1. Introduction

Over the last decade, advancements in transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) have led to an expansion of its indication, now including patients with severe aortic stenosis (AS) who are at low surgical risk, with encouraging results in this population [

1,

2].

The extension of TAVI indication to low-risk patients is associated with an increase in the number of procedures performed in patients who are younger and with a longer life expectancy compared to those who have received first generation prostheses. Consequently, there is a pressing need to optimize both procedural planning and prostheses’ design to minimize the incidence of peri-procedural complications such as para-valvular leak (PVL) and conduction abnormalities which are related to worse long-term outcomes.

Nevertheless, even if the incidence of these complications appears to be decreased in the last randomized clinical trials (RCTs)[

1,

2], enrolling low risk patients and using last generation devices, such untoward issues still generate some concerns with the extension of TAVI indication to patients with a longer life-expectancy.

Two main types of transcatheter heart valves (THVs) are commercially available: balloon expandable valves (BEV) and self-expandable valves (SEV). BEVs rely on the radial force provided by the accompanying balloon to achieve expansion. In contrast SEVs deploy automatically and continue to expand until they meet resistance from the annular wall, allowing them to conform to the anatomical features of the aortic wall[

3].

Whether these 2 very different THV concepts are achieving similar or different clinical outcomes remains unclear and controversial data are reported in literature[

4,

5,

6].

Furthermore, while most of the available studies report only early and short-term outcomes of transcatheter procedures, there is a growing interest in long-term outcomes with the extension of TAVI indication to low-risk patients.

On the other hand, the long-term durability of bioprosthetic surgical valves has been proved in several studies[

7,

8].

The present study sought to compare post-procedural outcomes and midterm survival of low-risk patients who underwent surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) or TAVI using BE or SE prostheses.

2. Method

Patient population and study design

From September 2017 to December 2022, data of consecutive patients undergoing SAVR or trans-femoral (TF) TAVI for severe AS were prospectively collected and retrospectively analyzed.

Patients were eligible for the inclusion in the study if they had an isolated severe AS, a low surgical risk, defined as Euroscore II or STS score < 4[

9,

10], and were aged between 70 and 85 years. Exclusion criteria were need for concomitant surgical or transcatheter procedures, a history of cardiac surgery, valve-in-valve procedures, and requirement for urgent or emergent surgery.

Patients were divided into 3 groups according to the type of prosthesis they received: surgical bioprosthesis, BE TAVI or SE TAVI. The 3 groups were compared in terms of pre-operative characteristics, early post-operative outcomes, and midterm survival.

Each patient was allocated to the most appropriate approach after an accurate multidisciplinary evaluation based on clinical history, blood tests, electrocardiogram, echocardiogram, computed tomography (CT), and cardiac catheterization.

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by local Ethic Committee at the Mauriziano Hospital, Turin, Italy (Protocol number 260-2022).

All patients received a follow-up visit at 3 and 6 months and an annual telephone survey. The follow up was completed on March 2025.

Operative technique

All patients underwent surgery or TF TAVI according to our standardized approach[

11,

12].

Briefly, all TAVI were performed by TF approach under conscious sedation. Both new generation balloon-expandable (Sapien, Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA, USA) and self-expandable (Evolut [ Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA], Portico/Navitor [Abbott, Chicago, IL, USA]) prostheses were implanted. Balloon aortic valvuloplasty, before and/or after TAVI, was performed at operator discretion. The choice of prosthesis type and size was mainly based on CT scan.

SAVR was performed through a mid-sternotomy or full sternotomy. Both bovine pericardial valves such as Carpentier–Edwards Magna Ease (Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA, USA) and Avalus (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA), and porcine valve such Epic bioprosthesis (Abbott, Chicago, IL, USA) have been implanted. The following 2 suture techniques were used: a continuous suture technique by means of 3 sutures of 0 polypropylene or an interrupted suture by means of single stiches of 2/0 non-absorbable polyester suture with ventricular side pledgets.

Endpoints and definitions

The primary endpoint of the study was midterm all-cause mortality. Secondary endpoints were post-procedural complications such as acute kidney injury (AKI), stroke, myocardial infarction (MI), permanent pacemaker (PPM) implantation, new-onset left bundle branch block (LBBB) and para-valvular leak (PVL) greater than mild. AKI was defined according to Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) criteria[

13].

Peri-operative MI was recorded in case of cTn-T value > 10 times the 99

th percentile of the upper reference limit during the first 48 hours with ECG abnormalities and/or angiographic or imaging evidence of new myocardial ischemia or/and new cases of myocardial viability[

14].

Statistical analysis

For continuous variables data were presented with mean and interquartile range (IQR), for categorical variables data were reported as counts and percentage. Differences between groups were assessed using Student’s t-test and Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate.

To balance the distribution of baseline risk factors between groups, a propensity score (PS) matching was performed. PS matching was performed by running a logistic binary regression with the prosthesis type as dependent variable; the probability of the regression was stored and used as matching score by the best neighbor matching. The overall efficacy of the match method was then tested re-running the logistic regression and verifying that no variables had significant difference. The a-priori selected variables were age, gender, hypertension, chronic kidney disease (CKD), Euroscore II and STS score.

Midterm survival function was assessed and reported using the Kaplan-Meier method and the survival curves were compared using the log-rank test (Mantel-Cox).

A p value of < 0.05 was considered statically significant.

The statical analysis was performed using SPSS Version 27.0 (Armonk, NY, IBM.Corp).

3. Results

Overall population

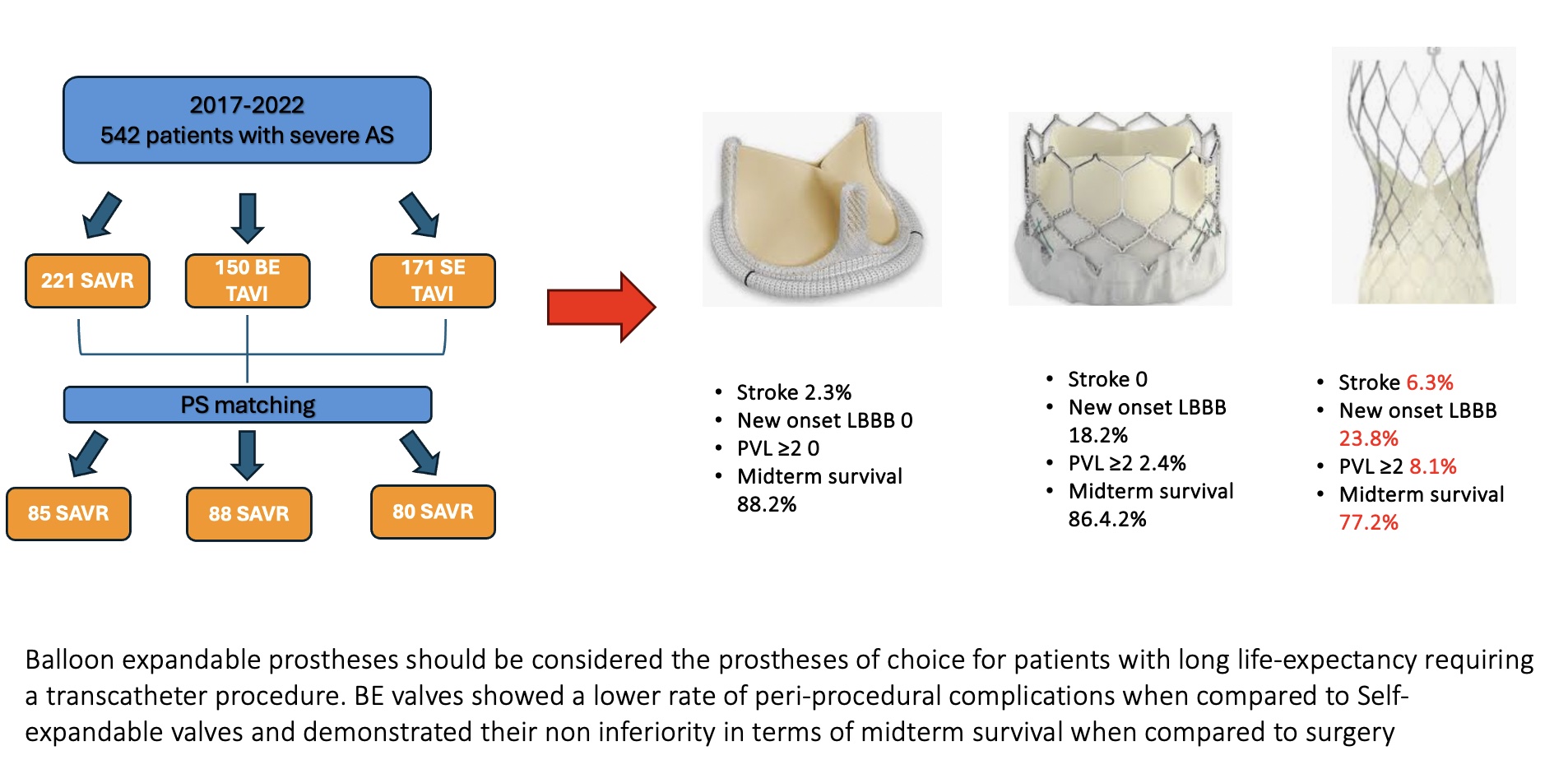

During the study period 542 patients with diagnosis of severe isolated AS underwent SAVR (n=221, 40.8%) or BE TAVI (n=150, 27.7%) or SE TAVI (n=171, 31.5%).

The baseline characteristics and comorbidities are reported in Supplemental Material

Table 1.

Both SE and BE TAVI patients were significantly older compared to surgical patients (SE group 81 [80-84]; BE group 81 [78-83], SAVR group 75 [71-78], p<0.001). Patients who received a SE prosthesis were more commonly female (SE group 65.5%; BE group 37.3%, SAVR group 45.2%, p<0.001) and with a higher incidence of hypertension (SE group 94.7%, BE group 86%, SAVR group 90.5%, p=0.028) when compared to patients who received a BE TAVI or a surgical bioprosthesis.

Patients who underwent SE or BE TAVI had a higher Euroscore II (SE group 2.22 [1.74-3.01]; BE group 2.16 [1.62-2.90]; SAVR group 1.77 [1.27-2.43], p<0.001) and a higher STS score (SE group 2.26 [1.87-3.07]; BE group 2.34 [1.75-3.1]; SAVR group 1.58 [1.1-2,54], p<0.001).

Regarding post-operative outcomes surgical patients had a higher incidence of post-procedural AKI compared to BE and SE TAVI patients (SAVR group 16.7%; BE group 2%; SE group 4.1%, p<0.001). SE TAVI were associated with a significant higher incidence of stroke (SE group 5.8%; BE group 0.7%; SAVR 2.7%, p=0.026) and PVL ≥ 2 (SE group 9%; BE group 2.8%; SAVR 0.5%, p<0.001) compared to BE TAVI and surgical bioprosthesis. Patients who received a SE or BE prosthesis are more likely to develop LBBB (SE group 24%; BE group 22%; SAVR group 0.9%, p<0.001) and to require PPM implantation (SE group 12.3%, BE group 9.3%; SAVR group 3.6%, p=0.005) compared to surgical patients.

Post-operative outcomes are reported in Supplemental Material

Table 2.

Matched population

After propensity score matching, 85 surgical patients were compared to 88 patients with a BE TAVI and 80 patients who have received a SE TAVI.

Baseline characteristics of matched population are reported in

Table 1.

Propensity score matching resulted in a good matching of all pre-procedural variables, including for important prognostic factors such as age, cardiovascular risk factors, kidney function, Euroscore II and STS score.

Post-procedural outcomes of matched population are reported in

Table 2.

Surgical patients still had a significantly higher incidence of post-procedural AKI (SAVR group 23.3%, BE group 2.3%, SE group 5%, p<0.001). However, no significant differences were reported in terms of need for RRT between the 3 groups.

SE prostheses were associated with a significantly higher incidence of post procedural stroke (SE group 6.3%, BE group 0, SAVR group 2.3%, p=0.045) and PVL (SE group 8.1%, BE group 2.4%, SAVR group 0, p=0.017).

BE prostheses were still associated with a higher risk of post-procedural LBBB compared to surgery, however its rate remained significantly lower than in SE TAVI (BE group 18.2%, SE group 23.8%, SAVR group 0 %, p<0.001).

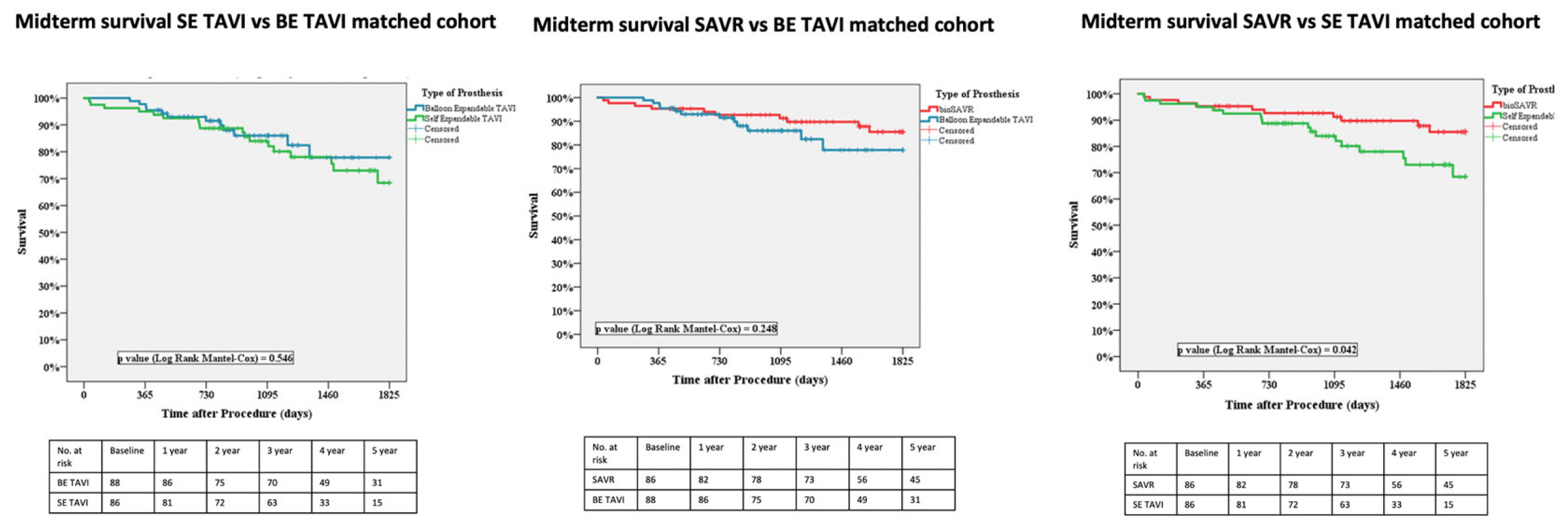

Regarding midterm survival no significant differences were reported between SE and BE TAVI (77.5% vs. 86.4%, p=0.546).

When comparing surgery with TAVI, SE prostheses were associated with a significantly lower midterm survival than surgical bioprostheses (77.5% vs. 88.2%, p=0.042). Instead, BE prostheses demonstrated their non inferiority in terms of midterm survival compared to surgery (86.4% vs. 88.2%, p=0.248).

Figure 1.

4. Discussion

The present study comprises a retrospective single-center PS matched comparison of post-procedural outcomes and midterm survival of low-risk patients with severe AS who underwent SAVR or BE TAVI or SE TAVI.

The main findings of this study are: (i) BE prosthesis show to be non-inferior to surgery for all-cause midterm mortality, whereas SE prostheses are associated with a significantly higher midterm mortality compared to SAVR; (ii) PVL is more common after TAVI compared to surgery with SE TAVI being associated with a significantly higher incidence of PVL when compared to BE prostheses; (iii) patients who received a SE TAVI are at higher risk of post-procedural stroke; (iv) risk of post-procedural LBBB is higher for all TAVI prostheses compared to surgery, but also significantly higher for SE compared to BE prostheses.

The encouraging results of recent RCTs[

1,

2] compared TAVI and SAVR in low-risk patients have accelerated the expansion of TAVI indication to include younger patients. As a result, the latest ESC/EACTS guidelines provides a Class I recommendation for TAVI in patients over 70 years or those with high surgical risk[

15].

Although the growing enthusiasm for transcatheter approaches, the broad use of TAVI in younger and low-risk patients remains controversial. TAVI has been linked to higher rates of new PM implantation, LBBB, PVL and stroke. While such risks may be considered acceptable in patients at prohibitive, high and intermediate surgical risk, their impact in patients with a longer life-expectancy is still a source of concern.

Furthermore, while the long-term durability of bioprosthetic surgical valves and the satisfactory life-expectancy after SAVR have been confirmed in several studies[

16,

17], for TAVI long-term durability beyond 5-8 years is poorly understood[

18,

19].

Recently, Thyregod and collogues, published the 10-year results of the NOTION trial[

20]. They found that in low-risk patients, the rate of major clinical outcomes was similar between SAVR and TAVI after 10 years. However, the incidence of severe structural valve deterioration was lower with TAVI. Despite these findings, the NOTION trial has several limitations. Like other RCTs, it included a highly selected patient population that does not reflect real-world scenarios. Moreover, it involved surgical bioprostheses such a Trifecta and Mitroflow, both known for poor long-term durability. Additionally, only a limited number of patients completed the 10-year follow up. These limitations weaken the comparison between TAVI and surgery, and the NOTION trial data are insufficient to support the use of TAVI in patients with long life-expectancy.

In this scenario, identifying the type of THV that can offer the optimal long-term outcomes and represent as a value alternative to surgery is becoming increasingly important.

Our results regarding the higher rate of PVL in SE TAVI, likely due to their lower radial force, are in line with literature.

In the CHIOCE trial the rate of more than mild aortic regurgitation was 18% in SE prostheses and 4% in BE prostheses[

21].

In their meta-analysis Sà and collogues compared last generation BE and SE valves. BE TAVI were associated with a significantly higher incidence of PVL when compared to SE prostheses (4.9% vs. 11.3%, p<0.001)[

22].

Lerman et al. performed a meta-analysis comparing short and midterm outcomes of BE and SE TAVI. 21 publications totaling 35.248 patients were included. The rate of moderate-severe PVL was significantly higher in patients with SE prostheses when compared to those with BE TAVI (8.1% vs. 4.4%, p<0.001)[

23].

The SOLVE TAVI is a multicentric randomized trial of 447 patients, undergoing TF TAVI, comparing SE and BE valves. It reports similar results in terms of moderate-severe PVL distribution between the two study group (SE group 3.4%; BE group 1.5%; p=0.001)[

24].

Van Belle and collogues compared the outcomes of BE and SE valves on a large nationwide registry[

6]. In the PS matched cohort, they found a significantly higher risk of PVL with SE TAVI when compared to BE TAVI, irrespective of valve generation.

PVL has been strongly related with poorer short and long-term outcomes[

25,

26].

The sudden onset of PVL following TAVI in patients with pre-existing severe AS, whose left ventricles are not adapted to volume overload, may explain the significant negative effect on PVL in this group of patients. While chronic aortic regurgitation can remain asymptomatic for years, even with left ventricle enlargement and dysfunction, acute aortic regurgitation due to PVL in a not “preconditioned” left ventricle can quickly lead to decompensed heart failure and adverse outcomes.

Furthermore, in our analysis, LBBB occurs more frequently in SE TAVI patients when compared to BE TAVI patients. Our results are in line with literature and related to the different implantation technique with a greater implantation depth in SE TAVI[

27,

28]. In their study, Bendandi and collogues aimed to elaborate a new score to predict the occurrence of conduction abnormalities after TAVI and they identified SE TAVI as an independent predictor[

29].

It has been widely demonstrated that patients with new-onset persistent LBBB after TAVI have a greater risk of all-cause mortality, as well as a greater incidence of cardiovascular mortality, heart failure hospitalization and PM implantation[

30].

The higher rate of such complications in patients with SE prostheses, together with the higher incidence of post-procedural stroke, may explain their higher midterm mortality compared to surgery. On the other hand, the lower rate of post-procedural PVL, LBBB and stroke in BE valves compared to SE TAVI, should explain their non-inferiority in terms of midterm survival when compared to surgery.

Our results are corroborated by several studies reported in literature.

In the meta-analysis by Lerman and collogues, SE TAVI were associated with a significantly higher short term all-cause mortality when compared to BE TAVI (3.4% vs. 2,4%, p<0.001)[

23].

In their study, including 31.113 patients, Deharo et al. found that BE valves were associated with lower rates of all-cause mortality, cardiovascular death and re-hospitalization for heart failure compared with SE valves[

31].

Similar results were reported in a meta-analysis by Jacquermyn at al. including 26 studies. BE prostheses showed a better overall survival and a lower cardiovascular death when compared to SE prostheses[

32].

Furthermore, in their propensity score matched analysis Van Belle et al. demonstrated that the use of SE valves was associated with a significantly higher in-hospital and 2-year mortality compared to BE valves[

6].

Finally, when approaching TAVI in younger lower risk patients, it is important to keep in mind that these patients are at high-risk of requiring subsequent coronary angiography and percutaneous coronary interventions.

Several retrospective and single center studies have reported difficulties in coronary access after TAVI with tall-frame compared with short-frame TAVI[

33,

34].

These results have been recently confirmed by the CAvEAT registry[

35], which demonstrated a clear advantage in coronary re-access of BE TAVI, with their intra-annular, short-frame design minimizing interference with coronary ostia.

The primary limitation of our study is its retrospective, observational design, and the absence of randomization. Although a propensity score matching was applied to ensure comparable and balanced risk profiles between the 3 groups, the influence of unmeasured confounding variables on outcomes cannot be entirely ruled out. Another limitation is the small sample size, which is due to the study single-center design. Furthermore, the midterm follows up period is limited and a longer follow-up period is mandatory to better understand long-term outcomes in low risk patients with longer life expectation.

5. Conclusions

Despite technical advancements and device innovation, conduction abnormalities and PVL remain the TAVI Achille’s hell.

With the extension of TAVI indication to patients with long life-expectancy, it has become crucial to identify the type of transcatheter prosthesis which can offer the best long-term outcomes and serve as a valid alternative to surgery.

Based on our analysis, BE prostheses should be considered the prostheses of choice for patients with long life-expectancy requiring a transcatheter procedure. Indeed, BE valves showed a lower rate of peri-procedural complications when compared to SE valves and demonstrated their non inferiority in terms of midterm survival when compared to surgery. Obviously, further study with a longer follow up period are needed before routinely recommending BE TAVI for this category of patients.

Supplementary Materials

Table 1: overall population baseline characteristics and comorbidities. Table 2: overall population post-procedural outcomes.

Author Contributions

Lodo V: conceptualization, writing, methodology; Italiano EG: methodology, formal analysis ; Weltert L: methodology, formal analysis ; Zingarelli E: supervision, validation; Viscido E: supervision, validation; Buono G: supervision, validation; Centofanti P: conceptualization, supervision, validation.

Informed consent statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. .

Acknowledgments

Fondazione Scientifica Mauriziana onlus.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mack, M.J.; Leon, M.B.; Thourani, V.H.; Pibarot, P.; Hahn, R.T.; Genereux, P.; et al. Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Replacement in Low-Risk Patients at Five Years. N Engl J Med. 2023, 389, 1949–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrest, J.K.; Deeb, G.M.; Yakubov, S.J.; Gada, H.; Mumtaz, M.A.; Ramlawi, B.; et al. 3-Year Outcomes After Transcatheter or Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement in Low-Risk Patients With Aortic Stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023, 81, 1663–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotman, O.M.; Bianchi, M.; Ghosh, R.P.; Kovarovic, B.; Bluestein, D. Principles of TAVR valve design, modelling, and testing. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2018, 15, 771–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Mei, Z.; Ge, X.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Meng, X.; et al. Comparison of outcomes of self-expanding versus balloon-expandable valves for transcatheter aortic valve replacement: a meta-analysis of randomized and propensity-matched studies. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2023, 23, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vollenbroich, R.; Wenaweser, P.; Macht, A.; Stortecky, S.; Praz, F.; Rothenbühler, M.; et al. Long-term outcomes with balloon-expandable and self-expandable prostheses in patients undergoing transfemoral transcatheter aortic valve implantation for severe aortic stenosis. Int J Cardiol. 2019, 290, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Belle, E.; Vincent, F.; Labreuche, J.; Auffret, V.; Debry, N.; Lefèvre, T.; et al. Balloon-Expandable Versus Self-Expanding Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement: A Propensity-Matched Comparison From the FRANCE-TAVI Registry. Circulation. 2020, 141, 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinsson, A.; Nielsen, S.J.; Milojevic, M.; Redfors, B.; Omerovic, E.; Tønnessen, T.; et al. Life Expectancy After Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021, 78, 2147–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francica, A.; Benvegnù, L.; San Biagio, L.; Tropea, I.; Luciani, G.B.; Faggian, G.; Onorati, F. Ten-year clinical and echocardiographic follow-up of third-generation biological prostheses in the aortic position. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2024, 167, 1705–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nashef SA, Roques F, Sharples LD, Nilsson J, Smith C, Goldstone AR, et al EuroSCORE II. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2012; 41:734-44.

- O'Brien, S.M.; Shahian, D.M.; Filardo, G.; Ferraris, V.A.; Haan, C.K.; Rich, J.B.; et al. Society of Thoracic Surgeons Quality Measurement Task Force. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons 2008 cardiac surgery risk models: part 2-isolated valve surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009, 88 (1 Suppl), S23–S42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodo, V.; Italiano, E.G.; Weltert, L.; Zingarelli, E.; Pietropaolo, C.; Buono, G.; et al. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation versus surgery in low-risk patients: in-hospital and mid-term outcomes. Interdiscip Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2025, 40, ivaf103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lodo, V.; Italiano, E.G.; Weltert, L.; Zingarelli, E.; Perrucci, C.; Pietropaolo, C.; et al. The influence of gender on outcomes following transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2024, 11, 1417430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levey, A.S.; Eckardt, K.U.; Tsukamoto, Y.; Levin, A.; Coresh, J.; Rossert, J.; et al. Definition and classification of chronic kidney disease: a position statement from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int. 2005, 67, 2089–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thygesen, K.; Alpert, J.S.; Jaffe, A.S.; Chaitman, B.R.; Bax, J.J.; et al. ESC Scientific Document Group. Fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction (2018). Eur Heart J. 2019, 40, 237–269. [Google Scholar]

- Praz, F.; Borger, M.A.; Lanz, J.; Marin-Cuartas, M.; Abreu, A.; Adamo, M.; et al. ESC/EACTS Scientific Document Group. 2025 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2025, ehaf194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, N.; Persson, M.; Jackson, V.; Holzmann, M.J.; Franco-Cereceda, A.; Sartipy, U. Loss in Life Expectancy After Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement: SWEDEHEART Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019, 74, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroutan, F.; Guyatt, G.H.; O'Brien, K.; Bain, E.; Stein, M.; Bhagra, S.; et al. Prognosis after surgical replacement with a bioprosthetic aortic valve in patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis: systematic review of observational studies. BMJ. 2016, 28, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Søndergaard L, Ihlemann N, Capodanno D, Jørgensen TH, Nissen H, Kjeldsen BJ, et al Durability of Transcatheter and Surgical Bioprosthetic Aortic Valves in Patients at Lower Surgical Risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019, 73, 546–553. [CrossRef]

- Barbanti M, Costa G, Zappulla P, Todaro D, Picci A, Rapisarda G, Di Simone E, et al Incidence of Long-Term Structural Valve Dysfunction and Bioprosthetic Valve Failure After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018, 7, e008440. [CrossRef]

- Thyregod, H.G.H.; Jørgensen, T.H.; Ihlemann, N.; Steinbrüchel, D.A.; Nissen, H.; Kjeldsen, B.J.; et al. Transcatheter or surgical aortic valve implantation: 10-year outcomes of the NOTION trial. Eur Heart J. 2024, 45, 1116–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Wahab, M.; Mehilli, J.; Frerker, C.; Neumann, F.J.; Kurz, T.; Tölg, R.; et al. Comparison of balloon-expandable vs. self-expandable valves in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement: the CHOICE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014, 311, 1503–1514. [Google Scholar]

- Sá, M.P.B.O.; Simonato, M.; Van den Eynde, J.; Cavalcanti, L.R.P.; Alsagheir, A.; Tzani, A.; et al. Balloon versus self-expandable transcatheter aortic valve implantation for bicuspid aortic valve stenosis: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2021, 98, E746–E757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerman, T.T.; Levi, A.; Kornowski, R. Meta-analysis of short- and long-term clinical outcomes of the self-expanding Evolut R/pro valve versus the balloon-expandable Sapien 3 valve for transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Int J Cardiol. 2023, 371, 100–108. [Google Scholar]

- Thiele, H.; Kurz, T.; Feistritzer, H.J.; Stachel, G.; Hartung, P.; Eitel, I.; et al. Comparison of newer generation self-expandable vs. balloon-expandable valves in transcatheter aortic valve implantation: the randomized SOLVE-TAVI trial. Eur Heart J. 2020, 41, 1890–1899. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bhushan, S.; Huang, X.; Li, Y.; He, S.; Mao, L.; Hong, W.; Xiao, Z. Paravalvular Leak After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation Its Incidence, Diagnosis, Clinical Implications, Prevention, Management, and Future Perspectives: A Review Article. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2021, 100957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sá, M.P.; Jacquemyn, X.; Van den Eynde, J.; Tasoudis, P.; Erten, O.; et al. Impact of Paravalvular Leak on Outcomes After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation: Meta-Analysis of Kaplan-Meier-derived Individual Patient Data. Struct Heart. 2022, 7, 100118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Coeman, M.; Kayaert, P.; Philipsen, T.; Calle, S.; Gheeraert, P.; Gevaert, S.; et al. Different dynamics of new-onset electrocardiographic changes after balloon- and self-expandable transcatheter aortic valve replacement: Implications for prolonged heart rhythm monitoring. J Electrocardiol. 2020, 59, 68–73. [Google Scholar]

- Auffret, V.; Puri, R.; Urena, M.; Chamandi, C.; Rodriguez-Gabella, T.; Philippon, F.; et al. Conduction Disturbances After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement: Current Status and Future Perspectives. Circulation. 2017, 136, 1049–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendandi, F.; Taglieri, N.; Ciurlanti, L.; Mazzapicchi, A.; Foroni, M.; Lombardi, L.; et al. Development and validation of the D-PACE scoring system to predict delayed high-grade conduction disturbances after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. EuroIntervention. 2025, 21, e119–e129. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, K.; Ahmed, M.; Brieger, D.; Baer, A.; Hansen, P.; Bhindi, R. The Prognostic Relevance of a New Bundle Branch Block After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Struct Heart. 2024, 9, 100392. [Google Scholar]

- Deharo, P.; Bisson, A.; Herbert, J.; Lacour, T.; Saint Etienne, C.; Grammatico-Guillon, L.; et al. Impact of Sapien 3 Balloon-Expandable Versus Evolut R Self-Expandable Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation in Patients With Aortic Stenosis: Data From a Nationwide Analysis. Circulation. 2020, 141, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquemyn, X.; Van den Eynde, J.; Caldonazo, T.; Brown, J.A.; Dokollari, A.; Serna-Gallegos, D.; Clavel, M.A.; et al. Late Outcomes After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation with Balloon-Versus Self-Expandable Valves: Meta-Analysis of Reconstructed Time-To-Event Data. Cardiol Clin. 2024, 42, 373–387. [Google Scholar]

- Yudi, M.B.; Sharma, S.K.; Tang, G.H.L.; Kini, A. Coronary Angiography and Percutaneous Coronary Intervention After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018, 71, 1360–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochiai, T.; Chakravarty, T.; Yoon, S.H.; Kaewkes, D.; Flint, N.; Patel, V.; et al. Coronary Access After TAVR. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020, 13, 693–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarantini, G.; Nai Fovino, L.; Belloni, F.; Barbierato, M.; Gallo, F.; Vercellino, M.; et al. The Coronary Access After TAVI (CAvEAT) Study: A Prospective Registry of CA After TAVR. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2025, 18, 1571–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).