Submitted:

05 April 2023

Posted:

06 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

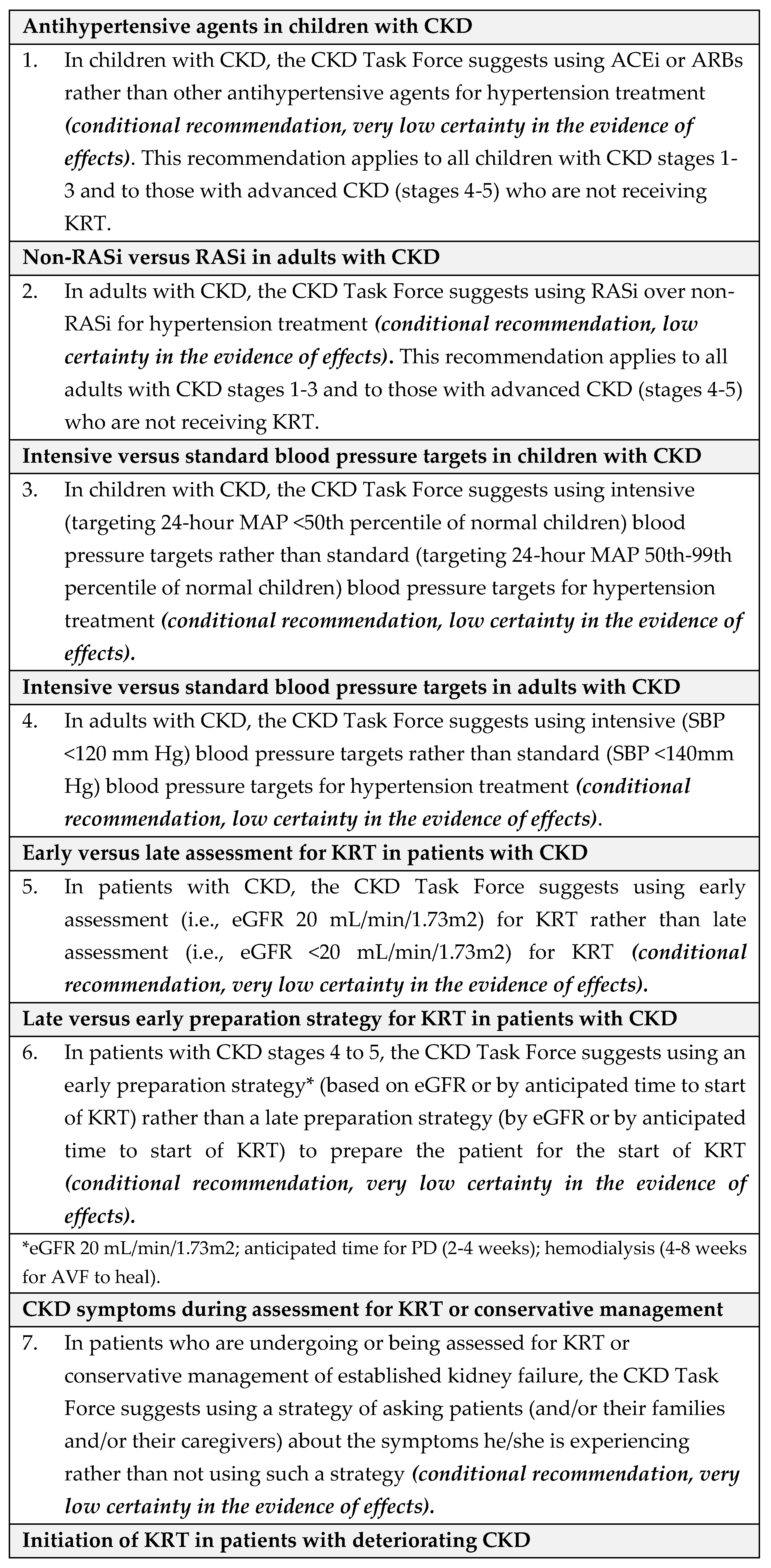

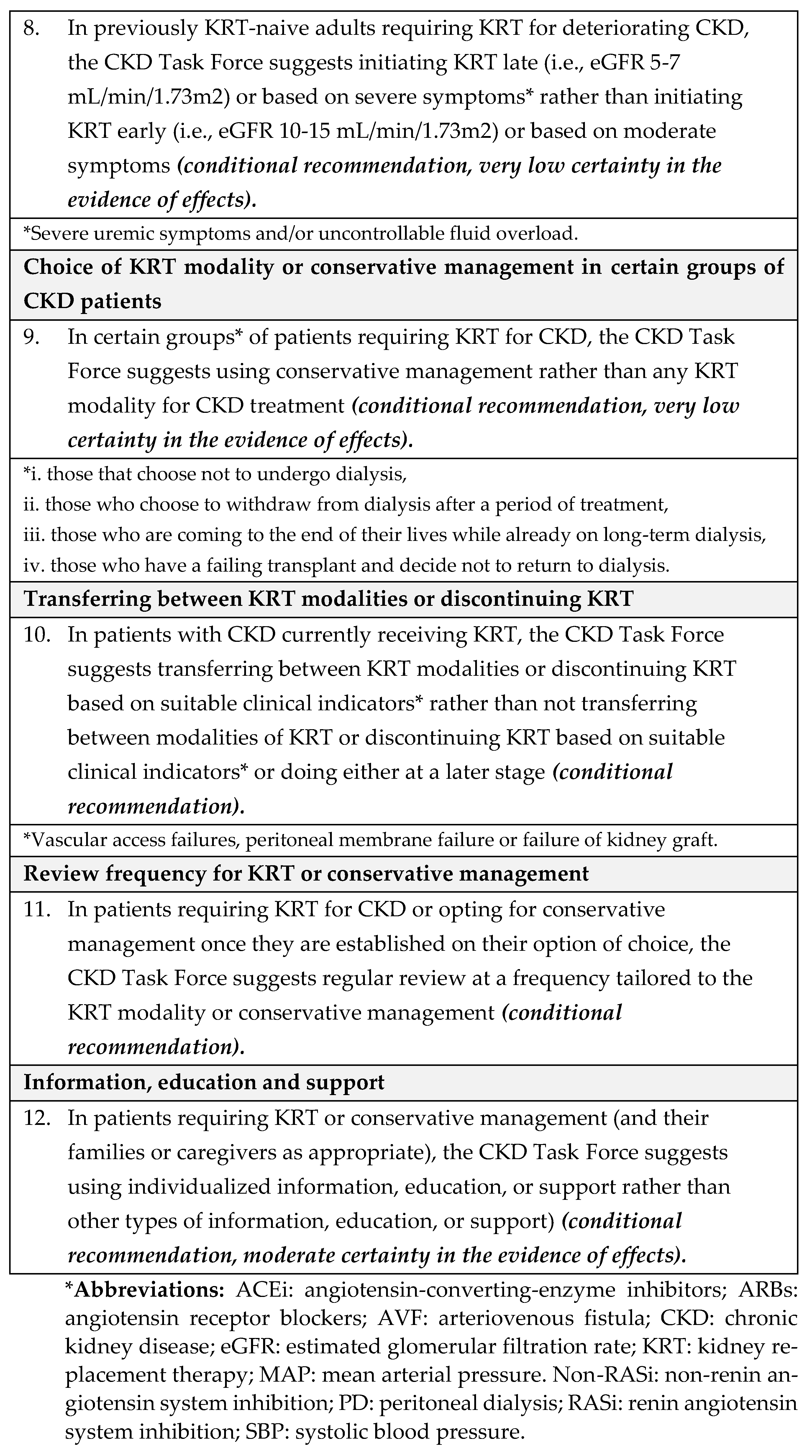

1. Summary of recommendations

1.1. Background

1.2. Methods

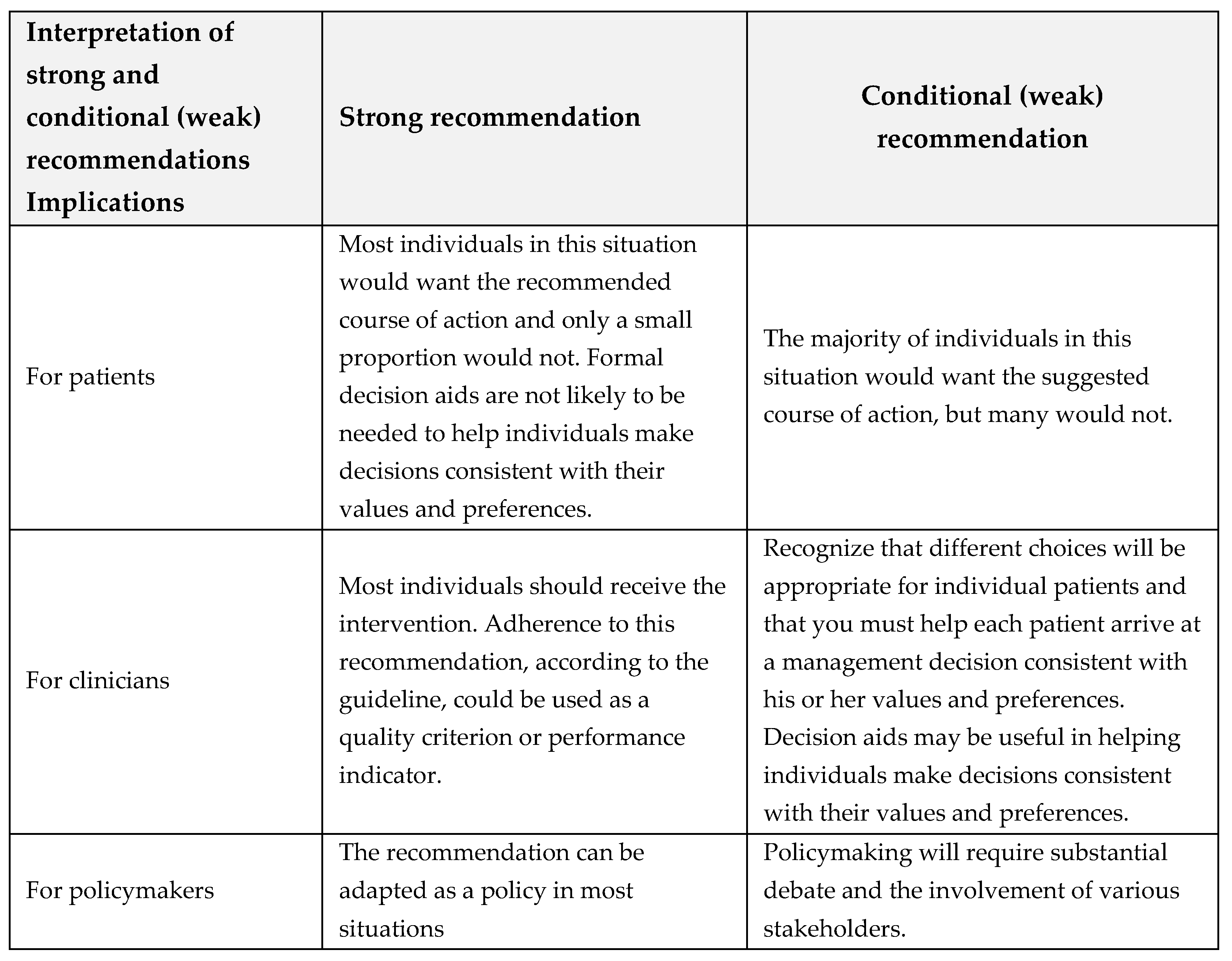

1.3. Interpretation of strong and conditional (weak) recommendations

2. Introduction

2.1. The aim of this guideline

2.2. Description of the health problem(s)

2.3. Epidemiology

2.4. Description of the target users

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Organization, Panel Composition, Planning and Coordination

3.2. Guideline Funding and Management of Conflicts of Interest

3.3. Selection of questions and outcomes of interest

3.4. Evidence Review and Development of Recommendations

3.5. Development of recommendations

3.6. Document review

3.7. Peer review and Approval

3.8. How to use this guideline

3.9. Guideline Registration

3.10. Guideline Reporting Checklists

4. Results

4.1. Recommendations

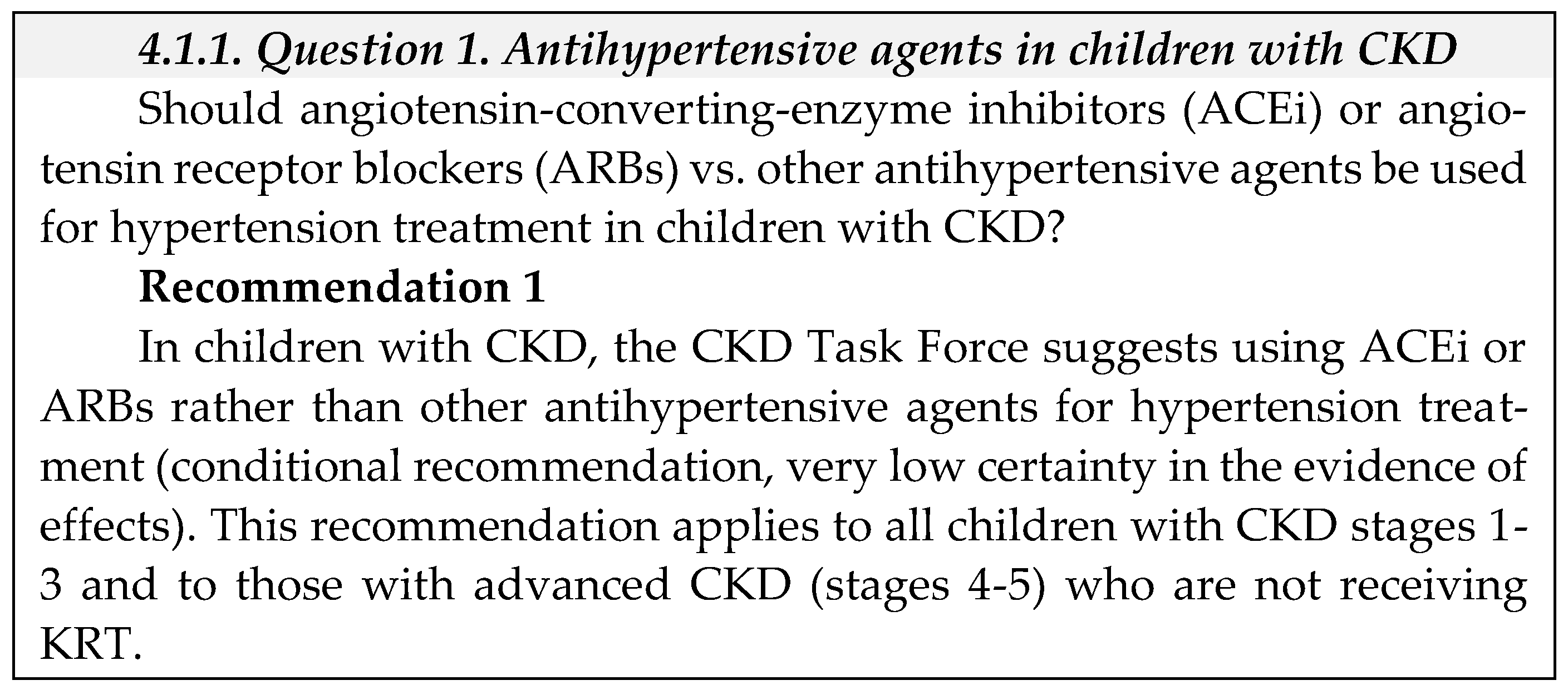

- Equity: We did not identify direct evidence to address equity for this question. The CKD Task Force concluded that given Saudi Arabia’s comprehensive health coverage, there would probably be no disadvantages associated with the use of antihypertensive treatment in children with CKD on equity from implementing the recommendation.

- Acceptability: We did not identify direct evidence to address acceptability for this question. The CKD Task Force used their collective experience with antihypertensive therapy to judge that this pharmacological therapy was acceptable to stakeholders in Saudi Arabia, such as providers and decision-makers.

- Feasibility: We did not identify direct evidence to address feasibility for this question. The CKD Task Force judged that there was no reason to suspect differences in feasibility regarding the availability of antihypertensive treatments in Saudi Arabia.

- Implementation: The 2021 KDIGO guideline [8] reported that implementing ABPM for monitoring the treatment of hypertension is challenging [27]. For instance, blood pressure monitors are not always available when needed; they require time from a parent or other adult to return the monitor to the clinic; they are expensive; and in certain situations, there is a low probability of finding elevated blood pressure using ABPM, such as children with clinic blood pressure at <25th percentile.

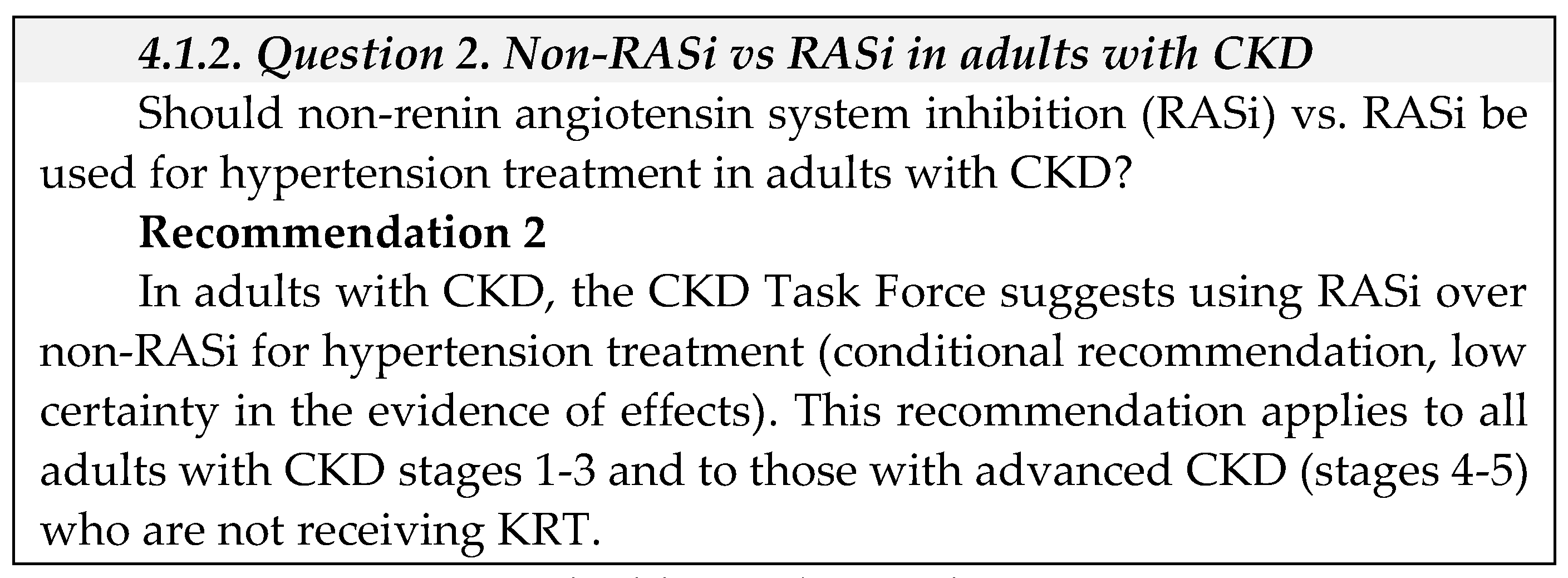

- Equity: We did not identify direct evidence to address equity for this question. The CKD Task Force concluded that in view of Saudi Arabia’s comprehensive health coverage, there would probably be no disadvantages associated with the use of antihypertensive treatment in adults with CKD on equity from implementing the recommendation.

- Acceptability We did not identify direct evidence to address acceptability for this question. The CKD Task Force used their collective experience with antihypertensive therapy in Saudi Arabia to judge that this pharmacological therapy was acceptable to stakeholders in Saudi Arabia, such as providers and decision-makers.

- Feasibility: We did not identify direct evidence to address feasibility for this question.

- Implementation: We did not identify direct evidence to address implementation for this question.

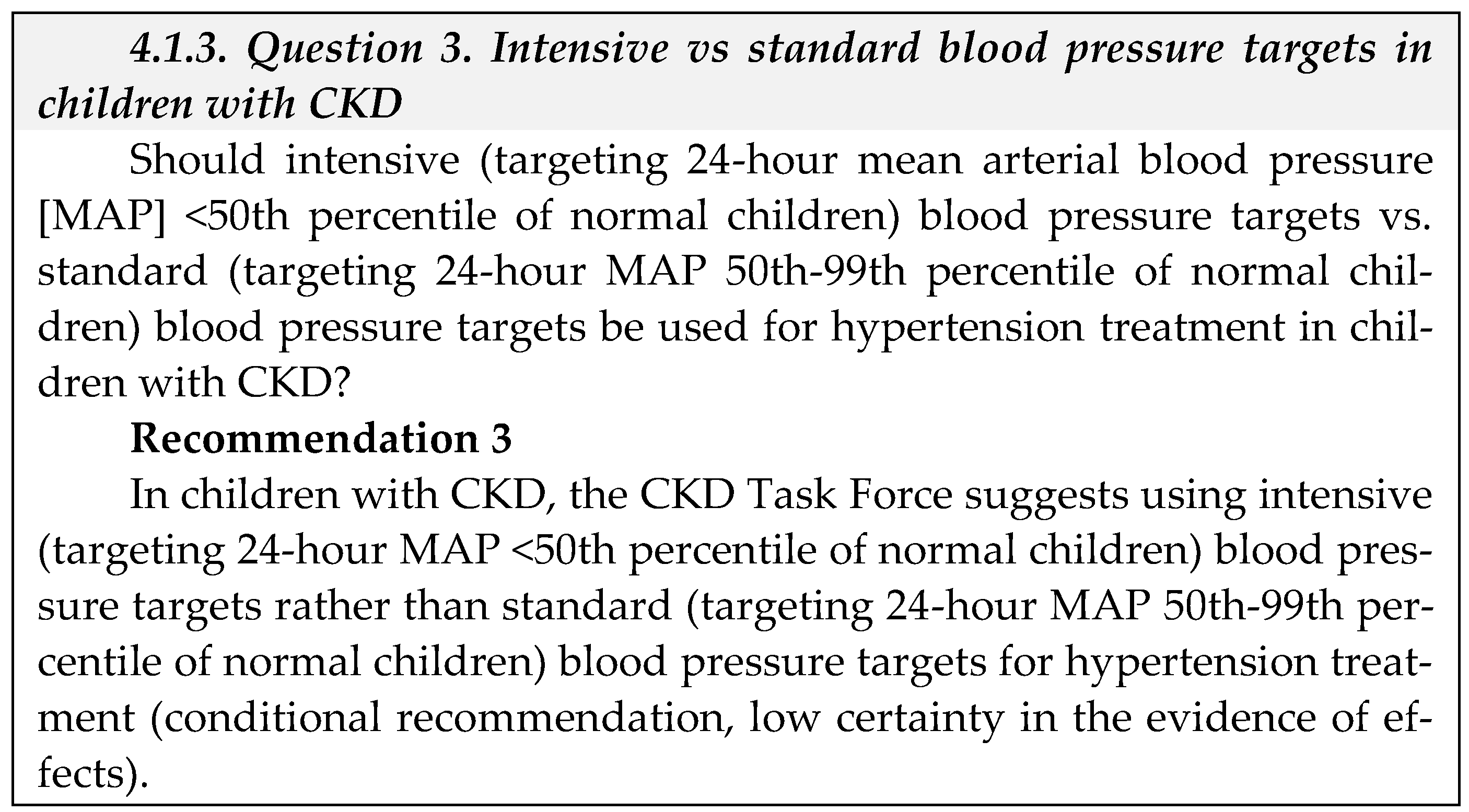

- Equity: We did not identify direct evidence to address equity for this question. The CKD Task Force concluded that given Saudi Arabia’s comprehensive health coverage, there would probably be no disadvantages associated with the use of antihypertensive treatment in children with CKD on equity from implementing the recommendation.

- Acceptability: We did not identify direct evidence to address acceptability for this question. The ESCAPE trial suggests that lower blood pressure targets are usually acceptable to patients and health care providers [36]. The CKD Task Force used their collective experience with antihypertensive therapy in Saudi Arabia to judge that this pharmacological therapy was acceptable to stakeholders in Saudi Arabia, such as providers and decision-makers.

- Feasibility: We did not identify direct evidence to address feasibility for this question.

- Implementation: The 2021 KDIGO guideline [8] reported that implementing ABPM for monitoring the treatment of hypertension is challenging [27]. For instance, blood pressure monitors are not always available when needed; they require time from a parent or other adult to return the monitor to the clinic; they are expensive; and there are certain situations where there is a low probability of finding elevated blood pressure by ABPM such as children with clinic blood pressure at <25th percentile.

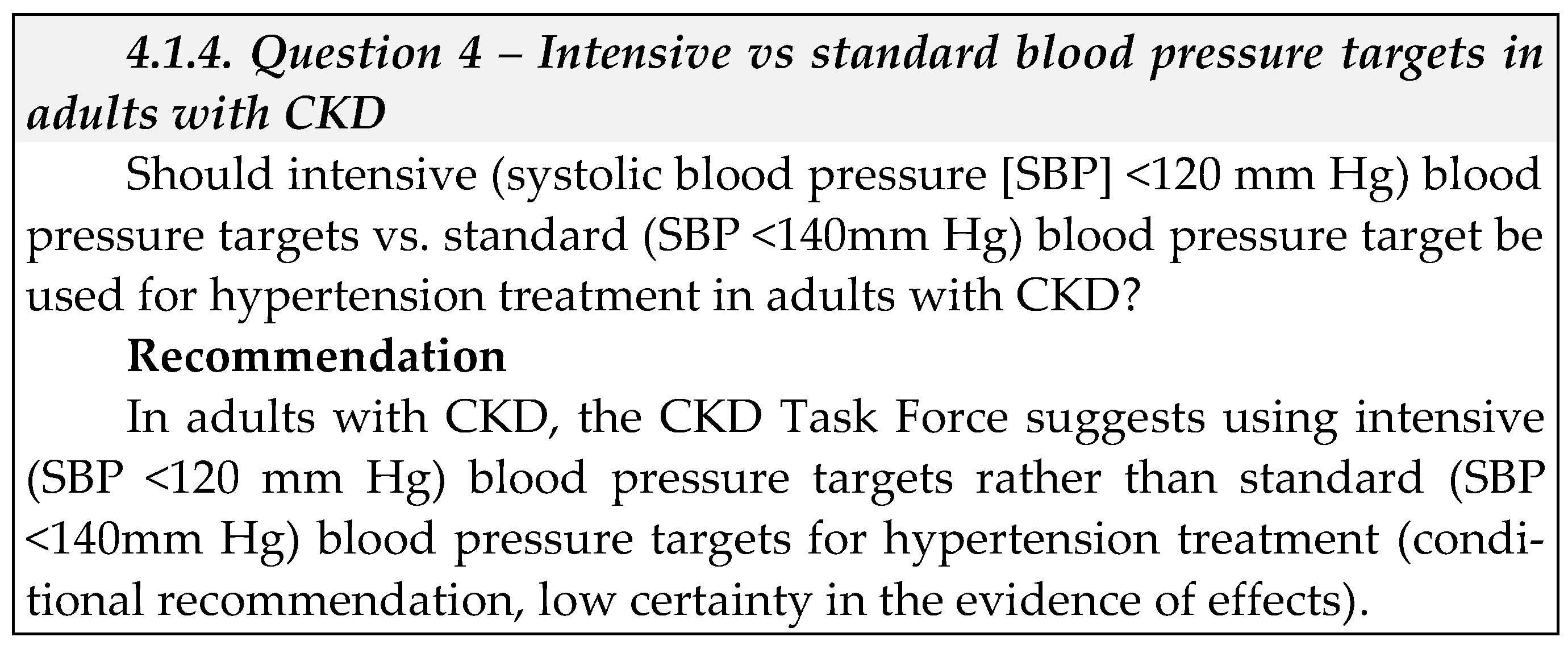

- Equity: We did not identify direct evidence to address equity for this question. The CKD Task Force concluded that given Saudi Arabia’s comprehensive health coverage, there would probably be no disadvantages associated with the use of antihypertensive treatment in children with CKD on equity from implementing the recommendation.

- Acceptability We did not identify direct evidence to address acceptability for this question. The CKD Task Force used their collective experience with antihypertensive therapy in Saudi Arabia to judge that this pharmacological therapy was acceptable to stakeholders in Saudi Arabia, such as providers and decision-makers.

- Feasibility: We did not identify direct evidence to address feasibility for this question.

- Implementation: We did not identify direct evidence to address implementation for this question.

- Cost of condition: CKD affects about 10 percent of the population worldwide, with over 2 million people worldwide reported to have ESKD [44]. In higher-income countries, treatment costs are enormous: a 2010 report from the United Kingdom (UK) National Health Service estimates its annual CKD spending at £1.45 billion, more than half of which was for KRT [45]. Australia has estimated it will spend over $12 billion on ESKD patients through 2020 [46]. At the same time, KRT remains entirely unaffordable to the majority of ESKD patients in low- and middle-income countries throughout the world, with over 1 million people dying annually from lack of treatment [47].

- Cost of interventions: According to a report estimating unit and annual cost for KTs in the UK, the initial assessment clinic costs include annual cost per patient £2,537 (Saudi Riyals [SAR] 13,137), and annual expenditure of £6,421,018 (SAR 33,238,174). A study conducted at a Saudi dialysis center assessed the health services cost of hemodialysis based on data gathered over 3.5 years [48]. The mean total cost per hemodialysis session came to US $297 (1,114 SAR), and the mean total cost of dialysis per patient per year was US $46,332 (173,784 SAR). Another study conducted in Saudi Arabia compared medical cost of transplantation following desensitization versus maintenance hemodialysis over a 4-year period [49]. The average annual cost of medical care per transplant patient was US $133,291, US $14,233, US $5,536, and US $4,402 in the first, second, third, and fourth year respectively. The average 4-year actual total cost per patient was significantly lower in the KT group compared to the hemodialysis group (US $210,779 vs US $317,186.3; p=0.017). A systematic review evaluating dialysis cost in low and middle-income countries found the annual cost per patient for hemodialysis to be lower compared to PD (ranging from international dollars (Int$) 3,424 to Int$ 42,785 with hemodialysis vs Int$ 7,974 to Int$ 47,971 with PD) [50]. The main cost drivers for hemodialysis were direct medical cost (especially drugs and consumables) and dialysis solutions and tubing for PD. A systematic review of cost-effectiveness of KRT modalities also reported that KT was the most cost-effective KRT modality, but that PD was more cost-effective than hemodialysis [43]. Most studies suggested that KT held a dominant position over hemodialysis and PD in terms of both lower costs and higher effectiveness. Five studies suggested that increased uptake of KT and PD by new ESKD patients would reduce costs and improve health outcomes or would be more cost-effective than current practice patterns.

- Equity: We did not identify direct evidence to address equity or feasibility for this question.

- Acceptability: We did not identify direct evidence to address acceptability for this question but found indirect evidence from a study evaluating the implementation of a multidisciplinary care (MDC) clinic for patients with advanced CKD [51]. The study suggested possible improvement in adherence to CKD intervention targets and good participants’ acceptability of the MDC program consisting of clinical outcomes assessment, self-care advice, and KRT options.

- Feasibility: We did not identify direct evidence to address feasibility for this question.

- Implementation: The CKD Task Force suggested using doubling serum creatinine as an indicator for early assessment of CKD, especially in the remote areas of Saudi Arabia, where hospital infrastructure and proper laboratory facilities may be limited, and the use of GFR may not be possible.

- Cost of interventions: According to a report estimating unit and annual cost for KT in the UK, the initial assessment clinic costs include annual cost per patient £2,537 (SAR 13,137), and annual expenditure of £6,421,018 (SAR 33,238,174). A study conducted at a Saudi dialysis center assessed the health services cost of hemodialysis based on data gathered over 3.5 years [48]. It found that the mean total cost per hemodialysis session came to US $297 (1,114 SAR), and the mean total cost of dialysis per patient per year was US $46,332 (173,784 SAR). Another study conducted in Saudi Arabia compared medical cost of transplantation following desensitization versus maintenance hemodialysis over a 4-year period [48]. The average annual cost of medical care per transplant patient was US $133,291, US $14,233, US $5,536, and US $4,402 in the first, second, third, and fourth year respectively. The average 4-year actual total cost per patient was significantly lower in the KT group compared to the hemodialysis group (US $210,779 vs US $317,186.3; p=0.017). A systematic review evaluating dialysis cost in low and middle-income countries found the annual cost per patient for hemodialysis to be lower compared to PD (ranging from international dollars (Int$) 3,424 to Int$ 42,785 with hemodialysis vs Int$ 7,974 to Int$ 47,971 with PD) [50]. It reported that the main cost drivers for hemodialysis were direct medical cost (especially drugs and consumables) and dialysis solutions and tubing for PD. A systematic review of cost-effectiveness of KRT modalities also reported that KT was the most cost-effective KRT modality but that PD was more cost-effective than hemodialysis [43]. Most studies suggested that KT held a dominant position over hemodialysis and PD in terms of both lower costs and higher effectiveness. Five studies suggested that increased uptake of KT and PD by new ESKD patients would reduce costs and improve health outcomes or would be more cost-effective than current practice patterns.

- Acceptability: We did not identify direct evidence to address acceptability for this question [51].

- Feasibility: We did not identify direct evidence to address feasibility for this question.

- Implementation: We did not identify direct evidence to address implementation for this question.

- The timing of creating percutaneous and laparoscopic PD access for different KRT options.

- The clinical and cost-effectiveness of initial hemodialysis versus initial peritoneal dialysis for people who start dialysis in an unplanned approach.

- The best timing for transplant listing for those on KRT considering transplantation.

- Equity: We did not identify direct evidence to address equity for this question.

- Acceptability: We did not identify direct evidence to address acceptability for this question. However, we found indirect evidence on acceptability from a study evaluating the implementation of a MDC clinic for patients with advanced CKD [49]. The study suggested possible improvement in adherence to CKD intervention targets and good participants’ acceptability of the MDC program consisting of clinical outcomes assessment, self-care advice, and KRT options.

- Feasibility: We did not identify direct evidence to address feasibility for this question.

- Implementation: We did not identify direct evidence to address implementation for this question.

- Equity: We did not identify direct evidence to address equity for this question.

- Acceptability: We did not identify direct evidence to address acceptability for this question.

- Feasibility: We did not identify direct evidence to address feasibility for this question.

- Implementation: We did not identify direct evidence to address implementation for this question.

- Cost of interventions: initial assessment clinic has an annual cost per patient of £2,537 (SAR 13,137), and an annual expenditure of £6,421,018 (SAR 33,238,174). The mean total cost per hemodialysis session was calculated as 297 US dollars (USD) (1,114 SAR), and the mean total cost of dialysis per patient per year was 46,332 USD (173,784 SAR) [48]. One study conducted in Saudi Arabia described that an average annual cost of medical care per patient after transplantation in the first, second, third, and fourth year was USD $133,291, USD $14,233, USD $5,536, and USD $4,402, respectively. The average 4-year actual total cost per patient was USD $210,779 and USD $317,186.3 in the kidney transplant group and the hemodialysis group; respectively (p=0.017) [49].

- In terms of cost-effectiveness, one study assessed the value for money and budget impact of offering hemodialysis as a first-line treatment, or the hemodialysis-first policy, and the PD first policy compared to a supportive care option in patients with ESKD in Indonesia [66]. The PD-first policy was found to be more cost-effective compared to the hemodialysis-first policy. Budget impact analysis provided evidence on the enormous financial burden for the country if the current practice, where hemodialysis dominates PD, continues for the next five years.

-

Costs:

- ○

-

Life years saved

- ▪

- Supportive care option: 0.21

- ▪

- PD first option: 5.93

- ▪

- Hemodialysis first option: 5.93

- ○

-

Quality-adjusted life years (QALY)

- ▪

- Supportive care option: 0.076

- ▪

- PD first option: 4.40

- ▪

- Hemodialysis first option: 4.34

- ○

-

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio

- ▪

- Supportive care: Not reported

- ▪

- PD first option: 193.2 million IDR

- ▪

- Hemodialysis first option: 2017.4 million IDR

- ○

-

Cost-effectiveness acceptability

- ▪

- At the threshold of willingness to pay 43 million IDR (1 GDP), supportive care was the best option. (probability = 1.00)

- ▪

- At willingness to pay >190million IDR, PD first was the most cost-effective option (probability >0.5)

- ▪

- Hemodialysis first was not the best cost-effective option at any level of willingness to pay.

- Equity: We did not identify direct evidence to address equity for this question.

- Acceptability: We did not identify direct evidence to address acceptability for this question. However, the included study provided information on the survival of patients who have chosen to forego dialysis and demonstrated that in patients aged >75 years with high extra-renal comorbidity, the survival advantage conferred by KRT over conservative management is likely to be small [65]. Our update search conducted in October 2021 identified a protocol for a pilot RCT aiming to explore the feasibility and acceptability of Conservative Kidney Management Options and Advance Care Planning Education—COPE, change in communication of preferences and differences in the intervention’s effects on knowledge and communication of preferences by race (Stallings et al., 2021).

- Feasibility: We did not identify direct evidence to address feasibility for this question.

- Implementation: We did not identify direct evidence to address implementation for this question.

- What is the clinical and cost-effectiveness of conservative management versus dialysis in frail, older people? [20].

- Can a CKD Frailty Index be used to inform patient decision-making? [68].

- What would constitute the index—could it be based on the Integrated Palliative Care Outcome Scale (IPOS)-Renal index? [68] And finally,

- Could a CKD Frailty Index be combined with traditional and novel biomarkers and clinical scoring systems (serial assessments of fluid status, nutritional status and/or body composition) to guide initiation of dialysis? [68]

- Cost of disease

- Cost of interventions

- Equity: We did not identify direct evidence to address equity for this question.

- Acceptability: We did not identify direct evidence to address acceptability for this question. Indirect evidence from one study provided information on the survival of patients who have chosen to forego dialysis. The study demonstrated that in patients aged >75 years with high extra-renal comorbidity, the survival advantage conferred by KRT over conservative management is likely to be small [65].

- Feasibility: We did not identify direct evidence to address feasibility for this question.

- Implementation: We did not identify direct evidence to address implementation for this question.

- Transplant: Practice for assessing transplant function can vary between centers but commonly involves eGFR measurement every 3 months and eGFRs being reviewed by the renal team on a 3-6 monthly basis. Children are usually assessed at least every 3 months. The general health of people with a stable KT is typically assessed at least once a year and includes the assessment of cardiovascular risk factors.

- Dialysis: In the absence of any evidence, it is difficult to make any specific recommendations about the ideal frequency of review in people on dialysis. Patients receiving in-center dialysis may be reviewed too frequently as it is logistically easy to do.

- Conservative management: Frequency of review in this patient group is highly dependent on the prognosis of the patient and stage of treatment. The frequency of review will increase as the person’s condition deteriorates, based on individual circumstances and preferences. Face-to-face review is likely to be particularly important for patients receiving conservative management to assess current functional status.

- Cost of interventions

-

Costs:

- ○

-

Life years saved

- ▪

- Supportive care option: 0.21

- ▪

- PD first option: 5.93

- ▪

- Hemodialysis first option: 5.93

- ○

-

Quality-adjusted life years

- ▪

- Supportive care option: 0.076

- ▪

- PD first option: 4.40

- ▪

- Hemodialysis first option: 4.34

- ○

-

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio

- ▪

- Supportive care: Not reported

- ▪

- PD first option: 193.2 million IDR

- ▪

- Hemodialysis first option: 2017.4 million IDR

- ○

-

Cost-effectiveness acceptability

- ▪

- At the threshold of willingness to pay 43 million IDR (1 GDP), supportive care was the best option (probability = 1.00)

- ▪

- At willingness to pay >190million IDR, PD first was the most cost-effective option (probability >0.5)

- ▪

- Hemodialysis first was not the best cost-effective option at any level of willingness to pay.

- Equity: We did not identify direct evidence to address equity for this question.

- Acceptability: We did not identify direct evidence to address acceptability for this question. Indirect evidence from one study provided information on the survival of patients who have chosen to forego dialysis. The study demonstrated that in patients aged >75 years with high extra-renal comorbidity, the survival advantage conferred by KRT over conservative management is likely to be small [65].

- Feasibility: We did not identify direct evidence to address feasibility for this question.

- Implementation: We did not identify direct evidence to address implementation for this question.

- What is the most clinical and cost-effective frequency of review for people on PD, hemodiafiltration, hemodialysis or conservative management? [20]

- Could a CKD Frailty Index be used to identify clinically important changes over time in individuals before dialysis and after initiation of dialysis? [68]

- Are the changes different with hemodialysis versus PD? [68]

- Is it possible to predict which patients improve and which get worse? [68]

- To what extent do uremic symptoms change after initiation of dialysis? [68]

-

Treatments including KRT, conservative management and dietary intervention:

- What they involve, for example, availability of assistance, time that treatment takes place, and number of sessions per day/week

- Potential benefits

- The benefits of adherence to treatment regimens and the potential consequences of non-adherence

- Potential adverse effects, their severity and how they may be managed

- The likely prognosis on dialysis, after transplant or with conservative management

- The transplant listing process (when appropriate)

- Switching the modality of KRT and the possible consequences (that is, the impact on the person's life or how this may affect future treatment or outcomes)

- Reviewing treatment decisions

- Stopping treatment and planning end of life care.

-

Information about how treatments may affect lifestyle:

- The person or caregiver's ability to carry out and adjust the treatment themselves

- The possible impact of dietary management and management of fluid allowance

- How treatment may fit in with daily activities such as work, school, hobbies, family commitments and travel for work or leisure

- How treatment may affect sexual function, fertility, and family planning

- Opportunities to maintain social interaction

- How treatment may affect body image

- How treatment may affect physical activity (for example, whether contact sports should be avoided after transplantation, whether swimming should be avoided with PD)

- Whether a person's home will need to be modified to accommodate treatment

- How much time and travel treatment or training will involve

- The availability of transport

- The flexibility of the treatment regimen

- Whether any additional support or services might be needed.

- Content of Information: Content of information should cover symptoms, prognosis, mode of access, benefits, and harms of different modalities of KRT and conservative management, services, adherence, how to approach living donors, acute situations, kidney function and CKD, Information around transitions between forms of KRT, and end-of-life care.

- Format of information provision: Patients reported the depth and timing of information, personalized information, delivery via classes and tours, and in multiple formats, and the target of education/information as important themes to be addressed. Decision making was also identified as an important topic for education.

- Stress/support: People noted that the availability of transport affected their ability to engage with KRT and was a significant psychological stressor during KRT. Psychological support was identified as one of the support systems.

- Barriers/problems: Barriers to home dialysis were lack of a care partner, lack of home space, and patient preference (El Shamy et al., 2021). Some of the participants encountered periods of limited funds. Some of the participants experienced the effects of the hidden costs of dialysis, such as specific dietary requirements including specific, more costly food groups (Small, 2010). Further problems described by patients included lack of information and dissatisfaction with their healthcare providers regarding perceptions of their care, lack of explanation of results, not being completely honest, kept in the dark about the seriousness of the problem, and not being clear about when dialysis would occur (Harwood et al., 2005).

- Facilitators of good care: Patients thought 1:1 time with transplant team members was helpful, and they wanted additional information sources as well, without losing 1:1 time (Korus et al., 2011).

- Impact of treatment on lifestyle: Patients mentioned that information on any modality choice, including limitations on travel, and sexual activity as areas they appreciated or would have appreciated.

- Information sources: These include sources other than healthcare professionals such as support groups and online resources.

- Equity: We did not identify direct evidence to address equity for this question.

- Acceptability: One study reported that quality-of-life issues for people with CKD include depression and anxiety, which are prevalent among people undergoing hemodialysis (Musa et al., 2018). Several small studies addressed whether screening, counseling or education might support social interactions (Kazemi et al., 2011), self-esteem (Poorgholami et al., 2015), or the families of children undergoing PD (Alhameedi and Collier, 2016).

- Feasibility: We did not identify direct evidence to address feasibility for this question. Studies that examined areas for improvement in the delivery of care included a cross-sectional study in Palestine that found self-reported adherence to diet, fluid restriction, medications, and hemodialysis sessions to be optimal in about 56% of 220 people with end-stage renal disease (Naalweh et al., 2017). A record review in New York found that lack of motivation, dialysis dependence, and comorbidities predicted failure to complete pre-transplantation preparation (Siskind et al., 2014). The authors suggested that interventions such as timely referral, educational resources, counseling, and support might increase workup completion rates or improve therapeutic outcomes.

- Implementation: We did not identify direct evidence to address implementation for this question.

- What is the clinical and cost-effectiveness of having keyworkers present in the context of KRT? [20]

- What is the clinical and cost-effectiveness of using decision aids in the context of KRT? [20].

- Can an integrated care model improve quality and decrease costs for patients with kidney disease as they transition from CKD G5 to G5D? [68].

- What is the preferred timing for educating patients regarding dialysis modalities? Does the optimal time vary based on patient characteristics? [68].

- What is the optimal content and format for educating patients regarding the advantages and disadvantages of each modality? How do we check their understanding? [68]

4.2. Performance measures

4.3. Limitations of these guidelines

4.4. Guideline dissemination and implementation

4.5. Updating or adapting of the guideline recommendations

4.6. The format of this Guideline Publication

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Memish, Z.A.; Alqahtani, A.S.; Al-Azemi, N.; Abu Alhamayel, N.; Saeedi, M.; Abuzinada, S.; Albarakati, R.G.; Natarajan, S.; Alvira, X.; Bilimoria, K.; et al. A New Era of National Guideline Development in Saudi Arabia. J. Epidemiology Glob. Health 2022, 12, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afiatin; Khoe, L.C.; Kristin, E.; Masytoh, L.S.; Herlinawaty, E.; Werayingyong, P.; Nadjib, M.; Sastroasmoro, S.; Teerawattananon, Y. Economic evaluation of policy options for dialysis in end-stage renal disease patients under the universal health coverage in Indonesia. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177436. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A.; Cheung, A.K.; Ma, J.; Cho, M.; Li, M. Effect of Baseline Kidney Function on the Risk of Recurrent Stroke and on Effects of Intensive Blood Pressure Control in Patients With Previous Lacunar Stroke: A Post Hoc Analysis of the SPS3 Trial (Secondary Prevention of Small Subcortical Strokes). J. Am. Hear. Assoc. 2019, 8, e013098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qaseem, A.; Forland, F.; Macbeth, F.; Ollenschläger, G.; Phillips, S.; van der Wees, P. Guidelines International Network: toward international standards for clinical practice guidelines. Annals of Internal Medicine 2012, 156, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guyatt, G.H.; Oxman, A.D.; Vist, G.E.; Kunz, R.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Schünemann, H.J. GRADE: An emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008, 336, 924–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schünemann, H.J.; Wiercioch, W.; Etxeandia, I.; Falavigna, M.; Santesso, N.; Mustafa, R.; Ventresca, M.; Brignardello-Petersen, R.; Laisaar, K.-T.; Kowalski, S.; et al. Guidelines 2.0: systematic development of a comprehensive checklist for a successful guideline enterprise. Can. Med Assoc. J. 2013, 186, E123–E142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schünemann, H.J.; Wiercioch, W.; Brozek, J.; Etxeandia-Ikobaltzeta, I.; Mustafa, R.A.; Manja, V.; Brignardello-Petersen, R.; Neumann, I.; Falavigna, M.; Alhazzani, W.; et al. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks for adoption, adaptation, and de novo development of trustworthy recommendations: GRADE-ADOLOPMENT. J. Clin. Epidemiology 2017, 81, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, A.K.; Chang, T.I.; Cushman, W.C.; Furth, S.L.; Hou, F.F.; Ix, J.H.; Knoll, G.A.; Muntner, P.; Pecoits-Filho, R.; Sarnak, M.J.; et al. KDIGO 2021 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Blood Pressure in Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int. 2021, 99, S1–S87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, A.S.; Bilous, R.W.; Coresh, J. Chapter 1: Definition and classification of CKD. Kidney Int. Suppl. 2013, 3, 19–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariceta, G. Clinical practice. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2010, 170, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhalla, K.; Singh, R.; Nanda, S.; Gupta, A.; Mehra, S. Correlation of spot urinary protein: Creatinine ratio and quantitative proteinuria in pediatric patients with nephrotic syndrome. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2019, 8, 2343–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NICE-NG203, 2021. Chronic kidney disease: assessment and management NICE guideline [NG203] [WWW Document]. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng203 (accessed on 29 November 2021).

- Rovin, B.H.; Adler, S.G.; Barratt, J.; Bridoux, F.; Burdge, K.A.; Chan, T.M.; Cook, H.T.; Fervenza, F.C.; Gibson, K.L.; Glassock, R.J.; et al. KDIGO 2021 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Glomerular Diseases. Kidney Int. 2021, 100, S1–S276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Sayyari, A.A.; Shaheen, F.A. End stage chronic kidney disease in Saudi Arabia. A rapidly changing scene. Saudi Med. J. 2011, 32, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, H.G.; Ginawi, I.A.; Haridi, H.K.; Eltom, F.M.; Al-Hazimi, A.M. Distribution of CKD and Hypertension in 13 Towns in Hail Region, KSA. Egypt. Acad. J. Biol. Sci. C, Physiol. Mol. Biol. 2014, 6, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Homrany, M.; Abolfotoh, M. Incidence of treated end-stage renal disease in asir region, southern saudi arabia. Saudi J. Kidney Dis. Transpl. 1998, 9, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alsuwaida, A.O., Farag, Y.M.K., Al Sayyari, A.A., Mousa, D., Alhejaili, F., Al-Harbi, A., Housawi, A., Mittal, B.V., Singh, A.K., 2010. Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (SEEK-Saudi investigators) - a pilot study. Saudi journal of kidney diseases and transplantation : an official publication of the Saudi Center for Organ Transplantation, Saudi Arabia 21.

- Mitwalli, A.H.; Al-Swailem, A.R.; Aziz, K.M.; Aswad, S.; Paul, T.; Mohammed, A.R.; Diwan, M.; Wafa, A.M. The incidence of end-stage renal disease in two regions of kingdom of saudi arabia. Saudi J. Kidney Dis. Transpl. 1995, 6, 280–285. [Google Scholar]

- Saudi Center for Organ Transplantation, 2020. Annual Report for the Saudi Center for Organ Transplantation in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (SCOT).

- NICE-NG107, 2018. Renal replacement therapy and conservative management NICE guideline [NG107] [WWW Document]. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng107 (accessed on 29 November 2021).

- Andrews, J.; Guyatt, G.; Oxman, A.D.; Alderson, P.; Dahm, P.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Nasser, M.; Meerpohl, J.; Post, P.N.; Kunz, R.; et al. GRADE guidelines: 14. Going from evidence to recommendations: the significance and presentation of recommendations. J. Clin. Epidemiology 2013, 66, 719–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwers, M.C.; Kerkvliet, K.; Spithoff, K. ; AGREE Next Steps Consortium The AGREE Reporting Checklist: a tool to improve reporting of clinical practice guidelines. BMJ 2016, 352, i1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Ballesteros, M.; Cluzeau, F.; Vernooij, R.W.; Arayssi, T.; Bhaumik, S.; Chen, Y.; Ghersi, D.; Langlois, E.V.; et al. A Reporting Tool for Adapted Guidelines in Health Care: The RIGHT-Ad@pt Checklist. Ann. Intern. Med. 2022, 175, 710–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hari, P.; Sahu, J.; Sinha, A.; Pandey, R.M.; Bal, C.S.; Bagga, A. Effect of enalapril on glomerular filtration rate and proteinuria in children with chronic kidney disease: A randomized controlled trial. Indian Pediatr. 2013, 50, 923–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, C.S.; Gutman, T.; Craig, J.C.; Bernays, S.; Raman, G.; Zhang, Y.; James, L.J.; Ralph, A.F.; Ju, A.; Manera, K.E.; et al. Identifying Important Outcomes for Young People with CKD and Their Caregivers: A Nominal Group Technique Study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2019, 74, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bress, A.P.; King, J.B.; Kreider, K.E.; Beddhu, S.; Simmons, D.L.; Cheung, A.K.; Zhang, Y.; Doumas, M.; Nord, J.; Sweeney, M.E.; et al. Effect of Intensive Versus Standard Blood Pressure Treatment According to Baseline Prediabetes Status: A Post Hoc Analysis of a Randomized Trial. Diabetes Care 2017, 40, 1401–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halbach, S. Practical application of ABPM in the pediatric nephrology clinic. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2019, 35, 2067–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, R.; Sinha, A.D.; Pappas, M.K.; Abraham, T.N.; Tegegne, G.G. Hypertension in hemodialysis patients treated with atenolol or lisinopril: a randomized controlled trial. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2014, 29, 672–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hannedouche, T.; Landais, P.; Goldfarb, B.; Esper, N.E.; Fournier, A.; Godin, M.; Durand, D.; Chanard, J.; Mignon, F.; Suc, J.-M.; et al. Randomised controlled trial of enalapril and blockers in non- diabetic chronic renal failure. BMJ 1994, 309, 833–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PROCOPA Study Group. Dissociation between blood pressure reduction and fall in proteinuria in primary renal disease: a randomized double-blind trial. J. Hypertens. 2002, 20, 729–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herlitz, H.; Harris, K.; Risler, T.; Boner, G.; Bernheim, J.; Chanard, J.; Aurell, M. The effects of an ACE inhibitor and a calcium antagonist on the progression of renal disease: the Nephros Study. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2001, 16, 2158–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saruta, T.; Hayashi, K.; Ogihara, T.; Nakao, K.; Fukui, T.; Fukiyama, K.; for the CASE-J Study Group Effects of candesartan and amlodipine on cardiovascular events in hypertensive patients with chronic kidney disease: subanalysis of the CASE-J Study. Hypertens. Res. 2009, 32, 505–512. [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, R.; Altun, B.; Kahraman, S.; Ozer, N.; Akinci, D.; Turgan, C. Impact of amlodipine or ramipril treatment on left ventricular mass and carotid intima-media thickness in nondiabetic hemodialysis patients. Ren. Fail. 2010, 32, 903–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucchelli, P.; Zuccalà, A.; Borghi, M.; Fusaroli, M.; Sasdelli, M.; Stallone, C.; Sanna, G.; Gaggi, R. Long-term comparison between captopril and nifedipine in the progression of renal insufficiency. Kidney Int. 1992, 42, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggenenti, P.; Podestà, M.A.; Trillini, M.; Perna, A.; Peracchi, T.; Rubis, N.; Villa, D.; Martinetti, D.; Cortinovis, M.; Ondei, P.; et al. Ramipril and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients on Maintenance Hemodialysis. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2021, 16, 575–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ESCAPE Trial Group; Wühl, E.; Trivelli, A.; Picca, S.; Litwin, M.; Peco-Antic, A.; Zurowska, A.; Testa, S.; Jankauskiene, A.; Emre, S.; et al. Strict Blood-Pressure Control and Progression of Renal Failure in Children. New Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 1639–1650. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A.; Cheung, A.K.; Ma, J.; Cho, M.; Li, M. Effect of Baseline Kidney Function on the Risk of Recurrent Stroke and on Effects of Intensive Blood Pressure Control in Patients with Previous Lacunar Stroke: A Post Hoc Analysis of the SPS3 Trial (Secondary Prevention of Small Subcortical Strokes). J. Am. Hear. Assoc. 2019, 8, e013098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appel, L.J.; Wright, J.T.J.; Greene, T.; Agodoa, L.Y.; Astor, B.C.; Bakris, G.L.; Cleveland, W.H.; Charleston, J.; Contreras, G.; Faulkner, M.L.; et al. Intensive Blood-Pressure Control in Hypertensive Chronic Kidney Disease. New Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 918–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, A.K.; Rahman, M.; Reboussin, D.M.; Craven, T.E.; Greene, T.; Kimmel, P.L.; Cushman, W.C.; Hawfield, A.T.; Johnson, K.C.; Lewis, C.E.; et al. Effects of Intensive BP Control in CKD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2017, 28, 2812–2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klahr, S.; Levey, A.S.; Beck, G.J.; Caggiula, A.W.; Hunsicker, L.; Kusek, J.W.; Striker, G. The Effects of Dietary Protein Restriction and Blood-Pressure Control on the Progression of Chronic Renal Disease. New Engl. J. Med. 1994, 330, 877–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winkelmayer, W.C.; Owen, W.F.; Levin, R.; Avorn, J. A Propensity Analysis of Late Versus Early Nephrologist Referral and Mortality on Dialysis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2003, 14, 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Controversies Conference on Early Identification & Intervention in CKD, 2019.

- Yang, F.; Liao, M.; Wang, P.; Yang, Z.; Liu, Y. The Cost-Effectiveness of Kidney Replacement Therapy Modalities: A Systematic Review of Full Economic Evaluations. Appl. Heal. Econ. Heal. Policy 2020, 19, 163–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadelkarim, H.; Alzayed, F.S.M.; Albluwe, H.K.A.; Alosayfir, Z.A.S.; Aljarallah, M.Y.J.; Alghazi, B.K.M.; Mohammed Ali Ghazai, A. Etiology of Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) in Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Medical Research Health Sciences 2019, 8, 177–182. [Google Scholar]

- Jha, V.; Garcia-Garcia, G.; Iseki, K.; Li, Z.; Naicker, S.; Plattner, B.; Saran, R.; Wang, A.Y.-M.; Yang, C.-W. Chronic kidney disease: Global dimension and perspectives. Lancet 2013, 382, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cass, A.; Chadban, S.; Gallagher, M. The economic impact of end-stage kidney disease in Australia: Projections to 2020. Kidney Health Australia 2010, 1–68. [Google Scholar]

- Couser, W.G.; Remuzzi, G.; Mendis, S.; Tonelli, M. The contribution of chronic kidney disease to the global burden of major noncommunicable diseases. Kidney Int. 2011, 80, 1258–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Saran, K.; Sabry, A. The cost of hemodialysis in a large hemodialysis center. Saudi J. Kidney Dis. Transpl. 2012, 23, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hamawi, K.; Al-Jedai, A.; Alsultan, M.; Almeshari, K.; Alshaibani, K.; Elgamal, H.; Alkortas, D.; Khurshid, F.; Altalhi, M. Cost analysis of kidney transplantation in highly sensitized recipients compared to intermittent maintenance hemodialysis. Ann. Transplant 2012, 17, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mushi, L.; Marschall, P.; Fleßa, S. The cost of dialysis in low and middle-income countries: a systematic review. BMC Heal. Serv. Res. 2015, 15, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwek, J.L.; Griva, K.; Kaur, N.; Chong, K.Y.; Chua, Z.Y.; Sim, G.H.A.; Ng, L.C.; Yong, P.W.; Tung, Y.-T.; Lim, L.W.W.; et al. Effectiveness and acceptability of a multidisciplinary approach in improving the care of patients with advanced chronic kidney disease: a pilot study. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2021, 54, 917–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranganathan, D.; John, G.T.; Yeoh, E.; Williams, N.; O'Loughlin, B.; Han, T.; Jeyaseelan, L.; Ramanathan, K.; Healy, H. A Randomized Controlled Trial to Determine the Appropriate Time to Initiate Peritoneal Dialysis after Insertion of Catheter (Timely PD Study). Perit Dial Int. 2017, 37, 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishani, A.; Gilbertson, D.T.; Kim, D.; Bradbury, B.D.; Collins, A.J. Predialysis Care and Dialysis Outcomes in Hemodialysis Patients with a Functioning Fistula. Am. J. Nephrol. 2014, 39, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravani, P.; Brunori, G.; Mandolfo, S.; Cancarini, G.; Imbasciati, E.; Marcelli, D.; Malberti, F. Cardiovascular Comorbidity and Late Referral Impact Arteriovenous Fistula Survival. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2004, 15, 204–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, A.K.; Levin, A.; Tonelli, M.; Okpechi, I.G.; Feehally, J.; Harris, D.; Jindal, K.; Salako, B.L.; Rateb, A.; Osman, M.A.; et al. Assessment of Global Kidney Health Care Status. JAMA 2017, 317, 1864–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, K.; Enrione, E.B. Malnutrition is prevalent among hemodialysis patients in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2012, 23, 598–608. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kiani, B.; Bagheri, N.; Tara, A.; Hoseini, B.; Hashtarkhani, S.; Tara, M. Comparing potential spatial access with self-reported travel times and cost analysis to haemodialysis facilities in North-eastern Iran. Geospat. Health 2018, 13, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cervantes, L.; Richardson, S.; Raghavan, R.; Hou, N.; Hasnain-Wynia, R.; Wynia, M.K.; Kleiner, C.; Chonchol, M.; Tong, A. Clinicians' Perspectives on Providing Emergency-Only Hemodialysis to Undocumented Immigrants. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaiviboontham, S.; Phinitkhajorndech, N.; Tiansaard, J. Symptom Clusters in Patients with End-Stage Renal Disease Undergoing Hemodialysis. Int. J. Nephrol. Renov. Dis. 2020, 13, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akkina, S.K.; Connaire, J.J.; Snyder, J.J.; Matas, A.J.; Kasiske, B.L. Earlier Is Not Necessarily Better in Preemptive Kidney Transplantation. Am. J. Transplant. 2008, 8, 2071–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, B.A.; Branley, P.; Bulfone, L.; Collins, J.F.; Craig, J.C.; Fraenkel, M.B.; Harris, A.; Johnson, D.W.; Kesselhut, J.; Li, J.J.; et al. A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Early versus Late Initiation of Dialysis. New Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 609–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishani, A.; Ibrahim, H.N.; Gilbertson, D.; Collins, A.J. The impact of residual renal function on graft and patient survival rates in recipients of preemptive renal transplants. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2003, 42, 1275–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winnicki, E.; Johansen, K.L.; Cabana, M.D.; Warady, B.A.; McCulloch, C.E.; Grimes, B.; Ku, E. Higher eGFR at Dialysis Initiation Is Not Associated with a Survival Benefit in Children. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2019, 30, 1505–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preka, E.; Bonthuis, M.; Harambat, J.; Jager, K.J.; Groothoff, J.W.; Baiko, S.; Bayazit, A.K.; Boehm, M.; Cvetkovic, M.; O Edvardsson, V.; et al. Association between timing of dialysis initiation and clinical outcomes in the paediatric population: an ESPN/ERA-EDTA registry study. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2019, 34, 1932–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandna, S.M.; Da Silva-Gane, M.; Marshall, C.; Warwicker, P.; Greenwood, R.N.; Farrington, K. Survival of elderly patients with stage 5 CKD: comparison of conservative management and renal replacement therapy. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2010, 26, 1608–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afiatin; Khoe, L.C.; Kristin, E.; Masytoh, L.S.; Herlinawaty, E.; Werayingyong, P.; Nadjib, M.; Sastroasmoro, S.; Teerawattananon, Y. Economic evaluation of policy options for dialysis in end-stage renal disease patients under the universal health coverage in Indonesia. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0177436. [CrossRef]

- Subramonian, A., Frey, N., 2020. Conservative Management of Chronic Kidney Disease in Adult Patients: A Review of Clinical Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness, CADTH Rapid Response Reports. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health, Ottawa (ON).

- Chan, C.T.; Blankestijn, P.J.; Dember, L.M.; Gallieni, M.; Harris, D.C.; Lok, C.E.; Mehrotra, R.; Stevens, P.E.; Wang, A.Y.-M.; Cheung, M.; et al. Dialysis initiation, modality choice, access, and prescription: conclusions from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney Int. 2019, 96, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nothacker, M.; on behalf of the Guidelines International Network (G-I-N) Performance Measures Working Group; Stokes, T.; Shaw, B.; Lindsay, P.; Sipilä, R.; Follmann, M.; Kopp, I. Reporting standards for guideline-based performance measures. Implement. Sci. 2015, 11, 6. [CrossRef]

- Piggott, T.; Langendam, M.; Parmelli, E.; Adolfsson, J.; Akl, E.A.; Armstrong, D.; Braithwaite, J.; Brignardello-Petersen, R.; Brozek, J.; Gore-Booth, J.; et al. Bringing two worlds closer together: a critical analysis of an integrated approach to guideline development and quality assurance schemes. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amer, Y.S.; Wahabi, H.A.; Elkheir, M.M.A.; Bawazeer, G.A.; Iqbal, S.M.; Titi, M.A.; Ekhzaimy, A.; Alswat, K.A.; Alzeidan, R.A.; Al-Ansary, L.A. Adapting evidence-based clinical practice guidelines at university teaching hospitals: A model for the Eastern Mediterranean Region. J. Evaluation Clin. Pr. 2018, 25, 550–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, F.; Lange, K.; Klose, K.; Greiner, W.; Kraemer, A. Barriers and Strategies in Guideline Implementation—A Scoping Review. Healthcare 2016, 4, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, S.; Sukumar, K.; Blanchard, S.; Ramasamy, A.; Malinowski, J.; Ginex, P.; Senerth, E.; Corremans, M.; Munn, Z.; Kredo, T.; et al. Trends in guideline implementation: an updated scoping review. Implement. Sci. 2022, 17, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paksaite, P.; Crosskey, J.; Sula, E.; West, C.; Watson, M. A systematic review using the Theoretical Domains Framework to identify barriers and facilitators to the adoption of prescribing guidelines. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2020, 29, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vernooij, R.W.M.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Brouwers, M.; García, L.M.; Panel, C. Reporting Items for Updated Clinical Guidelines: Checklist for the Reporting of Updated Guidelines (CheckUp). PLOS Med. 2017, 14, e1002207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwlaat, R.; Wiercioch, W.; Brozek, J.L.; Santesso, N.A.M.; Kunkle, R.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Anderson, D.R.; Bates, S.M.; Dahm, P.; Iorio, A.; et al. How to write a guideline: a proposal for a manuscript template that supports the creation of trustworthy guidelines. Blood Adv. 2021, 5, 4721–4726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, N.; Zhao, W.; Qi, W.-A.; Yao, C.; Dong, C.-Y.; Zhai, Z.-G.; Chen, T.; Liu, E.-M.; Li, G.-B.; Long, Y.-L.; et al. Publishing clinical prActice GuidelinEs (PAGE): Recommendations from editors and reviewers. Chin. J. Traumatol. 2022, 25, 312–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).