1. Introduction

Natural floodplains provide diverse aquatic, riparian, and wetland habitats. They also sustain a range of valuable ecosystem services that help manage the risks associated with floods, droughts, pollution, and wildfires (Hauer et al., 2016; Lawson et al., 2018; Pugh et al., 2022). Large numbers of streams have become partially or entirely disconnected from their floodplains due to channelisation, artificial levee building and/or anthropogenically-triggered channel incision (Cluer and Thorne, 2014; Brown et al., 2018; Wohl et al., 2021). In response, river restoration has become central to modern river and flood risk management and engineering (Bridges et al., 2018; Piégay et al. 2020; Carter and Lipiec, 2020; Lashford et al., 2022). Many streams that have been physically or biologically degraded by past management and engineering lack the capacity to recover naturally. The premise underpinning river restoration is it is possible to recover lost forms, functions and species by re-instating the necessary hydrologic, geomorphic and biomic processes (Downs and Gregory, 2014; Geist and Hawkins, 2016; Johnson et al., 2019; Modi et al., 2022).

Early restoration approaches concentrated on in-channel measures (Bernhardt and Palmer 2011; Beechie et al. 2013; Booth et al. 2016). In the last decade, the focus has shifted to measures that restore the floodplain as well (Powers et al. 2019, 2022). Returning a stream to its pre-disturbance condition by fully-reconnecting an anthropogenically-incised channel to its historical floodplain is Stage 0 in the Stream Evolution Model proposed by Cluer and Thorne (2014). Projects that reconnect channels to their historical floodplains are widely referred to as ‘Stage 0 restoration’ (

http://stagezeroriverrestoration.com/).

It is important to note that Stage 0 is a restoration target, not a method. Stage 0 can be achieved using two different approaches. The first is by filling in the incised channel and ‘resetting’ the valley floor using heavy machinery. The second is or initiating stream evolution to Stage 0 using low-impact technology, process-based approaches and reintroduction of beavers (Pollock et al., 2014; Wheaton et al., 2019; Behan et al., 2020, Ciotti et al., 2021).

Full hydrologic, geomorphic, and biologic connectivity between the stream and its historical floodplain is a key feature of Stage 0 restoration. This includes rehydration of both the floodplain and the hyporheic, alluvial aquifer beneath it. The resulting river planform is often multi-channeled (i.e., anabranching or anastomosed), though in headwater basins and meadows there may be a single channel or no channel at all (Pollock et al., 2014).

Prior to anthropogenic disturbance, Stage 0 conditions in the floodplains along many rivers featured extensive riparian zones and wetlands, with typical streams best described as ‘riparian-wetland corridors’ (Wohl et al., 2021). Riparian and wetland vegetation are important because they provide valuable ecological goods and services. Species-rich, structurally diverse riparian and wetland vegetation distributed across hydrologically connected floodplains provide wildlife habitat, support biodiversity, stabilize streambanks, sequester carbon, provide shade to maintain water temperature , provide resilience to climate disturbances such as drought, and, over time, contribute in-stream and floodplain wood (Riis et al., 2020, Hinshaw and Wohl, 2021, Glassic et al., 2025; McCabe et al., 2025; Pollock and Norman, 2025).

However, riparian zones now cover only 0.5–1% of the global land area (Mohan et al. 2022). The global area of riparian vegetation prior to significant human impacts is unknown because there are no reliable measurements, but detailed accounts like those of the pioneering ecologists indicate it was extensive (von Humboldt and Bonpland, 1807). About 80% of riparian habitats in Europe have disappeared since the 18th century (Naiman et al., 1993) and more than 90% of riparian habitats in the United States are considered degraded (Graziano et al. 2022). Loss and degradation of riparian habitat is a global issue, not just in North America and Europe (Li et al., 2024). Wet meadow ecosystems were previously abundant across the world but now occupy <1% of alluvial valley floors in most watersheds (Pollock and Norman, 2025).

Wetlands are also in decline. It is estimated that wetlands once covered ~16 million km2 of the Earth’s land surface (Fluet-Chouinard et al. 2023). This area has diminished during the Anthropocene with recent estimates of wetland loss varying between 21% and 87% (Fluet-Chouinard et al., 2023). Worldwide destruction of wetlands has led to dramatic losses of previously undervalued wetland-related functions, biodiversity, and ecosystem services (Finlayson et al., 2005, Maltby and Acreman, 2011). Although wetlands are now being restored in many areas, net loss is likely to continue due to climate change (Hardouin et al., 2024).

However, we are able to reverse historical and on-going losses of riparian habitats and wetland functions through large-scale restoration projects. But unfortunately, the results of early, channel-centric stream restoration have been disappointing (e.g., Palmer et al., 2014). In contrast, reconnecting the channel to its floodplain and rehydrating both the floodplain and its alluvial aquifer (i.e., restoration to Stage 0) have long been hypothesized to lead to the recovery of lost wildlife habitats and refugia associated with healthy aquatic, riparian, floodplain, and wetland ecosystems (Moreno-Mateous et al., 2012). Hard evidence to support this hypothesis is limited (Flitcroft et al., 2022). To address this hypothesis, this project assesses riparian vegetation and wetland functions data gathered to evaluate the initial outcomes of Stage 0 restoration of two anthropogenically-incised reaches of Whychus Creek within the Deschutes Land Trust’s ‘Whychus Canyon Preserve’, downstream of the town of Sisters, Oregon, US.

The aim of our study was to assess the initial performance of full floodplain reconnection in increasing the extent and diversity of riparian vegetation, and enhancing wetland functions, two and six years after project completion. Specific objectives were to:

use statistical analyses of data gathered along multiple transects in ‘Canyon Reach 4’ to compare vegetation present in 2018 to that observed prior to restoration, in 2016;

use a riparian and wetland functions assessment method to compare ecosystem services provided by ‘Canyon Reach 4’ in 2018 to those collected in the adjacent, unrestored ‘Canyon Reach 3’;

compare observations made in 2018 in ‘Canyon Reach 4’ (two-years post-restoration) with those made that year at ‘Camp Polk Meadow’ (six-years post-restoration), to gauge the potential for further development of vegetation in the more recently restored reach and make recommendations for further adaptive management, and

consider the implications of our findings for restoration research, monitoring and restorative actions along Whychus Creek and more generally.

2. Whychus Creek, Oregon: Historical Degradation and Recent Restoration

Our study was conducted on Whychus Creek, a tributary of the Upper Deschutes River in central Oregon, US. This creek rises at the base of the Bend Glacier on Broken Top Mountain, passing through the subalpine Three Sisters Wilderness Area and the City of Sisters before entering Whychus Canyon and then confluencing with the Deschutes River (

Figure 1).

Whychus Creek’s ~660 km

2 drainage basin is located in the rain shadow east of the Cascade Mountains. Consequently, average annual precipitation is only ~360 mm (UDWC, 2009). Base flow is sourced primarily from springs and glacial meltwater. Of the 65 km length of the creek, 25 km is designated as either ‘wild’ or ‘scenic’ and only the short reach within Sisters is urban (US Fish and Wildlife Service, n.d.a). Land ownership within the watershed is a mixture of public (mostly US Forest Service), and private property (including the Deschutes Land Trust) (see,

Figure 1, above).

During the late-19th century and 20th century, extensive reaches of Whychus Creek and its floodplain were manipulated by European and US settlers to support homesteading, farming and ranching. Management actions included channelisation, embanking, straightening, and relocating the Creek to a position along the edge of the valley floor (UDWC n.d. a; b). By the 1970s, these actions had resulted in channel incision that severed the channel’s lateral connection to its floodplain. As a result, resident fish populations (including redband trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) and bull trout (Salvelinus confluentus) declined, and the floodplains were no longer able support the extensive riparian and wetland ecosystems known to be present until the 1940s (UDWC n.d. a, Buijse et al. 2002, Beechie et al. 2010). This environmental degradation, coupled with three hydropower dams on the Deschutes River downstream of the Whychus Creek confluence that were constructed with no provision for volitional fish passage, wiped out Whychus Creek’s populations of anadromous salmon (USFS 1998).

Deschutes Land Trust’s ‘Whychus Canyon Preserve’ includes a 9.7 km stretch of Whychus Creek, divided into 6, 1.6 km (1 mile) reaches and numbered 1-6 from upstream to downstream. We focus on ‘Canyon Reach 4’, which was restored in 2016. The aim was to reactivate natural fluvial processes and encourage development of a multi-channel (i.e., anastomosing) planform with frequent flow switching between anabranches and active meandering. The goal of the restoration was to establish heterogenous and resilient instream, wetland, pond, and floodplain habitats capable of supporting a diverse range of plant and animal species. This included suitable habitat for salmon transferred upstream of the dams on the Deschutes River through a ‘trap-and-haul’ programme and hatchery fish released within Whychus Creek itself (Perle et al., 2018).

The restoration project was designed using the Geomorphic Grade Line and Relative Elevation Model approach developed by the US Forest Service (Powers et al., 2019). The artificially straightened, relocated, and incised channel was filled in with material obtained by lowering a high terrace that was a legacy of anthropogenically-triggered incision during the early 20th century (

Figure 2a).

In areas where the high terrace was lowered, large wood and sedge mats were used to roughen the excavated surface and encourage the natural development of multiple flow paths and anabranches (Perle et al. 2018). Reconnecting the stream to its floodplain at base flow and re-wetting relict anabranches still present in the surface of a lower terrace created an anastomosed planform for the creek, similar to that prior to Anthropogenic disturbance (

Figure 2b).

In-filling the incised channel rehydrated the alluvial aquifer beneath the floodplain. Within days of work completing, the water table rose from ~2 m below the floodplain to ~30 cm. The water table then remained high, its depth below ground fluctuating seasonally between 30 and 50 cm (Mork et al., 2018). Geomorphological restoration was accompanied with extensive and diverse planting, predominantly with native riparian and wetland species but also including upland species on the more elevated parts of the restored floodplains (for details, see

Supplementary Materials A).

Post-project monitoring of the physical environment in ‘Canyon Reach 4’ demonstrated that by 2018, in-stream and floodplain conditions had evolved from a static, single-thread channel constrained by high and low terraces that were hydrologically and geomorphically disconnected, to a dynamic, multi-channel system fully connected to its floodplain (

Figure 3).

Prior to restoration in 2016, vegetation in ‘Canyon Reach 4’ was surveyed and we resurveyed the reach again in 2018. Detailed observations of changes in the plant community composition and the provision of ecosystem services were also made. We report, analyze and interpret the results of the 2015 and 2018 vegetation surveys in the remainder of this paper.

The results for ‘Canyon Reach 4’ are also compared to those gathered in 2018 at:

3. Vegetation Study Reaches and Methods

3.1. Study Reaches

Sampling was performed within three study reaches of Whychus Creek:

‘Camp Polk Meadow Preserve’, where 2.4 km of the valley floor was restored using a modified Natural Channel Design between 2009 and 2012. The uppermost 550 m of the meadow has since naturally developed a multi-channel, river-wetland corridor that resembles a Stage 0 condition. Throughout this paper, we refer to this study reach as being ‘restored’ (

Figure 4a);

‘Whychus Canyon Reach 3’, which is unrestored and represents the pre-restoration condition of degraded and simplified stream habitat along Whychus Creek. We refer to this reach as being the ‘control’ (

Figure 4b); and

‘Whychus Canyon Reach 4’, where 1.5 km of the valley floor was restored to its Stage 0 condition in summer 2016. We refer to this reach as being in ‘transition’ (

Figure 4c).

3.2. Vegetation Transects

In summer 2015, pre-restoration vegetation data were collected along the four transects in ‘Canyon Reach 4’ shown in white in

Figure 4c (above). These transects were resurveyed in August 2018 to enable comparison between pre- and post-restoration vegetation characteristics. Because the transects were established in 2015, prior to selection of the plant community focal study sub-areas in 2018, their locations are unrelated to those sub-areas. In August 2018, we also set up and surveyed four, comparable transects within the study area of ‘Camp Polk Meadow’ (

Figure 4a, above). No transects were set up in ‘Canyon Reach 3’ because there had been no discernible changes in the vegetation in this, the unrestored, control reach (see

Figure 4b, above).

To sample vegetation along each transect, a pin was lowered on the upstream side of the tape at 1.2 m (4 ft) intervals. Species and height data for all the plants touched by the pin were recorded on custom datasheets. Living plants were recorded to species level and dead plants were recorded as litter unless they could be positively identified. For example, although the standing cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum) had died by the time of our field campaign (in August), it was easily identified and so was classified to species.

As all transects are valley-wide, their lengths differ. Sample points were uniformly spaced at 1.2 m intervals, so the percentage of the transect represented by each sample point differ between transects. To account for this in the results, the number of points along a transect where a particular plant species was encountered was converted to a percentage of the total number of points along that transect. The maximum percent cover for an individual species is 100%. However, because multiple species were often recorded at a single sample point, the total percent cover for all species at a transect is likely to exceed 100%.

In addition to collecting data on the plants encountered at each sample point, we also observed the composition of the ground surface (i.e., bare earth, sand, gravel, large wood, or litter (i.e., the undecomposed remains of dead vegetation)), and again converted the absolute numbers of surface-type observations along each transect, into percentages.

3.3. Plant Community Focal Study Areas

In August 2018, we established focal plant community study areas within the all study reaches. Single, 500 m long study areas were established at ‘Canyon Reach 3’ and ‘Camp Polk Meadow’. At ‘Camp Polk Meadow’, the study area was later extended downstream by 50 m, to capture the full extent of Stage 0 conditions in the reach. To capture the habitat diversity apparent in the longer, 1.5 km of restored creek at ‘Canyon Reach 4’, we divided that study reach into 4 x 125m study sub-areas, distributed along its length. In

Figure 4 (above), the final study areas within each reach are outlined in red.

We conducted detailed floristic observations across the study areas, taking into account the riverscape settings of selected sample sites and paying particular attention to local geomorphological features and wildlife. We recorded all plant species observed in the study areas using botanical names taken from the USDA (2018) ‘PLANTS’ database (

https://plants.usda.gov/). Relative abundance estimates at the sampling points were recorded using the DAFOR scale (

Table 1). We added the prefix ‘L’ to relative abundance estimates when an observation applied locally rather than throughout the study area (e.g., ‘LF’ indicates that a species was ‘Locally Frequent’).

3.4. Wetland Functions Assessment

In 2018, wetland functions were assessed using polygons created within the study areas at all three study reaches. In ‘Canyon Reach 4’, eight wetland polygons were created by dividing each of the four study sub-areas into an upstream and downstream half. In ‘Canyon Reach 3’ and at ‘Camp Polk Meadow’, the single, large study areas were divided into four and six wetland polygons, respectively. In 2019, ‘Canyon Reaches 3’ and ‘4’ were re-assessed to test whether the field method was repeatable, evaluate whether wetland functions in the transition reach were continuing to change and determine whether they had further diverged from those in the control reach (Goss, 2019).

In assessing wetland functions, we used the ‘Guidebook for Hydrogeomorphic (HGM)-based Assessment of Oregon Wetland and Riparian Sites: Statewide Division and Profiles’ (Adamus and Field, 2001). This reference-based approach uses similar concepts to Washington Department of Ecology's ‘hydrogeomorphic methods’ (Hruby et al., 1999) and incorporates technical guidance provided by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (Smith et al., 1995). It involves estimating numerical scores for 13 wetland functions that are categorized depending whether their contributions to ecosystem services are ‘Population’, ‘Ecosystem’ or ‘Global’ (

Table 2).

For each wetland function, surveyors follow instructions for assessing and estimating raw scores for a set of reference-based indicators for that function; each raw score has been scaled and used in an equation to provide a function capacity score and standardized function capacity score. We selected this method because:

it provides a numeric score for functions,

is extensively referenced to technical literature and field data,

was developed for use in the State of Oregon, and

is less time-intensive than alternative methods.

4. Data Processing

All the information collected in the field was transcribed into Excel worksheets, and an extensive quality control and assurance review was performed to ensure all issues related to data recording and transcription were resolved.

For the vegetation communities observed, we assessed each plant’s indicator status, which is a measure of a plant's likelihood to occur in wetlands versus non-wetlands (Lichvar et al., 2012). We used five wetland indicator status ratings to determine whether a species is hydrophytic. These indicator status ratings are based on the attributes that:

Obligate Wetland (OBL) plants almost always occur in wetlands;

Facultative Wetland (FACW) plants usually occur in wetlands, but are occasionally found in uplands;

Facultative (FAC) plants occur in both wetlands and uplands;

Facultative Upland (FACU) plants usually occur in uplands, but may occur in wetlands;

Upland (UPL) plants almost always occur in uplands.

Following guidance first provided in U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (Lichvar et al. 2012), all species not listed on the national wetland plant list the were listed as upland plants (UPL).

Matlab scripts were compiled to plot the results and perform the statistical analyses. Paired t-tests and factor analysis were carried out using SPSS. When comparing study reaches, some data (e.g., transect biodiversity) were normalized to sum to 100%. Whether original or normalized data were used for each analysis is indicated in the resulting graphs. Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to compare the distributions of specific floristic variables and wetland function scores.

Finally, we applied comparative statistical analyses to the results of vegetation transect surveys at ‘Canyon Reach 4’ in 2015, ‘Canyon Reach 4’ in 2018, and ‘Camp Polk Meadow’ in 2018. In order to identify differences in vegetation assemblages, a 3-factor Principal Component Analysis (PCA) incorporating the Varimax with Kaiser Normalization Rotation Method, and calculations of Jaccard correlation coefficients and Sorensen similarity indices were completed. These enabled us to assess:

the impact of restoration of the transition ‘Canyon Reach 4’ in 2016, to ‘Stage Zero’; and

how plants at the restored ‘Camp Polk Reserve’ have, since restoration in 2012, been able to:

o

recover from the disturbances associated with channel-filling and floodplain reconnection, and

o

respond (through dereliction, adaptation, and/or succession) to the novel conditions experienced in the complex channels and rehydrated valley floors.

5. Results

5.1. Study Area Plant Communities

5.1.1. Overview

In total, 90 species of vascular plant were recorded in the focal study areas of Whychus Creek. For the full list of the plants recorded see

Supplementary Materials B. The plants observed include species from all five indicator status ratings (

Table 3).

The geomorphic characteristics and plant community attributes observed in the study areas of the three study reaches are summarized in the following sub-sections.

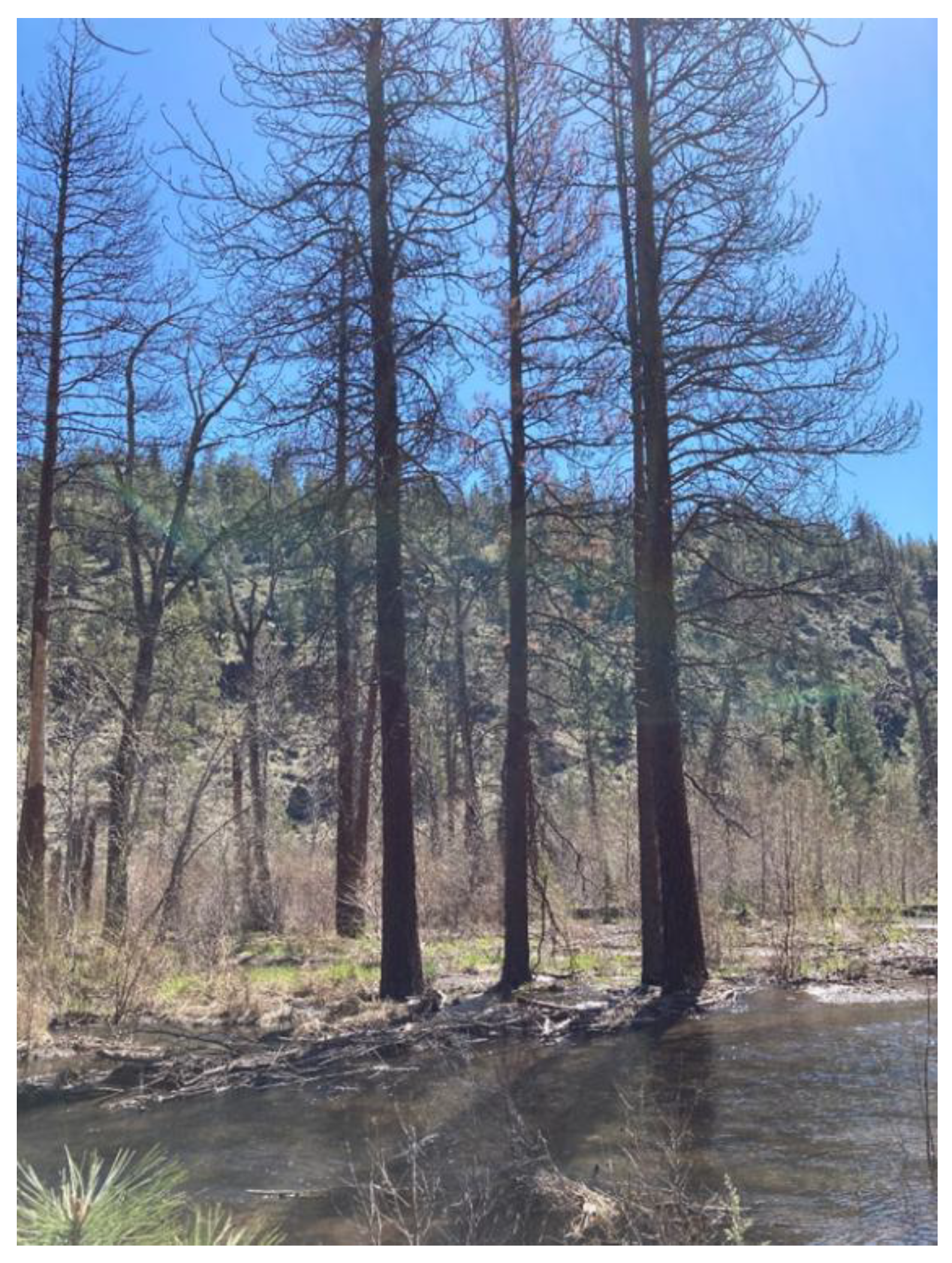

There was an inconsistency with this indicator series concerning Ponderosa pines (

Pinus ponderosa), which have the status Facultative Upland, meaning that they may occur in wetlands. Ponderosa pines grow across a 1,500 m range of elevations throughout the Cascades (Allen and Breshears 1998; Allen et al. 2002) and were observed in all three study reaches of Whychus Creek. However, while the mature ponderosa pines in ‘Canyon Reach 3’ were thriving, those at ‘Camp Polk Meadow’ and ‘Canyon Reach 4’ were either in poor health, dying, or dead (

Figure 5), which is inconsistent with their indicator status of Facultative Upland.

We attribute the deterioration of the ponderosa pines in Canyon Reach 4 and at Camp Polk to the rapidity with which water tables in those reaches rose following restoration. We conclude that the pine trees had insufficient time to adapt to the wetter conditions in the rehydrated floodplains despite their indicator status being Facultative Upland.

5.1.2. Whychus Canyon Reach 3 (Control)

The disconnected floodplain is around 3 m higher than the incised channel and, during the field study in August 2018, it was dominated by the invasive grass Bromus tectorum, which had senesced due to a long, antecedent, dry period. Two Upland shrubs, Ericameria nauseosa and Chrysothamnus viscidiflorus, were widely observed on the disconnected floodplain. The channel is degraded and geomorphically simple, the riparian corridor is narrow and no hydric soils were observed. The few plants still green in August were clustered along the channel. We observed herbs (such as Achillea millefolium (I), Juncus ensifoliI (R), Carex stIta (R), CirsiumIvense (R), Centaurea stoebe (O) and DipsacusIlvestris (R)), and shrubs and trees (represented by Populus balsamifera ssp. Trichocarpa, Alnus incana, Juniperus occidentalis, Cornus sericea, Betula occidentalis and Pinus ponderosa). As noted above, the Pinus ponderosa on the drained floodplain in the control reach were observed to be thriving, and the largest tree in this reach (Diameter at Breast Height - DBH = 0.86 m) was indeed a Pinus ponderosa, which is classed as a Facultative Upland species.

5.1.3. Whychus Canyon Reach 4 (Transition)

Geomorphological and biological diversities in this reach were greater than in the control reach. Native plants widely observed included Deschampsia s, Elymus repens, Tragopogon dubius, Lactuca seriola, Equisetum s, Mimulus s, Juncus s (including J. balticus, J. effusus, J. ensifolius and J. rticulates - the latter being a new species for the site), and Carex s (including C. pellita, another new species for the site). Invasive species Centaurea stoebe and Verbascum Thapsus were widespread, although observations of the latter were reduced due to on-going removal as part of post-restoration management. Another potentially invasive plant, Rumex crispus, was observed in lower/wetter areas, while the upland invasive species Sisymbrium altissimum, Ericameria nauseosa, and Chrysothamnus viscidiflorus were observed in higher/dryer areas. A further invasive, Erodium cicutarium, was commonly encountered along the unpaved track that runs parallel to the creek in this reach.

In contrast to Canyon Reach 3, Salix s were common in this reach, and there was evidence of developing hydric soils, albeit in a small number of samples. Standing water (a habitat absent from Canyon Reach 3), was observed at a number of locations, including one sizable pond fringed by Typha latifolia. Also, in contrast to Canyon Reach 3, the Pinus ponderosa observed on the floodplain in Reach 4 were in poor health, dying, or dead.

5.1.4. Camp Polk Meadow Preserve (Restored)

Geomorphological and biological diversities were highest in this reach. Plants that were not on the existing Camp Polk Meadow plant list (e.g., Madia glomerata and Carex pellita) were observed. Most plants were native species and the proportion of invasives was lower than those recorded at the control and transition reaches. That said, the invasive species Rumex crispus and Verbascum thapsis were present, albeit mostly in small to moderate densities.

The extensive, wet areas were dominated by Carex and Juncus species, Typha latifolia, Phalaris arundinacea and Scirpus microcarpus, with Equisetum hyemale, and herbs/forbs (e.g., Aster s, Solidago canadensis and Epilobium ciliatum) were also present. Leymus cinereus Equisetum arvense, Holcus lanatus, Rumex crispus (non-native), Smilacina stellata and Mimulus s were observed in the damp and shaded habitats.

Drier areas were mainly occupied by native grasses, including Agrostis s, Festuca s, and Elymus repens. While observations of the non-native, introduced, Poa pratensis, and invasive Bromus tectorum were few, where they did occur they were often locally frequent or abundant. Upland shrubs including Ericameria nauseosa and Chrysothamnus viscidiflorus were common, as were drought-tolerant Juncus and Carex species. We also observed Achillea millefolium and the non-natives Tragopogon dubius, Lactuca serriola and Verbascum thapsis.

Woody plants were mainly

Alnus incana, Pinus ponderosa, Salix s, Populus balsamifera ssp. trichocarpa, and

Populus tremuloides. Other widely observed trees and shrubs included

Ribes cereum, Cornus sericea, Betula occidentalis, Juniperus occidentalis, Spiraea douglassii, and

Ribes cereum (which, although widely observed at Camp Polk, was not recorded in any of the transects (see,

Supplementary Materials B). The upland species

Purshia tridentata was present, but it was mostly confined to the toe of the valley side slope defining the southern boundary of the study area, and so was not recorded. As noted above, only the

Pinus ponderosa (Facultative Upland plant species) specimens observed on the higher, drier parts of floodplain at Camp Polk were healthy; most trees of this species were dying or dead.

5.2. Comparison of Pre-Restoration (2015) and Post-Restoration (2018) Transect Surveys in ‘Canyon Reach 4’ Reach (Transition)

5.2.1. Changes in Plant Communities

When aggregated for all observed plant groups, our results for the transition reach demonstrate statistically-significant increases in both percentage cover and species richness (

Figure 6a and b, respectively).

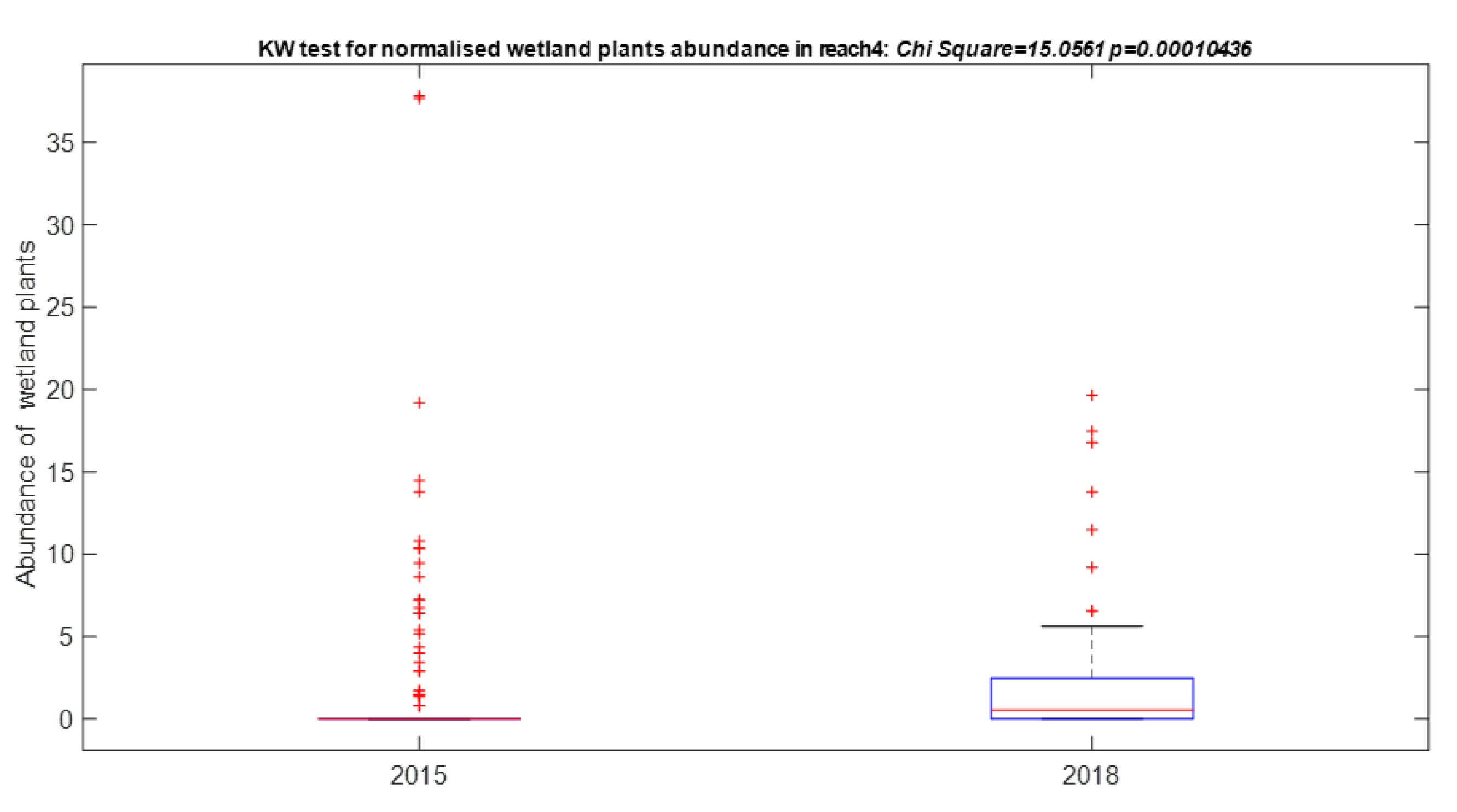

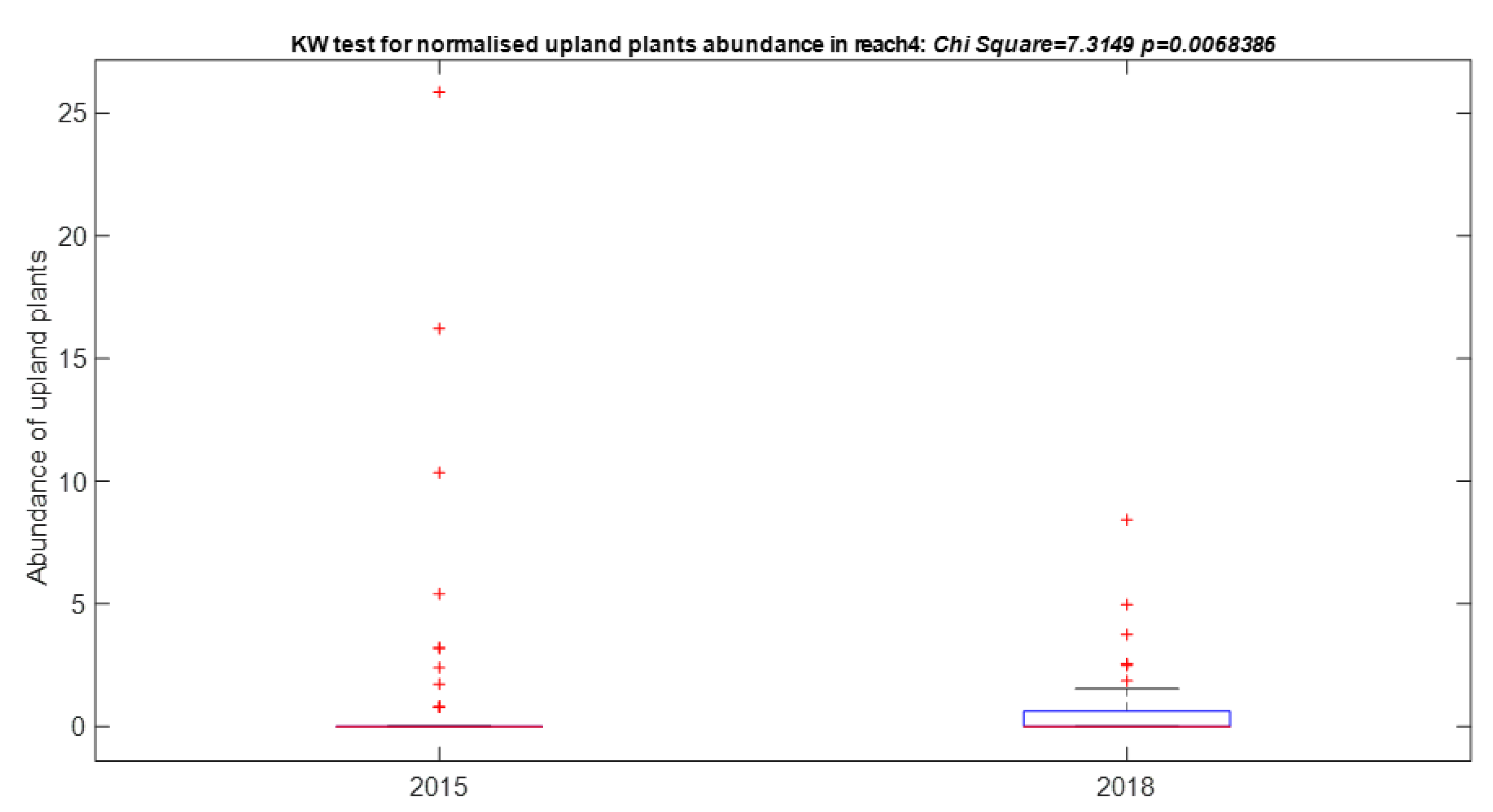

In our analysis, wetland species were considered to be plants with indicator status OBL or FACW, while upland plants were considered to be those with the indicator status FACU or UPL. As plants with FAC (i.e., facultative) indicator status are found in

both wetlands and uplands, they were not included in our comparison of changes specific to wetland and upland plants. Analysis of the normalised plant abundance data pooled for all four transects show that the abundance of wetland (

Figure 7) and upland (

Figure 8) plants had both increased significantly (p<0.05) during the two-years since restoration.

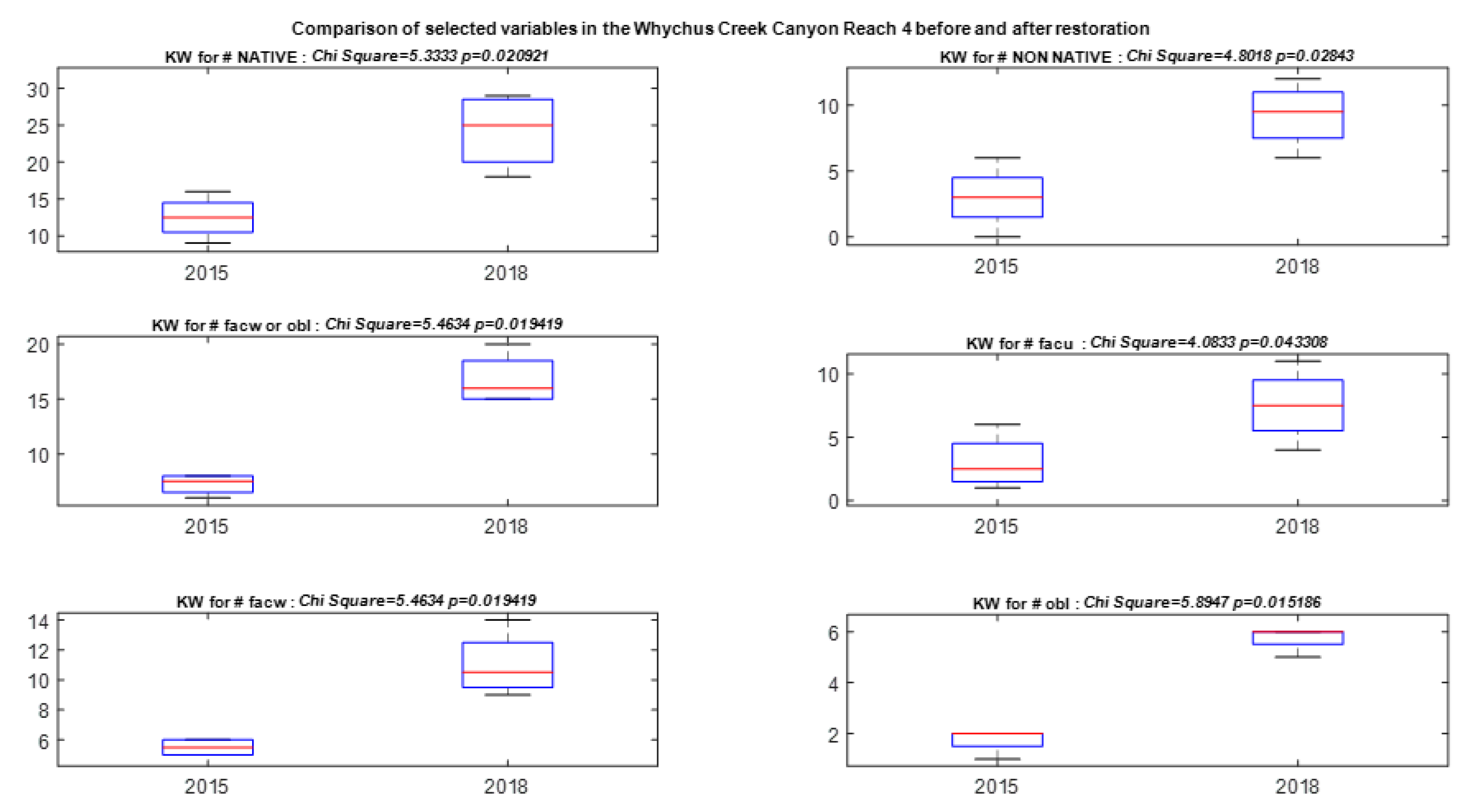

The results of transect surveys for the species richness of specific plant groups are plotted in

Figure 9. There were significant (p < 0.05) increases in species richness of native plants and non-native plants, and those with the statuses of obligate wetland, facultative wetland, and facultative upland. In short, the results for species richness show similar tendencies to those noted above for plant abundance.

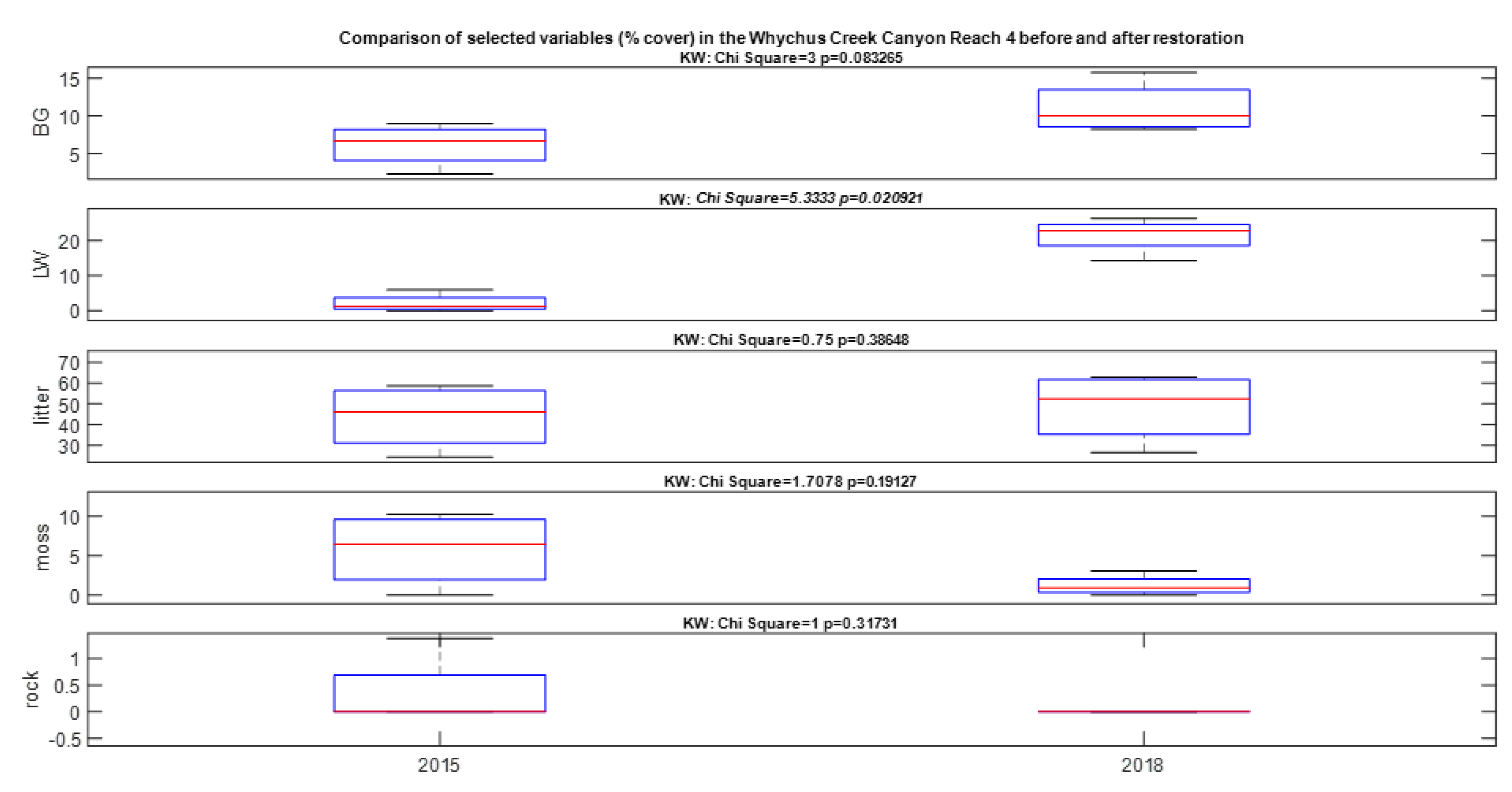

5.2.2. Changes in Ground Cover and Large Wood

In addition to significant increases in plant abundance and richness, we also observed noticeable increases in the percentage cover of bare ground, large wood, and litter in ‘Canyon Reach 4’ following restoration (

Figure 10). In contrast, areas of moss and exposed bedrock, decreased. Statistically, only the increase in large wood was significant (p<0.05).

5.3. Comparisons Between the Vegetation Transect Surveys in Canyon Reach 4 (2015, 2018) and Camp Polk (2018)

Here we report the results of comparisons between vegetation transect results obtained in 2015 and 2018 in the transition reach and in 2018 at the restored reach. For these comparisons we used a 3-factor Principal Component Analysis (PCA), incorporating the Varimax with Kaiser Normalization Rotation Method. We compiled these results in a Rotated Component Matrix (

Table 4).

The PCA clearly separates the transect survey data obtained at ‘Canyon Reach 4’ in 2015 (pre-restoration) from the 2018 (post-restoration) surveys at both at ‘Canyon Reach 4’ and ‘Camp Polk Reserve’. The three principal components (factors) cumulatively explained 64.72% of the variance observed in the data. These factors appear to reflect a combination of site characteristics and the restoration actions.

Vegetation community composition comparisons were also carried out, based on their Jaccard correlation coefficient (JC) and the Sorensen similarity index (SS) (

Table 5).

These analyses reveal that the strongest similarity is that between the 2018 ‘Canyon Reach 4’ and 2018 ‘Camp Polk Meadow’ (transition and restored) plant communities, followed by that between the 2015 and 2018 (pre- and post-restoration) plant communities in ‘Canyon Reach 4’. The most dissimilar plant communities were those observed in 'Canyon Reach 4’ in 2015 (pre-restoration) and at Camp Polk in 2018 (restored).

5.4. Wetland Functions Assessment

The wetland functions assessed in 2018 are presented in this sub-section. ‘Canyon Reach 3’ and ‘Canyon Reach 4’ were reassessed in 2019 (Goss 2019) and the scores were similar to those in 2018, demonstrating that the method is repeatable and so helps validate the approach.

2018 assessments generated estimates for 11 of the 13 wetland functions and contributions to ecosystem services defined by Adamus and Field (2001). The ‘Nitrogen Removal’ and ‘Breeding Waterbird Support’ functions were not assessed. The ‘Nitrogen Removal’ function can only be assessed where well-developed hydric soil features are present (Vasilas et al., 2017). Hydric soils were not observed in any of the study reaches due to the relative immaturity of the wetlands there. For the ‘Breeding Waterbird Support’ function to be assessed, the wetland must include at least one contiguous, lentic water body with an area >0.5 acres. No such water bodies were observed within the study reaches.

Strictly, ‘Canyon Reach 3’ did not meet the criteria for wetland function assessment because it did not include a riverine impounding or slope/flats category wetland. Nevertheless, this unrestored reach provides baseline values for wetland functions. Prior to restoration, provision of wetland functions in Whychus Creek, although lacking, did not result in scores of zero. In that sense, using our estimates for ‘Canyon Reach 3’ as control values in our comparisons (rather than 11 zeros), makes our comparisons conservative. Consequently, confidence is increased in our interpretations of the changes to the provision of wetland functions following from restoration of ‘Camp Polk Reserve’ and’ Canyon Reach 4’.

Wetland function scores are listed in

Table 6 and the scores for the three study reaches are compared in

Table 7.

Table 6 indicates that Camp Polk Meadow (restored) generally exhibits significantly higher functionality than the Canyon Reach 3 (control) and Canyon Reach 4 (transition) reaches. Notably, the restored reach shows significant improvements in functions such as ‘Water Storage & Delay’, ’Sediment Stabilization & Phosphorus Retention’, and ‘Primary Production’. These enhancements suggest that restoration has successfully increased the capacity of the floodplain to store and delay water, stabilize sediments, and create organic matter. Additionally, the higher scores for ‘Resident Fish Habitat Support’ and ‘Anadromous Fish Habitat Support’ in the restored reach indicate better conditions for fish populations, which is crucial for salmon recovery in Whychus Creek. The Canyon reach 4 (transition) reach also shows promising improvements, particularly in functions related to habitat support for invertebrates, amphibians, and turtles; reflecting the benefits of increased habitat heterogeneity and lateral connectivity.

For Canyon Reach 3 versus Camp Polk Meadow, the results listed in columns 3 and 4 of

Table 7 indicate that median scores for 7 of 11 wetland functions were significantly higher in the restored reach than in the control reach. Specifically, Camp Polk exhibited higher scores in ‘Water Storage & Delay’, ‘Sediment Stabilization & Phosphorus Retention’, ‘Primary Production’, ‘Resident Fish Habitat Support’, ‘Anadromous Fish Habitat Support’, ‘Invertebrate Habitat Support’, and ‘Amphibian & Turtle Habitat’. These differences highlight the effectiveness of restoration efforts in enhancing floodplain functionality and supporting diverse aquatic and terrestrial habitats. Improvements in these functions indicate increased water retention, sediment stabilization, and habitat quality, which collectively contribute to the overall ecological health, biodiversity, and resilience in the restored reach.

For Canyon Reach 4 versus Camp Polk Meadow, the results listed in columns 5 and 6 of

Table 7 indicate that median scores for 5 of 11 wetland functions were significantly different. Specifically, the restored reach at Camp Polk showed significantly higher scores in ‘Water Storage & Delay’, ‘Sediment Stabilization & Phosphorus Retention’, ‘Primary Production’, ‘Anadromous Fish Habitat Support’, and ‘Amphibian & Turtle Habitat’. Furthermore, the difference in the scores for the ‘Support of Characteristic Vegetation’ is almost significant (p=0.052). These differences underscore the longer-term (i.e., six years versus 2 years post-restoration) benefits of Stage Zero restoration in enhancing wetland functions and ecosystem services. In this context, the higher scores for these functions at the restored reach provide a window on what may be achieved in the ‘Canyon Reach 4’ transition reach.

For Canyon Reach 3 versus Canyon Reach 4, the results listed in columns 7 and 8 of

Table 7 indicate that median scores for 9 of 11 wetland functions were significantly different. The chi-square statistic for ‘Anadromous Fish Habitat support’ provides a high level of confidence that, just two-years post-restoration, provision of this function in the transition reach is already better than that in the control reach. This is important as one of the primary targets for the restoration is to support salmon recovery, specifically Chinook

(Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) and Steelhead

(Oncorhynchus mykiss). Significant differences were also revealed for the majority of other functions, including ‘Support of characteristic vegetation’, ‘Water Storage & Delay’, and ‘Sediment Stabilization & Phosphorus Retention’. This demonstrates that restoration efforts in Canyon Reach 4 have enhanced habitat quality, increased water retention, and improved sediment control, which collectively contribute to improved ecological health, biodiversity and resilience in the transition reach.

The median score for ‘Thermoregulation’ was slightly higher in the control reach, although the difference was not statistically significant. To interpret this outcome, it is important to consider how the ‘Thermoregulation’ function score is derived when applying the hydrogeomorphic-based assessment method. This score is derived from the product of two indicators:

the percentage of permanent zone shaded by woody or aquatic plants and,

the predominant depth category during biennial low water.

A stream habitat survey performed in 2011 (Mork, unpublished) included observation of the extent of permanent shading in Canyon Reaches ‘3’ and ‘4’ prior to restoration. While results ranged widely (31-94%), the average value was the same in both reaches, 51%. This was expected as, prior to restoration, these reaches were similar in all respects. In 2017, the stream habitat survey was repeated in Canyon Reach 4 (i.e., 1-year post-restoration). The range of values remained high (14-94%), but the reach-averaged score had risen slightly, to 53%. As conditions had not changed in the control reach, it is reasonable to assume that control value remained 51%. This finding indicates that there was a small increase in permanent shading in Canyon Reach 4 compared to Canyon Reach 3, just 1-year post- restoration.

From column 4 of

Table 6, it is evident the scores for all the polygons in the Canyon Reach 3 are the same (0.3), reflecting the uniform conditions in the control reach. Conversely, scores for Canyon Reach 4 range from 0.120 to 0.386, reflecting the greater diversity of shading and water depths in the transition reach. The higher range in the transition reach results from its heterogenous environment, which is ecologically beneficial as it provides a wider range of thermal habitats for use by both warm and cool water flora and fauna (Wilby et al., 2018).

The median score for only one wetland function, ‘Songbird Habitat Support’ is significantly higher in the control reach. The score for this function is derived from 19 indicators, which include the percentage of the study area occupied by closed-canopy woodland, the diameters of the largest trees and the diameters of dead trees (snags). These (and several other) indicators increase with the extent and maturity of woodland. It is therefore logical that Canyon Reach 3 (control), which has a well-developed gallery forest within the narrow, but continuous riparian fringe along its channel, should score higher for this function. Probably, the score for ‘Songbird Habitat Support’ in Canyon Reach 4 (transition) will increase as riparian trees mature in the riparian area currently developing across the full width of the valley floor.

6. Discussion

6.1. Interpretation of Post-Restoration Changes in Vegetation and Ground Cover in Canyon Reach 4 (Transition)

6.1.1. Changes in Vegetation

Two years following project completion, restoration of ‘Canyon Reach 4’ led to statistically-significant increases in both percentage plant cover and species richness for all plant groups (Figures 6a and b, respectively). Within this overall result, the increased wetland plant abundance following restoration (

Figure 7) was expected; indeed, it was one of the restoration targets specified when restoration of ‘Canyon Reach 4’ was proposed. The increase in upland plant abundance (

Figure 8) appears counterintuitive, but may be explained by four key, project-specific, factors:

purposeful construction of micro-terrain in the cut and fill surfaces created during restoration, including local depressions with enhanced stream, hyporheic, and groundwater connections, interspersed with low terraces and ‘leave islands’ that are slightly higher and, therefore, drier;

the planting palette used in the restoration project (listed in

Supplementary Materials A) included both wetland and upland species, which accounted for hydrological patchiness related to the impacts of local terrain on soil wetness and micro-habitats;

alleviation of seasonal water stresses on established vegetation growing on the higher surfaces that were not disturbed during restoration, and;

recognition that the two years since restoration activity was completed is probably not enough time for wetland flora to have out-competed disadvantaged upland plants within the rehydrated margin areas on the valley floor.

However, succession from upland to wetland species abundance is complicated. The mosaic of micro-habitats created during restoration is dynamic and, in some areas, morphological adjustments and channel evolution can create opportunities for upland plants. For example, some anabranches in the anastomosed planform featured head cuts that have lowered the channel bed slightly, locally reducing hydrological connectivity between flow in the channel, its hyporheic fringe, and the floodplain. Upland plants in those locales appeared to be surviving and we would expect them to persist until the trend for local incision is reversed and the drier patch is rehydrated.

Results for species richness (

Figure 9) are similar to those for abundance in that values for all plant indicator statuses increased following restoration. Increases recorded in non-native species have been noted and volunteers are assisting with on-going efforts to control the spread of non-native species and noxious weeds.

In both the restored and transition reaches, wetland, facultative, and upland species coexist post-restoration, are in close proximity, and form a ‘shifting floodplain mosaic’ (Stanford et al. 2005) of heterogenous habitats. The project’s proponents and the authors regard this as a primary benefit of restoration to Stage 0.

6.1.2. Changes in Ground Cover

Observed increases in the area of bare ground and the amount of large wood following restoration (

Figure 9) are explained by two key aspects of restoration design:

That said, restoration also involved extensive planting on the newly-created, bare surfaces and, in addition to large wood added artificially, we also observed pieces recruited naturally through tree fall (especially of dying Pinus ponderosa) and trapping of trees and branches carried into the transition reach from upstream.

The slight, post-restoration increase in litter and decrease in moss were to be expected given the significant increase in vegetation cover. Burial of bedrock exposed within the incised channel when that channel was filled-in as part of its 2016 restoration explains why this category of surface cover was observed to have been practically eliminated.

6.2. Interpretation of Changes in Vegetation in Canyon Reach 4 (Transition) and at Camp Polk Meadow (Restored)

Comparison of vegetation transect data from the transition and restored reaches provides insights into the time dimension of ecological recovery following Stage 0 restoration. The Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and similarity indices reveal that by 2018, only two years post-restoration, the plant communities in Canyon Reach 4 had already diverged substantially from those observed in this reach in 2015, which was prior to its restoration. They further demonstrate that post-restoration plant assemblages in Canyon Reach 4 closely resembled those observed at Camp Polk Meadow, which was restored in 2012. This suggests that significant ecological progress towards the rich and diverse communities observed in the restored reach six years post-restoration had occurred in the transition reach just two years following restoration. This is consistent with the hypothesis that restoring lateral geomorphic and hydrologic connectivity does promote rapid recovery of habitat heterogeneity and biodiversity.

However, the PCA also indicates that the vegetation assemblages in the restored reach remain distinct from those in the transition reach. A longer post-restoration period has given more chance for ecological succession at Camp Polk Meadow, during which plant communities have had more time to mature, stabilize, adapt to new hydrological regimes, and respond to biotic interactions. This finding implies that further changes are likely in the transition reach, as habitats continue to evolve.

The PCA factors also clearly separate the pre-restoration, 2015 transect survey data for the transition reach from the 2018, post-restoration data for both the transition and restored reaches. Hence, in the PCA, the restoration factor plays a more influential role in determining similarities and differences between plant communities than does the location factor (i.e., whether the assemblage is in Canyon Reach 4 or at Camp Polk Meadow).

The three sets of Jaccard and Sorensen scores listed in

Table 5 show that the strongest similarity is that between the plant communities in the transition and restored reaches, followed by that between the plant communities in Canyon Reach 4, before and after restoration. The most dissimilar plant communities were those observed in Canyon Reach 4 in 2015 and the restored reach at Camp Polk Meadow in 2018. These findings underscore the strong influence of restoration on vegetation assemblages and highlight the importance of time in shaping mature, resilient assemblages.

The differences revealed by our analysis may also be partly attributable to the cumulative effects of seasonal cycles, recruitment of additional species, and competition between plants that develops over longer timescales. For example, the presence of greater diversity of native, wetland species and the reduced presence of invasive plants in the restored reach suggest that lateral floodplain reconnection promotes establishment of more stable, native and diverse plant communities over time.

In summary, our findings support the hypothesis that restoration outcomes improve with time and highlight the need for further long-term monitoring to capture the trajectory of ecological recovery.

6.3. Implications for Habitat Heterogeneity and Biodiversity

Dynamic fluvial systems and net-depositional floodplain environments have long been known to contribute to increased habitat heterogeneity (Yarnell et al., 2016). Post-restoration vegetation transects in Canyon Reach 4 are consistent with this finding. Our findings indicate that reconnection of Whychus Creek to its floodplain has prompted the creation of a shifting mosaic of aquatic, mesic, and terrestrial habitats related to differences in surface elevations, distance from a channel, and water table depth. The variety of habitats is also evident through the outcomes of the focal community vegetation surveys, which unambiguously demonstrate substantial increases in plant species richness, commensurate with increases in the diversity of surveyed habitats. Increases in plant and habitat diversity are not only important in themselves, but are also beneficial for other biological taxa; in particular invertebrate and vertebrate animals (Henning, 2004). The statistical results for the wetland function assessments support this conclusion, alongside general observations of fauna in other unrestored and restored reaches of Whychus Creek.

For example, rattlesnakes (Crotalus oreganus) were not encountered in the unrestored Canyon Reach 3, but were observed both in the transitional Canyon Reach 4 and at the restored reach at Camp Polk Meadow. Mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) also appeared to be more common at Camp Polk Meadow. The transition and restored reaches were observed to host good numbers of birds. For example, hummingbirds (Trochilidae) were observed in abundance at Camp Polk Meadow and, to a lesser degree, Canyon Reach 4. Similarly, American dippers (Cinclus mexicanus) were repeatedly encountered at Camp Polk, a family of at least 10+ Merganser (Merganser merganser) was seen, and an old warbler’s nest was collected from the Typha-dominated wetland at Camp Polk Meadow. We did not observe these bird species in either of the Canyon reaches and their common occurrence at Camp Polk provides indirect evidence for the abundance of insects, aquatic macroinvertebrates, and fish, which are the preferred food source for warblers, dippers and mergansers, respectively.

Camp Polk Meadow also appears to be very hospitable for dragonflies and damselflies (Odonata), with representatives of both Aeshnidae and Libellulidae regularly encountered. In contrast, we saw no dragonflies in the degraded, control reach, whilst at the transitional reach the frequency of encounters was noticeably lower.

Butterflies (Cercyonis pegala, Colias spp, Papilio spp) were variously encountered at the restored and transitional reaches. It should be noted, however, that (based on our qualitative observations) biodiversity of Lepidoptera appeared to be the highest in Canyon Reach 4. This suggests that transitional reaches may be providing optimal conditions for biodiversity of Lepidoptera; a hypothesis that should be investigated by further monitoring and research.

6.3. Ecosystem Services

When assessing the value classes proposed by Mitsch and Gosslink (2015), ‘Ecosystem Values’ and ‘Global Values’ most directly relate to human wellbeing and can therefore be interpreted to represent ecosystem services. While none of the functions assessed with the methodology we used belong to the ‘Global Values’ category, four of the functions in the ‘Ecosystem values’ category showed a significant increase in the restored reach; namely ‘Water Storage & Delay’, ‘Sediment Stabilization & ‘Phosphorus Retention’, ‘Primary Production’, and ‘Support of Characteristic Vegetation’. This is evidence that Stage 0 restoration is contributing to recovery of valuable Ecosystem Services previously lost from Whychus Creek.

Of the Wetland Functions categories listed in

Table 2, most had higher median scores in the recently restored Canyon Reach 4 than the unrestored Canyon Reach 3 (

Table 7). Significant increases in ‘Resident Fish Habitat Support’, ‘Anadromous Fish Habitat Support’, ‘Invertebrate Habitat Support’, ‘Amphibian & Turtle Habitat’ and ‘Wintering & Migratory Waterbird Support’ can be attributed to the greater wetland habitat diversity and heterogeneity that has developed just two years after Stage 0 restoration.

Wetlands have an important role in the hydrological cycle, and are often said to ‘act like sponges’, as they soak up water during wet periods and then release it gradually (Bucher et al., 1993). In the transition reach, the ‘Water Storage and Delay’ function is significantly different from the unrestored, control Canyon Reach 3. Hence there is a statistically confirmed improvement in flood resilience. Furthermore, there is a substantial body of literature relating to the role of wetlands in the protection and enhancement of water quality (Maltby, 2009). The median function score for ‘Sediment Stabilisation and Phosphorus Retention’ in Canyon Reach 4 was significantly different from the score for the control reach. Hence, our wetland functions assessment suggests that restoration to Stage 0 has benefited water quality. Analysing the wetland functions of the riparian environment in terms of the ecosystem services they offer allows better communication with stakeholders and the public by creating more direct links with human wellbeing, which helps to secure further support for process-based restoration projects (Albert et al., 2016). Increased support can lead to additional funding being secured for future Stage 0 projects and their post-project monitoring (Bullock et al., 2011).

6.3. Importance of Long-Term Monitoring and Implications for Further Studies

Our results compare riparian vegetation assemblages and wetland functions in two restored reaches of Whychus Creek with those in an unrestored, control reach. Given the limited time since the restoration, we refer to conditions in the more recently restored Canyon Reach 4 as being transitional. There is an expectation that riparian plant assemblages and wetland functions in Canyon Reach 4 should both continue to improve through time; to match those recorded at Camp Polk Meadow. This expectation can only be substantiated by further monitoring. Notwithstanding this, it should be recognised that the establishment of the heterogeneous mosaics of aquatic, mesic and xeric habitats recorded in Canyon Reach 4 are already benefiting a wide range of plant and animal taxa. Achieving this two years after restoration can justifiably be described as an optimal river restoration outcome.

In Whychus Canyon, and at other restoration projects, the need for further post-project monitoring is clear. Most restoration projects lack rigorous post-restoration monitoring of ecological outcomes, often due to logistical and financial constraints. There is considerable scope for improvement, particularly detailed analysis of the effects of restoration on target species (Bernhardt et al. 2007, Katz et al. 2007). The role of ecology is becoming increasingly important, particularly in supporting ecosystem resilience, climate change mitigation and adaptation. Without more extensive monitoring programmes on river restoration projects across the globe, the ecological outcomes, whether positive or negative, cannot be fully understood. This has become an increasingly common theme in discourse surrounding river restoration, for example with the introduction of concepts such as biomic river restoration (Johnson et al., 2019b).

Despite uncertainties regarding the precise future patterns of ecosystem functioning in the restored and transitional reaches of Whychus Creek, the benefits achieved so far are unambiguous. The documented increases in plant diversity and richness, and wetland functions achieved through restoration to Stage 0 justify further restoration actions both at Whychus Creek and in other drainage systems. The results presented in this paper should, therefore, be of use for practitioners, policy makers, and funders, as well as provide a useful reference for further research.

7. Conclusions

Restoration of Canyon Reach 4 of Whychus Creek significantly increased riparian vegetation abundance and species richness within two years, creating a heterogeneous mosaic of aquatic, mesic, and upland habitats.

- 2.

Wetland Functions

Wetland function scores improve markedly in restored reaches compared to the unrestored control, particularly for water storage, sediment stabilization, and habitat support for fish, amphibians, and invertebrates. These improvements indicate enhanced ecosystem services and flood resilience.

- 3.

Habitat and Biodiversity

Six years after restoration to the form of an alluvial fan, the upper part of Camp Polk Meadow exhibited greater geomorphic and biologic diversity, supporting a wider range of taxa and providing evidence that Stage 0 restoration promotes biodiversity, ecological complexity and resilience.

- 4.

Comparison with Long-Term Restoration

While the restored Camp Polk reach outperformed the transitional Canyon Reach 4 ecologically, the similarity between their plant community compositions and wetland functions suggests that both reaches are on a positive trajectory toward fully recovering from the adverse impacts of past Anthropogenic channel straightening, relocation, incision, and floodplain disconnection.

- 5.

Implications and Future Work

The findings support process-led and process-reset restoration approaches that prioritize full floodplain reconnection. However, continued, long-term monitoring is essential to confirm initial trends, guide adaptive management, and strengthen the evidence base for Stage 0 restoration as a future-resilient strategy.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1: A. Pallette of native riparian and wetland species planted in areas disturbed during restoration of Canyon Reach 4. List of B. Full list of plants recorded in the focal study areas of Whychus Creek.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Krivtsov and Goss; validation, Mork and Allen; formal analysis, Krivtsov and Goss; investigation and resources, Allen and Mork; data curation, Mork and Krivtsov, writing—original draft preparation, Krivtsov; writing—review and editing, All; visualization, Mork and Krivtsov; supervision, Thorne; project administration, Mork; funding acquisition, Mork. All authors participated in field data collection and have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting reported results can be obtained from Lauren Mork at the Upper Deschutes Watershed Council, Bend, OR.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Adamus, P.R. and Field, D. 2001. Guidebook for Hydrogeomorphic (HGM)–based Assessment of Oregon Wetland and Riparian Sites: Statewide Classification and Profiles. Oregon Division of State Lands, Salem, OR.

- Albert, C.; Galler, C.; Hermes, J.; Neuendorf, F.; Von Haaren, C. and Lovett, A. Applying ecosystem services indicators in landscape planning and management: The ES-in-Planning framework. Ecological Indicators 2016, 61, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, C.D. and Breshears, D.D. Drought-induced shift of a forest/woodland ecotone: rapid landscape response to climate variation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1998, 95, 14839–14842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, C.; Savage, M.; Falk, D.; Suckling, K.; Swetnam, T.; Schulke, T.; Stacey, P.; Morgan, P.; Hoffman, M. and Klingel, J. Ecological restoration of southwestern ponderosa pine ecosystems: a broad perspective. Ecological Applications 2002, 12, 1418–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beechie, T.; Imaki, H.; Greene, J.; Wade, A.; Wu, H.; Pess, G.; Roni, P.; Kimball, J.; Stanford, J.; Kiffney, P. and Mantua, N. Restoring salmon habitat for a changing climate. River Research and Applications 2013, 29, 939–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behan, J.; Fetcho, K.; Davis, R. and Gaines, L., River Restoration to Achieve a Stage 0 Condition: Summary of a Workshop held November. 2021, 5-6, 2020.

- Bernhardt, E.S. and Palmer M. A. River restoration: The fuzzy logic of repairing reaches to reverse watershed scale degradation. Ecological Applications 2011, 21, 1926–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booth, D.; Scholz, J.; Beechie, T. and Ralph, S. C. Integrating limiting factors analysis with process-based restoration to improve recovery of endangered salmonids in the Pacific Northwest, USA. Water 2016, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A. G. , Lespez, L., Sear, D. A., Macaire, J.-J., Houben, P., Klimek, K., et al. Natural vs Anthropogenic Streams in Europe: History, Ecology and Implications for Restoration, River-Rewilding and Riverine Ecosystem Services. Earth Sci. Rev. 2018, 180, 185–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucher, E. H., Bonetto, A., Boyle T., Canevari P., Castro G., Huszar P. and Stone, T. (1993). Hidroviaan initial environmental examination of the Paraguay - Parana waterway. Wetlands for the Americas Publication No. 10: Manomet MA, USA.

- Bullock, A. and Acreman, M.C. The role of wetlands in the hydrological cycle. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 2003, 7, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, N.T. and Lipiec, E., 2020. Flood Risk Reduction From Natural and Nature-Based Features: Army Corps of Engineers Authorities. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. https://www.everycrsreport.com/files/20200427_R46328_5ecc0e851941e017b50b62075a15c4abbbd36d19.pdf.

- Ciotti, D.C.; Mckee, J.; Pope, K.L.; Kondolf, G.M. and Pollock, M.M. Design criteria for process-based restoration of fluvial systems. Bioscience 2021, 71, 831–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cluer, B.; Thorne, C. A Stream Evolution Model Integrating Habitat and Ecosystem Benefits. River Res. Applic. 2014, 30, 135–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, N.C. How much wetland has the world lost? Long-term and recent trends in global wetland area. Marine and Freshwater Research 2014, 65, 934–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downs, P. and Gregory, K., 2014. River channel management: towards sustainable catchment hydrosystems. Routledge.

- Finlayson, C.M.; Davidson, N.C.; Spiers, A.G. and Stevenson, N.J. Global wetland inventory–current status and future priorities. Marine and Freshwater Research 1999, 50, 717–727. [Google Scholar]

- Flitcroft, R.L.; Brignon, W.R.; Staab, B.; Bellmore, J.R.; Burnett, J.; Burns, P.; Cluer, B.; Giannico, G.; Helstab, J.M.; Jennings, J. and Mayes, C. Rehabilitating valley floors to a stage 0 condition: A synthesis of opening outcomes. Frontiers in Environmental Science 2022, 10, 892268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fluet-Chouinard, E.; Stocker, B.D.; Zhang, Z.; Malhotra, A.; Melton, J.R.; Poulter, B.; Kaplan, J.O.; Goldewijk, K.K.; Siebert, S.; Minayeva, T. and Hugelius, G. Extensive global wetland loss over the past three centuries. Nature 2023, 614, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geist, J. and Hawkins, S.J. Habitat recovery and restoration in aquatic ecosystems: current progress and future challenges. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 2016, 26, 942–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glassic, H.C.; Al-Chokhachy, R.; Wheaton, J.; Macfarlane, W.W.; Jordan, C.E.; Murphy, B.; Shahverdian, S.; Bennett, S.; Bouwes, N.; Fryirs, K.; Brierley, G.; Ciotti, D.; Bailey, P.; Bartelt, K.; Belletti, B.; Bizzi, S.; Brasington, J.; Camp, R.; Fairfax, E.; Gilbert, J.; Jimenez, J.; Maestas, J.; Mandish, T.; McNamara, A.; Miller, S.; Morizot, B.; Perle, M.; Piégay, H.; Reid, H.; Reynolds, L.V.; Saunders, W.C.; Shallcross, A.; Skidmore, P.; Smith, R.; Terrier, B.; Wathen, G.; Weber, N. 2025. Principles of Riverscape Health, WIREs Water, 10.1002/wat2.70028, 12, 4.

- Goss, T. (2020) Assessing the Wetlands of a Stage 0 River Restoration Project on Whychus Creek, Deschutes County, Oregon. Unpublished dissertation submitted in fulfilment for award of the degree MSc., School of Geography, University of Nottingham, UK.

- Graziano, M.P.; Deguire, A.K.; Surasinghe, T.D. Riparian Buffers as a Critical Landscape Feature: Insights for Riverscape Conservation and Policy Renovations. Diversity 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardouin, L.; Decharme, B.; Colin, J. and Delire, C. Climate-driven projections of future global wetlands extent. Earth's Future 2024, 12, p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauer, F. R. , Locke, H., Dreitz, V. J., Hebblewhite, M., Lowe, W. H.,Muhlefeld, C. C., et al. Gravel-bed River Floodplains are the Ecological Nexus of Glaciated Mountain Landscapes. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1600026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hearnshaw, E.J.S. and Hughey, K.F.D. 2010. A tolerance range approach for the investigation of values provided by Te Waihora/Lake Ellesmere, Report 17, Centre for Land, Environment & People, Lincoln University, Christchurch, NZ, ISBN 978-0-86476-251-1, 78p.

- Henning, J., 2004. An Evaluation of Fish and Amphibian Use of Restored and Natural Floodplain Wetlands. Final Report EPA Grant CD-97024901-1. Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, Olympia, Washington, USA, 81.

- Hinshaw, S. and Wohl, E. Quantitatively estimating carbon sequestration potential in soil and large wood in the context of river restoration. Frontiers in Earth Science 2021, 9, 708895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hruby, T.; Bruner, K.; Cooke, S.; Dublonica, K.; Gersib, R.; Granger, T.; Reinelt, L.; Richter, K.; Sheldon, D.; Wald, A. and Weinmann, F. (1999). Methods for Assessing Wetland Functions. Volume 1: Riverine and Depressional Wetlands in the Lowlands of Western Washington. Ecology Publication 99-115. Washington State Department of Ecology: Olympia, WA.

- Johnson, M.F.; Thorne, C.R.; Castro, J.M.; Kondolf, G.M.; Mazzacano, C.S.; Rood, S.B. and Westbrook, C. Biomic river restoration: A new focus for river management. River Research and Applications 2020, 36, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, S. L. , Barnas, K., Hicks, R., Cowen, J., and Jenkinson, R. Freshwater habitat restoration actions in the Pacific Northwest: A decade's investment in habitat improvement. Restoration Ecology 2007, 15, 494–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Johnson, C.J.; Rex, J.F.; Todd, M. 2024. Long-term riparian forest loss around streams, lakes, and wetlands in ecologically diverse managed and unmanaged landscapes. Forest Ecology and Management, Volume 562, 2024, 121931, ISSN 0378-1127, doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2024.121931.

- McCabe, C.L.; Matthaei, C.D.; Tonkin, J.D. The ecological benefits of more room for rivers. Nat Water 2025, 3, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, M.; Chacko, A.; Rameshan, M. Gopikrishna, V.G., Kannan, V. M., Vishnu, N.G. Sasi, S.A., Baiju, K.R. 2022. Restoring Riparian Ecosystems During the UN-Decade on Ecosystem Restoration: A Global Perspective. Anthr. Sci. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Mateos, D.; Power, M.E.; Comín, F.A. and Yockteng, R. Structural and functional loss in restored wetland ecosystems. PLoS biology 2012, 10, e1001247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mork, L.; Allen, K.; Goss, T.; Thorne, C. and Krivtsov, V. 2022. Increase in riparian vegetation following a ‘Stage 0’river restoration project on Whychus Creek, Oregon. In Proceedings of the 39th IAHR World Congress, 19-24 June 2022, Granada, Spain. International Association for Hydro-Environment Engineering and Research (IAHR).

- Mork, L.; Perle, M.; Thorne, C. (2018). Stage 0 Outcomes: Monitoring Results and Stakeholder Views. Upper Deschutes Watershed Council: Bend, OR.

- Lashford, C.; Lavers, T.; Reaney, S.; Charlesworth, S.; Burgess-Gamble, L. and Dale, J. Sustainable catchment-wide flood management: A review of the terminology and application of sustainable catchment flood management techniques in the UK. Water 2022, 14, 1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, C. , Rothero, E., Gowing, D., Nisbet, T., Barsoum N., Broadmeadow, S., Skinner, A., (20ı8) The natural capital of floodplains: management, protection and restoration to deliver greater benefits. Valuing Nature Natural Capital Synthesis Report VNP09. https://valuing-nature.

- Lichvar, R.W.; NC Melvin, M.L. Butterwick, and W.N. Kirchner. 2012. National Wetland Plant List Indicator Rating Definitions. ERDC/CRREL TR-12-1. U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Center, Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory, Hanover, New Hampshire.

- Maltby, E., ed., (2009). Functional assessment of wetlands: Towards evaluation of ecosystem services. Cambridge: Woodhead Publishing.

- Modi, A.; Kapoor, V. and Tare, V. River space: A hydro-bio-geomorphic framework for sustainable river-floodplain management. Science of the Total Environment 2022, 812, 151470. Naiman R.J., Decamps H., Pollock M. The role of riparian corridors in maintaining regional biodiversity. Ecological Applications 1993, 3, 209–212. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, M.A.; Hondula, K.L. and Koch, B.J. Ecological restoration of streams and rivers: shifting strategies and shifting goals. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 2014, 45, 247–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perle, M.; Mork, L.; Thorne, C. ‘Stage Zero’ Restoration of Whychus Creek, Oregon: Monitoring Results and Lessons Learned. www.ecotoneinc.com: UDWC; 2018.

- Piégay, H.; Cottet, M. and Lamouroux, N. Innovative approaches in river management and restoration. River Research and Applications 2020, 36, 875–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, M.M.; Norman, L.M. 2025. Wet meadow regeneration through restoration of biophysical feedbacks. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 13, 1592036. [CrossRef]

- Pollock, M.M.; Beechie, T.J.; Wheaton, J.M.; Jordan, C.E.; Bouwes, N.; Weber, N. and Volk, C. Using beaver dams to restore incised stream ecosystems. BioScience 2014, 64, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, P. D. , Helstab, M. , and Niezgoda, S. L. A Process-based Approach to Restoring Depositional River Valleys to Stage 0, an Anastomosing Channel Network. River Res. Appl. 2019, 35, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, P.; Staab, B.; Cluer, B. and Thorne, C. Rediscovering, reevaluating, and restoring Entiatqua: Identifying pre-Anthropocene valleys in North Cascadia, USA. River Research and Applications 2022, 38, 1527–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugh, B.E.; Colley, M.; Dugdale, S.J.; Edwards, P.; Flitcroft, R.; Holz, A.; Johnson, M.; Mariani, M.; Means-Brous, M.; Meyer, K. and Moffett, K.B. A possible role for river restoration enhancing biodiversity through interaction with wildfire. Global Ecology and Biogeography 2022, 31, 1990–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riis, T.; Kelly-Quinn, M.; Aguiar, F.C.; Manolaki, P.; Bruno, D.; Bejarano, M.D.; Clerici, N.; Fernandes, M.R.; Franco, J.C.; Pettit, N.; Portela, A.P.; Tammeorg, O.; Tammeorg, P.; Rodríguez-González, P.M.; Dufour, S. 2020. Global Overview of Ecosystem Services Provided by Riparian Vegetation, BioScience, Volume 70, Issue 6, June 2020. [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.D.; Ammann, A.; Bartoldus, C. and Brinson, M.M. (1995). An Approach for Assessing Wetland Functions Using Hydrogeomorphic Classification, Reference Wetlands and Functional indices. US Army Corps of Engineers: Vicksburg, MS.

- US Army Corps of Engineers 2008. Regional Supplement to the Corps of Engineers Wetland Delineation Manual: Arid West Region (Version 2.0), ed. J.S. US Army Corps of Engineers 2008. Regional Supplement to the Corps of Engineers Wetland Delineation Manual: Arid West Region (Version 2.0), ed. J.S. Wakeley, R.W. Lichvar, and C.V. Noble. ERCD/EL TR-08-28. Vicksburg, MS: U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Center.

- US Forest Service 1998. Sisters/Whychus Watershed Analysis. Sisters Ranger District, Deschutes National Forest. Sisters, Oregon. 384 p.

- Vasilas, L.M.; Hurt, G.W. and Berkowitz, J.F. (2017). Field Indicators of Hydric Soils in the United States: A Guide for Identifying and Delineating Hydric Soils, Version 8.1. United States Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service: Washington, DC.

- Von Humboldt, A. and Bonpland, A. (1807) Essai sur la géographie des plantes (Essay on the geography of plants). Paris: Levrault & Schoell.

- Wohl, E.; Castro, J.; Cluer, B.; Merritts, D.; Powers, P.; Staab, B. and Thorne, C. Rediscovering, Reevaluating, and Restoring Lost River-Wetland Corridors. Front. Earth Sci. 2021, 9, 653623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarnell, S.M.; Mount, J.F. and Larsen, E.W. The influence of relative sediment supply on riverine habitat heterogeneity. Geomorphology 2006, 80, 310–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Whychus Creek location maps. Ownerships: TSID = Three Sisters Irrigation District; BLM = Bureau of Land Management; USFS Deschutes = US Forest Service Deschutes National Forest; USFS Grasslands = USFS Crooked River National Grasslands.

Figure 1.

Whychus Creek location maps. Ownerships: TSID = Three Sisters Irrigation District; BLM = Bureau of Land Management; USFS Deschutes = US Forest Service Deschutes National Forest; USFS Grasslands = USFS Crooked River National Grasslands.

Figure 2.

Geomorphology of the valley floor of Whychus Creek before and after restoration to Stage 0 at (a, b) ‘Canyon Reach 4’ and (c, d) ‘Camp Polk Meadow’. In this study, these reaches are referred to as the ‘transition’ and ‘restored’ reaches, respectively.

Figure 2.

Geomorphology of the valley floor of Whychus Creek before and after restoration to Stage 0 at (a, b) ‘Canyon Reach 4’ and (c, d) ‘Camp Polk Meadow’. In this study, these reaches are referred to as the ‘transition’ and ‘restored’ reaches, respectively.

Figure 3.

Pre- and post-restoration views of part of Canyon Reach 4. (a) pre-project high terrace in 2015. The anthropogenically-relocated, incised, single-thread channel is located within the narrow riparian corridor at the base of the far valley wall. (b) Reconnected , braided channel-floodplain system created by lowering the terrace during summer 2016. (c) Anastomosed river-wetland complex featuring vegetated islands and a patchy, shifting mosaic of habitats that developed within two years of restoration of the Creek to its Stage 0 condition. Photo credit: Deschutes Land Trust/Jay Mather.

Figure 3.

Pre- and post-restoration views of part of Canyon Reach 4. (a) pre-project high terrace in 2015. The anthropogenically-relocated, incised, single-thread channel is located within the narrow riparian corridor at the base of the far valley wall. (b) Reconnected , braided channel-floodplain system created by lowering the terrace during summer 2016. (c) Anastomosed river-wetland complex featuring vegetated islands and a patchy, shifting mosaic of habitats that developed within two years of restoration of the Creek to its Stage 0 condition. Photo credit: Deschutes Land Trust/Jay Mather.

Figure 4.

Vegetation study reaches, areas, and transects in Whychus Creek. Flow is from left to right.

Figure 4.

Vegetation study reaches, areas, and transects in Whychus Creek. Flow is from left to right.

Figure 5.

Dying ponderosa pines (Pinus ponderosa) observed following restoration of Canyon Reach 4 that fully reconnected the anthropogenically-incised stream to its floodplain and rehydrated the hyporheic, alluvial aquifer; raising the water table to near the floodplain surface within a few days.

Figure 5.

Dying ponderosa pines (Pinus ponderosa) observed following restoration of Canyon Reach 4 that fully reconnected the anthropogenically-incised stream to its floodplain and rehydrated the hyporheic, alluvial aquifer; raising the water table to near the floodplain surface within a few days.

Figure 6.

Comparison of box plots and Kruskal-Wallace test statistics for (a) normalised abundance (% of total plant cover) and (b) species richness (number of plant species) for all the plants recorded at ‘Canyon Reach 4’ in the 2015 and 2018 transect surveys. Statistically-significant differences (95% level of confidence, p<=0.05) are displayed in italics. Data used to prepare this plot may be found in Appendix 1 in the

Supplementary Materials.

Figure 6.

Comparison of box plots and Kruskal-Wallace test statistics for (a) normalised abundance (% of total plant cover) and (b) species richness (number of plant species) for all the plants recorded at ‘Canyon Reach 4’ in the 2015 and 2018 transect surveys. Statistically-significant differences (95% level of confidence, p<=0.05) are displayed in italics. Data used to prepare this plot may be found in Appendix 1 in the

Supplementary Materials.

Figure 7.

Comparative box plots and Kruskal-Wallace test statistics for pooled, normalised wetland plant abundance (expressed as percentage of total plant cover) along all transects in ‘Canyon Reach 4’ prior to (2015) and post-restoration (2018). Wetland plants are those with indicator status OBL and FACW. Statistically-significant differences (95% level of confidence, p<=0.05) are displayed in italics. Data is found in Appendix 1 in the

Supplementary Materials.

Figure 7.

Comparative box plots and Kruskal-Wallace test statistics for pooled, normalised wetland plant abundance (expressed as percentage of total plant cover) along all transects in ‘Canyon Reach 4’ prior to (2015) and post-restoration (2018). Wetland plants are those with indicator status OBL and FACW. Statistically-significant differences (95% level of confidence, p<=0.05) are displayed in italics. Data is found in Appendix 1 in the

Supplementary Materials.

Figure 8.

Comparative box plots and Kruskal-Wallace test statistics for pooled, normalised upland plant abundance (expressed as percentage of total plant cover) along all transects in ‘Canyon Reach 4’ prior to restoration (2015) and post-restoration (2018). Upland plants are those with indicator status FACU or UPL. Statistically-significant differences (95% level of confidence, p<=0.05) are displayed in italics. Data are listed in Appendix 1 in the Supplementary materials.

Figure 8.

Comparative box plots and Kruskal-Wallace test statistics for pooled, normalised upland plant abundance (expressed as percentage of total plant cover) along all transects in ‘Canyon Reach 4’ prior to restoration (2015) and post-restoration (2018). Upland plants are those with indicator status FACU or UPL. Statistically-significant differences (95% level of confidence, p<=0.05) are displayed in italics. Data are listed in Appendix 1 in the Supplementary materials.

Figure 9.

Comparative box plots and Kruskal-Wallace test statistics for species richness for plants rated as (a) Native, (b) Non-native, (c) FACW=Facultative Wetland or OBL=Obligate Wetland, (d) FACU=Facultative Upland, (e) FACW=Facultative Wetland, or (f) OBL=Obligate Wetland. Statistically-significant differences (95% level of confidence, p<=0.05) are displayed in italics.

Figure 9.

Comparative box plots and Kruskal-Wallace test statistics for species richness for plants rated as (a) Native, (b) Non-native, (c) FACW=Facultative Wetland or OBL=Obligate Wetland, (d) FACU=Facultative Upland, (e) FACW=Facultative Wetland, or (f) OBL=Obligate Wetland. Statistically-significant differences (95% level of confidence, p<=0.05) are displayed in italics.

Figure 10.

Comparative box plots and Kruskal-Wallace test statistics for changes in the percentage covers of (a) bare ground (BG), (b) large wood (LW), (c) litter, (d) moss, and (e) exposed bedrock.

Figure 10.

Comparative box plots and Kruskal-Wallace test statistics for changes in the percentage covers of (a) bare ground (BG), (b) large wood (LW), (c) litter, (d) moss, and (e) exposed bedrock.

Table 1.

DAFOR scale for relative plant abundance (modified from Hearnshaw and Hughey (2010).