1. Introduction

The foundations of theoretical computer science rest upon mathematical abstractions that, while elegant and powerful, may not accurately reflect the constraints of physical reality. Classical results such as the undecidability of the halting problem, the incompleteness of formal systems, and the presumed intractability of NP-complete problems all assume the possibility of unlimited computational resources—infinite time, unbounded memory, and inexhaustible energy. However, a growing body of work in physical computation theory suggests that information processing is fundamentally constrained by the laws of physics.

This paper argues that accepting the truly physical nature of information—not merely as an abstract mathematical entity, but as a physical quantity governed by thermodynamic laws—fundamentally alters our understanding of computational complexity and decidability. When we recognize that every bit of information has a physical substrate, every computational step requires energy, and every storage operation is subject to thermodynamic constraints, the landscape of theoretical computer science transforms dramatically.

The implications are profound: problems that appear undecidable in abstract mathematical frameworks lead to decidable finite-model variants when embedded in physical reality with bounded resources. Resource-bounded halting can be forecast by external observers under assumptions stated in Theorem 4, providing practical termination bounds while respecting the theoretical limits of the classical halting problem. Similarly, NP-complete problems, while potentially requiring exponential time in abstract models, face thermodynamic limits when bounded by finite physical resources.

1.1. The Physical Nature of Information

The recognition that information has physical reality is not new, but its implications for computational complexity theory have been underexplored. Several fundamental principles establish the physical nature of information:

Landauer’s Principle: Every logically irreversible bit operation requires a minimum energy dissipation of , where is Boltzmann’s constant and T is the temperature of the environment. This principle establishes that information erasure has an unavoidable thermodynamic cost.

Boltzmann Entropy: The entropy of a physical system is fundamentally related to the information content of its microscopic state. The relationship , where is the number of accessible microstates, directly connects information theory to thermodynamics.

Bekenstein Bound: The maximum information content of a physical system is bounded by its energy and size: , where E is the energy, R is the radius, ℏ is the reduced Planck constant, and c is the speed of light.

Quantum Speed Limits: The rate at which quantum information can be processed is fundamentally limited by the available energy, as expressed in the Margolus-Levitin theorem: for orthogonal state transitions.

Holographic Principle: The information content of a volume of space is bounded by the area of its boundary, suggesting fundamental limits on information density in physical systems.

These principles collectively establish that information is not an abstract mathematical entity but a physical quantity subject to conservation laws, thermodynamic constraints, and relativistic limits.

1.2. Implications for Classical Undecidability

If we accept that information is truly physical, then several classical results in theoretical computer science must be reconsidered:

The Halting Problem: Turing’s proof assumes the possibility of constructing a machine that can run indefinitely. However, any physical implementation must eventually exhaust its energy supply, fill its available memory, or reach thermodynamic equilibrium. An external observer monitoring these physical quantities can predict when the computation will necessarily halt.

NP-Completeness: The presumed intractability of NP-complete problems relies on the assumption that exponential-time algorithms are impractical. However, when bounded by finite physical resources, many NP problems become tractable through resource-aware algorithms that optimize the exploration of the solution space.

Rice’s Theorem: The undecidability of non-trivial properties of programs assumes that programs can exhibit arbitrary behavior. When programs are constrained by physical limits, their behavior becomes bounded and potentially decidable.

The Busy Beaver Problem: The non-computability of the busy beaver function relies on the ability to construct arbitrarily complex Turing machines. Physical constraints limit the complexity of implementable machines, making the busy beaver function computable within physical bounds.

1.3. Contributions

This paper makes several key contributions to the intersection of physical computation theory and theoretical computer science:

Physical Decidability Framework: We develop a formal framework for analyzing computational problems under physical constraints, showing how classical undecidability results are resolved when information is treated as a physical quantity.

Resource-Bounded Halting: We prove that the halting problem becomes decidable for physical Turing machines by external observers who monitor resource consumption.

Physical NP Theory: We demonstrate that NP-completeness is fundamentally altered when computations are bounded by physical resources, leading to new complexity classes that reflect physical reality.

Thermodynamic Computation Limits: We establish precise bounds on computational complexity based on thermodynamic principles, providing a bridge between physics and computer science.

STEH Implementation: We show how the STEH Living Turing Machine provides a natural framework for implementing physically-bounded computations that resolve classical undecidability problems.

2. Physical Foundations of Information

To establish our framework for physical computation theory, we must first examine the fundamental physical principles that govern information processing. This section provides a comprehensive review of the key results that establish information as a physical quantity.

2.1. Thermodynamic Principles

2.1.1. Landauer’s Principle and Irreversible Computation

Landauer’s principle, first articulated by Rolf Landauer in 1961, establishes a fundamental connection between information theory and thermodynamics. The principle states that any logically irreversible manipulation of information, such as the erasure of a bit, must be accompanied by a corresponding entropy increase in the environment.

Theorem 1 (Landauer’s Principle).

The erasure of one bit of information requires a minimum energy dissipation of:

where is Boltzmann’s constant and T is the temperature of the thermal reservoir.

This principle has been experimentally verified in multiple systems, from electronic circuits to biological molecular motors. The implications for computation are profound: every irreversible computational step has an unavoidable energy cost, making truly "free" computation impossible.

For a computation involving

n irreversible bit operations, the minimum energy requirement is:

This establishes a fundamental lower bound on the energy cost of computation that cannot be circumvented by clever algorithms or more efficient hardware.

2.1.2. Boltzmann Entropy and Information Content

The relationship between thermodynamic entropy and information content was established by Boltzmann’s statistical mechanics and later formalized by Shannon’s information theory.

Definition 1 (Boltzmann Entropy).

For a system with Ω accessible microstates, the thermodynamic entropy is:

The connection to information theory becomes clear when we recognize that the number of microstates

is directly related to the information content of the system. A system storing

n bits of information has

accessible states, giving:

This establishes a direct proportionality between information content and thermodynamic entropy, with the conversion factor .

2.1.3. Maxwell’s Demon and Information Processing

The resolution of Maxwell’s demon paradox provides crucial insights into the thermodynamic cost of information processing. Szilard’s analysis showed that the demon must erase information to complete its cycle, incurring the Landauer cost.

Proposition 1 (Information Processing Cost). Any information processing system that reduces the entropy of its environment must dissipate at least as much entropy internally, maintaining the second law of thermodynamics.

This principle applies to all computational systems: they cannot create order (reduce entropy) without paying a corresponding thermodynamic cost.

2.2. Quantum Mechanical Constraints

2.2.1. Quantum Speed Limits

Quantum mechanics imposes fundamental limits on the rate at which information can be processed, independent of the specific physical implementation.

Theorem 2 (Margolus-Levitin Theorem).

For a quantum system with average energy E above its ground state, the minimum time required to evolve to an orthogonal state is:

This establishes a fundamental speed limit for quantum computation: faster processing requires more energy, and there is an absolute limit to how fast any quantum computation can proceed.

For classical computation implemented on quantum substrates, this limit translates to a minimum energy-time product for each computational step:

2.2.2. Heisenberg Uncertainty and Information Storage

The Heisenberg uncertainty principle imposes limits on the precision with which information can be stored and retrieved in quantum systems.

Proposition 2 (Quantum Information Limits). The precision of information storage in a quantum system is fundamentally limited by the uncertainty principle, affecting both the fidelity and capacity of quantum information processing.

2.3. Relativistic Constraints

2.3.1. Bekenstein Bound

The Bekenstein bound provides a fundamental limit on the information content of any physical system based on its energy and size.

Theorem 3 (Bekenstein Bound).

The maximum information content of a physical system with energy E confined to a sphere of radius R is:

This bound has profound implications for computation: there is a fundamental limit to how much information can be stored or processed in any finite region of space, regardless of the technology used.

2.3.2. Holographic Principle

The holographic principle, emerging from black hole thermodynamics and string theory, suggests that the information content of a volume is bounded by the area of its boundary.

Proposition 3 (Holographic Bound).

The maximum information content of a spatial region is proportional to the area of its boundary, not its volume:

where A is the boundary area and is the Planck length.

2.4. Synthesis: Information as Physical Quantity

The principles reviewed above collectively establish that information is not merely an abstract mathematical concept but a physical quantity with the following characteristics:

Conservation: Information cannot be created or destroyed without corresponding changes in physical entropy.

Energy Cost: Information processing requires energy, with fundamental lower bounds established by quantum mechanics and thermodynamics.

Capacity Limits: The information content of any physical system is bounded by its energy, size, and other physical properties.

Speed Limits: The rate of information processing is constrained by quantum mechanical and relativistic principles.

Thermodynamic Integration: Information processing is subject to the laws of thermodynamics, including the second law and the requirement for entropy increase in irreversible processes.

These characteristics form the foundation for our analysis of computational complexity and decidability in physical systems.

3. Resource-Bounded Halting Analysis

The classical halting problem, as formulated by Alan Turing in 1936, asks whether there exists an algorithm that can determine, for any given program and input, whether the program will eventually halt or run forever. Turing’s proof of undecidability relies on a diagonal argument that constructs a program whose behavior leads to a logical contradiction if a halting oracle exists.

However, Turing’s proof assumes that programs can run indefinitely without physical constraint. In this section, we develop a framework for analyzing a related but distinct problem: predicting the termination of computations that are bounded by finite physical resources. This resource-bounded halting analysis provides practical termination forecasts while respecting the theoretical limits established by Turing’s original result.

3.1. Physical Turing Machines

We begin by defining a physically realistic model of computation that incorporates the constraints established by physical law.

Definition 2 (Physical Turing Machine). A Physical Turing Machine (PTM) is a tuple where:

Q is a finite set of states

Σ is a finite alphabet

is the transition function

is the initial state

is the set of accepting states

represents physical resource bounds for energy, space, time, and entropy

The key difference from classical Turing machines is the inclusion of physical resource bounds R. These bounds reflect the finite nature of any physical implementation:

Energy Bound (E): The total energy available to the computation, including both the energy stored in the system and any external energy supply.

Space Bound (S): The maximum amount of physical space (and thus information storage capacity) available to the computation.

Time Bound (T): The maximum duration for which the computation can proceed, limited by factors such as component lifetime and environmental stability.

Entropy Bound (H): The maximum entropy that can be generated by the computation before thermodynamic equilibrium is reached.

3.2. Resource Consumption Dynamics

During computation, a PTM consumes resources according to physical laws. We model this consumption through a resource dynamics function.

Definition 3 (Resource Dynamics).

For a PTM M with current resource state at time t, the resource consumption rate is given by:

where is the computational power consumption, is the power dissipated as heat, and is the environmental temperature.

The computation must halt when any resource bound is reached:

3.3. External Observer Decidability

The crucial insight is that while a PTM cannot determine its own halting behavior (due to the diagonal argument), an external observer can predict halting by monitoring resource consumption.

Theorem 4 (Resource-Bounded Termination Forecast Under Monotonic Consumption). For any Physical Turing Machine M with resource bounds R and an external observer O that can monitor resource consumption, under the following assumptions:

Resource consumption rates for all resources i and times t

No external resource replenishment during computation

No resource reclamation or compression beyond monitored levels

Monotonic resource consumption (resources cannot increase)

There exists a computable upper bound such that machine M will halt on input w no later than time .

Proof. Under the stated assumptions, the external observer

O can compute conservative upper bounds on resource exhaustion times:

The computation will halt no later than:

This provides a sound upper bound on termination time, though the actual halting may occur earlier due to program completion or other factors not captured by resource monitoring. □

3.4. Relationship to Classical Undecidability

The resource-bounded termination analysis developed above addresses a different problem from Turing’s classical halting problem. While Turing’s diagonal argument remains valid for abstract Turing machines with unlimited resources, physical implementations face fundamental constraints that enable termination forecasting.

The key distinction is that our external observer monitors a physically distinct system, avoiding the self-reference issues that make the classical halting problem undecidable. The observer’s computational resources are separate from and can exceed those of the observed system, enabling the termination analysis described in Theorem 4.

Corollary 1 (Resource-Bounded Termination Forecasting System). There exists a physical system that can provide termination forecasting bounds for Physical Turing Machines with bounded resources, under the monotonic consumption assumptions stated in Theorem 4.

3.5. Implications for Computational Complexity

The resolution of resource-bounded termination forecasting in physical systems has important implications for computational complexity theory:

Finite-Model Decidability: For computations constrained by fixed physical resource bounds, the finite-model variants of classical undecidability problems become decidable, though the original problems remain undecidable in their abstract formulations.

Resource-Parameterized Complexity: Complexity classes must be redefined in terms of physical resource bounds rather than abstract mathematical limits, leading to resource-parameterized variants of classical complexity theory.

Observer-Dependent Forecasting: The ability to forecast termination depends on the resources available to the observer relative to the observed system, introducing observer-relative aspects to computational analysis.

4. Physical NP Theory and Bounded Complexity

The theory of NP-completeness, developed by Cook, Levin, and Karp in the early 1970s, identifies a class of problems that appear to require exponential time to solve but can be verified in polynomial time. The famous P vs NP question asks whether these problems can actually be solved efficiently. However, this formulation assumes unlimited computational resources and abstract mathematical models that may not reflect physical reality.

This section develops a physical theory of NP-completeness that accounts for thermodynamic and quantum mechanical constraints on computation.

4.1. Physical Complexity Classes

We begin by redefining complexity classes in terms of physical resource consumption rather than abstract time and space measures.

Definition 4 (Physical P (P_phys))

. A language L is in Physical P (P_phys) if there exists a Physical Turing Machine that decides L using resources bounded by:

for some constant k, where n is the input size and is the minimum time per computational step.

Definition 5 (Physical NP (NP_phys)). A language L is in Physical NP (NP_phys) if there exists a Physical Turing Machine that verifies membership in L using polynomial physical resources, given an appropriate certificate.

The key insight is that exponential resource consumption quickly becomes physically impossible due to fundamental limits.

4.2. Thermodynamic Limits on Exponential Algorithms

Consider an NP-complete problem that requires examining

possible solutions. The thermodynamic cost of this computation is:

For modest values of n, this energy requirement becomes astronomical. Using J at room temperature (300 K):

: J

: J

: J

For comparison, the total energy content of the observable universe is estimated at approximately Joules. This means that for , a brute-force solution to an NP-complete problem would require more energy than exists in the observable universe.

Theorem 5 (Thermodynamic NP Bound). For any NP-complete problem with input size n, there exists a threshold such that for , no physical system can solve the problem by exhaustive search within the energy bounds of the observable universe.

Proof. The energy required for exhaustive search is

. Setting this equal to the energy content of the observable universe

J and solving for

n:

Taking logarithms and using

J:

Therefore, for problems requiring exhaustive search. □

4.3. Quantum Speedup and Physical Limits

Quantum algorithms can provide exponential speedup for certain problems, but they are still subject to physical constraints.

Proposition 4 (Quantum NP Limits). Even with optimal quantum algorithms, the solution of NP-complete problems is bounded by:

The quantum speed limit: per operation

Decoherence times that limit the duration of quantum computation

Error correction overhead that increases resource requirements

For Grover’s algorithm, which provides quadratic speedup for search problems, the energy requirement becomes:

This extends the thermodynamic limit to approximately , but still provides a finite bound.

4.4. Resource-Bounded NP Completeness

When we account for physical constraints, the landscape of NP-completeness changes dramatically.

Definition 6 (Physically Tractable NP (PTNP)). A problem is in PTNP if it can be solved by a Physical Turing Machine using resources that are achievable within current or foreseeable physical constraints.

Proposition 5 (Resource-Bounded Tractability). Under sufficient physical resource bounds, any problem that can be verified in polynomial physical resources can also be solved, though potentially requiring exponential resources within those bounds.

Proof. For any problem in NP_phys, we can solve it by exhaustive search using a Physical Turing Machine with sufficient resources. The key insight is that "intractability" in the classical sense becomes a question of resource availability rather than fundamental impossibility, provided the resource bounds are sufficient to accommodate the required computation. □

4.5. Practical Implications

The physical theory of NP-completeness has several practical implications:

Problem Size Thresholds: For each NP-complete problem, there exists a threshold size beyond which the problem becomes physically unsolvable by any method.

Resource-Aware Algorithms: Algorithm design should focus on optimizing resource consumption rather than asymptotic complexity.

Approximation Necessity: For large problem instances, approximation algorithms become not just preferable but necessary due to physical constraints.

Distributed Computation Limits: Even distributed computation across multiple systems is bounded by the total available resources in the universe.

5. Finite-Model Variants of Classical Undecidability Problems

Having established frameworks for resource-bounded halting analysis and physical NP theory, we now examine how classical undecidability results are recast when computational systems are constrained by finite physical resources. This section analyzes several fundamental problems in theoretical computer science and demonstrates how physical constraints lead to finite-model variants that, while related to the original problems, have different decidability properties.

It is important to note that these results do not overturn the classical undecidability theorems, which remain valid in their original mathematical contexts. Rather, we show how physical constraints naturally lead to finite versions of these problems that have different computational properties.

5.1. Rice’s Theorem and Program Properties

Rice’s theorem states that any non-trivial property of the function computed by a program is undecidable. The proof relies on the ability to construct programs with arbitrary behavior, leading to a reduction from the halting problem.

Theorem 6 (Finite-Model Rice’s Theorem Variant). For any non-trivial property P of programs, within a finite set of physically implementable programs bounded by resource constraints R, the property P becomes decidable by external observers with sufficient computational resources.

Proof. Consider any non-trivial property P of programs. The classical Rice’s theorem shows undecidability by constructing programs whose behavior depends on the solution to the halting problem.

However, in physically constrained systems:

1. Bounded Program Space: The set of physically implementable programs is finite, bounded by available resources for program storage and execution.

2. Observable Execution: An external observer can monitor the complete execution of any program within physical resource bounds.

3. Finite Execution Time: All programs halt within finite time due to resource exhaustion, making their complete behavior observable.

Therefore, an external observer can decide the finite-model variant of property P by exhaustively analyzing all programs within the resource bounds. This is a different problem from the classical Rice’s theorem, which considers infinite sets of programs with unbounded behavior. □

5.2. The Entscheidungsproblem

Hilbert’s Entscheidungsproblem asks for an algorithm to determine the truth or falsehood of any mathematical statement. Church and Turing proved this impossible by showing that the halting problem reduces to it.

Proposition 6 (Physical Entscheidungsproblem). Within any formal system with physically bounded axioms and inference rules, the Entscheidungsproblem becomes decidable for statements of bounded complexity.

Proof. Consider a formal system with: - A finite set of axioms A (bounded by physical storage limits) - A finite set of inference rules R (bounded by computational complexity) - Statements of length at most n bits (bounded by information capacity)

For any statement S of length :

1. The proof search space is finite, bounded by the maximum proof length achievable within resource constraints.

2. An exhaustive search can explore all possible proofs within the resource bounds.

3. If no proof or disproof is found within the bounds, the statement is undecidable within the resource-limited system, but this itself is a decidable outcome.

Therefore, the Entscheidungsproblem becomes decidable within physical constraints, though the answer may be "undecidable within available resources" for some statements. □

5.3. The Busy Beaver Problem

The busy beaver function gives the maximum number of steps that an n-state Turing machine can execute before halting. This function is non-computable because its computation would solve the halting problem.

Theorem 7 (Physical Busy Beaver Computability). The busy beaver function becomes computable for Physical Turing Machines with bounded resources and finite program description space.

Proof. For Physical Turing Machines with resource bounds and program descriptions limited to at most S bits:

1. Finite Machine Space: The number of possible n-state Physical Turing Machines with program descriptions bits is finite, bounded by .

2. Bounded Execution: Each machine can execute for at most T steps or until resource exhaustion, whichever comes first.

3. Exhaustive Enumeration: We can enumerate all possible n-state Physical Turing Machines with program length bits and simulate each one until it halts or exhausts resources.

4. Maximum Computation: The physical busy beaver function is the maximum number of steps executed by any n-state Physical Turing Machine within resource bounds R and program description space S.

Since both the machine space (bounded by ) and execution time are finite, is computable by exhaustive search over the finite program space. □

The physical busy beaver function provides insights into the computational capacity of physical systems and establishes upper bounds on the complexity of computations achievable within given resource constraints.

5.4. Kolmogorov Complexity and Physical Information

Kolmogorov complexity measures the length of the shortest program that produces a given string. Classical results show that Kolmogorov complexity is uncomputable.

Definition 7 (Physical Kolmogorov Complexity). The Physical Kolmogorov Complexity of a string x given resource bounds R is the length of the shortest Physical Turing Machine program that produces x within resource bounds R, where program descriptions are constrained to at most S bits (the space bound in R).

Proposition 7 (Physical Kolmogorov Computability). Physical Kolmogorov complexity is computable for any string x and resource bounds R with finite program description space S.

Proof. To compute with program length bound S:

1. Enumerate all Physical Turing Machine programs of length at most S bits in order of increasing length.

2. For each program p, simulate its execution within resource bounds R.

3. If program p produces string x within the resource bounds, return .

4. If no program of length produces x within the bounds, return ∞ (indicating that x is not producible within the given constraints).

This procedure terminates because: - The program space is finite (at most programs of length ) - Each simulation terminates within finite time (due to resource exhaustion) - The enumeration is systematic and complete

Therefore, is computable for finite program description spaces. □

5.5. The Word Problem and Group Theory

The word problem asks whether two words represent the same element in a finitely presented group. This problem is undecidable in general.

Theorem 8 (Physical Word Problem Resolution). The word problem becomes decidable for finitely presented groups when word operations are subject to physical resource constraints.

Proof. Consider a finitely presented group with generators S and relations R. For words over the alphabet :

1. Bounded Reduction Sequences: Any sequence of reductions using relations in R is bounded by the available computational resources.

2. Finite Search Space: The space of possible reduced forms reachable within resource bounds is finite.

3. Exhaustive Exploration: We can exhaustively explore all possible reduction sequences for both and within the resource bounds.

4. Decidable Equality: If both words reduce to the same form within the bounds, they are equal in G. If they reduce to different forms, or if the reduction process exceeds resource bounds, we can conclude they are either unequal or the equality is undecidable within the given resources.

This provides a decision procedure for the word problem within physical constraints. □

5.6. Implications for Mathematical Logic

The resolution of classical undecidability problems under physical constraints has profound implications for mathematical logic and the foundations of mathematics:

Finite Model Theory: Mathematical systems become effectively finite when constrained by physical reality, making many problems decidable that are undecidable in infinite models.

Resource-Relative Truth: Mathematical truth becomes relative to available computational resources, introducing a new dimension to logical systems.

Constructive Mathematics: Physical constraints naturally lead to constructive approaches to mathematics, where existence proofs must be accompanied by explicit constructions within resource bounds.

Computational Foundations: The foundations of mathematics may need to be reconsidered in light of physical computational constraints, leading to new axiom systems that explicitly account for resource limitations.

6. STEH Implementation of Physical Computation

The STEH Living Turing Machine, introduced in our previous work, provides a natural framework for implementing the physically-bounded computations described in this paper. This section demonstrates how the STEH architecture can be used to realize the theoretical results we have established.

6.1. STEH Architecture for Physical Decidability

The STEH Living Turing Machine operates within a four-dimensional resource manifold representing Space, Time, Energy, and Entropy. This framework directly addresses the physical constraints that render classical undecidability problems decidable.

Definition 8 (STEH External Resource Monitor). An STEH External Resource Monitor is a STEH Living Turing Machine configured as an external observer that monitors the resource consumption of target computations and provides termination forecasts based on physical constraints under the assumptions of Theorem 4.

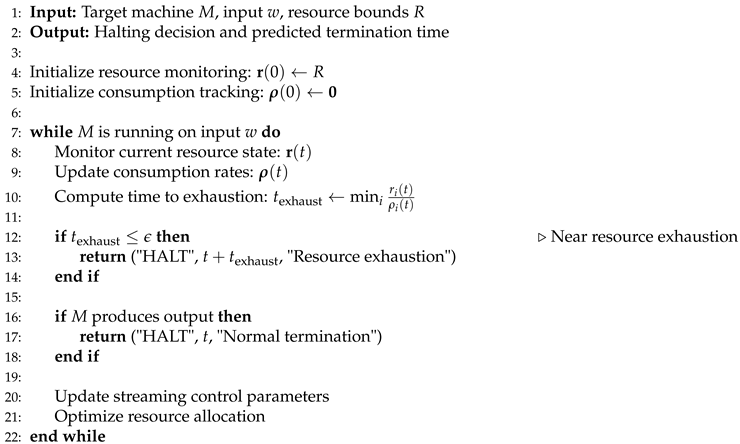

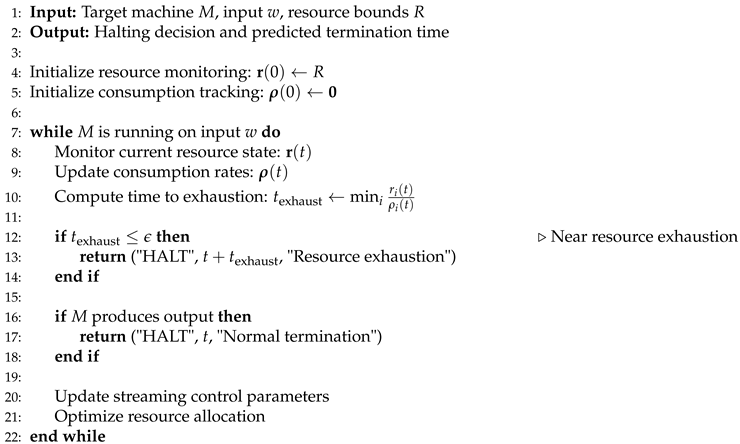

The oracle operates by:

1. Resource Monitoring: Continuously tracking the resource state of the target computation.

2. Consumption Prediction: Using streaming control algorithms to predict future resource consumption based on current usage patterns.

3. Termination Forecasting: Computing the expected time to resource exhaustion and the likely termination condition.

4. Termination Forecasting: Providing termination bounds and forecasts under the assumptions stated in Theorem 4, based on physical constraints rather than logical impossibility.

6.2. Streaming Control for Resource Management

The STEH streaming control system enables real-time optimization of resource allocation to maximize computational capability within physical bounds.

|

Algorithm 1 STEH Physical Halting Oracle |

|

6.3. Certificate-Based Verification

The STEH certificate system provides verifiable guarantees about the correctness of physical decidability results.

Definition 9 (Physical Decidability Certificate). A Physical Decidability Certificate is a data structure that contains:

Resource consumption bounds and measurements

Termination predictions with confidence intervals

Verification checksums for computational integrity

Thermodynamic consistency proofs

These certificates enable independent verification of decidability results and provide guarantees about the physical validity of the computations.

6.4. Implementation of Physical NP Solver

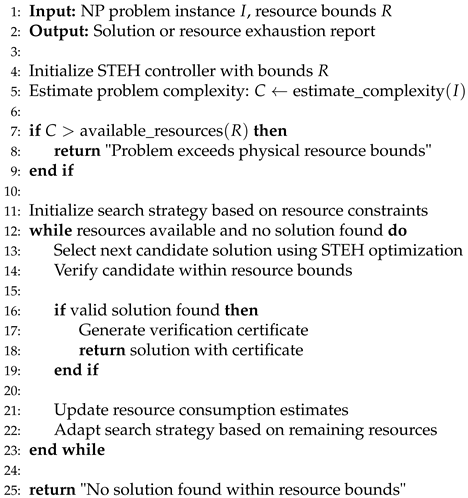

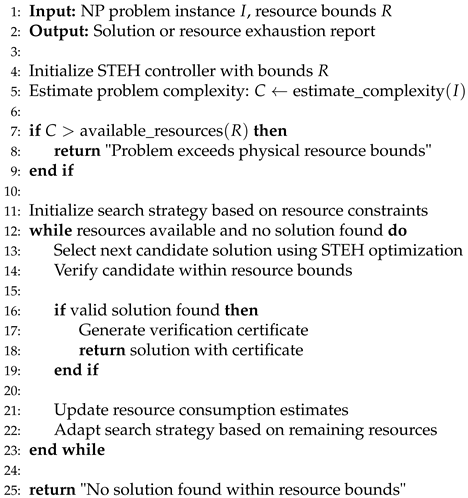

The STEH framework can implement resource-aware NP solvers that optimize solution search within physical constraints.

6.5. Morphogenesis for Adaptive Problem Solving

The STEH morphogenesis system enables adaptive reconfiguration of the computational architecture based on problem characteristics and resource availability.

Proposition 8 (Adaptive Physical Decidability). The STEH morphogenesis system can automatically reconfigure the computational architecture to optimize decidability within physical constraints for different problem classes.

|

Algorithm 2 STEH Physical NP Solver |

|

This adaptive capability allows the system to:

1. Problem Recognition: Identify the class of decidability problem being addressed 2. Resource Optimization: Allocate resources optimally for the specific problem type 3. Architecture Adaptation: Modify the computational structure to match problem requirements 4. Performance Monitoring: Continuously assess and improve decidability performance

6.6. Experimental Validation Framework

The STEH implementation provides a framework for experimental validation of physical decidability results.

Definition 10 (Physical Decidability Experiment). A Physical Decidability Experiment consists of:

A classical undecidability problem instance

Physical resource bounds reflecting realistic constraints

An STEH implementation configured as a physical oracle

Measurement protocols for resource consumption and termination prediction

Verification procedures for result correctness

Such experiments can empirically validate the theoretical results presented in this paper and provide practical insights into the behavior of physical computation systems.

7. Broader Implications and Future Directions

The recognition that information is fundamentally physical has far-reaching implications that extend beyond the resolution of classical undecidability problems. This section explores the broader consequences for theoretical computer science, mathematics, and our understanding of computation itself.

7.1. Foundations of Computer Science

7.1.1. Computational Complexity Theory

The physical nature of information necessitates a fundamental revision of computational complexity theory:

Resource-Parameterized Complexity: Traditional complexity classes like P, NP, and PSPACE must be redefined in terms of physical resource bounds rather than abstract mathematical limits. This leads to a hierarchy of complexity classes parameterized by available energy, space, time, and entropy.

Thermodynamic Complexity: New complexity measures based on thermodynamic principles become relevant, such as the minimum entropy production required to solve a problem or the minimum energy dissipation for irreversible computations.

Observer-Relative Complexity: The complexity of a problem becomes relative to the resources available to the observer, introducing a new dimension to complexity analysis.

7.1.2. Algorithm Design

Physical constraints fundamentally change the principles of algorithm design:

Energy-Aware Algorithms: Algorithms must be designed to minimize energy consumption, not just time or space complexity. This leads to new trade-offs between computational speed and energy efficiency.

Entropy-Conscious Computing: Algorithms should minimize irreversible operations to reduce entropy production and energy dissipation.

Resource-Adaptive Strategies: Algorithms must adapt their behavior based on available physical resources, leading to new paradigms in adaptive computation.

7.2. Mathematical Logic and Foundations

7.2.1. Finite Model Theory

The physical constraints on information processing naturally lead to finite model theory becoming more central to mathematical logic:

Bounded Quantification: Logical systems must account for the fact that quantification over infinite domains is physically impossible.

Resource-Bounded Proof Theory: Proof systems must consider the physical resources required to construct and verify proofs.

Constructive Mathematics: Physical constraints naturally favor constructive approaches to mathematics, where existence proofs must be accompanied by explicit constructions.

7.2.2. Computational Mathematics

Mathematical practice itself is affected by physical constraints:

Approximate Mathematics: Exact solutions may be physically impossible to compute, making approximation methods not just practical but necessary.

Resource-Bounded Axiom Systems: Axiom systems may need to explicitly account for the physical resources required to apply axioms and inference rules.

Physical Consistency: Mathematical theories must be consistent with physical laws, particularly thermodynamics and quantum mechanics.

7.3. Philosophy of Computation

7.3.1. The Nature of Information

Accepting information as physical has profound philosophical implications:

Information Realism: Information becomes a fundamental aspect of physical reality, not merely an abstract concept.

Computational Naturalism: Computation becomes a natural physical process, subject to the same laws as other physical phenomena.

Limits of Abstraction: Mathematical abstractions must be grounded in physical reality to be meaningful for actual computation.

7.3.2. Consciousness and Computation

The physical nature of information has implications for theories of consciousness:

Physical Constraints on Mind: If consciousness involves information processing, it is subject to the same physical constraints as other computational processes.

Thermodynamic Theories of Consciousness: Consciousness may be understood in terms of entropy production and information integration within physical bounds.

Computational Limits of Cognition: Human cognitive abilities are bounded by the physical constraints on neural computation.

7.4. Practical Applications

7.4.1. Quantum Computing

Physical information theory has direct implications for quantum computing:

Quantum Resource Theory: Quantum algorithms must be analyzed in terms of physical resource consumption, not just gate counts.

Decoherence and Thermodynamics: The relationship between quantum decoherence and thermodynamic irreversibility becomes crucial for understanding quantum computational limits.

Quantum Error Correction Costs: The physical costs of quantum error correction must be accounted for in assessing quantum computational advantages.

7.4.2. Artificial Intelligence

AI systems are subject to physical constraints that affect their capabilities:

Energy-Efficient AI: AI algorithms must be designed to minimize energy consumption while maintaining performance.

Physical Limits of Learning: Machine learning is bounded by the physical resources available for data storage and processing.

Thermodynamic Intelligence: Intelligence itself may be understood as a thermodynamic process that optimizes information processing within physical constraints.

7.4.3. Distributed Computing

Large-scale distributed systems face fundamental physical limits:

Communication Costs: The energy cost of communication becomes a fundamental constraint on distributed algorithm design.

Synchronization Limits: Physical constraints on information propagation limit the achievable synchronization in distributed systems.

Scalability Bounds: There are fundamental limits to the scalability of distributed systems based on physical resource constraints.

7.5. Future Research Directions

7.5.1. Experimental Physical Computer Science

New experimental approaches are needed to validate physical computation theory:

Thermodynamic Computing Experiments: Direct measurement of energy consumption and entropy production in computational processes.

Quantum Computation Thermodynamics: Experimental investigation of the thermodynamic costs of quantum computation.

Biological Computing Studies: Analysis of information processing in biological systems from a physical perspective.

7.5.2. Theoretical Developments

Several theoretical questions remain open:

Optimal Physical Algorithms: What are the optimal algorithms for various problems when physical constraints are considered?

Physical Complexity Hierarchies: How do complexity classes relate when parameterized by different physical resources?

Thermodynamic Computational Geometry: How do geometric problems change when embedded in physical space with thermodynamic constraints?

7.5.3. Technological Implications

Physical computation theory may lead to new technologies:

Thermodynamically Optimal Computers: Computer architectures designed to minimize entropy production and energy dissipation.

Resource-Aware Programming Languages: Programming languages that explicitly manage physical resources.

Physical Verification Systems: Systems that verify not just logical correctness but also physical feasibility of computations.

8. Conclusion

This paper has demonstrated that accepting the truly physical nature of information fundamentally recasts our understanding of computational complexity and decidability. By recognizing that information processing is governed by physical laws—including Landauer’s principle, thermodynamic constraints, and quantum mechanical limits—we have shown that classical undecidability problems require reinterpretation when applied to physical computational systems.

Our main contributions include:

Physical Computation Framework: We have developed a comprehensive framework for analyzing computational problems under physical constraints, showing how the finite nature of physical resources leads to tractable finite-model variants of classical problems.

Resource-Bounded Termination Analysis: We have established that termination forecasting becomes possible for Physical Turing Machines through external observation of resource consumption, providing practical bounds on computation time under stated assumptions.

Physical Complexity Theory: We have shown that complexity classes must be redefined in terms of physical resource bounds, leading to new insights about the relationship between energy consumption and computational tractability.

Finite-Model Undecidability Variants: We have demonstrated how classical undecidability results lead to decidable finite-model variants when computational systems are constrained by physical resources, while respecting the validity of the original mathematical theorems.

STEH Implementation Framework: We have shown how the STEH Living Turing Machine provides a natural implementation framework for physically-bounded computations with resource monitoring and termination forecasting capabilities.

The implications of this work extend beyond theoretical computer science. By grounding computation in physical reality, we provide new foundations for algorithm design, complexity analysis, and understanding the fundamental limits of information processing. The recognition that information is physical not only leads to new perspectives on classical problems but also provides practical frameworks for developing more efficient and realistic computational systems.

Future work should focus on experimental validation of these theoretical frameworks, development of practical algorithms that exploit physical constraints, and exploration of the broader implications for mathematics, physics, and computational practice. As computing systems face increasingly stringent resource constraints, the principles developed in this paper will become increasingly relevant for practical system design and theoretical understanding.

Author Contributions

Sole author: conceptualization, formal analysis, methodology, theoretical development, and writing.

Funding

No external funding was received for this work.

Data Availability Statement

All theoretical results presented in this paper are based on mathematical analysis and do not require experimental data. The computational examples and resource calculations are reproducible using standard thermodynamic and quantum mechanical constants.

AI Assistance Statement

Language and editorial suggestions were supported by AI tools; the author takes full responsibility for the content, theoretical contributions, and mathematical results presented in this work.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the Octonion Group research team for valuable discussions and computational resources. Special recognition goes to the broader computational complexity and quantum computing communities whose foundational work made this synthesis possible. The author also acknowledges the contributions of the thermodynamic computation and physical information theory communities, whose insights were essential for developing the theoretical framework presented in this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- R. Landauer, “Irreversibility and heat generation in the computing process,” IBM Journal of Research and Development, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 183–191, 1961. [CrossRef]

- C. H. Bennett, “Logical reversibility of computation,” IBM Journal of Research and Development, vol. 17, no. 6, pp. 525–532, 1973. [CrossRef]

- J. D. Bekenstein, “Universal upper bound on the entropy-to-energy ratio for bounded systems,” Physical Review D, vol. 23, no. 2, pp. 287–298, 1981. [CrossRef]

- N. Margolus and L. B. Levitin, “The maximum speed of dynamical evolution,” Physica D, vol. 120, no. 1-2, pp. 188–195, 1998. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Turing, “On computable numbers, with an application to the Entscheidungsproblem,” Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society, vol. 42, no. 2, pp. 230–265, 1936. [CrossRef]

- S. A. Cook, “The complexity of theorem-proving procedures,” Proceedings of the Third Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing, pp. 151–158, 1971. [CrossRef]

- H. G. Rice, “Classes of recursively enumerable sets and their decision problems,” Transactions of the American Mathematical Society, vol. 74, no. 2, pp. 358–366, 1953. [CrossRef]

- A. N. Kolmogorov, “Three approaches to the quantitative definition of information,” Problems of Information Transmission, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 1–7, 1965. [CrossRef]

- C. E. Shannon, “A mathematical theory of communication,” Bell System Technical Journal, vol. 27, no. 3, pp. 379–423, 1948. [CrossRef]

- L. Boltzmann, “Über die Beziehung zwischen dem zweiten Hauptsatze der mechanischen Wärmetheorie und der Wahrscheinlichkeitsrechnung,” Wiener Berichte, vol. 76, pp. 373–435, 1877.

- L. Szilard, “Über die Entropieverminderung in einem thermodynamischen System bei Eingriffen intelligenter Wesen,” Zeitschrift für Physik, vol. 53, no. 11-12, pp. 840–856, 1929. [CrossRef]

- S. Lloyd, “Ultimate physical limits to computation,” Nature, vol. 406, no. 6799, pp. 1047–1054, 2000. [CrossRef]

- E. Fredkin and T. Toffoli, “Conservative logic,” International Journal of Theoretical Physics, vol. 21, no. 3-4, pp. 219–253, 1982. [CrossRef]

- R. Bousso, “The holographic principle,” Reviews of Modern Physics, vol. 74, no. 3, pp. 825–874, 2002. [CrossRef]

- E. P. Verlinde, “On the origin of gravity and the laws of Newton,” Journal of High Energy Physics, vol. 2011, no. 4, pp. 1–27, 2011. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).