Submitted:

14 July 2023

Posted:

17 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw materials

2.2. Sample preparation and pasteurization

2.3. Sensory analysis

2.4. Physico-chemical determinations

2.4.1. Brix, pH, acidity, and density

2.4.2. Particle size

2.4.3. Colour measurement

2.5. Analysis of volatile compounds by ITEX/GS-MS

2.6. Statistical analysis

3. Results and Discussions

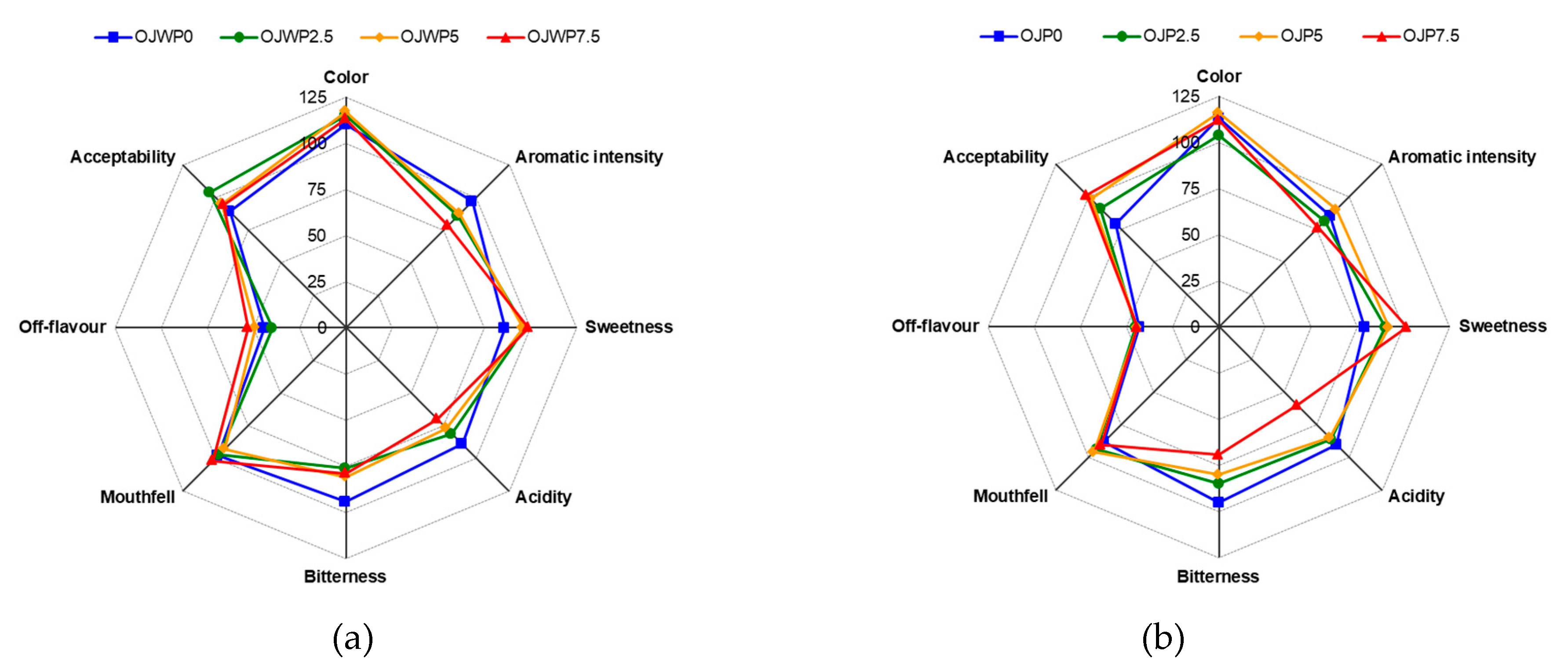

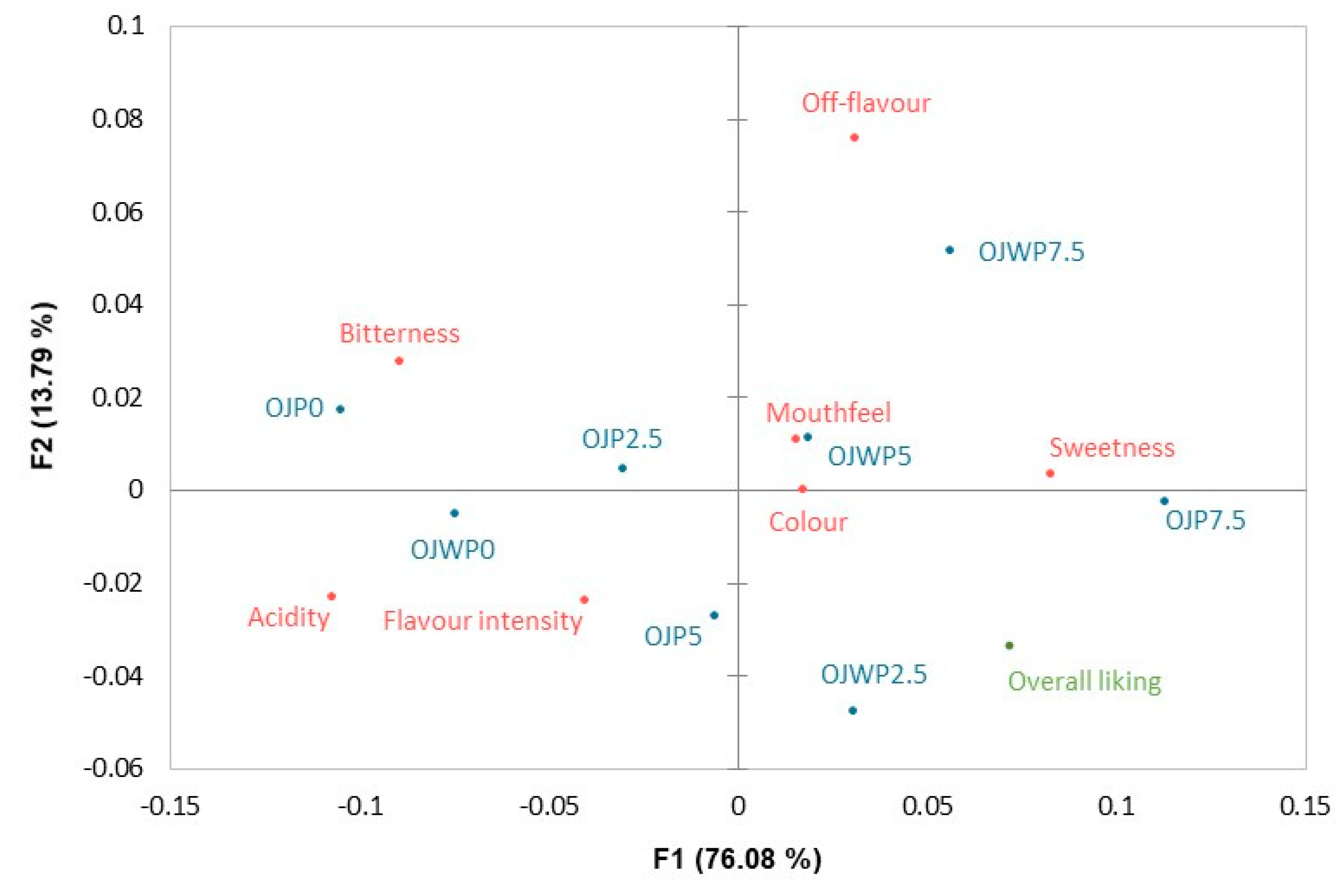

3.1. Sensory evaluation

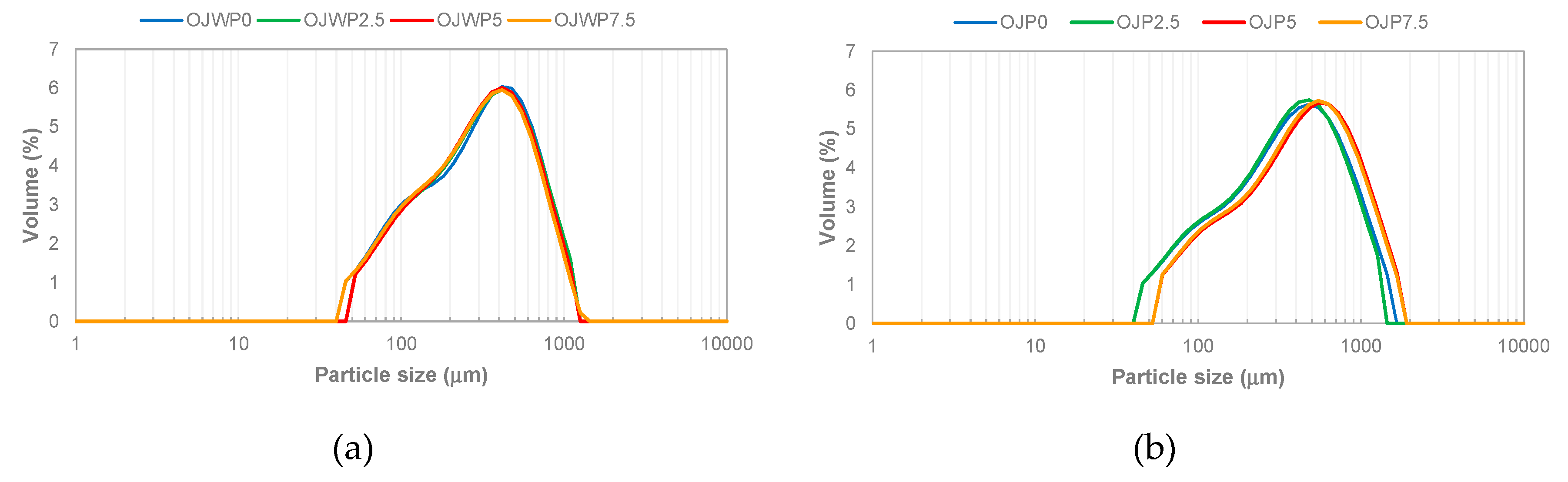

3.2. Physico-chemical properties

3.3. Aromatic profile

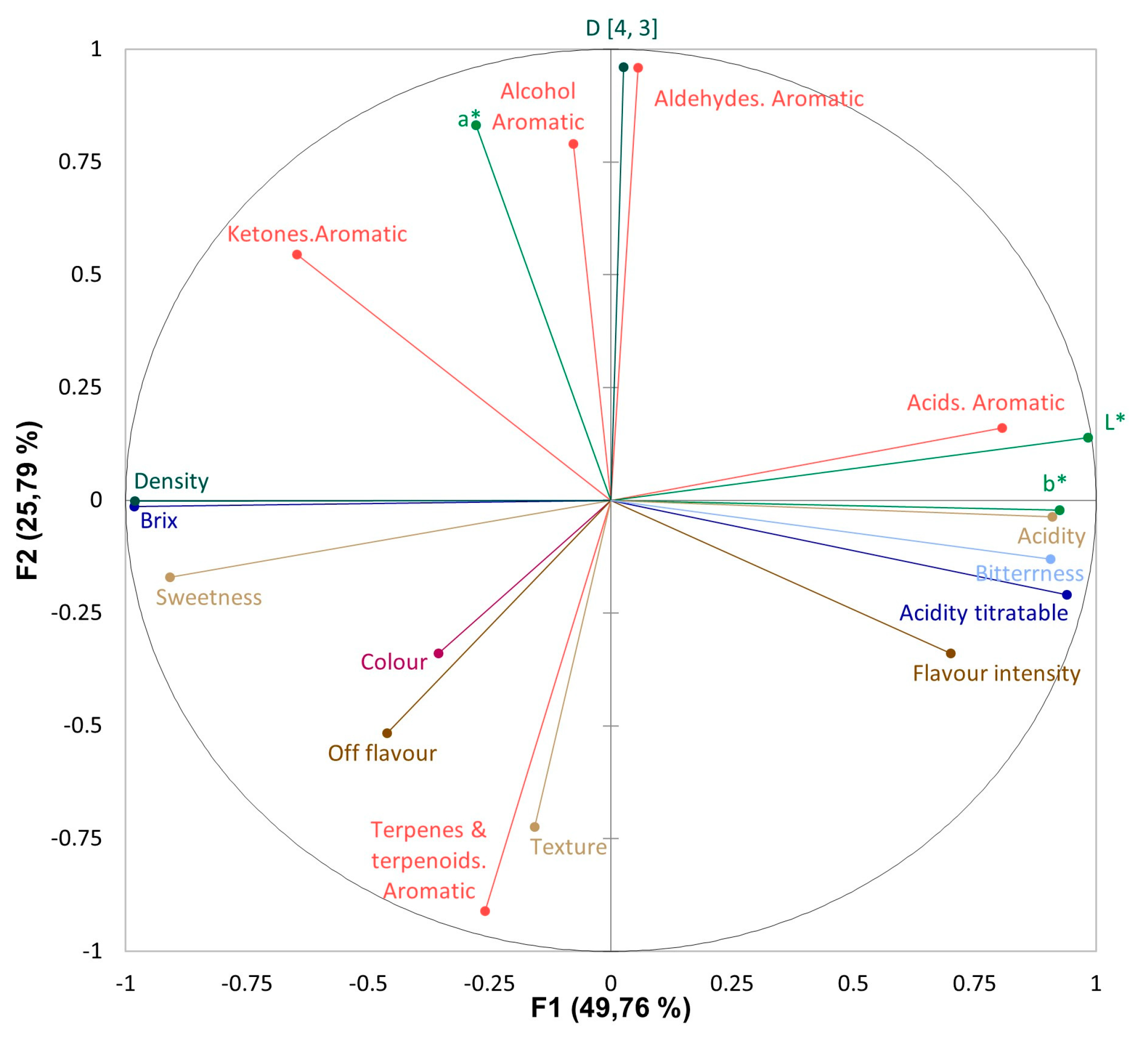

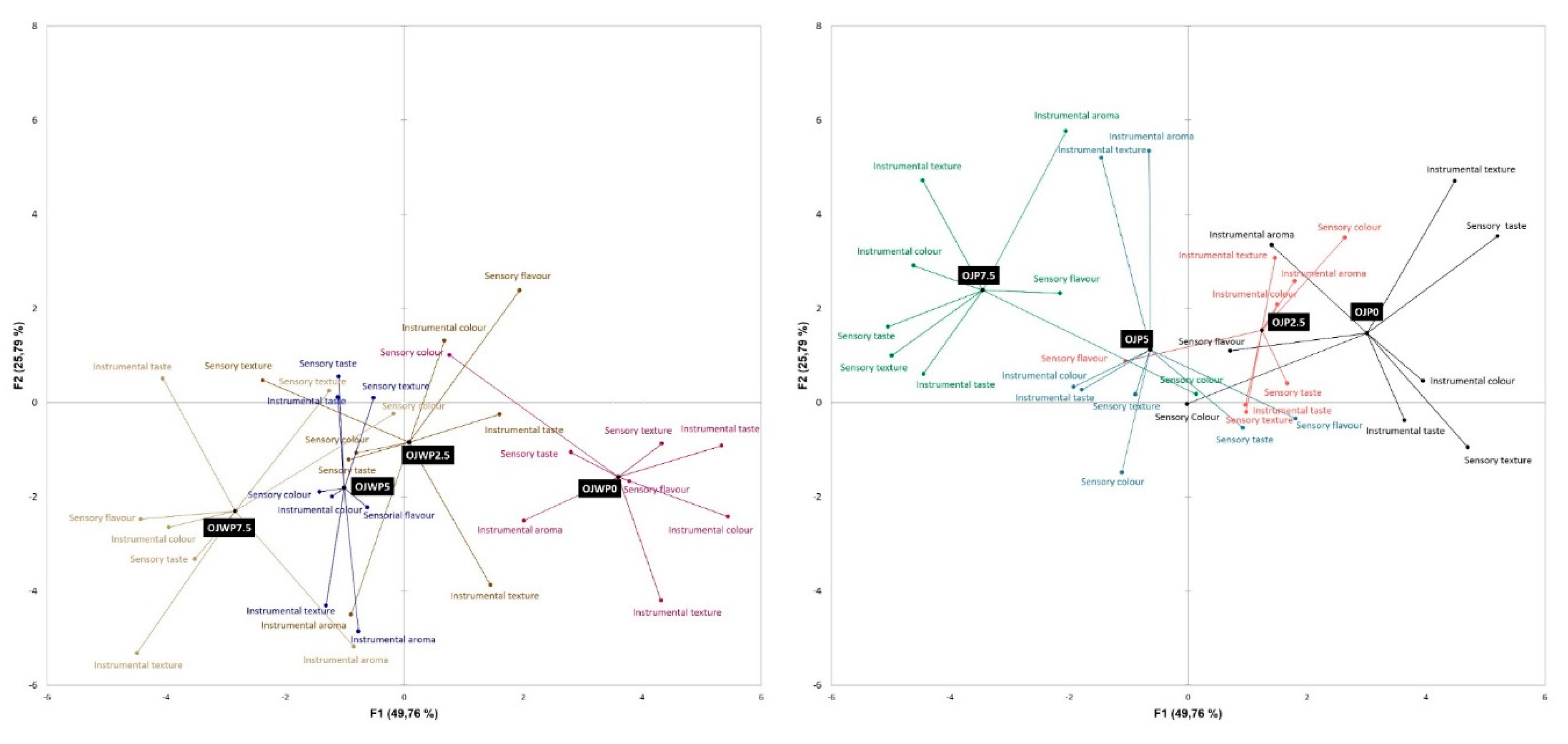

3.4. Instrumental and sensorial correlations

3.3. Aromatic profile

3.3. Instrumental and sensorial correlations

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Karelakis, C.; Zevgitis, P.; Galanopoulos, K.; Mattas, K. Consumer trends and attitudes to functional foods. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2020, 32, 266–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, G.R., Scott, K.P.; Rastall, R.A., Tuohy, K.M.; Hotchkiss, A.; Dubert-Ferrandon, A.; Gareau, M.; Eileen, F.M.; Saulnier, D.; Loh, G.; Macfarlane, S.; Delzenne, N.; Ringel, Y.; Kozianowski, G.; Dickmann, R.; Lenoir-Wijnkoop, I.; Walker, C.; Buddington, R. Dietary prebiotics: Current status and new definition. Food Sci. Technol. Bull. Funct. Foods 2010, 7, 1–19.

- Gibson, G.R.; Probert, H.M.; Loo, J.V.; Rastall, R.A.; Roberfroid, M.B. Dietary modulation of the human colonic microbiota: updating the concept of prebiotics. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2004, 17, 259–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corzo, N.; Alonso, J.L.; Azpiroz, F.; Calvo, M.A.; Cirici, M.; Leis, R.; Lombó, F.; Mateos-Aparicio, I.; Plou, F.J.; Ruas-Madiedo, P.; Rúperez, P.; Redondo-Cuenca, A.; Sanz, M.L.; Clemente, A. Prebiotics: Concept, properties and beneficial effects. Nutr. Hosp. 2015, 31, 99–118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Lockyer S, Nugent AP. Health effects of resistant starch. Nutr. Bull. 2017, 42, 10–41. [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Arumugam, V.; Haugabrooks, E.; Williamson, P.; Hendrich S. Soluble dietary fiber (Fibersol-2) decreased hunger and increased satiety hormones in humans when ingested with a meal. Nutr. Res. 2015, 35, 393–400. [CrossRef]

- 7. Livesey G, Tagami H. Interventions to lower the glycemic response to carbohydrate foods with a low-viscosity fiber (resistant maltodextrin): meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 89, 114–125. [CrossRef]

- Kishimoto, Y.; Oga, H.; Hayashi, N.; Yamada, T.; Tagami, H. Suppressive effect of resistant maltodextrin on postprandial blood triacylglycerol elevation. Eur. J. Nutr. 2007, 46, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, D.J.; Stote, K.S.; Henderson, T.; Paul, D.R.; Okuma, K.; Tagami, H.; Kanahori, S.; Gordon, D.T.; Rumpler, W.V.; Ukhanova, M.; Culpepper, T.; Wang, X.; Mai, V. The metabolizable energy of dietary resistant maltodextrin is variable and alters fecal microbiota composition in adult men. J. Nutr. 2014, 144, 1023–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshini A, Priyadarshini A. Market dimensions of the fruit juice industry. In: Fruit Juices: Extraction, Composition, Quality and Analysis. Rajauria, G., Tiwari B.K., Eds. Elsevier, London, UK, 2018, pp. 15-32.

- Day, L.; Seymour, R.B.; Pitts, K.F.; Konczak, I.; Lundin, L. Incorporation of functional ingredients into foods. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2009, 20, 388–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonteles Vidal, T.; Rodrigues, S. Prebiotic in fruit juice: Processing challenges, advances, and perspectives. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2018, 22, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, M.F.; Trombin, V.G.; Marques, V.N.; Martinez, L.F. Global orange juice market: a 16-year summary and opportunities for creating value. Trop. Plant Pathol. 2020, 45, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Perez-Cacho, P.; Rouseff, R.L Processing and storage effects on orange juice aroma: A review. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 9785–9796. [CrossRef]

- Roberfroid, M.; Gibson, G,R.; Hoyles, L.; McCartney, A.L.; Rastall, R.; Rowland I.; Wolvers, D.; Watzl, B.; Szajewska, H.; Stahl, B.; Guarner, F.; Respondek, F.; Whelan, K.; Coxam, V.; Davicco, M-J.; Léotoing, L.; Wittrant, Y.; Delzenne, N.M.; Cani, P.D.; Neyrinck, A.M.; Meheust, A. Prebiotic effects: metabolic and health benefits. Br. J. Nutr. 2010, 104 Suppl 2, S1–S63.

- Luckow, T.; Delahunty, C. Consumer acceptance of orange juice containing functional ingredients. Food Res. Int. 2004, 37, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 4121:2003. Sensory analysis - Guidelines for the use of quantitative response scales.

- Latimer, G.W.; AOAC International. Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International, 19th ed., AOAC International, Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2012; Volume 2.

- ISO 13320:2020. Particle Size Analysis-Laser Diffraction Methods.

- Commission Internationale de l’Eclairage (CIE). Colorimetry, 2nd Edition. Publication CIE No. 15.2. Austria, Vienna, 1986.

- Igual, M.; Chiş, M.S.; Socaci, S.A.; Vodnar, D.C.V.; Ranga, F.; Martínez-Monzó, J.; García-Segovia, P. Effect of Medicago sativa Addition on Physicochemical, Nutritional and Functional Characteristics of Corn Extrudates. Foods 2021, 10, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Pherobase Database of Pheromones and Semiochemicals. Available online: https://www.pherobase.com/ (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- Flavornet and Human Odor Space. Available online: http://www.flavornet.org/ (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- Lumivero, XLSTAT statistical and data analysis solution 2023. Available online: https://www.xlstat.com/en (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Rega, B.; Fournier, N.; Nicklaus, S.; Guichard, E. Role of pulp in flavor release and sensory perception in orange juice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 4204–4212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasena, V.; Cameron, I. °Brix/acid ratio as a predictor of consumer acceptability of Crimson Seedless table grapes. J. Food Qual. 2008, 31, 736–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luckow, T.; Delahunty, C. Consumer acceptance of orange juice containing functional ingredients. Food Res. Int. 2004, 37, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimball, D.A. Citrus Processing: Quality Control and Technology. Springer Science & Business Media, New York, NY, USA, 2012.

- AIJN-European Fruit Juice Association. Orange Juice Guideline. Available online: https://aijn.eu/en/publications/aijn-papers-guidelines/juice-quality (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Arilla, E.; Igual, M.; Martínez-Monzó, J.; Codoñer-Franch, P.; García-Segovia, P. Impact of Resistant Maltodextrin Addition on the Physico-Chemical Properties in Pasteurized Orange Juice. Foods 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arilla, E.; García-Segovia, P.; Martínez-Monzó, J.; Codoñer-Franch, P.; Igual, M. Effect of Adding Resistant Maltodextrin to Pasteurized Orange Juice on Bioactive Compounds and Their Bioaccessibility. Foods 2021, 10, 1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arilla, E.; Martínez-Monzó, J., Codoñer-Franch P., García-Segovia, P., Igual, M. Stability of vitamin C, carotenoids, phenols, and antioxidant capacity of pasteurised orange juice with resistant maltodextrin storage. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2022 (in press). [CrossRef]

- Ghavidel, R.A.; Karimi, M.; Davoodi, M.; Jahanbani, R.; Asl, A.F.A. Effect of fructooligosaccharide fortification on quality characteristic of some fruit juice beverages (apple & orange juice). Intl. J. Farm. Alli. Sci. 2014, 3, 141–146. [Google Scholar]

- Braga, H.F.; Conti-Silva, A.C. Papaya nectar formulated with prebiotics: Chemical characterization and sensory acceptability. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 62, 854–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, T.C.; Madrona, G.S., Prudencio, S.H. Probiotic clarified apple juice with oligofructose or sucralose as sugar substitutes: Sensory profile and acceptability. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 62, 838–846. [CrossRef]

- De Paulo Farias, D.; de Araújo, F.F. , Neri-Numa, I.A.; Pastore, G.M. Prebiotics: Trends in food, health and technological applications. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 93, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibowo, S.; Grauwet, T.; Santiago, J.S.; Tomic, J.; Vervoort, L.; Hendrickx, M.; Van Loey, A. Quality changes of pasteurized orange juice during storage: A kinetic study of specific parameters and their relation to colour instability. Food Chem. 2015, 187, 140–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, A.M.; Ibarz, A. Density of juice and fruit puree as a function of soluble solids content and temperature. J. Food Eng. 1998, 3, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarz, A.; Miguelsanz, R. Variation with temperature and soluble solids concentration of the density of a depectinised and clarified pear juice. J. Food Eng. 1989, 10, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saifullah, M.; Shishir, M.R.I.; Ferdowsi, R.; Rahman, M.R.T.; Van Vuong, Q. Micro and nano encapsulation, retention and controlled release of flavor and aroma compounds: A critical review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 86, 230–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, M.J.; Goodner, K.L.; Laencina, J. Deaeration and pasteurization effects on the orange juice aromatic fraction. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2003, 36, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibowo, S.; Vervoort, L.; Tomic, J.; Santiago, J.S.; Lemmens, L.; Panozzo, A.; Grauwet, T.; Hendrickx, M.; Van Loey, A. Colour and carotenoid changes of pasteurised orange juice during storage. Food Chem. 2015, 171, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibowo, S.; Grauwet, T.; Kebede, B.T.; Hendrickx, M.; Van Loey, A. Study of chemical changes in pasteurised orange juice during shelf-life: A fingerprinting-kinetics evaluation of the volatile fraction. Food Res. Int. 2015, 75, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelebek, H.; Selli, S. Determination of volatile, phenolic, organic acid and sugar components in a Turkish cv. Dortyol (Citrus sinensis L. Osbeck) orange juice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 91, 1855–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Perez-Cacho, P.; Rouseff, R.L. Fresh squeezed orange juice odor: a review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2008, 48, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brat, P.; Rega, B.; Alter, P.; Reynes, M.; Brillouet, J.M. Distribution of volatile compounds in the pulp, cloud, and serum of freshly squeezed orange juice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 3442–3447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellami, I.; Mall, V.; Schieberle, P. Changes in the Key Odorants and Aroma Profiles of Hamlin and Valencia Orange Juices Not from Concentrate (NFC) during Chilled Storage. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 7428–7440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Averbeck, M.; Schieberle, P.H. Characterisation of the key aroma compounds in a freshly reconstituted orange juice from concentrate. Eur Food Res.Technol. 2009, 229, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bylaite, E.; Meyer, A.S. Characterisation of volatile aroma compounds of orange juices by three dynamic and static headspace gas chromatography techniques. Eur. Food Res.Technol. 2006, 22, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlinet, C.; Guichard, E.; Fournier, N.; Ducruet, V. Effect of Pulp Reduction and Pasteurization on the Release of Aroma Compounds in Industrial Orange Juice. J. Food Sci. 2007, 72, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schalow, S.; Baloufaud, M.; Cottancin, T.; Fischer, J.; Drusch, S. Orange pulp and peel fibres: pectin-rich by-products from citrus processing for water binding and gelling in foods. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2018, 244, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, A.D.; Jensen, S.L.; Ziegler, G.; Pandeya. A.; Buléon, A.; Svensson, B.; Blennow, A. Structural and physical effects of aroma compound binding to native starch granules. Starch-Stärke 2012, 64, 461–469. [CrossRef]

- Singla, V.; Chakkaravarthi, S. Applications of prebiotics in food industry: A review. Food Sci Technol Int 2017, 23, 649–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madene, A.; Jacquot, M.; Joël, S.; Desobry, S. Flavour encapsulation and controlled release - A review. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2006, 41, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garmarini, M.V., Van Baren, C., Zamora, M.C., Chirife, J., Di Leo Lira, P., Bandoni, A., Impact of trehalose, sucrose and/or maltodextrin addition on aroma retention in freeze dried strawberry puree. Int. J. Food Sci.Technol. 2011, 46, 1337–1345. [CrossRef]

- Siccama, J.W.; Pegiou, E.; Zhang, L.; Mumm, R.; Hall, R.D.; Boom, R.M.; Schutyser, M.A.I. Maltodextrin improves physical properties and volatile compound retention of spray-dried asparagus concentrate, LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 142, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Ćorković, I.; Pichler, A.; Šimunović, J.; Kopjar, M. Hydrogels: Characteristics and application as delivery systems of Phenolic and aroma compounds. Foods 2021, 10, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Willige, R.W.G.; Linssen, J.P.H.; Legger-Huysman, A.; Voragen, A.G.J. Influence of flavour absorption by food-packaging materials (low-density polyethylene, polycarbonate and polyethylene terephthalate) on taste perception of a model solution and orange juice. Food Addit. Contam. 2003, 20, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | °Brix | pH | Acidity | L* | a* | b* | ΔE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OJWP0 | 12.3 (0.2)d | 3.67 (0.02)b | 0.920 (0.002)a | 40.68 (0.13)a | -1.54 (0.13)d | 29.6 (0.3)a | - |

| OJWP2.5 | 14.4 (0.2)c | 3.67 (0.02)b | 0.882 (0.002)c | 37.89 (0.16)d | -1.29 (0.07)bc | 28.70 (0.07)c | 2.95 (0.13)e |

| OJWP5 | 16.5 (0.2)b | 3.67 (0.02)b | 0.861 (0.002)e | 36.80 (0.12)e | -1.48 (0.09)d | 27.4 (0.4)d | 4.5 (0.2)c |

| OJWP7.5 | 18.7 (0.2)a | 3.67 (0.02)b | 0.838 (0.002)g | 35.12 (0.02)g | -1.51 (0.02)d | 26.43 (0.12)e | 6.41 (0.05)a |

| OJP0 | 12.2 (0.2)d | 3.70 (0.02)a | 0.891 (0.002)b | 40.13 (0.10)b | -1.35 (0.12)c | 29.4 (0.4)ab | - |

| OJP2.5 | 14.4 (0.2)c | 3.68 (0.02)b | 0.872 (0.002)d | 38.84 (0.13)c | -1.240 (0.002)ab | 28.76 (0.15)bc | 1.46 (0.07)f |

| OJP5 | 16.5 (0.2)b | 3.71 (0.02)a | 0.849 (0.002)f | 37.9 (0.3)d | -1.350 (0.014)c | 26.5 (1.2)e | 3.7 (0.5)d |

| OJP7.5 | 18.8 (0.2)a | 3.68 (0.02)b | 0.832 (0.002)h | 35.69 (0.13)f | -1.16 (0.05)a | 26.5 (0.5)e | 5.3 (0.2)b |

| Sample | D[4,3] | d(0.1) | d(0.5) | d(0.9) | Density |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OJWP0 | 302 (13)cd | 25.6 (1.6)c | 245 (10)cd | 665 (30)c | 1.0487 (0.0002)g |

| OJWP2.5 | 307 (4)c | 26.1 (1.2)c | 247 (5)c | 677 (8)c | 1.0575 (0.0003)f |

| OJWP5 | 299 (14)cd | 23 (2)e | 242 (11)cd | 657 (31)c | 1.0659 (0.0009)d |

| OJWP7.5 | 286 (12)d | 19.9 (1.2)f | 230 (9)d | 632 (28)c | 1.0757 (0.0004)b |

| OJP0 | 427 (26)ab | 43 (3)ab | 332 (18)ab | 963 (66)a | 1.0487 (0.0005)g |

| OJP2.5 | 410 (37)b | 41 (4)b | 324 (29)b | 916 (87)b | 1.0579 (0.0002)e |

| OJP5 | 433 (20)a | 41 (3)ab | 339 (18)a | 974 (47)a | 1.0670 (0.0003)c |

| OJP7.5 | 427 (25)ab | 44 (4)a | 335 (20)ab | 957 (62)ab | 1.0762 (0.0007)a |

| Alcohols | OJWP0 | OJWP2.5 | OJWP5 | OJWP7.5 | OPJ0 | OPJ2.5 | OPJ5 | OPJ7.5 | Odor perception |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-Octanol | 0,09(0,03)bc | 0,11(0,03)bc | 0,07(0,03)c | 0,07(0,01)c | 0,21(0,02)a | 0,22(0,02)a | 0,18(0,01)a | 0,11(0,02)b | citrus |

| 3-methyl-1-Butanol, | 0,07(0,02)b | 0,06(0,02)bc | 0,06(0,03)bc | 0,07(0,02)b | 0,16(0,02)a | 0,02(0,01)d | 0,03(0,02)cd | citrus | |

| 2-methyl- 1-Butanol | 0,04(0,02)b | 0,35(0,02)a | whiskey, malt, burnt | ||||||

| 1-Terpinen-4-ol | 0,69(0,02)c | 0,60(0,02)d | 0,57(0,02)d | 0,49(0,02)e | 1,03(0,02)a | 0,88(0,02)b | 0,87(0,02)b | 0,94(0,02)b | malty |

| cis-p-Mentha-2,8-dien-1-ol | 0,13(0,02)c | 0,16(0,03)bc | 0,15(0,02)bc | 0,17(0,02)b | 0,14(0,02)bc | 0,28(0,02)a | 0,25(0,02)a | turpentine, nutmeg, must | |

| 2-Cyclohexen-1-ol, 2-methyl-5-(1-methylethenyl)-, cis- // cis-Carveol | 0,34(0,03)bc | 0,24(0,02)d | 0,29(0,04)c | 0,31(0,02)c | 0,23(0,02)d | 0,12(0,02)e | 0,39(0,02)a | 0,37(0,02)ab | fresh, minty |

| 2-Cyclohexen-1-ol, 2-methyl-5-(1-methylethenyl)-, trans- // trans-Carveol | 0,08(0,02)bc | 0,06(0,01)cd | 0,07(0,02)bc | 0,03(0,02)d | 0,03(0,02)d | 0,11(0,01)ab | 0,12(0,02)a | Caraway, Spicy, Citrus, Fruity | |

| Total | 1,19(0,10)d | 1,26(0,15)d | 1,25(0,16)d | 1,16(0,11)d | 1,83(0,12)b | 1,41(0,11)c | 2,18(0,10)a | 1,82(0,12)b | |

| Aldehydes | OJWP0 | OJWP2.5 | OJWP5 | OJWP7.5 | OPJ0 | OPJ2.5 | OPJ5 | OPJ7.5 | Odor perception |

| Dodecanal | 0,07(0,02)bc | 0,05(0,02)c | 0,06(0,02)c | 0,05(0,02)c | 0,12(0,02)a | 0,10(0,02)ab | 0,06(0,02)c | 0,12(0,02)a | cologne, violet, pine, chypre. |

| 2-Hexenal, (E)- | 0,09(0,02)c | 0,09(0,02)c | 0,08(0,03)cd | 0,09(0,02)c | 0,20(0,02)a | 0,05(0,02)d | 0,14(0,02)b | 0,16(0,02)b | green, leaf |

| Heptanal | 0,03(0,02)a | 0,05(0,02)a | 0,03(0,02)a | 0,04(0,02)a | 0,07(0,02)a | 0,06(0,02)a | Green, oily, fatty, cognac,almond | ||

| Undecanal | 0,04(0,03)a | 0,05(0,02)a | 0,04(0,02)a | 0,06(0,03)a | 0,08(0,02)a | 0,08(0,02)a | 0,08(0,02)a | 0,08(0,02)a | oil, pungent, sweet |

| Octanal | 7,27(0,04)d | 7,18(0,03)d | 6,97(0,04)e | 6,52(0,05)f | 8,23(0,04)c | 8,96(0,06)b | 9,20(0,04)a | 9,23(0,03)a | malty |

| Nonanal | 0,47(0,06)b | 0,34(0,03)cd | 0,36(0,02)cd | 0,43(0,04)bc | 0,63(0,03)a | 0,59(0,04)a | 0,59(0,02)a | 0,59(0,03)a | fat, citrus, green |

| Decanal | 1,64(0,03)d | 1,36(0,05)e | 1,43(0,03)e | 1,62(0,03)d | 2,83(0,03)a | 2,28(0,05)c | 2,43(0,03)b | 2,30(0,04)c | soap, orange peel, tallow |

| Total | 9,58(0,20)d | 9,10(0,19)e | 8,99(0,18)f | 8,8(0,21)g | 12,13(0,18)c | 12,13(0,23)c | 12,56(0,17)a | 12,48(0,16)b | |

| Terpenes and terpenoids | OJWP0 | OJWP2.5 | OJWP5 | OJWP7.5 | OPJ0 | OPJ2.5 | OPJ5 | OPJ7.5 | Odor perception |

| Camphene | 0,06(0,02)a | 0,04(0,03)a | 0,08(0,02)a | camphor, piney woody with terpy nuances | |||||

| β-Pinene | 0,49(0,02)c | 0,12(0,02)f | 0,25(0,03)d | 0,18(0,02)e | 0,62(0,03)b | 0,08(0,02)f | 0,62(0,04)b | 0,69(0,04)a | pine, resin, turpentine |

| Benzaldehyde | 0,08(0,02)a | 0,07(0,03)a | 0,06(0,02)a | 0,07(0,02)a | almond, burnt sugar | ||||

| β-Myrcene | 34,36(0,06)b | 34,88(0,18)a | 33,51(0,07)c | 32,49(0,08)d | 31,81(0,07)e | 31,17(0,10)f | 31,06(0,08)f | 31,00(0,12)f | balsamic, must, spice |

| Limonene | 34,18(0,04)c | 35,08(0,06)a | 34,87(0,06)b | 33,87(0,07)d | 23,02(0,10)f | 25,02(0,07)e | 23,16(0,09)f | 23,08(0,10)f | citrus, mint |

| β-cis-Ocimene | 0,86(0,02)c | 0,73(0,02)d | 0,71(0,02)d | 0,83(0,03)c | 1,05(0,04)b | 1,11(0,03)a | 1,06(0,03)ab | 1,03(0,03)b | citrus, herb, flower |

| α-Phellandrene | 0,06(0,02)ab | 0,03(0,01)b | 0,05(0,02)ab | 0,09(0,03)a | 0,07(0,03)ab | citrus, terpenic, green, woody | |||

| .gamma.-Terpinene | 1,98(0,02)e | 1,91(0,02)e | 1,97(0,04)e | 2,20(0,04)d | 2,89(0,07)bc | 3,08(0,05)a | 2,81(0,06)c | 2,97(0,05)ab | Sweet, citrus, woody, tropical fruits |

| Terpinolene | 0,11(0,02)b | 0,10(0,02)b | 0,11(0,02)b | 0,13(0,03)b | 0,21(0,02)a | 0,12(0,02)b | fresh, woody, sweet, pine, citrus | ||

| α-Pinene | 6,90(0,04)g | 6,37(0,03)h | 7,24(0,04)f | 7,82(0,06)e | 12,11(0,07)a | 10,27(0,06)d | 10,66(0,08)c | 11,36(0,08)b | pine, turpentine |

| β-Linalool | 0,64(0,02)e | 0,65(0,03)e | 0,61(0,02)e | 0,75(0,05)d | 0,53(0,05)f | 1,21(0,03)c | 1,53(0,03)b | 1,86(0,04)a | flower, lavender |

| (+)-4-Carene | 1,24(0,02)b | 1,05(0,03)b | 1,07(0,04)b | 1,26(0,03)b | 1,69(0,06)a | 1,78(0,05)a | 1,73(0,04)a | 1,27(0,03)b | lemon, resin |

| Benzene, 2-ethenyl-1,3-dimethyl- | 0,22(0,03)ab | 0,16(0,02)b | 0,22(0,03)ab | 0,22(0,03)ab | 0,27(0,03)a | 0,26(0,03)a | 0,23(0,03)a | 0,21(0,03)ab | not mentioned in literature |

| β-Terpineol | 0,03(0,03)e | 0,14(0,03)d | 0,03(0,02)e | 0,05(0,03)e | 0,13(0,02)d | 0,23(0,02)c | 0,57(0,03)b | 0,79(0,03)a | woody, piney, floral |

| α-Terpineol | 0,23(0,04)c | 0,19(0,03)cd | 0,15(0,03)de | 0,13(0,02)e | 0,33(0,02)b | 0,24(0,03)c | 0,40(0,02)b | 0,86(0,03)a | terpenic, oil, anise, mint |

| α-Citral | 0,19(0,02)a | 0,05(0,03)b | lemon, fruity, sweet | ||||||

| Copaene | 0,09(0,02)cd | 0,09(0,02)bcd | 0,06(0,03)d | 0,07(0,02)d | 0,19(0,03)a | 0,13(0,03)abc | 0,17(0,03)a | 0,15(0,04)ab | wood, spice |

| 1,3,8-p-Menthatriene | 0,11(0,02)ab | 0,06(0,03)b | 0,13(0,02)a | 0,13(0,02)a | 0,15(0,03)a | 0,16(0,03)a | 0,14(0,03)a | 0,16(0,02)a | Turpentine |

| Limonene epoxide | 0,14(0,03)a | 0,15(0,03)a | 0,14(0,03)a | 0,14(0,03)a | 0,14(0,03)a | 0,15(0,04)a | 0,20(0,03)a | 0,15(0,02)a | Fruit |

| Caryophyllene | 0,13(0,03)b | 0,13(0,03)b | 0,08(0,02)c | 0,10(0,02)bc | 0,25(0,03)a | 0,12(0,03)bc | 0,22(0,02)a | 0,20(0,02)a | Musty, green |

| α-Caryophyllene | 0,03(0,02)d | 0,08(0,02)cd | 0,08(0,02)cd | 0,08(0,02)cd | 0,12(0,03)abc | 0,13(0,03)ab | 0,17(0,03)a | 0,11(0,03)bc | Musty, green |

| β-Elemene | 0,05(0,02)d | 0,07(0,03)bcd | 0,06(0,03)cd | 0,11(0,02)abc | 0,12(0,03)ab | 0,13(0,03)a | 0,10(0,03)abcd | herb, wax, fresh | |

| Naphthalene, 1,2,3,5,6,7,8,8a-octahydro-1,8a-dimethyl-7-(1-methylethenyl)-, [1R-(1.alpha.,7.beta.,8a.alpha.)]- // Valencene | 1,33(0,03)f | 2,73(0,08)d | 2,42(0,05)e | 2,67(0,05)d | 4,12(0,08)b | 4,10(0,06)b | 4,29(0,07)a | 3,84(0,02)c | green, oil |

| 2-Cyclohexen-1-one, 2-methyl-5-(1-methylethenyl)-, (R)- // (-)-Carvone | 0,90(0,03)e | 1,00(0,03)d | 1,41(0,04)b | 1,80(0,05)a | 0,85(0,06)e | 0,29(0,04)f | 1,40(0,06)b | 1,21(0,02)c | Mint |

| 2-Cyclohexen-1-one, 3-methyl-6-(1-methylethenyl)-, (S)- | 0,16(0,03)e | 0,36(0,03)c | 1,04(0,03)b | 1,18(0,04)a | 0,08(0,02)f | 0,25(0,03)d | 0,12(0,03)ef | 0,17(0,02)e | spicy, carraway |

| Naphthalene, 1,2,3,5,6,8a-hexahydro-4,7-dimethyl-1-(1-methylethyl)-, (1S-cis)- // delta.-Cadinene | 0,10(0,03)e | 0,08(0,02)e | 0,08(0,02)e | 0,20(0,03)d | 0,32(0,03)bc | 0,36(0,03)ab | 0,41(0,03)a | 0,29(0,01)c | thyme, medicine, wood |

| (-)-α-Panasinsen | 0,21(0,03)a | 0,24(0,03)a | 0,23(0,04)a | 0,20(0,02)a | not mentioned in literature | ||||

| 2,6-Octadien-1-ol, 3,7-dimethyl-, acetate, (Z)- // Nerol acetate | 0,05(0,03)b | 0,05(0,03)b | 0,06(0,03)ab | 0,07(0,03)ab | 0,08(0,02)ab | 0,11(0,01)a | sweet, fruity and floral | ||

| 1-Cyclohexene-1-carboxaldehyde, 4-(1-methylethenyl)- | 0,04(0,03)d | 0,20(0,03)c | 0,12(0,03)c | 0,25(0,03)bc | 0,21(0,03)bc | 0,04(0,02)d | 0,37(0,04)a | 0,27(0,02)b | herbal, fresh, spicy |

| β-Citral | 0,03(0,03)a | 0,05(0,03)a | 0,06(0,03)a | 0,05(0,02)a | 0,06(0,02)a | 0,04(0,02)a | lemon | ||

| Total | 84,38(0,68)b | 86,31(0,82)a | 86,45(0,88)a | 86,74(0,90)a | 81,89(1,16)c | 81,07(1,08)c | 81,95(1,05)c | 82,19(0,80)c | |

| Ketones | OJWP0 | OJWP2.5 | OJWP5 | OJWP7.5 | OPJ0 | OPJ2.5 | OPJ5 | OPJ7.5 | Odor perception |

| Acetophenone | 0,04(0,02)c | 0,04(0,02)c | 0,04(0,02)c | 0,05(0,02)c | 0,06(0,03)c | 0,18(0,02)b | 0,53(0,03)a | must, flower, almond | |

| Ethanone, 1-(4-methylphenyl)- | 0,11(0,03)bc | 0,11(0,03)bc | 0,11(0,03)bc | 0,15(0,04)b | 0,06(0,03)c | 0,05(0,04)c | 0,18(0,04)b | 0,46(0,05)a | floral, sweet |

| Total | 0,11(0,03)c | 0,15(0,06)c | 0,15(0,05)c | 0,19(0,07)c | 0,11(0,05)c | 0,11(0,07)c | 0,36(0,06)b | 0,99(0,08)a | |

| Acids | OJWP0 | OJWP2.5 | OJWP5 | OJWP7.5 | OPJ0 | OPJ2.5 | OPJ5 | OPJ7.5 | Odor perception |

| Butanoic acid, methyl ester | 0,59(0,08)b | 0,04(0,01)d | 0,06(0,02)d | 0,06(0,02)d | 1,20(0,02)a | 0,10(0,02)cd | 0,07(0,02)d | 0,15(0,03)c | ether, fruit, sweet |

| Dodecanoic acid | 0,17(0,04)b | 0,14(0,02)b | 0,14(0,03)b | 0,13(0,03)bc | 0,07(0,02)c | 0,25(0,03)a | 0,26(0,04)a | 0,24(0,02)ab | soapy |

| Tetradecanoic acid | 0,61(0,08)a | 0,14(0,04)d | 0,27(0,01)c | 0,24(0,04)c | 0,14(0,04)d | 0,18(0,02)cd | 0,38(0,04)b | 0,24(0,03)c | waxy |

| Butanoic acid, ethyl ester | 1,89(0,07)c | 1,35(0,15)d | 1,37(0,04)d | 1,41(0,03)d | 2,33(0,07)b | 3,48(0,05)a | 1,95(0,06)c | 2,19(0,11)b | fruity, sweet |

| Acetic acid, octyl ester | 1,40(0,08)a | 0,78(0,03)b | 0,74(0,06)b | 0,80(0,04)b | 0,15(0,03)c | 0,05(0,01)d | 0,07(0,03)cd | 0,04(0,01)d | sour |

| Total | 4,65(0,36)a | 2.45 (0,25)d | 2,58(0,16)cd | 2,63(0,16)cd | 3,87(0,18)b | 4,06(0,13)b | 2,71(0,19)cd | 2,86(0,20)c | |

| n.i. | 0,09 | 0,73 | 0,58 | 0,47 | 0,15 | 0,99 | 0,55 | 0,08 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).