Submitted:

07 October 2023

Posted:

07 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

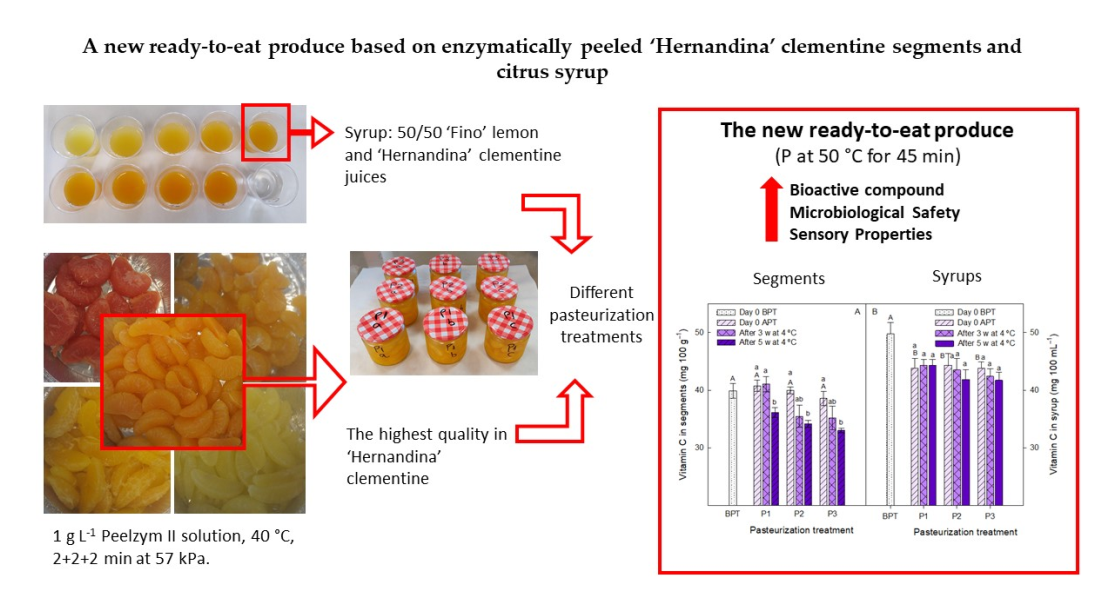

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant material

2.2. Enzymatic peeling of citrus cultivars

2.3. Sugar syrups

2.4. Elaboration of the ready-to-eat ‘Henandina’ clementine segments in syrup

2.5. Total soluble solids, pH, titratable acidity and vitamin C measures

2.6. Microbiological and sensory analysis of the new ready-to-eat produce

2.7. Statistical analysis

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Effect of incubation time on quality scores of citrus peeled segments

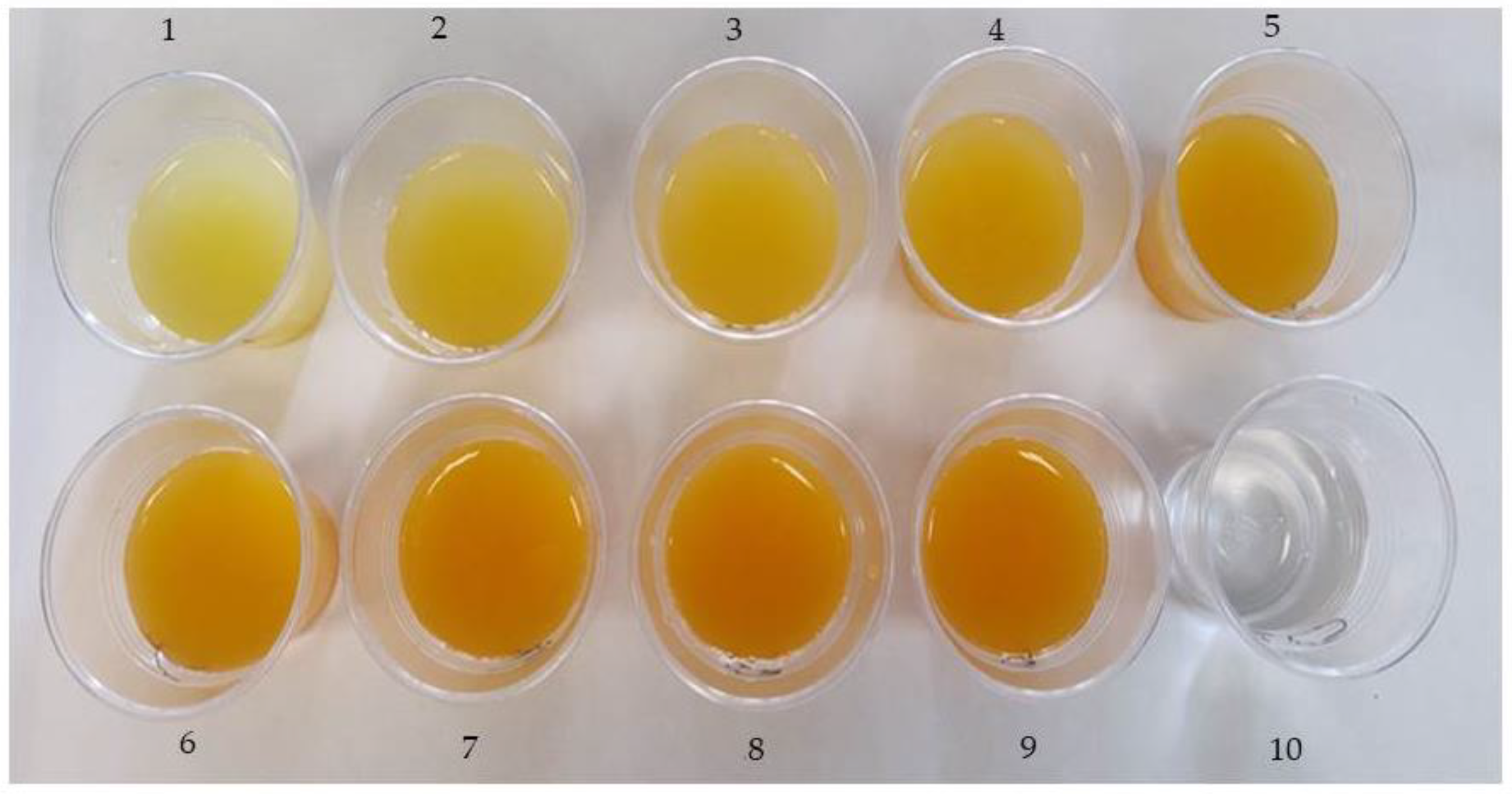

3.2. Selection of syrup to elaborate the new ready-to-eat clementine segment produce

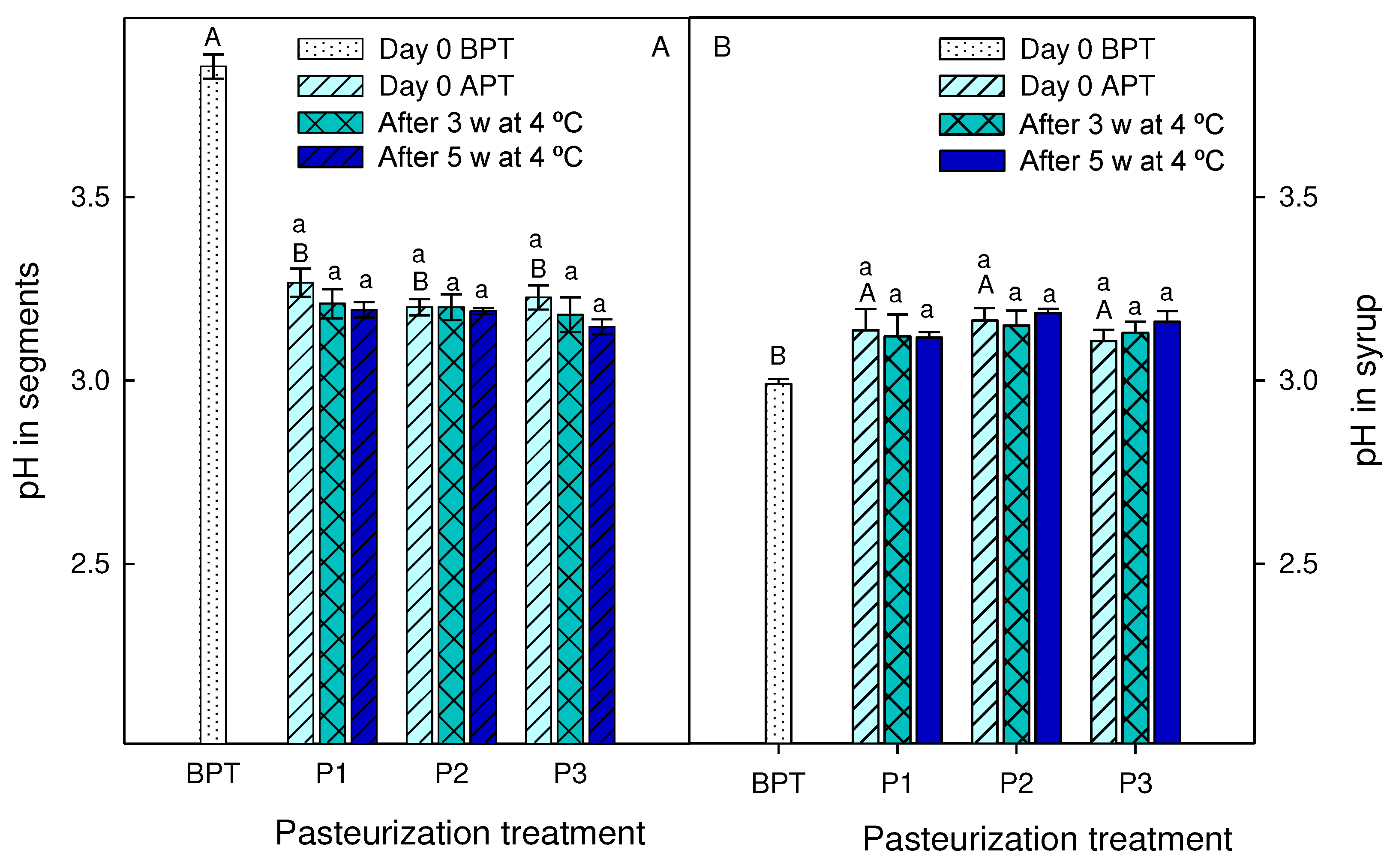

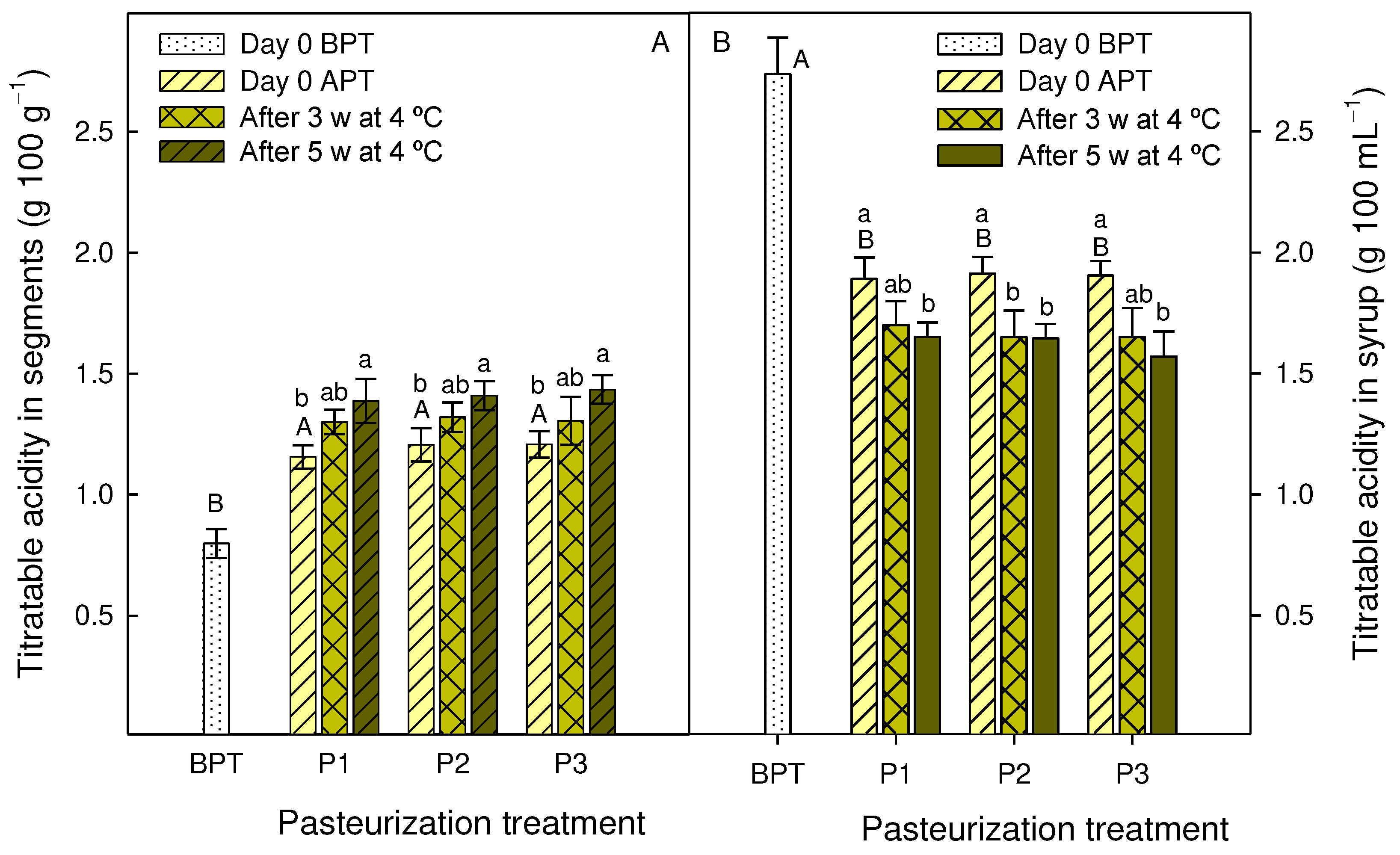

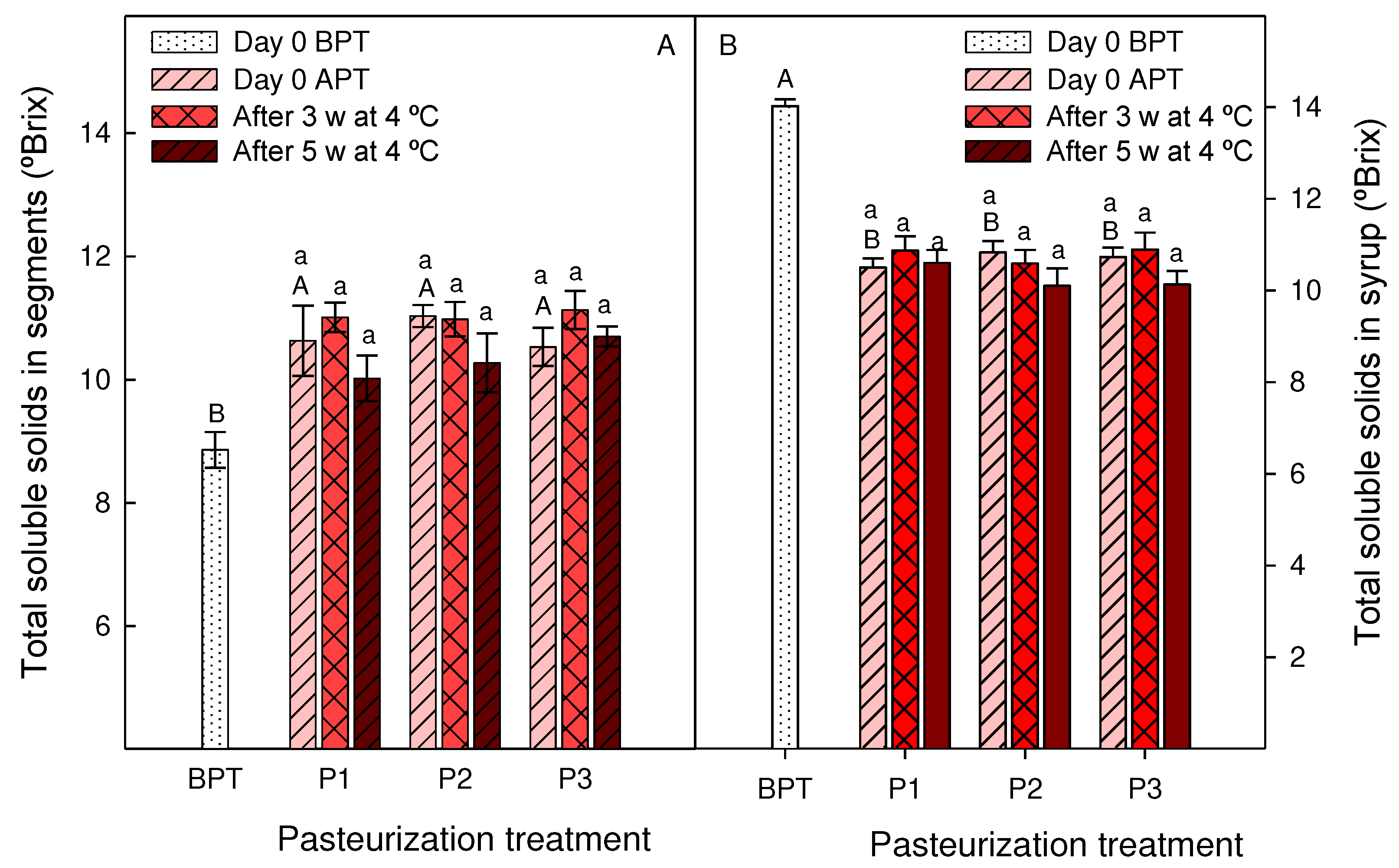

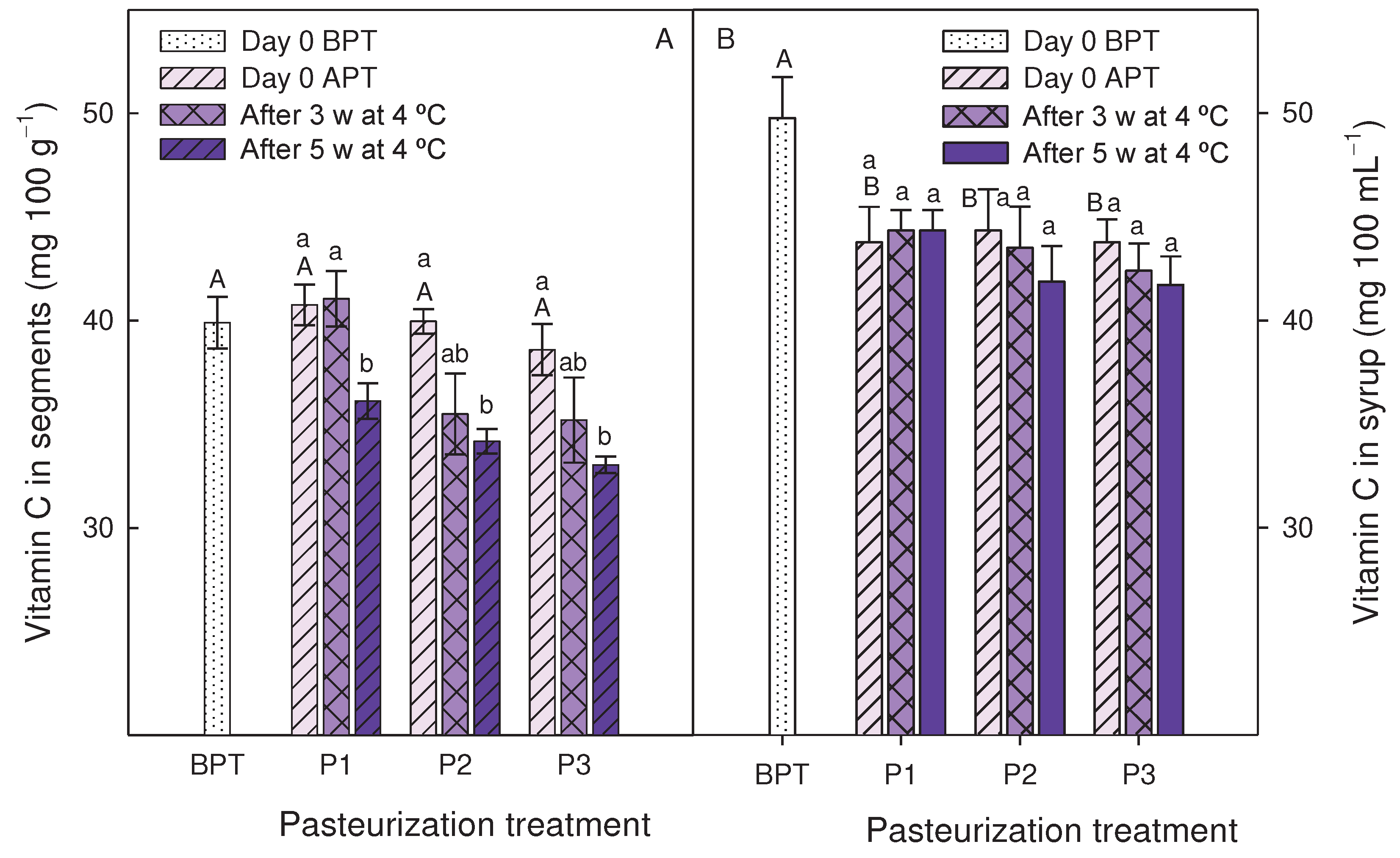

3.3. Effect of pasteurization processes on syrups and segments quality traits during storage

3.3. Sensorial and microbiological quality

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, W.; Chen, H.; Xu, B.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Cao, Y.; Xing, X. Research progress on classification, sources and functions of dietary polyphenols for prevention and treatment of chronic diseases. J. Future Foods. 2023, 3, 289–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomé-Carneiro, J.; Visioli, F. Plant-based diets reduce blood pressure: A systematic review of recent evidence. Current Hypertension Reports, 2023, 25, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahr, S.; Zahr, R.; El Hajj, R.; Khalil, M. Phytochemistry and biological activities of Citrus sinensis and Citrus limon: an update. J. Herb. Med. 2023, 41, 100737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adetunji, J.A.; Fasae, K.D.; Awe, A.I.; Paimo, O.K.; Adenoke, A.M.; Akintunde, J.K.; Sekhoacha, M.P. The protective roles of citrus flavonoids, naringenin, and naringin on endothelial cell dysfunction in diseases. Heliyon 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Degreef, F. Convenience foods, as portrayed by a consumer organisation. Test-Aankoop/Test-Achats (1960–1995). Appetite 2015, 94, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Corato, U. Improving the shelf-life and quality of fresh and minimally-processed fruits and vegetables for a modern food industry: A comprehensive critical review from the traditional technologies into the most promising advancements. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 60, 940–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wansink, B.; Just, D.R.; Hanks, A.S.; Smith, L.E. Pre-sliced fruit in school cafeterias: children's selection and intake. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2013, 44, 477–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira-Gomes, B.A.F.; Alexandre, A.C.S.; de Andrade, G.A.V.; Zanzini, A.P.; Araújo de Barros, H.E.; Dos-Santos Ferraz e Silva, M.L.; Costa, P.A.; Boas, E.V.D.B.V. Recent advances in processing and preservation of minimally processed fruits and vegetables: A review. Part 2: Physical methods and global market outlook. In Food Che. Adv.; 2023; Volume 2, p. 100304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacivita, V.; Incoronato, A.L.; Conte, A.; Nobile, M.A.D. Pomegranate peel powder as a food preservative in fruit salad: A sustainable approach. Foods, 2021, 10, 1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcón-Flores, M.I.; Hernández-Sánchez, F.; Romero-González, R.; Plaza-Balaños, P.; Martínez-Vidal, J.L.; Garrido-Frenich, A. Determination of several families of phytochemicals in different pre-cooked convenience vegetables: Effect of lifetime and cooking. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2014, 65, 791–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, N.; Marquès, M.; Nadal, M.; Domingo, J. Occurrence of environmental pollutants in foodstuffs: A review of organic vs. conventional food. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2019, 125, 370–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Bel, P.; Egea, I.; Serrano, M.; Romojaro, A.; Pretel, M.T. Obtaining and storage of ready-to-use segments from traditional orange obtained by enzymatic peeling. Food Sci Technol Int. 2012, 18, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretel, M. T.; Botella, M. A.; Amorós, A.; Serrano, M.; Egea, I.; Romojaro, F. Obtaining fruit segments from a traditional orange variety (Citrus sinensis (L.). Osbeck cv. Sangrina) by enzymatic peeling. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2007, 225, 783–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretel, M.T.; Sánchez-Bel, P.; Egea, I.; Romojaro, F. Chapter 6: Enzymatic peeling of citrus fruits. In Enzymes in Fruit and Vegetable Processing: Chemistry and Engineering Applications, 1º ed.; A. Bayindirle, A., Ed.; CRC Press: FL. Boca Raton, 2010; pp. 145–174. [Google Scholar]

- Pieroni, V.; Ottaviano, F.G.; Gabilondo, J.; Budde, C.; Andres, S.; Garitta, L. Enzymatic peeling: first advance on the development of the flavor sensory profile of Navel oranges. Idesia 2021, 39, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios, S.; De Aceredo, A.; Chao, G.; de Armas, V.; Ares, G.; Martín, A.; Soubes, M.; Lema, P. Passive modified atmosphere packaging extends shelf life of enzymatically and vacuum-peeled ready-to-eat Valencia orange segments. J. Food Qual. 2014, 37, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico, D.; Martin-Diana, A.B.; Barat, J.M.; Barry-Ryan, C. Extending and measuring the quality of fresh-cut fruit and vegetables: A review. Trends Food Sci Techn. 2007, 18, 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Ibañez, I.; Gil, M.; Allende, A. Ready-to-eat vegetables: Current problems and potential solutions to reduce microbial risk in the production chain. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 85, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Ahmad, M.; Maqbool, M.; Dar, B.N.; Greiner, R.; Roohinejad, S. Microbiological contamination of ready-to-eat vegetable salads in developing countries and potential solutions in the supply chain to control microbial pathogens. Food Control 2018, 85, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Tang, J.; Barrett, D.M.; Sablani, S.S.; Anderson, N.; Powers, J.R. Thermal pasteurization of ready-to-eat foods and vegetables: Critical factors for process design and effects on quality. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 2970–2995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leneveu-Jenvrin, C.; Charles, F.; Barba, F.J.; Remize, F. Role of biological control agents and physical treatments in maintaining the quality of fresh and minimally-processed fruit and vegetables. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 19, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aamir, M.; Ovissipour, M.; Sablani, S.; Rasco, B. Predicting the quality of pasteurized vegetables using kinetic models: A review. Int. J. Food Sci. 2013, 271271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretel, M.T.; Fernández, P.S.; Martínez, A.; Romojaro, F. Modelling design of cuts for enzymatic peeling of mandarin and optimization of different parameters of the process. Z. Lebensm. Unters. Forsch. 1998, 207, 322–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Real Decreto 2420/1978, de 2 de junio, por el que se aprueba la Reglamentación Técnico-Sanitaria para la elaboración y venta de conservas vegetales. Boletín Oficial del Estado. Madrid, 12 de octubre de 1978, núm. 244, pp. 23702- 23707.

- Ciancaglini, P.; Santos, H.; Daghastanli, K. ;Thedei, G, Using a classical method of vitamin C quantification as a tool for discussion of its role in the body. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Educ. 2001, 29, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 2001. ISO 17410:2001. International Organization for Standardization, Microbiology of food and animal feeding stuffs — Horizontal method for the enumeration of psychrotrophic micro-organisms. https://www.iso.org/standard/30649.html.

- Pretel, M.T.; Amorós, A.; Botella, M.A.; Serrano, M. ¸ Romojaro, F. Study of albedo and carpelar membrane degradation for further application in enzymatic peeling of citrus fruits. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2005, 85, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Hernández, G.; Artés-Hernández, F.; Gómez, P.; Bretó, J.; Orihuel-Iranzo, B.; Artés, F. Postharvest treatments to control physiological and pathological disorders in lemon fruit. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2017, 14, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, S.; Singhal, R.S.; Kulkarni, P.R. Enzymic peeling of Indian grapefruit (Citrus paradisi). J. Sci. Food Agric. 2001, 81, 1440–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, Y.; Khankahdani, H.H.; Rezazadeh, R. Improving yield and fruit quality of ‘Siyahoo’ mandarin (Citrus reticulata) by foliar application of nitrogen and harvest time. Int. J. Hortic. Sci. Technol. 2021, 8, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell-McGloughlin, M. Nutritionally improved agricultural crops. Plant Physiol. 2008, 147, 939–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breidt, F. BufferCapacity3 an interactive GUI program for modelling food ingredient buffering and pH. SoftwareX 2023, 22, 101351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.-X.; Jia, M.; Gui, Y.; Ma, Y. Comparison of the effects of novel processing technologies and conventional thermal pasteurisation on the nutritional quality and aroma of Mandarin (Citrus unshiu) juice. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 64, 102425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pareek, S. , Paliwal, R.; Mukherjee, S. Effect of juice extraction methods and processing temperature-time on juice quality of Nagpur mandarin (Citrus reticulata Blanco) during storage. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 48, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidu, K.A. Vitamin C in human health and disease is still a mystery? An overview. Nutr. J. 2013, 2, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballistreri, G.; Fabroni, S.; Romeo, F.V.; Timpanaro, N.; Amenta, M.; Rapisarda, P. Anthocyanins and Other Polyphenols in Citrus Genus: Biosynthesis, Chemical Profile, and Biological Activity. R.R. Watson (Ed.), Polyphenols in Plants (Second Edition): Isolation, Purification and Extract Preparation, Academic Press, San Diego, CA (2019), pp. 191-215. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Lou, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, P.; Yang, B.; Gu, Q. Review of phytochemical and nutritional characteristics and food applications of Citrus L. fruits. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 968604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badiche-El Hallali, F.; Valverde, J.M.; García-Pastor, M.E.; Serrano, M.; Castillo, S.; Valero, D. Melatonin postharvest treatment in leafy ‘Fino’ lemon maintains quality and bioactive compounds. Foods 2023, 12, 2979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serna-Escolano, V.; Martínez-Romero, D.; Giménez, M.J.; Serrano, M.; García-Martínez, S.; Valero, D.; Valverde, J.M.; Zapata, P.J. Enhancing antioxidant systems by preharvest treatments with methyl jasmonate and salicylic acid leads to maintain lemon quality during cold storage. Food Chem. 2021, 338, 128044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bang, I.H.; Kim, Y.E; Min, S.C. Preservation of mandarins using a microbial decontamination system integrating calcium oxide solution washing, modified atmosphere packaging, and dielectric barrier discharge cold plasma treatment. Food Packag. Shelf Life. 2021, 29, 100682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Sun, Y.; Qiao, L.; Chen, J.; Liu, D.; Ye, X. Effect of UV-C treatments on phenolic compounds and antioxidant capacity of minimally processed Satsuma mandarin during refrigerated storage. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2013, 76, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, F.N.; Lourenço, S.; Fidalgo, L.G.; Santos, S.A.O.; Silvestre, A.J.D.; Jerónimo, E.; Saraiva, J.A. Long-term effect on bioactive components and antioxidant activity of thermal and high-pressure pasteurization of orange juice. Molecules 2018, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortés, C.; Esteve, M. J.; Frígola, A. Effect of refrigerated storage on ascorbic acid content of orange juice treated by pulsed electric fields and thermal pasteurization. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2008, 227, 629–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njoku, P. C.; Ayuk, A. A.; Okoye, C. V. Temperature effects on vitamin C content in citrus fruits. Pakistan J. Nutr. 2011, 10, 1168–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danişman, G.; Arslan, E.; Tokulucu, A. K. Kinetic analysis of anthocyanin degradation and polymeric colour formation in grape juice during heating. Czech J. Food Sci. 2015, 33, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhan, M.T.; Quyen, D.K. Effects of heating process on kinetic degradation of anthocyanin and vitamin C on hardness and sensory value of strawberry soft candy. Acta Sci. Pol. Technol. Aliment. 2023, 22, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabroni, S.; Romeo, F.; Rapisarda, P. Chapter 7: Nutritional Composition of Clementine (Citrus x clementina) Cultivars. In Nutritional Composition of Fruit Cultivars, 1ª ed.; M. S.J. Simmonds; V.R. Preedy.; Eds.; Academic Press, Londres, Reino Unido, 2015; pp.149-172.

- Dejgård, J.; Christensen, T.; Denver, S.; Ditlevsen, K.; Lassen, J.; Teuber, R. Heterogeneity in consumers' perceptions and demand for local (organic) food products. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 73, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Citrus cultivar | Incubation time (min) | No attacked albedo (%) | Easiness of skin removing | Easiness of segment separation | Segment firmness | Viable segments (%) | Global acceptance (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ‘Star Ruby’ grapefruit | 10 20 30 |

16.01±1.74 b 25.25±1.32 a 14.18±1.63 b |

2.61±0.29 c 3.09±0.33 b 4.22±0.20 a |

2.01±0.63 b 2.29±0.40 b 4.41±0.49 a |

4.02±0.23a 3.64±0.13b 3.09±0.29c |

80.01±3.21 a 84.27±4.02 a 73.04±3.61 b |

75.01±3.16 a 78.17±3.16 a 65.02±2.78 b |

| ‘Fino’ lemon | 10 20 30 |

24.08±2.53 a 7.37±0.78 b 0 c |

3.61±0.49 c 4.42±0.80 b 5±0 a |

3.42±0.49 c 4.27±0.98 b 5±0 a |

3.82±0.40c 4.41±0.49b 5±0 a |

82.04±2.48 b 86.25±2.40 b 98.01±4.02 a |

83.24±2.48 b 84.38±4.20 b 98.09±4.21 a |

| ‘Navel’ orange | 10 20 30 |

3.02±0.45 a 0 b 0 b |

4.40±0.19 b 4.30±0.24 b 5±0 a |

4.41±0.29 b 4.77±0.40 b 5±0 a |

3.44±0.29c 4.01±0 b 5±0 a |

83.27±3.04 c 90.05±3.16 b 100±0 a |

85.01±2.47 c 90.87±2.05 b 100±0 a |

| ‘Orogrande’ clementine | 10 20 30 |

0 0 0 |

4.41±0.19 b 5±0 a 5±0 a |

2.81±2.31 b 5±0 a 5±0 a |

5±0 a 3.80±0.17b 3.01±0.14c |

100±0 a 93.14±3.12 b 73.02±3.78 c |

96.34±2.21 a 95.31±3.12 a 73.06±3.16 b |

| ‘Hernandina’ clementine | 10 20 30 |

0 0 0 |

5±0 a 5±0 a 5±0 a |

5±0 a 5±0 a 5±0 a |

5±0 a 4.62±0.25b 4.03±0.17c |

100±0 a 100±0 a 97.07±1. 24 a |

98.21±1.74 a 97.36±1.45 a 96.24±2.74 a |

| FLJ and HCJ percentages |

Initial TSS (°Brix) | Sugar added (g 100 mL-1) |

pH of the syrups | TA (g 100 mL-1) of the syrups |

| 90% FLJ/10% HCJ | 9.12±0.12 f | 5.71±0.31a | 2.24±0.35 d | 5.26±0.04 a |

| 80% FLJ /20% HCJ | 9.43±0.19 ef | 5.12±0.23 ab | 2.71±0.28 c | 4.85±0.10 b |

| 70% FLJ /30% HCJ | 9.74±0.23 de | 4.75±0.21 bc | 2.75±0.19 c | 4.37±0.06 c |

| 60% FLJ /40% HCJ | 9.96±0.27 cde | 4.51±0.17 ce | 2.84±0.32 bc | 4.01±0.08 d |

| 50% FLJ /50% HCJ | 10.31±0.29 bcd | 4.36±0.15 ce | 2.88±0.23 bc | 3.30±0.13 e |

| 40% FLJ /60% HCJ | 10.53±0.33 bc | 4.21±0.11 ef | 2.93±0.15 ab | 2.92±0.08 f |

| 30% FLJ /70% HCJ | 10.71±0.28 ab | 4.09±0.09 efg | 2.99±0.16 ab | 2.44±0.09 g |

| 20% FLJ /80 % HCJ | 10.87±0.29 ab | 3.79±0.11 fgh | 3.10±0.10 a | 1.91±0.08 h |

| 10% FLJ /90% HCJ | 11.12±0.27a | 3.61±0.12 g | 3.30±0.25a | 1.49±0.11 i |

| Control b | 0 | 18.5 | - | - |

| Syrups (%FLJ/%HCJ) |

Colour | Sourness | Sweetness | Aroma | Overall impression | Purchase intention |

| 90% FLJ /10%HCJ | 4.88±0.28 f | 9.75±0.20 a | 1.50±0.18 h | 5.00±0.40 b | 3.75±0.30 d | 3.75±0.32 c |

| 80% FLJ /20% HCJ | 5.00±0.19 f | 9.38±0.34 ab | 1.63±0.13 h | 5.13±0.56 b | 3.38±0.20 d | 3.63±0.27 c |

| 70% FLJ /30% HCJ | 5.63±0.23 e | 8.62±0.38 b | 2.75±0.31 g | 4.90±0.42 b | 4.63±0.23 c | 3.88±0.22 c |

| 60% FLJ /40% HCJ | 5.63±0.27 e | 7.38±0.24 c | 3.13±0.27 g | 5.63±0.32 ab | 6.35±0.20 a | 5.13±0.26 b |

| 50% FLJ /50% HCJ | 7.00±0.16 d | 6.63±0.23 d | 4.13±0.14 f | 6.55±0.43 a | 6.53±0.15 a | 6.25±0.15 a |

| 40% FLJ /60% HCJ | 7.50±0.22 c | 6.38±0.19 e | 4.88±0.28 e | 5.88±0.52 ab | 6.88±0.22 a | 6.38±0.15 a |

| 30% FLJ /70% HCJ | 8.00±0.16 b | 5.25±0.29 f | 6.00±0.17 d | 5.13±0.37 b | 6.63±0.29 a | 5.13±0.04 b |

| 20% FLJ /80% HCJ | 8.88±0.29 a | 4.13±0.16 g | 6.63±0.22 c | 4.38±0.24 bc | 5.38±0.32 b | 5.38±0.11 b |

| 10% FLJ /90% HCJ | 9.38±0.21a | 3.13±0.22 h | 7.63±0.32 b | 3.88±0.26c | 5.50±0.28 b | 5.63±0.26 b |

| Control | 5.00±0.25 f | 0 i | 9.50±0.27 a | 1.13±0.11d | 2.63±0.11 e | 2.63±0.08 d |

| Storage time and pasteurization treatment | Odour | Colour | Acidity | Sweetness | Aroma | Texture | Overall impression |

| Day 0 P1 | 6.50±0.32aB | 8.00±0.23aA | 7.25±0.49a | 5.31±0.24 a | 5.50±0.17a | 6.50±0.23aB | 6.25±0.26aB |

| Day 0 P2 | 6.10±0.22aA | 7.25±0.28bA | 6.75±0.36a | 5.62±0.62a | 4.75±0.36b | 4.50±0.37bA | 5.25±0.36bA |

| Day 0 P3 | 6.25±0.86aA | 7.00±0.41bA | 6.65±0.44a | 5.28±0.47a | 4.50±0.50b | 3.50±0.20cA | 5.03±0.24bA |

| 21 Days 4°C P1 | 7.25±0.23aA | 8.25±0.43aA | - | - | - | 7.00±0.27aAB | 7.75±0.34aA |

| 21 Days 4°C P2 | 6.75±0.37abA | 7.00±0.4bA | - | - | - | 4.75±0.28bA | 5.75±0.28bA |

| 21 Days 4°C P3 | 6.50±0.32bA | 6.75±0.49bA | - | - | - | 4.00±0.24cA | 5.50±0.17bA |

| 35 Days 4°C P1 | 7.50±0.3aA | 8.50±0.37aA | - | - | - | 7.30±0.35aA | 8.02±0.20aA |

| 35 Days 4°C P2 | 6.25±0.28bA | 6.75±0.36bA | - | - | - | 4.75±0.28bA | 5.70±0.25bA |

| 35 Days 4°C P3 | 6.75±0.25bA | 6.50±0.55bA | - | - | - | 3.75±0.36cA | 5.51±0.19bA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).