1. Introduction

Lisfranc injuries, involving the tarsometatarsal joint, represent a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge in orthopedic practice [

1]. These injuries, first described by Jacques Lisfranc in the Napoleonic era, are uncommon but carry significant clinical implications, including chronic pain, impaired mobility, and post-traumatic osteoarthritis when left untreated or improperly managed [

2,

3].

The Lisfranc joint, anatomically and functionally unique, plays a critical role in maintaining the foot’s longitudinal arch and overall stability [

4]. Anatomically, the wedge-shaped base of the second metatarsal serves as a keystone within the tarsometatarsal complex, interacting with the cuneiform bones to ensure structural integrity. Functionally, this configuration enables load distribution across the foot during weight-bearing activities [

1].

Despite advances in imaging techniques, approximately 20% of Lisfranc injuries remain undiagnosed in emergency settings, particularly in polytrauma patients [

5,

6]. High-energy trauma, whether direct (e.g., crush injuries) or indirect (e.g., hyperflexion injuries), is the primary mechanism [

7,

8]. Early recognition and intervention are critical to preventing long-term complications such as instability and arthritis [

9,

10].

Treatment strategies range from conservative approaches, such as immobilization, to surgical interventions, including open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) or stabilization with Kirschner wires (K-wires) [

11]. While screw fixation offers superior biomechanical stability, K-wire fixation is less invasive and has shown comparable outcomes in certain scenarios [

3]. However, the optimal approach remains controversial, particularly in cases of complex fracture-dislocations [

11].

This study aims to evaluate the clinical and radiographic outcomes of Lisfranc injuries treated with K-wire fixation, focusing on long-term results five years post-surgery. By correlating early diagnosis with treatment outcomes, we seek to provide insights into the efficacy of this approach and its role in managing these challenging injuries.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patient Selection

This retrospective study analyzed clinical and radiographic outcomes of patients treated for Lisfranc fracture-dislocations at the Orthopedic Clinic of the University of Catania between May 2017 and May 2021.

Inclusion Criteria:

Patients aged between 18 and 70 years.

Diagnosed with tarsometatarsal fracture-dislocations confirmed by radiographs or CT scans.

Surgical treatment performed within 12 hours of injury.

Exclusion Criteria:

Age <18 or >70 years.

Stage I injuries (as per Vertullo classification).

Open or bilateral fractures.

Aged under 18 or over 80

Extremely comminuted fractures with bone loss

Diabetes

Rheumatoid arthritis

Patients with severe circulatory disorder of the lower limb

A delay in diagnosis

Patients with a previous foot injury or surgery of the injured foot

Pregnancy

Severe circulatory disorders, prior foot injury/surgery, or pregnancy.

2.2. Surgical Technique

All patients underwent either open or closed reduction and stabilization using Kirschner wires (K-wires). Postoperatively, patients were immobilized in a plaster cast and instructed to avoid weight-bearing for five weeks. K-wires were removed after four weeks, and progressive weight-bearing was allowed after 8–12 weeks, depending on healing.

2.3. Follow-Up Protocol

Patients were evaluated at a mean follow-up of 54 months using standardized clinical, functional, radiographic, and baropodometric assessments.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were reported as means (standard deviations) or medians (interquartile ranges) for continuous variables and proportions for categorical variables. Comparisons between groups were performed using:

t-tests for normally distributed variables.

Mann-Whitney U tests for non-parametric comparisons.

Fisher’s exact tests for categorical data.

Primary outcomes included the AOFAS Midfoot Scale, while secondary outcomes included complication rates (e.g., osteoarthritis) and baropodometric parameters. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05, with analyses performed using SPSS version 22.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

A total of 24 patients (18 males, 6 females) with Lisfranc injuries were included in the study. The average age was 45.7 years (range: 23–70). The primary mechanism of injury was high-energy trauma, with 80% caused by direct forces (e.g., crush injuries) and 20% by indirect mechanisms (e.g., hyperflexion). Lesions were classified as follows:

Myerson classification: 8 Type A (totally incongruent), 4 Type B1 (partial medial incongruity), 8 Type B2 (partial lateral incongruity), and 4 Type C (divergent).

Vertullo classification: 17 Stage II and 7 Stage III injuries.

3.2. Clinical Outcomes

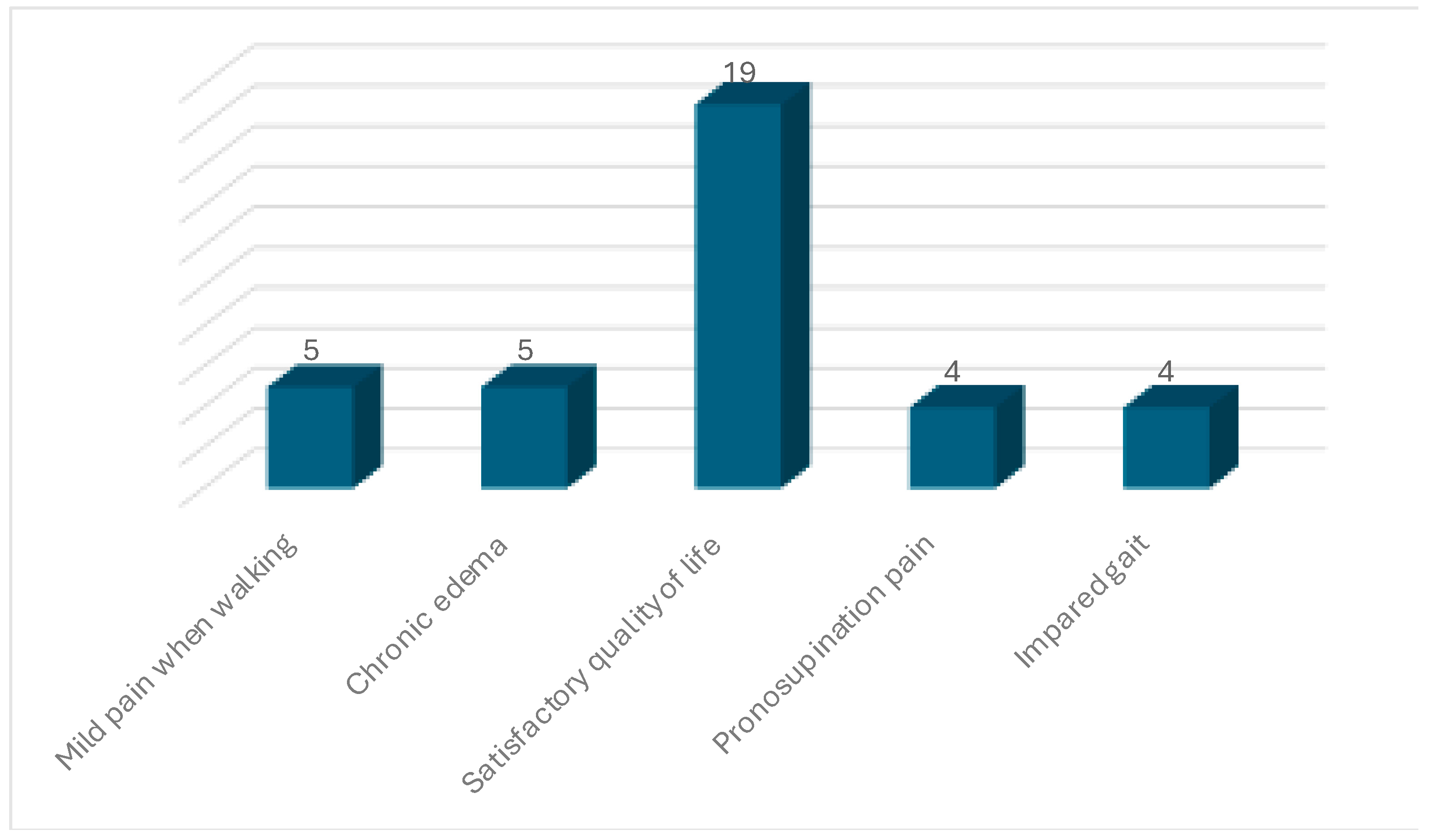

At a mean follow-up of 54 months (

Figure 1):

Mild pain during walking: 5 patients.

Chronic residual edema: 5 patients.

Pain during pronation-supination: 4 patients.

Imparament: 4 patients.

Overall satisfaction: 19 patients reported good quality of life.

Figure 1.

Clinical Outcome.

Figure 1.

Clinical Outcome.

3.3. Functional Outcomes

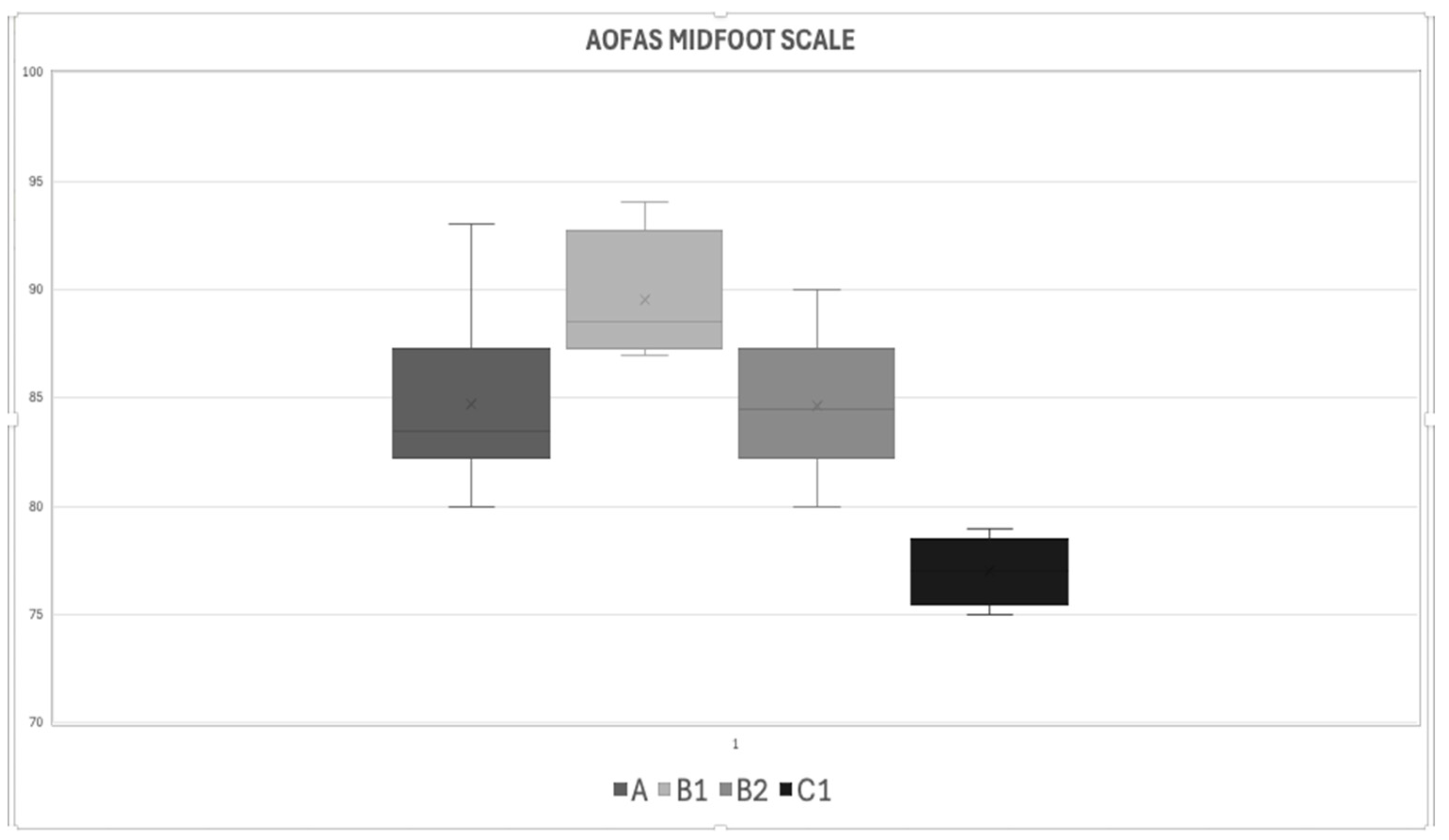

The AOFAS Midfoot Scale showed the following scores:

-

Myerson classification:

- ○

Type A: 84.75 ± 5.8

- ○

Type B1: 89.5 ± 5.3

- ○

Type B2: 84.5 ± 6.2

- ○

Type C: 77 ± 5.5

p-value: 0.0001

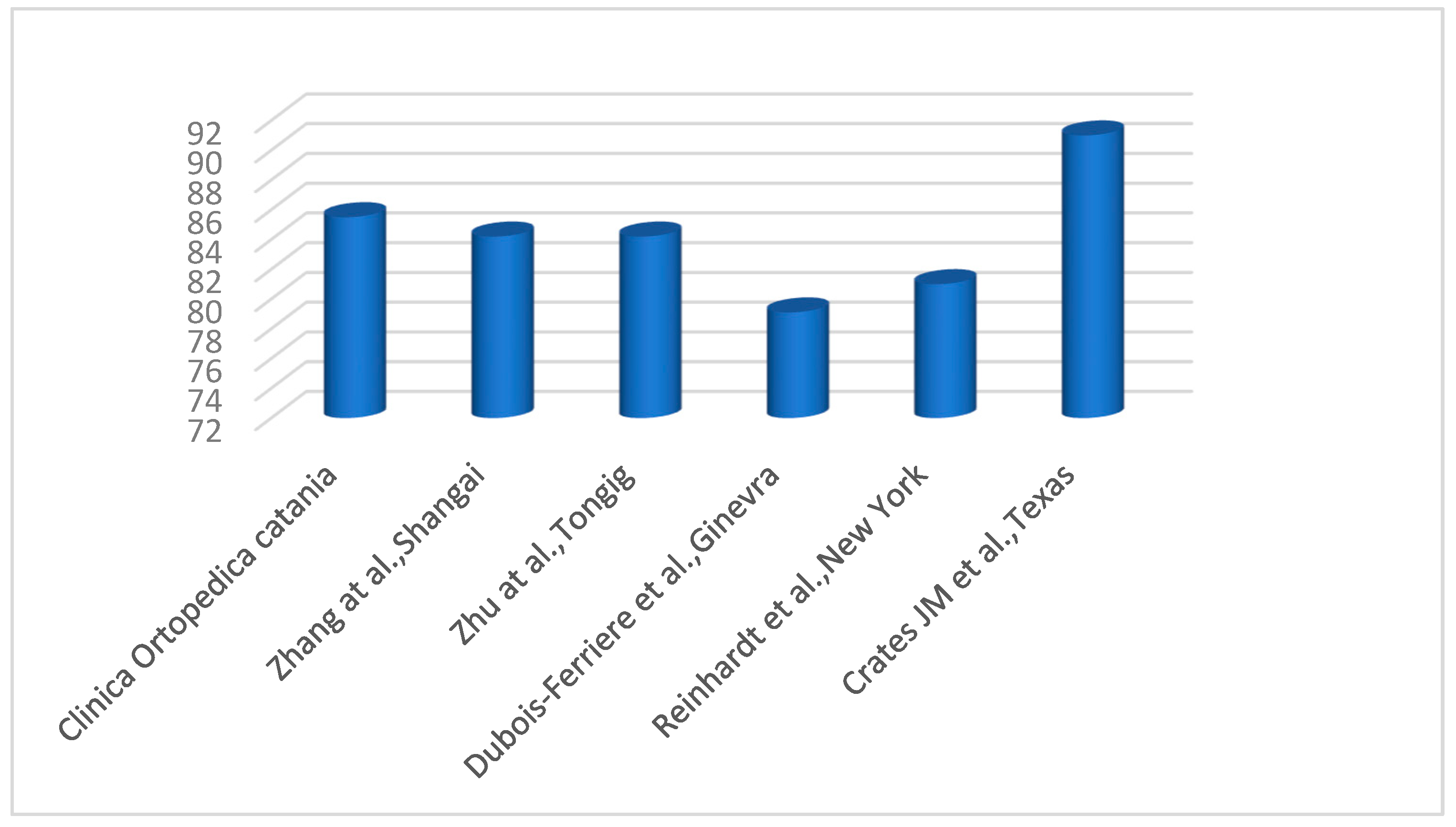

The AOFAS score at 5 years shows a very good average score (range 75-89 points) for all Myerson groups, almost excellent for group B1 (range 90-100) points and an average score of 85,2 ± 5,77 for the 4 groups. The P-Value among ùthe four stages is 0.0001 therefore statistically significant (

Figure 2)

- 2.

-

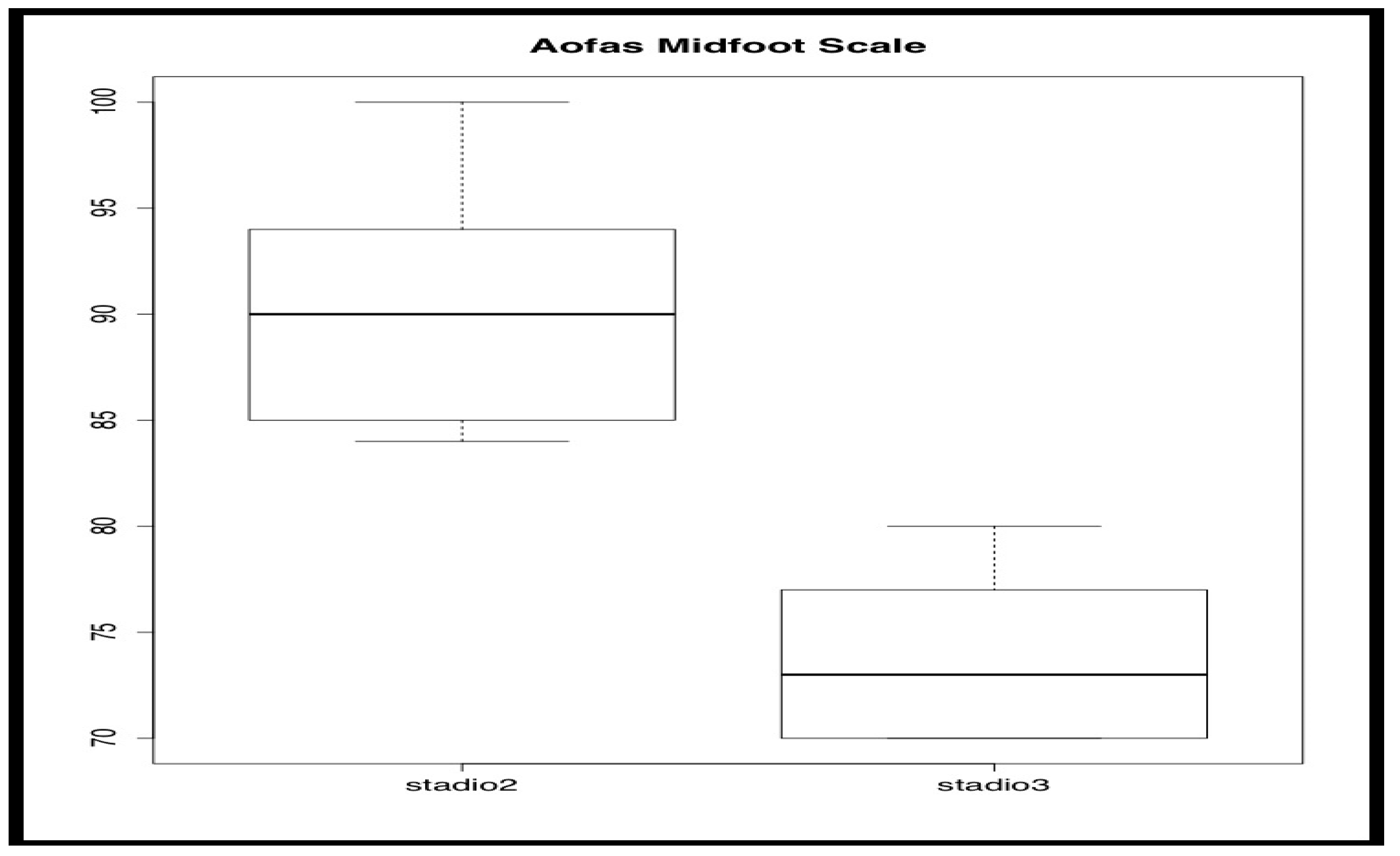

Vertullo classification:

- ○

Stage II: 90.36 ± 4.2 (excellent outcome).

- ○

Stage III: 75 ± 5.1 (good outcome).

p-value: 0.0007

The AOFAF score at 5 years shows an excellent average score for stage II, 90,36 points (range 90-100 points), good for stage III, 75 points (range 75-89 points) (The P-Value between the two stages is 0.00070, therefore statistically significant (

Figure 3).

- 3.

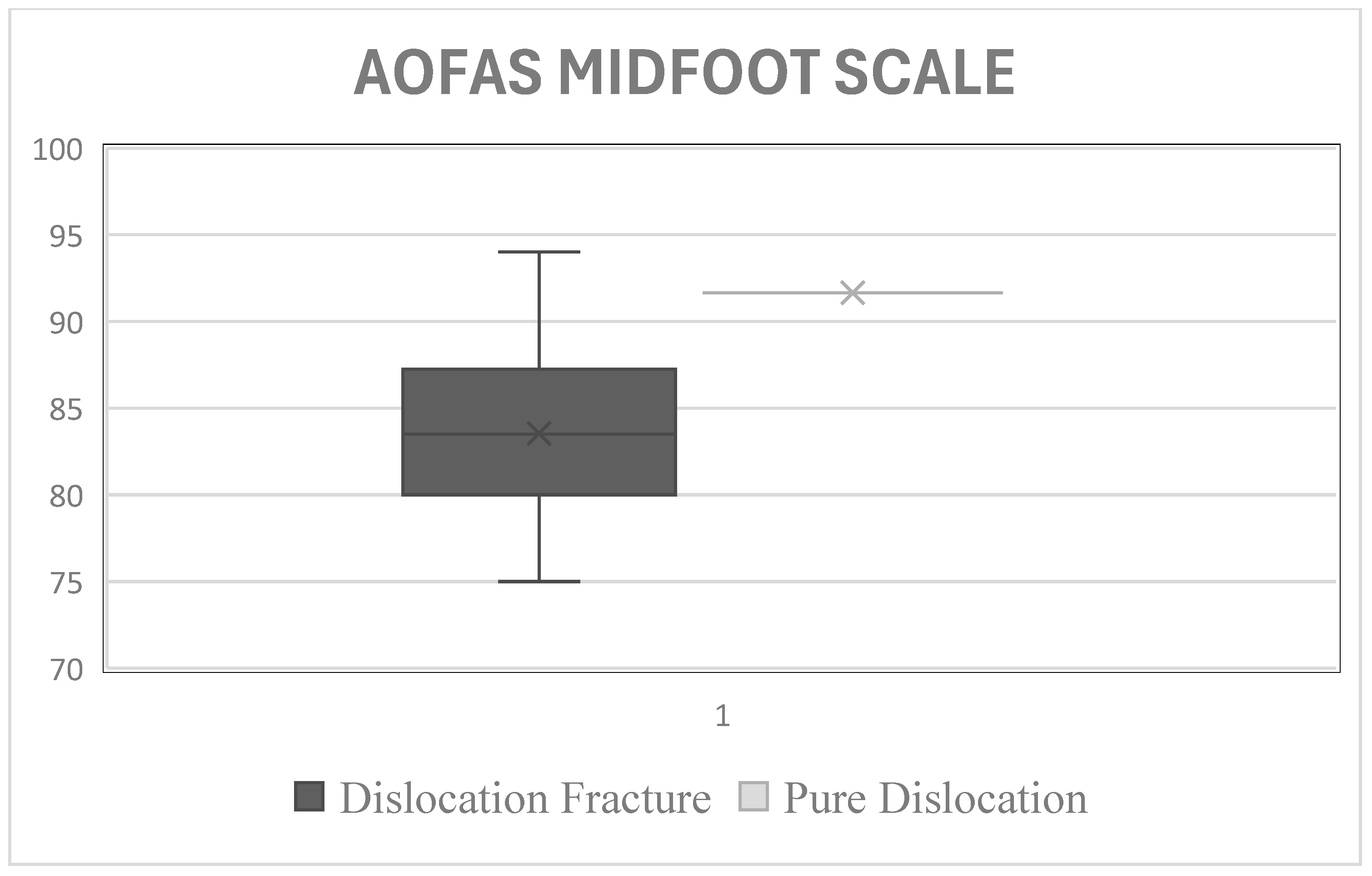

-

Type of injury:

- ○

Pure dislocation: 91.66 ± 3.8 (excellent outcome).

- ○

Dislocation-fracture: 83.5 ± 5.6 (good outcome).

p-value: 0.0371 (statistically significant difference).

The AOFAF score at 5 years shows an excellent average score for the group with pure dislocation, 91,66 points (range 90-100 points), good for for the group with dislocation-fracture, 83,5 points (range 75-89 points). The P-Value between the two stages is 0.0371, therefore statistically significant (

Figure 4).

Figure 2.

AOFAS score according to Myerson classification.

Figure 2.

AOFAS score according to Myerson classification.

Figure 3.

AOFAS score according to Myerson classification.

Figure 3.

AOFAS score according to Myerson classification.

Figure 4.

AOFAS score between pure dislocation group and dislocation fracture group.

Figure 4.

AOFAS score between pure dislocation group and dislocation fracture group.

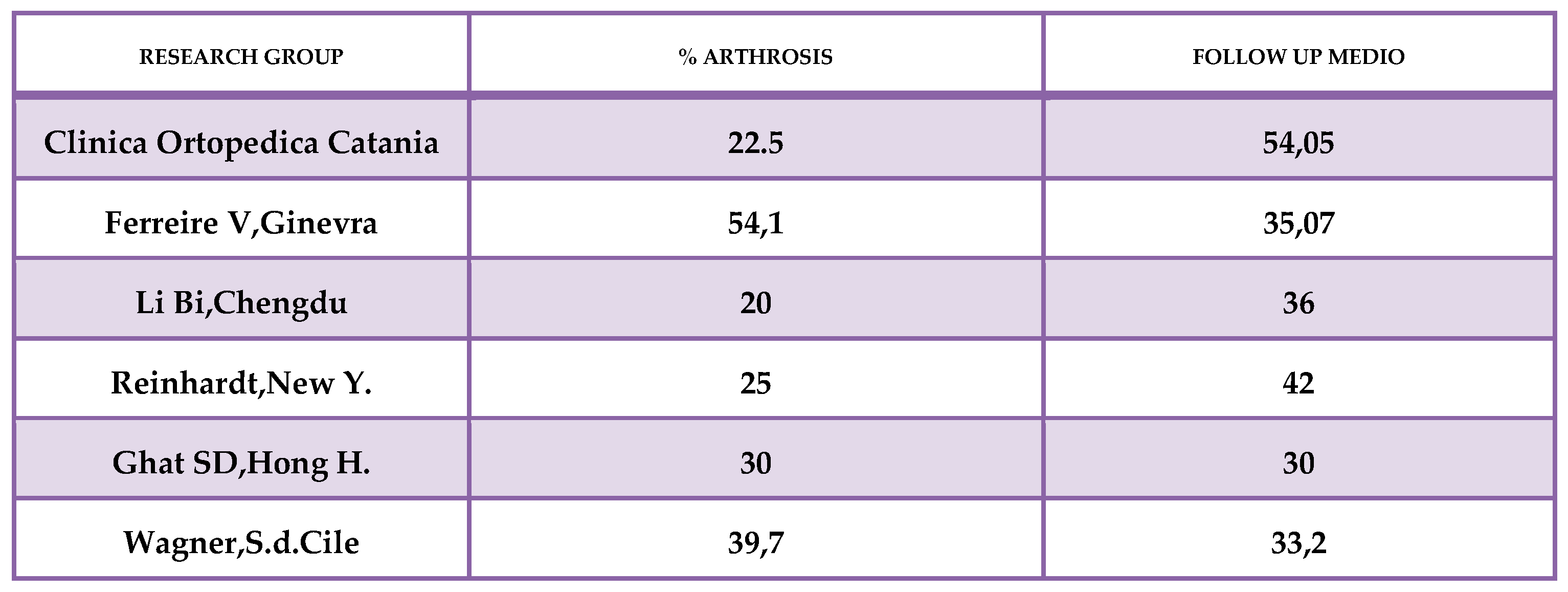

3.4. Radiographic and Baropodometric Outcomes

Radiographic findings: Reduction maintenance was achieved in all but one patient (4.2%). Osteoarthritis was observed in 22.5% of cases (5 patients) (

Figure 5).

-

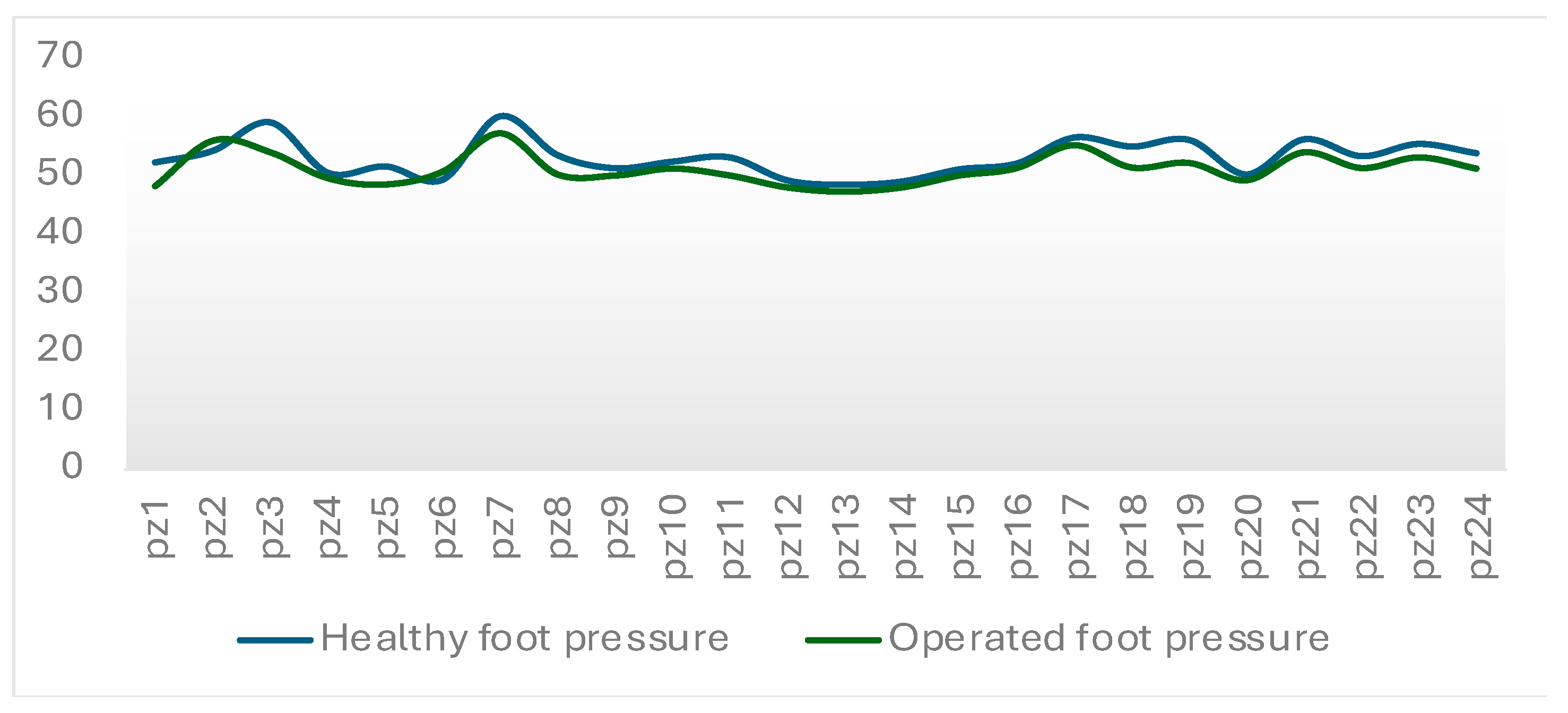

Baropodometric analysis:

- ○

Pressure distribution between the injured and healthy foot was nearly identical in both static and dynamic tests.

- ○

Dynamic parameters (CPEI) confirmed normalized gait patterns in most patients.

On baropodometric examination, the support pressures between the healthyan operated feet are almost overlappin(

Figure 6).

3.5. Comparison with Literature

The average AOFAS score in this study (85.2 ± 5.77) was comparable to the literature values for values for mixed, screw-and-wire approaches of k (

Figure 7):

Clinica Ortopedica Catania: 84.07 ± 11.43.

Ferreire et al.: 82.1 ± 10.2.

Reinhardt et al.: 85.3 ± 9.8.

Wagner et al.: 83.7 ± 10.1.

Figure 7.

Comparison of AOFAS Scores with Literature.

Figure 7.

Comparison of AOFAS Scores with Literature.

3.6. Complications

No cases of infection or hardware failure were reported.

Secondary surgeries, including removal of K-wires, were completed without complications.

4. Discussion

The management of Lisfranc fracture-dislocations remains a challenge in orthopedic practice, with up to 20% of cases being misdiagnosed or diagnosed late, as noted by Rabin (1996) [

12]. Early and accurate diagnosis is critical for improving outcomes, and computed tomography (CT) has been recommended to supplement standard radiographic evaluations. In our study, all patients underwent surgical intervention within six hours of diagnosis, adhering to recommendations emphasizing the prognostic importance of timely treatment and anatomical reduction.

Our findings demonstrated that K-wire fixation can achieve excellent functional outcomes. The mean AOFAS score at 5-year follow-up was 85.2 ± 5.77, aligning with studies by Zhu et al. (2011) [

13] and Zhang et al. (2012) [

14], who reported similar scores for hybrid fixation methods combining screws and K-wires. These results support the use of K-wires as a less invasive alternative to screw fixation, as highlighted by Mascio et al. (2022) [

3].

An important point to highlight is that while K-wires are widely accepted for lateral column stabilization, our study suggests that central and medial columns fractures, if adequately reduced, can also be effectively treated with K-wires. This finding expands the potential applications of K-wire fixation, offering a less invasive option even for complex injuries, provided that the fractures are well-composed [

15]. In the treatment of central and medial columns, our results showed excellent outcomes, with rates of post-traumatic osteoarthritis comparable to those reported in the literature for screw fixation. Importantly, this approach resulted in good clinical outcomes without requiring reoperation for hardware removal. This advantage further highlights the minimally invasive nature of K-wires and their ability to maintain reduction stability while avoiding additional surgical morbidity [

15].

Future research could further validate these observations by comparing the outcomes of central and medial columns fractures treated with K-wires to those treated with screws. Such studies would be valuable in determining whether K-wires provide comparable stability and long-term outcomes while minimizing surgical invasiveness and associated risks [

16].

Baropodometric analysis did not reveal differences in pressure distribution between the operated and healthy feet, indicating a restoration of biomechanical function. These findings are consistent with Reinhardt et al. (2016) [

17], although Dubois-Ferrière et al. (2016) [

18] reported higher rates of osteoarthritis (54%) compared to our 22.5%. This discrepancy may be attributed to differences in surgical technique, patient selection, or follow-up duration.

When outcomes were analyzed according to Myerson’s classification, a statistically significant difference was observed between the groups (p = 0.0001), with Type C1 injuries showing the worst outcomes. Similarly, within the Vertullo classification, fractures classified as Type III Stage C demonstrated the poorest outcomes in our study. This is likely due to the complexity and severity of these injuries, which involve greater displacement and instability, making them more challenging to manage surgically and increasing the risk of long-term complications as well as increased joint damage.

Our results differ from those of Persiani et al. (2019) [

19], who did not find significant differences based on injury type. Furthermore, our data suggest that fractures associated with dislocations lead to worse clinical outcomes compared to pure dislocations, a finding not corroborated by Persiani et al. (2019) [

19].

Despite these promising results, our study has limitations. The retrospective design and relatively small sample size may limit the generalizability of our findings. Another potential limitation is the uniformly prompt surgical intervention in our cohort, which could have positively influenced the outcomes. Early treatment likely minimized complications potentially creating a bias in favor of better results. Future research should expand the sample and include comparative analyses of hybrid fixation techniques to validate these outcomes. Additionally, a prospective approach comparing K-wire fixation with screw fixation for medial and central columns would help clarify the optimal treatment strategy for Lisfranc injuries [

15,

16].

5. Conclusions

Our study demonstrates that K-wire fixation, while traditionally used for lateral column stabilization, can also be effectively applied to central and medial columns fractures, provided that adequate reduction is achieved and that there is no high degree of breakdown or bone loss. This approach offers comparable outcomes to ORIF with transarticular screws, with similar rates of post-traumatic osteoarthritis, considering the considerable advantage of non-reoperation for the removal of synthetic media as is the case for the hybrid technique and further reducing the surgical joint insults that would be added to those resulting from trauma.

By highlighting the potential of K-wires as a less invasive alternative, we aim to expand their application in the management of Lisfranc injuries considering the considerable advantage of non-reoperation for the removal of synthetic media as is the case for the hybrid technique and further reducing the surgical joint insults that would be added to those resulting from trauma. Future research should focus on validating these findings through larger, comparative studies to refine treatment protocols and optimize outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C. and L.C.; methodology, A.C. and M.S.V.; software, M.S.V.; validation, V.P., L.C. and A.C.; formal analysis, M.S.V.; investigation, G.T.; resources, A.C.; data curation, M.S.V. and A.C.; supervision, V.P. and G.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Orthopedic Clinic of the University of Catania.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

No acknowledgments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cassebaum, W.H. Lisfranc Fracture-Dislocations. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1963, 30, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scolaro, J.; Ahn, J.; Mehta, S. Lisfranc Fracture Dislocations. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2011, 469, 2078–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mascio, A.; Greco, T.; Maccauro, G.; Perisano, C. Lisfranc Complex Injuries Management and Treatment: Current Knowledge. Int J Physiol Pathophysiol Pharmacol 2022, 14, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chaney, D.M. The Lisfranc Joint. Clinics in Podiatric Medicine and Surgery 2010, 27, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grewal, U.S.; Onubogu, K.; Southgate, C.; Dhinsa, B.S. Lisfranc Injury: A Review and Simplified Treatment Algorithm. The Foot 2020, 45, 101719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalia, V.; Fishman, E.K.; Carrino, J.A.; Fayad, L.M. Epidemiology, Imaging, and Treatment of Lisfranc Fracture-Dislocations Revisited. Skeletal Radiol 2012, 41, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, J.S.; Anderson, R.B. Lisfranc Injuries in the Athlete. Foot Ankle Int. 2016, 37, 1374–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perron, A.D.; Brady, W.J.; Keats, T.E. Orthopedic Pitfalls in the ED: Lisfranc Fracture-Dislocation. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine 2001, 19, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knipe, H.; Gaillard, F. Lisfranc Injury. Radiopaedia.org, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, S.; Bozin, M.; Thillainadesan, T. Lisfranc Fracture Dislocation: A Review of a Commonly Missed Injury of the Midfoot. Emerg Med J 2017, 34, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moracia-Ochagavía, I.; Rodríguez-Merchán, E.C. Lisfranc Fracture-Dislocations: Current Management. EFORT Open Reviews 2019, 4, 430–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabin, S.I. Lisfranc Dislocation and Associated Metatarsophalangeal Joint Dislocations. A Case Report and Literature Review. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 1996, 25, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.; Zhao, H.; Yuan, F.; Yu, G. [Effective analysis of open reduction and internal fixation for the treatment of acute Lisfranc joint injury]. Zhongguo Gu Shang 2011, 24, 922–925. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Min, L.; Wang, G.-L.; Huang, Q.; Liu, K.; Liu, L.; Tu, C.; Pei, F.-X. Primary Open Reduction and Internal Fixation with Headless Compression Screws in the Treatment of Chinese Patients with Acute Lisfranc Joint Injuries. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 2012, 72, 1380–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethuraman, S.A.; Silverstein, R.S.; Dedhia, N.; Shaner, A.C.; Asprinio, D.E. Radiographic Outcomes of Cortical Screw Fixation as an Alternative to Kirschner Wire Fixation for Temporary Lateral Column Stabilization in Displaced Lisfranc Joint Fracture-Dislocations: A Retrospective Cohort Analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2022, 23, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahluwalia, R.; Yip, G.; Richter, M.; Maffulli, N. Surgical Controversies and Current Concepts in Lisfranc Injuries. British Medical Bulletin 2022, 144, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhardt, K.R.; Oh, L.S.; Schottel, P.; Roberts, M.M.; Levine, D. Treatment of Lisfranc Fracture-Dislocations with Primary Partial Arthrodesis. Foot Ankle Int. 2012, 33, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubois-Ferrière, V.; Lübbeke, A.; Chowdhary, A.; Stern, R.; Dominguez, D.; Assal, M. Clinical Outcomes and Development of Symptomatic Osteoarthritis 2 to 24 Years After Surgical Treatment of Tarsometatarsal Joint Complex Injuries. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 2016, 98, 713–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Persiani, P.; Dario Gurzi, M.; Formica, A.; Ruggeri, A.; Villani, C. Fractures and Dislocations of the Lisfranc Tarso-Metatarsal Articulation: Outcome Related to Timing and Choice of Treatment. Acta Orthop Belg 2019, 85, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).