1. Introduction

Ankle fractures are among the most common injuries affecting the lower limb [

1]. The annual incidence of these fractures has been estimated at approximately 200 cases per 100,000 person-years [

2,

3], but international trends suggest that ankle fracture rates will continue to rise due to an aging population. Ankle fractures account for about 10% of all musculoskeletal injuries [

4,

5] and more than half of all foot and ankle injuries [

4,

5,

6]. Within this context, isolated malleolar injuries constitute two-thirds of all ankle fractures [

1,

4,

5]. Danis-Weber type B fractures represent the most common form of distal fibular fractures; they typically result from a supination-external rotation mechanism and are characterized by an oblique fracture line [

9]. While conservative treatment has historically been recommended for isolated fibular fractures without signs of ankle instability, recent trends favor surgical intervention, offering advantages in terms of anatomic restoration and earlier recovery [

10]. However, operative management of these fractures is associated with potential complications, including non-union, malunion, post-traumatic osteoarthritis, and skin-related issues such as delayed wound healing or plate exposure [

11].

Established operative management of an unstable fibular fractures treated by open reduction and Internal Fixation (ORIF) or casting could require at least 6 weeks of non-weight bearing. Protracted immobilization is both damaging to the patient and the healthcare system, due to possible post operative complication like joint rigidity and delay for returning to daily work. However, some recent clinical studies have demonstrated that rapid mobilization and early weight-bearing with ankle fractures significantly improved short-term outcomes [

12]. In fact, it was observed that the ability to immediately weight bear post-operatively is associated with shorter inpatient stays with no increased risk of complications and faster consolidation. However, this approach must be carefully considered based on fracture morphology, initial stability, patient age, and comorbidities.

The purpose of this brief report is to analyze whether the use of a new narrow locking plate system can be a safe treatment option for isolated fibular fractures.

2. Materials and Methods

In this study, we enrolled all patients who underwent surgery for distal fibular fractures at our level-one trauma center after January 2020. The inclusion criteria comprised Danis-Weber type B fibular fractures with displacement greater than 2 mm, shortening or rotation. All these fractures were treated using the narrow Newclip Technics distal fibula locking plates (ACTIV ANKLE). Only patients with closed growth plates (defined by a minimum age of 16 years) and a minimum follow-up of twelve months were included in the study.

We excluded cases of undisplaced Danis-Weber type B fibular fractures that were managed with simple immobilization, as well as cases involving open fractures or medial injuries requiring additional transyndesmotic screw fixation or deltoid ligament repair.

Preoperative patient characteristics, including age, sex, body mass index, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score, operative time and length of hospital stay after surgery were recorded (

Table 1).

2.1. Surgical Procedure

Patients were positioned supine on a radiolucent operating table under either general or spinal anesthesia. A pneumatic tourniquet was applied to the proximal thigh and inflated to 280 mmHg after exsanguination. All surgical procedures were performed via a lateral approach. Following manual traction for fracture reduction, we temporarily stabilized the oblique fracture by compressing the fracture site using a reduction clamp. An interfragmentary lag screw was used only once. All patients were treated with the narrow Newclip plates (ACTIVE ANKLE), which were provided as single-use sterile kits. These plates come in two sizes: size 1 with seven holes (76 mm in length) and size 2 with nine holes (102 mm in length). Both kits included standard 3.5 mm cortical screws and either 3.5 mm or 2.8 mm locking screws.

In all cases, at least three distal 2.7 mm unicortical locking screws were utilized. Proximally, a combination of cortical and locking screws was employed based on the surgeon’s judgment. Closed suction drainage was placed in all cases. Subcutaneous tissue was closed using synthetic absorbable interrupted sutures, while skin closure was achieved with either surgical staples or non-absorbable monofilament sutures. After fracture fixation, ankle stability was assessed under fluoroscopic control. An external rotation force was applied to the foot, and the ankle was evaluated for “talar shift”, which indicates opening of the medial clear space between the talus and the medial malleolus. Additionally, the fibula “hook-test” was performed to assess syndesmotic stability [

13]. Patients exhibiting persistent instability during the intraoperative “hook-test” following distal fibular fixation were either managed with a transyndesmotic screw or underwent deltoid ligament repair. Such cases were subsequently excluded from the study.

2.2. Patient Evaluation

Following surgery, the ankle joint was maintained in a neutral position using a short-leg splint. Starting from the second day postoperatively, patients initiated active ankle range of motion (ROM) exercises and progressive weight-bearing, restricted to 20 kg, for a duration of 3 weeks. A bivalve ankle brace and crutches were utilized during this period. After three weeks, patients discontinued the use of braces and crutches. Subsequently, patients underwent follow-up evaluations at 6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months postoperatively.

The follow-up assessments encompassed both clinical and radiological evaluations. To assess lower extremity and ankle function, we employed the Foot and Ankle Outcome Score (FAOS) [

14], which consists of five subscales ranging from 0 to 100 (higher scores indicating better function). Additionally, we utilized the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) to evaluate pain (scores ranging from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating more severe pain or dysfunction) [

15].

Postoperative X-rays were carefully evaluated to detect bony healing, identify any secondary loss of reduction, and assess for potential mechanical failure of the implant. We considered fracture union achieved when the fracture line had disappeared. According to Mendelsohn [

16], non-union was defined as the persistence of a fracture line at least two to three millimeters wide with sclerosing fracture surfaces, observed at least six months after the initial fracture.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Continuous data were expressed as means, whereas categorical and ordinal data were expressed as absolute values and percentages. All analyses were performed with SPSS v. 22.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) and Microsoft Excel v. 16.30 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA).

3. Results

A total of 17 patients met the study’s inclusion criteria. All successfully completed the partial weight-bearing program. However, two patients were lost to follow-up after the three-month assessment and did not participate in the twelve-month clinical and radiographic evaluations. Consequently, data from fifteen patients were available for all follow-up examinations.

The mean age of the cohort was 41 years (ranging from 18 to 64). Among the participants, 4 were women and 11 were men. The average body mass index (BMI) was 23 kg/m

2 (with a range of 18–29 kg/m

2). One patient was classified as ASA class 3, while three were ASA class 2; the remaining patients were ASA class 1. The average surgical duration was 40 minutes (ranging from 30 to 65 minutes), and the mean postoperative hospitalization time was 2.6 days (with a range of 1 to 5 days). See

Table 1.

Minor complications were observed in two cases, characterized by swelling and redness at the wound site at the 6 weeks assessment.

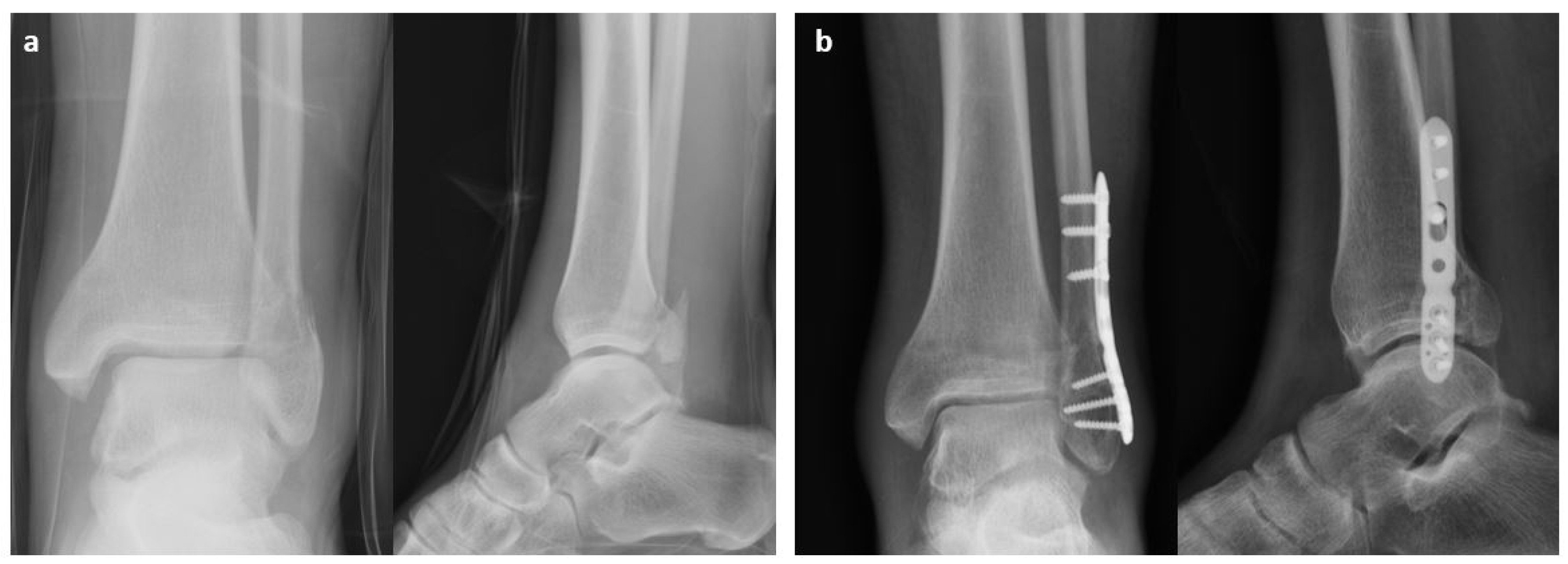

At final follow-up, 12 months after surgery, complete osseous healing was observed in all patients (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2).

All patients but one reported a complete consolidation at the 3 months follow-up; the persistence of fracture line disappeared at the next follow-up (six months after surgery) (

Figure 3). However, it was not associated with any symptoms and the patient had been walking with free weight bearing after 5 weeks from surgery.

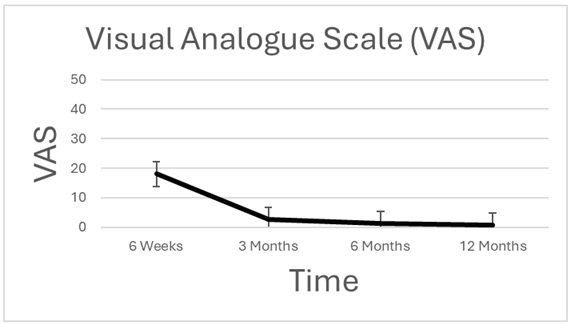

The Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) score demonstrated a progressive reduction during the initial 6-week post-treatment period, with nearly complete pain resolution after three months. (

Table 2).

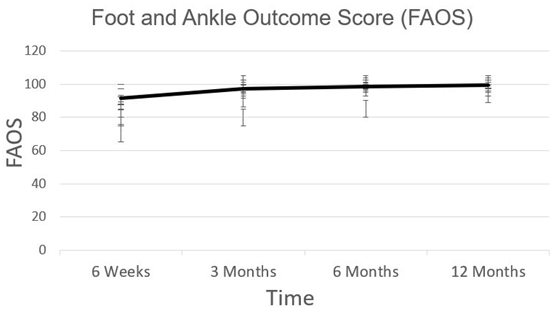

At three months FAOS Score was 100 for 11 patients, 3 with 97 and 2 with 94 points. (

Table 3).

Excellent results were reported in all cases at six months. No mechanical complication, screws loosening or broken material was reported. No cases of deep infection have been observed. None of our patients underwent hardware removal.

4. Discussion

The key finding from this brief is that allowing early postoperative weight-bearing, associated with immediate joint function recovery, is a secure approach for managing uncomplicated unimalleolar ankle fractures classified as Danis-Weber type B. At the three-month assessment post-surgery, all patients exhibited complete consolidation, except for one patient who continued remodeling at six months. There were no mechanical complications, loosening screws, or material breakage reported. Additionally, no cases of deep infection were observed. The favorable impact of an earlier return to walking and rapid mobilization has been well-documented even for conservative treatment of such fractures, using either a bivalve pneumatic air stirrup [

17] or a hinged short-leg boot [

18]. Functional treatment has also been supported by improved Visual Analogue Scale scores and total range of motion (ROM) recovery when compared with a brace rather than with a cast after six weeks [

19]. In the literature, there is a not consensus regarding the optimal method for managing lateral malleolus fractures. Surgical intervention for these fractures has been associated with complications such as non-union, mal-union, post-traumatic osteoarthritis, and skin issues ranging from delayed wound healing to plate exposure. Some authors have reevaluated nonoperative approaches if instability is ruled out [

20,

21,

22]. Recently, ankle stress radiographs have gained popularity for assessing ankle stability in cases of isolated lateral malleolar fractures [

23,

24,

25].

Unfortunately, interpreting these tests is not always easy. If a perfect mortise view cannot be obtained with dorsiflexed ankles, identifying relevant landmarks becomes challenging [

26]. The primary concern associated with incorrect non-operative treatment is an increased risk of ankle mortise incongruency, which can lead to secondary surgeries, early post-traumatic osteoarthritis, and compromised function. Consequently, open reduction and internal fixation are commonly recommended for managing unstable isolated fibular Weber B fractures.

Various fixation methods have been proposed for distal fibula fractures, including the use of one-third tubular plates, dynamic compression plates, and locking plates with or without an independent lag screw. Locking malleolar plates have demonstrated improved surgical outcomes when anatomical reduction and appropriate weight-bearing capacity are achieved. Notably, the locking plate has been shown to provide higher shear and rotational stability compared to the neutralization plate in an osteoporotic bone model under physiological loading.

However, in a retrospective study, Schepers et al. [

27] advised against the use of locking plates due to an increased risk of wound complications compared to conventional plates (17.5% vs. 5.5%). This discrepancy is likely related to the thickness and, consequently, the less precontourable nature of some of these systems.

The locking plate utilized in the study features a low-profile design, closely resembling the non-locking tubular plate. However, it incorporates polyaxial locking screws in the epiphysis, allowing for an angular range of 20 degrees. These polyaxial locking holes are strategically positioned in the epiphyseal area, accommodating 2.8 screws. This design facilitates the insertion of at least three epiphyseal screws in diverging or converging directions, optimizing the overall strength of the assembly. Additionally, the diaphyseal portion of the plates can be bent at specific areas to enhance congruence between the plate and the bone.

The primary limitation of this study lies in the small number of enrolled patients and the absence of a control group. Despite these limitations, we are confident that this study represents a crucial step in testing research protocols and provide the groundwork for future research projects.

5. Conclusions

Open reduction and internal fixation are the most common treatment for unstable ankle fractures, which can be achieved thought several fixation methods. The presented study shows that an early weight bearing following osteosynthesis with straight narrow locking plate represent a safe approach which allow for rapid consolidation and limited complication. A well-designed prospective study is needed to confirm our findings.

Author Contributions

DT and CML participated in conceptualization, development of study design, data collection and curation and writing of the original draft. GMo and CD performed formal analysis, participated in writing the original draft; AO and SS participated in review and editing of data and final draft. DT, GMe and CML provide study materials, patients, and settings. They participated in oversight and leadership responsibility for the research activity, planning and execution. GMe participated in project administration, management and coordination responsibility for the research activity. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Since this is a retrospective study, ethical approval was not required by our institution.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lash, N.; Horne, G.; Fielden, J.; Devane, P. Ankle fractures: Functional and lifestyle outcomes at 2 years. ANZ J. Surg. 2002, 72, 724–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, S.L.; Andresen, B.K.; Mencke, S.; Nielsen, P.T. Epidemiology of ankle fractures: A prospective population-based study of 212 cases in Aalborg, Denmark. Acta Orthop. Scand. 1998, 69, 48–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Staa, T.; Dennison, E.; Leufkens, H.; Cooper, C. Epidemiology of fractures in England and Wales. Bone 2001, 29, 517–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White T, Bugler K. Ankle fractures. In: Tornetta P 3rd, Ricci WM, Ostrum RF, et al., editors. Rockwood and Green’s fractures in adults, 9th ed. Vol 2. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer; 2020;2822-76.

- Shibuya, N.; Davis, M.L.; Jupiter, D.C. Epidemiology of Foot and Ankle Fractures in the United States: An Analysis of the National Trauma Data Bank (2007 to 2011). J. Foot Ankle Surg. 2014, 53, 606–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jupiter, D.C.; Hsu, E.S.; Liu, G.T.; Reilly, J.G.; Shibuya, N. Risk factors for short-term complication after open reduction and internal fixation of ankle fractures: Analysis of a large insurance claims database. J. Foot Ankle Surg. 2020, 59, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tile M. Fractures of the Ankle. In: Schatzker J, Tile M, editors. The Rationale of Operative Fracture Care. 2. Berlin: Springer; 1996. pp. 523–561.

- Shaffer, M.A.; Okereke, E.; Esterhai, J.L.; Elliott, M.A.; Walter, G.A.; Yim, S.H.; Vandenborne, K. Effects of Immobilization on Plantar-Flexion Torque, Fatigue Resistance, and Functional Ability Following an Ankle Fracture. Phys. Ther. 2000, 80, 769–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.-M.; Wu, T.-H.; Wen, J.-X.; Wang, Y.; Cao, L.; Wu, W.-J.; Gao, B.-L. Radiographic analysis of adult ankle fractures using combined Danis-Weber and Lauge-Hansen classification systems. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Court-Brown, C.M.; McBirnie, J.; Wilson, G. Adult ankle fractures--an increasing problem? Acta Orthop. Scand. 1998, 69, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyes, M.; Torres, R.; Guillén, P. Complications of open reduction and internal fixation of ankle fractures. Foot Ankle Clin. 2003, 8, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, T.; Farrugia, P. Early versus late weight bearing & ankle mobilization in the postoperative management of ankle fractures: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Foot Ankle Surg. 2022, 28, 827–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gougoulias, N., Sakellariou, A. (2014). Ankle Fractures. In: Bentley, G. (eds) European Surgical Orthopaedics and Traumatology. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

- Roos, E.M.; Brandsson, S.; Karlsson, J. Validation of the Foot and Ankle Outcome Score for Ankle Ligament Reconstruction. Foot Ankle Int. 2001, 22, 788–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, C.R.; Casey, K.L.; Dubner, R.; Foley, K.M.; Gracely, R.H.; Reading, A.E. Pain measurement: an overview. Pain 1985, 22, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendelsohn, H.A. Nonunion of malleolar fracture of the ankle. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1965, 11, 103–118. [Google Scholar]

- Stover, C.N. A Functional Semirigid Support System for Ankle Injuries. Physician Sportsmed. 1979, 7, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brink, O.; Staunstrup, H.; Sommer, J. Stable Lateral Malleolar Fractures Treated with Aircast Ankle Brace and DonJoy R.O.M.-Walker Brace: A Prospective Randomized Study. Foot Ankle Int. 1996, 17, 679–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Berg, C.; Haak, T.; Weil, N.L.; Hoogendoorn, J.M. Functional bracing treatment for stable type B ankle fractures. Injury 2018, 49, 1607–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donken C, Al-Khateeb H, Verhofstad MHJ, van Laarhoven C. Surgical versus.

- conservative interventions for treating ankle fractures in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;8.

- Gougoulias N, Sakellariou A. When is a simple fracture of the lateral malleolus.

- not so simple? How to assess stability, which ones to fix and the role of the deltoid ligament. Bone Joint J. 2017;99-B(7):851–855.

- Aiyer, A.A.; Zachwieja, E.C.; Lawrie, C.M.; Kaplan, J.R.M. Management of Isolated Lateral Malleolus Fractures. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2019, 27, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnell T, Creevy W, Tornetta P 3rd: Stress examination of supination external rotation-type fibular fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004.

- Schock, H.J.; Pinzur, M.; Manion, L.; Stover, M. The use of gravity or manual-stress radiographs in the assessment of supination-external rotation fractures of the ankle. J Bone Joint Surg. Br. 2007, 89, 1055–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidel A, Krause F, Weber M: Weightbearing vs gravity stress radiographs for stability evaluation of supination-external rotation fractures.

- Zeni, F.; Cavazos, D.R.; Bouffard, J.A.; Vaidya, R.; Bouffard, J.A. Indications and Interpretation of Stress Radiographs in Supination External Rotation Ankle Fractures. Cureus 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schepers, T.; Van Lieshout, E.; De Vries, M.; Van der Elst, M. Increased rates of wound complications with locking plates in distal fibular fractures. Injury 2011, 42, 1125–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).