Submitted:

11 October 2025

Posted:

15 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

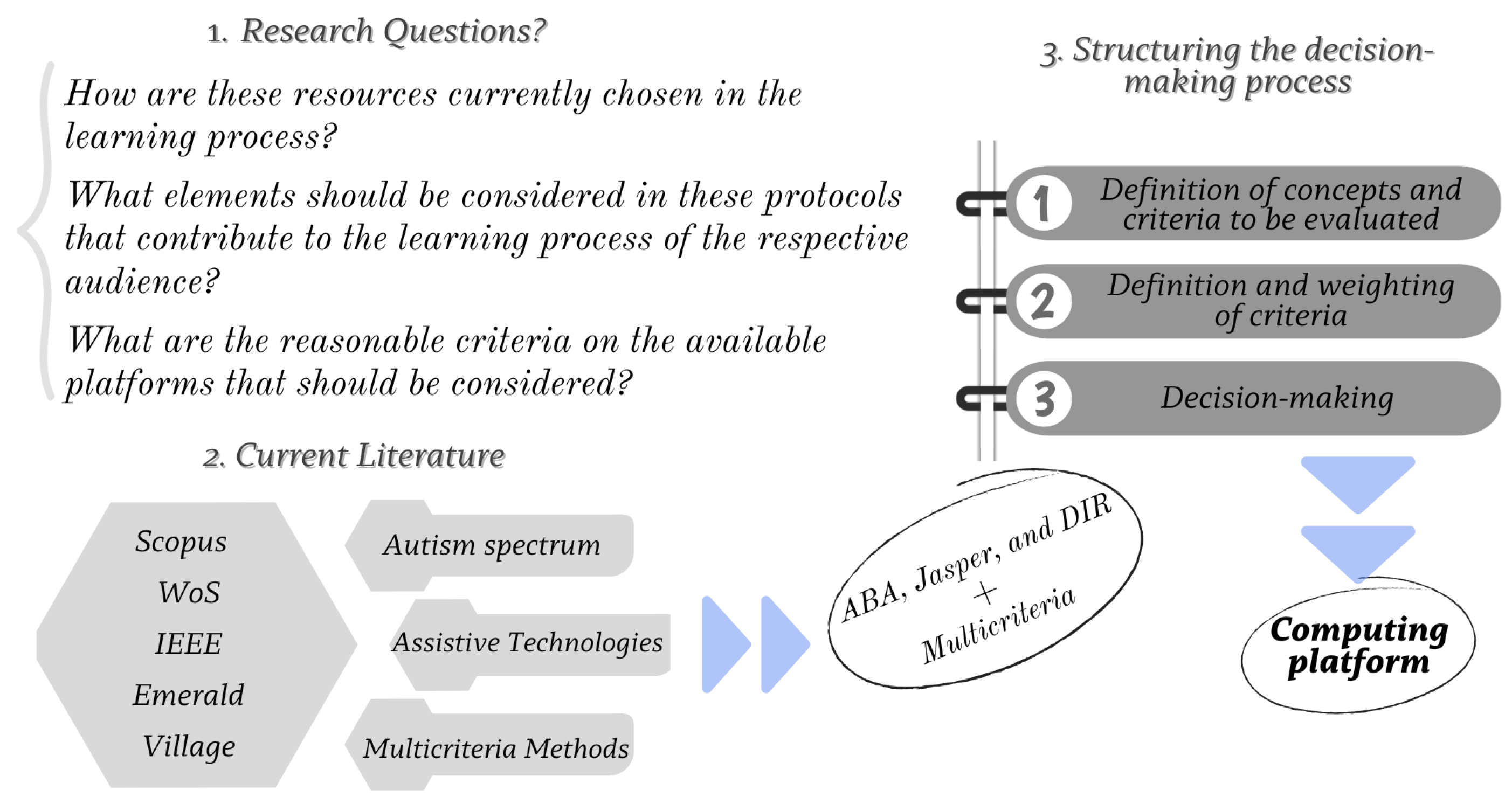

1. Introduction

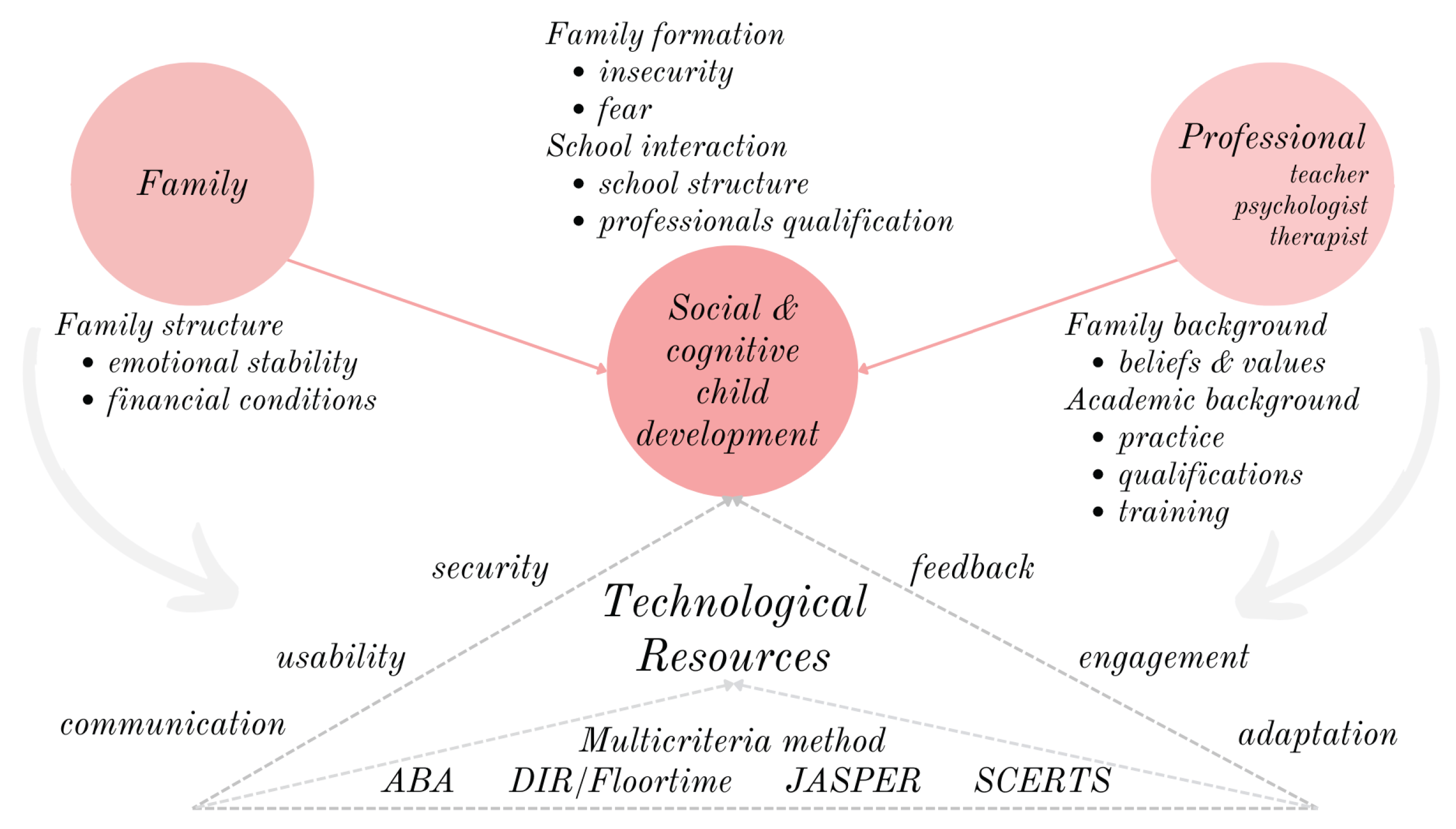

- How are these resources currently chosen in the learning process? AI-based assistive technologies support the adaptive functioning of individuals with neurodevelopmental conditions in everyday scenarios. When choosing technological resources for the learning process [18]. AI-based assistive devices are selected based on their effectiveness in personalising support to individual needs and are often applied to stimulate social skills, communication, and daily living capabilities [19]. Thus, criteria such as accessibility, applicability in educational and domestic environments, and the ability to adapt the device to the specific demands of the user. [20] this choice should be made using e-learning recommendation systems, which involve criteria such as individual interests, specific needs, and user preferences. These platforms use collaborative filters and personalisation techniques to adapt the content to the child’s characteristics, promoting more accessible and practical learning. The choice of technological resources in special education teaching should be based on the personalisation of learning, using assistive technologies and adaptive platforms to meet individual needs [21]. In this analytical composition, it is essential to consider accessibility criteria, support for differentiated learning, and teacher training.

- What elements should be considered in these protocols that contribute to the learning process of the respective audience? Protocols for the adoption of educational technologies must consider criteria such as accessibility, applicability in different contexts (school, home and social) and adaptation to the specific needs of their users. Furthermore, it is vital to evaluate the effectiveness and usefulness of these devices in everyday life, ensuring their consistent and beneficial use [18]. For an educational resource aimed at children with ASD to be effective, it is essential to take into account sensory engagement, personalised teaching and integration with pedagogical practices [22]. The inclusion of multimodal elements, such as visual and auditory stimuli, as well as adaptation of the learning pace, contributes to improving the educational experience of these students [23]. Considering this perspective, educational protocols aimed at people with ASD must encompass aspects such as accessibility, adaptation to the user profile, personalised teaching and use of assistive technologies. Furthermore, it is essential to assess students’ visual engagement to ensure that technological resources are used effectively, promoting improvements in interaction and cognitive development [20]. Teachers play a crucial role in building interactions. They can foster collaboration by facilitating turn-taking, allowing students to build a mutual relationship rather than just responding to the teacher [6]. Fostering these social interactions allows students to express collaboration. In this way, they develop social competence in navigating group dynamics and enhance their educational experience.

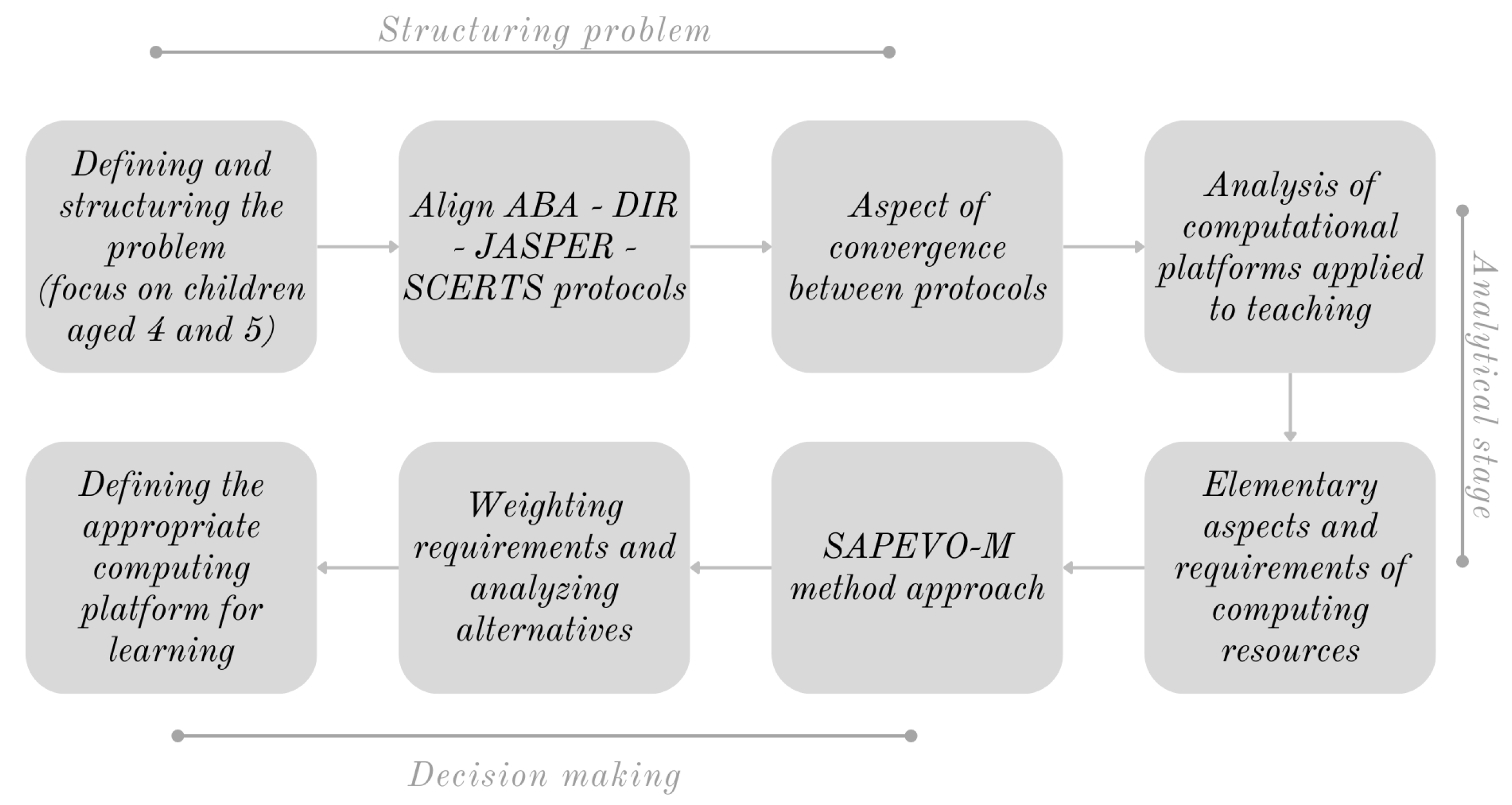

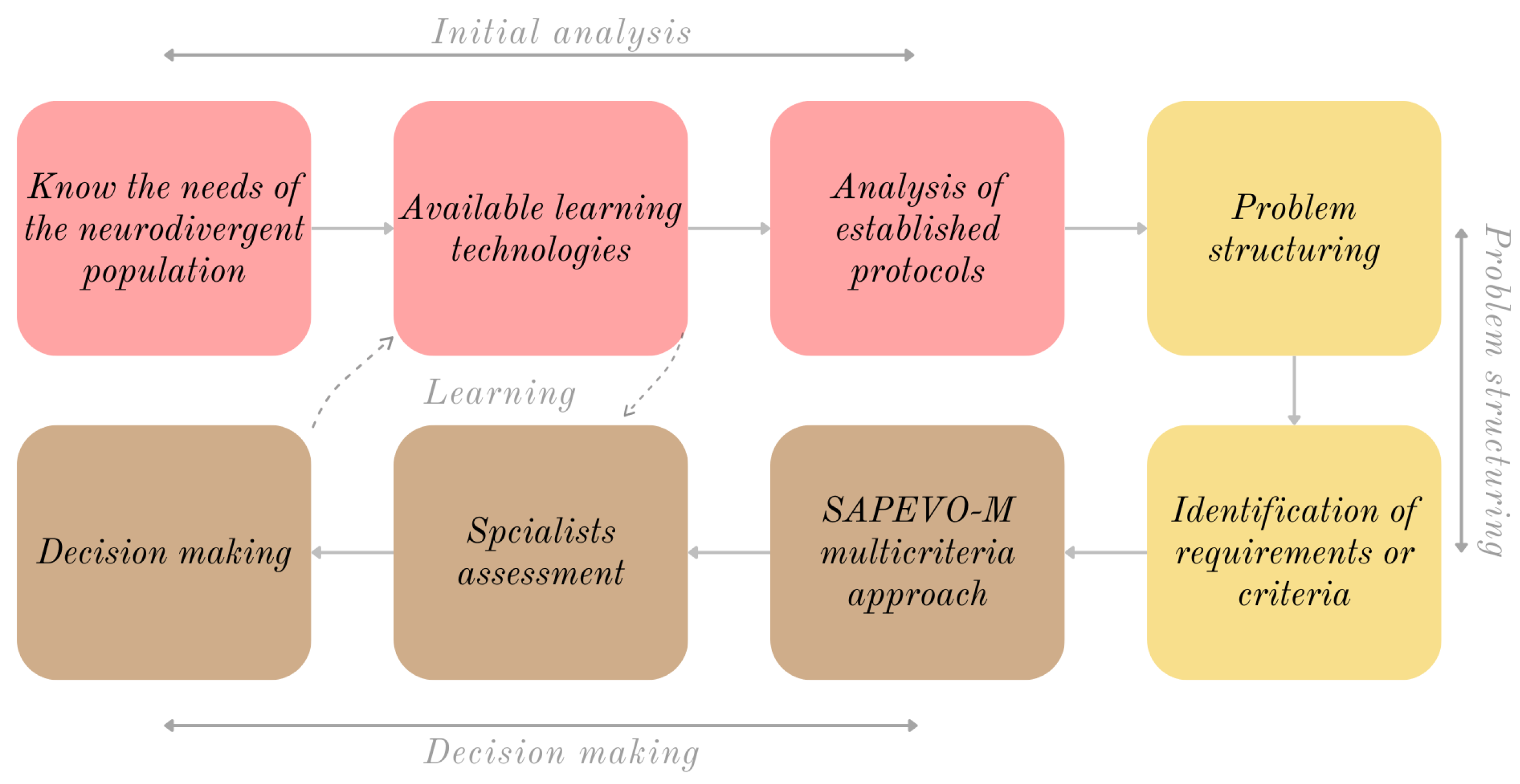

- What are the reasonable criteria on the available platforms that should be considered? Considering that the evaluation criteria for these educational platforms should include accessibility, ease of use, the ability to support social and communication development, and effective integration into the school curriculum [23];[7]. While the study emphasises the training’s importance and its focus on sensory processing needs for children with autism, it does not delineate elements for broader protocols applicable to all learning processes. It is necessary to include integration criteria with Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles, ease of use by teachers and students, and the availability of technical and ongoing training for educators. Possible constraints should also be considered, such as lack of time to develop digital materials, limited access to technology by vulnerable students, and the absence of guidelines on integrating emerging technologies [21]. The present study aims to provide a methodological structure based on criteria extracted from the various protocols to support the decision-maker in indicating a technological resource. This paper is organised into four sections. In the first section, we try to understand the scenario of the problem to be addressed, subdivided into three research questions, and how the protocols are applied. In the second section, we focus on the understanding and applicability of the ABA, JASPER, SCERTS, and DIR protocols, which we apply to structure and understand the problem [24], understanding that it is a complex and ill-defined problem, aiming to identify standard criteria that serve as a standardised input for a multicriteria decision analysis approach. In the third section, we perform an systematic review of the literature (SLR) based on the six-stage process method [15]; we took a scientometrics approach, conducted to identify research opportunities, highlighted existing gaps, and reinforced the need for a structured methodology to evaluate computational platforms and technological resources to support their cognitive and social development. Finally, we present the results with the respective discussions.

2. Methodological Flow

- Field mapping through a scoping review;

- Comprehensive search;

- Quality evaluation, which encompasses the reading and the selection of papers;

- Data extraction, which relates to the collection and capture of relevant data into a pre designed spreadsheet;

- Synthesis, which comprises the synthesis of extracted data to show the known and provide the basis for establishing the unknown; and

- Write.

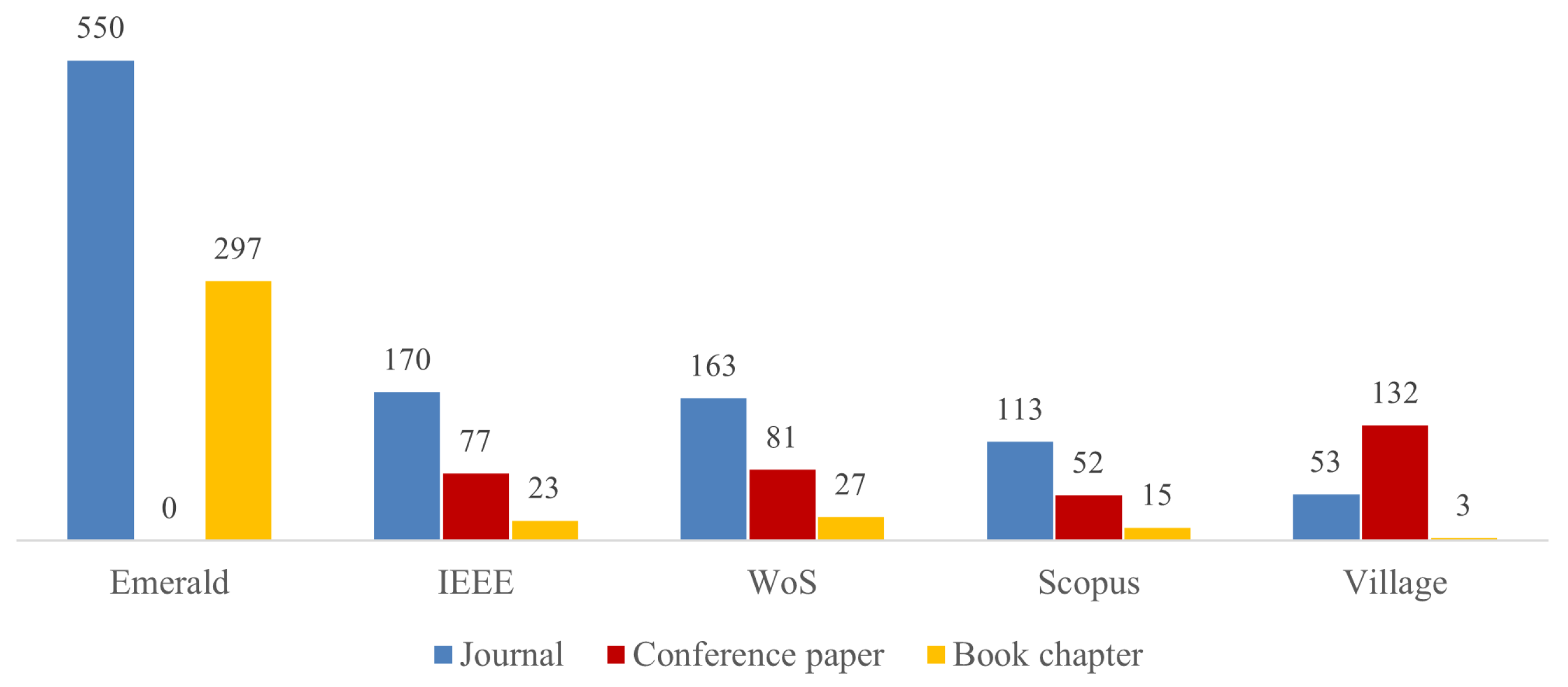

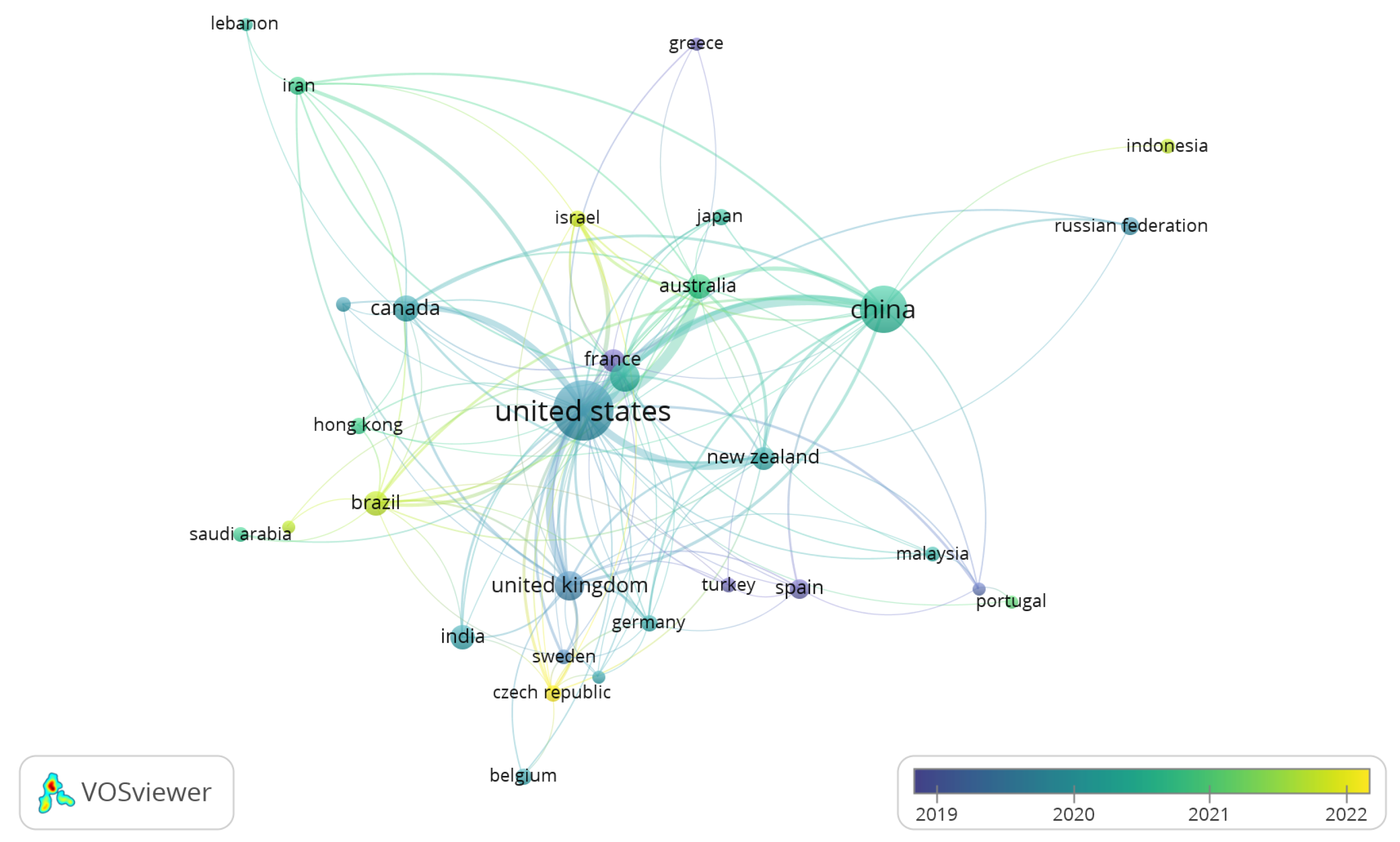

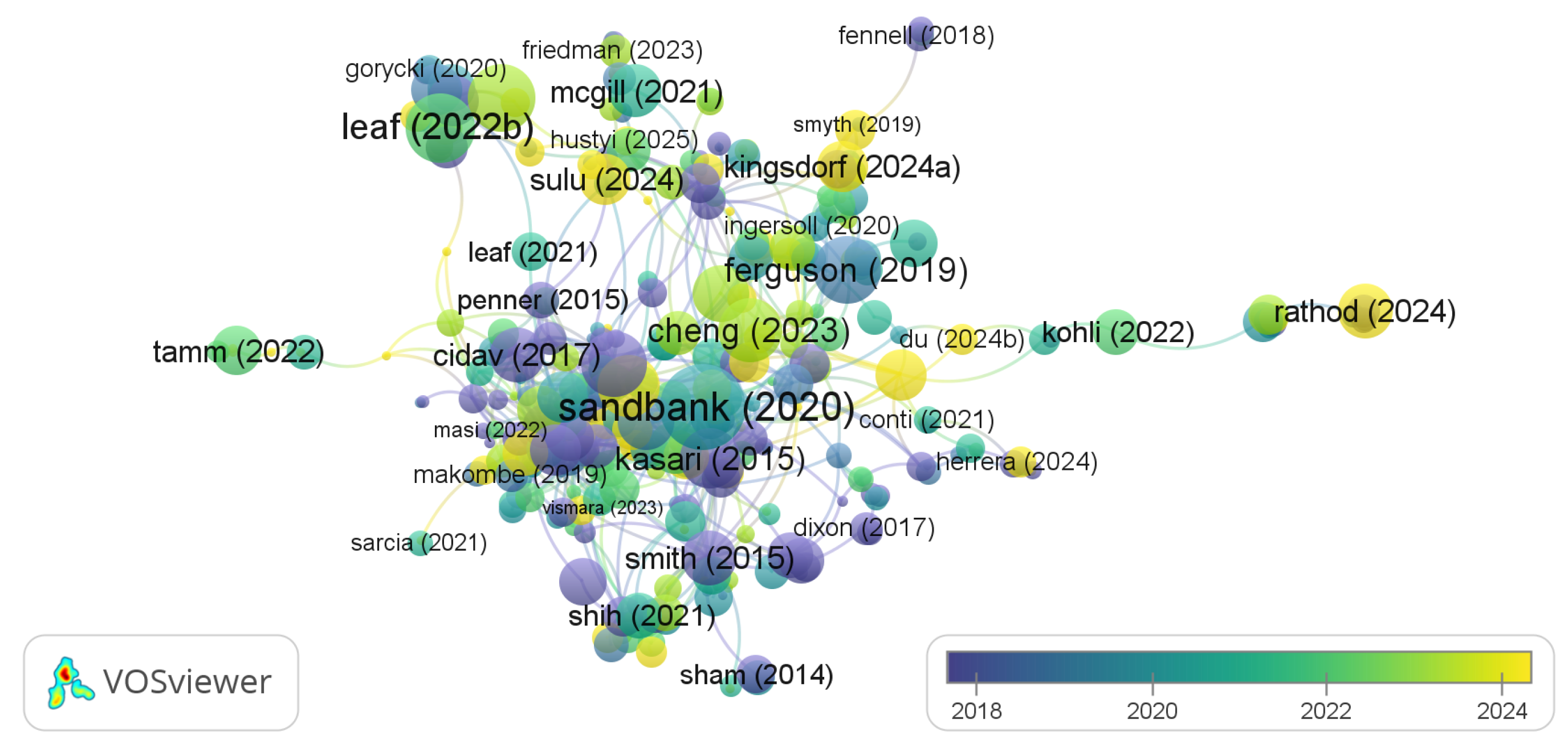

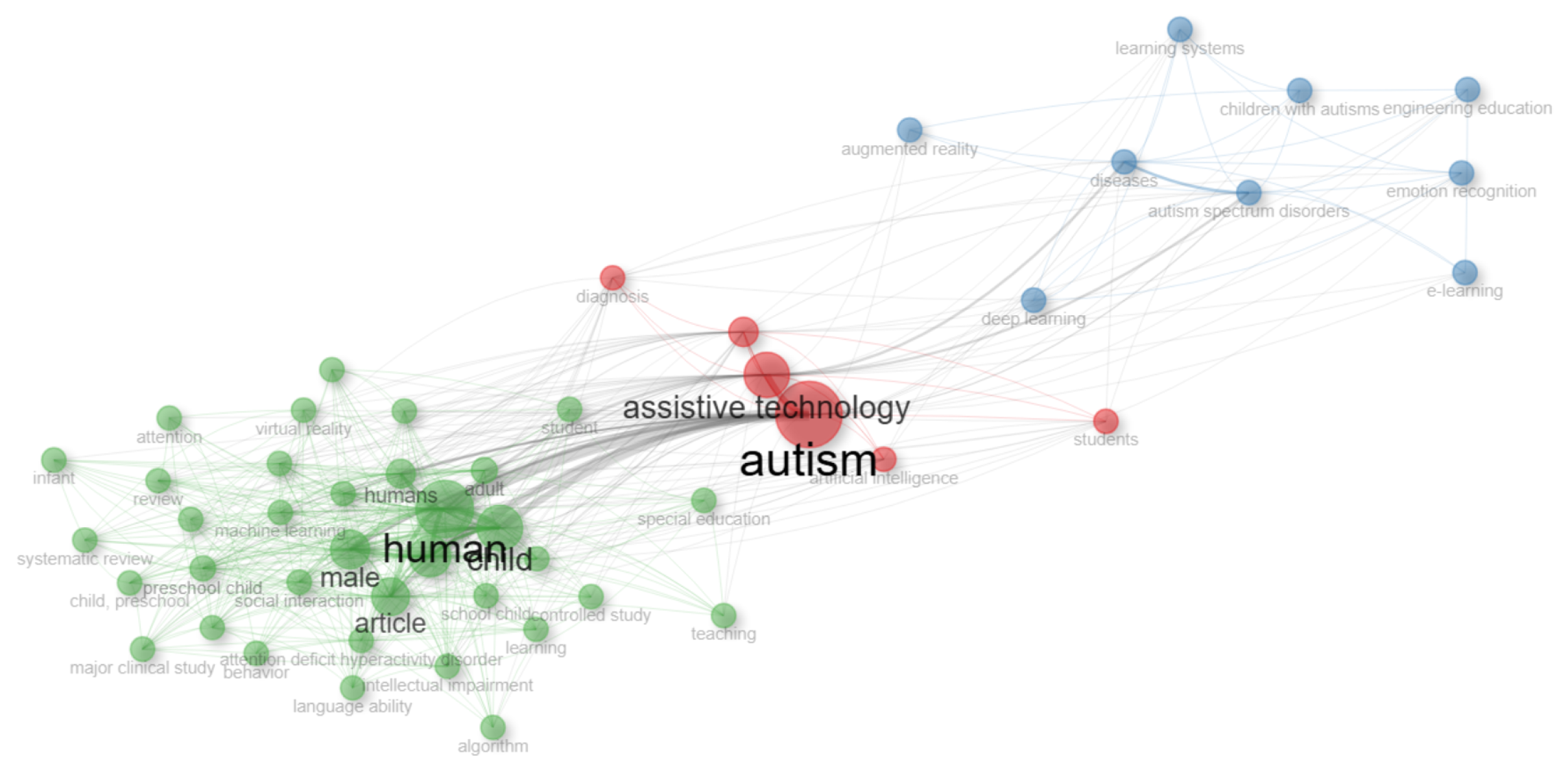

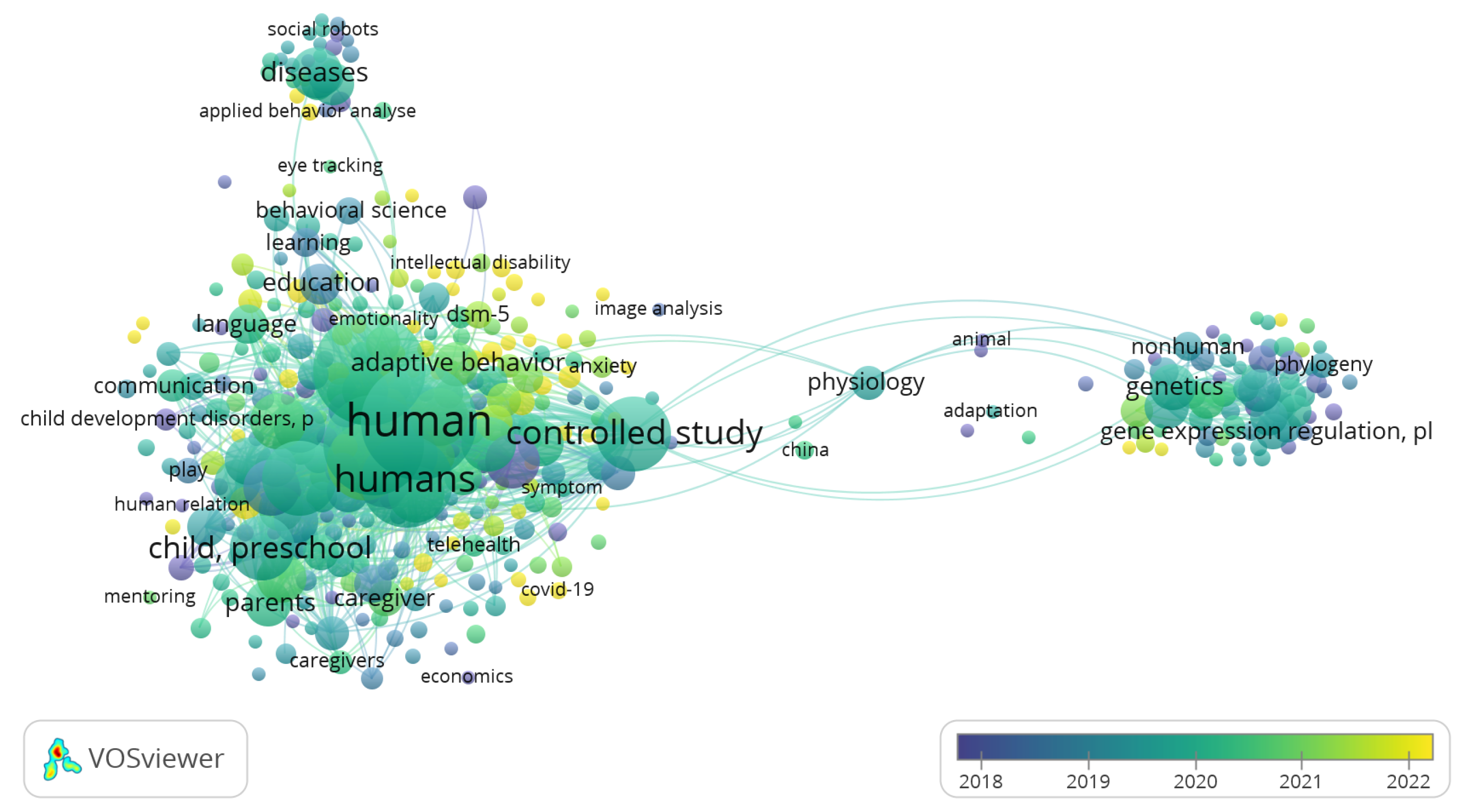

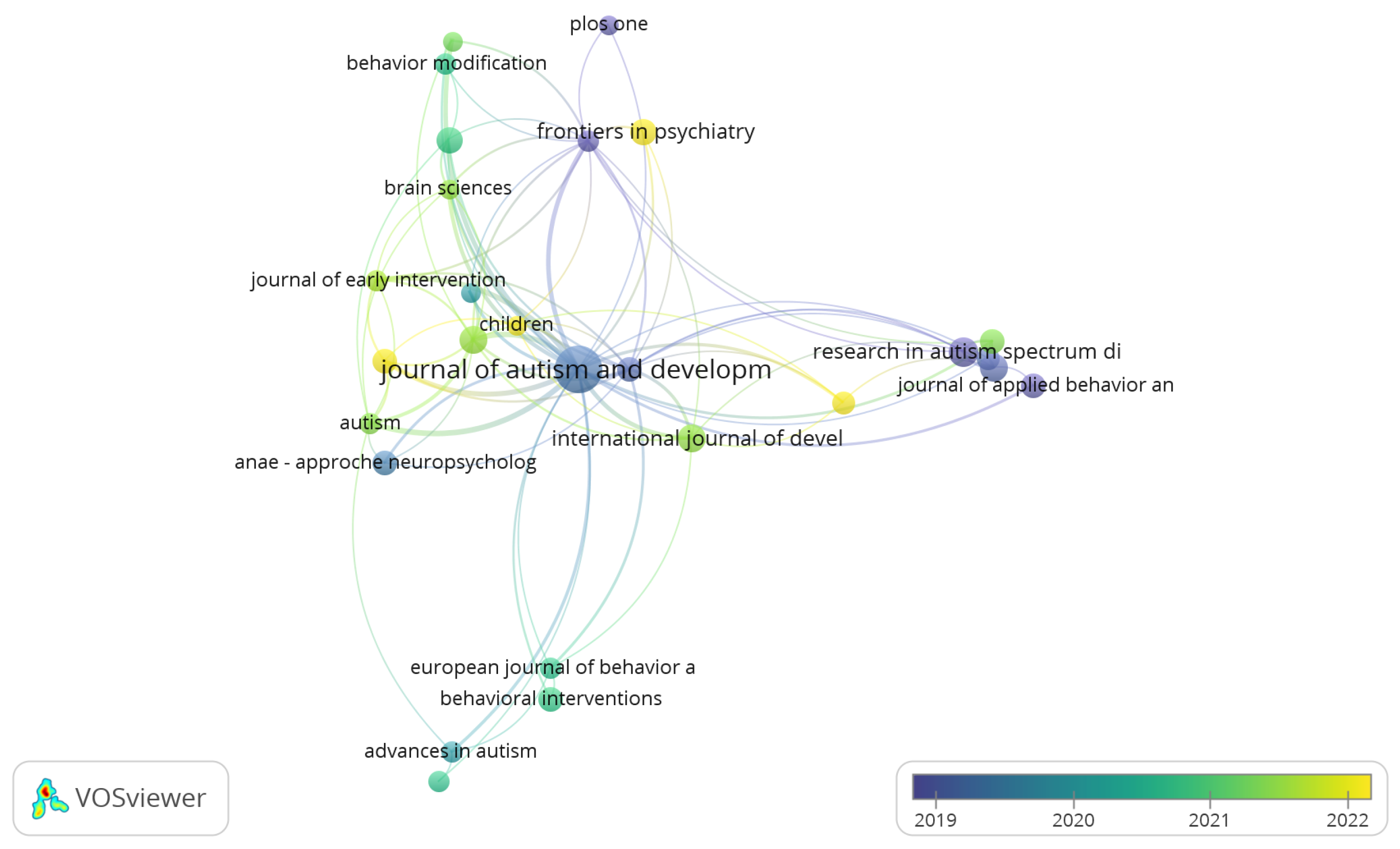

3. Scientometric Aspects of Literature

4. Structural Analysis of Protocols

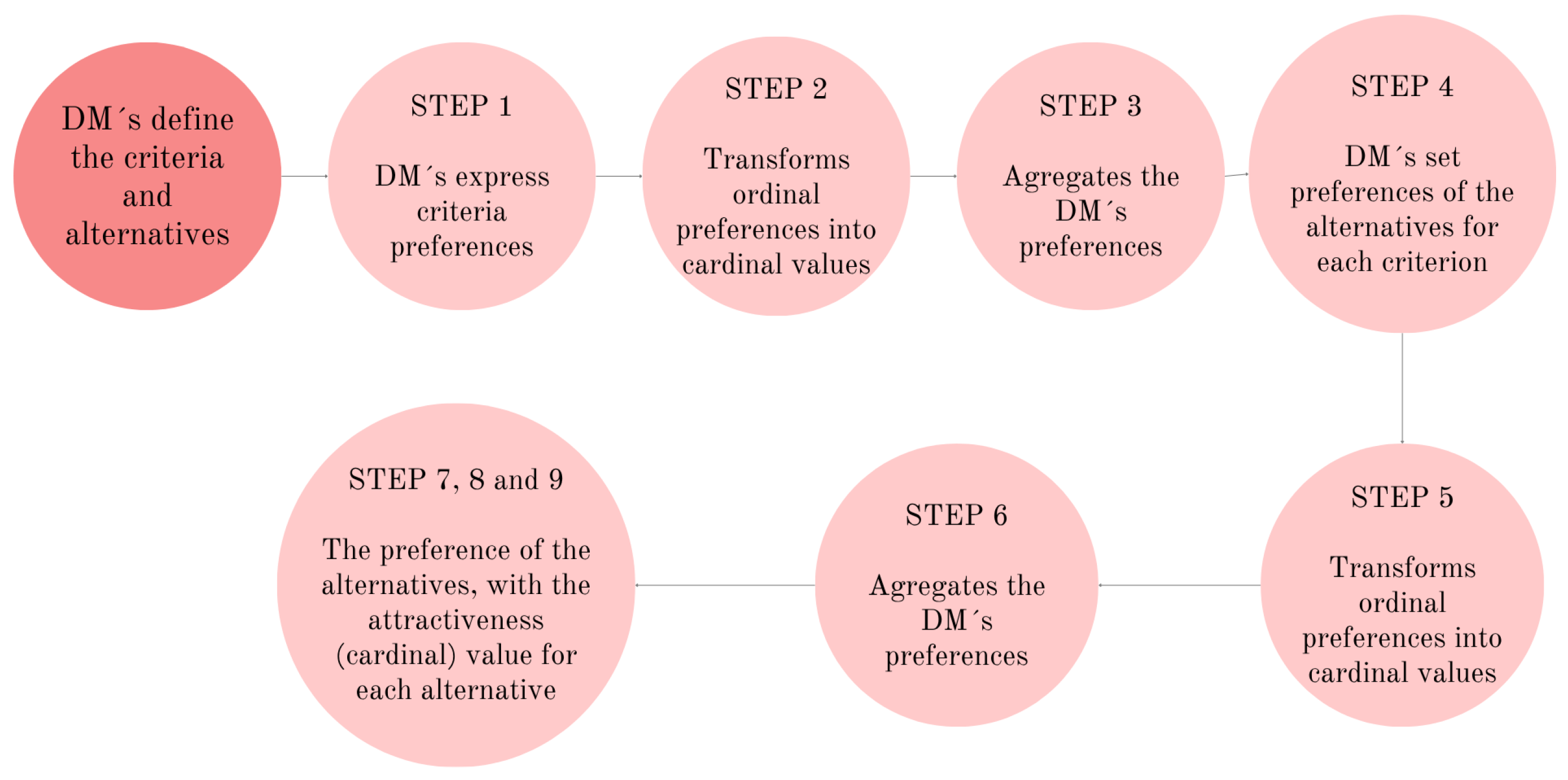

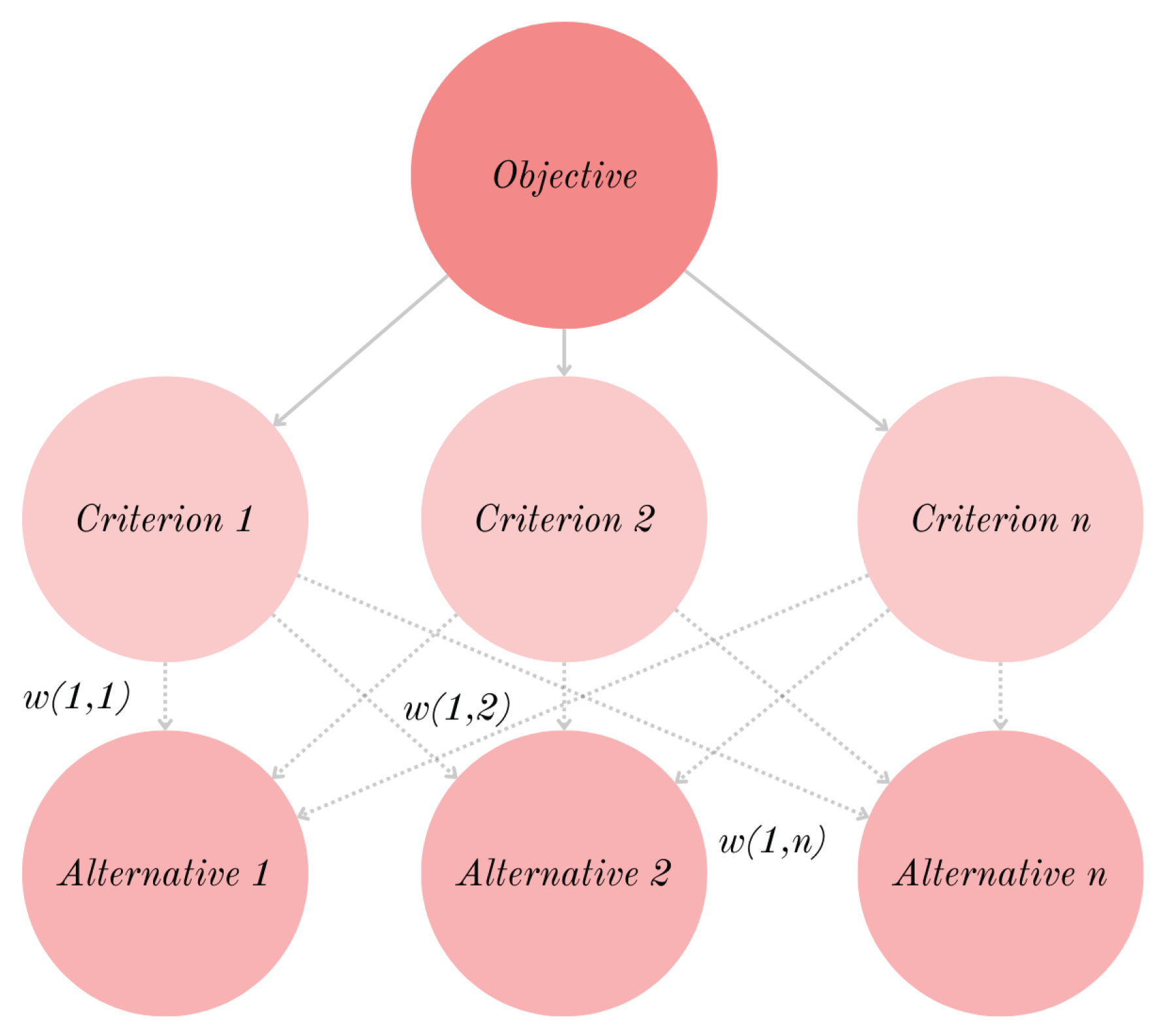

5. Multicriteria Fundamentals

- Convert ordinal preferences among the criteria into a vector of criteria weights;

- Convert the ordinal preferences among the alternatives for each criterion into partial utilities of the alternatives;

- Determine the overall weight (global utility) of each alternative.

Step 1: The Criteria

- ≈ “as important as”

- > “more important than”

- < “less important than”

Step 2: 7-Point Preference Scale

- (much less important)

- (moderately less important)

- (slightly less important)

- (equally important)

- (slightly more important)

- (moderately more important)

- (much more important)

Step 3: The Decision Maker

Normalization of the Decision Matrix

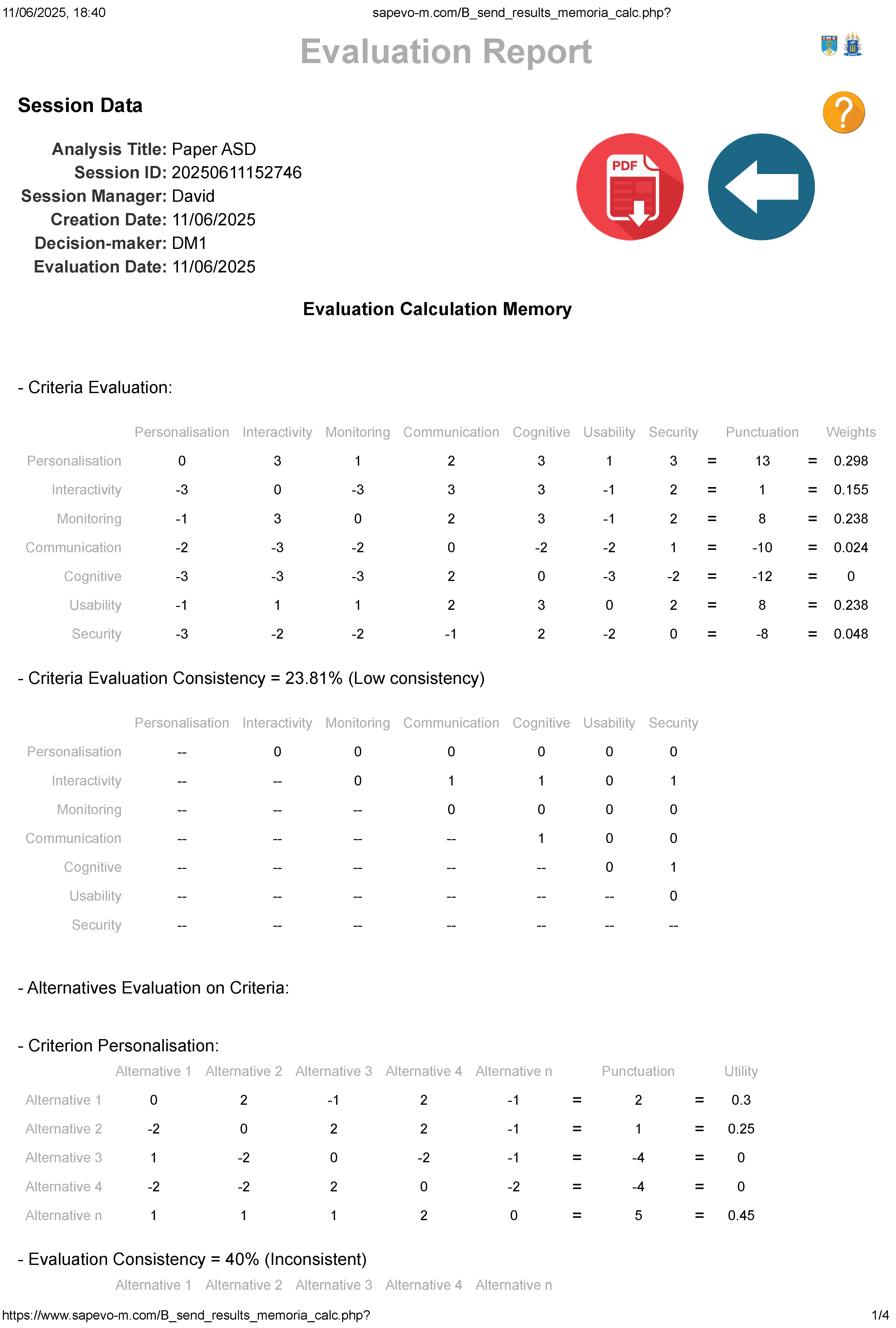

6. Applied Case Study

6.1. Analytical Report of Criteria Evaluation

6.2. Consistency and Methodological Robustness

7. Conclusion

7.1. Theoretical Implications

7.2. Practical Implications

References

- J. Zeidan et al., “Global prevalence of autism: A systematic review update,” Autism Research, vol. 15, no. 5, pp. 778–790, 2022. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O.I. Talantseva et al., “The global prevalence of autism spectrum disorder: A three-level meta-analysis,” Frontiers in Psychiatry, vol. 14, Art. no. 1071181, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A. Issac et al., “The global prevalence of autism spectrum disorder in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis,” Osong Public Health and Research Perspectives, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 3–27, 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. Orel and M. Licardo, “Systematic review of telepractice for early intervention with families of children with autism spectrum disorder,” Advances in Autism, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 19–37, 2025.

- M. Abdel Hameed, M. Hassaballah, M.E. Hosney, and A. Alqahtani, “An AI-Enabled Internet of Things Based Autism Care System for Improving Cognitive Ability of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders,” Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience, vol. 2022, pp. 1–12, 2022.

- S. Mankinen, J.M. Ferreira, and A. Mykkänen, “Peer support amongst autistic children: an examination of the communication structure in small-group discussions,” Advances in Autism, vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 382–400, 2024.

- A. Ruttledge and J. Cathcart, “An evaluation of sensory processing training on the competence, confidence and practice of teachers working with children with autism,” Irish Journal of Occupational Therapy, vol. 47, no. 1, pp. 2–17, 2019.

- A.N. Kildahl et al., “Distinguishing between autism and the consequences of early traumatisation during diagnostic assessment: a clinical case study,” Advances in Autism, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 135–148, 2024.

- M. Cruz Puerto and M. Sandín Vázquez, “Understanding heterogeneity within autism spectrum disorder: a scoping review,” Advances in Autism, vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 314–322, 2024.

- H.I.S. Reis, A.P. da S. Pereira, and L. da S. Almeida, “Construção e validação de um instrumento de avaliação do perfil desenvolvimental de crianças com Perturbação do Espectro do Autismo,” Revista Brasileira de Educação Especial, vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 183–194, 2013.

- K. Rizos et al., “A comparative analysis of error correction procedures for skill acquisition in autistic students,” Tizard Learning Disability Review, 2025.

- S. Barnes and J. Prescott, “Positive Psychology and Digital Games,” in How Digital Technologies Can Support Positive Psychology, Emerald Publishing, pp. 21–32, 2025.

- B. Zhou and X. Xu, “Progress and challenges in early intervention of autism spectrum disorder in China,” Pediatric Medicine, vol. 2, p. 26, 2019.

- J.L.B. Dias et al., “Intervenções Terapêuticas Multimodais no Transtorno do Espectro Autista: Impactos no Desenvolvimento Cognitivo e Social,” Revista Ibero-Americana de Humanidades, Ciências e Educação, vol. 10, no. 12, pp. 2285–2295, 2024.

- J.Á. Ariza and C. Hernández Hernández, “A Systematic Literature Review of Research-based Interventions and Strategies for Students with Disabilities in STEM and STEAM Education,” International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 2025.

- I. Salhi, S. Gouraguine, M. Qbadou, and K. Mansouri, “A Socially Assistive Robot Therapy for Pedagogical Rehabilitation of Autistic Learners,” in Proc. 2nd Int. Conf. on Innovative Research in Applied Science, Engineering and Technology (IRASET), IEEE, pp. 1–4, 2022.

- J. Awatramani and N. Hasteer, “Facial Expression Recognition using Deep Learning for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder,” in Proc. 2020 IEEE 5th Int. Conf. on Computing Communication and Automation (ICCCA), pp. 35–39, 2020.

- N. Perry et al., “AI technology to support adaptive functioning in neurodevelopmental conditions in everyday environments: a systematic review,” npj Digital Medicine, vol. 7, no. 1, 2024.

- S. Wallin, G. Thunberg, H. Hemmingsson, and J. Wilder, “Teachers’ use of augmented input and responsive strategies in schools for students with intellectual disability: A multiple case study of a communication partner intervention,” Autism & Developmental Language Impairments, vol. 9, 2024.

- V.N. Rathod et al., “A Survey on E-Learning Recommendation Systems for Autistic People,” IEEE Access, vol. 12, pp. 11723–11732, 2024.

- S.K. Howorth et al., “Integrating emerging technologies to enhance special education teacher preparation,” Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching & Learning, 2024.

- C. Boy et al., “Stability of emotional and behavioral problems in autistic children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic,” Advances in Autism, 2025.

- D.H.C. Patiño et al., “AutismAR Discovery: Evaluation of an Augmented Reality Application to Support the Learning of Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder in Panama,” IEEE Revista Iberoamericana de Tecnologias Del Aprendizaje, vol. 19, pp. 296–305, 2024.

- P. Checkland, “From Optimizing to Learning: A Development of Systems Thinking for the 1990s,” Journal of the Operational Research Society, vol. 36, no. 9, pp. 757–767, 1985.

- M.Â.L. Moreira, I.P. de A. Costa, M. dos Santos, and C.F.S. Gomes, “SAPEVOweb,” SAPEVO-M Software Web (v.1), 2022.

- C. Cronin, “Doing your literature review: traditional and systematic techniques,” Evaluation & Research in Education, vol. 24, no. 3, pp. 219–221, 2011.

- H.A. Ferenhof and R.F. Fernandes, “Demystifying literature review in the AI Era,” Biblios Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, no. 88, p. e003, 2025.

- L.F. Santos et al., “Transformative Service Research and the role of service robots: a bibliometric analysis,” Gestão & Produção, vol. 31, 2024. [CrossRef]

- B.M. Prizant, A.M. Wetherby, E. Rubin, and A.C. Laurent, “The SCERTS Model,” Infants & Young Children, vol. 16, no. 4, pp. 296–316, 2003.

- L. de C. Ribeiro and A.A. Cardoso, “Abordagem Floortime no tratamento da criança autista: possibilidades de uso pelo terapeuta ocupacional,” Cadernos de Terapia Ocupacional Da UFSCar, vol. 22, no. 2, pp. 399–408, 2014.

- C. Kasari, A.C. Gulsrud, S.Y. Shire, and C. Strawbridge, The JASPER Model for Children with Autism: Promoting Joint Attention, Symbolic Play, Engagement, and Regulation, 2021.

- S. Yi and S.Y. Rieh, “Children’s conversational voice search as learning: a literature review,” Information and Learning Sciences, vol. 126, no. 1/2, pp. 8–28, 2025.

- J. Liu et al., “Utilizing network analysis to identify core items of quality of life for children with autism spectrum disorder,” Autism Research, vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 370–386, 2025.

- J. Ferguson, E.A. Craig, and K. Dounavi, “Telehealth as a Model for Providing Behaviour Analytic Interventions to Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review,” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, vol. 49, no. 2, pp. 582–616, 2019.

- N. Hassoun Nedjar, Y. Djebbar, and L. Djemili, “Application of the analytical hierarchy process for planning the rehabilitation of water distribution networks,” Arab Gulf Journal of Scientific Research, vol. 41, no. 4, pp. 518–538, 2023.

- M.J. de S. Silva et al., “A Comparative Analysis of Multicriteria Methods AHP, TOPSIS-2N, PROMETHEE-SAPEVO-M1 and SAPEVO-M: Selection of a Truck for Transport of Live Cargo,” Procedia Computer Science, vol. 214, pp. 86–92, 2022.

- T. Ni, X. Zhang, P. Leng, M. Pelling, and J. Xu, “Comprehensive benefits evaluation of low impact development using scenario analysis and fuzzy decision approach,” Scientific Reports, vol. 15, no. 1, p. 2227, 2025.

- M.M. Muñoz, S. Kazakov, and J.L. Ruiz-Alba, “Sectorial evaluation and characterization of internal marketing orientation through multicriteria analysis,” Operational Research, vol. 24, no. 2, 2024.

- G.G. Shayea et al., “Fuzzy Evaluation and Benchmarking Framework for Robust Machine Learning Model in Real-Time Autism Triage Applications,” International Journal of Computational Intelligence Systems, vol. 17, no. 1, p. 151, 2024.

- D. de O. Costa, A. Bonamigo, M. Santos, and C.M.R. de Oliveira, “Structuring a Computational Tool for Defining Multicriteria Methods: A Proposal for a Systematic Literature Review,” Pesquisa Operacional, 2025.

- C.F.S. Gomes et al., “SAPEVO-M: A GROUP MULTICRITERIA ORDINAL RANKING METHOD,” Pesquisa Operacional, vol. 40, 2020.

- S. Zakeri, D. Konstantas, P. Chatterjee, and E.K. Zavadskas, “Soft cluster-rectangle method for eliciting criteria weights in multi-criteria decision-making,” Scientific Reports, vol. 15, no. 1, p. 284, 2025.

- F. Ackermann, “Managing grand challenges: Extending the scope of problem structuring methods and behavioural operational research,” European Journal of Operational Research, vol. 319, no. 2, pp. 373–383, 2024.

- J. Mingers and J. Rosenhead, “Problem structuring methods in action,” European Journal of Operational Research, vol. 152, no. 3, pp. 530–554, 2004.

- Z. Chourabi, F. Khedher, A. Babay, and M. Cheikhrouhou, “Multi-criteria decision making in workforce choice using AHP, WSM and WPM,” The Journal of The Textile Institute, vol. 110, no. 7, pp. 1092–1101, 2019.

- C. Garritty et al., “Updated recommendations for the Cochrane rapid review methods guidance for rapid reviews of effectiveness,” BMJ, p. e076335, 2024.

- G. Du, Y. Guo, and W. Xu, “The effectiveness of applied behavior analysis program training on enhancing autistic children’s emotional-social skills,” BMC Psychology, vol. 12, no. 1, p. 568, 2024.

- M.D. Sulu et al., “A Meta-Analysis of Applied Behavior Analysis-Based Interventions for Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) in Turkey,” Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 2024.

- L. Tamm, H.A. Day, and A. Duncan, “Comparison of Adaptive Functioning Measures in Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder Without Intellectual Disability,” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, vol. 52, no. 3, pp. 1247–1256, 2022.

- J.B. Leaf et al., “Concerns About ABA-Based Intervention: An Evaluation and Recommendations,” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, vol. 52, no. 6, pp. 2838–2853, 2022.

- J.B. Leaf et al., “Advances in Our Understanding of Behavioral Intervention: 1980 to 2020 for Individuals Diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder,” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, vol. 51, no. 12, pp. 4395–4410, 2021.

- Q. Yu, E. Li, L. Li, and W. Liang, “Efficacy of Interventions Based on Applied Behavior Analysis for Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Meta-Analysis,” Psychiatry Investigation, vol. 17, no. 5, pp. 432–443, 2020.

- H. Kupferstein, “Evidence of increased PTSD symptoms in autistics exposed to applied behavior analysis,” Advances in Autism, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 19–29, 2018.

- A. Estes et al., “Long-Term Outcomes of Early Intervention in 6-Year-Old Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder,” Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, vol. 54, no. 7, pp. 580–587, 2015.

- T. Smith and S. Iadarola, “Evidence Base Update for Autism Spectrum Disorder,” Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, vol. 44, no. 6, pp. 897–922, 2015.

- R. MacDonald et al., “Assessing progress and outcome of early intensive behavioral intervention for toddlers with autism,” Research in Developmental Disabilities, vol. 35, no. 12, pp. 3632–3644, 2014.

- G. Vivanti et al., “Effectiveness and Feasibility of the Early Start Denver Model Implemented in a Group-Based Community Childcare Setting,” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, vol. 44, no. 12, pp. 3140–3153, 2014.

- E. Sham and T. Smith, “Publication bias in studies of an applied behavior-analytic intervention: An initial analysis,” Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, vol. 47, no. 3, pp. 663–678, 2014.

- F. Mohammadzaheri et al., “A Randomized Clinical Trial Comparison Between Pivotal Response Treatment (PRT) and Structured Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) Intervention for Children with Autism,” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, vol. 44, no. 11, pp. 2769–2777, 2014.

- D. Adams, M. Clark, and K. Simpson, “The Relationship Between Child Anxiety and the Quality of Life of Children, and Parents of Children, on the Autism Spectrum,” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, vol. 50, no. 5, pp. 1756–1769, 2020.

- C. Kasari et al., “Randomized comparative efficacy study of parent-mediated interventions for toddlers with autism,” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, vol. 83, no. 3, pp. 554–563, 2015.

- S. Kingsdorf et al., “Examining the perceptions of needs, services and abilities of Czech and North Macedonian caregivers of children with autism and trainers,” International Journal of Developmental Disabilities, vol. 70, no. 3, pp. 479–492, 2024.

- Y.-C. Chang, S.Y. Shire, W. Shih, C. Gelfand, and C. Kasari, “Preschool Deployment of Evidence-Based Social Communication Intervention: JASPER in the Classroom,” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, vol. 46, no. 6, pp. 2211–2223, 2016.

- M.A.L. Moreira, I.P.A. Costa, M. dos Santos, and C.F.S. Gomes, SAPEVO-M Software Web (v.1), 2022.

| Source | Journal | % |

|---|---|---|

| Emerald | 550 | 52,43% |

| IEEE | 170 | 16,21% |

| WoS | 163 | 15,54% |

| Scopus | 113 | 10,77% |

| Village | 53 | 5,05% |

| Total Global | 1049 |

| Author | Paper |

|---|---|

| [47] Du et al. (2024) | The effectiveness of applied behaviour analysis program training on enhancing autistic children’s emotional-social skills |

| [20] Rathod et al. (2024b) | A Survey on E-Learning Recommendation Systems for Autistic People |

| [48] Sulu et al. (2024) | A Meta-Analysis of Applied Behaviour Analysis-Based Interventions for Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) in Turkey |

| [49] Tamm et al. (2022a) | Comparison of Adaptive Functioning Measures in Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder Without Intellectual Disability |

| [50] Leaf et al. (2022) | Concerns About ABA-Based Intervention: An Evaluation and Recommendations |

| [51] Leaf et al. (2021) | Advances in Our Understanding of Behavioral Intervention: 1980 to 2020 for Individuals Diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder |

| [52] Yu et al. (2020) | Efficacy of Interventions Based on Applied Behaviour Analysis for Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Meta-Analysis |

| [34] Ferguson et al. (2019) | Telehealth as a Model for Providing Behaviour Analytic Interventions to Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review |

| [53] Kupferstein (2018) | Evidence of increased PTSD symptoms in autistics exposed to applied behaviour analysis |

| [63] Chang et al. (2016) | Preschool Deployment of Evidence-Based Social Communication Intervention: JASPER in the Classroom |

| [61] Kasari et al. (2015) | Randomised comparative efficacy study of parent-mediated interventions for toddlers with autism |

| [54] Estes et al. (2015) | Long-Term Outcomes of Early Intervention in 6-Year-Old Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder |

| [55] Smith and Iadarola (2015) | Evidence Base Update for Autism Spectrum Disorder |

| [56] MacDonald et al. (2014) | Assessing progress and outcome of early intensive behavioural intervention for toddlers with autism |

| [57] Vivanti et al. (2014) | Effectiveness and Feasibility of the Early Start Denver Model Implemented in a Group-Based Community Childcare Setting |

| [58] Sham and Smith (2014) | Publication bias in studies of an applied behaviour-analytic intervention: An initial analysis |

| [59] Mohammadzaheri et al. (2014) | A Randomised Clinical Trial Comparison Between Pivotal Response Treatment (PRT) and Structured Applied Behaviour Analysis (ABA) Intervention for Children with Autism |

| Category | ABA | DIR/Floortime | JASPER | SCERTS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central approach | Adapting behaviours to promote social skills and minimise inappropriate behaviours | Emotional and social development through playful interactions | Joint attention, symbolic play, engagement and regulation | Social communication, emotional regulation and transactional support |

| Approach | Behavioral, based on functional analysis of behaviour | Behavioral, based on functional analysis of behaviour | Developmental, and play-based | Transactional and family-centred |

| Method | Positive reinforcement, extinction, modelling and structured teaching | Playful interactions on the floor (Floortime) to promote engagement and connection | Playful interactions, modelling, expansion and imitation | Personalised strategies to promote communication and emotional regulation |

| Areas Activity | Clinics, schools, home and community | Clinics, schools, home and community | Clinics, schools, home and community | Clinics, schools, home and community |

| Environment | Natural and structured environments | Natural and structured environments | Natural and structured environments | Natural and structured environments |

| Specific audience | Children, families and professionals | Children and families | Children between 1 and 8 years old, families and professionals | Children and families |

| References | Rutledge and Cathcart (2019) | Greenspan and Wieder (2008) | Kasari et al. (2021) | Prisant et al. (2003) |

| ABA | DIR/Floortime | JASPER | SCERTS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social and Communication Skills DevelopmentWhereas the approach is to maximise social and communication skills, each emphasises different aspects | Behaviour modification to promote social skills and reduce inappropriate behaviours | Emotional and social development through playful interactions | Joint attention, symbolic play, engagement, and regulation | Social communication and emotional regulation |

| Child-Centred and Individualised ApproachApproach based on individualisation, adapting strategies to the specific needs of each child | Develop personalised intervention plans based on functional behaviour analysis | Follows the child’s interests during playful interactions | Adapts intervention strategies to the child’s profile and level of development | Personalises interventions based on the needs of the child and family |

| Natural and Playful InteractionsValuing natural and playful interactions to promote cognitive development | Uses playful activities and natural reinforcers to teach skills | Relies on floor play to promote engagement | Focuses on symbolic play and playful interactions to develop social skills | Encourages social and emotional interactions in natural contexts |

| Family Involvement and the Natural EnvironmentReinforce the importance of family involvement and the application of strategies in natural environments | Includes training for parents and caregivers, aiming at generalising learned skills | Encourages parents to participate in playful interactions with the child actively | Involves parents and caregivers in implementing strategies at home and in other natural environments | Involves the family in the intervention process and promotes the generalisation of skills to natural contexts |

| Evidence-BasedBased on scientific evidence and validated by research and clinical studies | Widely recognised for its effectiveness, with decades of research in behaviour analysis | Based on theories of emotional and social development | Supported by clinical studies that demonstrate its effectiveness in developing social skills | Based on research on socio-emotional development and communication |

| Promoting Inclusion and Quality of LifeFocuses on maximising improvements in quality of life and promoting social inclusion | Focuses on independence and autonomy, reducing behaviours that impede inclusion | Promotes emotional and social development to strengthen relationships | Develops social and communication skills to facilitate interaction with peers and family | Seeks to improve communication and emotional regulation to facilitate social participation |

| Personalisation and Adaptation | Ability to adjust activities according to the child’s level of development. Configuration of individual profiles, allowing content customisation. Flexibility to meet different ASD profiles, aligned with the ABA, DIR/Floortime, JASPER, and SCERTS protocols. |

| Interactivity and Engagement | Use of attractive visual and audio elements to maintain the child’s attention. Use gamification to reinforce positive behaviours (points, rewards, progression) simulation of social interactions through avatars or virtual environments. |

| Monitoring and Feedback | Detailed record of the child’s progress (qualitative and quantitative data). Automatic reports for parents, therapists, and educators. Real-time feedback to reinforce behaviours and learning. |

| Communication and Language | Resources for developing verbal and non-verbal communication. Support alternative/augmentative communication (pictograms, speech synthesisers) integration with speech recognition and response analysis systems. |

| Cognitive and Social Development | Stimulation of joint attention and symbolic play (essential in JASPER and SCERTS). Strategies to promote socio-emotional skills and self-regulation. Activities that encourage the recognition and expression of emotions. |

| Usability and Accessibility | Intuitive interface adapted for young children. Compatibility with different devices (tablets, smartphones, computers). Accessibility options (high contrast, sound adjustment, simplified commands). |

| Security and Privacy | Parental control to configure access and monitor interactions. Children’s data protection, ensuring compliance with regulations. Absence of advertising or unsupervised content. |

| Platforms | Features |

|---|---|

| Matraquinha | A communication app designed for children with autism, featuring over 250 pictographic cards organized into categories like food, hygiene, and emotions. Helps structure routines and stimulate expression for children aged 4–6. |

| MITA (Mental Imagery Therapy for Autism) | A cognitive and language therapy platform utilizing interactive imagery games designed to strengthen mental integration skills. Especially suitable for early intervention in children aged 2 to 6. It is based on evidence-based learning principles and includes structured daily training exercises to support the development of receptive and expressive language, visual reasoning, and attention span. |

| Express | AAC-based platform offering customizable visual cards and sentence-building tools. Supports communication development through intuitive visual structuring, ideal for preschool-aged children with speech limitations. |

| TEA EducaGames | Suite of gamified apps developed for preschool and early elementary students with autism. Includes modules for basic math, alphabet, sequencing, and emotional identification using playful interfaces. |

| Lina Educa | Brazilian platform focused on inclusive literacy for children with TEA. Provides pedagogically structured games with progress-tracking tools for parents and educators. |

| Livox | Award-winning platform for alternative and augmentative communication (AAC), adaptable for children with ASD who have verbal and motor difficulties. Enables learning through custom symbols, audio, and accessible navigation. |

| Rotina Divertida | App helps structure the daily routines of children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) in a fun and visual way. Promotes autonomy and predictability, reducing anxiety in early childhood education contexts. |

| WebSCALA | A web-based educational system that integrates AI to personalize learning paths for children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Designed to support teachers and therapists in structured interventions during early development stages. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).