1. Introduction

Fractures are decidedly common injuries in the pediatric population, accounting for approximately 25% of all childhood injuries, with radial and ulnar fractures having the highest incidence, making up 36% of all childhood fractures [

1]. The mechanism of injury is mainly accidental trauma resulting from sports or leisure activities [

2].

Diaphyseal forearm fractures in children are classified via the Pediatric Comprehensive Classification of Long-Bone Fractures (PCCF) created by the Swiss Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen (AO) Foundation [

3]. Treatment methods are determined by the stability and complexity of the fracture morphology. Stable, nondisplaced diaphyseal fractures can be treated conservatively with immobilization utilizing a long arm cast [

4,

5]. Noonan and Price described the conservative treatment limits of pediatric forearm shaft fractures by considering patient age, fracture angulation, rotation around the longitudinal axis of the affected bone, and bayonet apposition [

6]. Intrinsically unstable fractures require operative treatment. Oblique, spiral, multifragmentary, completely displaced, converging fractures, and both-bone forearm fractures at the same level are some examples of unstable fracture morphology.

Elastic stable intramedullary (IM) nailing (ESIN) is considered the gold standard operative treatment method for unstable diaphyseal forearm fractures [

7,

8]. This minimally invasive procedure avoids a large incision at the fracture site, thereby significantly reducing the risk of infections, bleeding, and hypertrophic scarring, in contrast to an open approach using plate and screw fixation. ESIN also leads to minor soft tissue damage upon subsequent implant removal. In recent years, however, several articles have discussed primary surgical complications [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. It may result in transient nerve palsy, malunion, or postoperative compartment syndrome [

10]. Synostosis, muscle entrapment, osteomyelitis, hardware migration or malplacement, loss of reduction, and significant range of motion reduction have also been described [

11,

12]. Depending on the entry point, during a dorsal approach, rupture of the extensor pollicis longus (EPL) tendon occurred relatively frequently [

13,

17]. Meanwhile, the metal end may cause skin irritation and skin perforation, regardless of the entry point [

12,

17]. Post-operative radial bow was significantly higher in the ESIN group, without affecting forearm movement [

18]. Several authors have also reported complications related to metal removal, such as injury to the sensory branch of the radial nerve [

14,

15]. Younger children seem to have a higher refracture rate [

19].The general complication rate ranges from 10 to 67%, with varied results reported in different studies. Complications may occur after ESIN implantation, during the procedure, or after nail removal [

5,

11,

12].

Internal fixation with plates and screws can be performed in unstable pediatric diaphyseal forearm fractures, as an alternative for titanium IM nails, preferably in skeletally mature or near-mature children [

20]. Delayed unions and nonunions are rare but seem to be slightly more common with ESIN compared to internal fixation, although with a statistically insignificant difference [

21].

Fractures with accompanying extensive soft tissue damage, compartment syndrome, open fractures, and complicated multi-fragmentary fracture morphologies may be treated with fixateur externe [

20]. This can be a definitive treatment method or part of a multi-step treatment plan for example in a polytrauma patient being treated according to damage control protocol.

In recent years bioabsorbable IM nails (BINs) have been developed and used in the treatment of pediatric diaphyseal forearm fractures. Their aim is to eliminate the need for a second surgery for metal removal and reduce the total required anesthesia, exposure to radiation through imaging, length of hospital stay (LOS), discomfort by the procedures, and therefore the whole financial burden of an additional intervention [

22]. BINs require only one minimally invasive surgical procedure for insertion and thereafter dissolve within the medullary canal at a rate slower than bone healing [

23].

Our first descriptive publications reporting the use of absorbable implants in pediatric forearm fractures provided a thorough presentation of the surgical technique and the advantages and disadvantages of the method [

22,

24]. However, there is very little data in the international literature regarding the technical difficulties and complications related to resorbable IM implants, which differ from traditional titanium elastic nailing in many aspects [

25].

Therefore, the aim of this study is to describe the intraoperative difficulties and potential complications after poly-L-lactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA) BIN management of pediatric diaphyseal fractures.

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patient Selection

The Department of Pediatrics at the University of Pécs, Clinical Complex and the Department of Pediatric Traumatology, Péterfy Hospital, Manninger Jenő National Trauma Center are involved in an ongoing prospective multicenter clinical study analyzing the treatment of pediatric diaphyseal forearm fractures with the IM PLGA implants (Activa IM-Nail™, Bioretec Ltd., Tampere, Finland). This study aims to observe and document any intraoperative difficulties and postoperative complications with PLGA BIN treatment between May 2023 and January 2025.

Out of 161 children, seven patients met the inclusion criteria, which were: (1) pediatric patient (≤ 18 years old), (2) suffering a diaphyseal forearm fracture, (3) receiving PLGA IM implants. No patients were excluded from the study, however, the contraindications of PLGA BINs would have restricted its application in the cases of: (1) bilateral- (2) oblique spiral-, (3) multi-fragmentary-, or (4) epiphyseal fractures, (5) local infection, (6) poor compliance, and (7) bone re-modelization affecting comorbidity or (8) medication; however, no patient was admitted with any of these circumstances during the investigation period.

2.2. Intervention

Our IM implant was a PLGA-based internal fixation, that supported stabilisation of the fracture and bone healing. Once placed, the polymer undergoes hydrolytic breakdown, releasing degradations products that feed into the citric acid cycle, where they are converted to water and carbon dioxide (CO

2) [

26]. The local drop in pH created by this process helps pace the gradual disappearance of the BIN. By around 9–12 months, decomposition is typically finished—aligning with the timeframe needed for fracture repair in children and erasing the necessity for a second operation to remove fixation material [

27,

28].

To aid surgeons in confirming proper placement, β-tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP) markers are included in the implant, making it visible under fluoroscopy. Varying the ratio of lactic to glycolic acid in the PLGA allows control over how quickly the nail erodes and how it performs structurally. These adjustments support fracture alignment while offering a biodegradable solution that meets the demands of a growing skeletal system.

2.3. Operative Algorithm

Minimally invasive implantation of PLGA nails follows several essential steps. After standard skin cleansing, disinfecting, and induction of general anesthesia, the child is positioned supine with the affected forearm on a radiolucent support. Perioperative comfort is ensured by a tailored analgesic protocol involving 0.1–0.2 mg/kg nalbuphine (Nubain, ALTAMEDICS GmbH, Cologne, Germany) and, if warranted, sedation with midazolam (Dormicum, Egis Gyógyszergyár Zrt, Budapest, Hungary), following parental agreement.

Small radial incisions over the distal radius and lateral incisions over the proximal ulna provide entry to the cortical bone using an awl or drill. For the radial bone, the drill is guided perpendicular to the cortex initially, then reoriented to a more acute angle in line with the diaphysis. Sequentially, the medullary canals are expanded with dilators matching the implants’ diameters (2.7 or 3.2 mm) and lengths (200, 300, or 400 mm). Selecting an appropriately sized implant is vital; it should fit comfortably within the narrowest portion of the intramedullary space.

Once canals are prepared, the PLGA nails are introduced with an inserter, avoiding rotational stresses that might impair fracture alignment. Fluoroscopic checks confirm correct positioning, aided by the β-TCP tips. Any excess nail protruding beyond the cortex is trimmed, ensuring smooth bone-implant junctions that minimize soft-tissue discomfort. Each small incision is then joined with absorbable material, using intracutaneous suture lines in the skin.

Post-surgical care usually involves placing the arm in an above-elbow cast with the elbow flexed at 90 degrees for approximately 4–6 weeks, allowing primary bone stability to consolidate. Strenuous activity, including sports, is discouraged for 4–6 months to prevent re-injury. This protocol tries to achieve a balance between necessary immobilization for fracture healing and the eventual return to normal activities.

3. Results

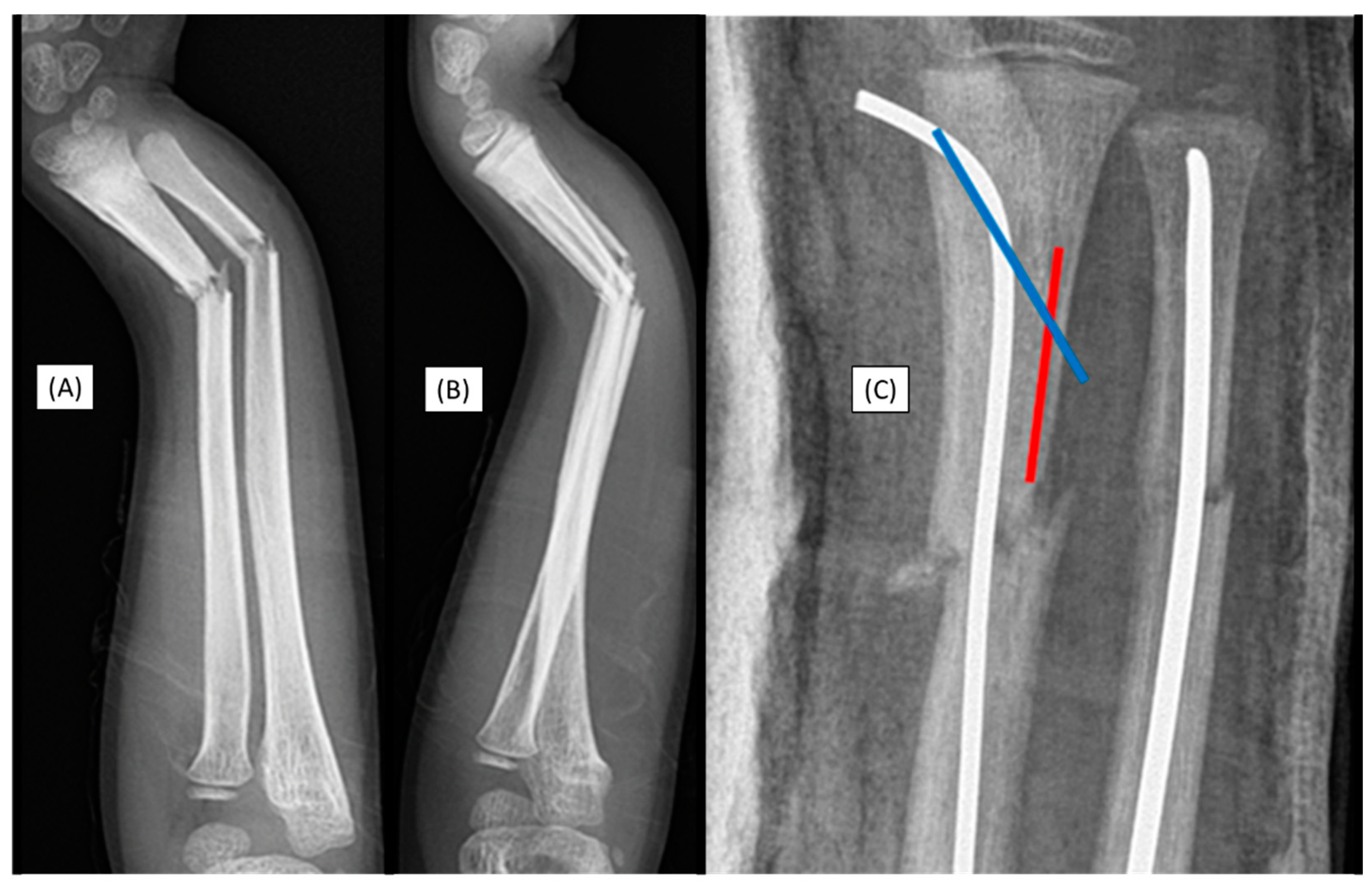

3.1. Case 1: Iatrogenic Cortex Perforation

A 12-year-old boy's left forearm was injured during a handball match. X-rays confirmed a distal dia-metaphyseal forearm fracture. Following the closed reduction of a left distal diaphyseal forearm fracture, due to instability, the (2.7 mm) dilator was introduced through a typical radial approach, which resulted in cortical perforation on the opposite side (

Figure 1(C)). Preparation of the medullary cavity is crucial when using absorbable IM implants. Although this patient case did not involve an implant-related complication, it directly relates to the challenges associated with the surgical procedure. Therefore, when such intraoperative complications are observed, the use of absorbable implants is not recommended.

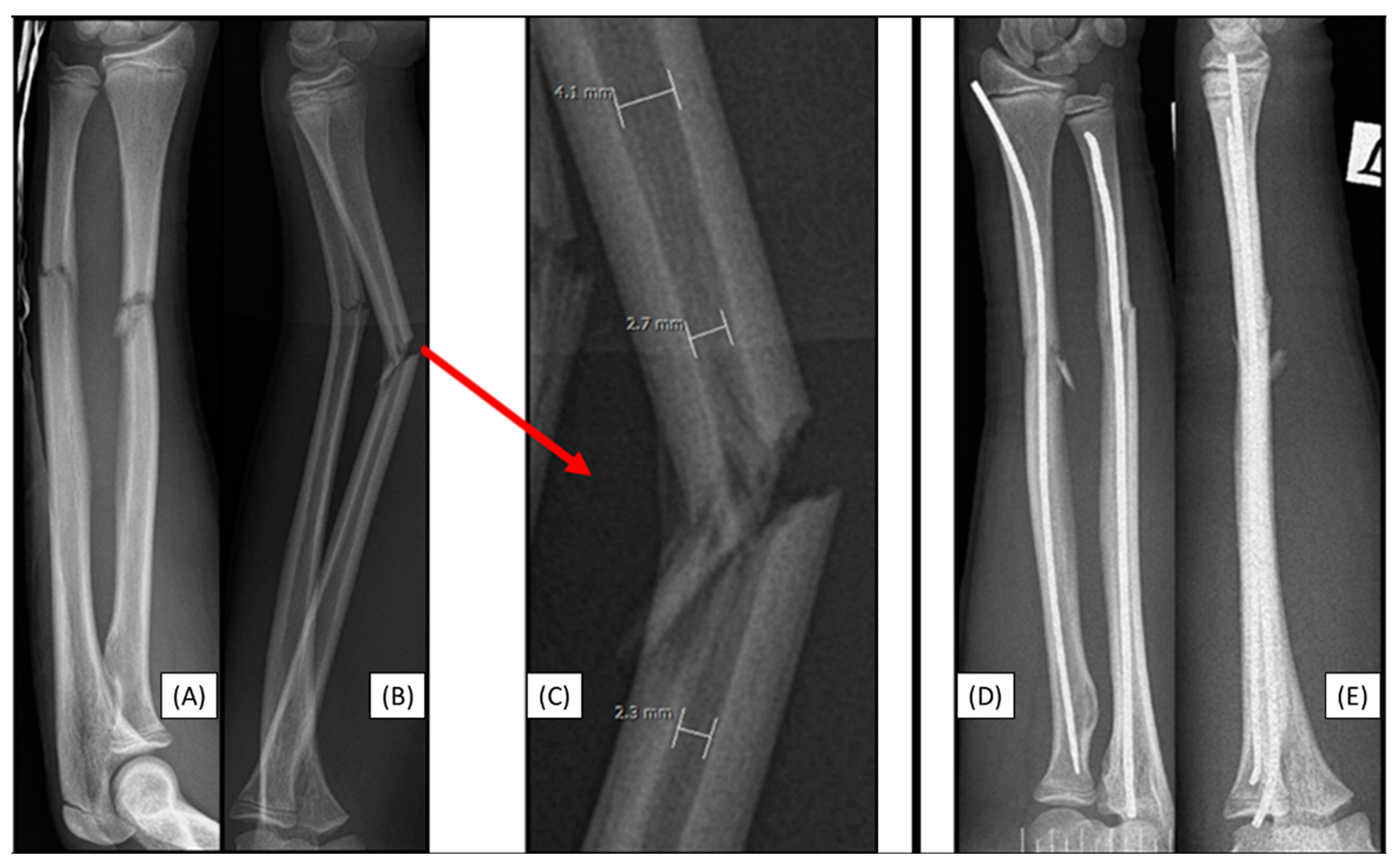

3.2. Case 2: Narrow Medullary Cavity

A 14-year-old boy was scheduled for surgical treatment due to a displaced, unstable middle-third forearm fracture (AO type: 22-D/2.1.). Preoperative measurements indicated that the medullary cavity diameter was narrow(

Figure 2(A-C)). Although this patient case did not involve an implant-related complication, it directly relates to the challenges associated with the surgical procedure. Despite multiple attempts, the introduction of the 2.7 mm dilator failed during the preparation of the radius medullary cavity. The radius was stabilized with a two mm elastic nail, while the ulna was stabilized with a 2.5 mm nail (

Figure 2(D-E)). As with any surgery, preoperative planning is crucial, including measuring the diameter and shape of the medullary cavity. Several publications address the morphology of the pediatric medullary cavity, which can influence the choice of treatment method. In our case, we were unable to prepare the medullary cavity, thus making the use of absorbable IM implants unfeasible.

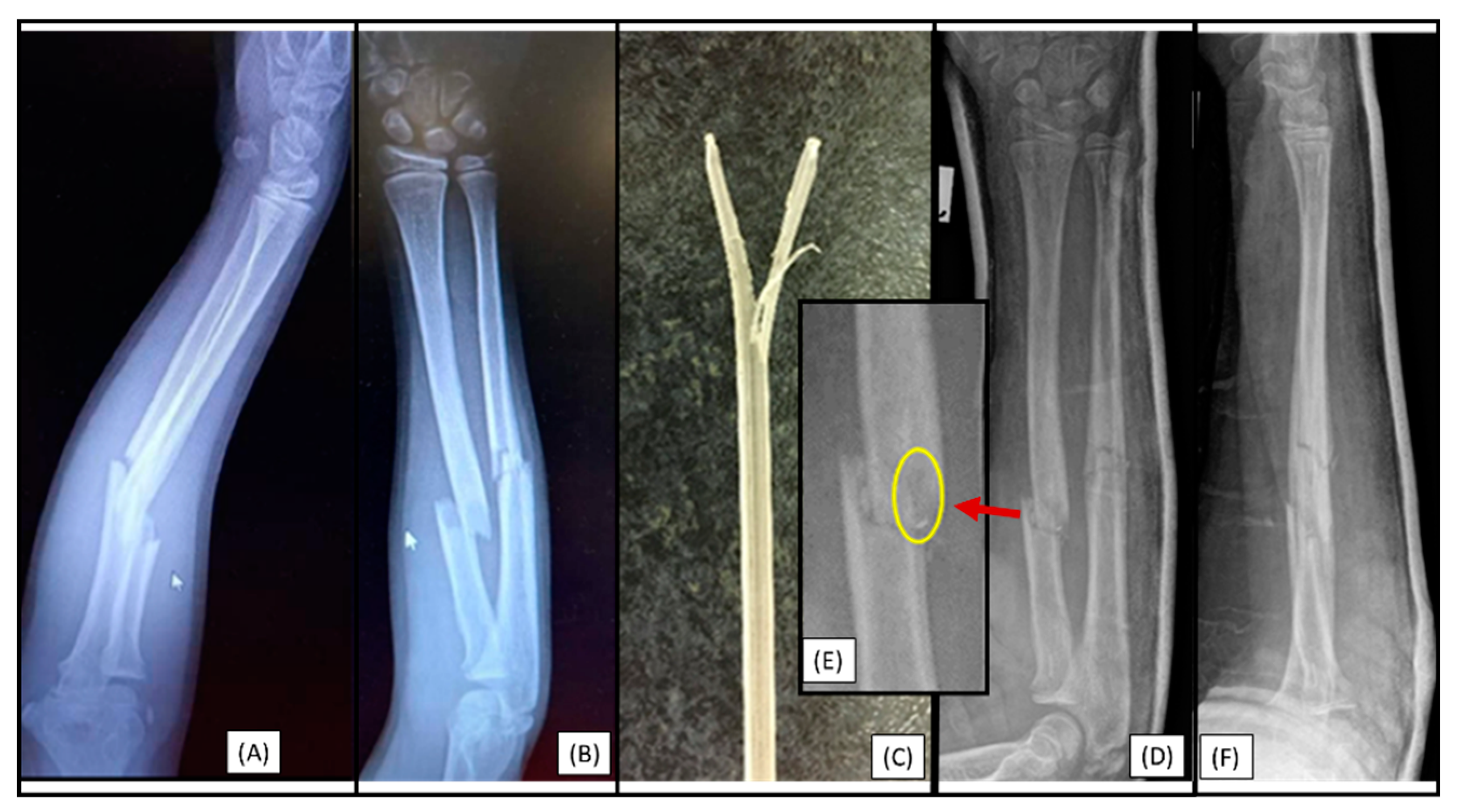

3.3. Case 3: Apical Implant Splitting

A 10-year-old child was injured while playing on a trampoline. He suffered a complete (22-D/4.1.) fracture of the right forearm. Following the closed reduction of a complete proximal third forearm fracture and proper preparation of the medullary cavity, the introduction of the (3.2 mm) absorbable IM PLGA implant at the fracture site was difficult (

Figure 3(A-B)). The BIN could not be passed through the fracture gap, and the β-TCP marking was visible outside the bone's medullary cavity, projecting onto the interosseous membrane. After removal of the implant, we observed that the end of the nail had split (

Figure 3(C)). This can be explained by challenges in surgical technique that led to an implant-related complication (implant failure) and due to the fact that after losing the precise reduction, the introduction of the absorbable implant was forced, causing it to break. Therefore gentle implant insertion in case of obstruction is preferred, like withdrawing and repeating the preparation of the medullary cavity with an appropriately sized dilator.

3.4. Case 4: Focal Medullary Cavity Stenosis

After a closed reduction of a diaphyseal forearm fracture (22-D/2.1.) and proper preparation of the medullary cavity, the resorbable (2.7 mm) IM implant became stuck after passing through the fracture gap in an 8-year-old child. The etiology behind the blockage was the shape of the medullary cavity, which could not be adequately prepared even with the dilator. Subsequently, the implant became stuck, however, we did not attempt to force its removal (

Figure 4.). Although this patient case did not involve an implant-related complication, it directly relates to the challenges associated with the surgical procedure and requires careful patient selection.

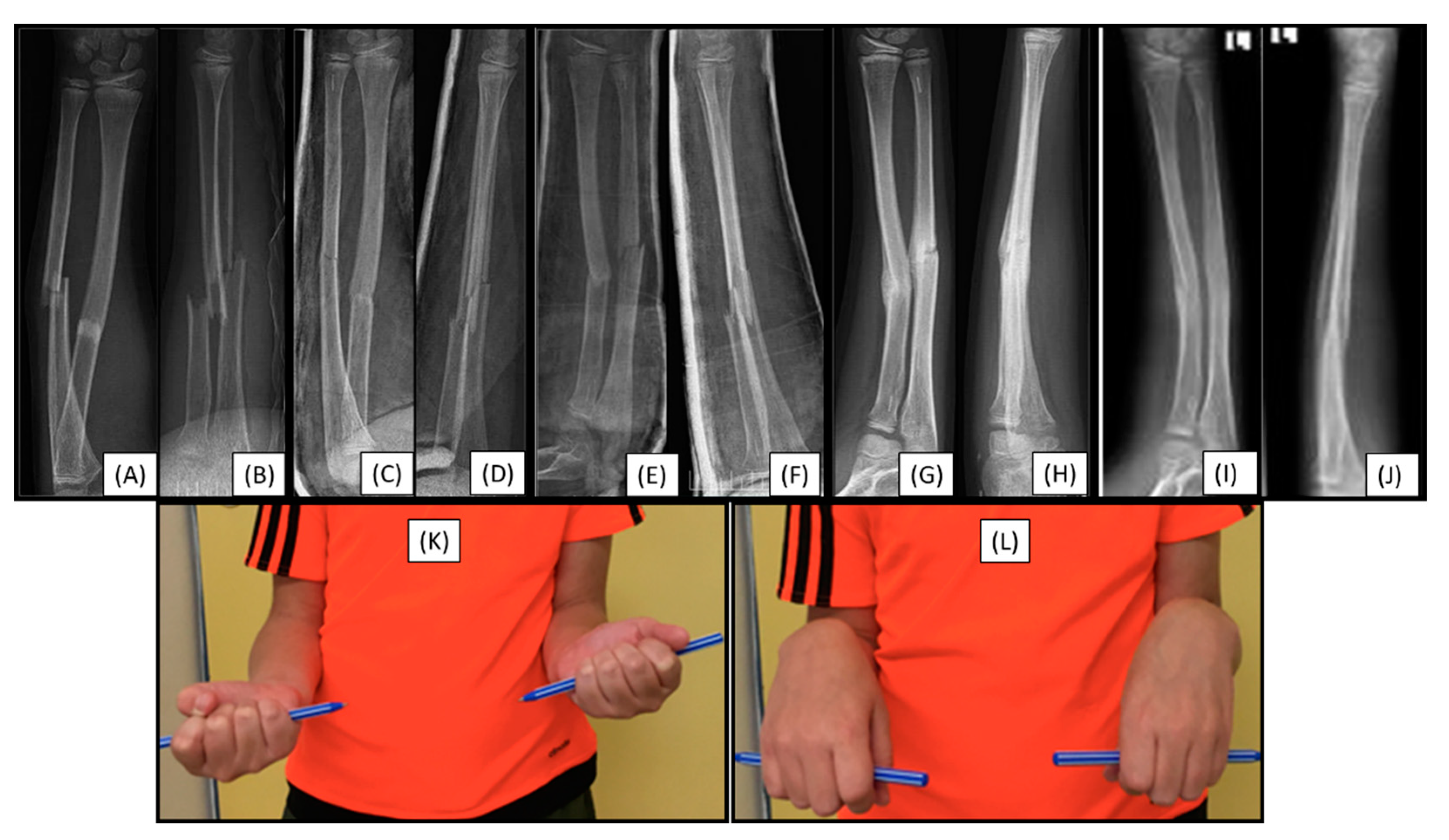

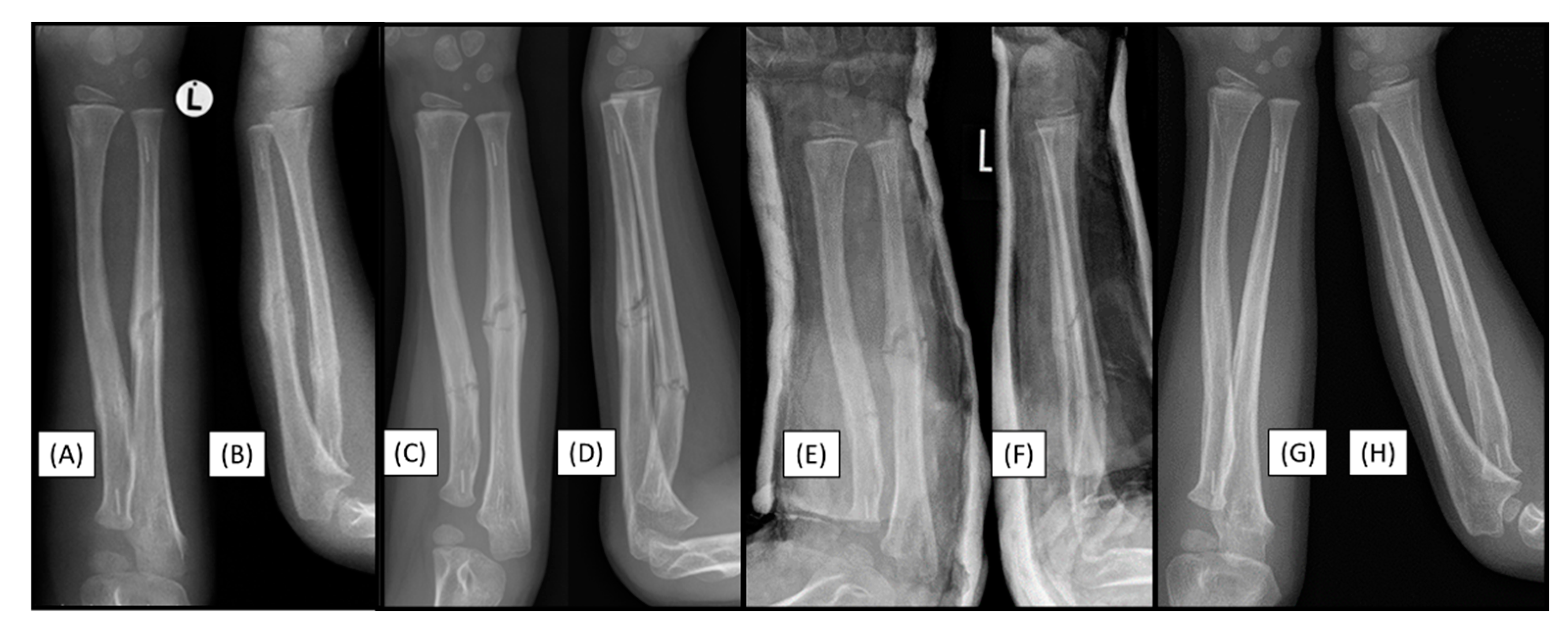

3.5. Case 5: Secondary Malalignment

Secondary malalignment was observed in a 12-year-old patient who had sustained a both-bone proximal diaphyseal forearm fracture (22-D/4.1.) in the left arm (

Figure 5(A-B)). These fractures were reduced and stabilized with PLGA BINs. Postoperative visualization initially showed adequate alignment (

Figure 5(C-D)).

Control X-rays performed one week postoperatively showed a mild secondary malalignment, with shaft axis angulation of <15° (

Figure 5(E-F)). On an imaging follow-up, eight weeks after surgery, the angulation persisted, and a callus had formed at the fracture sites (

Figure 5(G-H)). Clinically, the patient showed a 10° deficit in supination of the left wrist (

Figure 5(K)), with no deficit in pronation (

Figure 5(L)). The child is currently being followed up.

3.6. Case 6: Early Refracture

A 6 year-old-boy left both bone diaphyseal forearm fractures (22-D/2.1.) were initially managed with closed reduction and immobilization in a long-arm plaster cast. However, a control X-ray performed five days after cast application revealed increased angulation of the radius despite conservative treatment, indicating the need for operative intervention. Subsequently, the fractures were treated with closed reduction and resorbable IM nailing. Plaster cast removal was four weeks postoperatively, and the control X-ray showed satisfactory alignment (

Figure 6(A-B)).

Eight weeks after the operation, the patient experienced an accident, falling while jumping on a trampoline. Despite our recommendation to avoid returning to sports for 4-6 months, this case, although not directly implant-related complication, underscores the importance of adhering to post-operative guidelines. Upon visualization, an X-ray of the left arm revealed a refracture with mild angulation (

Figure 6(C-D). A long-arm cast was applied, and a control X-ray taken post-procedure showed appropriate alignment (

Figure 6(E-F). Six-month follow-up radiographic images demonstrated good callus formation and maintained alignment (

Figure 6(G-H), moreover, the clinical examination confirmed a full range of motion (ROM).

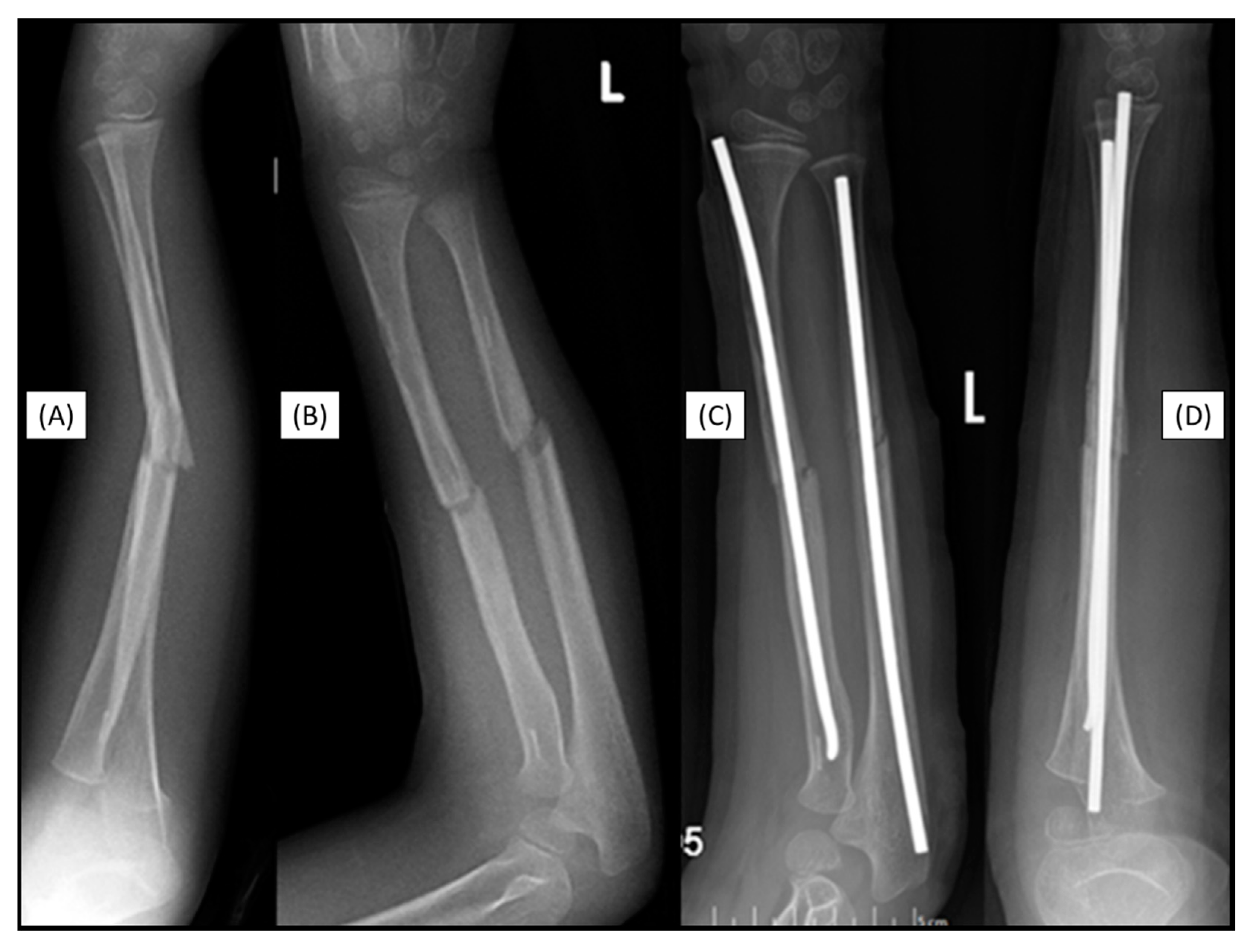

3.7. Case 7: Recurrant Fracture

The forearm fracture (22-D/2.1.) of a 7-year-old boy was fixed with a primary absorbable intramedullary implant. Two years after the closed reduction and fixation of a left forearm diaphysis fracture with a BIN implant, a repeated not implant related forearm diaphysis fracture occurred the injury was caused by a fall from a horse. (

Figure 7(A-B). After closed reduction, the forearm bones were stabilized with titanium ESINs. During the surgery, no resistance was encountered in the IM space, and the medullary cavity was free, allowing for smooth insertion of the titanium implant without any difficulties (

Figure 7(C-D).

4. Discussion

Pediatric diaphyseal forearm fractures are common injuries in children. Their treatment approach depends on the stability and morphology of the fracture. Unstable fractures, such as those involving significant displacement, rotation, or both-bone fractures, typically require surgical intervention [

4]. Currently, ESIN is considered the gold standard for treating unstable pediatric forearm fractures, despite its well-documented drawbacks [

8,

11,

12].

Recent developments have introduced softer, resorbable IM nails as a more physiological alternative to titanium hardware. PLGA nails are capable of eliminating the need for implant removal surgery, reducing the risk of complications associated with a second operation. BIN implants dissolve within the bone over time, avoiding a second anesthesia, imaging-related ionization, emotional distress, and the financial burden of an additional procedure [

22]. However, despite these promising benefits, employing bioabsorbable implants is not without challenges, particularly in terms of surgical technique and potential complications.

In this study, we observed seven difficulties associated with the usage of BINs, specifically to the surgical technigue, in the treatment of pediatric forearm fractures out of 161 scenarios. For example, in one instance, the introduction of the implant was hindered by inadequate preparation, leading to cortical perforation. This difficulty can also occur during traditional elastic nailing. Despite their higher flexibility, implant failure can occur in the form of apical splitting during forced introduction. Such iatrogenic complications highlight the importance of precise preoperative planning and intraoperative caution when utilizing PLGA implants. Using an appropriately sized dilator and careful preparation of the medullary cavity are essential to avoid these consequences.

In two other children, unique anatomical variations in the shape of the medullary cavity itself posed as obstacles, as the cavity narrowed in a sandglass-like shape, or diffusely, along the whole organ, preventing the smooth passage of the implant. Therefore, preparing for subtle yet significant morphological variations in pediatric forearm anatomy can substantially impact the success of the procedure. Preoperative imaging and measurements of the medullary cavity are crucial in determining whether BINs can be used effectively in each individual.

While bioabsorbable nails offer a promising option, potential complications such as refracture and secondary malalignment must be monitored for years. In our cohort, a patient experienced secondary malalignment, although, the fracture healed with good callus formation and no significant functional deficits. Refracture occurred in two patients who had initially been treated with bioabsorbable implants, necessitating further surgical interventions. In both cases, the fracture was caused by repeated high-energy trauma not related to the implant. In one child, the injury occurred after a fall from a trampoline, while in the other, the fracture happened during biking.Consequently, while PLGA-based IM nails may be a suitable option for many pediatric forearm fractures, careful patient selection and follow-up are necessary to avoid and detect complications early and ensure proper healing.

Limitations of this trial include its non-comparative nature, low population, lack of randomization, and blinding. Advanced imaging could have revealed further aspects, like resorption rates and precise morphology [

25]. Other techniques for measuring blood flow, color, and elasticity have been developed to objectively evaluate scar tissue, however, due to the generally excellent cosmetic results after minimally invasive procedures, these tests were not performed [

29].

In a nutshell, while the increased utilization of BINs in pediatric forearm fractures offers potential benefits (reduced anesthesia and radiation dosage, child distress, LOS, and costs), it is not without its challenges. Medullary cavity anatomy variability and the potential for surgical and other complications such as implant failure, cortical perforation, and refracture must be carefully considered when choosing the appropriate treatment method. Further long-term, randomized-controlled studies are needed to better understand the long-term outcomes and complications associated with PLGA implants, as well as to refine the surgical techniques required to minimize complications in pediatric fractures.

5. Conclusions

BINs represent an innovative alternative to traditional titanium ESINs for pediatric diaphyseal forearm fractures, offering the distinct advantage of eliminating implant removal surgery. However, their successful application is contingent upon precise surgical execution and a profound understanding of medullary cavity anatomy. We systematically documented the intraoperative difficulties, highlighting key challenges such as cortical perforation, implant splitting, and obstruction due to focal or generalized medullary stenosis. Morphological variations in pediatric medullary cavity diameter necessitate precise preoperative imaging and implant selection, as improper planning can render implantation unfeasible. Secondary complications, including malalignment and refracture, emphasize the need for vigilant follow-up to assess biomechanical stability throughout the bone-healing process. The difficulties and complications are independent of the implant. We would like to draw attention to the technical challenge. A well-executed surgical technique leads to good results, as we have demonstrated in our previous publications.

Despite the theoretical advantages of gradual biodegradation aligning with fracture healing timelines, refracture occurrences (1.24% of all cases) raise concerns about the mechanical resilience of PLGA-based BINs. Therefore, while these implants offer a promising step toward minimally invasive pediatric fracture management, their application should be reserved for carefully selected cases where anatomical suitability and psychological compliance are confirmed. Surgical refinements, including optimized, patient-tailored implant design and improved insertion techniques, are imperative to mitigate complications and enhance functional outcomes. Well-planned surgical technique training can minimize risks related to BINs, further supporting their safe and effective use. Future longitudinal studies should assess the long-term biomechanical integrity of bioabsorbable materials in pediatric traumatology, ensuring that innovation does not compromise structural stability in the pursuit of surgical convenience.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.L., G.J., M.V. and T.K.; methodology, A.G.L., Á.L.D., E.A., and Z.T.; validation, A.G.L., Á.L.D., E.A., H.N., G.J., T.M. and Z.T.; formal analysis, A.L., A.G.L. and Á.L.D.; investigation, A.G.L., E.A., G.J., T.M. and Z.T.; resources, G.J. and Z.T.; data curation, A.G.L., Á.L.D., E.A., H.N.; writing—original draft preparation, A.L. and G.J.; writing—review and editing, A.L., A.G.L., Á.L.D., E.A., H.N., G.J., M.V., T.K., T.M., and Z.T; visualization, A.L., A.G.L., H.N., M.V. and T.K; supervision, G.J., M.V., T.K. and Z.T.; project administration, A.L., G.J., M.V. and T.K.; funding acquisition, G.J., M.V., and T.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. The authors are in agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Regional Research Ethics Committee, Clinical Complex, University of Pécs (Pécsi Tudományegyetem, Klinikai Komplex, Regionális és Intézményi Kutatás-Etikai Bizottság) on 23 April 2021 (8737-PTE2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient’s guardians to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Acknowledgements

We would like the thank the healthcare personnel of every Pediatric Hospital for their rigorous and conscientious efforts.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lyons, R.A.; Delahunty, A.M.; Kraus, D.; Heaven, M.; McCabe, M.; Allen, H.; Nash, P. Children’s Fractures: A Population Based Study. Inj. Prev. 1999, 5, 129–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schieber, R.A.; Branche-Dorsey, C.M.; Ryan, G.W.; Rutherford, G.W.; Stevens, J.A.; O’Neil, J. Risk Factors for Injuries from In-Line Skating and the Effectiveness of Safety Gear. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996, 335, 1630–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joeris, A.; Lutz, N.; Blumenthal, A.; Slongo, T.; Audigé, L. The AO Pediatric Comprehensive Classification of Long Bone Fractures (PCCF). Acta Orthop. 2017, 88, 129–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caruso, G.; Caldari, E.; Sturla, F.D.; Caldaria, A.; Re, D.L.; Pagetti, P.; Palummieri, F.; Massari, L. Management of Pediatric Forearm Fractures: What Is the Best Therapeutic Choice? A Narrative Review of the Literature. Musculoskelet. Surg. 2021, 105, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, J.M. Pediatric Forearm Fractures: Decision Making, Surgical Techniques, and Complications. Instr. Course Lect. 2002, 51, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Noonan, K.J.; Price, C.T. Forearm and Distal Radius Fractures in Children. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 1998, 6, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lascombes, P.; Prevot, J.; Ligier, J.N.; Metaizeau, J.P.; Poncelet, T. Elastic Stable Intramedullary Nailing in Forearm Shaft Fractures in Children: 85 Cases. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 1990, 10, 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmittenbecher, P.P. State-of-the-Art Treatment of Forearm Shaft Fractures. Injury 2005, 36 (Suppl. S1), A25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubiak, R.; Aksakal, D.; Weiss, C.; Wessel, L.M.; Lange, B. Is There a Standard Treatment for Displaced Pediatric Diametaphyseal Forearm Fractures?: A STROBE-Compliant Retrospective Study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019, 98, e16353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.-N.; Mangwani, J.; Ramachandran, M.; Paterson, J.M.H.; Barry, M. Elastic Intramedullary Nailing of Paediatric Fractures of the Forearm: A DECADE OF EXPERIENCE IN A TEACHING HOSPITAL IN THE UNITED KINGDOM. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 2011, 93-B, 262–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, M.C.; Roy, D.R.; Giza, E.; Crawford, A.H. Complications of Intramedullary Fixation of Pediatric Forearm Fractures. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 1998, 18, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, F.F.; Langendörfer, M.; Wirth, T.; Eberhardt, O. Failures and Complications in Intramedullary Nailing of Children’s Forearm Fractures. J. Child. Orthop. 2010, 4, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooker, B.; Harris, P.C.; Donnan, L.T.; Graham, H.K. Rupture of the Extensor Pollicis Longus Tendon Following Dorsal Entry Flexible Nailing of Radial Shaft Fractures in Children. J. Child. Orthop. 2014, 8, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieber, J.; Dietzel, M.; Scherer, S.; Schäfer, J.F.; Kirschner, H.-J.; Fuchs, J. Implant Removal Associated Complications after ESIN Osteosynthesis in Pediatric Fractures. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 2022, 48, 3471–3478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheider, P.; Ganger, R.; Farr, S. Complications of Hardware Removal in Pediatric Upper Limb Surgery: A Retrospective Single-Center Study of 317 Patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020, 99, e19010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Was tun, wenn die elastisch-stabile intramedulläre Nagelung (ESIN) an ihre Grenzen stößt? | springermedizin.de. Available online: https://www.springermedizin.de/was-tun-wenn-die-elastisch-stabile-intramedullaere-nagelung-esin/8702902 (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Lieber, J.; Joeris, A.; Knorr, P.; Schalamon, J.; Schmittenbecher, P. ESIN in Forearm Fractures. Eur. J. Trauma 2005, 31, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.; Li, L.; Anand, A. Systematic Review: Functional Outcomes and Complications of Intramedullary Nailing versus Plate Fixation for Both-Bone Diaphyseal Forearm Fractures in Children. Injury 2014, 45, 1135–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousset, M.; Mansour, M.; Samba, A.; Pereira, B.; Canavese, F. Risk Factors for Re-Fracture in Children with Diaphyseal Fracture of the Forearm Treated with Elastic Stable Intramedullary Nailing. Eur. J. Orthop. Surg. Traumatol. Orthop. Traumatol. 2016, 26, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieber, J.; Sommerfeldt, D.W. [Diametaphyseal forearm fracture in childhood. Pitfalls and recommendations for treatment]. Unfallchirurg 2011, 114, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, K.; Morrison, M.J.; Tomlinson, L.A.; Ramirez, R.; Flynn, J.M. Both Bone Forearm Fractures in Children and Adolescents, Which Fixation Strategy Is Superior - Plates or Nails? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. J. Orthop. Trauma 2014, 28, e8–e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lőrincz, A.; Lengyel, Á.M.; Kedves, A.; Nudelman, H.; Józsa, G. Pediatric Diaphyseal Forearm Fracture Management with Biodegradable Poly-L-Lactide-Co-Glycolide (PLGA) Intramedullary Implants: A Longitudinal Study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roeder, C.; Alves, C.; Balslev-Clausen, A.; Canavese, F.; Gercek, E.; Kassai, T.; Klestil, T.; Klingenberg, L.; Lutz, N.; Varga, M.; et al. Pilot Study and Preliminary Results of Biodegradable Intramedullary Nailing of Forearm Fractures in Children. Children 2022, 9, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Józsa, G.; Kassai, T.; Varga, M. Preliminary Experience with Bioabsorbable Intramedullary Nails for Paediatric Forearm Fractures: Results of a Mini-Series. Genij Ortop. 2023, 29, 640–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perhomaa, M.; Pokka, T.; Korhonen, L.; Kyrö, A.; Niinimäki, J.; Serlo, W.; Sinikumpu, J.-J. Randomized Controlled Trial of the Clinical Recovery and Biodegradation of Polylactide-Co-Glycolide Implants Used in the Intramedullary Nailing of Children’s Forearm Shaft Fractures with at Least Four Years of Follow-Up. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gentile, P.; Chiono, V.; Carmagnola, I.; Hatton, P.V. An Overview of Poly(Lactic-Co-Glycolic) Acid (PLGA)-Based Biomaterials for Bone Tissue Engineering. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 3640–3659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppley, B.L.; Reilly, M. Degradation Characteristics of PLLA-PGA Bone Fixation Devices. J. Craniofac. Surg. 1997, 8, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korhonen, L.; Perhomaa, M.; Kyrö, A.; Pokka, T.; Serlo, W.; Merikanto, J.; Sinikumpu, J.-J. Intramedullary Nailing of Forearm Shaft Fractures by Biodegradable Compared with Titanium Nails: Results of a Prospective Randomized Trial in Children with at Least Two Years of Follow-Up. Biomaterials 2018, 185, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaspers, M.E.H.; Moortgat, P. Objective Assessment Tools: Physical Parameters in Scar Assessment. In Textbook on Scar Management: State of the Art Management and Emerging Technologies; Téot, L., Mustoe, T.A., Middelkoop, E., Gauglitz, G.G., Eds.; Springer: Cham (CH), 2020 ISBN 978-3-030-44765-6.

Figure 1.

Primary X-rays of a distal diaphyseal forearm fracture from anteroposterior (AP) and lateral views (B). After the insertion of the dilator (blue line), the opposite cortical was perforated (red line). Following this intraoperative complication, elastic nails were inserted, and both bones were stabilized with ESINs. Postoperative X-ray demonstrates good alignment (C).

Figure 1.

Primary X-rays of a distal diaphyseal forearm fracture from anteroposterior (AP) and lateral views (B). After the insertion of the dilator (blue line), the opposite cortical was perforated (red line). Following this intraoperative complication, elastic nails were inserted, and both bones were stabilized with ESINs. Postoperative X-ray demonstrates good alignment (C).

Figure 2.

Preoperative X-rays from AP (A) and lateral (B) aspects of a both-bone diaphyseal forearm fracture. A magnified image shows the measurement of the medullary canal both distal and proximal to the fracture (C). Both bones were stabilized with elastic nails, visible from AP (D) and lateral (E) views.

Figure 2.

Preoperative X-rays from AP (A) and lateral (B) aspects of a both-bone diaphyseal forearm fracture. A magnified image shows the measurement of the medullary canal both distal and proximal to the fracture (C). Both bones were stabilized with elastic nails, visible from AP (D) and lateral (E) views.

Figure 3.

Initial X-rays of the diaphyseal forearm fracture (lateral (A), AP (B)) and the split end of the resorbable IM nail (C). Postoperative images (lateral (D), AP (F)) show good alignment of the bones, but the magnified AP view (E) demonstrates a two mm displacement of the radius, which caused the injury of the implant. .

Figure 3.

Initial X-rays of the diaphyseal forearm fracture (lateral (A), AP (B)) and the split end of the resorbable IM nail (C). Postoperative images (lateral (D), AP (F)) show good alignment of the bones, but the magnified AP view (E) demonstrates a two mm displacement of the radius, which caused the injury of the implant. .

Figure 4.

Postoperative X-rays depict the fracture stabilization in good alignment. The β-TCP marker is visible in the radius at the level of the diaphysis, two cm proximal to the fracture site. The cause is visible in the magnified image, where the medullary cavity narrows, creating a sandglass effect.

Figure 4.

Postoperative X-rays depict the fracture stabilization in good alignment. The β-TCP marker is visible in the radius at the level of the diaphysis, two cm proximal to the fracture site. The cause is visible in the magnified image, where the medullary cavity narrows, creating a sandglass effect.

Figure 5.

Preoperative (from AP (A) and lateral (B) views), and immediately postoperative (AP (C), lateral (D)), control radiographs. Follow-up X-rays were taken one week (AP (E), lateral (F)), eight weeks (AP (G), lateral (H)), and six months postoperatively (AP (I), lateral (J)), exhibiting good callus formation and remodeling. The patient showed a 10° deficit in left wrist supination (K), with no deficit in pronation (L).

Figure 5.

Preoperative (from AP (A) and lateral (B) views), and immediately postoperative (AP (C), lateral (D)), control radiographs. Follow-up X-rays were taken one week (AP (E), lateral (F)), eight weeks (AP (G), lateral (H)), and six months postoperatively (AP (I), lateral (J)), exhibiting good callus formation and remodeling. The patient showed a 10° deficit in left wrist supination (K), with no deficit in pronation (L).

Figure 6.

Control X-rays four weeks postoperatively showed good alignment from AP (A) and lateral (B) aspects. Radiographs at re-presentation eight weeks postoperatively, indicated refracture (AP (C), lateral (D)). Control X-rays after cast application upon re-presentation with refracture, showing good alignment (AP (E), lateral (F)). Follow-up radiographs taken six months postoperatively indicate adequate fracture healing (AP (G), lateral (H)).

Figure 6.

Control X-rays four weeks postoperatively showed good alignment from AP (A) and lateral (B) aspects. Radiographs at re-presentation eight weeks postoperatively, indicated refracture (AP (C), lateral (D)). Control X-rays after cast application upon re-presentation with refracture, showing good alignment (AP (E), lateral (F)). Follow-up radiographs taken six months postoperatively indicate adequate fracture healing (AP (G), lateral (H)).

Figure 7.

Markers are visible in both bones two years after the primary treatment with BINs (lateral (A), AP (B)). Postoperative X-rays show the perfect alignment of the forearm, stabilized with ESINs (AP (C), lateral (D)).

Figure 7.

Markers are visible in both bones two years after the primary treatment with BINs (lateral (A), AP (B)). Postoperative X-rays show the perfect alignment of the forearm, stabilized with ESINs (AP (C), lateral (D)).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).