Submitted:

21 October 2025

Posted:

22 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

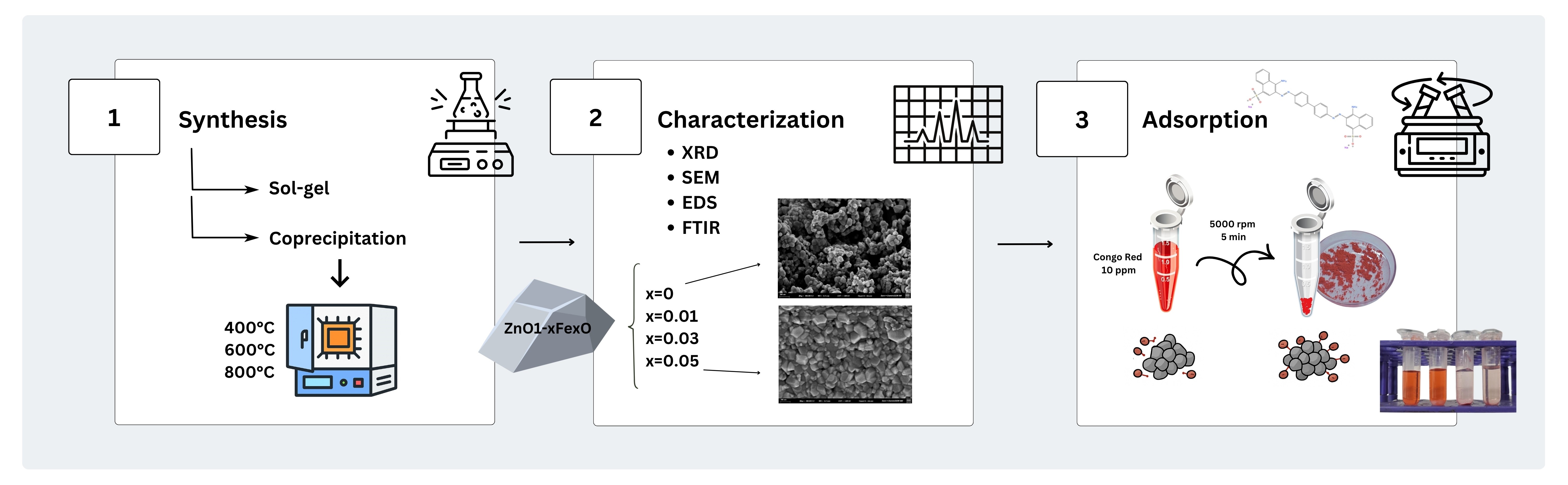

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Synthesis of Zn1−xFexO Nanoparticles

2.3. Characterization

2.4. Adsorption Assays

3. Results

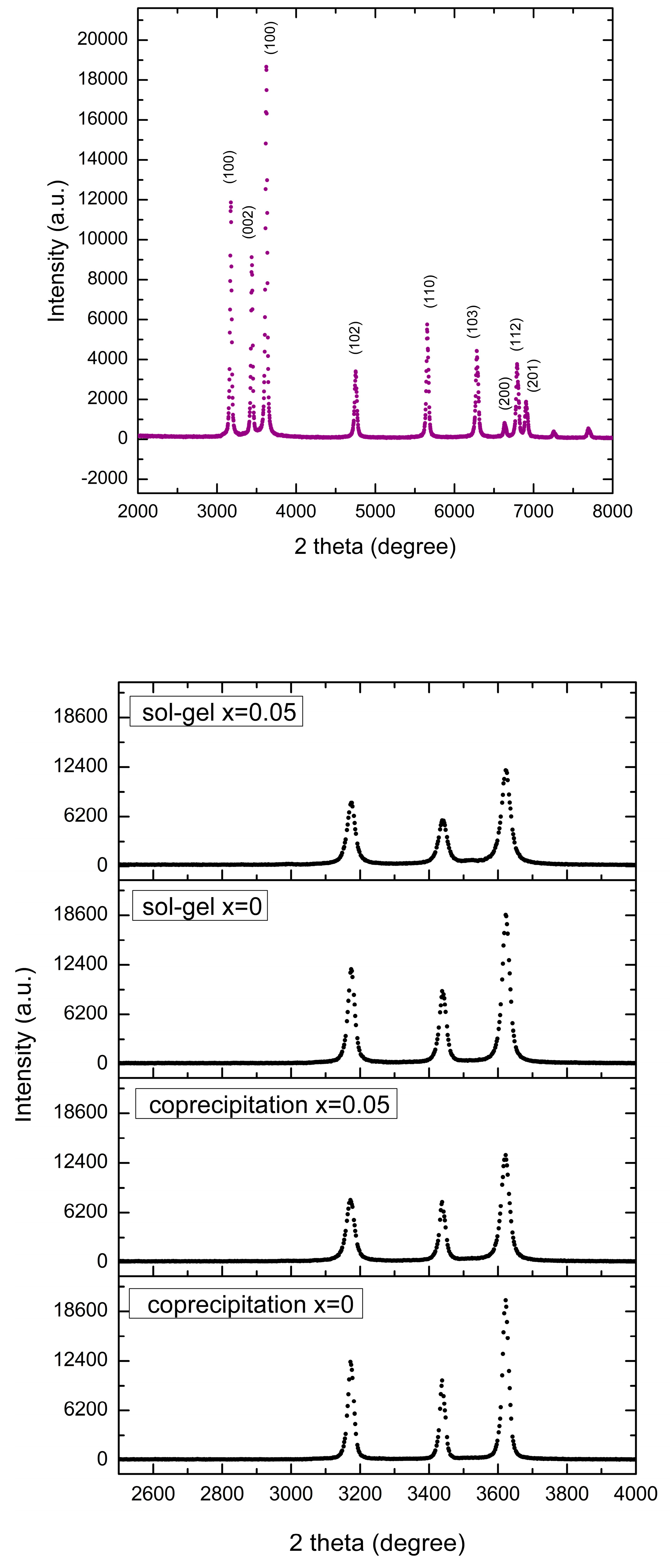

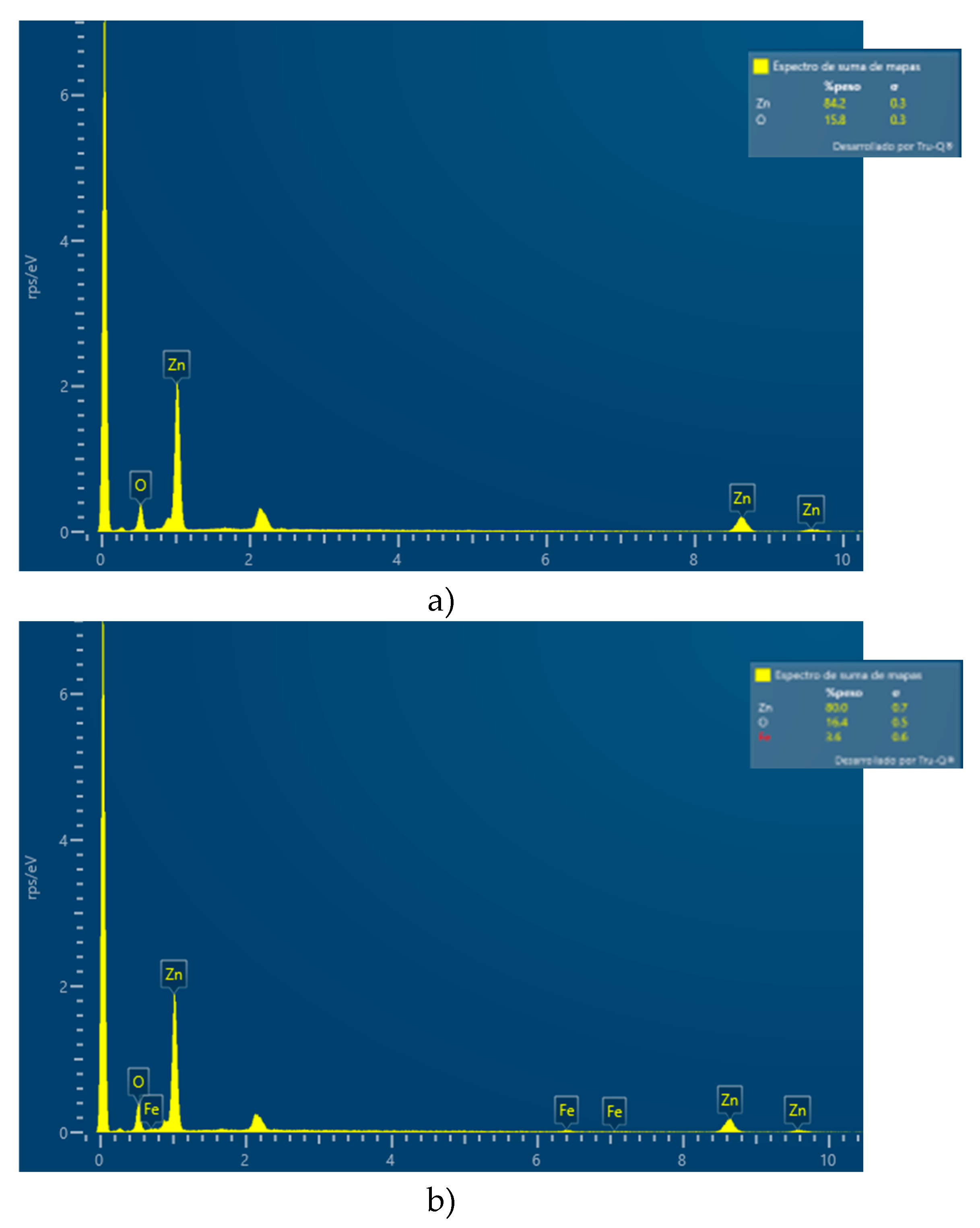

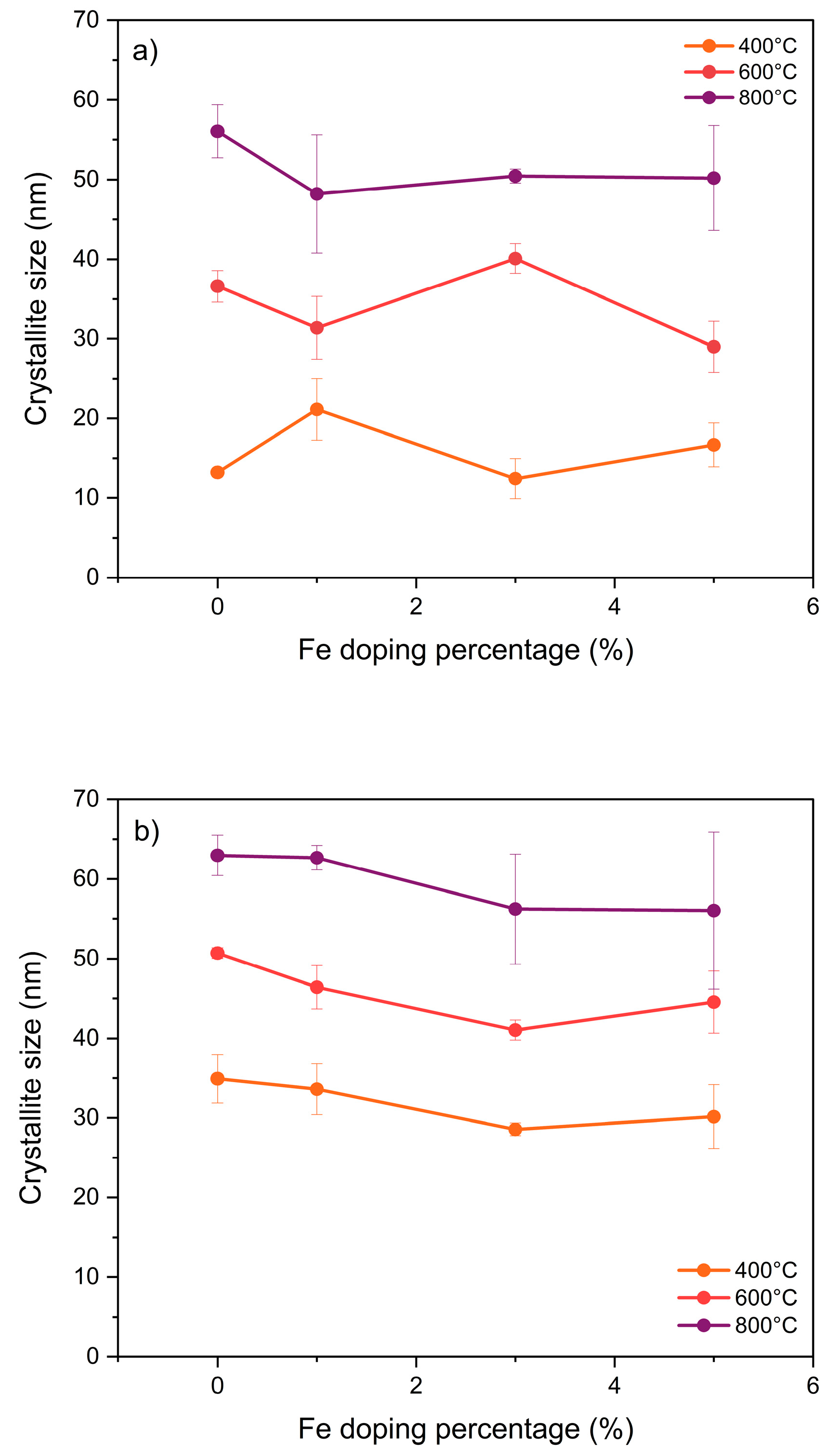

3.1. X-Ray Diffraction (DRX) and Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy (EDS)

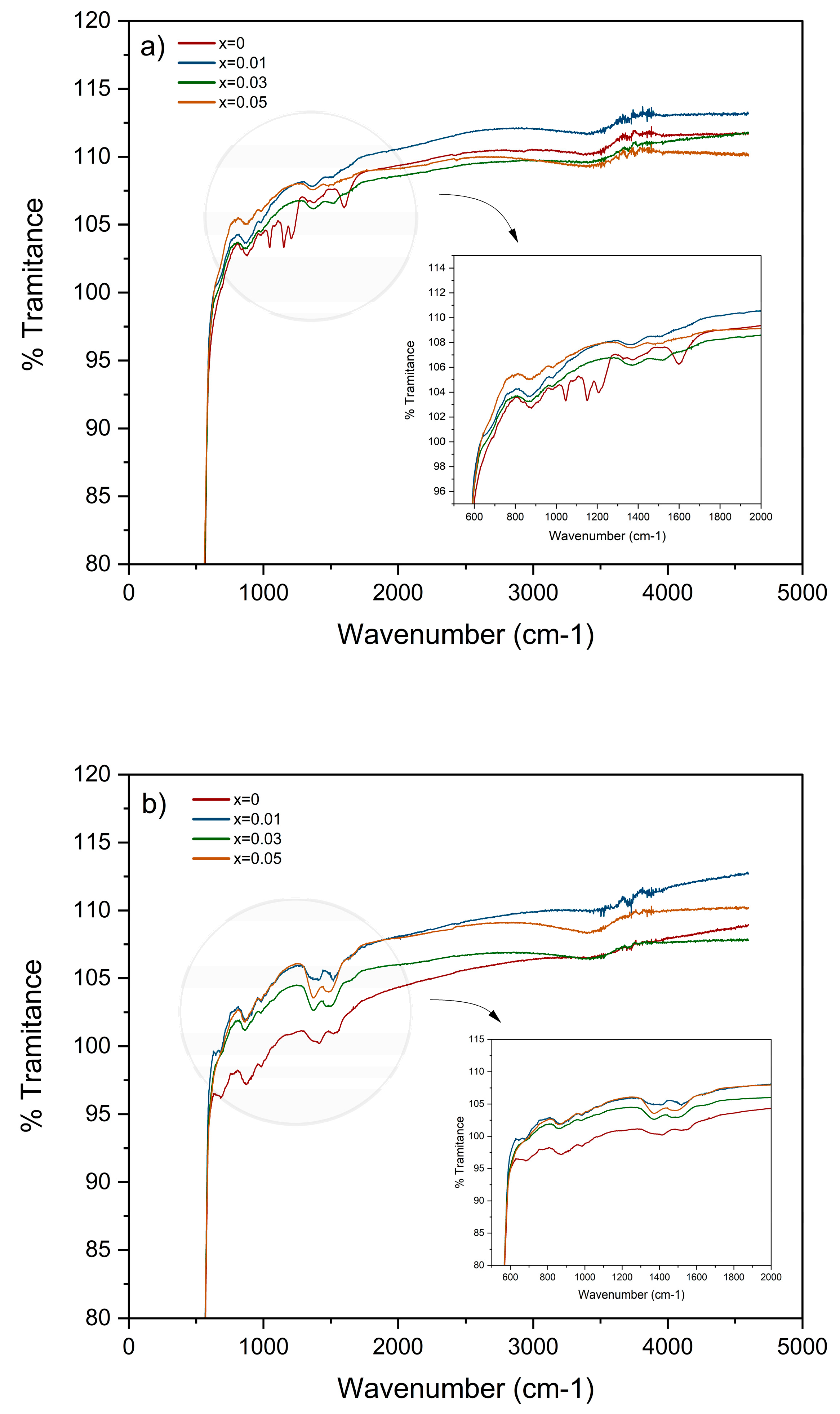

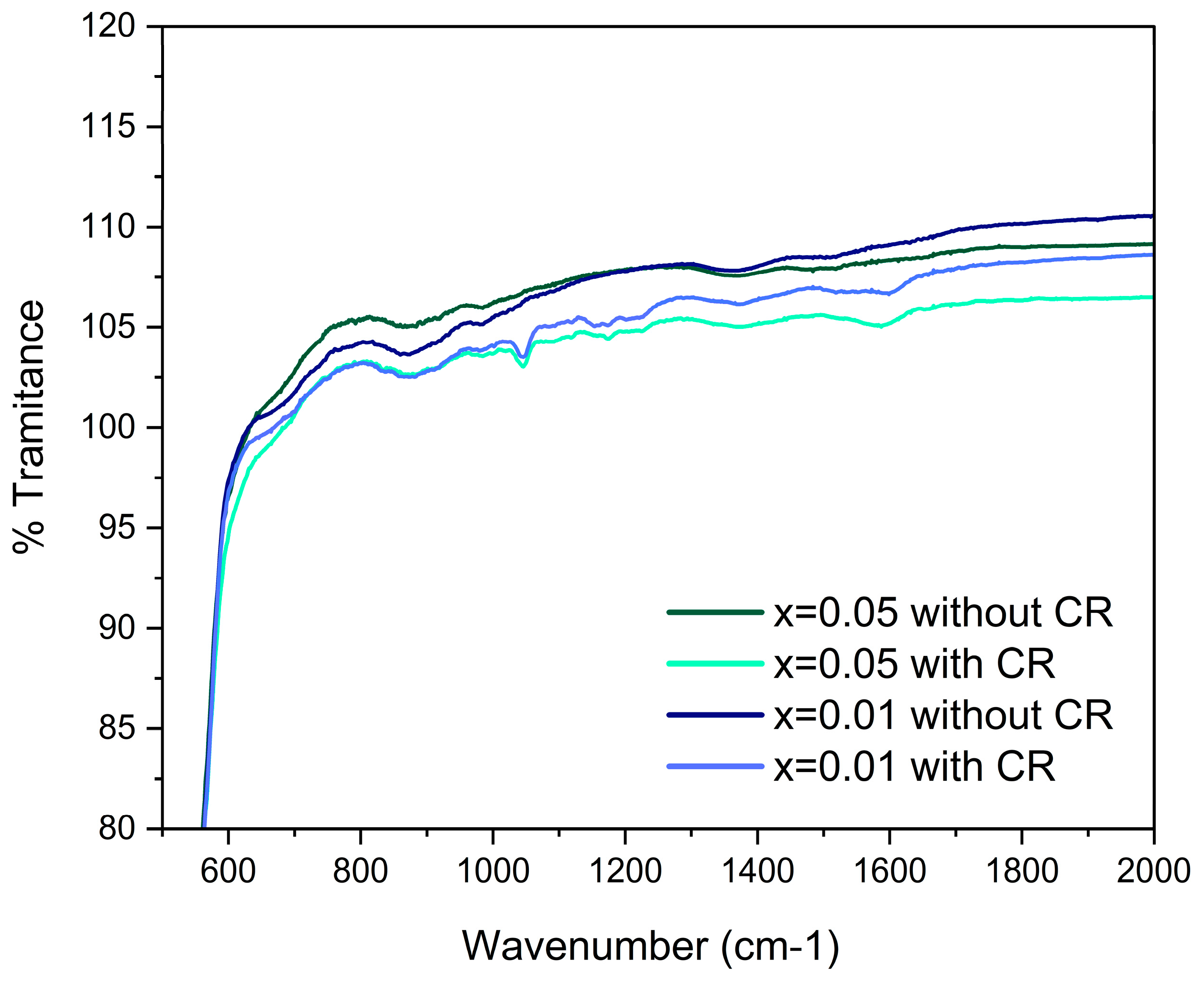

3.2. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

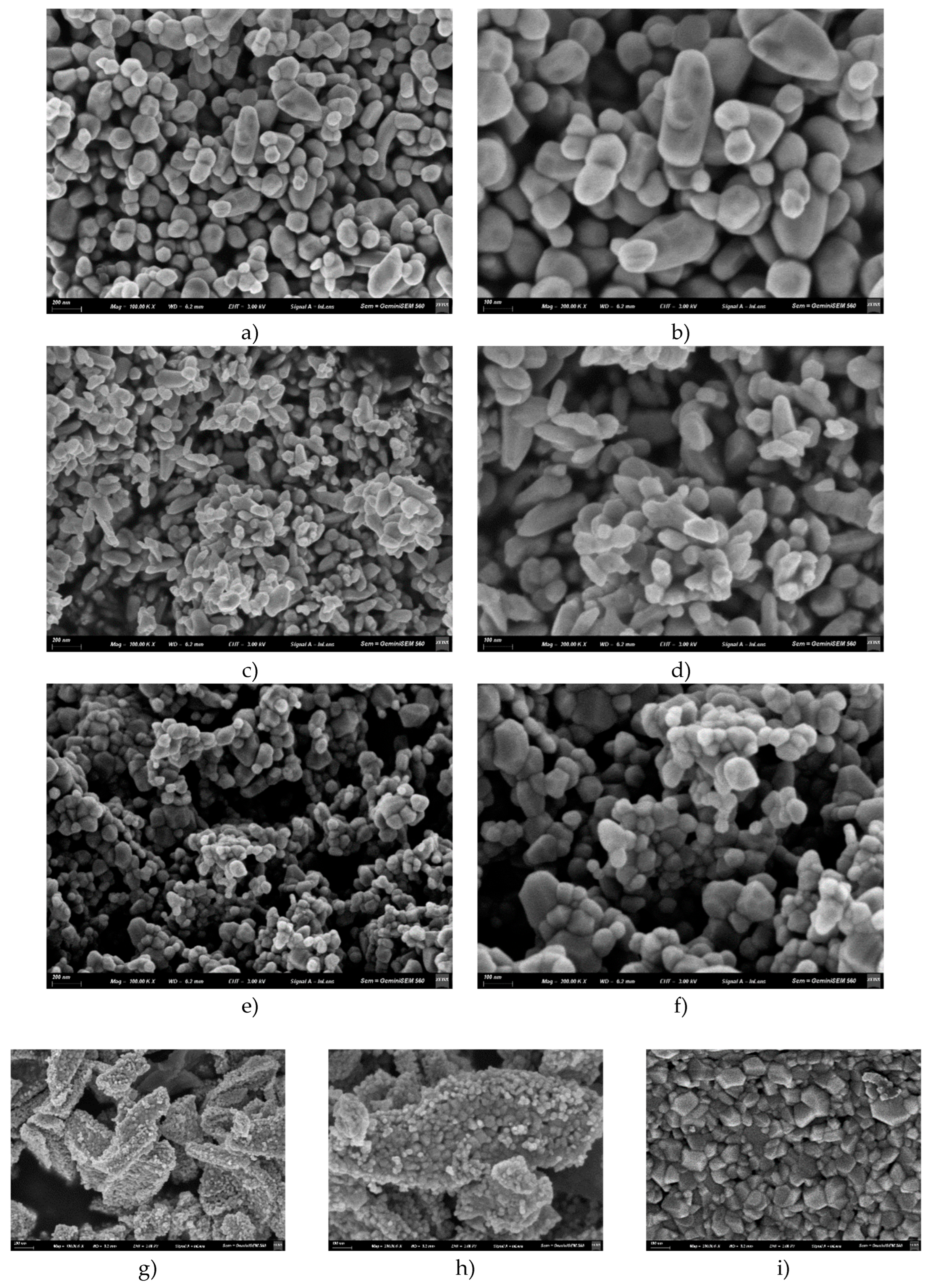

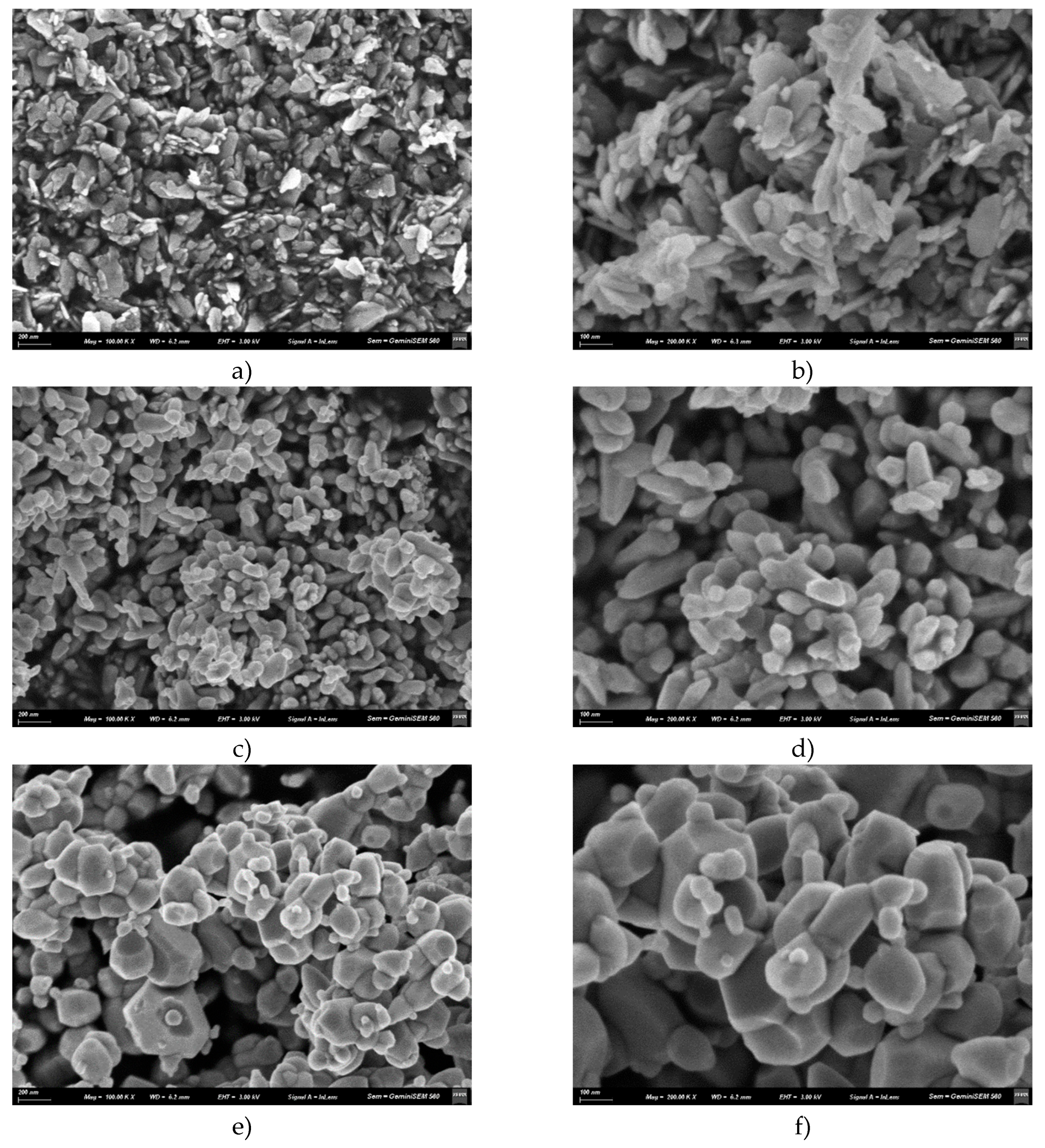

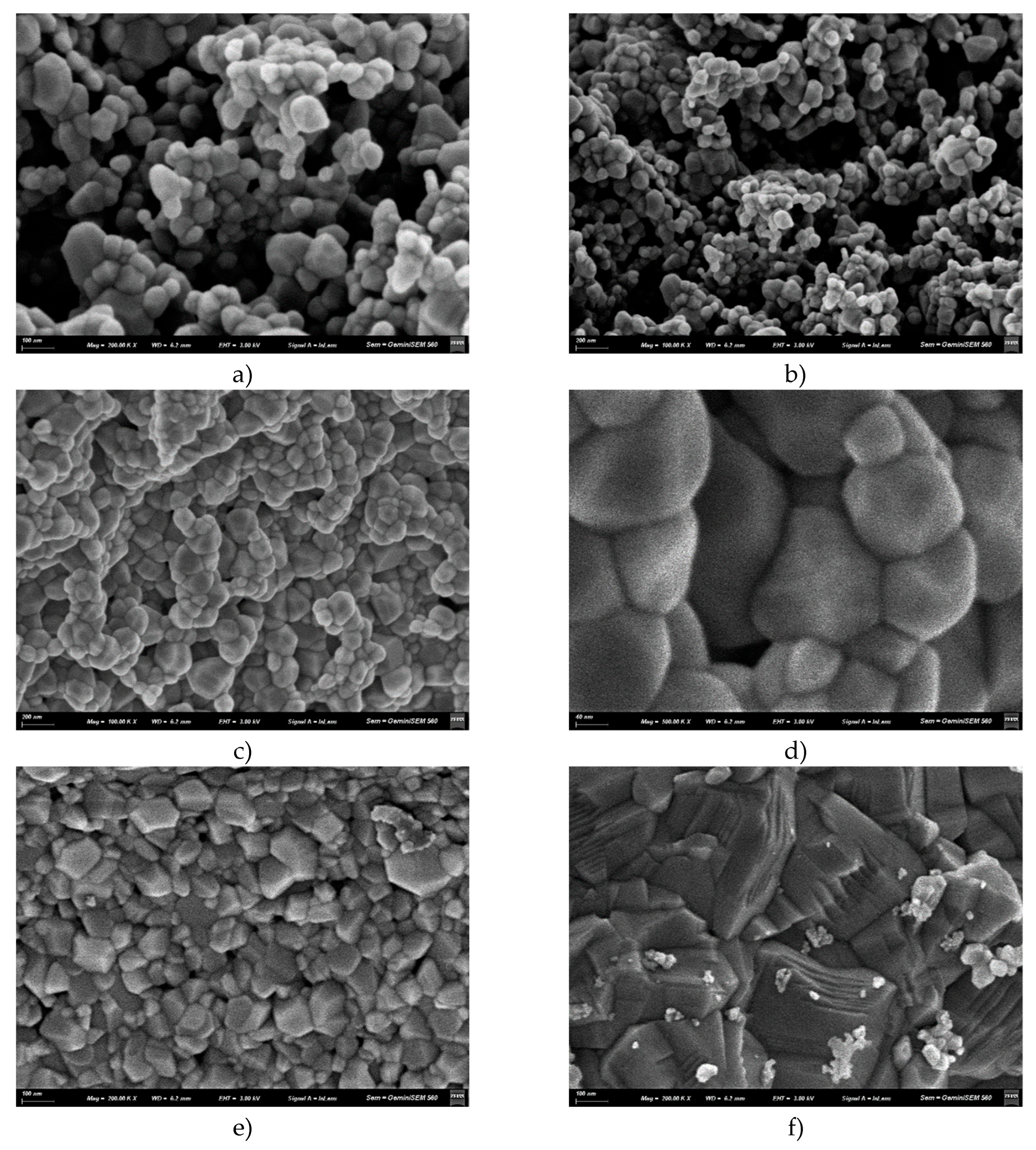

3.3. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

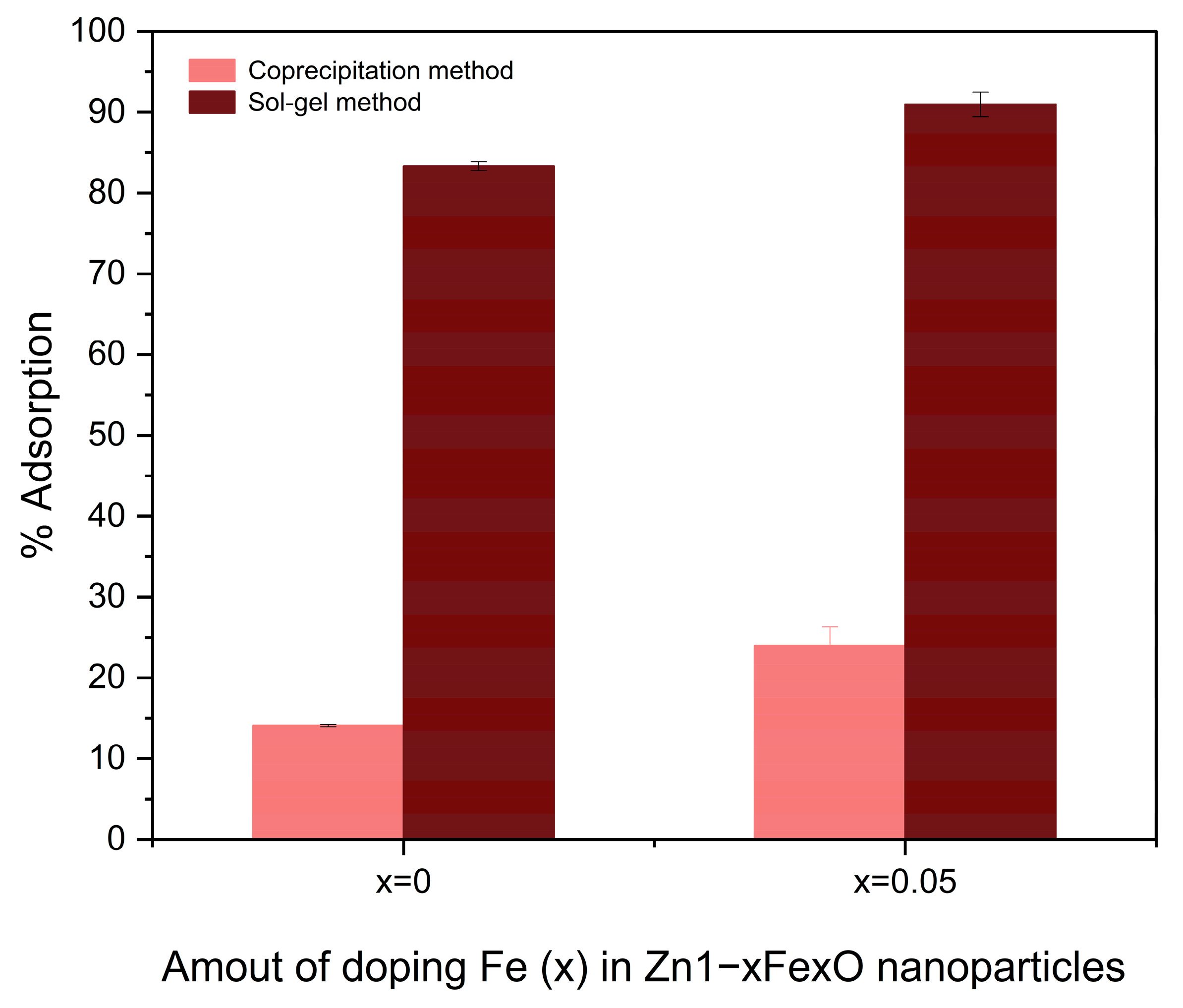

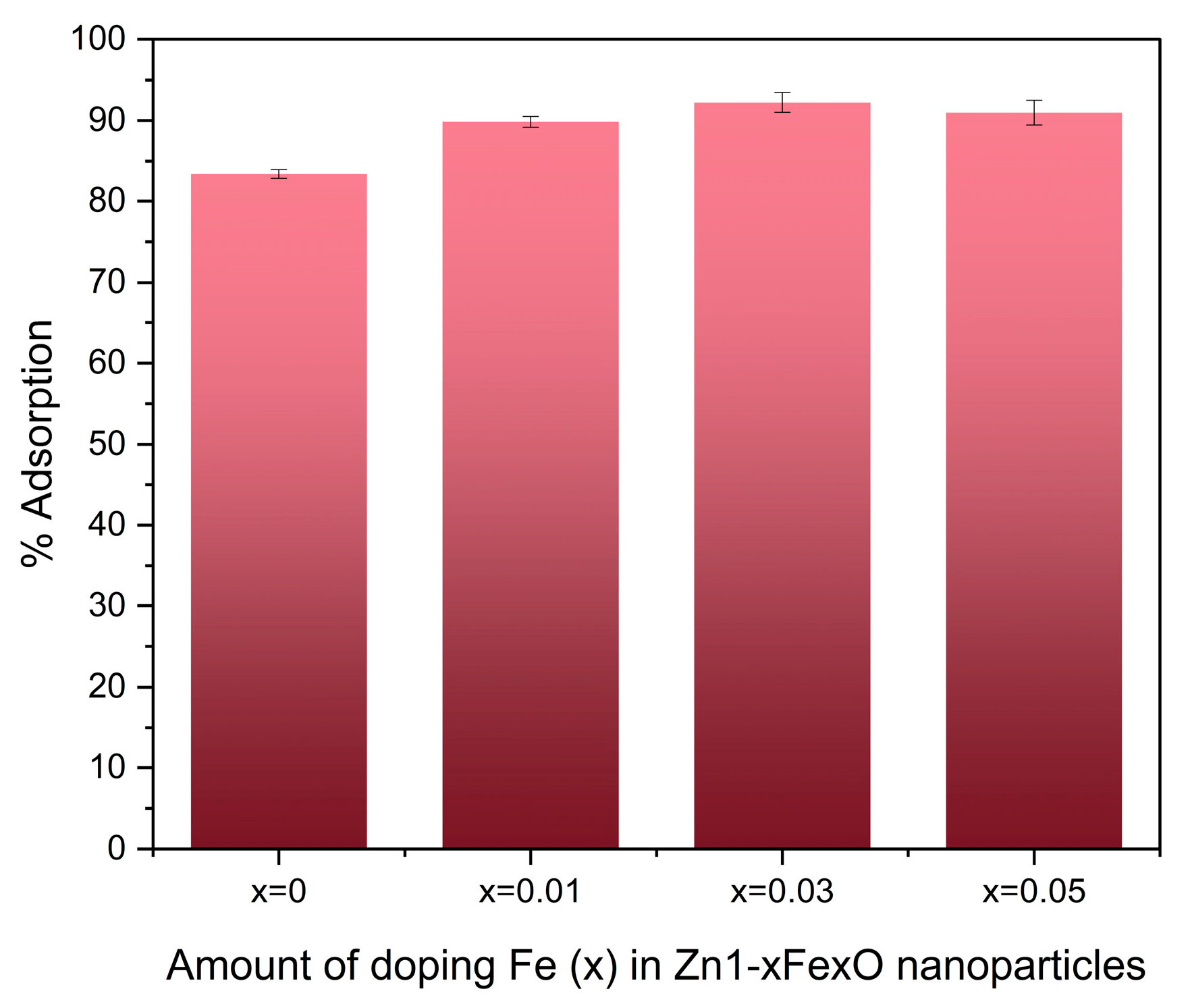

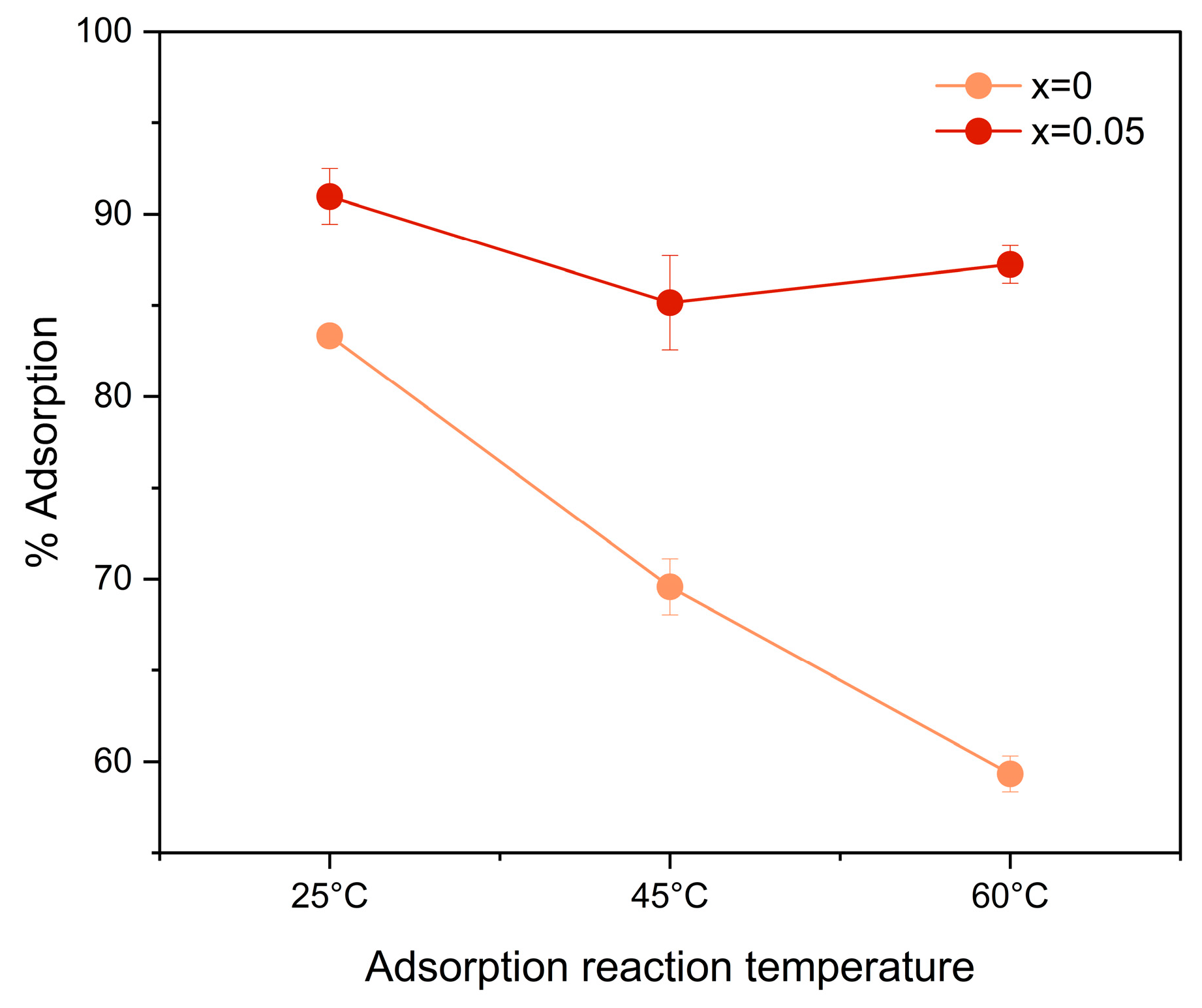

3.4. Adsorption Assays

4. Discussion

4.1. X-Ray Diffraction (DRX) and Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy (EDS)

4.2. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

4.3. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

4.4. Adsorption Assays

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wahab, R.; Mishra, A. Antibacterial activity of ZnO nanoparticles prepared via non-hydrolytic solution route. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 87, 1917–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, V.; Gusain, D. Synthesis, characterization and application of zinc oxide nanoparticles (n-ZnO). Ceram. Int. 2013, 39, 9803–9808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-C.; Tang, C.-T. Preparation and application of granular ZnO/Al₂O₃ catalyst for the removal of hazardous trichloroethylene. J. Hazard. Mater. 2007, 142, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iandolo, B.; Hagfeldt, A. Zinc Oxide Nanostructures for Water Treatment: Synthesis, Properties and Applications. Crystals 2024, 14, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, N.B.; Saeed, F.R. Synthesis and characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles via oxalate co-precipitation method. Mater. Lett. X 2022, 13, 100126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carofiglio, M.; Barui, S. Doped Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Characterization and Potential Use in Nanomedicine. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 5194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, A.; Khan, Z. M. Formation and characterization of ZnO nanopowder synthesized by sol–gel method. J. Alloys Compd. 2010, 495, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kołodziejczak-Radzimska, A.; Jesionowski, T. Zinc Oxide—From Synthesis to Application: A Review. Materials 2014, 7, 2833–2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiee, P.; Reisi Nafchi, M. Sol-gel zinc oxide nanoparticles: advances in synthesis and applications. Synthesis and Sintering 2021, 1, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S.; Ayon, S. A. Comparative study of structural, optical, and photocatalytic properties of ZnO synthesized by chemical coprecipitation and modified sol–gel methods. Surf. Interface Anal. 2023, 55, 424–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Khan, S. Temperature-dependent dielectric and magnetic properties of Mn-doped zinc oxide nanoparticles. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2014, 26, 516–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Droepenu, E.K.; Wee, B.S. Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Synthesis Methods and its Effect on Morphology: A Review. Biointerface Research in Applied Chemistry 2022, 12, 4261–4292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, S.; Pokhrel, S. Use of a Rapid Cytotoxicity Screening Approach To Engineer a Safer Zinc Oxide Nanoparticle for Nanomedicine. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, T.; Perlstein, B. Synthesis and characterization of zinc/iron oxide composite nanoparticles and their antibacterial properties. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2011, 374, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrán, J. J.; Barrero, C. A. Understanding the role of iron in the magnetism of Fe doped ZnO nanoparticles. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 15284–15296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahato, T.H.; Prasad, G.K. Nanocrystalline zinc oxide for the decontamination of sarin. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 165, 928–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Arjan, W.S. Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles and Their Application in Adsorption of Toxic Dye from Aqueous Solution. Polymers 2022, 14, 3086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, A.B.; Blandino, A. Modelling of different enzyme productions by solid-state fermentation on several agro-industrial residues. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 9555–9566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attallah, M.F.; Ahmed, I.M. Treatment of industrial wastewater containing Congo Red and Naphthol Green B using low-cost adsorbent. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013, 20, 1106–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharbani, P.; Tabatabaii, S.M. Removal of Congo red from textile wastewater by ozonation. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 5, 495–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attallah, M.F.; Ahmed, I.M. Treatment of industrial wastewater containing Congo Red and Naphthol Green B using low-cost adsorbent. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013, 20, 1106–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labille, J.; Brant, J. Stability of nanoparticles in water. Nanomed. 2010, 5, 985–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachin; Pramanik, B. K.; Singh, N. Fast and Effective Removal of Congo Red by Doped ZnO Nanoparticles. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samanta, A.; Chattopadhyay, S. Structural, optical and magnetic properties of Fe-doped ZnO nanoparticles. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2020, 239, 122180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanchana, S.; Chithra, M.J. Violet emission from Fe doped ZnO nanoparticles synthesized by precipitation method. J. Lumin. 2016, 176, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Sarkar, R. Synthesis, characterization and tribological study of zinc oxide nanoparticles. Mater. Today: Proc. 2021, 44, 3606–3612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, N. Adsorption of Congo red dye on FeₓCo₃₋ₓO₄ nanoparticles. J. Environ. Manage. 2019, 238, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Şişmanoğlu, T.; Pozan, G.S. Adsorption of Congo red from aqueous solution using various TiO₂ nanoparticles. Desal. Water Treat. 2016, 57, 13318–13333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshini, B.; Patra, T. An efficient and comparative adsorption of Congo Red and Trypan Blue dyes on MgO nanoparticles: Kinetics, thermodynamics and isotherm studies. J. Magnesium Alloys 2021, 9, 478–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahab, R.; Mishra, A. Antibacterial activity of ZnO nanoparticles prepared via non-hydrolytic solution route. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 87, 1917–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swapna, P.; Venkatramana Reddy, S. Structural, optical & magnetic properties of (Fe, Al) co-doped zinc oxide nanoparticles. Nanoscale Reports 2019, 2, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Sarkar, R. Synthesis, characterization and tribological study of zinc oxide nanoparticles. Mater. Today: Proc. 2021, 44, 3606–3612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouzaia, F.; Djouadi, D. Particularities of pure and Al-doped ZnO nanostructures aerogels elaborated in supercritical isopropanol. Arab J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2020, 27, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faramawy, A.M.; Agami, W.R. Tailoring the preparation, microstructure, FTIR, optical properties and photocatalysis of (Fe/Co) co-doped ZnO nanoparticles (Zn₀.₉FeₓCo₀.₁₋ₓO). Ceramics 2025, 8, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachin; Pramanik, B. K.; Singh, N. Fast and effective removal of Congo red by doped ZnO nanoparticles. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Yin, W. Efficient removal of Congo red, methylene blue and Pb(II) by hydrochar–MgAlLDH nanocomposite: Synthesis, performance and mechanism. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, F.; Wang, D. Enhanced adsorption of Congo red using chitin suspension after sonoenzymolysis. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020, 70, 105327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuli, G.; Eisenmann, T. Structural and Electrochemical Characterization of Zn₁₋ₓFeₓO—Effect of Aliovalent Doping on the Li⁺ Storage Mechanism. Materials 2018, 11, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Wei, Z. Optical and magnetic properties of Fe-doped ZnO nanoparticles obtained by hydrothermal synthesis. J. Nanomater. 2014, 792102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellerbrock, R.H.; Stein, M. Comparing silicon mineral species of different crystallinity using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Front. Environ. Chem. 2024, 5, 1462678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irede, E.L.; Awoyemi, R.F. Cutting-edge developments in zinc oxide nanoparticles: synthesis and applications for enhanced antimicrobial and UV protection in healthcare solutions. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 20992–21034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.; Bukhari, H. Synthesis of nanosize zinc oxide through aqueous sol-gel route in polyol medium. BMC Chem. 2022, 16, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahai, A.; Kumar, Y. Doping concentration driven morphological evolution of Fe-doped ZnO nanostructures. J. Appl. Phys. 2014, 116, 164315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavan, K. B.; Mohite, S. V. Studies on effect of Fe doping on ZnO nanoparticles microstructural features using x-ray diffraction technique. Phys. Scr. 2025, 100, 065904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elkader, O. H.; Nasrallah, M. Biosynthesis, Optical and Magnetic Properties of Fe-Doped ZnO/C Nanoparticles. Surfaces 2023, 6, 410–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, J. E.; Montero-Muñoz, M. Evidence of a cluster glass-like behavior in Fe-doped ZnO nanoparticles. J. Appl. Phys. 2014, 115, 17E123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokesha, H.S.; Mohanty, P. Structure, optical and magnetic properties of Fe-doped, Fe + Cr co-doped ZnO nanoparticles. arXiv arXiv:2111.07266, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Kosmulski, M. The pH dependent surface charging and points of zero charge. IX. Update. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 296, 102519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schelonka, D.; Tolasz, J. Doping of Zinc Oxide with Selected First Row Transition Metals for Photocatalytic Applications. Photochem. Photobiol. 2015, 91, 1071–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baig, N.; Kammakakam, I. Nanomaterials: a review of synthesis methods, properties, recent progress, and challenges. Mater. Adv. 2021, 2, 1821–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, S. A.; Taha, G. M. Three different methods for ZnO-RGO nanocomposite synthesis and its adsorption capacity for methylene blue dye removal in a comparative study. BMC Chem. 2025, 19, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, Y. B. S.; Parajuli, D. Effect of Fe-doped and capping agent – Structural, optical, luminescence, and antibacterial activity of ZnO nanoparticles. Chem. Phys. Impact 2023, 7, 100270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Duan, Y. Adsorption and sensing performances of transition metal doped ZnO monolayer for CO and NO: A DFT study. SSRN 2024, 26, 4958262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muedi, K.L.; Masindi, V. Effective adsorption of Congo Red from aqueous solution using Fe/Al di-metal nanostructured composite synthesised from Fe(III) and Al(III) recovered from real acid mine drainage. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekele, E.A.; Korsa, H.A. Electrolytic synthesis of γ-Al₂O₃ nanoparticle from aluminum scrap for enhanced methylene blue adsorption: experimental and RSM modeling. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 16957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majani, S.S.; Manoj; Lavanya, M. Nano-catalytic behavior of CeO₂ nanoparticles in dye adsorption: Synthesis through bio-combustion and assessment of UV-light-driven photo-adsorption of indigo carmine dye. Heliyon 2024, 10, e35505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şişmanoğlu, T.; Pozan, G.S. Adsorption of Congo Red from aqueous solution using various TiO₂ nanoparticles. Desalination Water Treat. 2016, 57, 13318–13333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

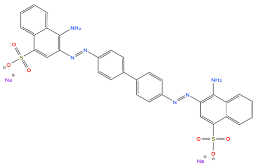

| Characteristic | |

| Generic name | Congo Red |

| Molecular weight | 696,66 g/mol |

| Chemical formula | C32H22N6Na2O6S2 |

| Maximum wavelength (λmax) | 500 nm |

| CAS number | 573-58-0 |

| Molecular structure |  |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).