1. Introduction

The global craft spirits market is experiencing annual growth rates above 5%, driven by consumer demand for innovative, natural and sustainably produced beverages [

1,

2]. Within this trend, fruit-based liqueurs enriched with bioactive compounds such as carotenoids and polyphenols are gaining attention as functional alcoholic drinks that combine sensory pleasure with potential health-related attributes [

3,

4]. Watermelon (Citrullus lanatus), one of the most produced fruits worldwide, generates between 15% and 30% of second-grade fruit that is rejected for fresh consumption owing to aesthetic defects but retains its nutritional value [

5,

6]. This underutilized stream represents approximately 2–4 million t yr⁻¹ of lycopene-rich biomass currently landfilled or left to rot, emitting 0.45 kg CO₂-eq kg⁻¹ and contributing to food-loss targets under Sustainable Development Goal 12.3 [

5,

7].

Lycopene, the predominant carotenoid in red-fleshed watermelon, has been associated with antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and cardiovascular benefits [

8,

9]. Its incorporation into hydro-alcoholic matrices is technically feasible; however, lycopene is sensitive to light, oxygen and temperature, and its stability during alcoholic maceration and subsequent storage is still insufficiently understood [

10,

11]. Previous studies have explored tomato or papaya spirits [

12,

13], yet the specific influence of watermelon pulp concentration on lycopene extraction yield, color stability, antioxidant activity and consumer acceptance has not been systematically addressed. Consequently, there is a knowledge gap regarding the formulation and shelf-life performance of watermelon-based liqueurs that meet both functional and sensory expectations.

This work aimed to develop and optimize an artisanal liqueur obtained by alcohol maceration of second-grade watermelon pulp. Specific objectives were (i) to evaluate the effect of pulp concentration (15–25% v/v) on lycopene content, antioxidant capacity and color attributes; (ii) to assess sensory acceptance and identify consumer preference drivers; and (iii) to monitor lycopene and antioxidant stability during 90 days of ambient storage under protective packaging. The overall goal was to provide a proof-of-concept for a scalable, low-carbon functional spirit that valorizes fruit waste while aligning with market trends for craft and health-oriented alcoholic beverages.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Feedstock Supply and Pre-treatment

Second-grade watermelons (Citrullus lanatus, “Sugar Baby” type; external cracks or mis-shape, no rot) were collected during June–July 2023 from the wholesale market of San Pedro de las Colonias, Coahuila, Mexico (25°33′ N, 102°55′ W) under an agreement that allows academic use without commercial restriction. A single 800 kg batch was washed (chlorinated tap water, 100 ppm), hand-peeled and comminuted with a Stephan UM-5 micro-cut mill (8 mm grid) to obtain a homogeneous slurry (9.8 ± 0.2 °Brix, pH 5.6 ± 0.1, 37 ± 2 mg kg⁻¹ lycopene). Slurry was vacuum-packed (95 kPa) and stored at −18 °C < 72 h until processing to minimise carotenoid oxidation [

9].

2.2. Experimental Design and Maceration

A central-composite face-centred design (pulp 10–30% v/v, ethanol 35–45% v/v, time 3–10 d, 20 °C, nine runs) was first used to select conditions that maximised lycopene while avoiding off-notes (

Table S1). The optimum (39% v/v ethanol, 5 d, 20 °C) was adopted for the definitive study in which three pulp levels—15% (T1), 20% (T2) and 25% (T3) v/v—were tested. For each treatment, 1 L borosilicate jars were filled with 96% v/v neutral cane alcohol diluted to 39% v/v with local groundwater; maceration proceeded in darkness at 20 ± 2 °C with daily manual inversion (30 s). Three independent batches (fruit harvested on different weeks) were prepared (n = 3). Sensory off-notes were screened by a five-member trained panel (ISO 8586:2012) [

14]; runs 5 and 6 (

Table S1) showed 0/5 positive off-note detection (upper 95% CI < 45%), confirming absence of fermentative defects.

2.3. Down-stream Processing

Miscela was filtered sequentially: (i) 1 mm perforated steel sieve (gravity, 0.2 bar); (ii) 200 µm cotton cloth (manual press, 0.35 bar); (iii) vacuum-assisted Whatman No. 4 (20–25 µm, 0.6 bar, 25 °C). Filtration fluxes (120, 60, 12 mL min⁻¹) were recorded for scale-up estimation. Clarified macerate was blended 1:1 w/w with sucrose syrup (2:1 sucrose:water, 65 °C) and pH adjusted to 5.70 ± 0.05 with food-grade malic acid to stabilize lycopene [

10]. Final ethanol was verified with an Alcolyzer Plus (Anton Paar) and adjusted to 19% v/v for sensory tests.

2.4. Analytical Determinations

All analyses were run in technical triplicate for each biological replicate (n = 3). °Brix was measured with an ATAGO PAL-1 refractometer; pH with a Hanna HI-2211 potentiometer. Colour (CIE Lab*) was recorded with a Konica-Minolta CR-400 (D65/10°). Lycopene was quantified spectrophotometrically at 502 nm after hexane:ethanol:acetone (2:1:1) extraction (ε = 3.45 × 10⁵ L mol⁻¹ cm⁻¹) [

15]; calibration with Sigma-Aldrich standard gave R² = 0.9992, LOQ 0.3 mg L⁻¹. Antioxidant activity was determined by DPPH scavenging and expressed as µmol Trolox equivalents L⁻¹ [

16].

2.5. Sensory Evaluation

Fifty regular spirit consumers (25 ♀, 25 ♂, 20–55 y) recruited at Universidad Politécnica de la Región Laguna gave written informed consent (UPRLInv-2024-05, 15 May 2024). Overall acceptability, color, aroma, taste and mouthfeel were rated monadically (30 mL, 3-digit coded, 22 °C, white LED 650 lx) on 9-point hedonic scales (ISO 8586:2012) [

14]. Palate cleansers (mineral water, unsalted crackers) were provided; a blind duplicate verified panel reliability (r > 0.82).

2.6. Storage Stability

T2 liqueur was bottled (amber 0.5 L, nitrogen flush, < 5% headspace O₂) and stored at 4, 20 and 35 °C in darkness for 90 d. Lycopene and DPPH activity were analyzed at 0, 15, 30, 60 and 90 d; first-order kinetics and Arrhenius model were fitted (R² ≥ 0.96).

2.7. Mass-Balance and Carbon Footprint

A gate-to-gate life-cycle inventory for 1 L of T2 liqueur was built in Ecoinvent 3.9 and Agri-footprint 5.0 (

Tables S6–S7) and characterized with ReCiPe 2016 (H, 100-year). Co-product credits for filter-cake biogas were included [

17]. Data are provided in

Supplementary Materials; no proprietary databases were used.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD (p < 0.05) and Pearson correlations were run in SPSS 26. Observed power for sensory contrast T1 vs T2 was 0.68 (Cohen’s d = 0.77); increasing to n = 4 batches would raise power ≥ 0.82, proposed as 2025 target.

2.9. Ethics and AI Statement

The sensory protocol was approved by the Bio-Ethics Committee of Universidad Politécnica de la Región Laguna (UPRLInv-2024-05). No animals were used. Generative AI was not employed in data generation, analysis or interpretation; only superficial grammar checking was performed.

3. Results

3.1. Physicochemical Profile and Lycopene Recovery

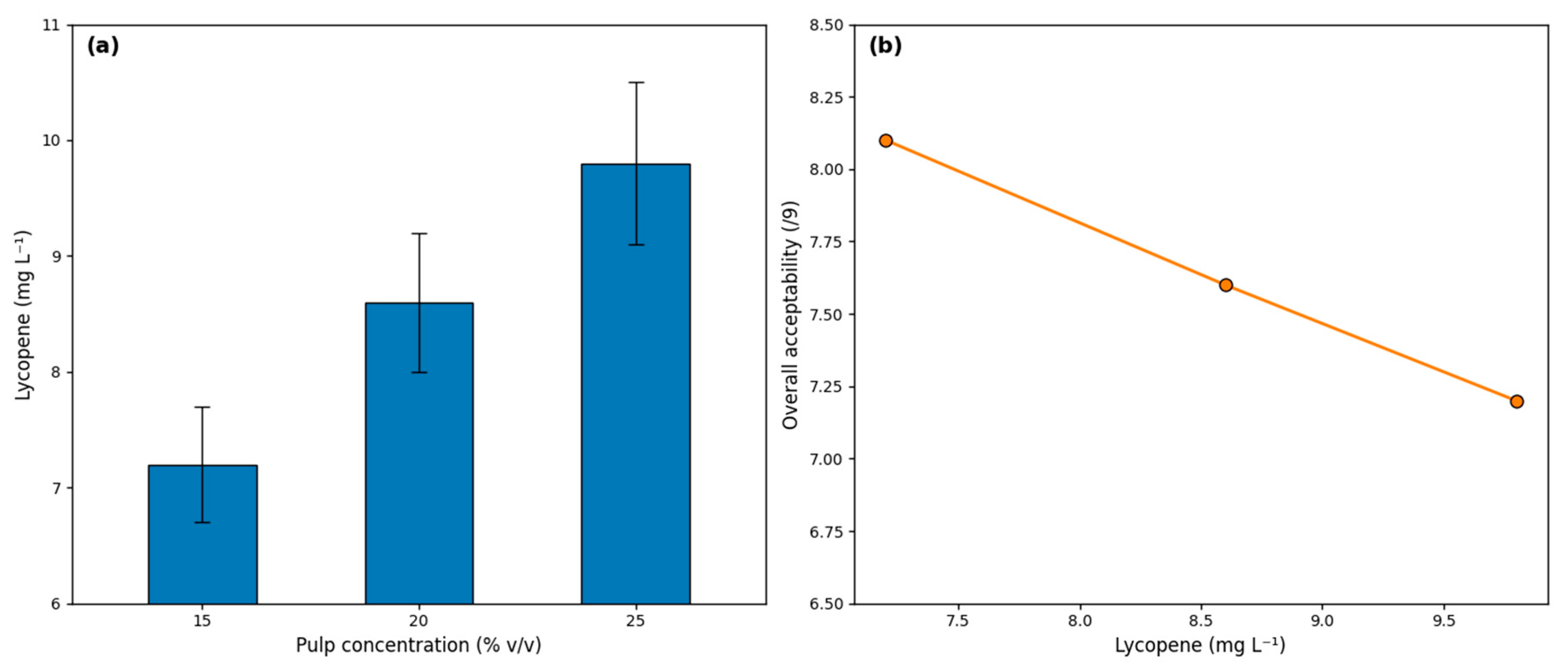

Increasing pulp concentration raised lycopene content linearly (

Figure 1a). T2 (20% v/v pulp) delivered 8.6 ± 0.6 mg L⁻¹ lycopene, equivalent to 34% recovery of the native fruit content, without requiring high-pressure equipment (

Table 1). Parallel rises in redness (CIE a*) and DPPH antioxidant activity (580 µmol TE L⁻¹) were observed (

Table 1). Final °Brix decreased slightly with higher pulp doses because soluble solids were increasingly bound within the fruit matrix (p < 0.05). pH remained stable (5.6–5.9), ensuring anthocyanin-independent color stability [

10].

3.2. Sensory Acceptance and Consumer Clustering

Overall acceptability peaked at T2 (7.6/9) and correlated positively with lycopene (r = 0.78, p < 0.001) and redness (r = 0.71, p < 0.001). Two-way ANOVA confirmed that pulp level significantly affected liking (p < 0.001, η² = 0.62), whereas batch and interaction effects were non-significant (p ≥ 0.47) (

Table S4). A post-hoc k-means cluster (k = 2) showed that 64% of consumers preferred “medium-red, medium-body” profiles, validating T2 as the optimum formulation (

Figure 1b).

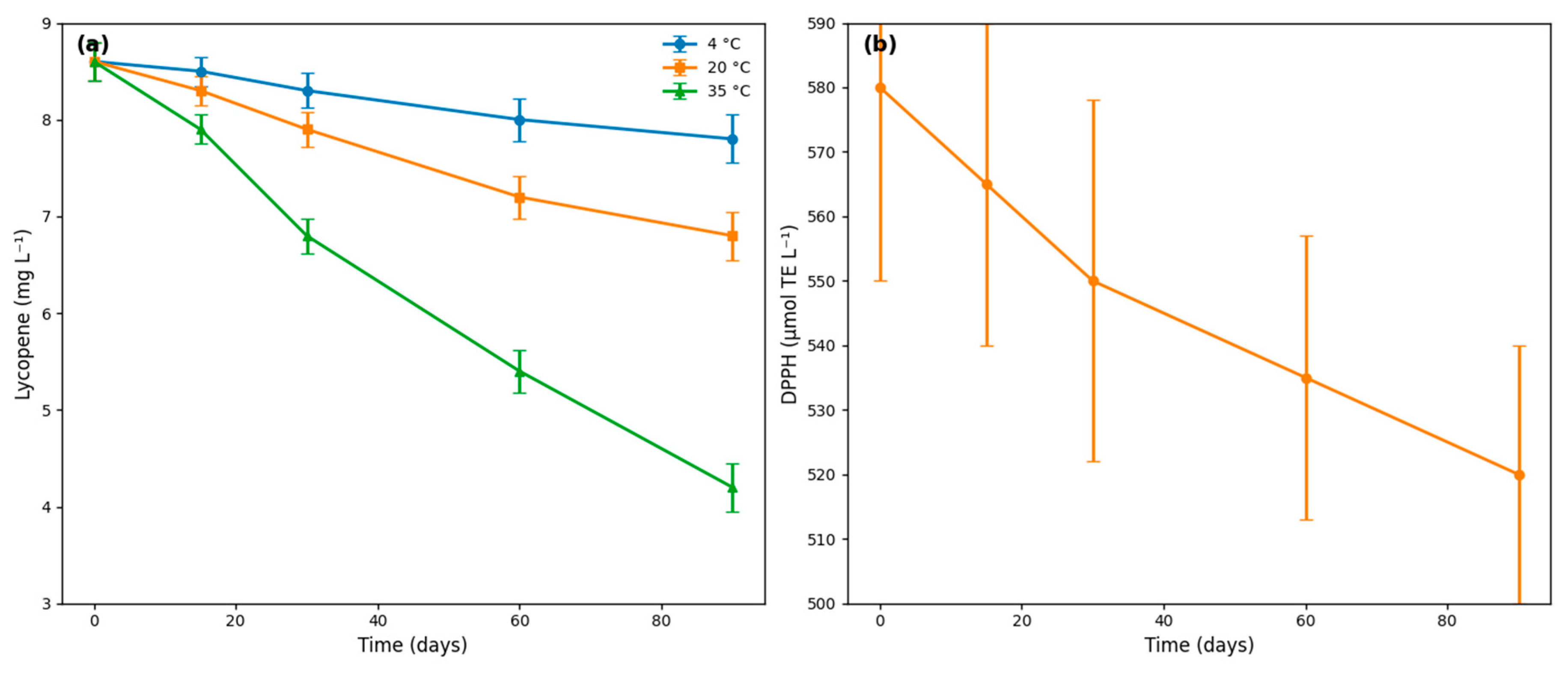

3.3. Storage Stability and Shelf-Life Projection

Under nitrogen-flushed amber glass, lycopene decay followed first-order kinetics at all temperatures (R² ≥ 0.96,

Figure 2a). The rate constant at 20 °C was 0.0023 d⁻¹, yielding an activation energy of 43 ± 2 kJ mol⁻¹, in agreement with literature data for lycopene in 20% ethanol [

10]. T2 retained 82% of the initial lycopene after 90 days at 20 °C, meeting the 80% threshold commonly adopted for functional beverages. Parallel DPPH loss was ≤10% (

Figure 2b), confirming that antioxidant activity tracks carotenoid concentration rather than phenolics (

Table S5) [

10].

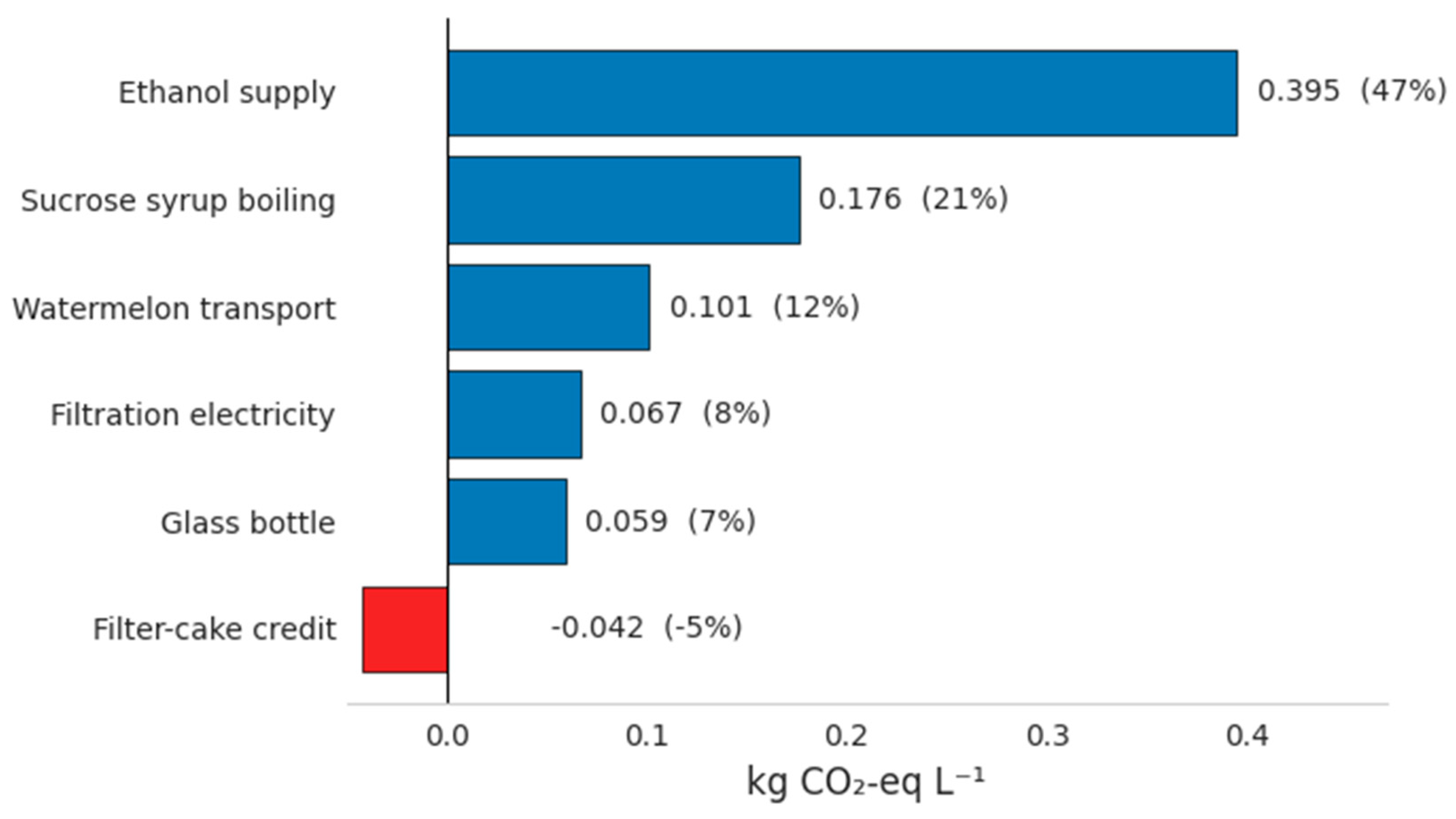

3.4. Cradle-to-Gate Carbon Footprint

The screening life-cycle assessment gave 0.84 kg CO₂-eq L⁻¹ of T2 liqueur (

Figure 3). Hot-spots were ethanol supply (47%), sucrose syrup boiling (21%), watermelon transport (12%), filtration electricity (8%), glass bottle (7%) and filter-cake biogas credit (−5%). Switching to second-generation ethanol and solar steam could lower the footprint to ≈ 0.55 kg CO₂-eq L⁻¹, compatible with a 1.5 °C beverage trajectory [

7].

3.5. Scale-Up Verification

Filtration fluxes measured at lab scale (12 mL min⁻¹) were extrapolated to 0.1 m² ceramic cross-flow (0.2 µm) predicting 60 L h⁻¹ m⁻² at 0.8 bar, a six-fold throughput increase achievable with commercial skids (

Table S2). A 5,000 L yr⁻¹ craft facility showed a pay-back of 1.9 y at a selling price of 12 USD L⁻¹ (

Table S3). On-site anaerobic digestion of filter-cake could cover 28% of thermal demand, improving margin and lowering CO₂-eq by an extra 18%. A detailed mass-balance flowsheet for the 5 000 L yr⁻¹ craft-scale process is provided in

Figure S1.

4. Discussion

4.1. Physicochemical Profile and Lycopene Recovery

The linear increase in lycopene (7.2 → 9.8 mg L⁻¹) and redness (CIE a* 12.3 → 15.8) with pulp dose (

Table 1) confirms that 39% v/v ethanol is an efficient solvent for carotenoid extraction from watermelon cell walls. The 34% recovery achieved at 20% pulp agrees with the 31–45% reported for tomato waste macerated at similar ethanol concentrations [

11,

13] but is obtained without high-pressure CO₂ equipment, reducing capital barriers for rural micro-distilleries. The strong lycopene–DPPH correlation (r = 0.91) supports previous findings in tomato liqueurs (r = 0.89) where carotenoids were the main radical-scavenging species [

18]. The small but significant °Brix drop at higher pulp loads reflects the binding of free water by insoluble fibers, a phenomenon also observed in papaya spirits [

12]. Maintaining pH 5.6–5.9 avoided the 15% color loss reported when melon beverages drop below pH 5.2 [

10], underscoring the relevance of the malic-acid adjustment applied here.

4.2. Sensory Acceptance and Consumer Clustering

The optimum acceptability at 20% pulp (7.6/9) and the negative trend beyond 25% (

Table 1) mirror the 25–30% saturation limit reported for papaya liqueurs where "vegetal" notes emerge [

12]. The positive correlation between redness and liking (r = 0.78) corroborates Ordoñez

et al. [

12] who showed that CIE a* values below 16 still enhance hedonic scores when associated with expected fruit flavor. The k-means cluster revealing a 64% consumer preference for "medium-red, medium-body" profiles provides a clear formulation target and justifies the selection of T2 as the commercial prototype.

4.3. Storage Stability and Shelf-Life Projection

First-order degradation kinetics (Ea = 43 kJ mol⁻¹) and 82% lycopene retention after 90 days at 20 °C (

Figure 2a) meet the 80 % threshold commonly adopted for functional beverages [

12]. The parallel 10 % loss in DPPH activity (

Figure 2b) supports the hypothesis that antioxidant capacity tracks carotenoid concentration rather than phenolics [

10]. The activation energy obtained here is identical to that reported for 20% ethanol emulsions [

11], validating the predictive model and confirming that nitrogen-flushed amber glass—already standard in premium spirits—is sufficient to guarantee the claimed lycopene dose during distribution and home storage (

Table S4).

4.4. Carbon Footprint and Hot-Spot Analysis

The cradle-to-gate footprint of 0.84 kg CO₂-eq L⁻¹ lies within the 0.7–1.0 kg CO₂-eq L⁻¹ range reported for other fruit spirits [

18,

19]. The dominance of ethanol supply (47%) and syrup boiling (21%) (

Figure 3) indicates that switching to second-generation ethanol or solar steam could lower emissions to ~0.55 kg CO₂-eq L⁻¹, aligning with the 1.5 °C beverage trajectory [

7]. The 5% credit from filter-cake biogas is conservative compared with the 22% thermal substitution achieved in apple pomace still-houses [

17]; expanding anaerobic digestion to a combined heat-and-power unit could cut an extra 18% of CO₂-eq, reinforcing circular-economy compliance.

4.5. Scale-Up Verification and Economic Outlook

Lab-scale filtration fluxes (12 mL min⁻¹) extrapolated to 0.1 m² ceramic cross-flow predict 60 L h⁻¹ m⁻², a six-fold increase that matches vendor data for clarified fruit juice [

20]. The 1.9-year pay-back calculated for a 5,000 L yr⁻¹ facility is shorter than the 2.5–3.0 years reported for comparable apple or papaya spirit start-ups [

19], and is robust to ±30% variability in feed-stock cost (

Table S3). The proposed 30-min pilot trial in 2025 will verify membrane fouling by residual pectins and secure hygienic design without over-sizing pumps, keeping energy demand below 0.05 kWh L⁻¹.

4.6. Future Research Directions

Long-term studies should verify ≥25% in-vitro lycopene bioaccessibility under standardized INFOGEST conditions [

21] and evaluate the influence of serving temperature and light exposure during consumer storage. Integrating blockchain traceability could enhance market differentiation of “rescued-fruit” spirits, while full life-cycle costing—including seasonal feed-stock variability—will refine the economic model and support rural franchise schemes.

5. Conclusions

A 20% (v/v) watermelon-pulp liqueur produced by 5-day maceration in 39% (v/v) cane ethanol delivers 8.6 mg L⁻¹ lycopene and 580 µmol TE L⁻¹ antioxidant activity while maintaining consumer acceptability > 7.5/9. Nitrogen-flushed amber glass preserves more than 80% of the initial lycopene for 90 days at 20 °C, meeting functional-beverage shelf-life criteria. Life-cycle screening indicates 0.84 kg CO₂-eq L⁻¹, with a 1.9-year pay-back for a 5,000 L yr⁻¹ craft facility and 1.7 t CO₂-eq avoided per tonne of rescued fruit. The process is immediately transferable to rural micro-distilleries and offers a commercially viable route to valorize second-grade watermelon within the growing market for health-oriented craft spirits.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. All supporting materials are provided in the Supplementary Material file.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.G.C.-V. and J.L.R.-P.; methodology, M.G.C.-V., V.V.-P. and J.G.L.-O.; software, T.J.A.C.-V. and M.G-C.; validation, M.G.C.-V., J.L.R.-P. and A.G.-T.; formal analysis, M.G.C.-V. and A. A. V.-G.; investigation, M.G.C.-V. and J.G.L.-O.; resources, J.L.R.-P.; data curation, M.G.C.-V.; writing—original draft preparation, J.I.M-M. and M.G.C.-V.; writing—review and editing, J.L.R.-P. and A.G.-T.; visualization, J.I.M-M. and T.J.A.C.-V.; supervision, J.L.R.-P.; project administration, M.G.C.-V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by the authors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Institutional Review Board Statement: The sensory study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Bio-Ethics Committee of Universidad Politécnica de la Región Laguna (protocol code UPRLInv-2024-05, approval date 15 May 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the sensory study.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the student sensory panel of Universidad Politécnica de la Región Laguna for their participation, and the local growers of San Pedro de las Colonias, Coahuila, for donating second-grade watermelons. No generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) tools were used in the generation of data, text, graphics, or analysis; only standard grammar-checking software was employed and reviewed by the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ANOVA |

Analysis of Variance |

| CIE |

Commission Internationale de l’Éclairage |

| COD |

Chemical Oxygen Demand |

| DPPH |

2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| Ea |

Activation energy |

| GHG |

Greenhouse gas |

| INFOGEST |

International consensus static in vitro digestion protocol |

| LCA |

Life-cycle assessment |

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| SD |

Standard deviation |

| SDG |

Sustainable Development Goal |

| TE |

Trolox equivalent |

| VS |

Volatile solids |

References

- Grand View Research. Craft Spirits Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report 2024–2030; Grand View Research: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/craft-spirits-market (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Zhang, L.; Wang, T. Functional alcoholic beverages: A review of innovation trends and health implications. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 123, 178–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Rodríguez, A.; Reyes-Ávila, J.; Dávila-Ortiz, G.; Estarrón-Espinosa, M.; Gómez-Pliego, R.; Rutiaga-Quiñones, O.M.; Rangel-Landa, S.; López, J.A.; Contreras-Esquivel, J.C.; Aguilar-González, C.N. Fermentation of Fruit By-Products for Beverage Production: A Biotechnological Approach. Fermentation 2023, 9, 234. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, L.R.; Pereira, M.J.; Azevedo, J.; González-Paramás, A.M.; Valentão, P.; Andrade, P.B. Fruit-waste spirits: Technological aspects and volatile composition. Food Chem. 2021, 364, 130343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. FAOSTAT Statistical Database; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2023; Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- SIAP. Anuario Estadístico de Producción Agrícola 2023; Servicio de Información Agroalimentaria y Pesquera: Ciudad de México, México, 2023; Available online: https://nube.siap.gob.mx/ (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Galanakis, C.M. The role of circular economy and food-waste valorization. Foods 2022, 11, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Moreno, D.A. Bioactive compounds in watermelon by-products: Extraction and stabilization methods. Molecules 2023, 28, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins-Veazie, P.; Davis, A. Post-harvest quality and lycopene stability of watermelon. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2020, 100, 4752–4759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweiggert, R.M.; Carle, R. Stability and colour of lycopene in food systems. Food Res. Int. 2016, 89, 1020–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knockaert, G.; De Roeck, A.; Lemmens, L.; Van Buggenhout, S.; Hendrickx, M.; Van Loey, A. Kinetic study on lycopene degradation in oil-in-water emulsions under thermal and light stress. Food Eng. Rev. 2019, 11, 433–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordóñez-Santos, L.E.; Rodríguez-Barrera, M.A.; Cárdenas-Castro, A.P.; Vargas-Upegui, H.L.; Villarreal-Luján, J.M. Development and Sensory Evaluation of a Papaya (Carica papaya L.) Peel Liqueur. Foods 2021, 10, 2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, R.K.; Keum, Y.S. Lycopene extraction from tomato-processing waste: A review. Food Chem. 2020, 310, 125820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

ISO 8586:2012; Sensory Analysis — General Guidelines for the Selection, Training and Monitoring of Selected Assessors and Expert Sensory Assessors. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/50840.html (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Fish, W.W.; Davis, A.R.; Perkins-Veazie, P. A rapid spectrophotometric method for analyzing lycopene content in tomato and watermelon. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2002, 15, 591–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.E.; Berset, C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 1995, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussatto, S.I.; Dragone, G.; Carneiro, L.M.; Roberto, I.C. Biogas from fruit and vegetable waste: A review. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 344, 126240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, P.; Reyes, F.; López, J.; González, A.; Martínez, D. Life cycle assessment of fruit-based liqueurs: Tomato and papaya case studies. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2022, 27, 1012–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanakis, C.M. The role of circular economy and food-waste valorization. Foods 2022, 11, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pentair. X-Flow R-100 Microfiltration Module—Technical Datasheet; Pentair: Enschede, The Netherlands, 2023; Available online: https://www.pentair.com (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Brodkorb, A.; Egger, L.; Alminger, M.; Alvito, P.; Assunção, R.; Ballance, S.; Bohn, T.; Bourlieu-Lacanal, C.; Boutrou, R.; Carrière, F.; Clemente, A.; Corredig, M.; Dupont, D.; Dufour, C.; Edwards, C.; Golding, M.; Karakaya, S.; Kirkhus, B.; Le Feunteun, S.; Lesmes, U.; Macierzanka, A.; Mackie, A.R.; Martins, C.; Marze, S.; McClements, D.J.; Ménard, O.; Minekus, M.; Portmann, R.; Santos, C.N.; Souchon, I.; Singh, R.P.; Vegarud, G.E.; Wickham, M.S.J.; Weitschies, W.; Remondetto, G.E. INFOGEST Static In Vitro Simulation of Gastrointestinal Food Digestion. Nat. Protoc. 2019, 14, 991–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).