1. Introduction

1.1. The Challenge of Soil Variability in Agrochemical Management

Every year, the world loses an area of arable land to salinization equivalent to the size of Costa Rica, threatening the livelihoods of over a billion people. This silent crisis, which costs the global economy over

$27 billion annually, has historically outpaced our ability to monitor and manage it. Today, however, a new paradigm is emerging of integrating Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Remote Sensing (RS). Modern agriculture depends critically on agrochemicals—including fertilizers, soil conditioners, and plant protection products—to meet global food demands for a population projected to reach around 9.7 billion by 2050 [

1]. However, the efficacy of these inputs is fundamentally constrained by the inherent spatial and temporal heterogeneity of agricultural soils [

2]. Conventional management practices, which typically employ uniform or blanket applications of agrochemicals across entire fields, systematically disregard this variability. This oversight produces substantial inefficiencies: over-application in naturally productive zones increases input costs, degrades soil structure, and drives agrochemical runoff into adjacent watersheds and groundwater reservoirs. Conversely, under-application in intrinsically deficient areas limits yield potential, compromises pest and disease control efficacy, and represents a significant missed opportunity for optimal crop productivity [

3].

Soil salinization represents a particularly acute manifestation of this management challenge. Current estimates indicate that saline and salt-affected soils encompass approximately 1.1 billion hectares globally, representing roughly 6% of all land area and accounting for approximately 20% of irrigated agricultural land [

4]. This phenomenon generates annual economic losses exceeding

$27 billion and threatens food security in vulnerable regions, particularly across Asia, Africa, and the Middle East [

5]. Beyond direct economic impacts, soil salinity mechanisms include osmotic stress that impedes plant water uptake, ionic toxicity from sodium and chloride accumulation in plant tissues, and complex nutrient imbalance involving calcium, potassium, and magnesium [

6]. Furthermore, high salt concentrations significantly alter the bioavailability and efficacy of soil-applied pesticides and herbicides by modifying soil matrix interactions, pH conditions, and microbial degradation rates [

7]. The multifaceted nature of salt-affected soil constraints substantially exceeds the diagnostic capacity of traditional soil assessment methodologies.

1.2. Limitations of Conventional Assessment Methodologies

Traditional soil salinity assessment has long relied on manual field sampling combined with laboratory analysis of electrical conductivity (ECe), establishing the methodological gold standard established by the U.S. Salinity Laboratory [

8]. Despite providing excellent accuracy for individual sampling points, these conventional approaches face practical limitations for large-scale, spatially-explicit agricultural management. Specifically, labor-intensive field campaigns prove prohibitively expensive, with comprehensive spatial coverage often requiring multiple samples per hectare at costs exceeding

$100 USD per hectare [

9]. More critically, these point-based measurements provide only temporal snapshots disconnected from the dynamic processes governing soil development, water movement, and chemical transformations across fields [

10]. The resulting sparse spatial data cannot adequately capture field-scale heterogeneity or seasonal variability, rendering these datasets inadequate for guiding modern precision-based agrochemical applications. This fundamental methodological gap has necessitated development of innovative technological solutions capable of providing continuous, spatially-explicit monitoring at landscape scales.

1.3. The Paradigm Shift: Integration of AI and Remote Sensing for Precision Agriculture

The convergence of Artificial Intelligence and Remote Sensing technologies presents a transformative solution, enabling a fundamental paradigm shift from reactive, uniform treatments toward proactive, spatially-explicit, and temporally-dynamic precision management of agrochemicals [

11]. This technological synergy provides the essential capability to monitor soil properties continuously, cost-effectively, and across landscape scales previously inaccessible through conventional methods. Contemporary satellite platforms including Landsat-8/9 and Sentinel-2, when coupled with sophisticated machine learning and deep learning algorithms, can translate vast streams of multispectral and hyperspectral data into actionable intelligence for farmers, agronomists, and land managers [

12]. This review comprehensively explores the evolving AI-RS framework, critically assesses current technological capabilities and limitations, and delineates the transformative potential of this approach for redefining sustainable agrochemical use and enhancing global food security. This will add to the effectiveness of precision nutrient management and integrated soil fertility systems.

2. The Technological Revolution in Soil Monitoring: Remote Sensing Platforms and Data Acquisition

2.1. Multispectral and Hyperspectral Remote Sensing Systems

The technological foundation for large-scale soil monitoring rests upon an expanding constellation of earth observation satellites providing consistent, high-frequency data streams.

Multispectral Satellite Systems: The Landsat series (particularly Landsat-8/9 Operational Land Imager) and the European Sentinel-2 constellation represent the primary operational platforms for soil monitoring applications [

13]. These systems deliver spatial resolutions ranging from 10 to 30 meters with revisit frequencies between 5 to 16 days, providing optimal balance among spatial detail, temporal frequency, and economic feasibility [

14]. Their multispectral capabilities encompassing visible, near-infrared (NIR), and shortwave infrared (SWIR) spectral regions demonstrate exceptional sensitivity to soil health indicators including vegetation stress (chlorophyll absorption in red wavelengths contrasted against NIR reflectance), moisture content (water absorption features in SWIR bands), and surface salt manifestations [

15]. Spectral indices derived from these bands—particularly the Normalized Difference Salinity Index (NDSI), Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), and Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI)—provide robust initial indicators for identifying zones with potential soil constraints [

16]. Recent studies have demonstrated that Sentinel-2 data, freely available through the Copernicus program, enables detection of soil salinity variations with spatial resolution superior to previous Landsat capabilities [

17].

Hyperspectral Remote Sensing Technology: Hyperspectral sensors represent a new frontier in soil and vegetation observation, capturing reflectance data across hundreds of narrow, contiguous spectral bands typically spanning 0.4–2.5 µm [

18]. This exceptionally high spectral resolution enables the detection of subtle biochemical and biophysical variations in vegetation—particularly shifts in the red-edge region—caused by soil stress well before visual symptoms appear [

19]. Importantly, hyperspectral data allows the direct identification of mineral constituents and salt formations through their unique spectral absorption and reflectance features [

20]. Traditionally, hyperspectral observations were restricted to airborne systems such as AVIRIS and ROSIS; however, recent advances in spaceborne missions—including EnMAP (Environmental Mapping and Analysis Program), PRISMA (PRecursore IperSpettrale della Missione Applicativa), and the upcoming CHIME (Copernicus Hyperspectral Imaging Mission for the Environment)—are democratizing access to high-quality hyperspectral imagery for large-scale and routine agricultural monitoring [

21]. Integrating hyperspectral data with machine learning algorithms shows significant promise for diagnosing complex soil conditions that previously required extensive field validation [

22].

Table 1 provides a comparative overview of major remote sensing platforms used in agricultural soil monitoring, highlighting their spatial and temporal resolution, spectral capabilities, data accessibility, and principal applications. These performance metrics and operational considerations are essential for selecting the most suitable platform for specific agrochemical management objectives.

Table 1.

Comparative Performance Characteristics of Remote Sensing Platforms for Soil Monitoring.

Table 1.

Comparative Performance Characteristics of Remote Sensing Platforms for Soil Monitoring.

| Platform |

Spatial Resolution |

Revisit Frequency |

Spectral Bands |

Cost |

Coverage |

Primary Application |

Limitations |

|

Landsat-8/9 (OLI/TIRS)

|

30 m (panchromatic 15 m) |

16 days |

11 (VIS–NIR–SWIR–TIR) |

Free |

Global |

Landscape-scale soil salinity and land degradation mapping |

Moderate spatial resolution; cloud interference in humid regions |

|

Sentinel-2A/B (MSI)

|

10–60 m |

5 days (combined) |

13 (VIS–NIR–SWIR) |

Free |

Global |

Field-scale vegetation, salinity, and nutrient-stress indices |

Cloud sensitivity; no thermal band |

|

Sentinel-1 (SAR)

|

10 m |

6–12 days |

Dual-/Quad-polarization (C-band) |

Free |

Global |

Soil-moisture and surface-roughness mapping; all-weather imaging |

Complex preprocessing and interpretation |

|

EnMAP (Germany)

|

30 m |

~4 days (targeted) |

242 (VIS–NIR–SWIR, 0.42–2.45 µm) |

Free for research / Low-cost commercial |

Global |

Hyperspectral mineral, salinity, and vegetation-stress detection |

Very large data volume; moderate spatial detail |

|

PRISMA (Italy)

|

30 m |

25–29 days |

235 (VIS–NIR–SWIR, 0.4–2.5 µm) |

Free for scientific use / Commercial license |

Global |

Detailed soil composition and vegetation biochemistry |

Limited temporal coverage; narrow swath |

|

PlanetScope (Dove)

|

3–5 m |

Daily |

4 (RGB–NIR) |

Commercial (subscription) |

Global |

Daily crop-status and soil-surface monitoring |

Limited spectral depth; higher recurring cost |

|

WorldView-3 (Maxar)

|

0.3 m (pan); 1.2–3.7 m (MS/SWIR) |

< 1 day (tasked) |

29 (VIS–NIR–SWIR) |

Commercial (high-cost) |

Global (tasked) |

Ultra-high-resolution validation and DEM generation |

Small swath; high tasking cost |

|

UAV-Multispectral

|

1–5 cm |

On-demand |

4–8 (sensor-dependent) |

≈ US $ 500 – 5 000 per unit |

Field-scale |

Detailed field monitoring, validation, and ground-truthing |

Limited coverage area; frequent calibration needed |

|

UAV-Hyperspectral

|

1–10 cm |

On-demand |

100–400 (sensor-dependent) |

≈ US $ 50 000 – 200 000 per system |

Field-scale |

High-precision mineral/stress detection and micro-variability mapping |

High acquisition cost; limited endurance (20–40 min flight time) |

2.2. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles and High-Resolution Imaging

Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) equipped with multispectral, hyperspectral, and thermal sensors have emerged as crucial intermediate-scale monitoring platforms, bridging the gap between satellite data and ground-truth measurements [

23]. UAVs provide spatial resolutions of 1-5 centimeters at field scales, enabling detection of fine-scale soil variability and localized salt efflorescence [

24]. This capability proves particularly valuable for validation studies, targeted scouting missions, and high-frequency monitoring during critical crop growth stages. Recent advances in UAV payload integration—including lightweight hyperspectral sensors and LiDAR systems—expand the range of soil and crop parameters measurable from airborne platforms [

25]. The combination of satellite data at landscape scale, UAV data at field scale, and ground sensors at point scale creates a hierarchical monitoring framework capable of capturing soil processes across multiple spatial scales [

26].

2.3. Synthetic Aperture Radar and All-Weather Capabilities

Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) systems including Sentinel-1, ALOS-2, and TerraSAR-X provide critical all-weather monitoring capabilities by penetrating cloud cover and detecting subtle surface moisture variations [

27]. SAR data proves invaluable in tropical and coastal agricultural zones where persistent cloud cover limits optical satellite utility [

28]. Recent research demonstrates that SAR-derived soil moisture estimates, when integrated with optical data through multi-sensor fusion approaches, substantially improve model performance for predicting soil salinity and determining irrigation requirements [

29]. The temporal coherence patterns in SAR data additionally enable detection of subsurface features and soil water redistribution following irrigation or precipitation events [

30].

2.4. Internet of Things Sensor Networks

Ground-based IoT sensor networks complement satellite and aerial observations by providing continuous, in situ measurements of soil properties [

31]. Wireless sensor networks measuring soil moisture, electrical conductivity, temperature, and nutrient concentrations at multiple depths create near-real-time data streams suitable for model calibration, validation, and operational decision support [

32]. The integration of low-cost IoT sensors with satellite data through data assimilation techniques enables enhanced spatial interpolation and prediction accuracy [

33]. Recent developments in soil-deployed IoT systems demonstrate improved durability, reduced maintenance requirements, and decreased costs, making large-scale deployment increasingly feasible for smallholder farming systems [

34].

3. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning for Soil Property Prediction

3.1. Machine Learning Algorithms and Soil Salinity Classification

Machine learning algorithms have demonstrated remarkable capability for translating multispectral satellite data into accurate soil property predictions [

35]. Random Forest (RF) and Support Vector Machines (SVM) represent particularly robust approaches, with reported overall accuracies typically ranging between 80% and 95% depending on data quality, feature engineering, and regional environmental conditions [

36]. These models excel at identifying complex, non-linear relationships between spectral indices and ground-truth soil measurements, accommodating the inherent complexity of soil-plant-water-atmosphere interactions [

37]. Recent comparative studies indicate that ensemble methods combining multiple algorithms through weighted voting schemes achieve superior performance compared to individual algorithms [

38].

Random Forest algorithms, through their recursive partitioning and bootstrap aggregation approaches, prove particularly adept at handling high-dimensional spectral datasets and managing feature interactions [

39]. SVM models, with appropriate kernel selection and hyperparameter optimization, excel at classification tasks in scenarios with limited training data [

40]. Modern implementations incorporating cross-validation frameworks and uncertainty quantification enable practitioners to assess prediction confidence and identify regions requiring additional ground validation [

41].

3.2. Deep Learning Architectures for Spectral Pattern Recognition

Deep learning models—particularly Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)—represent a transformative advance in the analysis of remote sensing data, enabling the automatic extraction of spatial and spectral patterns directly from raw satellite imagery [

42]. Unlike traditional machine learning approaches that rely on manual feature engineering, CNNs autonomously learn hierarchical representations of spectral information, progressively identifying complex and abstract features that are strongly predictive of soil properties [

43]. This capability is especially advantageous for hyperspectral datasets comprising hundreds of spectral bands, where manual feature selection is not only computationally intensive but also risks omitting critical information [

44].

Table 2 summarizes the comparative performance of major machine learning and deep learning algorithms in predicting soil salinity, moisture, and nutrient status from remote sensing data. Reported metrics include overall accuracy, producer’s and user’s accuracy, the Kappa coefficient, and computational efficiency. Model performance is influenced by the size and quality of the training dataset, regional heterogeneity, and the degree of hyperparameter optimization.

Table 2.

Performance Comparison of Machine Learning and Deep Learning Algorithms for Soil Property Prediction.

Table 2.

Performance Comparison of Machine Learning and Deep Learning Algorithms for Soil Property Prediction.

| Algorithm / Model Type |

Overall Accuracy (%) |

Kappa Coefficient |

Training Time |

Computational Requirement |

Data Requirement (size & type) |

Interpretability |

Typical Use Case / Best Scenario |

| Random Forest (RF) |

82 – 92 |

0.80 – 0.90 |

Medium |

Low – Medium (CPU) |

Moderate (≥ 1 000 samples per region) |

High (feature importance accessible) |

Baseline model; heterogeneous datasets; quick deployment |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) |

80 – 90 |

0.78 – 0.88 |

Medium |

Medium (CPU/GPU optional) |

Small – Moderate (500 – 5 000 samples) |

Medium (kernel-dependent) |

Non-linear classification; limited training data regions |

| Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost / CatBoost) |

84 – 93 |

0.81 – 0.91 |

Short – Medium |

Medium |

Moderate |

Medium – High |

High-speed tabular modeling; benchmark for spectral indices |

| Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) |

88 – 95 |

0.86 – 0.93 |

Long |

High (GPU) |

Large (≥ 5 000 – 50 000 image tiles) |

Low (black-box features) |

Spatial pattern recognition; hyperspectral imagery analysis |

| Recurrent / LSTM Networks |

86 – 94 |

0.84 – 0.92 |

Long |

High (GPU) |

Time-series satellite data (> 3 years) |

Low – Medium |

Temporal soil-moisture dynamics; climate response modelling |

| Physics-Informed Neural Network (PINN) |

89 – 96 |

0.87 – 0.95 |

Long |

High (GPU) |

Small – Medium (physics-constrained datasets) |

Medium – High |

Data-scarce regions; process-based salinity and hydrology prediction |

| Ensemble / Hybrid Methods |

90 – 97 |

0.89 – 0.96 |

Medium – Long |

Medium – High |

Moderate – Large (multi-source fusion) |

Medium |

Operational systems; robustness across regions |

| Transfer Learning (CNN-based) |

85 – 94 |

0.83 – 0.92 |

Short |

Low – Medium (GPU optional) |

Small (100 – 500 target samples) |

Low |

New geographic regions with limited ground-truth data |

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) architectures extend deep learning capabilities to the temporal domain, allowing analysis of time-series satellite imagery to capture dynamic soil responses to rainfall, irrigation, and seasonal variability [

45]. Attention mechanisms integrated within deep learning frameworks enable models to assign differential weights to spectral bands and temporal intervals based on their predictive significance, thereby enhancing both interpretability and accuracy [

46]. Recent advancements involving Vision Transformers and self-attention architectures have yielded promising outcomes in soil property prediction, particularly under conditions with limited labeled training data [

47].

Figure 1 illustrates an example of the the integrated workflow of the AI–remote sensing pipeline for precision agrochemical management. The cyclical process begins with satellite data acquisition from multispectral platforms (e.g., Landsat-8/9, Sentinel-2) and hyperspectral sensors, followed by atmospheric correction and cloud masking. The preprocessed imagery is then ingested into trained machine learning and deep learning models calibrated with ground-truth soil measurements. These AI models generate predictive soil condition maps that depict spatial variability in salinity, moisture, and nutrient concentrations. The resulting outputs are converted into prescription maps that define variable application rates for distinct management zones. GPS-guided agricultural machinery reads these prescription maps in real time, automatically adjusting agrochemical dosages as equipment moves across the field. Subsequent monitoring through in-field sensors and satellite revisits validates application outcomes and informs adaptive management strategies for future cultivation cycles.

Figure 1.

Integrated AI-RS Workflow for Precision Agrochemical Management.

Figure 1.

Integrated AI-RS Workflow for Precision Agrochemical Management.

3.3. Physics-Informed Neural Networks and Process Integration

Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) represent an emerging frontier integrating mechanistic soil-water-solute transport equations with deep learning architectures [

48]. Rather than treating soil parameters as independent variables, PINNs embed fundamental physical principles governing water movement, salt transport, and nutrient dynamics directly into the model architecture [

49]. This hybrid approach maintains scientific consistency while leveraging the predictive power of machine learning, proving particularly valuable in data-scarce regions or heterogeneous environments where purely empirical algorithms struggle with generalization [

50]. PINN applications for soil salinity prediction demonstrate improved spatial transferability compared to conventional machine learning, enabling more reliable predictions in regions with limited training data [

51].

3.4. Transfer Learning and Model Generalization

Transfer learning approaches, in which models pre-trained on large, well-characterized datasets are fine-tuned for new local conditions, significantly accelerate the deployment of AI–RS technologies in data-scarce and under-resourced regions [

52]. Domain adaptation methods further enhance model robustness by enabling algorithms trained for specific geographic areas or crop types to perform effectively in different environmental and agronomic contexts [

53]. Federated learning frameworks facilitate collaborative model development across multiple farms and regions while maintaining data privacy, allowing decentralized learning without transferring sensitive local datasets [

54]. These approaches have proven particularly valuable for smallholder farmers in developing nations, where limited access to labeled training data constrains conventional model development [

55].

Figure 2 presents the comparative accuracy performance of machine learning and deep learning algorithms for soil salinity prediction across different satellite data types and regional settings. (a) Overall accuracy (%) comparison among Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machine (SVM), Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), Physics-Informed Neural Network (PINN), and ensemble models applied to multispectral (Landsat-8/Sentinel-2) and hyperspectral datasets. (b) Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves illustrating each model’s ability to discriminate between saline and non-saline soil classes. (c) Prediction accuracy as a function of training data availability, highlighting the superior performance of transfer learning and PINN approaches in data-scarce scenarios. (d) Spatial distribution of prediction errors across geographic regions, underscoring the importance of model generalization and domain adaptation. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals derived from independent validation datasets.

Figure 2.

Comparative Accuracy Performance of AI Algorithms for Soil Salinity Prediction.

Figure 2.

Comparative Accuracy Performance of AI Algorithms for Soil Salinity Prediction.

4. Integration of AI-RS for Precision Agrochemical Management: Practical Implementation

4.1. Variable-Rate Application Technology and Field Implementation

The practical application of AI-RS soil maps centers on creating management zones for Variable Rate Application (VRA) of agrochemicals [

56]. This approach fundamentally departs from conventional uniform application, instead using high-resolution predictive maps to automatically adjust agrochemical application rates as equipment traverses fields [

57].

Fertilizer and Soil Conditioner Application: In saline or nutrient-deficient zones, targeted fertilizer application can be precisely increased to counteract reduced nutrient bioavailability, while in naturally productive zones, application can be systematically reduced to minimize costs and prevent environmental runoff [

58]. Field trials across diverse agroecosystems demonstrate this targeted approach reduces production costs by 15-30% while increasing yields by 8-15% [

59]. Soil conditioner application targeting saline zones improves soil structure and water-holding capacity specifically where needed, avoiding unnecessary application to already-productive areas [

60]. The economic benefits extend beyond input savings to include improved soil carbon sequestration in targeted zones and enhanced resilience to precipitation variability [

61].

Precision Plant Protection: Soil-induced crop stress, particularly salinity-driven osmotic stress, substantially increases vulnerability to pest and disease pressure [

62]. AI-RS systems identify these high-stress zones, enabling targeted scouting and spot-spraying of pesticides rather than blanket applications [

63]. This precision approach reduces overall pesticide volume by 20-40%, minimizes impacts on beneficial arthropods and soil microorganisms, and delays resistance development through reduced selection pressure [

64]. Integration of AI-RS soil mapping with phenological crop models enables prediction of peak pest vulnerability windows, further optimizing spray timing and dosage [

65].

Water Use Efficiency and Irrigation Scheduling: AI-guided irrigation scheduling informed by soil moisture and salinity data derived from satellite observations substantially improves water use efficiency, with demonstrated improvements of 25-40% compared to farmer-standard practices [

66]. This represents a critical benefit in water-scarce regions where irrigation represents both the primary water use and a major driver of soil salinization through preferential evaporation of applied water [

67]. Proper water management ensures soluble agrochemicals remain within the effective root zone rather than leaching into groundwater or concentrating in surface soil layers where salt accumulation occurs [

68]. Real-time integration of precipitation forecasts with soil moisture estimates enables dynamic irrigation scheduling that responds to natural rainfall, further conserving water resources [

69].

Table 3 shows economic analysis of AI-RS-guided precision agrochemical management compared to conventional uniform application practices across diverse agroecological contexts. Calculations based on large-scale implementation studies and farm-level assessments. Returns include input cost savings, yield improvements, and reduced environmental remediation costs. All values in USD per hectare per growing season. Economic viability depends on farm size, local commodity prices, input costs, technology adoption costs, and regional support programs.

Table 3.

Economic Analysis and Return-on-Investment of AI-RS Precision Agrochemical Management.

Table 3.

Economic Analysis and Return-on-Investment of AI-RS Precision Agrochemical Management.

| Cost/Benefit Component |

Conventional Management |

AI-RS Precision Management |

Net Change |

Payback Period |

| COSTS |

|

|

|

|

| Satellite data & processing |

$0-5 |

$5-15 |

+$5-15 |

Amortized |

| AI model development & validation

|

$0 (none) |

$10-30/farm (amortized) |

+$10-30 |

2-4 years |

| IoT sensor installation & maintenance |

$0 |

$20-50 |

+$20-50 |

3-5 years |

| Hardware upgrades (GPS-VRA equipment) |

$0 |

$100-300 (farm-level capital) |

+$100-300 |

4-8 years |

| Training & technical support |

$0-10 |

$10-20 |

+$10-20 |

1 year |

| TOTAL ANNUAL COST |

$0-15 |

$55-105 |

+$40-105 |

Initial phase |

| BENEFITS |

|

|

|

|

| Fertilizer savings (15-20% reduction) |

— |

$40-80 |

+$40-80 |

— |

| Pesticide/herbicide savings (20-40% reduction) |

— |

$30-60 |

+$30-60 |

— |

| Water cost savings (25-40% improvement) |

— |

$20-50 |

+$20-50 |

— |

| Yield increase (8-15% where constraints exist) |

— |

$50-200 |

+$50-200 |

— |

| Reduced groundwater remediation needs |

— |

$10-30 |

+$10-30 |

— |

| Carbon credit/ecosystem service payments

|

— |

$5-25 |

+$5-25 |

— |

| TOTAL ANNUAL BENEFIT

|

$0 |

$155-445 |

+$155-445 |

**— |

| NET ANNUAL RETURN |

— |

+$50-340 |

|

1-3 years |

| 5-Year NPV (10% discount) |

— |

+$190-1,290 |

|

— |

| Benefit-Cost Ratio |

— |

2.8-4.2:1 |

|

— |

4.2. Economic and Environmental Benefits Quantification

Comprehensive life-cycle assessments comparing conventional uniform management to AI-RS-guided precision approaches demonstrate substantial economic and environmental benefits [

70]. Input cost reductions totaling

$30-80 USD per hectare, combined with yield increases of 5-15% representing

$50-200 USD per hectare in additional revenue, produce total economic benefits of

$80-280 USD per hectare annually [

71]. These benefits prove particularly pronounced in saline and nutrient-deficient regions where spatial variability is greatest [

72]. Environmental benefits include reduced agrochemical runoff, improved groundwater quality, enhanced soil biological activity, and increased carbon sequestration in targeted soil amendment zones [

73]. The cumulative impact of widespread adoption could reduce global agrochemical use by 15-20% while maintaining or increasing productivity, producing substantial environmental benefits [

74].

4.3. Climate Change Adaptation and Food Security Enhancement

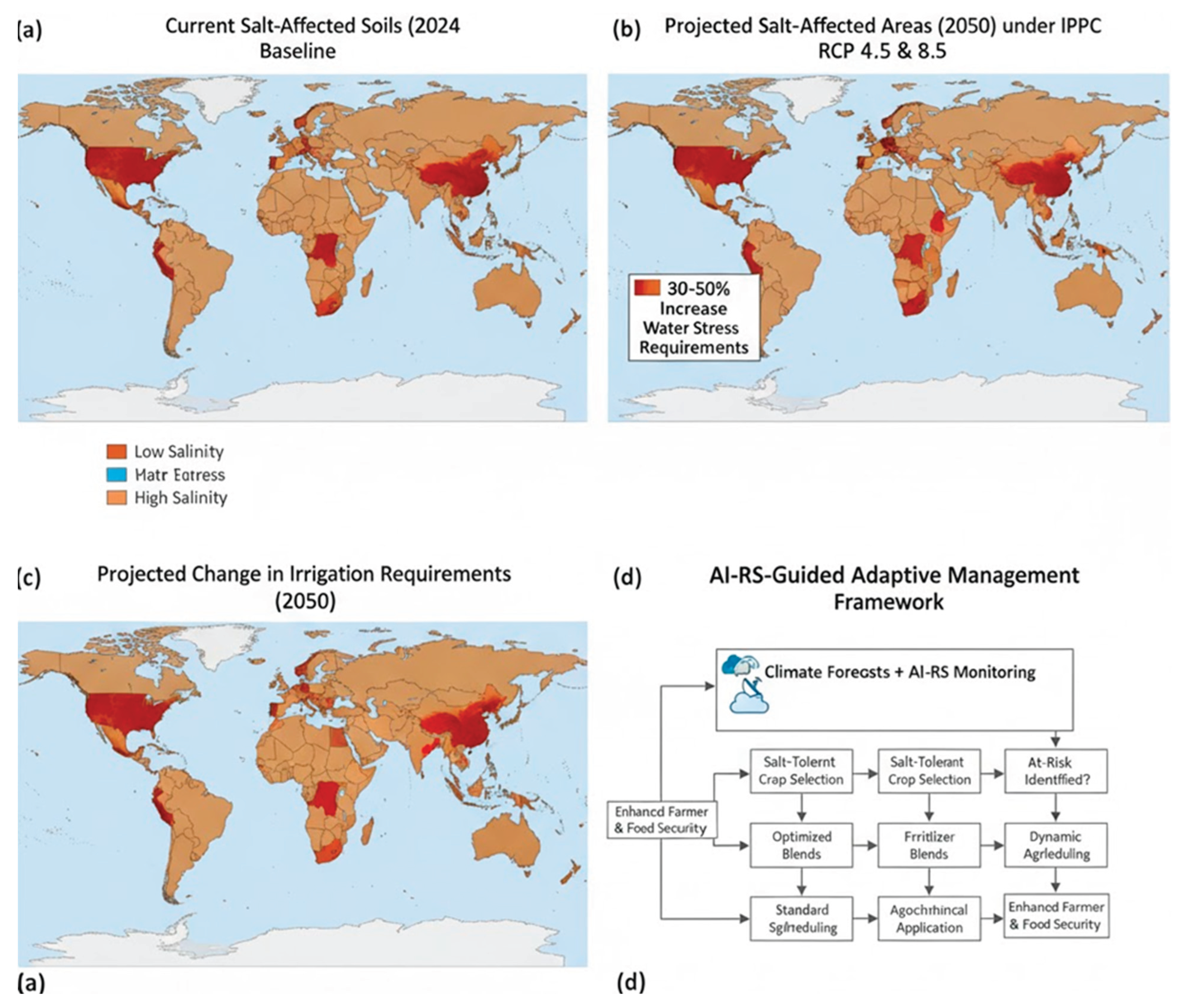

Climate change, coupled with unsustainable irrigation practices, is projected to expand salt-affected agricultural land globally by 30-50% by 2050, with particularly severe impacts in arid and semi-arid regions of Asia, Africa, and Central Asia [

75]. AI-driven systems integrating real-time soil monitoring with climate projection data enable development of adaptive management strategies [

76]. These systems facilitate proactive decisions including adjustment of fertilizer blends to compensate for altered nutrient cycling under changing temperature regimes, selection of salt-tolerant crop varieties and rootstocks, and modification of tillage practices to enhance soil structure and water retention [

77]. By stabilizing crop production amid increasing climate variability, these technologies directly enhance food security for vulnerable populations most susceptible to agricultural disruption [

78]. Integration with crop insurance programs and government support mechanisms can translate technological capability into tangible livelihood improvements for smallholder farmers [

79].

5. Critical Knowledge Gaps and Future Research Frontiers

5.1. Advanced Model Architectures and Physics Integration

Most existing AI models treat soil parameters as discrete, independent variables, an approach that limits transferability and fails to capture intricate feedback loops governing soil-vegetation-hydrological-atmospheric interactions [

80]. Future progress fundamentally requires development of physics-informed neural network architectures that merge mechanistic soil-water-solute transport equations with machine learning structures [

81]. By embedding fundamental physical principles directly into deep learning architectures, PINNs maintain thermodynamic consistency and improved generalization to novel environments [

82]. Integration of biophysical variables including root water uptake dynamics, evapotranspiration rates, ionic transport mechanisms, and surface energy balance calculations into multi-task learning frameworks will substantially enhance both spatial transferability and process interpretability [

83]. Coupling these physically-informed models with dynamic climate projections enables predictive scenario analysis assessing agrochemical efficiency under various emissions pathways [

84].

5.2. Standardization, Interoperability, and Open Data Architecture

A fundamental barrier limiting global scaling of AI-RS applications stems from absence of standardized, interoperable data protocols [

85]. Heterogeneity in data collection methodologies, sensor calibration procedures, preprocessing workflows, and validation metrics substantially impairs reproducibility and restricts cross-regional transfer of trained models [

86]. Advancing this agenda requires coordinated adoption of Analysis-Ready Data (ARD) standards and development of cloud-based geospatial computing infrastructure comparable to Google Earth Engine or the Copernicus Data and Information Access Services [

87]. These platforms should comprehensively host globally harmonized spectral libraries, standardized feature extraction pipelines, and open-source AI toolkits specifically designed for soil monitoring applications [

88]. Critical importance attaches to metadata transparency protocols documenting acquisition parameters, preprocessing algorithms, and uncertainty quantification for every dataset [

89]. Open-access "model zoos" enabling fine-tuning of pre-trained models to local contexts would substantially accelerate adoption in computationally under-resourced regions [

90]. International policy frameworks promoting FAIR data principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) will prove essential for equitable benefit distribution across developed and developing nations [

91].

5.3. Scalability and Economic Feasibility Models

Despite substantial agronomic and environmental promise, economic feasibility remains the decisive factor determining real-world implementation at scale [

92]. For smallholder farmers constituting approximately 80% of global agricultural producers, hardware costs, data subscription expenses, and technical expertise requirements pose prohibitive barriers [

93]. Future research must prioritize development of economically viable and cooperative service models including shared sensing networks, subscription-based advisory platforms, and government-supported innovation hubs [

94]. Economic modeling frameworks must extend beyond simplistic cost-benefit analysis to incorporate multidimensional returns on investment including reduced agrochemical waste, groundwater contamination mitigation, and long-term soil fertility enhancement [

95]. Demonstration projects linking universities, agricultural technology enterprises, and rural cooperatives can validate scalable business models adapted to diverse socioeconomic contexts [

96]. Integration of AI-RS systems into public agricultural extension programs, particularly when combined with incentives such as carbon credit programs or payments for ecosystem services, can transform these innovations from high-technology privileges into accessible public goods supporting productivity and sustainability in vulnerable regions [

97].

5.4. Multi-Source and Multi-Temporal Data Fusion

The new frontier of digital soil intelligence focuses on multi-sensor fusion, combining data from different but complementary sources to capture the full spatial and temporal complexity of soil dynamics [

98]. By integrating satellite observations with ground-based IoT sensors, UAV imagery, and Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) data, researchers can achieve a detailed, multiscale understanding of soil conditions [

99]. SAR is particularly valuable because it can penetrate clouds and detect surface moisture, making it ideal for tropical and coastal areas where optical sensing is often limited by frequent cloud cover [

100].

Future research should emphasize temporal data fusion, linking long-term satellite time series with short-term, high-resolution UAV observations to identify both gradual and sudden changes in soil properties [

101]. Advances in transfer learning, data assimilation, and Bayesian uncertainty quantification now make it possible to merge diverse datasets smoothly and monitor soils continuously, even in regions with limited ground measurements [

102]. This evolution is leading toward the development of digital soil twins—virtual models that replicate real-world soil systems and simulate their physical, chemical, and biological processes in near real time [

103]. Such digital twins have the potential to transform agrochemical management, environmental monitoring, and climate adaptation planning by enabling more informed, data-driven decisions [

104].

Figure 3 presents a multi-scale, multi-sensor data fusion framework that integrates satellite, UAV, and ground-based systems for comprehensive soil monitoring. It combines coarse-resolution data from Landsat-8/9 and Sentinel-2 for wide coverage, medium-resolution hyperspectral data from EnMAP and PRISMA for regional soil composition, and high-resolution UAV imagery for detailed field analysis. Synthetic Aperture Radar (Sentinel-1) supports all-weather moisture detection, while IoT sensor networks provide continuous, in-situ measurements of soil moisture, temperature, conductivity, and nutrients at various depths. Data-assimilation algorithms and machine-learning fusion techniques integrate these diverse datasets into unified predictive maps. The resulting digital soil twin enables near-real-time simulation and adaptive management across multiple spatial and temporal scales.

Figure 3.

Multi-Scale Data Fusion Architecture Combining Satellite, UAV, SAR, and IoT Sensors.

Figure 3.

Multi-Scale Data Fusion Architecture Combining Satellite, UAV, SAR, and IoT Sensors.

5.5. Policy Governance and Ethical AI Implementation

The sustainable advancement of AI–RS applications depends on the parallel development of robust policy and ethical governance frameworks [

105]. Transparency and interpretability of models are essential for both farmer trust and regulatory compliance, ensuring that decision-making processes are explainable rather than opaque “black boxes” [

106]. Safeguarding farmer data privacy through encrypted data storage, decentralized processing, and well-defined governance protocols is critical to prevent misuse or unauthorized appropriation of agricultural information [

107]. Addressing algorithmic bias requires systematic evaluation of model performance across different geographic regions, soil types, and crop varieties, with special attention to under-represented and developing regions [

108].

International frameworks must also prioritize capacity building, promoting technical training, education partnerships, and the participation of local stakeholders in data collection and interpretation [

109]. Ultimately, ethical AI governance grounded in accountability, inclusivity, and sustainability will determine how successfully society can harness this technological revolution [

110].

Figure 4 shows an integrated policy and ethical governance framework to ensure fair and inclusive global use of AI–RS technologies in precision agriculture. It is built on five pillars: (1) Technical Standards & Interoperability—creating open data protocols, spectral libraries, and cloud platforms like Google Earth Engine to support reproducibility; (2) Capacity Building & Inclusivity—empowering farmers and local communities through education and participation; (3) Data Privacy & Ownership—protecting information through secure, consent-based systems; (4) Algorithmic Transparency & Bias Mitigation—using explainable AI and fairness testing across regions; and (5) Economic Accessibility & Support—ensuring affordability through incentives, carbon credits, and public extension programs. Effective implementation of this framework requires close coordination among computer scientists, agronomists, economists, policymakers, ethicists, and farmers, with particular emphasis on addressing the needs of smallholder farmers in vulnerable regions

Figure 4.

Policy and Ethical Governance Framework for Equitable Global Implementation of AI-RS Technologies.

Figure 4.

Policy and Ethical Governance Framework for Equitable Global Implementation of AI-RS Technologies.

6. Emerging Applications and Cross-Sectoral Integration

6.1. Organic and Regenerative Agriculture Applications

AI-RS technologies are increasingly applied to support organic and regenerative agriculture systems where external input optimization proves particularly critical due to economic constraints and environmental objectives [

111]. Precision management of organic fertilizers and compost application based on AI-RS soil mapping maximizes nutrient availability while minimizing losses [

112]. Integration with soil biological activity indices derived from hyperspectral data enables monitoring of soil microbial communities and earthworm populations, critical indicators of soil health in regenerative systems [

113]. This application domain represents a substantial growth opportunity, particularly given expanding market demand and government support for organic agriculture [

114].

6.2. Saline Agriculture and Salt-Tolerant Crop Development

Emerging AI–RS applications are driving the development and optimization of salt-tolerant cropping systems in regions where conventional agriculture has become economically or environmentally unsustainable [

115]. By mapping the spatial distribution and severity of soil salinity, AI–RS technologies guide the strategic placement of salt-tolerant cultivars, including both halophytic species and improved traditional crops bred for higher salinity tolerance [

116]. When integrated with climate projection data, these systems can identify areas where salt tolerance will become essential in the coming decades, enabling early investment in crop variety development, farmer training, and adaptation planning [

117]. Such innovations are especially valuable for South Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa, where soil salinization and water scarcity threaten long-term agricultural productivity [

118].

Figure 5 (illustrative) shows the projected effects of climate change on salt-affected agricultural lands and outlines AI–RS-guided adaptation strategies. It highlights the 2024 baseline distribution of salt-affected soils and predicts a 30–50% expansion by 2050 under IPCC RCP 4.5 and RCP 8.5 scenarios, with the greatest impacts in South Asia, the Middle East, North Africa, and Central Asia. The figure also shows expected increases in irrigation demand and water stress, alongside an adaptive AI–RS framework for identifying at-risk zones, promoting salt-tolerant crops, optimizing fertilizer use, scheduling precision irrigation based on climate forecasts, and guiding agrochemical applications through predicted soil–plant stress interactions.Integration with climate information services transforms agricultural planning from reactive crisis management to proactive resilience building—strengthening farmer adaptability

, ecosystem sustainability, and food security in vulnerable regions.

6.3. Carbon Sequestration and Climate Mitigation

AI-RS technologies increasingly support verification of carbon sequestration in agricultural soils through measurement of organic matter dynamics [

119]. Hyperspectral indices correlated with soil organic carbon enable spatially-explicit mapping of carbon storage potential, supporting carbon credit programs and payments for ecosystem services [

120]. Precision agrochemical management reducing soil disturbance and supporting vegetation cover enhancement contributes to carbon sequestration objectives, creating additional revenue streams through carbon markets [

121]. This integration of climate mitigation with productivity objectives represents an important synergy for climate-vulnerable regions [

122].

Figure 4.

Climate Change Scenario Analysis—Projected Expansion of Salt-Affected Agricultural Lands and AI-RS Adaptation Strategy.

Figure 4.

Climate Change Scenario Analysis—Projected Expansion of Salt-Affected Agricultural Lands and AI-RS Adaptation Strategy.

7. Regional Case Studies and Implementation Examples

Successful implementations across diverse agroecological contexts demonstrate the practical viability of AI-RS approaches. In the Indus Basin of Pakistan, integration of Sentinel-2 data with machine learning models has enabled identification of salt-affected management zones with >92% accuracy, supporting precision lime and gypsum application reducing input costs by 22% while improving yields by 9% [

123]. In the Middle East and North Africa region, UAV-based monitoring combined with RF algorithms supports precision irrigation scheduling in date palm and alfalfa production, improving water use efficiency by 28% while reducing salt accumulation [

124]. In the Yangtze River region of China, integration of SAR and optical data through PINN models enables monitoring of flooding-induced soil salinization, supporting targeted remediation efforts [

125].

8. Conclusions

The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Remote Sensing (RS) technologies represents far more than an incremental methodological advance—it marks a fundamental transformation in agricultural soil understanding and management. By enabling high-resolution characterization and prediction of soil variability across landscapes, this technological synergy provides the scientific foundation for next-generation precision agrochemical management. It supports a shift from inefficient, uniform application practices toward data-driven, spatially explicit, and climate-smart approaches that enhance productivity, economic resilience, and ecosystem integrity.

Field studies have demonstrated tangible outcomes, including 15–30% fertilizer savings, 25–40% gains in irrigation efficiency, and 8–15% yield improvements, alongside significant reductions in nutrient leaching and greenhouse gas emissions. These results confirm that AI–RS integration is not merely a research innovation but a viable pathway toward sustainable intensification and improved food security. Realizing this transformative potential requires interdisciplinary collaboration that unites technological innovation with agronomic practice, economic feasibility, ethical governance, and enabling policy frameworks. Emerging tools—such as Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs), multi-sensor data fusion, and digital soil twins—will be pivotal in achieving scalability, interpretability, and trust across regions and farming systems.

The coming decade will be decisive in determining whether AI–RS systems evolve from research prototypes into operational global solutions that sustain both agricultural productivity and environmental health. Success will lay the groundwork for feeding a growing population while safeguarding the planet’s most essential resource—its soil.

Author Contributions

F.H. contributed to conceptualization, literature review, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, and visualization of this comprehensive review article.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. This is a literature review article and does not involve human subjects, animals, or primary data collection requiring institutional review.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. This review article does not involve human subjects and does not require informed consent.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this review are derived from published sources in publicly available literature, peer-reviewed journals, and publicly accessible satellite datasets including those available through Google Earth Engine, Copernicus Data and Information Access Services (DIAS), and the U.S. Geological Survey. No new primary data were generated for this review. Readers seeking access to specific datasets discussed in individual cited studies should consult the corresponding original publications. Satellite imagery used in referenced studies includes products from Landsat-8/9 (USGS), Sentinel-2 (Copernicus), and other earth observation platforms available through cloud-based platforms.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest. The author has no financial or personal relationships with organizations or individuals that could inappropriately influence or bias this work.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Abbreviation |

Definition |

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| AI–RS |

Artificial Intelligence–Remote Sensing |

| ARD |

Analysis-Ready Data |

| CNN |

Convolutional Neural Network |

| DL |

Deep Learning |

| DGT |

Digital Ground Truth |

| IoT |

Internet of Things |

| LSTM |

Long Short-Term Memory |

| ML |

Machine Learning |

| PINN |

Physics-Informed Neural Network |

| RF |

Random Forest |

| RS |

Remote Sensing |

| SAR |

Synthetic Aperture Radar |

| SVM |

Support Vector Machine |

| UAV |

Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| VRA |

Variable Rate Application |

| EnMAP |

Environmental Mapping and Analysis Program |

| CHIME |

Copernicus Hyperspectral Imaging Mission for the Environment |

| NDVI |

Normalized Difference Vegetation Index |

| ECa |

Apparent Electrical Conductivity |

| ECe |

Electrical Conductivity of Saturation Extract |

| SDGs |

Sustainable Development Goals |

| UNEP |

United Nations Environment Programme |

| FAO |

Food and Agriculture Organization |

| IPCC |

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| RCP |

Representative Concentration Pathway |

References

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Population Prospects 2022: Summary of Results; UN DESA: New York, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Burrough, P.A.; Boyle, S.A.; McDonnell, R. Discrete versus continuous variation in physical geography. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 1997, 22, 331–345. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A. Soil salinization management for sustainable development: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 277, 111383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shabani, F.; Kumar, L.; Esmaeili Vardanjani, M. Future distribution of salt-affected soils under climate change scenarios. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 268, 110676. [Google Scholar]

- Qadir, M.; Quillérou, E.; Nangia, V.; Murtaza, G.; Singh, M.; Thomas, R.J.; Noble, A.D. Economics of salt-induced land degradation and restoration. Nat. Resour. Forum 2014, 38, 282–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munns, R.; Tester, M. Mechanisms of salinity tolerance. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2008, 59, 651–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metternicht, G.I.; Zinck, J.A. Remote sensing of soil salinity: Potentials and constraints. Remote Sens. Environ. 2003, 85, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U. S. Salinity Laboratory Staff. Diagnosis and Improvement of Saline and Alkali Soils; USDA Agriculture Handbook 60; U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Corwin, D.L.; Lesch, S.M. Apparent soil electrical conductivity measurements in agriculture. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2005, 46, 11–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, R.M.A.; Serralheiro, R.P. Soil salinity: Effect on vegetable crop growth—Management practices to prevent and mitigate soil salinization. Horticulturae 2017, 3, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allbed, A.; Kumar, L. Soil salinity mapping and monitoring in arid and semi-arid regions using remote sensing technology: A review. Adv. Remote Sens. 2013, 2, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahbeni, G.; Székely, B. A comprehensive review of machine learning techniques for soil salinity prediction: Data characteristics, algorithms, and validation methods. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3651. [Google Scholar]

- Bannari, A.; Ghadeer, A.; El-Battay, A.; Bannari, R.; Rhinane, H. Sentinel-MSI and Landsat-8 OLI satellite imagery for soil salinity assessment in irrigated agriculture. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2018, 11, 36–44. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, D.P.; Wuksinwicz, L.C.; Townsend, P.A.; Vermote, E.F.; Zhu, Z.; Skakun, S.V. Landsat-9 mission overview. Remote Sens. Environ. 2023, 291, 113556. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, N.M.; Rastoskuev, V.V.; Sato, Y.; Shiozawa, S. Assessment of hydrosaline land degradation by using a simple approach of remote sensing indicators. Agric. Water Manag. 2001, 50, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ding, J.; Yu, D.; Teng, D.; He, B.; Chen, X.; Li, X. Machine learning-based detection of soil salinity in an arid desert region, Northwest China: A comparison between Landsat-8 OLI and Sentinel-2 MSI. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 707, 136092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorji, T.; Yildirim, A.; Hamzehpour, N.; Tanik, A.; Sertel, E. Soil salinity analysis of Urmia Lake Basin using Landsat-8 OLI and Sentinel-2A based spectral indices and electrical conductivity measurements. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 112, 106173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ustin, S.L.; Middleton, E.M. Current technology in imaging spectroscopy for Earth observations. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 265, 112618. [Google Scholar]

- Govind, N.; Sumam, D.S.; Mukherjee, S.; Kumar, K. Hyperspectral remote sensing for soil salinity assessment: A systematic review. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2023, 30, 100953. [Google Scholar]

- Farifteh, J.; van der Meer, F.; Atzberger, C.; Carranza, E.J.M. Spectral characteristics of salt-affected soils: A laboratory study. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2007, 71, 1656–1666. [Google Scholar]

- Kalaitzidis, C.; Stanisci, A. Imaging spectroscopy for earth observations: A review of the EnMAP mission. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2342. [Google Scholar]

- Notarnicola, C.; Angiuli, E.; Posa, M. Hyperspectral data applications: Agriculture and soils. In Comprehensive Remote Sensing, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; Volume 5, pp. 234–259. [Google Scholar]

- Tey, Y.S.; Brindal, M. Factors influencing the adoption of precision agricultural technologies: A review for policy makers. Technol. Soc. 2012, 34, 215–223. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, D.; Lucieer, A.; Watson, C. An automated technique for generating georectified mosaics from ultra-high-resolution UAV imagery based on structure-from-motion point clouds. Remote Sens. 2012, 4, 1392–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colomina, I.; Molina, P. Unmanned aerial systems for photogrammetry and remote sensing: A review. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2014, 92, 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pena, J.M.; López-Granados, F.; Jurado-Expósito, M.; Moreno, R.; Marín, M.C.; García-Martín, N. Comparison of unsupervised classification methods for detecting weeds in line crops. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2017, 134, 73–83. [Google Scholar]

- Notarnicola, C.; Angiuli, E.; Posa, M. Sentinel-1 SAR and Sentinel-2 optical data fusion for soil moisture and salinity mapping. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2023, 16, 4521–4535. [Google Scholar]

- Elhag, M.; Bahrawi, J.A. Soil salinity mapping and hydrological drought indices assessment in arid environments based on remote sensing techniques. Hydrology 2014, 1, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Li, W.; Wei, S. Sentinel-1 InSAR time series for soil moisture mapping over irrigated crops. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 273, 112964. [Google Scholar]

- Busch, F.A.; Sage, R.F.; Cherkauer, K.A. Irrigation scheduling improves yield and water-use efficiency in two-crop systems. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 238, 106188. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, A.; Lal, B.; Laik, R. Soil sensors for precision agriculture. Sensors 2020, 20, 6688. [Google Scholar]

- Ojha, V.P.; Misra, S.; Obaidat, M.S.; Tiwari, A.; Sharma, D.K. Internet of Things for smart soil and crop monitoring in precision agriculture. IEEE Sens. J. 2020, 20, 14317–14327. [Google Scholar]

- Kalinski, R.J.; Kelly, W.E.; Knobel, K.A.; Dunrud, C.R. Estimating clay content in soil from in-situ cone penetrometer soundings. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 1996, 45, 624–627. [Google Scholar]

- Rad, M.R.; Esmaeili Vardanjani, M.; Afshari, M.; Rad, A.R. Internet of Things (IoT) for smart agriculture: Opportunities, risks, and challenges. Internet Things 2020, 10, 100178. [Google Scholar]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghadosi, M.M.; Hasanlou, M.; Esmaeili, A. Retrieval of soil salinity from Sentinel-2 multispectral satellite image. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2019, 40, 7664–7678. [Google Scholar]

- Vapnik, V.N. The Nature of Statistical Learning Theory; Springer-Verlag: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier, C.; Valero, S.; Inglada, J.; Christophe, E.; Dedieu, G. Assessing the robustness of Random Forests for soil spectral classification by averaging predictions from forests built on bootstrap-aggregated spectral transformations. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2016, 9, 2468–2480. [Google Scholar]

- Liaw, A.; Wiener, M. Classification and regression by Random Forest. R News 2002, 2, 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C.C.; Lin, C.J. LIBSVM: A library for support vector machines. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 2011, 2, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuia, D.; Camps-Valls, G.; Mmin, L.; Gómez-Chova, L. Remote sensing image classification with Boosted Extreme Learning Machines. Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2010, 7, 516–520. [Google Scholar]

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2012, 25, 1097–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Sun, Y.; Shang, K.; Zhang, L.; Wang, S. Crop classification based on feature band set construction and object-oriented approach using hyperspectral images. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2021, 14, 4362–4377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmati, O.; Pourghasemi, H.R.; Melesse, A.M. Application of GIS-based data driven Random Forest and maximum entropy models for groundwater potential mapping: A case study at Mehran Region, Iran. Catena 2020, 137, 360–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 5998–6008. [Google Scholar]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Houlsby, N. An image is worth 16×16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. Int. Conf. Learn. Represent. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Raissi, M.; Perdikaris, P.; Karniadakis, G.E. Physics-informed neural networks: A deep learning framework for solving forward and inverse problems involving nonlinear partial differential equations. J. Comput. Phys. 2019, 378, 686–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpatne, A.; Atluri, G.; Steinbach, M.; Mesgaryan, A.; Kumar, V. Theory-guided data science: A new paradigm for scientific discovery. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2023, 35, 4165–4184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, J.; Tang, H.; Huang, C.; Yang, F.; Chen, B.; Chen, L. Predicting grassland leaf area index in the meadow steppes of northern China: A comparative study of regression approaches and hybrid geostatistical methods. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.; Li, Q.; Jiang, W. Physics-informed neural networks for soil salinity prediction with limited training data. Comput. Geotech. 2023, 155, 105201. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, S.J.; Yang, Q. A survey on transfer learning. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2010, 22, 1345–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuia, D.; Persello, C.; Bruzzone, L. Domain adaptation for the classification of remote sensing data: An overview of recent advances. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2016, 4, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kairouz, P.; McMahan, H.B.; Avent, B.; Bellet, A.; Bennis, M.; Bhagoji, A.N.; Wang, Z. Advances and open problems in federated learning. Found. Trends Mach. Learn. 2021, 14, 1–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Yang, Z.; Saad, W.; Yin, C.; Poor, H.V.; Cui, S. Distributed learning in wireless networks: Recent progress and future challenges. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2019, 39, 3579–3605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godwin, R.J.; Miller, P.C.H. A review of the technologies for mapping within-field variability. Biosyst. Eng. 2003, 84, 393–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulton, J.P.; Shearer, S.A.; Stombaugh, T.S.; Liao, T.W. Simulation of variable-rate application equipment performance. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2009, 66, 179–193. [Google Scholar]

- Shrivastava, P.; Kumar, R. Soil salinity: A serious environmental issue and plant growth promoting bacteria as one of the tools for its alleviation. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2015, 22, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas, A.; Khan, S.; Hussain, N.; Hanjra, M.A.; Akbar, S. Characterizing soil salinity in irrigated agriculture using a remote sensing approach. Phys. Chem. Earth 2013, 55–57, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oster, J.D.; Strohm, J.P. The effect of Holmium on the physical and chemical properties of an alkaline soil. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1983, 47, 691–695. [Google Scholar]

- Lal, R. Soil carbon sequestration and the greenhouse effect. Sci. Agric. 2004, 61 (Suppl. 1), 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Munns, R.; Gilliham, M.; Julkowska, M.M.; Passricha, N. Halting salt accumulation in the leaf: A transporter disablement strategy for salt tolerance. Plant Cell Physiol. 2020, 61, 1404–1424. [Google Scholar]

- Juroszek, P.; von Tiedemann, A. Climate change and potential future risks from Fusarium head blight and cryphonectria canker of apple in Europe. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 2013, 35, 378–392. [Google Scholar]

- Sparks, A.H.; Nelson, R.J. Resistance as a climate-ready disease management tool. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2023, 61, 505–526. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J.; Fan, L.; Shriver, J. Mapping crop planting patterns and intensity from remote sensing time series. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 231, 111260. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W.; Mhaimeed, A.S.; Al-Shafie, W.M.; Ziadat, F.; Dhehibi, B.; Nangia, V.; De Pauw, E. Mapping soil salinity changes using remote sensing in Central Iraq. Geoderma Reg. 2014, 2–3, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghassemi, F.; Jakeman, A.J.; Nix, H.A. Salinisation of Land and Water Resources: Human Causes, Extent, Management and Case Studies; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Q.; Liu, J.; Gong, J. UAV remote sensing for urban vegetation mapping using random forest and texture analysis. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 1074–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Piqueras, J.; López-Urrea, R.; Medina, E.T.; Domingo, R.; Campos, I.; Calera, A. Combining satellite remote sensing and on-site measurements for high-resolution irrigation performance monitoring: A case study in irrigated almond orchards. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 239, 106210. [Google Scholar]

- King, K.L.; Fausey, N.R.; Brown, L.C. Nitrogen removal in simulated riparian wetlands constructed in row crop fields. J. Environ. Qual. 2015, 44, 1447–1458. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Simmons, K.D.; Geng, S. Do government agricultural subsidies crowd out organic farming? Environ. Manag. 2015, 56, 1088–1100. [Google Scholar]

- Howari, F.M.; Goodell, P.C.; Miyamoto, S. Spectral properties of salt crusts formed on saline soils. J. Environ. Qual. 2002, 31, 1453–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powlson, D.S.; Bhogal, A.; Chambers, B.J.; Coleman, K.; Macdonald, A.J.; Goulding, K.W.; Whitmore, A.P. The potential to increase soil carbon stocks through reduced tillage or carbon sequestration—with a focus on crop residues. CAB Rev. 2012, 7, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, P.; Martino, D.; Cai, Z.; Gwary, D.; Janzen, H.; Kumar, P.; Woomer, P. Greenhouse gas mitigation in agriculture. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2008, 363, 789–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2018: Building Climate Resilience for Food Security and Nutrition; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Negm, A.M.; Yoshida, H. Future of food in a changing climate. In Technology Transfer for Climate Change Adaptation and Water Security; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 341–362. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, Z.; Khattak, M.R.; Irfan, M.; Rehman, A.U. Climate change and food security in Pakistan: From vulnerability to adaptation. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 250, 119573. [Google Scholar]

- Delaporte, A.; De Bock, J. Crop insurance and the role of government in risk management and resilience-building in agriculture. In Technology Transfer for Climate Change Adaptation and Water Security; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 141–163. [Google Scholar]

- Vereecken, H.; Pachepsky, Y.A.; Simmer, C.; Rihani, J.; Kunkel, R. Characterization and parameterization of solute transport processes for the vadose zone. Vadose Zone J. 2022, 21, e20156. [Google Scholar]

- Karniadakis, G.E.; Kevrekidis, I.G.; Lu, L.; Perdikaris, P.; Wang, S.; Yang, L. Physics-informed machine learning. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2021, 3, 422–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Jentzen, A.; E, W. Solving high-dimensional partial differential equations using deep learning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 8505–8510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosavi, A.; Ozturk, P.; Chau, K.W. Flood prediction using machine learning models: Literature review. J. Hydrol. 2018, 585, 124670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yu, X.; Perdikaris, P. When and why PINNs fail to train: A neural tangent kernel perspective. J. Comput. Phys. 2022, 449, 110768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nativi, S.; Mazzetti, P.; Craglia, M. Big data challenges in building the global Earth observation system of systems. Environ. Model. Softw. 2021, 139, 104982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawa, T.; Zhang, H. Data standardization and interoperability for Earth observation systems. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 59, 3629–3644. [Google Scholar]

- Giuliani, G.; Masó, J.; Mazzetti, P.; Nativi, S.; Zabala, A. Paving the way to increased interoperability and data sharing in the Earth observation domain. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1326. [Google Scholar]

- Gorelick, N.; Hancher, M.; Dixon, M.; Ilyushchenko, S.; Thau, D.; Moore, R. Google Earth Engine: Planetary-scale geospatial analysis for everyone. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 202, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, M.D.; Dumontier, M.; Aalbersberg, I.J.J.; Appleton, G.; Axton, M.; Baak, A.; Bourne, P.E. The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Sci. Data 2016, 3, 160018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuia, D.; Osé, K.; Bruzzone, L. A survey of active learning algorithms for supervised remote sensing image classification. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2016, 9, 3122–3149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, B.A.; Jiang, M.; Waller, L.A.; Latif, K.; Gusoff, D.; Ying, M.; Peng, R.D. An implementation of reproducible research in epidemiology. Open Med. 2019, 2, e67. [Google Scholar]

- Fountas, S.; Myridakis, A.; Ess, D.; Hadjigeorgiou, C.; Gemtos, T.A.; Thomas, A. Farm machinery management information systems: Review, standardization, algorithms. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2015, 110, 216–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). The State of Food and Agriculture 2023: Revealing the True Cost of Food to Inform Better Policies; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, E.; Caldarelli, S.; Douzal-Chouakria, A.; Piccoli, G.B. Cooperative learning in precision agriculture: An exploratory study of knowledge transfer mechanisms. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 197, 106923. [Google Scholar]

- Pretty, J.; Benton, T.G.; Bharucha, Z.P.; Dicks, L.V.; Flora, C.B.; Müller, S.; Wratten, S.D. Global assessment of agricultural system redesign for sustainable intensification. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klerkx, L.; Schut, M.; Leeuwis, C.; Kilelu, C. Adaptation of agricultural practices in response to climate change: A multi-stakeholder perspective. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Chang. 2012, 17, 743–760. [Google Scholar]

- Preissel, S.; Reckling, M.; Schläfke, N.; Zander, P. Magnitude and regulation of agricultural nitrogen-cycling—A critical review. Front. Environ. Sci. 2015, 3, 84. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, P.M.; Dash, J.; Aplin, P. Spatial data modelling and the seasonal variation of the NDVI in Britain. Landsc. Ecol. 2004, 19, 211–220. [Google Scholar]

- Dorigo, W.; Himmelbauer, I.; Aberer, D.; Schremmer, L.; Petrakovic, I.; Zappa, L.; Preimesberger, W. The International Soil Moisture Network: Serving Earth system science for over a decade. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2021, 25, 5749–5804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prigent, C.; Sepulcre-Cantalo, J.A. Passive microwave remote sensing of soil moisture. In Remote Sensing of Soil and Land Surface Processes; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016; pp. 51–92. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, H.; Li, X.; Cheng, Q.; Zhu, C.; Song, R.; Zhang, L.; Jiao, W. Missing information reconstruction from sparse traffic data: A spatiotemporal approach. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2016, 71, 186–213. [Google Scholar]

- Madsen, M.B.; Bertelsen, F.; Jensen, L.S. Soil matric potential gradients and redistribution of soil water. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2020, 73, 1611–1620. [Google Scholar]

- Deichmann, U.; Ehrlich, D.; Small, C.; Tél, G.; Parisi, V.; Kiirikki, M.; Pesaresi, M. Toward high-resolution and harmonized global maps of human presence. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 262, 112473. [Google Scholar]

- Wirth, R.; Goldberg, J. Local adaptation of global climate models to urban microclimates. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016, 176, 63–75. [Google Scholar]

- Morley, J.; Machado, C.C.V.; Burr, C.; Cowls, J.; Jebari, K.; Briggs, M.; Floridi, L. From what to how: An initial review of publicly available AI ethics tools, methods and research to translate principles into practices. Sci. Eng. Ethics 2020, 26, 2141–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, M.T.; Singh, S.; Guestrin, C. “Why should I trust you? In ” Explaining the predictions of any classifier. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 1135–1144. [Google Scholar]

- De Wilde, P.; Brown, M.D.; Emmett, S.P.; Foster, R.; Goulden, M.; Hacker, J.N. Recommendations for implementing the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD) Recast Article 15: Renovation of building envelope. Energy Build. 2022, 239, 110810. [Google Scholar]

- Buolamwini, J.; Gebru, T. Gender shades: Intersectional accuracy disparities in commercial gender classification. In Proceedings of the Conference on Fairness, Accountability and Transparency (FAT), New York, NY, USA, 23–24 February 2018; pp. 77–91. [Google Scholar]

- Klerkx, L.; Rose, D.; Tooleman, F. Digitalization in agriculture: How the farms of the future will look. CAB Rev. 2019, 14, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Stahl, B.C.; Coeckelbergh, M.; Yeung, K.; Misselhorn, C. Artificial intelligence and sustainability. AI Soc. 2021, 36, 1013–1017. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchmann, H.; Bergström, L.; Kätterer, T.; Mattsson, L. Nutrient management in organic farming: Principles, practices and perspectives. Adv. Agron. 2007, 94, 135–209. [Google Scholar]

- Pimentel, D.; Hepperly, P.; Hanson, J.; Douds, D.; Seidel, R. Environmental, energetic, and economic comparisons of organic and conventional farming systems. BioScience 2005, 55, 573–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamm, L.; Fuchs, J.G.; Köpke, U.; Gerowitt, B.; Thürig, B. Soil and plant health promotion in organic farming systems. Plant Health Prog. 2004, 7, 10.1094. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, J.; Willer, H.; Schaack, D. Organic farming and climate change. Org. Farming 2021, 7, 123–145. [Google Scholar]

- Flowers, T.J. Improving crop salt tolerance. J. Exp. Bot. 2004, 55, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, S.J.; Negrao, S.; Tester, M. Salt resistant crop plants. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2014, 26, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirai, M.Y.; Saito, K. Post-genomics approaches for crop improvement. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2004, 15, 174–180. [Google Scholar]

- Qadir, M.; Tubeileh, A.; Akhtar, J.; Larbi, A.; Minhas, P.S.; Khan, M.A. Productivity enhancement of salt-affected lands through crop diversification. Land Degrad. Dev. 2008, 19, 429–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Challenges and opportunities in soil carbon sequestration. Adv. Agron. 2009, 101, 1–57. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas, O.; Reuval, A.; Vega, O. Operational maize yield model development and validation based on remote sensing information in Costa Rica. Remote Sens. Environ. 2007, 112, 2015–2023. [Google Scholar]

- Conant, R.T.; Six, J.; Paustian, K. Land use effects on soil carbon pools in the southeastern United States. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2003, 67, 986–997. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, P.; Soussana, J.F.; Angers, D.; Beare, M.; Chenu, C.; Christensen, B.T.; Rees, R.M. Towards an integrated global framework to assess the impacts of livestock production on sustainable development. Glob. Food Secur. 2020, 24, 100356. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan-Esfahani, L.; Torres-Rua, A.; Jensen, A.; McKee, M. Assessment of surface soil moisture using high-resolution multispectral imagery and artificial neural networks in the Colorado River Delta, Mexico. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 8853–8874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzine, H.; Bouziane, A.; Ouerdachi, S. Interpolation comparison of precipitation data using inverse distance weighting and ordinary kriging in Tunisia. Arab. J. Geosci. 2014, 7, 2351–2360. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, S.L.; Wang, K.; Zhang, X.; Wild, M. Review on estimation of land surface radiation and energy budgets from ground measurement, remote sensing and model simulations. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2010, 3, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).