Submitted:

23 October 2025

Posted:

24 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

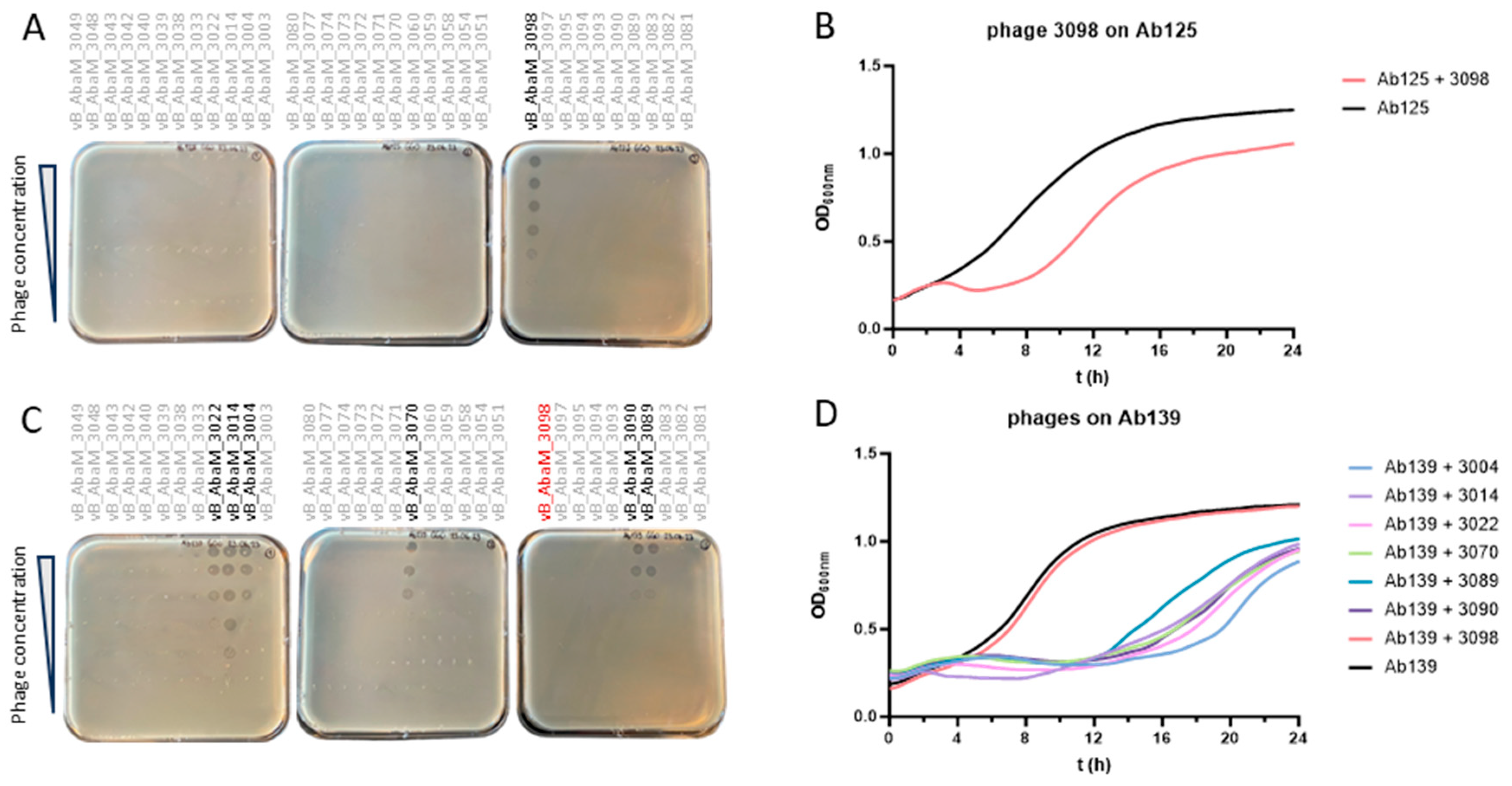

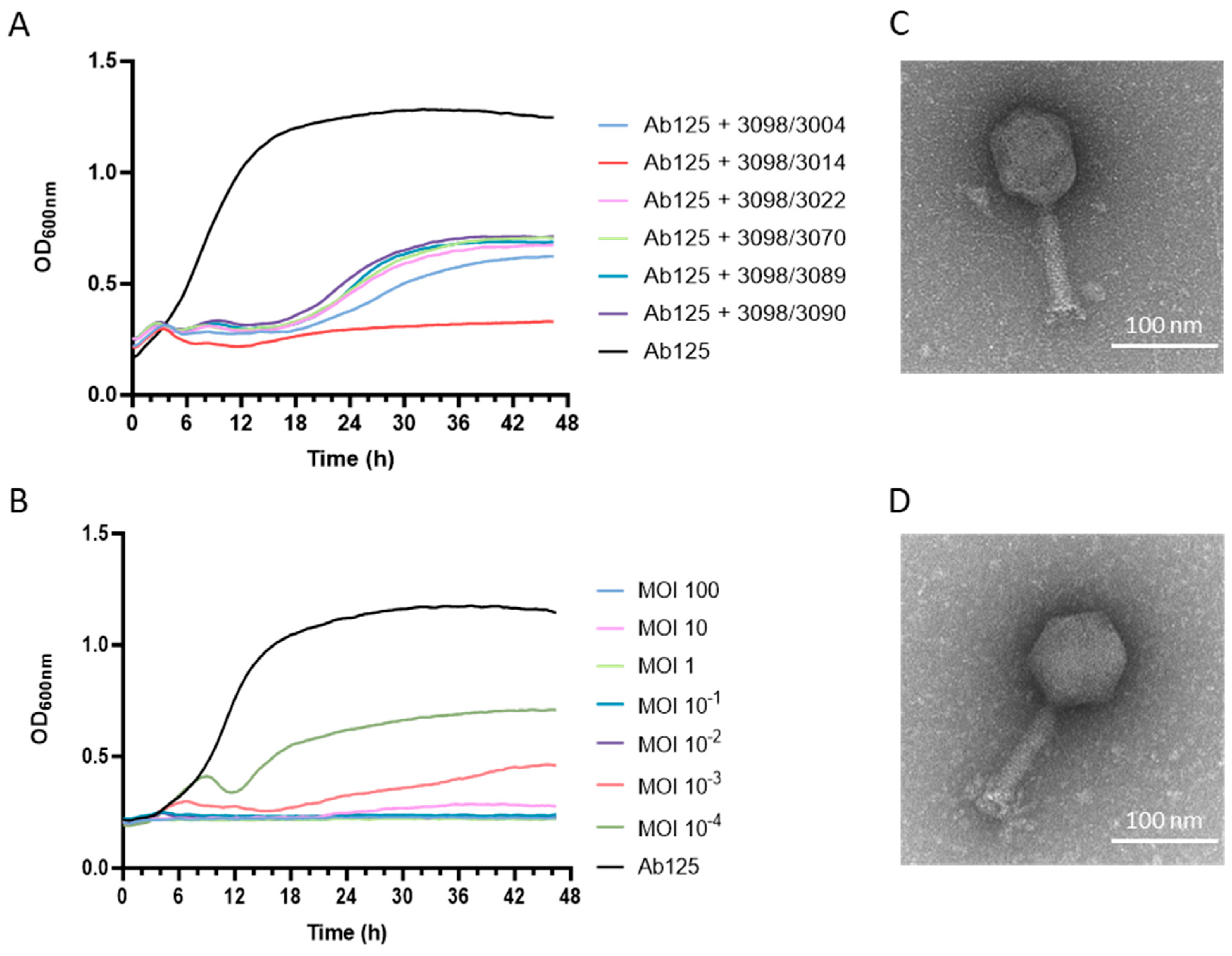

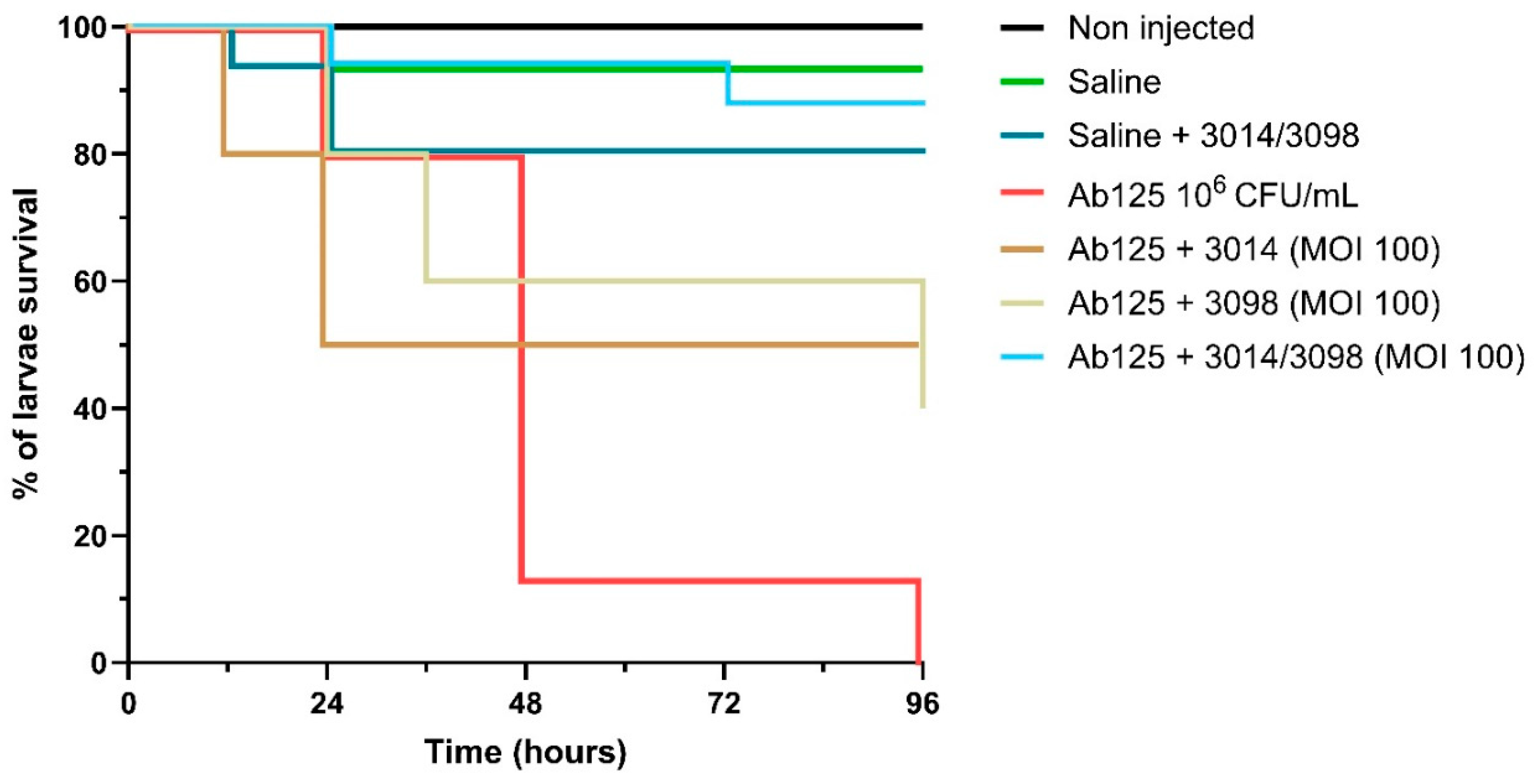

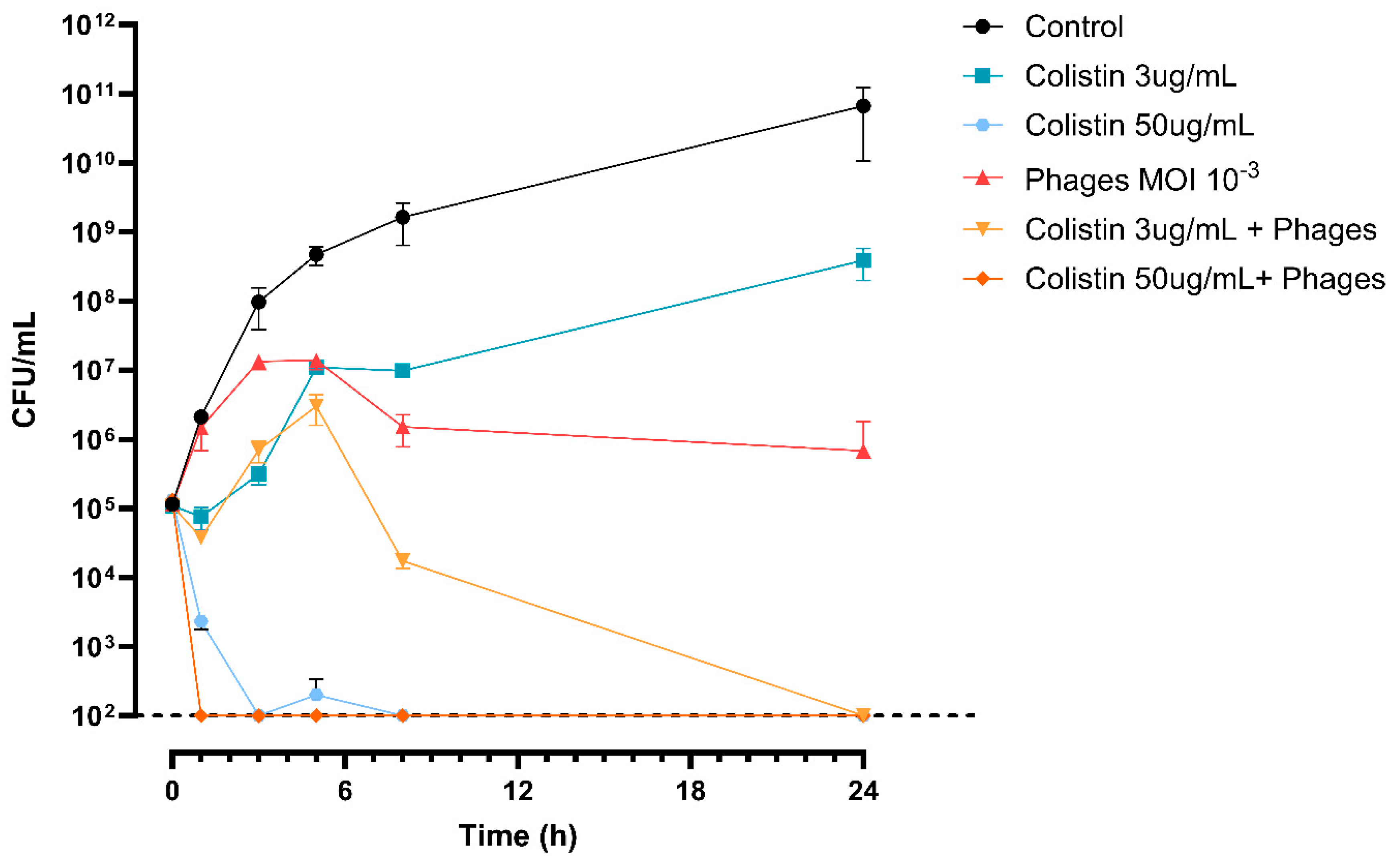

Acinetobacter baumannii is a critical public health threat, particularly with the rise in multidrug-resistant (MDR) and extensively drug-resistant (XDR) strains that limit treatment options. Phage therapy, which uses bacteriophages to target bacteria, offers a promising alternative. We isolated an XDR strain (Ab125) from a burn wound infection and screened 34 phages, identifying vB_AbaM_3098 as the only effective candidate. However, resistance rapidly emerged, producing a derivative strain (Ab139). Interestingly, Ab139, though resistant to vB_AbaM_3098, became susceptible to six previously inactive phages. While various potential determinants were identified through comparative genomics and proteomics, the mechanism causing phage resistance to vB_AbaM_3098 and simultaneous susceptibility to other phages remains to be elucidated. Among the six new candidates, vB_AbaM_3014 was the most promising. While each phage alone allowed bacterial regrowth, combining vB_AbaM_3098 and vB_AbaM_3014 completely suppressed Ab125 growth. In a Galleria mellonella infection model, this cocktail achieved 90% survival after five days compared to 0% in untreated controls. Notably, the cocktail combined one phage with modest activity and another inactive phage against the parental strain; together, they produced strong bactericidal effects. These findings highlight both the complexity of phage cocktail design and their promise as adjunct therapies against drug-resistant A. baumannii.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains, Bacteriophages, and Antibiotics

2.2. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)

2.3. Phage Amplification and Titration of Phage Suspensions

2.4. Genome Extraction, Sequencing, and Annotation

2.5. Electron Microscopy

2.6. Turbidity Assay and Virulence Index Determination

2.7. Synogram

2.8. Time–Kill Assay

2.9. Proteomic Analyses

2.10. Bacterial Virulence Testing in Galleria Mellonella

2.11. Antibacterial Activity of Phages in the Galleria Mellonella Model of Infectious Diseases

3. Results

3.1. Ab125 Challenge with Phage 3098 Restored Susceptibility to Different Phages

3.2. Comparative Genomics Between Ab125 and Ab139 Identified Genomic Variants

3.3. Proteome Profiling Does Not Correlate with the Identified Genomic Variants

3.4. Ab139 Showed No Impaired Virulence In Vivo

3.5. A Phage Cocktail Composed of Phage 3098 and a “Non-Active” Phage Fully Inhibited the Growth of the Parental Strain Ab125

3.6. Both Phages 3014 and 3098 Were Suited for Phage Therapy

3.7. The High Potency of the 3014/3098 Combination Was Confirmed In Vivo

3.8. The 3014/3098 Phage Cocktail Showed Additivity with Colistin In Vitro

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data availability statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of interest

References

- Ibrahim, S.; Al-Saryi, N.; Al-Kadmy, I.M.S.; Aziz, S.N. Multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii as an emerging concern in hospitals. Mol Biol Rep 2021, 48, 6987–6998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, L.C.; Visca, P.; Towner, K.J. Acinetobacter baumannii: evolution of a global pathogen. Pathog Dis 2014, 71, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacconelli, E.; Carrara, E.; Savoldi, A.; Harbarth, S.; Mendelson, M.; Monnet, D.L.; Pulcini, C.; Kahlmeter, G.; Kluytmans, J.; Carmeli, Y.; et al. Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: the WHO priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. Lancet Infect Dis 2018, 18, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Antimicrobial Resistance and Use Surveillance System (GLASS) Report 2022; 2022.

- Weiner-Lastinger, L.M.; Abner, S.; Edwards, J.R.; Kallen, A.J.; Karlsson, M.; Magill, S.S.; Pollock, D.; See, I.; Soe, M.M.; Walters, M.S.; et al. Antimicrobial-resistant pathogens associated with adult healthcare-associated infections: Summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network, 2015-2017. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2020, 41, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suttle, C.A. Viruses: unlocking the greatest biodiversity on Earth. Genome 2013, 56, 542–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, M.; Birkett, P.J.; Birch, E.; Griffiths, R.I.; Buckling, A. Local Adaptation of Bacteriophages to Their Bacterial Hosts in Soil. Science 2009, 325, 833–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dion, M.B.; Oechslin, F.; Moineau, S. Phage diversity, genomics and phylogeny. Nat Rev Microbiol 2020, 18, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, R. Phage lysis: do we have the hole story yet? Curr Opin Microbiol 2013, 16, 790–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Principi, N.; Silvestri, E.; Esposito, S. Advantages and Limitations of Bacteriophages for the Treatment of Bacterial Infections. Front Pharmacol 2019, 10, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulakvelidze, A.; Alavidze, Z.; Morris, J.G., Jr. Bacteriophage therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2001, 45, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirnay, J.P.; Djebara, S.; Steurs, G.; Griselain, J.; Cochez, C.; De Soir, S.; Glonti, T.; Spiessens, A.; Vanden Berghe, E.; Green, S.; et al. Personalized bacteriophage therapy outcomes for 100 consecutive cases: a multicentre, multinational, retrospective observational study. Nat Microbiol 2024, 9, 1434–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirnay, J.P.; Ferry, T.; Resch, G. Recent progress toward the implementation of phage therapy in Western medicine. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2022, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/search?intr=Phage%20Therapy (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Schooley, R.T.; Biswas, B.; Gill, J.J.; Hernandez-Morales, A.; Lancaster, J.; Lessor, L.; Barr, J.J.; Reed, S.L.; Rohwer, F.; Benler, S.; et al. Development and Use of Personalized Bacteriophage-Based Therapeutic Cocktails To Treat a Patient with a Disseminated Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2017, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CLSI. Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria That Grow Aerobically; Approved Standards. 10th ed.; 2015; Vol. CLSI document M07-A10.

- Andrews, S. FastQC: A quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. Babraham Bioinformatics 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankevich, A.; Nurk, S.; Antipov, D.; Gurevich, A.A.; Dvorkin, M.; Kulikov, A.S.; Lesin, V.M.; Nikolenko, S.I.; Pham, S.; Prjibelski, A.D.; et al. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol 2012, 19, 455–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikheenko, A.; Saveliev, V.; Hirsch, P.; Gurevich, A. WebQUAST: online evaluation of genome assemblies. Nucleic Acids Res 2023, 51, W601–W606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seemann, T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2068–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DePristo, M.A.; Banks, E.; Poplin, R.; Garimella, K.V.; Maguire, J.R.; Hartl, C.; Philippakis, A.A.; del Angel, G.; Rivas, M.A.; Hanna, M.; et al. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat Genet 2011, 43, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasimuddin, M.; Misra, S.; Li, H.; Aluru, S. Efficient Architecture-Aware Acceleration of BWA-MEM for Multicore Systems. Proceedings of 2019 IEEE International Parallel and Distributed Processing Symposium (IPDPS); pp. 314–324.

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wick, R.R.; Judd, L.M.; Gorrie, C.L.; Holt, K.E. Unicycler: Resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLoS Comput Biol 2017, 13, e1005595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouras, G.; Nepal, R.; Houtak, G.; Psaltis, A.J.; Wormald, P.J.; Vreugde, S. Pharokka: a fast scalable bacteriophage annotation tool. Bioinformatics 2023, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Meijenfeldt, F.A.B.; Arkhipova, K.; Cambuy, D.D.; Coutinho, F.H.; Dutilh, B.E. Robust taxonomic classification of uncharted microbial sequences and bins with CAT and BAT. Genome Biol 2019, 20, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hockenberry, A.J.; Wilke, C.O. BACPHLIP: predicting bacteriophage lifestyle from conserved protein domains. PeerJ 2021, 9, e11396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storms, Z.J.; Teel, M.R.; Mercurio, K.; Sauvageau, D. The Virulence Index: A Metric for Quantitative Analysis of Phage Virulence. PHAGE 2020, 1, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolic, I.; Vukovic, D.; Gavric, D.; Cvetanovic, J.; Aleksic Sabo, V.; Gostimirovic, S.; Narancic, J.; Knezevic, P. An Optimized Checkerboard Method for Phage-Antibiotic Synergy Detection. Viruses 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Committee for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing of the European Society of Clinical, M. ; Infectious, D. EUCAST Definitive Document E.Def 1.2, May 2000: Terminology relating to methods for the determination of susceptibility of bacteria to antimicrobial agents. Clin Microbiol Infect 2000, 6, 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, C.S.; Moggridge, S.; Muller, T.; Sorensen, P.H.; Morin, G.B.; Krijgsveld, J. Single-pot, solid-phase-enhanced sample preparation for proteomics experiments. Nat Protoc 2019, 14, 68–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, J.; Mann, M. MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nat Biotechnol 2008, 26, 1367–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, J.; Neuhauser, N.; Michalski, A.; Scheltema, R.A.; Olsen, J.V.; Mann, M. Andromeda: a peptide search engine integrated into the MaxQuant environment. J Proteome Res 2011, 10, 1794–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iovleva, A.; Fowler, V.G., Jr.; Doi, Y. Treatment Approaches for Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Infections. Drugs 2025, 85, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Singh, S.; Trivedi, M.; Dwivedi, M. An insight into MDR Acinetobacter baumannii infection and its pathogenesis: Potential therapeutic targets and challenges. Microb Pathog 2024, 192, 106674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manley, R.; Fitch, C.; Francis, V.; Temperton, I.; Turner, D.; Fletcher, J.; Phil, M.; Michell, S.; Temperton, B. Resistance to bacteriophage incurs a cost to virulence in drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. J Med Microbiol 2024, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Raustad, N.; Denoncourt, J.; van Opijnen, T.; Geisinger, E. Genome-wide phage susceptibility analysis in Acinetobacter baumannii reveals capsule modulation strategies that determine phage infectivity. PLoS Pathog 2023, 19, e1010928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weel-Sneve, R.; Bjoras, M.; Kristiansen, K.I. Overexpression of the LexA-regulated tisAB RNA in E. coli inhibits SOS functions; implications for regulation of the SOS response. Nucleic Acids Res 2008, 36, 6249–6259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butala, M.; Zgur-Bertok, D.; Busby, S.J. The bacterial LexA transcriptional repressor. Cell Mol Life Sci 2009, 66, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornelos, N.; Butala, M.; Hodnik, V.; Anderluh, G.; Bamford, J.K.; Salas, M. Bacteriophage GIL01 gp7 interacts with host LexA repressor to enhance DNA binding and inhibit RecA-mediated auto-cleavage. Nucleic Acids Res 2015, 43, 7315–7329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tram, G.; Poole, J.; Adams, F.G.; Jennings, M.P.; Eijkelkamp, B.A.; Atack, J.M. The Acinetobacter baumannii Autotransporter Adhesin Ata Recognizes Host Glycans as High-Affinity Receptors. ACS Infect Dis 2021, 7, 2352–2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weidensdorfer, M.; Ishikawa, M.; Hori, K.; Linke, D.; Djahanschiri, B.; Iruegas, R.; Ebersberger, I.; Riedel-Christ, S.; Enders, G.; Leukert, L.; et al. The Acinetobacter trimeric autotransporter adhesin Ata controls key virulence traits of Acinetobacter baumannii. Virulence 2019, 10, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, B.K.; Sistrom, M.; Wertz, J.E.; Kortright, K.E.; Narayan, D.; Turner, P.E. Phage selection restores antibiotic sensitivity in MDR Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 26717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; You, X.; Liu, X.; Fei, B.; Li, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhu, R.; Li, Y. Characterization of phage HZY2308 against Acinetobacter baumannii and identification of phage-resistant bacteria. Virol J 2024, 21, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordillo Altamirano, F.; Forsyth, J.H.; Patwa, R.; Kostoulias, X.; Trim, M.; Subedi, D.; Archer, S.K.; Morris, F.C.; Oliveira, C.; Kielty, L.; et al. Bacteriophage-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii are resensitized to antimicrobials. Nat Microbiol 2021, 6, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Loh, B.; Gordillo Altamirano, F.; Yu, Y.; Hua, X.; Leptihn, S. Colistin-phage combinations decrease antibiotic resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii via changes in envelope architecture. Emerg Microbes Infect 2021, 10, 2205–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirnay, J.P.; Blasdel, B.G.; Bretaudeau, L.; Buckling, A.; Chanishvili, N.; Clark, J.R.; Corte-Real, S.; Debarbieux, L.; Dublanchet, A.; De Vos, D.; et al. Quality and safety requirements for sustainable phage therapy products. Pharm Res 2015, 32, 2173–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, S.E.; Villedieu, A.; Bagdasarian, N.; Karah, N.; Teare, L.; Elamin, W.F. Control and management of multidrug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: A review of the evidence and proposal of novel approaches. Infect Prev Pract 2020, 2, 100077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhry, W.N.; Concepcion-Acevedo, J.; Park, T.; Andleeb, S.; Bull, J.J.; Levin, B.R. Synergy and Order Effects of Antibiotics and Phages in Killing Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilms. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0168615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Save, J.; Que, Y.A.; Entenza, J.; Resch, G. Subtherapeutic Doses of Vancomycin Synergize with Bacteriophages for Treatment of Experimental Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Infective Endocarditis. Viruses 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Save, J.; Que, Y.A.; Entenza, J.M.; Kolenda, C.; Laurent, F.; Resch, G. Bacteriophages Combined With Subtherapeutic Doses of Flucloxacillin Act Synergistically Against Staphylococcus aureus Experimental Infective Endocarditis. J Am Heart Assoc 2022, 11, e023080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madison, C.L.; Steinert, A.S.J.; Luedeke, C.E.; Hajjafar, N.; Srivastava, P.; Berti, A.D.; Bayer, A.S.; Kebriaei, R. It takes two to tango: Preserving daptomycin efficacy against daptomycin-resistant MRSA using daptomycin-phage co-therapy. Microbiol Spectr 2024, 12, e0067924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz Coyne, A.J.; Eshaya, M.; Bleick, C.; Vader, S.; Biswas, B.; Wilson, M.; Deschenes, M.V.; Alexander, J.; Lehman, S.M.; Rybak, M.J. Exploring synergistic and antagonistic interactions in phage-antibiotic combinations against ESKAPE pathogens. Microbiol Spectr 2024, 12, e0042724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coulter, L.B.; McLean, R.J.; Rohde, R.E.; Aron, G.M. Effect of bacteriophage infection in combination with tobramycin on the emergence of resistance in Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Viruses 2014, 6, 3778–3786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pons, B.J.; Dimitriu, T.; Westra, E.R.; van Houte, S. Antibiotics that affect translation can antagonize phage infectivity by interfering with the deployment of counter-defenses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2023, 120, e2216084120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (CHUV), L.U.H. DM_DAM_guide_antibiotherapie. https://www.chuv.ch/fileadmin/sites/min/552801_22_DM_DAM_guide_antibiotherapie_version_mai_2022.pdf, Ed. 2022.

- Leshkasheli, L.; Kutateladze, M.; Balarjishvili, N.; Bolkvadze, D.; Save, J.; Oechslin, F.; Que, Y.A.; Resch, G. Efficacy of newly isolated and highly potent bacteriophages in a mouse model of extensively drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii bacteraemia. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2019, 19, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rastegar, S.; Skurnik, M.; Niaz, H.; Tadjrobehkar, O.; Samareh, A.; Hosseini-Nave, H.; Sabouri, S. Isolation, characterization, and potential application of Acinetobacter baumannii phages against extensively drug-resistant strains. Virus Genes 2024, 60, 725–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shibin Li, B.W. , Le Xu, Cong Cong, Bilal Murtaza, Lili Wang, Xiaoyu Li, Jibin Li, Mu Xu, Jiajun Yin, Yongping Xu. In vivo efficacy of phage cocktails against carbapenem resistance Acinetobacter baumannii in the rat pneumonia model. Journal of Virology 2024, 98. [Google Scholar]

- Jeon, J.; Park, J.H.; Yong, D. Efficacy of bacteriophage treatment against carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in Galleria mellonella larvae and a mouse model of acute pneumonia. BMC Microbiol 2019, 19, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.; Zou, J.; Zhang, J.; Qu, J.; Lu, H. Phage therapy for extensively drug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii infection: case report and in vivo evaluation of the distribution of phage and the impact on gut microbiome. Front Med (Lausanne) 2024, 11, 1432703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Chen, H.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, X.; Huang, W.; Ma, Y. Clinical Experience of Personalized Phage Therapy Against Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Lung Infection in a Patient With Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2021, 11, 631585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nir-Paz, R.; Onallah, H.; Dekel, M.; Gellman, Y.N.; Haze, A.; Ben-Ami, R.; Braunstein, R.; Hazan, R.; Dror, D.; Oster, Y.; et al. Randomized double-blind study on safety and tolerability of TP-102 phage cocktail in patients with infected and non-infected diabetic foot ulcers. Med 2024, 100565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eales, B.M.; Tam, V.H. Case Commentary: Novel Therapy for Multidrug-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2022, 66, e0199621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Dai, J.; Guo, M.; Li, J.; Zhou, X.; Li, F.; Gao, Y.; Qu, H.; Lu, H.; Jin, J.; et al. Pre-optimized phage therapy on secondary Acinetobacter baumannii infection in four critical COVID-19 patients. Emerg Microbes Infect 2021, 10, 612–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nir-Paz, R.; Gelman, D.; Khouri, A.; Sisson, B.M.; Fackler, J.; Alkalay-Oren, S.; Khalifa, L.; Rimon, A.; Yerushalmy, O.; Bader, R.; et al. Successful Treatment of Antibiotic-resistant, Poly-microbial Bone Infection With Bacteriophages and Antibiotics Combination. Clin Infect Dis 2019, 69, 2015–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, J.; Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Han, W.; Lei, L.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Gao, Y.; Song, J.; Lu, R.; et al. A method for generation phage cocktail with great therapeutic potential. PLoS One 2012, 7, e31698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Ab125 | |||

| VP | MV50 | ||

| Phage 3014 | 0 | - | |

| Phage 3098 | 0.47 | - | |

| Cocktail 3014/3098 | 0.62 | 1.00E-03 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).