1. Introduction

The equine proximal interphalangeal joint (PIPJ) has traditionally been considered a low-motion joint and is often modelled as a rigid link between the high-motion metacarpophalangeal and distal interphalangeal joints in biomechanical models of the digit [

1,

2,

3]. However, in vivo studies have reported substantial ranges of motion during locomotion, suggesting a greater functional role than previously recognized [

4,

5].

The PIPJ primarily permits flexion and extension in the sagittal plane within the range of motion of 13 +/- 4 degrees at walk and 14 +/- 4 degrees at trot. However, the PIPJ is also subject to movements outside the sagittal plane, specifically in adduction/abduction and axial rotation, particularly in response to asymmetric loads [

6,

7]. Three-dimensional kinematic studies have confirmed the presence of small but significant amounts of these extra-sagittal movements during locomotion, within the range of motion of 3 or 4 +/- 1 degree, at walk and trot, respectively [

8]. An in vitro study has demonstrated that the PIPJ undergoes significant axial rotation and collateral motion under asymmetric loading, highlighting its key role in maintaining balance [

9]. The functional importance of these three-dimensional (3D) movements has been emphasised by several authors, who suggest they play a crucial role in compensating for ground irregularities or during turning [

10,

11,

12].

Clinically, however, these multi-planar movements are suspected of contributing to articular pain and joint damage when excessive or repetitive [

7,

13,

14]. The collateral ligaments, which are the primary stabilizers restricting movements outside the sagittal plane [

15,

16], are particularly susceptible to injury during athletic activities involving abrupt directional changes [

8]. Differently, pastern laceration could be responsible of partial or complete disruption of the lateral or medial collateral ligaments of the PIPJ. For severe ligament injuries, such as complete laceration or avulsion, surgical intervention is typically required to obtain PIPJ stabilization. Arthrodesis of the PIPJ is the current treatment of choice, with the goal of eliminating articular movement and associated pain [

17]. This procedure, however, entails a prolonged recovery period and may be associated with complications such as postoperative pain, implant failure, infection, excessive bone formation, and laminitis in the contralateral limb [

18,

19]. Moreover, a return to athletic performance is not always achievable, particularly after forelimb injuries [

20]. The biomechanical profile of the PIPJ, combined with the capacity for multi-planar movement, should be considered in clinical cases requiring PIPJ arthrodesis, as the loss of mobility may exacerbate pathologies in adjacent joints [

21]. Consequently, alternative techniques for repairing injured collateral ligaments in the equine PIPJ that preserve the joint’s biomechanical function are currently being developed, aiming to improve the quality of life in the affected horses and the potential for a successful return to sport.

A reliable and reproducible methodology is therefore required to characterise the biomechanical behaviour of the PIPJ and its collateral ligaments. Three-point bending is among the most commonly used mechanical methods to characterize the material and biomechanical properties of long bones [

22,

23]. Its widespread use is due to its ability to create an internal load distribution analogous to physiological conditions, particularly at critical locations, establishing it as a standard for evaluating bone strength and for deriving parameters such as stiffness and flexural strength [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. Furthermore, its reliability in assessing bone tissue mechanics has been demonstrated in numerous studies, including those validating bone repair and regeneration techniques in small animal models [

29].

Therefore, the aim of this study is to develop a three-point bending test setup to quantitatively and reproducibly characterise the biomechanical behaviour of extrasagittale movements in the equine PIPJ, with a specific focus on loading conditions designed to over-stretch the collateral ligaments. This ex-vivo model will provide a standardized platform for the future comparative evaluation of novel surgical techniques to repair injured collateral ligaments.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Specimen Preparation

Seven proximal interphalangeal joints were isolated from equine patients that died or were euthanized for reasons independent of this study at the Veterinary Teaching Hospital of Turin, with informed owner consent. The sample set consisted of five forelimb and two hindlimb. Specimens utilized in the mechanical tests were carefully dissected by the same veterinary surgeon. Each specimen included the proximal and middle phalanges, which were disarticulated at the level of the metacarpophalangeal and distal interphalangeal joints. All the surrounding periarticular soft tissues were removed, taking care to leave intact the collateral ligaments of the PIPJ and the corresponding joint capsule. One joint was tested fresh. Two specimens were frozen after collection and thawed 24 hours before testing. The remaining four specimens underwent a repeated freeze–thaw cycle (thawed, refrozen, and thawed again 24 hours prior to testing).

2.2. Experimental Setup

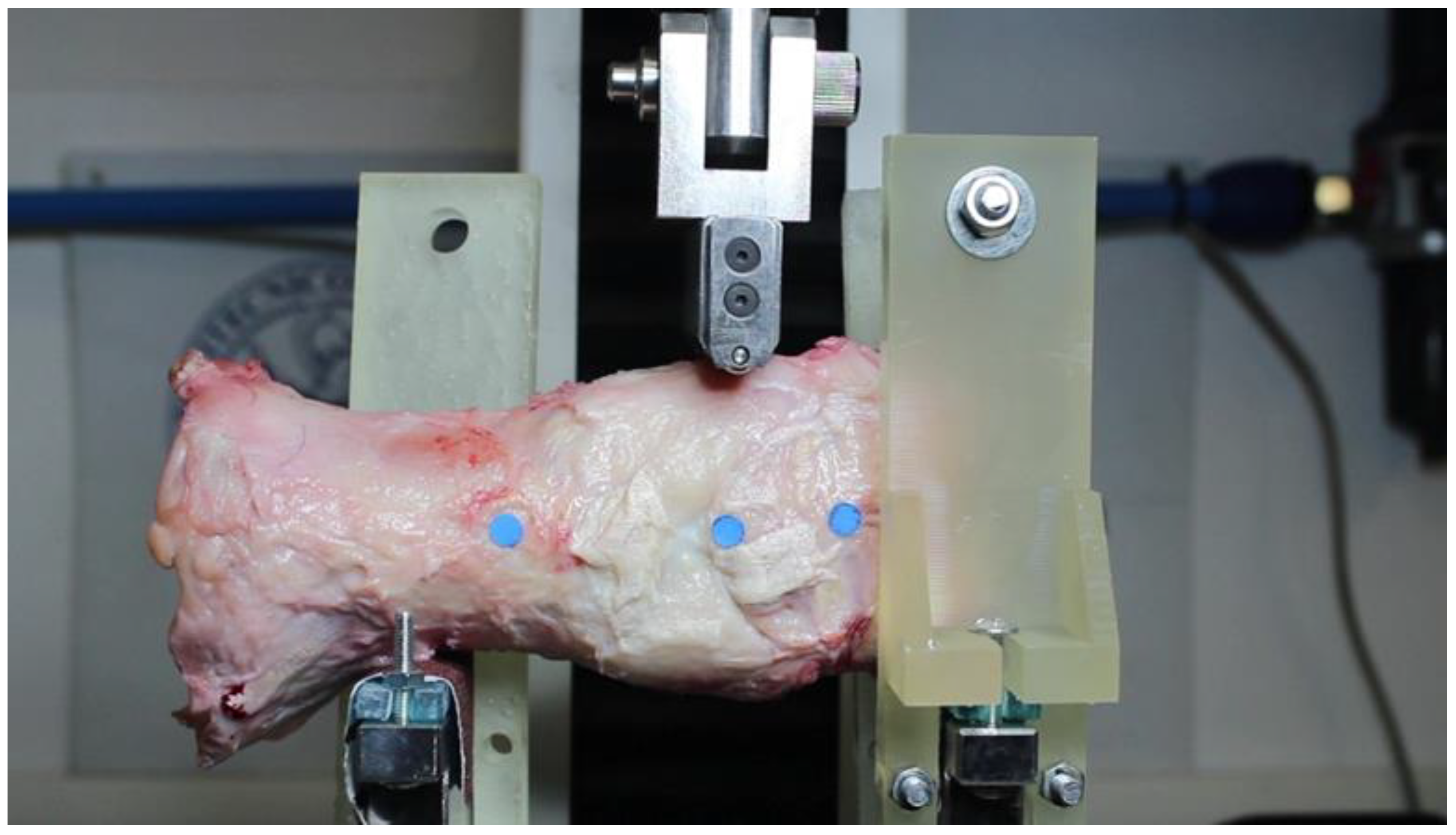

Mechanical testing was performed using an MTS Insight® Electromechanical Testing System equipped with a 1000 N load cell. Two specific components were designed and manufactured to integrate with the machine's existing structure. The first element consists of a pair of lower supports, whose primary function is to provide a solid, flat base on which specimens can lean stably during testing. The second component consists of supplementary supports, designed to constrain sample rotation during testing by being positioned on either side of the middle phalanx and on the posterior aspect of the proximal phalanx. These custom, 3D-printed system were used to stabilize the joints. They allowed joint’s bending in the medio-lateral plane, while constraining unwanted degrees of freedom such as slippage and rotation. Each joint was positioned with its lateral side facing upward, and the distance between the two lower supports was adjusted individually for each specimen. The experimental setup is shown in

Figure 1.

2.3. Testing Protocol

A three-point non-destructive bending test was performed on each joint to evaluate its mechanical response. For each specimen, three to four tests were conducted. A metallic rod was aligned with the upper portion of PIPJ centre and lowered at a constant displacement rate of 5 mm/min. Tests were terminated when the load approached the 1000 N limit of the load cell, unless terminated earlier due to specimen slippage or rotation.

2.4. Data Acquisition and Analysis

During testing, load and displacement data were directly recorded by the MTS system. Simultaneously, the movement of three coloured markers applied to the joint was captured using a digital camera. A custom MATLAB script was used to analyse the video footage and calculate the medio-lateral joint bending angle during testing as a variation relative to the initial unloaded configuration.

Figure 1.

Experimental setup for the three-point bending test of the equine proximal interphalangeal joint.

Figure 1.

Experimental setup for the three-point bending test of the equine proximal interphalangeal joint.

3. Results

In the initial trials, specimen instability, manifested as horizontal slippage or sagittal rotation, occasionally led to premature termination. The introduction of a fixed loading rod in subsequent experiments minimized these issues, enabling more stable testing conditions and consistent data collection until either a load plateau or the machine’s safety limit was reached.

3.1. Load-Displacement and Time-Angle Curves

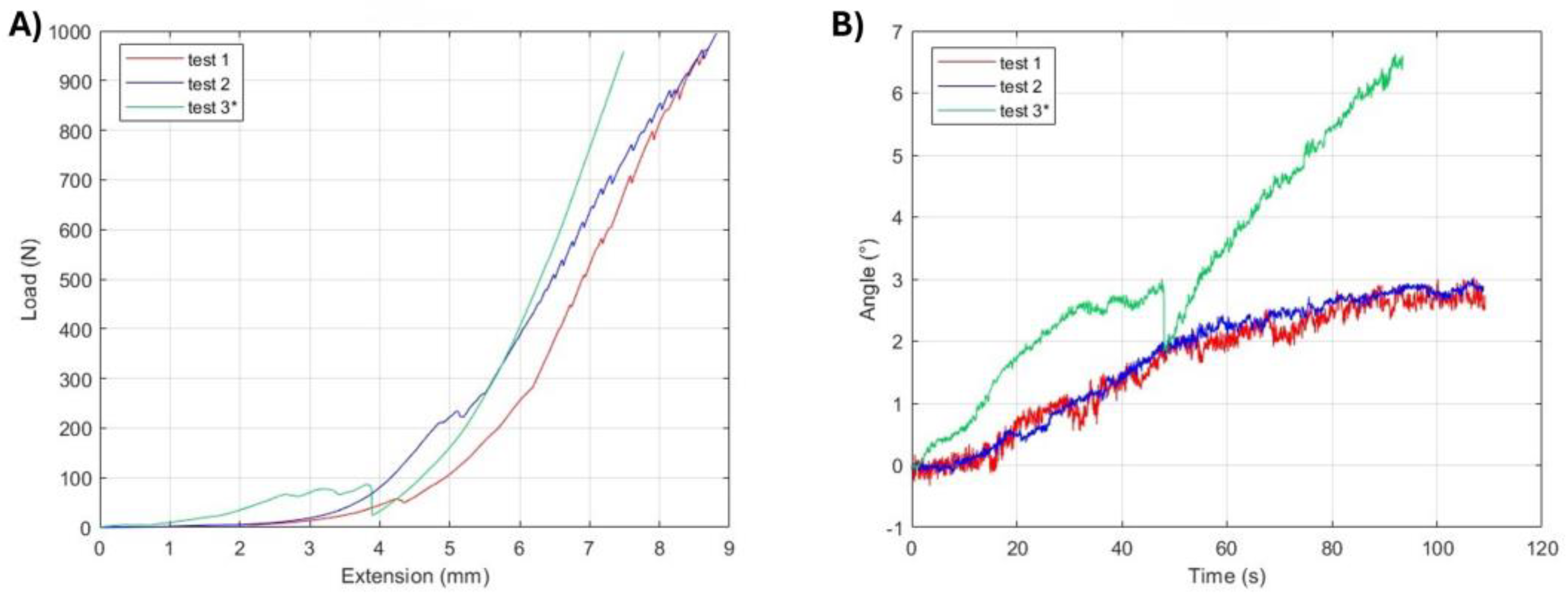

Specimen 1 (Hindlimb, Frozen–Thawed) underwent three tests. The first two tests were terminated due to sagittal rotation of the specimen near the end of the loading cell's capability, while the third test was interrupted after approximately 50 seconds because of horizontal slippage. For this final test, the specimen was rotated to a position in which the medial collateral ligament facing upward. The load–displacement curves (

Figure 2a) exhibited an irregular progression of load with increasing displacement, characterized by marked changes in slope. The corresponding time–angle curves (

Figure 2b) confirmed this irregularity, with the medio-lateral bending angle increasing in a non-linear and non-uniform manner, consistent with rotation and slippage of the specimen during loading.

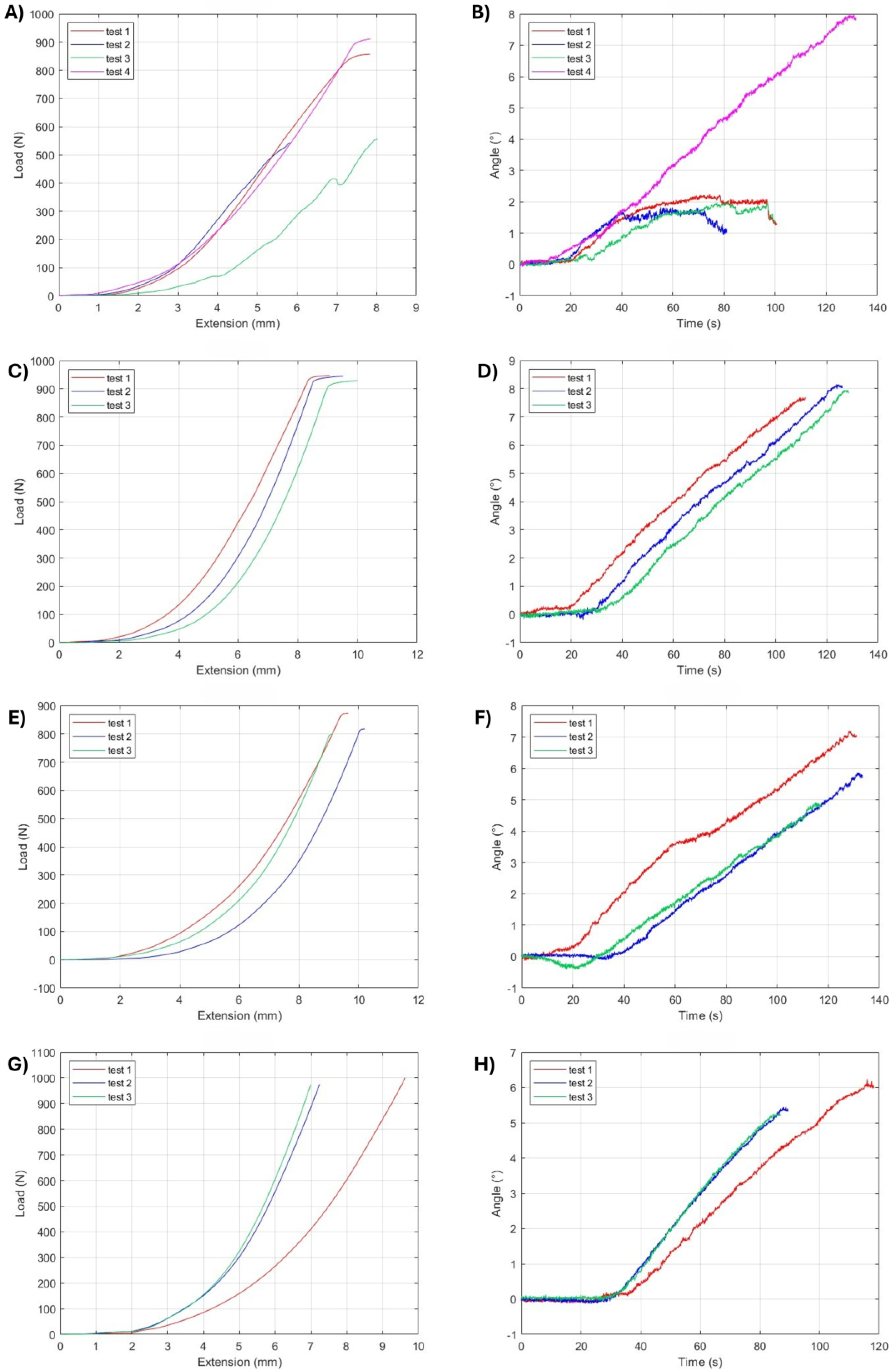

Specimens 2 to 5 (Forelimb, Repeated Freeze–Thaw) demonstrated more regular mechanical behaviour compared to Specimen 1. The load–displacement curves (

Figure 3) and corresponding time–angle curves (

Figure 3) showed a progressive increase in load and medio-lateral bending angle with displacement. Except for two tests on Specimen 2 that were prematurely terminated due to slippage, the remaining tests on Specimen 2 and all tests on Specimens 3, 4, and 5 were completed until a plateau appeared in the load–displacement curve. The experimentally observed plateau is attributed to the testing configuration, in which the pivotable loading rod, in combination with the non-planar articular surface, allowed sagittal rotation of the specimen under load.

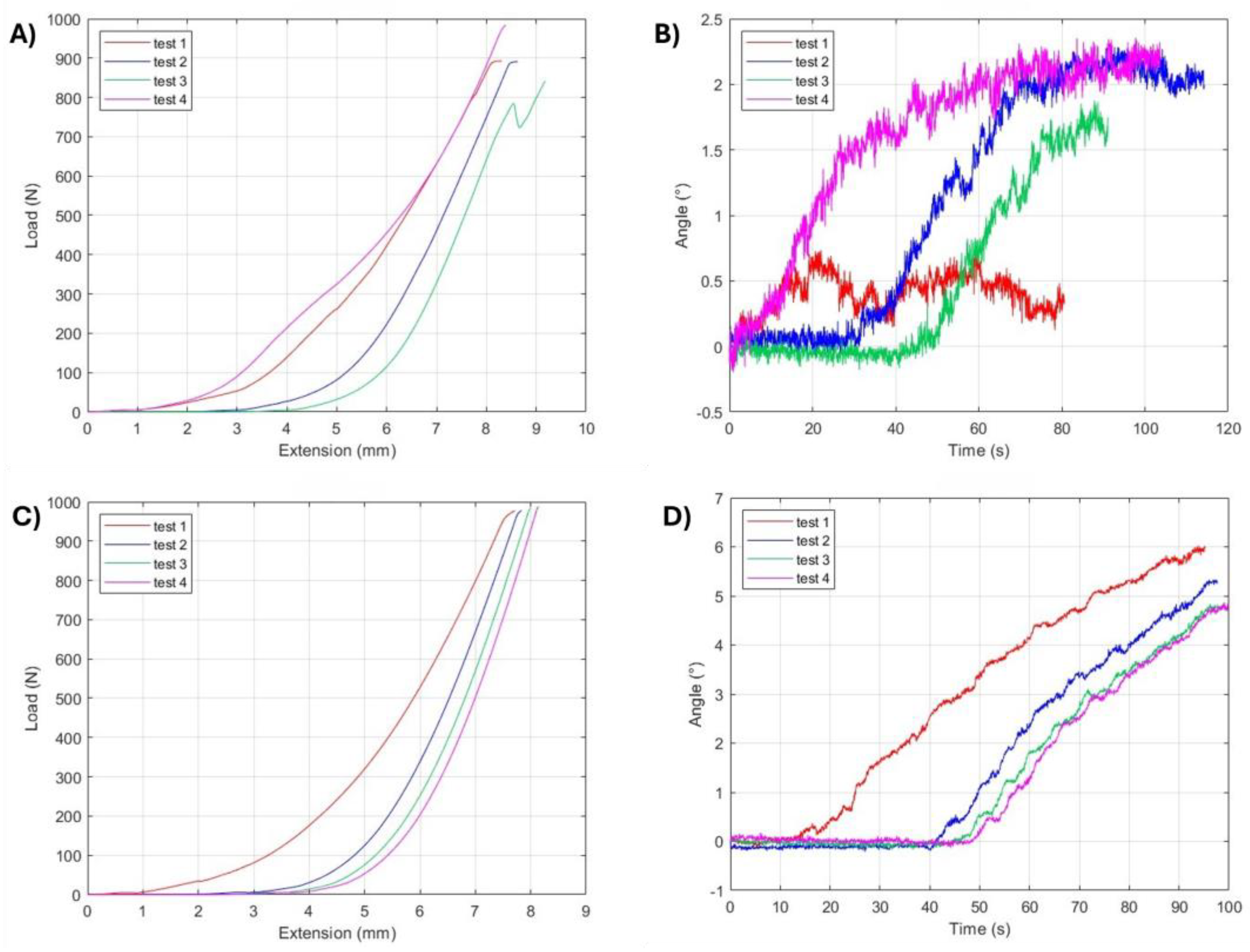

Specimen 6 (Hindlimb, Fresh) displayed a response comparable to that of the previous specimens in the initial tests. The first two tests were terminated upon reaching a load plateau, consistent with the effect of the pivotable loading rod. The third test was terminated due to horizontal slippage. Consequently, a fourth test was conducted using the fixed metallic rod, which prevented premature termination and allowed the trial to proceed until the load approached the 1000 N, limit of the load cell. The load–displacement and time–angle curves for all four tests are shown in

Figure 4A and 4B.

Specimen 7 (Forelimb, Frozen–Thawed) was tested exclusively with the fixed loading tool across four consecutive trials. In all cases, the tests were discontinued as the load approached the 1000 N limit of the load cell, without evidence of slippage or premature plateau formation. The corresponding load–displacement and time–angle curves, which demonstrate high reproducibility across replicates, are presented in

Figure 4C and 4D.

3.2. Joint Mechanical Response

The maximum medio-lateral bending angles, calculated as the deviation from the initial configuration, are shown in

Table 1. For the hindlimb joints, the mean maximum angle was 3.26° for the thawed specimen and 1.97° for the fresh specimen, based on all four tests. Forelimb joints showed greater variation. The mean maximum angles were 3.57° (5.17° when excluding prematurely terminated tests), 8.07°, 6.22°, and 5.76° for joints subjected to repeated freeze–thaw cycles, and 5.42° for the specimen subjected to a single freeze–thaw cycle.

The maximum load values, before the experimentally observed plateau due to rotation of the specimen, and the maximum deflection of the metallic rod recorded during the three-point bending tests are summarised in

Table 2. For the hindlimb joints, the mean maximum load was 978.45 N for the once-thawed specimen and 902.13 N for the fresh specimen. For the forelimb joints, the mean maximum loads were 717.15 N (884.13 N excluding prematurely terminated tests), 940.30 N, 830.01 N, and 982.61 N for specimens subjected to repeated freeze–thaw cycles, and 981.85 N for the once-thawed specimen. Although the loads recorded for the forelimb joints were lower than those of the hindlimb joints, this difference was not statistically significant.

The mean maximum displacement for hindlimb joints was 8.76 mm for the thawed specimen and 8.63 mm for the fresh specimen. The mean maximum displacement for forelimb joints was 7.39 mm, 9.53 mm, 9.67 mm, and 7.96 mm for joints subjected to repeated freeze–thaw cycles, and 7.92 mm for the once-thawed specimen.

Overall, the results indicate that hindlimb proximal interphalangeal joints exhibited greater strength compared to forelimb joints. The greater mobility of the forelimb joints is consistent with their lower stiffness, which may explain the reduced strength observed in our tests. Furthermore, no significant differences were observed between fresh and thawed specimens, or between those subjected to repeated freeze–thaw cycles and those thawed only once.

4. Discussion

Characterizing the tensile mechanical properties of tendon and ligaments is important for the assessment of functional health and efficacy of treatment for acute and chronic injuries. Guidelines for ex-vivo mechanical testing of tendons are well described [

30], however no data exist across laboratories concerning ex-vivo mechanical assessment of collateral ligaments stabilizing diarthrodial joints. Ex-vivo mechanical testing of tendon sutures involves surgically repairing a cut tendon in a lab setting and then using a testing machine by traction to pull it to failure. However, this method of measure the force required for failure is not appliable to evaluate the performance of a repaired collateral ligament since these structures are not subjected only to tensile forces.

The initial objective of this study was to develop a three-point bending setup for ex-vivo characterize mechanical behaviour of the collateral ligaments in the equine PIPJ. The primary goal of this study was to obtain reproducible and meaningful data to assess the PIPJ medio-lateral bending resistance when the medial and lateral collateral ligaments are intact, establishing a baseline for future comparisons with joints subjected to surgical repair techniques of the collateral ligaments. The primary objective of the study is to simulate in a convenient specimen the extra sagittal bending forces which determine the abduction/adduction of the PIPJ in presence of competent and intact collateral ligaments.

The results demonstrated good repeatability in terms of applied displacement, recorded load, and calculated medio-lateral bending angle. The use of a 1000 N load cell provides a non-destructive operational investigation range without signal saturation. In this study we cannot provide data on collateral ligament overstrain because we are not able to cause collateral ligament failure in the equine PIPJs with the 1000 N load cell. However, we can determine the biomechanical behaviour of the collateral ligaments of the PIPJ during joint abduction/adduction. Surprisingly, our result concerning the range of motion of the PIPJ are consistent with recent in vivo data registered in the equine PIPJ in motion, where it was observed that the contribution of the PIPJ to abduction/adduction is 3 +/- 1 degrees at walk and trot [

31].

A key aspect of the experiment set-up was the use of custom 3D-printed resin supports. These fixtures, designed to fit both the testing machine and the geometry of the bone segments, played a crucial role in ensuring specimen stability during testing. They minimized unwanted movements such as horizontal slippage and sagittal rotation, thereby improving measurement accuracy and enhancing reproducibility across subsequent tests. In addition, the use of a fixed loading rod, rather than a pivotable one, further reduced the occurrence of joint rotation under load.

The application of markers on the specimens and the implementation of a custom MATLAB script allowed accurate determination of the joint bending angle during testing, tracking its progression over time. This approach demonstrated adequate precision to detect small angular deflections.

The acquired data, displacement, force, and bending angle, were analysed separately for forelimb and hindlimb joints. The results showed good consistency within each anatomical group. The experimental data indicated greater mobility in forelimb joints, which exhibited mean maximum bending angles of up to 8.07°, compared to a maximum of 3.26° in hindlimb joints. This greater deformability was supported by the recorded load values, with the lower stiffness of the forelimb joints accounting for their reduced strength during testing.

Future studies could benefit from an increased sample size to improve the statistical significance of the results and reduce the uncertainty associated with inter-individual variability. A larger cohort would allow for more precise identification of differences between the two anatomical subgroups.

The experimental phase included only one fresh limb specimen, with results compared to those from specimens subjected to one or multiple freeze–thaw cycles. Although no significant differences were observed in this specific case, a single fresh sample is insufficient to draw definitive conclusions regarding the potential influence of thermal cycling on joint mechanical properties. Since freezing and thawing processes can affect the ligament stiffness, strength, and viscoelasticity of soft tissues, future studies should include a greater number of fresh specimens to allow a robust comparison with freeze–thawed samples.

In conclusion, the results of this preliminary study indicate that the experimental set-up for three-point bending of joints provides a reliable and repeatable framework for the quantitative evaluation of the biomechanical behaviour of the collateral ligaments of the equine PIPJ. The system proved effective in analysing joints with healthy collateral ligaments, laying the foundation for future comparative studies applying the same protocol to joints undergoing collateral ligament repair techniques.

5. Conclusions

The developed three-point bending test setup provides a method for the quantitative biomechanical assessment of the collateral ligament of the equine PIPJ. The custom-designed setup, incorporating 3D-printed fixtures and marker-based video analysis, proved to be a reproducible approach for characterizing the joint’s mechanical behaviour in the medio-lateral plane.

This study established baseline data for healthy joints, revealing a statistically significant difference in mechanical response between forelimbs and hindlimbs.

The implemented test represents the first experimental attempt to evaluate the mechanical stability of both healthy and surgically repaired joints using a three-point bending test. This comparison, which can be extended in subsequent studies to larger sample sizes and different clinical conditions, could provide essential insights into the strength and functionality of joint repairs, with potential applications not only in veterinary medicine but also in human orthopaedics.

Author Contributions

Silvia Mattiussi: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Vito Burgio: Review & editing, Visualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Martina Di Giacinti: Review & editing, Visualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Sofia Bertolino: Review & editing, Investigation, Visualization, Methodology. Marcello Pallante: Review & editing, Visualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Cecilia Surace: Review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Methodology. Andrea Bertuglia: Writing – original draft, Review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Funding acquisition.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PIPJ |

Proximal Interphalangeal Joint |

|

DIPJ

|

Distal Interphalangeal Joint

|

References

- Denoix, J .- M. (1990) Examen radiographique de l'articulation interphalangienne proximale. Prat. vét. Equine, 22, 59-72.

- Riemersma, D. J., van den Bogert, A. J., Schamhardt, H. C., and Hartman, W. (1988). Kinetics and kinematics of the equine hind limb: in vivo tendon strain and joint kinematics. American journal of veterinary research, 49, 1353-1359. [CrossRef]

- Jansen, M. O., Van Buiten, A., Van den Bogert, A. J., and Schamhardt, H. C. (1993). Strain of the musculus interosseus medius and its rami extensorii in the horse, deduced from in vivo kinematics. Acta Anat., 147, 118-124. [CrossRef]

- Drevemo, S., Johnston, C., Roepstorff, L., and Gustås, P. (1999). Nerve block and intra-articular anaesthesia of the forelimb in the sound horse. Equine Veterinary Journal, 30, 266-269. [CrossRef]

- Roepstorff, L., Johnston, C., and Drevemo, S. (1999). The effect of shoeing on kinetics and kinematics during the stance phase. Equine Veterinary Journal, 30, 279-285. [CrossRef]

- Caudron, I., Grulke, S., Farnir, F., Aupaix, R., and Serteyn, D. (1998). Radiographic assessment of equine interphalangeal joints asymmetry: articular impact of asymmetric bearings (Part II). Journal of Veterinary Medicine Series A, 45, 327-335. [CrossRef]

- Denoix, J. M. (1993). Biomécanique interphalangienne dans les plans sagittal et frontal. In Proceedings du Congrès de médecine et de chirurgie équine et du Congrès de l'association mondiale des vétérinaires équins, Genève, 3, 44-49.

- Clayton, H. M., Sha, D. H., Stick, J. A., and Robinson, P. (2007). 3D kinematics of the interphalangeal joints in the forelimb of walking and trotting horses. Veterinary and Comparative Orthopaedics and Traumatology, 20, 01-07. [CrossRef]

- Chateau, H., Degueurce, C., Jerbi, H., Crevier-Denoix, N., Pourcelot, P., Audigié, F., Pasqui-Boutard V and Denoix, J. M. (2002). Three-dimensional kinematics of the equine interphalangeal joints: articular impact of asymmetric bearing. Veterinary Research, 33(4), 371-382. [CrossRef]

- Balch, O., White, K., Butler, D., & Metcalf, S. (1995). Hoof balance and lameness: improper toe length, hoof angle, and mediolateral balance. Comp. Cont. Educ. Pract., 17, 1275-1283.

- Barone, R. (2000). Articulations interphalangiennes. Anatomie des mammifères domestiques, 2, 204-221.

- Rooney, J. R. (1969). Lameness of the forelimb. Biomechanics of lameness in horses. Williams and Wilkins Co., Baltimore, 133-150.

- Dyson, S. (1999). Clinical aspects of disease of the proximal and distal interphalangeal joints. In Proceedings of Congress of Equine Medicine and Surgery, Geneva, Switzerland, 65-66.

- Hertsch, B., and Beerhues, U. (1988). Der Wendeschmerz als Symptom bei der Lamheitsuntersuchung des Pferdes-Pathomorphologische, röntgenologische und kinische Untersuchungen. Pferdeheilkunde, 4, 15-22.

- Denoix, J. M. (1994). Functional anatomy of tendons and ligaments in the distal limbs (manus and pes). Veterinary Clinics of North America: Equine Practice, 10, 273-322. [CrossRef]

- Degueurce C, Chateau H, Jerbi H, Crevier-Denoix N, Pourcelot P, Audigié F, Pasqui-Boutard V, Geiger D, and Denoix JM. (2001). Three-dimensional kinematics of the proximal interphalangeal joint: effects of raising the heels or the toe. Equine Veterinary Journal, 33(S33), 79-83. [CrossRef]

- Caston, S., McClure, S., Beug, J., Kersh, K., Reinertson, E., and Wang, C. (2013). Retrospective evaluation of facilitated pastern ankylosis using intra-articular ethanol injections: 34 cases (2006–2012). Equine veterinary journal, 45, 442-447. [CrossRef]

- Watts, A. E., Fortier, L. A., Nixon, A. J., and Ducharme, N. G. (2010). A technique for laser-facilitated equine pastern arthrodesis using parallel screws inserted in lag fashion. Veterinary Surgery, 39, 244-253. [CrossRef]

- Knox, P. M., and Watkins, J. P. (2006). Proximal interphalangeal joint arthrodesis using a combination plate-screw technique in 53 horses (1994–2003). Equine veterinary journal, 38, 538-542. [CrossRef]

- Wolker, R. R., Wilson, D. G., Allen, A. L., and Carmalt, J. L. (2011). Evaluation of ethyl alcohol for use in a minimally invasive technique for equine proximal interphalangeal joint arthrodesis. Veterinary surgery, 40, 291-298. [CrossRef]

- Martin, G. S., McIlwraith, C. W., Turner, A. S., Nixon, A. J., and Stashak, T. S. (1984). Long-term results and complications of proximal interphalangeal arthrodesis in horses. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 184, 1136-1140. [CrossRef]

- Leppänen, O. V., Sievänen, H., and Järvinen, T. L. (2008). Biomechanical testing in experimental bone interventions—May the power be with you. Journal of biomechanics, 41, 1623-1631. [CrossRef]

- Prodinger, P. M., Foehr, P., Bürklein, D., Bissinger, O., Pilge, H., Kreutzer, K., von Eisenhart-Rothe R., and Tischer, T. (2018). Whole bone testing in small animals: systematic characterization of the mechanical properties of different rodent bones available for rat fracture models. European journal of medical research, 23, 8. [CrossRef]

- Ekeland, A., Engesæter, L. B., and Langeland, N. (1981). Mechanical properties of fractured and intact rat femora evaluated by bending, torsional and tensile tests. Acta Orthopaedica Scandinavica, 52, 605-613. [CrossRef]

- Prof. Ferretti, J. L., Capozza, R. F., Mondelo, N., and Zanchetta, J. R. (1993). Interrelationships between densitometric, geometric, and mechanical properties of rat femora: inferences concerning mechanical regulation of bone modeling. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, 8, 1389-1396. [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z., Tuukkanen, J., Zhang, H., Jämsä, T., and Väänänen, H. K. (1994). The mechanical strength of bone in different rat models of experimental osteoporosis. Bone, 15, 523-532. [CrossRef]

- Raab, D. M., Smith, E. L., Crenshaw, T. D., and Thomas, D. P. (1990). Bone mechanical properties after exercise training in young and old rats. Journal of applied physiology, 68, 130-134. [CrossRef]

- Turner, C. H., and Burr, D. B. (1993). Basic biomechanical measurements of bone: a tutorial. Bone, 14, 595-608. [CrossRef]

- Osuna, L. G. G., Soares, C. J., Vilela, A. B. F., Irie, M. S., Versluis, A., and Soares, P. B. F. (2020). Influence of bone defect position and span in 3-point bending tests: experimental and finite element analysis. Brazilian Oral Research, 35, e001. [CrossRef]

- Lake SP, Snedeker JG, Wang VM, Awad H, Screen HRC, Thomopoulos S. Guidelines for ex vivo mechanical testing of tendon. J Orthop Res. 2023 Oct;41(10):2105-2113. [CrossRef]

- Clayton HM, Sha DH, Stick JA, Robinson P. 3D kinematics of the interphalangeal joints in the forelimb of walking and trotting horses. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol. 2007;20(1):1-7. [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).