Submitted:

23 October 2025

Posted:

24 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

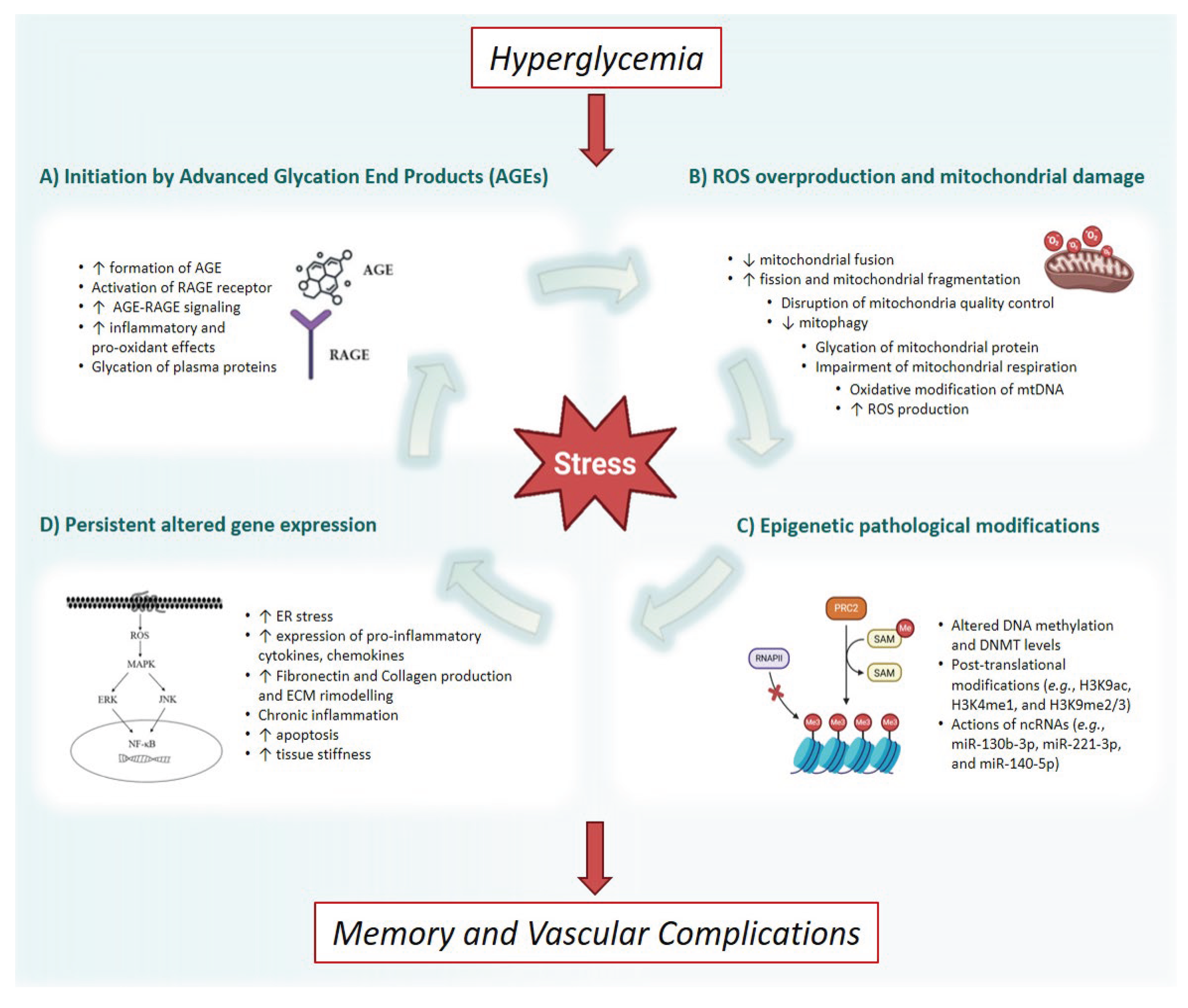

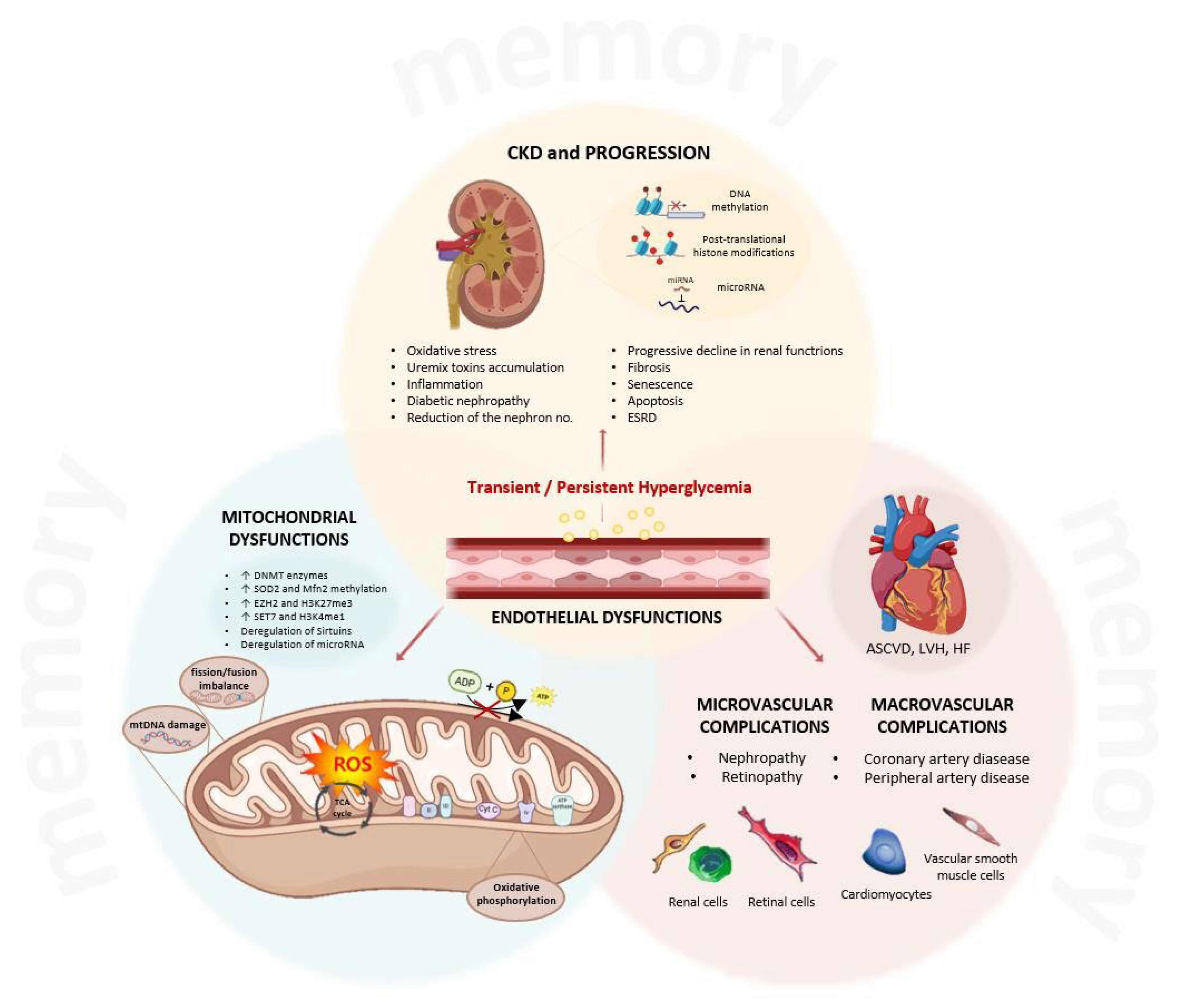

2. The Metabolic Memory

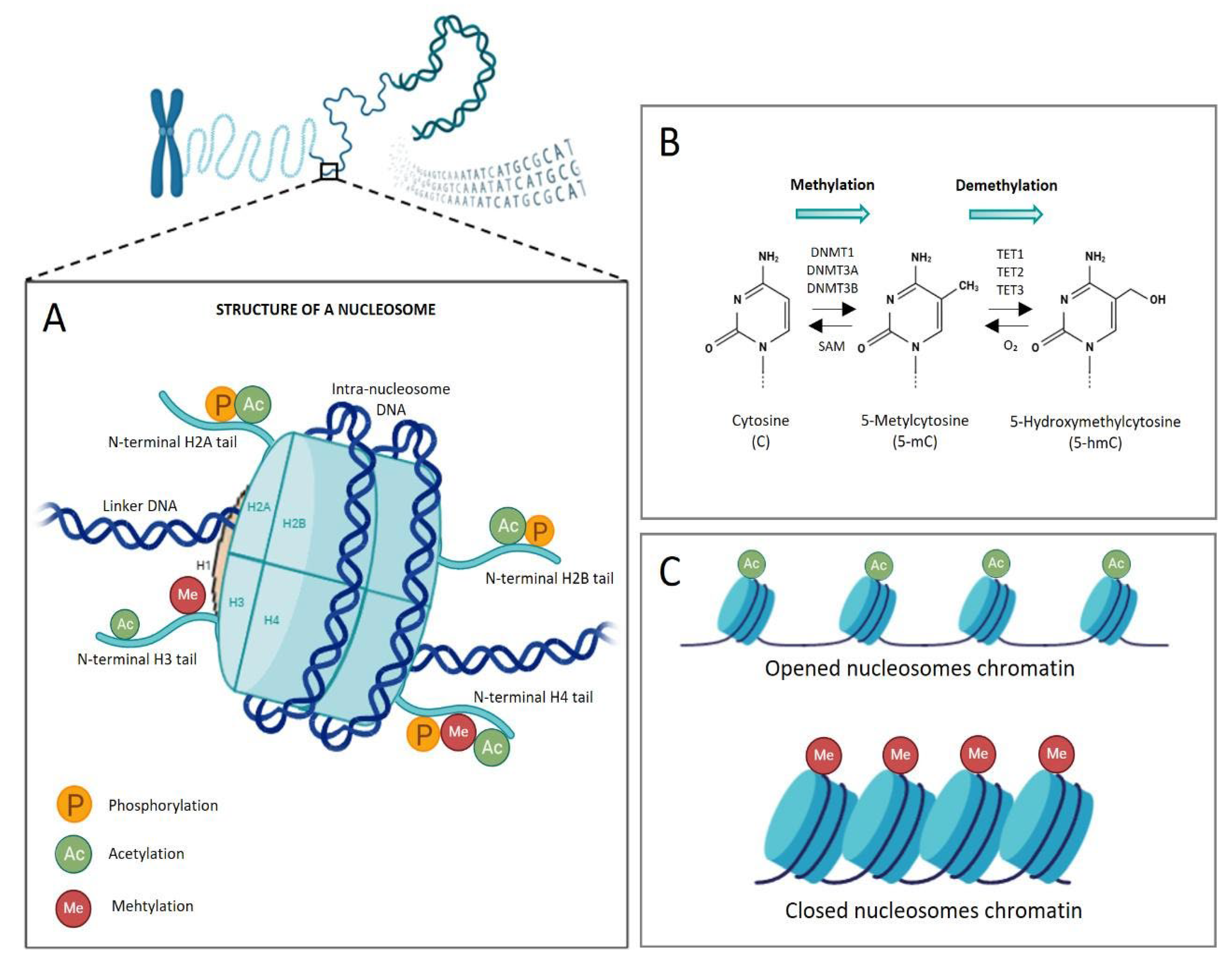

3. Epigenetic Regulation of the Gene Expression

4. The Role of the Epigenetic Memory in Hyperglycemia-Related Ckd Progression

4.1. Histone Modifications and the Activation of Pro-Inflammatory Signaling

4.2. Dna Methylation Status Connected to Renal Disease Progression

4.3. The Role of Sirtuins in the Hyperglycemia-Induced Epigenetic Memory

4.5. Micrornas and the Epigenetic Memory of Hyperglycemia

5. Epigenetic Players as Therapeutic Targets and Biomarkers for Ckd Patients’ Stratification

5.1. Epigenetic Biomarkers in Ckd and Diabetes

5.2. Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors and Mirna-Based Therapies

5.3. Integrating Machine Learning and Multi-Omics

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Abbreviations

| AGE | Advanced glycation end products |

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| AKI | Acute kidney injury |

| AKT | Protein kinase B |

| AR-42 | Histone Deacetylase Inhibitor AR-42 (or HDAC-42) |

| ARE | Antioxidant Response Element |

| AUH | AU RNA binding methylglutaconyl-CoA hydratase |

| BD1 | Bromodomain1 |

| BD2 | Bromodomain2 |

| BET | Bromodomain and extra-terminal domain |

| BRD | Bromodomain containing protein |

| CBX | Polycomb group protein chromobox |

| CaMK2a | Calcium/Calmodulin-Dependent Protein Kinase II alpha |

| CKD | Chronic Kidney Disease |

| COX6A1 | Cytochrome C Oxidase Subunit 6A1 |

| CpG | Cytosine-phosphate-guanine |

| DAPK3 | Death-Associated Protein Kinase 3 |

| DCCT | Diabetes Control and Complications Trial |

| DMNP | DNA Methyltransferases |

| EDIC | Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications Study |

| ELK1 | ETS Transcription Factor ELK1 |

| eGFR | Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate |

| EndMT | Endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition |

| eNOS | Endothelial nitric oxide synthase |

| ERKs | Extracellular signal-regulated kinases |

| ESRD | End-stage renal disease |

| EWAS | Epigenetic-wide association study |

| EZH2 | Enhancer of Zeste Homolog-2 |

| GFR | Glomerular filtration rate |

| GRK5 | G protein-coupled receptor kinase 5 |

| HATs | Histone acetyltransferases |

| H2A | Histone 2A |

| H2B | Histone 2B |

| H3 | Histone 3 |

| H4 | Histone 4 |

| HbA1c | Glycated haemoglobin |

| HDAC | Histone deacetylase |

| H3K9ac | Histone H3 Lysine 9 acetylation |

| H3K4me3 | Histone H3 lysine 4 trimethylation |

| H3K4me1 | Histone H3 Lysine 4 monomethylation |

| H3K27me3 | Histone H3 Lysine 27 trimethylation |

| H3K9me3 | Histone H3 Lysine 9 trimethylation |

| HO-1 | Heme oxygenase-1 |

| IRS2 | Insulin Receptor Substrate 2 |

| JK | Janus Kinase |

| JMJD3 | Lysine demethylase 6B |

| KDIGO | Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes Guidelines |

| KDM | Lysine demethylase |

| KDOQI | Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative Guidelines |

| KMT | Lysine methyltransferase |

| LCAT | Lecithin Cholesterol Acyltransferase |

| LKB1 | Liver kinase B1 |

| MeCP2 | Methyl-CpG-binding protein |

| MAPK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| MESA | Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis |

| miRna | microRNA |

| mtDNA | Mitochondrial DNA |

| mtROS | Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species |

| mTor | Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin |

| mTORC | Target of rapamycin complex |

| NAD+ | Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide |

| Nox1 | NADPH oxidase 1 |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cell |

| NRF2 | Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2-Related Factor 2 |

| PARP | Poly (ADP-ribose) Polymerase |

| P21 | cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1 |

| PINK | PTEN-induced kinase 1 |

| PMPCB | Mitochondrial-processing peptidase subunit beta |

| PRC2 | Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 |

| PTEN | Phosphatase and TENsin homolog |

| PTMs | Post-Translational Modifications |

| RAGE | glycation end-products receptor |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| RPTOR | Regulatory Associated Protein of MTOR complex 1 |

| SAM | S-adenosyl-l-methionine |

| SGI-1027 | DNA Methyltransferase Inhibitor II |

| SIRT | Sirtuin, Silent Mating Type Information Regulation 2 Homolog |

| SLC1A5 | Solute Carrier Family 1 (neutral amino acid transporter), Member 5 |

| SLC27A3 | Solute Carrier Family 27 Member 3 |

| SOD | Superoxide Dismutase |

| TAMM41 | TAM41 Mitochondrial Translocator Assembly and Maintenance Homolog |

| TET | Ten-eleven translocation |

| TSA | Trichostatin A |

| TSFM | Ts translation elongation factor, mitochondrial |

| TXNIP | Thioredoxin-interacting protein |

| UKPDs | United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study |

| VPA | Valproic acid |

References

- Inker, L. A.; Astor, B. C.; Fox, C. H.; Isakova, T.; Lash, J. P.; Peralta, C. A.; Kurella Tamura, M.; Feldman, H. I., KDOQI US commentary on the 2012 KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 2014, 63, (5), 713-35. [CrossRef]

- Rysz, J.; Franczyk, B.; Rysz-Gorzynska, M.; Gluba-Brzozka, A., Are Alterations in DNA Methylation Related to CKD Development? Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, (13). [CrossRef]

- Gilg, J.; Rao, A.; Fogarty, D., UK Renal Registry 16th annual report: chapter 1 UK renal replacement therapy incidence in 2012: national and centre-specific analyses. Nephron Clin Pract 2014, 125, (1-4), 1-27. [CrossRef]

- Coffman, T. M., Under pressure: the search for the essential mechanisms of hypertension. Nat Med 2011, 17, (11), 1402-9. [CrossRef]

- Ho, H. J.; Shirakawa, H., Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Chronic Kidney Disease. Cells 2022, 12, (1), 88. [CrossRef]

- Levey, A. S.; Stevens, L. A.; Coresh, J., Conceptual model of CKD: applications and implications. Am J Kidney Dis 2009, 53, S4-16. [CrossRef]

- Amorim, R. G.; Guedes, G. D. S.; Vasconcelos, S. M. L.; Santos, J. C. F., Kidney Disease in Diabetes Mellitus: Cross-Linking between Hyperglycemia, Redox Imbalance and Inflammation. Arq Bras Cardiol 2019, 112, (5), 577-587. [CrossRef]

- Reidy, K.; Kang, H. M.; Hostetter, T.; Susztak, K., Molecular mechanisms of diabetic kidney disease. J Clin Invest 2014, 124, (6), 2333-40. [CrossRef]

- Turkmen, K., Inflammation, oxidative stress, apoptosis, and autophagy in diabetes mellitus and diabetic kidney disease: the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. Int Urol Nephrol 2017, 49, (5), 837-844. [CrossRef]

- Kato, M.; Natarajan, R., Epigenetics and epigenomics in diabetic kidney disease and metabolic memory. Nat Rev Nephrol 2019, 15, (6), 327-345. [CrossRef]

- Giacco, F.; Brownlee, M., Oxidative stress and diabetic complications. Circ Res 2010, 107, (9), 1058-70.

- Yapislar, H.; Gurler, E. B., Management of Microcomplications of Diabetes Mellitus: Challenges, Current Trends, and Future Perspectives in Treatment. Biomedicines 2024, 12, (9), 1958. [CrossRef]

- Pal, R.; Bhadada, S. K., AGEs accumulation with vascular complications, glycemic control and metabolic syndrome: A narrative review. Bone 2023, 176, 116884. [CrossRef]

- Ng, Z. X.; Kuppusamy, U. R.; Iqbal, T.; Chua, K. H., Receptor for advanced glycation end-product (RAGE) gene polymorphism 2245G/A is associated with pro-inflammatory, oxidative-glycation markers and sRAGE in diabetic retinopathy. Gene 2013, 521, (2), 227-33. [CrossRef]

- de Souza Ferreira, C.; Pennacchi, P. C.; Araujo, T. H.; Taniwaki, N. N.; de Araujo Paula, F. B.; da Silveira Duarte, S. M.; Rodrigues, M. R., Aminoguanidine treatment increased NOX2 response in diabetic rats: Improved phagocytosis and killing of Candida albicans by neutrophils. Eur J Pharmacol 2016, 772, 83-91. [CrossRef]

- Ceriello, A., Hypothesis: the "metabolic memory", the new challenge of diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2009, 86, (1), S2-6.

- El-Osta, A.; Brasacchio, D.; Yao, D.; Pocai, A.; Jones, P. L.; Roeder, R. G.; Cooper, M. E.; Brownlee, M., Transient high glucose causes persistent epigenetic changes and altered gene expression during subsequent normoglycemia. J Exp Med 2008, 205, (10), 2409-17.

- Luna, P.; Guarner, V.; Farias, J. M.; Hernandez-Pacheco, G.; Martinez, M., Importance of Metabolic Memory in the Development of Vascular Complications in Diabetic Patients. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2016, 30, (5), 1369-78. [CrossRef]

- Testa, R.; Bonfigli, A. R.; Prattichizzo, F.; La Sala, L.; De Nigris, V.; Ceriello, A., The "Metabolic Memory" Theory and the Early Treatment of Hyperglycemia in Prevention of Diabetic Complications. Nutrients 2017, 9, (5), 437. [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Sun, Y.; Nie, L.; Cui, A.; Zhao, P.; Leung, W. K.; Wang, Q., Metabolic memory: mechanisms and diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2024, 9, (1), 38. [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Sala, R.; Cagliero, E.; Lorenzi, M., Overexpression of fibronectin induced by diabetes or high glucose: phenomenon with a memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1990, 87, (1), 404-8. [CrossRef]

- Lachin, J.M.; Bebu, I.; Nathan, D.M.; DCCT/EDIC Research Group, The Beneficial Effects of Earlier Versus Later Implementation of Intensive Therapy in Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2021, 44, (10), 2225–30. [CrossRef]

- Wilson-Verdugo, M.; Bustos-Garcia, B.; Adame-Guerrero, O.; Hersch-Gonzalez, J.; Cano-Dominguez, N.; Soto-Nava, M.; Acosta, C. A.; Tusie-Luna, T.; Avila-Rios, S.; Noriega, L. G.; Valdes, V. J., Reversal of high-glucose-induced transcriptional and epigenetic memories through NRF2 pathway activation. Life Sci Alliance 2024, 7, (8), e202302382. [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, T.; Edelstein, D.; Du, X. L.; Yamagishi, S.; Matsumura, T.; Kaneda, Y.; Yorek, M. A.; Beebe, D.; Oates, P. J.; Hammes, H. P.; Giardino, I.; Brownlee, M., Normalizing mitochondrial superoxide production blocks three pathways of hyperglycaemic damage. Nature 2000, 404, (6779), 787-90. [CrossRef]

- Ihnat, M.A.; Thorpe, J.E.; Kamat, C.D.; Szabó, C.; Green, D.E.; Warnke, L.A.; Lacza, Z.; Cselenyák, A.; Ross, K.; Shakir, S.; Piconi, L.; Kaltreider, R.C.; Ceriello, A., Reactive oxygen species mediate a cellular 'memory' of high glucose stress signalling. Diabetologia 2007, 50, (7), 1523-31. [CrossRef]

- Brownlee, M., The pathobiology of diabetic complications: a unifying mechanism. Diabetes 2005, 54, (6), 1615-25.

- Araki, E.; Nishikawa, T., Oxidative stress: A cause and therapeutic target of diabetic complications. J Diabetes Investig 2010, 1, (3), 90-6. [CrossRef]

- Caja, S.; Enríquez, J.A., Mitochondria in endothelial cells: Sensors and integrators of environmental cues. Redox Biol 2017, 12, 821-827. [CrossRef]

- Cannito, S.; Giardino, I.; d'Apolito, M.; Pettoello-Mantovani, M.; Scaltrito, F.; Mangieri, D.; Piscazzi, A., The Multifaceted Role of Mitochondria in Angiogenesis. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26, (16), 7960. [CrossRef]

- Zorov, D.B.; Juhaszova, M.; Sollott, S.J., Mitochondrial ROS-induced ROS release: an update and review. Biochim Biophys Acta 2006, 1757, (5-6), 509-17. [CrossRef]

- Kowluru, R.A.; Alka, K., Mitochondrial Quality Control and Metabolic Memory Phenomenon Associated with Continued Progression of Diabetic Retinopathy. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, (9), 8076. [CrossRef]

- Hombrebueno, J.R.; Cairns, L.; Dutton, L.R.; Lyons, T.J.; Brazil, D.P.; Moynagh, P.; Curtis, T.M.; Xu, H., Uncoupled turnover disrupts mitochondrial quality control in diabetic retinopathy. JCI Insight 2019, 5, 4, (23), e129760. [CrossRef]

- Kowluru, R.A.; Mohammad, G.; Kumar, J., Impaired Removal of the Damaged Mitochondria in the Metabolic Memory Phenomenon Associated with Continued Progression of Diabetic Retinopathy. Mol Neurobiol 2024, 61, (1), 188-199. [CrossRef]

- Ho, P.T.B.; Clark, I.M.; Le, L.T.T., MicroRNA-Based Diagnosis and Therapy. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, (13), 7167.

- Wenceslau, C.F.; McCarthy, C.G.; Szasz, T.; Spitler, K.; Goulopoulou, S.; Webb, R.C., Working Group on DAMPs in Cardiovascular Disease. Mitochondrial damage-associated molecular patterns and vascular function. Eur Heart J 2014, 35, 1172–1177. [CrossRef]

- Giardino, I.; d'Apolito, M.; Brownlee, M.; Maffione, A.B.; Colia, A.L.; Sacco, M.; Ferrara, P.; Pettoello-Mantovani, M., Vascular toxicity of urea, a new "old player" in the pathogenesis of chronic renal failure induced cardiovascular diseases. Turk Pediatri Ars 2017, 52, (4), 187-193. [CrossRef]

- Vercellino, I.; Sazanov, L.A., The assembly, regulation and function of the mitochondrial respiratory chain. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2022, 23, (2), 141-161. [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Lu, H.; Chen, Y.; Yang, D.; Sun, L.; He, L., The Loss of Mitochondrial Quality Control in Diabetic Kidney Disease. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9, 706832. [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Sun, Y.; Nie, L.; Cui, A.; Zhao, P.; Leung, W.K.; Wang, Q., Metabolic memory: mechanisms and diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2024, 9, (1), 38. [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Qi, F.; Guo, F.; Shao, M.; Song, Y.; Ren, G.; Linlin, Z.; Qin, G.; Zhao, Y., An update on chronic complications of diabetes mellitus: from molecular mechanisms to therapeutic strategies with a focus on metabolic memory. Mol Med 2024, 30, (1), 71. [CrossRef]

- Schisano, B.; Tripathi, G.; McGee, K.; McTernan, P.G.; Ceriello, A., Glucose oscillations, more than constant high glucose, induce p53 activation and a metabolic memory in human endothelial cells. Diabetologia 2011, 54, (5), 1219-26. [CrossRef]

- Tonna, S.; El-Osta, A.; Cooper, M.E.; Tikellis, C., Metabolic memory and diabetic nephropathy: potential role for epigenetic mechanisms. Nat Rev Nephrol 2010, 6, (6), 332-41. [CrossRef]

- Kushwaha, K.; Garg, S. S.; Gupta, J., Targeting epigenetic regulators for treating diabetic nephropathy. Biochimie 2022, 202, 146-158. [CrossRef]

- Siebel, A. L.; Fernandez, A. Z.; El-Osta, A., Glycemic memory associated epigenetic changes. Biochem Pharmacol 2010, 80, (12), 1853-9. [CrossRef]

- Reddy, M. A.; Zhang, E.; Natarajan, R., Epigenetic mechanisms in diabetic complications and metabolic memory. Diabetologia 2015, 58, (3), 443-55. [CrossRef]

- Tanemoto, F.; Nangaku, M.; Mimura, I., Epigenetic memory contributing to the pathogenesis of AKI-to-CKD transition. Front Mol Biosci 2022, 9, 1003227. [CrossRef]

- Esteller, M., Epigenetics in cancer. N Engl J Med 2008, 358, (11), 1148-59. [CrossRef]

- Li, E.; Bestor, T. H.; Jaenisch, R., Targeted mutation of the DNA methyltransferase gene results in embryonic lethality. Cell 1992, 69, (6), 915-26. [CrossRef]

- Egger, G.; Liang, G.; Aparicio, A.; Jones, P. A., Epigenetics in human disease and prospects for epigenetic therapy. Nature 2004, 429, (6990), 457-63. [CrossRef]

- Robertson, K. D., DNA methylation and chromatin - unraveling the tangled web. Oncogene 2002, 21, (35), 5361-79. [CrossRef]

- Okano, M.; Bell, D. W.; Haber, D. A.; Li, E., DNA methyltransferases Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b are essential for de novo methylation and mammalian development. Cell 1999, 99, (3), 247-57. [CrossRef]

- Dabrowski, M. J.; Wojtas, B., Global DNA Methylation Patterns in Human Gliomas and Their Interplay with Other Epigenetic Modifications. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20, (14), 3478. [CrossRef]

- Toth, D. M.; Szeri, F.; Ashaber, M.; Muazu, M.; Szekvolgyi, L.; Aranyi, T., Tissue-specific roles of de novo DNA methyltransferases. Epigenetics Chromatin 2025, 18, (1), 5. [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Yu, S. J.; Hong, Q.; Yang, Y.; Shao, Z. M., Reduced Expression of TET1, TET2, TET3 and TDG mRNAs Are Associated with Poor Prognosis of Patients with Early Breast Cancer. PLoS One 2015, 10, (7), e0133896. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, X., TET (Ten-eleven translocation) family proteins: structure, biological functions and applications. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2023, 8, (1), 297. [CrossRef]

- Sufiyan, S.; Salam, H.; Ilyas, S.; Amin, W.; Arshad, F.; Fatima, K.; Naeem, S.; Laghari, A. A.; Enam, S. A.; Mughal, N., Prognostic implications of DNA methylation machinery (DNMTs and TETs) expression in gliomas: correlations with tumor grading and patient survival. J Neurooncol 2025, 173, (3), 667-682. [CrossRef]

- Kouzarides, T., Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell 2007, 128, (4), 693-705.

- Hermann, J.; Schurgers, L.; Jankowski, V., Identification and characterization of post-translational modifications: Clinical implications. Mol Aspects Med 2022, 86, 101066. [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Min, Y.; Wei, L.; Guan, C.; Yu, H.; Zhang, Z., Lysine crotonylation in disease: mechanisms, biological functions and therapeutic targets. Epigenetics Chromatin 2025, 18, (1), 13. [CrossRef]

- Raju, C.; Sankaranarayanan, K., Insights on post-translational modifications in fatty liver and fibrosis progression. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2025, 1871, (3), 167659. [CrossRef]

- Shiio, Y.; Eisenman, R. N., Histone sumoylation is associated with transcriptional repression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003, 100, (23), 13225-30. [CrossRef]

- Tahiliani, M.; Mei, P.; Fang, R.; Leonor, T.; Rutenberg, M.; Shimizu, F.; Li, J.; Rao, A.; Shi, Y., The histone H3K4 demethylase SMCX links REST target genes to X-linked mental retardation. Nature 2007, 447, (7144), 601-5. [CrossRef]

- Kaniskan, H. U.; Martini, M. L.; Jin, J., Inhibitors of Protein Methyltransferases and Demethylases. Chem Rev 2018, 118, (3), 989-1068. [CrossRef]

- Bu, C.; Xie, Y.; Weng, J.; Sun, Y.; Wu, H.; Chen, Y.; Ye, Y.; Zhou, E.; Yang, Z.; Wang, J., Inhibition of JMJD3 attenuates acute liver injury by suppressing inflammation and oxidative stress in LPS/D-Gal-induced mice. Chem Biol Interact 2025, 418, 111576. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, N.; Hu, J.; Yin, L.; Pan, Z.; Li, Y.; Du, X.; Zhang, W.; Li, F., Quantitative DNA hypomethylation of ligand Jagged1 and receptor Notch1 signifies occurrence and progression of breast carcinoma. Am J Cancer Res 2015, 5, (5), 1621-34.

- Tycko, B., Epigenetic gene silencing in cancer. J Clin Invest 2000, 105, (4), 401-7.

- Urli, T.; Greenberg, M. V. C., Epigenetic relay: Polycomb-directed DNA methylation in mammalian development. PLoS Genet 2025, 21, (9), e1011854. [CrossRef]

- Wiles, E. T.; Selker, E. U., H3K27 methylation: a promiscuous repressive chromatin mark. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2017, 43, 31-37. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Hampton, J. T.; Kutateladze, T. G.; Liu, W. R., Epigenetic reader chromodomain as a potential therapeutic target. RSC Chem Biol 2025, 6, (6), 833-844.

- Angrand, P. O., Structure and Function of the Polycomb Repressive Complexes PRC1 and PRC2. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, (11). [CrossRef]

- Seto, E.; Yoshida, M., Erasers of histone acetylation: the histone deacetylase enzymes. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2014, 6, (4), a018713. [CrossRef]

- Cedar, H.; Bergman, Y., Linking DNA methylation and histone modification: patterns and paradigms. Nat Rev Genet 2009, 10, (5), 295-304. [CrossRef]

- Esteve, P. O.; Chin, H. G.; Benner, J.; Feehery, G. R.; Samaranayake, M.; Horwitz, G. A.; Jacobsen, S. E.; Pradhan, S., Regulation of DNMT1 stability through SET7-mediated lysine methylation in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009, 106, (13), 5076-81. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; Zhang, Y., The MeCP1 complex represses transcription through preferential binding, remodeling, and deacetylating methylated nucleosomes. Genes Dev 2001, 15, (7), 827-32.

- Tan, J. Z.; Yan, Y.; Wang, X. X.; Jiang, Y.; Xu, H. E., EZH2: biology, disease, and structure-based drug discovery. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2014, 35, (2), 161-74. [CrossRef]

- Wahid, F.; Shehzad, A.; Khan, T.; Kim, Y. Y., MicroRNAs: synthesis, mechanism, function, and recent clinical trials. Biochim Biophys Acta 2010, 1803, (11), 1231-43. [CrossRef]

- Macgregor-Das, A. M.; Das, S., A microRNA's journey to the center of the mitochondria. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2018, 315, (2), H206-H215. [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Yan, H.; Zhuang, S., Histone deacetylases as targets for treatment of multiple diseases. Clin Sci (Lond) 2013, 124, (11), 651-62. [CrossRef]

- Ibanez-Cabellos, J. S.; Pallardo, F. V.; Garcia-Gimenez, J. L.; Seco-Cervera, M., Oxidative Stress and Epigenetics: miRNA Involvement in Rare Autoimmune Diseases. Antioxidants (Basel) 2023, 12, (4), 800. [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, R. S.; Herman, J. G.; McCaffrey, T. A.; Raj, D. S., Beyond genetics: epigenetic code in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2013, 79, (1), 23-32. [CrossRef]

- Wing, M. R.; Ramezani, A.; Gill, H. S.; Devaney, J. M.; Raj, D. S., Epigenetics of progression of chronic kidney disease: fact or fantasy? Semin Nephrol 2014, 33, (4), 363-74. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Shen, F.; Liu, F.; Zhuang, S., Histone Modifications in Acute Kidney Injury. Kidney Dis (Basel) 2022, 8, (6), 466-477. [CrossRef]

- Villeneuve, L. M.; Reddy, M. A.; Lanting, L. L.; Wang, M.; Meng, L.; Natarajan, R., Epigenetic histone H3 lysine 9 methylation in metabolic memory and inflammatory phenotype of vascular smooth muscle cells in diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008, 105, (26), 9047-52. [CrossRef]

- De Marinis, Y.; Cai, M.; Bompada, P.; Atac, D.; Kotova, O.; Johansson, M. E.; Garcia-Vaz, E.; Gomez, M. F.; Laakso, M.; Groop, L., Epigenetic regulation of the thioredoxin-interacting protein (TXNIP) gene by hyperglycemia in kidney. Kidney Int 2016, 89, (2), 342-53. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, M.; Kowluru, R. A., The Role of DNA Methylation in the Metabolic Memory Phenomenon Associated With the Continued Progression of Diabetic Retinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2016, 57, (13), 5748-5757. [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Gou, L.; Chen, L.; Zhong, X.; Zhang, D.; Zhu, H.; Lu, X.; Zeng, T.; Deng, X.; Li, Y., NADPH oxidase 4 and endothelial nitric oxide synthase contribute to endothelial dysfunction mediated by histone methylations in metabolic memory. Free Radic Biol Med 2018, 115, 383-394. [CrossRef]

- Brasacchio, D.; Okabe, J.; Tikellis, C.; Balcerczyk, A.; George, P.; Baker, E. K.; Calkin, A. C.; Brownlee, M.; Cooper, M. E.; El-Osta, A., Hyperglycemia induces a dynamic cooperativity of histone methylase and demethylase enzymes associated with gene-activating epigenetic marks that coexist on the lysine tail. Diabetes 2009, 58, (5), 1229-36. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.; Wu, X.; Chen, X.; Xu, H.; Zhang, T.; Xu, Y., Hypermethylated in cancer 1 (HIC1) mediates high glucose induced ROS accumulation in renal tubular epithelial cells by epigenetically repressing SIRT1 transcription. Biochim Biophys Acta Gene Regul Mech 2018, 1861, (10), 917-927. [CrossRef]

- Rossi, M. N.; Ciolfi, A.; Matteo, V.; Pedace, L.; Nardini, C.; Loricchio, E.; Caiello, I.; Bellomo, F.; Taranta, A.; De Leo, E.; Tartaglia, M.; Emma, F.; De Benedetti, F.; Miele, E.; Prencipe, G., Genome-wide DNA methylation analysis identifies kidney epigenetic dysregulation in a cystinosis mouse model. Front Cell Dev Biol 2025, 13, 1638123. [CrossRef]

- Stenvinkel, P.; Ekstrom, T. J., Does the uremic milieu affect the epigenotype? J Ren Nutr 2009, 19, (1), 82-5. [CrossRef]

- Kato, S.; Lindholm, B.; Stenvinkel, P.; Ekstrom, T. J.; Luttropp, K.; Yuzawa, Y.; Yasuda, Y.; Tsuruta, Y.; Maruyama, S., DNA hypermethylation and inflammatory markers in incident Japanese dialysis patients. Nephron Extra 2012, 2, (1), 159-68. [CrossRef]

- Wielscher, M.; Mandaviya, P. R.; Kuehnel, B.; Joehanes, R.; Mustafa, R.; Robinson, O.; Zhang, Y.; Bodinier, B.; Walton, E.; Mishra, P. P.; Schlosser, P.; Wilson, R.; Tsai, P. C.; Palaniswamy, S.; Marioni, R. E.; Fiorito, G.; Cugliari, G.; Karhunen, V.; Ghanbari, M.; Psaty, B. M.; Loh, M.; Bis, J. C.; Lehne, B.; Sotoodehnia, N.; Deary, I. J.; Chadeau-Hyam, M.; Brody, J. A.; Cardona, A.; Selvin, E.; Smith, A. K.; Miller, A. H.; Torres, M. A.; Marouli, E.; Gao, X.; van Meurs, J. B. J.; Graf-Schindler, J.; Rathmann, W.; Koenig, W.; Peters, A.; Weninger, W.; Farlik, M.; Zhang, T.; Chen, W.; Xia, Y.; Teumer, A.; Nauck, M.; Grabe, H. J.; Doerr, M.; Lehtimaki, T.; Guan, W.; Milani, L.; Tanaka, T.; Fisher, K.; Waite, L. L.; Kasela, S.; Vineis, P.; Verweij, N.; van der Harst, P.; Iacoviello, L.; Sacerdote, C.; Panico, S.; Krogh, V.; Tumino, R.; Tzala, E.; Matullo, G.; Hurme, M. A.; Raitakari, O. T.; Colicino, E.; Baccarelli, A. A.; Kahonen, M.; Herzig, K. H.; Li, S.; Conneely, K. N.; Kooner, J. S.; Kottgen, A.; Heijmans, B. T.; Deloukas, P.; Relton, C.; Ong, K. K.; Bell, J. T.; Boerwinkle, E.; Elliott, P.; Brenner, H.; Beekman, M.; Levy, D.; Waldenberger, M.; Chambers, J. C.; Dehghan, A.; Jarvelin, M. R., DNA methylation signature of chronic low-grade inflammation and its role in cardio-respiratory diseases. Nat Commun 2022, 13, (1), 2408. [CrossRef]

- Vujcic, S.; Kotur-Stevuljevic, J.; Vujcic, Z.; Stojanovic, S.; Beljic Zivkovic, T.; Vuksanovic, M.; Marjanovic Petkovic, M.; Perovic Blagojevic, I.; Koprivica-Uzelac, B.; Ilic-Mijailovic, S.; Rizzo, M.; Zeljkovic, A.; Stefanovic, T.; Bosic, S.; Vekic, J., Global DNA Methylation in Poorly Controlled Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Association with Redox and Inflammatory Biomarkers. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26, (14) 6716. [CrossRef]

- Gluck, C.; Qiu, C.; Han, S. Y.; Palmer, M.; Park, J.; Ko, Y. A.; Guan, Y.; Sheng, X.; Hanson, R. L.; Huang, J.; Chen, Y.; Park, A. S. D.; Izquierdo, M. C.; Mantzaris, I.; Verma, A.; Pullman, J.; Li, H.; Susztak, K., Kidney cytosine methylation changes improve renal function decline estimation in patients with diabetic kidney disease. Nat Commun 2019, 10, (1), 2461. [CrossRef]

- Ingrosso, D.; Perna, A. F., DNA Methylation Dysfunction in Chronic Kidney Disease. Genes (Basel) 2020, 11, (7), 811. [CrossRef]

- Mimura, I.; Chen, Z.; Natarajan, R., Epigenetic alterations and memory: key players in the development/progression of chronic kidney disease promoted by acute kidney injury and diabetes. Kidney Int 2025, 107, (3), 434-456. [CrossRef]

- Swan, E. J.; Maxwell, A. P.; McKnight, A. J., Distinct methylation patterns in genes that affect mitochondrial function are associated with kidney disease in blood-derived DNA from individuals with Type 1 diabetes. Diabet Med 2015, 32, (8), 1110-5. [CrossRef]

- Imai, S.; Guarente, L., NAD+ and sirtuins in aging and disease. Trends Cell Biol 2014, 24, (8), 464-71. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Chen, H.; Li, J.; Li, T.; Zheng, B.; Zheng, Y.; Jin, H.; He, Y.; Gu, Q.; Xu, X., Sirtuin 1-mediated cellular metabolic memory of high glucose via the LKB1/AMPK/ROS pathway and therapeutic effects of metformin. Diabetes 2012, 61, (1), 217-28. [CrossRef]

- Orimo, M.; Minamino, T.; Miyauchi, H.; Tateno, K.; Okada, S.; Moriya, J.; Komuro, I., Protective role of SIRT1 in diabetic vascular dysfunction. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2009, 29, (6), 889-94. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Kim, Y. R.; Vikram, A.; Kumar, S.; Kassan, M.; Gabani, M.; Lee, S. K.; Jacobs, J. S.; Irani, K., P66Shc-Induced MicroRNA-34a Causes Diabetic Endothelial Dysfunction by Downregulating Sirtuin1. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2017, 36, (12), 2394-2403.

- Huang, K.; Huang, J.; Xie, X.; Wang, S.; Chen, C.; Shen, X.; Liu, P.; Huang, H., Sirt1 resists advanced glycation end products-induced expressions of fibronectin and TGF-beta1 by activating the Nrf2/ARE pathway in glomerular mesangial cells. Free Radic Biol Med 2013, 65, 528-540. [CrossRef]

- Koyama, T.; Kume, S.; Koya, D.; Araki, S.; Isshiki, K.; Chin-Kanasaki, M.; Sugimoto, T.; Haneda, M.; Sugaya, T.; Kashiwagi, A.; Maegawa, H.; Uzu, T., SIRT3 attenuates palmitate-induced ROS production and inflammation in proximal tubular cells. Free Radic Biol Med 2011, 51, (6), 1258-67. [CrossRef]

- Juszczak, F.; Arnould, T.; Decleves, A. E., The Role of Mitochondrial Sirtuins (SIRT3, SIRT4 and SIRT5) in Renal Cell Metabolism: Implication for Kidney Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, (13) 6936. [CrossRef]

- Dikalova, A. E.; Itani, H. A.; Nazarewicz, R. R.; McMaster, W. G.; Flynn, C. R.; Uzhachenko, R.; Fessel, J. P.; Gamboa, J. L.; Harrison, D. G.; Dikalov, S. I., Sirt3 Impairment and SOD2 Hyperacetylation in Vascular Oxidative Stress and Hypertension. Circ Res 2017, 121, (5), 564-574.

- Dikalova, S.; Dikalova, A., Mitochondrial deacetylase Sirt3 in vascular dysfunction and hypertension. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 2024, 31, (2), 151-156.

- Pacher, P.; Szabo, C., Role of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 activation in the pathogenesis of diabetic complications: endothelial dysfunction, as a common underlying theme. Antioxid Redox Signal 2008, 7, (11-12), 1568-80. [CrossRef]

- Kanasaki, K.; Shi, S.; Kanasaki, M.; He, J.; Nagai, T.; Nakamura, Y.; Ishigaki, Y.; Kitada, M.; Srivastava, S. P.; Koya, D., Linagliptin-mediated DPP-4 inhibition ameliorates kidney fibrosis in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice by inhibiting endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition in a therapeutic regimen. Diabetes 2014, 63, (6), 2120-31. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lin, B.; Nie, L.; Li, P., microRNA-20b contributes to high glucose-induced podocyte apoptosis by targeting SIRT7. Mol Med Rep 2017, 16, (4), 5667-5674. [CrossRef]

- Jin, Q.; Ma, F.; Liu, T.; Yang, L.; Mao, H.; Wang, Y.; Peng, L.; Li, P.; Zhan, Y., Sirtuins in kidney diseases: potential mechanism and therapeutic targets. Cell Commun Signal 2024, 22, (1), 114. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, H.; Zeng, W.; Li, S.; Chen, C.; Song, X.; Sun, J.; Sun, Z.; Cui, C.; Cao, X.; Zheng, L.; Wang, P.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, M.; Chen, H., ZIPK mediates endothelial cell contraction through myosin light chain phosphorylation and is required for ischemic-reperfusion injury. Faseb J 2019, 33, (8), 9062-9074. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, J.; Lu, L.; Huang, T.; Hou, W.; Wang, F.; Yu, L.; Wu, F.; Qi, J.; Chen, X.; Meng, Z.; Zhu, M., Sirt7 associates with ELK1 to participate in hyperglycemia memory and diabetic nephropathy via modulation of DAPK3 expression and endothelial inflammation. Transl Res 2022, 247, 99-116. [CrossRef]

- Wegner, M.; Neddermann, D.; Piorunska-Stolzmann, M.; Jagodzinski, P. P., Role of epigenetic mechanisms in the development of chronic complications of diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2014, 105, (2), 164-75. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Fan, X.; Xu, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, X.; Shi, T.; Tang, J.; Guan, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, A., Role of DNA methylation transferase in urinary system diseases: From basic to clinical perspectives (Review). Int J Mol Med 2025, 55, (2) 19. [CrossRef]

- McClelland, A. D.; Kantharidis, P., microRNA in the development of diabetic complications. Clin Sci (Lond) 2014, 126, (2), 95-110. [CrossRef]

- Prattichizzo, F.; Giuliani, A.; De Nigris, V.; Pujadas, G.; Ceka, A.; La Sala, L.; Genovese, S.; Testa, R.; Procopio, A. D.; Olivieri, F.; Ceriello, A., Extracellular microRNAs and endothelial hyperglycaemic memory: a therapeutic opportunity? Diabetes Obes Metab 2016, 18, (9), 855-67. [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Wang, X.; Zhi, X.; Meng, D., Epigenetic regulation in diabetic vascular complications. J Mol Endocrinol 2019, 63, (4), R103-R115. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Liao, Y.; Chen, L.; Liu, G.; Feng, Y.; Zeng, T.; Zhang, J., The MicroRNAs in the Pathogenesis of Metabolic Memory. Endocrinology. 2015, 156, (9), 3157-68. [CrossRef]

- Bera, A.; Das, F.; Ghosh-Choudhury, N.; Mariappan, M. M.; Kasinath, B. S.; Ghosh Choudhury, G., Reciprocal regulation of miR-214 and PTEN by high glucose regulates renal glomerular mesangial and proximal tubular epithelial cell hypertrophy and matrix expansion. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2017, 313, (4), C430-C447. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, S.; Wu, D.; Liu, X.; Shi, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Ding, J.; Xiao, Y.; Guo, B., MicroRNA-22 Promotes Renal Tubulointerstitial Fibrosis by Targeting PTEN and Suppressing Autophagy in Diabetic Nephropathy. J Diabetes Res 2018, 2018, 4728645. [CrossRef]

- Ding, M.; Shi, R.; Du, Y.; Chang, P.; Gao, T.; De, D.; Chen, Y.; Li, M.; Li, J.; Li, K.; Cheng, S.; Gu, X.; Li, J.; Zhang, S.; Feng, N.; Liu, J.; Jia, M.; Fan, R.; Pei, J.; Gao, C.; Fu, F., O-GlcNAcylation-mediated endothelial metabolic memory contributes to cardiac damage via small extracellular vesicles. Cell Metab 2025, 37, (6), 1344-1363 e6. [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Song, Q.; Hu, C.; Da, X.; Yu, Y.; He, Z.; Xu, C.; Chen, Q.; Wang, Q. K., Endothelial cell metabolic memory causes cardiovascular dysfunction in diabetes. Cardiovasc Res 2022, 118, (1), 196-211. [CrossRef]

- Pedruzzi, L. M.; Cardozo, L. F.; Daleprane, J. B.; Stockler-Pinto, M. B.; Monteiro, E. B.; Leite, M., Jr.; Vaziri, N. D.; Mafra, D., Systemic inflammation and oxidative stress in hemodialysis patients are associated with down-regulation of Nrf2. J Nephrol 2015, 28, (4), 495-501. [CrossRef]

- Bondi, C. D.; Hartman, H. L.; Tan, R. J., NRF2 in kidney physiology and disease. Physiol Rep 2024, 12, (5), e15961. [CrossRef]

- Intine, R. V.; Sarras, M. P., Jr., Metabolic memory and chronic diabetes complications: potential role for epigenetic mechanisms. Curr Diab Rep 2013, 12, (5), 551-9. [CrossRef]

- Yang, A. Y.; Kim, H.; Li, W.; Kong, A. N., Natural compound-derived epigenetic regulators targeting epigenetic readers, writers and erasers. Curr Top Med Chem 2017, 16, (7), 697-713. [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S.; Rao, C. M., Epigenetic tools (The Writers, The Readers and The Erasers) and their implications in cancer therapy. Eur J Pharmacol 2018, 837, 8-24. [CrossRef]

- Contieri, B.; Duarte, B. K. L.; Lazarini, M., Updates on DNA methylation modifiers in acute myeloid leukemia. Ann Hematol 2020, 99, (4), 693-701. [CrossRef]

- Pinto, V.; Bergantim, R.; Caires, H. R.; Seca, H.; Guimaraes, J. E.; Vasconcelos, M. H., Multiple Myeloma: Available Therapies and Causes of Drug Resistance. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12, (2), 407. [CrossRef]

- Damiani, E.; Duran, M. N.; Mohan, N.; Rajendran, P.; Dashwood, R. H., Targeting Epigenetic 'Readers' with Natural Compounds for Cancer Interception. J Cancer Prev 2020, 25, (4), 189-203. [CrossRef]

- Arce, C.; Perez-Plasencia, C.; Gonzalez-Fierro, A.; de la Cruz-Hernandez, E.; Revilla-Vazquez, A.; Chavez-Blanco, A.; Trejo-Becerril, C.; Perez-Cardenas, E.; Taja-Chayeb, L.; Bargallo, E.; Villarreal, P.; Ramirez, T.; Vela, T.; Candelaria, M.; Camargo, M. F.; Robles, E.; Duenas-Gonzalez, A., A proof-of-principle study of epigenetic therapy added to neoadjuvant doxorubicin cyclophosphamide for locally advanced breast cancer. PLoS One 2006, 1, (1), e98. [CrossRef]

- Candelaria, M.; Gallardo-Rincon, D.; Arce, C.; Cetina, L.; Aguilar-Ponce, J. L.; Arrieta, O.; Gonzalez-Fierro, A.; Chavez-Blanco, A.; de la Cruz-Hernandez, E.; Camargo, M. F.; Trejo-Becerril, C.; Perez-Cardenas, E.; Perez-Plasencia, C.; Taja-Chayeb, L.; Wegman-Ostrosky, T.; Revilla-Vazquez, A.; Duenas-Gonzalez, A., A phase II study of epigenetic therapy with hydralazine and magnesium valproate to overcome chemotherapy resistance in refractory solid tumors. Ann Oncol 2007, 18, (9), 1529-38.

- Coronel, J.; Cetina, L.; Pacheco, I.; Trejo-Becerril, C.; Gonzalez-Fierro, A.; de la Cruz-Hernandez, E.; Perez-Cardenas, E.; Taja-Chayeb, L.; Arias-Bofill, D.; Candelaria, M.; Vidal, S.; Duenas-Gonzalez, A., A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized phase III trial of chemotherapy plus epigenetic therapy with hydralazine valproate for advanced cervical cancer. Preliminary results. Med Oncol 2011, 28 Suppl 1, S540-6. [CrossRef]

- Candelaria, M.; Herrera, A.; Labardini, J.; Gonzalez-Fierro, A.; Trejo-Becerril, C.; Taja-Chayeb, L.; Perez-Cardenas, E.; de la Cruz-Hernandez, E.; Arias-Bofill, D.; Vidal, S.; Cervera, E.; Duenas-Gonzalez, A., Hydralazine and magnesium valproate as epigenetic treatment for myelodysplastic syndrome. Preliminary results of a phase-II trial. Ann Hematol 2011, 90, (4), 379-87. [CrossRef]

- Heerboth, S.; Lapinska, K.; Snyder, N.; Leary, M.; Rollinson, S.; Sarkar, S., Use of epigenetic drugs in disease: an overview. Genet Epigenet 2014, 6, 9-19. [CrossRef]

- Farsetti, A.; Illi, B.; Gaetano, C., How epigenetics impacts on human diseases. Eur J Intern Med 2023, 114, 15-22. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Han, Z.; Ji, X.; Luo, Y., Epigenetic Regulation of Oxidative Stress in Ischemic Stroke. Aging Dis 2016, 7, (3), 295-306. [CrossRef]

- Guzik, T. J.; Touyz, R. M., Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Vascular Aging in Hypertension. Hypertension 2017, 70, (4), 660-667. [CrossRef]

- Marchant, V.; Trionfetti, F.; Tejedor-Santamaria, L.; Rayego-Mateos, S.; Rotili, D.; Bontempi, G.; Domenici, A.; Mene, P.; Mai, A.; Martin-Cleary, C.; Ortiz, A.; Ramos, A. M.; Strippoli, R.; Ruiz-Ortega, M., BET Protein Inhibitor JQ1 Ameliorates Experimental Peritoneal Damage by Inhibition of Inflammation and Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants (Basel) 2023, 12, (12), 2055. [CrossRef]

- Fraile-Martinez, O.; De Leon-Oliva, D.; Boaru, D. L.; De Castro-Martinez, P.; Garcia-Montero, C.; Barrena-Blazquez, S.; Garcia-Garcia, J.; Garcia-Honduvilla, N.; Alvarez-Mon, M.; Lopez-Gonzalez, L.; Diaz-Pedrero, R.; Guijarro, L. G.; Ortega, M. A., Connecting epigenetics and inflammation in vascular senescence: state of the art, biomarkers and senotherapeutics. Front Genet 2024, 15, 1345459. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Malek, V.; Natarajan, R., Update: the role of epigenetics in the metabolic memory of diabetic complications. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2024, 327, (3), F327-F339. [CrossRef]

- Miao, F.; Chen, Z.; Genuth, S.; Paterson, A.; Zhang, L.; Wu, X.; Li, S. M.; Cleary, P.; Riggs, A.; Harlan, D. M.; Lorenzi, G.; Kolterman, O.; Sun, W.; Lachin, J. M.; Natarajan, R., Evaluating the role of epigenetic histone modifications in the metabolic memory of type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 2014, 63, (5), 1748-62. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Miao, F.; Paterson, A. D.; Lachin, J. M.; Zhang, L.; Schones, D. E.; Wu, X.; Wang, J.; Tompkins, J. D.; Genuth, S.; Braffett, B. H.; Riggs, A. D.; Natarajan, R., Epigenomic profiling reveals an association between persistence of DNA methylation and metabolic memory in the DCCT/EDIC type 1 diabetes cohort. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016, 113, (21), E3002-11. [CrossRef]

- Soriano-Tarraga, C.; Jimenez-Conde, J.; Giralt-Steinhauer, E.; Mola-Caminal, M.; Vivanco-Hidalgo, R. M.; Ois, A.; Rodriguez-Campello, A.; Cuadrado-Godia, E.; Sayols-Baixeras, S.; Elosua, R.; Roquer, J., Epigenome-wide association study identifies TXNIP gene associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus and sustained hyperglycemia. Hum Mol Genet 2016, 25, (3), 609-19. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M. E.; El-Osta, A.; Allen, T. J.; Watson, A. M. D.; Thomas, M. C.; Jandeleit-Dahm, K. A. M., Metabolic Karma-The Atherogenic Legacy of Diabetes: The 2017 Edwin Bierman Award Lecture. Diabetes 2018, 67, (5), 785-790. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Natarajan, R., Epigenetic modifications in metabolic memory: What are the memories, and can we erase them? Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2022, 323, (2), C570-C582. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, S.; Yuan, Q.; Zhu, L.; Li, F.; Wang, H.; Kong, D.; Hao, J., TXNIP, a novel key factor to cause Schwann cell dysfunction in diabetic peripheral neuropathy, under the regulation of PI3K/Akt pathway inhibition-induced DNMT1 and DNMT3a overexpression. Cell Death Dis 2021, 12, (7), 642. [CrossRef]

- Singh LP. Thioredoxin Interacting Protein (TXNIP) and Pathogenesis of Diabetic Retinopathy. J Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2013, 4, (10), 4172.

- Garcia-Calzon, S.; Maguolo, A.; Eichelmann, F.; Edsfeldt, A.; Perfilyev, A.; Maziarz, M.; Lindstrom, A.; Sun, J.; Briviba, M.; Schulze, M. B.; Klovins, J.; Ahlqvist, E.; Goncalves, I.; Ling, C., Epigenetic biomarkers predict macrovascular events in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Cell Rep Med 2025, 6, (8), 102290. [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Guan, Y.; Sheng, X.; Gluck, C.; Seasock, M. J.; Hakimi, A. A.; Qiu, C.; Pullman, J.; Verma, A.; Li, H.; Palmer, M.; Susztak, K., Functional methylome analysis of human diabetic kidney disease. JCI Insight 2019, 4, (11), e128886. [CrossRef]

- Kuo, F. C.; Chao, C. T.; Lin, S. H., The Dynamics and Plasticity of Epigenetics in Diabetic Kidney Disease: Therapeutic Applications Vis-a-Vis. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, (2), 843. [CrossRef]

- Smyth, L. J.; Patterson, C. C.; Swan, E. J.; Maxwell, A. P.; McKnight, A. J., DNA Methylation Associated With Diabetic Kidney Disease in Blood-Derived DNA. Front Cell Dev Biol 2020, 8, 561907. [CrossRef]

- Smyth, L. J.; Dahlstrom, E. H.; Syreeni, A.; Kerr, K.; Kilner, J.; Doyle, R.; Brennan, E.; Nair, V.; Fermin, D.; Nelson, R. G.; Looker, H. C.; Wooster, C.; Andrews, D.; Anderson, K.; McKay, G. J.; Cole, J. B.; Salem, R. M.; Conlon, P. J.; Kretzler, M.; Hirschhorn, J. N.; Sadlier, D.; Godson, C.; Florez, J. C.; Forsblom, C.; Maxwell, A. P.; Groop, P. H.; Sandholm, N.; McKnight, A. J., Epigenome-wide meta-analysis identifies DNA methylation biomarkers associated with diabetic kidney disease. Nat Commun 2022, 13, (1), 7891. [CrossRef]

- Marchiori, M.; Maguolo, A.; Perfilyev, A.; Maziarz, M.; Martinell, M.; Gomez, M. F.; Ahlqvist, E.; Garcia-Calzon, S.; Ling, C., Blood-Based Epigenetic Biomarkers Associated With Incident Chronic Kidney Disease in Individuals With Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes 2025, 74, (3), 439-450. [CrossRef]

- Akhouri, V.; Majumder, S.; Gaikwad, A. B., Targeting DNA methylation in diabetic kidney disease: A new perspective. Life Sci 2023, 335, 122256. [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Chen, H.; Ren, S.; Xia, M.; Zhu, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Tang, L.; Sun, L.; Liu, H.; Dong, Z., Aberrant DNA methylation of mTOR pathway genes promotes inflammatory activation of immune cells in diabetic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2019, 96, (2), 409-420. [CrossRef]

- Al-Dabet, M. M.; Shahzad, K.; Elwakiel, A.; Sulaj, A.; Kopf, S.; Bock, F.; Gadi, I.; Zimmermann, S.; Rana, R.; Krishnan, S.; Gupta, D.; Manoharan, J.; Fatima, S.; Nazir, S.; Schwab, C.; Baber, R.; Scholz, M.; Geffers, R.; Mertens, P. R.; Nawroth, P. P.; Griffin, J. H.; Keller, M.; Dockendorff, C.; Kohli, S.; Isermann, B., Reversal of the renal hyperglycemic memory in diabetic kidney disease by targeting sustained tubular p21 expression. Nat Commun 2020, 13, (1), 5062. [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Qi, F.; Guo, F.; Shao, M.; Song, Y.; Ren, G.; Linlin, Z.; Qin, G.; Zhao, Y., An update on chronic complications of diabetes mellitus: from molecular mechanisms to therapeutic strategies with a focus on metabolic memory. Mol Med 2024, 30, (1), 71. [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Peden, E. K.; Guo, Q.; Lee, T. H.; Li, Q.; Yuan, Y.; Chen, C.; Huang, F.; Cheng, J., Downregulation of the endothelial histone demethylase JMJD3 is associated with neointimal hyperplasia of arteriovenous fistulas in kidney failure. J Biol Chem 2022, 298, (5), 101816. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Ceinos, J.; Hussain, S.; Khan, A. W.; Zhang, L.; Almahmeed, W.; Pernow, J.; Cosentino, F., Repressive H3K27me3 drives hyperglycemia-induced oxidative and inflammatory transcriptional programs in human endothelium. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2024, 23, (1), 122. [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Yu, C.; Zhuang, S., Histone Methyltransferase EZH2: A Potential Therapeutic Target for Kidney Diseases. Front Physiol 2021, 12, 640700. [CrossRef]

- Siddiqi, F. S.; Majumder, S.; Thai, K.; Abdalla, M.; Hu, P.; Advani, S. L.; White, K. E.; Bowskill, B. B.; Guarna, G.; Dos Santos, C. C.; Connelly, K. A.; Advani, A., The Histone Methyltransferase Enzyme Enhancer of Zeste Homolog 2 Protects against Podocyte Oxidative Stress and Renal Injury in Diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol 2015, 27, (7), 2021-34. [CrossRef]

- Sekine, S.; Youle, R. J., PINK1 import regulation; a fine system to convey mitochondrial stress to the cytosol. BMC Biol 2018, 16, (1), 2. [CrossRef]

- Mu, J.; Zhang, D.; Tian, Y.; Xie, Z.; Zou, M. H., BRD4 inhibition by JQ1 prevents high-fat diet-induced diabetic cardiomyopathy by activating PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy in vivo. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2021, 149, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Ray, K. K.; Nicholls, S. J.; Buhr, K. A.; Ginsberg, H. N.; Johansson, J. O.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Kulikowski, E.; Toth, P. P.; Wong, N.; Sweeney, M.; Schwartz, G. G., Effect of Apabetalone Added to Standard Therapy on Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events in Patients With Recent Acute Coronary Syndrome and Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Jama 2020, 323, (16), 1565-1573.

- Brandts, J.; Ray, K. K., Apabetalone - BET protein inhibition in cardiovascular disease and Type 2 diabetes. Future Cardiol 2020, 16, (5), 385-395. [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, K.; Masaki, T., Epigenetic histone modifications in kidney disease and epigenetic memory. Clin Exp Nephrol 2025, 29, (9), 1129-1138. [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Qiao, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhan, P.; Yi, F., Histone Deacetylases Take Center Stage on Regulation of Podocyte Function. Kidney Dis (Basel) 2020, 6, (4), 236-246. [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Jena, G.; Tikoo, K.; Kumar, V., Valproate attenuates the proteinuria, podocyte and renal injury by facilitating autophagy and inactivation of NF-kappaB/iNOS signaling in diabetic rat. Biochimie 2015, 110, 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Yoshikawa, M.; Hishikawa, K.; Marumo, T.; Fujita, T., Inhibition of histone deacetylase activity suppresses epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition induced by TGF-beta1 in human renal epithelial cells. J Am Soc Nephrol 2007, 18, (1), 58-65. [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Gao, X.; Wei, W., The crosstalk between Sirt1 and Keap1/Nrf2/ARE anti-oxidative pathway forms a positive feedback loop to inhibit FN and TGF-beta1 expressions in rat glomerular mesangial cells. Exp Cell Res 2017, 361, (1), 63-72. [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Arroyo, O.; Flores-Chova, A.; Mendez-Debaets, M.; Garcia-Ferran, L.; Escriva, L.; Forner, M. J.; Redon, J.; Cortes, R.; Ortega, A., Inhibiting miR-200a-3p Increases Sirtuin 1 and Mitigates Kidney Injury in a Tubular Cell Model of Diabetes and Hypertension-Related Renal Damage. Biomolecules 2025, 15, (7), 995. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H. Y.; Zhong, X.; Huang, X. R.; Meng, X. M.; You, Y.; Chung, A. C.; Lan, H. Y., MicroRNA-29b inhibits diabetic nephropathy in db/db mice. Mol Ther 2014, 22, (4), 842-53. [CrossRef]

- Gondaliya, P.; Dasare, A.; Srivastava, A.; Kalia, K., Correction: miR29b regulates aberrant methylation in In-Vitro diabetic nephropathy model of renal proximal tubular cells. PLoS One 2019, 14, (1), e0211591.

- Putta, S.; Lanting, L.; Sun, G.; Lawson, G.; Kato, M.; Natarajan, R., Inhibiting microRNA-192 ameliorates renal fibrosis in diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 2012, 23, (3), 458-69. [CrossRef]

- Dhas, Y.; Arshad, N.; Biswas, N.; Jones, L. D.; Ashili, S., MicroRNA-21 Silencing in Diabetic Nephropathy: Insights on Therapeutic Strategies. Biomedicines 2023, 11, (9), 2583. [CrossRef]

- de Gonzalo-Calvo, D.; van der Meer, R. W.; Rijzewijk, L. J.; Smit, J. W.; Revuelta-Lopez, E.; Nasarre, L.; Escola-Gil, J. C.; Lamb, H. J.; Llorente-Cortes, V., Serum microRNA-1 and microRNA-133a levels reflect myocardial steatosis in uncomplicated type 2 diabetes. Sci Rep 2017, 7, (1), 47. [CrossRef]

- Napoli, C.; Benincasa, G.; Schiano, C.; Salvatore, M., Differential epigenetic factors in the prediction of cardiovascular risk in diabetic patients. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother 2020, 6, (4), 239-247. [CrossRef]

- Al-Kafaji, G.; Al-Muhtaresh, H. A., Expression of microRNA377 and microRNA192 and their potential as blood-based biomarkers for early detection of type 2 diabetic nephropathy. Mol Med Rep 2018, 18, (1), 1171-1180. [CrossRef]

- De, A.; Sarkar, A.; Banerjee, T.; Bhowmik, R.; Sar, S.; Shaharyar, M. A.; Karmakar, S.; Ghosh, N., MicroRNA: unveiling novel mechanistic and theranostic pathways in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Front Pharmacol 2025, 16, 1613844. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Su, Q.; Lu, Y.; Zhao, M.; Niu, B., Application of machine learning approaches for protein-protein interactions prediction. Med Chem 2017, 13, (6), 506–514. [CrossRef]

| Class | Enzymes | Common Name / Characteristics | Mechanism |

| I | HDAC1, HDAC2, HDAC3, HDAC8 | "Classical" HDACs | Traditional deacetylation mechanism |

| II | HDAC4, HDAC5, HDAC6, HDAC7, HDAC9, HDAC10 | “Classical" HDACs | Traditional deacetylation mechanism |

| III | SIRT 1-7 | Sirtuins | NAD+-dependent mechanism |

| IV | HDAC11 | "Classical" HDACs | Shares only weak homology with Class I and II |

| Drug name | Target | Indication | Year |

| Azacitidine (Vidaza®) | DNMTi | Myelodysplastic syndromes, Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia, Acute myeloid leukemia |

2004 2004 2007 |

| Decitabine (Dacogen®) Decitabine-Cedazuridine (Inqovi®) |

DNMTi | Myelodysplastic syndromes, Intermediate/high-risk myelodysplastic syndromes |

2006 2020 |

| Valproic Acid (Depakin®) | Class I/II HDAC | Epilepsy, bipolar disorder, migraine | 2010 |

| Vorinostat (Zolinza®) | Class I/II HDAC | Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma | 2006 |

| Romidepsin (Istodax®) | HDAC6 | Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, Peripheral T-cell lymphoma (withdrawn 2021) |

2009 2011 |

| Belinostat (Beleodaq®) | Non-selective HDACi | Relapsed or refractory peripheral T-cell lymphoma | 2014 |

| Panobinostat (Farydak®) | Non-selective HDACi | Relapsed multiple myeloma (discontinued 2021) | 2015 |

| Tazemetostat (Tazverik®) | EZH2i | Metastatic or locally advanced epithelioid sarcoma, Relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma |

2020 2020 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).