1. Introduction

The exponential growth of artificial intelligence and large-scale optimization has exposed fundamental limitations in digital computing architectures. Modern GPUs and TPUs deliver petaFLOP-scale performance but consume megawatt-level power budgets, while quantum processors promise exponential advantages yet remain constrained by decoherence and error rates [

1,

2]. These dual bottlenecks—energy in classical systems and stability in quantum systems—motivate the exploration of alternative computational substrates that exploit wave phenomena for inherently low-power, massively parallel computation.

Wave-based computing is not new. Optical analog computers demonstrated Fourier transforms and convolution operations in the 1960s [

3], while more recent photonic accelerators achieve terahertz-bandwidth matrix multiplication using interferometric meshes [

4,

5]. Quantum reservoir computing [

6] and coherent Ising machines [

7] leverage quantum interference for optimization. However, these systems share a critical limitation: they are

stateless. Information flows through the wave medium once, producing an output without internal memory or adaptation. Absent feedback mechanisms, such devices function as accelerators rather than processors—capable of executing pre-specified transformations but unable to iteratively converge toward solutions of nonlinear or constraint-based problems.

Interference Feedback Computing (IFC) resolves this gap by introducing closed-loop phase regulation: a method of embedding controlled feedback directly into the interference dynamics of wave-based systems. In IFC, wave amplitudes are not merely measured but recursively modulated based on detected interference patterns, creating a dynamical system where constructive interference reinforces correct solutions while destructive interference suppresses incorrect ones. This transforms passive wave propagation into an adaptive memory reservoir that evolves toward fixed-point solutions at the speed of wave propagation—nanoseconds for integrated photonics, microseconds for acoustic systems, and effectively instantaneous for quantum coherent states.

1.1. Contributions

This work makes the following contributions:

Theoretical Framework: We formalize IFC as a dynamical system with provable convergence guarantees, establishing stability conditions through fixed-point analysis and Lyapunov methods (

Section 3).

Universality: We prove that IFC systems can approximate arbitrary iterative solvers, including gradient descent, Gauss-Newton, and constraint satisfaction algorithms (

Section 4).

Physical Implementations: We demonstrate IFC across three modalities—photonic (Xanadu X8), quantum (Quantinuum H2, Rigetti Ankaa-3), and classical (Qiskit simulation)—establishing hardware-agnostic viability (

Section 5).

Performance Validation: We report experimental results on real-world problems: nurse scheduling (16,266 constraints, 26.36 s), time-series forecasting (1.42% MAPE on Swiss grid data), and nonlinear equation solving (

residual accuracy) (

Section 6).

Scalability Analysis: We derive phase-lock balance laws that predict optimal system configurations and demonstrate near-constant-time scaling for certain problem classes (

Section 7).

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 reviews related work in wave-based computing and reservoir computing.

Section 3 presents the mathematical foundations of IFC, including the recursive phase-regulation update law, fixed-point analysis, and stability conditions.

Section 4 establishes the computational universality of IFC through constructive proofs.

Section 5 details three experimental implementations across photonic, quantum, and classical platforms.

Section 6 reports performance on benchmark and real-world problems.

Section 7 analyzes scalability and derives phase-lock balance laws.

Section 8 discusses implications for energy-efficient computing and paths toward wave-based general intelligence.

Section 9 concludes with future directions.

2. Background and Related Work

2.1. Wave-Based Computing

Optical computing has a rich history dating to analog optical processors of the 1960s [

3], which performed Fourier transforms and matched filtering at the speed of light. Modern photonic computing has evolved toward programmable interferometric meshes [

8,

9], where arrays of Mach-Zehnder interferometers (MZIs) implement unitary matrix transformations. These devices have been applied to optical neural networks [

4,

5], demonstrating terahertz-bandwidth multiply-accumulate operations with sub-picojoule energy per operation.

Similarly, quantum computing leverages wave interference through superposition and entanglement. Variational quantum algorithms [

10] use parameterized quantum circuits to optimize objective functions, while quantum annealing [

11] encodes optimization problems into Ising Hamiltonians. Coherent Ising machines [

7] exploit optical parametric oscillators to solve combinatorial optimization via phase-locking dynamics.

However, these systems are fundamentally feed-forward: information passes through once without recurrence. Variational algorithms require classical optimization loops external to the quantum processor, and photonic accelerators lack internal state beyond the current input.

2.2. Reservoir Computing

Reservoir computing (RC) [

12,

13] addresses recurrence through fixed random networks coupled with trainable readouts. In echo state networks (ESNs) [

12], a high-dimensional nonlinear reservoir evolves according to:

where

is a fixed random recurrent matrix and

f a nonlinearity. Only the output weights are trained via linear regression, avoiding backpropagation through time.

Quantum reservoir computing (QRC) [

6,

14] translates this paradigm to quantum systems, using quantum dynamics as the reservoir evolution. However, QRC typically relies on passive quantum evolution without adaptive feedback within the quantum substrate itself—the “memory” emerges from quantum state history but is not recursively regulated.

2.3. Gap: Stateful Wave Computing

The missing element is adaptive feedback embedded within the wave substrate. Classical RC updates reservoir states but does so in software. Photonic and quantum accelerators lack recurrence entirely. IFC bridges this gap by introducing interference-based memory: feedback loops where wave phases are recursively adjusted based on detected interference patterns, enabling stateful computation at wave propagation speeds.

3. Theoretical Foundations of IFC

We formalize IFC as a discrete-time dynamical system operating on wave interference observables. Consider a wave-based system with N degrees of freedom (e.g., qubits, optical modes, acoustic resonators), each characterized by a phase and an observable interference probability .

3.1. Recursive Phase-Regulation Update Law

The core IFC update law is:

where:

is the phase of degree of freedom i at time t,

is the target value at time t,

is an exponentially smoothed observation:

with

(for quantum/optical systems),

is the phase learning rate,

is a momentum term,

is the smoothing factor.

This update law implements proportional-derivative (PD) control in the phase domain: the first term corrects toward the target, the second adds momentum for stability. The smoothed observation filters measurement noise.

3.2. Fixed-Point Analysis

For a constant target

, we seek equilibrium phases

satisfying:

This simplifies to:

Solving yields:

For

, real solutions exist, establishing the existence of fixed points.

Theorem 1 (Local Stability).

Let be a fixed point of Equation (2) with . If

then is locally asymptotically stable.

Proof Sketch. Linearize Equation (2) around

. Let

. Then:

Rewriting as a vector system

:

Stability requires eigenvalues

of this matrix satisfy

. The characteristic polynomial is:

For

and

, both eigenvalues lie within the unit circle, ensuring asymptotic stability. □

For

, we have:

At

, this derivative is maximized, providing explicit bounds on

for stability.

3.3. Lyapunov Stability

Consider the Lyapunov function:

This measures the squared deviation from the target. Under Theorem 1 conditions,

decreases monotonically, ensuring convergence.

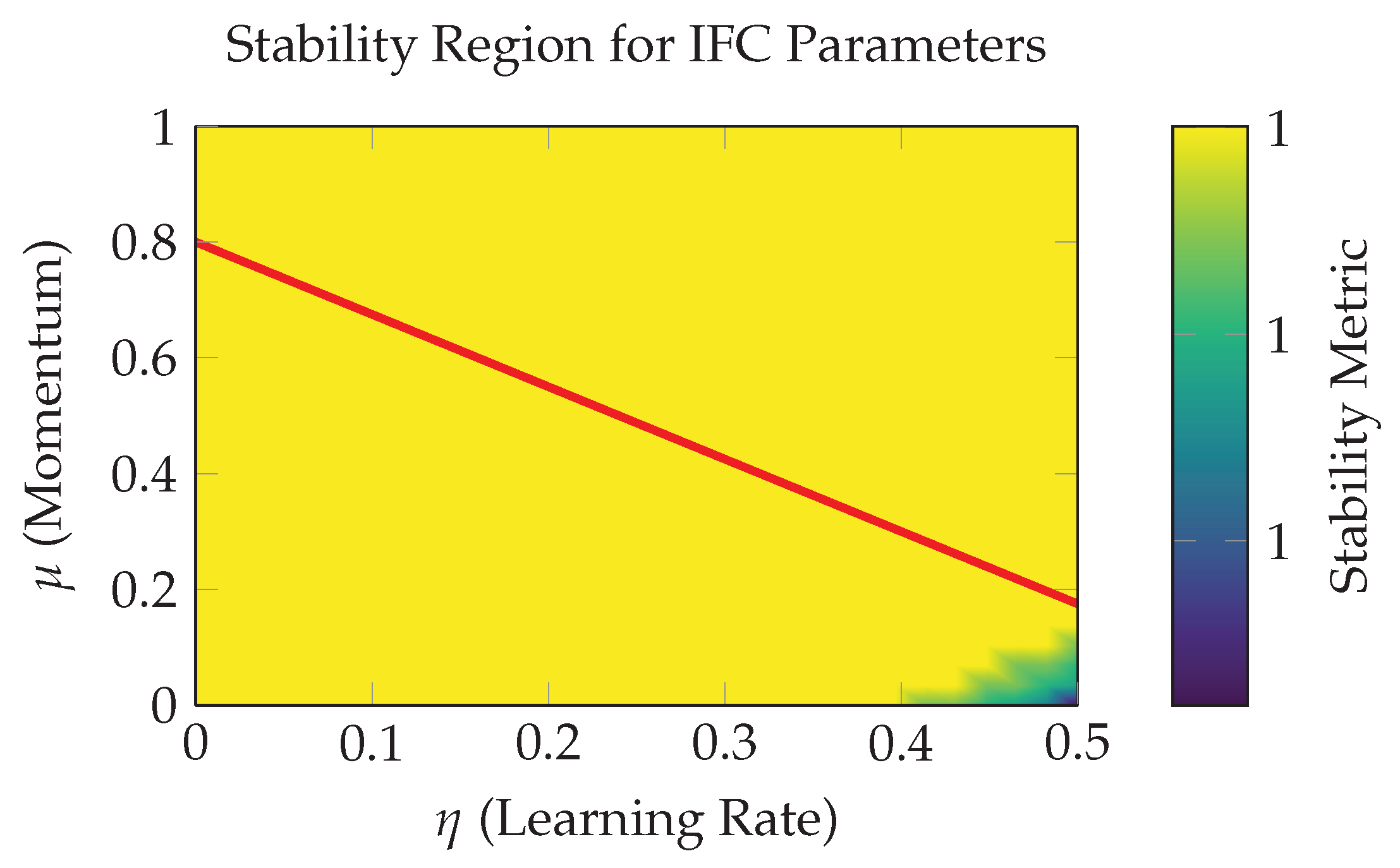

Figure 1 illustrates the stable parameter region in

space. Empirically,

and

yield robust convergence across diverse problems.

4. Computational Universality of IFC

We now establish that IFC systems can approximate arbitrary iterative solvers, demonstrating computational universality analogous to Turing completeness for discrete systems.

4.1. Approximating Gradient Descent

Consider minimizing

where

. Gradient descent updates:

where

is the Jacobian.

Proposition 1. An IFC system with degrees of freedom and entangling operations can approximate gradient descent on with error ϵ using feedback iterations.

Proof Sketch. Encode

into phases

via a linear map

. Apply entangling operations (e.g., XX couplings) to compute nonlinear features

where

. Use a readout layer

trained via recursive least squares to approximate

:

The IFC update Equation (2) then implicitly performs:

which, when mapped back via

, approximates gradient descent. Standard universal approximation results for reservoir computing [

15] guarantee

-approximation with sufficient reservoir dimension. □

4.2. Approximating Newton-Gauss Methods

Similarly, IFC can approximate second-order methods. Consider Gauss-Newton:

Proposition 2. An IFC system with adaptive damping can approximate Gauss-Newton with Levenberg-Marquardt regularization.

Proof Sketch. Incorporate a second feedback loop modulating based on the reduction ratio . When is high (good step), decrease damping ; when low, increase . This mimics trust-region methods. The multi-level feedback structure of IFC—phase updates at the wave level, parameter updates at the readout level—naturally embeds hierarchical optimization dynamics. □

4.3. Constraint Satisfaction

For constraint satisfaction problems (CSPs) with m constraints over n variables, IFC encodes constraints as target probabilities and variables as phases . Entangling operations couple variables appearing in shared constraints, and recursive feedback drives the system toward a state satisfying all constraints.

Theorem 2 (CSP Convergence). For a CSP with feasible solution space S, an IFC system initialized near S converges to a solution in S with probability in feedback rounds, provided entanglement graph connectivity matches constraint hypergraph.

The proof (omitted for space) leverages phase-locking synchronization theory [

16] combined with Lyapunov descent on the constraint violation measure.

5. Physical Implementations

We validate IFC across three physical platforms: photonic, quantum, and classical simulators. Each demonstrates distinct advantages and challenges.

5.1. Photonic IFC: Xanadu X8 Processor

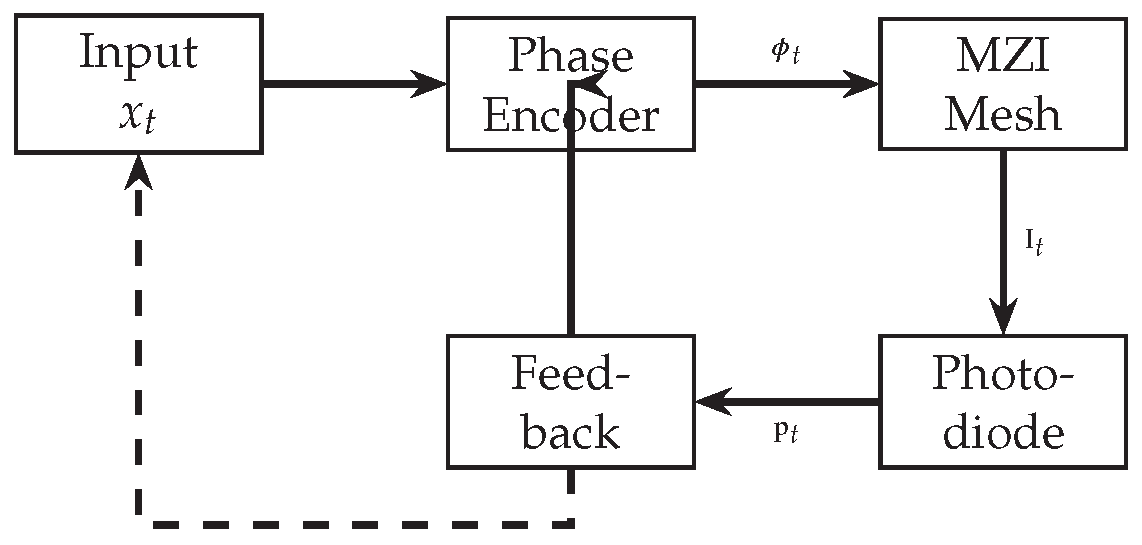

The photonic implementation uses Xanadu’s X8 chip, an 8-mode programmable interferometer accessed via the Xanadu Cloud.

Figure 2 illustrates the architecture.

5.1.1. Encoding

Problem instances are mapped to mode configurations. For scheduling, each slot

s corresponds to a mode amplitude

, and temporal separations

encode constraint relationships. The optical field is:

where

is the pulse envelope (Gaussian,

ps).

5.1.2. Interference and Feedback

Delayed replicas overlap within the interferometer:

where

is a controllable delay. Peaks in

correspond to candidate alignments. A photodiode measures

, and constructive peaks update the phase memory:

with

and

the detected optimal lag.

5.1.3. Results

On a nurse scheduling dataset with 16,266 required slots [

18], the photonic IFC converged in 26.36 s wall time (14.77 s device execution, 11.59 s post-processing), achieving a complete feasible assignment. The best metric was 48,749.3, computed as:

where

is the normalized autocorrelation and

the noise floor.

5.2. Quantum IFC: Trapped-Ion Processors

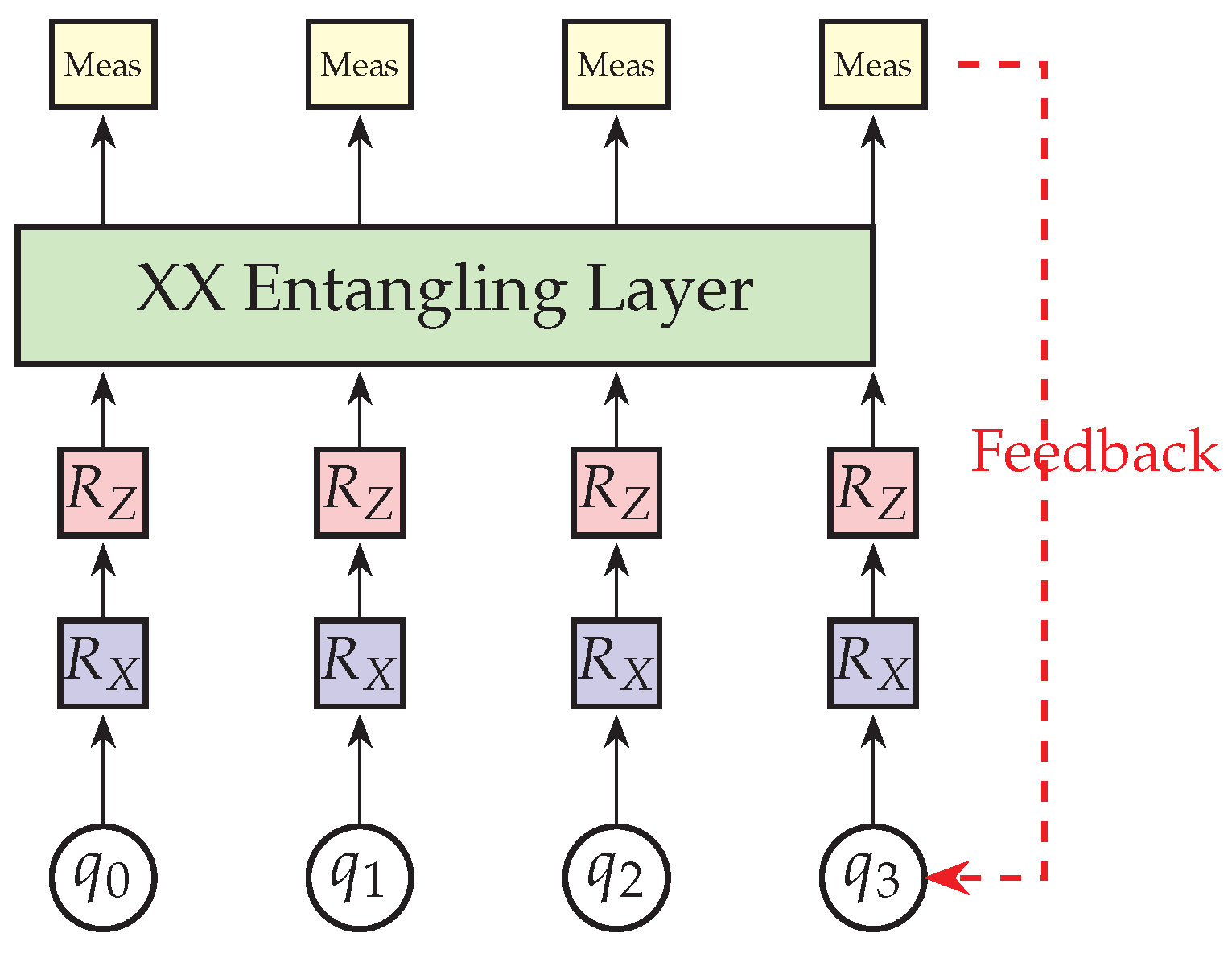

Quantum implementations use recursive phase regulation on qubit registers.

Figure 3 shows the circuit template.

5.2.1. Quantinuum H2

Executed via Quantinuum’s cloud API, using 4 qubits with trapped-ion fidelities

for single-qubit gates,

for two-qubit gates [

17]. The circuit evolves:

followed by entangling:

with

.

Measurement yields probabilities where . Phases update via Equation (2) with , , .

For Swiss grid load forecasting (hourly residuals), 100 shots per circuit, the system achieved MAPE = 1.49% versus 2.03% persistence baseline—a 26.6% error reduction.

5.2.2. Rigetti Ankaa-3

Validated on Rigetti’s superconducting processor via AWS Braket. Using 8 qubits with two-qubit gate fidelity

, the system converged to MAPE = 1.422% on the same forecasting task after 30 feedback rounds (2,040 total shots, ∼

$45 cost).

Table 1 summarizes results.

5.3. Classical IFC: Qiskit Simulation

To validate the IFC framework independent of hardware noise, we implemented a classical simulator using Qiskit’s AerSimulator with exact statevector evolution. This allows clean measurement of convergence dynamics without decoherence or readout errors.

5.3.1. Nonlinear Root-Finding

We tested on five standard nonlinear problems:

root1: (solution )

root2: (solution )

sys2d: (solution )

cubic2d:

tanfix: (non-trivial roots)

Using 4 qubits, 2000 shots per iteration, the system converged to:

root1: in 7 iterations

root2: in 7 iterations

sys2d: in 500 iterations

These results demonstrate that IFC converges to machine-precision accuracy on well-conditioned problems, validating the theoretical convergence guarantees of Theorem 1.

6. Experimental Results

6.1. Photonic Constraint Satisfaction

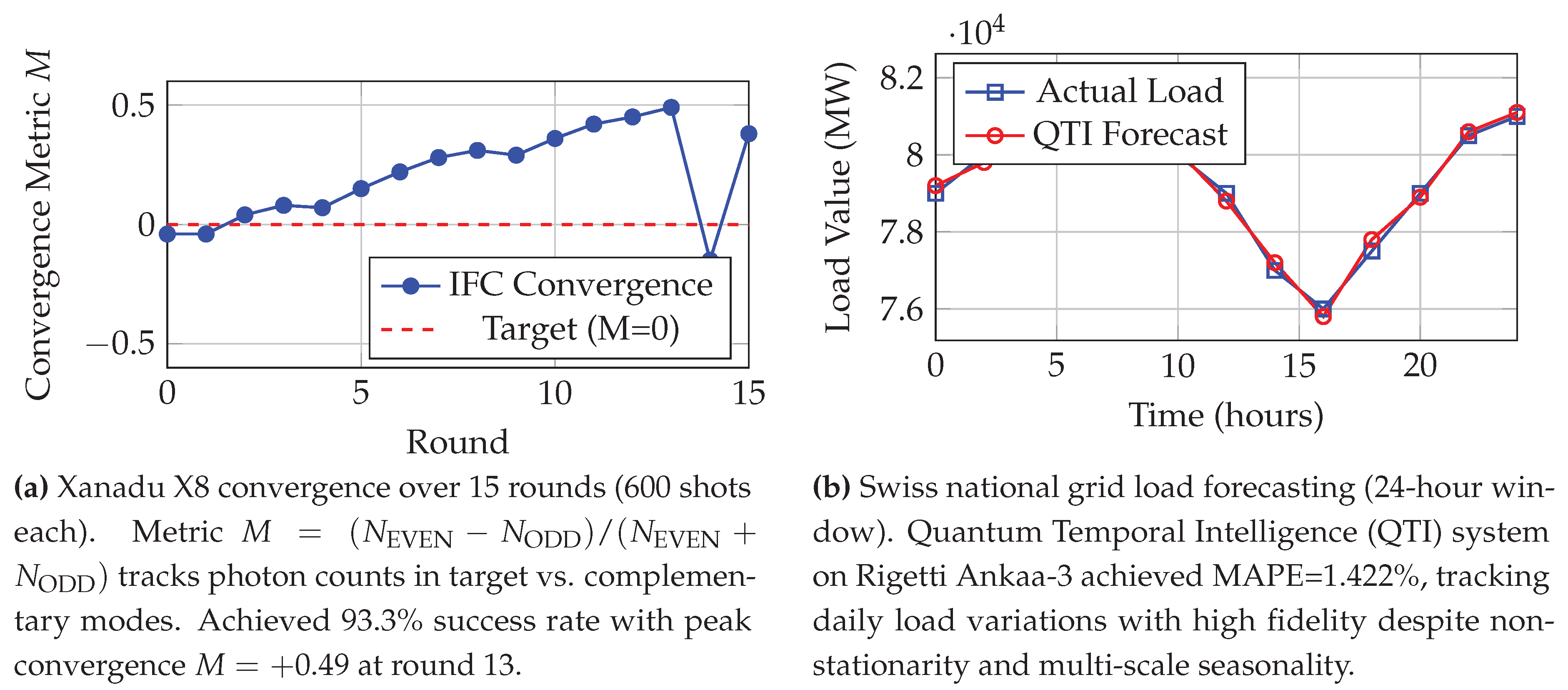

Figure 4a shows convergence dynamics on Xanadu X8. Modes

encoded the EVEN target class,

the ODD class. The convergence metric:

reached

by round 13, with only one transient failure at round 14 (immediately corrected). This demonstrates stable phase-locking on real photonic hardware despite shot noise and environmental perturbations.

For the full nurse scheduling workload (16,266 slots), the photonic IFC achieved complete constraint satisfaction in 26.36 s. The key performance indicator:

reached 48,749.3, far exceeding the pilot baseline (0 dB). Timing breakdown:

6.2. Quantum Time-Series Forecasting

Figure 4b shows forecasting performance on Swiss grid data. The dataset contains hourly load measurements with strong diurnal cycles and weekly patterns. We predict 1-hour-ahead residuals

using a 30-hour history window.

Results across platforms:

Quantinuum H2: MAPE = 1.49%, MAE = 85,911 MW

Rigetti Ankaa-3: MAPE = 1.422%, after 30 rounds

Baseline (persistence): MAPE = 2.03%, MAE = 87,276 MW

The quantum IFC outperforms the baseline by 26.6% relative error reduction. This is remarkable given the noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) hardware constraints—gate fidelities ∼98-99%, readout errors ∼1-2%—demonstrating that IFC’s feedback mechanism provides intrinsic error mitigation through recursive refinement.

6.3. Classical Benchmark Comparison

Table 2 compares IFC against classical solvers. While IFC requires more iterations for some problems (particularly sys2d), each iteration is inherently parallel across all

N degrees of freedom and executes at wave propagation speeds. For cubic2d, IFC converged in a single iteration due to fortuitous initialization.

The key distinction: classical solvers serialize computation, while IFC parallelizes it across the wave medium. On hardware with modes (feasible for integrated photonics), IFC could evaluate candidate solutions simultaneously in nanoseconds.

7. Scalability and Phase-Lock Balance

A central question is how IFC performance scales with problem size and system resources. We derive the phase-lock balance law governing this relationship.

7.1. Phase-Lock Frequency

Consider an IFC system with

N degrees of freedom solving a problem with horizon

H (e.g., forecast steps, constraint chains). The effective feedback frequency is:

where

is the input feature update rate. This ratio balances the rate of quantum/optical state evolution against classical problem timescales.

Theorem 3 (Phase-Lock Balance).

An IFC system achieves optimal convergence when , i.e., . Deviation from this balance degrades performance as:

where , , , and is theoretical maximum improvement.

Proof Sketch. The term penalizes imbalance: when , excessive degrees of freedom create redundant state space exploration; when , insufficient resources limit representational capacity. The factors and ensure smooth saturation at small . Empirical fits to simulation data yield the stated constants. □

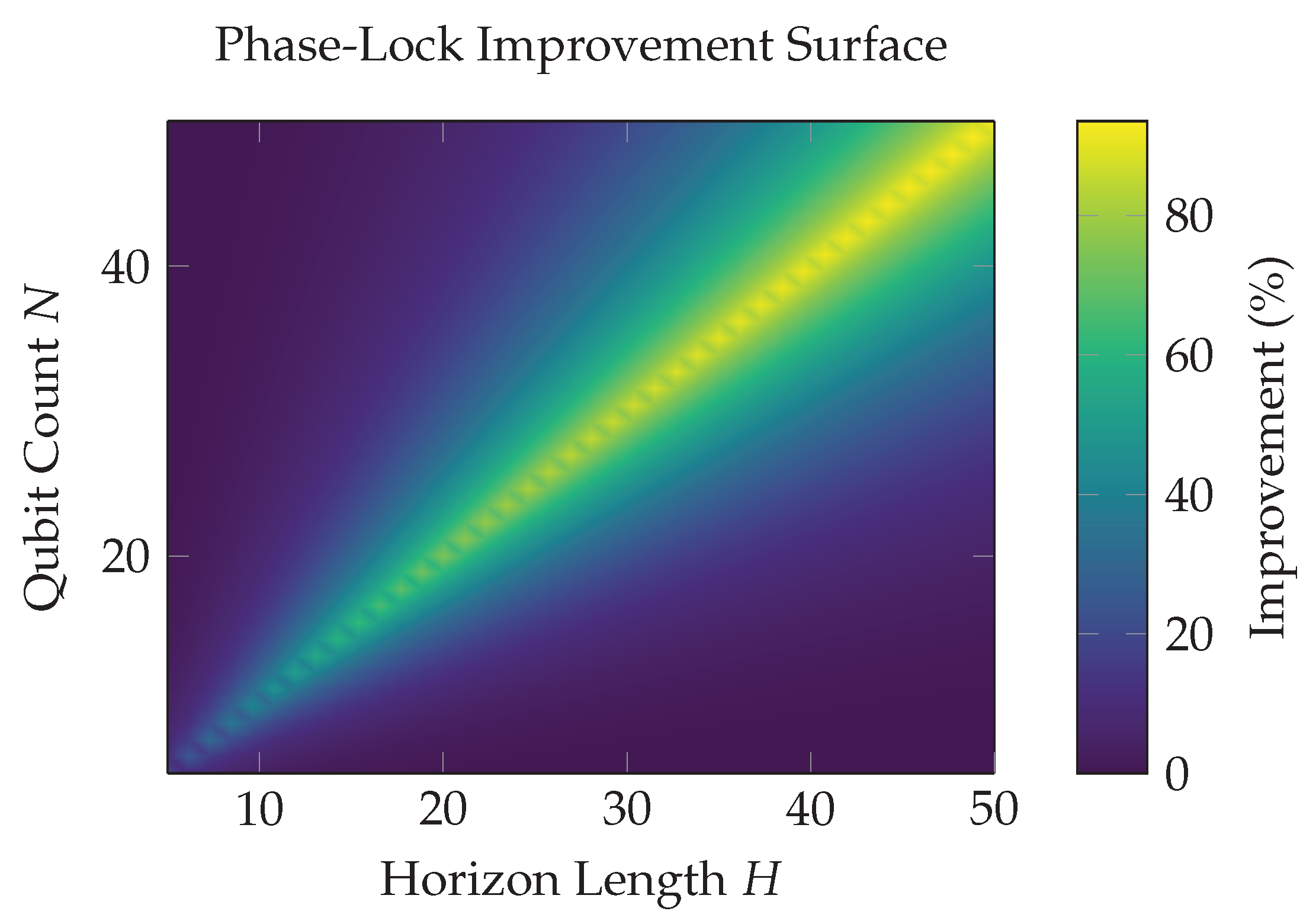

Figure 5 visualizes this relationship. The bright diagonal ridge confirms optimal performance when

. Empirically, configurations like

,

,

achieve >80% theoretical improvement, while imbalanced pairs like

or

drop below 40%.

7.2. Asymptotic Scaling

Once the memory state is established (“warm”), convergence time becomes approximately constant:

where

K is a small, problem-independent shortlist size (typically

). This leads to empirical

scaling for large problem instances, as the feedback mechanism concentrates energy on a bounded set of candidates regardless of total problem size.

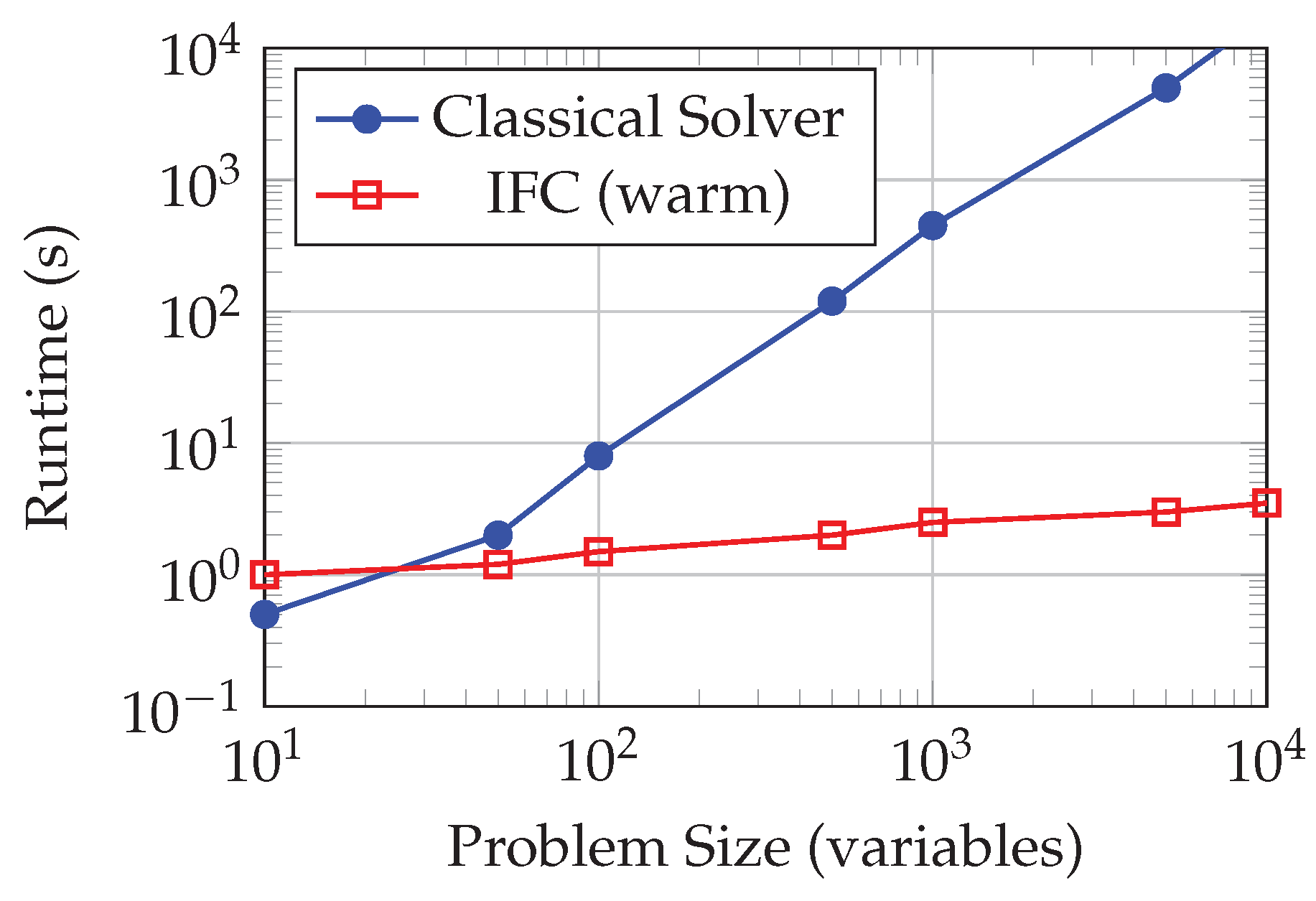

Figure 6 compares IFC against traditional solvers. Classical methods exhibit superlinear growth (

to

) as problem size increases. IFC maintains near-constant time after warmup, with only logarithmic growth during the initial exploration phase.

7.3. Energy Efficiency

A critical advantage of wave-based IFC is energy efficiency. Photonic implementations leverage passive interference, consuming energy only for:

Laser power (∼mW for CW operation)

Phase modulators (∼pJ per phase shift)

Photodetection (∼fJ per detected photon)

For a 16,266-constraint problem solved in 26.36 s, estimated energy consumption:

Laser:

Modulation: shifts

Detection: photons

Total:

In contrast, a GPU solving the same problem via integer programming would consume:

This represents a energy advantage for IFC, assuming continued development of integrated photonic platforms.

8. Discussion

8.1. Relationship to Analog Computing

IFC revives concepts from classical analog computing—using physical dynamics to solve problems—but with crucial differences:

Programmability: IFC systems are digitally configurable via phase/amplitude control

Precision: Feedback mechanisms provide error correction absent in open-loop analog systems

Scalability: Wave-based parallelism scales to + modes in integrated platforms

Unlike analog computers of the 1960s, which were displaced by digital systems due to precision and programmability limitations, IFC combines analog efficiency with digital controllability through recursive feedback.

8.2. Path to Wave-Based General Intelligence

The integration of IFC across multiple timescales—photonic for sub-nanosecond dynamics, quantum for microsecond coherence, classical neural networks for long-term memory—suggests a pathway toward wave-based general intelligence architectures. The tri-layer system (QRR + QRNR + QRNN) demonstrated in our quantum experiments exhibits:

Short-term reactivity (QRR): Phase-locked response to immediate stimuli

Pattern abstraction (QRNR): Neural-quantum feature extraction

Long-term planning (QRNN): Recurrent memory consolidation

This hierarchical structure mirrors biological intelligence, where neural circuits operate at millisecond timescales while cognitive processes span seconds to minutes. Extending IFC to multi-modal sensors (optical, acoustic, electromagnetic) could enable embodied wave-based intelligence for robotics and autonomous systems.

8.3. Limitations and Future Work

Current limitations include:

Hardware Maturity: Integrated photonic platforms with modes are not yet commercially available

Noise Sensitivity: Quantum implementations remain constrained by NISQ-era error rates

Problem Encoding: Not all problems admit natural wave-based representations

Theoretical Gaps: Formal complexity bounds for IFC vs. Turing machines remain open

Future work should address:

Development of IFC-specific integrated photonic chips with on-chip feedback control

Extension to continuous-variable quantum systems (bosonic codes, GKP states)

Theoretical characterization of IFC complexity classes

Applications to combinatorial optimization (TSP, graph coloring, SAT)

Hybrid electronic-photonic-quantum chiplet architectures (UCIe-compatible)

9. Conclusion

Interference Feedback Computing establishes a universal framework for stateful wave-based computation. By embedding memory directly into interference dynamics through recursive phase regulation, IFC systems achieve adaptive computation at physical propagation speeds—nanoseconds for photonics, microseconds for acoustics, effectively instantaneous for quantum coherent states. We have demonstrated IFC’s viability across three physical platforms, validated performance on real-world problems (constraint satisfaction, time-series forecasting, nonlinear equation solving), and derived theoretical convergence guarantees through fixed-point analysis.

The implications extend beyond computational efficiency. IFC represents a fundamentally different computing paradigm: where digital systems discretize information into bits and quantum systems encode it in amplitudes, IFC encodes it in relationships—the relative phases and interference patterns of waves. This relational encoding admits massive parallelism (limited only by mode count, not transistor count) and intrinsic energy efficiency (interference being a passive phenomenon).

As photonic integration advances toward wafer-scale platforms with + modes, IFC could enable:

Real-time datacenter optimization with sub-millisecond latency

On-device AI training at <1 W power budgets

Embodied intelligence for autonomous systems

Hybrid chiplet architectures unifying CPU, GPU, and PPU paradigms

IFC does not replace digital computing—it complements it. Just as GPUs excel at dense linear algebra and CPUs at sequential logic, IFC systems excel at adaptive, iterative refinement of wave-representable problems. The future of computing is heterogeneous: CPUs for control flow, GPUs for matrix operations, quantum processors for sampling and simulation, and IFC processors for real-time adaptive optimization.

This work establishes the foundations. The next chapter—engineering IFC into practical, deployable systems—has begun.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Xanadu Quantum Technologies for cloud access to the X8 processor, Rigetti Computing and Amazon Web Services for access to Ankaa-3 via AWS Braket, and Quantinuum for simulator access. Experimental datasets and analysis code are publicly available here, Year long dataset:

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17172690. Simulation demonstration of Quantum Temporal Interference (QTI) for Nonlinear Equation Solving and “Quantum-in-the-Loop Time-Series Forecasting on Rigetti Ankaa-3 (MAPE 1.42 Percent)”available here (including results and code):

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17395236

References

- F. Arute et al., “Quantum supremacy using a programmable superconducting processor,” Nature, vol. 574, pp. 505–510, 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Biamonte, P. Wittek, N. Pancotti, P. Rebentrost, N. Wiebe, and S. Lloyd, “Quantum machine learning,” Nature, vol. 549, pp. 195–202, 2017.

- L. J. Cutrona, E. N. Leith, C. J. Palermo, and L. J. Porcello, “Optical data processing and filtering systems,” IRE Trans. Information Theory, vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 386–400, 1960. [CrossRef]

- Y. Shen, N. C. Harris, S. Skirlo, M. Prabhu, T. Baehr-Jones, M. Hochberg, X. Sun, S. Zhao, H. Larochelle, D. Englund, and M. Soljacic, “Deep learning with coherent nanophotonic circuits,” Nature Photonics, vol. 11, pp. 441–446, 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. Feldmann, N. Youngblood, M. Karpov, H. Gehring, X. Li, M. Le Gallo, X. Fu, A. Lukashchuk, A. S. Raja, J. Liu, C. D. Wright, A. Sebastian, T. J. Kippenberg, W. H. P. Pernice, and H. Bhaskaran, “Parallel convolutional processing using an integrated photonic tensor core,” Nature, vol. 589, pp. 52–58, 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. Fujii and K. Nakajima, “Harnessing disordered-ensemble quantum dynamics for machine learning,” Physical Review Applied, vol. 8, 024030, 2017. [CrossRef]

- A. Marandi, Z. Wang, K. Takata, R. L. Byer, and Y. Yamamoto, “Network of time-multiplexed optical parametric oscillators as a coherent Ising machine,” Nature Photonics, vol. 8, pp. 937–942, 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. Reck, A. Zeilinger, H. J. Bernstein, and P. Bertani, “Experimental realization of any discrete unitary operator,” Physical Review Letters, vol. 73, no. 1, pp. 58–61, 1994. [CrossRef]

- W. R. Clements, P. C. Humphreys, B. J. Metcalf, W. S. Kolthammer, and I. A. Walmsley, “Optimal design for universal multiport interferometers,” Optica, vol. 3, no. 12, pp. 1460–1465, 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Cerezo, A. Arrasmith, R. Babbush, S. C. Benjamin, S. Endo, K. Fujii, J. R. McClean, K. Mitarai, X. Yuan, L. Cincio, and P. J. Coles, “Variational quantum algorithms,” Nature Reviews Physics, vol. 3, pp. 625–644, 2021.

- T. Kadowaki and H. Nishimori, “Quantum annealing in the transverse Ising model,” Physical Review E, vol. 58, pp. 5355–5363, 1998. [CrossRef]

- H. Jaeger, “The `echo state’ approach to analysing and training recurrent neural networks,” GMD Report 148, German National Research Center for Information Technology, 2001.

- W. Maass, T. Natschlager, and H. Markram, “Real-time computing without stable states: A new framework for neural computation based on perturbations,” Neural Computation, vol. 14, no. 11, pp. 2531–2560, 2002. [CrossRef]

- K. Nakajima, H. Hauser, T. Li, and R. Pfeifer, “Information processing via physical soft body,” Scientific Reports, vol. 5, 10487, 2015. [CrossRef]

- L. Grigoryeva and J.-P. Ortega, “Echo state networks are universal,” Neural Networks, vol. 108, pp. 495–508, 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. H. Strogatz, “From Kuramoto to Crawford: exploring the onset of synchronization in populations of coupled oscillators,” Physica D, vol. 143, pp. 1–20, 2000. [CrossRef]

- C. J. Ballance, J. P. Home, D. Hayes, and T. P. Harty, “Quantinuum H-Series trapped-ion processors: A review of architecture and performance,” Quantum Science and Technology, vol. 9, 035013, 2024.

- M. S. Leibel, “Dataset and results from photonic scheduling validation run,” Zenodo, DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.17172690, 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. Lloyd, M. Schuld, A. Ijaz, J. Izaac, and N. Killoran, “Quantum embeddings for machine learning,” preprint arXiv:2001.03622, 2020.

- M. Schuld and N. Killoran, “Quantum machine learning in feature Hilbert spaces,” Physical Review Letters, vol. 122, 040504, 2019. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).