Introduction

Acinetobacter baumannii (AB) is a bacterium commonly found in hospitals, where it acts as a nosocomial pathogen, causing infections in various systems of the body, particularly the respiratory tract, bloodstream, urinary tract, and skin [

1]. AB contamination in hospitals often leads to opportunistic infections in long-term patients. Multi-drug-resistant AB (MDR-AB) strains are a major cause of mortality among patients with weakened immune systems [

2].

AB is an aerobic, non-sugar-fermenting bacterium. It does not form filaments but can move in a twitching manner using pili [

3]. The World Health Organization (WHO) recognizes AB as a highly important antibiotic-resistant bacterium, along with

Enterobacter spp.,

Enterococcus faecium,

Klebsiella pneumoniae,

Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and

Staphylococcus aureus. Due to the limited scope for developing new antibiotics, alternative treatments for MDR bacteria, including AB, have been proposed, with phage therapy emerging as a promising option.

Bacteriophages, or phages, are viruses that naturally infect and kill specific bacteria. Phages can infect bacterial hosts through two main pathways: the lytic and lysogenic cycles. In the lytic pathway, phage infection results in bacterial lysis, releasing new phage progeny that can then infect additional bacterial cells. In contrast, the lysogenic pathway involves the integration of the phage genome into the bacterial chromosome, forming what is known as a lysogen. A lysogen does not produce phage progeny unless induced by agents such as mitomycin C [

4], nalidixic acid, and ciprofloxacin [

5]. Ultraviolet light has also been shown to induce lysogens to enter the lytic cycle through activation of the SOS regulatory system [

6]. Phages are broadly categorized into two types: virulent and temperate. Virulent phages are preferable for phage therapy because they exclusively follow the lytic pathway and do not form lysogens [

7]. Virulent phages can be identified by their formation of clear plaques in plaque assays, in contrast to temperate phages, which produce turbid plaques [

8,

9]. Virulent phages are theoretically more suitable for phage therapy due to these properties. Although virulent phages do not form lysogens, bacterial resistance to these phages can still develop, posing a challenge to successful phage therapy [9-11]. Addressing this resistance is essential for improving therapeutic outcomes.

This study established an in vitro phage treatment model to explore the use of multiple virulent AB-phages to infect an AB isolate, designated ABU-3. Ultimately, three distinct AB-phages were isolated to target the ABU-3 isolate. Phage-resistant ABU-3 cells, induced by each of the three virulent AB-phages, were then isolated to examine potential resistance to each phage infection. This research aims to assess the likelihood of phage resistance in ABU-3s induced by individual phages. Additionally, strategies to optimize phage therapy and prevent induction of the pathogenic bacteria are proposed. The findings aim to provide insights into achieving the most effective practices in phage therapy.

Results

Characterization of the AB-Phages

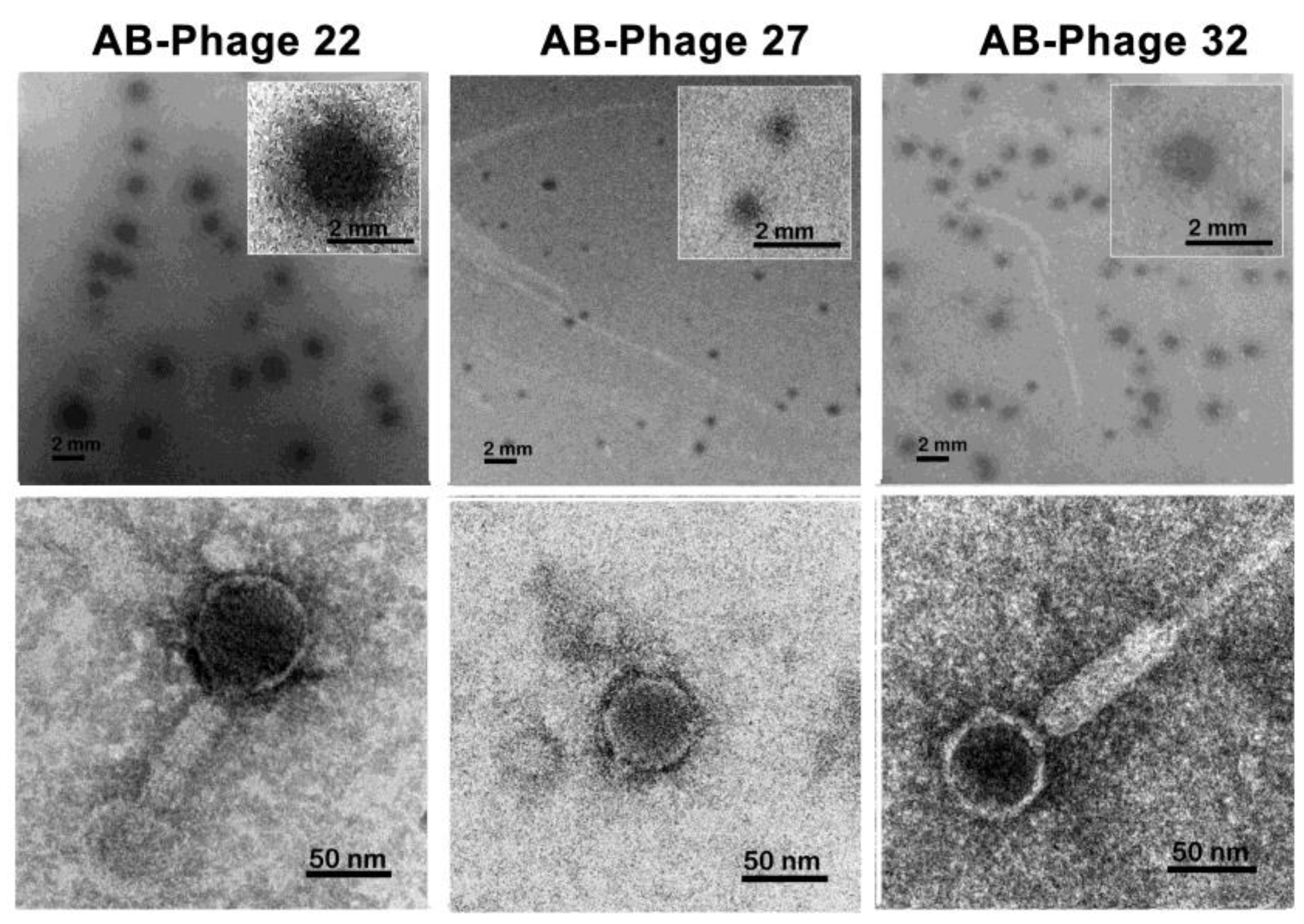

To investigate the association between phage resistance in ABU-3 and susceptibility to other AB-phages, we selected the ABU-3 isolate, which was susceptible to three types of AB-phages: AB-phage-22, AB-phage-27, and AB-phage-32, for further study. Plaque formations of the three phages are shown in

Figure 1. AB-phage-22 formed clear plaques 1.3-2.1 mm in diameter, surrounded by a thick, turbid zone. AB-phage-27 produced plaques smaller than 1 mm, and AB-phage-32 formed clear plaques approximately 1.2-1.8 mm in diameter with a thinner surrounding zone compared to AB-phage-22. Notably, AB-phage-27 appeared distinct from AB-phage-22 and AB-phage-32 due to its smaller plaque diameter. TEM images revealed unique tail morphologies for each phage: AB-phage-22 resembled

Siphoviridae, AB-phage-27 was

Podoviridae-like, and AB-phage-32 displayed a long, contractile tail characteristic of

Myoviridae.

We next examined the physical characteristics of these phages, focusing on their tolerance to pH and temperature. AB-phage-27 became inactive after 1 hour at 56°C, while AB-phage-22 and AB-phage-32 tolerated temperatures of 68-69°C and 66-67°C, respectively, for the same duration. All three AB-phages remained stable after at least six freeze-thaw cycles, as assessed by spot tests and plaque formation methods. Regarding pH tolerance, AB-phage-22 remained partially active after 2 hours at pH 2, whereas AB-phage-32 was completely inactivated under the same conditions. AB-phage-27 became inactive at pH 3. All three AB-phages tolerated alkaline conditions at pH 12 but were inactivated at pH 13.

In Vitro Bioassay of Phage Therapy

We conducted in vitro bioassays to determine the MOI of each AB-phage that could clear ABU-3, referred to here as the MOI clearance of ABU-3. After five tests, MOI clearance results for single AB-phage-22, AB-phage-27, and AB-phage-32 are presented in Table 1. AB-phage-27 showed lower efficiency, with an MOI clearance of 100 in all five experiments. AB-phage-22 cleared ABU-3 once at an MOI of 1 and four times at MOI 10, while AB-phage-32 consistently cleared ABU-3 at an MOI of 10 in all five experiments. While AB-phage-22 could achieve MOI clearance at 1, MOI 10 provided more consistent results, and for safety considerations and to avoid inducing AB-phage resistance AB, MOI 10 was recommended for clearing ABU-3 with AB-phage-22. This model could serve as a basis for clinical trials to determine the optimal AB-phage-to-bacteria ratio for effective AB clearance while avoiding phage resistant induction. Phage combinations in this study, whether with two or all three phages, did not prove more effective than single-phage treatments in achieving MOI clearance of ABU-3.

Phage Immunity of Each Phage-Resistant ABU-3

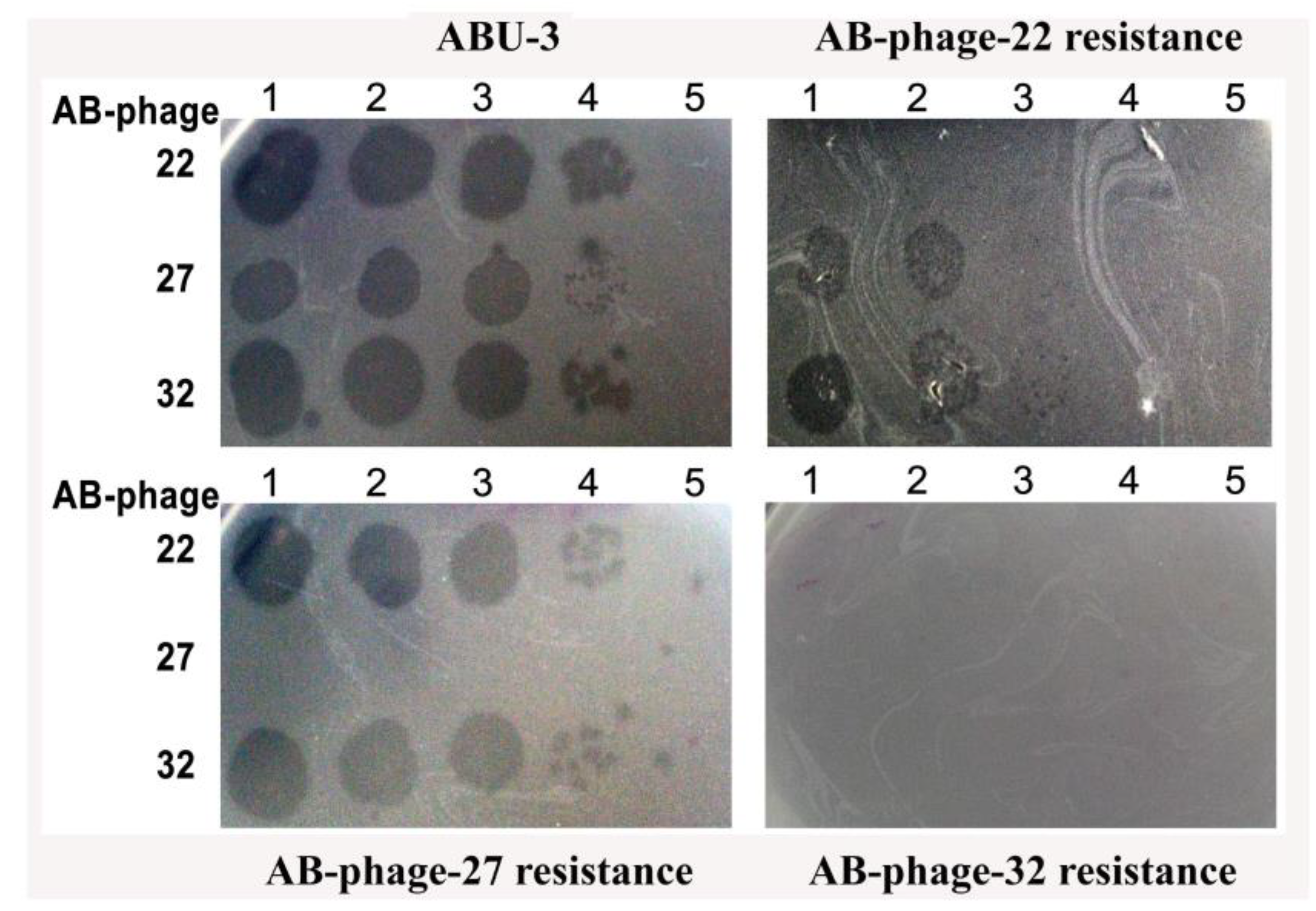

To gain further insight into the phage resistance of each AB-phage-treated ABU-3, we isolated phage-resistant ABU-3 variants: 22-AB-resistant ABU-3, 27-AB-resistant ABU-3, and 32-AB-resistant ABU-3. These phage resistant ABU-3s were tested as target cells against single AB-phages alongside ABU-3 using the spot test. As shown in

Figure 2, 22-AB-resistant ABU-3 completely resisted AB-phage-22 and displayed partial resistance to AB-phage-27 and AB-phage-32, showing approximately a 2-log reduction compared to the parental ABU-3 isolate. In contrast, 32-AB-resistant ABU-3 was resistant to all three AB-phages. On the other hand, 27-AB-resistant ABU-3 did not exhibit increased resistance to other AB-phages except its own. These AB-phage resistant ABU-3 strains were re-identified as AB by routine biochemical tests.

Discussion

This study isolated three AB-phages, AB-phage-22, AB-phage-27, and AB-phage-32, capable of infecting the ABU-3 host, with distinctions in plaque formation and TEM morphology. Although TEM morphology suggests AB-phage-22, AB-phage-27, and AB-phage-32 belong to

Siphoviridae,

Podoviridae, and

Myoviridae, respectively, further confirmation is needed. This article demonstrates that these three AB-phages are likely distinct types based on plaque formation and TEM morphology. Their physical properties show they are tolerant of a broad range of pH levels and temperatures, which is unsurprising given their origin in wastewater. Notably, AB-phage-27 is less heat-tolerant than the other two, becoming inactive above 57°C for 1 hour, while all three tolerate freeze-thaw cycles, simplifying storage. It is also notable that these phages can withstand freeze-thaw cycles, simplifying storage, as they can be frozen without a preservative agent while maintaining their activity. Additionally, AB-phage-22 has been tested for lyophilization and retained its activity. However, long-term preservation requires further observation [

15,

16].

Given the increasing incidence of bacterial resistance to antibiotics, phage therapy presents an attractive option for preventing and treating bacterial infections, including those caused by AB. However, phage therapy has limitations, particularly due to the highly specific interaction between each phage and its bacterial host. No single phage can infect all strains of a bacterial species, although some can infect multiple strains. Addressing this limitation requires a collection of phages ready for therapy, which demands time, cost, and labour [

16,

17]. This could occur if an insufficient phage dose is used during the initial treatment. With multi-phage infections of ABU-3, there is an opportunity to study phage immunity more deeply.

As shown in

Figure 2, this study found varying levels of super-infection immunity among three different AB-phages in the three phage-resistant ABU-3 strains: definite immunity in the AB-phage-27-resistant ABU-3, which was resistant to its original AB-phage-27 but not the other two AB-phages. In contrast, the AB-phage-32-resistant ABU-3 was not only resistant to its initial AB-phage but also showed broad immunity to the other two AB-phages. Meanwhile, the AB-phage-22-resistant ABU-3 was fully resistant to its initial phage, as expected, but exhibited partial resistance to AB-phage-27 and AB-phage-32, showing nearly two log reductions compared to the original ABU-3 host. Notably, not all surviving AB bacteria from a suboptimal phage ratio developed resistance to the primary infecting phage; over 50% remained susceptible to the same AB-phage. This could be due to a transient resistance mechanism occurring during the infection process [

19]. Nonetheless, the three isolated AB-phage-resistant ABU-3 strains were consistently resistant to their corresponding AB-phages.

Different theories have been proposed to explain super-infection immunity [

20]. One early hypothesis involves the expression of a repressor gene, such as the

CI repressor, which suppresses the lytic cycle and prevents super-infection by the same phage. This hypothesis suggests that super-infection immunity could extend to related phages, resulting in a broader immunity—known as super-infection exclusion [

21]. However, the definition of "related phages" remains vague in this context and does not fully account for immunity mechanisms with related phages. Another hypothesis, the inducible receptor concept, suggests that phages or viruses using the same or related cellular molecules as receptors/co-receptors for entry may be blocked by the down-regulation of these molecules during phage penetration, similar to mechanisms observed in sperm-egg fertilization [

22]. This concept, however, may not fully explain the partial broad immunity of the AB-phage-22 lysogen, which remains sensitive to higher concentrations of AB-phage-27 and AB-phage-32. A more recent proposal based on the CRISPR-Cas system, which functions as an adaptive immunity-like mechanism in prokaryotes, provides a clearer explanation of super-infection immunity [20, 23]. However, this model also fails to explain partial super-infection exclusion, indicating a need for further investigation. Understanding the mechanisms behind super-infection immunity is crucial for developing strategies, such as modifying phage genomes, to prevent induction of phage resistance and enhance the success of phage therapy. While progress has been made, much remains to be explored.

To counteract the induction of phage-resistant AB during phage therapy, we emphasize the importance of using sufficient phage quantities to completely clear ABU-3 cells and prevent the development of phage resistance. We propose determining the MOI clearance value as a standard procedure for phage therapy. In this study, as shown in

Table 1, the MOI clearance values for AB-phage-22, AB-phage-27, and AB-phage-32 were 10, 100, and 10, respectively. These MOI values represent the optimal concentrations needed to eliminate all ABU-3 cells. We propose testing MOI clearance to prevent induction of phage resistance in pathogenic bacteria. Previous studies have suggested that phage cocktails are more effective in phage therapy [

24,

25]. However, this study did not support the hypothesis that phage cocktails are more effective than single-phage treatments. It is important to note that our study evaluated the efficiency of phage therapy by focusing on complete bacterial clearance to prevent the induction of phage-resistant AB strains, rather than merely reducing bacterial numbers, which could still result in the emergence of phage resistance. Phage-resistant AB strains could proliferate and potentially develop resistance not only to the initial AB-phage but also to others. While phage cocktails could offer the advantage of targeting a broader range of pathogenic bacteria, they may also induce resistance over a wider range. The pros and cons of cocktail phage therapy should be carefully evaluated. We recommend determining the MOI clearance of bacterial pathogens when it is not an emergency. Our priority is to ensure complete patient recovery without later complications. Based on our pilot tests, which involved a single experiment on the MOI clearance of 12 other AB isolates susceptible to these three AB-phages, an MOI of 100 was consistently effective in clearing all AB isolates. Although an MOI of 10 led to a significant reduction, a few colonies survived, whereas MOI 100 was consistently effective. This suggests that an MOI of 100 might serve as a clearance threshold for AB by all three AB-phages. Further research involving a larger sample size of AB and AB-phage strains is needed. If validated, this approach could be advantageous for practical phage therapy with cocktail phages in emergencies, even if MOI clearance testing is not possible beforehand.

Materials and Methods

Acinetobacter Baumannii [AB]

Various AB isolates were collected from the microbiology laboratory of Srinakarin Hospital, Khon Kaen, Thailand. These isolates were obtained from the tracheal suction fluid of bronchitis patients and identified through biochemical testing. The isolates were stored in 50% glycerol at -80°C until further use. Prior to experimentation, the isolates were sub-cultured, and their biochemical profiles and antibiotic susceptibility to doxycycline, amikacin, imipenem, and levofloxacin were reconfirmed.

Enrichment and Preparation of AB Phage

Phage samples were collected from waste water sources in the vicinity of Srinakarin Hospital, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen Province. The waste water samples, approximately 40-45 ml in volume, were filtered through a 0.22 µm membrane filter. For enrichment, 9 ml of the filtered sample was mixed with 1 ml of a mixture of 4-5 AB isolates at a concentration of 10⁶-10⁷ CFU/ml. The mixture was supplemented with an equal volume of 2X brain heart infusion [BHI] broth and incubated at 37°C with shaking for 4 hours. After incubation, the mixture was centrifuged at 5,000 g for 15 minutes, and 2 ml of the supernatant was incubated with a single isolate at 37°C with shaking for 2-4 hours. The presence of phage was indicated by a clearer appearance of the test tube compared to the control. The sample was then centrifuged at 10,000 g for 15 minutes, and the supernatant was filtered through a 0.22 µm membrane and stored at 4°C for further study. AB-phages were amplified by infecting AB cultures at different MOI, ranging from 0.1 to 10. Phage titres were determined using 10-fold dilution with SM buffer [50 mM Tris-Cl pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 8 mM MgSO₄] and quantified by spotting and double-layer agar methods [

12].

Screening and Isolation for AB-Phage Susceptibility

Forty AB isolates were screened for susceptibility to the isolated phages using the spot test method. AB lawns were prepared on MacConkey or nutrient agar plates by mixing bacterial cultures with 0.5% nutrient agar. Ten microliters of phage suspensions were spotted onto the lawns, and plates were incubated at 37°C for 8–12 hours. Clear plaques indicated phage susceptibility. Only AB isolates susceptible to at least two different phages were selected for further analysis. If a particular AB strain exhibited different plaque appearances using the double-layer agar method, individual plaques were isolated [

13]. Phage purification was performed by isolating plaques with a pipette tip, amplifying them with the susceptible AB isolate, and incubating overnight at 37°C to evaluate the unique clear plaque. This process was repeated to ensure the purity of the isolated phage.

Physical Characterization of AB-Phages

The stability of AB-phages was evaluated under varying pH, temperature, and freeze-thaw conditions. Phages at a concentration of 10⁷ PFU/ml were diluted 100-fold in SM buffer prepared at different pH values, ranging from pH 2 to 13. The mixtures were incubated at room temperature for 4 hours. For thermal stability, each of the AB-phages was kept at temperatures ranging from 45°C to 75°C by Bio-Rad C1000Dx Thermal cycle for 1 hour. Freeze-thaw stability was assessed by freezing phage suspensions at -20°C for 8 hours to overnight, followed by repeated freezing and thawing for 6 cycles. Phage survival was confirmed by spot test and double-layer agar methods.

Phage Morphology Examination

AB-phage morphology was examined using transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Phage suspension, at least 10⁹ PFU/ml, were applied to copper grids and allowed to settle for 3 minutes. Dried with filter paper, and stained with 1% uranyl acetate. The grid was stored in a desiccator overnight before TEM imaging [

14].

Bioassay of AB Phage Therapy

AB-phage concentrations were prepared at 10⁹-10¹⁰ PFU/ml. Each phage was diluted in serial 10-fold dilutions and delivered to each well of a microtiter plate in a volume of 90 µl. For tests involving multiple AB-phages [e.g., three phages], 30 µl of each phage was added to make a total volume of 90 µl. Ten microliters of AB suspension were then added to achieve different MOIs (0.1, 1, 10, 100, etc.). The plate was incubated at room temperature and 37°C with shaking at 80 rpm overnight. Ten microliters of the AB and AB-phage mixture were spotted on MacConkey medium and incubated at 37°C overnight to observe AB survival. AB suspensions were re-counted to confirm by pour plate technique and adjust MOI calculations in each experiment.

Isolation and Phage Immunity of AB-phage Treated ABU-3

The phage-treated ABU-3, which survived exposure to each of the three AB-phages, was isolated by exposing ABU-3 cultures to AB-phages at 1 log lower than the MOI clearance level, followed by culturing on nutrient agar. The phage- treated ABU-3 isolates were tested for resistance to each corresponding AB-phage and confirmed to be resistant to the same phages that induced resistance. The resistance of ABU-3 to each AB-phage was also re-evaluated after storage in nutrient medium at 4 °C for approximately one week. Lawns of each phage-resistant ABU-3 were then tested for immunity to all three AB-phages by spotting phage suspensions and comparing the results to the parent ABU-3 isolate. Phage solutions ranging from 10⁴ to 10⁸ PFU/ml were spotted onto each bacterial lawn, incubated overnight at 37°C, and observed for plaque formation on both the phage-resistant ABU-3 and the parent ABU-3 lawns.