1. Introduction

Many children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) demand specialized interventions to address impairments in verbal and non-verbal behavioral repertoires. In Behavior Analysis, these are referred to as operants, which are shaped and maintained by environmental changes/consequences also known as reinforcers [

1]. The branch of behavioral science, which is concerned with the modification of socially relevant repertoires, is called Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) [

2]. The principles and procedures to induce behavior change may be applied to different individuals, including learners with ASD. Especially in cases of children with significant developmental delays, systematic intensive behavioral interventions are warranted [

3,

4].

The interdisciplinary dialogue between behavioral science and neuroscience has highlighted how structured learning experiences, such as those promoted by ABA interventions, contribute to experience-dependent neuroplasticity, defined as the brain's ability to reorganize its structure and function in response to environmental stimuli throughout life [

5,

6]. These changes are particularly relevant in developmental conditions like ASD, where targeted interventions can modulate neural pathways associated with language, attention, and social cognition.

One important teaching format to establish verbal and non-verbal behaviors in learners with ASD is known as discrete trial teaching (DTT). This method is commonly used in structured environments with distraction control, and it may consist of up to five steps: 1) Provision of instruction (discriminative stimulus); 2) provision of prompt (response model); 3) response emission by the learner; 4) presentation of differential consequence when responding; 5) provision of intertrial interval. As an example, a therapist may say “raise your hands” and a given learner emits the corresponding response of raising his/her hands up to 5s after instruction. Thereafter, the therapist praises the learner and allows access to a type of arbitrary reinforcer (e.g., a preferred video or toy). Then, an interval of 3s elapses before administering a new teaching trial. In a trial, if an error is made, or no response occurs during the allowed time, a correction procedure is applied (e.g., provision of physical guidance). If necessary or important, during some trials to teach the repertoire, an immediate prompt may be delivered (the therapist models the response of raising hands right after instruction). Over the course of several trials, the prompt is faded out to establish the intended discrimination (e.g., the emission of raising hands solely under its specific verbal instruction) [

7,

8].

Repeated structured experiences such as DTT are hypothesized to reinforce synaptic plasticity mechanisms by providing consistent and meaningful behavioral contingencies that may shape functional brain circuits, particularly in regions associated with executive functions, reward processing, and sensory integration [

5]. The growing number of children diagnosed with ASD around the world makes it important to train a greater number of professionals who may provide ABA interventions with methodological integrity. During the provision of DTT instruction, this is represented by the number of components demonstrated correctly by therapists (e.g., securing the learner’s attention demanding visual contact; providing consistent instructions specifying expected responses; delivering a reinforcer solely after the emission of an independent response etc.) [

9]. A set of scientifically well-founded strategies for training professionals interested in ABA and its application to the treatment of ASD is called Behavioral Skills Training (BST) [

10].

Structured and consistent training of professionals to implement ABA strategies with high fidelity is not only essential for maintaining behavioral accuracy but may also enhance the learner's capacity to detect patterns, sustain attention, and regulate actions within predictable learning environments. Evidence suggests that repeated exposure to well-organized, goal-directed interactions, particularly those involving reinforcement contingencies and social feedback, can promote adaptive changes in how individuals engage with their environment, supporting the consolidation of new behavioral repertoires over time [

6].

The BST consists of four components: 1) Vocal and written didactic instructions for carrying out ABA interventions; 2) modeling (demonstration on how the interventions should be implemented); 3) role-play (the professional delivers interventions in simulation with a confederate pretending to be a student with ASD, or the process involves direct interactions with a real student with ASD); 4) performance feedback for the professional regarding methodological successes and errors during the provision of interventions. In the literature, several studies investigated the effects of training professionals via BST on teaching repertoires adequately to students with ASD through DTT [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15].

Sarokoff and Sturmey [

10] trained three teachers to implement DTT to teach matching-to-sample to a 3-year-old child with ASD through BST (instructions, feedback, rehearsal, and modeling). Sessions occurred in the child’s home. A multiple baseline design across participants was used to assess the effects of BST on professionals’ performance. There was great improvement in the integrity of the intervention carried out by all teachers. Sarokoff and Sturmey [

14] also used a multiple baseline across participants to train three professionals to implement DTT to teach matching to sample to a student in a school setting for children with ASD. As in the previous study, BST improved the integrity of the intervention conducted by all professionals. Moreover, performance accuracy was also demonstrated in follow-up sessions involving new students and programs to teach receptive sight words and other receptive skills. All students showed gains in the taught repertoires. They had prior experience learning skills through DTT. In both studies [

10,

14], the professionals had prior experience implementing DTT, although BST increased teaching integrity from below 50% to 100% (or nearly 100%) DTT components performed correctly. In both studies, the conditions involved solely interactions with children with ASD (no sessions with a confederate). Finally, a limitation highlighted by the authors was that it was not possible to determine which components were necessary to increase the integrity of teaching via DTT.

Lerman et al. [

9] trained nine special education teachers to conduct preference assessments and direct teaching of repertoires in a school. 16 students with atypical development aged 3 to 18 years old also participated. A multiple baseline design across teachers was used. The training focused on didactic instruction regarding behavioral principles, managing disruptive behaviors, sessions involving modeling and practice with feedback on types of preference assessments and prompt procedures to teach skills. As a result, all teachers demonstrated high levels of performance accuracy compared to baseline. The high integrity was also shown by most of the participants in follow-up sessions three months after training. A limitation of the research was that the impact of training on students’ repertoire was not investigated.

Clayton and Headley [

11] trained three paraprofessionals via BST to teach repertoires (saying names of words printed on flash cards or selecting them receptively) through DTT. A multiple baseline design across participants was used. The participants had no prior experience implementing DTT and practice sessions occurred with students with ASD aged 5 to 8 years old. As a result, all participants demonstrated improvement in teaching integrity to nearly 100% DTT components implemented correctly. Unlike previous research [

10,

14] in which printed handouts with definitions of DTT components were provided in baseline, in Clayton and Headley [

11], a video recorded demonstrating the components without narration were provided in baseline. According to the authors, this variable may have been responsible for strong performance accuracy for all participants in baseline, being a limitation.

Souza et al. [

15] trained three professionals using a multiple-probe design to teach repertoires via DTT to three children with ASD between 6 and 12 years old in a center for ASD treatment. Before the study, the professionals had prior experience with ABA, although not implementing DTT. During BST, role-play sessions were conducted with the experimenter pretending to be a learner with ASD. After a learning criterion was achieved, new sessions were conducted with children with ASD. As a result, performance accuracy during implementation of DTT improved for all professionals and high integrity was also demonstrated in maintenance sessions 4 weeks after BST. All children showed improvements in the acquisition of skills. During training, they were taught repertoires from the Promoting the Emergence of Advanced Knowledge (PEAK) [

16]. They consisted of receptive language of object performance, motor imitation of basic shapes and named money. Generalization probes were conducted 5 weeks after BST and two of the professionals conducted DTT with high integrity. They taught a new repertoire consisting of receptively labeling community helpers. Maintenance and generalization phases were not conducted with the remaining participant, which was a limitation. Another limitation not directly pointed out by the authors was that teaching integrity was relatively high in baseline for all participants regarding the teaching of several repertoires. This could be related to the participants’ prior experience with ABA.

Matos, Hübner, et al. [

12] used a multiple probe design across participants to assess the effects of BST during the training of six psychology students, who were interns in a university-based laboratory where the research was carried out. Although they were familiar with basic processes in Behavior Analysis, they had no prior experience with ASD and DTT. BST was conducted under two conditions: Immediate and delayed feedback. During the first condition, performance feedback was provided after every DTT trial during the session. In the second condition, feedback was only delivered after several DTT trials at the end of the session. Training involved interactions with a confederate. The participants taught verbal behavior repertoires. Everyone demonstrated improvement in teaching integrity, which also generalized to the teaching of real children with ASD. One limitation of the study was that the participants demonstrated relatively high teaching integrity in baseline. This may be related to the fact that these psychology students were able to observe interventions to children with ASD provided by more experienced university students in the laboratory, independent of the research carried out. This variable was not controlled because the participants were part of an observational internship in the laboratory. Finally, although generalization of teaching integrity was measured during the teaching of children with ASD, the impact of training on skill acquisition by the children was not investigated.

Matos, Nascimento, et al. [

13] trained six psychology students in the same university-based laboratory where a previous study [

12] took place. Two BST training conditions were compared. The only difference between them was regarding one of the components (modeling). In one case, modeling consisted of experimenter and research assistant simulating in-person interactions between therapist and child with ASD for the teaching via DTT. In the other case, video modeling was used, that is, videos simulating interactions between therapist and child were shown to the participants instead. The two types of BST were compared using a within-participant design of alternating treatments. Each participant was trained to teach two pairs of verbal and non-verbal repertoires (one pair for each type of BST). The alternating design was also embedded into a multiple probe design across participants. During training, feedback was provided in a manner similar to the previous study [

12], that is, sessions were conducted with immediate and delayed feedback. As a result, all participants demonstrated improvement in teaching integrity above 80% DTT components concluded correctly. During baseline, teaching integrity was low (below 50%) for everyone. There were no interactions with real children with ASD to assess generalization, which was a limitation. A critical variable in this sense was the COVID-19 pandemic, making interactions with children unfeasible (university managers suspended services for children). Both BST with modeling and video modeling were similarly effective and efficient, demanding a similar number of sessions to achieve a learning criterion. On average, training each psychology student lasted 3 hours and 20 minutes. This data suggests that training BST with video modeling may represent a more cost-effective workout as it involves fewer trainers and effort (making the cost of its implementation lower).

So far, the investigations discussed demonstrated that BST effectively increased the teaching integrity by professionals (and university students as future professionals) during the provision of DTT in simulated sessions with a confederate and sessions with children with ASD. In some studies, a limitation was that baseline levels of integrity were relatively high across participants (above 50% DTT components implemented correctly) [

11,

12,

15]. In others, no generalization measures of integrity regarding teaching children with ASD were obtained [

13] or the impact of training on the acquisition of skills in children with ASD was not measured [

9,

11,

12,

13]. As in a previous case [

13], the current research was also interested in analyzing the effectiveness and efficiency of two types of BST (one including in-person modeling vs. another including video modeling) among different participants. The two types of training were not compared because each participant was assigned to just one type. However, considering the parameters (effectiveness and efficiency) used in the previous study, some considerations need to be made regarding the within-participant alternating treatments design.

An alternating treatments design reduces sequence effects, which can be identified in research involving multiple treatments [

17]. Rapid switching between them does not produce a specific sequence and decreases comparison time. However, it can be difficult to determine whether the effects of the treatments would be the same if each had been implemented alone. Therefore, a disadvantage of the design is that multiple treatments may favor interference effects on a dependent variable. In previous research [

13], although each type of BST training was defined during the teaching of a given pair of repertoires, the possibility of interference effects of one training on the other cannot be ruled out. Furthermore, the types of BST for each participant differed in only one component (modeling) and this may have increased the chances of interference between them in establishing greater integrity in the teaching of repertoires by university students.

Considering the above, in this research, instead of a withing-participant design, the effects of training were investigated with a multiple-probe design across different participants. All participants (university students) needed to meet the criterion of being unfamiliar with ABA interventions applied to ASD and demonstrate a similar (low) level of accuracy (low teaching integrity) in teaching repertoires via DTT to a confederate in probe and baseline sessions. As mentioned before, participants were randomly assigned to just one of two possible types of BST training. This was done to avoid possible interference effects between the two types of training for each participant, as may have occurred in previous investigation [

13] due to their alternating treatments design [

17]. So, the current study sought to examine levels of efficacy and efficiency of two types of BST training without interference effects in two groups: one group of participants for whom BST included in person modeling and another for whom BST included video modeling. Showing 90% (or above) DTT components implemented correctly (e.g., providing instruction consistently, delivering a reinforcer only after emission of correct response etc.) was arbitrarily defined as a measure of BST effectiveness. The number of sessions required to finish training represented the measure of BST efficiency. The amount of time required to complete training was also measured representing efficiency. Finally, generalization of teaching integrity was assessed in post-probed sessions involving DTT with children with ASD.

Regarding video modeling, it is important to discuss that some behavior analysts have demonstrated concern with the development of procedures that may reduce the amount of time required to train people interested in teaching repertoires based on ABA principles. There is also concern regarding the possibility of less participation of behavior analysts’ trainers at a face-to-face level. This is justified because in a country as large as Brazil there is a high demand for training people due to existence of many children and young people with ASD needing more comprehensive ABA-based interventions. Barboza et al. [

18], for example, assessed the efficiency of instructional video modeling in the training of caregivers (mothers of children with ASD) to implement repertoire teaching via DTT. Three dyads (mother-child with ASD) participated. In baseline phase, teaching integrity varied from 45.5% to 65.5% DTT components implemented correctly during the teaching of two repertoires to a confederate.

The mothers only had access to written instructions on how to teach the skills in baseline. During the intervention, each mother watched three instructional videos concerning skills needed for an accurate implementation of DTT (the videos included instructions, video demonstrations, highlights and instructional subtitles). After this, each mother had another opportunity to teach each repertoire as in baseline. Teaching integrity needed to be at least 80%, otherwise another video modeling session would be conducted. If this was the case, but not sufficient to increase the integrity, verbal feedback on how to implement DTT would be delivered by an experimenter. If teaching integrity did not increase even so, a second level of feedback involving role-playing with immediate feedback would be applied. As a result, teaching integrity increased significantly for all participants (varying from 93.5% to 100% DTT components implemented correctly) before the provision of feedback. Training took on average 3 hours to finish. Generalization through the accurate teaching of a new repertoire to a child with ASD was demonstrated. Plus, accurate teaching was maintained one month later. Although the results suggest that less participation of the behavior analyst trainer may be needed (little or no feedback to the mothers), the authors stated that instructional video modeling reaches full potential as part of a more comprehensive training involving presence-based interactions of the mothers (or other caregivers, students or professionals) with the behavior analyst trainer. In the study, experimental control was established through a nonconcurrent multiple baseline across participants design [

18]. In previous research [

19], similar results were produced also using a multiple baseline design. Nevertheless, this one was considered by them an imperfect implementation of multiple baseline design because the participants had a similar number of baseline sessions, being either four or five.

Instructional video modeling also proved to be cost-effective in research of clinical trial for ASD, and that involved many parents as students (67). The parents learned to accurately evoke eye contact and joint attention and to decrease disruptive behaviors commonly emitted by their children [

20]. More recently, instructional video modeling was also used along with feedback (provided remotely through internet) to teach eight caregivers to provide naturalistic teaching interventions of repertoires to four children with ASD. All caregivers learned to teach skills accurately [

21].

It is important to discuss that, in the current study, unlike Barboza et al. [

18], video modeling (for whom it was applied) was a component of a more comprehensive training involving presence-based interactions of psychology students with an experimenter as behavior analyst trainer, making the current research original. So, video modeling was one of the components of BST that also involved didactic instructions, role-play and feedback. These three other components involved in-person interactions with an experimenter. The video modeling component consisted only in the presentation of videos, without narration, representing interactions between two actors simulating the teaching of repertoires via DTT. Regarding other participants for whom BST training was defined with in-person modeling, this was the only difference. In-person modeling involved an experimenter and a confederate (a research assistant) playing the role of interventionist and child with ASD, simulating the teaching of skills via DTT. And the purpose of this new study, as it was previously mentioned, was to analyze the effectiveness and efficiency of the two types of BST training described, without interference effects between them, with each type of training being randomly assigned to a different group of psychology students as participants.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Ten psychology students between 19 and 24 years of age participated in the investigation. It took place in an assessment, research, and intervention laboratory for ASD in a Brazilian university. All participants were unfamiliar with ABA interventions (including DTT) and ASD. Moreover, to be included in the research, participants’ teaching integrity had to be below 50% DTT components implemented correctly. Anyone with integrity level above this criterion would be dismissed from the study.

The process of training each participant via BST occurred through direct interactions with a confederate, who simulated behaviors of a child with ASD. However, probe sessions were planned and implemented at the end of the study to assess generalization of the teaching integrity of repertoires to real children with ASD. Six children aged between 3 and 10 years old were involved. They received interventions once a week for 1 hour and a half in the laboratory at the university where the research took place. Only children who did not present physical aggressive behaviors (hetero-aggression, self-injury, and property destruction) were included. Children who demonstrated these types of behaviors would be excluded from the research.

2.2. Environment

Data collection took place in a room from the university-based laboratory previously mentioned. Inside the room, there was a table and two chairs. At times, each participant could observe demonstrations by an experimenter on how the teaching of repertoires should be done. For six participants, the experimenter and a confederate (playing the roles of interventionist and child with ASD, respectively) sat on the two chairs facing each other and models on appropriate teaching of repertoires were provided (in-person modeling).

As for the remaining four participants, each of them and the experimenter sat on the two chairs facing each other. The experimenter presented videos/recordings without narration, using tablets or cell phones, of two people (one playing the role of an interventionist and the other, of a child with ASD) demonstrating the teaching of repertoires (video modeling). In role-play sessions, regarding all ten participants, each sat in front of the confederate to teach repertoires. This occurred in probe and baseline sessions, when performance feedback was not provided, and in training sessions with feedback.

2.3. Materials

During role-play sessions, the ten participants had to teach repertoires to a confederate or child with ASD (for generalization purposes). At these moments, an experimenter used a recording sheet with the aim of verifying compliance and non-compliance among 13 possible DTT components of each discrete trial of repertoire taught by each participant in the research. The more components completed correctly, the greater the level of teaching integrity.

The components were as follows: 1) organization of the material before teaching; 2) evoking the learner’s attention demanding eye contact; 3) providing instruction consistently; 4) providing appropriate help when needed; 5) reinforcer delivery after emission of correct response; 6) pairing the reinforcer with praise; 7) using varied reinforcers; 8) allowing access to reinforcers when the learner demonstrates attention; 9) allowing access to reinforcers contingent to the emission of appropriate response (e.g., if the learner responded correctly but shouted, it would not be accepted); 10) removing distractions, if any; 11) managing undesirable behaviors appropriately; 12) programming intertrial intervals; 13) carrying out data recording appropriately.

Under conditions in which each participant taught repertoires to a learner (confederate or child with ASD), part of the stimuli used was organized using plastic cards, measuring 6 × 3cm. These contained images depicting different categories such as animals and transportation. When a learner emitted a correct response in a DTT trial, praise and temporary access to a preferred game were provided. Each participant used a recording sheet to take data on the learner’s performance.

2.4. Dependent Variable and Independent Variable

The dependent variable (DV) of this study consisted of the number of DTT components completed correctly (teaching integrity) during the teaching of repertoires by the participants to the confederate and children with ASD. As stated before, each psychology student participant, for each teaching trial administered by him/her in each session to a confederate or child with ASD as learner, could implement among 13 possible DTT components. It is important to say that in trials in which the learner emitted a correct response, a correction component was not applicable. In trials in which the leaner emitted an incorrect response, components regarding reinforcer delivery were not applicable. The component of managing undesirable behaviors would be applicable solely during trials in which the confederate simulated minor harmless inappropriate behaviors. Anyway, in every teaching trial administered by a participant, the implementation of all 13 DTT components would never be possible.

The data was organized in a percentage format per session, that is, the number of DTT components completed correctly were divided by the total number of possible components. The result was multiplied by 100. The independent variable (VI) consisted of BST training with immediate and delayed performance feedback. For six participants, the BST package included written and vocal instructions on teaching target repertoires via DTT; in-person modeling; role-play and performance feedback. For the remaining four participants, the only difference was the fact that modeling was carried out using videos (video modeling).

2.5. Interobserver Agreement and Procedure Integrity

In 30% of the research, a second observer, in addition to the experimenter, recorded DTT components completed correctly and incorrectly during the teaching of repertoires by the participants. The purpose was to establish the level of interobserver agreement (IOA) between the two observers. The number of trials with agreement was divided by the total number of trials and the result was multiplied by 100. The average percentage of IOA, regarding the ten participants, was 98.46%. The second observer also performed integrity records during the implementation of training procedures (BST, including modeling and performance feedback) by the experimenter. The number of correct implementations was added to the total number of implementations, and the result was multiplied by 100. The average percentage of integrity was 99.28%.

2.6. Experimental Design

To ensure control of IV (BST training with in-person modeling or video modeling depending on the participant) over DV (number of DTT components completed correctly during the teaching of repertoires to a confederate and child with ASD), a variation of a multiple baseline design, that is, multiple probe design across different participants was used [

22]. The participants were organized into pairs. Three pairs went through BST training with in-person modeling, and two pairs went through BST training with video modeling. At the beginning of the investigation with each pair, an initial probe session to assess teaching integrity of repertoires to a confederate was administered for both participants. After that, the other research conditions were carried out with one of them. It is important to mention that the design used was an “imperfect” design as can be noted in other investigations from the literature on training caregivers and university students interested in implementing DTT [

12,

13,

18,

19,

23]. By imperfect design, it means that, in this study during baseline as in the case of the previous studies mentioned, the number of sessions before the onset of BST training was similar across participants (only two sessions/data points in the case of the current research). The research team from this investigation knows that a more rigorous experimental design is important to increase internal and external validity of data (baselines with different numbers of sessions/datapoints across participants). Besides, ideally, for a better demonstration of experimental control, it would be important to use a multiple probe design with more than two tiers. However, the university laboratory in which data collection was taken represents a context for the development of research, teaching and extension activities.

There were many children in the community demanding structured DTT ABA interventions and psychology students from the university were (and continuously are) trained via BST to implement the interventions. So, an imperfect two-tier multiple probe design across pairs of participants was intentionally used to speed up the training process. Previous investigations also used a two-tier multiple probe or non-concurrent multiple baseline design [

12,

13,

23,

24]. In the current investigation, data collection took place between the years 2021 and 2022. Originally, six pairs of psychology students were meant to be the participants (three pairs randomly assigned to BST with in-person modeling and three pairs randomly assigned to BST with video modeling). However, regarding a possible pair of participants assigned to BST with video modeling, one student contracted COVID-19 and was unable to participate in the research. Another student, who would serve as his peer, withdrew her consent to participate and this was respected. That was the reason for the unequal number of participants between the two types of BST training. Another participant (referred to as P2) also contracted COVID-19, but, before that, he was able to nearly finish all stages of BST training.

Baseline in this study was administered after the initial probe session for each participant and, once the criterion of teaching integrity below 50% DTT components completed correctly was demonstrated, BST training with immediate feedback began. Written and vocal didactic instructions regarding the teaching of repertoires were provided by an experimenter once and were followed by the demonstration of correct teaching (either in-person modeling or video modeling depending on the participant) in 12 trials once (no data collection on teaching integrity was conducted during didactic instructions and in-person/video modeling). Thereafter, roleplay and performance feedback were carried out with data collection. After teaching integrity reached the criterion of at least 90%, BST training was administered with delayed feedback (the delayed performance feedback was the only difference compared to BST with immediate feedback) and similar termination criteria. Finally, a probe to verify the generalization of high integrity during the teaching of a child with ASD was conducted. After that, the same baseline conditions, BST training with immediate and delayed feedback and generalization probe were carried out with the second participant from each pair. The demonstration of greater teaching integrity only through the implementation of IV for every participant would be interpreted as an experimental control measure.

2.7. Procedure

The research was carried out in four stages: 1) probe and baseline to assess initial levels of teaching integrity of repertoires to a confederate before implementation of training; 2) BST training with immediate performance feedback to improve teaching integrity; 3) BST training with delayed performance feedback to improve teaching integrity; 4) Generalization probe session to assess teaching integrity of repertoires to children with ASD. Relevant information about each of these stages is presented below.

Probe and baseline. A week before this stage, all participants had access to part of a manual to read written descriptions on how to teach the following repertoires through DTT [

25]: Following instructions (e.g., raising hands under the verbal instruction “raise your hands”); listener responding by function, feature and class/LRFFC (e.g., selecting the picture of dog in an array with several pictures and under the verbal instruction “show me dog”); intraverbal by function, feature and class (e.g., saying “car” under the verbal instruction “name a transportation”); tact/labeling (e.g., saying “ball” in the presence of the picture of ball); motor imitation (e.g., clapping hands under the non-vocal model of clapping hands); sitting still (e.g., correcting the posture to an erect position while sitting, following a model); pairing identical pictures (e.g., selecting the picture of apple in an array with several pictures and under the control of another picture of apple as model); mand/making request (e.g., saying “cookie” to receive a piece of a desired cookie). The manual also contained general descriptions on managing disruptive behaviors according to function. The definition of the mentioned repertoires in this investigation was because their teaching is commonly addressed to children with ASD monitored in the university laboratory in which the research was conducted.

After a week, each participant contacted a confederate, a research assistant, playing the role of a child with ASD in the laboratory. During each probe or baseline session, each participant taught four repertoires in 12 trials to the confederate, who followed a script on how she should behave throughout DTT trials to respond (by emitting either incorrect or correct responses; by not responding; by engaging in minor atypical behaviors that required management). The repertoires whose teaching was carried out, and which were also explored in the BST training stages of the study were: following instructions, LRFFC, intraverbal and tact. Another four repertoires (motor imitation, sitting still, pairing identical pictures and mand) were only addressed during the generalization stage, in which the participants interacted directly with a child with ASD.

During each probe or baseline session, each participant administered 12 DTT trials to teach the four repertoires previously mentioned (four trials of each) to the confederate. The experimenter did not provide performance feedback to the participants during any probe or baseline trials. The experimenter simply recorded the number of DTT components completed correctly or not, as a way of measuring the participants’ level of teaching integrity. The probe involved a single session while baseline was conducted in two sessions, as it was found that no one demonstrated teaching integrity greater than 20% DTT components completed correctly. This way, all participants went through the subsequent stages of the research.

BST Training with Immediate Performance Feedback. During this stage, the four BST components (didactic instruction, modeling, role-play, and performance feedback) were administered to the participants. Didactic instruction consisted of classes on how to teach the four repertoires selected for training (following instructions, LRFFC, intraverbal and tact). Power point slides were organized to represent trials involving correct responses, incorrect responses (or no response emitted during the allowed time), reinforcement and correction procedures to be applied. The experimenter explained the content of all slides and clarified possible doubts from the participants. Slides on types of disruptive behaviors according to function and recommended management were also created and explained, considering that one of the DTT components from this study concerned the management of undesirable behaviors appropriately. Didactic instruction lasted 30 minutes on average for each participant and it was conducted just once in this stage.

After didactic instruction, modeling was administered by the experimenter. As explained before, for six participants, modeling involved in-person interactions between experimenter and confederate simulating interactions between interventionist and child with ASD during the provision of DTT. For the remaining four participants, modeling represented the same type of interactions, but through videos/recordings. In both cases, this part of training concerned the presentation of 12 DTT trials for observation by the participants. These trials included the emission of correct responses, incorrect responses and failure to respond during the allowed time by the learner confederate and the type of differential consequence administered by the interventionist/experimenter for each case (reinforcement or correction procedure). In the case of video modeling more specifically, it is important to say that the videos, involving simulations of interactions between experimenter and confederate in teaching repertoires through DTT, were recorded in the university laboratory where data collection was carried out. A tablet was used to record videos to be shown to participants later.

Each video lasted from 1 minute to 1 minute and 30s and represented one of the 12 DTT trials to be observed by a given psychology student participant. The simulated trials involved the teaching of the four repertoires (following instructions, LRFFC, intraverbal and tact) that each participant would have to learn how to teach accurately later during the role-play portion of the BST. Since the 12 simulated trials concerned the four mentioned repertoires, for each of them, in four trials, the confederate emitted a correct response. In four trials, an incorrect response was emitted, and, in four trials, no response was emitted during the allowed time. These trials were shown in a randomized order. Occasionally, the videos showed the emission of minor atypical behaviors that required management. Regarding the case of the participants assigned to BST training with in-person modeling, live demonstrations of the 12 teaching trials concerning the four repertoires, between experimenter and confederate took place. The confederate followed a script with pre-determined actions, so that the simulation could also involve the emission of four correct responses, four incorrect responses and four occasions without the emission of response. Occasionally, minor atypical behaviors that required management were performed.

During the didactic instruction and modeling/video modeling portions of the BST training no data collection on teaching integrity by the participants was taken. Didactic instruction and modeling/video modeling were conducted just once during this stage of the research. Following these conditions, the role-play and performance feedback portions of training were carried out. Data collection in training was conducted solely during role-play with feedback. In this study, it was not intended to investigate the effects of each BST component separately. In a recent meta-analysis research, it was discussed that the best way to reduce integrity errors, when implementing ABA-based interventions to learners with ASD, is through a more comprehensive training package involving the participation of the behavior analyst trainer and the use of all BST components together [

26]. Based on this, in the current research, in-person modeling or video modeling (depending on the participant) were not analyzed separately concerning the effectiveness and efficiency in producing improvements in teaching integrity. Rather, the analysis considered each modeling component as part of a more comprehensive training package, also involving didactic instruction and provision of performance feedback.

During role-play, the experimenter asked each participant to administer 12 trials per session to teach the four defined skills to the confederate, who followed a script with pre-determined actions along the trials (emission of correct, incorrect response and no response, besides exhibiting occasionally minor atypical behaviors that required management). During this process, after each trial, the experimenter provided feedback on participant’s performance. In this sense, praise was delivered contingent to correct implementation of DTT components. Conversely, the incorrect implementation of components during a trial resulted in the experimenter pointing out procedural errors and explaining what had to be done instead. Thereafter, for a participant assigned to BST training with in-person modeling, the experimenter demonstrated how to perform the component (s) correctly by rehearsing with the confederate. For a participant assigned to BST training with video modeling, the experimenter showed a video (involving the experimenter rehearsing with the confederate) representing the correct implementation of the component (s). Then, in each case, the participant should administer the trial again to the confederate. The criterion for ending this stage of the study, for all ten participants, consisted of a session in which at least 90% of the DTT components were implemented correctly.

BST Training with Delayed Performance Feedback. This stage was similar to the previous one and the participants had to teach the same four repertoires previously described to the confederate (during role-play, following the components of didactic instruction and in-person modeling or video modeling that were both administered once as in the previous stage). Furthermore, the same type of performance feedback, considering correct and incorrect implementation of DTT components, was provided by the experimenter. However, feedback was presented only after all 12 trials administered per role-play session. If, at the end of the process per session, two or more DTT component errors were recorded, a demonstration of the correct way to implement them (in-person or through videos depending on the participant) was carried out by the experimenter. The criterion for ending this stage was the same as the previous one.

Generalization probe involving Children with ASD. This was similar to the first stage of the research. Each participant had to teach four repertoires without receiving performance feedback from the experimenter. However, the teaching was carried out directly to a child with ASD as a way of measuring generalization of BST training involving a confederate. Furthermore, new repertoires not involved in training were taught. As previously stated, they corresponded to motor imitation, sitting still, pairing identical pictures and mand. Before the probe session, the participants were allowed to review the manual with instructions on how to teach the new repertoire in this stage [

25].

2.8 Ethical Procedures

This investigation was evaluated and approved by the ethics committee in research with humans from CEUMA University (authorization 3.584.016). All university students, the children with ASD and those responsible for them signed an informed consent form. Personal information was confidential. The study could be interrupted by the participants if they wished without any harm.

3. Results

Below, the percentages of DTT components completed correctly, throughout all research stages, are shown for all pairs of participants. Firstly, data from the pairs to whom BST training involved in-person modeling (P1 and P2; P3 and P4; P5 and P6) are revealed. Next, data from the pairs to whom BST training involved video modeling (P7 and P8; P9 and P10) are displayed.

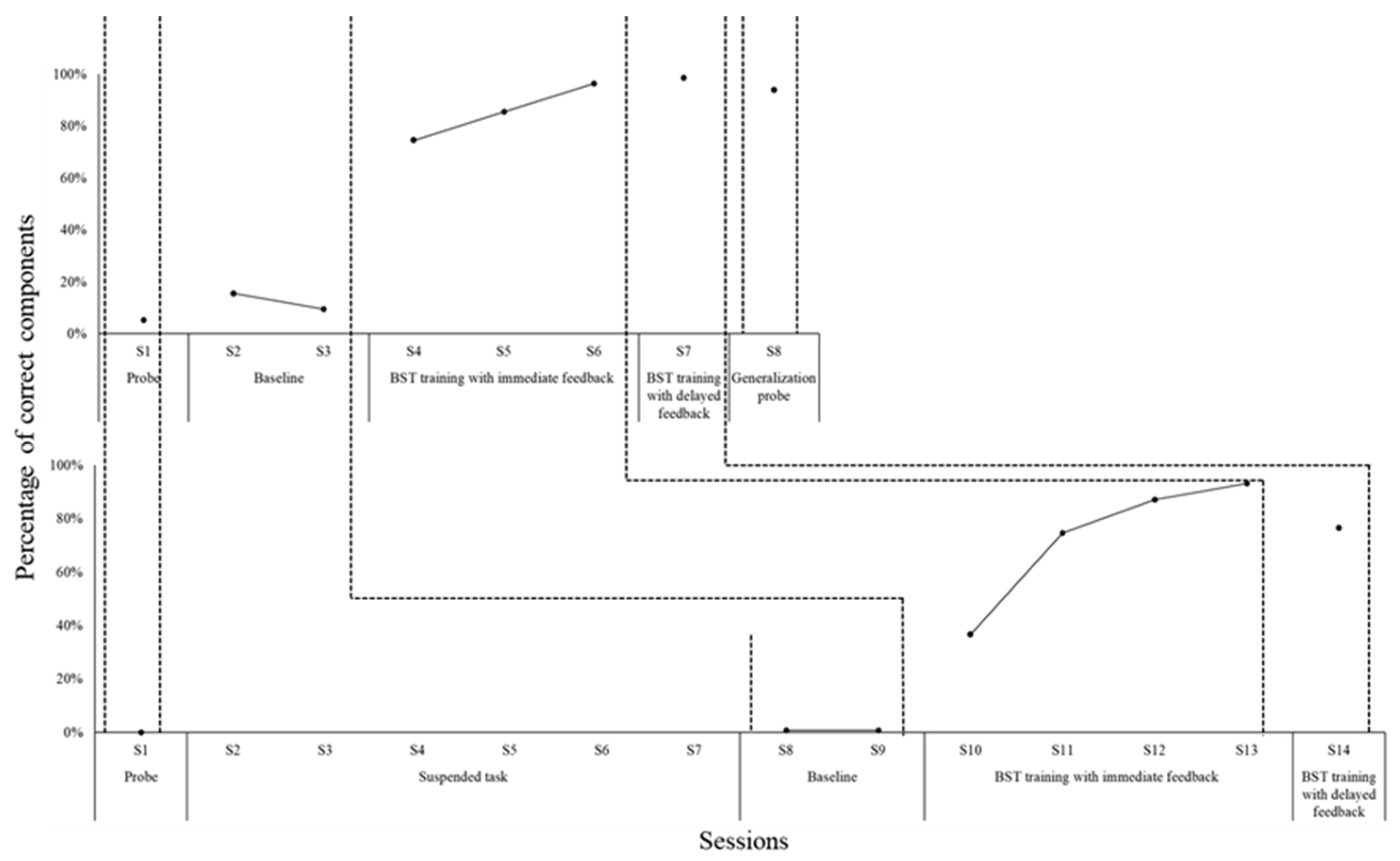

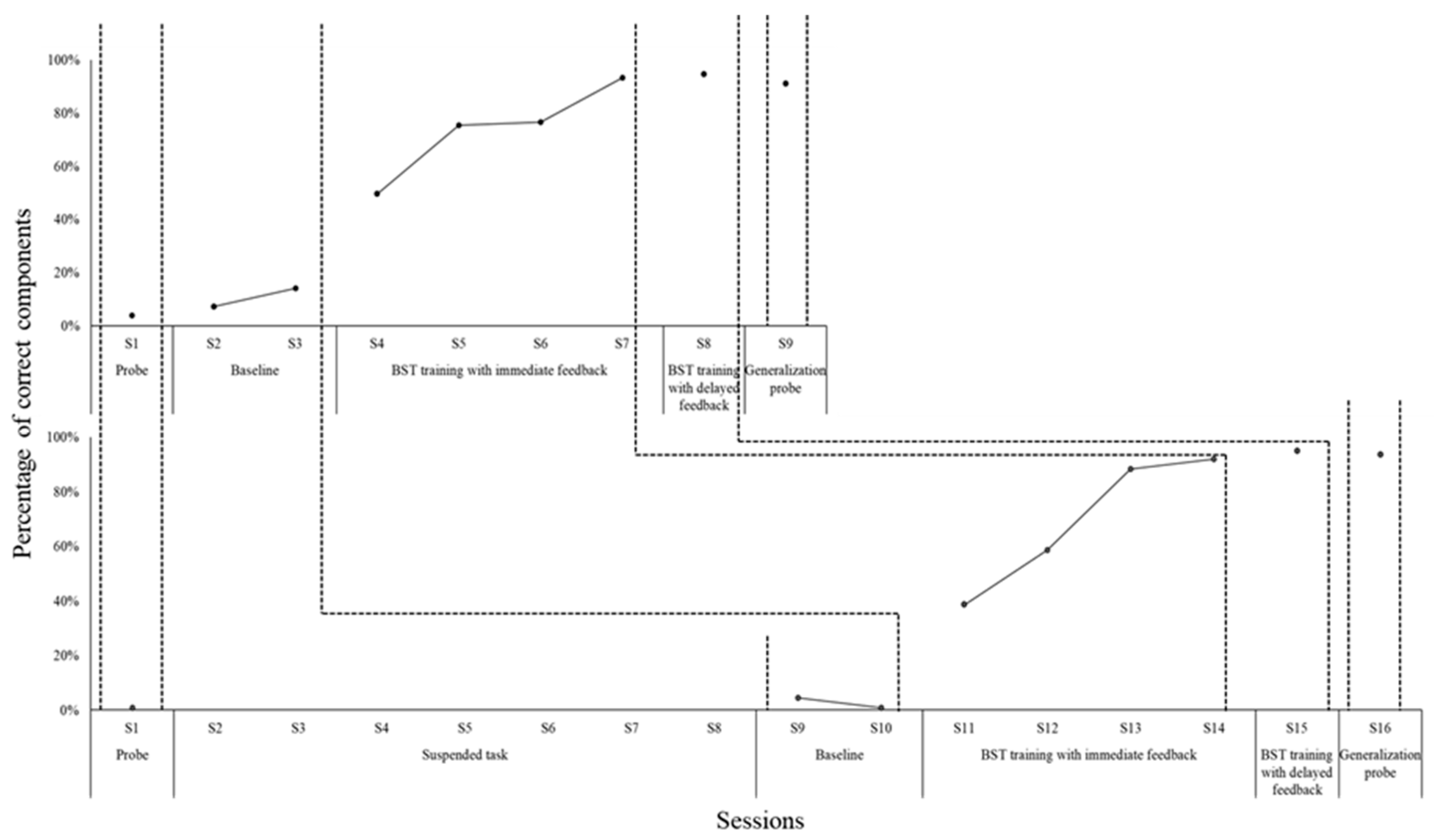

Figure 1 represents the data from the pair P1 and P2.

Note. The upper graph represents data from P1 and, the lower one, from P2. The graphs represent the percentage of DTT components completed correctly (teaching integrity) by the participants while teaching repertoires to a confederate or child with ASD along the research stages (probe, baseline, BST training with immediate feedback, BST training with delayed feedback, generalization probe). Interactions with a child with ASD only occurred under the generalization probe condition.

As can be seen in

Figure 1, P1, at the end of baseline showed teaching integrity of 9.52% DTT components completed correctly (S3 session). In the case of P2, the teaching integrity corresponded to 0.77% (S9). When BST training with immediate feedback began, P1 needed three sessions to meet the criterion (96.26% integrity in S6) and P2 needed four (93.20% integrity in S13). Only one session was necessary during BST training with delayed feedback for P1 (98.39% integrity in S7). In the case of P2, only one session was run (76.38% integrity in S14), as the participant quit the research for health reasons. Finally, the generalization probe session involving a child with ASD as learner instead of a confederate (only for P1) resulted in a teaching integrity of 93.72% in S8. Regarding data collection days, P1’s training lasted 280 minutes and P2’s training lasted 260 minutes (P2, however, did not complete all stages of the research).

The progression from minimal baseline performance to high teaching integrity across a short number of sessions suggests that structured, feedback-guided learning environments can facilitate the consolidation of complex teaching routines. This type of rapid and stable performance acquisition is consistent with findings that repeated engagement in structured tasks supports enduring adaptations in task-related cognitive processes, potentially enhancing efficiency and precision in similar contexts.

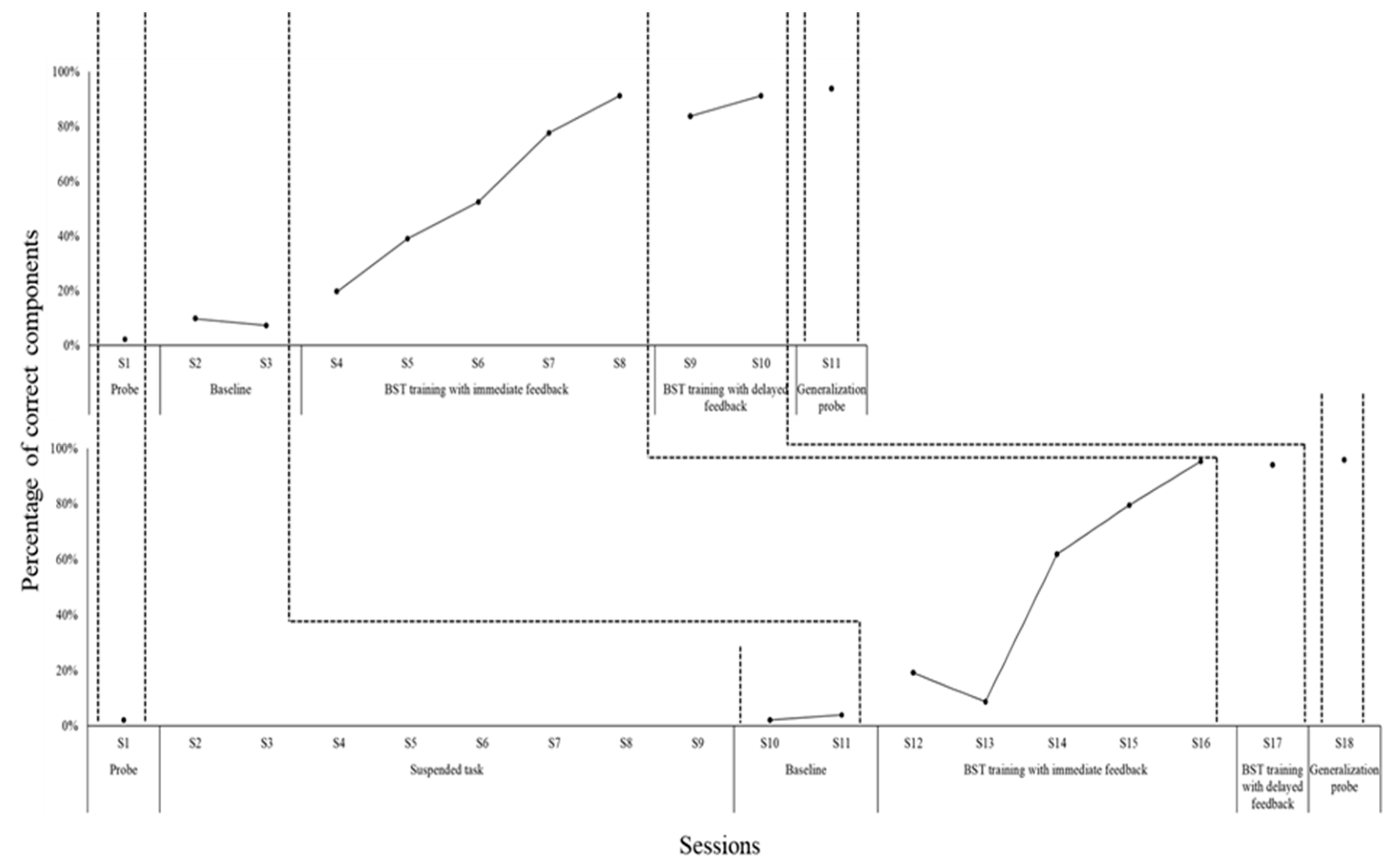

Figure 2 shows the data from the pair P3 and P4.

Note. The upper graph represents data from P3 and, the lower one, from P4. The graphs represent the percentage of DTT components completed correctly (teaching integrity) by the participants while teaching repertoires to a confederate or child with ASD along the research stages (probe, baseline, BST training with immediate feedback, BST training with delayed feedback, generalization probe). Interactions with a child with ASD only occurred under the generalization probe condition.

According to

Figure 2, by the end of baseline, P3 and P4 demonstrated teaching integrity of 7.26% (S3) and 3.96% (S11), respectively. During BST training with immediate feedback, the learning criterion was reached in five sessions by P3 (91.26% integrity in S8) and P4 (95.24% integrity in S16). During BST training with delayed feedback, two sessions were needed for P3 (91.23% integrity in S10) and only one for P4 (93.88% integrity in S17). Finally, the probe involving a child with ASD showed generalization of a high level of teaching integrity for both P3 (93.82% integrity in S11) and P4 (95.74% integrity in S18). Training P3 and P4 lasted 400 and 380 minutes, respectively.

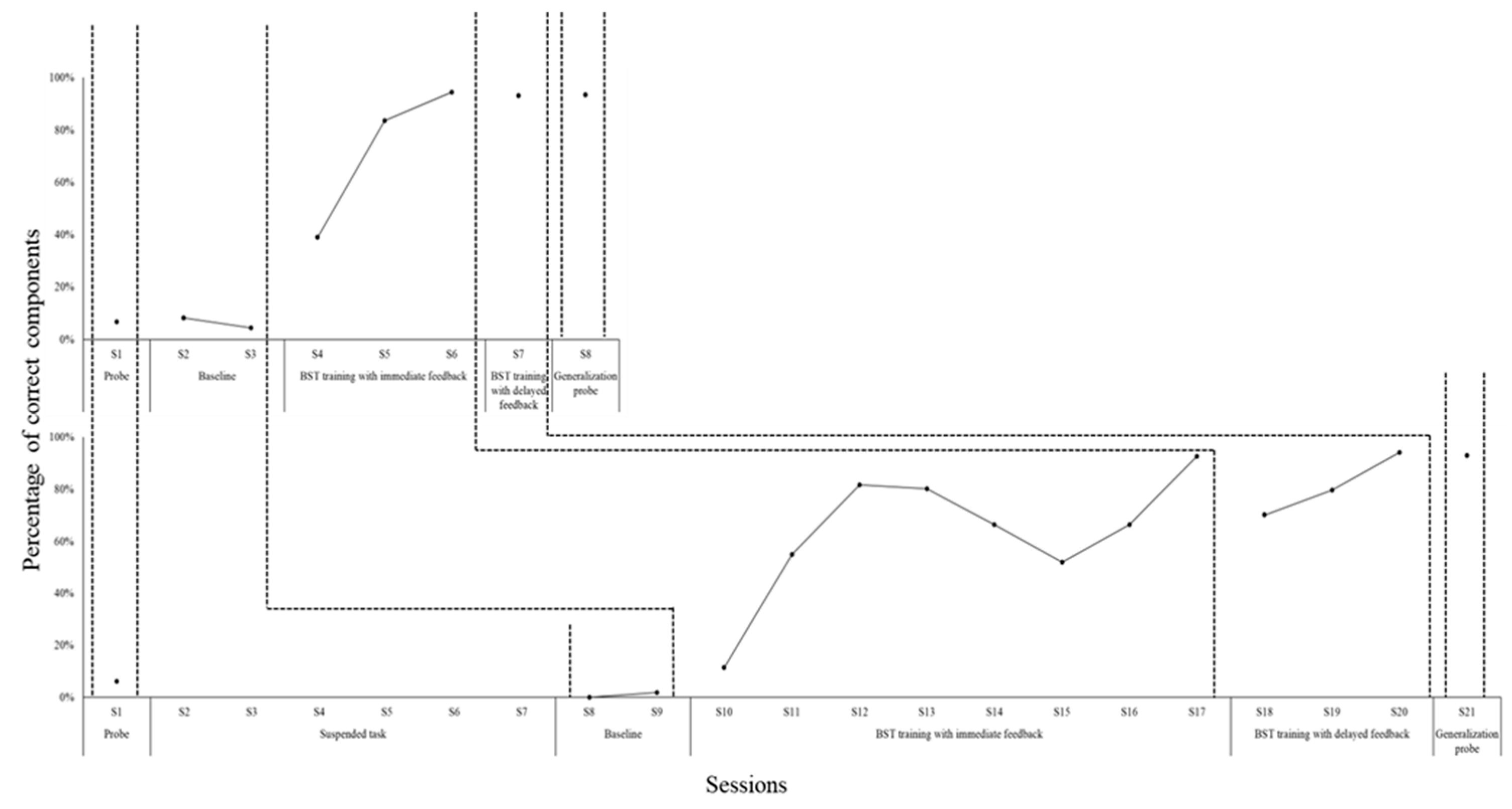

Figure 3 presents data from the pair P5 and P6.

Note. The upper graph represents data from P5 and, the lower one, from P6. The graphs represent the percentage of DTT components completed correctly (teaching integrity) by the participants while teaching repertoires to a confederate or child with ASD along the research stages (probe, baseline, BST training with immediate feedback, BST training with delayed feedback, generalization probe). Interactions with a child with ASD only occurred under the generalization probe condition.

Figure 3 reveals that, by the end of baseline, P5 and P6 demonstrated teaching integrity of 4.48% (S3) and 1.72% (S9), respectively. The criterion in BST training with immediate feedback was met by P5 after three sessions (94.34% integrity in S6) and, in the case of P6, eight sessions (91.84% integrity in S17). During BST training with delayed feedback, P5 needed only one session (93.02% integrity in S7) and P6 needed three (96% integrity in S20). The probe session with a child with ASD indicated generalization of a high level of teaching integrity for both P5 (93.30% integrity in S8) and P6 (91.23% integrity in S21). P5’s training lasted 280 minutes and P6’s training lasted 570 minutes.

Although both participants ultimately achieved high performance, the difference in the number of sessions and duration required to reach criterion suggests interindividual variability in the pace at which structured behavioral routines are internalized. This observation aligns with evidence that experience-dependent skill acquisition is modulated by factors such as prior learning history, cognitive processing strategies, and sensitivity to feedback, which may influence how efficiently individuals adapt to systematic teaching protocols.

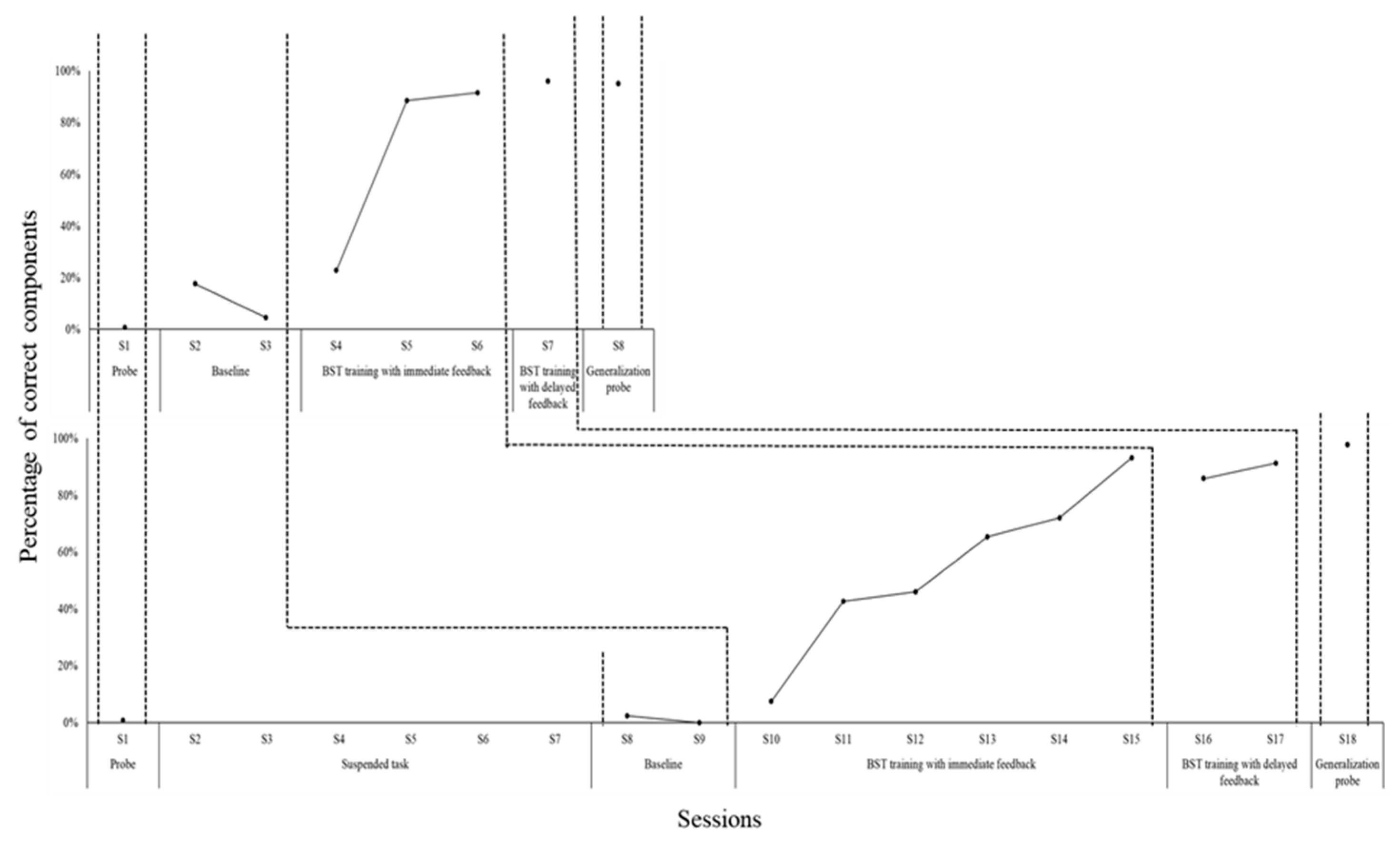

Figure 4 presents data from P7 and P8.

Note. The upper graph represents data from P7 and, the lower one, from P8. The graphs represent the percentage of DTT components completed correctly (teaching integrity) by the participants while teaching repertoires to a confederate or child with ASD along the research stages (probe, baseline, BST training with immediate feedback, BST training with delayed feedback, generalization probe). Interactions with a child with ASD only occurred under the generalization probe condition.

As can be seen in

Figure 4, P7 and P8 showed teaching integrity of 4.51% (S3) and 0% (S9), respectively, until the end of baseline. In BST training with immediate feedback, to achieve the learning criteria, P7 needed three sessions (91.59% integrity in S6) and P8 needed six (93.20% integrity in S15). During BST training with delayed feedback, P7 and P8 required one (95.90% integrity in S7) and two sessions (91.26% integrity in S17), respectively. Finally, the probe with a child with ASD revealed generalization of a high level of teaching integrity for P7 (95.04% integrity in S8) and P8 (97.73% integrity in S18). P7’s training lasted 280 minutes and P8’s training lasted 450 minutes.

Despite beginning with similar baseline performance, P7 and P8 progressed at different rates throughout training, requiring a distinct number of sessions to meet the performance criteria. These differences may reflect individual variations in processing and integrating task-related demands, which are known to influence how efficiently instructional routines are internalized. Structured feedback and repetitive engagement appear to support the gradual refinement of behavioral repertoires, even when initial responsiveness varies.

Figure 5 shows data from P9 and P10.

Note. The upper graph represents data from P9 and, the lower one, from P10. The graphs represent the percentage of DTT components completed correctly (teaching integrity) by the participants while teaching repertoires to a confederate or child with ASD along the research stages (probe, baseline, BST training with immediate feedback, BST training with delayed feedback, generalization probe). Interactions with a child with ASD only occurred under the generalization probe condition.

According to

Figure 5, P9 and P10 demonstrated teaching integrity of 14.05% (S3) and 0.79% (S10), respectively, until the end of baseline. During BST training with immediate feedback, the criterion was met across four sessions for P9 (93.33% integrity in S7) and P10 (91.89% integrity in S14). During BST training with delayed feedback, only one session was needed for P9 (94.66% integrity in S8) and P10 (94.92% integrity in S15). Finally, there was generalization to a high level of teaching integrity during the interactions with a child with ASD, considering both cases of P9 (91.11% integrity in S9) and P10 (93.53% integrity in S16). The training for both P9 and P10 lasted 330 minutes.

The rapid and stable gains observed in both participants may suggest a particularly efficient assimilation of structured teaching procedures. This pattern of accelerated acquisition aligns with evidence that highly structured, feedback-driven learning contexts can support swift consolidation of procedural sequences, even in individuals with minimal prior experience. Such findings underscore the potential of well-designed instructional protocols to promote reliable skill development across diverse learner profiles.

4. Discussion

In this study, BST was an effective tool, as all ten participants acquired the ability to teach nonverbal and verbal repertoires to a confederate with high teaching integrity. In other words, everyone correctly implemented over 90% DTT components along training stages with immediate and delayed performance feedback. This data is in line with previous literature on training university students and professionals, which indicated the effectiveness and efficiency of the BST components [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

24].

From a broader cognitive perspective, the structured nature of BST with its sequence of instruction, modeling, rehearsal, and feedback may serve not only as a behavioral intervention strategy but also as a scaffold for the formation and consolidation of procedural cognitive routines. These routines, once stabilized, are potentially associated with experience-dependent plastic changes in task-relevant circuits, especially when practice is frequent and feedback is timely [

27].

BST training in this investigation also resulted in the generalization of high teaching integrity by most of the participants (except P2, who quit earlier for health issues) while teaching four new repertoires to children with ASD. Six psychology students were subjected to a BST training package in which the modeling component involved in-person interactions (experimenter and confederate playing roles of interventionist and child with ASD, respectively, simulating teaching repertoires through DTT). Another four psychology students were participants in a BST training in which the modeling component involved the use of videos (the experimenter showed videos of two actors playing the roles of interventionist and child, simulating teaching interactions with DTT). The average duration of training for the two groups of participants was similar, as the six participants in the BST training with in-person modeling completed the training process in 362 minutes (approximately 6 hours) on average and the four in the BST training with video modeling completed the training process in 348 minutes on average (approximately 5,8 hours). The consistent improvement across participants reinforces findings from neuroscience suggesting that structured behavioral engagement can shape task-specific skills in adults through reinforcement-dependent adaptation mechanisms. Such mechanisms may reflect dynamic remodeling of neural representations supporting attention, executive planning, and stimulus-response control [

6,

27].

Training took a longer time compared to another research in which instructional video modeling without feedback sufficiently resulted in significant improvements in teaching integrity levels by mothers of children with ASD, and the process lasted 3 hours on average [

18]. However, this one focused on improving the accurate teaching of only two repertoires in ten trials overall. In the current study, BST training was carried out in two stages whereas, in the previously mentioned investigation, only one stage (instructional video modeling without feedback) was needed [

18]. Anyway, in a similar study, the training process took 5 hours on average [

19]. Regarding another research in which an alternating treatments design was used to compare BST training with in-person modeling to BST training with video modeling, 3 hours and 20 minutes on average were sufficient to train psychology students to implement DTT accurately in two stages of BST involving immediate and delayed feedback [

13]. However, in this case, no probe session to assess generalization of accurate teaching of repertoires to children with ASD was conducted.

In general, this study was effective and efficient for all participants involved (even though there were variations in training durations from different studies). Regarding the recommendation that video modeling reaches full potential as part of more comprehensive training involving presence-based interactions with the trainer [

18], the participants, who were specially assigned to BST training with video modeling in the current investigation, had intensive interactions with the experimenter/trainer through didactic instruction and performance feedback. This layered training structure where modeling through video is complemented by active, socially mediated feedback may enhance procedural learning by engaging reinforcement-sensitive neural systems that benefit from both observational encoding and corrective contingencies. Neuroscientific literature suggests that such contexts are particularly effective in promoting durable learning through experience-dependent neural modulation, especially when learners alternate between passive observation and active engagement [

27].

In previous study in which six psychology students as participants experienced both types of BST training with in-person modeling and video modeling, the results suggested that both types of training were similarly efficient in terms of the average training time. However, the experimental design used was intra-participant with alternating treatments [

13]. As already discussed in the literature, this type of design involves a disadvantage, which is the fact that there may be interference effects on a dependent variable [

17]. In this sense, the two types of BST training may have influenced each other in producing the ability to teach nonverbal and verbal repertoires via DTT appropriately. This makes comparisons regarding efficiency difficult. Unlike the previous investigation [

13], the current study did not have the purpose of comparing the two types of BST, but to analyze the effectiveness and efficiency of each type of training across different participants in the context of the same research, and without the possibility of interference effects of one training over the other.

To accomplish this purpose, the type of experimental design used was of multiple probes across different participants (each one of two groups of participants underwent only one type of BST training), which eliminated the possibility of an interference effect between treatments [

17]. No comparisons were made between the effects of the two types of training because each participant experienced only one of them. However, an analysis of effectiveness and efficiency, as said before, was done for each type of training. Overall, teaching integrity was low in baseline across participants (below 20% DTT components completed correctly). They had similar characteristics in terms of not having prior experience with ABA to ASD, which was also an aspect of previous studies [11-13]. In some of them, teaching integrity was relatively high in baseline. In one case, participants watched videos demonstrating DTT components in baseline, which could be a possible reason for high integrity before training [

11]. Moreover, in another case, the participants were psychology interns who had previous access to ABA interventions to children with ASD as observers, which may also have been an interfering variable, influencing high teaching integrity in baseline [

12].

In this investigation, although the average duration of training was similar between the groups of participants, the case with video modeling seemed to represent a good cost-benefit, because it required less involvement from behavior analysts in the training process of the participants. This data corroborates the argument from previous literature that the BST package with a video modeling component may be a viable and efficient alternative to BST with an in-person modeling component [

13].

The literature on staff training discusses other possible alternatives to an in-person BST besides the instructional video modeling with little or no performance feedback mentioned earlier [

18,

19,

20,

21]. In the literature, for example, investigations were already carried out to analyze possible effects of a computerized tutorial in reducing costs in the implementation of training and less participation of the behavior analysist trainer. However, it was argued that greater participation by the trainer, with the provision of performance feedback, enhances the effects of training [

28]. A recent study, [

29], measured the training efficiency of university students solely through a self-instruction manual, translated and adapted to Portuguese from another manual in English [

30]. This growing interest in scalable, low-contact training formats raises important questions about the depth and retention of procedural learning. Evidence suggests that while exposure to structured information may activate basic learning pathways, the absence of interactive, feedback-rich environments may limit the degree of neural adaptation and task automatization. In contrast, training formats that combine explicit instruction with guided feedback tend to induce more robust consolidation of learning, likely reflecting engagement of broader neuroplastic mechanisms tied to task complexity and social contingency [

27].

In the recent study using a manual, four participants were exposed to a self-instructional manual comprising 85 pages organized into 11 chapters. The content covered foundational topics such as autism spectrum disorder, principles of applied behavior analysis (ABA), discrete trial teaching (DTT) procedures, antecedent functions, and strategies for prompt fading. The training included guided study questions and simulated teaching sessions in which participants implemented DTT with a confederate acting as a child with ASD. Although improvements in teaching integrity were observed across participants, the gains were modest and insufficient to meet implementation fidelity standards. These findings led the authors to conclude that self-instructional formats, while useful, are more effective when integrated into broader training frameworks that include active supervision and performance feedback [

29]. Such results are consistent with the broader evidence base suggesting that passive learning alone, particularly when lacking direct social reinforcement and corrective input, may not sufficiently engage the cognitive and behavioral systems required for procedural fluency. Conversely, training models like BST, which integrate instruction, modeling, rehearsal, and feedback, appear to promote deeper encoding and adaptive generalization through repeated interaction and contingency-based guidance [

18,

27,

28,

29].

Regarding BST, a limitation pointed out in previous studies [

10,

12,

13,

14,

23,

24] was that it was not possible to determine which components were needed to increase participants’ teaching integrity. The effects of each component (didactic instruction, modeling, role play and performance feedback) on integrity were not assessed separately. This was also the case with the current investigation. However, a recent meta-analysis on studies using single case research designs indicated that greater levels of teaching integrity are produced when the components of BST are used together. The authors quantified the impact of BST training on different individuals while teaching repertoires via DTT. It was found that when the four components of BST are employed together, they are statistically significant, considering that the trained staff demonstrated an average teaching integrity of 96.06% DTT components implemented correctly [

26].

Data from the meta-analysis strengthens the recommendation of using BST as a set of effective training strategies [

26]. The present research, which assessed the effects of BST components together, produced data that also supports this recommendation. However, the use of a video modeling component, instead of in-person modeling, may represent a viable and cost-effective alternative with less participation of the behavior analyst trainer, which is also in line with previous literature, which explored such an alternative for training university students [

13,

24].

Some limitations deserve note in the current research. Maintenance of teaching integrity after BST training was not evaluated. It is important that future studies analyze maintenance levels of teaching integrity after BST training with in-person modeling and with video modeling assigned to different participants. Also, this study did not conduct an analysis of DTT component errors by the participants during the research stages. Future investigations should take this into consideration, as error analysis may help in the process of defining possible adjustments to BST training, improving efficiency. Another limitation was that no initial probe and baseline sessions were conducted having children with ASD as learners (the participants only taught a confederate during this stage). Interactions with children with ASD only occurred during a generalization probe session after BST training. And the impact of training on children’s skill acquisition was not systematically measured as in previous research [

9,

12,

13]. Future studies should consider assessing participants’ maintenance of teaching integrity and skill acquisition by children with ASD along several DTT sessions (after participant training, involved either in BST with in-person modeling or in BST with video modeling, is finished).

Another limitation needs to be emphasized: in this research, the variation of multiple baseline design used, multiple probe design [

22], involved the implementation of an initial probe session followed by true baseline sessions to determine initial levels of teaching integrity. Baseline condition was short. It involved solely two datapoints per participant, that is, two sessions. Ideally, a longer baseline with more sessions should be conducted until stability. The literature suggests the importance of at least three data points across research conditions to facilitate analysis of level, trend, and variability [

31]. In the current study, regarding the conditions with BST training, the case with delayed feedback involved less of three datapoints/sessions for most of the participants. However, the previous BST training condition differed only in that feedback delivery was immediate.

It certainly influenced the following condition, facilitating achievement of the learning criterion. And BST training with immediate feedback involved more than three data points/sessions for most of the participants. Although the data suggests some deficiency in the rigor of the design used, teaching integrity after BST for all participants indicates a demonstration of a functional relation because it was above 90% DTT components completed correctly. During initial probe and baseline sessions, teaching integrity was very low (below 20%). For each pair of participants, improvements were only noticed for each person involved after BST training was implemented.

In another study, the effects of BST training were assessed on the implementation of naturalistic behavioral interventions by five technicians who had prior experience working at an early intervention center. The learners in this investigation were three boys with ASD aged 2 to 4 years. All technicians demonstrated improvement in positive naturalistic behavioral skills (e.g., expression of approval and labeled praise when a learner emits appropriate behavior) (high teaching integrity) while teaching learners with ASD. High teaching integrity was also maintained over time and generalization was also noticed during the teaching of new learners. Among limitations pointed out by the authors, they discussed that few baseline sessions (one or two, only) were implemented before BST training. Nevertheless, they also stated that participants’ levels of teaching integrity in baseline were consistent with clinical observations before the research [

32]. In the current investigation with psychology students to whom baseline was also short, as mentioned before, the students were all unfamiliar with ASD and ABA procedures to address deficits in skills and problem behavior management. They never worked with atypical development before. All of this was determined before the onset of the study. It was previously hypothesized that teaching integrity would be low, and this is precisely what was demonstrated during the initial probe and baseline sessions. Anyway, it is acknowledged the importance of addressing the issue in future investigations by conducting at least three sessions per condition for the sake of necessary scientific rigor in research using single case designs [

31].

Another important limitation, still regarding the design used, needs to be emphasized. Some studies from literature used what is known as an imperfect implementation of a multiple baseline design or multiple probe design as a variation. By imperfect, it means that the number of baseline sessions across participants were similar, and a more rigorous experimental design in future studies is important to increase internal and external validity of data. In other words, it is important that the baseline condition comprises different number of sessions/data points across participants [

17]. However, imperfect designs have been used in research over the years. In a previous study, mothers were trained to implement DTT accurately to their children with ASD using a multiple baseline design. The number of baseline sessions across participants was similar, being either four or five [

19].

In another context, a series of studies used an imperfect multiple probe design. In one case psychology students were trained through BST with in-person modeling to implement DTT to a confederate and assessed generalization with children with ASD. Baseline sessions across participants were similar, being either two or three [

12]. In another case, BST with in-person modeling and BST with video modeling were compared in training psychology students to implement DTT through an intraparticipant alternating treatments design. This one was embedded into an imperfect multiple probe design across participants. Baseline sessions across participants were similar, being three [

13]. A third case comprised the use of remote (internet) BST with video modeling to train parents on implementing DTT to teach academic repertoires to their child with ASD. It was used an imperfect multiple probe design and baseline sessions across participants were also similar, being three [

23]. Finally, there was also a study in which behavior technicians were trained to implement naturalistic behavioral interventions to children with ASD. They used an imperfect multiple probe design across participants and baseline sessions were also similar across participants, being either one or three [

32].

Recent research has been defining more rigorous experimental design as an alternative to an imperfect multiple probe design. A recent investigation, for example, used a non-concurrent multiple baseline design to train pedagogy students (through BST with video modeling) to accurately teach narrative story retelling and answering comprehension questions to confederate and children with ASD. Across participants, the baseline condition involved a different number of sessions [

24]. A final limitation in the current study also needs to be pointed out. The design was a two-tier multiple probe design across pairs of participants. As it was said before, this was intentionally defined to speed up the training process because the university laboratory where the study was conducted had a great demand for new students/interns who could carry out interventions (under supervision) with the many children with ASD served in this context. The research team is aware of the importance of defining more than two tiers in future investigations for a better demonstration of experimental control. Anyway, several previous studies involving an imperfect two-tier multiple probe design (or imperfect two-tier multiple baseline design) across pairs of participants, besides the current investigation, were published in behavioral analytic journals [

12,

23], psychology journal [

13] and special education journal [

24].