1. Introduction

In a preceding article [

1] on the subject, a physical model has been shown for the relationship between a pion, a muon and a muon neutrino. This model allows to give a mathematical description for the wave equation of the muon neutrino in energetic state. The wave equation has been described in terms of a two-body quantum mechanical oscillator model that reveals three quantum states for the vibration energy in the centre-of-mass. An attempt has been made to relate the energetic quantum states of the neutrino flavours with the three mass eigenstates that show up in the PMNS theory that presently is considered as the canonical theory of neutrinos [

2]. This attempt failed and no decisive relationship has been found between the quantum states of the neutrino flavours and the mass eigenstates of the PMNS theory.

The model, though, allows to incorporate the tauon and the tauon neutrino in the model. These two particles are the products of a decay mode of the charmed meson (

or

). The incorporation of the tauon/neutrino twin is possible because of the recognition, shown in the Structural Model, that the tauon is an excited state of the muon and that the charmed meson is an excited state of the pion. This recognition has been underpinned by the calculated and empirically proved mass relationships between the particles. Unfortunately, whereas the tauon/neutrino twin could be physically related with the muon/neutrino twin, the relationship between the electron/neutrino twin didn’t have a firm theoretical relationship and has been simply adopted because of symmetry reasons. Recently though, the author of this article has calculated the mass of the electron from first principles of the Structural Model, thereby showing the mass relationship between the muon and the electron by theory. It means that one of the two issues left open has been solved [

4]. The other issue, namely the problem how to give a quantitative explanation for the contents of the PMNS matrix, is still open.

What I wish to do in this article is showing the mass relationships of the neutrinos in flavour states and to demonstrate how these mass relationships relate with the mass eigenstates in the PMNS matrix.

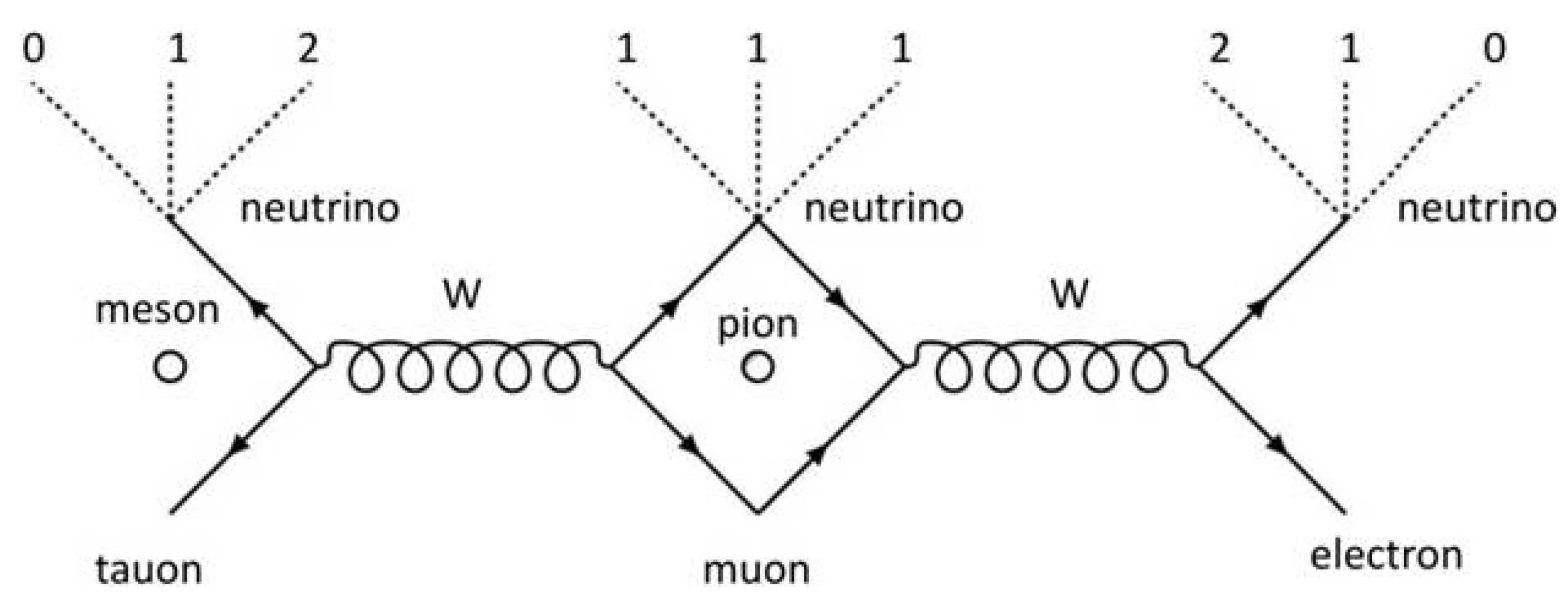

Figure 1 shows the relationship between the three lepton twins as come forward from the structural view on particle physics [

3]. It gives a structural interpretation (a) for the decay of a pion into a muon and a muon neutrino , (b) for the decay of a muon into two neutrinos and an electron and (c) for the excitation of a pion into a charmed meson. This interpretation is based upon the awareness that the

W boson has to be regarded as the relativistic state of the rest mass of the pion. The justification of this awareness has in extenso been justified in [

3]. It means that the decay of the pion state into the electron state is modeled as the muon/neutrino frame representation of the pion, similarly as the excitation of the pion state to the charmed meson state.

The two-body quantum mechanical models for the mesons, the charged leptons and the neutrinos are intimately related, but slightly different [

1]. The three quantum states of the neutrinos are represented in the figure by dashed lines at the top of the figure. We shall use this model to calculate the rest masses of the neutrinos in flavour state. The virtue of this model is the clear distinction between the masses of the neutrinos in

flavour state on the one hand and the

quantum states of the neutrinos on the other hand. The latter are usually denoted as mass eigenstates. This is a source for confusion. In fact, the quantum state model of the three neutrinos is the same in the sense of relative quantities, but might be different in the sense of absolute quantities.

The picture to take into mind is the advent of high energetic cosmic pions entering in the atmosphere. The pions convert their energy into a muons and muon neutrinos, or, alternatively, into electrons and electron (anti)neutrinos. Eventually, it is the internal energy of the pion that gets a different format. The pion’s internal energy is manifested as a W boson. This allows to consider the W boson as the relativistic state of the pion’s rest mass. We wish to consider the decay processes involved as the disintegration of the energy of the W boson into the state of observable fermions.

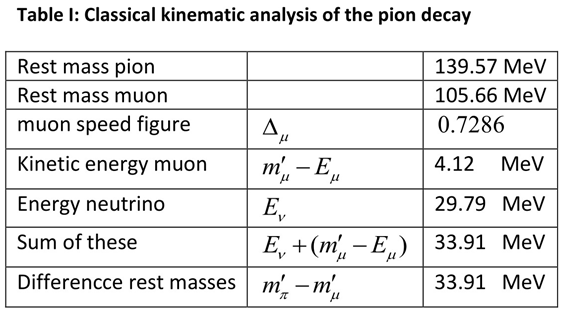

Let us start with the decay of a pion into the muon and the muon neutrino. Denoting the momenta of, respectively, the pion, the muon, and the neutrino, as

and

and their Einsteinean energies as

and

, we have, because of conservation of momentum

and, because of conservation of energy,

Usually the system is considered in the rest frame of the pion, which in the Structural Model of particle physics is an adequate representation for the lab frame. Furthermore, we wish to express the velocities of the particles in terms with their difference with the speed of light in vacuum. Hence, generally as

. This will enable to conveniently exploit the knowledge that the

W boson can be regarded as the pion’s rest mass in relativistic state. The rest masses of the particle will be written as, respectively,

and

, and the associated energies

of that state as

and

.

3. The Non-Classical Model

In this paragraph another route is followed. Rather than considering the pion in its rest frame, the pion will be analyzed in its relativistic state. To do so we rewrite the two basic equations now as

Rewriting (10b)

Multiplying (11a) by

, and subsequent subtraction gives,

Replacing the variable

by the variable

, such that,

allows to rewrite (12) as,

and, equivalently,

Eqs. (14-15) allow us to calculate

if

would be known. Subsequently the neutrino energy can be found from (10b). Generically as,

We wish to proceed by considering the implications of this analysis for three decay modes that are responsible for the production of neutrinos. These modes are formally denoted as,

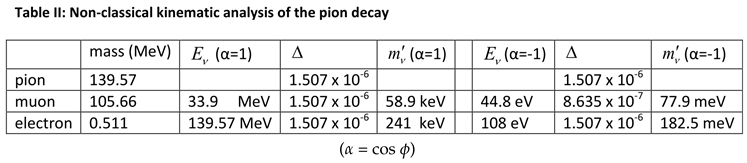

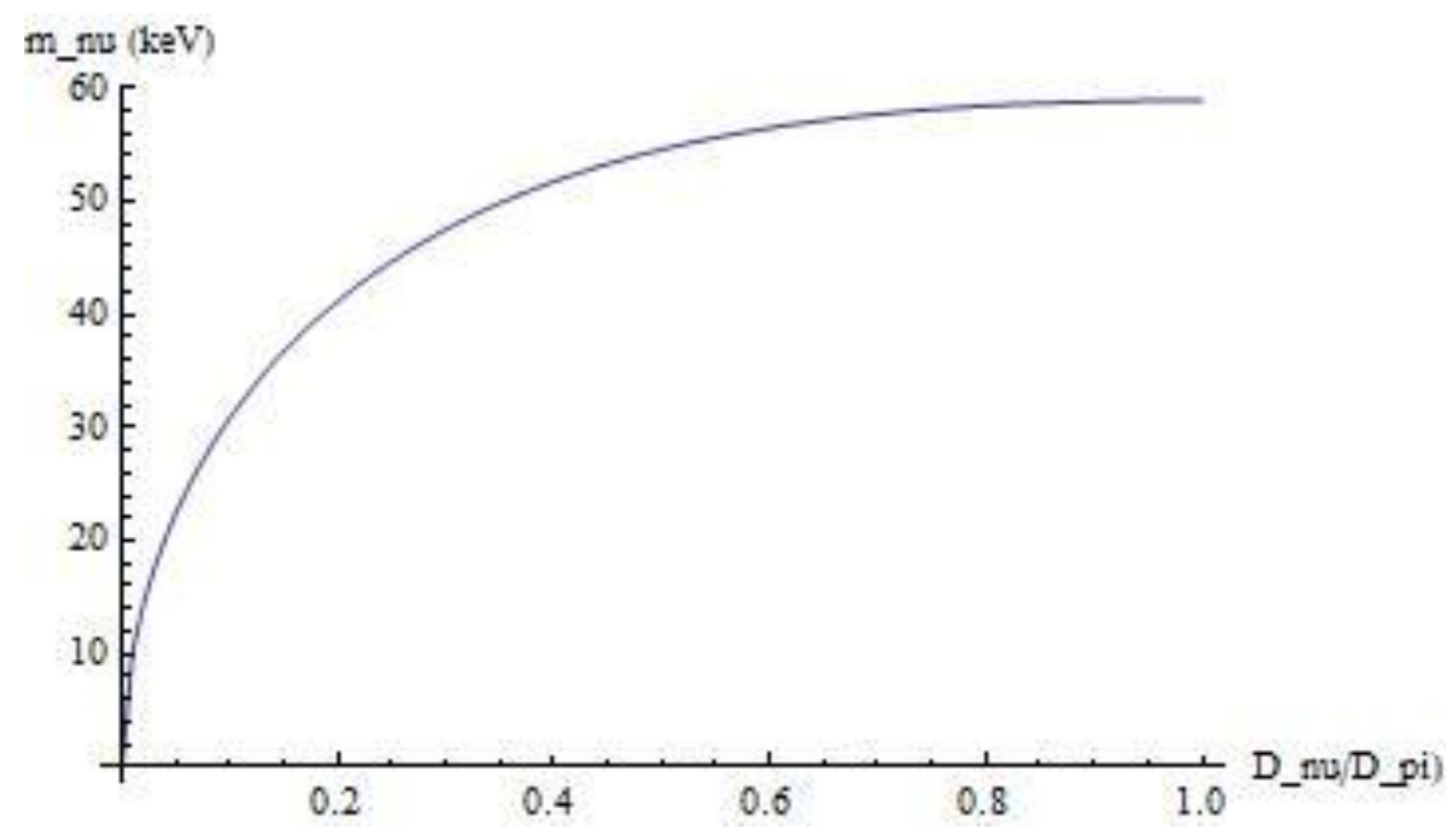

3.1. The Muon Neutrino

The application of (16) on the pion decay into muon and a muon neutrino allows to calculate the rest mass of the muon neutrino as a function of

, as shown in

Figure 2. At

the rest mass is 58.9 keV/c

2. This corresponds with the result obtained in the classical approach with the passenger model.

The result, though, requires a careful interpretation. The numerical calculation shows that the energy of the muon neutrino at the speed of the pion prior to decay can be traced back to of the energy of the boson. The other is transferred to the muon. No more, no less. Actually, though, the spread of the energy of the pion under decay is a statistical process that is subject to Fermi’s law of beta radiation. The implication of this consideration will be clear if we apply the same theory to the decay of a pion into an electron and an electron (anti)neutrino.

3.2. The Electron Neutrino

Let us proceed by considering the decay of the pion into an electron and an electron (anti)neutrino. A straightforward application of the analysis presented in the previous paragraph reveals that, under decay, the (anti-)neutrino takes almost all energy from the pion to an amount of , thereby leaving only for the electron. In that view, the rest mass of the neutrino, flying at the same speed of the pion prior to decay, would amount to 241 keV/c2. And this is a result far beyond the scale obtained from direct measurements on beta radiation, such as, for example, shown in the KATRIN project.

The approach in the KATRIN project is a direct application of Fermi’s beta radiation theory. It is a large-scale physics experiment in Germany, designed to measure the mass of the electron neutrino with unprecedented sensitivity. It studies the energy spectrum of electrons emitted in beta decay from tritium to helium-3 as formalized by

The atomic number difference between tritium and helium-3 in terms of energy is only 18.6 keV, which known to a precision of about 2 eV. Regardless of neutrino mass, the kinetic energy of the radiated electrons cannot exceed the limit of 18.6 keV + 0.2 eV. This kinetic energy is measured by applying a retarding electric potential to the radiated electrons. Electrons can only come from the endpoint of its energy spectrum. If the neutrino has some mass, this endpoint is slightly below the limit of 18.6 keV + 0.2 eV. Hence, the difference between the endpoint and the limit must be due to the rest mass of the neutrino. Fixing the endpoint of the electron spectrum requires a statistical analysis of electron counts over a narrow retarding potential window near the limit of 18.6 keV + 0.2 eV. The heart of the experimental equipment is a 70-meter-long spectrometer, one of the largest ultra-high vacuum vessels ever built. By achieving sub-eV precision, KATRIN aims to set the most stringent direct upper limit on neutrino mass. At present, this upper limit is set at 0.8 eV. Our theoretical analysis in the preceding, though, predicts a result far beyond this scale. How to explain the discrepancy?

3.3. Fermi’s Theory

In Fermi’s theory beta radiation is a process subject to the limitations of the density of states formalized by the Fermi-Dirac statistics [

9,

10]. Fermions, such as, for example, charged leptons (electron, muon, tauon) and neutral leptons (neutrinos) generated in a decay process, can only fill a state of energy if this state is freely available and not already filled by another fermion in the same state of spin. This implies that the decay process of the type described in the previous paragraphs is not a deterministic one, but a statistical one instead. A close inspection of the analysis presented so far reveals that the only parameter that can be made accountable for statistical behaviour is the scattering angle

in (1). For convenience we have adopted

for analysis. Quite probably, this condition reveals just an extreme result for the statistical distribution of the possible energies that a neutrino may adopt under decay. This view suggests that another extreme could show up for

. A slight modification of eqs. (10 – 16) allows to inspect the consequences of this consideration. Rewriting and modifying (10) gives,

Multiplying (19) by

c, and subsequent addition gives,

Replacing the variable

by the variable

, such that,

allows to rewrite (20) as,

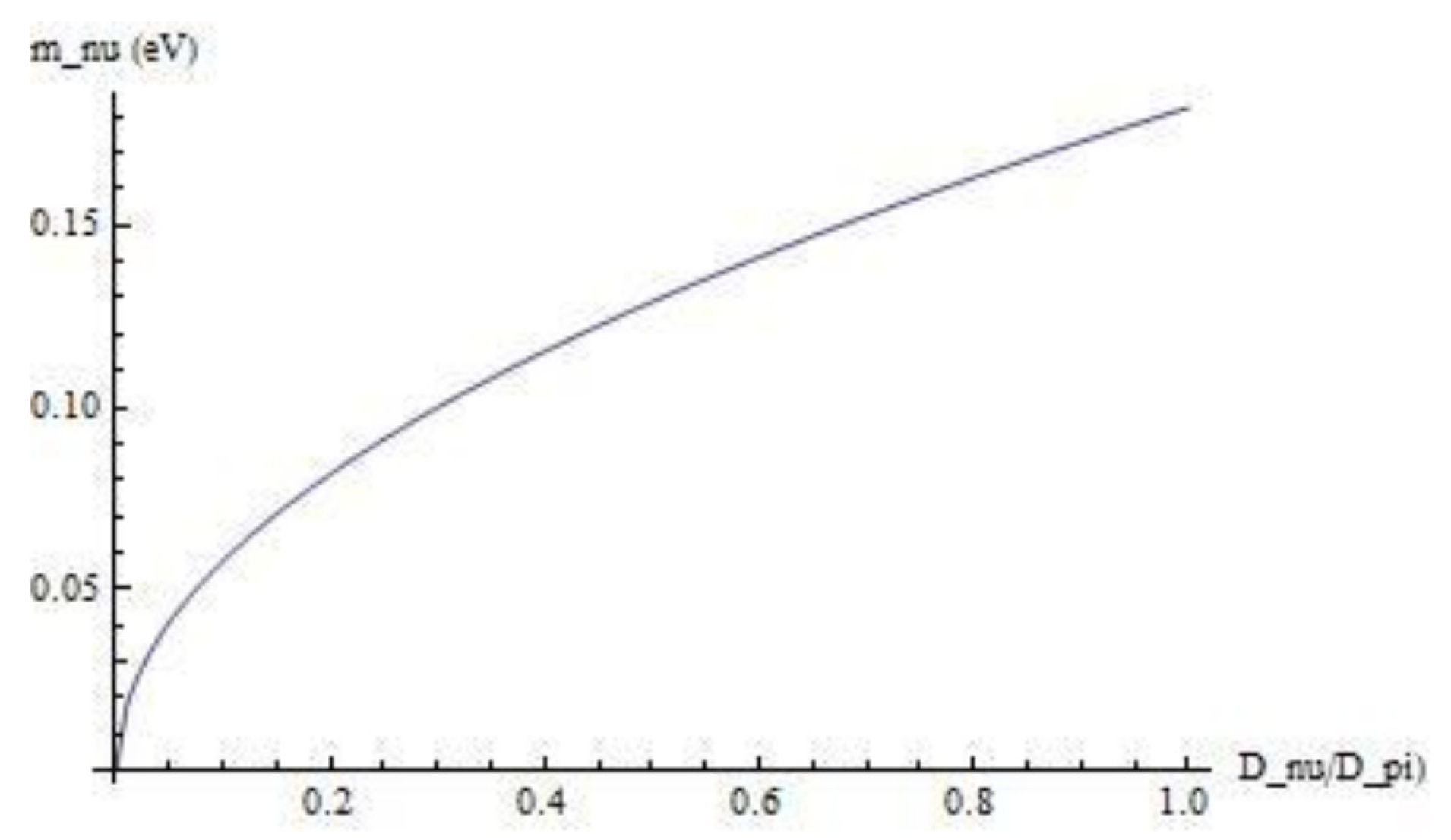

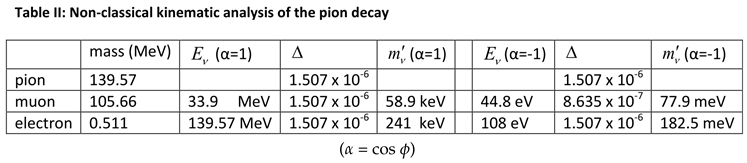

Note that the only difference between the collinear case and the anti-linear case is the sign difference between (13) and (21). The result of the rest mass calculation, though, is dramatically different. The results of the calculation for

and

, for the pion decay into, respectively, a muon and an electron, are summarized in Table II. It shows that rest mass of the electron (anti)neutrino, if, taking the rest frame of the pion as the lab frame, amounts to 182.5 meV/c

2 only if would fly at the speed of the pion prior to decay. As a function of it behaves as shown in

Figure 3.

This result is of an order of magnitude that is expected as a future result from the KATRIN experiment .

Applying the same analysis to the decay of the pion to the muon and the muon neutrino reveals that rest mass of the muon neutrino is less and amounts to 77.9 meV/c2 only. The large relative difference with the rest mass of the neutrino gives some doubt whether the comparison has been made on equal footing.

The only thing that we know that if the speed of the electron neutrino is equal to the speed of the pion prior to decay, its rest mass amounts to 182.5 meV/c

2. But there is no compelling reason why this would be the case. The same holds for the muon neutrino. There is no compelling reason why the muon neutrino would fly at that speed either. It might well be that the two neutrinos under decay from the pion move at different speeds. It is quite probable that the muon neutrino speed is different, because the decay from the pion state to the muon state is a smaller step in energy than the decay of the pion to the electron state. This is clearly demonstrated in the collinear case

. As we have seen before, in that case we have from (14), taking into consideration that

As known from (9),

which implies that

. Hence

Inserting this result in (10a) gives,

Because

, the muon neutrino flies at a significantly lower speed than the electron neutrino. The two neutrinos can now be brought on equal footing by a correction factor obtained from (26) as,

What does it say? It says that the effective mass of a muon neutrino under appropriate scaling from an electron neutrino, would amount to 77.9/0.4269 = 182.5 meV. It brings the effective mass of the muon neutrino at the same level as the effective mass of the electron neutrino. Because we are not sure if the speed of the pion prior to decay is the actual speed of the electron neutrino, the concept effective mass replaces the concept rest mass.

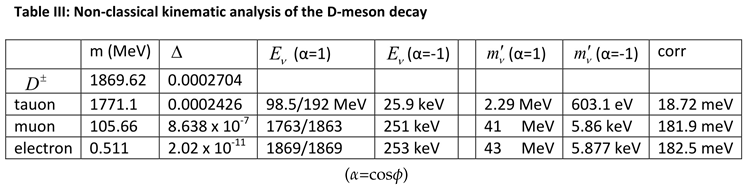

3.4. The Tauon Neutrino

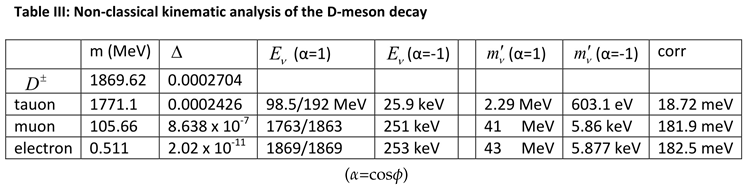

The comparison of properties between a muon neutrino and an electron neutrino appeared being possible because of the existence of a physical process in which both particles have a common origin. The particles are products in two decay modes from the archetype meson (pion). To include the tauon neutrino (the third flavour) in this comparison we would need a common decay process for all three flavours. Fortunately, the meson has three independent decay modes for the three flavours. Applying the same analysis as for the pion decay before, results are shown as summarized in Table III.

The last three columns are worthwhile to be discussed. The difference in neutrino mass between

and

needs no further discussion. Because the neutrinos are generated from the

meson, and because the meson

is (in the Structural Model) a pion in a higher state of energy, the generated neutrinos are in a higher state of energy as well. Note that the calculated mass values of the neutrino are valid on neutrino speed

. But the

value for the

meson is quite different from the

value of the pion. The neutrinos generated from the

meson decay move at a much lower speed than the neutrinos generated from the pion decay. A proper comparison should be made on equal footing. This requires a comparison on equal speed. Hence, whereas the electron neutrino shows up with a mass of 5.87 keV, it shows up at

at a much lower value. The mass scaling factor can be readily established as,

As shown in Table III, it brings the rest mass of the electron neutrino at the very same level as with the pion decay. It proves the correctness of the scaling factor.

The unscaled tauon neutrino shows a mass 603.1 eV at

. Applying the mass scaling factor

gives an effective mass for the neutrino of only 18.72 meV. However, as discussed before, this not the only scaling factor to be taken into account. Similarly, ass discussed before, a momentum correction is required to bring the tauon neutrino on equal footing with the electron neutrino. Denoting the scaling factor for the tauon neutrino with respect to the electron neutrino as

, we have

It means that the tauon neutrino would show up at the level of the electron neutrino with an effective mass of 18.72/0.102614 = 182.5 meV.

The values in Table III for the muon neutrino need a correction as well. They are underestimated as well because of the momentum scaling factor difference between the electron neutrino and the muon neutrino. It needs a correction factor to the amount of,

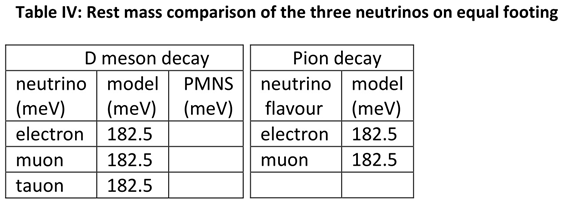

This brings the corrected effective mass for the muon neutrino at 182.5 meV. Table IV gives the summary for the three neutrino flavours compared on equal footing. It shows a third column (PMNS), which will be discussed in paragraph 4.

It is worthwhile to note, but may be superfluous, that applying the same analysis on the decay modes of the gives the same result. It is just an additional confirmation of the viability of this kinematic approach.

Important:

It is quite remarkable, and, taking into account the very different decay schemes, even more or less astonishing, that the calculated effective masses for the three neutrinos are the same to a high amount of precision. It is an unexpected result that implies that the three neutrinos are basically the same, although being manifest at different propagation speeds.

3.5. The Correspondences and the Differences Between the Three Neutrino Flavours

We have seen so far that the neutrino in pion decay shows up in two modalities. The muon modality seems to have a higher speed and a lower rest mass than the electron modality. If the rest masses would be different indeed, the muon neutrino and the electron neutrino would be different particles. Like we have seen, corrected for speed, the modalities show the same rest mass. The paradox is solved by considering the two modalities as flavours of the same particle denying the rest mass as a useful attribute and replacing it by effective mass. Knowing from experimental evidence that the neutrino flavours are uniquely bound to their parental charge lepton, there must be a difference, though. In the Structural Model of particle physics [

3] it has been shown that neutrinos have three different quantum states. The unique bond between the parental leptons and the neutrinos can be explained by adopting the view that the flavours are in a difference mixture of these quantum states. This conclusion holds for the tauon neutrino as well.

It leaves the question if for neutrinos, next to rest mass, speed is a meaningful attribute either. In fact, the neutrinos are as indistinguishable in speed as they are in effective mass. What is useful though, if not required, is defining a reference level. The reference level adopted in our analysis, is a hypothetical speed level for the electron neutrino. This speed is set equal to the speed of the pion in free flight, just before decay. This speed can be calculated from the view shown in the Structural Model that the W boson can be seen as a pion in relativistic state. It may represent actual speed, for instance in the KATRIN project, or not. The lowest state of energy that a neutrino may have is the lowest state of energy that an electron neutrino has under pion decay. In that state the neutrino has an effective mass of 182.5 meV.

4. Comparison with the (Empirical) PMNS Model

Observations on solar neutrinos and cosmic neutrinos in suitably designed and built detectors have revealed that neutrinos may change their flavour and will show up as an oscillating mixture. These observations have led to a neutrino model that decomposes each of the three flavours into a characteristic mixture of three mass eigenstates. This model has been developed over the years into a well established theory (PMNS), pioneered by Ziro Maki, Masami Nakagawa and Shoichi Sakata [

2], based upon pioneering work of Bruno Pontecorvo in 1957 [

11]. That work is a ground breaking concept that does not fit in the canonical Standard Model of particle physics. It is seen as an element in “new physics”. The adoption of a paradigm shift from the Standard Model was necessary to explain the experimentally found phenomenon of flavour oscillations in solar and cosmic neutrinos. The view on neutrinos that are produced in the lab frame decay processes that has been developed in the previous chapter, nicely fits with this view. In that respect, the Structural Model of particle physics, on which this view has been developed, would be “new physics” as well, although the author prefers to see it as “common sense physics”.

The PMNS theory recognizes three flavor components, i.e. an electron neutrino, a muon neutrino and a tauon neutrino, that are built up as a mixture of mass eigenstates such that

in which

is a 3 x 3

unitary matrix, known as the canonical PMNS matrix. This matrix is unitary and its coefficients are potentially complex. The coefficients of this matrix are determined from an interpretation of observations in the modern impressive huge underground neutrino detectors. It is basically a curve fitting procedure on measurement results. It is subject to a continuous update over the years.

To calculate effective masses from the canonical matrix, the matrix is modified to a matrix in which the coefficients are replaced by their magnitude

or by the square

of these . The most actual update (NuFIT 5.2) of the “magnitude” and “absolute squared” PMNS matrix gives [

13],

and, squared

These matrices are no longer unitary. The squared absolute PMNS matrix shows the interesting feature that the coefficients in the rows as well as in the columns sum up to 1. It reflects the probability semantics of this matrix. In fact, under proper relabeling of, respectively, the mass eigenstates and the flavour states, the semantics are conserved under interchange of the columns and interchange of the rows. This property, however, is no guarantee that the underlying canonical PMNS matrix is unitary. The reverse, though, is true. The underlying unitary matrix might have complex coefficients. These coefficients can be traced back to three canonical mixing angles

and a skewing angle

. The present NuFIT5.2 data are [

13],

While the accuracy of the mixing angles

is well established, it is not the case for the phase angle parameter,

parameter, which may assume any value between

and

[

12].

Let us discuss this empirical result with the achievements presented in the previous section in mind. In the PMNS theory, the 3 x 3 unitary matrix is built up by three unitary rotation matrices

and

, such that

,

From a mathematical point of view there is no reason why the resulting overall matrix should be composed by real coefficients only. Unitarity can be preserved if, next to the rotation angles, one or more phase angles are added, for instance by an additional matrix

Let us omit the

matrix for further discussion later.

To calculate effective masses from the canonical matrix, the matrix is modified to a matrix in which the coefficients are replaced by their magnitude

or by the square of these

, such that

Let us write the general format of the

as

From the unitarity properties of the composing rotation matrices it is found that the algebraic sum of the coefficients in any of the three rows and columns of this matrix is equal to unity. If we would like to trace back the three mixing angles, we have to solve the equation set,

We may proceed by taking into account the result of the kinematic analysis of the lab frame decay processes,

and by invoking the empirical result obtained from the oscillation observations,

Using (39-41) the equation set (37) evolves to,

in which

We have three equations with four unknown variables. These are the mixing angles

and the mass parameter

. Hence, the set seems being ill-conditioned. Apart rom the empirical values

A and

B, an additional empirical values is required to solve the set of equations. At present it is most relaibly done in short-baseline reactor antineutrino experiments, most notably:

Double Chooz (France), [

18]

These experiments look for electron antineutrino disappearance via the reaction:

They measure a deficit in the number of

detected a few kilometers away from nuclear reactors compared to the expected number at the source. That deficit is governed primarily by:

In this expression

MeV is the energy scale of the neutrinos and

km is the spacing between the point of production and the point of detection. The experiments allow to measure

as

with a precision at the few-percent level, significantly better than for

and

, [

16,

17,

18]. In this expression

E is the energy level of reactor neutrinos, typiicaly,

The solution of the set gives,

The calculated

matrix with these mixing angles gives,

It shows a fair fit with the NuFIT5.2 matrix shown in (33).

If we would maintain 182.5 meV/c

2 as reference value for the neutrinos in flavour state, we are able now to calculate the three mass eigenstates. This value has been adopted under the assumption that the speed of the electron neutrino under pion decay is equal to the speed of the pion prior to decay, But, as stated before, there is no compelling reason why this would be the case. In fact, there is more reason to adopt the speed of the muon neutrino as reference, because it is the pion to muon decay frame that in the Structural Model of particle physics has been adopted as reference frame. Adopting 77.9 meV as the effective mass of the neutrino flavours, the solution of (39-45) gives,

while the three flavour masses are all the same (77.9 meV).These figures are somewhat lower than the result predicted in [

1] from the neutrino model derived from de pion decay model in the Structural Model of particle physics. The corresponding values are

In the present status of research it is not clear which of the two sets is the most reliable one.

Note: one may wonder why the angle

is more decisive than the other two angles. It can be seen from the full expression for electron neutrino survival probability (47). Under the canonically adopted convention of the

U matrix (35) the full expression for this survival probability is [

16,

17,

18],

Under the conditions of the short base-line conditions just mentioned this expression reduces to the one shown by (47). Basically, it is due to