Submitted:

21 October 2025

Posted:

23 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

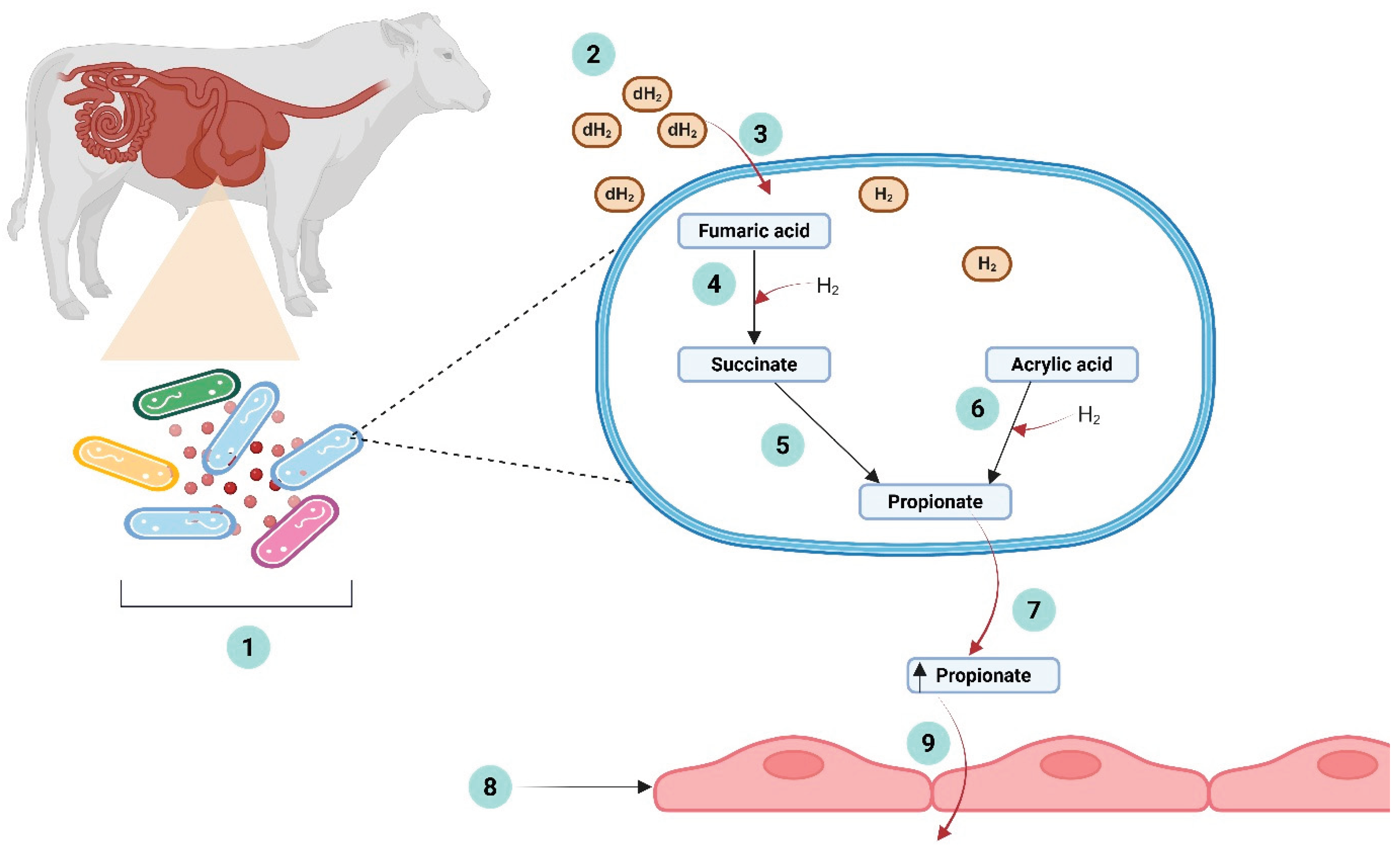

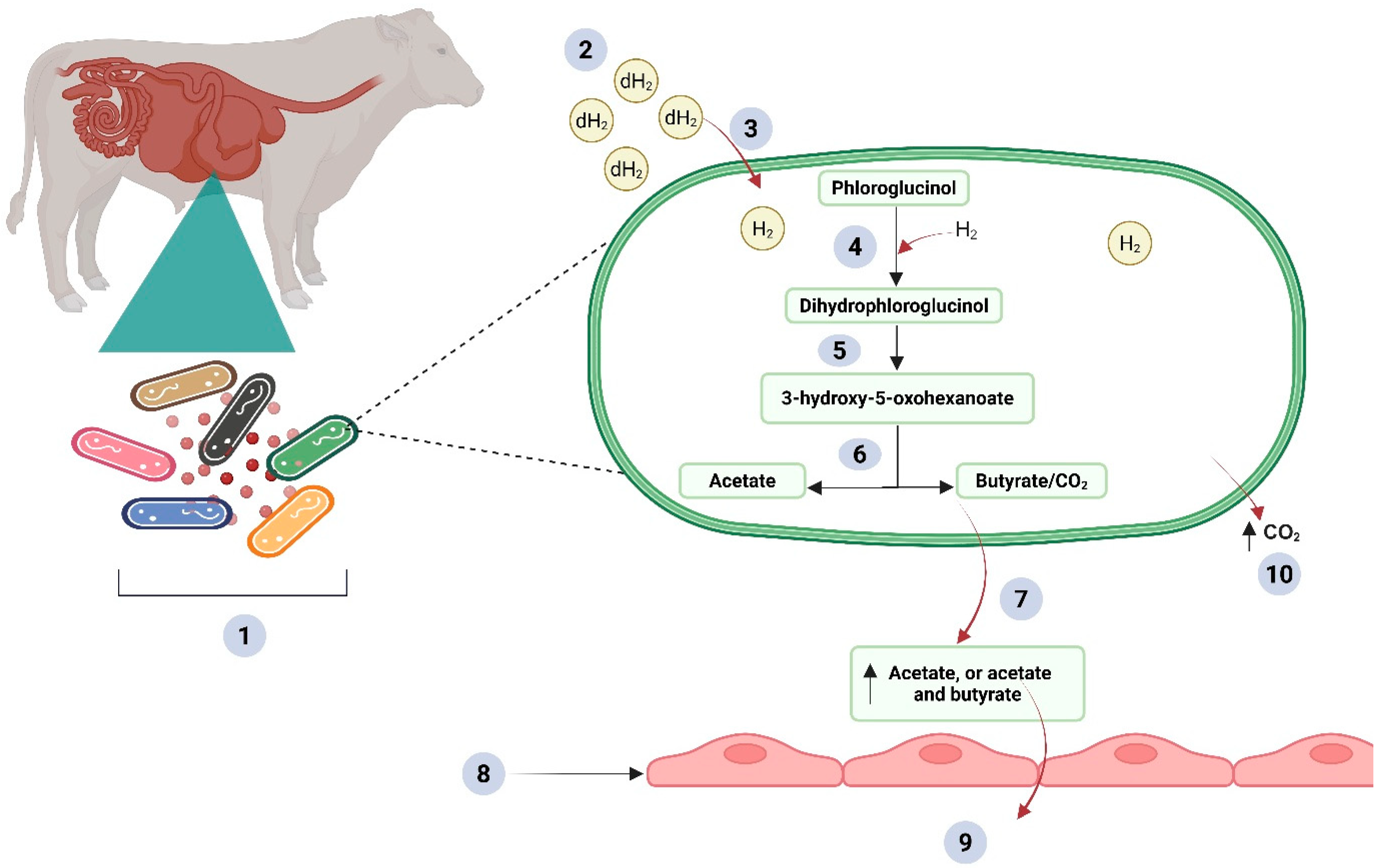

Enteric methane (CH4) emissions from ruminants contribute significantly to agricultural greenhouse gases. Anti-methanogenic feed additives (AMFA), such as Asparagopsis spp. and 3-nitrooxypropanol (3-NOP), reduce CH4 emissions by inhibiting methanogenic enzymes. However, CH4 inhibition often leads to dihydrogen (H2) accumulation, which can impact rumen fermentation and decrease dry matter intake (DMI). Recent studies suggest that co-supplementation of CH4 inhibitors with alternative electron acceptors, such as phloroglucinol, fumaric acid, or acrylic acid, can redirect excess H2 during methanogenesis inhibition into fermentation products nutritionally beneficial for the host. This review summarises findings from rumen simulation experiments and in vivo trials that have investigated the effects of combining a CH4 inhibitor with an alternative H2 acceptor to achieve effective inhibition of methanogenesis. These trials demonstrate variable outcomes depending on additive combinations, inclusion rates, and adaptation periods. The use of phloroglucinol in vivo consistently decreased H2 emissions and altered fermentation patterns, promoting acetate production, compared to the co-supplementation with fumaric acid or acrylic acid as an alternative electron acceptor. As a proof of concept, phloroglucinol shows promise as a co-supplement for reducing CH4 and H2 emissions and enhancing volatile fatty acid profiles in vivo. Optimising microbial pathways for H2 utilisation through targeted co-supplementation and microbial adaptation could enhance the sustainability of CH4 mitigation strategies using feed additive inhibitors in ruminants. Further research using multi-omics analyses is needed to understand microbial dynamics and improve the efficacy of CH4 inhibitor interventions with an alternative H2 acceptor co-supplementation in vivo.

Keywords:

Background

Integrated Approach: Co-Supplementation of a Methane Inhibitor with an Alternative H2 Acceptor In Vitro and In Vivo

Potentials of H2 Acceptor Co-Supplementation for Enhanced Methanogenesis Inhibition

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Amgarten, M.; Schatzmann, H. J.; Wuthrich, A. ‘Lactate type’ response of ruminal fermentation to chloral hydrate, chloroform and trichloroethanol. Journal of Veterinary Pharmacology and Therapeutics 1981, 4(3), 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt, C.; Hristov, A. N.; Price, W. J.; McClelland, S. C.; Pelaez, A. M.; Cueva, S. F.; Oh, J.; Dijkstra, J.; Bannink, A.; Bayat, A. R.; Crompton, L. A.; Eugène, M. A.; Enahoro, D.; Kebreab, E.; Kreuzer, M.; McGee, M.; Martin, C.; Newbold, C. J.; Reynolds, C. K.; Yu, Z. Full adoption of the most effective strategies to mitigate methane emissions by ruminants can help meet the 1.5 °C target by 2030 but not 2050. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2022, 119(20). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asanuma, N.; Iwamoto, M.; Hino, T. Effect of the Addition of Fumarate on Methane Production by Ruminal Microorganisms In Vitro. Journal of Dairy Science 1999, 82(4), 780–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battelli, M.; Maigaard, M.; Lashkari, S.; Nørskov, N. P.; Weisbjerg, M. R.; Nielsen, M. O. Combination of methane-inhibitors and hydrogen-acceptors: effects on in vitro rumen fermentation. Italian Journal of Animal Science 2025, 24(1), 2029–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battelli, M.; Nielsen, M. O.; Nørskov, N. P. Dose- and substrate-dependent reduction of enteric methane and ammonia by natural additives in vitro. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beauchemin, K. A.; Ungerfeld, E. M.; Abdalla, A. L.; Alvarez, C.; Arndt, C.; Becquet, P.; Benchaar, C.; Berndt, A.; Mauricio, R. M.; McAllister, T. A.; Oyhantçabal, W.; Salami, S. A.; Shalloo, L.; Sun, Y.; Tricarico, J.; Uwizeye, A.; De Camillis, C.; Bernoux, M.; Robinson, T.; Kebreab, E. Invited review: Current enteric methane mitigation options. Journal of Dairy Science 2022, 105(12), 9297–9326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belanche, A.; Bannink, A.; Dijkstra, J.; Durmic, Z.; Garcia, F.; Santos, F. G.; Huws, S.; Jeyanathan, J.; Lund, P.; Mackie, R. I.; McAllister, T. A.; Morgavi, D. P.; Muetzel, S.; Pitta, D. W.; Yáñez-Ruiz, D. R.; Ungerfeld, E. M. Feed additives for methane mitigation: A guideline to uncover the mode of action of antimethanogenic feed additives for ruminants. Journal of Dairy Science 2025, 108(1), 375–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, L. M.; Blank, R.; Zorn, F.; Wein, S.; Metges, C. C.; Wolffram, S. Ruminal degradation of quercetin and its influence on fermentation in ruminants. Journal of Dairy Science 2015, 98(8), 5688–5698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G. J.; Russell, J. B. Fermentation of peptides and amino acids by a monensin-sensitive ruminal Peptostreptococcus. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 1988, 54(11), 2742–2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, P. K.; Salem, A. Z. M.; Jena, R.; Kumar, S.; Singh, R.; Puniya, A. K. Rumen Microbiology: An Overview. In Rumen Microbiology: From Evolution to Revolution; Springer India, 2015; pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conradt, D.; Hermann, B.; Gerhardt, S.; Einsle, O.; Müller, M. Biocatalytic Properties and Structural Analysis of Phloroglucinol Reductases. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2016, 55(50), 15531–15534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowley, F. C.; Kinley, R. D.; Mackenzie, S. L.; Fortes, M. R. S.; Palmieri, C.; Simanungkalit, G.; Almeida, A. K.; Roque, B. M. Bioactive metabolites of Asparagopsis stabilized in canola oil completely suppress methane emissions in beef cattle fed a feedlot diet. Journal of Animal Science 2024, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- del Prado, A.; Vibart, R. E.; Bilotto, F. M.; Faverin, C.; Garcia, F.; Henrique, F. L.; Leite, F. F. G. D.; Mazzetto, A. M.; Ridoutt, B. G.; Yáñez-Ruiz, D. R.; Bannink, A. Feed additives for methane mitigation: Assessment of feed additives as a strategy to mitigate enteric methane from ruminants—Accounting; How to quantify the mitigating potential of using antimethanogenic feed additives. Journal of Dairy Science 2025, 108(1), 411–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duin, E. C.; Wagner, T.; Shima, S.; Prakash, D.; Cronin, B.; Yáñez-Ruiz, D. R.; Duval, S.; Rümbeli, R.; Stemmler, R. T.; Thauer, R. K.; Kindermann, M. Mode of action uncovered for the specific reduction of methane emissions from ruminants by the small molecule 3-nitrooxypropanol. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2016, 113(22), 6172–6177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durmic, Z.; Duin, E. C.; Bannink, A.; Belanche, A.; Carbone, V.; Carro, M. D.; Crüsemann, M.; Fievez, V.; Garcia, F.; Hristov, A.; Joch, M.; Martinez-Fernandez, G.; Muetzel, S.; Ungerfeld, E. M.; Wang, M.; Yáñez-Ruiz, D. R. Feed additives for methane mitigation: Recommendations for identification and selection of bioactive compounds to develop antimethanogenic feed additives. Journal of Dairy Science 2025, 108(1), 302–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glasson, C. R. K.; Kinley, R. D.; de Nys, R.; King, N.; Adams, S. L.; Packer, M. A.; Svenson, J.; Eason, C. T.; Magnusson, M. Benefits and risks of including the bromoform containing seaweed Asparagopsis in feed for the reduction of methane production from ruminants. Algal Research 2022, 64, 102673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunsalus, R. P.; Romesser, J. A.; Wolfe, R. S. Preparation of coenzyme M analogs and their activity in the methyl coenzyme M reductase system of Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum. Biochemistry 1978, 17(12), 2374–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honan, M.; Feng, X.; Tricarico, J. M.; Kebreab, E. Feed additives as a strategic approach to reduce enteric methane production in cattle: modes of action, effectiveness and safety. Animal Production Science 2021, 62(14), 1303–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Romero, P.; Belanche, A.; Ungerfeld, E. M.; Yanez-Ruiz, D.; Morgavi, D. P.; Popova, M. Evaluating the effect of phenolic compounds as hydrogen acceptors when ruminal methanogenesis is inhibited in vitro – Part 1. Dairy cows. Animal 2023, 17(5), 100788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E. T.; Guan, L. L.; Lee, S. J.; Lee, S. M.; Lee, S. S.; Lee, I. D.; Lee, S. K.; Lee, S. S. Effects of Flavonoid-rich Plant Extracts on In vitro Ruminal Methanogenesis, Microbial Populations and Fermentation Characteristics. Asian-Australasian Journal of Animal Sciences 2015, 28(4), 530–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjeldsen, M. H.; Weisbjerg, M. R.; Larsen, M.; Højberg, O.; Ohlsson, C.; Walker, N.; Hellwing, A. L. F.; Lund, P. Gas exchange, rumen hydrogen sinks, and nutrient digestibility and metabolism in lactating dairy cows fed 3-nitrooxypropanol and cracked rapeseed. Journal of Dairy Science 2024, 107(4), 2047–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizsan, S. J.; Ramin, M.; Chagas, J. C. C.; Halmemies-Beauchet-Filleau, A.; Singh, A.; Schnürer, A.; Danielsson, R. Effects on rumen microbiome and milk quality of dairy cows fed a grass silage-based diet supplemented with the macroalga Asparagopsis taxiformis. Frontiers in Animal Science 2023, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumholz, L. R.; Bryant, M. P. Eubacterium oxidoreducens sp. nov. requiring H2 or formate to degrade gallate, pyrogallol, phloroglucinol and quercetin. Archives of Microbiology 1986, 144(1), 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumholz, L. R.; Crawford, R. L.; Hemling, M. E.; Bryant, M. P. Metabolism of gallate and phloroglucinol in Eubacterium oxidoreducens via 3-hydroxy-5-oxohexanoate. Journal of Bacteriology 1987, 169(5), 1886–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, W.; Yang, C. Ruminal methane production: Associated microorganisms and the potential of applying hydrogen-utilizing bacteria for mitigation. Science of The Total Environment 2019, 654, 1270–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Liu, N.; Cao, Y.; Jin, C.; Li, F.; Cai, C.; Yao, J. Effects of fumaric acid supplementation on methane production and rumen fermentation in goats fed diets varying in forage and concentrate particle size. Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology 2018, 9(1), 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Xu, X.; Cao, Y.; Cai, C.; Cui, H.; Yao, J. Nitrate decreases methane production also by increasing methane oxidation through stimulating NC10 population in ruminal culture. AMB Express 2017, 7(1), 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, L.; Magnusson, M.; Paul, N. A.; Kinley, R.; de Nys, R.; Tomkins, N. Identification of bioactives from the red seaweed Asparagopsis taxiformis that promote antimethanogenic activity in vitro. Journal of Applied Phycology 2016, 28(5), 3117–3126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackie, R. I.; Kim, H.; Kim, N. K.; Cann, I. Invited Review — Hydrogen production and hydrogen utilization in the rumen: key to mitigating enteric methane production. Animal Bioscience 2024, 37(2), 323–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maigaard, M.; Weisbjerg, M. R.; Johansen, M.; Walker, N.; Ohlsson, C.; Lund, P. Effects of dietary fat, nitrate, and 3-nitrooxypropanol and their combinations on methane emission, feed intake, and milk production in dairy cows. Journal of Dairy Science 2024a, 107(1), 220–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maigaard, M.; Weisbjerg, M. R.; Hellwing, A. L. F.; Larsen, M.; Andersen, F. B.; Lund, P. The acute effects of rumen pulse-dosing of hydrogen acceptors during methane inhibition with nitrate or 3-nitrooxypropanol in dairy cows. Journal of Dairy Science 2024b. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Fernandez, G.; Denman, S. E.; Yang, C.; Cheung, J.; Mitsumori, M.; McSweeney, C. S. Methane Inhibition Alters the Microbial Community, Hydrogen Flow, and Fermentation Response in the Rumen of Cattle. Frontiers in Microbiology 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAllister, T. A.; Newbold, C. J. Redirecting rumen fermentation to reduce methanogenesis. Australian Journal of Experimental Agriculture 2008, 48(2), 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melgar, A.; Harper, M. T.; Oh, J.; Giallongo, F.; Young, M. E.; Ott, T. L.; Duval, S.; Hristov, A. N. Effects of 3-nitrooxypropanol on rumen fermentation, lactational performance, and resumption of ovarian cyclicity in dairy cows. Journal of Dairy Science 2020, 103(1), 410–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newbold, C. J.; López, S.; Nelson, N.; Ouda, J. O.; Wallace, R. J.; Moss, A. R. Propionate precursors and other metabolic intermediates as possible alternative electron acceptors to methanogenesis in ruminal fermentation in vitro. British Journal of Nutrition 2005, 94(1), 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olijhoek, D. W.; Hellwing, A. L. F.; Brask, M.; Weisbjerg, M. R.; Højberg, O.; Larsen, M. K.; Dijkstra, J.; Erlandsen, E. J.; Lund, P. Effect of dietary nitrate level on enteric methane production, hydrogen emission, rumen fermentation, and nutrient digestibility in dairy cows. Journal of Dairy Science 2016, 99(8), 6191–6205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, P. R. K.; Hyder, I. Ruminant Digestion. In Textbook of Veterinary Physiology; Springer Nature Singapore, 2023; pp. 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, P.; Huang, R.; Jiménez, E.; Palma-Hidalgo, J. M.; Ungerfeld, E. M.; Popova, M.; Morgavi, D. P.; Belanche, A.; Yáñez-Ruiz, D. R. Evaluating the effect of phenolic compounds as hydrogen acceptors when ruminal methanogenesis is inhibited in vitro – Part 2. Dairy goats. Animal 2023, 17(5), 100789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero, P.; Ungerfeld, E. M.; Popova, M.; Morgavi, D. P.; Yáñez-Ruiz, D. R.; Belanche, A. Exploring the combination of Asparagopsis taxiformis and phloroglucinol to decrease rumen methanogenesis and redirect hydrogen production in goats. Animal Feed Science and Technology 2024, 316, 116060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J. B.; Wallace, R. J. Energy-yielding and energy-consuming reactions. In The Rumen Microbial Ecosystem; Hobson, P. N., Stewart, C. S., Eds.; Springer Netherlands, 1997; pp. 246–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorsteinsson, M.; Lund, P.; Weisbjerg, M. R.; Noel, S. J.; Schönherz, A. A.; Hellwing, A. L. F.; Hansen, H. H.; Nielsen, M. O. Enteric methane emission of dairy cows supplemented with iodoform in a dose–response study. Scientific Reports 2023a, 13(1), 12797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorsteinsson, M.; Maigaard, M.; Lund, P.; Weisbjerg, M. R.; Nielsen, M. O. Effect of fumaric acid in combination with Asparagopsis taxiformis or nitrate on in vitro gas production, pH, and redox potential. JDS Communications 2023b, 4(5), 335–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.-G.; Gates, D. M.; Ingledew, W. M.; Jones, G. A. Products of anaerobic phloroglucinol degradation by Coprococcus sp. Pe15. Canadian Journal of Microbiology 1976, 22(2), 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.-G.; Jones, G. A. Isolation and identification of rumen bacteria capable of anaerobic phloroglucinol degradation. Canadian Journal of Microbiology 1975, 21(6), 794–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungerfeld, E. M. A theoretical comparison between two ruminal electron sinks. Frontiers in Microbiology 2013, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ungerfeld, E. M. Shifts in metabolic hydrogen sinks in the methanogenesis-inhibited ruminal fermentation: a meta-analysis. Frontiers in Microbiology 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ungerfeld, E. M. Metabolic Hydrogen Flows in Rumen Fermentation: Principles and Possibilities of Interventions. Frontiers in Microbiology 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ungerfeld, E. M.; Beauchemin, K. A.; Muñoz, C. Current Perspectives on Achieving Pronounced Enteric Methane Mitigation From Ruminant Production. Frontiers in Animal Science 2022, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungerfeld, E. M.; Kohn, R. A.; Wallace, R. J.; Newbold, C. J. A meta-analysis of fumarate effects on methane production in ruminal batch cultures. Journal of Animal Science 2007, 85(10), 2556–2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Lingen, H. J.; Plugge, C. M.; Fadel, J. G.; Kebreab, E.; Bannink, A.; Dijkstra, J. Thermodynamic Driving Force of Hydrogen on Rumen Microbial Metabolism: A Theoretical Investigation. PLOS ONE 2016, 11(10), e0161362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zijderveld, S. M.; Gerrits, W. J. J.; Dijkstra, J.; Newbold, J. R.; Hulshof, R. B. A.; Perdok, H. B. Persistency of methane mitigation by dietary nitrate supplementation in dairy cows. Journal of Dairy Science 2011, 94(8), 4028–4038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasson, D. E.; Yarish, C.; Hristov, A. N. Enteric methane mitigation through Asparagopsis taxiformis supplementation and potential algal alternatives. Frontiers in Animal Science 2022, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolin, M. J. The Rumen Fermentation: A Model for Microbial Interactions in Anaerobic Ecosystems; 1979; pp. 49–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolin, M. J.; Miller, T. L.; Stewart, C. S. Microbe-microbe interactions. In The Rumen Microbial Ecosystem; Springer Netherlands, 1997; pp. 467–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, J. M.; Kennedy, F. Scott.; Wolfe, R. S. Reaction of multihalogenated hydrocarbons with free and bound reduced vitamin B12. Biochemistry 1968, 7(5), 1707–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Type of study, duration | AMFA | Dose | Animals | Feed substrate | CH4 production/emission (%) | H2 accumulation/emission (%) | Acetate proportion (%) | Propionate proportion (%) | A:P ratio (%) | Total VFA (%) | DMI (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Huang et al., 2023 | In vitro, 24 h | AT | 1.5% DM | In vitro culture* | High fiber substrate | - 22 (c. C) | + 104 (c. C) | - 13 (c. C) | + 12 (c. C) | - 21 (c. C) | - 9 (c. C) | N.A |

| In vitro, 24 h | AT + Phl | 1.5% + 6 mM | In vitro culture* | High fiber substrate | - 38 (c. C) | + 150 (n.s 1.5% AT) | + 7 (n.s 1.5% AT) | - 11 (n.s 1.5% AT) | + 35 (n.s 1.5% AT) | + 17 (s.s 1.5% AT) | N.A | |

| In vitro, 24 h | AT | 2.5% DM | In vitro culture* | High fiber substrate | - 76 (c. C) | + 541 (c. C) | - 32 (c. C) | + 35 (c. C) | - 47 (c. C) | - 22 (c. C) | N.A | |

| In vitro, 24 h | AT + Phl | 2.5% + 6 mM | In vitro culture* | High fiber substrate | - 94 (c. C) | + 10 (s.s 2.5% AT) | + 41 (s.s 2.5% AT) | - 24 (s.s 2.5% AT) | + 68 (s.s 2.5% AT) | + 18 (s.s 2.5% AT) | N.A | |

| In vitro, 24 h | BES | 3 μM | In vitro culture* | High fiber substrate | - 51 (c. C) | + 5,733 (c. C) | - 26 (c. C) | + 33 (c. C) | - 45 (c. C) | + 2 (c. C) | N.A | |

| In vitro, 24 h | BES + Phl | 3 μM + 6 mM | In vitro culture* | High fiber substrate | - 46 (c. C) | - 36 (n.s BES) | + 35 (s.s BES) | - 33 (s.s BES) | + 102 (s.s BES) | + 11 (s.s BES) | N.A | |

| In vitro, 96 h | BES | 3 μM | In vitro culture* | High fiber substrate | - 70 (c. C) | + 931 (c. C) | - 7 (c. C) | + 7 (c. C) | - 21 (c. C) | - 6 (c. C) | N.A | |

| In vitro, 96 h | BES + Phl | 3 μM + 36 mM | In vitro culture* | High fiber substrate | - 100 (c. C) | - 72 (s.s BES) | + 42 (s.s BES) | - 86 (s.s BES) | + 752 (s.s BES) | + 77 (s.s BES) | N.A | |

| In vitro, 94 h | Phl | 36 mM | In vitro culture* | High fiber substrate | - 99.7 (c. C) | - 62 (s.s BES) | + 38 (s.s BES) | - 85 (s.s BES) | + 791 (s.s BES) | + 69 (s.s BES) | N.A | |

| Romero et al., 2023 | In vitro, 24 h | AT | 1% DM | In vitro culturea | High fiber substrate | - 94 (s.s C) | plus 779 (n.s C) | - 13 (s.s C) | + 33 (s.s C) | - 34 (s.s C) | - 7 (n.s C) | N.A |

| In vitro, 24 h | AT | 2% DM | In vitro culturea | High fiber substrate | - 99 (s.s C) | + 3,650 (s.s C) | - 14 (s.s C) | + 33 (s.s C) | - 19 (s.s C) | - 4 (n.s C) | N.A | |

| In vitro, 24 h | AT | 3% DM | In vitro culturea | High fiber substrate | - 100 (s.s C) | + 5,793 (s.s C) | - 15 (s.s C) | + 36 (s.s C) | - 38 (s.s C) | - 7 (n.s C) | N.A | |

| In vitro, 24 h | AT | 4% DM | In vitro culturea | High fiber substrate | - 100 (s.s C) | + 10,257 (s.s C) | - 15 (s.s C) | + 35 (s.s C) | - 37 (s.s C) | - 7 (n.s C) | N.A | |

| In vitro, 24 h | AT | 5% DM | In vitro culturea | High fiber substrate | - 100 (s.s C) | + 7,007 (s.s C) | - 15 (s.s C) | + 35 (s.s C) | - 37 (s.s C) | - 8 (n.s C) | N.A | |

| In vitro, 5 d | AT | 2% DM | In vitro culturea | High fiber substrate | - 99 (c. C) | + 1,450 (c. C) | - 12 (s.s C) | + 15 (s.s C) | - 23 (c. C) | - 18 (c. C) | N.A | |

| In vitro, 5 d | AT + Phl | 2% + 6 mM | In vitro culturea | High fiber substrate | - 100 (c. C) | - 37 (n.s 2% AT) | + 8 (s.s 2% AT) | - 18 (s.s 2% AT) | + 31 (s.s 2% AT) | + 18 (s.s 2% AT) | N.A | |

| In vitro, 5 d | AT | 2% DM | In vitro culturea | High fiber substrate | - 99 (s.s C) | + 2, 323 (s.s C) | - 13 (s.s C) | + 14 (s.s C) | - 23 (s.s C) | - 14 (s.s C) | N.A | |

| In vitro, 5 d | AT + Phl | 2% + 6 mM | In vitro culturea | High fiber substrate | - 100 (s.s C) | - 27 (s.s 2% AT) | + 10 (s.s 2% AT) | - 17 (s.s 2% AT) | + 33 (n.s 2% AT) | + 27 (s.s 2% AT) | N.A | |

| In vitro, 5 d | AT + Phl | 2% + 16 mM | In vitro culturea | High fiber substrate | - 100 (s.s C) | - 49 (s.s 2% AT) | + 22 (s.s 2% AT) | - 44 (s.s 2% AT) | + 121 (s.s 2% AT) | + 71 (s.s 2% AT) | N.A | |

| In vitro, 5 d | AT + Phl | 2% + 26 mM | In vitro culturea | High fiber substrate | - 100 (s.s C) | - 63 (s.s 2% AT) | + 32 (s.s 2% AT) | - 66 (s.s 2% AT) | + 292 (s.s 2% AT) | + 88 (s.s 2% AT) | N.A | |

| In vitro, 5 d | AT + Phl | 2% + 36 mM | In vitro culturea | High fiber substrate | - 100 (s.s C) | - 46 (s.s 2% AT) | + 34 (s.s 2% AT) | - 70 (s.s 2% AT) | + 354 (s.s 2% AT) | + 99 (s.s 2% AT) | N.A | |

| Thorsteinsson et al., 2023b | In vitro, 24 h | Nit | 0.05 g | In vitro cultureb | High fiber substrate | - 56 (s.s C) | + 0.00 (n.s C) | N.D | N.D | N.D | N.D | N.A |

| In vitro, 24 h | AT | 0.05 g | In vitro cultureb | High fiber substrate | - 98 (s.s C) | + 202 (n.s C) | N.D | N.D | N.D | N.D | N.A | |

| In vitro, 24 h | Nit + FA | 0.05 g + 0.05 g | In vitro cultureb | High fiber substrate | - 47 (s.s C) | + 0.00 (n.s C) | N.D | N.D | N.D | N.D | N.A | |

| In vitro, 24 h | AT + FA | 0.05 g + 0.05 g | In vitro cultureb | High fiber substrate | - 98 (s.s C) | + 211 (n.s C) | N.D | N.D | N.D | N.D | N.A | |

| In vitro, 36 h | Nit | 0.05 g | In vitro cultureb | High fiber substrate | - 52 (s.s C) | + 0.00 (n.s C) | N.D | N.D | N.D | N.D | N.A | |

| In vitro, 36 h | AT | 0.05 g | In vitro cultureb | High fiber substrate | - 99 (s.s C) | + 82 (n.s C) | N.D | N.D | N.D | N.D | N.A | |

| In vitro, 36 h | Nit + FA | 0.05 g + 0.05 g | In vitro cultureb | High fiber substrate | - 46 (s.s C) | + 0.00 (n.s C) | N.D | N.D | N.D | N.D | N.A | |

| In vitro, 36 h | AT + FA | 0.05 g + 0.05 g | In vitro cultureb | High fiber substrate | - 99 (s.s C) | + 136 (n.s C) | N.D | N.D | N.D | N.D | N.A | |

| In vitro, 48 h | Nit | 0.05 g | In vitro cultureb | High fiber substrate | - 61 (s.s C) | + 0.00 (n.s C) | N.D | N.D | N.D | N.D | N.A | |

| In vitro, 48 h | AT | 0.05 g | In vitro cultureb | High fiber substrate | - 99 (s.s C) | + 124 (n.s C) | N.D | N.D | N.D | N.D | N.A | |

| In vitro, 48 h | Nit + FA | 0.05 g + 0.05 g | In vitro cultureb | High fiber substrate | - 55 (s.s C) | + 0.00 (n.s C) | N.D | N.D | N.D | N.D | N.A | |

| In vitro, 48 h | AT + FA | 0.05 g + 0.05 g | In vitro cultureb | High fiber substrate | - 99 (s.s C) | + 176 (n.s C) | N.D | N.D | N.D | N.D | N.A | |

| Battelli et al., 2025 | In vitro, 24 h | IOD | 0.007% DM | In vitro cultureb | High fiber substrate | - 62 (s.s C) | + 4,803 (s.s C) | - 7 (s.s C)c | + 23 (s.s C)c | - 25 (s.s C) | + 3 (s.s C) | N.A |

| In vitro, 24 h | QUE | 3% DM | In vitro cultureb | High fiber substrate | - 19 (s.s C) | - 19 (n.s C) | + 2 (s.s C)c | - 2 (s.s C)c | + 4 (s.s C) | - 3 (s.s C) | N.A | |

| In vitro, 24 h | ACP | 5% DM | In vitro cultureb | High fiber substrate | - 0.8 (s.s C) | - 35 (n.s C) | + 2 (s.s C)c | - 6 (s.s C)c | + 6 (s.s C) | - 0.9 (s.s C) | N.A | |

| In vitro, 24 h | Phl | 23% DM | In vitro cultureb | High fiber substrate | + 4 (s.s C) | + 3 (n.s C) | + 17 (s.s C)c | - 37 (s.s C)c | + 82 (s.s C) | + 42 (s.s C) | N.A | |

| In vitro, 24 h | VitE | 0.45% DM | In vitro cultureb | High fiber substrate | + 35 (s.s C) | + 26 (n.s C) | + 6 (s.s C)c | - 24 (s.s C)c | + 39 (s.s C) | + 9 (s.s C) | N.A | |

| In vitro, 24 h | IOD + ACP | 0.007% + 5% | In vitro cultureb | High fiber substrate | + 0.00 (s.s C) | + 835 (s.s C) | + 1 (n.s C)c | + 2 (n.s C)c | - 2 (n.s C) | + 10 (s.s C) | N.A | |

| In vitro, 24 h | IOD + Phl | 0.007% + 23% | In vitro cultureb | High fiber substrate | - 68 (s.s C) | + 8,416 (s.s C) | + 9 (s.s C)c | - 19 (s.s C)c | + 31 (s.s C) | + 46 (s.s C) | N.A | |

| In vitro, 24 h | IOD + VitE | 0.007% + 0.45% | In vitro cultureb | High fiber substrate | - 63 (s.s C) | + 4,965 (s.s C) | - 5 (s.s C)c | + 17 (s.s C)c | - 13 (s.s C) | + 3 (n.s C) | N.A | |

| In vitro, 24 h | QUE + ACP | 3% + 5% | In vitro cultureb | High fiber substrate | - 6 (s.s C) | - 13 (n.s C) | + 3 (s.s C)c | - 5 (s.s C)c | + 6 (s.s C) | - 0.7 (s.s C) | N.A | |

| In vitro, 24 h | QUE + Phl | 3% + 23% | In vitro cultureb | High fiber substrate | - 32 (s.s C) | + 2,019 (s.s C) | + 16 (s.s C)c | - 31 (s.s C)c | + 68 (s.s C) | + 40 (s.s C) | N.A | |

| In vitro, 24 h | QUE + VitE | 3% + 0.45% | In vitro cultureb | High fiber substrate | + 0.00 (s.s C) | + 26 (n.s C) | + 7 (s.s C)c | - 20 (s.s C)c | + 31 (s.s C) | + 5 (s.s C) | N.A | |

| In vitro, 24 h | IOD + QUE | 0.007% + 3% | In vitro cultureb | High fiber substrate | - 98 (s.s C) | + 1,642 (s.s C) | - 2 (s.s C)c | + 11 (s.s C)c | - 13 (s.s C) | + 0.00 (n.s C) | N.A | |

| In vitro, 24 h | IOD + QUE + ACP | 0.007 + 3 + 5% | In vitro cultureb | High fiber substrate | - 82 (s.s C) | + 952 (s.s C) | - 0.8 (n.s C)c | + 7 (s.s C)c | - 9 (s.s C) | + 3 (s.s C) | N.A | |

| In vitro, 24 h | IOD + QUE + Phl | 0.007 + 3 + 23% | In vitro cultureb | High fiber substrate | - 96 (s.s C) | + 2,932 (s.s C) | + 13 (s.s C)c | - 24 (s.s C)c | + 46 (s.s C) | + 42 (s.s C) | N.A | |

| In vitro, 24 h | IOD + QUE + VitE | 0.007 + 3 + 0.45% | In vitro cultureb | High fiber substrate | - 98 (s.s C) | + 1,271 (s.s C) | - 2 (s.s C)c | + 9 (s.s C)c | - 11 (s.s C) | + 0.3 (n.s C) | N.A | |

| Maigaard et al., 2024b | In vivo, N.S | Nit + FA | 15 g/kg DM + 390 g/d | Lactating cows | High forage | - 2 (n.s C) | - 36 (n.s C) | - 2 (s.s C) | + 6 (n.s C) | - 6 (n.s C) | + 0.00 (n.s C) | + 5 (s.s C) |

| In vivo, N.S | Nit + AA | 15 g/kg DM + 242 g/d | Lactating cows | High forage | - 4 (n.s C) | - 47 (n.s C) | + 4 (s.s C) | + 6 (n.s C) | - 0.4 (n.s C) | - 7 (s.s C) | - 11 (s.s C) | |

| In vivo, N.S | Nit + FA + AA | 15 g/kg DM + 195 g + 121 g/d | Lactating cows | High forage | + 3 (n.s C) | - 37 (n.s C) | + 1 (n.s C) | + 5 (n.s C) | - 3 (n.s C) | - 2 (s.s C) | + 4 (s.s C) | |

| In vivo, N.S | 3-NOP + FA | 60 mg/kg DM + 390 g/d | Lactating cows | High forage | - 21 (s.s C) | - 11 (n.s C) | - 3 (n.s C) | + 13 (s.s C) | - 16 (s.s C) | - 3 (n.s C) | - 6 (n.s C) | |

| In vivo, N.S | 3-NOP + AA | 60 mg/kg DM + 242 g/d | Lactating cows | High forage | - 50 (s.s C) | + 18 (n.s C) | - 0.7 (n.s C) | + 21 (s.s C) | - 18 (s.s C) | - 15 (s.s C) | - 24 (s.s C) | |

| In vivo, N.S | 3-NOP + Phl | 60 mg/kg DM + 480 g/d | Lactating cows | High forage | - 35 (s.s C) | - 3 (n.s C) | + 0.6 (n.s C) | + 0.00 (n.s C) | - 0.4 (n.s C) | - (n.s C) | - 5 (n.s C) | |

| Romero et al., 2024 | In vivo, 14 d | Phl | 20 g/kg DM/d | Dairy goats | High forage | - 7 (c. C) | - 34 (n.s C) | + 9 (s.s C) | - 16 (s.s C) | + 30 (s.s C) | - 4 (n.s C) | - 1 (n.s C) |

| In vivo, 14 d | AT | 5 g/kg DM/d | Dairy goats | High forage | - 40 (c. C) | + 4,383 (s.s C) | - 11 (s.s C) | + 33 (s.s C) | - 30 (s.s C) | - 5 (n.s C) | - 6 (n.s C) | |

| In vivo, 14 d | AT + Phl | 5 g + 20 g/kg DM/d | Dairy goats | High forage | - 47 (c. C) | - 68 (s.s AT) | + 11.8 (n.s AT) | - 22 (n.s AT) | + 39 (n.s AT) | + 6 (n.s AT) | + 1 (n.s AT) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).