1. Introduction

The growing interest in healthy eating has driven global demand for functional beverages, a segment that is also experiencing significant growth in Brazil. In this scenario, foods with probiotic potential have gained prominence for their ability to promote intestinal health and strengthen the immune system [

1], offering benefits that include restoring the microbiota and modulating the immune response [

2].

Among functional beverage options, water kefir stands out as a traditional and versatile fermented product. Water kefir grains consist of a complex polysaccharide matrix, composed primarily of dextran and a levan fraction, which harbors a symbiosis of microorganisms, including lactic acid bacteria (LAB), acetic acid bacteria (AAB), and yeast [

3,

4]. It has a gelatinous and translucent appearance, with irregular shapes and sizes. The microbial diversity and, consequently, the physicochemical composition of kefir can vary significantly depending on the origin of the grains, cultivation methods, raw materials, and processing technology [

5,

6]. This complex metabolic activity gives the final beverage unique flavor and aroma characteristics, as well as natural carbonation, resulting from the production of ethanol, lactic acid, and carbon dioxide. Furthermore, beneficial metabolites such as glycerol, mannitol, esters, and B vitamins are synthesized during the fermentation process [

7].

However, the stability and sensory characteristics of water kefir are critically influenced by the types and concentrations of nutrients, as well as the flavorings and fermentation conditions used [

8,

9]. Adjusting these proportions is crucial to achieving a stable final product with health benefits for the consumer. Considering the growing demand for products that cater to specific audiences, such as vegans, lactose-intolerant individuals, and consumers with healthy eating habits, water kefir has great potential to meet these expectations. Furthermore, the presence of bioactive compounds with anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and antimicrobial properties has been extensively investigated [

10], which significantly contributes to its popularization.

In this context, systematically optimizing the formulation of fermented water kefir beverages is essential to ensure standardization, improve sensory and functional characteristics, and expand their market potential. The application of statistical experimental design tools allows for the efficient exploration of interactions between components and the identification of optimal proportions.

Thus, the objective of this study was to develop a fermented, carbonated, and flavored beverage from drinking water, brown sugar, fruit juice, and water kefir grains, and to evaluate its sensory, physicochemical, and microbiological aspects.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Activation of Water Kefir Grains and Standard Fermentation of Fruit-Based Water Kefir

Water kefir grains (stock from the Laboratory of Unit Operations at UFES, Alegre, Brazil) were activated and cultured in a brown sugar solution (6.5% m/v) in open containers at 30 °C. The process involved filtration and reuse of the grains in a new solution every 24 h, for 7 days, following Almeida [

11] with modifications.

The beverage preparation comprised two consecutive fermentation stages: Fermentation 1 (F1) and Fermentation 2 (F2). In F1, kefir grains (5% m/v) were aerobically inoculated into a brown sugar solution (3-10% m/v) and incubated at 20-30°C for 24 or 48 h. After removing the grains, the kefired water was flavored with whole grape juice (10-50%) and subjected to F2, which occurred anaerobically at 30°C for 24 h. The finished beverages were then refrigerated at 4°C for 24 h for analysis.

2.2. Study of Fermentation Kinetics: Influence of Temperature and Total Soluble Solids on Fermentation Kinetics (F1)

The kinetics of Fermentation 1 (F1) were investigated using a Central Composite Rotational Design (CCRD), varying temperature (20-30°C) and soluble solids (3-10°Brix) in 11 experimental units (

Table 1). The pH was monitored as a response variable at predefined intervals throughout 48 h of fermentation. Fermentations were carried out in 250 mL open beakers with 5% (m/v) kefir grains and temperature control. Ultimately, the grains were separated by filtration, and the fermented liquid (kefired water) was characterized by its pH, total titratable acidity, alcohol content, sugars, color, and counts of lactic acid bacteria and enterobacteria.

2.3. Choosing the Flavor of Fruit Juice Used to Flavor Water Kefir

Flavor selection was performed through sensory evaluation of the flavored formulations, using a Completely Randomized Design (CRD). Sensory attributes (color, aroma, flavor, carbonation, and overall impression) and purchase intention were compared. Data were analyzed using Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), and in cases of significant differences (p < 0.05), the means were compared using Tukey’s test.

2.4. Determination of the Proportion of Grape Juice in the Formulation of Water Kefir

With the flavor selected, the ideal proportion of juice in the beverage was determined via sensory analysis, using a Blend Design (

Table 2) with the sensory analysis itself as the response variable.

2.4.1. Multivariate Optimization Analysis: Desirability Function

The formulation was defined using the Desirability Function (Derringer and Suich, 1980), a methodology that allows the simultaneous optimization of multiple response variables to identify the ideal formulation conditions. This statistical approach transforms each evaluated response variable (such as sensory attributes and purchase intention) into an individual desirability (di), ranging from 0 (undesirable) to 1 (desirable), calculated according to Equation 1.

where:

is the target (optimal) value

is the minimum value for responses that will be maximized

The overall desirability (D) was then calculated as the geometric mean of the individual desirability (di) (Equation 2).

Overall desirability (D), which ranges from 0 to 1, serves as an integrated measure of the formulation’s overall quality. The optimal condition is the one that maximizes D, indicating the point of greatest simultaneous desirability for all response variables.

2.5. Storage Stability Study

Based on the optimized treatment, a physical-chemical and microbiological stability study of the beverage was carried out under refrigeration (4°C) for 42 days. Evaluations were conducted weekly (0-6 weeks) to monitor pH, alcohol content, soluble solids, sugars (glucose, fructose, and sucrose by HPLC), and counts of lactic acid bacteria, acetic acid bacteria, yeasts, and the presence of enterobacteria.

2.6. Analytical Methodology

2.6.1. Sensory Analysis

The sensory analysis used acceptance tests on a structured hedonic scale, with nine points for color, aroma, flavor, carbonation, and overall impression, and five points for purchase intention. More than 100 untrained tasters (aged 18–60) participated, evaluating randomly served and coded 30 mL samples using a methodology adapted from Stone and Sidel [

23]. This research was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Espírito Santo (UFES) (opinion number 6.479.574).

2.6.2. Physicochemical Analysis and Phenolic Compound Content of the Fermented Beverage

The beverages were characterized by several physicochemical analyses, including total soluble solids (TSS), pH, ethanol concentration, reducing and total sugars, and color. TSS was determined directly by digital refractometry (model DR-A1, ATAGO), with results expressed in °Brix. The pH was measured using a digital pH meter (Metrohm, model 826 pH mobile). The quantification of reducing and total sugars followed the methodology of Maldonade et al. [

25]. To determine the individual glucose, fructose, and sucrose contents, high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was employed, following the methodology described by Bravim et al. [

22]

Color analysis was performed using a colorimeter (Konica Minolta, Spectrophotometer CM-5) to obtain the parameters L* (lightness), a* (green-red axis), and b* (blue-yellow axis). Alcohol content was measured with a portable meter (model ABV Valuer, Nova Creations Ltd.a., Brazil) after decarbonation of the sample in an ultrasonic bath (CTA ultrasonic systems, UPL, Brazil) at 25°C for 30 minutes, and dilution 1:3 (v/v), with the calculation adjusted by Equation (3):

where: V is the sample volume and Fd is the applied dilution factor.

Additionally, the total phenolic compound content was determined using the Folin-Ciocalteu methodology [

23], with results expressed as mg of gallic acid equivalent/mL. Antioxidant capacity was assessed by three different methods: ABTS (2,29-azinobis-(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)), DPPH (1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl) and FRAP (iron reduction). The ABTS and DPPH methods were performed as described by Araújo, Macedo, and Teixeira (2023), expressed as mg of trolox equivalent/mL. The determination of antioxidant capacity by the FRAP method followed the description of Vimercati et al. [

24], with results expressed as mg of ferrous sulfate/mL.

2.6.3. Microbiological Analysis of Fermented Beverage

The microbiological characterization of the fermented beverage focused on quantifying specific populations and detecting contaminants. Sample preparation for decimal serial dilutions was performed as described by Silva et al. [

26].

Total lactic acid bacteria and acetic acid bacteria counts were determined by deep plating on specific media (MRS and GYC, respectively), with incubation under controlled conditions, following the methodology detailed by Silva et al. [

26]. Yeast quantification was performed using a Neubauer chamber count with methylene blue staining, as adapted from Freitas et al. [

24]. Finally, total enterobacteriaceae counts were performed using the pour plate method on VRBG agar, as described by Silva et al. [

26].

2.7. Statistical Analysis

The statistical designs employed, such as the Central Composite Rotational Design (CCRD), the Completely Randomized Design (CRD), and the Mixture Design, were applied according to the nature of each experiment and have already been detailed in the previous methodological sections. For the analysis of quantitative data, nonlinear regression analysis was employed, with models adjusted using the least squares method, and the quality was assessed by the coefficient of determination (R2). In situations where no clear regression trend was observed, or for specific comparisons, Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was used, with comparison of means by Tukey’s test (p < 0.05).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Influence of Temperature and Total Soluble Solids on Fermentation Kinetics (F1)

Figure 1 illustrates the pH variation curves over time for the various treatments, and

Table 3 presents the model parameters adjusted for fermentation kinetics.

The fermentation kinetics, characterized by pH variation over time, demonstrated, as observed in

Figure 1, that the pH value progressively decreased during the fermentation period, following a modified exponential model. This type of model is characterized by its ability to express a decay rate that is not constant but rather changes over time, a phenomenon common in biological systems, such as fermentation. The model fitted is the one described in Equation 4. The fitted parameters are presented in

Table 3.

Where: A represents the initial or maximum pH value (i.e., the pH at time zero), e is the base of the natural logarithm, k denotes a decay rate constant, t corresponds to the fermentation time, and B is an exponent that directly influences the shape of the pH decay curve as a function of time.

The adjusted models demonstrated an excellent fit to the experimental data, with consistently high coefficients of determination (R

2) for all treatments (

Table 3). These values, ranging from 0.9759 to 0.9957, indicate that the models were able to explain a significant portion of the observed variability in pH throughout the fermentation process, confirming the adequacy of the modified exponential model in describing the acidification kinetics under each experimental condition.

These results are similar to those reported by Zongo [

12], who, when studying the fermentation kinetics of a new palm sap-based kefir drink, observed a drop in the pH value from 6.53 to values around 4.00 after 48 hours of fermentation at 22 °C. An exponential or modified exponential decay of pH as a function of time was also found by other authors such as Almeida [

11].

The drop in pH values of the samples is an expected phenomenon related to the metabolism of microorganisms, primarily lactic and acetic bacteria, as well as yeasts. These microorganisms not only produce acids but also generate ethanol, volatile compounds, and carbon dioxide [

12].

The fermentation period is an important factor influencing the final characteristics of the product, with first fermentation times often reported as varying between 24 and 48 hours in the literature [

11,

13]. To understand the effect of process time on the pH value for the different treatments, the pH was predicted after 24 and 48 hours using the 11 modified exponential models fitted to the kinetic data presented in

Table 4.

The initial pH of each treatment, which reflects the pH at the beginning of the fermentation process (when time, t, is equal to zero), is expressed by parameter A of the modified exponential model. As shown in

Table 4, the initial pH ranged from 4.69 (Treatment T7) to 5.56 (Treatment T5), demonstrating different starting conditions between the experiments. Throughout the fermentation, a significant decrease in pH was observed, as expected. After 24 hours, the pH values predicted by the models ranged from 3.79 (Treatment T7) to 4.55 (Treatment T5). This acidification trend continued until 48 hours, with pH values ranging between 3.32 (Treatment T3) and 4.13 (Treatment T5). Only treatment 5, after 24 hours, presented a pH value greater than 4.5.

Reducing the pH during fermentation is a crucial factor for ensuring the microbiological safety and preservation of fermented beverages. Reaching and maintaining a pH below 4.5 is a critical limit, as it creates an environment unfavorable for the growth of most pathogenic microorganisms, especially sporulating microorganisms that are unable to germinate and produce toxins in such acidic conditions [

14]

Considering the acidification rate and lowest final pH value, the three best treatments would be T3, T6, and T7. Treatment T6 demonstrated good performance (R2 of 0.9902), which was higher than that of T3 (R2 of 0.9776) and T7 (R2 of 0.9866), thus presenting a slight advantage over the others. Although Treatment T3 presented the highest decay constant (k = 0.06518), indicating a potentially faster acidification rate, its significantly higher initial pH (5.55) resulted in a pH of 3.95 after 24 hours, still higher than the pH of 3.85 achieved by T6 during the same period.

This demonstrates that, starting from a lower initial pH (5.04), T6 can efficiently and early reach the safe pH range. Within 48 hours, the pH of T6 stabilizes at 3.37, a value very close to the lowest pH observed (T3 at 3.32 and T7 at 3.39). This combination of a rapid and effective pH drop to safe values in the initial critical period, combined with an R

2 of 0.9902, which attests to the high accuracy of the model, led to the T6 Treatment being chosen to continue the work. Thus, the experiment continued using 6.5% brown sugar and a fermentation temperature of 30°C. This condition is within the range of values reported in the literature. Zannini [

9] used 7.5% sugar and a fermentation temperature of 26°C; Almeida [

11] established conditions of 5% water kefir grains, 10% added brown sugar, and 25°C; Arapovi

’c [

15] used 5.56% sugar and 22°C. Therefore, there is no established standard, but the proposed values are close to the range found in the literature.

3.1.1. Physicochemical Characterization of the Fermented Beverage After 24 and 48 Hours

After selecting Treatment T6, the next step involved determining the ideal time for the first fermentation. However, this decision could not be based solely on pH values, as consumer acceptance is a critical factor for commercial success and product viability. Considering the importance of sensory analysis in guiding consumer preferences, a sensory study was conducted to compare the 24- and 48-hour fermentation times in F1. To ensure comparability of results, the second fermentation (F2) and the amount of juice used for flavoring were standardized as described in the methodology.

Table 5 presents the results of the physical-chemical and sensory analyses of the fermented beverage at 24 and 48 hours of fermentation.

Table 5 presents the physicochemical parameters of water kefir during the first fermentation (F1) at 24 and 48 hours. The data confirm the expected sugar consumption, with a decrease from 6.5% of added sugar at time zero to 1.80% of total sugars (24 h) and 1.30% (48 h).

No significant difference was observed for the parameters of soluble solids (7.77 °Brix in 24 h and 7.63 °Brix in 48 h), pH (3.66 in 24 h and 3.65 in 48 h), and alcohol content (0.73 °GL in 24 h and 0.75 °GL in 48 h). This suggests that, based on these indicators, the extension of primary fermentation (F1) from 24 to 48 h did not result in significant changes.

Specifically, regarding the alcohol content of the beverage, there were no significant differences between the 24- and 48-hour fermentation times (p > 0.05), with an average value of 0.74% (v/v). In the context of Brazilian legislation, a beverage is classified as non-alcoholic when its alcohol content is less than 0.5% (v/v), as established by Decree No. 6871/2009 [

16].

Although there is no specific legislation for water kefir in Brazil, and the Normative Instruction for milk kefir [

17] does not define standards for alcohol content, the analogy with kombucha is the best option for labeling and classification purposes. Kombucha, a fermented beverage that shares process similarities with water kefir by using SCOBY inoculum containing lactic acid bacteria, acetic acid bacteria, and yeast [

19], is regulated in Brazil by Normative Instruction No. 41/2019 [

18]. This regulation establishes that if the alcohol content of kombucha exceeds 0.5% (v/v), the attestation of the alcohol content becomes mandatory.

Given the values found in this study (an average of 0.74%), which exceed the 0.5% (v/v) limit, water kefir should therefore have its alcohol content declared on the label, following the precedent established for fermented products with a similar profile. Maintaining the alcohol content below 0.5% (v/v) is, in fact, a significant challenge for producers of fermented beverages marketed as non-alcoholic, such as kefir, kombucha, tepache, among others. TRAN [

19] defines kombucha as a low-alcohol fermented beverage, demonstrating that this type of beverage produces alcohol in small quantities.

Ethanol production is an inherent characteristic of water kefir fermentation, driven primarily by the activity of yeasts present in the grains. The scientific literature presents a wide range of alcohol contents for water kefir, ranging from trace amounts to over 2% (v/v), depending on factors such as the predominant yeast strain, initial sugar concentration, and fermentation time/temperature [

20].

Regarding the total sugar content, a slight reduction was observed (from 1.80% to 1.30%), indicating continued fermentation activity. This continuity is corroborated by the increase in the lactic acid bacteria population. The sugar consumption profile, characterized by a preference for glucose and the subsequent formation of ethanol and organic acids such as lactic and acetic acids, reflects the classic metabolic pattern of water kefir fermentations, as described by Laureys [

21].

Furthermore, changes in the color parameters (L*, a*, b*) revealed that the drink became considerably darker and lost its reddish and yellowish hues during this period. These data alone do not allow us to determine the optimal fermentation time, but they suggest little difference between 24 and 48 hours. Therefore, we decided to perform a sensory analysis of the kefir to reach a more assertive conclusion.

3.1.2. Sensory Evaluation of the Fermented Beverage After 24 and 48 Hours

Table 6 presents the average scores obtained in the sensory analysis of the beverage after 24 and 48 hours in the first fermentation (F1). Both formulations were added with 50% whole grape juice and subjected to a second fermentation for 24 hours at 30°C to enhance flavor and carbonation of the beverage. In other words, the only difference between the two treatments is the time of the first fermentation (F1). The microbiological evaluation, conducted prior to sensory analysis, confirmed the absence of Enterobacteriaceae, ensuring the product

’s safety and suitability for sensory testing.

The sensory evaluation of the fermented beverages, the results of which are detailed in

Table 6, revealed a relevant finding for process optimization. No statistically significant differences (p > 0.05) were observed in the mean scores for color, aroma, flavor, carbonation, overall impression, and purchase intention between the 24- and 48-hour fermentation times. Acceptance scores for hedonic attributes ranged from 5.68 (Aroma) to 7.01 (Carbonation) on a scale of 1 to 9, indicating satisfactory acceptance in these aspects. The carbonation attribute received the highest score, indicating that the second fermentation under closed conditions produced an effervescent beverage that met the consumer

’s taste preferences.

Given the observed sensory equivalence and the absence of significant differences between fermentation times for all evaluated attributes, we chose to use 24 hours for initial fermentation (F1) throughout the experiments. This choice is justified from a process optimization perspective, as shorter processing times not only make production more technologically and economically viable by reducing operating costs such as energy and equipment use, but also accelerate the production cycle, allowing for a higher production volume in less time.

3.2. Choosing the Flavor of Fruit Juice Used to Flavor Water Kefir

Based on the previously optimized operating conditions for the first fermentation (6.5% sugar and 30°C), this study continued with the flavoring stage. To this end, the kefired water obtained in the first fermentation was added with 50% of different fruit juices (berries, pineapple, and grape), followed by a second fermentation conducted in a closed system at room temperature. The berries were strawberries, raspberries, and blueberries. A sensory analysis was performed to evaluate the acceptance and sensory perception of these flavored formulations, and the results are presented in

Table 7.

The comparative sensory evaluation of fermented beverages flavored with grape, berries, and pineapple juices, whose average scores are presented in

Table 7, revealed sensory profiles with some distinctions and similarities.

For the carbonation attribute, grape juice obtained the highest average (6.89), showing a statistically significant difference concerning berries juice (p < 0.05), while it did not differ from pineapple juice. This superior carbonation may be related to the composition of grape juice, specifically its balance between acidity and sweetness, which favors the production and retention of carbon dioxide during the second fermentation.

Regarding color, grape juice (6.18) obtained a statistically lower score (p < 0.05) when compared to pineapple juice (6.73). Berries juice (6.71) did not present a statistically significant difference to any of the other flavors for this attribute.

For the other attributes, aroma, flavor, and overall impression, no statistically significant differences were observed between the three flavors evaluated (p > 0.05). The average scores for these attributes ranged from 5.64 (pineapple aroma) to 6.50 (overall grape impression), indicating moderate to good acceptance by the evaluators for these characteristics.

The comparative sensory analysis of beverages flavored with different fruit juices (berries, pineapple, and grape) revealed more similarities than differences in sensory acceptance among the various flavors tested. There were also no significant differences in the microbiological analysis results (LAB).

Considering this sensory equivalence and that all preliminary tests were carried out with grape juice, combined with its competitive cost and greater availability in the market where the experiments were conducted, it was selected for the continued development of the beverage.

3.3. Determination of the Proportion of Grape Juice in the Formulation of Water Kefir

To optimize the beverage formulation, a blend design was developed using three components: kefired water, grape juice, and drinking water.

Table 8 presents the models obtained for the sensory analysis responses.

Mathematical models were fitted to describe the sensory analysis results for the different treatments. The regression models demonstrated an excellent fit to the experimental data, with coefficients of determination (R

2) ranging from 0.8433 to 0.9969. Using these models, the graphs shown in

Figure 2 were obtained.

The multivariate optimization of the beverage formulation, conducted using the Derringer and Suich [

25] desirability function, resulted in a maximum overall desirability of 0.9917 (

Figure 3). This value, extremely close to ideality (1.0), represents the equilibrium point where multiple sensory attributes (such as flavor and carbonation) and purchase intention were simultaneously maximized.

The optimization of the mixture design, as illustrated in

Figure 3, indicated a maximum overall desirability of 0.9917. This value, very close to the ideal desirability (1.0), was achieved with the pseudocomponent ratio of x

1 = 0.00, x

2 = 0.91, and x

3 = 0.09. In terms of real components, this combination is equivalent to 50% kefired water, 46.4% grape juice, and 3.6% water. This formulation represents the optimal equilibrium point identified by the model, where the balance of all sensory attributes and purchase intention was simultaneously maximized. Based on this optimized composition, the final product was prepared, followed by an evaluation of its physical and chemical stability during storage.

Based on the data obtained for an optimized formulation (50% kefired water, 46.4% grape juice, and 3.6% drinking water), an acceptance test was conducted, yielding a satisfactory sensory evaluation of the analyzed attributes, which validated the effectiveness of the optimization. The color received an average score of 5 (“indifferent”), suggesting potential for visual improvement. However, the aroma, flavor, and carbonation received scores between 6 and 7, corresponding to “slightly liked” and “moderately liked,” respectively. The overall impression was also rated as “moderately liked.” Purchase intention varied, with a predominance of responses between “probably would buy” and “maybe would buy,” reflecting intermediate to positive consumer acceptance, which highlights the opportunity to improve the product’s color to further increase visual desirability.

Based on the data obtained, a standard formulation was established, as presented in

Table 9.

3.4. Stability of Water Kefir During Storage

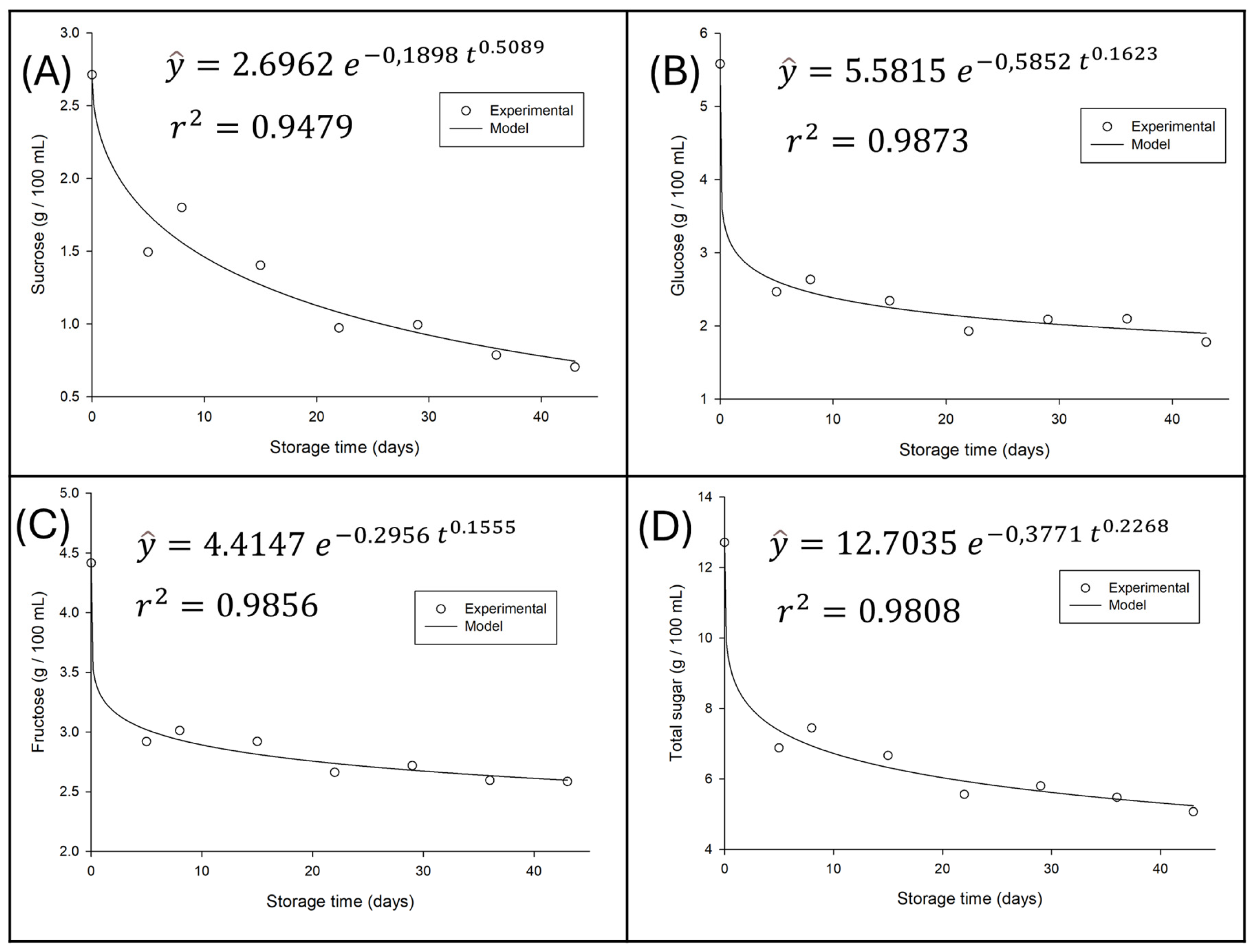

3.4.1. Variation in Sugar Content of Water Kefir During Refrigerated Storage

Using the optimized data, grape-flavored water kefir was prepared and its stability monitored for 42 days of refrigerated storage at 4°C, with samples collected at days 0, 7, 14, 28, 35, and 42. The variation in sugar content over this period, as well as the models adjusted for this variation and their respective coefficients of determination (R

2), are illustrated in

Figure 4.

A progressive and significant reduction in the concentration of all sugars is observed as storage time increases, indicating continued residual metabolic activity; that is, fermentation continues, albeit at a slower rate. It is essential to note that the curves fitted by the model exhibit an excellent fit to the experimental data, thereby validating the representativeness of the observed trends.

Individual sugar analysis corroborates microbial selectivity. The rapid decrease in sucrose can be attributed to the action of hydrolytic enzymes (such as invertases) produced by microorganisms, which convert it into glucose and fructose, making them available for consumption [

28]. Glucose, in turn, was shown to be the monosaccharide preferentially consumed, showing the steepest decrease. This preference for glucose over fructose is a metabolic pattern frequently observed in water kefir fermentations and other microbial systems [

8], where glucose is metabolized more efficiently, while fructose tends to persist in higher concentrations or be consumed more slowly, as also evidenced in the results of this study.

The total sugars curve, which represents the sum of the individual concentrations, reflects the general consumption trend, decreasing from an initial concentration of approximately 12.5 g/100 mL to approximately 5.0 g/100 mL after 40 days. Most of this loss occurred in the first 10–20 days of storage, with the degradation rate decreasing thereafter, consistent with first-order kinetics, where the reaction rate is proportional to the substrate concentration.

These results suggest that, although primary and secondary fermentation have been completed, the utilization of sugars during refrigerated storage continues, which can directly impact the perception of sweetness and the sensory characteristics of the beverage over time.

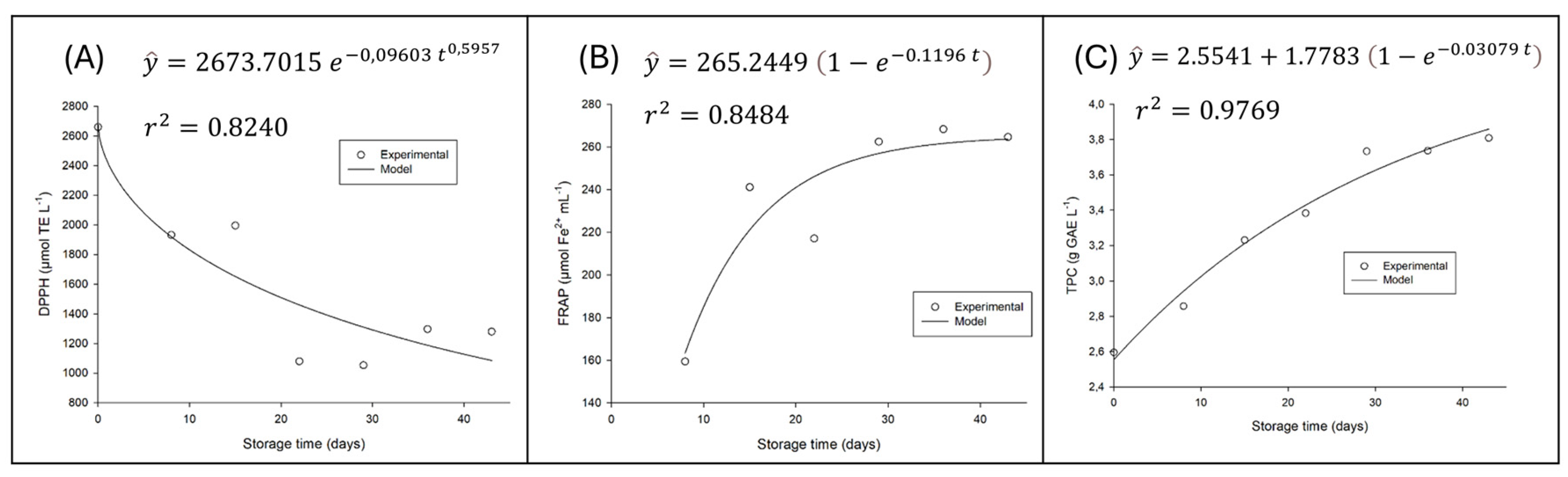

3.4.2. Variation in Antioxidant Capacity and Phenolic Compound Content of Water Kefir During Refrigerated Storage

For ABTS values, there was no significant variation over storage time (p > 0.05). On the other hand, there was significant variation (p < 0.05) for the antioxidant capacity value measured by the DPPH and FRAP methods; as well as for the content of phenolic compounds as illustrated in

Figure 5.

Figure 5 comprehensively illustrates the variation in Total Phenolic Compound (TPC) content and antioxidant activity over the 42 days of refrigerated storage (4°C) of the fermented beverage. The graph also displays the adjusted mathematical models, which, as shown in the figure, present an excellent fit to the experimental data.

The increase in Total Phenolic Compounds and FRAP activity is a significant and unexpected finding. It may be directly related to the fermentation processes of microorganisms with potential probiotic properties and the transformations that occur in the matrix during storage. Grape juice fermentation with probiotics, such as that involved in the production of this beverage, is known to increase total phenolic content. Probiotic bacteria have the ability to degrade tannins and produce compounds with a high content of free hydroxyl groups, which enhances phenolic content and antioxidant activity [

29]. This biotransformation can release bound phenolic compounds, making them more accessible and reactive to assays such as the Folin-Ciocalteu (TPC) and FRAP, which measures the reduction capacity of ferric ions [

30].

Despite the increase in TPC and FRAP, the decrease in free radical scavenging activity (DPPH) is a behavior that, although seemingly paradoxical, is explainable by the complexity of the antioxidant profile. It is possible that the original antioxidant compounds or specific forms that have a high affinity for the DPPH radical are more susceptible to oxidative degradation or polymerization reactions during storage [

31]. Even if new phenolic compounds are formed (resulting in increased TPC and FRAP), they may not have the same efficacy in the DPPH assay, but rather a greater electron-donating capacity, being more active in the FRAP assay. The dynamics of phenolic compounds are influenced by several chemical reactions that can occur during aging, where some phenolics degrade while others remain stable, such as gallic acid [

32].

The stability of ABTS activity suggests that the beverage maintains a general electron-donating/radical-scavenging capacity, perhaps through less specific compounds or mechanisms that are not as impacted by the transformations observed in DPPH. The diversity of microorganisms present [

8,

28] and the composition of the grape matrix itself contribute to this complexity and the multifaceted behavior of antioxidant capacity [

30].

Thus, the results indicate a favorable evolution of the beverage

’s antioxidant functionality, with the fermentation and storage processes promoting the formation or release of compounds that increase the total phenolic content and antioxidant reducing power. The particularity of the DPPH reduction highlights that different assays evaluate different aspects of antioxidant activity, and that the beverage undergoes a rearrangement of its bioactive profile, which is overall beneficial to health [

33].

3.4.3. Variation in Water Kefir Microorganism Count During Refrigerated Storage

Assessing the population dynamics of microorganisms during refrigerated storage is crucial for understanding the stability and maintenance of the functional characteristics of fermented beverages such as water kefir. It is essential to note that, at zero storage time, the beverage has already undergone two fermentation phases: 24 hours for the first fermentation and, subsequently, another 24 hours for the second fermentation. This process ensures that microbial populations are already at or near their maximum growth rate, typically in the stationary or initial decline phase, rather than in the exponential growth phase.

Regarding the Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB) count, the results of this study indicate that there was no significant variation over the refrigerated storage time (p > 0.05). The average count of these bacteria remained at 3.78 × 107 CFU/mL in the beverage.

This stability of the LAB population is a positive indicator, since maintaining high LAB counts is essential to ensure the health benefits associated with kefir consumption. Comparing this result with the literature, it is observed that the count obtained is in line with the expected levels for fermented water kefir products. For example, Gökırmaklı et al. [

34] reported Lactobacillus sp. counts in water kefir ranging from 5.18 to 7.71 log CFU/mL (equivalent to 1.5 x 10

5 to 5.1 x 10

7 CFU/mL) in fig-based media, and L. acidophilus at similar levels. The mean count of 3.78 × 10

7 CFU/mL in the present study (approximately 7.58 log CFU/mL) falls within the upper range or is slightly above the values reported in the literature for lactic acid bacteria in water kefir-related products, thereby reinforcing the quality and probiotic potential of the developed beverage. Almeida [

11] observed lactic acid bacteria counts in the range of 5.42 to 6.71 log CFU/mL during the fermentation stage and 7.17 ± 0.43 log CFU/g in the feed solution before drying, values that also align with the high microbial viability achieved in this work.

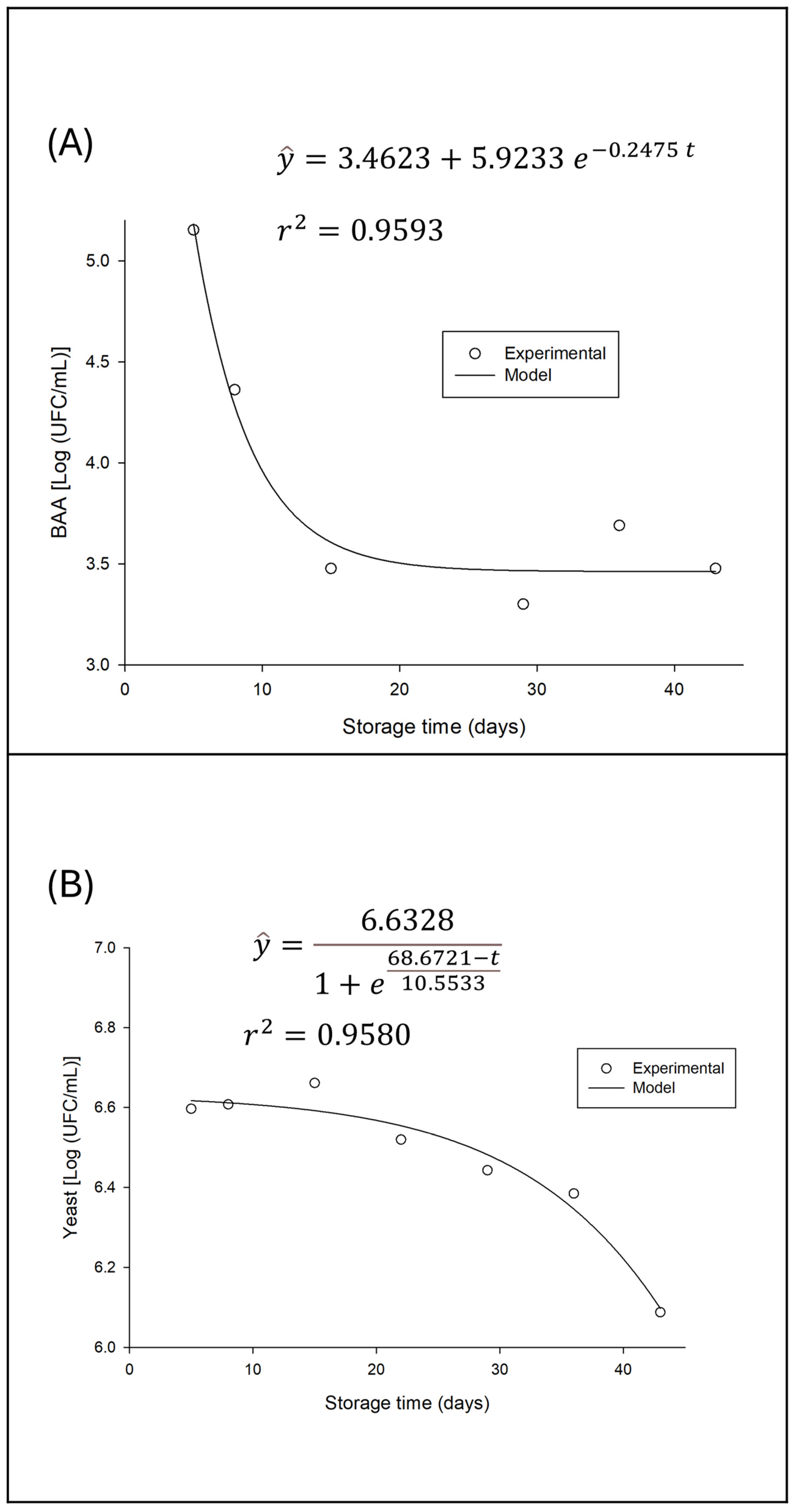

In contrast to lactic acid bacteria, the variation in acetic acid bacteria counts with storage time was significant, demonstrating a decline over time. This behavior is illustrated in

Figure 6, where the population decay and the fit of an exponential model for this variation are observed.

The observed decrease in acetic acid bacteria (AAB) counts during refrigerated storage, as shown in

Figure 6, is a result that aligns with the characteristic metabolism of these microorganisms and the storage conditions. Acetic acid bacteria, such as those of the genera Acetobacter and Gluconobacter, are typically aerobic, meaning they depend on the presence of oxygen to carry out their main metabolic activities, such as the oxidation of ethanol to acetic acid and of sugars to gluconic acid [

28,

34].

Considering that the beverage, after both fermentations, was stored under refrigerated conditions in hermetically sealed bottles, oxygen availability becomes a critical limiting factor. The reduction in available oxygen in the environment leads to a decrease in the metabolic activity of AAB, and consequently, their inactivation and gradual death, resulting in the observed population decline, modeled by an exponential curve. This is a striking difference compared to lactic acid bacteria, which have anaerobic or facultatively anaerobic metabolism and are therefore less affected by the absence of oxygen.

Although direct comparative studies of AAB counts over storage time in water kefir are scarce, the initial presence of these bacteria in fermented beverages is well documented. Almeida [

11], for example, detected acetic acid bacteria in their water kefir samples, with counts ranging from 5.04 to 5.75 log CFU/g, representing the starting point for the AAB population at zero storage time. The decline from these initial levels, as evidenced in the present study, is a direct reflection of post-fermentation storage conditions.

The decrease in the AAB population has sensory and chemical implications for the beverage. Acetic acid is one of the main contributors to the characteristic flavor and aroma of water kefir, imparting a pungent acidity (Gökırmaklı et al., 2023). If this characteristic acetic acid level is too high, it can cause sensory rejection of the product. Additionally, the inactivity of AAB under anoxic conditions can contribute to the stabilization of the beverage’s alcohol content, since ethanol oxidation, one of its primary functions, is inhibited. The decrease in AAB in a closed refrigerated environment can be seen as a natural control mechanism that prevents overacidification and the excessive production of undesirable volatile compounds over shelf life.

The yeast population dynamics during refrigerated storage of water kefir exhibit a distinct pattern, which differs from both the stability of lactic acid bacteria and the decline of acetic acid bacteria. The initial impression of the results points to a stationary phase of the yeast population after the two initial fermentations, followed by a period of decline (

Figure 6—B).

According to the process history, the beverage at storage time zero has already completed two fermentation stages (24 h of F1 and 24 h of F2), which suggests that the yeast population has already reached or is close to its maximum growth peak. In other words, the yeast entered storage already in a plateau phase, where the growth rate balances with the cell death rate, or a transitional phase toward decline, reflecting post-fermentation metabolic and environmental conditions.

In the early stationary phase, yeasts, having consumed the most easily assimilated substrates and produced metabolites such as ethanol and organic acids during fermentations, reach maximum population density. At this point, nutrient limitation and the accumulation of byproducts may begin to inhibit further growth. Gökırmaklı et al. (2023) observed that yeast counts in sugar- and fig-based water kefir peaked after 24 hours of fermentation, with values ranging from 5.89 to 6.16 log CFU/mL, before a slight decline between 24 and 48 hours. Almeida [

11] also reported yeast counts ranging from 5.03 to 5.65 log CFU/g.

Subsequently, the yeast population enters a decline phase. This phenomenon can be attributed to several factors, including nutrient depletion and low storage temperatures, accumulation of inhibitory metabolites, cellular lysis and senescence, among others [

28,

35].

3.4.4. Variation of pH Value, Soluble Solids and Alcohol Content over Time During Refrigerated Storage

During the 42-day storage period, there was no significant difference (p > 0.05) in relation to the pH value and alcohol content. The average pH value was 3.30, and the average alcohol content was 1.86% GL.

pH stability is an important indicator of both the quality and safety of fermented beverages over time, reflecting residual metabolic activity and product preservation. In the present study, analysis of water kefir beverages during 42 days of refrigerated storage revealed no variations over time in pH or alcohol content (p > 0.05). The average pH value for this period remained at 3.30.

Achieving and maintaining a low pH, such as 3.30, is an important factor in ensuring the microbiological safety of fermented beverages, as it creates an unfavorable environment for the growth of most pathogenic microorganisms [

14]. This value is well below the critical limit of 4.5, commonly accepted as a barrier to pathogen development, and is consistent with the value found in other stages of the experiment.

Laureys [

8] reported pH values ranging from approximately 3.34 to 3.47 after 48 to 192 hours of fermentation in different water kefir formulations. Therefore, the pH value of 3.30 found in the present study is in line with the lower values observed by these authors. On the other hand, Almeida [

11], in a study on powdered water kefir, reported pH values ranging from 3.88 to 4.30 during the first fermentation, which differs from the present work.

Beyond safety concerns, pH has a direct impact on the flavor profile. Lower pH values, such as 3.30, indicate higher acidity, resulting in a more sour taste [

36]. This acidity intensity can influence overall acceptance; for example, kefir with a pH of 3.37 was considered less preferred compared to slightly higher pH options [

36].

The pH stability during storage, along with the maintenance of the alcohol content (1.86 °GL), corroborates observations made on the dynamics of microbial populations. The stable population of lactic acid bacteria, combined with the decline of acetic acid bacteria and yeasts (as discussed previously), results in reduced metabolic activity, preventing significant fluctuations in acid and ethanol production.

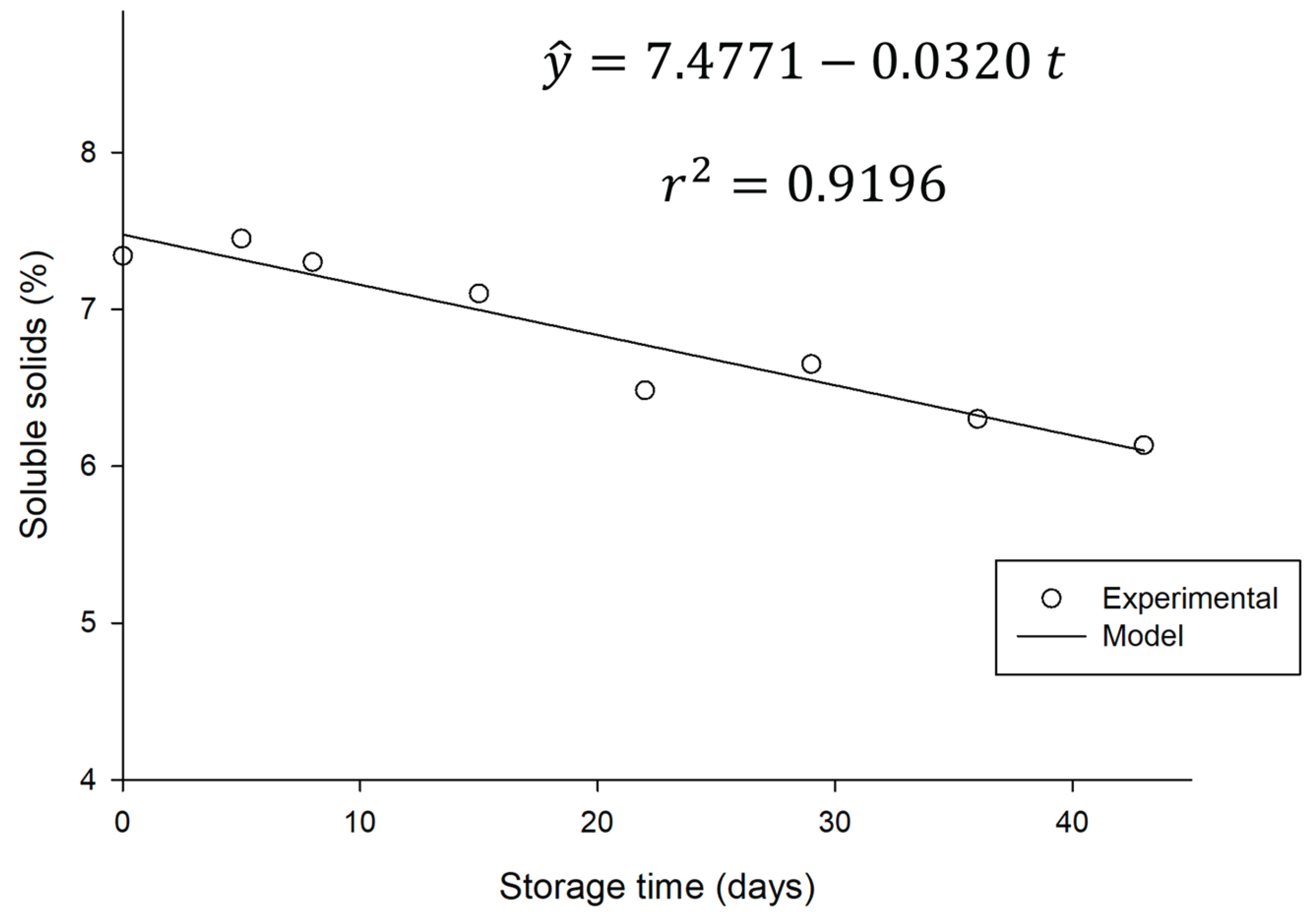

On the other hand, there was a significant variation (p<0.05) in the total soluble solids during storage time as illustrated in

Figure 7.

This decrease in TSS is directly related to the consumption of sugars present in the beverage by residual microorganisms, as shown in

Section 3.4.1 and

Figure 4, where a reduction in sugar levels is observed. Most of the soluble solids in water kefir are composed of sugars, which serve as the primary substrate for the active microbial population, indicating the continuity of residual metabolic activity; that is, fermentation continues, albeit slowly.

This trend is consistent with the specialized literature. Esatbeyoglu et al. (2023) observed a reduction in TSS values and sugar conversion, accompanied by a decrease in total sugars, glucose, and fructose, when studying water kefir produced from aronia (Esatbeyoglu et al., 2023). Complementarily, Pendón et al. (2022) explained the fundamental process of sucrose consumption by yeast (with hydrolysis into glucose and fructose) and the subsequent use of these monosaccharides by lactic and acetic bacteria during water kefir fermentation. Although at a slower rate due to the low temperature, this residual metabolic activity is primarily responsible for the decrease in sugars and, consequently, in soluble solids.

It is worth noting that, despite the reduction in soluble solids content and sugar consumption, there was no significant difference in the pH value or alcohol content of the beverage during refrigerated storage. This suggests that residual sugars were primarily used by microorganisms for maintenance metabolism and cell survival, as well as for processes that do not result in significant production of additional acids or ethanol. Beverages can form a buffer system, allowing the pH to remain relatively stable even with small acid production.

4. Conclusions

The results obtained allowed the establishment of process and formulation parameters that contribute to the production of a beverage with desirable characteristics and functional potential, meeting the objective of developing and optimizing a fermented water kefir-based beverage flavored with grape juice and naturally carbonated, as well as evaluating its physicochemical, microbiological, and sensory stability during refrigerated storage. The data obtained from this study enabled the definition of suitable conditions for producing a beverage with relevant sensory and functional attributes.

Analysis of the first fermentation (F1) revealed that the pH acidification kinetics follow a modified exponential model, influenced by temperature and soluble solids content. The selection of Treatment T6 (6.5% brown sugar at 30°C) and the 24-hour initial fermentation time were justified by the combination of efficient acidification achieving safe pH values and the absence of significant differences in sensory attributes between 24 and 48 hours of fermentation.

In the flavoring stage, grape juice was chosen because it effectively enhanced the beverage composition, with sensory acceptance comparable to that of other flavors tested, and notable carbonation. The application of mixture design and desirability function enabled the determination of the optimized formulation, composed of 50% kefired water, 46.4% grape juice, and 3.6% drinking water.

During refrigerated storage (4°C for 42 days), a progressive reduction in sugar (sucrose, glucose, and fructose) levels was observed, demonstrating continued residual metabolic activity. The beverage’s antioxidant capacity demonstrated dynamic behavior, with increases in total phenolic compounds and FRAP activity, and stability in ABTS activity, while DPPH activity decreased. The lactic acid bacteria population remained stable at significant levels, reinforcing the beverage’s probiotic potential over time. In contrast, acetic acid bacteria and yeast counts declined, indicating that oxygen and nutrient limitations were present. The stability of pH and alcohol content during storage is an important indicator of microbiological safety and the maintenance of product quality.

Although water kefir is often characterized as a low-alcohol beverage, the average values of 1.86 °GL observed during storage indicate the need to declare the alcohol content on the product label. This requirement aligns with current regulations for similar fermented beverages. It is essential to provide adequate information to consumers with specific restrictions on alcohol consumption, such as nursing mothers and drivers.

The objective of this study was achieved, with advances in knowledge about the production of flavored and naturally carbonated water kefir. However, gaps in knowledge were identified that warrant further research. It is recommended that subsequent studies explore strategies for reducing the beverage’s alcohol content, aiming to expand its applicability to niche markets with restrictions on alcohol consumption. Additionally, a deeper understanding of microbial dynamics and interactions with metabolites produced during storage is essential to better understand the product’s stability and functional characteristics.

Author Contributions

Samarha Pacheco Wichello: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing—original draft preparation. Kamila Ferreira Chaves: Validation, Writing—review & editing. Wallaf Costa Vimercati: Validation, Writing—review & editing. Sergio Henriques Saraiva: Formal analysis, Methodology. Luciano Jose Quintão Teixeira: Data curation, Conceptualization, Writing—review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

All authors have contributed substantially to the work reported. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa e Inovação do Espírito Santo (FAPES, Brazil), under grant numbers TO: 420/2025 and TO: 245/2025. Additional funding was provided by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq, Brazil), grant number 306063/2022-0.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Espírito Santo (UFES) (opinion number 6.479.574).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the sensory analysis, and the study received ethical approval from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Espírito Santo (UFES) (opinion number 6.479.574).

Data Availability Statement

The data are contained within this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Postgraduate Program in Food Science and Technology at the Federal University of Espírito Santo (UFES) for their valuable support in conducting this work, and the Department of Food Engineering at UFES for providing the necessary infrastructure.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| F1 |

Fist Fermentation |

| F2 |

Second Fermentation |

| LAB |

Lactic Acid Bacteria |

| AAB |

Acetic Acid Bacteria |

| TSS |

Total Soluble Solids |

| HPLC |

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography |

References

- Sundararaman, A., Ray, M., Ravindra, P. V., & Halami, P. M. (2020). Role of probiotics to combat viral infections with emphasis on COVID-19. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 104(19), 8089–8104. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C. L. L. (2018). Prebióticos e probióticos: Atualização e prospecção (2a ed.). Rubio.

- Gulitz, A., Stadie, J., Wenning, M., Ehrmann, M. A., & Vogel, R. F. (2011). The microbial diversity of water kefir. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 151(3), 284–288. [CrossRef]

- Fels, L., Jakob, F., Vogel, R. F., & Wefers, D. (2018). Structural characterization of the exopolysaccharides from water kefir. Carbohydrate Polymers, 189, 296–303. [CrossRef]

- Garrote, G. L., Abraham, A. G., & Antoni, G. L. de. (2001). Chemical and microbiological characterisation of kefir grains. Journal of Dairy Research, 68(4), 639–652. [CrossRef]

- Esatbeyoglu, T., Fischer, A., Legler, A. D. S., Oner, M. E., Wolken, H. F., Köpsel, M., Ozogul, Y., Özyurt, G., De Biase, D., & Ozogul, F. (2023). Physical, chemical, and sensory properties of water kefir produced from Aronia melanocarpa juice and pomace. Food Chemistry: X, 18, 100683. [CrossRef]

- Fuentes Jaime, C. E., Ramos, G. G., & Sancho, R. A. S. (2023). Propriedades do fermentado kefir de água em diferentes substratos alimentares. Revista Perspectiva, 46(6), 69–83. [CrossRef]

- Laureys, D., Aerts, M., Vandamme, P., & Vuyst, L. de. (2018). Oxygen and diverse nutrients influence the water kefir fermentation process. Food Microbiology, 73, 351–361. [CrossRef]

- Zannini, E., Lynch, K. M., Nyhan, L., Sahin, A. W., O’Riordan, P., Luk, D., & Arendt, E. K. (2023). Influence of substrate on the fermentation characteristics and culture-dependent microbial composition of water kefir. Fermentation, 9(1), 28. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, M. L. P., de Souza, A. C., Costa Júnior, P. S. P., Veríssimo, L. A. A., Pylro, V. S., Dias, D. R., & Schwan, R. F. (2022). Sugary kefir grains as the inoculum for developing a low sodium isotonic beverage. Food Research International, 157, 111257. [CrossRef]

- Almeida, K. V. de, Zanetti, V. C., Camelo-Silva, C., Alexandre, L. A., da Silva, A. C., Verruck, S., & Teixeira, L. J. Q. (2024). Powdered water kefir: Effect of spray drying and lyophilization on physical, physicochemical, and microbiological properties. Food Chemistry Advances, 5, Article 100759. [CrossRef]

- Zongo, O., Cruvellier, N., Leray, F., Bideaux, C., Lesage, J., Zongo, C., Traoré, Y., Savadogo, A., & Guillouet, S. (2020). Physicochemical composition and fermentation kinetics of a novel palm sap-based kefir beverage from the fermentation of Borassus aethiopum Mart. fresh sap with kefir grains and ferments. Scientific African, 10, e00631. [CrossRef]

- Araújo, C. S., Macedo, L. L., & Teixeira, L. J. Q. (2023). Use of mid-infrared spectroscopy to predict the content of bioactive compounds of a new non-dairy beverage fermented with water kefir. LWT, 176, 114514. [CrossRef]

- Jay, J. M., Loessner, M. J., & Golden, D. A. (2005). Modern food microbiology (7th ed.). Springer.

- Arapović, M., Puljić, L., Kajić, N., Banožić, M., Kartalović, B., Habschied, K., & Mastanjević, K. (2024). The impact of production techniques on the physicochemical properties, microbiological, and consumer’s acceptance of milk and water kefir grain-based beverages. Fermentation, 10(1), 2. [CrossRef]

- Brasil. (2009). Decreto nº 6.871, de 4 de junho de 2009. Diário Oficial da União, Seção 1, p. 3.

- Brasil. Ministério da Agricultura, Pecuária e Abastecimento. (2007). Instrução Normativa n. 46, de 23 de outubro de 2007. Aprova o regulamento técnico de identidade e qualidade de leites fermentados. Diário Oficial da União, Seção 1, p. 5.

- Brasil. (2019). Instrução Normativa n°41, de 17 de setembro de 2019. Estabelece o padrão de identidade e qualidade da kombucha em todo território nacional. https://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/instrucao-normativa-n41-de-17-de-setembro-de-2019-216803534.

- Tran, T., Grandvalet, C., Verdier, F., Martin, A., Alexandre, H., & Tourdot-Maréchal, R. (2020). Microbiological and technological parameters impacting the chemical composition and sensory quality of kombucha. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 19(4), 2050–2070. [CrossRef]

- Tzavaras, D., Papadelli, M., & Ntaikou, I. (2022). From milk kefir to water kefir: Assessment of fermentation processes, microbial changes and evaluation of the produced beverages. Fermentation, 8(3), 135. [CrossRef]

- Laureys, D., & Vuyst, L. de. (2017). The water kefir grain inoculum determines the characteristics of the resulting water kefir fermentation process. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 122(3), 719–732. [CrossRef]

- Bravim, D. G., Oliveira, T. M., Rosário, D. K. A., Batista, N. N., Schwan, R. F., Coelho, J. M., & Bernardes, P. C. (2023). Inoculation of yeast and bacterium in wet-processed Coffea canephora. Food Chemistry, 400, 134107. [CrossRef]

- Stone, H., & Sidel, J. L. (2004). Sensory evaluation practices (3rd rev. ed.). Academic Press.

- Freitas, R. B., Silva, V. N. H., Maia, V. T., Santos, O. B., Calvette, Y. M. A., & Fiaux, S. B. (2020). Low-cost device to measure concentration of Saccharomyces cerevisiae through methylene blue reduction. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement, 69(5), 2232–2238. [CrossRef]

- Derringer, G. C., & Suich, R. C. (1980). Simultaneous optimization of several response variables. Journal of Quality Technology, 12(4), 214–219. [CrossRef]

- Maldonade, I. R., Carvalho, P. G. B., & Ferreira, N. A. (2013). Protocolo para determinação de açúcares totais em hortaliças pelo método de DNS. Embrapa. [CrossRef]

- Silva, N., Junqueira, V. C. A., Silveira, N. F. A., Taniwaki, M. H., Gomes, R. A. R., Okazaki, M. M., & Iamanaka, B. T. (2010). Manual de métodos de análise microbiológica de alimentos. Editora Blucher.

- Breselge, S., Skibinska, I., Yin, X., Brennan, L., Kilcalwley, K., Cotter, P. D. (2025). The core microbiomes and associated metabolic potential of water kefir as revealed by pan multi-omics. Communications Biology, 8, 415. [CrossRef]

- Khanniri, E., Sohrabvandi, S., Mortazavian, A. M., Khorshidian, N., & Malganji, S. (2018). Effect of fermentation, cold storage and carbonation on the antioxidant activity of probiotic grape beverage. Current Nutrition & Food Science, 14(4), 335–340. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L., Li, G., Cui, L., Cai, R., Yuan, Y., Gao, Z., Yue, T., & Wang, Z. (2024). The health benefits of fermented fruits and vegetables and their underlying mechanisms. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 23(6), e70072. [CrossRef]

- Rocha-Parra, D. F., Lanari, M. C., Zamora, M. C., & Chirife, J. (2016). Influence of storage conditions on phenolic compounds stability, antioxidant capacity and colour of freeze-dried encapsulated red wine. LWT, 70, 162–170. [CrossRef]

- Panceri, C. P., & Bordignon-Luiz, M. T. (2017). Impact of grape dehydration process on the phenolic composition of wines during bottle ageing. Journal of Food Biochemistry, 41(6), 12417. [CrossRef]

- Manjunatha, V., Bhattacharjee, D., & Flores, C. (2024). Unlocking innovations: Exploring the role of kefir in product development. Current Food Science and Technology Reports, 2(2), 221–230. [CrossRef]

- Gökırmaklı, Ç., Yüceer, Y. K., & Guzel-Seydim, Z. B. (2023). Chemical, microbial, and volatile changes of water kefir during fermentation with economic substrates. European Food Research and Technology, 249(7), 1717–1728. [CrossRef]

- Daval, C., Tran, T., Verdier, F., Martin, A., Alexandre, H., Grandvalet, C., & Tourdot-Maréchal, R. (2024). Identification of key parameters inducing microbial modulation during backslopped kombucha fermentation. Foods, 13(8), 1181. [CrossRef]

- Binici, H. İ., Özdemir, C., & Özdemir, S. (2023). The physical, chemical, sensory properties and aromatic organic substance profile of kefir added citrus fruits in different proportions. Tekirdağ Ziraat Fakültesi Dergisi, 20(4), 871–878. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Fermentation Kinetics: variation in pH value as a function of fermentation time for the different treatments.

Figure 1.

Fermentation Kinetics: variation in pH value as a function of fermentation time for the different treatments.

Figure 2.

Result of the sensory acceptance test according to the proportion of kefired water, grape juice, and drinking water.

Figure 2.

Result of the sensory acceptance test according to the proportion of kefired water, grape juice, and drinking water.

Figure 3.

Result of the desirability function applied to the scores obtained in the sensory analysis.

Figure 3.

Result of the desirability function applied to the scores obtained in the sensory analysis.

Figure 4.

Variation in sugar content: Sucrose (A); glucose (B); fructose (C); total sugars (D) as a function of storage time refrigerated at 4°C.

Figure 4.

Variation in sugar content: Sucrose (A); glucose (B); fructose (C); total sugars (D) as a function of storage time refrigerated at 4°C.

Figure 5.

Variation in antioxidant capacity: DPPH (A); FRAP (B), phenolic compound content (C) over the refrigerated storage period.

Figure 5.

Variation in antioxidant capacity: DPPH (A); FRAP (B), phenolic compound content (C) over the refrigerated storage period.

Figure 6.

Variation in the microorganism count (A): AAB and (B) Yeast throughout refrigerated storage at 4°C.

Figure 6.

Variation in the microorganism count (A): AAB and (B) Yeast throughout refrigerated storage at 4°C.

Figure 7.

This result is consistent with the chemical changes expected in fermented beverages with residual metabolic activity. Although stored refrigerated, some reactions continue to occur, as this beverage contains living microorganisms.

Figure 7.

This result is consistent with the chemical changes expected in fermented beverages with residual metabolic activity. Although stored refrigerated, some reactions continue to occur, as this beverage contains living microorganisms.

Table 1.

Experimental Planning Matrix for the Central Composite Rotational Design (CCRD).

Table 1.

Experimental Planning Matrix for the Central Composite Rotational Design (CCRD).

| Variables |

Minimum Level (%) |

Maximum Level (%) |

| Temperature (ºC) |

20 |

30 |

| Soluble Solids (SS) |

3 |

10 |

| Essay |

X1 (Coded temperature) |

X2 (coded SS) |

Temperature (ºC) |

TSS (ºBRIX) |

| 1 |

-1 |

-1 |

21.5 |

4.0251 |

| 2 |

-1 |

1 |

21.5 |

8.9749 |

| 3 |

1 |

-1 |

28.5 |

4.0251 |

| 4 |

1 |

1 |

28.5 |

8.9749 |

| 5 |

-1.4142 |

0 |

20 |

6.5 |

| 6 |

1.4142 |

0 |

30 |

6.5 |

| 7 |

0 |

-1.4142 |

25 |

3 |

| 8 |

0 |

1.4142 |

25 |

10 |

| 9 |

0 |

0 |

25 |

6.5 |

| 10 |

0 |

0 |

25 |

6.5 |

| 11 |

0 |

0 |

25 |

6.5 |

Table 2.

Mixture Design Matrix (MDE) for choosing formulation proportions.

Table 2.

Mixture Design Matrix (MDE) for choosing formulation proportions.

| Variables |

Minimum Level (%) |

Maximum Level (%) |

| Kefired water |

50 |

90 |

| Fruit juice |

10 |

50 |

| Drinking water |

0 |

40 |

| Treatment |

Pseudocomponents |

Components |

| x1 |

x2 |

x3 |

Kefir (%) |

Juice (%) |

Water (%) |

| 1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

90 |

10 |

0 |

| 2 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

50 |

50 |

0 |

| 3 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

50 |

10 |

40 |

| 4 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0 |

70 |

30 |

0 |

| 5 |

0.5 |

0 |

0.5 |

70 |

10 |

20 |

| 6 |

0 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

50 |

30 |

20 |

| 7 |

1/3 |

1/3 |

1/3 |

63.3333 |

23.3333 |

13.3333 |

| 8 |

2/3 |

1/6 |

1/6 |

76.6667 |

16.6667 |

6.6667 |

| 9 |

1/6 |

2/3 |

1/6 |

56.6667 |

36.6667 |

6.6667 |

| 10 |

1/6 |

1/6 |

2/3 |

56.6667 |

16.6667 |

26.6667 |

Table 3.

Adjusted equations and coefficients of determination (R2) for the different treatments tested.

Table 3.

Adjusted equations and coefficients of determination (R2) for the different treatments tested.

| Treatment |

Adjusted equations |

R2 |

| T1 |

|

0.9954 |

| T2 |

|

0.9798 |

| T3 |

|

0.9776 |

| T4 |

|

0.9759 |

| T5 |

|

0.9957 |

| T6 |

|

0.9902 |

| T7 |

|

0.9866 |

| T8 |

|

0.9908 |

| T9 |

|

0.9851 |

| T10 |

|

0.9890 |

| T11 |

|

0.9831 |

Table 4.

pH value after 24 and 48 hours of fermentation.

Table 4.

pH value after 24 and 48 hours of fermentation.

|

Treatment

|

Initial pH (A)

|

pH (24 h)

|

pH (48 h)

|

| T1 |

5.51 |

4.27 |

3.75 |

| T2 |

5.55 |

4.38 |

3.87 |

| T3 |

5.55 |

3.95 |

3.32 |

| T4 |

5.55 |

4.16 |

3.56 |

| T5 |

5.56 |

4.55 |

4.13 |

| T6 |

5.04 |

3.85 |

3.37 |

| T7 |

4.69 |

3.79 |

3.39 |

| T8 |

5.00 |

3.97 |

3.52 |

| T9 |

5.02 |

3.95 |

3.51 |

| T10 |

4.97 |

3.93 |

3.48 |

| T11 |

5.01 |

3.95 |

3.50 |

Table 5.

Physical, physicochemical and microbiological parameters of the fermented beverage after 24 and 48 hours of fermentation.

Table 5.

Physical, physicochemical and microbiological parameters of the fermented beverage after 24 and 48 hours of fermentation.

| Physicochemical parameters |

24 h |

48 h |

| Total soluble solids (ºBrix) |

7.77a |

7.63a |

| pH |

3.66a |

3.65a |

| Alcohol content (ºGL) |

0.73a |

0.75a |

| Total sugars (%) |

1.80a |

1.30b |

| Reducing sugars (%) |

1.4a |

1.0b |

| Lactic acid bacteria (log UFC) |

7.13a |

7.44b |

| Enterobacteria |

Absence |

Absence |

| Color L* |

4.15a |

2.30b |

| Color a* |

12.87a |

7.27b |

| Color b* |

7.01a |

3.89b |

Table 6.

Result of the sensory evaluation of the fermented beverage at 24 and 48 hours of fermentation.

Table 6.

Result of the sensory evaluation of the fermented beverage at 24 and 48 hours of fermentation.

| Sensory attributes |

24 h |

48 h |

| Color |

5.98a |

6.13a |

| Aroma |

5.70a |

5.68a |

| Flavor |

6.25a |

6.27a |

| Carbonation |

7.01a |

6.90a |

| Overall impression |

6.45a |

6.52a |

Table 7.

Average sensory scores for the different attributes evaluated and different flavors.

Table 7.

Average sensory scores for the different attributes evaluated and different flavors.

| Attributes |

Berries |

Pineapple |

Grape |

| Color |

6.72 ab |

6.73 a |

6.18 b |

| Aroma |

5.86 a |

5.64 a |

5.65 a |

| Flavor |

6.28 a |

6.06 a |

6.21 a |

| Carbonation |

6.17 b |

6.54 ab |

6.89 a |

| Overall impression |

6.33 a |

6.14 a |

6.50 a |

| Microbiology |

|

|

|

| 1—Lactic acid bacteria |

1.04 x107 a |

5.9 x 107 a |

1.4 x 107 a |

| 2—Enterobacteriaceae |

Absent |

Absent |

Absent |

Table 8.

Regression models adjusted for the results of the sensory analysis according to the proportion of kefired water, grape juice, and drinking water.

Table 8.

Regression models adjusted for the results of the sensory analysis according to the proportion of kefired water, grape juice, and drinking water.

| Variable |

Adjusted model |

R2

|

| Color |

|

0.9038 |

| Aroma |

|

0.8433 |

| Flavor |

|

0.9940 |

| Carbonation |

|

0.9580 |

| Overall impression |

|

0.9881 |

| Purchase intention |

|

0.9969 |

Table 9.

Operational parameters and formulation used in the production of naturally grape-flavored water kefir.

Table 9.

Operational parameters and formulation used in the production of naturally grape-flavored water kefir.

| Parameters |

F1 |

F2 |

| Type of fermentation |

Open |

Closed |

| Fermentation time |

24 h |

24 h |

| Temperature |

30°C |

30°C |

| Added sugar |

6.5 % |

na |

| Quantity of grains |

5% |

na |

| Kefired water |

na |

50% |

| Grape juice |

na |

46.40% |

| Drinking water |

Complete 100% |

3.60% |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).