1. Introduction

Mental health is emerging as a critical issue in the public health and educational-preventive field: the prevalence of mental health issues is rising, becoming one of the most pressing global health concerns facing modern society (Hussain et al., 2018). Within this field, university students represent a particularly important sub-population (Browning et al., 2021; Vargas-Huicochea et al., 2022; Wahed & Hassan, 2017). Blanco et al. (2008) reported that university students show lower levels of mental health than their non-university peers. Over the past two decades, the prevalence and severity of mental health problems among university students have risen globally, alongside an increase in help-seeking behaviors (Hunt & Eisenberg, 2010; Lipson et al., 2019). Studies attempting to explain these data argue that mental health problems became especially pronounced during the COVID-19 pandemic (Chen & Lucock, 2022) and have continued afterward due to post-pandemic effects (Nizzolino & Canals, 2023). On the other hand, several studies have attributed this trend to cultural shifts and policy-related stressors that increase psychological pressure among university students (Deb et al., 2016; Levecque et al., 2017).

In this sense, postgraduate students are at even greater risk, as they experience a specific “in-between condition”, situated between academic life, the approaching completion of their studies, and the transition into the job market. They must therefore face expectations about the future and feelings of uncertainty, occupying an “in-between position” that can become a source of anxiety and is typical of postgraduate learners (Morris, 2021).

Mental health is broadly defined as the capacity for positive and effective mental functioning (Hersi et al., 2017), a state of well-being in which an individual realizes their potential and is able to cope with normal life stressors (Lal et al., 2014). According to Veit and Ware (1983), mental health encompasses both the dimensions of psychological well-being and psychological distress. Overall, mental health is expressed through a person’s positive functioning within themselves (intrapersonal) and in relationships with others (interpersonal), including self-perceptions of personal growth, mastery, and connection (Burns, 2016).

To understand the psychological resources that buffer these challenges, recent research has focused on existential constructs such as meaning in life. Meaning in life has been defined as people’s subjective judgments—or the sense—that one’s life is marked by coherence, purpose, and significance (Heintzelman & King, 2014; Steger, 2022), or the capacity to make sense of one’s life and perceive predictability and consistency (Steger, 2022). According to Steger et al. (2006), the construct includes both the presence of meaning and the search for meaning. Meaning in life has emerged as a key factor in psychological functioning, acknowledged as a vital component of overall health, predicting mental functioning across the continuum—from the prevention of psychological distress to the promotion of psychological well-being (Steger, 2022). Among university students, meaning in life serves as a protective factor against psychosomatic symptoms (Wang et al., 2016) and is associated with higher mental health (Wu et al., 2013); conversely, a lack of meaning in life has been linked to depression and poor psychological functioning (Carreno et al., 2020; Huo et al., 2020).

The importance of meaning was first proposed within the existential framework pioneered by Viktor Frankl and Rollo May, who considered the capacity to find purpose and significance—even in the face of suffering—as central to human flourishing. More recently, the framework of self-transcendence and existential positive psychology, as proposed by Stellar and colleagues, integrates these existential insights with contemporary empirical research on positive functioning. According to this perspective, self-transcendent qualities—such as the ability to focus beyond one’s immediate needs, appreciate what one has, and find purpose in life—enhance resilience and protect against psychological distress. These frameworks converge on the idea that meaning in life is a central mechanism through which individuals can navigate adversity, promote psychological well-being, and cultivate enduring personal growth.

Gratitude, forgiveness, and spirituality can be conceptualized as self-transcendent traits, sharing a common feature: they orient individuals beyond the self, fostering connection with others, acceptance of life circumstances, and a sense of higher purpose. Within the framework of existential positive psychology, such constructs are hypothesized to enhance meaning in life, which in turn supports psychological well-being and mitigates distress.

Gratitude has been described as a self-transcendent emotion and attitude—a life orientation toward perceiving and appreciating good things in one’s life and the positive aspects of the world, even in difficult circumstances (McCullough et al., 2008; Stellar et al., 2017). Gratitude has been linked to various positive outcomes, including enhanced well-being and reduced symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress (Bohlmeijer et al., 2021; Cregg & Cheavens, 2021). Research with student populations has also confirmed correlations between gratitude and both reduced depressive symptoms and increased well-being (Guse et al., 2019; Măirean et al., 2019; Mason, 2019; Sapmaz et al., 2016). Previous research by Cregg and Cheavens (2021) also supports the link between gratitude and mental health in university populations.

Forgiveness, as defined by Rye and Pargament (2002), involves the process of letting go of negative feelings (e.g., resentment), thoughts (e.g., retribution), and behaviors (e.g., hostility) in response to wrongdoing, replacing them with compassion. Forgiveness is a multifaceted phenomenon that can be directed toward various targets: oneself (self-forgiveness), others, or situations (Thompson et al., 2005). Forgiveness has consistently been found to negatively correlate with depression and psychological distress, and positively correlate with well-being (Fincham & May, 2021). Kravchuk (2022) identified forgiveness as a significant predictor of mental health in university students.

Spirituality is another key construct linked to mental health. Spirituality is considered a universal aspect of human experience—a fundamental part of being human, not dependent on specific beliefs or religious affiliations—through which individuals seek ultimate meaning, purpose, and transcendence, experiencing connectedness to themselves, others, nature, and the significant or sacred (Long et al., 2024; Wüthrich-Grossenbacher, 2024). Spirituality plays a role in promoting psychological resilience, well-being (Garssen et al., 2021; Jeny & Varghese, 2013), and mental health (Holder et al., 2016; Litalien et al., 2022). In recent years, several studies have emphasized the need to integrate spiritual factors into public health and medicine (Long et al., 2024). Previous literature has also shown that spiritual practices enhance overall well-being in university students (de Diego Cordero et al., 2019; Khan, 2015; Negi et al., 2021).

Previous research has found meaning in life to be positively associated with gratitude (Oriol et al., 2020), forgiveness (Głaz, 2019), and spirituality (Yoon et al., 2021). It has also been studied as a mediator in the relationships between mental health factors and gratitude, resilience, hope, and self-acceptance (Halama & Dedova, 2007; Karaman et al., 2020; Zhou & Xu, 2019), and between gratitude and life satisfaction (Datu & Mateo, 2015), gratitude and suicidal ideation (Kleiman et al., 2013), and spirituality and mental health (Sargent, 2015). Previous studies have identified associations between gratitude, forgiveness, and spirituality and mental health (Bali et al., 2022; Chakradhar et al., 2023; Costa et al., 2021; Davis et al., 2015; Gungor et al., 2021; Kim et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2018). Moreover, the concept of meaning in life has been explored as a mediating factor between constructs such as gratitude and life satisfaction (Datu & Mateo, 2015), resilience and life satisfaction (Karaman et al., 2020), and nature connectedness and well-being (Howell et al., 2013).

Despite these numerous findings, there is a paucity of research investigating the relationship between meaning in life and self-transcendent traits among postgraduate students. This is a relevant issue, as postgraduate students represent a particularly vulnerable population amid the global rise in mental health challenges. University life involves complex challenges, yet a flexible mindset and effective coping strategies can make the academic path more sustainable—especially by fostering the capacity to find meaning within complexity.

This is even more true in developing countries such as Pakistan, where contextual, institutional, and personal factors intersect to heighten psychological vulnerability. However, despite increasing global attention, mental health remains a relatively neglected field among university students in Pakistan (Saleem et al., 2013). Mental health concerns are prevalent among Pakistani students, with studies indicating high levels of psychological distress (Ghayas et al., 2014; Jibeen, 2016). Bibi et al. (2021) reported a high prevalence of poor mental health and suicidal ideation among Pakistani university students. A systematic review by (Khan et al., 2021) found a 42.66% prevalence of depressive symptoms, suggesting that nearly half of Pakistani university students experience mental health challenges.

In recent years, a socio-cultural transformation has been occurring in postgraduate education in Southeast Asia, including Pakistan, characterized by a growing number of students pursuing advanced degrees and an increasing demand for such programs. Many students relocate for their studies, often facing culture shock, language barriers, and financial strain due to tuition and living costs. They also confront the challenge of adapting to more independent learning environments while balancing work and study. These experiences require students to develop key skills such as time management, self-discipline, and resilience to overcome academic, personal, and professional difficulties (Kaur & Sidhu, 2009).

Notably, there is a lack of research on the mental health of postgraduate students in Pakistan, particularly regarding its association with gratitude, forgiveness, and spirituality. Furthermore, no studies have explored the mediating role of meaning in life in these relationships within this population. Building upon prior studies that identified meaning in life as a mediator between positive traits (e.g., gratitude, spirituality, resilience) and mental health outcomes (Datu & Mateo, 2015; Karaman et al., 2020), the present study aims to extend this framework to postgraduate students in Pakistan.

In response to these gaps, drawing on existential positive psychology framework, the present study proposes that self-transcendent traits (gratitude, forgiveness, and spirituality) enhance mental health through the cultivation of meaning in life.

Based on the literature reviewed, the following hypotheses were proposed:

H1: Higher levels of gratitude, forgiveness, and spirituality will be associated with higher levels of psychological well-being and overall mental health among postgraduate university students.

H2: Higher levels of gratitude, forgiveness, and spirituality will be associated with lower levels of psychological distress among postgraduate university students.

H3: Meaning in life will mediate the relationship between gratitude, forgiveness, and spirituality and mental health among postgraduate university students.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

In the current study, a total of 1,527 postgraduate university students were recruited using a probability-based multistage random sampling technique. The sampling process was conducted in four stages. In the first stage, stratified random sampling was used to select ten public sector universities from the nine administrative divisions of the Punjab province, Pakistan. These included: Lahore Division: University of the Punjab and Lahore College for Women University; Faisalabad Division: Government College University Faisalabad; Rawalpindi Division: Arid Agriculture University; Gujranwala Division: University of Gujrat; Sahiwal Division: University of Sahiwal; Bahawalpur Division: The Islamia University of Bahawalpur; Multan Division: Bahauddin Zakariya University; Sargodha Division: University of Sargodha; Dera Ghazi Khan Division: Ghazi University. Two universities were selected from the Lahore Division, the capital and most densely populated region of Punjab. According to the Economic Survey of Pakistan, approximately 60% of the country's population (110 million people) resides in Punjab, while the remaining 40% lives across the other three provinces (Dar & Wasti, 2017).

As larger strata require proportionally larger samples (Scheaffer et al., 1990), the sample was drawn from ten universities within Punjab. In the second stage, stratified random sampling was applied to select three academic faculties from each university. These were: Faculty of Science; Faculty of Arts and Humanities; Faculty of Social Sciences. These faculties were selected from a total of six available faculties (including Medical, Agriculture, and Engineering) to enhance generalizability across disciplines most relevant to the study. In the third stage, three academic departments were selected from each of the three chosen faculties within each university, resulting in nine departments per university. The departments selected were: Faculty of Science: Mathematics, Physics, Chemistry; Faculty of Arts and Humanities: English, Urdu, Islamic Studies; Faculty of Social Sciences: Psychology, Economics, and Social Work/Sociology.

In the fourth and final stage, simple random sampling was employed to select 20 postgraduate students (Master’s and PhD level) from each department. The initial target sample was 1,800 participants. However, after discarding 273 questionnaires due to incomplete responses or missing data, the final valid sample consisted of 1,527 postgraduate students. This study received ethical approval from the Ethical Committee of University Utara Malaysia (Reference No.: SAPSP/Off-2021/903715).

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Demographic Sheet

A demographic information sheet was used to collect participants' background details, including: age (continuous variable); gender (male, female); education level (Master’s, PhD); home residence (rural or urban); family system (a joint family included living with grandparents and uncles/aunts, while a nuclear family included living only with parents); monthly family income (continuous variable); and marital status (single, married or divorced). A detailed table summarizing the demographic profile of the participants is provided in the supplementary materials.

2.2.2. Gratitude Questionnaire (GQ)

The Gratitude Questionnaire (GQ-6), developed by McCullough et al. (2001), was used to assess dispositional gratitude. It consists of six items, rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree (example item: “I have so much in life to be thankful for”). Items 1, 2, 4, and 5 are positively keyed, while items 3 and 6 require reverse scoring. Total scores range from 6 to 42, with higher scores indicating greater gratitude (McCullough et al., 2001). In a past study with Pakistani university students’ sample, the internal consistency was found to be good range (Cronbach’s α = 0.85) (Fatima et al., 2022).

2.2.3. Heartland Forgiveness Scale (HFS)

The Heartland Forgiveness Scale (HFS), developed by Thompson et al. (2005), was used to measure individuals’ tendencies to forgive in this study. The scale comprises 18 items across three subscales: Self-forgiveness (Items 1–6); Forgiveness of others (Items 7–12); Forgiveness of situations (Items 13–18). Each item is rated on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 = almost always false of me to 7 = almost always true of me (example item: “Although I feel badly at first when I mess up, over time I can give myself some slack”). Internal consistency was acceptable for all subscales and the overall scale: Self-forgiveness (α = 0.75); Forgiveness of others (α = 0.78); Forgiveness of situations (α = 0.77); Total HFS (α = 0.86) (Thompson et al., 2005). In a past study with Pakistani university students’ sample, the internal consistency was found to be acceptable range (Cronbach’s α = 0.78) (Hermaen & Bhutto, 2020).

2.2.4. Spirituality Scale (SS)

The Spirituality Scale (SS), developed by Parsian and Dunning (2009), was used to assess spirituality among participants. The instrument consists of 23 items and is divided into three subscales: Self-discovery (Items 1–4); Relationships (Items 5–10); Eco-awareness (Items 11–23). Responses are measured on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree (example item: “My spirituality gives me inner strength”). Higher scores indicate a greater level of spirituality. The total score ranges from 23 to 138. Internal consistency was excellent (Cronbach’s α = 0.94) (Parsian & Dunning, 2009). In a past study with Pakistani university students’ sample, the internal consistency was found to be good range (Cronbach’s α = 0.84) (Subhan et al., 2024).

2.2.5. The Meaning in Life Questionnaire (MLQ)

The Meaning in Life Questionnaire (MLQ), developed by Steger et al. (2006), was used to assess participants’ perceptions of meaning in life. The scale includes 10 items, rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = absolutely untrue to 7 = absolutely true (example item: “I understand my life’s meaning”). The scale measures two dimensions: Presence of meaning and Search for meaning. Reverse scoring is required for some items before computing the total score. The score range is 10 to 70, with higher scores indicating a greater perceived meaning in life. Internal consistency reliability ranged from α = 0.81 to 0.92 (Steger et al., 2006). In a past study with Pakistani university students’ sample, the internal consistency was found to be excellent range (Cronbach’s α = 0.90) (Muhammad et al., 2020).

2.2.6. Mental Health Inventory (MHI)

The Mental Health Inventory (MHI), developed by Veit and Ware (1983), was used to assess overall mental health. The scale consists of 38 items, divided into two subscales: Psychological distress (22 items; ex-ample item: “How much of the time have you felt lonely during the past month?”); Psychological well-being (16 items; example item: “How much time, during the past month, did you feel relaxed and free from tension?”). Items are rated on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = all of the time to 6 = none of the time. Scores range from: 22 to 132 for psychological distress; 16 to 96 for psychological well-being. To compute an overall mental health score, psychological distress items must be reverse scored, as higher values indicate worse mental health. Internal consistency was excellent, with Cronbach’s α ranging from 0.92 to 0.96 (Veit & Ware, 1983). In a past study with Pakistani university students’ sample, the internal consistency was found to be excellent range (Cronbach’s α = 0.95 to 0.96) (Khan et al., 2015).

2.3. Research Procedure

Data collection took place between October 2021 and February 2022. Prior to data collection, participants were informed that their responses would remain confidential and would be used solely for research purposes. After obtaining formal ethical approval, the researcher provided a detailed oral briefing to explain the objectives of the study. All participants were approached at the selected public universities across Pakistan. Self-report questionnaires were used for data collection. These were distributed by hand by the researcher to ensure that each participant received the materials and to allow for immediate completion. Hand delivery also al-lowed the researcher to offer clarification if participants had questions or required additional guidance during the process. Upon receiving the questionnaires, participants were given an informed consent form, and participation was entirely voluntary. Participants were assured of their right to withdraw from the study at any time without any penalty. To ensure ethical compliance, all identifying information was kept strictly confidential. Furthermore, participants who experienced any discomfort or psychological distress were provided with access to free counseling support. It took approximately 25 to 35 minutes to complete the questionnaires.

2.4. Data Analysis

Data analysis was carried out in two main stages. In the first stage, the measurement model was assessed using Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) through AMOS to evaluate the reliability and validity of the study instruments. As many researchers have used AMOS for CFA in their studies (Hasim et al., 2024; Sureshchandar, 2023). To examine relationships among variables, Pearson’s product-moment correlation coefficients were computed using SPSS. In the second stage, the structural model was tested to evaluate the study hypotheses using Covariance-Based Structural Equation Modeling (CB-SEM) with AMOS version 25.0 (Mia et al., 2019). CB-SEM was chosen due to its suitability for data with a normal distribution and its ability to provide robust model fit indices (Dash & Paul, 2021). The assumption of normality was confirmed through normality tests, which indicated that the data met the criteria for a normal distribution.

3. Results

3.1. Measurement Model

The measurement model was analyzed for reliability and validity. Using CB-SEM, the complete fit model yielded a χ² value of 14495.15 (p < .01). Model fit indices were employed to assess the adequacy of the data fit with the established model. This evaluation involved a single-step process in which both absolute and relative fit indices were computed, including the Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Normed Fit Index (NFI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). The absolute model fit was assessed using the chi-square test, taking into account sample size accuracy and the total number of parameters. Previous researchers often use multiple descriptive fit measures to ensure a comprehensive assessment of the model fit. In this context, Azzi et al. (2023) recommended specific criteria: a χ²/df ratio between 1 and 3, RMSEA and SRMR values of 0.08 or smaller, and values exceeding 0.90 for CFI, TLI, and GFI as indicative of a good fit. The initial model demonstrated an RMSEA of 0.042 and an SRMR of 0.038, while the CFI, GFI, and TLI values were 0.868, 0.843, and 0.865, respectively. The χ²/df ratio was 3.718. Based on these descriptive fit measures, the model exhibited a less than strong fit.

After modifying the initial model, the fit indices demonstrated significant improvement, with an RMSEA of 0.031 and an SRMR of 0.029. The values for CFI, GFI, and TLI were 0.912, 0.901, and 0.924, respectively, and the χ²/df ratio stood at 2.934. These descriptive fit measures indicate that the model exhibited a very strong fit, showing a robust alignment with the data. Following the satisfactory fit of the model, the factor loadings were confirmed, which are expected to exceed 0.50 for acceptability (Rita et al., 2019) and all exceeded 0.60 in this study and majority were above 0.70. The construct reliability was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha (α) and composite reliability (CR). The values obtained were as follows: Gratitude (α = 0.873, CR = 0.870), Forgiveness (α = 0.935, CR = 0.839), Self-Forgiveness (α = 0.879, CR = 0.876), Others-Forgiveness (α = 0.800, CR = 0.881), Situational-Forgiveness (α = 0.878, CR = 0.876), Spirituality (α = 0.941, CR = 0.892), Self-Discovery (α = 0.922, CR = 0.823), Relationships (α = 0.865, CR = 0.866), Eco-Awareness (α = 0.930, CR = 0.884), Meaning in Life (α = 0.918, CR = 0.914), Mental Health (α = 0.922, CR = 0.858), Psychological Wellbeing (α = 0.918, CR = 0.885), and Psychological Distress (α = 0.932, CR = 0.877). According to Hair et al. (2014), Cronbach's alpha values should exceed 0.70, while CR values should surpass 0.80. Consequently, both Cronbach's alpha and CR values were deemed acceptable, as they surpassed these threshold values (Sarstedt & Cheah, 2019).

Furthermore, the assessment of construct validity utilized the average variance extracted (AVE). The AVE values were as follows: Gratitude (AVE = 0.531), Forgiveness (AVE = 0.545), Self-Forgiveness (AVE = 0.541), Others-Forgiveness (AVE = 0.552), Situational-Forgiveness (AVE = 0.543), Spirituality (AVE = 0.541), Self-Discovery (AVE = 0.537), Relationships (AVE = 0.520), Eco-Awareness (AVE = 0.521), Meaning in Life (AVE = 0.519), Mental Health (AVE = 0.503), Psychological Wellbeing (AVE = 0.513), and Psychological Distress (AVE = 0.506). All AVE values met the threshold of 0.50 recommended by (Sarstedt et al., 2011). Additionally, the study checked for multicollinearity concerns using the variance inflation factor (VIF) test. Following the recommendations of Hair Jr et al. (2014), the VIF values should not exceed 5. The VIF values for all constructs were below this threshold, indicating the absence of multicollinearity concerns in the dataset.

3.1.1. Discriminant Validity

Discriminant validity was assessed using the method proposed by Fornell and Larcker (1981a). According to the criteria defined by Fornell and Larcker (1981b), discriminant validity is established when the square root of the AVE for each construct exceeds the correlations between constructs. In the present study, the square roots of the AVEs indeed exceeded the inter-construct correlations, indicating that all measurement constructs were suitable for inclusion in the structural model.

3.2. Bivariate Correlation (Hypotheses 1-2)

The results of

Table 1 indicate the results of Pearson Product Moment Correlation. Gratitude has a significant positive correlation with forgiveness, self-forgiveness, others forgiveness, situational forgiveness, spirituality, self-discovery, relationships, eco-awareness, meaning in life, mental health, and psychological well-being; moreover, it has a significant inverse correlation with psychological distress. Forgiveness (with subscales: self, others, situational) has a significant positive correlation with spirituality, self-discovery, relationships, eco-awareness, meaning in life, mental health, and psychological well-being; moreover, it has a significant negative correlation with psychological distress. Spirituality (with subscales: self-discovery, relationships, eco-awareness) has a significant positive correlation with meaning in life, mental health, and psychological well-being; moreover, it has a significant negative correlation with psychological distress. Meaning in life has a significant positive correlation with mental health and psychological well-being, and a significant negative correlation with psychological distress.

3.3. Structural Equation Modelling (Hypothesis 3)

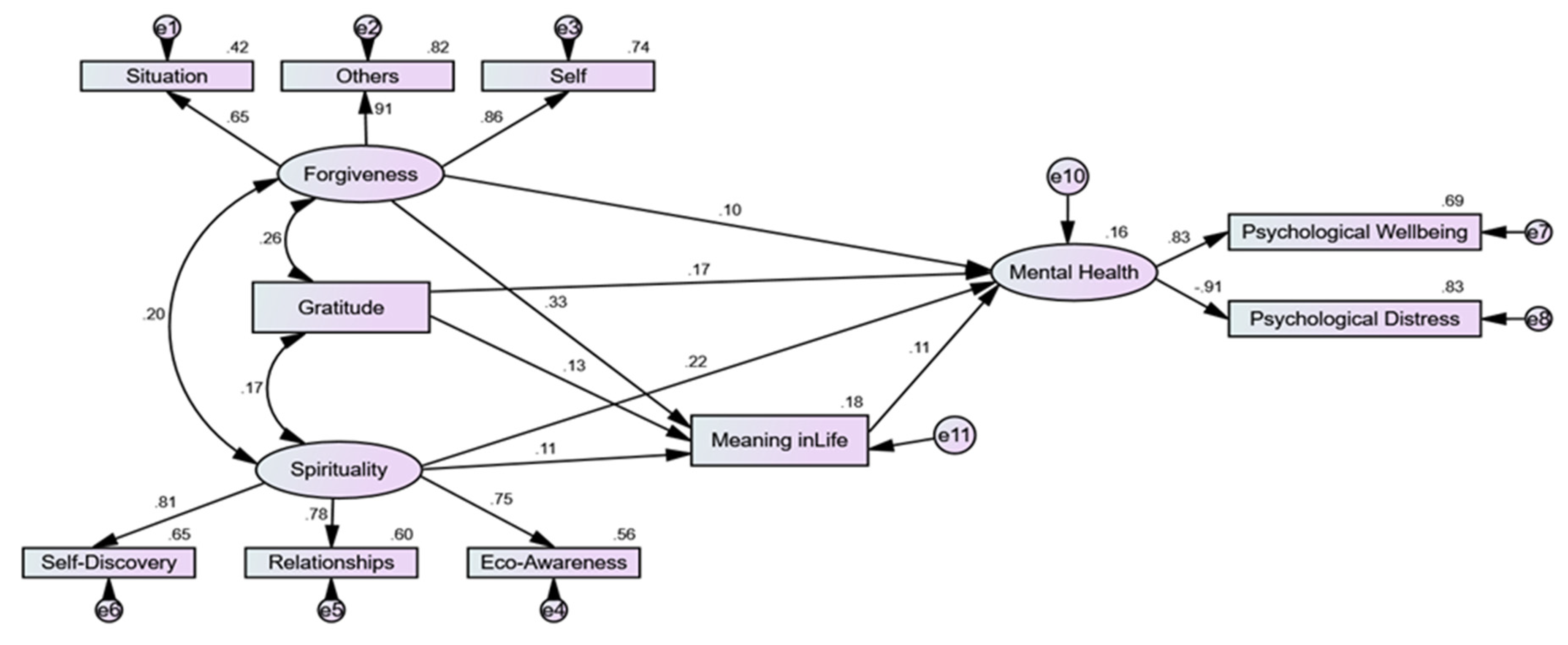

After confirming satisfactory results for the measurement model, the structural model was tested using CB-SEM to examine meaning in life as a mediator in the association of gratitude, forgiveness, and spirituality with mental health. The overall model fit was χ²(38, N = 1527) = 90.06, p < .01. The RMSEA and SRMR values were .04 and .03, respectively, while the CFI, GFI, and TLI were .99, .99, and .98. The χ²/df ratio was 2.34, indicating an excellent model fit. These indices collectively suggest that the model fits the data very well, as illustrated in

Figure 1.

After confirming the model fit, estimates were examined to assess the direct and indirect effects of gratitude, forgiveness, and spirituality on mental health through meaning in life. The analysis was conducted using 5,000 bootstrapped samples (Hayes, 2017).

Table 2 presents the standardized estimates for the effects of gratitude, forgiveness, and spirituality on meaning in life and mental health.

The results indicated that gratitude was a significant positive predictor of both meaning in life (B = .130, p < .001) and mental health (B = .170, p < .001). Similarly, forgiveness was found to be a significant positive predictor of meaning in life (B = .330, p < .001) and mental health (B = .103, p < .001). Spirituality also emerged as a significant positive predictor of meaning in life (B = .107, p < .001) and mental health (B = .222, p < .001). Moreover, meaning in life significantly and positively predicted mental health (B = .106, p < .001).

The results of the direct and indirect effects, presented in

Table 3, confirmed that meaning in life served as a significant partial mediator in the relationship between gratitude and mental health. Similarly, meaning in life was found to be a significant partial mediator in the relationship between forgiveness and mental health. Likewise, meaning in life also significantly and partially mediated the relationship between spirituality and mental health.

4. Discussion

This study investigated the relationship of gratitude, forgiveness, and spirituality with mental health among Pakistani postgraduate university students and examined the mediating role of meaning in life. The findings supported all three hypotheses, aligning with existing literature and offering new insights within the context of Pakistani postgraduate students. Regarding Hypothesis 1 (H1), results confirmed a significant positive relationship of gratitude, forgiveness, and spirituality with psychological wellbeing among postgraduate students: higher levels in these transcendental constructs were associated with higher levels of psychological wellbeing. Numerous previous studies align with this finding. Studies have previously identified gratitude, forgiveness, and spirituality as predictors of both mental health and meaning in life (Głaz, 2019; Javaheri et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2018). Gratitude has been consistently linked to enhanced mental health and well-being (Aghababaei & Tabik, 2013; Datu & Mateo, 2015; Huang et al., 2020; Tolcher et al., 2024). As Wood et al. (2010) suggest, gratitude is a foundational human strength that contributes to all dimensions of well-being. Gratitude interventions have shown lasting positive impacts on mental health by enhancing individuals' appreciation of life (Bohlmeijer et al., 2021). This may be because gratitude improves mood and cognition, allowing individuals to adopt a more positive outlook, thereby increasing overall psychological health (Hill et al., 2013; Tolcher et al., 2024).

Similarly, forgiveness has shown a strong positive correlation with mental health outcomes in previous studies (Akhtar & Barlow, 2018; Akhtar et al., 2017; Kravchuk, 2022). In the local context, Hermaen and Bhutto (2020) also found forgiveness to be positively related to well-being among Pakistani university students. Forgiveness may protect against mental illness by reducing negative emotions like anger and resentment and by promoting coping strategies, emotional regulation, and personal growth (Aricioglu, 2016).

Likewise, spirituality demonstrated a significant positive relationship with mental health and psychological well-being (Brown et al., 2013; Leung & Pong, 2021; Yoo et al., 2022). Students with higher levels of spirituality tend to report better life satisfaction and quality of life (Moreira-Almeida et al., 2014; Perez et al., 2021). Spirituality helps individuals find meaning, fosters emotional resilience, and promotes virtues such as patience, compassion, and honesty, which in turn support psychological well-being. Postgraduate education represents a transitional phase marked by heightened uncertainty regarding employment, financial stability, and familial responsibilities (Morris, 2021). The study’s results show that in such circumstances, gratitude, forgiveness, and spirituality may help students reinterpret challenges as opportunities for growth rather than threats, fostering hope and perseverance during this critical life stage.

In the specific context of Pakistani postgraduate students, these findings take on particular cultural significance. Pakistan’s society is predominantly collectivist and religiously oriented, where gratitude and spirituality are often socially reinforced values (Ali et al., 2018). Within this framework, expressions of gratitude and forgiveness are not only personal virtues but also culturally embedded mechanisms of maintaining harmony, respect, and social cohesion. For students facing intense academic and social expectations, these traits may therefore serve as adaptive resources, helping them cope with stress, maintain emotional balance, and preserve a sense of belonging. Future cross-cultural studies could further explore these relationships in contexts with a more individualistic orientation and/or a more secular approach, to examine whether the role of gratitude, forgiveness, and spirituality as coping resources operates similarly or differently across diverse cultural settings.

As regards Hypothesis 2 (H2), which proposed a negative relationship between gratitude, forgiveness, and spirituality and psychological distress, results confirm the hypothesis, consistently with extensive literature indicating that these positive traits buffer individuals against psychological difficulties. Gratitude has been found to have an inverse association with anxiety, depression, and stress (Mason, 2019; Wood et al., 2010). People who regularly express gratitude tend to experience fewer negative emotional states and show greater life satisfaction, happiness, and resilience (Tian et al., 2015). This supports the finding that gratitude improves students’ cognitive and emotional states, thereby reducing psychological distress. Forgiveness has also been shown to inversely relate to suicidal ideation, anger, and depression (Chung, 2016; Cleare et al., 2019). It serves as a powerful psychological buffer by fostering emotional healing and facilitating psychological adjustment. The findings of this study align with Li et al. (2020), who also reported an inverse relationship between forgiveness and psychological distress among university students. Spirituality, as highlighted by Chakradhar et al. (2023), is inversely associated with psychological distress. It promotes emotional balance, peace of mind, and a greater sense of life purpose (Puchalski et al., 2009). Students with strong spiritual beliefs are better equipped to manage life’s challenges, which in turn reduces their vulnerability to depression, anxiety, and other psychological difficulties (Chaves et al., 2015; Pillay et al., 2016). Therefore, H2 is also accepted.

Beyond confirming these findings, it is important to note that Pakistani students often face multiple psychosocial stressors, such as economic pressure, competitive academic environments, and limited access to mental health support (Yasmin et al., 2018). In this context, gratitude, forgiveness, and spirituality may function as culturally congruent coping strategies that provide emotional containment and meaning when formal psychological resources are scarce. These positive traits may also contribute to a collective sense of solidarity, encouraging empathy and mutual support among students who share similar struggles.

The results for Hypothesis 3 (H3) confirmed that meaning in life significantly and partially mediates the relationship between gratitude, forgiveness, and spirituality and mental health. This finding is consistent with earlier research, which highlights the role of meaning in life in promoting psychological resilience and reducing distress. Individuals who perceive a strong sense of meaning tend to experience improved well-being and reduced psychological difficulties (Arslan et al., 2022; Kleftaras & Psarra, 2012). Conversely, a lack of meaning has been linked to psychological dysfunction, including depression and high-risk psychopathological symptoms (Maccallum & Bryant, 2020). Recent research on Pakistani postgraduate students (Yasmin et al., 2018) has highlighted that, in Pakistan, there has been a significant increase in enrollment in postgraduate programs over the past decade. However, students face numerous challenges, including situational barriers (financial problems, lack of funding, and time management difficulties); institutional barriers (inefficient university procedures, inadequate support services, poor infrastructure); dispositional barriers (low self-esteem, health issues, poor communication skills); and academic barriers (limited writing, information processing, and IT skills, as well as insufficient teacher competencies). The capacity to find meaning in such challenging situations may be crucial to sustain both academic performance and psychological well-being of postgraduate students.

Beyond confirming previous findings, these results highlight how meaning in life operates as a culturally embedded resource among Pakistani postgraduate students. In a context where higher education is both a personal aspiration and a collective expectation, students often experience a dual tension between self-development and family duty (Ali et al., 2018). Gratitude and spirituality may enable them to reconcile these tensions, transforming academic stress into a sense of purpose and contribution. Forgiveness, meanwhile, may buffer the relational strains that arise in competitive or hierarchical university environments. Together, these self-transcendent traits allow students to reinterpret challenges as meaningful steps within their broader life narrative—a process central to psychological resilience in collectivist societies.

This research offers several noteworthy strengths. It addresses a significant gap in the Pakistani context, particularly among postgraduate students in public sector universities in Punjab, where limited prior research has examined the relationships among gratitude, forgiveness, spirituality, and mental health. By providing empirical evidence on these associations and the mediating role of meaning in life, the study makes a valuable theoretical contribution to the literature on positive psychology. Practically, the findings can guide university administrators and policymakers in designing mental health initiatives that incorporate gratitude, forgiveness, spirituality, and meaning-making as integral components of student support services. Beyond the local context, these results have global relevance, offering insights for researchers and practitioners in other regions seeking to understand and promote student mental health through the lens of positive psychology.

The findings of this research have significant practical implications for clinical psychologists, mental health professionals, university administrators, and policymakers. The results highlight the importance of integrating positive psychological constructs—gratitude, forgiveness, spirituality, and meaning in life—into mental health initiatives on university campuses. Universities should consider offering dedicated programmes, workshops, or courses in positive psychology to foster these traits, which have been shown to promote well-being and reduce psychological distress among students.

Given the centrality of spirituality and community in Pakistani culture, interventions could integrate faith-sensitive counseling and group-based meaning-making activities that align with students’ values. Additionally, postgraduate mentorship programs could foster gratitude and forgiveness through reflective dialogues, helping students translate academic challenges into personal growth experiences. The Higher Education Commission (HEC) of Pakistan should also take a proactive role by encouraging or mandating the inclusion of positive psychology content across curricula at the undergraduate and postgraduate levels. Embedding these principles into various academic disciplines can equip students with effective coping strategies and improve their overall psychological resilience.

Currently, most Pakistani universities lack formal coursework or syllabus aimed at addressing students’ psychological well-being. This research underscores the urgent need for policy reforms to incorporate mental health education into the higher education framework. Psychology departments and student support units should be encouraged to offer free psychological counseling services on campus, enabling students to access professional help without stigma or financial burden. These services could include training sessions on emotional regulation, stress management, and the development of gratitude, forgiveness, and spiritual practices.

Despite its contributions, this study has a few limitations. Data were collected only from one province (Punjab), which limits the generalizability of the findings to all Pakistani university students. The research focused exclusively on full-time postgraduate students in public sector universities and did not address mental health issues in private universities or undergraduate students. Moreover, demographic variables such as gender, income, and rural versus urban background were not explored as potential moderators; future studies could explore the influence of these variables.

Future studies could adopt longitudinal or mixed-method designs to examine how meaning in life evolves across different postgraduate stages or to capture the lived experiences of how gratitude and spirituality are expressed and practiced in Pakistani cultural settings. Such approaches would deepen understanding of the ways in which positive psychology traits interact with cultural identity, faith, and educational stressors.

5. Conclusions

This research concludes that mental health is significantly associated with gratitude, forgiveness, and spirituality among postgraduate university students in Pakistan. Students who demonstrated higher levels of these positive traits reported lower psychological distress and greater psychological well-being. Furthermore, meaning in life was found to partially mediate the relationship between gratitude, forgiveness, and spirituality and mental health, highlighting its critical role in enhancing students’ psychological functioning. Overall, these findings emphasize the value of promoting positive psychological traits and meaning-making among students to improve their mental health. The results can inform interventions, curriculum development, and policy decisions aimed at supporting university students’ emotional and psychological well-being.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Table S1: Demographic Information Profile.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A., M.A.G., A.H.H., and L.F; methodology, M.A.G. and L.F.; data analysis, M.A.; investigation, M.A.G., and A.H.H; Writing— Review and Editing, M.A., M.A.G. and L.F.; supervision, L.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of University Utara Malaysia [protocol code SAPSP/Off-2021/903715; date of approval 2 March 2021

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

References

- Aghababaei, N., & Tabik, M. T. (2013). Gratitude and mental health: Differences between religious and general gratitude in a Muslim context. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 16(8), 761-766.

- Akhtar, S., & Barlow, J. (2018). Forgiveness therapy for the promotion of mental well-being: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 19(1), 107-122.

- Akhtar, S., Dolan, A., & Barlow, J. (2017). Understanding the relationship between state forgiveness and psychological wellbeing: A qualitative study. Journal of religion and health, 56(2), 450-463.

- Ali, R., Khurshid, K., Shahzad, A., Hussain, I., & Bakar, Z. A. (2018). Nature of Conceptions of Learning in a Collectivistic Society: A qualitative case study of Pakistan. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 14(4), 1175-1187.

- Aricioglu, A. (2016). Mediating the Effect of Gratitude in the Relationship between Forgiveness and Life Satisfaction among University Students. International Journal of Higher Education, 5(2), 275-282.

- Arslan, G., Yıldırım, M., Karataş, Z., Kabasakal, Z., & Kılınç, M. (2022). Meaningful living to promote complete mental health among university students in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 20(2), 930-942.

- Azzi, N. M., Azzi, V., Hallit, R., Malaeb, D., Dabbous, M., Sakr, F., Fekih-Romdhane, F., Obeid, S., & Hallit, S. (2023). Psychometric properties of an arabic translation of the short form of Weinstein noise sensitivity scale (NSS-SF) in a community sample of adolescents. BMC psychology, 11(1), 384.

- Bali, M., Bakhshi, A., Khajuria, A., & Anand, P. (2022). Examining the association of Gratitude with psychological well-being of emerging adults: the mediating role of spirituality. Trends in Psychology, 30(4), 670-687.

- Bibi, A., Blackwell, S. E., & Margraf, J. (2021). Mental health, suicidal ideation, and experience of bullying among university students in Pakistan. Journal of health psychology, 26(8), 1185-1196.

- Blanco, C., Okuda, M., Wright, C., Hasin, D. S., Grant, B. F., Liu, S.-M., & Olfson, M. (2008). Mental health of college students and their non–college-attending peers: results from the national epidemiologic study on alcohol and related conditions. Archives of general psychiatry, 65(12), 1429-1437.

- Bohlmeijer, E. T., Kraiss, J. T., Watkins, P., & Schotanus-Dijkstra, M. (2021). Promoting gratitude as a resource for sustainable mental health: Results of a 3-armed randomized controlled trial up to 6 months follow-up. Journal of happiness studies, 22(3), 1011-1032.

- Brown, D. R., Carney, J. S., Parrish, M. S., & Klem, J. L. (2013). Assessing spirituality: The relationship between spirituality and mental health. Journal of spirituality in mental health, 15(2), 107-122.

- Browning, M. H., Larson, L. R., Sharaievska, I., Rigolon, A., McAnirlin, O., Mullenbach, L., Cloutier, S., Vu, T. M., Thomsen, J., & Reigner, N. (2021). Psychological impacts from COVID-19 among university students: Risk factors across seven states in the United States. PloS one, 16(1), e0245327.

- Burns, R. (2016). Psychosocial well-being. In Encyclopedia of geropsychology (pp. 1-8). Springer.

- Carreno, D. F., Eisenbeck, N., Cangas, A. J., García-Montes, J. M., Del Vas, L. G., & María, A. T. (2020). Spanish adaptation of the Personal Meaning Profile-Brief: Meaning in life, psychological well-being, and distress. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 20(2), 151-162.

- Chakradhar, K., Arumugham, P., & Venkataraman, M. (2023). The relationship between spirituality, resilience, and perceived stress among social work students: Implications for educators. Social Work Education, 42(8), 1163-1180.

- Chaves, E. d. C. L., Iunes, D. H., Moura, C. d. C., Carvalho, L. C., Silva, A. M., & Carvalho, E. C. d. (2015). Anxiety and spirituality in university students: a cross-sectional study. Revista brasileira de enfermagem, 68, 504-509.

- Chen, T., & Lucock, M. (2022). The mental health of university students during the COVID-19 pandemic: An online survey in the UK. PloS one, 17(1), e0262562.

- Chung, M.-S. (2016). Relation between lack of forgiveness and depression: The moderating effect of self-compassion. Psychological reports, 119(3), 573-585.

- Cleare, S., Gumley, A., & O'Connor, R. C. (2019). Self-compassion, self-forgiveness, suicidal ideation, and self-harm: A systematic review. Clinical psychology & psychotherapy, 26(5), 511-530.

- Costa, L., Worthington, J. E. L., Montanha, C. C., Couto, A. B., & Cunha, C. (2021). Construct validity of two measures of self-forgiveness in Portugal: a study of self-forgiveness, psychological symptoms, and well-being. Research in Psychotherapy: Psychopathology, Process, and Outcome, 24(1), 500.

- Cregg, D. R., & Cheavens, J. S. (2021). Gratitude interventions: Effective self-help? A meta-analysis of the impact on symptoms of depression and anxiety. Journal of happiness studies, 22(1), 413-445.

- Dar, M., & Wasti, S. E. (2017). Pakistan Economic Survey 2016-17. Ministery of Finance, Government of Pakistan.

- Datu, J. A. D., & Mateo, N. J. (2015). Gratitude and life satisfaction among Filipino adolescents: The mediating role of meaning in life. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 37(2), 198-206.

- Davis, D. E., Ho, M. Y., Griffin, B. J., Bell, C., Hook, J. N., Van Tongeren, D. R., DeBlaere, C., Worthington Jr, E. L., & Westbrook, C. J. (2015). Forgiving the self and physical and mental health correlates: a meta-analytic review. Journal of counseling psychology, 62(2), 329.

- de Diego Cordero, R., Lucchetti, G., Fernández-Vazquez, A., & Badanta-Romero, B. (2019). Opinions, knowledge and attitudes concerning “spirituality, religiosity and health” among health graduates in a Spanish university. Journal of religion and health, 58(5), 1592-1604.

- Deb, S., McGirr, K., & Sun, J. (2016). RETRACTED ARTICLE: Spirituality in Indian university students and its associations with socioeconomic status, religious background, social support, and mental health. Journal of religion and health, 55(5), 1623-1641.

- Fatima, S., Waheed, S., Daud, S., & Aslam, S. (2022). Gratitude, Self-Regulation, And Academic Motivation During COVID-19 In University Students: Differential Associations For Earning And Non-Earning Students. Webology, 19(2).

- Fincham, F. D., & May, R. W. (2021). Divine forgiveness protects against psychological distress following a natural disaster attributed to God. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 16(1), 20-26.

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981a). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of marketing research, 18(1), 39-50.

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981b). Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics. Journal of marketing research, 18(3), 382-388.

- Garssen, B., Visser, A., & Pool, G. (2021). Does spirituality or religion positively affect mental health? Meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 31(1), 4-20.

- Ghayas, S., Shamim, S., Anjum, F., & Hussain, M. (2014). Prevalence and severity of depression among undergraduate students in Karachi, Pakistan: A cross sectional study. Tropical Journal of Pharmaceutical Research, 13(10), 1733-1738.

- Głaz, S. (2019). The relationship of forgiveness and values with meaning in life of Polish students. Journal of religion and health, 58(5), 1886-1907.

- Gungor, A., Young, M. E., & Sivo, S. A. (2021). Negative Life Events and Psychological Distress and Life Satisfaction in US College Students: The Moderating Effects of Optimism, Hope, and Gratitude. Journal of Pedagogical Research, 5(4), 62-75.

- Guse, T., Vescovelli, F., & Croxford, S.-A. (2019). Subjective well-being and gratitude among South African adolescents: Exploring gender and cultural differences. Youth & Society, 51(5), 591-615.

- Hair, J. F., Gabriel, M., & Patel, V. (2014). AMOS covariance-based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM): Guidelines on its application as a marketing research tool. Brazilian Journal of Marketing, 13(2), 44-55.

- Halama, P., & Dedova, M. (2007). Meaning in life and hope as predictors of positive mental health: Do they explain residual variance not predicted by personality traits? Studia psychologica, 49(3), 191.

- Hasim, M. A., Jabar, J., & Wei, V. W. M. (2024). Measuring E-Learning Antecedents in The Context of Higher Education through Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analysis. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 14(9), 751-769.

- Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford publications.

- Heintzelman, S. J., & King, L. A. (2014). Life is pretty meaningful. American psychologist, 69(6), 561.

- Hermaen, H., & Bhutto, Z. H. (2020). Gratitude and forgiveness as predictors of subjective well-being among young adults in Pakistan. Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research, 35(4), 725-738.

- Hersi, L., Tesfay, K., Gesesew, H., Krahl, W., Ereg, D., & Tesfaye, M. (2017). Mental distress and associated factors among undergraduate students at the University of Hargeisa, Somaliland: a cross-sectional study. International journal of mental health systems, 11(1), 39.

- Hill, P. L., Allemand, M., & Roberts, B. W. (2013). Examining the pathways between gratitude and self-rated physical health across adulthood. Personality and individual differences, 54(1), 92-96.

- Holder, M. D., Coleman, B., Krupa, T., & Krupa, E. (2016). Well-being’s relation to religiosity and spirituality in children and adolescents in Zambia. Journal of happiness studies, 17(3), 1235-1253.

- Howell, A. J., Passmore, H.-A., & Buro, K. (2013). Meaning in nature: Meaning in life as a mediator of the relationship between nature connectedness and well-being. Journal of happiness studies, 14(6), 1681-1696.

- Huang, N., Qiu, S., Alizadeh, A., & Wu, H. (2020). How incivility and academic stress influence psychological health among college students: The moderating role of gratitude. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(9), 3237.

- Hunt, J., & Eisenberg, D. (2010). Mental health problems and help-seeking behavior among college students. Journal of adolescent health, 46(1), 3-10.

- Huo, J.-Y., Wang, X.-Q., Steger, M. F., Ge, Y., Wang, Y.-C., Liu, M.-F., & Ye, B.-J. (2020). Implicit meaning in life: The assessment and construct validity of implicit meaning in life and relations with explicit meaning in life and depression. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 15(4), 500-518.

- Hussain, S. S., Gul, R. B., & Asad, N. (2018). Integration of mental health into primary healthcare: perceptions of stakeholders in Pakistan. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, 24(2), 146.

- Javaheri, A., Esmaily, A., & Vakili, M. (2022). The relationship between post traumatic growth and the meaning of life in COVID-19 survivors: The mediating role of spiritual wellbeing. Rooyesh-e-Ravanshenasi Journal (RRJ), 10(11), 87-98.

- Jeny, R., & Varghese, P. (2013). Spiritual correlates of psychological well-being. Indian Streams Research Journal, 3(7), 1-7.

- Jibeen, T. (2016). Perceived social support and mental health problems among Pakistani university students. Community mental health journal, 52(8), 1004-1008.

- Karaman, M. A., Vela, J. C., & Garcia, C. (2020). Do hope and meaning of life mediate resilience and life satisfaction among Latinx students? British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 48(5), 685-696.

- Kaur, S., & Sidhu, G. K. (2009). A Qualitative Study of Postgraduate Students' Learning Experiences in Malaysia. International Education Studies, 2(3), 47-56.

- Khan, M. (2015). Impact of spiritual practices on well-being among Madarsa and University Students. International Journal of Indian Psychology, 2(2), 88-99.

- Khan, M. J., Hanif, R., & Tariq, N. (2015). Translation and Validation of Mental Health Inventory. Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research, 30(1), 65-79.

- Khan, M. N., Akhtar, P., Ijaz, S., & Waqas, A. (2021). Prevalence of depressive symptoms among university students in Pakistan: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in public health, 8, 603357.

- Kim, J. J., Payne, E. S., & Tracy, E. L. (2022). Indirect effects of forgiveness on psychological health through anger and hope: A parallel mediation analysis. Journal of religion and health, 61(5), 3729-3746.

- Kleftaras, G., & Psarra, E. (2012). Meaning in life, psychological well-being and depressive symptomatology: A comparative study. Psychology, 3(04), 337.

- Kleiman, E. M., Adams, L. M., Kashdan, T. B., & Riskind, J. H. (2013). Gratitude and grit indirectly reduce risk of suicidal ideations by enhancing meaning in life: Evidence for a mediated moderation model. Journal of research in personality, 47(5), 539-546.

- Kravchuk, S. (2022). Willingness to Self-forgive as a Predictor of the Well-being of Young Students. Revista Românească pentru Educaţie Multidimensională, 14(4 Sup. 1), 264-272.

- Lal, S., Ungar, M., Malla, A., Frankish, J., & Suto, M. (2014). Meanings of well-being from the perspectives of youth recently diagnosed with psychosis. Journal of Mental Health, 23(1), 25-30.

- Leung, C. H., & Pong, H. K. (2021). Cross-sectional study of the relationship between the spiritual wellbeing and psychological health among university students. PloS one, 16(4), e0249702.

- Levecque, K., Anseel, F., De Beuckelaer, A., Van der Heyden, J., & Gisle, L. (2017). Work organization and mental health problems in PhD students. Research policy, 46(4), 868-879.

- Li, L., Yao, C., Zhang, Y., & Chen, G. (2020). Trait forgiveness moderated the relationship between work stress and psychological distress among final-year nursing students: a pilot study. Frontiers in psychology, 11, 1674.

- Lipson, S. K., Lattie, E. G., & Eisenberg, D. (2019). Increased rates of mental health service utilization by US college students: 10-year population-level trends (2007–2017). Psychiatric services, 70(1), 60-63.

- Litalien, M., Atari, D. O., & Obasi, I. (2022). The influence of religiosity and spirituality on health in Canada: A systematic literature review. Journal of religion and health, 61(1), 373-414.

- Long, K. N., Symons, X., VanderWeele, T. J., Balboni, T. A., Rosmarin, D. H., Puchalski, C., Cutts, T., Gunderson, G. R., Idler, E., & Oman, D. (2024). Spirituality as a determinant of health: Emerging policies, practices, and systems: Article examines spirituality as a social determinant of health. Health Affairs, 43(6), 783-790.

- Maccallum, F., & Bryant, R. A. (2020). A network approach to understanding quality of life impairments in prolonged grief disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 33(1), 106-115.

- Măirean, C., Turliuc, M. N., & Arghire, D. (2019). The relationship between trait gratitude and psychological wellbeing in university students: The mediating role of affective state and the moderating role of state gratitude. Journal of happiness studies, 20(5).

- Mason, H. D. (2019). Gratitude, well-being and psychological distress among South African university students. Journal of psychology in Africa, 29(4), 354-360.

- McCullough, M. E., Emmons, R. A., & Tsang, J.-A. (2001). The gratitude questionnaire-six item form (GQ-6). Retrieved April, 16, 2010.

- McCullough, M. E., Kimeldorf, M. B., & Cohen, A. D. (2008). An adaptation for altruism: The social causes, social effects, and social evolution of gratitude. Current directions in psychological science, 17(4), 281-285.

- Mia, M. M., Majri, Y., & Rahman, I. K. A. (2019). Covariance based-structural equation modeling (CB-SEM) using AMOS in management research. Journal of Business and Management, 21(1), 56-61.

- Moreira-Almeida, A., Koenig, H. G., & Lucchetti, G. (2014). Clinical implications of spirituality to mental health: review of evidence and practical guidelines. Revista brasileira de psiquiatria, 36(2), 176-182.

- Morris, C. (2021). “Peering through the window looking in”: postgraduate experiences of non-belonging and belonging in relation to mental health and wellbeing. Studies in Graduate and Postdoctoral Education, 12(1), 131-144.

- Muhammad, H., Ahmad, S., & Khan, M. I. (2020). Exploring predicting role of students grit in boosting Hope, meaning in life and subjective happiness among undergraduates of university. Pakistan Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Research, 3(01), 157-176.

- Negi, A. S., Khanna, A., & Aggarwal, R. (2021). Spirituality as predictor of depression, anxiety and stress among engineering students. Journal of Public Health, 29(1), 103-116.

- Nizzolino, S., & Canals, A. (2023). Pandemic and Post-Pandemic Effects on University Students' Behavioral Traits: How Community of Inquiry Can Support Instructional Design During Times of Changing Cognitive Habits. International Journal of e-Collaboration (IJeC), 19(1), 1-19.

- Oriol, X., Miranda, R., Bazán, C., & Benavente, E. (2020). Distinct routes to understand the relationship between dispositional optimism and life satisfaction: Self-control and grit, positive affect, gratitude, and meaning in life. Frontiers in psychology, 11, 907.

- Parsian, N., & Dunning, P. (2009). Developing and validating a questionnaire to measure spirituality: A psychometric process.

- Perez, J. A., Peralta, C. O., & Besa, F. B. (2021). Gratitude and life satisfaction: the mediating role of spirituality among Filipinos. Journal of Beliefs & Values, 42(4), 511-522.

- Pillay, N., Ramlall, S., & Burns, J. K. (2016). Spirituality, depression and quality of life in medical students in KwaZulu-Natal. South African Journal of Psychiatry, 22(1), 1-6.

- Puchalski, C., Ferrell, B., Virani, R., Otis-Green, S., Baird, P., Bull, J., Chochinov, H., Handzo, G., Nelson-Becker, H., & Prince-Paul, M. (2009). Improving the quality of spiritual care as a dimension of palliative care: the report of the Consensus Conference. Journal of palliative medicine, 12(10), 885-904.

- Rita, P., Oliveira, T., & Farisa, A. (2019). The impact of e-service quality and customer satisfaction on customer behavior in online shopping. Heliyon, 5(10).

- Rye, M. S., & Pargament, K. I. (2002). Forgiveness and romantic relationships in college: Can it heal the wounded heart? Journal of clinical Psychology, 58(4), 419-441.

- Saleem, S., Mahmood, Z., & Naz, M. (2013). Mental health problems in university students: A prevalence study. FWU Journal of Social Sciences, 7(2), 124-130.

- Sapmaz, F., Yıldırım, M., Topçuoğlu, P., Nalbant, D., & Sızır, U. (2016). Gratitude, forgiveness and humility as predictors of subjective well-being among university students. International Online Journal of Educational Sciences, 8(1), 38-47.

- Sargent, A. M. (2015). Moderation and mediation of the spirituality and subjective well-being relation Colorado State University].

- Sarstedt, M., & Cheah, J.-H. (2019). Partial least squares structural equation modeling using SmartPLS: a software review. In: Springer.

- Sarstedt, M. , Henseler, J., & Ringle, C. M. (2011). Multigroup analysis in partial least squares (PLS) path modeling: Alternative methods and empirical results. In Measurement and research methods in international marketing (pp. 195-218). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Scheaffer, R. L., Mendenhall, W., Ott, L., & Gerow, K. (1990). Elementary survey sampling (Vol. 501). Pws-Kent Boston.

- Steger, M. F. (2022). Meaning in life is a fundamental protective factor in the context of psychopathology. World Psychiatry, 21(3), 389.

- Steger, M. F., Frazier, P., Oishi, S., & Kaler, M. (2006). The meaning in life questionnaire: assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. Journal of counseling psychology, 53(1), 80.

- Stellar, J. E., Gordon, A. M., Piff, P. K., Cordaro, D., Anderson, C. L., Bai, Y., Maruskin, L. A., & Keltner, D. (2017). Self-transcendent emotions and their social functions: Compassion, gratitude, and awe bind us to others through prosociality. Emotion Review, 9(3), 200-207.

- Subhan, A., Sarhad, M., & Nazneen, L. (2024). Exploring The Role of Spirituality in Mindfulness and Quality of Life Among University Students in Peshawar. Social Science Review Archives, 2(2), 2009-2030.

- Sureshchandar, G. (2023). Quality 4.0–a measurement model using the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) approach. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 40(1), 280-303.

- Thompson, L. Y., Snyder, C., & Hoffman, L. (2005). Heartland Forgiveness Sclae. Faculty Publications, Department of Psychology, 452.

- Tian, L. , Du, M., & Huebner, E. S. (2015). The effect of gratitude on elementary school students’ subjective well-being in schools: The mediating role of prosocial behavior. Social Indicators Research.

- Tolcher, K., Cauble, M., & Downs, A. (2024). Evaluating the effects of gratitude interventions on college student well-being. Journal of american college HealtH, 72(5), 1321-1325.

- Vargas-Huicochea, I., Álvarez-del-Río, A., Rodríguez-Machain, A. C., Aguirre-Benítez, E. L., & Kelsall, N. (2022). Seeking psychiatric attention among university students with mental health problems: The influence of disease perception. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 20(1), 505-521.

- Veit, C. T., & Ware, J. E. (1983). The structure of psychological distress and well-being in general populations. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 51(5), 730.

- Wahed, W. Y. A., & Hassan, S. K. (2017). Prevalence and associated factors of stress, anxiety and depression among medical Fayoum University students. Alexandria Journal of medicine, 53(1), 77-84.

- Wang, Z., Koenig, H. G., Ma, H., & Shohaib, S. A. (2016). Religion, purpose in life, social support, and psychological distress in Chinese university students. Journal of religion and health, 55(3), 1055-1064.

- Wood, A. M., Froh, J. J., & Geraghty, A. W. (2010). Gratitude and well-being: A review and theoretical integration. Clinical psychology review, 30(7), 890-905.

- Wu, A. M., Lei, L. L., & Ku, L. (2013). Psychological needs, purpose in life, and problem video game playing among Chinese young adults. International Journal of Psychology, 48(4), 583-590. 4).

- Wüthrich-Grossenbacher, U. (2024). The need to widen the concept of health and to include the spiritual dimension. International Journal of Public Health, 69, 1606648.

- Yasmin, F., Saeed, M., & Ahmad, N. (2018). Challenges faced by postgraduate students: A case study of a private university in Pakistan. Journal of Education and Human Development, 7(1), 109-116. [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J., You, S., & Lee, J. (2022). Relationship between neuroticism, spiritual well-being, and subjective well-being in Korean university students. Religions, 13(6), 505.

- Yoon, E., Cabirou, L., Hoepf, A., & Knoll, M. (2021). Interrelations of religiousness/spirituality, meaning in life, and mental health. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 34(2), 219-234.

- Zhang, M. X. Zhang, M. X., Mou, N. L., Tong, K. K., & Wu, A. M. (2018). Investigation of the effects of purpose in life, grit, gratitude, and school belonging on mental distress among Chinese emerging adults. International journal of environmental research and public health, 15(10), 2147.

- Zhou, Y., & Xu, W. (2019). The mediator effect of meaning in life in the relationship between self-acceptance and psychological wellbeing among gastrointestinal cancer patients. Psychology, health & medicine, 24(6), 725-731.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).