3.3.4. Cultural Norms and Gender Expectations

Cultural constructions of gender and beauty expectations shape the way EDs manifest. In Western cultures, thinness is closely linked with female attractiveness, while leanness and muscularity are idealized in males (Ricciardelli & McCabe, 2004). These ideals drive differing behaviors: girls may engage in restrictive dieting or purging, while boys may turn to compulsive exercise and muscle-enhancing substances (Mitchison & Mond, 2015).

Cross-cultural research shows that collectivist cultures may buffer some ED risks due to stronger communal identity, but they may also reinforce conformity pressures, particularly around gender roles and physical appearance (Swami, 2015). In Mediterranean contexts such as Cyprus and Greece, tension arises between traditional eating patterns and Westernized ideals, leading to increased dietary restriction and body dissatisfaction among youth (Argyrides & Kkeli, 2015).

3.3.5. Socioeconomic Status and Inequalities

Socioeconomic status (SES) moderates exposure to ED risk factors in complex ways. Adolescents from higher SES backgrounds may face greater pressure to achieve body ideals through dieting, while those from lower SES groups often experience food insecurity, limited access to healthy foods, and increased stress—factors that elevate the risk for binge eating and body dissatisfaction (Scharff et al., 2010).

Importantly, socioeconomic disparities also extend to access to preventive interventions, mental health care, and nutritional support, creating unequal opportunities for early detection and treatment. These inequalities suggest that public health policies must address structural determinants to effectively reduce ED prevalence and consequences in diverse populations.

3.3.6. The Amplifying Role of Globalization

Globalization has intensified exposure to homogenized beauty standards, often promoting a Westernized thin ideal while marginalizing diverse body types and traditional health practices (Grabe, Ward & Hyde, 2008). Through international media and social networks, adolescents in various cultural contexts increasingly adopt appearance norms that may conflict with their cultural or familial values.

This cultural dissonance is particularly evident in Mediterranean countries where traditional dietary and body ideals—once focused on moderation and functionality—are being displaced by global diet trends and aesthetics (Fardouly et al., 2018; Bonfanti et al., 2025). Simultaneously, the global wellness industry markets restrictive practices under the guise of health, normalizing behaviors that may precede eating disorders. These shifts highlight the need for culturally tailored prevention efforts that resist one-size-fits-all solutions.

3.3.7. Intersections with Psychological and Nutritional Risk Factors

Sociocultural influences rarely act in isolation. Instead, they interact dynamically with psychological traits and nutritional habits to shape ED trajectories. For example:

Adolescents with perfectionism may more easily internalize media ideals and adopt extreme diets.

Those with emotional dysregulation may turn to binge eating when exposed to appearance-based bullying or social exclusion.

Family patterns of dieting or appearance commentary can reinforce existing body image concerns and restrictive eating.

These intersections support the tripartite model of ED etiology, whereby sociocultural, psychological, and nutritional factors operate simultaneously to increase vulnerability or resilience (Rodgers et al., 2016; Tanofsky-Kraff et al., 2005).

The multifactorial etiology of adolescent eating disorders emerges through the complex interaction of nutritional habits, psychological traits, and sociocultural pressures.

Table 1 below synthesizes these interconnected domains, presenting representative risk factors, concrete behavioral examples, and key references. This tripartite model illustrates how various influences operate both independently and in concert to shape adolescent vulnerability to disordered eating.

3.4. Symptoms and Consequences of Eating Disorders

Adolescent eating disorders (EDs) present with a wide spectrum of physical, psychological, and social manifestations. These conditions, including anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN), and binge eating disorder (BED), as well as subclinical disordered eating behaviors, emerge from the complex interplay of nutritional, psychological, and sociocultural vulnerabilities previously discussed. Understanding the symptomatic profile and its consequences is essential for early detection, prevention, and intervention.

3.4.1. Physiological and Psychological Symptoms

Eating disorders in adolescence typically involve a combination of behavioral disturbances and internal psychological struggles. Common behavioral symptoms include restrictive dieting, binge eating episodes, purging behaviors (such as vomiting or laxative misuse), and excessive exercise, often driven by weight and shape concerns (American Psychiatric Association, 2013, 2022; WHO, 2021; Machado et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2025). Physiologically, these behaviors lead to observable signs such as significant weight loss, chronic fatigue, gastrointestinal distress, and in female adolescents, amenorrhea.

Psychological symptoms frequently include persistent body dissatisfaction, distorted body image, and obsessive preoccupation with food and body weight (Fairburn & Harrison, 2003; Treasure, Duarte & Schmidt, 2020). These are commonly accompanied by elevated levels of anxiety, depression, low self-esteem, and perfectionism (Jacobi et al., 2004; Culbert et al., 2015). In many cases, the internal nature of these experiences leads to delayed recognition, as distress may not be outwardly visible until behaviors escalate.

3.4.2. Disorder-Specific Symptomatology

While EDs share common features, each diagnosis presents with a distinctive clinical picture. Anorexia nervosa is marked by severe restriction of energy intake, intense fear of weight gain, and a distorted body image, often accompanied by ritualized eating and denial of illness. Bulimia nervosa involves recurrent binge–purge episodes, typically followed by feelings of guilt and compensatory behaviors such as vomiting or excessive exercise. Binge eating disorder is characterized by episodes of uncontrollable eating in the absence of purging, leading to feelings of loss of control and marked distress. Although these disorders vary in presentation, they are unified by underlying body image disturbances and maladaptive coping mechanisms.

Table 2 summarizes these key distinctions and their associated consequences in adolescence.

3.4.3. Short- and Long-Term Health Consequences

Eating disorders can have profound short- and long-term effects on adolescent health. In the short term, malnutrition, dehydration, and electrolyte imbalances are common and may lead to immune dysfunction and compromised growth. In cases of AN, cardiovascular complications such as bradycardia, hypotension, and arrhythmias are frequently observed (Westmoreland, Krantz & Mehler, 2016). Long-term consequences can be equally severe, including reduced bone density, delayed puberty, fertility issues, and gastrointestinal dysfunction. Notably, EDs are associated with elevated mortality, particularly in AN, where death may result from both medical complications and suicide (Arcelus et al., 2011).

In addition to physiological impacts, EDs can impair cognitive functioning. Adolescents may experience difficulties with concentration, memory, and executive function, often linked to malnutrition and psychological distress (Golden et al., 2003; Golden et al., 2016; Kothari et al., 2013). These deficits can affect academic performance and developmental trajectories, compounding the disorder’s overall burden.

3.4.4. Social and Educational Consequences

The consequences of eating disorders extend beyond health, significantly affecting adolescents’ social functioning and educational outcomes. Social withdrawal is common, often driven by anxiety around food, appearance, or perceived judgment. Adolescents with EDs may avoid social events involving meals, withdraw from peer interactions, and experience strained family relationships (Lavender et al., 2017). Within school environments, disordered eating behaviors can lead to reduced energy, diminished concentration, and motivational decline, resulting in academic underachievement and increased absenteeism. Body-related bullying or appearance-based peer victimization further intensifies these effects and can act as both a trigger and a consequence of ED symptoms (Eisenberg et al., 2003; Griffiths et al., 2015; Lie et al., 2021).

3.4.5. Tripartite Interaction in Symptom Development

The manifestation and progression of ED symptoms are best understood through the tripartite interaction of nutritional, psychological, and sociocultural factors. For example, restrictive eating behaviors (nutritional) often emerge in adolescents with perfectionistic tendencies and low self-esteem (psychological), particularly when exposed to thin-ideal imagery on social media or in peer environments (sociocultural). Similarly, binge eating episodes may be triggered by emotional dysregulation in the context of a family environment that models poor dietary behaviors and lacks emotional support (Tanofsky-Kraff et al., 2005; Zhu, 2025).

This integrative perspective affirms that no single factor is sufficient to explain the development of eating disorders. Instead, these conditions arise from the convergence of interrelated domains that collectively shape the adolescent experience. Effective prevention and intervention must therefore adopt a holistic approach, addressing the full spectrum of influences that contribute to symptom development and maintenance.

3.5. The Role of Educators and Schools in Prevention and Management of Eating Disorders

3.5.1. The Pedagogical Role of Teachers

Teachers are uniquely positioned as frontline observers of adolescent behavior and can play a crucial role in the early identification and support of students at risk of eating disorders (EDs). Research indicates that educators are often the first adults outside the family to notice behavioral and physical changes, such as weight fluctuations, avoidance of school meals, and declining academic engagement (Yager & O’Dea, 2005). However, many educators report feeling ill-equipped to address these issues, underscoring the need for structured professional development and institutional referral pathways (O’Dea & Abraham, 2001).

Educators should adhere to a schools-appropriate scope of practice. This includes observing and documenting concerns without assuming a diagnostic role, initiating weight-neutral and supportive conversations, and referring to school health services following safeguarding protocols (Neumark-Sztainer et al., 2008). Teachers should refrain from providing dietary advice or engaging in student weight monitoring. Within the classroom, inclusive practices that avoid body shaming, discourage peer teasing, and integrate critical discussions about media and health can reduce risk exposure. Subjects such as Health Education, Home Economics, and Biology provide cross-curricular opportunities to embed these practices (Yager & O’Dea, 2010; Neumark-Sztainer, 2005).

3.5.2. School-Based Health Education Programs

School settings provide a structured and equitable environment for primary prevention of EDs. Educational programs that use interactive methods—such as peer discussions, role-play, and critical media literacy—are more effective than didactic information delivery. They build body satisfaction, emotional resilience, and nutritional literacy (Levine & Smolak, 2010). Programs such as ‘Media Smart’ in Australia and ‘The Body Project’ in the U.S. have demonstrated measurable reductions in body dissatisfaction and thin-ideal internalization (Stice et al., 2009).

In Cyprus, the national Health Education curriculum already incorporates modules on nutrition, self-esteem, and media analysis. These topics are reinforced across disciplines, supporting a holistic approach to adolescent wellbeing. Sustainable prevention is supported by a whole-school ethos that includes anti-bullying policies, diverse representations of body image in school materials, and training for all staff members. When prevention is embedded into school culture, its reach and impact are magnified.

4. Discussion

This narrative review consolidates evidence across nutritional, psychological, and sociocultural domains to highlight their dynamic convergence in elevating adolescent vulnerability to eating disorders (EDs). Rather than acting in isolation, these factors interact in complex ways—such that psychological traits like perfectionism and emotional dysregulation are exacerbated by media-driven beauty ideals, peer norms, and inconsistent nutritional messaging. This interplay affirms that EDs are not reducible to personal choice or food behaviors alone, but are instead embedded within broader psychosocial and cultural ecosystems.

The tripartite framework applied in this review draws on sociocultural, ecological, and cognitive-behavioral theories, reinforcing the view that adolescent EDs reflect contextual, interpersonal, and developmental challenges. Previous research often analyzed these domains separately; however, this review synthesizes them into an integrated model that better explains the persistence and escalation of disordered eating during adolescence.

Findings further support that effective school-based prevention requires more than traditional nutrition education. Programs like Media Smart and The Body Project show that participatory, psychologically informed interventions—focusing on emotional regulation, critical media literacy, and self-acceptance—are more effective in reducing risk behaviors. Within culturally specific settings such as Cyprus, where global beauty norms challenge traditional values, these approaches must be context-sensitive and inclusive.

Schools are uniquely positioned to act as health-promoting environments. Educators often observe early behavioral signs and can offer support through structured, weight-neutral conversations and timely referrals. However, this potential is constrained by inadequate teacher training, stigma, and inconsistent access to psychological services. A whole-school approach—including curriculum integration, anti-bullying policies, and partnerships with families and health professionals—is essential to support adolescent wellbeing sustainably.

These findings also align with the central hypothesis: that EDs in adolescence cannot be addressed through isolated strategies. Instead, they require holistic interventions that consider emotional development, identity formation, digital engagement, and cultural context. For example, restrictive dieting commonly co-occurs with perfectionism and emotional dysregulation, particularly when adolescents are exposed to unrealistic social media imagery.

Despite the strengths of this synthesis, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, as a narrative review, the study is subject to selection bias and lacks the methodological rigor of systematic reviews. Second, many included studies were cross-sectional, limiting causal inferences. Third, Mediterranean contexts like Cyprus remain underrepresented in the literature, despite unique sociocultural pressures that may alter ED trajectories. Fourth, newer risk phenomena—such as orthorexia, algorithm-influenced body dysmorphia, and wellness culture—remain underexplored. Lastly, while the proposed tripartite model offers a robust theoretical lens, further empirical testing across diverse populations is needed.

Future research should prioritize longitudinal and mixed-method designs that trace the evolution of ED risk across time and culture. Special attention should be given to digital ecosystems, family dynamics, and emerging forms of disordered eating. Collaborative, interdisciplinary studies involving educators, health professionals, adolescents, and parents will be key to developing culturally relevant, sustainable interventions.

Ultimately, this review strengthens the case for a systemic, multidimensional approach to adolescent ED prevention—one that transcends diet modification and invests in emotional resilience, social support, and critical awareness of societal pressures.

5. Conclusions

Adolescent eating disorders arise from a complex interplay of nutritional, psychological, and sociocultural factors. This review highlights the need for integrative, school-based prevention strategies that extend beyond food education to address emotional resilience, media literacy, and identity development. Schools, families, and communities must collaborate to detect early signs and promote positive body image in culturally responsive ways. Holistic, theory-informed approaches are essential to mitigate the long-term consequences of EDs and support adolescent wellbeing.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, [C.K., E.A]; methodology, [C.K., E.A]; formal analysis, [C.K., E.A]; writing—original draft preparation, [C.K., E.A]; writing—review and editing, [E.C., C.P.]; supervision, [E.A.]. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were not required for this study as it is a narrative review of previously published literature and did not involve any direct research with human participants or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. This study did not involve human subjects.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. All data supporting the findings are available from the cited, peer-reviewed sources.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the University of Nicosia’s Department of Life Sciences for academic support throughout this project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Abbreviation |

Meaning |

| ED(s) |

Eating Disorder(s) |

| AN |

Anorexia Nervosa |

| BN |

Bulimia Nervosa |

| BED |

Binge Eating Disorder |

| SES |

Socioeconomic status |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

| APA |

American Psychiatric Association |

| DSM-5 |

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition |

| BMI |

Body Mass Index |

| CBT |

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy |

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Washington, DC, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreou, E; Mouski, C; Georgaki, E; et al. Mindful Eating, BMI, Sleep, and Vitamin D: A Cross-Sectional Study of Cypriot and Greek Adults. Nutrients 2024, 16(24), 4308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyrides, M.; Alexiou, E. Risk and protective factors of disordered eating in adolescents based on gender and body mass index. The European Journal of Counselling Psychology 2020, 8(1), 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyrides, M.; Sivitanides, M.; Alexandrou, E. ‘Body image, appearance schemas, and disordered eating behaviors in Cypriot university students: The role of internalization and appearance investment’. The European Journal of Counselling Psychology 2020, 8(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyrides, M.; Kkeli, N. Validation of the factor structure of the Greek adaptation of the Situational Inventory of Body-Image Dysphoria-Short Form (SIBID-S). Eating and weight disorders: EWD 2015, 20(4), 491–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacopoulou, F.; Vlahos, A. P.; Chrousos, G. P.; Darviri, C. ‘Caregivers’ psychological profile and their views on adolescents’ stress’. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology 2018, 31(2), 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakalar, J.L.; Shank, L.M.; Vannucci, A.; Radin, R.M.; Tanofsky-Kraff, M. ‘Recent advances in developmental and risk factor research on eating disorders’. Current Psychiatry Reports 2015, 17(6), 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicent, M.; Gonzálvez, C.; Quiles, M. J.; Sánchez-Meca, J. ‘Perfectionism and binge eating association: A systematic review and meta-analysis’. Journal of Eating Disorders 2023, 11(1), 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bills, E.; Greene, D.; Stackpole, R.; Egan, S. J. ‘Perfectionism and eating disorders in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis’. Appetite 2023, 187, 106586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfanti, R.C.; Melchiori, F.; Teti, A.; Albano, G.; Raffard, S.; Rodgers, R.; Lo Coco, G. ‘The association between social comparison in social media, body image concerns and eating disorder symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis’. Body Image 2025, 47, 103587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brytek-Matera, A. ‘Orthorexia nervosa – an eating disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder or disturbed eating habit?’. Archives of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy. 2012, 14, pp. 55–60. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/266008463_Orthorexia_nervosa_-_An_eating_disorder_obsessive-compulsive_disorder_or_disturbed_eating_habit (accessed on 29 March 2024).

- Cella, S.; Iannaccone, M.; Cotrufo, P. ‘Does body shame mediate the relationship between parental bonding, self-esteem, maladaptive perfectionism, body mass index and eating disorders? A structural equation model’. In Eating and Weight Disorders – Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity; 2020; Volume 25, pp. 667–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contento, I. R. Nutrition education: Linking research, theory, and practice, 2nd edn; Jones & Bartlett Learning: Sudbury, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Culbert, K. M.; Racine, S. E.; Klump, K. L. Research Review: What we have learned about the causes of eating disorders - a synthesis of sociocultural, psychological, and biological research. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines 2015, 56(11), 1141–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahill, L. M.; Morrison, N. M. V.; Mannan, H.; Mitchison, D.; Touyz, S.; Bussey, K.; Hay, P. ‘Exploring associations between positive and negative parental comments about adolescents’ bodies and eating and eating problems: A community study’. Journal of Eating Disorders 2022, 10, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, M. E.; Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Story, M. ‘Associations of weight-based teasing and emotional well-being among adolescents’. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 2003, 157(8), 733–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fardouly, J.; Vartanian, L. R. ‘Social media and body image concerns: Current research and future directions’. Current Opinion in Psychology 2016, 9, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fardouly, J.; Willburger, B.; Vartanian, L. R. ‘Instagram use and young women’s body image concerns and self-objectification: Testing mediational pathways’. New Media & Society 2018, 20(4), 1380–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, H.C.; Jansma, S.R.; Scholten, H. ‘A diary study investigating the differential impacts of Instagram content on youths’ body image’. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 2024, 11, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J. L.; Pomeranz, J. L.; Lobstein, T.; Brownell, K. D. ‘A crisis in the marketplace: How food marketing contributes to childhood obesity and what can be done’. Annual Review of Public Health 2009, 30, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, T. B.; Heron, K. E.; Braitman, A. L.; Lewis, R. J. ‘A daily diary study of perceived social isolation, dietary restraint, and negative affect in binge eating’. Appetite 2016, 97, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, L. A.; Veidebaum, T.; Pigeot, I. ‘Dietary patterns of European children and their parents in association with family food environment: Results from the I.Family Study’. Nutrients 2017, 9(2), 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, G.; Tiggemann, M. ‘A systematic review of the impact of the use of social networking sites on body image and disordered eating outcomes’. Body Image 2016, 17, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, J. I.; Hiripi, E.; Pope, H. G.; Kessler, R. C. ‘The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication’. Biological Psychiatry 2007, 61(3), 348–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobi, C.; Hayward, C.; de Zwaan, M.; Kraemer, H. C.; Agras, W. S. Coming to terms with risk factors for eating disorders: Application of risk terminology and suggestions for a general taxonomy. Psychological bulletin 2004, 130(1), 19–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaye, W. H.; Bulik, C. M.; Thornton, L.; Barbarich, N.; Masters, K. ‘Comorbidity of anxiety disorders with anorexia and bulimia nervosa’. American Journal of Psychiatry 2004, 161(12), 2215–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalewska, E.; Bzowska, M.; Engel, J.; Lew-Starowicz, M. ‘Comorbidity of binge eating disorder and other psychiatric disorders: A systematic review’. BMC Psychiatry 2024, 24(1), 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavender, J. M.; Wonderlich, S. A.; Engel, S. G.; Gordon, K. H.; Kaye, W. H.; Mitchell, J. E. Dimensions of emotion dysregulation in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: A conceptual review of the empirical literature. Clinical psychology review 2015, 40, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, M. P.; Smolak, L. The prevention of eating problems and eating disorders: Theory, research, and practice, 2nd ed; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lie, S. Ø.; Rø, Ø.; Bang, L. ‘Is bullying involvement associated with poorer body image and eating disorder symptoms?’. International Journal of Eating Disorders 2021, 54(3), 334–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X; Liu, L; Yu, H. Global, regional, and national burdens of eating disorders from 1990 to 2021 and projection to 2035. Front Nutr 2025, 12, 1595390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallorquí-Bagué, N.; Vintró-Alcaraz, C.; Sánchez, I.; Riesco, N.; Agüera, Z.; Granero, R.; Jiménez-Múrcia, S.; Menchón, J. M.; Treasure, J.; Fernández-Aranda, F. ‘Emotion regulation as a transdiagnostic feature among eating disorders: Cross-sectional and longitudinal approach’. European Eating Disorders Review 2018, 26(1), 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, T. B.; Heron, K. E.; Braitman, A. L. ‘A daily diary study of perceived social stressors, coping, and eating disorder behaviors in college women’. Journal of Health Psychology 2016, 21(9), 2146–2156. [Google Scholar]

- Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Falkner, N.; Story, M.; Perry, C.; Hannan, P. J.; Mulert, S. ‘Weight-teasing among adolescents: Correlations with weight status and disordered eating behaviors’. International Journal of Obesity 2002, 26(1), 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Wall, M.; Guo, J.; Story, M.; Haines, J.; Eisenberg, M. ‘Obesity, disordered eating, and eating disorders in a longitudinal study of adolescents: How do dieters fare 5 years later?’. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 2006, 106(4), 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Wall, M.; Story, M.; Fulkerson, J. A. ‘Are family meal patterns associated with disordered eating behaviors among adolescents?’. Journal of Adolescent Health 2004, 35(5), 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Eisenberg, M. E.; Fulkerson, J. A.; Story, M.; Larson, N. I. ‘Family meals and disordered eating in adolescents: Longitudinal findings from project EAT’. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 2008, 162(1), 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perloff, R. M. ‘Social media effects on young women’s body image concerns: Theoretical perspectives and an agenda for research’. Sex Roles 2014, 71(11–12), 363–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, R.; Chabrol, H. ‘Parental attitudes, body image disturbance and disordered eating amongst adolescents and young adults: A review’. European Eating Disorders Review 2009, 17(2), 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodgers, R. F.; McLean, S. A.; Paxton, S. J. ‘Longitudinal relationships between dietary restraint, body dissatisfaction, and psychological functioning in early adolescent girls’. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 2016, 45(8), 1656–1669. [Google Scholar]

- Shafran, R.; Cooper, Z.; Fairburn, C. G. ‘Clinical perfectionism: A cognitive-behavioural analysis’. Behaviour Research and Therapy 2002, 40(7), 773–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stice, E.; Shaw, H. ‘Role of body dissatisfaction in the onset and maintenance of eating pathology: A synthesis of research findings’. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 2002, 53(5), 985–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stice, E.; Marti, C. N.; Durant, S. ‘Risk factors for onset of eating disorders: Evidence of multiple risk pathways from an 8-year prospective study’. Behaviour Research and Therapy 2011, 49(10), 622–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanofsky-Kraff, M.; Faden, D.; Yanovski, S. Z.; Wilfley, D. E.; Yanovski, J. A. ‘The perceived onset of dieting and loss of control eating behaviors in overweight children’. International Journal of Eating Disorders 2005, 38(2), 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udo, T.; Grilo, C. M. ‘Prevalence and correlates of DSM-5–defined eating disorders in a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults’. Biological Psychiatry 2019, 84(5), 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicent, M.; Gonzálvez, C.; Quiles, M. J.; Sánchez-Meca, J. ‘Perfectionism and binge eating association: A systematic review and meta-analysis’. Journal of Eating Disorders 2023, 11(1), 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteside, U.; Chen, E.; Neighbors, C.; Hunter, D.; Larimer, M. ‘Difficulties regulating emotions: Do binge eaters have fewer strategies to modulate and tolerate negative affect?’. Eating Behaviors 2007, 8(2), 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Implementing school food and nutrition policies: A review of contextual factors; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, 2021; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240035072 (accessed on 21 March 2024).

- Zhu, LY; Larsen, JT; Nissen, JB. Predictors of Anorexia Nervosa and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Comorbidity and Order of Diagnosis in a Danish National Cohort. Int J Eat Disord 2025, 58(9), 1817–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Summary of key nutritional, psychological, and sociocultural risk factors for adolescent eating disorders.

Table 1.

Summary of key nutritional, psychological, and sociocultural risk factors for adolescent eating disorders.

| Domain |

Key Risk Factors |

Illustrative Examples |

Indicative References |

| Nutritional |

Inadequate nutritional knowledge |

Misconceptions, social media diets |

O’Dea (2005); Levine & Smolak (2018) |

| |

Restrictive dieting & meal skipping |

Breakfast omission, calorie restriction |

Stice et al. (2017); Tanofsky-Kraff et al. (2005); Zhu (2025) |

| |

Energy-dense, nutrient-poor foods |

Sugary drinks, fast food |

Story et al. (2002) |

| |

Food choice determinants |

Taste, price, advertising |

Steptoe et al. (1995); Harris et al. (2009) |

| Psychological/Behavioral |

Body dissatisfaction |

Negative body image, comparison |

Stice & Shaw (2002); Rodgers et al. (2016) |

| |

Perfectionism & rigidity |

Strict rules, extreme responses |

Shafran et al. (2002); Vicent et al. (2023) |

| |

Emotional dysregulation |

Bingeing, emotional eating |

Mason et al. (2016); Bacopoulou et al. (2018) |

| |

Low self-esteem |

Self-worth tied to body shape |

Cella et al. (2020); Harter (2012) |

| |

Comorbidity |

Depression, OCD, anxiety |

Hudson et al. (2007); Kaye et al. (2004); Udo & Grilo (2019) |

| Sociocultural |

Media & digital platforms |

Fitspiration, likes, edited photos |

Fardouly & Vartanian (2016); Holland & Tiggemann (2016) |

| |

Family environment |

Parental dieting, weight talk |

Neumark-Sztainer et al. (2008); McHale et al. (2001) |

| |

Peer dynamics |

Teasing, competitive dieting |

Eisenberg et al. (2003); Yager & O’Dea (2010) |

| |

Cultural & gender norms |

Thinness for girls, muscularity for boys |

Ricciardelli & McCabe (2004); Mitchison & Mond (2015) |

| |

Socioeconomic status |

Access disparities, stigma |

Scharff et al. (2010) |

| |

Globalization |

Western body ideals, media influence |

Grabe et al. (2008) |

Table 2.

Disorder-specific symptomatology and consequences of eating disorders in adolescence.

Table 2.

Disorder-specific symptomatology and consequences of eating disorders in adolescence.

| Disorder |

Symptomatology |

Consequences |

| Anorexia nervosa (AN) |

Extreme restriction, fear of weight gain, denial of illness, ritualized eating |

Severe weight loss, amenorrhea, cardiovascular complications |

| Bulimia nervosa (BN) |

Binge–purge cycles, compensatory behaviors, guilt and shame |

Electrolyte imbalance, dental erosion, gastrointestinal issues |

| Binge Eating Disorder (BED) |

Recurrent binge eating without purging, loss of control |

Obesity, comorbid depression and anxiety |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).