1. Introduction

”Congenital clubfoot” refers to a group of foot deformities with varying severity that are characterized by a permanent deviation of the anatomical axes of the foot in relation to the leg and to each other. This deviation leads to changes in the normal points of support and foot function [

1]. From the perspective of etiopathogenesis, there are three types of clubfoot: postural (or positional), congenital (or idiopathic), and syndromic (or teratogenic).

Congenital clubfoot is clinically distinct from postural clubfoot (reducible positional defect after birth) in that the foot cannot be manually moved into a normal position. Congenital deformity is evident at birth and is an immediate cause of disability. The generic term “talipes” derives from the Latin words

talus (talus) and

pes (foot) and literally means “to walk on the ankles.” It is important to distinguish between idiopathic clubfoot, which has no specific cause, and syndromic clubfoot, which is associated with pathological conditions (arthrogryposis, congenital muscular dystrophy, spina bifida, myelomeningocele, cerebral palsy, or poliomyelitis). Failure to distinguish them can lead to incorrect classification and treatment [

2].

Also known as idiopathic clubfoot, congenital talipes equinovarus (CTEV) has a global incidence of about 1 per 1000 live births. A recent systematic review based on 48 studies from 20 low- and middle-income countries reported a CTEV prevalence of 0.51 to 2.03/1000 live births [

3]. In approximately half of patients, the anomaly is bilateral, and in cases of unilateral clubfoot, the right side is affected slightly more frequently than the left side [

4]. “Cavus, adductus, varus, equinus” (CAVE) is the most common clinical presentation of clubfoot and accounts for 79% of cases. This variant is characterized by fixed foot positions of cavus (high arch), adductus (inward turning of the forefoot), varus (inward rotation of the heel), and equinus (downward pointing of the toes). These deformities are associated with abnormalities in the ligaments and tendons that lead to medial rotation of certain bones relative to the talus.

The etiology of idiopathic clubfoot remains largely unknown, although it is thought to be multifactorial. Diagnosis is mainly based on clinical examination as the usefulness and seriality of radiographs is limited in the first few months of life due to the presence of non-ossified cartilage. However, ultrasound can provide useful information about the morphology of the foot. The goal of treatment is to obtain a straight, painless, flexible, and normal-looking foot that allows the child to have normal quality of life.

There are several conservative approaches to treating clubfoot, regardless of the degree of deformity. The Ponseti method is a widely used treatment for clubfoot that involves a combination of gentle manipulation, casting, and sometimes minor surgery to correct the deformity. The process begins with serial femoropodal casting, where the foot is gradually corrected through weekly casts. After achieving optimal correction, a percutaneous tenotomy is often performed to release the tight Achilles tendon. Once the foot is corrected, the child must wear a bracing system to prevent recurrence (typically full-time for the first few months and then part-time for several years).

This approach has demonstrated high success rates in correcting deformities associated with clubfoot and achieving good to excellent functional outcomes in children. Treated patients have no limitations in sports or activities and show comparable bilateral results between sexes, as demonstrated by Pavone et al. [

5]. The purpose of this study is to report 10 years of experience at the Orthopedic Clinic of the "G. Rodolico" Hospital of Catania in the treatment of CTEVs and to demonstrate the effectiveness of the Ponseti method through a retrospective follow-up study of 72 patients.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

The study was conducted in accordance with the STROBE Statement (Strengthening Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology: Guidelines for Reporting Observational Studies). This prospective cross-sectional study also adhered to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the institutional review board of A.O.U. Policlinico Rodolico – San Marco of Catania, n. 117/2020/PO. There were 115 patients who were born between February 2011 and July 2023 and treated at the Orthopedic Clinic of the University of Catania for congenital clubfoot. Patients were excluded from the study if their condition did not fall under the definition of idiopathic congenital clubfoot. Such patients included those with pathology that resolved spontaneously or through plantigrade passive correction, syndromic associations, paralytic cerebrovascular diseases, cerebral palsy, and varieties of congenital clubfoot other than CAVE. The final study population comprised 91 patients born with idiopathic congenital clubfoot, who were prospectively followed until November 2023.

Each patient was examined retrospectively using data from the database pertaining to medical certificates issued at each orthopedic specialist visit, applications of plaster casts, percutaneous tenotomy operations, and other types of interventions carried out for relapses during follow-up. Accurate medical history was collected by telephone and a questionnaire that was created on Google Forms. The patient’s name, sex, date of birth, telephone number, affected side, and degree of deformity before the start of treatment were collected. The date of the first visit, the number of plaster casts made before any tenotomy, the date of percutaneous tenotomy were recorded as well. We also noted the adherence or otherwise to the use of the Denis Browne brace after surgery and the duration of its application, the results of the treatment, the possible degree of recurrence, the time of recurrence, the therapy implemented to treat the recurrence, the second result, and the average duration of follow-up. The Pirani score was calculated to quantify the severity of congenital clubfoot before the application of the Ponseti technique.

2.2. Clinical Assessment

The Ponseti functional scoring system was used to evaluate the success of the tenotomy and clinically monitor the patients during follow-up. The system uses an index that is based on the incidence of recurrences of the deformity, amplitude of passive movement (measured with a goniometer), aesthetic appearance, muscular strength, calf atrophy, and foot dimensions, walking quality, functional limitations, footwear use, presence and intensity of pain, and degree of patient satisfaction. The rating scale is based on a maximum score of 100 points, which represents a normal foot.

The scores are classified as excellent (90–100 points), good (80–89 points), fair (70–79 points), and poor (less than 70 points) [

6]. For those with fair and poor scores, additional treatment was deemed necessary to correct the residual deformities. Patients were monitored weekly during the initial stages of treatment until tenotomy was performed. They were then monitored monthly after applying a brace for the first 3 months and then quarterly thereafter. Existing comorbidities were also noted, along with the complications encountered during the application, containment and removal of the limb from the plaster cast and during the use of the Denis Browne brace, the age at which walking began, and sports activities (practice and type) for patients who have reached the relevant developmental stages. Radiographic follow-up was not used in this study.

We also established additional inclusion criteria for the analysis of the results and the search for statistical correlations. These criteria comprised a minimum follow-up of 12 months starting from the date of application of the Denis Browne brace after or without the execution of the Achillea tenotomy. For this purpose, we further divided the population into three subgroups based on the difference in time elapsed between the date of birth and the start date of the plaster cast cycles (less than 1 month of life, between 1 month and 1 year of life, and after 1 year of life).

2.3. Statistic Analysis

Matlab software was used to process data. Matlab is a high-performance software language that integrates mathematical computation, graphical visualization, and programming functions.

3. Results

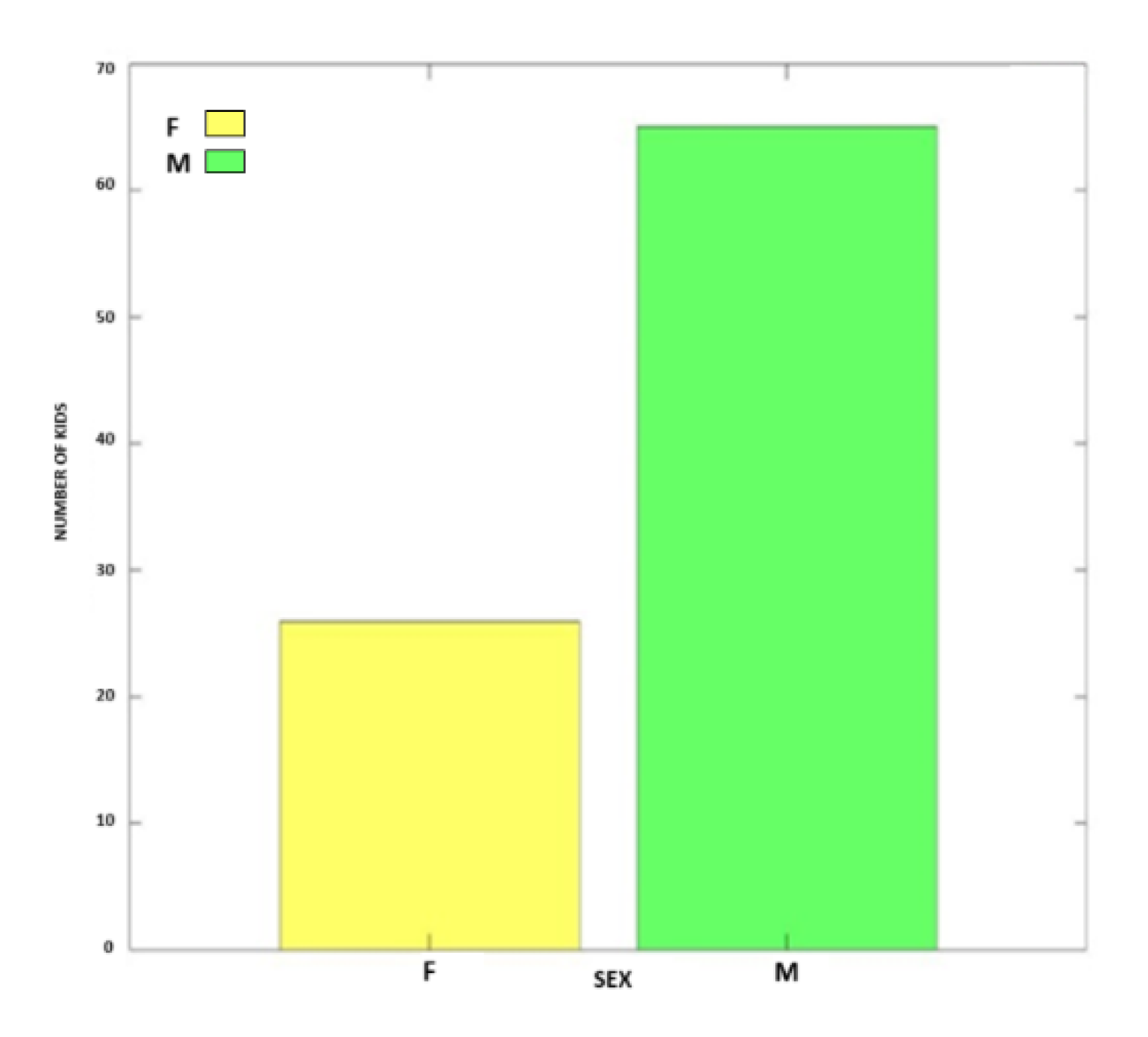

115 patients born between February 2011 and July 2023 were treated at the University Orthopedic Clinic for congenital clubfoot. Of these, 24 patients were excluded due to congenital metatarso-varus clubfoot (1 patient), talo-valgus clubfoot (7 patients), valgus-convex clubfoot (4 patients), syndromic clubfoot (7 patients), and postural clubfoot (5 patients). The final study group included 91 patients (146 clubfeet), of which 65 (71.42%) were male and 26 (28.56%) were female, with a male:female ratio of 2.5:1 (

Figure 1).

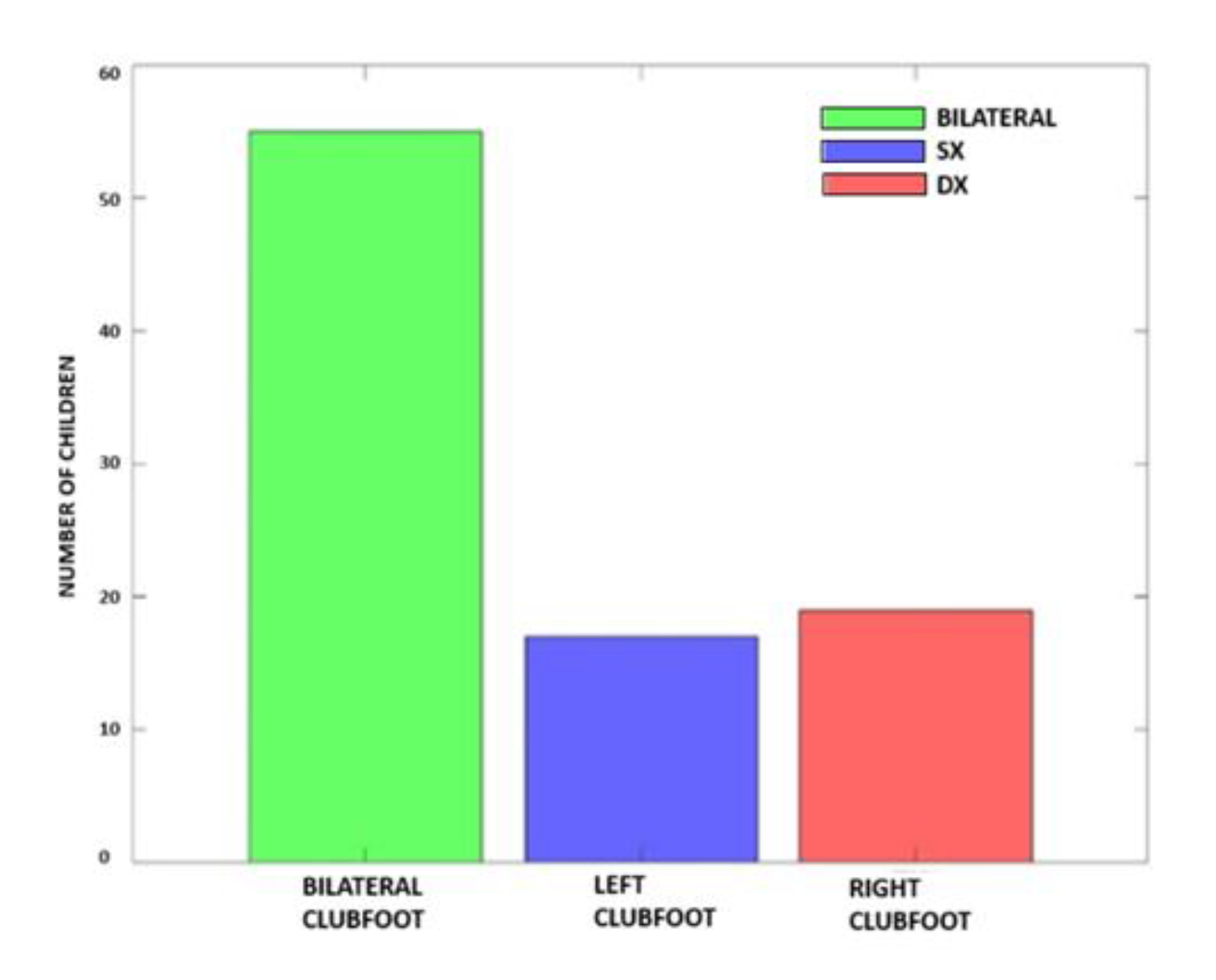

There were 55 patients (60.43%) who had bilateral breech involvement and 36 patients (39.57%) who had unilateral breech involvement, of which 19 (28.58%) had right unilateral involvement, and 17 (10.99%) had left unilateral involvement. The bilateral/unilateral ratio was 1.53, and the right:left ratio was 1.12:1 (

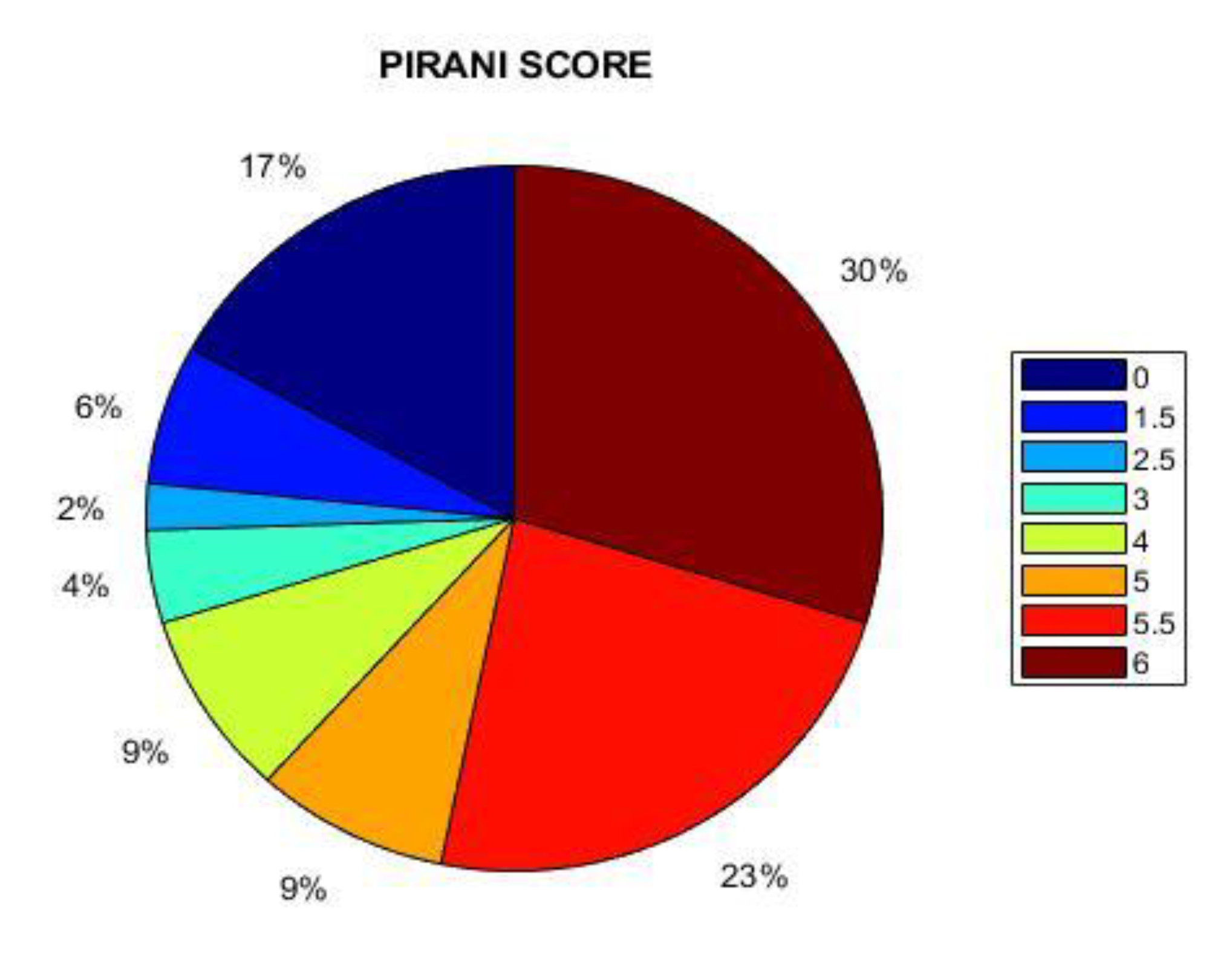

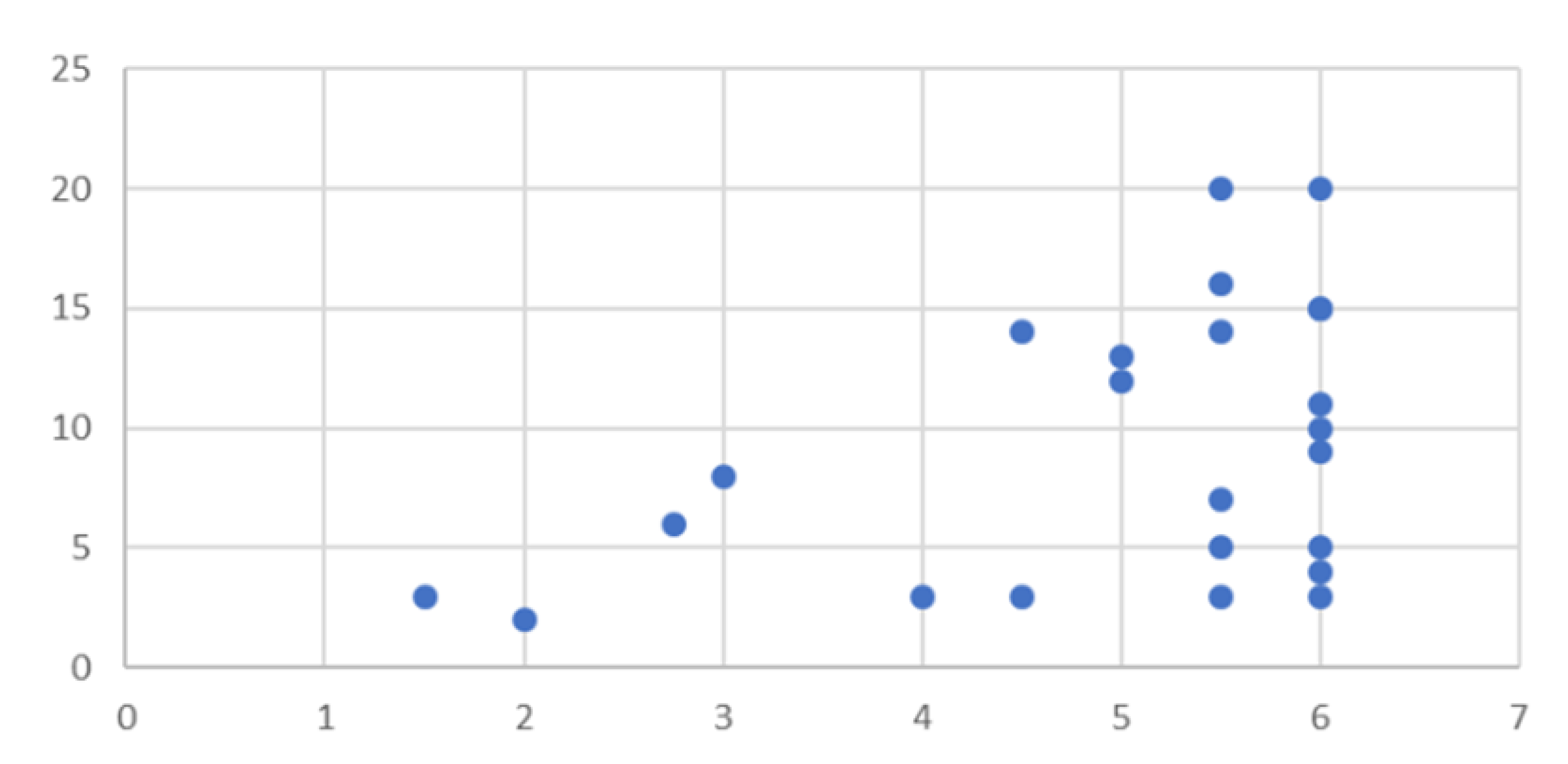

Figure 2). 3 of the 91 children (3.3%) had a contralateral talo-valgus clubfoot as a comorbidity, 2 children (2.2%) had clinodactyly, 1 child (1.1%) had hallux valgus, and 2 children had bilateral congenital hip dysplasia. Only 1 patient had a family history of clubfoot. The Pirani score was calculated for 30 of the 91 patients (48 clubfeet), and 20 clubfeet had a score of 6, 12 clubfeet had a score of 5.5, 5 clubfeet had a score of 5, 1 clubfoot had a score of 4.5, 3 clubfeet had a score of 4, 2 clubfeet had a score of 3, 2 clubfeet had a score of 2.5, and 3 clubfeet had a score of 1.5. The average Pirani score was 5.06 (range 1.5–6) (

Figure 3).

An average of 9.51 casts (range 3–20) were applied to 47 patients. Percutaneous Achilles tendon tenotomy was performed on 83 children (91.21%), of which 50 had bilateral involvement and 33 had unilateral involvement (18 right feet and 15 left feet) with a total of 133 clubfeet (91.1%). In 8 patients (8.79%), however, it was not considered necessary to carry out surgery to correct the deformity. Following the removal of the cast after tenotomy (3 weeks), these 83 patients wore a Denis Browne brace for 24 hours a day during the first 3 months and then for 18 hours a day until the age of 4 years. After that, they transitioned to wearing it progressively less and used it only at night.

An initial correction of the deformity with the Ponseti method was achieved for all 91 patients (146 clubfeet, 100%). This was demonstrated by the Ponseti functional score at 3 weeks after the tenotomy was performed or at the time of application of the Denis Browne brace, which was 90–100 (excellent) for all patients. During the serial cast application and use of the brace, few patients reported complications. 6 children (6.59%) had a desquamative erythema in skin areas subjected to greater pressure. Only 1 child (1.10%) reported a grade-I wound, and 1 patient developed hypotrophy of the quadriceps femoris muscle due to disuse of the lower limb.

In all cases, healing was achieved with simple local medications and by delaying the application of the subsequent plaster cast for an average time of 7 days. In 5 patients (5.49%), wear and incontinency of the casts were recorded several times in subsequent checks. No children (0%) had phlebostatic syndrome, cast ulcers, Denis Browne splint ulcers, or complications after tenotomy, such as profuse bleeding or infection of the percutaneous surgical wound.

Statistical analyses were conducted on the 72 patients who had a minimum follow-up of 12 months. The mean follow-up was 54.15 months (range 12–127 months). Out of the 72 patients, 46 (63.88%) started treatment before the age of 1 month, 19 patients (26.38%) were between 1 month and 1 year old, and 7 (9.72%) were 1 year old. Patients were monitored weekly in the early stages of treatment, monthly after application of the Denis Browne brace for the first three months, and quarterly thereafter.

Of the 72 patients, 16 had a recurrence during follow-up (22.2%) and a fair or poor Ponseti score. Of the 46 patients who started treatment before the age of 1 month, 11 relapsed, while 4 other relapses occurred among the 19 patients who had started treatment between the ages of 1 month and 1 year. Only 1 relapse occurred among the 7 patients who started treatment after 1 year of age.

All of these patients needed a new treatment for the recurrence. In 9 out of 16 patients, it was deemed appropriate to only perform a new cycle of plaster casts since the deformity could be corrected without additional surgery. For 5 patients, a Hoke tenotomy was performed with plantar fasciotomy. In 1 patient, a tibialis anterior tendon transfer was performed along with plantar fasciotomy.

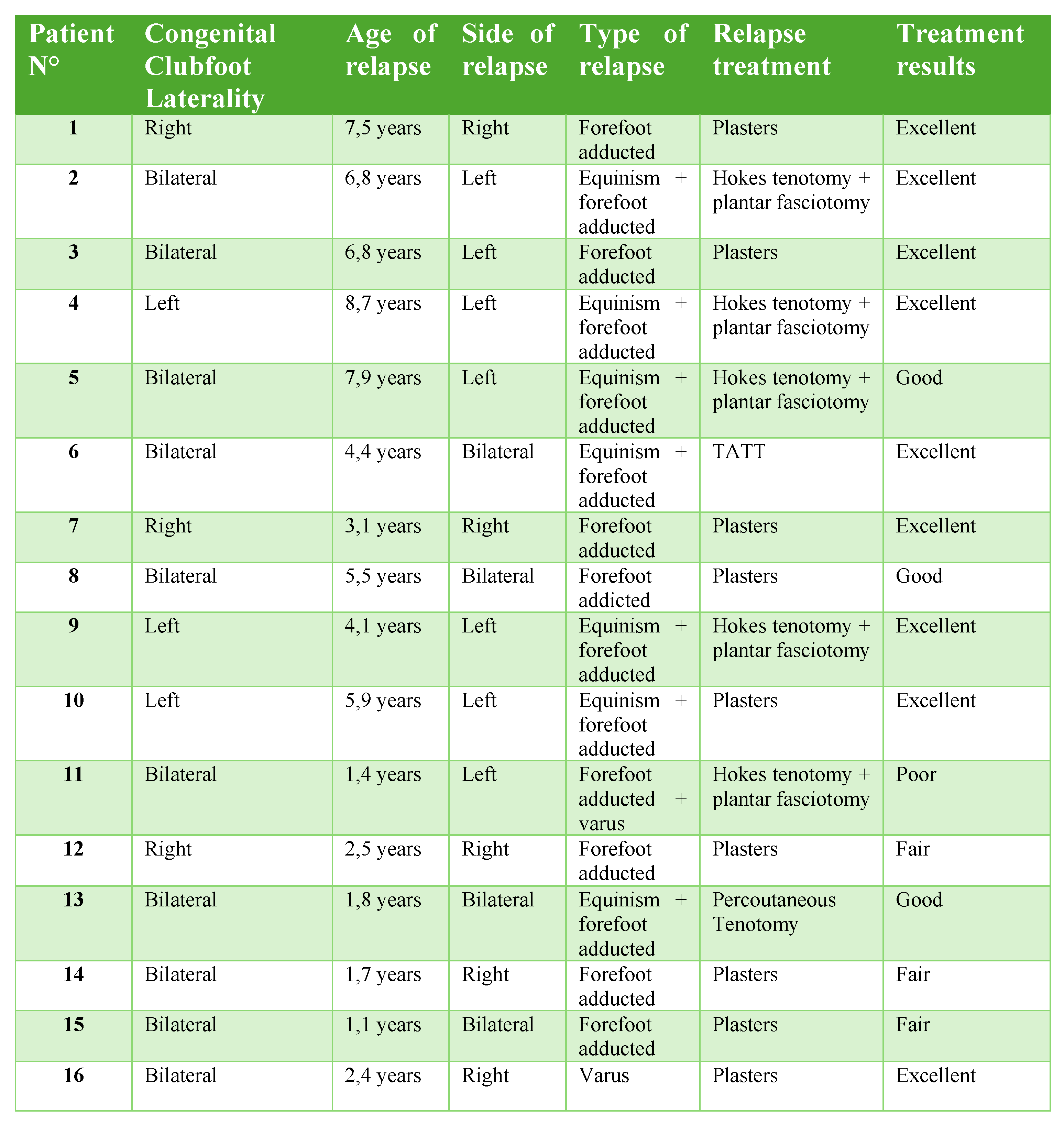

Table 1 indicates the age of the patients at the time of the relapse, bilaterality or unilaterality of the relapsed foot, type of relapsed foot deformity, treatment offered, and treatment results according to the Ponseti score.

Among patients with relapse, the Ponseti score was excellent for 56 patients (77.7%), good for 10 patients (13.88%), fair for 5 patients (6.94%), and poor for 1 patient (1.38%). According to the questionnaire results, correct walking began for 13 children between 12 and 14 months of age, 9 children between 16 and 18 months, and 2 children at 1 year of age or later. 3 children had not yet reached a growth stage that would allow them to walk. 2 children played football, 2 swam, 1 played volleyball, 1 practiced judo, and 18 did not practice any sport by choice.

4. Discussion

Among all possible treatments for congenital clubfoot, the Ponseti method is considered the mainstay of treatment in our medical unit. A systematic review by Carrero et al. demonstrated that the Ponseti method is the gold standard treatment of congenital clubfoot and that it is effective and safe. In recent years, the method has gained acceptance as a conservative method of deformity around the world. The success rate of this technique is usually around 90%. Although recurrences are possible, the rate is much lower than those of more invasive procedures [

6].

The Kite and Ponseti techniques show good results, but the Ponseti method seems to lead to better results than the Kite method in clubfoot correction. With the Ponseti method, fewer casts are needed, and the treatment is shorter. The maximum dorsiflexion achieved in the ankle is significantly greater, and residual deformity and recurrence have slightly lower rates [

8,

9,

10].

Gintautenie et al. compared the Ponseti technique with an early transfer of the tibialis anterior tendon. The latter technique allowed a reduction in the duration of the orthosis; however, a possible weakening of dorsiflexion was observed. The results obtained are the same as those seen with the Ponseti method; therefore, it is a good option to opt for conservative treatment [

11]. Zwick et al. compared surgical treatment with the Ponseti method. Patients treated with the Ponseti method achieved better results with plantigrade feet and no pain. Furthermore, higher parental satisfaction and better foot mobility were achieved compared to the other foot treatment [

12].

One of the advantages of the Ponseti method is the degree of mobility that it guarantees at the end of the treatment. However, one disadvantage is that the degree of success may depend on variables such as age, sex, early diagnosis, associated deformities, and the number of casts used. Sanghvi and Mitta and Lara et al. recommend starting the technique in the first 15 days of life. This means that clubfoot should be treated as soon as possible so that good results are easier to obtain [

9,

13].

According to other authors, however, the age at which treatment begins makes no significant difference, and clubfoot can be corrected even later. A retrospective study examined children with CAVE treated at University Malaya Medical Center from 2013 to 2017. 54 children (35 males and 19 females) were divided into two cohorts: group 1 received treatment before the age of 1 month, and group 2 received treatment after 1 month. All affected feet (100%) achieved complete correction, one foot in group 1 had a recurrence, and three feet in group 2 had a recurrence, but the difference was not statistically significant. All relapsed feet were successfully treated with the repeated Ponseti method [

14].

Bilateral deformity does not appear to be a parameter that worsens functional outcomes after treatment. Sapienza et al. showed that patients with bilateral CTEV treated with tenotomy achieve static and dynamic values comparable to healthy controls. Tenotomy promotes long-term dynamic development similar to that in the healthy population and results in better postural outcomes than non-surgical cases. Additionally, bilateral patients outperform unilateral cases in dynamic values [

15].

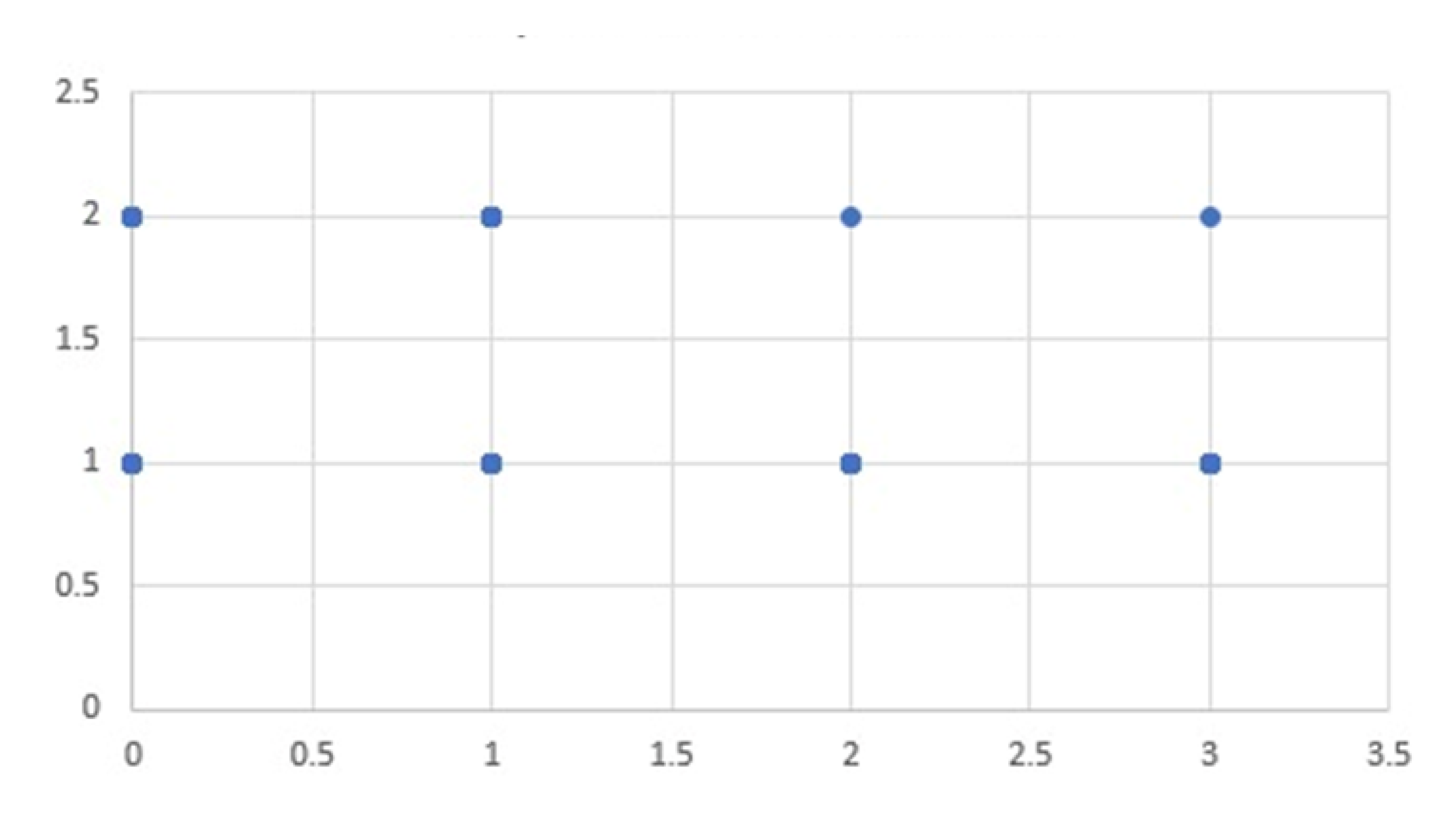

We looked for statistical correlations between the start date of treatment and the occurrence or otherwise of relapses by dividing patients into 3 groups based on the age when they had started treatment: group A: before 1 month; group B: between 1 month and 1 year; and group C: after 1 year of age. The statistical correlation was not significant between the two variables (

p=0.06) (

Figure 4), which is consistent with a previous study [

14]. Therefore, it does not appear that the start of treatment in the analyzed time frame impacts the occurrence of relapses.

Another aspect that we focused on is whether higher Pirani scores corresponded to a greater number of casts. The literature shows that at least 6 casts are needed on average, but this depends on the severity of the foot deformity. In the study by Agarwal et al. with 297 children (442 feet), the average initial Pirani score was 4.8, and the number of corrective casts was 7 per child (range 2 to 18). Their regression analysis showed that both the Pirani score and age had a positive correlation with the number of casts, although it was weak (

r2 = 0.05–0.20). Compared to age, the correlation of the initial Pirani score with the number of casts was 10 times stronger, which suggests a probable correlation between them [

16].

Pavone et al. demonstrated that there was no significant correlation between the number of casts (mean number of casts: 7.1 ± 1.8) and the months required to reach the independent gait stage [

17]. In our analysis, we compared the Pirani Score of 48 clubfeet with the number of casts made for each of them. The result showed a moderate statistical correlation (

p = 0.42) between the two variables, as shown in

Figure 5. The average Pirani score was 5.06, indicating a moderate level of severity in the deformities, while the average number of casts was 9.51. These results show that there is a probable connection between more severe deformities indicated by a higher Pirani Score and a greater number of casts. However, the correlation is moderate, meaning that other factors may also influence the treatment process.

Finally, we evaluated whether the correct use of the brace can prevent relapses. It is well established in the literature that the occurrence of post-tenotomy relapses and their number, severity, and date are correlated to a lack of use or incorrect and inconsistent use of the Denis Browne brace. The brace protocol involves full-time application (24 hours a day) for at least 3 to 4 months, followed by application during rest and at night for the following 2 to 5 years (from 2 to 4 hours in the middle of the day and for 12 hours at night for a total of 14 to 16 hours a day), up to 3 or 4 years of age.

Pavone et al. previously conducted a study at the same orthopedic clinic of the University of Catania with 82 patients (114 clubfeet). The average follow-up was 4 years (range 13–83 months). A relapse rate of approximately 3% was reported (one foot had a recurrence with an adducted and varus recurrence pattern, another foot had equinus, and one foot had a total recurrence with all four components of clubfoot) (

Figure 6). These recurrences were all due to noncompliance with the Denis Browne splint and infrequent use of the splint due to a lack of education and the socioeconomic status of the parents of the children with clubfoot [

15].

In the present study, which was performed about 10 years later, we also looked for a statistical correlation between the time of using the Denis Browne brace and recurrence. We divided the 72 patients into four groups based on no use of the brace (16 patients), use for less than 1 year (19 patients), use for 1 to 4 years (21 patients), and use for more than 4 years (16 patients). There were 6 relapses in the first group, 8 relapses in the second, 1 relapse in the third, and 1 relapse in the fourth group. There was a statistically significant correlation (p=0.47) between recurrences and a shorter duration of brace use, which is in line with the literature. The questionnaires also showed that incorrect adherence to the brace protocol was related to poor socioeconomic status of the parents of patients and a lack of strictness when applying the treatment, which may have been the main cause of relapses.

5. Conclusions

Children treated with the Ponseti method developed feet that appear normal and function like those of a healthy individual. These results will allow them to participate in sports as they choose and in various recreational activities once they reach adulthood. However, it is essential to maintain an intensive rehabilitation program and conduct regular monitoring into adulthood as the risk of relapse is particularly high during the first 3 years after treatment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.T. and M.S.; methodology, M.S.; software, G.D.; validation, V.P., F.C. and M.S.; formal analysis, G.M.Z.; investigation, MI.S.; resources, MI.S.; data curation, G.D.; writing—original draft preparation, G.D.; writing—review and editing, G.T.; visualization, M.S.; supervision, V.P.; project administration, V.P.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Institutional Review Board Statement The study was conducted according to the Statement on Strengthening Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology: Guidelines for Reporting Observational Studies. This prospective cross-sectional study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the institutional review board of A.O.U. Policlinico Rodolico – San Marco of Catania, n. 117/2020/PO.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- Herring, J. A. (2022). Tachdjian’s Pediatric Orthopaedics: from the Texas Scottish Rite Hospital for Children (Sixth Edition, Vol. 2). Elsevier, Inc.

- Hernigou, P., Huys, M., Pariat, J., & Jammal, S. (2017). History of clubfoot treatment, part I: From manipulation in antiquity to splint and plaster in Renaissance before tenotomy. International Orthopaedics, 41(8), 1693–1704. [CrossRef]

- Smythe T, Kuper H, Macleod D, Foster A, Lavy C. Birth prevalence of congenital talipes equinovarus in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Trop Med Int Health 2017; 22(3): 269-85. [CrossRef]

- Cardy AH, Sharp L, Torrance N, Hennekam RC, Miedzybrodzka Z. Is there evidence for aetiologically distinct subgroups of idiopathic congenital talipes equinovarus? A case-only study and pedigree analysis. PLoS One. 2011 Apr 20;6(4):e17895. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pavone V, Vescio A, Caldaci A, Culmone A, Sapienza M, Rabito M, Canavese F, Testa G. Sport Ability during Walking Age in Clubfoot-Affected Children after Ponseti Method: A Case-Series Study. Children (Basel). 2021 Mar 1;8(3):181. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Porecha, M. M., Parmar, D. S., & Chavda, H. R. (2011). Mid-term results of ponseti method for the treatment of congenital idiopathic clubfoot - (A study of 67 clubfeet with mean five year follow-up). Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research, 6(1). [CrossRef]

- López-Carrero, E., Castillo-López, J. M., Medina-Alcantara, M., Domínguez-Maldonado, G., Garcia-Paya, I., & Jiménez-Cebrián, A. M. (2023). Effectiveness of the Ponseti Method in the Treatment of Clubfoot: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4). [CrossRef]

- Garcia, L. C., de Jesus, L. R., Trindade, M. de O., Filho, F. C. G., Pinheiro, M. L., & de Sá, R. J. P. (2018). EVALUATION OF KITE AND PONSETI METHODS IN THE TREATMENT OF IDIOPATHIC CONGENITAL CLUBFOOT. Acta Ortopedica Brasileira, 26(6), 366–369. [CrossRef]

- Sanghvi, A. V., & Mittal, V. K. (2009). Conservative management of idiopathic clubfoot: Kite versus Ponseti method. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery (Hong Kong), 17(1), 67–71. [CrossRef]

- Sud, A., Tiwari, A., Sharma, D., & Kapoor, S. (2008). Ponseti’s vs. Kite’s method in the treatment of clubfoot--a prospective randomised study. International Orthopaedics, 32(3), 409–413. [CrossRef]

- Gintautienė, J., Čekanauskas, E., Barauskas, V., & Žalinkevičius, R. (2016). Comparison of the Ponseti method versus early tibialis anterior tendon transfer for idiopathic clubfoot: A prospective randomized study. Medicina (Kaunas, Lithuania), 52(3), 163–170. [CrossRef]

- Zwick, E. B., Kraus, T., Maizen, C., Steinwender, G., & Linhart, W. E. (2009). Comparison of Ponseti versus surgical treatment for idiopathic clubfoot: a short-term preliminary report. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 467(10), 2668–2676. [CrossRef]

- Lara, L. C. R., Neto, D. J. C. M., Prado, F. R., & Barreto, A. P. (2013). Treatment of idiopathic congenital clubfoot using the Ponseti method: ten years of experience. Revista Brasileira de Ortopedia, 48(4), 362–367. [CrossRef]

- Lee, B & Mazelan, A & Gunalan, Reetha & Albaker, Mohammed Ziyad & Saw, Aik. (2020). Ponseti method of treating clubfoot - Is there difference if treatment is started before or after one month of age?. The Medical journal of Malaysia. 75. 510-513.

- Sapienza M, Testa G, Vescio A, Scuderi B, de Cristo C, Lucenti L, Vaccalluzzo MS, Caldaci A, Canavese F, Pavone V. Comparison between unilateral and bilateral clubfoot treated with Ponseti method at walking age: static and dynamic assessment. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2024 Oct 1. Epub ahead of print. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, A., & Gupta, N. (2014). Does initial Pirani score and age influence number of Ponseti casts in children? International Orthopaedics, 38(3), 569–572. [CrossRef]

- Pavone V, Sapienza M, Vescio A, Caldaci A, McCracken KL, Canavese F, Testa G. Early developmental milestones in patients with idiopathic clubfoot treated by Ponseti method. Front Pediatr. 2022 Aug 24;10:869401. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).