1. Introduction

Chronic disease is defined as a condition or disability necessitating ongoing care and treatment over at least six months, and is characterized by cycles of recovery and relapse [

1]. Chronic kidney disease, which represents a significant childhood disorder, is marked by an irreversible decline in kidney function. In Korea, the prevalence of chronic kidney disease is 3.7 cases per 1 million children, with 2.6 cases per 1 million children requiring dialysis. The primary etiologies include glomerulonephritis (41%), chronic pyelonephritis (25%), kidney dysplasia (9%), hereditary kidney disease (8%), secondary glomerular disease (6.9%), and other causes (10.0%) [

2].

Chronic kidney disease exerts multifaceted effects on pediatric patients. Beyond physical manifestations, such as changes in appearance or functional impairment, individuals frequently report depression, anxiety, diminished self-esteem, sadness, and poor self-concept [

3]. Interruption of regular activities, including frequent medical appointments, medication regimens, and dietary restrictions, leads them to perceive themselves as different from other children. These differences may hinder the formation of interpersonal relationships, fostering social isolation. Prolonged therapy can interfere with academic performance, raising concerns about educational attainment and future opportunities [

4]. Consequently, chronic kidney disease has substantial implications for the physical, psychological, and social domains of pediatric patients, which negatively affects their quality of life and hinders overall growth and development [

5].

Studies investigating the experiences of children with chronic diseases have found that hospitalization leads to separation from peers [

6]. Life was regarded as meaningful by children who could maintain activities similar to those of their friends and valued relationships with peers who understood their illness [

6]. Experiencing chronic illness may result in feelings of burden, as children are affected by both emotional distress and the financial strain placed upon their families, which can contribute to a sense of “withdrawal” from friends and school as they perceive themselves as “different” [

7]. An ethnographic investigation of adolescents with diabetes identified distinct psychological and emotional difficulties, including disengagement from school and social interaction [

8]. Children diagnosed with chronic epilepsy indicate that the psychological consequences of the illness outweigh the physical symptoms and describe their outlook on the future as “clouded by thick fog” [

9].

Children with chronic kidney disease often experience emotional confusion and social withdrawal soon after diagnosis, repeatedly facing periods of relapse and improvement over time, while making efforts to adjust to the disease [

10]. Youths living with chronic kidney disease need support in implementing coping strategies, which may include dietary regulation, self-management of health, engagement in physical activity, and adherence to regular medication, to facilitate positive adaptation to daily challenges. Adapting to a lifestyle that closely resembles normalcy is crucial for children with chronic kidney disease; nonetheless, there is a scarcity of qualitative research detailing their lived experiences, particularly regarding how they manage and surmount the protracted crisis linked to their condition. Comprehensive exploration of the experiences of children with chronic kidney disease can enhance our understanding, support the development of holistic nursing interventions, and contribute to the improvement of their overall quality of life. In light of this, we addressed the following research question: “What is the nature of the disease experiences of children with chronic kidney disease?”

3. Results

3.1. Theme Clusters

From the raw data, we identified 176 significant phrases or sentences. Phrases with related meanings were grouped, resulting in 65 reconstructed meanings. Following the exclusion of participant-specific experiences and the organization of common meanings, 19 themes were identified, which were integrated into seven theme clusters (

Table 2).

3.1.1. Theme Cluster 1: Appearance and Worsening of Kidney Disease Symptoms

Participants noticed the onset of kidney disease symptoms, which then progressed. Initial hospital visits occurred when symptoms such as edema, weight gain, hematuria, or proteinuria were detected, often by family members or close acquaintances during school urine tests, leading to a subsequent diagnosis. Since nephrotic syndrome often appears between age 5 and 5th grade, patients are commonly at a developmental stage where disease recognition is limited. Because the disease does not resolve quickly, patients are required to adhere to long-term medication regimens, dietary management, and activity restrictions. Furthermore, stress, colds, minor illnesses, and overexertion served as exacerbating factors.

“They detected blood in my urine during a school screening. It couldn’t be seen with the naked eye.” (Participants 10, 11)

“My abdomen and face became swollen, ... I assumed it was weight gain, but [following someone’s suggestion] I underwent tests at the hospital, and they found protein in my urine.” (Participant 2)

“I tend to bottle things up until I reach my breaking point, so I sometimes experience multiple sources of stress simultaneously. I may have difficulties with other students at school ... or my parents can upset me early in the morning. At times, they reprimand me quite sternly. Then my older sister, trouble at school, plus my evening part-time job with a challenging customer … when all of this happens while I’m already in a negative mood, it pushes me to my limits.” (Participant 12)

3.2. Theme Cluster 2: Restrictions in Daily Living

From the point of diagnosis, adolescents with chronic kidney disease must manage their health challenges while trying to maintain normal physical activities and daily routines at home and school. This management often involves adhering to specialized diets, limiting strenuous activity, and taking long-term medications. These treatment-related restrictions led participants to feel constrained in their everyday lives.

Theme 3: Difficulties Controlling Diet

“I can’t eat the same foods as my friends, and I have to regulate my intake. Because I can’t eat salty or spicy foods… I was unable to eat school meals, and I couldn’t have instant food,…. Back in high school, I used to join my friends for meals during breaks. Now, I can’t even do that.” (Participant 12)

“Food became a source of stress for me. When I dined with my friends, I had to eat something different, … I had to restrain myself [from eating inappropriate foods], which proved to be challenging.” (Participant 6)

“I really enjoyed playing soccer, and I was skilled at it. After starting high school, I would play soccer during lunchtime and dinnertime instead of eating, and that caused me significant stress.” (Participant 5)

3.3. Theme Cluster 3: Unstable Self-control

The participants expressed anger about their persistent symptoms, the experience of becoming ill, and being hospitalized when they ate the same foods as their peers. Some resented their parents for “giving them this disease” and experienced feelings of despair. Frequent recurrences resulted in anxiety and depression, fear that their condition would not improve, uncertainty regarding treatment duration, and apprehension about their future, all of which increased their fear of the illness. At times, they blamed themselves and felt anxious when unable to manage their daily routines. The mix of despair, fear, anxiety, and depression contributed to uncertainty about their ability to achieve self-control during the process of gaining independence.

“It’s like, ‘Why am I like this? …’ … I wonder, ‘Why is it just me who is unwell? Why does it have to be me?’ I kept experiencing this persistent despair, but… I went to the hospital and was fine for a week. … I start to think I might recover, but then I’m discharged, and I… return to how I was, and I think, ‘Will I ever live like other kids again?’” (Participant 7)

“I searched online, and it looked like the medicine doesn’t help [crying]. Recently, I’ve been starting to feel better when I take my medication, so I’m trying to take it routinely. I was really afraid. I didn’t speak to anyone, and sometimes when I feel down, I worry by myself since there’s no one I can consult, and even my mum and dad are not very knowledgeable.” (Participant 8)

“You always have to choose bland food. You always need to be cautious. You have to be mindful about your choices whenever you eat.” (Participant 2)

“Now, I no longer feel embarrassed, but at that time I did. Because all my friends were healthy, I felt unable to confide in anyone. I worry that my condition might worsen in the future, and I don’t want others to notice it, but whenever I return from the hospital, I experience a sense of depression. Why did I have to develop this disease [crying]?” (Participant 3)

3.4. Theme Cluster 4: Changes in Relationships with Friends

During a developmental period when peer acceptance is crucial, participants underwent notable changes in their friendships as a result of frequent outpatient appointments, hospitalizations, and the need to avoid excessive physical activity. These restrictions often led to withdrawal from friend groups. Participants reported feelings of isolation, particularly when excluded from conversations about shared events they missed due to medical appointments; this increased their sense of distance and, when they eventually rejoined their social circles, heightened feelings of being different and alienated.

“I was admitted to the hospital early in the school semester, but after I was discharged, [my friends] would joke around about things that happened when I wasn’t there. … I felt left out.” (Participant 2)

“Initially, I felt stuck in between. Spending time with the other kids made the situation uncomfortable for everyone. Since my friends are aware of my illness, when they order food—something they know I used to enjoy—but see I’m not eating, they can tell something is wrong. This mutual discomfort led me to stop joining them altogether. … At first, it was manageable, but as it persisted, our closeness diminished.” (Participant 7)

3.5. Theme Cluster 5: Sensitivity about a Decrease in Achievements Due to Disease

Due to imposed activity restrictions and awareness of physical limitations during treatment, participants became increasingly aware of the disease’s impact on their future prospects. This led to inner conflict about whether to abandon their aspirations or modify their career goals. Ongoing outpatient visits and frequent hospitalizations resulted in missed classes, declining academic performance, and a sense of academic stagnation. Participants also reported diminished motivation to achieve as they were unable to engage in the activities considered typical for their healthy peers. The heightened sensitivity to decreasing achievements was particularly impactful during adolescence, a formative stage for developing self-identity, making career decisions, and preparing for future employment.

“I aspire to become an air steward. Health management is a critical aspect for someone in this profession. It is essential to maintain physical fitness. The job requires standing for extended periods, serving customers, and lifting heavy objects, which places significant strain on my back. Overexertion sometimes leads to recurrence of my symptoms. I am concerned that these health issues could prevent me from achieving my aspirations. I have devoted myself to this goal, and the thought of not being able to pursue it is deeply unsettling. That possibility is what frightens me the most.” (Participant 3)

“When I was first diagnosed with anemia, I found myself unable to participate in many activities I enjoyed, and my capacity to study was limited. If I try to focus intently on something, I experience dizziness, so I spend most weekends resting at home. While studying, I am unable to remain seated for long periods, and I frequently need to adjust my posture, which becomes another source of stress.” (Participant 12)

“Since I have glomerulonephritis, I feel I am at a disadvantage from the outset. I cannot help but think that I might perform better if I did not have this disease, although I realize it might sound like I am making excuses.” (Participant 12)“I dislike the fact that I am unable to do what others can. I wish I could live as others do. For example, I simply want to eat instant noodles like other young people.” (Participant 3)

3.6. Theme Cluster 6: Efforts to Maintain a Normal Daily Life

Among the participants, all but one developed their disease at age five and received their diagnosis during elementary school. Initially, most participants did not take their diagnosis seriously; however, as they matured, recurrent episodes, worsening symptoms, and experiences—either direct or vicarious—increased their awareness of the condition’s seriousness. As they identified circumstances that exacerbated their symptoms, they proactively began to seek information about their illness. They made deliberate choices to limit certain behaviors, which altered how they perceived their situation. When their symptoms deteriorated after overexerting themselves or disregarding dietary restrictions, they acknowledged their limitations and accepted, “I can’t do this anymore.” Through a process of experimentation, participants determined the extent of self-control necessary and achieved a functional balance.

Over time, the majority of participants adjusted to the changes imposed by their illness and incorporated management strategies into their daily routines. They implemented dietary restrictions, committed to maintaining a low-salt diet, and improved their eating habits—such as by bringing packed lunches to school or avoiding eating out. To increase adherence to medication, some set reminders to ensure timely dosing. Social interactions were modified accordingly; they either decreased the number of meetings with friends or adapted these occasions as needed. These efforts enabled participants to better comply with their regimen and facilitated their adjustment to living with a chronic illness.

“I’ve experienced frequent relapses since 4th grade. Initially, they told me that such recurrence was typical for this disease and that it would improve with adulthood. However, when I relapsed again as a college student, I questioned, ‘Wasn’t it supposed to improve after becoming an adult? Why am I still having relapses?’ They then explained that repeated relapses diminish the likelihood of improvement.” (Participant 3)

“During the first six months, my life was almost entirely centered around managing my disease. After school, I would return home and was unable to eat freely, particularly having to avoid wheat-based foods. After about a year of following this, the continuous restriction became extremely stressful. When I chose to accompany my friends and eat as they did, I noticed a decline in my physical condition. Now, I believe I have managed to find a more balanced approach.” (Participant 7)

“I check the sodium content and select foods that are low in sodium. Sweet foods usually contain less sodium. I either eat [Satto-bap], or opt for sweet chocolate snacks, as they also have minimal salt.” (Participant 4)

“I avoided instant foods and brought a packed lunch to school. For both lunch and dinner, I made a conscious effort to have my mum prepare meals for me.” (Participant 8)

3.7. Theme Cluster 7: Psychological, Physical, and Social Strengthening

As participants reduced their social activities, they spent more time reflecting and gained a deeper appreciation of their health. They became increasingly attentive to their physical well-being and started contemplating their personal lives and future. Coping with illness fostered gratitude for their parents’ support and motivated them to reciprocate During physical education classes, while remaining in the classroom, they engaged with peers who differed from themselves and developed a better understanding of others. This experience helped them become more empathetic and accepting, even when their views diverged from those of their friends. Their frequent hospital experiences enhanced their social skills and fostered independence. Consequently, by managing their disease over time, participants demonstrated substantial psychological development. They assumed greater responsibility in their disease management. Recognizing the value of health and the role of self-management in preventing recurrence, many proactively sought information about their illness. Medication adherence became an established aspect of daily life, and they monitored side effects independently. Sustained dietary management led to modified eating behaviors, and they actively rejected harmful behaviors like alcohol and tobacco consumption. Instead of viewing their condition with negativity, participants transformed it into motivation: Their illness inspired them to study more diligently and adopt lifestyles aligned with their circumstances.

“I feel that this experience offered me a chance to become more mature. I caused significant emotional and financial difficulties for my parents. Initially, when I experienced a relapse, my immune system became very weak, necessitating a two-person room. It was extremely costly, and since we did not have insurance, financial challenges arose. My parents expressed concerns such as, ‘How can your kidneys already be impaired at your age? What if you need a transplant in the future?’ These situations made me realize that I needed to become a better son. If I had not been ill, I likely would not have reflected on these issues.” (Participant 9)

“I pay greater attention to my health now because I value being physically active. In middle school I played baseball, and in high school, I participated in soccer. I frequently sustained injuries, including ligament tears and swelling, but I now try to protect my body more. Since focusing on taking care of myself, I avoid being overly aggressive when playing sports. I believe I have become more even-tempered now.” (Participant 5)

“I strive to avoid having specific expectations about outcomes, and I do not dwell on negative thoughts, choosing instead to live in the present with the belief that things will ultimately resolve.” (Participant 10)

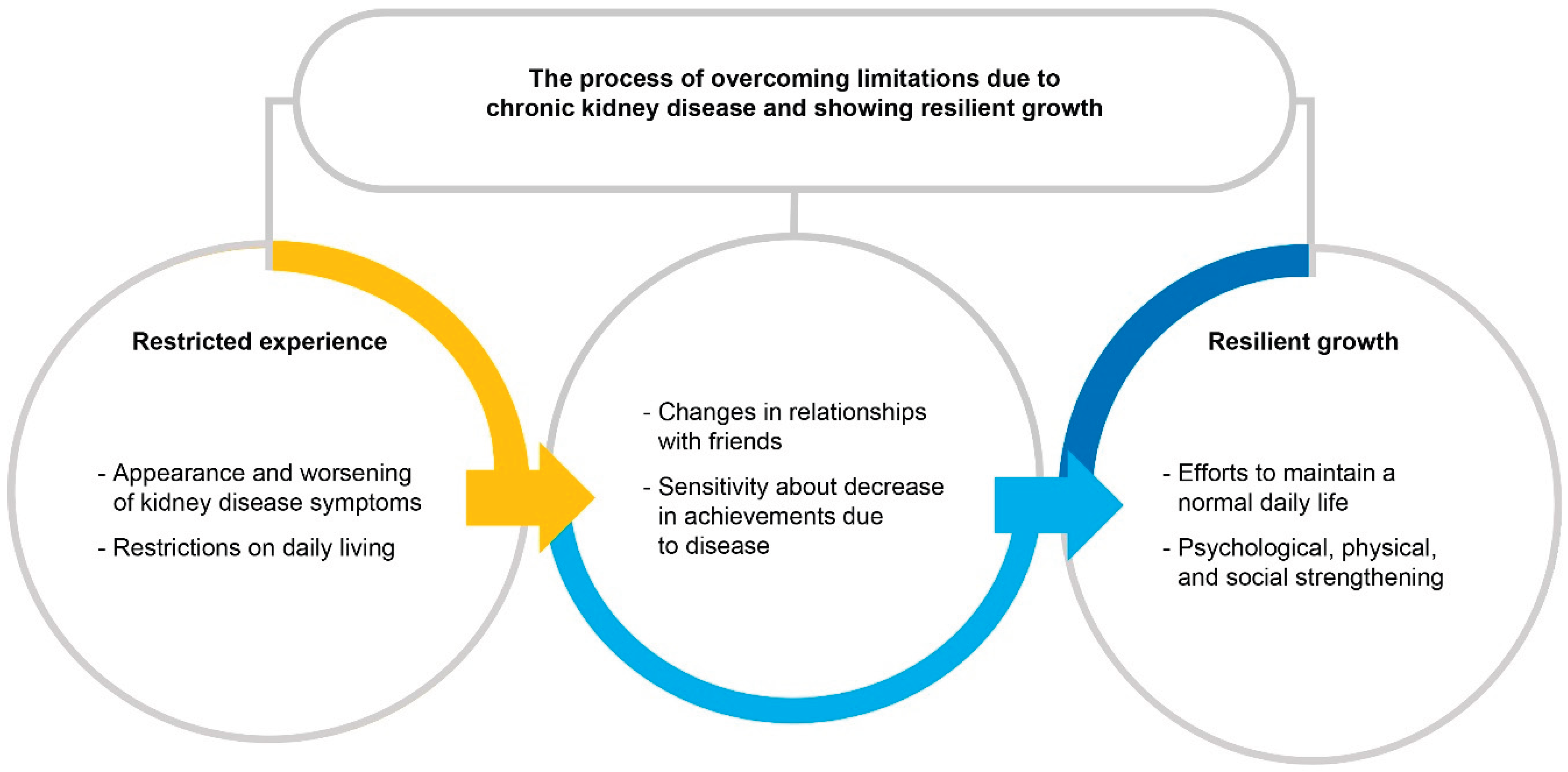

3.8. General Structure of the Disease Experiences of Children with Chronic Kidney Disease

This study identified the essential structure underlying the disease experiences of children with chronic kidney disease. In contrast to their healthy peers, these children encountered a variety of symptoms and daily life restrictions. Participants exhibited unstable self-regulation, with feelings of frustration, fear, tension, depression, and social isolation resulting from their illness. Their illness affected their career aspirations, created obstacles to their education, and contributed to reduced motivation for achievement during treatment.

Over time, however, these children began to transcend the limitations imposed by their condition. As they came to terms with their circumstances and adopted practical adjustments, they became more receptive to treatment regimens and made conscious efforts to lead a typical daily life. These adjustments facilitated internal development, expanding their self-awareness and empathic understanding toward others. The children also achieved physical strengthening through adopting healthier habits and developed social resilience by preparing for future opportunities that fit their specific context. The core of the disease experience for children with chronic kidney disease is maintaining a healthy day-to-day life amid illness, and is characterized as a “process of elastic growth through overcoming the limitations caused by chronic kidney disease” (

Figure 1).

4. Discussion

This phenomenological study investigated the lived experiences of children diagnosed with chronic kidney disease. Through analysis of their narratives, we identified seven thematic clusters and ascertained that the core of their experience was characterized as “overcoming limitations due to chronic kidney disease and showing resilient growth.”

“Restrictions in daily life” stemming from “the appearance and worsening of kidney disease symptoms” led participants to feel incapable of managing their lives. They reported experiencing “unstable self-control,” as well as emotions such as despair, depression, tension, and fear during a developmental stage when independence and autonomy are typically established. Our results indicate that restrictions imposed by the disease in everyday activities contributed to this instability in self-control. These findings align with previous research showing that the stress associated with daily living can have a more profound impact on children with chronic illness than the physiological symptoms of the disease itself [

13,

14]. Adolescents with chronic kidney disease need targeted education about permissible physical activities during treatment and the specific parameters of required dietary restrictions.

During a developmental period when peer relationships gain heightened importance, participants described experiencing “changes in their relationships with friends” due to frequent outpatient appointments, hospitalizations, and the necessity to avoid strenuous activities. Adolescence is a stage characterized by the development of meaningful friendships, which are foundational to personality formation and social adjustment. Peer groups provide essential stability and support, and strong friendships have been shown to predict future interpersonal success and adaptation in adult life. Evidence suggests that adolescents with chronic kidney disease are more likely to experience social withdrawal or interpersonal conflict, underscoring the necessity of addressing psychological challenges in this population [

15,

16].

In this study, the theme cluster “sensitivity to decline in achievements due to disease” revealed that frequent hospitalizations and outpatient visits associated with recurrences of kidney disease symptoms adversely affected academic performance and generated anxiety regarding participants’ prospective career trajectories. This observation is consistent with the findings of Lee [

17], who reported that repeated medical visits and hospitalizations impeded classroom adaptation, diminished academic achievement, and adversely influenced career planning. Targeted mentoring programs are warranted to mitigate these negative impacts and to support patients in exploring suitable career options.

When faced with their disease, the participants in our study demonstrated recovery and resilient growth through their “efforts to maintain a normal daily life” and through “psychological, physical, and social strengthening.” Participants became aware of their disease after experiencing recurrent or worsening symptoms, prompting them to re-evaluate their circumstances, seek additional information, and define personal limits. They worked to adhere to treatment recommendations while striving to maintain normalcy, engaging in activities suited to their health status, making compromises, adopting healthier dietary practices, and ensuring timely medication intake. These observations underscore the need for accurate and detailed information to empower adolescents with chronic kidney disease to effectively manage their health. Furthermore, both social and policy-level interventions are needed to enforce the availability of comprehensive nutritional information for school meals, restaurant options, and processed foods. Rather than being discouraged by lifestyle limitations when compared to their healthy peers, participants reframed these challenges as opportunities. They adapted to their situations, reorganized their routines, and progressed through critical developmental milestones while adhering to treatment protocols. The participants adopted coping strategies and demonstrated resilience by adhering to physical, psychological, and social supports, thus showing positive adaptation to their illness. The findings align with prior research showing that children with chronic conditions who understand and regulate their disease, and derive meaning and fulfillment from life, do not experience adverse psychosocial outcomes but instead develop a strong self-concept and high life satisfaction [

18,

19].

Although the participants in our study encountered challenges due to the restrictions imposed by their condition, they independently managed these obstacles, allowing them to progress successfully through adolescent developmental milestones. Adolescence represents a pivotal period for establishing health-related lifestyle habits, particularly concerning chronic diseases [

20]. Participants in this study cultivated positive behaviors by maintaining healthy routines during their prolonged illness. Additionally, it was evident that adolescents with chronic kidney disease developed a sense of identity through proactive disease management and demonstrated resilience in overcoming limitations in their daily activities. Nevertheless, an important limitation is that our positive results may partially reflect the self-motivated attitudes of participants who chose to participate. Despite this, our study provides valuable insights into the experiences of children with chronic kidney disease, expanding knowledge useful for supporting adolescents and their families and improving the quality of nursing care provided.