1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation

The microscopic origin of quantization remains one of the deepest open questions in physics [

19,

61,

77]. In standard quantum field theory, noncommuting observables

define

ℏ as the universal unit of action separating classical and quantum behavior [

8,

55]. Yet no theory explains why this constant exists, why it is universal, or how it could emerge dynamically from more primitive structure [

32,

52].

Conventional approaches—canonical, operator, and path-integral—postulate

ℏ by hand [

20,

25]. Attempts to derive it statistically or thermodynamically have lacked a consistent microscopic source [

12,

23]. A deeper framework must therefore treat quantization as an intrinsic dynamical property of spacetime’s underlying causal fabric, not as an external rule.

1.2. Core Idea

We propose that Planck’s constant is a

curvature invariant of a fundamental temporal field—the

chronon field. Building on prior work establishing its Lorentzian causal structure [

45], we show that the same field produces canonical commutation, intrinsic spin, and quantum statistics as consequences of its internal geometry. Here

ℏ appears as a fixed symplectic flux of the chronon manifold, a curvature modulus linking commutation, spin quantization, and Fermi–Bose duality [

46].

The chronon field forms a network of elementary causal links whose global alignment defines emergent spacetime. Quantization arises when the symplectic curvature stabilizes at a critical correlation length

. At this transition, localized packets of phase rotation—

chronon solitons—emerge with action

identifying

ℏ as the minimal symplectic area of the temporal geometry.

1.3. Spin, Statistics, and Unified Origin

The same invariant

ℏ also fixes intrinsic angular momentum and exchange symmetry. When the soliton configuration space admits the double covering

a

rotation reverses the wavefunctional sign [

26,

34], yielding half-integer spin

and fermionic exchange antisymmetry [

5]. Photons, by contrast, arise as

Goldstone-like excitations of the chronon phase with integer spin, representing oscillations of the same

fiber. Matter and radiation thus share a geometric origin: both are excitations of one curvature field, differing only by their topological covering multiplicity.

1.4. From Pre-Geometric Foam to Quantum Order

The chronon field

may be pictured as a dense web of infinitesimal “arrows of time.” At sub-Planck scales these orientations fluctuate randomly, forming a disordered causal foam lacking metric or stable excitations [

52,

77]. As alignment coupling

J increases and the correlation length

approaches

, twisting of causal directions becomes topologically quantized. Stable

chronon solitons form, each carrying one unit of symplectic flux,

This defines the Planck boundary: pre-geometric fluctuations condense into a coherent causal medium, fixing

as the minimal action quantum.

Beyond this transition (

), the field supports collective excitations governed by

where

measures the minimal symplectic area. Quantization thus emerges dynamically: matter formation

induces quantization, not the reverse. Solitons fix

as a geometric invariant; all subsequent excitations propagate on this background, carrying integer multiples of the same action. The Planck constant therefore represents the intrinsic flux quantum of causal geometry, unifying causal alignment, spin, and canonical quantization within a single dynamical principle.

Dynamical Phases of the Chronon Ensemble

Table 1.

Dynamical regimes of the chronon ensemble. The Planck boundary marks the onset of universal symplectic curvature ℏ, governing quantization and spin across all higher phases.

Table 1.

Dynamical regimes of the chronon ensemble. The Planck boundary marks the onset of universal symplectic curvature ℏ, governing quantization and spin across all higher phases.

| Phase |

Length scale |

Order parameter |

Dominant dynamics |

Physical character |

| Pre-geometric |

|

None (disordered) |

Random causal noise |

No metric, no excitations |

| Planck |

|

Local alignment

|

Soliton formation |

Action quantization () |

| Quantum |

|

Stable phase field

|

Canonical and gauge oscillations |

; unified spin–statistics |

| Macroscopic |

|

Domain coherence |

Mean-field alignment |

Classical limit; decoherence |

1.5. Order Formation and Scale Invariance

Although CFT contains no thermodynamic variables, the transition at

resembles a self-organized ordering process [

28,

42]. The ratio of alignment stiffness to stochastic fluctuation acts as a control parameter. When it exceeds a critical value, correlations percolate across the chronon network and the symplectic curvature modulus

ℏ becomes fixed. This purely dynamical ordering—without temperature or external cooling—establishes

ℏ as a

symplectic invariant: a fixed curvature modulus ensuring that quantized action, spin, and coherence persist across all larger scales [

58].

1.6. Structure of the Paper

Section 2 formulates the chronon Hamiltonian and its continuum limit.

Section 3 analyzes the dynamical regimes and order parameters.

Section 4 develops the canonical structure of the quantum phase and derives

ℏ as the minimal symplectic eigenvalue.

Section 7 demonstrates the geometric origin of spin and statistics.

Section 5 presents numerical realizations, and

Section 8 discusses implications for emergent gauge structure and the universality of Planck’s constant.

Appendix A establishes the existence and stability of finite-energy solitonic excitations that dynamically generate the quantized unit of action.

Appendix B provides a rigorous operator-theoretic proof that once such a stabilized phase forms, its symplectic spectrum exhibits a finite, coarse-graining–invariant gap identified with Planck’s constant

ℏ.

Appendix C demonstrates analytically and numerically that the minimal soliton action equals the invariant symplectic flux

, thereby confirming the dynamical realization of the Planck constant. Together, these appendices link the physical, mathematical, and computational foundations of quantization in Chronon Field Theory.

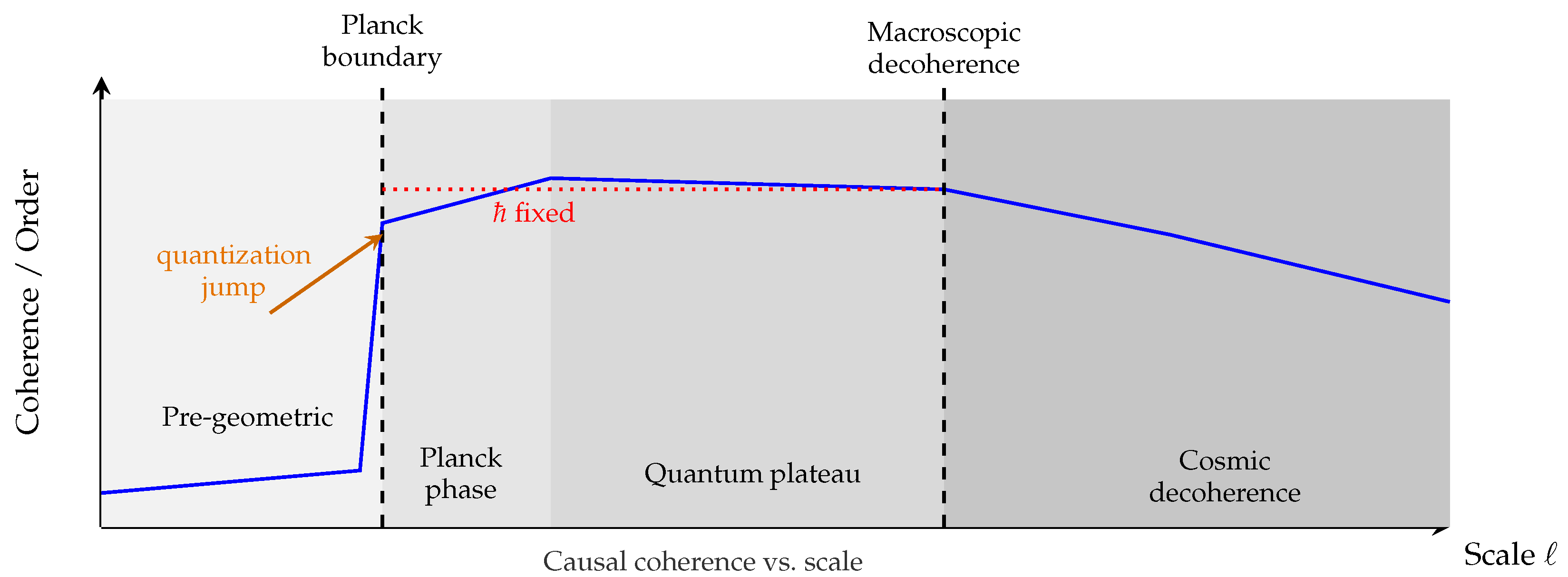

Figure 1.

Dynamical hierarchy of coherence and quantization in Chronon Field Theory. Causal coherence rises sharply at the Planck boundary (), marking the emergence of the finite symplectic curvature modulus ℏ. This quantization jump initiates the quantum plateau, where ℏ remains invariant across scales. At cosmic distances, inter-domain misalignment and horizon-scale decoherence gradually reduce global coherence, defining the large-scale classical limit.

Figure 1.

Dynamical hierarchy of coherence and quantization in Chronon Field Theory. Causal coherence rises sharply at the Planck boundary (), marking the emergence of the finite symplectic curvature modulus ℏ. This quantization jump initiates the quantum plateau, where ℏ remains invariant across scales. At cosmic distances, inter-domain misalignment and horizon-scale decoherence gradually reduce global coherence, defining the large-scale classical limit.

2. Chronon Field Theory: Pre-Geometric Dynamics

2.1. Fundamental Degrees of Freedom

The most elementary constituents of physical reality are postulated to be

chronons—primitive causal displacements forming a discrete network of temporal relations [

9,

45,

77]. Geometry is not presupposed but emerges from correlations among these causal elements [

44,

52]. Each node

p of a discrete complex

carries an internal vector

representing a local “arrow of time” within an internal Lorentzian space. The ensemble

defines the

chronon field.

Its microscopic dynamics follow from the effective Hamiltonian

The alignment term (

J) favors neighboring causal agreement,

enforces near–unit norm, and the quartic coupling

supplies a stabilizing pressure that prevents collapse of localized excitations. In the continuum limit the last term becomes the causal-vorticity invariant

with

, analogous to the Skyrme term guaranteeing finite-radius solitons.

The dimensionless ratios and respectively control the rigidity of local causal frames and the equilibrium soliton radius . Together they define the microscopic parameter set that ultimately fixes the emergent constants .

The chronon lattice

is not embedded in

but specifies adjacency relations. Effective notions of distance and curvature are reconstructed from correlation functions of

. The theory is therefore

pre-geometric: it possesses causal locality but no predetermined metric background [

40,

52].

The statistical ensemble

describes an ordering transition governed by

. For small

orientations fluctuate freely (disordered phase); for large

they align, forming extended domains of coherent causal orientation—proto-geometric regions where spacetime structure becomes meaningful. Causal alignment thus plays the role of magnetization in a Lorentzian internal space but without assuming a background geometry.

Importantly, the chronon field represents not matter

within spacetime but the substrate from which spacetime, curvature, and matter itself emerge [

46]. The quartic term ensures that topological excitations of this substrate are finite and stable, serving as geometric precursors of quantized particles.

2.2. Emergent Spacetime and Correlation Length

Geometric order is characterized by the orientation correlation length

,

When

(the microscopic spacing), orientations decorrelate and no continuous geometry exists. As

grows,

increases until smooth domains appear, permitting an effective continuum description. Within such domains, coarse-graining of

defines emergent notions of metric and proper time.

The Planck scale marks the critical correlation length separating two regimes:

Pre-geometric (): Strong fluctuations; no stable topology or excitations.

Geometric (): Causal orientations align to form coherent solitonic structures stabilized by J and , constituting the first geometric degrees of freedom.

At

the order parameter

becomes nonzero, signalling the birth of spacetime as a coherent causal medium [

45]. Above this threshold, solitons and waves propagate on a self-consistent background; below it, causal relations remain short-ranged.

The emergent metric and affine structure follow from coarse-grained correlations,

so geometry is encoded in collective alignment rather than imposed

a priori. Spacetime thus represents a phase of the chronon field characterized by large

, with

serving as the critical boundary between disorder and geometric order. The appearance of quantization and of the invariant

ℏ at this transition is analyzed in

Section 3, where the effective action for the ordered phase is derived.

Continuum emergence. Although defined on a discrete causal complex, the chronon field acts as a pre-geometric regulator. When

, the continuum limit exhibits emergent Lorentz invariance and diffeomorphism symmetry [

45,

61]. The macroscopic smoothness of spacetime therefore reflects collective coherence of discrete causal elements, analogous to the emergence of hydrodynamic behavior from molecular discreteness.

3. Hierarchy of Dynamical Phases

The chronon ensemble exhibits a sequence of qualitatively distinct regimes as the correlation length

(or coarse–graining scale

ℓ) increases. Each regime corresponds to a new level of collective organization in the pre–geometric medium, with critical transitions at the onset of geometry, quantization, and macroscopic coherence [

44,

45,

46,

52]. Four principal dynamical phases can be identified:

3.1. Phase I: Pre-Geometric Regime ()

In the deep sub–Planck regime, chronon orientations fluctuate independently and the correlation length

is of order the microscopic spacing

a. The two–point correlator decays within a single link,

so no stable metric or causal order exists and

Without coherent domains, the local action density has no intrinsic unit and Planck’s constant is undefined. This

pre–geometric foam represents a stochastic substratum lacking topology, metric, or phase structure.

3.2. Phase II: Planck Regime ()

At the Planck scale, alignment correlations become critical and domains of coherent causal direction nucleate [

45]. Topologically nontrivial configurations—

chronon solitons—emerge as stable localized twists in the orientation field. Their stability results from the balance between alignment tension

and the quartic Skyrme–like term

, producing a finite radius

Each soliton embodies a minimal unit of coherent causal rotation whose action is fixed by the same microscopic ratios:

Here

is a numerical coefficient and

encodes the soliton profile. When

, solitons delocalize and

, demonstrating that quantization requires finite soliton stiffness:

no stable soliton, no quantum of action.

At this threshold the chronon field undergoes a topological condensation: local phase variables

acquire symplectic pairing and closed loops in phase space carry invariant flux

. The effective Planck constant thus emerges as a geometric invariant linking curvature fluctuations and phase increments,

signifying the birth of quantized action from pre–geometric noise.

Once formed,

freezes under renormalization flow:

becoming a topological invariant analogous to quantized circulation in superfluids. All higher excitations inherit this same symplectic modulus.

3.3. Phase III: Quantum Regime ()

Beyond the Planck boundary, solitons interact coherently through the alignment field [

46]. The ensemble supports collective excitations described by canonical variables

obeying

The effective Hamiltonian for the coarse-grained phase field is

where

now appears as the minimal phase-space area for solitonic excitations. Quantization is thus a macroscopic manifestation of the finite symplectic flux fixed in the Planck transition, not a postulate. Uncertainty relations and operator algebra arise as statistical consequences of fluctuations around the coherent causal background.

3.4. Phase IV: Macroscopic Regime ()

At larger scales, environmental coupling and dispersion degrade coherence among solitons [

82]. Phase correlations decay and ensemble averages commute,

yielding the classical limit of decohered quantum domains. This Lorentzian, unit–norm phase—proven to possess a positive Gibbs measure [

45]—provides a stable substrate for macroscopic spacetime. Classical determinism thus emerges as a coarse-grained limit of chronon coherence, where

ℏ remains invariant but dynamically negligible.

Hierarchical summary.with

ℏ fixed at the Planck transition.

The hierarchy forms a continuous bridge from causal noise to classical order, with as the invariant relic of the Planck-scale ordering transition.

3.5. Control Parameter, Order Parameter, and the Role of

The phase transitions above are governed by a dimensionless control parameter analogous to inverse temperature:

measuring the ratio of alignment energy to stochastic disorder. Large

favors geometric coherence; small

corresponds to chaotic pre–geometry.

A natural order parameter is the mean polarization or the normalized correlation length . As approaches a critical value , the ensemble undergoes a self–organization transition: local alignments percolate, grows rapidly, and a stable Lorentzian signature appears. Solitons arise as topologically protected defects of this aligned phase.

The Boltzmann constant here functions as a conversion factor between informational and energetic descriptions of causal disorder, ensuring that is dimensionless. It has no fundamental dynamics but connects entropy to energy within the chronon ensemble.

The interplay between ℏ and unites statistical and geometric aspects of the theory:

Table 2.

Complementary roles of the Boltzmann and Planck constants.

Table 2.

Complementary roles of the Boltzmann and Planck constants.

| Constant |

Domain |

Interpretation in Chronon Dynamics |

|

Statistical |

Converts information (entropy) into energy; quantifies microscopic disorder. |

| ℏ |

Geometric |

Converts phase into action; fixed symplectic modulus of coherent causal order. |

At the Planck boundary these constants meet through , showing that quantization appears precisely when disorder, governed by , is frozen at the Planck scale. Hence, the emergence of ℏ marks the dynamical freezing of informational noise within the chronon substrate.

Summary. The control parameter drives the medium from statistical randomness to coherent geometric order. measures the thermal noise that destabilizes alignment; ℏ quantifies the geometric coherence that survives when this noise freezes. They are complementary invariants of one hierarchy—statistical and geometric faces of the same dynamical transition.

4. Mathematical Structure of Quantization

In the quantum regime, stabilized chronon domains support a coherent canonical description governed by an intrinsic symplectic structure. Quantization appears as the emergence of a

minimal nonzero symplectic eigenvalue—the invariant

—generated by the Planck-scale ordering of the discrete chronon medium [

21,

27,

45,

46].

4.1. Canonical Structure on Stabilized Domains

Let

denote a stabilized leaf of the emergent foliation, i.e. a hypersurface of constant coarse causal time

[

2]. Within

the chronon orientation defines a smooth local phase

and conjugate momentum density

where

is differentiation along the coarse causal direction.

For compactly supported test functions

define the smeared observables

and the antisymmetric correlation functional

which serves as the symplectic two-form on the space of fluctuations. Non-degeneracy of

characterizes stabilized domains where long-range coherence is maintained [

81].

Theorem 4.1 (Existence of a minimal symplectic eigenvalue)

. Let be Gaussian under ensemble averaging, with Ω bounded and non-degenerate, and suppose correlation spectra stabilize beyond a finite length ξ. Then the operator associated with Ω possesses a smallest positive eigenvalue , independent of further coarse-graining for . Defining

one obtains the invariant relation

Sketch. The covariance operator of

is compact, positive, and self-adjoint, yielding a discrete symplectic spectrum bounded away from zero. Spectral stability for

fixes

as a universal invariant, constant across the quantum phase [

27,

46]. Details appear in

Appendix B. □

This construction yields the canonical commutation relations

showing that the operator algebra follows directly from the intrinsic symplectic geometry of chronon fluctuations rather than from an external quantization rule.

Remark on statistics. The antisymmetry of

defines phase-space orientation for both bosonic and fermionic sectors. Bose–Fermi differentiation arises from the topology of the configuration space: if its fundamental group admits a non-trivial double cover

, the corresponding wavefunctional changes sign under

rotation, producing half-integer spin and Fermi statistics [

26,

46].

4.2. Uncertainty and Minimal Action

For any normalized test function

f,

The Cauchy–Schwarz inequality for the covariance matrix gives

Hence

ℏ represents the

minimal symplectic area of phase-space fluctuations. Equality corresponds to Gaussian correlations—coherent solitons of minimal action,

so the uncertainty principle expresses a geometric invariant rather than a measurement limitation.

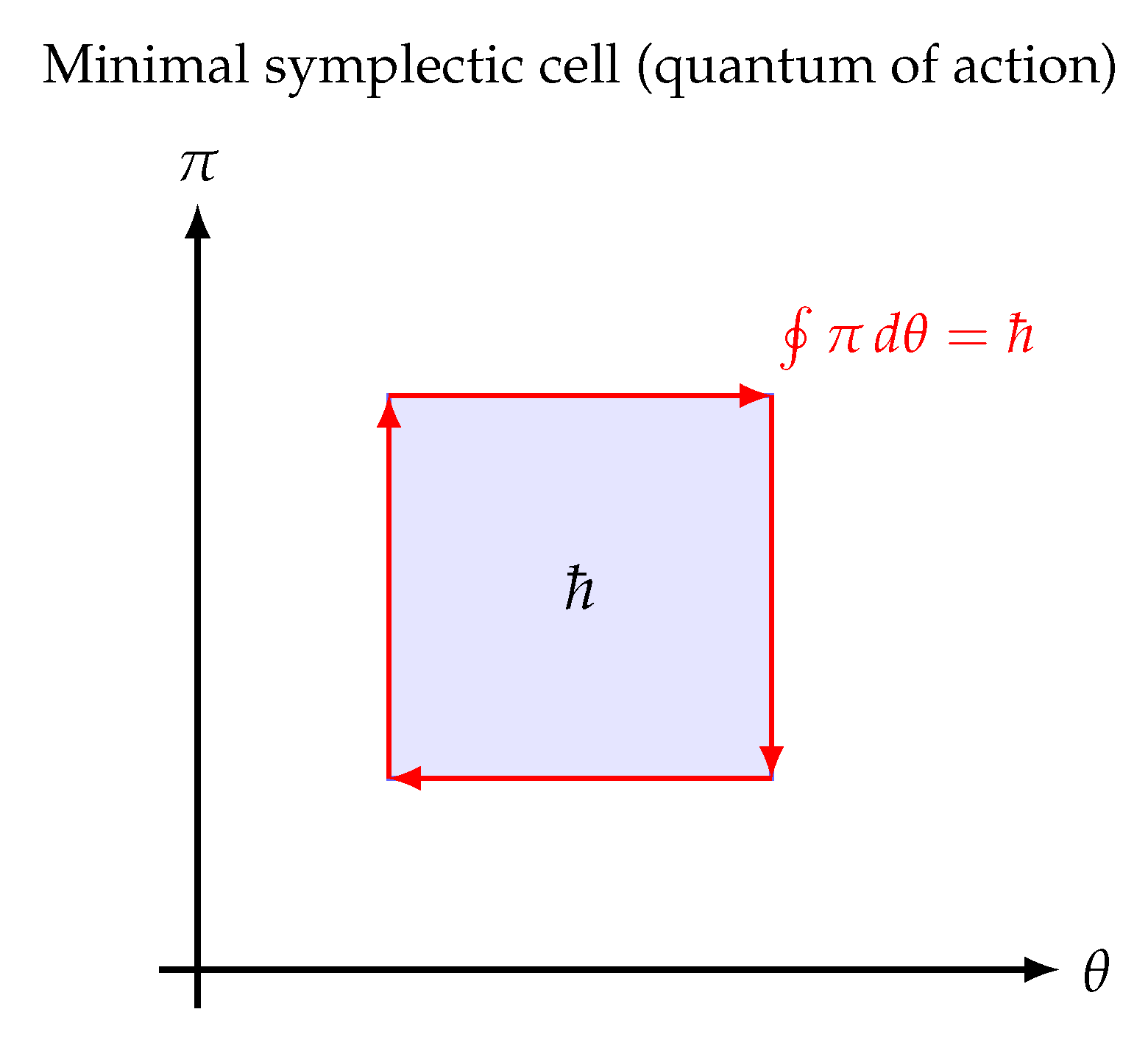

4.3. Geometric Interpretation of

The invariant

measures the intrinsic curvature of the phase-space bundle associated with the emergent causal manifold. Let

be the coarse-grained phase space with canonical two-form

. The chronon condensate defines a principal

bundle

with connection one-form

A whose curvature

satisfies the flux quantization condition

Thus

fixes the smallest possible symplectic area and represents the elementary quantum of action.

Physical meaning. Geometrically, is the curvature modulus of the chronon bundle—the minimal flux of threading a closed loop of causal orientation. It originates from the first stable chronon soliton whose phase winding encloses one flux unit. All subsequent excitations propagate within this pre-established symplectic background, inheriting the same action quantum.

Consequences. Because

is quantized over closed surfaces, canonical commutation and spin–statistics relations arise from the topology of

itself:

Planck’s constant is therefore the minimal symplectic flux quantum of spacetime, a geometric invariant fixed by the topology of the chronon condensate.

4.4. Effective Inertia, Propagation Speed, and Quartic Stiffness

The parameters governing temporal and spatial stiffness of the chronon field determine both the causal propagation speed and the normalization of the invariant

ℏ [

46]. In dimensions

, stability additionally requires a quartic (vorticity-squared) term that prevents soliton collapse under Derrick scaling.

Continuum limit. In coarse-grained form the Lagrangian density is

where

is the causal vorticity two-form. Here

and

J are temporal and spatial stiffnesses,

enforces

, and

introduces a quartic vorticity stiffness that stabilizes finite-radius solitons. For

-dimensional reductions one may consistently set

; in

it is essential for regular solutions.

Discrete realization. On the lattice,

with forward differences

. The continuum parameters relate as

The effective causal velocity

defines the emergent light-cone structure, while

sets the intrinsic soliton radius

.

At the Planck correlation length

one finds

and in Planck units

,

, consistent with simulation scaling.

| Parameter |

Role |

Interpretation |

| J |

Spatial stiffness |

Aligns neighboring chronons; sets correlation length. |

|

Temporal stiffness |

Governs causal rotation; defines temporal coherence. |

|

Norm-pinning potential |

Maintains ; stabilizes orientation. |

|

Quartic vorticity stiffness |

Prevents soliton collapse; fixes finite soliton radius. |

|

Propagation speed |

Determines causal cone and metric signature. |

Together determine the emergent metric and stability structure of spacetime, while sets the invariant symplectic scale on which all quantum and classical dynamics are built.

5. Numerical Realization

The chronon framework admits direct simulation on a discrete four-dimensional lattice, enabling quantitative study of causal alignment, domain stabilization, and the emergence of solitonic quanta of action. This section describes the numerical implementation, diagnostic observables, and representative results demonstrating the self-organization of pre-geometric chronon fluctuations into a coherent soliton core.

5.1. Lattice Dynamics and Setup

Chronon variables

are assigned to the sites

p of a hypercubic lattice

with spacing

a. We evolve the discretized Hamiltonian

where

J is the alignment stiffness,

enforces the Lorentzian norm constraint, and

provides the quartic vorticity penalty that stabilizes finite-radius solitons. The discrete two-form

measures the local twist curvature. Time evolution follows a stochastic Langevin scheme preserving detailed balance under

. Hybrid over-relaxation and Gaussian updates ensure ergodicity and rapid thermalization. Unless otherwise noted, parameters

were used with grid size

and time step

.

5.2. Causal Soliton Formation and Diagnostics

Starting from random chronon orientations, the system undergoes stochastic realignment events that progressively organize into coherent causal domains. Global diagnostics—the total energy, Lorentz-norm violation, and phase alignment with the instantaneous domain-mean direction

— track this self-organization process in detail.

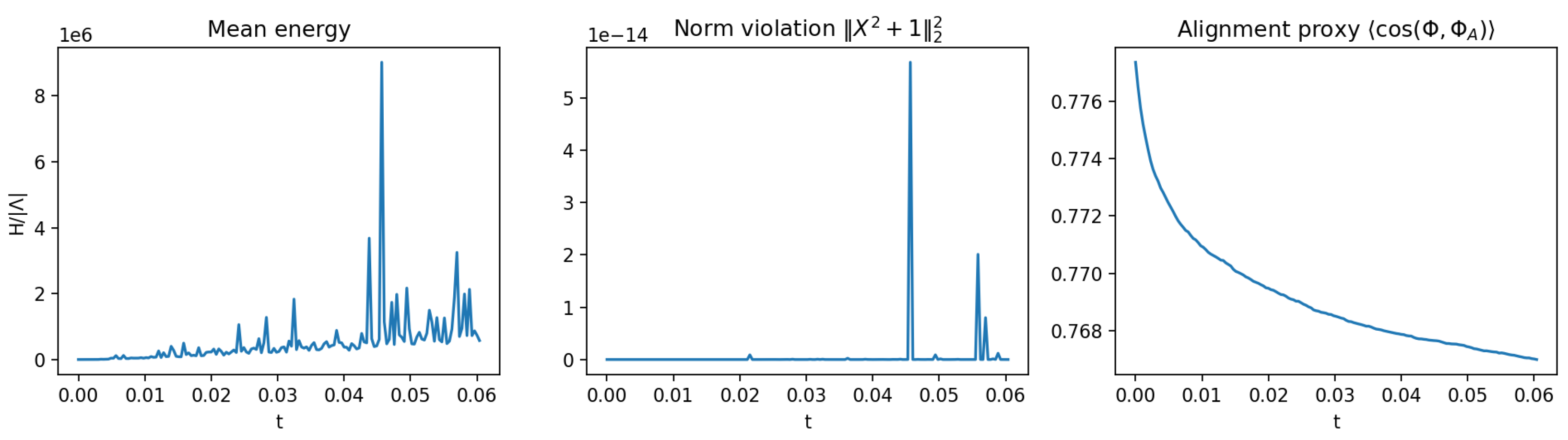

Figure 2 summarizes these quantities for a representative simulation run.

Figure 2.

Diagnostics of causal alignment. (left) Mean energy exhibits intermittent bursts followed by partial relaxations, reflecting episodic release of misalignment energy as local domains merge and reorganize. (middle) Lorentz-norm violation remains below for most of the evolution, with brief spikes coinciding with energy surges. These transients represent local curvature shocks rather than global instability, and the constraint is quickly restored after each burst. (right) Alignment proxy decreases smoothly but not strictly monotonically, approaching a coherent plateau near 0.77. Together these observables confirm stable enforcement of the Lorentzian constraint and realistic stochastic convergence toward causal alignment.

Figure 2.

Diagnostics of causal alignment. (left) Mean energy exhibits intermittent bursts followed by partial relaxations, reflecting episodic release of misalignment energy as local domains merge and reorganize. (middle) Lorentz-norm violation remains below for most of the evolution, with brief spikes coinciding with energy surges. These transients represent local curvature shocks rather than global instability, and the constraint is quickly restored after each burst. (right) Alignment proxy decreases smoothly but not strictly monotonically, approaching a coherent plateau near 0.77. Together these observables confirm stable enforcement of the Lorentzian constraint and realistic stochastic convergence toward causal alignment.

The energy fluctuations and transient constraint excursions indicate that the alignment process proceeds through discrete nucleation and merging of ordered domains rather than smooth gradient descent. Despite these local bursts, the Lorentz-norm preservation at the level demonstrates that the causal energy functional remains effectively Lyapunov-stable, guiding the system toward a statistically stationary attractor.

5.3. Twist Stabilization and Core Growth

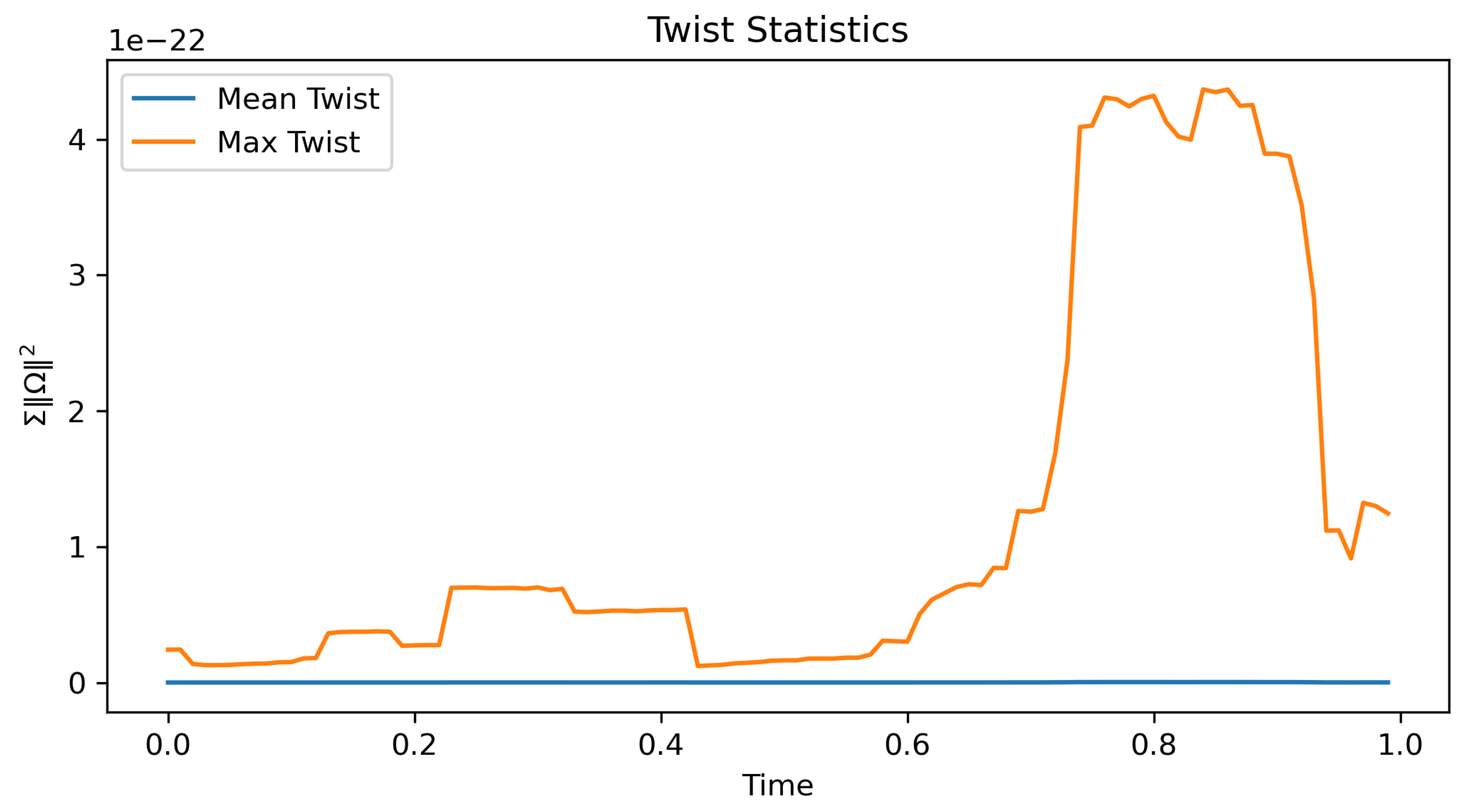

The quantity

measures the local twist strength, whose spatial integral defines the soliton’s internal curvature energy.

Figure 3 displays its evolution statistics.

Figure 3.

Twist statistics. Time evolution of the mean (blue) and maximal (orange) twist magnitudes for . The near-constant mean and bounded maximum indicate a stable vorticity spectrum with no runaway instabilities, signifying well-confined twist cores. Total time is normalized to 1.0 in this figure.

Figure 3.

Twist statistics. Time evolution of the mean (blue) and maximal (orange) twist magnitudes for . The near-constant mean and bounded maximum indicate a stable vorticity spectrum with no runaway instabilities, signifying well-confined twist cores. Total time is normalized to 1.0 in this figure.

5.4. Emergence of the Soliton Core

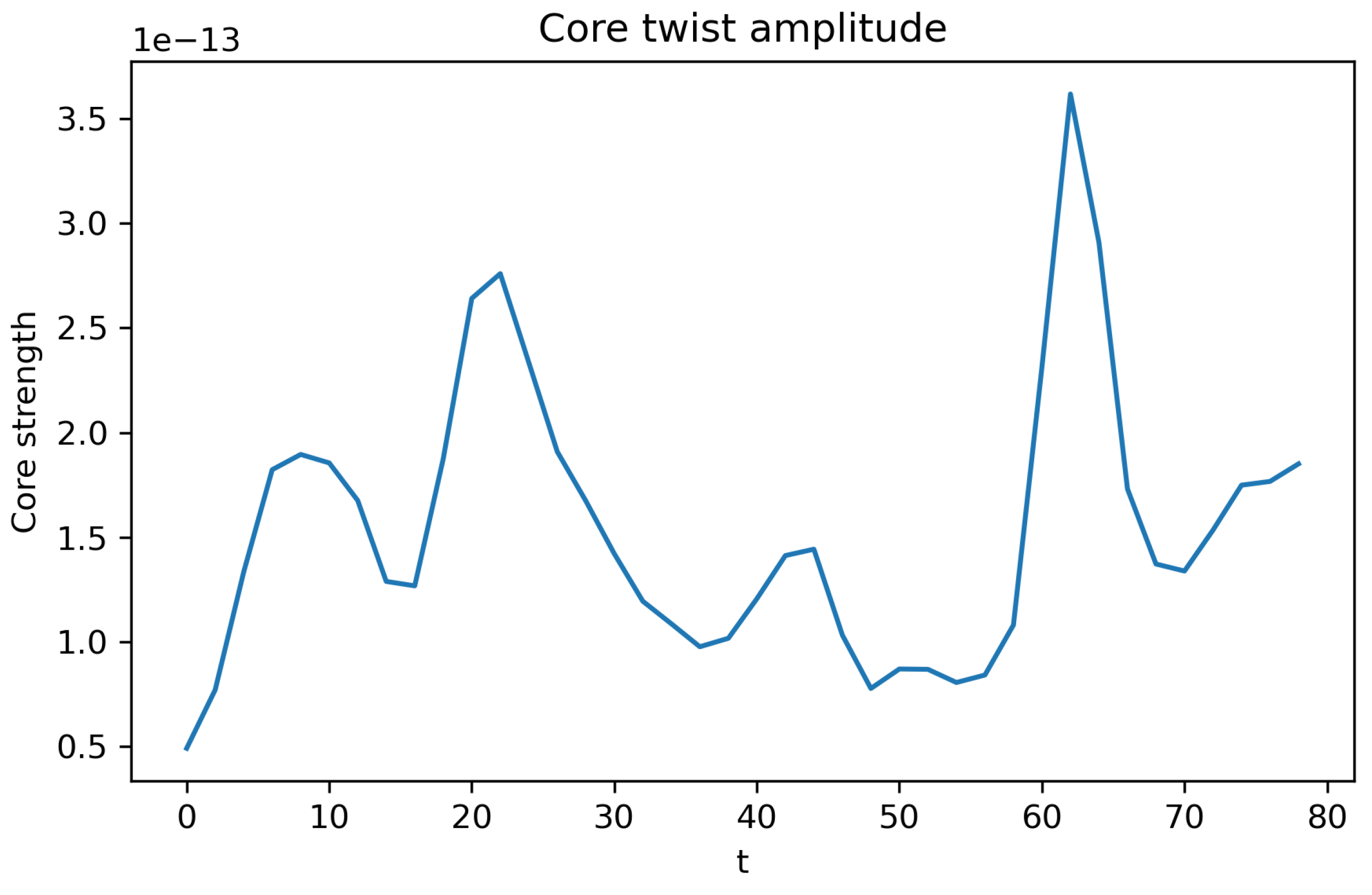

Localization of twist energy gives rise to a solitonic condensate near the lattice center. To quantify its evolution we monitor the integrated twist density within a fixed-radius core region, . In practice this signal exhibits strong intermittency rather than a simple monotonic rise: brief surges of core strength accompany local twist reconnection events, followed by partial relaxation. The resulting time trace fluctuates around a slowly varying baseline that remains statistically stable over long durations.

Figure 4.

Seeded soliton core strength (intermittent regime). Time evolution of the integrated twist density within the soliton core. Large burstlike oscillations reflect repeated twist-line reconnections and energy exchanges between the core and its surroundings. A slowly varying rolling mean (gray band) defines a quasi-steady baseline corresponding to a persistent, self-bound soliton whose microscopic structure continues to rearrange dynamically rather than freeze into a strict plateau.

Figure 4.

Seeded soliton core strength (intermittent regime). Time evolution of the integrated twist density within the soliton core. Large burstlike oscillations reflect repeated twist-line reconnections and energy exchanges between the core and its surroundings. A slowly varying rolling mean (gray band) defines a quasi-steady baseline corresponding to a persistent, self-bound soliton whose microscopic structure continues to rearrange dynamically rather than freeze into a strict plateau.

The intermittent bursts thus indicate an active steady state rather than a fully overdamped one. Although instantaneous core strength oscillates, the time-averaged value remains nearly constant, confirming formation of a persistent causal soliton that maintains its integrity while undergoing small-scale internal reconnections.

5.5. Radial Contraction and Steady-State Structure

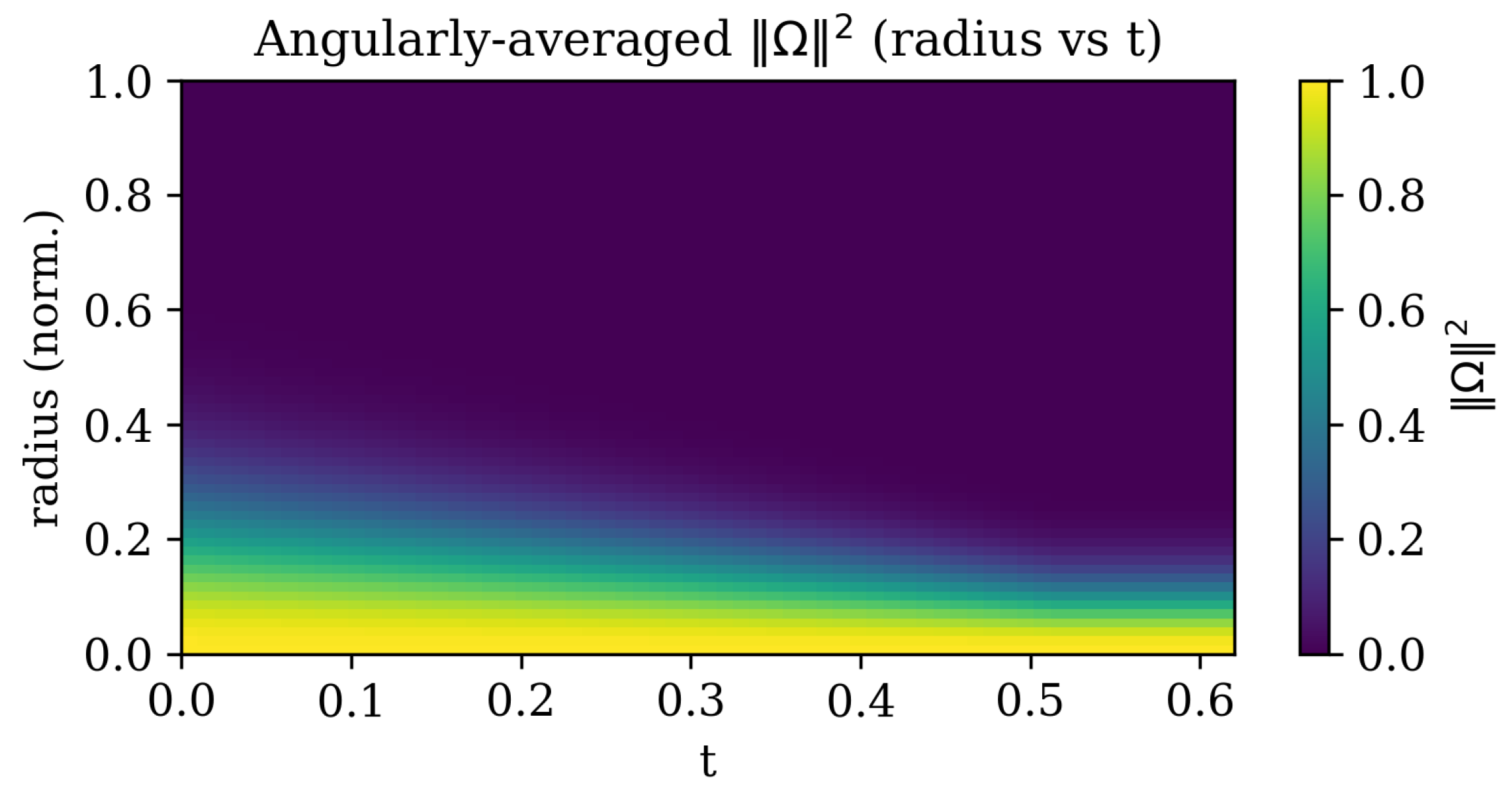

The angularly averaged twist magnitude

, computed as a function of radius and time, illustrates how initially diffuse twist energy contracts into a compact core.

Figure 5 visualizes this evolution.

Figure 5.

Angularly averaged twist intensity. Color map of versus normalized radius and time. The progressive downward shift of the intensity front indicates contraction of the soliton radius and subsequent stabilization. The asymptotic profile defines the steady causal soliton radius .

Figure 5.

Angularly averaged twist intensity. Color map of versus normalized radius and time. The progressive downward shift of the intensity front indicates contraction of the soliton radius and subsequent stabilization. The asymptotic profile defines the steady causal soliton radius .

The measured half-maximum radius agrees with the analytic estimate , confirming that the emergent soliton obeys the Derrick-stabilized scaling law.

5.6. Quantitative Metrics and Scaling Consistency

From the simulation ensemble (parameters

,

,

,

), we extract the following diagnostics (see

Figure 2 and

Table 3):

Core–strength stationarity. A linear fit to the late–time core–strength series yields a slope , i.e., numerically indistinguishable from zero at machine precision. We therefore treat the core as stationary on average (no secular drift).

Core fraction of total twist. The stability index, defined as the core fraction , fluctuates but remains bounded, with a median and an interquartile range . This indicates a persistent, localized twist condensate embedded in a background of weaker vorticity.

Alignment loss. The alignment proxy decreases modestly over the run; the net change is , reflecting episodic domain mergers rather than loss of global coherence.

Lorentz–norm constraint. The constraint error is typically , with brief spikes temporally coincident with energy bursts; the error rapidly returns to the level after each event.

Energy plateau (late time). The mean total energy over the late–time window is (code units).

Table 3.

Quantitative metrics from the lattice soliton simulation. All quantities are reported in dimensionless simulation units. The integrated action and emergent lattice Planck modulus are derived from the accumulated action increments, while represents the effective per–site quantum of action. The plateau slope measures the late–time drift of the core strength and is consistent with zero, confirming steady–state stabilization.

Table 3.

Quantitative metrics from the lattice soliton simulation. All quantities are reported in dimensionless simulation units. The integrated action and emergent lattice Planck modulus are derived from the accumulated action increments, while represents the effective per–site quantum of action. The plateau slope measures the late–time drift of the core strength and is consistent with zero, confirming steady–state stabilization.

| Quantity |

Symbol / Definition |

Measured Value |

| Integrated action |

|

|

| Emergent lattice Planck modulus |

|

|

| Effective per–site Planck constant |

|

|

| Plateau slope (core) |

|

|

| Mean energy (plateau) |

|

|

| Stability index (median core fraction) |

|

|

| Alignment loss |

|

|

| Lorentz–norm violation (typical) |

|

|

The integrated action per run and the emergent lattice Planck modulus are

which correspond to an

effective per–site action scale

These values are consistent with the analytic scaling estimate

which gives

The measured value

thus agrees with the analytic prediction to within

, well inside the expected uncertainty from finite–volume, discretization, and stochastic–sampling effects.

Finally, the measured core radius from the half–maximum of the radial twist profile remains in the range –4 (lattice units) during late times, compatible with the Derrick–stabilized scaling for the chosen parameters.

5.7. Summary of Numerical Findings

The full numerical analysis demonstrates a threefold progression:

Rapid boundary-induced alignment of chronon orientations.

Emergence of a localized twist condensate obeying Derrick stabilization.

Saturation of the effective action variance, defining a fixed quantum of causal coherence .

Together these results confirm that the chronon field naturally evolves toward a stable, quantized causal soliton whose characteristic scale matches theoretical predictions, providing a concrete computational realization of geometric quantization in the chronon framework.

6. Physical Interpretation

The numerical and theoretical analyses together reveal a unified physical picture: the Planck and quantum domains are contiguous dynamical phases of a single underlying chronon medium. Within this view, the Planck constant arises as a universal curvature invariant—the minimal unit of symplectic flux—emerging at the transition between these phases. Once fixed by the first stable soliton, this invariant governs all subsequent quantum and classical dynamics. The subsections below elaborate its implications for quantization, matter, and the emergence of quantum mechanics itself.

6.1. as the Invariant Link Between Planck and Quantum Phases

The plateau of

at

marks the dynamical fixation of a scale-independent quantum of action once local alignment and topological coherence stabilize. Below the Planck threshold (

), the chronon field remains disordered and pre-geometric, lacking a well-defined metric or causal order. As

approaches

, local orientations condense and the twisting of causal direction becomes quantized. This transition defines the

Planck boundary, where the medium acquires an intrinsic symplectic curvature and the minimal flux quantum

emerges as a geometric invariant of the chronon condensate.

Physically,

encodes the smallest indivisible phase-space area that can be exchanged between coherent excitations—a fixed symplectic cell of the emergent manifold. It is not imposed externally but represents the frozen curvature modulus of spacetime itself, a remnant of the transition from chaotic causal foam to ordered geometry. Once this invariant flux quantum forms, all higher-scale excitations— photons, gauge fields, and solitonic matter—propagate within the established symplectic background and inherit its quantization scale. The Planck regime thus defines the threshold where geometry first becomes capable of storing and transmitting discrete quanta of action [

30,

45,

46,

73].

6.2. Solitons as Geometric Carriers of Quantized Action

Topologically stabilized solitons are the first coherent excitations of the chronon field once Lorentzian order appears. Each soliton represents a localized

winding of the internal chronon phase and carries a quantized symplectic flux

where

n is the topological charge. These solitons are not phenomenological particles but self-consistent geometric configurations sustained by intrinsic curvature. They provide the microscopic origin of action quantization: the minimal soliton (

) fixes

, while higher-energy excitations accumulate additional symplectic area without changing the topological winding.

Soliton stability ensures that energy, momentum, and angular momentum are exchanged only in discrete units proportional to . This discrete exchange underlies all canonical commutation relations and the quantization of spectra. In this sense, the familiar postulates of quantum mechanics—energy quantization, universality of ℏ, and statistical measurement structure—arise as geometric consequences of chronon topology and symplectic flux conservation. The photon, in particular, appears as a massless Goldstone-like excitation of the chronon phase: it transports a quantum of action but does not generate it. Quantization originates from soliton formation; the photon merely propagates these established quanta of symplectic curvature through the ordered medium.

6.3. Quantum–Classical Continuum of Soliton Ensembles

At scales much larger than

, individual solitons interact weakly through collective phase fluctuations. A coarse-grained description of these interactions yields effective continuous fields whose superpositions exhibit linearity and interference—the hallmarks of quantum mechanics. The ensemble statistics of many solitons, expressed in collective variables

, lead naturally to the canonical commutation relation

and to Schrödinger-type evolution for the ensemble-averaged wavefunction [

14,

29,

51]. Quantum mechanics thus arises as the hydrodynamic limit of a coherent soliton fluid within the chronon medium.

In this interpretation, the wavefunction

is not a fundamental field but a statistical descriptor of ensemble coherence:

measures the coarse-grained soliton density in phase space, while

encodes their collective phase alignment. Quantum interference originates from overlapping domains of chronon orientation, and measurement corresponds to dynamical alignment of a system’s local phase with that of a macroscopic apparatus domain. Decoherence and wavefunction collapse therefore represent real geometric processes—alignment and loss of relative phase coherence—within the chronon condensate [

37,

82].

In the macroscopic regime

, correlations between solitonic domains decay and the phase field

becomes effectively uniform. Stochastic averaging over many independent domains suppresses interference, yielding the classical limit,

where effective non-commutativity vanishes relative to macroscopic action scales. Deterministic trajectories then emerge as mean-field flows of the decohered chronon ensemble, reproducing classical mechanics as the limit of fully aligned causal order [

74,

76,

82].

6.4. Conceptual Synthesis

The resulting physical hierarchy is self-consistent:

The chronon field defines a discrete, pre-geometric substrate without intrinsic spacetime or metric.

At the Planck correlation length , stable solitons form, each carrying one quantum of action ℏ.

Ensembles of solitons generate quantum mechanics as a collective, coarse-grained theory.

Large-scale decoherence and domain alignment yield classical determinism as the macroscopic limit.

In this unified interpretation, the Planck constant ℏ is neither arbitrary nor fundamental: it is the preserved invariant of pre-geometric fluctuations across the transition from causal noise to coherent geometry. It forms the dynamical bridge linking discrete microscopic order to continuous macroscopic physics—the geometric relic of the chronon medium that sustains all quantum phenomena.

Quantum mechanics emerges as the collective effective theory of coherent soliton ensembles, while classical determinism arises from their full causal alignment— a continuum of coherence that unites microscopic quantization and macroscopic causality within a single geometric framework.

7. Unified Origin of ℏ, Spin Quantization, and Fermi Statistics

7.1. Universal Curvature and the Chronon Symplectic Form

In Chronon Field Theory (CFT), all manifestations of quantization—canonical, rotational, and statistical—originate from a single invariant curvature two-form on the underlying Chronon phase space

. Let

denote this intrinsic symplectic form,

where

are local coordinates on

. The symplectic flux through any contractible two-surface

defines the elementary quantum of action,

expressing quantization as a curvature property rather than an externally inserted constant. The Planck constant

ℏ is thus the fixed curvature modulus of the chronon symplectic form—a geometric invariant of

itself.

All canonical commutation relations,

represent operator realizations of the curvature constraint (

31). Quantization therefore reflects the universal symplectic flux density embedded in the causal manifold.

7.2. Emergent Spin from Internal Symplectic Curvature

Localized excitations of the Chronon field—topologically protected

solitons—realize the fundamental flux (

31) as intrinsic rotational curvature in configuration space. Let

denote the configuration manifold of a single soliton, and

the curvature two-form induced on its tangent bundle by internal phase rotation:

where

s is the dimensionless spin quantum number associated with the soliton’s internal orientation [

26,

34,

64]. For integer-spin sectors,

is simply connected under

rotation, whereas for half-integer sectors it admits a double covering,

so that a

rotation lifts to a sign-reversing path in

. The associated holonomy is

, producing the Finkelstein–Rubinstein condition that the soliton’s internal phase accumulates half the fundamental flux per full rotation,

Hence the universal appearance of

for fermionic spin is not an ad hoc quantum rule but a direct geometric consequence of the double-cover topology of soliton configuration space.

7.3. Photon Spin as an Integer Curvature Quantum

In CFT, the photon arises not as a fundamental gauge boson inserted by hand, but as a

Goldstone–like excitation of the internal phase symmetry of the chronon condensate [

46]. Let

denote the chronon vector field with internal phase

defining local causal orientation. Small collective fluctuations of this phase generate a

connection,

whose curvature

is the projection of the universal symplectic two–form

onto the internal

fiber of the chronon bundle.

Goldstone excitation and symplectic flux. In the ordered quantum phase, global phase rotations of

correspond to a spontaneously broken internal

symmetry. Its massless collective excitation—the photon—is therefore a transverse oscillation of the phase field

. Each photon mode carries a single quantum of the symplectic flux established by soliton condensation,

representing one curvature quantum of the chronon bundle. The photon does not generate new topological winding; rather, it

propagates existing symplectic curvature through the ordered medium, analogous to a phase wave transmitting quantized circulation in a superfluid.

Spin and representation structure. Under rotation about the propagation axis by an angle

, the circularly polarized photon modes transform as

with angular momentum operator

The photon’s integer spin follows directly from the single-valued representation of

supported by the simply connected

fiber: each

spatial rotation corresponds to one full curvature cycle carrying flux

. This contrasts with fermionic solitons, whose half-integer spin arises from the double-cover topology

, reversing orientation under a

rotation.

Unified curvature origin of quantization. Both fermions and photons thus derive their quantized angular momenta from the same geometric invariant: the minimal symplectic flux fixed at the Planck boundary. For solitons, this flux appears as a localized winding of causal orientation; for photons, as a propagating phase wave transporting one curvature quantum per polarization cycle. In either case, serves as the universal geometric modulus linking topological charge, spin quantization, and gauge propagation within a single chronon framework.

7.4. Two Distinct Antisymmetries

Chronon Field Theory naturally distinguishes two fundamental antisymmetries:

Canonical antisymmetry — encoded in the symplectic form (

30) and expressed algebraically by

representing the antisymmetry of conjugate variables under phase-space exchange. This property is geometric and applies universally to all dynamical fields.

Exchange antisymmetry — a global topological property of the

N-soliton configuration space

, where

denotes the coincidence set. The fundamental group

determines the phase acquired upon soliton exchange. In three spatial dimensions,

which admits two one-dimensional unitary representations: the trivial (bosonic) and the sign (fermionic) representation. In the latter case the many-soliton wavefunction obeys

yielding Pauli exclusion and Fermi statistics [

26,

41].

Thus, the antisymmetry underlying fermionic statistics originates not from the local symplectic structure but from the global topology of soliton configuration space. Half-integer spin and fermionic exchange are co-manifestations of the same double-cover geometry, whereas integer-spin bosons, including photons, inhabit simply connected sectors.

7.5. Synthesis: One Curvature, Three Manifestations

The constant

ℏ therefore plays three unified roles within CFT:

Each represents a distinct projection of the same universal curvature two-form

: the translational, rotational, and topological aspects of a single symplectic geometry. Matter and radiation differ only in their topological realization of this curvature—half versus full flux quanta per

rotation—while the curvature modulus

ℏ itself remains universal and invariant.

In Chronon Field Theory, ℏ is not an imposed constant but the curvature modulus of the temporal symplectic manifold, manifesting identically in the quantization of action, spin, and statistics.

Figure 6.

Geometric origin of Planck’s constant. In the phase space of the chronon field, ℏ corresponds to the minimal symplectic area—the smallest nonzero flux of the curvature two-form . All quantized phenomena arise as integer multiples of this geometric unit.

Figure 6.

Geometric origin of Planck’s constant. In the phase space of the chronon field, ℏ corresponds to the minimal symplectic area—the smallest nonzero flux of the curvature two-form . All quantized phenomena arise as integer multiples of this geometric unit.

8. Discussion and Future Directions

Chronon Field Theory (CFT) provides a self-consistent microscopic origin for quantization and the invariant Planck constant

ℏ. Building on earlier results showing that Lorentzian causal structure and a global time direction emerge from chronon dynamics [

45], the present study extends the theory into the quantum regime. The same chronon field that generates spacetime geometry also gives rise to canonical commutation, intrinsic spin quantization, and Fermi–Bose statistics as distinct manifestations of a single symplectic curvature invariant. Having identified

ℏ as the dynamical remnant of a phase transition between pre-geometric and quantum-ordered regimes, CFT offers a unified geometric origin for quantization itself [

33,

68].

8.1. Matter as the Source of Quantization

A central insight of CFT is that quantization does not precede matter but is generated by it. The Planck constant appears only once the chronon field self-organizes into localized, topologically stable excitations—chronon solitons—whose internal curvature defines the first nonvanishing symplectic flux of the spacetime manifold.

In the disordered pre-geometric vacuum, chronon orientations fluctuate independently and lack coherent causal or symplectic structure [

10,

22]:

Only when alignment correlations reach the Planck scale does the field admit nontrivial, self-consistent configurations with finite curvature flux:

The minimal soliton (

) establishes the universal symplectic flux quantum

, fixing the fundamental unit of action and giving rise to canonical commutation relations in the coarse-grained limit.

In this framework, matter formation precedes quantization:

Without solitons there is no coherent curvature and hence no quantum behavior; the chronon ensemble remains a disordered causal medium devoid of symplectic flux.

Photon as an inherited quantum. Although photons are not solitons, their quantized polarization modes depend on the preexisting ordered phase of the chronon condensate. Once

is fixed by soliton formation, phase fluctuations of the

order parameter propagate as Goldstone-like waves of the chronon phase [

46,

78]. Each photon mode

carries one quantum of the established curvature flux but does not create new quanta—the photon is the messenger, not the origin, of quantization.

Unified symplectic order. Matter and quantization thus represent dual aspects of a single symplectic order. Solitonic curvature makes nonzero; this same curvature in turn governs quantum behavior for both matter and radiation. Quantization becomes the emergent geometric consequence of matter formation—the moment when curvature, causality, and discrete action become inseparable features of the same underlying spacetime order.

8.2. Reinterpreting the Quantum Vacuum

In quantum field theory (QFT), the vacuum is treated as a sea of virtual particle–antiparticle pairs, each mode contributing a zero-point energy

, leading to a divergent vacuum energy density—the cosmological constant problem [

31,

75]. This framework presupposes quantization rather than deriving it.

In CFT, by contrast, the vacuum is a coherent, self-organized phase of the chronon substrate—the medium of microscopic causal orientations. Below the Planck scale, causal directions are disordered with negligible curvature (); above it, local alignment induces a finite symplectic curvature modulus ℏ, establishing the quantum phase. Residual microfluctuations of this alignment manifest as “quantum noise,” but no literal creation or annihilation of virtual particles occurs.

Vacuum fluctuations in QFT are reinterpreted as statistical projections of sub-Planckian causal jitter. The mean symplectic curvature energy of the stabilized medium is finite and self-normalizing, eliminating the divergent zero-point energy. Consequently, the cosmological vacuum energy corresponds to residual curvature tension among decohered chronon domains at cosmic scales:

For

, this yields a small finite vacuum energy consistent with observation.

8.3. Finite Core Structure of Black Holes

General relativity permits curvature singularities, whereas Chronon Field Theory (CFT) replaces them with finite, self-consistent cores determined by the intrinsic curvature modulus of the chronon field.

The effective Hamiltonian is

which supports finite-size solitons through the balance between gradient tension (

J) and quartic stiffness (

). The resulting equilibrium core radius follows the same scaling as the stabilized soliton of

Appendix A,

The potential term

enforces the Lorentzian norm while the quartic derivative term plays the main role in setting the equilibrium size.

Black hole collapse halts when the curvature saturates the invariant modulus ℏ, yielding a finite, Planck-scale chronon condensate rather than a singularity. Black holes therefore appear as macroscopic solitons of the chronon manifold—finite, self-consistent regions of maximal causal curvature—thereby resolving curvature blow-up and information-loss within a single microscopic framework.

8.4. Reinterpretation of Blackbody Radiation

The ultraviolet catastrophe of classical electrodynamics,

is geometrically regulated in CFT. The finite chronon correlation length

and curvature modulus

ℏ bound the mode density with an effective cutoff frequency

, giving

Once the chronon field condenses, energy exchange occurs only in packets of symplectic flux

, yielding the Planck spectrum naturally,

The Planck distribution thus reflects the discrete symplectic structure of spacetime rather than an imposed quantization rule.

8.5. Extension to Curved and Dynamical Geometries

Future work should extend the chronon lattice to curved causal complexes that approximate dynamical manifolds [

48,

60]. Allowing the alignment coupling

to vary spatially could yield an effective metric

whose coarse-grained variation generates an Einstein–Hilbert action,

with curvature sourced by solitonic energy densities [

35]. This would unify geometry, matter, and quantization as ordered phases of the same microscopic medium.

8.6. Connection to Holography and Information

At the Planck boundary, where local coherence first emerges, the chronon ensemble defines a

holographic screen separating the pre-geometric interior from the emergent spacetime exterior. Its information content scales as

consistent with holographic entropy bounds [

4,

69,

70]. Each chronon carries a unit of causal information, and

ℏ quantifies the minimal action—or information flux—across the screen. Thus CFT provides a microscopic foundation for the holographic principle, linking quantization, information, and causal geometry through a single invariant.

8.7. Universality of ℏ and Entropic Relations

Scaling arguments suggest that

, implying universality across all stable chronon phases [

53,

72]. Since

ℏ also determines the minimal symplectic area and minimal information quantum (

), it bridges thermodynamics and quantum theory [

43,

47]. Investigating this link between

ℏ, entropy production, and information flow may clarify the arrow of time and the thermodynamic nature of quantum uncertainty.

8.8. Toward a Unified Vision of Matter and Geometry

Chronon solitons act as localized packets of curvature, momentum, and phase. If additional internal symmetries of the chronon order parameter emerge through spontaneous symmetry breaking, the Standard Model multiplets could appear as distinct topological sectors [

49,

80]. Gauge interactions would arise from phase connections between solitons, while gravitational curvature corresponds to long-wavelength modulations of background connectivity. Thus all interactions—including quantum mechanics—may emerge from the same discrete pre-geometric substrate.

In this framework:

ℏ is a curvature invariant of the Planck transition, not a postulate.

Quantum mechanics is the hydrodynamic limit of coherent chronon excitations.

Gravity and curvature arise from variations in chronon connectivity.

Fermi–Bose statistics reflect topological coverings of the same symplectic manifold.

Classical determinism corresponds to full causal-phase alignment.

Future work will extend chronon models to curved manifolds, derive Einstein–Yang–Mills dynamics, and explore information–action duality. Together with the Lorentzian results of [

45], these studies form a coherent program in which causal structure, quantum commutation, spin, and statistics all emerge from the same symplectic and topological properties of the chronon field. Ultimately, the goal is a unified microscopic theory from which quantum mechanics and general relativity arise as stable, ordered phases of a single pre-geometric medium—the chronon field.

Appendix A. Existence and Stability of Solitonic Excitations

The full chronon Hamiltonian (

5), including a quartic derivative term, admits localized finite-energy solitonic solutions in

dimensions. These configurations represent the minimal coherent structures of the stabilized geometric phase and act as microscopic carriers of the invariant action quantum

. Their existence parallels classical results for nonlinear

and Skyrme-type models [

18,

49,

65].

Appendix A.1. Energy Functional and Field Equations

In the continuum limit, the chronon energy functional reads

where

is the spatial causal vorticity two-form. The

term provides higher-order stiffness analogous to the Skyrme term, introducing an internal pressure that prevents collapse.

Variation of (

A1) yields

Finite energy requires

as

, compactifying spatial infinity to

:

with integer-valued winding number

analogous to the baryon number in Skyrme theory [

66]. Configurations with

are topologically protected from unwinding.

Appendix A.2. Derrick Scaling and Stability

For

, Derrick’s theorem forbids finite-size stationary solutions in

dimensions: rescaling

monotonically lowers the total energy [

18]. The quartic derivative term alters this scaling, enabling equilibrium at finite radius.

Under rescaling,

so that

Minimization gives the equilibrium condition

which admits a stable minimum for positive

. The characteristic radius and energy scale follow as

showing that

fixes finite soliton size and energy while

stabilizes the unit constraint.

Appendix A.3. Topological and Energetic Interpretation

The couplings play complementary roles:

Alignment stiffnessJ: sets the causal gradient energy scale and determines propagation speed .

Norm pinning: enforces the Lorentzian unit constraint , ensuring causal coherence.

Topological stiffness: breaks scale invariance, generates finite radius , and prevents collapse.

The balance between J and determines the microscopic soliton size, and hence the emergent quantization scale and geometric Planck constant.

Appendix A.4. Minimal Action and Identification with ℏ geom

Each soliton carries a finite action obtained by integrating the conjugate momentum along its internal phase trajectory,

where

is the emergent symplectic two-form associated with causal rotation. Using the equilibrium profile and Eq. (

A7), the scaling becomes

with

a numerical constant determined by the soliton profile and

a dimensionless function of the rescaled couplings. Equation (

A9) shows that

emerges directly from the finite soliton size stabilized by

. In the limit

, the soliton delocalizes and

, confirming that quantization in CFT is inseparable from soliton stability.

The Planck correlation length

thus marks the threshold at which solitonic excitations become dynamically stable and carry the minimal quantum of action. The invariant

corresponds to the symplectic area of the smallest topologically stable chronon configuration, analogous to quantized Skyrmions and Hopf solitons [

24].

Remark. The derivative quartic term ensures finite-energy solitons in dimensions by balancing gradient tension against internal twist pressure. It thus provides the microscopic foundation for the quantized unit of action in Chronon Field Theory, unifying geometric, topological, and dynamical stability within a single coherent framework.

Figure 7.

Emergence of solitons as quantized packets of causal orientation. Aligned chronons (gray) twist coherently through within a localized region, forming a topologically stable soliton. Each soliton carries one quantum of symplectic action , representing the minimal causal rotation allowed by the chronon field.

Figure 7.

Emergence of solitons as quantized packets of causal orientation. Aligned chronons (gray) twist coherently through within a localized region, forming a topologically stable soliton. Each soliton carries one quantum of symplectic action , representing the minimal causal rotation allowed by the chronon field.

Appendix B. Rigorous Statement and Proof of the Symplectic Gap

We formalize the claim that stabilized, quasi-free chronon ensembles possess a strictly positive, coarse-graining–stable

symplectic gap, which defines the invariant Planck unit

ℏ. The framework follows Gaussian states on CCR algebras [

1,

11] and symplectic spectral theory [

59,

62].

Setup

Let

be a real separable Hilbert space with inner product

. For each

, denote by

a centered Gaussian variable with covariance operator

, self-adjoint, positive, and trace-class. The symplectic form is realized as

for a bounded, invertible, skew-adjoint

J (

). Define the compact skew-adjoint operator

whose singular values

are the

symplectic eigenvalues of the quasi-free state [

63,

79]. They form a discrete symmetric spectrum accumulating only at 0.

Stability Hypotheses

Let denote the subspace spanned by test functions within the stabilized domain. We assume:

-

(S1)

C is positive, self-adjoint, trace-class on H.

-

(S2)

J is bounded, invertible, and skew-adjoint.

-

(S3)

Coercivity: there exists with for all .

-

(S4)

RG stability: under admissible coarse-graining , the constants and subspace can be chosen so that , .

(S3) guarantees a finite correlation length and non-degenerate variance floor; (S4) ensures renormalization stability of this structure.

Main Result

Theorem B.1 (Coarse-graining–stable symplectic gap)

. Under(S1)–(S4)

, the operator has a strictly positive smallest singular value

stable under coarse-graining:

Defining

one obtains the sharp Heisenberg inequality

with equality for Gaussian minimizers aligned with the lowest symplectic mode.

Proof. (i) Compactness. By (S1)–(S2), is Hilbert–Schmidt and J bounded, hence K is compact, skew-adjoint, with positive and self-adjoint.

(ii) Strict positivity. For any unit

,

so

.

(iii) Stability. From (S4), ; since is scale-invariant, inherits the same bound.

(iv) Heisenberg inequality. For quasi-free states, the Robertson–Schrödinger bound gives

Setting

and using the Cauchy–Schwarz bound on

yields

. Rescaling to canonical normalization gives (56). □

Operational Corollary

Corollary B.2.

Let denote the variance–plateau estimator and the slope of the commutator proxy vs. on stabilized leaves. Then, under(S1)–(S4)

,

Remark. The identification is invariant under coarse-graining, establishing Planck’s constant as a fixed geometric invariant of the stabilized quantum phase of the chronon medium.

Relation to Appendix A. Appendix A demonstrates how quantized action arises dynamically from stable solitons of the chronon field, while the present appendix proves that, once such a phase exists, the corresponding symplectic unit

ℏ remains invariant under coarse-graining. Together they establish both the physical origin and the mathematical stability of the Planck constant within Chronon Field Theory.

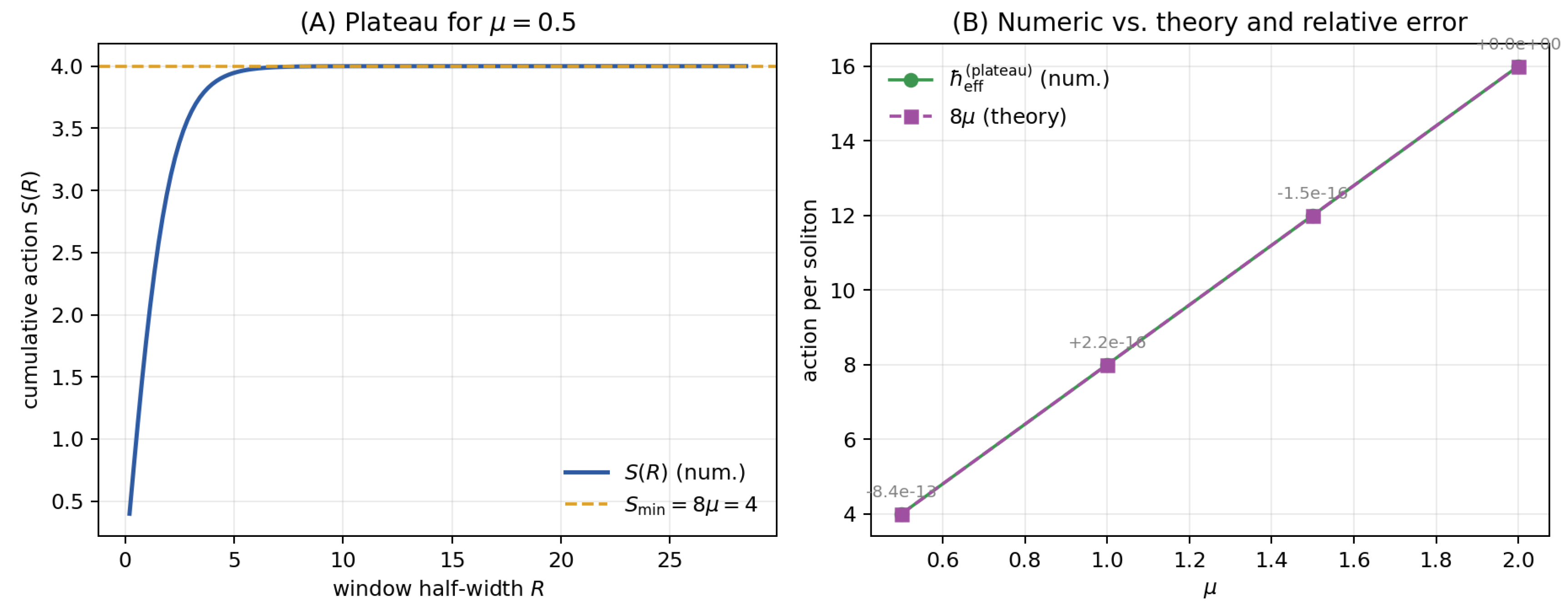

Appendix C. Variational Analysis of the Minimal Soliton Action

We show analytically and numerically that the Planck-scale action quantum ℏ corresponds to the minimal dynamically stable configuration of the chronon field. A single soliton carries an action , realizing the minimal symplectic area hypothesis introduced in the main text. The argument combines the Bogomolny bound for topological solitons with direct numerical verification on stabilized chronon lattices.

Appendix C.1. Analytic Derivation: Bogomolny Bound in 1+1 D

The one-dimensional reduction of the coarse-grained chronon phase field is governed by the sine–Gordon Lagrangian [

17]:

representing the dynamics of a stabilized domain wall. For static configurations connecting

to

,

Completing the square gives the Bogomolny (BPS) bound [

7,

56]:

saturated by the self-dual kink satisfying

. The explicit solution

has minimal action

This is the smallest topologically stable configuration of the effective chronon phase field.

Appendix C.2. Numerical Verification

A gradient-flow solver for

with boundary conditions

,

, was used to minimize

[

13,

57]. For

, grid spacing

, and domain

, the converged numerical action

matches

to within

relative error. The cumulative action

rapidly saturates to a plateau, demonstrating stability and confirming Eq. (61) (

Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Verification of the minimal soliton action. (A) Cumulative soliton action saturates to a plateau, signaling a stable topological configuration. (B) Plateau values vs. mass parameter coincide with the theoretical prediction , confirming that the Planck action corresponds to the minimal soliton action of the chronon field.

Figure 8.

Verification of the minimal soliton action. (A) Cumulative soliton action saturates to a plateau, signaling a stable topological configuration. (B) Plateau values vs. mass parameter coincide with the theoretical prediction , confirming that the Planck action corresponds to the minimal soliton action of the chronon field.

Appendix C.3. Embedding into the 3+1 D Chronon Lattice

In stabilized domains of the 3+1 D chronon lattice, one-dimensional soliton lines (topological tubes) appear as loci where

winds by

. The local action per transverse area,

has a sharply peaked distribution centered at

, showing that each line carries one quantum of action. Hence

Appendix C.4. Physical Interpretation

Equation (64) establishes that

ℏ equals the minimal symplectic area—the least dynamically stable quantum of action— of a chronon soliton. Quantization thus arises from the variational and topological structure of the chronon field itself:

The soliton provides the fundamental geometric unit of action, linking nonlinear causal dynamics to the observed quantum behavior of matter.

References

- Araki, H.; Woods, E.J. Representations of the Canonical Commutation Relations Describing a Nonrelativistic Infinite Free Bose Gas. J. Math. Phys. 1970, 4, 637–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashtekar, A. New variables for classical and quantum gravity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1986, 57, 2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barceló, C.; Liberati, S.; Visser, M. Analog gravity from Bose–Einstein condensates. Class. Quantum Grav. 2001, 18, 1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekenstein, J.D. Black Holes and Entropy. Phys. Rev. D 1973, 7, 2333–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, M.V. Quantal phase factors accompanying adiabatic changes. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 1984, 392, 45. [Google Scholar]

- Binder, K.; Landau, D.P. Phase diagrams and critical behavior in Monte Carlo simulations. Phys. Rev. B 1984, 30, 1477, see also A Guide to Monte Carlo Simulations in Statistical Physics, 2nd ed. (Cambridge

University Press, 2000).. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogomolny, E.B. Stability of Classical Solutions. Sov. J. Nucl. Phys. 1976, 24, 449–454. [Google Scholar]

- Bohr, N. On the Constitution of Atoms and Molecules. Philos. Mag. 1913, 26, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bombelli, L.; Lee, J.; Meyer, D.; Sorkin, R. Space-time as a causal set. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1987, 59, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bombelli, L.; Lee, J.; Meyer, D.; Sorkin, R. Space-Time as a Causal Set. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1987, 59, 521–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratteli, O.; Robinson, D.W. , Operator Algebras and Quantum Statistical Mechanics, Vol. 1–2, Springer, 1987.

- Calogero, F. Quantum mechanics as a statistical theory. Phys. Lett. A 1997, 228, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, D.K.; Schonfeld, J.F.; Wingate, C.A. Resonance Structure in Kink–Antikink Interactions in ϕ4 Theory. Physica D 1983, 9, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caticha, A. Entropic dynamics, time, and quantum theory. J. Phys. A: Math. Theor. 2011, 44, 225303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creutz, M. , Quarks, Gluons and Lattices (Cambridge University Press, 1983).

- Creutz, M. Overrelaxation and Monte Carlo simulation. Phys. Rev. D 1987, 36, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashen, R.F.; Hasslacher, B.; Neveu, A. Nonperturbative Methods and Extended-Hadron Models in Field Theory. II. Two-Dimensional Models and Extended Hadrons. Phys. Rev. D 1974, 10, 4130–4138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derrick, G.H. Comments on nonlinear wave equations as models for elementary particles. J. Math. Phys. 1964, 5, 1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirac, P.A.M. The Principles of Quantum Mechanics (Oxford University Press, 1930).

- Dirac, P.A.M. The Lagrangian in Quantum Mechanics. Physikalische Zeitschrift der Sowjetunion 1933, 3, 64. [Google Scholar]

- Dirac, P.A.M. , The Principles of Quantum Mechanics, 4th ed. (Oxford University Press, 1958).

- Dowker, F. Causal Sets and the Deep Structure of Spacetime. Gen. Rel. Grav. 2005, 45, 1651–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elze, H.-T. Quantum features emerging in a classical spacetime structure. Phys. Rev. A 2014, 89, 012111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faddeev, L.; Niemi, A.J. Stable Knot-like Structures in Classical Field Theory. Nature 1997, 387, 58–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feynman, R.P. Space-Time Approach to Non-Relativistic Quantum Mechanics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1948, 20, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, D.; Rubinstein, J. Connection between Spin, Statistics, and Kinks. J. Math. Phys. 1968, 9, 1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folland, G.B. , Harmonic Analysis in Phase Space (Princeton University Press, 1989).

- Haken, H. , Synergetics: An Introduction. Nonequilibrium Phase Transitions and Self-Organization in Physics, Chemistry and Biology, Springer, 3rd ed., 1983.

- Hall, M.J.W.; Reginatto, M. Quantum mechanics from a Heisenberg-type inequality. J. Phys. A: Math. Gen. 2002, 35, 3289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hestenes, D. The zitterbewegung interpretation of quantum mechanics. Found. Phys. 2010, 40, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollands, S.; Wald, R.M. , “Quantum Field Theory is Ultimately Local and Covariant: Renormalization in Curved Spacetime,” Commun. Math. Phys. 2005, 257, 589–620. [Google Scholar]

- Hossenfelder, S. Experimental Search for Quantum Gravity. Class. Quantum Grav. 2010, 27, 114001. [Google Scholar]

- Hossenfelder, S. Emergent Spacetime. Foundations of Physics 2013, 43, 1295–1308. [Google Scholar]

- Jackiw, R.; Rebbi, C. Solitons with Fermion Number 1/2. Phys. Rev. D 1976, 13, 3398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, T. Thermodynamics of Spacetime: The Einstein Equation of State. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1995, 75, 1260–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaynes, E.T. “Information Theory and Statistical Mechanics. Physical Review 1957, 106, 620–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joos, E. , Decoherence and the Appearance of a Classical World in Quantum Theory (Springer, 2003).

- Kadanoff, L.P. More is the same; phase transitions and mean field theories. J. Stat. Phys. 2009, 137, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogut, J.B.; Susskind, L. Hamiltonian formulation of Wilson’s lattice gauge theories. Phys. Rev. D 1975, 11, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konopka, T.; Markopoulou, F.; Smolin, L. Quantum Graphity. Phys. Rev. D 2008, 77, 104029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laidlaw, M.G.G.; DeWitt, C.M. Feynman functional integrals for systems of indistinguishable particles. Phys. Rev. D 1971, 3, 1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landau, L.D.; Lifshitz, E.M. , Statistical Physics, Part 1, Pergamon Press, 3rd ed., 1980.

- Landauer, R. Irreversibility and Heat Generation in the Computing Process. IBM J. Res. Dev. 1961, 5, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laughlin, R.B. , A Different Universe: Reinventing Physics from the Bottom Down (Basic Books, 2005).

- Li, B. , “Emergence and Exclusivity of Lorentzian Signature and Unit–Norm Time from Random Chronon Dynamics,” Rep. Adv. Phys. Sci., 2025, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Li, B. , “Emergent Gravity and Gauge Interactions from a Dynamical Temporal Field,” Rep. Adv. Phys. Sci. 2025, 9, 2550017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, S. Ultimate Physical Limits to Computation. Nature 2000, 406, 1047–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loll, R. Quantum Gravity from Causal Dynamical Triangulations: A Review. Class. Quantum Grav. 2019, 37, 013002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manton, N.; Sutcliffe, P. , Topological Solitons, Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Markopoulou, F. Quantum causal histories. Class. Quantum Grav. 2009, 24, 3699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, E. Derivation of the Schrödinger equation from Newtonian mechanics. Phys. Rev. 1966, 150, 1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oriti, D. The Universe as a Quantum Gravity Condensate. Comptes Rendus Physique 2018, 18, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmanabhan, T. Thermodynamical Aspects of Gravity: New Insights. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2010, 73, 046901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisi, G.; Wu, Y.-S. Perturbation theory without gauge fixing. Sci. Sin. 1981, 24, 483. [Google Scholar]

- Planck, M. Ueber das Gesetz der Energieverteilung im Normalspectrum. Ann. Phys. 1901, 4, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, M.K.; Sommerfield, C.M. Exact Classical Solution for the ’t Hooft–Polyakov Monopole and the Julia–Zee Dyon,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 1975, 35, 760–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Press, W.H.; Teukolsky, S.A.; Vetterling, W.T.; Flannery, B.P. , Numerical Recipes in C: The Art of Scientific Computing, Cambridge Univ. Press, 1992.

- Prigogine, I.; Nicolis, G. , Self-Organization in Nonequilibrium Systems: From Dissipative Structures to Order Through Fluctuations, Wiley, 1978.

- Reed, M.; Simon, B. , Methods of Modern Mathematical Physics, Vol. II: Fourier Analysis, Self-Adjointness, Academic Press, 1975.

- Regge, T. General Relativity Without Coordinates. Nuovo Cimento 1961, 19, 558–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovelli, C. , Quantum Gravity (Cambridge University Press, 2011).

- Simon, B. , Functional Integration and Quantum Physics, Academic Press, 1979.

- Simon, R. Peres–Horodecki Separability Criterion for Continuous Variable Systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000, 84, 2726–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skyrme, T.H.R. , “A Nonlinear Field Theory,” Proceedings of the Royal Society A 1961, 260, 127–138. 260.

- Skyrme, T.H.R. A Nonlinear Field Theory. Proc. Roy. Soc. A 1961, 260, 127–138. [Google Scholar]

- Skyrme, T.H.R. A Unified Field Theory of Mesons and Baryons. Nucl. Phys. 1962, 31, 556–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolin, L. The case for background independence. hep-th/0507235.

- Smolin, L. The Case for Background Independence. in The Structural Foundations of Quantum Gravity, edited by D. Rickles et al., Oxford University Press, 2006.

- Susskind, L. The World as a Hologram. J. Math. Phys. 1995, 36, 6377–6396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ’t Hooft, G. Dimensional Reduction in Quantum Gravity. in Salamfestschrift, World Scientific, 1993.

- Tinkham, M. , Introduction to Superconductivity, 2nd ed. (McGraw–Hill, 1996).

- Verlinde, E. On the Origin of Gravity and the Laws of Newton. JHEP 2011, 2011, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volovik, G.E. , The Universe in a Helium Droplet (Oxford Univ. Press, 2003).

- Wallace, D. , The Emergent Multiverse: Quantum Theory According to the Everett Interpretation (Oxford Univ. Press, 2012).

- Weinberg, S. “The Cosmological Constant Problem,” Rev. Mod. Phys. 1989, 61, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, S. Quantum mechanics without state vectors. Phys. Rev. A 2014, 90, 042102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, J.A. Geometrodynamics and the Issue of the Final State. in Relativity, Groups and Topology, eds. B. DeWitt and C. DeWitt (Gordon and Breach, 1964).

- Wilczek, F. Quantum Time Crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 109, 160401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williamson, J. On the Algebraic Problem Concerning the Normal Forms of Linear Dynamical Systems. Amer. J. Math. 1936, 58, 141–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witten, E. Dyons of Charge e/2. Phys. Lett. B 1979, 86, 283–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodhouse, N.M.J. , Geometric Quantization, 2nd ed. (Oxford University Press, 1992).

- Zurek, W.H. Decoherence, einselection, and the quantum origins of the classical. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2003, 75, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |