1. Introduction

Surgical bioprosthetic valves are widely utilized for surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) due to their favorable hemodynamic profile and the avoidance of lifelong anticoagulation requirements [

1]. Their use has increased significantly, now accounting for approximately 80% of SAVR procedures [

2]. However, bioprosthetic valves are inherently limited by structural valve degeneration (SVD), leading to progressive dysfunction over time. When bioprosthetic valve failure occurs, redo SAVR remains an option but is associated with substantial procedural risk, with reported operative mortality rates ranging from 2% to 7%, escalating to as high as 30% in elderly and high-risk patients [

3]. Consequently, valve-in-valve (ViV) transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) has emerged as the preferred alternative for such patients, offering a minimally invasive approach with favorable early and mid-term outcomes [

4,

5,

6].

Despite the procedural advantages of ViV TAVI, it poses specific technical and clinical challenges that must be considered. These include an increased risk of coronary obstruction, elevated post-procedural transvalvular gradients, permanent pacemaker implantation (PPI), and patient-prosthesis mismatch (PPM). The selection of the most appropriate transcatheter heart valve (THV) is therefore critical in optimizing both procedural success and long-term clinical outcomes.

The primary differences between self-expanding (SE) and balloon-expandable (BE) valves in the ViV setting pertain to their hemodynamic performance and risk profiles. SE valves, due to their supra-annular design, generally achieve a larger post-implantation aortic valve area (AVA) and lower incidence of PPM, making them advantageous in cases where elevated gradients are a concern; however, this comes at the cost of an increased risk of PPI and coronary obstruction, particularly in patients with low coronary ostia or externally mounted bioprosthetic leaflets [

7,

8]. While the most widely used SE valve for ViV TAVI is Evolut™ (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA), ACURATE neo2 (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA) offers design modifications that may mitigate some of the risks associated with self-expanding THVs while introducing potential advantages over Evolut. Specifically, ACURATE neo2 retains the supra-annular design while incorporating an open-cell frame structure, which facilitates commissural alignment and preserves coronary access, thereby reducing the risk of coronary obstruction. Additionally, its stable positioning and simplified deployment mechanism makes it user friendly, along with a lower incidence of conduction disturbances and PPI, an important advantage over other SE valves.

While the performance of the ACURATE neo2 valve in native aortic stenosis has been well-documented [

9,

10], data on its use in ViV TAVI remain limited. This study presents a single-center, single-operator experience evaluating the procedural success, hemodynamic performance, and short-to-mid-term outcomes of the ACURATE neo2 valve in ViV TAVI, providing valuable insights into the real-world feasibility and safety of this approach.

2. Materials and Methods

This is a single-center, single-operator, prospective, observational, cohort study that includes data from medical records of all patients that underwent transfemoral ViV TAVI at our structural heart disease expert center, from July 2022 to February 2024. The study has been approved by the Institutional Review Board of our center, in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Inclusion Criteria

All patients diagnosed with degenerated surgical bioprostheses and symptomatic valve dysfunction, classified in NYHA class III or IV, who underwent ViV TAVI with the ACURATE neo2 valve at our center between July 2022 and February 2024 at the Hybrid Operating Room at European Interbalkan Medical Center were included. The decision to carry out the transcatheter procedure was made by the local Heart Team, according to the 2021 ECS / EACTS guidelines [

11].

ViV TAVI procedure

The transfemoral ViV TAVI procedure was performed under general anesthesia in the Hybrid Operating Room of the Interbalkan Medical Center, utilizing the ACURATE neo2 (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA) by a single operator. Femoral artery access was obtained through surgical cut-down technique by the same vascular surgeon.

Crossing of the bioprosthetic valve was facilitated by a straight 0.035” wire through an Amplatz Left 1 or a Pigtail catheter. Balloon pre-dilation was performed in most cases using a balloon sized according to the true internal diameter of the surgical bioprosthesis. In patients with small prostheses (true ID < 21 mm), high-pressure balloon fracture was considered when applicable, using a non-compliant Atlas balloon (Bard Peripheral Vascular, Tempe, AZ, USA) prior to ACURATE neo2 deployment in order to optimize valve expansion and reduce residual gradients and to avoid high-pressure trauma to the ACURATE neo2 leaflets

ACURATE neo2 implantation followed a standardized top-down deployment approach, ensuring that the valve marker was aligned with the bioprosthetic valve annulus. Post-dilation was selectively performed in cases where suboptimal valve expansion, elevated residual gradients, or significant paravalvular regurgitation were observed. Following implantation, a pigtail catheter was positioned in the left ventricle to assess residual gradients and perform hemodynamic measurements, including diastolic pressures in the aorta and left ventricle.

In patients with low coronary artery takeoff, preemptive coronary protection was performed using guide catheters and coronary angioplasty wires. Elective chimney stenting was undertaken to preserve coronary flow, when necessary.

Definition of the variables

Baseline characteristics including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation II (EuroSCORE II), cardiopulmonary comorbidities (e.g., prior heart failure hospitalization, atrial fibrillation [AF], prior myocardial infarction [MI], diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, coronary artery disease [CAD] with prior PCI or coronary artery bypass graft surgery [CABG], chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD]), stroke, presence of permanent pacemaker, and NYHA class were recorded. Bioprosthetic surgical valve characteristics were also collected, including true ID, time to failure, degeneration mechanism, surgical valve manufacturer. Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) was conducted to assess left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), mean aortic valve gradient, aortic valve area (AVA), and aortic regurgitation (AR). AR severity classification comprises of trivial / mild, moderate, and severe. All TTEs were conducted by the same examiner. Procedural characteristics, including predilation, postdilation, SENTINEL cerebral protection system use, procedural time, and commissural alignment were also recorded.

In-hospital outcomes

In-hospital outcomes were reported according to the Valve Academic Research Consortium-3 (VARC-3) consensus [

12]. The main outcomes were technical success, in-hospital mortality, myocardial infarction (MI), percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), stroke, bleeding events, acute kidney injury (AKI), conversion to surgery, vascular complications, permanent pacemaker implantation (PPI), and post-procedural echocardiographic evaluation.

Short-to-mid-term outcomes

Short-to-mid-term clinical and echocardiographic outcomes were assessed at 30 days and 1 year post-procedure. Clinical follow-up included evaluation of functional status (NYHA class), heart failure hospitalizations, all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction (MI), and stroke.

Echocardiographic follow-up was conducted at 30 days and 1 year using transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) to assess mean aortic valve gradient, aortic valve area (AVA), and aortic regurgitation (AR). AR severity was classified as trivial / mild, moderate, or severe. All echocardiographic evaluations were performed by the same examiner.

Device-related complications, including bioprosthetic valve dysfunction (stenosis, regurgitation, or combined), valve thrombosis, endocarditis, and structural valve deterioration, were also recorded. Follow-up data were collected through hospital visits, outpatient clinic records, and telephone interviews with patients or referring physicians.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables following normal distribution were presented as mean and standard deviation (SD), while variables that were not distributed normally were presented as median and interquartile range (IQR). Normality of distribution was assessed by comparing mean and median values, graphical representation of the distribution of the variables and by using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Qualitative variables were summarized using absolute and relative frequencies [n/N (%)]. Comparisons of continuous variables between time points (e.g., pre-procedure, post-procedure, 30-day, and 1-year follow-up) were performed using repeated measures ANOVA for normally distributed data or the Friedman test for non-normally distributed variables. Pairwise comparisons were conducted using paired t-tests (if normal) or the Wilcoxon signed-rank test (if non-normal), with Bonferroni correction applied for multiple comparisons. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed on RStudio version 2023.03.0+386.

3. Results

A total of 55 patients (51% females) underwent transfemoral ViV TAVI with a median age of 76 years (IQR: 8), at baseline assessment. A comprehensive overview of the baseline characteristics of the patients is presented in

Table 1. This is a high surgical risk cohort with mean Euroscore II of 7.66 ± 0.9% and prevalent cardiopulmonary comorbidities, including hypertension (55%), dyslipidemia (67%), diabetes (27%), COPD (31%), and CAD (45%) (previous PCI [21%], CABG [24%], prior MI (13%), while 3 (5%) patients had a prior stroke and 11 (20%) had a permanent pacemaker. AF was present in 33% of patients. The failed surgical bioprostheses had mean true internal diameter (ID) of 22 ± 3 mm, with mean time to failure of 10.0 ± 4.1 years. The most common failure mechanism was stenosis (51%), followed by mixed degeneration (27%) and regurgitation (22%). The most frequently failed bioprosthetic valve was TRIFECTA (49%), followed by MAGNA EASE, MITROFLOW, and MOSAIC (each 14.5%). Pre-procedural echocardiography showed mean LVEF of 50 ±11%, mean aortic gradient of 38 ±11 mmHg, and AVA of 0.8 ±0.5 cm². Aortic regurgitation was trivial / mild in 31%, moderate in 40%, and severe in 39% of cases.

The technical success rate was 98.2%, with one patient requiring the implantation of a second ACURATE neo2 valve during the index procedure due to valve migration of the first following post dilation and severe paravalvular leak (PVL). Predilation was performed in 87% (in 5 [9%] cases the surgical valve was fractured), postdilation in 66%, and the SENTINEL cerebral protection system was used in all patients. The mean procedural time was 32 ± 5 minutes. There were no occurrences of stroke, bleeding, vascular complications, AKI, conversion to surgery, new pacemaker implantation, or in-hospital mortality. Additionally, none of the patients experienced myocardial infarction; however, 3 patients (5.5%) underwent elective percutaneous coronary intervention with chimney stenting—2 (3.6%) in the left main and 1 (1.8%) in both the left main and right coronary artery—due to low coronary takeoff and potential obstruction. The post-procedural mean aortic gradient was 6.7 ± 1 mmHg, with mean aortic valve area (AVA) of 2 ± 0.1 cm². No cases of aortic regurgitation greater than trivial were observed.

Short-to-Mid-Term Outcomes

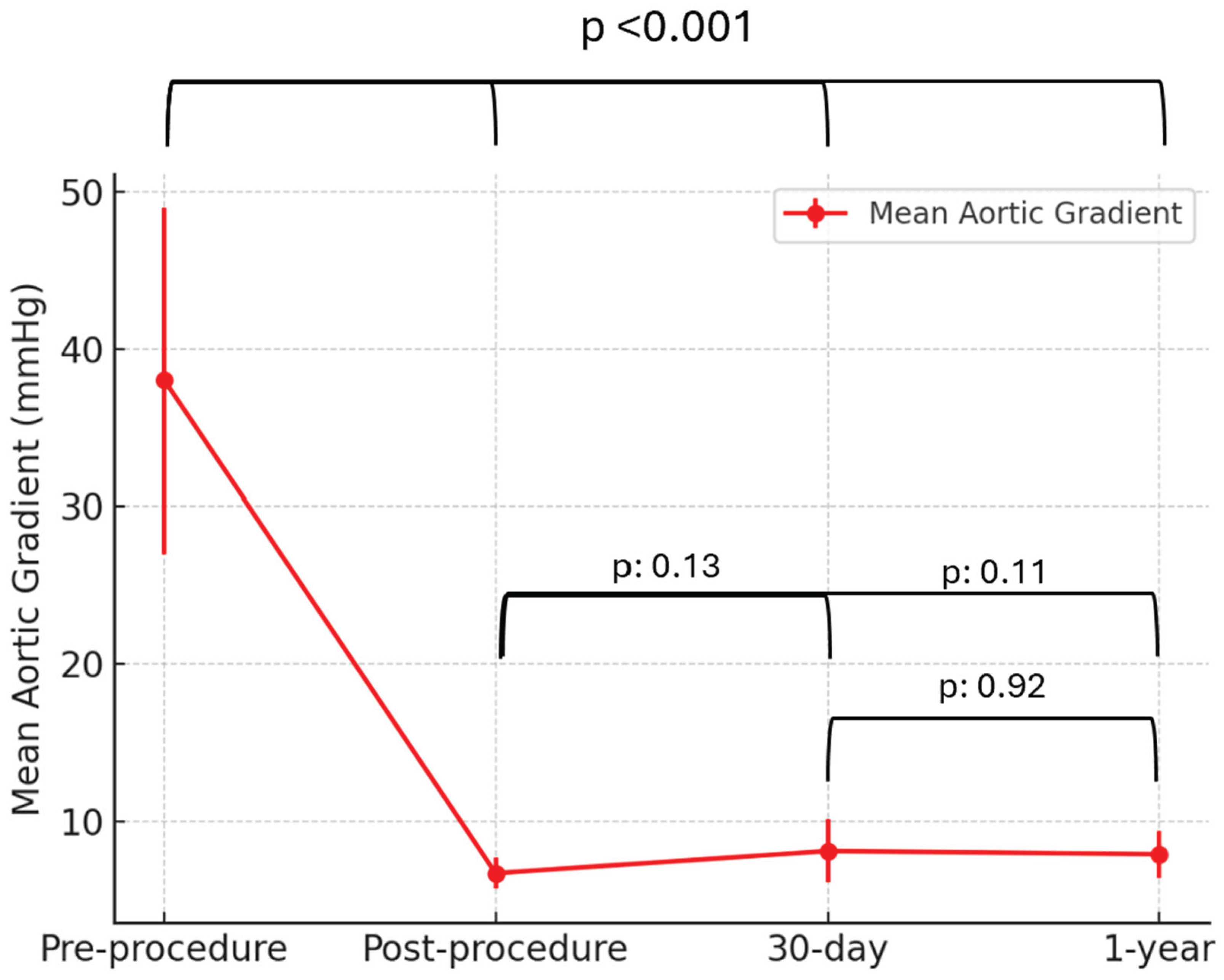

Over a median follow-up period of 1.2 years, no deaths, strokes, or MIs (0%) were observed, and the rate of heart failure-related hospitalizations was 3.6%. The mean aortic gradient demonstrated a significant reduction following ViV TAVI, decreasing from 38 ± 11 mmHg pre-procedure to 6.7 ± 1 mmHg post-procedure (p < 0.001). This reduction remained stable with 8.1 ± 2 mmHg at 30 days and 7.9 ± 1.5 mmHg at 1 year, with no significant differences between post-procedural, 30-day, and 1-year gradients (p: 0.13, p: 0.11, p: 0.92,

Figure 1).

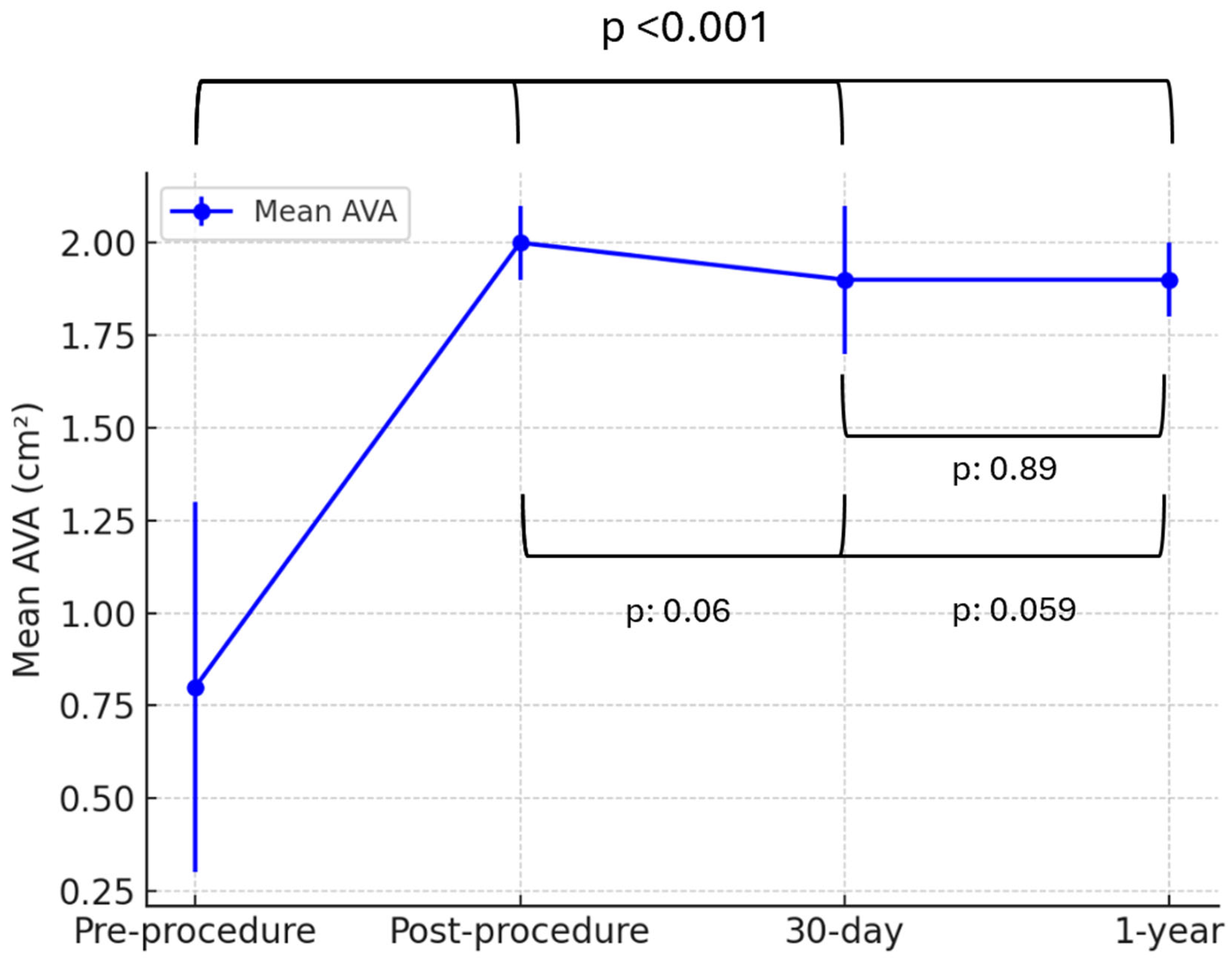

Similarly, the mean aortic valve area (AVA) significantly improved from 0.8 ± 0.5 cm² pre-procedure to 2.0 ± 0.1 cm² post-procedure (p < 0.001). AVA remained stable at follow-up, measuring 1.9 ± 0.2 cm² at 30 days and 1.9 ± 0.1 cm² at 1 year, with no significant differences between post-procedural, 30-day, and 1-year measurements (p: 0.89, p: 0.06, p: 0.059,

Figure 2).

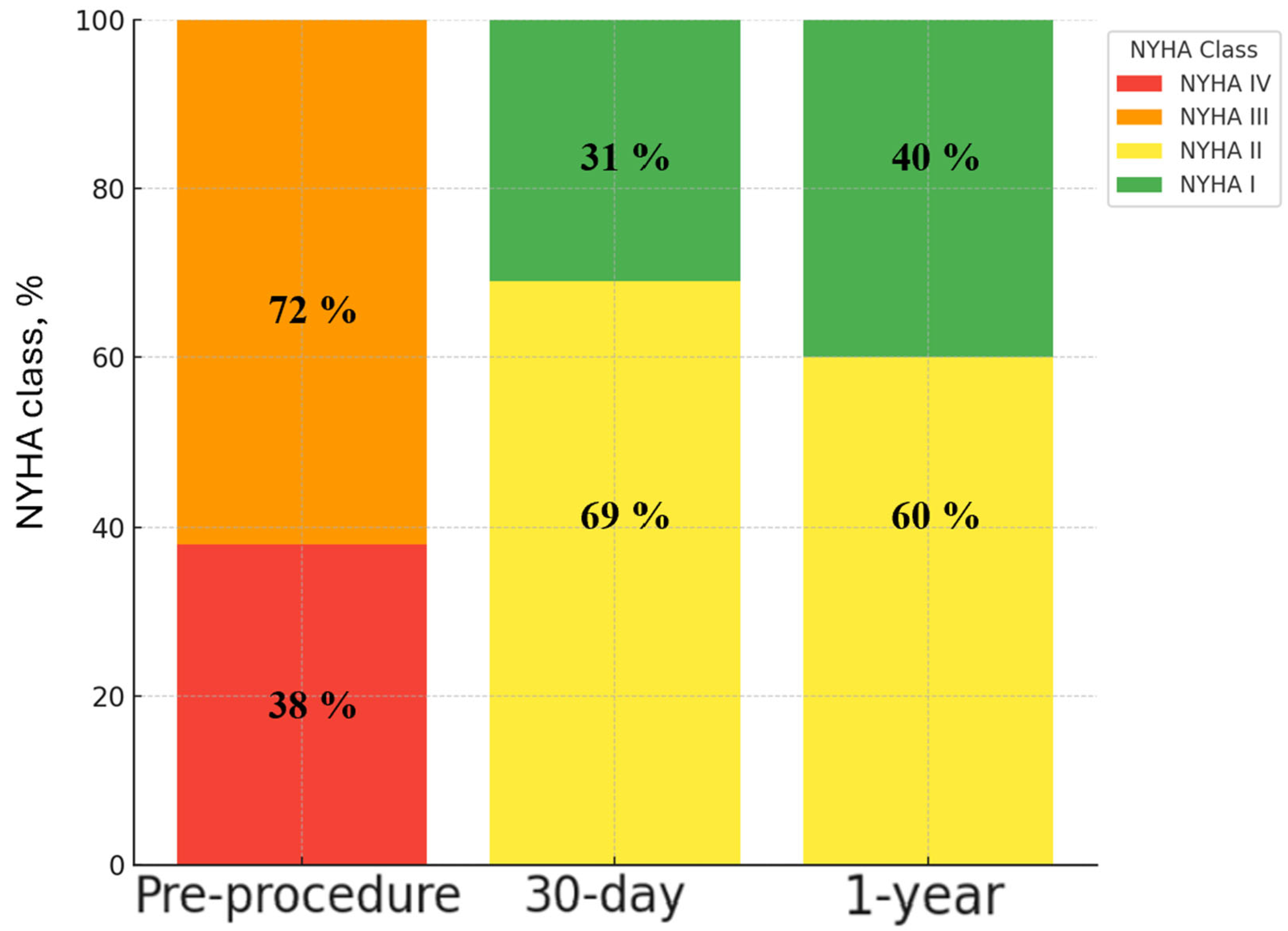

Significant functional improvement was observed following ViV TAVI, as reflected in the distribution of NYHA class over time (

Figure 3). Pre-procedurally, 72% of patients were in NYHA class III and 38% in NYHA class IV. At 30-day follow-up, there was a marked shift towards improved functional status, with 31% of patients in NYHA class I and 69% in NYHA class II, and no patients remaining in class III or IV. This trend continued at 1-year follow-up, with further functional improvement, as 40% of patients were classified as NYHA I and 60% as NYHA II.

4. Discussion

This study represents a significant contribution to the growing body of evidence on the use of the ACURATE neo2 valve in the ViV TAVI setting. While the AVENGER registry [

13] has provided valuable comparative data between ACURATE neo2 and Evolut in ViV TAVI, our study offers a distinct perspective by evaluating ACURATE neo2 in a dedicated single-center, single-operator setting. This controlled approach minimizes inter-operator variability and procedural heterogeneity, thereby allowing for a more precise assessment of the valve’s technical performance, safety profile, and short-to-mid-term hemodynamic outcomes.

Our findings confirm that ViV TAVI with ACURATE neo2 is associated with high technical success and excellent hemodynamic performance, as reflected by a substantial and sustained reduction in mean transvalvular gradients and a significant improvement in AVA. The supra-annular leaflet design, a defining characteristic of self-expanding THVs [

14], likely contributed to these favorable hemodynamic outcomes by allowing for larger effective orifice areas (EOA) and mitigating the risk of PPM, which remains a critical concern in the ViV setting, particularly in smaller surgical bioprostheses [

15], which in the VIVID (Valve-in-Valve International Data) registry were associated with increased mortality after ViV procedure [

16].

A key distinguishing feature of our study is the high rate of predilation, which is not generally recommended in ViV TAVI due to concerns about acute severe aortic insufficiency and haemodynamic instability [

17]. Nevertheless, in our cohort, this strategy was employed systematically, after the very first few cases, to optimize valve expansion and mitigate residual gradients. Additionally, in 5 cases, a deliberate strategy of bioprosthetic valve fracture was performed to enhance post-implantation valve function. This approach is increasingly recognized as a valuable adjunct in cases with small true internal diameters, as it may facilitate a larger final valve area and reduce post-procedural gradients [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23].

Importantly, in one case, migration of the initially implanted ACURATE neo2 necessitated the implantation of a second transcatheter valve, resulting in a successful valve-in-valve-in-valve (ViV-in-ViV) procedure. This finding underscores the feasibility of ViV-in-ViV as a bailout strategy in cases of valve migration or suboptimal positioning, particularly in bioprosthetic valves with low internal diameters or incomplete frame expansion. While ViV-in-ViV is not yet widely studied, its potential to restore optimal hemodynamics without requiring surgical conversion warrants further investigation.

From a safety standpoint, the absence of in-hospital mortality, myocardial infarction, major vascular complications, or new pacemaker implantation underscores the procedural feasibility of ACURATE neo2 in ViV TAVI. Another notable safety finding in this study was the absence of stroke (0%), which may be attributed to the routine use of the SENTINEL cerebral protection system in all patients. The SENTINEL device is designed to capture embolic debris that may arise during ViV TAVI, particularly in cases requiring predilation, bioprosthetic valve fracture, or postdilation—maneuvers that increase the risk of embolization. The complete prevention of clinically evident strokes in our cohort underscores the potential role of systematic SENTINEL use in reducing neurological complications, suggesting that embolic protection may be particularly beneficial in ViV TAVI settings where pre-existing bioprosthetic calcification and debris fragmentation may pose an increased risk of embolization [

24]. These findings align with prior studies that have suggested a protective effect of embolic protection devices, though larger trials are needed to confirm their impact on neurocognitive outcomes [

25,

26,

27,

28].

The importance of careful preprocedural planning is further highlighted by the requirement for PCI with chimney stenting in 5.5% of patients, owing to the risk of coronary obstruction, particularly in patients with low coronary takeoff or externally mounted leaflets. The open-cell frame design of ACURATE neo2 may provide an advantage in such cases, allowing for improved coronary access and commissural alignment, thereby reducing the complexity of bailout coronary interventions [

14].

The durability of hemodynamic improvements was evident at both 30-day and 1-year follow-up, with stable gradients and AVA, as well as significant functional improvement reflected in NYHA class. These findings suggest that ACURATE neo2 offers sustained clinical benefits beyond the peri-procedural period. Given the increasing reliance on ViV TAVI as an alternative to redo surgery, long-term durability data will be essential to establish the role of ACURATE neo2 in this patient population.

While our study provides important insights, certain limitations should be acknowledged. The single-center, single-operator nature of the study, while ensuring procedural consistency, may limit external validity. Additionally, the absence of a comparator group precludes direct assessment of ACURATE neo2 relative to other THVs in the ViV setting. Future multicenter studies, as well as head-to-head comparisons, will be necessary to further delineate the optimal THV choice in this context.

5. Conclusions

This study reinforces the feasibility, safety, and hemodynamic efficacy of ACURATE neo2 in ViV TAVI, with excellent short- and mid-term outcomes. The supra-annular design and open-cell frame structure contribute to favorable hemodynamics, while the low incidence of conduction disturbances and preserved coronary access are important procedural advantages. In the absence of large-scale data, our findings provide valuable real-world insights into the performance of ACURATE neo2 in a dedicated ViV TAVI setting. Further studies with long-term follow-up and comparative analyses are warranted to refine patient and device selection for optimal outcomes in this challenging patient population.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.P. and V.N.; methodology, G.P. and V.N.; software, G.P. and V.N.; validation, G.P. and V.N.; formal analysis, G.P. and V.N.; investigation, I.N., S.E., A.I., A.N., G.G. and V.N.; resources, G.P. and V.N.; data curation, G.P. and V.N.; writing—original draft preparation, G.P.; writing—review and editing, V.N.; visualization, G.P. and V.N.; supervision, V.N.; project administration, V.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Interbalkan Medical Center (protocol code 2335/9.9.2024)

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AF |

Atrial Fibrillation |

| AKI |

Acute Kidney Injury |

| AR |

Aortic Regurgitation |

| AVA |

Aortic Valve Area |

| BE |

Balloon-Expandable (valve) |

| BMI |

Body Mass Index |

| CABG |

Coronary Artery Bypass Graft surgery |

| CAD |

Coronary Artery Disease |

| COPD |

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

| EACTS |

European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery |

| ECS |

European Society of Cardiology |

| EOA |

Effective Orifice Area |

| EuroSCORE II |

European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation II |

| eGFR |

Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate |

| IQR |

Interquartile Range |

| ID |

True Internal Diameter |

| LM |

Left Main (coronary artery) |

| LVEF |

Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction |

| MI |

Myocardial Infarction |

| NYHA |

New York Heart Association (functional class) |

| PCI |

Percutaneous Coronary Intervention |

| PPI |

Permanent Pacemaker Implantation |

| PPM |

Patient-Prosthesis Mismatch |

| PVL |

Paravalvular Leak |

| RCA |

Right Coronary Artery |

| SAVR |

Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement |

| SE |

Self-Expanding (valve) |

| SENTINEL |

Sentinel Cerebral Protection System |

| SVD |

Structural Valve Degeneration |

| TAVI |

Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation |

| THV |

Transcatheter Heart Valve |

| TTE |

Transthoracic Echocardiography |

| VARC-3 |

Valve Academic Research Consortium-3 |

References

- Vesely I. The evolution of bioprosthetic heart valve design and its impact on durability. Cardiovascular Pathology. 2003;12(5):277-86. [CrossRef]

- JM B. Isolated aortic valve replacement in North America comprising 108,687 patients in 10 years: Changes in risks, valve types, and outcomes in the Society of Thoracic Surgeons National Database. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;137:82-90.

- Piazza N, Bleiziffer S, Brockmann G, Hendrick R, Deutsch M-A, Opitz A, et al. Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation for Failing Surgical Aortic Bioprosthetic Valve. JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions. 2011;4(7):721-32.

- Grube E, Buellesfeld L, Mueller R, Sauren B, Zickmann B, Nair D, et al. Progress and current status of percutaneous aortic valve replacement: results of three device generations of the CoreValve Revalving system. Circulation: Cardiovascular Interventions. 2008;1(3):167-75. [CrossRef]

- Piazza N, Grube E, Gerckens U, den Heijer P, Linke A, Luha O, et al. Procedural and 30-day outcomes following transcatheter aortic valve implantation using the third generation (18 Fr) corevalve revalving system: results from the multicentre, expanded evaluation registry 1-year following CE mark approval. EuroIntervention: journal of EuroPCR in collaboration with the Working Group on Interventional Cardiology of the European Society of Cardiology. 2008;4(2):242-9. [CrossRef]

- Webb JG, Altwegg L, Boone RH, Cheung A, Ye J, Lichtenstein S, et al. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation: impact on clinical and valve-related outcomes. Circulation. 2009;119(23):3009-16.

- Buono A, Zito A, Kim WK, Fabris T, De Biase C, Bellamoli M, et al. Balloon-Expandable vs Self-Expanding Valves for Transcatheter Treatment of Sievers Type 1 Bicuspid Aortic Stenosis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Lee H-A, Chou A-H, Wu VC-C, Chen D-Y, Lee H-F, Lee K-T, et al. Balloon-expandable versus self-expanding transcatheter aortic valve replacement for bioprosthetic dysfunction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE. 2020;15(6):e0233894. [CrossRef]

- Kim W-K, Hengstenberg C, Hilker M, Kerber S, Schäfer U, Rudolph T, et al. The SAVI-TF registry: 1-year outcomes of the European post-market registry using the ACURATE neo transcatheter heart valve under real-world conditions in 1,000 patients. JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions. 2018;11(14):1368-74.

- Toggweiler S, Nissen H, Mogensen B, Cuculi F, Fallesen C, Veien KT, et al. Very low pacemaker rate following ACURATE neo transcatheter heart valve implantation. EuroIntervention. 2017;13(11):1273-80. [CrossRef]

- Vahanian A, Beyersdorf F, Praz F, Milojevic M, Baldus S, Bauersachs J, et al. 2021 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease: Developed by the Task Force for the management of valvular heart disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). European Heart Journal. 2021;43(7):561-632. [CrossRef]

- Généreux P, Piazza N, Alu MC, Nazif T, Hahn RT, Pibarot P, et al. Valve Academic Research Consortium 3: Updated Endpoint Definitions for Aortic Valve Clinical Research. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2021;77(21):2717-46. [CrossRef]

- Kim WK, Seiffert M, Rück A, Leistner DM, Dreger H, Wienemann H, et al. Comparison of two self-expanding transcatheter heart valves for degenerated surgical bioprostheses: the AVENGER multicentre registry. EuroIntervention. 2024;20(6):e363-e75. [CrossRef]

- Barbanti M, Pagnesi M, Costa G, Latib A. Self-expanding transcatheter aortic valves. The PCR-EAPCI Textbook [Internet]. 2019 May 17. Available from: https://textbooks.pcronline.com/the-pci-textbook/self-expanding-transcatheter-aortic-valves.

- Pibarot P, Simonato M, Barbanti M, Linke A, Kornowski R, Rudolph T, et al. Impact of Pre-Existing Prosthesis-Patient Mismatch on Survival Following Aortic Valve-in-Valve Procedures. JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions. 2018;11(2):133-41. [CrossRef]

- Dvir D, Webb JG, Bleiziffer S, Pasic M, Waksman R, Kodali S, et al. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation in failed bioprosthetic surgical valves. Jama. 2014;312(2):162-70. [CrossRef]

- Chakravarty T, Cox J, Abramowitz Y, Israr S, Uberoi A, Yoon S, et al. High-pressure post-dilation following transcatheter valve-in-valve implantation in small surgical valves. EuroIntervention. 2018;14(2):158-65. [CrossRef]

- Allen KB, Chhatriwalla AK, Cohen DJ, Saxon JT, Aggarwal S, Hart A, et al. Bioprosthetic Valve Fracture to Facilitate Transcatheter Valve-in-Valve Implantation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;104(5):1501-8. [CrossRef]

- Chhatriwalla AK, Allen KB, Saxon JT, Cohen DJ, Aggarwal S, Hart AJ, et al. Bioprosthetic Valve Fracture Improves the Hemodynamic Results of Valve-in-Valve Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10(7). [CrossRef]

- Johansen P, Engholt H, Tang M, Nybo RF, Rasmussen PD, Nielsen-Kudsk JE. Fracturing mechanics before valve-in-valve therapy of small aortic bioprosthetic heart valves. EuroIntervention. 2017;13(9):e1026-e31. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen-Kudsk JE, Andersen A, Therkelsen CJ, Christensen EH, Jensen KT, Krusell LR, et al. High-pressure balloon fracturing of small dysfunctional Mitroflow bioprostheses facilitates transcatheter aortic valve-in-valve implantation. EuroIntervention. 2017;13(9):e1020-e5. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen-Kudsk JE, Christiansen EH, Terkelsen CJ, Nørgaard BL, Jensen KT, Krusell LR, et al. Fracturing the Ring of Small Mitroflow Bioprostheses by High-Pressure Balloon Predilatation in Transcatheter Aortic Valve-in-Valve Implantation. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8(8):e002667. [CrossRef]

- Tanase D, Grohmann J, Schubert S, Uhlemann F, Eicken A, Ewert P. Cracking the ring of Edwards Perimount bioprosthesis with ultrahigh pressure balloons prior to transcatheter valve in valve implantation. Int J Cardiol. 2014;176(3):1048-9. [CrossRef]

- Macherey S, Meertens M, Mauri V, Frerker C, Adam M, Baldus S, et al. Meta-Analysis of Stroke and Mortality Rates in Patients Undergoing Valve-in-Valve Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2021;10(6):e019512.

- Haussig S, Mangner N, Dwyer MG, Lehmkuhl L, Lücke C, Woitek F, et al. Effect of a cerebral protection device on brain lesions following transcatheter aortic valve implantation in patients with severe aortic stenosis: the CLEAN-TAVI randomized clinical trial. Jama. 2016;316(6):592-601.

- Kapadia SR, Kodali S, Makkar R, Mehran R, Lazar RM, Zivadinov R, et al. Protection against cerebral embolism during transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2017;69(4):367-77.

- Lansky AJ, Schofer J, Tchetche D, Stella P, Pietras CG, Parise H, et al. A prospective randomized evaluation of the TriGuard™ HDH embolic DEFLECTion device during transcatheter aortic valve implantation: results from the DEFLECT III trial. European heart journal. 2015;36(31):2070-8. [CrossRef]

- Seeger J, Gonska B, Otto M, Rottbauer W, Wöhrle J. Cerebral embolic protection during transcatheter aortic valve replacement significantly reduces death and stroke compared with unprotected procedures. JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions. 2017;10(22):2297-303. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).