1. Introduction

Quantum mechanics, since its inception, is well-known to have relied on mathematical tools involving infinite precision, such as real and complex numbers, and probabilistic interpretations that defy deterministic logic. Yet all physical measurements are well-known to be finite, and all digital computations—classical or quantum—must operate within rational and finite constraints as also well-known. This proposal sets a fundamental shift: to reformulate quantum mechanics using only computable constructs such as rational numbers, finite fields, deterministic logic, and algebra.

The case is made stronger by emerging applications in quantum computing and cryptography, which demand exactitude. For example, RSA encryption depends on exact prime factorization over integers as well-known, not approximations over so-called real-numbers. Similarly, measurement in any laboratory or quantum device yield rational outputs. If quantum computation is to become a practical and verifiable science, it must abandon reliance on the continuum and adopt a discrete, computable basis.

We demonstrate this approach in two ways: the well-known eigenvalue formulation of the Schrödinger equation providing deterministic results, which we solve using continued fractions, and through the rational reformulation as an improvement of Shor's algorithm (ISA) for factoring large integers. This serves not only as a proof of concept but as arguments for the full replacement of irrational and probabilistic artificial constructs in quantum mechanics.

This work argues that physical reality is fundamentally discrete with +12 dimensions, and best described through rational and integer-based structures. Irrational and imaginary numbers, though useful in mathematical abstractions, lack empirical support and misalign with physical reality in several noted instances. All historical, numerical, and computational evidence, including AI, support this paradigm shift from continuous abstractions to discrete foundations.

1.1. Key Claim

Physical and mathematical theories reliant on R/C are misaligned with nature’s structure, which is discrete.

1.2. Ontology

Imaginary and irrational numbers are representational tools—not ontological entities.

2. Framework

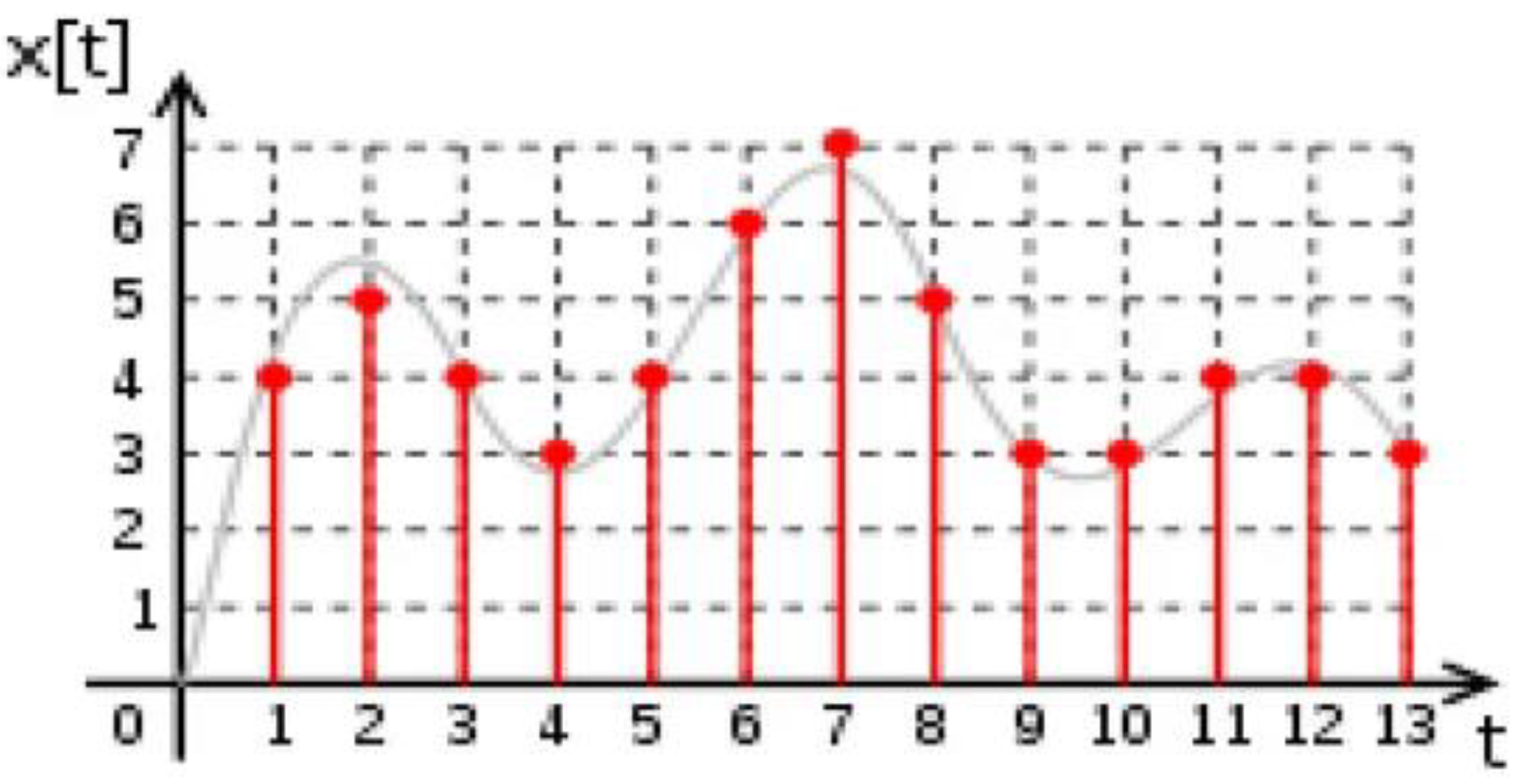

As described in [

1], the analog, mathematically continuous signal x(t) is shown in black in

Figure 1 (above).

Figure 1 represents in black what researchers used to want to measure in the 17/18/19th centuries, in calculating area.

In the 21st century, the interest is in the discrete signal in red color (also represented in its

Figure 1). The red lines in

Figure 1 represent what actually should be measured or reproduced, where some points in the red lines in

Figure 1 fall short of reaching the mathematically supposed continuous wave, and other points exceed, and there is no signal in-between — which “isolated points” are reimagined here as quantum jumps.

One recognizes now that the discrete signal in red color in

Figure 1 above is the actual cause of the measured/reproduced interpolated analog signal, which is mathematical and seems continuous in

Figure 1, but is just a scaffolding presumed and traditional, between rational values.

The utility of the method is to now recognize the analog signal in black color as historically dominant but empirically ungrounded, including measurement errors in the x-axis and in the y-axis, and not taking into account the recipient as well as the environment, while the discrete signal (numerical) in red color is more likely what is produced, and what should be reproduced.

The discrete signal--- comprising seemingly isolated points--- represents a digital signal, now familiar in CD music and text/videos on the Internet, consisting of a sequence of samples as digital packets numerically valued, which are integer values separated by quantum jumps or empty spaces with no signal.

They could also be rationals, at rational values, separated by quantum jumps or spaces, in a finite space, giving rise to isolated arbitrary-length integer quantities of exact values. Schrödinger's equation itself is quantum, not continuous, imaginary or irrational. Particles, atoms and molecules exist, matter is not continuous or imaginary.

The mathematical landscape is rich and varied, encompassing complex (C), real (R), and rational (Q) numbers, among others. Traditionally, physics has employed these constructs—particularly real and complex numbers—to model and predict physical phenomena. However, all empirical measurements and computational inputs/outputs are finite, data is discrete, and results are digitally encoded.

Quantum measurement is not probabilistic in this view [

3,

4]. This is exemplified in Eq. 1 of [

3], providing the full expression of the Schrödinger equation for bound states, including the usual boundary conditions. A similar expression, as is well-known and repeated below, could be written for the time-dependent equation.

The method in [

1] uses a new diagonal representation of the Hamiltonian.

The Hamiltonian is useful for different formulations of mechanics. The Hamiltonian is the sum, H = T + V, between kinetic and potential energy. In quantum mechanics, the Hamiltonian operator is the energy operator, which generates time evolution. In the eigenvalue formulation of the Schrödinger equation (valid for both forms), Hψ=Eψ and E is a scalar, whose eigenvalues are rational (or integer, in a finite system) numbers and correspond to the possible energy levels of the system.

Consequently, there are no complex, continuous, real-valued, or irrational eigenvalues in nature, as such values would imply the existence of infinite or imaginary information—an impossibility in physical reality.

So, all physical results can be expressed as diophantine equations ---having only integer values as solutions. The Hamiltonian is crucial in quantum theory. In that context, it's an operator. For example, in the hydrogen atom, solving the Hamiltonian gives the energy levels, also when perturbed by magnetic fields or strong laser radiation [

1,

2,

3].

The variational principle is applied to this diagonal representation, which yields closed-form expressions (also for time evolution) without imaginary numbers.

This paper seeks to re-evaluate the role of mathematical models in physics and advocates for a foundational framework rooted in discrete mathematics without imaginary numbers.

We show that some mathematically predicted values do not correspond to physical observables (see

Section 3.3, denying mathematical realism), while some observed values are ignored or even excluded by conventional mathematical models (see the derivatives of discontinuous functions [

3] and Appendices).

To resolve this disparity, we emphasize that nature---not mathematical models, representations, or authoritative consensus---must be regarded as the final arbiter of physical and mathematical truth (see also

Section 3.3, denying mathematical realism). This work aims to understand this in both aspects---physics and mathematics.

3. Methods

The methods in sub-sections 3.1 to 3.5 below comprise the interplay of physics and mathematics, affecting all natural and logical sciences. Mathematics is treated as an experimental science, not as a language. Computers are considered as digital machines with various levels of software, treated in terms of the Curry-Howard relationship and define structural logic (computers-as-proof1),

3.1. Mathematical vs Computational Hierarchies

In conventional mathematics, one finds an imagined hierarchy among number sets: C ⊃ R ⊃ Q.

Yet, from a computational and experimental perspective, this hierarchy collapses. In practice, all numerical operations, whether on digital or quantum computers, ultimately resolve to finite representations, typically as integers or rational numbers, which are not approximations as we forthcomingly show.

Our earlier work [

1,

2,

3] demonstrated that, computationally, even using the Schrödinger equation, the distinctions between C, R, and Q become irrelevant in terms of results. Read the references for further details, where in numeric terms, all observable quantities resolve to rational or integer values, without any loss of precision or physical relevance.

3.2. The Physical Nonexistence of Infinitesimal, Irrational and Imaginary Numbers

No instruments measure the numbers π, √2, or i, which cannot be numercally created either.

This is a single-failure falsifiability test, as any such experiment can prove us wrong.

A traditionally continuous fluid such as water, is made out of polar molecules, as is well-known. And there is a limit to division, physical reality does not admit the measurement of infinitesimal, irrational or imaginary numbers at any scale.

Every instrument possesses a finite resolution, and all empirical results when expressed as data, voice, image, sound, cognitively, or numerically, are invariably encoded as finite strings of symbols---integers or rational numbers---even arbitrary names.

Thus, quantities such as π, √2, or

i are imagined, abstract modeling tools, symbolic rather than physically instantiated entities. They face the insurmountable Problem of Closure [

3]--the inability to operate between rationals and irrationals in a computable way.

This invalidates Isaac Newton and Leibniz calculus [

3] but not the proposals by Mādhava [

5]. If π or √2 were irrational numbers, we could not operate with them and rational numbers, rendering the mathematical real-numbers numerically unusable.

The square root function maps to arbitrary-length rationals, not to irrationals [

3]. In finitism, to arbitrary-length integers. Such representations reinforce the notion that irrational numbers and infinitesimals are idealizations: they can be replaced by rational numbers of arbitrary-length, while they themselves are not observable, i.e., not empirically accessible. All physics equations become diophantine equations. Quantum computing becomes exact with arbitrary-length integers [

1,

2,

3]. See Footnote 1.

As a result, theories that rely on such constructs in the sets C or R risk detachment from the physical world. Approximations in the set Q in this context are not flaws, but intrinsic to physical nature. See

Figure 1.

3.3. Binary Computation in Classical and Quantum Domains

Both classical and quantum computers operate using the binary set B = {0,1} and its extensions in binary as Bn = {0, 1, 01, 10, 11, 001, 010, …}.

Classical computers implement operations through modular arithmetic, while quantum systems, though often described using complex amplitudes for an imagined, i.e., postulated, state evolution, produce outputs exclusively as discrete binary values.

Despite theoretical models invoking continuous wavefunctions, fluids, real-numbers and complex-valued amplitudes, classical and quantum computers interact with the physical world through discrete inputs and outputs.

Every observable outcome---whether the result of a classical algorithm or a quantum measurement--- is encoded in binary form. This reinforces the view that physical or software computation, at its core, is grounded in finite, discrete processes.

All inputs, outputs, and computational processes are fundamentally discrete and digital using the set B.

Moreover, such computational processes are largely independent of external physical variables such as temperature, further emphasizing their abstraction from phenomena, and from any potential continuity constraint.

This highlights a disjunction in the mathematical convention, as a formalism of continuous, probabilistic, or infinitesimal models, and the inherently deterministic binary nature (0 or 1) of computational hardware/software and experimental observation (true or false) in positive/negative logic with a possible third-state (transition, noise guard-range, uncertainty/indeterminacy, or high-impedance/open-circuit) in commercial tri-state™ chips.

Since diophantine equations are well-known to be hard to solve (i.e. Hilbert's 10th problem), this impacts scalable quantum algorithms and motivates future research, see

Section 7.

This work denies mathematical realism, where objects like π are argued to exist independently of physical instantiation, and affirms constructivism where objects exist iff (if and only if) they can be built or measured.

The assertion, well-known in physics, that “nature is the final arbiter” (see

Section 1) does

not risk conflating epistemological limits (or measurement capability) with ontological claims (what exists) because “what exists” is affirmed using constructivism (see foregoing paragraph).

3.4. Historical Precedents for Integer-Based Systems

Numerous historical precedents support the primacy of integer-based systems in modelling physical reality.

Ancient civilizations, including the Babylonians in agricultural measurements, the Mayans in astronomical calendars, and Greek devices like the gear-based Antikythera mechanism to track celestial phenomena, as well as Mādhava of Sangamagrāma (14th A.D. century) astronomical and mathematical explorations in India [

5] relied on integer-based systems to track celestial bodies and compute exact calendars. Mādhava developed calculus using rationals and expressed π as an infinite series of inverse odd numbers long before Isaac Newton and Leibniz developed their calculus using infinitesimals, as is well-known [

5].

These historical examples demonstrate that accurate and predictive modeling of the physical world in the universe does not require irrational or imaginary numbers. Instead, these examples tell us of a perceived discrete structure to the universe, one that aligns with our modern digital computing paradigm and quantum view.

The set Z of integer numbers presents at least four quantum properties [

1,

2,

3,

4], which have been used to explain calculus, the calculation of prime numbers, and non-sequential factorization of large numbers.

In particular: the first three quantum properties in the set Z are: (1) Discrete, (2) Rigorous, and (3) Isolated. Any two values must be separated from each other, and not be in contact (discrete, isolated). In consequence, they must be rigorous (exact), as a point of dimension 0. A prime number shows also a fourth quantum property of integers: indistinguishability. There is no digit "1" in "11".

3.5. Implications for Physical Theories and AI

Contemporary physics—especially quantum mechanics—relies explicitly on complex numbers in its imagined formalism. A postulated wavefunction formalism, uses them to explain state evolution.

However, if only finite, discrete and finite data are ever observable or measurable, as another single-failure falsifiability test shows, any such experiment can prove us wrong. Then reliance on continuous and imaginable constructs may be more of an unnecessary pre-quantum mathematical imagination than a physical necessity.

This perspective challenges the foundational assumptions of theories that are not empirically verifiable in all aspects [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Read the references for further details. The necessity of such continuous artifacts becomes fundamentally questionable.

This perspective suggests that the use of infinitesimals, complex and real numbers in physical theory may reflect historical diminant yet baseless mathematical traditions (a.k.a. myths) rather than physical requirements. Their role could be largely representational, not foundational. The empirical unobservability of infinitesimal,irrational and imaginary numbers challenges their physical legitimacy and underscores the need for reformulating all theories in terms that align with actual, measurable reality.

Such a shift would not diminish the predictive power of physics but rather ground it more firmly in what is observable and computable, allowing new results.

As shown in prior work [

1,

2,

3,

4] and Footnote (1), even traditionally equations using complex numbers such as Schrödinger's equation (in either form) can be reformulated in terms of discrete, real-number variables with no loss in exactness or utility. Readers are encouraged to consult the references for detailed demonstrations of these claims.

Artificial intelligence (AI), due to its computational approximations and symbolic processing, may produce “illusions” (generating information that seems reasonable but is wrong) or “erroneous results” (logical or factual errors) due to non-computable data.

3.6. Nature Has No Continuity or Imaginary Measurement

Nowhere , microscopically or macroscopically, do we find continuity in nature, in phenomena. General relativity has been discretely formulated [

19], unifying it with quantum mechanics, and resulting in an open orbit for Mercury, which corrects its perihelion in a measurable prediction. This is another single-failure falsifiability test, as any such experiment can prove us wrong.

We only find continuity in models, as if it would be fundamental, i.e., spacetime in special and general relativity, wave propagation, vector algebra, fluids, temperature, pressure, calculus according to Isaac Newton and Leibniz, Fourier and Laplace transforms, etc.

But continuous models are just approximations, scaffolding, interpolations and extensions, they do not reflect physics or mathematics, and ignore or even deny solutions. In 2023, it was proven that differentiation of discontinuous functions exist [

3], for example, allowing functions in the set Q, prime numbers, or step functions to be differentiated exactly-- see Appendices.

This was already used in 1982 [

1], in less generality. The claim of using irrational numbers, e.g. π, is a framework. Although the ratio of a circumference to its diameter is measurable, it must reflect a rational number---at whatever precision (i.e., Hurwitz Theorem), both in physics and mathematics.

The same happens with complex numbers in quantum mechanics. Although complex numbers have been used to model difference, reactive angle, superposition, interference, and entanglement, they are not needed [

3,

4].

Likewise, although complex numbers have been used conventionally to model the dynamics of quantum systems (e.g., unitary evolution), the quantum states themselves never assume a complex or real value.

We provide in [

1,

2] concrete examples that Schrödinger's equation (in any form, see also Footnote 1) can be represented exactly, or better than WKB when not exactly solvable, by diophantine equations.

3.7. New Model

We now define a quantum computational model based entirely on rational and finite arithmetic [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]:

3.7.1. Rational State Space

We represent quantum states as vectors in Qn or overZnp , where p is a suitably large prime. This replaces complex Hilbert spaces with finite or rational vector spaces. Quantum gates are defined as invertible rational matrices.

3.7.2. Deterministic Measurement and Eigenvalues

Measurement is modeled by deterministic logic based on rational thresholds or algebraic equivalence classes, as eigenvalues of operators. Superposition, entanglement, and quantum jumps are represented as structural constraints in a system of rational equations, rather than via non-local probability distributions.

3.7.3. Improved Shor’s Algorithm (ISA)

The standard Shor’s algorithm is divided into discrete stages:

Select a random integer a such that gcd(a,N)=1.

Calculate ax mod N over a rational finite space Zq.

Apply a rational Fourier-like transform over Zq to extract the period r.

Use continued fractions (entirely rational) to estimate r.

Determine nontrivial factors via gcd(ar/2 +/- br/2, N), for b=1 (for cybersecurity, b>>1).

All operations are computable using only rational arithmetic or modular operations.

4. Results

We implemented the rational reformulation on a conventional simulator, modeling the factorization of using N=15 and a=2:

Computation of 2x mod 15 showed periodicity of 4.

Rational Fourier-like transform identified the dominant rational frequency component.

Continued fraction approximation with b=1 yielded r=4.

gcd(22 - 1, 15)=3, and gcd(22 +1, 15)=5.

All results matched those of the conventional quantum algorithm, without use of imaginary numbers, irrational numbers or real-number probabilities.

Scalability: The same method applies to larger N, with performance limited only by computational power. No loss of generality was observed from restricting the model to rational values.

Implications:

A rational, deterministic model preserves the algorithmic integrity of quantum computing.

This aligns with digital logic and cryptographic precision.

It removes reliance on non-physical constructs like e>0, continuity, or infinite precision.

From this perspective, infinitesimal, irrational and imaginary numbers are re-interpreted as arbitrary-length ratios and computational constructs.

Under finitist assumptions, all physical quantities reduce to arbitrary-length integers, which show four quantum properties. Consequently, all physics equations may be expressed as Diophantine equations. This reformulation preserves precision and aligns more closely with empirical and computational practice.

This discrete paradigm is already supported by the operational logic of both classical and quantum computers, as well as by the long history of digital computation in science. Replacing continuous abstractions with Diophantine formulations allows for models that are not only physically grounded but also amenable to efficient computation and verification.

6. Conclusion

A discrete foundation (Q/Z) aligns theory with observed reality, in all sciences, and times.

We propose a shift in perspective: to ground physical and mathematical theories in observable, computable, discrete mathematics rather than in continuous abstractions. This is a falsifiability test as any such experiment can prove us wrong.

By aligning theory with what can be observed, measured, and computed, we may develop models that are not only consistent just according to imagination, but practically aligned with nature, which is observably discrete. This satisfies the needs of AI (e.g. to avoid “hallucinations”) and human intuition.

The history of scientific computation and the binary logic of both classical and quantum systems support this discrete paradigm. Future research should explore reformulations of quantum mechanics and other physical theories that avoid reliance on infinitesimal, irrational or imaginary numbers. Such developments hold promise for advancing both foundational physics and applied computational fields.

7. Forward

As in [

1,

6,

7], since 1982 QC can be expressed as diophantine equations, revealing QC as a fundamental model to understand nature [

1] and bypassing approximations inherent in continuous models (nature is understood to be quantum ontically).

Our work on the physical representation of quantum systems [

6,

7] explores how physical representations (using the mathematical sets C and R) differ from the numerical and computational aspects (using the sets Q and Z) of well-known quantum mechanics.

Diophantine equations were independently proposed by Vernon Neppe and Edward Close [

8] to represent nature, and by others, such as Nigel Phillips [

9], and Christian Wolf [

10]. A software can use current digital hardware, or better.

Edward Fredkin’s Digital Physics [

11] proposes that the universe is fundamentally computational, with discrete information as the basis of reality. Wolfram, S. [

12] proposes cellular automata as fundamental physics.

In Causal Set Theory, one finds a discrete approach to quantum gravity where spacetime is a partially ordered set of events [

13].

In Lattice Gas Automata & Discrete Fluid Dynamics [

14] Hardy, J., Pomeau, Y., & de Pazzis O., the time evolution of a 2D classical lattice system is studied.

On Quantum Foundations & Discrete Structures, one finds “Quantum Graphity: Space as a dynamical graph of interacting qubits”, by Konopka, T., Markopoulou, F., & Smolin, L. [

15], which can be extended to [

16] -- and further examines how causal structure in discrete models can give rise to relativistic physics.

In Finite Information Theory (FIT), Gisin [

17] argues that the standard identification of initial conditions in classical mechanics with real numbers (set R) is problematic because almost all real numbers contain an infinite amount of information (i.e., unphysical).

Neppe and Close [

8] have also proposed a 9D+ model that concludes the same we propose in Physics applications with QC and +12 dimensions, that anything in nature can be modeled as a diophantine algorithm, giving exact and fast results as isolated points in the sets Q or Z (in a finite set).

This is a form of digital physics or mathematic universe hypothesis. Simulating nature becomes a matter of solving these equations, which QC can do efficiently. Hence, using diophantine-based equations would align with how nature works, making them more fundamental and more secure.

The thought cf. [

1,

6,

7] is that this approach could be more applicable in physics, mathematics, and cryptography by grounding results in Diophantine representations of quantum processes with +12 dimensions, which are seen as fundamental to nature. This proposal could have wide-reaching implications in all fields, offering new ways to securely handle verification and computation -- and modeling gravity in QFT (quantum field theory).

This framework proposes a paradigm shift where diophantine equations is a lens to unify quantum computation, mathematics, cryptography, and physics, including gravity.

Diophantine-based equations could run on classical hardware systems (as used in a CRAY supercomputer [

1] or cellphone), enabling immediate adoption in blockchain or smart contracts, and AI. This democratizes access while showing quantum advantage as a

benchmark.

By decoupling from classical hardness assumptions, the framework could future-proof cryptographic systems against quantum threats, now immediate.

By modifying conventional mathematics to model quantum processes, this work offers a path to practical use for blockchain and beyond, while grounding QC in a theory of nature itself (nature as ontically quantum).

Further research is needed to formalize the diophantine-QC link and demonstrate scalable implementations using the sets Q or Z with +12 dimensions.

This view directly contradicts interpretations that treat irrational and imaginary numbers as ontologically real, such as those argued by Renou, Acín, and Navascués [

18]. These constructs, while mathematically well-defined, have no empirical instantiation in nature. Even simple inconsistencies—like i+(−i)=0—underscore the conceptual fragility of using imaginary numbers to describe real systems.

Going forward, we propose a discrete, Diophantine-based +12 dimension foundation for physics, mathematics, and quantum computation. Such a framework not only offers a better fit with empirical observations and computational tools but also provides a unified language for science and technology. Future research should focus on formalizing the link between Diophantine methods and scalable quantum implementations grounded in rational and integer structures. Quantum states never collapse to real or complex numbers, as is well-known.

FUNDING: This research received external funding from Network Manifold Associates, Inc. (NMA), Safevote, Inc, and Planalto Research. The author declares no conflict of interest. This result is public and online, without material nonpublic information here.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: The author is indebted to the work of late Mādhava of Sangamagrāma, M.Sc. Ann Gerck, NMA early investors; Don Sawtelle at Planalto Research in C coding, and five anonymous reviewers.

ResearchGate discussions and private messages were also used, for “live” feedback, particularly in

Section 3. We are, of course, very interested in hearing thoughts on this matter. If the reader has any feedback or suggestions, we would greatly appreciate your input.

APPENDIX I -- Unifying Framework: The Set Q

This Appendix confirms our results that R=C=Q computationally — it represents a unifying framework in discrete (quantum) mathematics for some of the most fundamental mathematical sets. Their mathematical distinctions are neither ignored nor conflated with a computational representation. Nothing is uncountably infinite either (which is not physical), just countably with an arbitrary-length.

There are no “continuous” systems at all (i.e., all systems are quantum) or that require continuity, even though mathematically assumed so -- but never proven (just authoritatively based). In fact, QM teaches otherwise, in all physical experiments. Discrete rationals (set Q) are

not an approximation of R or C [

1]. Equivalence in computational models (e.g., Turing machines) does not negate the Curry-Howard relationship (programs-as-proofs) in mathematical properties.

The Curry-Howard relationship defines structural logic, quantum information that is discrete ontically, and this sidesteps Gödel's incompleteness theorems (stated before the Curry-Howard relationship) by using consistent formal systems capable of expressing basic arithmetic with sets R, C and Q, so that there exist no true mathematical statements that cannot be proven within a system. Further, by using sets R, C and Q, any consistent formal system can prove its own consistency, e.g., 1=1, 0=0, and 0≠1. This is tangential to this Appendix and will be mathematically considered elsewhere.

Albeit the bias of humans, some conclusions can be absolute, such as the law of gravity.

No matter what formulation is chosen for gravity, from Newton, Copernico, Einstein, or from none of these, as the ancient Mayans are well-known to have done (i.e., using integers, with no physical model of cosmic objects), astronomical calendars can be exactly calculated into millennia in the future or the past.

The lesson is that such necessity (structural) is the mother of invention. In German, one says: “Aus der Not, eine Tugend machen”.

We now need to move forward, and it is no longer a choice -- we need to complete the structure, to evolve.

The parts need to meet, it is the Holographic Principle upon our time.

Mathematics can meet physics. Infinitesimals and imaginary numbers are not needed, there is no contradiction.

We arrived then at the conclusion that any mathematical choice against R=C=Q has an extremely low chance to succeed. This is not a probabilistic result, but number theoretic.

The calculations of digital computers are correct without any reasonable doubt: Numbers and nature can become holographic, and phase can now be taken into account in numbers, not just amplitude. The quantum method of the 1982 paper has been verified correctly in 2023 cf. [

1] proving, for the first time, the differentiation of discontinuous functions. This was used in 1982 using a classical CRAY supercomputer at the MPQ with quantum-supporting software [

1]. This was the first functional software-based quantum computer using numeric quantum jumps as in Eq.(1).

Real-numbered QC (using Q, instead of R or C) is both theoretically and experimentally possible cf. [

1] in QM, with no loss in computational advantages [

1]. Replacing C or R with discrete sets (e.g., Q) is also well-known in digital computing, even in coprocessors, with ever larger registers.

Importantly for QC, software can use only the sets B={0,1} and B

n while the hardware can use only the set B={0,1}, for rigorous and faster results, as has been verified correctly in 2023 [

3]. The sets R, C, the irrationals, and the p-adic numbers do not appear at all in digital computers, which proves a negative on their need for physical use in QC.

Existing QC implementations (e.g., IBM Qiskit, Google Cirq) rely on complex numbers, and are deprecated here. Further, through deep connections in number theory, algebraic geometry, quantum mechanics, and representation theory, R, C, and Q are intertwined in ways that illuminate profound truths about mathematics and nature, both represented in physics. Current physical theories (e.g., general relativity, quantum field theory) cannot be rooted in supposedly “continuous” mathematics in a quantum universe.

We present numerical evidence that using complex numbers lead to nonsensical additions, which are seen as a prelest but not as a flaw, such as the sum of two imaginary numbers producing a real number, from straightforward -- if one has i + (-i) as 2 imaginary numbers, that produces 0, which is a real-number -- to 3rd degree and higher polynomials.

This work, based on numerical results anyone can calculate, and quantum computing (QC), deprecates physical complex numbers (the set C) in QC. The set C uses an impossible operation, the square-root(-1), inexpressible in the set Q. The imaginary and real-numbers cannot be kept apart, in any encoding.

The foregoing doesn't mean deprecating phase, one just has to use a different model to achieve measurable, consistent, and necessary results -- as computers do.

This accords to the well-known Hume's principle, that the number of things with the property G equal the number of things with the property E iff (if and only if) there is a one-to-one correspondence between those that are in E and those that are in G.

This work, given the conventional reliance on C that is deeply rooted in QM, displaces it as a paradigm shift supported by both the theoretical and experimental evidence cited here. Since QC can be modeled with the set {0,1} exclusively, there's no need for any other number sets, hence proving (by Hume’s principle) a negative on their physical and theoretical use. This aligns with digital physics, positing nature as fundamentally (i.e., ontically) discrete.

Implications and Challenges

Paradigm Shift: We propose a paradigm shift from continuous to discrete foundations in physics, aligning with quantum gravity approaches that posit discrete spacetime.

Mathematical vs. Physical: We distinguish mathematical tools (R/C) from physical reality (Q/B). We negate the ontological status of supposedly continuous quantities (R/C).

Technical Feasibility: While discrete QC was experimentally demonstrated in 1982 and theoretically confirmed in 2023 cf. [

1], practical implementations (with persistent error issues of correction, scalability) remain in use. The efficiency of discrete vs. continuous models needs no more empirical comparison but just to overcome bias.

APPENDIX II -- Differentiation of Discontinuous Functions

Differentiation can directly use isolated points and quantum jumps or spaces, without needing distribution theory [

3]. That would make calculus more aligned with discrete signals and digital processing, where samples are at specific points separated by empty spaces. This also contradicts the well-known Shor’s algorithm.

Our critique of Shor's algorithm is

not that it relies on continuous Fourier transforms or some aspect of real-numbered periodicity, but that Shor's algorithm is probabilistic and does not allow knowing the periods of individual primes. A discrete framework would allow the QFT used in Shor’s algorithm, which is discrete, to work with any numbers of finite cyclic groups directly, not just with integers mod N. Albeit, the proposed framework provides a more foundational mathematical basis for such discrete algorithms without relying on supposedly continuous real numbers — creating a more compatible and number-theoretic basis for ISA (see Section 2.4 in [

4]).

So, while Shor's algorithm uses a discrete QFT, the proposed framework provides a more foundational basis without real or complex numbers, directly using discrete numbers in finite cyclic groups. This aligns with quantum computing's discrete state space and doesn't contradict Shor's method at all.

Working backwards in a compatible way, the first fundamental theorem of calculus defines the new definition of differentiability as capable of providing a primitive by integration cf. [

3], as antidifferentiation, where differentiation provides the reverse path. The integral must be a numerically measurable function, and one can observe that continuity is not required. Here, to “measure” is always intended to mean “of some physical, real-world quantity, numerically” cf. [

3]. One cannot also demand continuity before one starts to measure what

must represent a lack of continuity, not a “pathology”, just a change.

Next, [

3] provides two examples of the new definition of differentiability, besides every point of the set

Q itself, and not necessarily linked to QM.

The function |x| (module of x) seems to create a well-known problem in mathematics, using the set R. Its derivation is discontinuous at x = 0, and cannot be mathematically differentiated twice. However, the discontinuity at x=0 is a change, and creates no problem in this formulation, using the set Q and not using distributions.

Every function in the set Q is:

So, step functions are naturally differentiable at every point in the set Q.

The well-known second theorem of calculus connects the integral of the derivative of |x| with |x|.

Another example cf. [

3] is the step-wise function, which further explains the result above, in more generality, as in (Eqs.(2-4), below:

y(x)=1 forallx<5, y(⁵x)=7 wℎenx=5, and y(x)=2 forallx>5; (Eq.(2)

First, this is a (numerically) measurable function as above and can be integrated easily. The integral (called the primitive) is:

I(y) = xforx<5, 35 forx=5, and 2x for x>5; Eq.(3)

when integrated by parts, using the well-known Linearity Property.

Eq.(2) can also be differentiated, giving:

y’ = 0 + an impulse delta function (not a distribution) of value 6 when x=5.

Integrated, to check, this returns to y + c, where c is a constant, which is calculated to be equal to 1, reproducing y(x) in Eq(2).

Therefore, discontinuous functions can be integrated and differentiated. The condition for differentiation is no longer continuity, but that the result be measurable. Ignoring this infinite class of solutions is a current problem in physics and mathematics, and deprecates R.

This framework bridges numeric reality with mathematical formalism, prioritizing measurability and discreteness in numerical terms. It offers tools for modern applications such as QC, while critiquing classical assumptions and Shor’s algorithm, advocating for a paradigm shift in calculus pedagogy and application, aligning with quantum computing's discrete state space.

The described framework challenges classical calculus by redefining differentiability through the lens of discrete signals and (numerically) measurable functions, emphasizing physical measurement realities. Continuous waveforms are “supposed interpolations”, introducing errors ad hoc.

Note

| 1 |

The observation that there is an isomorphism between the proof systems and the models of computation. |

References

- Gerck, E. (1982). Solution of the Schrödinger Equation for Bound States in Closed Form. Physical Review A, 26, 662. Free author copy at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/236420748/. Accessed April 20, 2025.

- Gerck, E. (1983). Scaling Laws for Rydberg Atoms in Magnetic Fields. Physical Review Letters, 50, 524. Free author copy at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/243470610/. Accessed April 20, 2025.

- Gerck, E. (2023). Algorithms for Quantum Computation: The Derivatives of Discontinuous Functions. Mathematics, 11(1), 68. Free author copy at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/366577895/. Accessed April 20, 2025.

- Gerck, E. (2025). RSA-2048 Today and Quantum Computing. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/374155658/. Accessed April 20, 2025.

- Historical studies on the Mayan calendar, Mādhava calculus in India, and the Antikythera mechanism. (Various sources).

- Gerck, E. (2021). Tri-State+ Communication Symmetry Using the Algebraic Approach. Computational Nanotechnology, 8(3), 29–35. Free author copy at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/355406882/. [CrossRef]

- Gerck, E. (2021). On the Physical Representation of Quantum Systems. Computational Nanotechnology, 8(3), 13–18. Free author copy at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/355406639/. [CrossRef]

- Neppe, V. M. , & Close, E. R. (2020). The Neppe-Close Triadic Dimensional Vortical Paradigm: An Invited Summary. International Journal of Physics Research and Applications, 3, 001–014.

- Phillips, N. (2025). Retrieved from https://www.linkedin.com/in/nigel-phillips-coder/. Accessed April 20, 2025.

- Wolf, C. G. (2025). Values of the Fundamental Physical Constants. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/368809501 Accessed April 20, 2025.

- Fredkin, E. (1990). Digital Mechanics: An Informational Process Based on Reversible Universal Cellular Automata. Physica D, 45(1–3), 254–270.

- Wolfram, S. (2002). A New Kind of Science. Champaign, IL: Wolfram Media.

- Sorkin, R. D. (2003). Causal Sets: Discrete Gravity. arXiv:gr-qc/0309009.

- Hardy, J., Pomeau, Y., & de Pazzis, O. (1973). Time Evolution of a 2D Classical Lattice System. Physical Review Letters, 31, 276. [CrossRef]

- Konopka, T. , Markopoulou, F., & Smolin, L. (2006). Quantum Graphity: Space as a Dynamical Graph of Interacting Qubits. arXiv:hep-th/0611197.

- Konopka, T. (2012). Causal Graph Dynamics and earlier work on Quantum Graphity. arXiv:hep-th/0611197.

- Gisin, N. (2019). Indeterminism in Physics, Classical Chaos, and Bohmian Mechanics. Foundations of Physics, 49, 707–721.

- Renou, M. O. , Acín, A., & Navascués, M. (2025). Quantum Physics Falls Apart Without Imaginary Numbers. Scientific American. Retrieved from https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/quantum-physics-falls-apart-without-imaginary-numbers/. Accessed April 20, 2025.

- Gerck, E. V. Gerck, E. Extending GR to Include QM: The Perihelion of Mercury. Preprint, 2019, online at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/331035146/.

- Shor, P. W. (1994). Algorithms for quantum computation: Discrete logarithms and factoring. Proceedings 35th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science.

- Rivest, R. L., Shamir, A., & Adleman, L. (1978). A method for obtaining digital signatures and public-key cryptosystems. Communications of the ACM, 21(2), 120-126.

- Bishop, E., & Bridges, D. (1985). Constructive Analysis. Springer.

- Schumacher, B. & Westmoreland, M. D. (2010). Quantum Processes, Systems, and Information. Cambridge University Press.

- Nielsen, M. A. & Chuang, I. L. (2010). Quantum Computation and Quantum Information. Cambridge University Press.

- Knuth, D. E. (1997). The Art of Computer Programming, Vol. 2: Seminumerical Algorithms. Addison-Wesley.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).