1. Introduction

Approximately 833 million hectares of land worldwide are considered to be affected by salinization [

1]. These affected areas are located in arid and semi-arid regions, which are characterized by high evaporation and water scarcity. Soil salinization is a threat to agricultural productivity and food security. In Tunisia, soils affected by salt are around 1.5 million hectares, which correspond to about 10% of the country area [

2]. Tunisia's total agricultural production has already decreased by 12% between 2000 and 2017 due to the effects of climate change, namely drought and water scarcity [

3]. In addition, high temperatures exacerbate soil degradation by increasing erosion rates and reducing soil moisture, which can lead to reduced crop yields and food availability. This problem is expected to intensify due to several factors, including low rainfall, high evaporation rates and the use of saline water in irrigation [

4].

In arid and semi-arid regions, climate change increases the occurrence of extreme weather events, such as floods and droughts. These events not only disturb the natural water cycle but also increase the risks of soil and groundwater salinization, which is a significant concern for agricultural systems and water quality. Imaizumi et al. [

5] highlighted the link between salt movement and groundwater flow, with salts being leached away during the rainy season. However, this salt leaching is being increasingly disrupted by the combined effects of climate change and human activities. When groundwater is withdrawn excessively, aquifers become depleted, leading to higher salt concentrations creating a feedback loop: water over-extraction contributes to soil salinization, which in turn reduces water availability and fertility. This poses a serious threat to the sustainability of agricultural practices. Soil salinity has a major impact on the environment through increased erosion of the ecosystem including reduction of vegetation cover, decrease in soil fertility, decrease in organic matter and organic carbon stock, increase in pH value, reduction of crop yield [

6,

7].

Salts are highly soluble and can be transported by surface water and groundwater. There are two types of salinity, those that occur naturally in soils and those that are caused by human activities. The latter is a growing concern because its spatial and temporal variability makes it difficult to manage [

8]. Modern irrigation, such as drip irrigation, has added complexity to how salinity is distributed in the root zone [

9]. In this case, long-term salinity management is therefore becoming more difficult [

10]. In this context, accurate spatial data on salinity levels in the root zone is crucial. This information helps optimizing water resources, manage salinity, and assess the impact of climate change on soil and water quality [

10]. Traditional soil mapping methods, which rely on field surveys and sample collection, are not always sufficient to provide timely the information needed to manage salinity [

11,

12]. These methods, while valuable, are costly and time-consuming. Moreover, they cannot provide the high spatial and temporal resolution required on a large scale [

13]. As a result, there is a growing need for more efficient and accurate methods.

One promising solution is the use of efficient non-invasive geophysical methods, which have been applied to various agricultural problematic [

14,

15,

16,

17]. The frequency domain electromagnetic induction (FD-EMI) method can provide details about soil electrical conductivity profiles from the surface to different depths. FD-EMI instruments are particularly useful for mapping variations in soil properties across different spatial scales due to their reliability, speed, and non-destructive nature [

18,

19]. Multi-frequency or multi-coil FD-EMI instruments allow for simultaneous sampling at multiple depths, enabling both vertical and horizontal distributions of soil conductivity to be assessed [

20,

21,

22]. This technique also allows creating detailed maps of soil properties such as texture, moisture content, cation exchange capacity, and salinity [

23,

24,

25]. By sensing the electrical conductivity distribution in the subsurface, FD-EMI sensors can detect spatial salinity patterns [

26]. However, interpreting the data can be challenging, as electrical conductivity is controlled by several soil properties, including porosity, pore fluid composition, and soil matrix components [

27]. Factors like FD-EMI transmitter frequency, coil separation, and soil conductivity influence the depth of penetration and the accuracy of the data [

28,

29]. By being sensitive to the pore fluid conductivity, which increases with salt concentration, these tools offer relatively accurate and timely salinity data, which can support precision agriculture and sustainable land management.

Procedures to estimate the vertical distribution of soil salinity are based on the inverse modeling of FD-EMI data [

30]. This technique uses algorithms to convert observed FD-EMI apparent electrical conductivity (ECa) data as defined in McNeil [

31] into heterogeneous subsurface models of electrical conductivity, allowing for the creation of multi-dimensional maps of salinity distribution (1D, 2D, 3D). This provides insights into soil salinity and its distribution in the root zone. In addition, quantitative interpretation with inversion software can provide detailed salinity maps at various depths [

32].

Selim et al. [

33] inverted multi-height ECa data acquired with a single channel FD-EMI sensor (CMD2) in a salt-affected irrigated area located in Egypt. Their inversion procedure generated electrical conductivity images up to a depth of 90 cm to predict the temporal and spatial soil salinity distribution. Similarly, De Carlo and Farzamian

al. [

34] used ECa data collected from a multi-configuration sensor (CMD-Mini-Explorer) in a cultivated crop in southern Italy in order to produce a detailed soil salinity distribution up to a depth of 1m. In another study, Farzamian et al. [

35] employed ECa data collected from a single channel sensor (EM38) sensor placed at several heights above ground and operated with several orientations across an agricultural area of Fatnassa Saharan oasis (southern Tunisia) using a spatially constrained 1D layered medium inversion algorithm (pseudo-3D) to characterize the spatial distribution of soil salinity. In our study, we combined ECa data from two single channel sensors (EM38 and EM31). Each of them was operated at different heights and with different coil orientations to generate 50 m profiles of soil salinity to a depth of 4 m. A pseudo-2D inversion approach based on laterally constrained 1D inversion (1D LCI) was applied to this 50 m profiles in order to characterize the lateral and vertical distribution of soil salinity and to assess the transfer of salt into deeper soil layers.

This study was conducted at 5 sites along a 4 km transect in the Merguelil irrigated perimeter in the Kairouan governorate, in the central region of Tunisia. The Merguelil site is an example of a regional scale salinity assessment due to its elevated soil salinity. The study area is characterized by a semi-arid climate where irrigation and climate change have led to increased salinity. The objectives of the study were to:

- Determine the transfer of salts from the topsoil to deeper layers by coupling the measurements of two different FD-EMI sensors (EM38 and EM31, Geonics Ltd).

- Assess the capabilities and reliability of these two devices for the detection and characterization of soil salinity by interpreting the multi-depth ECa datasets with quantitative inverse modeling methods.

- Evaluate the effect of irrigation systems (e.g., drip and sprinkler) and type of crop on the soil salinity.

- Reveal temporal variation in soil salinity using time-lapse FD-EMI surveys.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

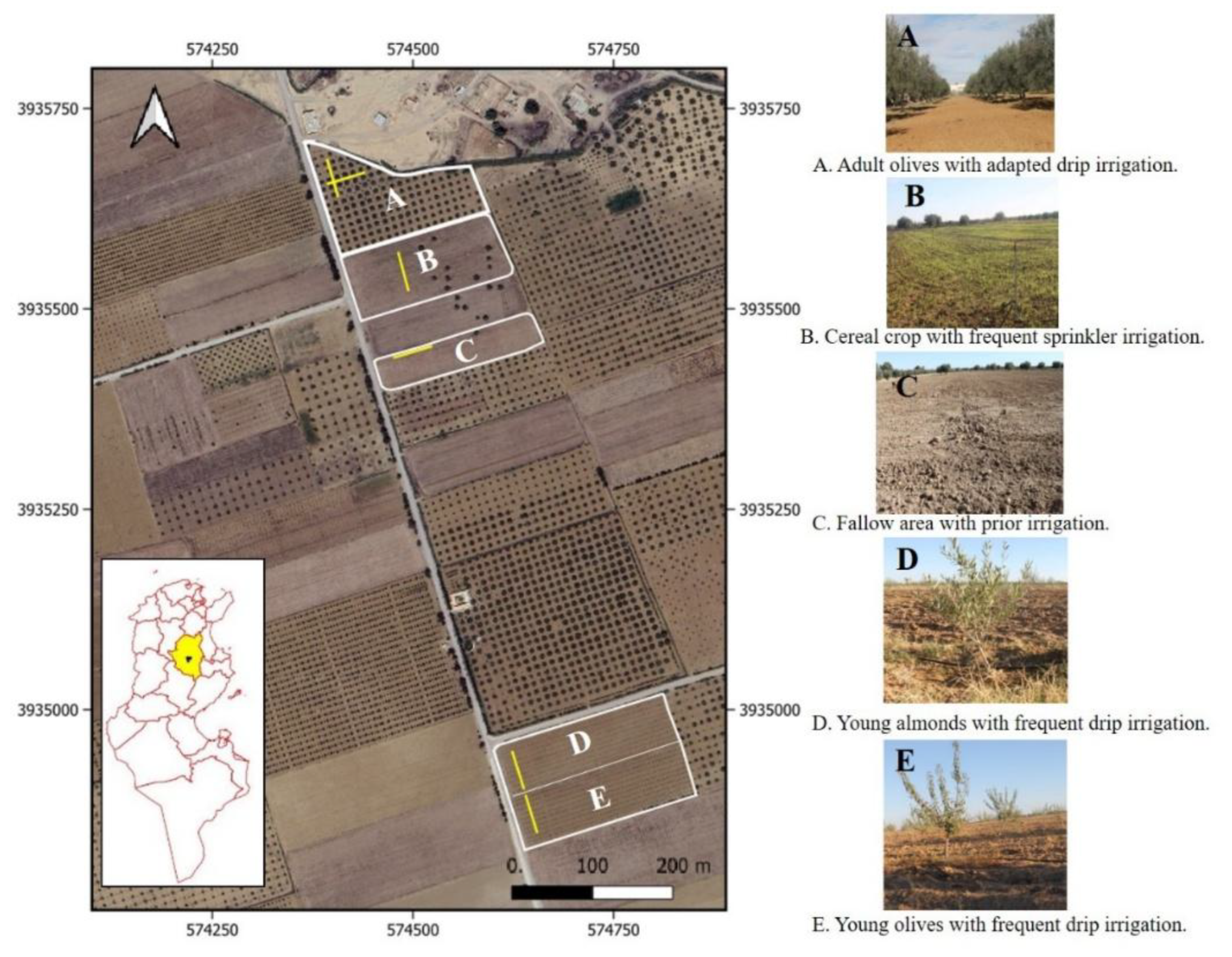

The Kairouan Plain is located in central Tunisia. This basin is filled with over 700 meters of Pliocene-Quaternary detrital sediments that were carried down from the Tunisian Mountains by numerous rivers. The most important of these rivers are the Zeroud and the Merguellil. The region has a semi-arid climate, with an average annual rainfall of 300 millimeters. The average temperature is 19.6°C, and the Penman potential evapotranspiration rate is nearly 1,600 mm per year. The groundwater table of the Kairouan Plain is the largest in central Tunisia. It is notable for its 3,000 km² extent. For over 50 years, the plain has been subject to heavy human intervention and overexploitation for irrigation and drinking water needs. Significant human interventions include the construction of large dams on the Zeroud River in 1982 and the Merguellil River in 1989. The soils have variable textures and consist of alternating layers of sandy clay, gravel, and detrital elements with varying clay content. The present study was performed at five different parcels along the transect T4 from which is located in the irrigated perimeter of Merguelil (

Figure 1). The Merguelil irrigated perimeter span across a surface of 2000 hectares and is located 7 km downstream from the dam at an altitude of 170 meters.

These five different plots were identified to represent the overall variability in crop type in term of plant species and irrigation status (see

Figure 1). At the plot level, six profile lines of 50 m length were selected by maximizing their distance from potential sources of disturbance for the FD-EMI measurements (e.g., metallic objects).Although the main initial goal was to estimate the depth distribution of soil salinity, we nevertheless perform densely sampled (1 m station spacing) FD-EMI profiles to detect lateral variations, which may be critical for our interpretation. The two first profiles (S1 and S2) are located in the plot A (

Figure 1), which covers 1.5 ha and contain 165 olive trees with 10 m x10 m spacing. This plot has a rectangular shape in the southern part and a trapezoidal shape in the northern part, where there are 21 almond trees between the olive trees. The olive trees are 23 years old, and the almond trees are 10 years old. Surface irrigation in plot A consists in supplementary drip irrigation with a rate of 1-3 times per month depending on the dryness condition, which is typically the most severe in August. The total irrigation volume in plot A ranges between 500 m3 and 1000 m3, depending on climatic conditions. No irrigation occurs in November because of harvesting activities.

The third profile (S3) is located in the plot B, which covers 1.7 ha. Plot B was left fallow from 2019 until the start of our investigation in November 2023 (4 years). At the time of our survey, this plot appeared to be homogeneous and uniform. However, historical aerial photography indicates that this profile crossed two distinct parcels. The first parcel corresponds to a non-irrigated area while the second parcel was subjected to residual irrigation (sometimes ploughed and cropped). The fourth profile (S4) was performed on plot C (1.7 ha), which is used for cereal culture. It is irrigated by sprinkler every 10 to 18 days for 18 hours (421 m³ per ha). Nineteen sprinklers, spaced approximately 10 m apart, were used for this irrigation. Two additional profiles (S5 and S6) were performed on Plot D and E, respectively. S5 one was placed in plot D between rows of young almond trees (1.5 years old) spaced with a distance of 6 m x4 m over an area of 1.25 ha with a total of 500 trees. These young almond trees are watered twice a week by drip irrigation. It should be noted that this plot was used for annual crops before it was planted with almonds.S6 was laid between rows of young olive trees (1.5 years old) at 6 m x4 m spacing for an area of 1.25 ha, with a total of 500 trees. These young olive trees are watered twice a week by drip irrigation.

2.2. Devices Used for ECa Measurements

We used loop-loop FD-EMI instruments to sense the electrical conductivity of the subsurface. The loop-loop FD-EMI method consists in generating a time-varying “primary” magnetic field with the transmitter coil, which interacts with the nearby conductive subsurface by causing eddy current. This subsurface eddy currentis in turn associated to a secondary magnetic field to be measured by the receiver coil(s). The intensity and dynamics of the eddy current (and thereby its secondary magnetic field) is controlled by the distribution of electrical conductivity within the subsurface. Loop-loop FD-EMI data are typically provided in term of ratio of the primary field (H_p) to the secondary field (H_s), which can be converted into an apparent electrical conductivity (ECa) using the method provided by McNeill [

31] although the robustness of this linear transformation is affected by the coil spacing, orientation, device height, frequency and magnetic susceptibility [

36,

37].

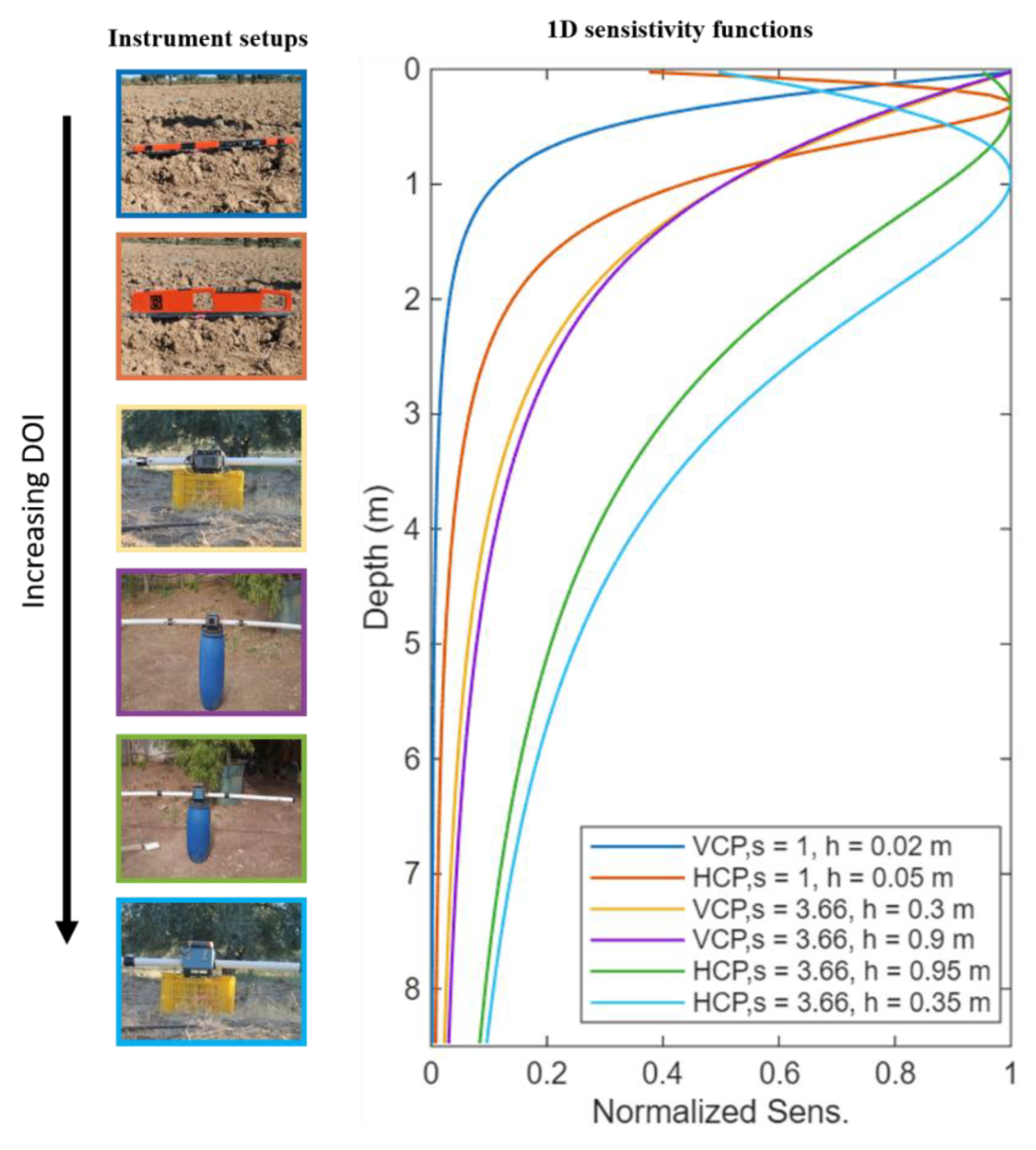

Among the wide variety of loop-loop FD-EMI devices, the EM38 sensor (Geonics Ltd) is particularly useful for agricultural studies because its sensing depth is aligned with the root zone (1.0 m to 1.5 m), allowing for the assessment of variations in soil salinity near the surface that affect crops [

28,

38]. The EM38 sensor is relatively easy to handle due to its small size (1 m) making it suitable to efficient hand-held surveying. It is designed with a transmitter and receiver coil placed 1.0 m apart at each end of a non-conducting rod and operates with a monochromatic 14.5 kHz transmitter coil.

The EM31 sensor (also from Geonics Ltd) operates with a monochromatic transmitter signal of9.8 kHz and has a coil spacing of 3.66 m, giving an apparent electrical conductivity measurement averaging up to a depth of approximately 6.0 m with horizontal co-planar (HCP) coil geometry and 3.0 m with vertical co-planar (VCP) geometry [

39]. Both devices provide a low induction number apparent conductivity LIN ECa [

31], which have been computed from the magnetic field ratio assuming a zero height, a homogenous medium, and a low frequency setting (i.e., skin depth of the eddy current much larger than the coil distance). Because both devices are single-channel sensors (one transmitter frequency and one receiver coil), the only way to measure with varying depth of investigation is to combine their data, and/or to change the height above ground, and/or to change the orientation of the coils.

Accordingly, we combine measurements from the EM38 and EM31 at different height and in both HCP and VCP geometries in order to perform multi-depth FD-EMI soundings (

Figure 2). In theory, this approach can improve the resolution and robustness of the inverse modeling, which is used to image the vertical distribution of soil salinity.

2.3. Procedure of Data Acquisition

LIN ECa data were collected along each of the six 50-meter profiles in November 2023 (dry season). This survey was repeated only for S1 (adult olives) in April 2024 (wet season) in order to determine the influence of adult olives on ECa, as olive crops are generally of primary importance in Tunisia. The EM38 and EM31 were placed at different heights from the ground and kept in the same direction. This procedure was carried out using a plastic container (

Figure 2). Care was taken to ensure that no metal parts were present in the lateral footprint of the FD-EMI soundings (i.e., within a distance of 6 m from the profiles. For each profile, 51 points spaced 1 m apart were determined, at which the ECa measurements were collected in both horizontal and vertical modes and at different heights above ground (

Figure 2).

This systematic approach allows for tracking changes in soil salinity characteristics across the different sites, while maintaining a uniform methodology for each profile. The high density of data points provides robust insights into the vertical and lateral distribution of soil salinity.

Number of Measurements Recovered

For the six profiles, ECa measurements were performed at three heights (0 m, 0.3 m, and 0.9 m) above the ground for both HCP and VCP modes. The total number of measurements was calculated as follows:

Total Measurements=6(profiles) ×50 (positions in the profile length) ×2 (coil modes) ×3 (heights) = 1800 data (corresponding to 300 measurements per profiles)

2.4. Soil Sampling

Nineteen sampling sites have been identified because of their relatively high ECa in the six profiles, with 2 to 6 boreholes per profile. At each borehole location, six soil samples were collected from the superficial layer to depths of 120 cm using hand auger. The following levels of soil layers were topsoil (0–20 cm), subsurface (20–40 m), and the subsoils (40–60 cm), (60-80cm), (80-100 cm) and (100-120 cm). Another borehole was drilled in the adult olive plot, with samples collected at 30 cm intervals from the surface to a depth of 600 cm.

2.4.1. Particle Size Analysis

The particle size of the soil was done using the Robinson pipette method [

41] to determine the granulometric proportion of each component (clay, loam and sand).

2.4.2. Soil Moisture

Soil moisture was assessed using the gravimetric method. Soil samples brought back from the study area were weighed and then placed in the oven for 24 hours. The difference between the dry and wet weights was used to calculate soil moisture:

With θ_(p=): soil moisture content in %, W_w: sample wet weight and W_D: sample dry weight.

2.4.3. Electrical Conductivity of the Paste Soil Extract (ECe)

Samples taken from the six segments to a depth of 120 cm were used to extract the soil saturated paste to determine the electrical conductivity (ECe) in the laboratory. These samples were air dried, then crushed and passed through a 2 mm mesh sieve. A quantity of 250 g was taken from each sample and brought to saturation by the gradual addition of distilled water. The soil solution extracted from each sample was used to determine ECe using a conductivity meter (VWR pHenomenal ® CO 3100L) to quantify the total concentration of soluble salts [

42].

2.5. Irrigation Water

Irrigation water is pumped by boreholes from a deep aquifer located around 400 m away. This aquifer is fed by the underground infiltration of water from the El Houareb dam built in 1989, which is located on a fault that does not allow water stacking. A network of pipes carries the water to the plots, which are served by valves at the irrigation hydrants. The water salinity has increased from 1.7 dS/m in 2014 to 2.56 dS/m in 2024 and reached the last three years (2022-2025) 3.53 dS/m. Between 2014 and 2025, the chemical composition of the water shows a notable deterioration marked by a general increase in major ion concentrations, notably chloride (Cl-), sodium (Na⁺), calcium (Ca²⁺) and magnesium (Mg²⁺). Electrical conductivity (EC) has doubled, reflecting the increasing mineralization of the water. The pH is alkaline around 7.5.

2.6. Quantitative Interpretation of FD-EMI Apparent Conductivity Data

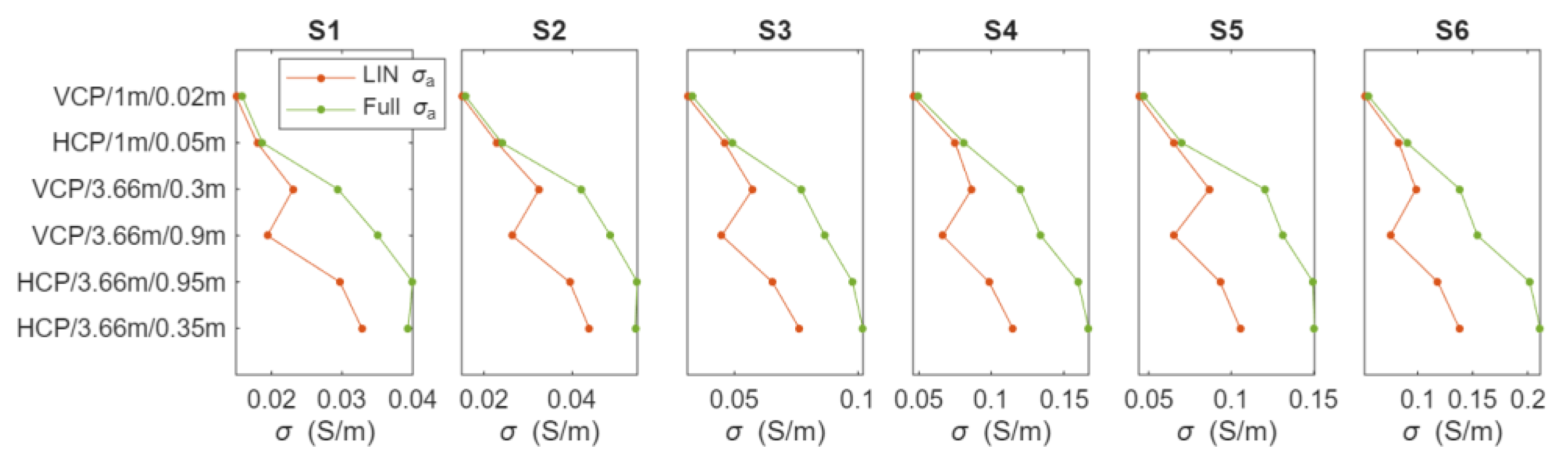

The LIN ECa readings of the EM38 and EM31 instruments are internally computed from the magnetic field measured by the receiver coil following an incomplete theory [

31]. This conversion provides reliable ECa data only for certain limited conditions like a relatively low electrical conductivity setting (< 0.05 S/m) and for instruments lying on the ground surface (as discussed above, the theory does not account for an air layer between the sensor and the subsurface). Accordingly, this theory is limited for our experiment, which involves multi-height measurements (hence requiring the modeling of the height), and which was performed above a relatively conductive medium. In order to compute robust ECa, from the instruments’ reading, we used the method discussed in Guillemoteau et al. [

36], which consists in converting the readings back to magnetic field data computing the ECa using the full theory of a homogeneous half-space, i.e., which is valid for the full range of electrical conductivity and which allows the modeling of the instrument height above ground.

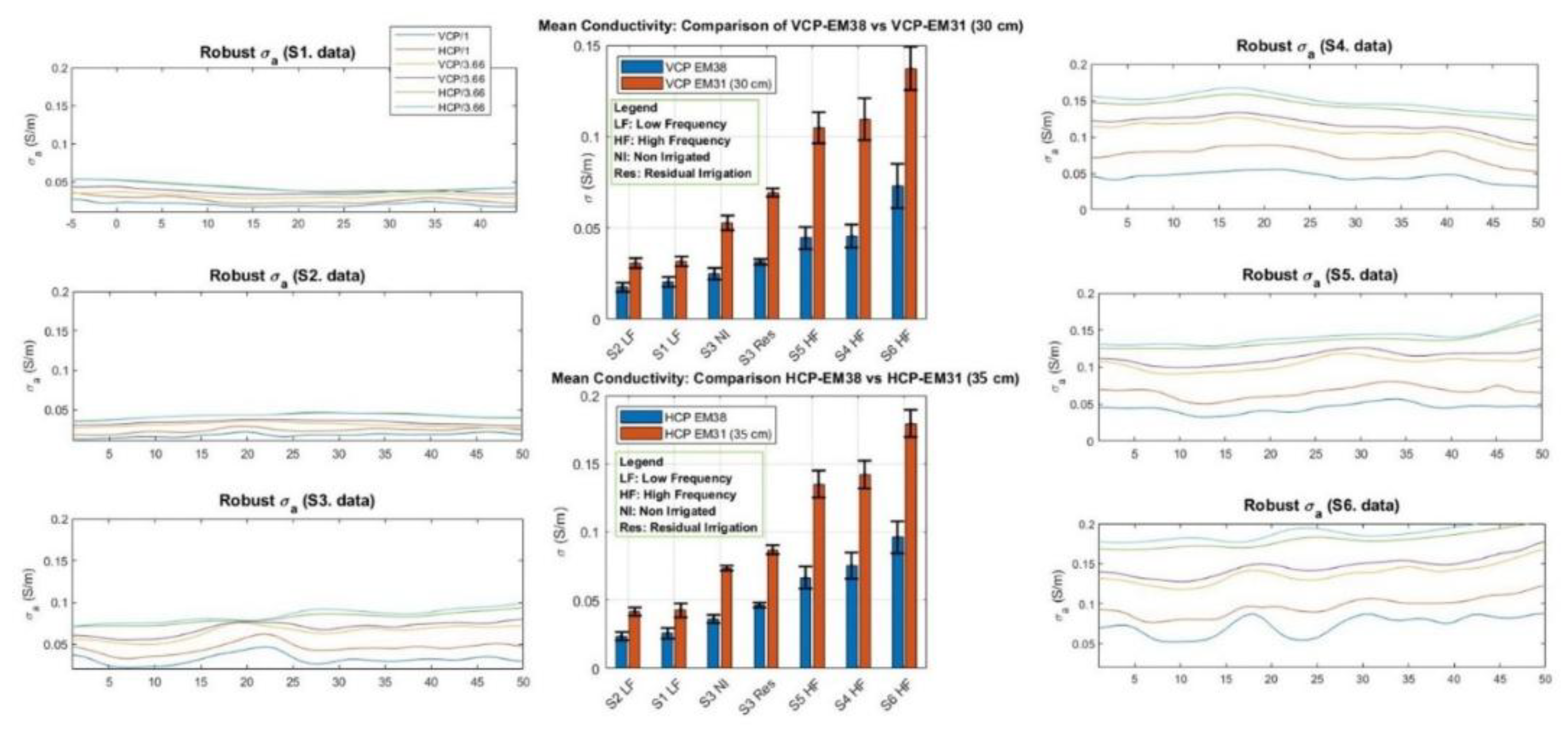

In

Figure 3, we show one example of LIN and robust ECa vertical sounding curves for the 6 sites that are considered in this study. By comparing both approaches, we see that the LIN theory systematically underestimates the apparent conductivity for the deepest channels (i.e., the ones recorded with EM 31 sensor). We also see that the LIN theory provides different trend toward depths. This is due to a strong artefact for the channel corresponding to the VCP collected at a height of 0.9 above ground. In this case, the air layer critically affects the LIN ECa reading due to a severe decrease of the secondary magnetic field with height for this coil geometry in particular. This result clearly shows that the LIN ECa reading of the instrument would bias the interpretation of our experimental multi-height and multi-configuration FD-EMI data. As a consequence, the robust ECa value will be considered in the following.

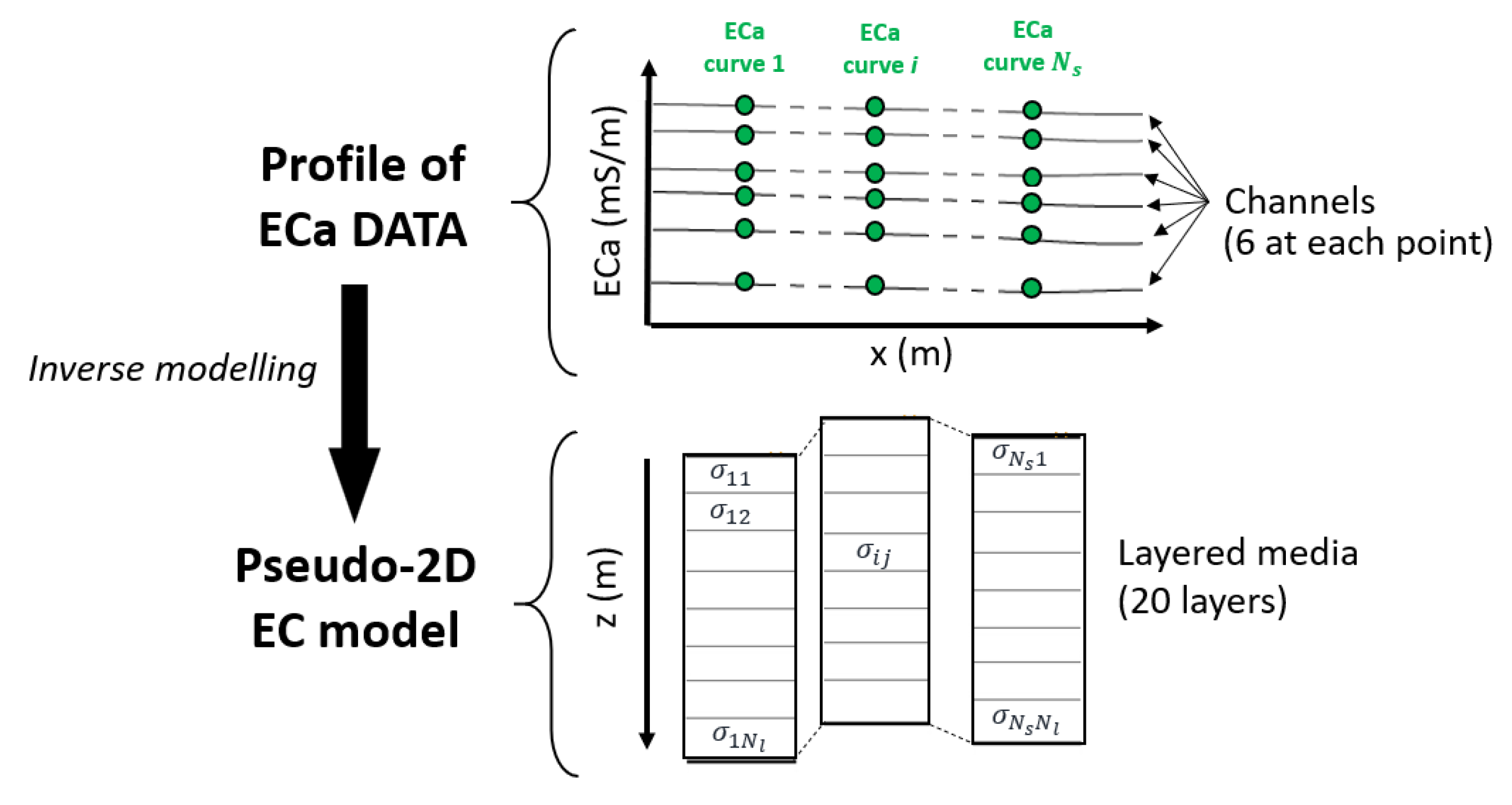

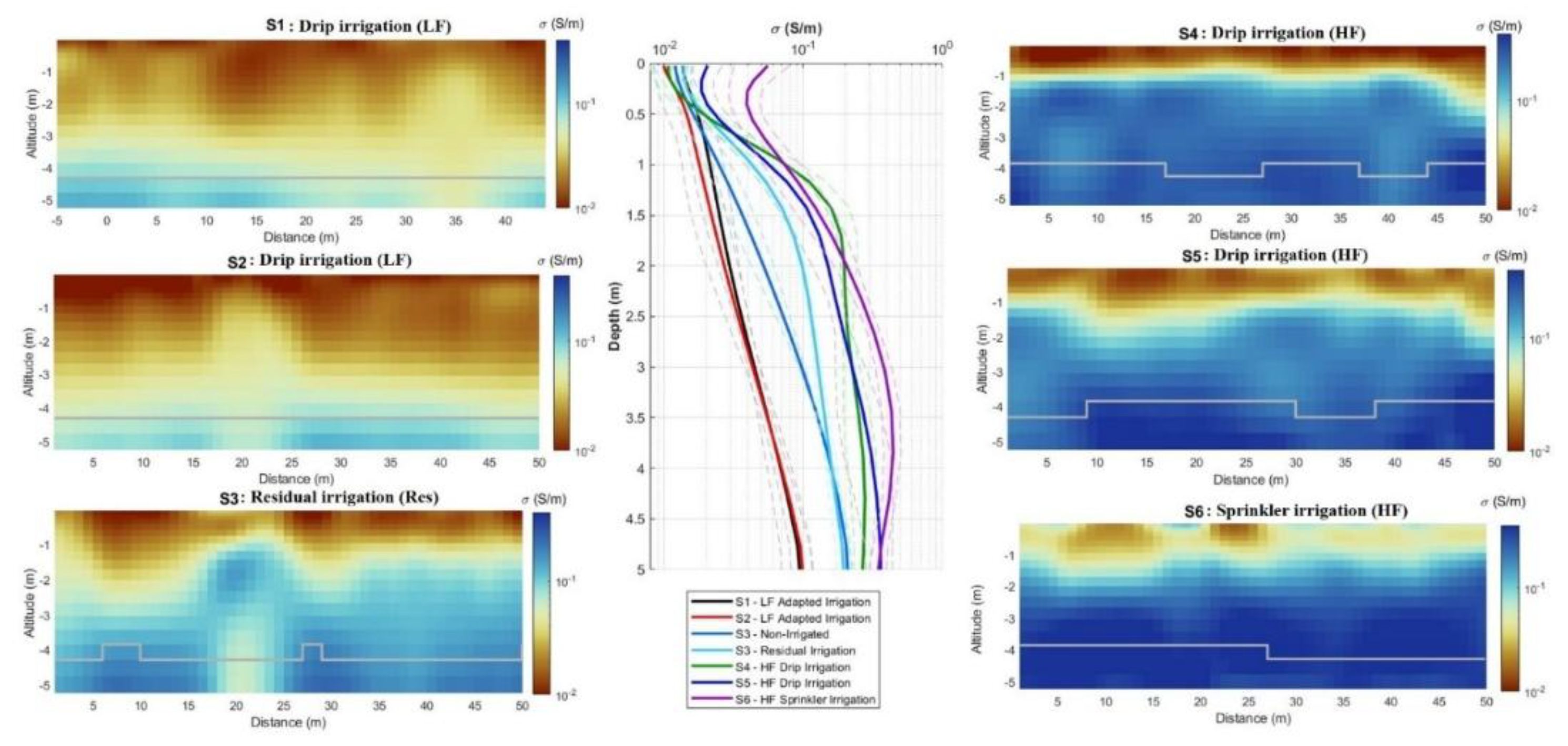

In addition to the analysis of the ECa data, we estimated the true vertical distribution of electrical conductivity through a 1D layered medium inverse modeling of the vertical sounding curves following the LCI approach described in Klose et al. [

43]. This approach is particularly relevant for our densely sampled profiles as it uses information of adjacent soundings for stabilizing the ambiguous inverse problem. The principle of this pseudo-2D electrical conductivity imaging approach is illustrated in

Figure 4.

For inverting our data, the number of layers Nl in the model space was set to 20 with increasing thickness towards deeper layers up to a depth of 5 m.

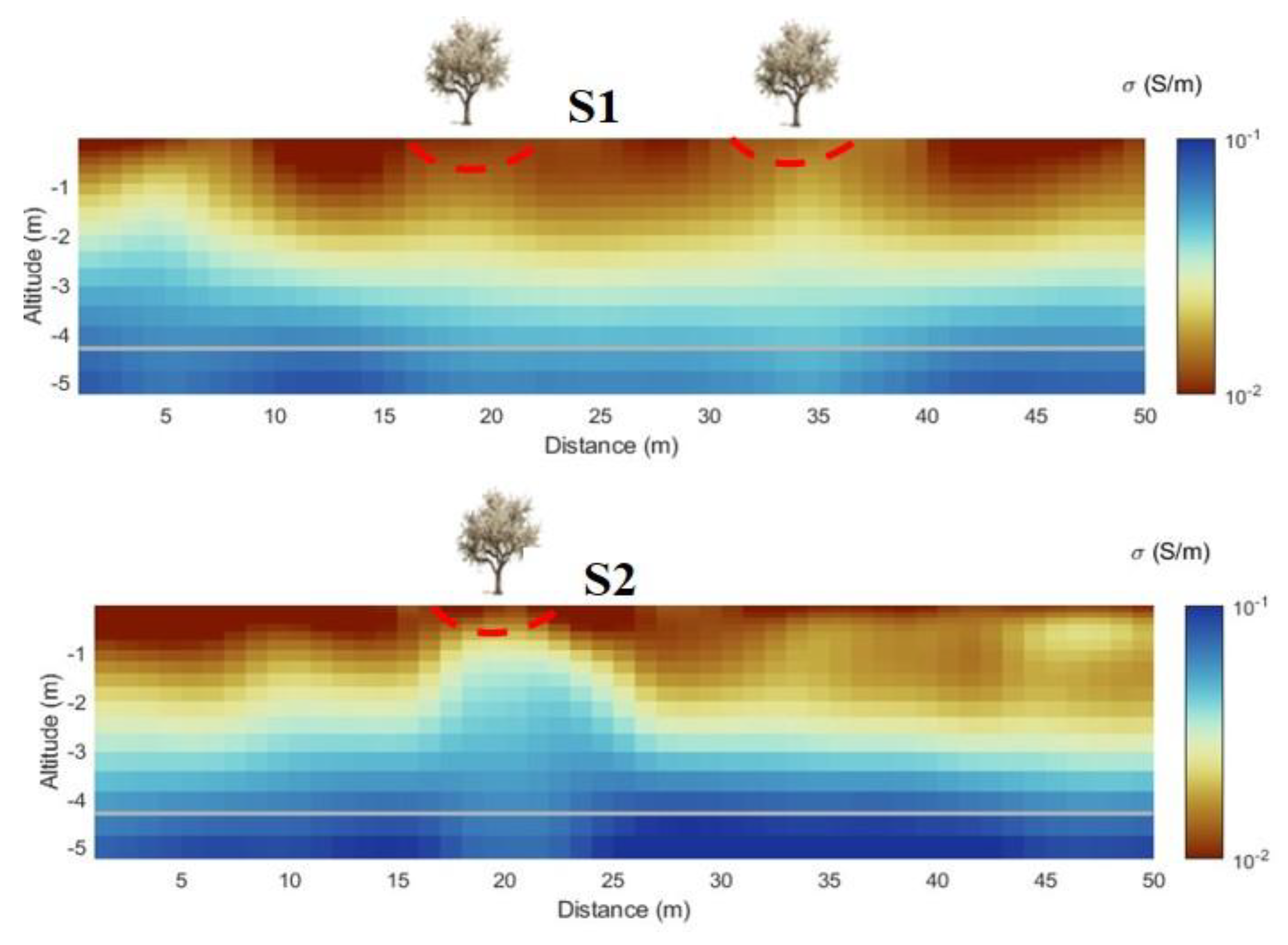

4. Discussion

For long-term complementary irrigation, significant variations in soil salinity were observed in the first profile of the adult olive trees (S1) primarily in the shallow part of the inversion model. This increase appears to be influenced by the proximity of irrigated vegetation, particularly almond trees. Similar trends were recorded in the second profile of adult olives. Thus, the main increase in electrical conductivity in the top layer corresponds to the localized irrigation near almond trees. Our results suggest a localized increase in salinity around the root zone. In these particular areas, the vigor of different crops could be significantly reduced due to the continuous accumulation of soil salts in the root zone as discussed for agricultural fields in Xinjiang (China) [

44,

45]. This phenomenon emphasizes the role of irrigation in the distribution of salts in the soil, especially in irrigated environments. The results are consistent with previous studies which indicate that agricultural activities had a more significant influence on topsoil salinity which leads to stronger variation than soil salinity at deep layers [

46]. Moreover, Jantaravikorn and Ongsomwang [

47] found a higher variation of soil salinity at the topsoil than at the subsoil relying it to agricultural activities, such as paddy fields and field crops.

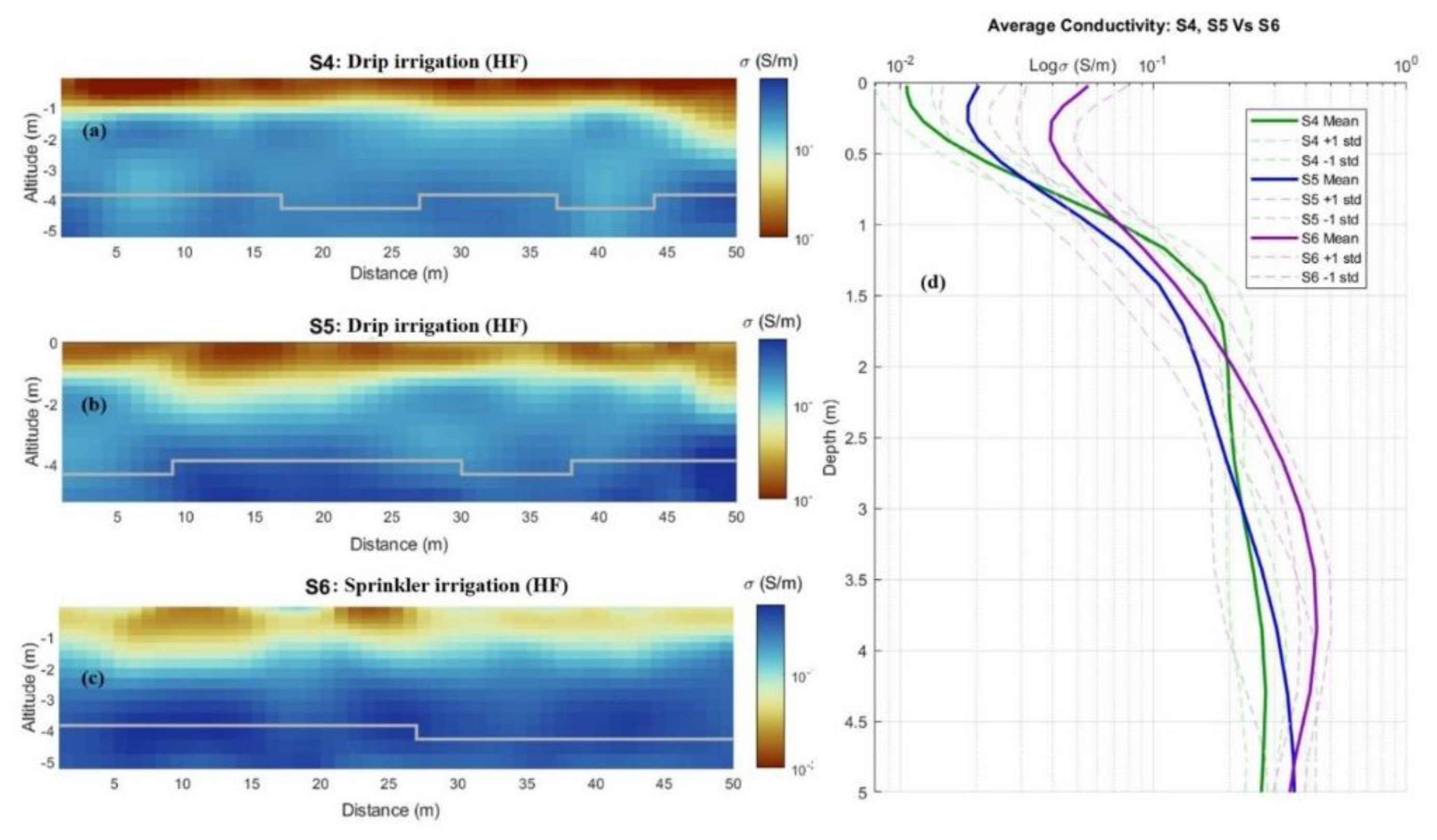

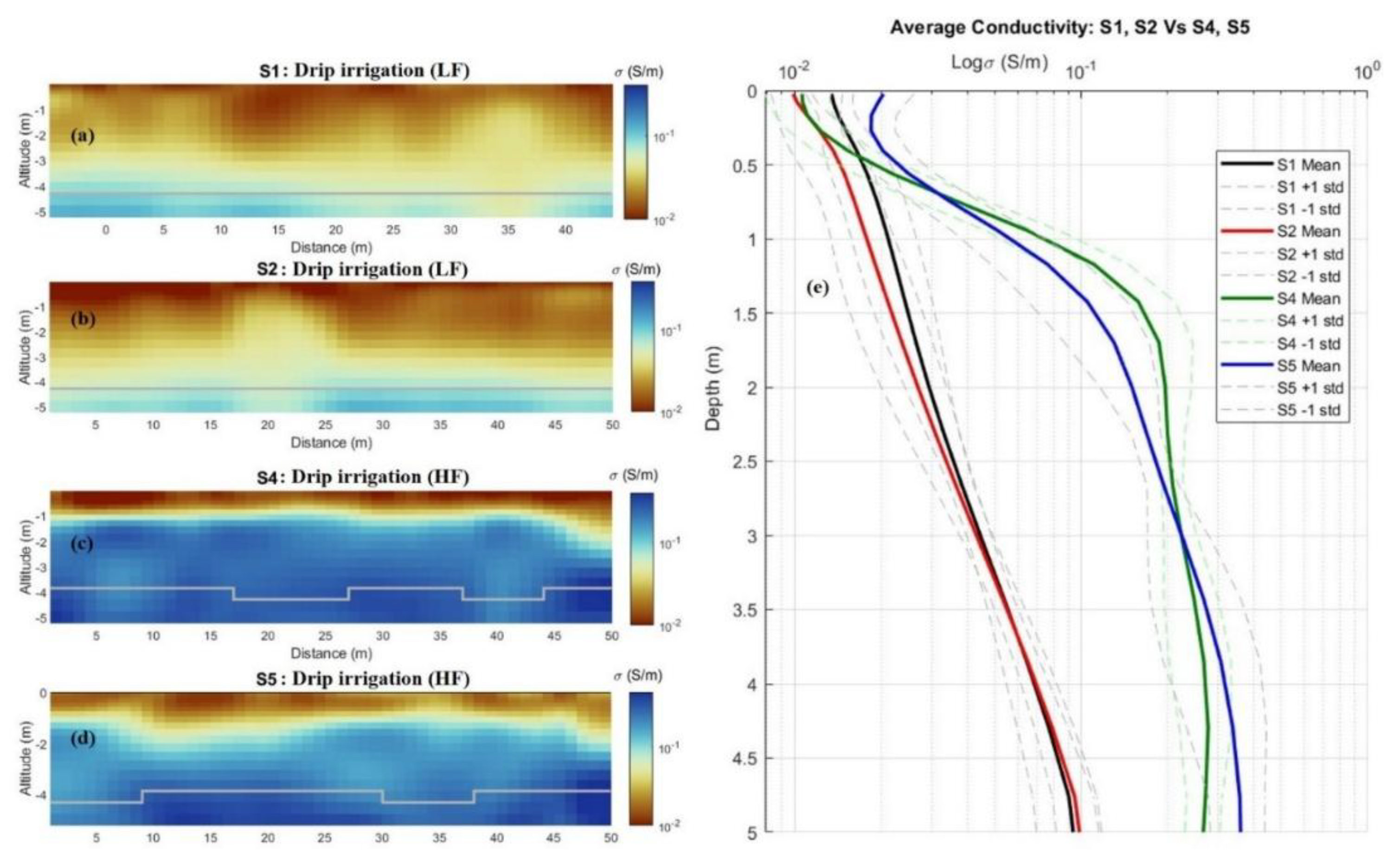

For permanent crops such as young trees of almonds and olives (1.5 years old) and annual crops like cereals, which have relatively short irrigation periods (up to 18 months), salinity variations appear influenced by the irrigation system and regime. The results of the inversion profiles for young almond trees show that the conductivity was relatively low at the upper soil level, but increase to 0.1 S/m from 1.1 m depth. For young olive trees, the inversion model shows a low conductivity of 0.01 S/m between 1 and 2 m depth, which increases thereafter. Under intensive, frequent drip irrigation, both soil segments exhibit low apparent electrical conductivity (ECa) in the topsoil, with a progressive increase from a depth of 1 m onward. A similar result was reported by Yang et al. [

45] that drip irrigation, characterized by high frequency has the potential to leach salts into lower soil layers in the short term. This pattern suggests that salinization may become a problem for perennial crops with deep root systems. Therefore, attention should be paid to the distribution characteristics and dynamics of salinity throughout the root zone [

48].

Average electrical conductivity depth curves and inversion models revealed significant salinity variations depending on the type and frequency of irrigation. Olive and almond plantations, for example, that used drip irrigation generally had low conductivity values in the topsoil compared to cereal crops irrigated with sprinklers, which had significantly higher salinity in the upper soil layers. These results underscore the critical impact of irrigation methods on soil salinity dynamics, especially in the upper layers. Drip irrigation results in less salinity accumulation than sprinkler irrigation in annual cereals. These findings align with those of Karimzadeh et al. [

49], who found that drip irrigation was the most effective method for preventing secondary salinization and that sprinkler irrigation was the least effective. Their results demonstrate that furrow and drip irrigation systems perform better than sprinkler systems in terms of salt management.

Inversion results for young trees with high-frequency drip irrigation and mature olive trees with low-frequency drip irrigation indicate a significant effect of irrigation frequency on the spatial variability of soil salinity in the surface layers. Adult olive trees with low-frequency drip irrigation showed lower conductivity values in the upper layers than young olive trees with high-frequency drip irrigation. This is consistent with the findings of Karimzadeh et al. [

49], who explain that high-frequency (HF) sprinkler irrigation reduces the soil's ability to absorb precipitation due to the presence of irrigation water. This leads to salt accumulation in the root zone. They also found that, with low-frequency (LF) sprinkler irrigation, the soil could be drier than with high-frequency (HF) sprinkler irrigation. Therefore, drier soil had a greater capacity to retain water before reaching its field capacity in the event of rainfall. These findings suggest that, in this context, the type of irrigation system (drip or sprinkler) and the frequency of irrigation (high or low) can affect salinity in topsoils.

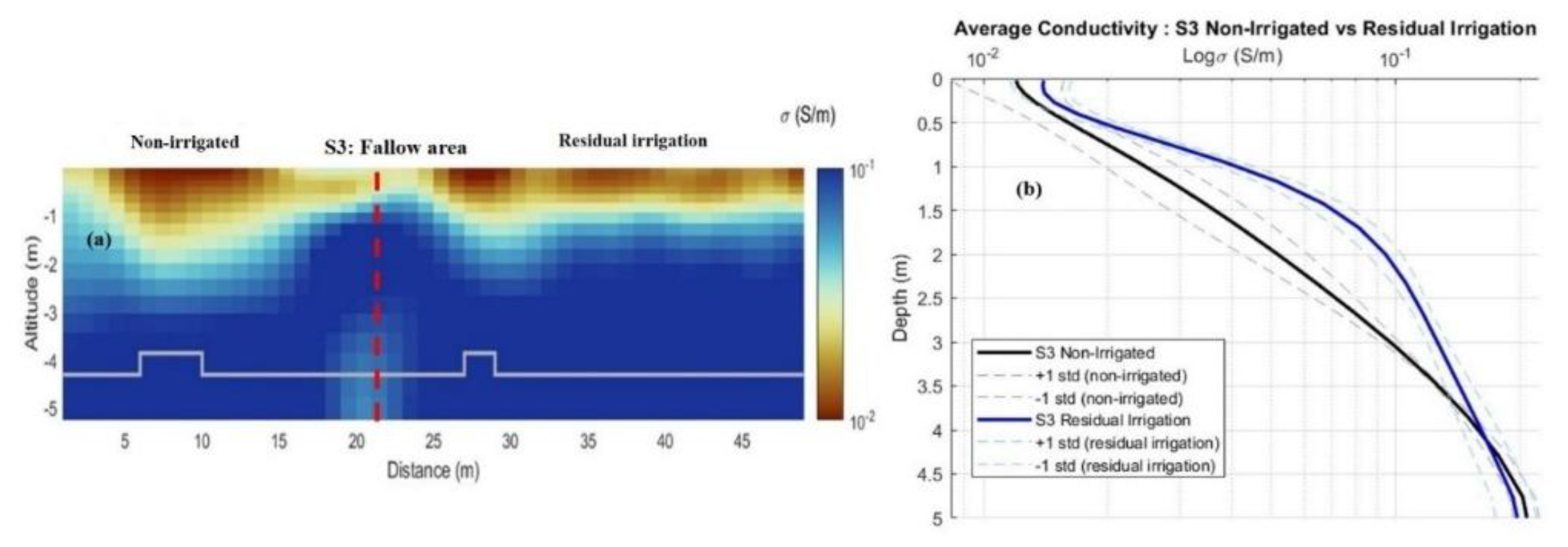

Proper irrigation management can mitigate the adverse effects of salinization on crop productivity. This spatial variation of electrical conductivity was also observed in the fallow segment, mainly in the topsoil. Thus, a body of 20 m length with low electrical conductivity was observed, followed by an abrupt increase of 2 m length. The rest of the section then had relatively high electrical conductivity. This variation in electrical conductivity along the profile should be related to the history of cultivation/irrigation. According to satellite images (Google Earth) derived from previous years, the land use and crop rotation of this plot shows different situations. In the first part, electrical conductivity was low due to an uncultivated area. For the last part, the increase in electrical conductivity should be the result of previous irrigation. Here, crops and irrigation are absent; the spatial variation is then explained with the help of satellite images showing a persistent effect of previous irrigation on salinity increase. It is worth noting that others have used satellite information. For example, Casterad et al. [

50], used satellite data, soil sampling and a proximal electromagnetic induction technique to assess the spatial distribution of soil salinity along a previously irrigated field.

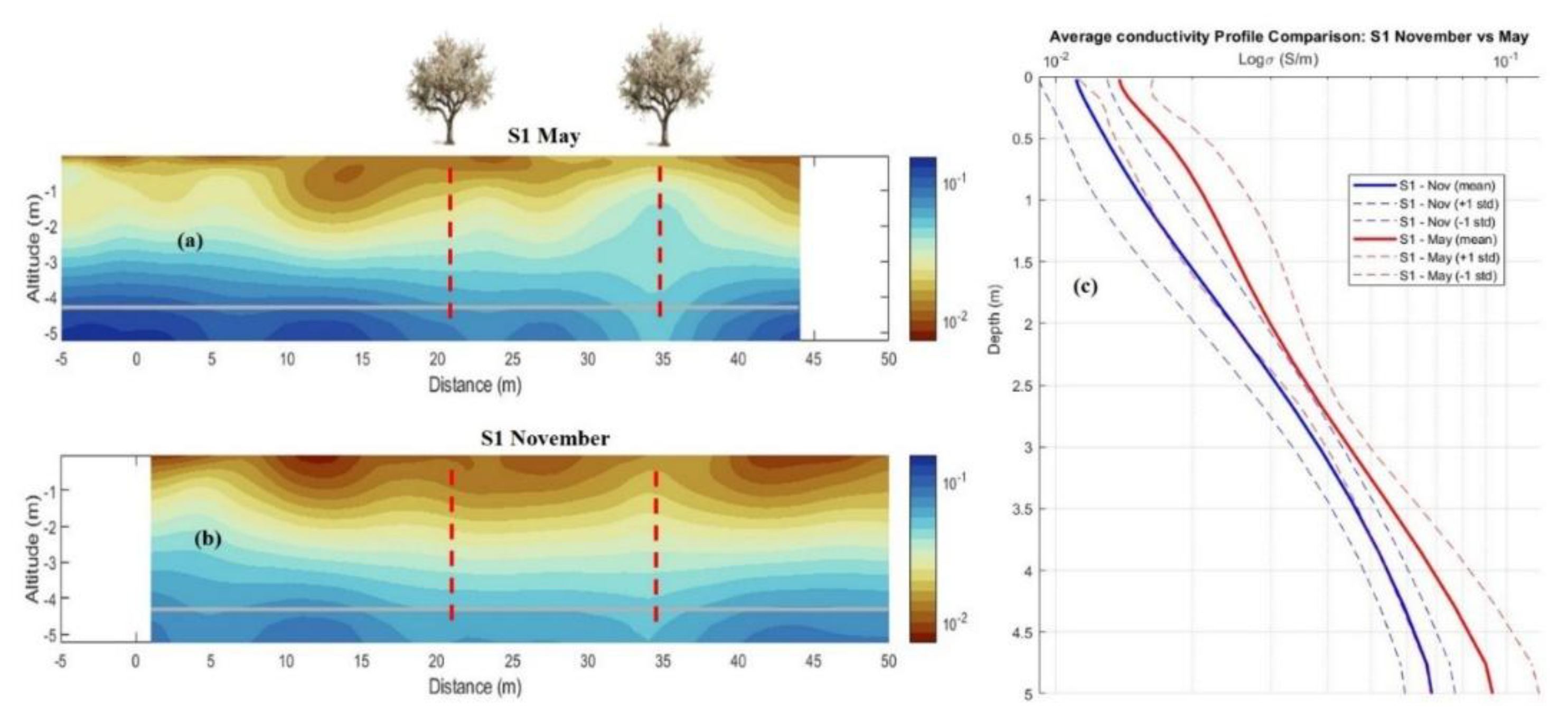

The lasting effect of irrigation on soil salinity was also observed in an area where an infiltration test was done in 2022 which is clearly revealed later in the mapping and inversion model. Such result suggests that even a single instance of irrigation can affect soil salinity for several months or years. In addition to spatial variation, soil salinity could express a temporal variation. This was emphasized in an area analyzed in a wet (November) and a dry (May) period. The inversion profile shows relatively lower conductivity in November 2023 compared to May 2024. Irrigation and rainfall could explain this seasonal variation in soil salinity. This is consistent with Eltarabily et al. [

51], who attribute variations in soil salinity at different times to shifts in irrigation water salinity due to, among others, winter rainfall events.

The inversion approach provides a better and more reliable reconstruction of the subsurface electrical conductivity distribution than the classical method based on the calculated ECa average. Our results demonstrate that the pseudo-2D inversion approach helps in finding a reliable reconstruction of the subsurface electrical conductivity distribution. For example, the Pseudo 2-D inversion image of drip irrigation for young trees showed different response compared to sprinkler irrigation for cereals, as well as the effect of drip irrigation near the almond trees in adult olive segments. The inversion results made it possible to know the history of the plot. It is the case of the fallow segment and the infiltration test carried out in 2022. Also, the inversion result has allowed tracking the temporal variation of the soil salinity during a wet and a dry period. Our results of pseudo-2D inversion demonstrate the ability to detect variations in soil salinity at different depths and provides a clearer understanding of how agricultural practices, such as irrigation frequency and system as well as crop type, influence soil salinity at different depths. As previously reported, the advantage of these methods using FD-EMI sensors is that multiple ECa measurements can be easily converted using inversion procedure to infer soil salinity at different depths and generate detailed images of the soil salinity profile with high accuracy [

30,

52,

53].

The lithotypes of the sedimentary layers are constituted of Loam mixed with particles of fine silt and inclusions of clay. Stratification of such texture enables water infiltration and salt transfer. Our inversion results show a similar pattern, consisting of a shallow low conductive layer and a deeper high conductive layer, showing an increase in conductivity and salt transfer with depth. The salinity of irrigation water has increased. In fact, excess salts may be removed by winter rainfall and pushed into the vadose zone up to the aquifer, leading to over salinity of the water as a resource [

54]. The tendency to accumulate salts during the irrigation season can have negative effects not only on soil health but also on groundwater quality [

55].

In the context of groundwater management, these findings should be considered in order to balance water demand and consumption, thereby increasing water savings and protecting the soil. The less saline water required, the less salt will accumulate while maintaining crop yields.

By combining our data from the two FD-EMI sensors, a complete profile of soil salinity to a depth of 4 m was obtained. Our results are consistent with others [

56,

57] that sensor data fusion can provide many possible benefits, such as less imaging ambiguity, expanded attribute utility, and complementary information on specific soil properties.

The aim of raising the apparatus (EM38 and EM31) above ground level is to introduce others ECa measurement between initial data enabling to improve the vertical resolution of “1D inversion” imagery and this by avoiding certain gaps that appears between layers. When the EM38 and EM31 are placed on the surface of the ground (i.e. at zero height), the theoretical investigation depths of EM38 (ECa-VCP and ECa-HCP) are up to 0.75 m and 1.2 m respectively, while those of the EM31 (ECa-VCP and ECa-HCP) are 3 m and 6 m respectively. However, when these instruments are placed at 30, 35, 90 and 95 cm above the ground, the depth of investigation is modified, which provide additional information to constraint the 1D electrical conductivity imaging/inversion problem. This is consistent with the suggestion of Heil and Schmidhalter [

57] and Selim et al. [

33] that for single channel FD-EMI instruments, it is possible to detect layering with measurements at different heights above ground.

Author Contributions

D.A. (Dorsaf Allagui); Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, visualization, M.H. (Mohamed Hachicha); Conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, writing—review and editing, visualization, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition, J.G. (Julien Guillemoteau); conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, writing—review and editing, visualization, supervision.

Figure 1.

Location (left) and description (right) of the parcels where the 50-meter profiles have been performed.

Figure 1.

Location (left) and description (right) of the parcels where the 50-meter profiles have been performed.

Figure 2.

Each sounding consists in positioning the EM38 and EM31 instruments at different heights from the ground (h = 0 to 95 cm) in both HCP and VCP configurations (right). The 6 geometries allow for sensing at 6 different depths as illustrated by the corresponding 1D sensitivity functions (left), which we computed using the thin layer perturbation approach [

36,

40].

Figure 2.

Each sounding consists in positioning the EM38 and EM31 instruments at different heights from the ground (h = 0 to 95 cm) in both HCP and VCP configurations (right). The 6 geometries allow for sensing at 6 different depths as illustrated by the corresponding 1D sensitivity functions (left), which we computed using the thin layer perturbation approach [

36,

40].

Figure 3.

LIN and robust (full theory) apparent conductivity data for six soundings, each being representative of the six profiles, which are considered in this study. For each sounding, the six channels’ points are shown from top to bottom following increased depths of investigation, which were derived from the analysis of the vertical sensitivity computation (

Figure 2).

Figure 3.

LIN and robust (full theory) apparent conductivity data for six soundings, each being representative of the six profiles, which are considered in this study. For each sounding, the six channels’ points are shown from top to bottom following increased depths of investigation, which were derived from the analysis of the vertical sensitivity computation (

Figure 2).

Figure 4.

Principle of the laterally constrained inverse modeling used to interpret the profile of multi-channel FD-EMI ECa data. The 6 channels correspond to the different instrument geometries, which are described in

Figure 2. All the profiles contain N_s=51 soundings and were inverted by considering stitched subsurface layered media composed of N_l=20 layers distributed between 0 and 5 m below ground surface.

Figure 4.

Principle of the laterally constrained inverse modeling used to interpret the profile of multi-channel FD-EMI ECa data. The 6 channels correspond to the different instrument geometries, which are described in

Figure 2. All the profiles contain N_s=51 soundings and were inverted by considering stitched subsurface layered media composed of N_l=20 layers distributed between 0 and 5 m below ground surface.

Figure 5.

The distribution of robust ECa data measured along the six different segments and comparison of the average apparent conductivity determined by VCPEM38 Vs VCPEM31 and VCPEM38 Vs VCPEM31 as a function of the segments. Intervals are standard deviations. Abbrev. S1&S2: Adult olives with low frequency adapted irrigation system, S3 (NI): Fallow area non-irrigated, S3 (Res): Fallow area with residual irrigation S4&S5: Young olives and almonds with high frequency drip irrigation, S6: Cereals with high frequency sprinkler irrigation.

Figure 5.

The distribution of robust ECa data measured along the six different segments and comparison of the average apparent conductivity determined by VCPEM38 Vs VCPEM31 and VCPEM38 Vs VCPEM31 as a function of the segments. Intervals are standard deviations. Abbrev. S1&S2: Adult olives with low frequency adapted irrigation system, S3 (NI): Fallow area non-irrigated, S3 (Res): Fallow area with residual irrigation S4&S5: Young olives and almonds with high frequency drip irrigation, S6: Cereals with high frequency sprinkler irrigation.

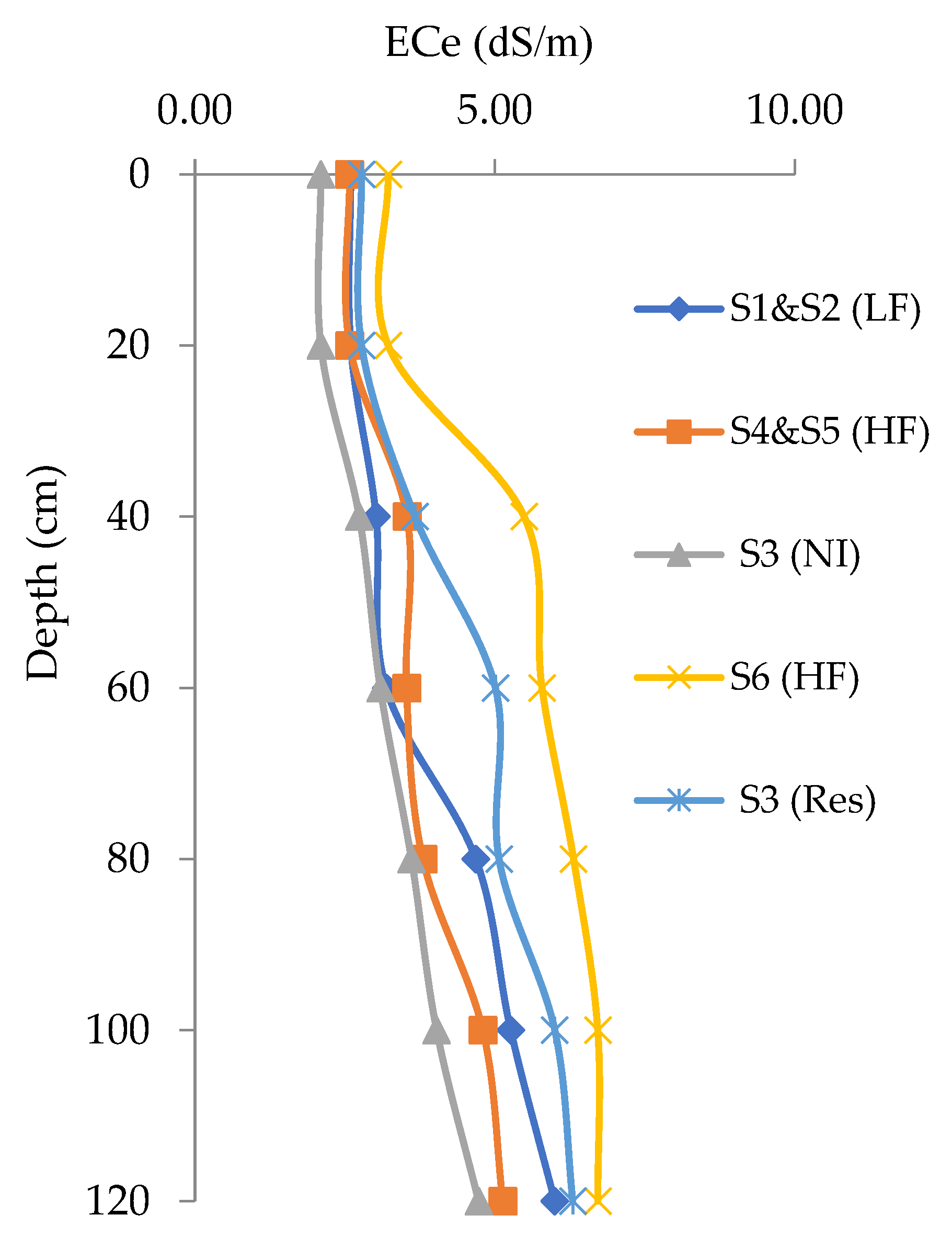

Figure 6.

Distribution of soil salinity according to depth and irrigation regime.

Figure 6.

Distribution of soil salinity according to depth and irrigation regime.

Figure 7.

Pseudo 2-D inversion of apparent conductivity data for the six profiless under different irrigation management regime and their average versus depth (center graphic). Abbrev. S1, S2: Adult olives with low frequency drip irrigation system, S3 Fallow area with residual irrigation, S4, S5: Young olives and almonds with high frequency drip irrigation, S6: Cereals with high frequency sprinkler irrigation.

Figure 7.

Pseudo 2-D inversion of apparent conductivity data for the six profiless under different irrigation management regime and their average versus depth (center graphic). Abbrev. S1, S2: Adult olives with low frequency drip irrigation system, S3 Fallow area with residual irrigation, S4, S5: Young olives and almonds with high frequency drip irrigation, S6: Cereals with high frequency sprinkler irrigation.

Figure 8.

The inverted ECa data measured along the segments of adult olives S1 and S2 and the effect of trees. Abbrev. S1, S2: Adult olives with low frequency drip irrigation system.

Figure 8.

The inverted ECa data measured along the segments of adult olives S1 and S2 and the effect of trees. Abbrev. S1, S2: Adult olives with low frequency drip irrigation system.

Figure 9.

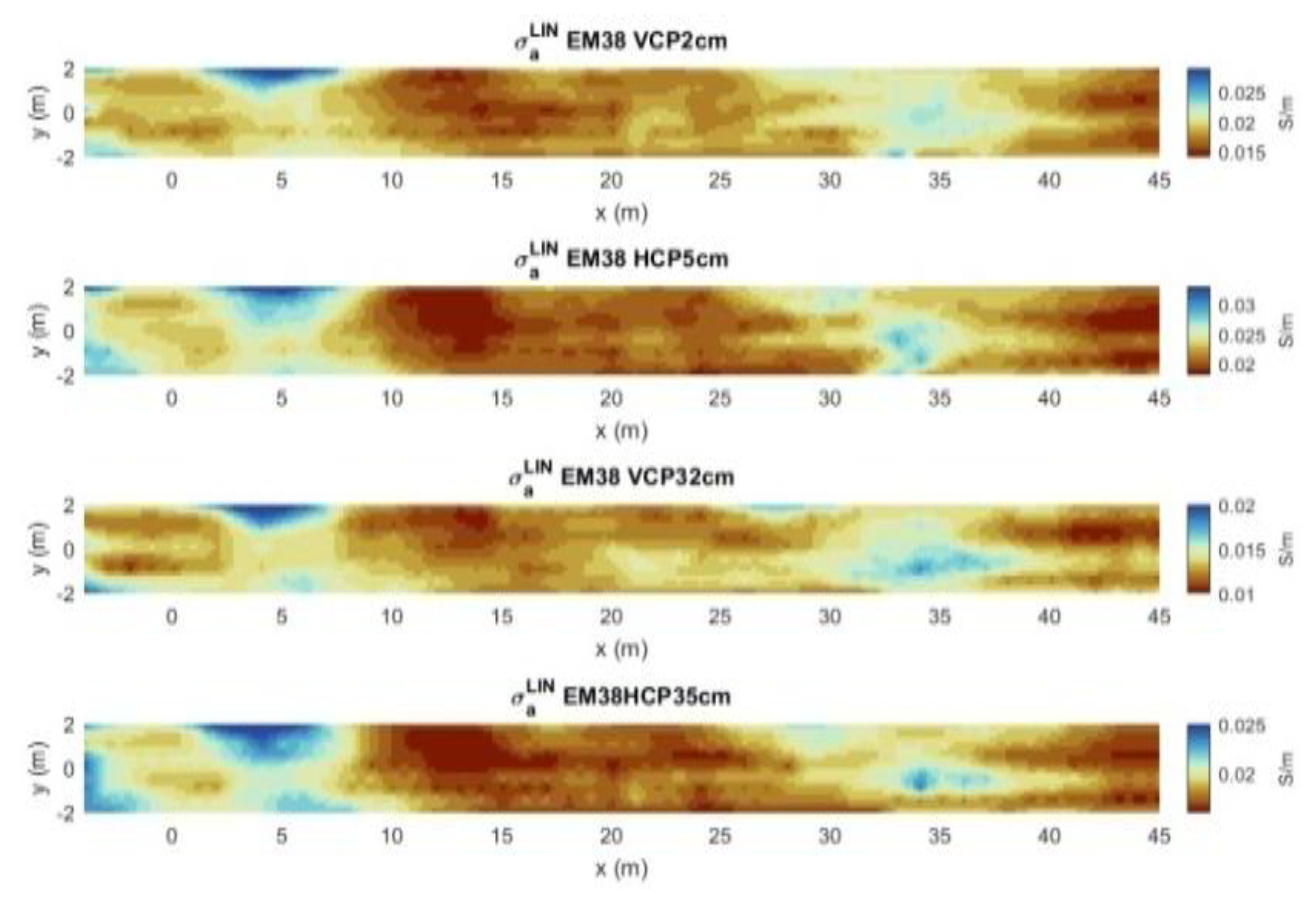

Mapping of measured ECa in both horizontal and vertical operation modes, at measurement heights of 2 cm, 5 cm, 35 cm, 32 cm, and 35 cm (May 2024), shows an increase in ECa at x = 5 m, x = 20 m, and x = 35 m.

Figure 9.

Mapping of measured ECa in both horizontal and vertical operation modes, at measurement heights of 2 cm, 5 cm, 35 cm, 32 cm, and 35 cm (May 2024), shows an increase in ECa at x = 5 m, x = 20 m, and x = 35 m.

Figure 10.

Inversion results varied between the drip and sprinkler irrigation systems. (a) Segment of young almonds (b) Segment of young olives with high frequency (HF) drip irrigation (c) Segment of cereals with high frequency (HF) sprinkler irrigation (d) Corresponding mean results and their standard deviation for each pseudo-2D model layer.

Figure 10.

Inversion results varied between the drip and sprinkler irrigation systems. (a) Segment of young almonds (b) Segment of young olives with high frequency (HF) drip irrigation (c) Segment of cereals with high frequency (HF) sprinkler irrigation (d) Corresponding mean results and their standard deviation for each pseudo-2D model layer.

Figure 11.

Inversion results varied depending on the frequency of the drip irrigation system (low or high). (a) First segment of adult olives irrigated with low frequency irrigation (LF). (b) Second segment of adult olives irrigated with low frequency irrigation (LF). (c) Segment young almonds with high frequency irrigation (HF). (d) Segment of olives with high frequency irrigation (HF). (e) Corresponding mean results and their standard deviation for each pseudo-2D model layer.

Figure 11.

Inversion results varied depending on the frequency of the drip irrigation system (low or high). (a) First segment of adult olives irrigated with low frequency irrigation (LF). (b) Second segment of adult olives irrigated with low frequency irrigation (LF). (c) Segment young almonds with high frequency irrigation (HF). (d) Segment of olives with high frequency irrigation (HF). (e) Corresponding mean results and their standard deviation for each pseudo-2D model layer.

Figure 12.

Inversion results along a fallow area S3 (a) and Corresponding mean results and their standard deviation for each pseudo-2D model layer (b).

Figure 12.

Inversion results along a fallow area S3 (a) and Corresponding mean results and their standard deviation for each pseudo-2D model layer (b).

Figure 13.

Inversion results in both periods (a) May 2024 (b) November 2023 and corresponding mean results and their standard deviation for each pseudo-2D model layer (c).

Figure 13.

Inversion results in both periods (a) May 2024 (b) November 2023 and corresponding mean results and their standard deviation for each pseudo-2D model layer (c).

Table 1.

Average moisture content (%) and ECe (dS/m) (N=133).

Table 1.

Average moisture content (%) and ECe (dS/m) (N=133).

| Parameters |

Moisture content (%) |

ECe (dS/m) |

| Mean |

11 |

3.99 |

| Median |

10 |

3.75 |

| Min. |

5 |

1.71 |

| Max. |

17 |

8.92 |

| CV (%) |

32 |

38 |

Table 2.

Adopted salinity scale.

Table 2.

Adopted salinity scale.

| Salinity |

ECe |

ECa(rounded values) |

| Low |

<2 |

<40 |

| Medium |

2-4 |

40-60 |

| High |

>4 |

>60 |

Table 3.

Grouping of segments by land use and irrigation system management.

Table 3.

Grouping of segments by land use and irrigation system management.

| Segments |

Land use |

Irrigation system management |

| S1 and S2 |

Adult trees(Mature olive trees)

|

Adapted drip irrigation |

| S4 and S5 |

Young trees(Young almond and olive trees)

|

Frequent drip irrigation |

| S6 |

Irrigated Cereal (wheat) |

Frequent sprinkler irrigation |

| S3 |

Fallow land with irrigated antecedent |

Irrigation stopped from 2019 |