1. Introduction

During 2024, Ecuador experienced a severe energy crisis due to climatic factors, low investment, and lack of maintenance of the electrical power system (EPS) [

1]. Low rainfall limited electricity generation from the main hydroelectric plants, causing prolonged power outages of up to 14 hours a day in several sectors of the country.

In 2023, the annual growth rate reached 9.6%, far exceeding the historical average of 4% per year. To meet electricity demand, the Paute Integral complex, comprising the Mazar, Molino, and Sopladora hydroelectric power plants, contributed 34.1% of the total. In contrast, the Coca Codo Sinclair hydroelectric power plant contributed 29.2% [

2].

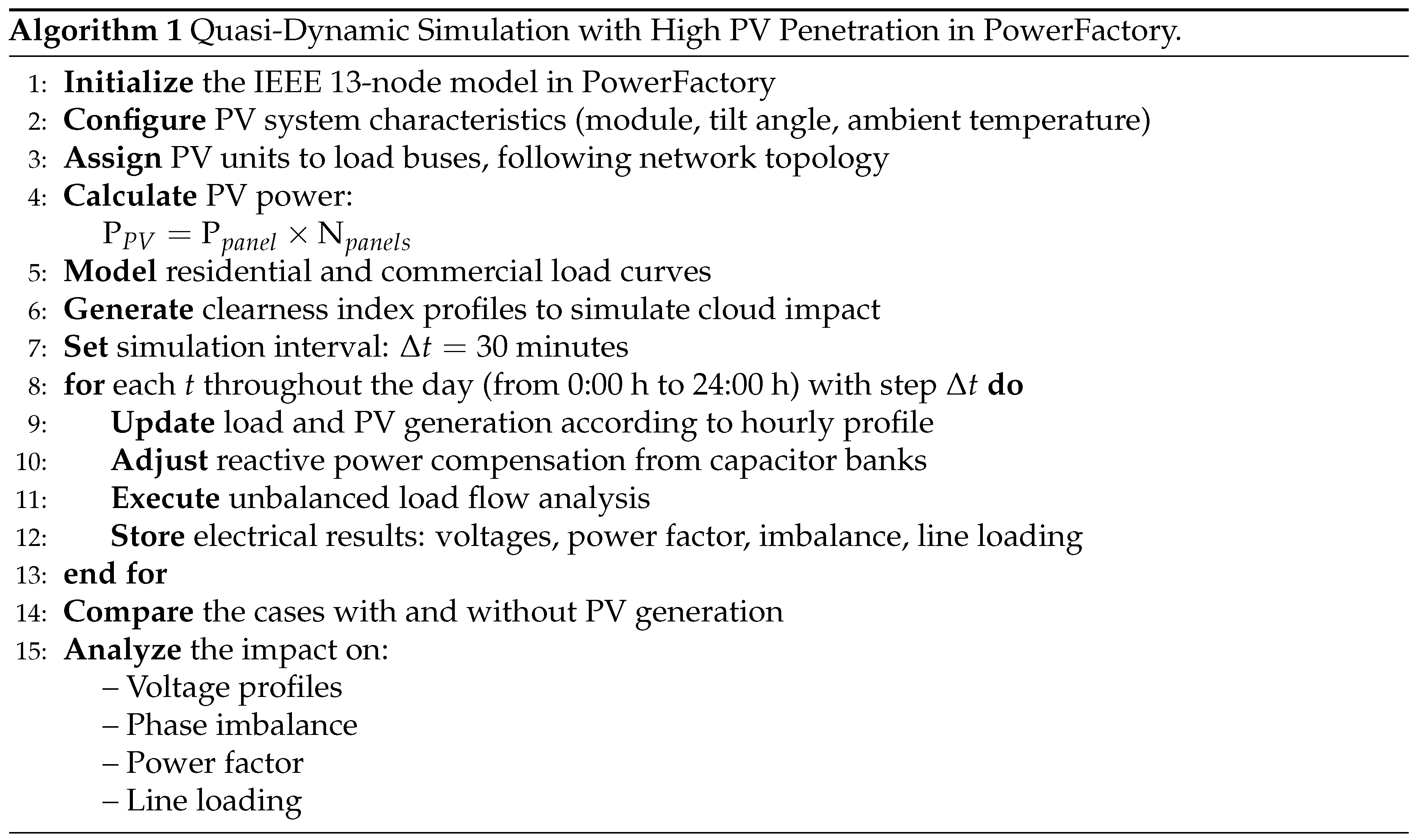

Figure 1 shows the country’s cumulative annual demand curve for 2024, with a maximum of 5104 MW [

3].

According to the latest Electricity Master Plan, 58.7% of generation comes from hydroelectric sources [

2]. However, during the same year, the Paute Integral complex was at risk of operation due to low reservoir levels caused by one of the most severe droughts in the last 61 years [

4].

Given this background, Ecuador’s EPS was limited in its operations, so both residential and commercial users relied on combustion-powered generators or PV panels to meet their energy needs [

5]. As a result, there was a significant increase in the installation of solar panels as an alternative for generating electricity. This solution helps mitigate the generation deficiency; however, it is necessary to analyze how it could affect the electrical grid’s performance once the drought ends and the system returns to normal operation.

PV has become a viable solution to rising electricity demand. It is estimated that this type of generation, together with other renewable sources (wind, hydro, etc.), will account for 86% of total electricity produced worldwide by 2050 [

6]. Despite being a significant step forward in diversifying the energy matrix, the widespread adoption of PV generation technology creates unique research challenges centering on the instabilities caused by the technology’s implementation limitations. Unlike synchronous generators, PV generation systems lack an inertial response, and are incapable of providing the necessary contingencies to support and stabilize the system [

7,

8,

9].

PV integration has become a common practice globally, driven in particular by the growing demand for clean energy sources as alternatives to fossil fuels. PVs offer technical benefits, including reduced transmission and distribution losses, increased system resilience, lower generation costs, and reduced need for conventional capacity expansion. However, their large-scale integration must be carefully considered to avoid effects on the stability and security of the electrical system [

10].

Scientific literature examines the effect of PV integration on electrical systems. For instance, [

11] looks at the western electrical system of the Democratic Republic of Congo, base capacity of 2012 MW, analyzing the system’s behavior under various PV penetration levels. The study assessed active power loss, voltage stability, harmonics, among other indicators. The study found that PV generation between 10 percent and 20 percent insertion levels loss reduction PV generation, without compromising operational stability. However, above 30 percent, the system technically degrades, which is reflected in increased voltage oscillations and harmonic distortion due to the low inertia of inverter technology. The study suggests incorporating supplementary harmonics filtering and storage systems, STATCOM and other support systems to ensure the system’s reliability.

In [

12], it was demonstrated that PV insertion generally improves voltage stability, although its location negatively affects voltage levels. In addition, other studies have shown that excessive PV integration can cause bidirectional power flow problems and voltage instability; however, these issues can be mitigated through reactive power support from the photovoltaic inverter [

13,

14].

To understand the effects of high PV generation penetration on power quality indices, [

15] provides an extensive overview of the approaches taken for this purpose. The review analyzed a number of deterministic and stochastic approaches, noting that the latter offers a more accurate description of the behavior of the electrical system by factoring in the variability of solar generation. The review describes voltage regulation as the principal technical challenge, even at low levels of PV penetration, stating that the higher levels can cause a multiplicity of power quality issues. In addition, [

16] pointed out that the integration of large-scale PV systems requires contemporary electrical systems to develop new control mechanisms because of its power quality effects and the reduction of system inertia. Therefore, under conditions of high PV penetration, smart control, and battery storage are required to stabilize the system.

On the other hand, [

17] conducted a detailed review of the impacts of high PV penetration on the reliability and stability of electrical systems. The study covered effects on voltage, frequency, harmonic distortion, protections, and flexibility requirements. The study highlights the critical characteristics of PV systems that condition their effective integration into electrical grids.

Here, one consideration tied to the large scale integration of photovoltaic generation systems is the challenges of voltage stability, which is described as the ability of an Electric Power System (EPS) to keep all nodes in the system within the desired operational voltage levels under normal and post-disturbance conditions [

18]. Stability challenges have been documented as one of the primary factors contributing to the increased prevalence of blackouts in the world [

18,

19]. In this regard, the behavior of the system is significantly influenced by the location of the distributed generation sources; when distributed resources are poorly sited, the risk of unstable voltage conditions in the locality or the system as a whole is heightened [

20,

21]. Therefore, it is crucial to consider not just the amount of generation to be injected, but the point of interconnection in the network.

Active power is one of the primary variables that affect voltage stability, as considerable changes to its amount or method of injection alter the voltage response. This is of greater importance when the power generation source is stochastic, such as photovoltaic systems or wind power, as they are reliant on external conditions that fluctuate. This is why study [

22] suggests the analysis of the coordinated control of active and reactive power as a means of keeping voltage in a given operational band.

In the literature, many studies deal with the integration of PV generation into electrical systems, although, it is important to assess the behavior of the system from a quasi-dynamic perspective to enable the capture of the time evolution of the electrical grid as PV power is injected in a step-wise manner. Hence, this article proposes a quasi-dynamic analysis of a 13-node IEEE test system in order to capture the behavior of the electrical grid over the entire day when active power generated from photovoltaics is injected.

The article is structured as follows: after the introduction,

Section 2 describes the materials and methods used for this research.

Section 3 presents the case studies, while the results and discussions are presented in

Section 4. Finally,

Section 5 presents the conclusions, emphasizing the most relevant aspects of the simulation results.

2. Materials and Methods

Photovoltaic systems depend directly on solar irradiance, leading to temporal variability in energy production. This characteristic necessitates the application of quasi-dynamic simulation methods to analyze the system’s behavior using continuous power flows. To better represent the system’s operation, the simulations accounted for the effects of clouds throughout the day, given their direct impact on irradiance and, consequently, on photovoltaic generation. To this end, an artificial intelligence-based model was used to generate cloudiness index profiles with random variations, emulating the intermittency caused by passing clouds. This approach enhances the analysis’s accuracy, enabling evaluation of the electrical grid’s performance under variable atmospheric conditions throughout a full day of operation.

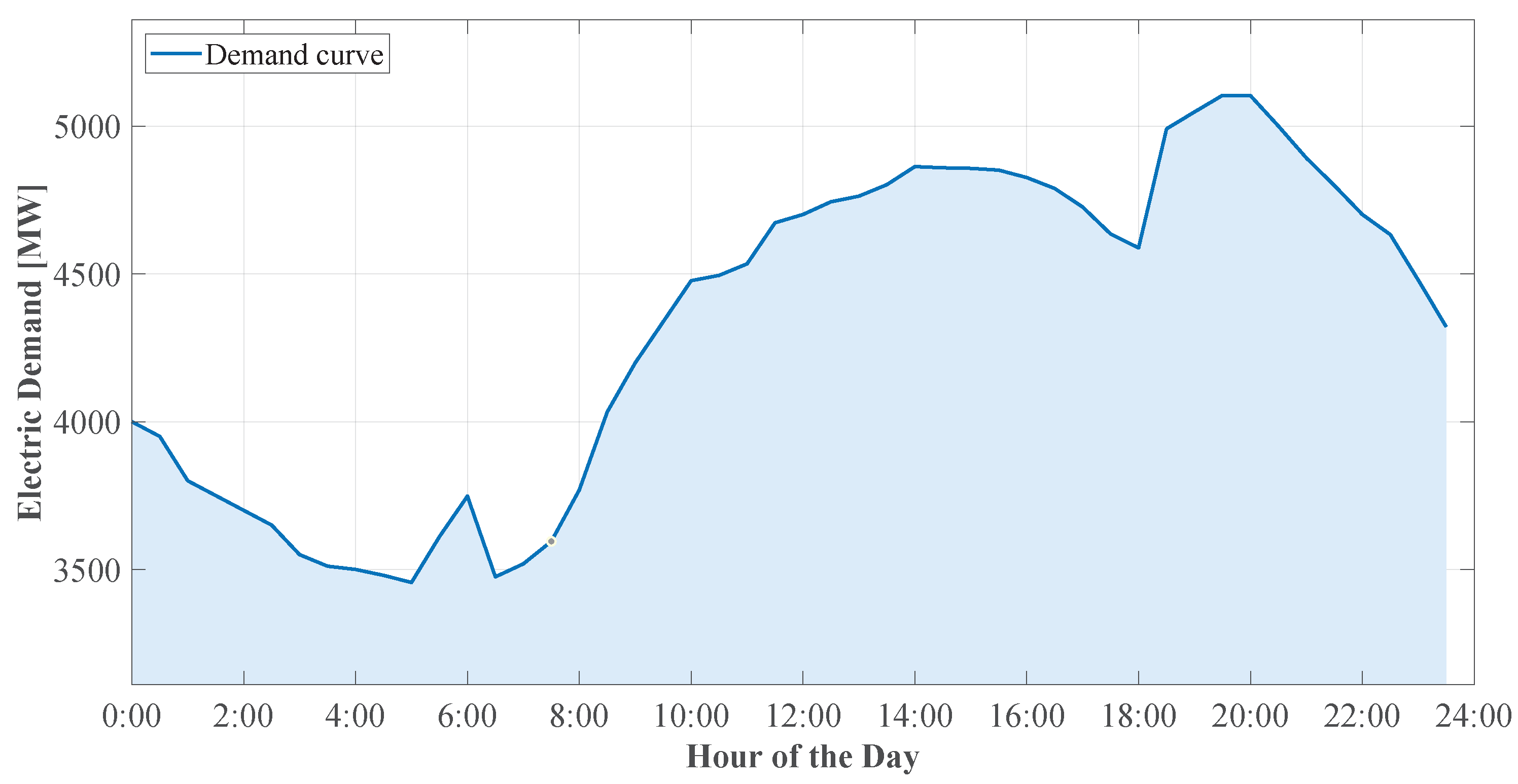

Some studies have addressed the influence of tilt angle and orientation (

Figure 2, [

23]) on PV performance; however, given the geographical location, it is proposed to simulate with a tilt angle of 10°. Deviations from the optimal configuration result in considerable energy losses, particularly in equatorial areas, where the optimal annual angles differ by 5.1°. In addition, ambient temperature and increased irradiance significantly raise the module’s operating temperature, directly impacting its performance [

24,

25,

26]. For this reason, the simulations accounted for variations in ambient temperature, as these affect the actual power generated by the photovoltaic system.

Now, within the PowerFactory simulation environment, the real power generated can be entered manually or automatically based on the PV module type, array configuration, the specific moment (date and time for simulating power flows at a particular instant), and irradiance levels. In general, the system’s total power is obtained by multiplying the nominal capacity of a single photovoltaic array by the number of inverters connected in parallel. Equation (

1) allows the generation capacity of the system to be dimensioned based on the unit power of the modules and their quantity associated with each inverter [

23].

Donde:

represents the total active power of the photovoltaic system.

is the active power generated by an individual panel.

corresponds to the total number of panels connected to an inverter.

Table 1 shows the electrical parameters of the photovoltaic module used in the simulation. Each inverter was connected to the type of load associated with its corresponding node —single-phase, two-phase, or three-phase —so that the inverter connections accurately replicate the power supply scheme of the associated load, maintaining an adequate representation of the system’s behavior.

2.1. Quasi-Dynamic Simulation

Quasi-dynamic simulation is geared toward medium- and long-term electrical studies. This technique involves the successive execution of multiple load flows (in this case, unbalanced load flows) using previously defined time steps. The analysis aims to represent long-term load and generation profiles and to simulate the network’s evolution over time. One advantage of this tool is its computational efficiency, as it does not require solving all the equations of the complete dynamic system, thereby speeding up calculations. The quasi-dynamic method has been shown to provide high fidelity, which is why it has been adopted in studies of photovoltaic systems, among others [

27].

To perform the quasi-dynamic simulation, a full-day analysis period was selected, with a 30-minute calculation interval between steps. This allows for more detailed results on the evolution of the electrical system throughout the day. Although it is possible to reduce the step size to achieve a higher level of detail, it is not strictly necessary, as it would entail a longer simulation time without a significant benefit in the context of the analysis.

2.2. Unbalanced Load Flow

As the basis for quasi-dynamic analysis, unbalanced load flow helps determine how the system’s behavior changes while maintaining the real operating conditions of a three-phase distribution network, despite phase imbalances. This method solves several load flows sequentially, changing photovoltaic injection and load at each step. phase imbalances must be accounted for, as they are common and must be considered for load flow calculations to produce more accurate results. Reachable/setable conditions of the EPS are established and the electrical parameters are defined through load flow. Many studies approach the load flow problem using numerical methods, among which the Newton-Raphson method is the most popular, due to its rapid convergence compared to Fast Decoupled and Gauss-Seidel methods [

28,

29,

30].

In the analysis of three-phase load flow in unbalanced distribution networks, the system formulation is based on the relationship between injected currents and voltages, as expressed through the nodal admittance matrix (Equation

2). This relationship is expressed in matrix form, accounting for the coupling between phases, as shown in (

3). In it, the interactions between phases

a,

b, and

c are modeled in each pair of nodes in the system [

31].

where:

: Vector of phase currents (a, b, c) injected into node n.

: Vector of phase voltages (a, b, c) at node n.

: Three-phase admittance matrix in phase coordinates.

: Vector of three-phase currents injected into the node

: Vector of voltages (a, b, c) at node j.

: Admittance matrix between nodes i and j.

The current injected from phase p of bus

i is obtained using equation (

4), which accumulates the effect of the voltages in all connected phases. Meanwhile, the complex power is represented according to (

5), where the characteristic non-linearity of the problem is introduced.

where

is the coupling between phases

p and

q at nodes

i and

k, and

and

correspond to the voltage and current in phase

p of bus

k.

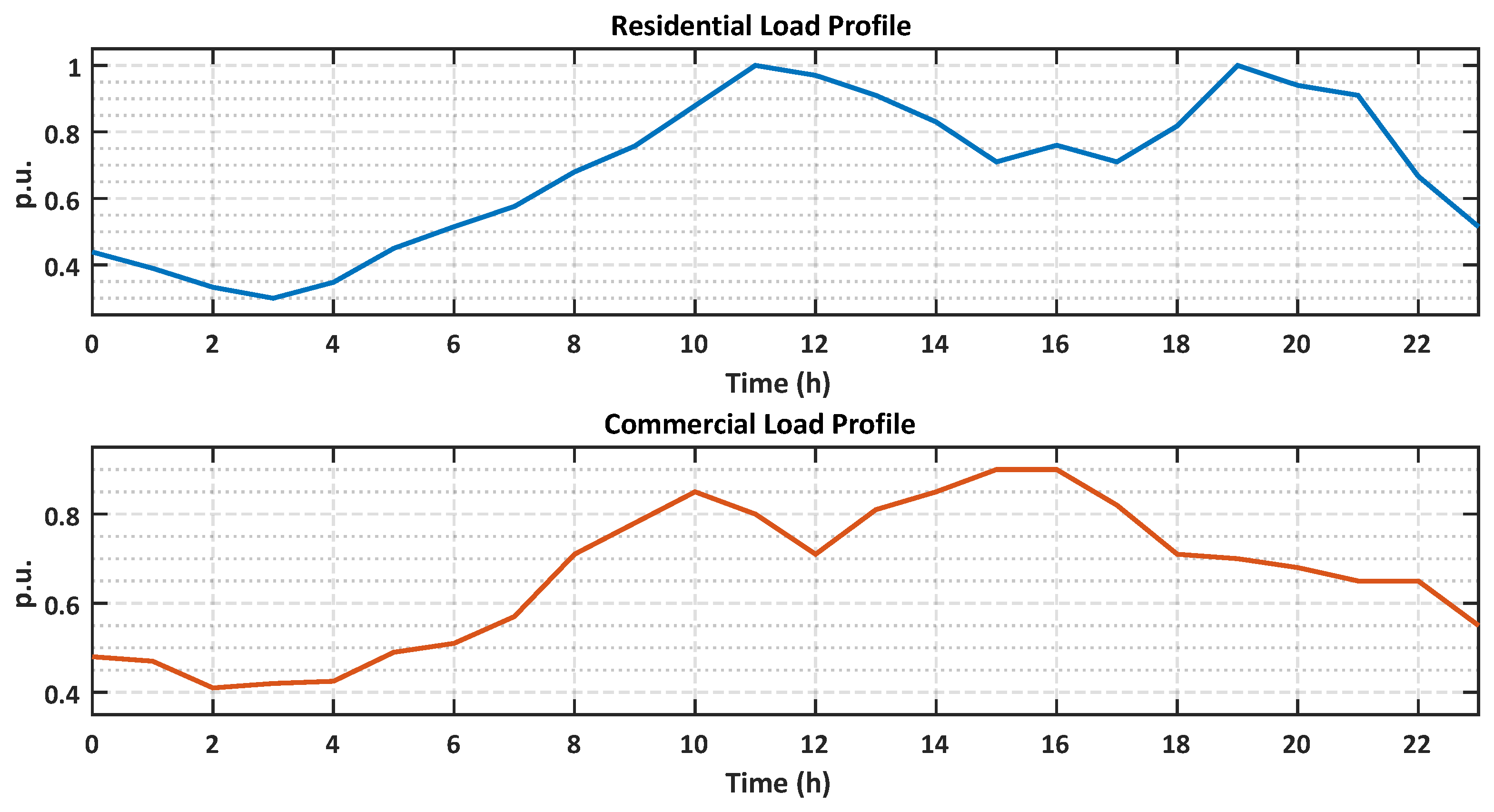

The quasi-dynamic simulation process in PowerFactory is summarized in Algorithm 1, which describes the steps for modeling the load and photovoltaic generation profiles and performing an unbalanced load flow analysis at each time interval. The results allow for a comparative evaluation of the main electrical parameters in scenarios with and without photovoltaic integration.

3. Case Study

Two analysis scenarios are proposed for the study. In the first scenario, a quasi-dynamic simulation is performed, considering only hourly load variation, without PV generation. This scenario will serve as a basis for comparing the effects of incorporating PV generation into the system. In the second scenario, in addition to demand variation, PV generation is included, modeled based on hourly profiles of ambient temperature and specific climatic conditions for the Ecuadorian location. This data represents the effect of clouds, providing a more realistic representation of energy production in the PowerFactory simulation environment. It is worth noting that the load power factor was maintained constant throughout the simulation.

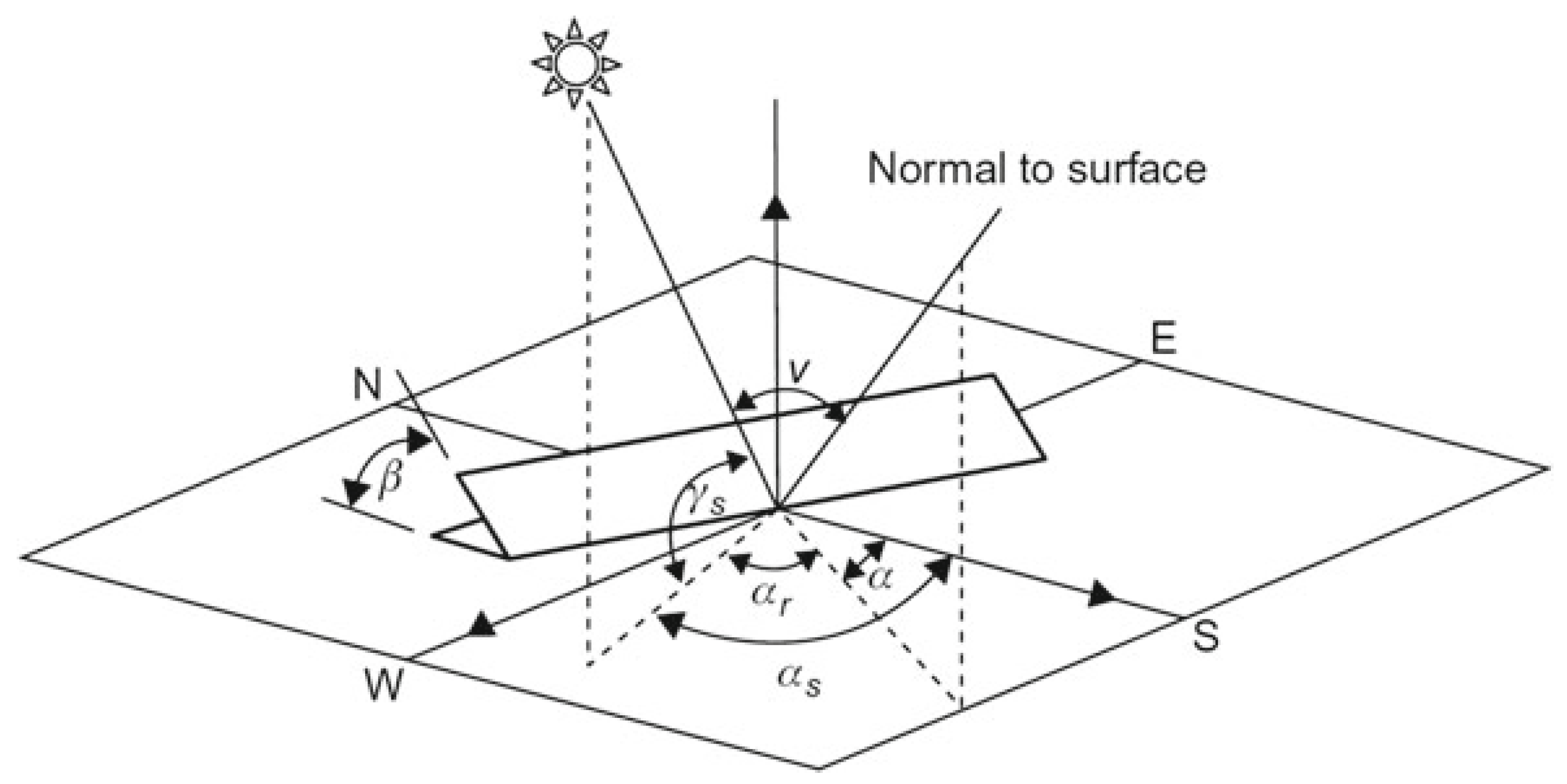

To represent the hourly behavior of demand, residential and commercial load profiles were simulated, as shown in

Figure 3, which depicts the typical variation in consumption throughout the day for each load type. From these profiles, additional curves were generated for the remaining system loads, with a random deviation of ±8 %.

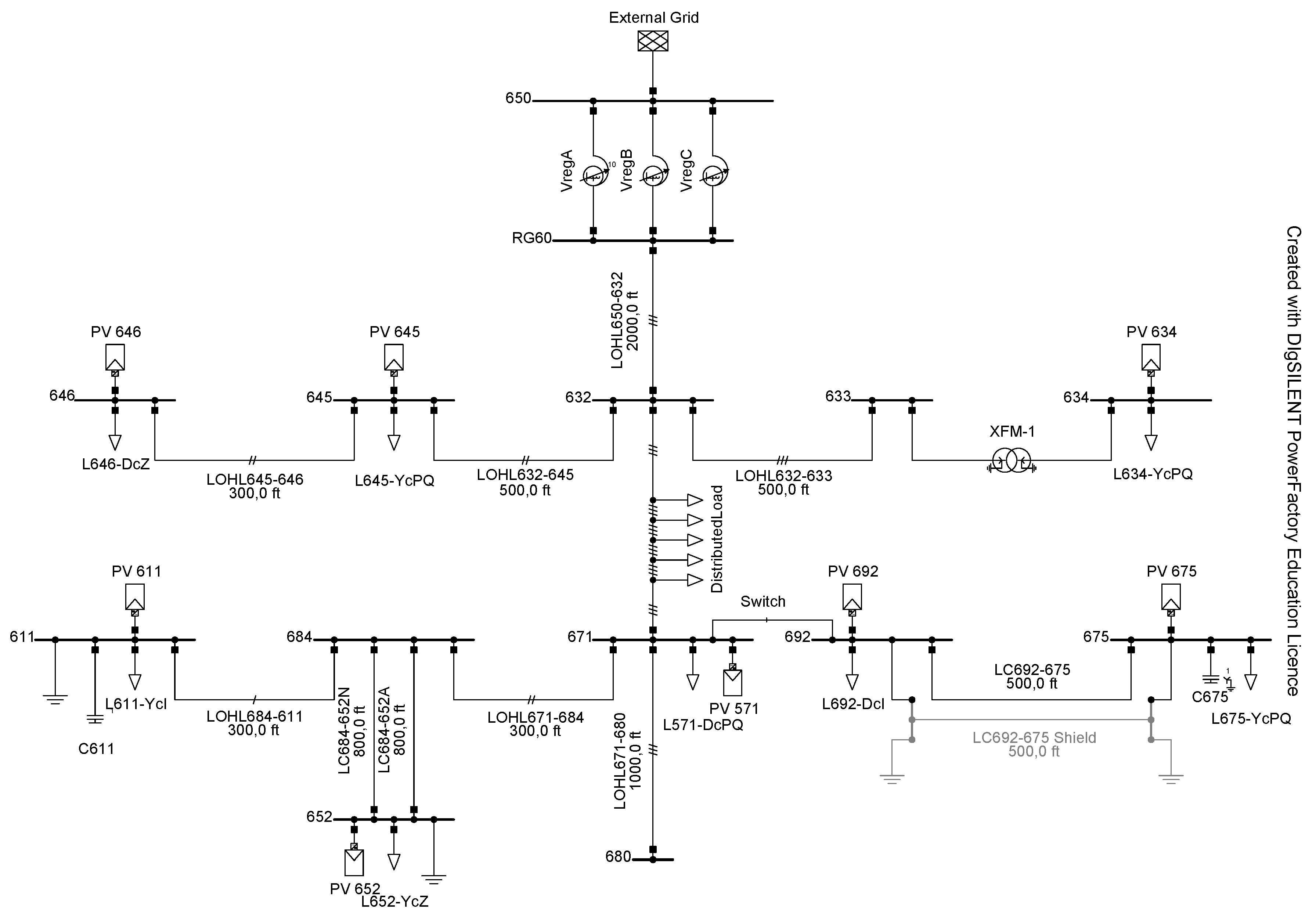

The model used for the simulations is the IEEE 13-node system, which is characterized by its radial configuration. The feeder consists of a set of elements that include 13 unbalanced loads and 10 sections, which combine overhead lines and underground cables in single, two, and three-phase configurations. Additionally, it features two capacitor banks, a transformer, and a per-phase voltage regulator. This system was modified to analyze the impact of PV generation. For this purpose, PV generation was incorporated into the load nodes [

32], as shown in

Figure 4.

The reactive power compensation of the two capacitor banks was modified from fixed to quasi-dynamic, i.e., it depends on the load connected to the node, as variations in demand can generate excess compensation. In this way, the compensation level is adjusted according to instantaneous demand. On the other hand, the loads located at nodes 611, 634, 645, 646, 652, and 692 were defined as residential loads, as were the distributed loads located between nodes 632-671. In contrast, the most significant loads at nodes 571 and 675 were classified as commercial loads based on their associated power.

Table 2 presents the active and reactive power values per phase for each load, and

Table 3 specifies the installed power of the photovoltaic generation systems to carry out the quasi-dynamic simulation.

4. Results and Discussions

This section presents a detailed analysis of the results from the quasi-dynamic simulations. The study was conducted on a computer with a 12th-generation Intel Core i5 processor, 8 GB of RAM, and a 64-bit version of Windows 10. In this environment, DIgSILENT PowerFactory version 2024 software was used, which includes a specialized photovoltaic model in which each unit represents a set of solar panels interconnected to the grid via a single inverter. This model distinguishes itself by automatically estimating the active power setpoint based on parameters such as geographic location, date, and local time.

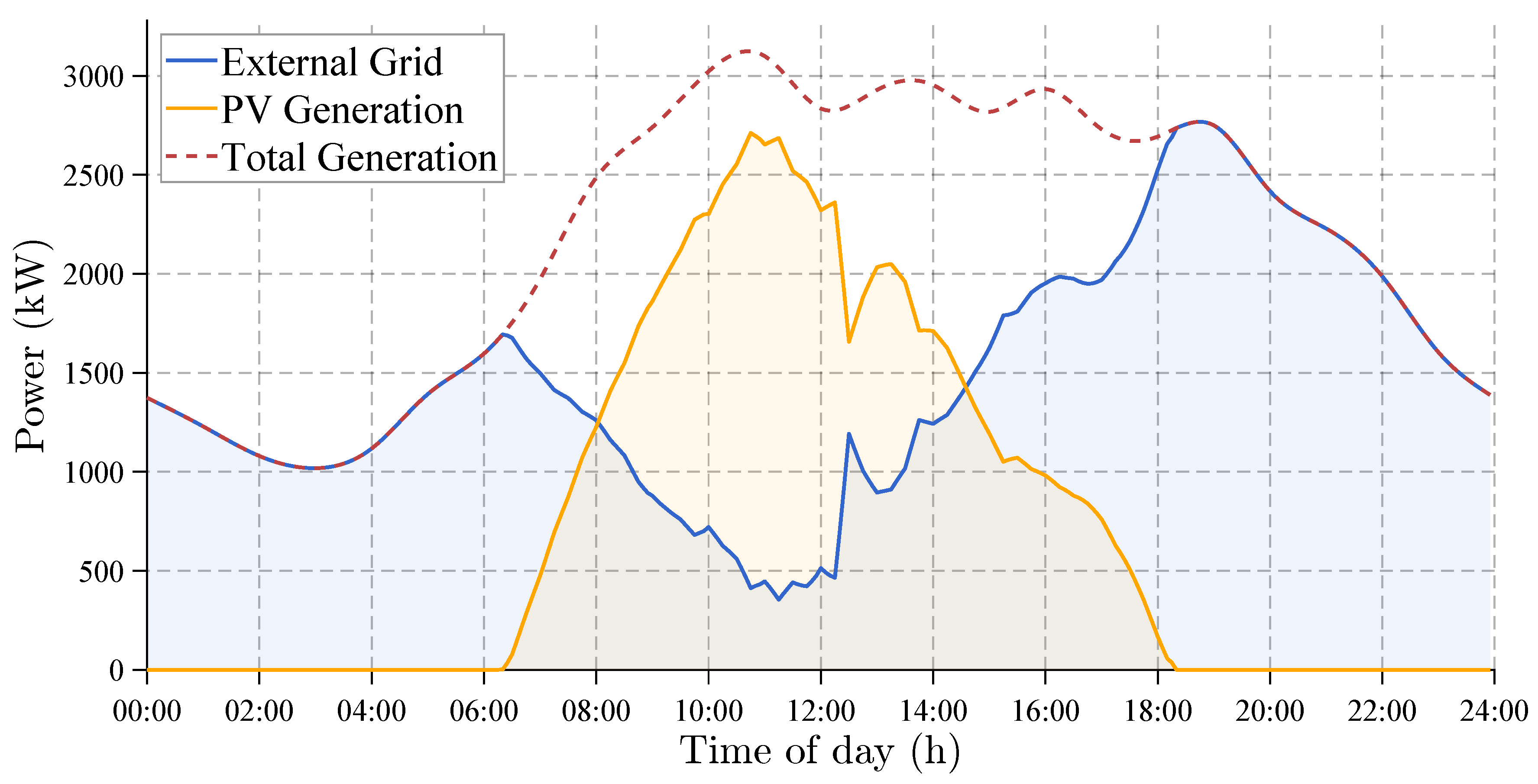

Figure 5 shows the hourly generation profile of the external grid in the presence of photovoltaic power injection over a typical day. It can be seen that the interval of highest solar irradiance occurs between 10:00 a.m. and 12:00 p.m. During this time, photovoltaic generation reached a maximum value of 2711 kW, representing approximately 86% of instantaneous demand. In terms of energy balance, the photovoltaic system achieved a total daily production of 17,626 kWh. In comparison, the total energy demand recorded was 55,720 kWh, indicating that PV generation accounted for 31.6% of the demand, a significant contribution to the system’s supply.

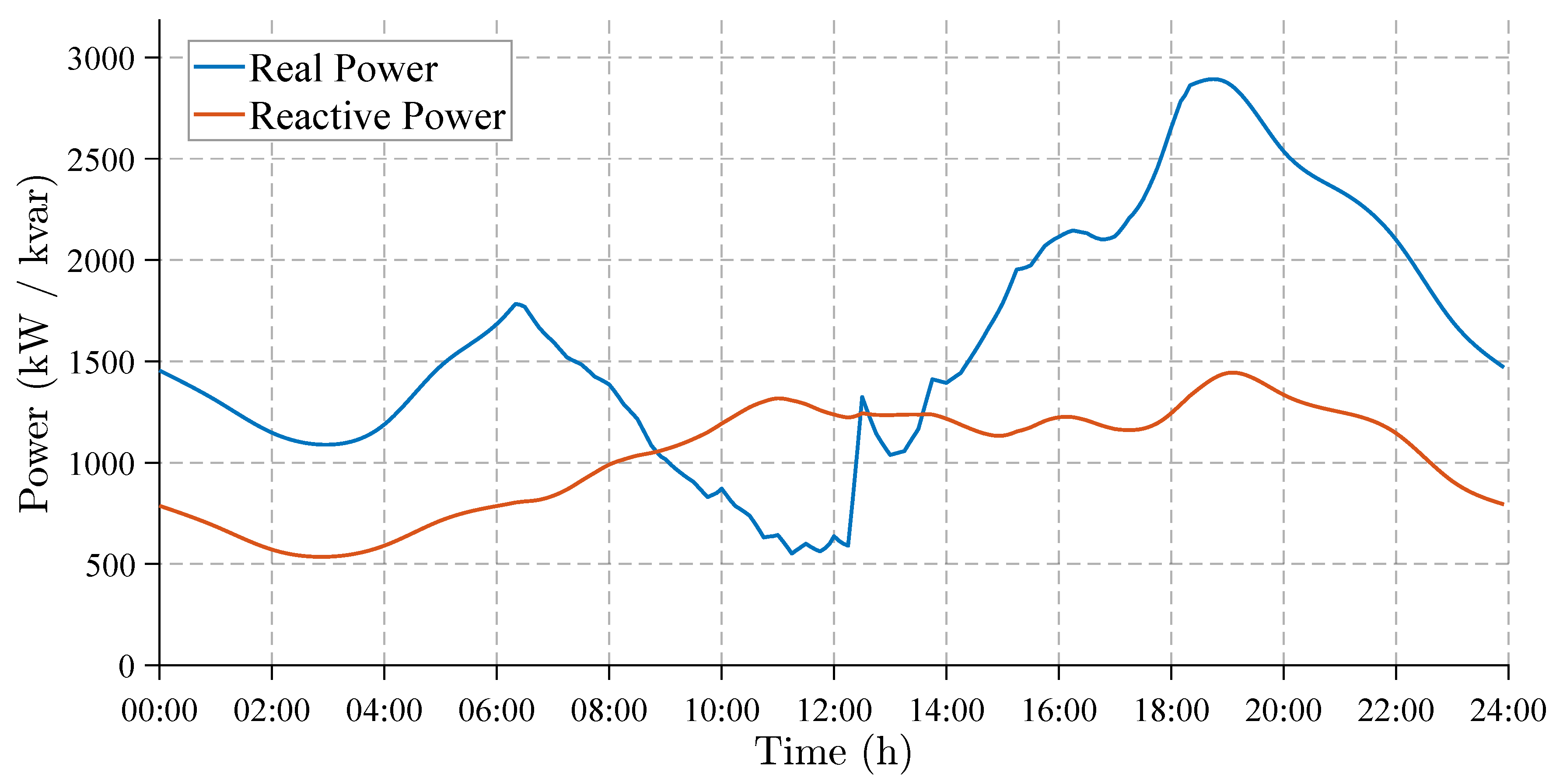

The daily profile of active and reactive power delivered by the external grid is shown in

Figure 6, which indicates a gradual reduction in active power between 8:00 a.m. and 3:00 p.m. due to the increased participation of photovoltaic generation during that interval. Furthermore, during the hours of highest irradiation, photovoltaic generation reduces the active power requirement from the grid, leading to reactive power demand exceeding active power demand.

4.1. Voltage Profile Analysis

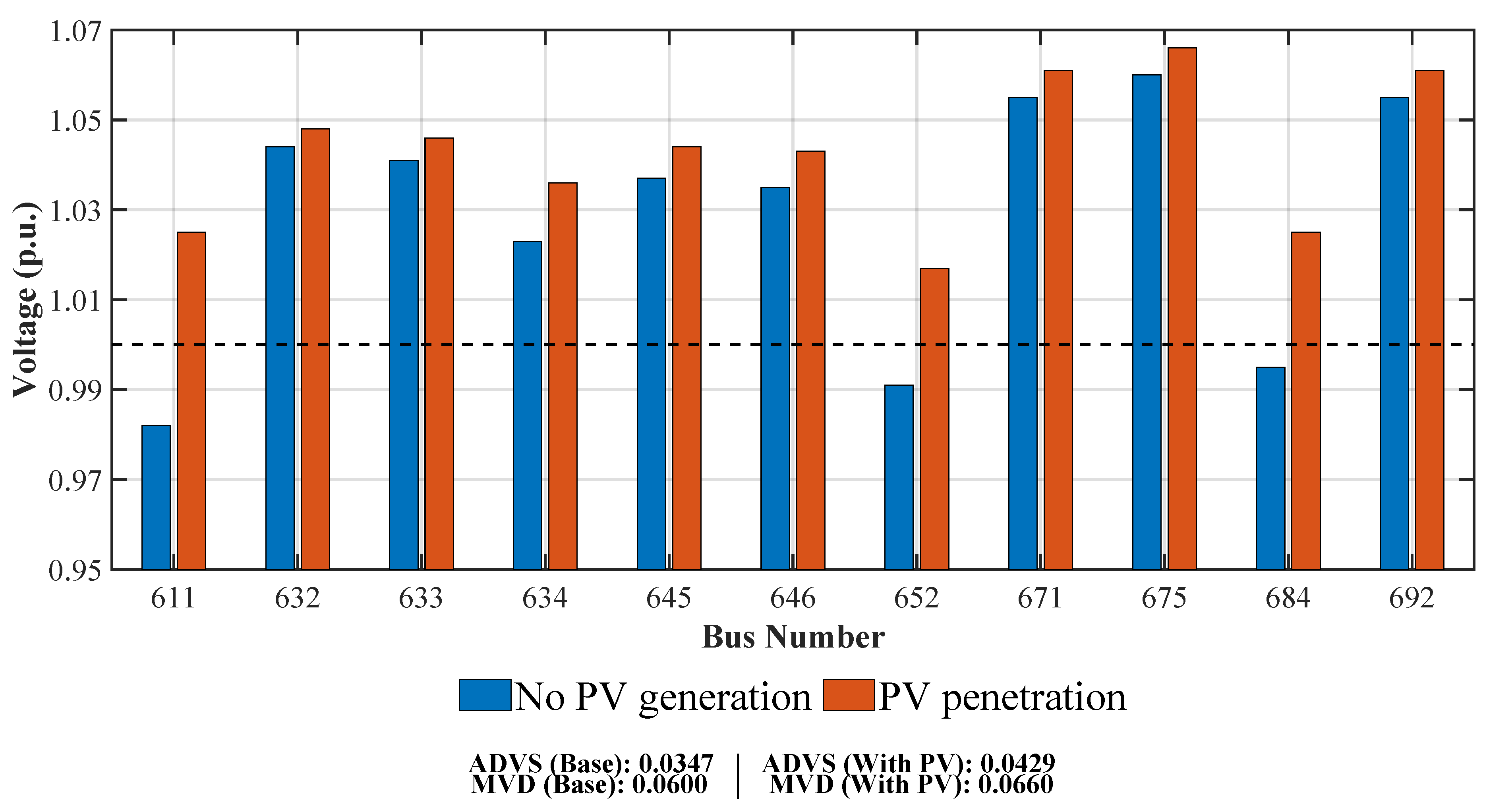

Figure 7 shows a comparison of the voltage magnitude at each node, with the phase having the highest magnitude at the point of maximum irradiance used as a reference. The location of the PV panels helps to reduce voltage drops in areas far from the main node (650), as seen in nodes 611 and 652, where voltage levels were initially below 0.98 and 0.99 p.u., and improved with PV integration. However, nodes 671, 675, and 692, which already had overvoltages, experienced further increases, reaching levels close to 1.07 p.u. In addition, nodes near the transformer (such as node 632) and those with low local demand (nodes 645 and 646) showed an increase in voltage close to the maximum threshold of 1.05 p.u., reaching the upper limit recommended by power quality standards.

The analysis of the voltage profiles is performed using equation (

6) to calculate the average voltage deviation throughout the system and equation (

7) to calculate the maximum voltage deviation [

33].

The results show that the ADVS in case 2 is close to 0.05 per unit during peak FV penetration. On the other hand, the MVD in bus 675 increases from 0.06 to 0.066 per unit, which is well above the recommended nominal value.

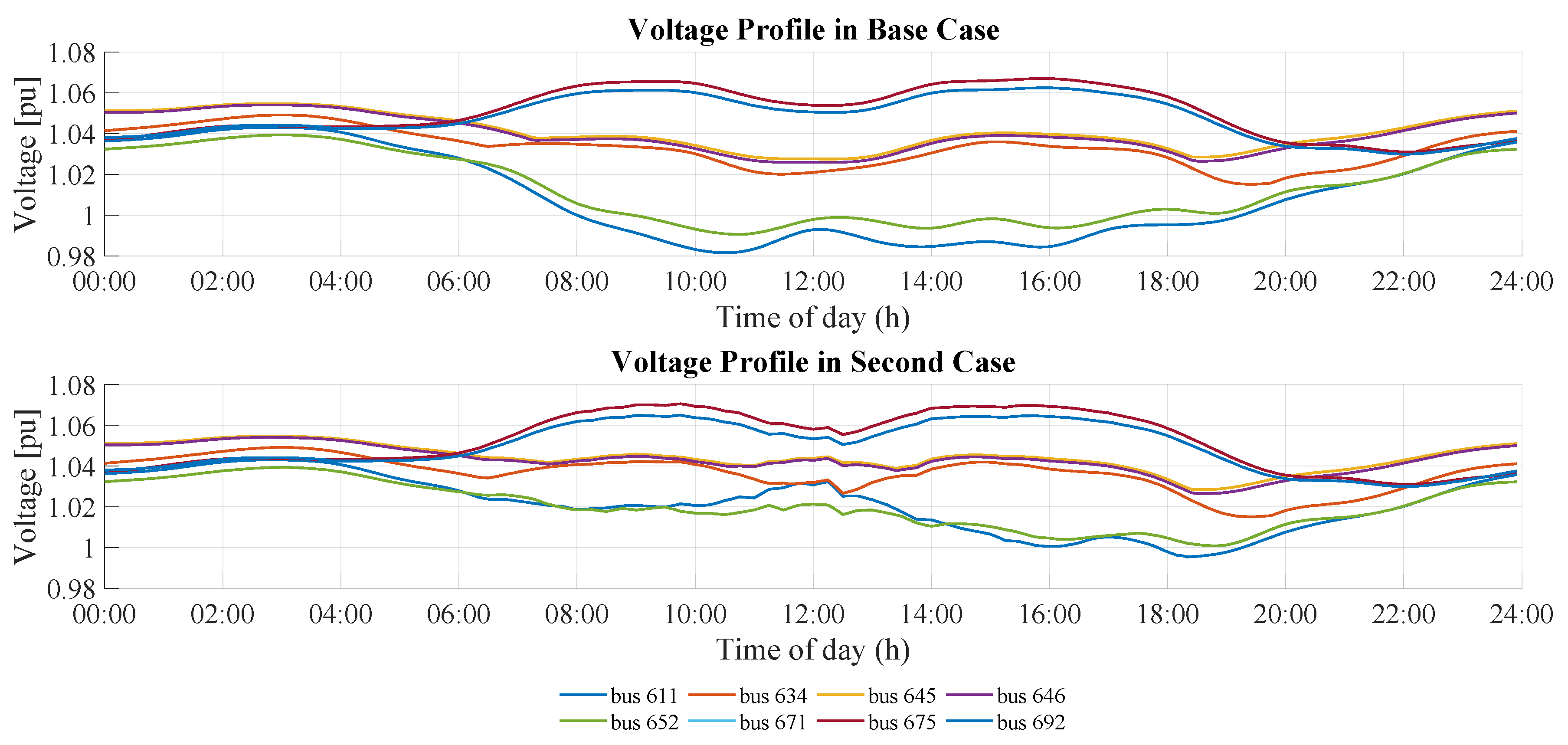

The daily profile for the base and PV injection scenarios is shown in

Figure 8, with a peak overvoltage around 9:00–11:00 a.m. and a trough at midday (minimum 0.98 p.u. in the initial case). However, in the second case, it increases significantly in nodes 611, 634, 646, and 675, reaching values of up to 1.07 per unit.

4.2. Voltage Imbalance

According to IEEE 1159-2019, a system is considered within acceptable limits when the voltage imbalance is less than 3%. Values above these thresholds can cause motors to overheat, reducing the equipment’s service life.

The percentage of voltage imbalance is calculated using the positive and negative sequence components according to Equation (

8), which allows the degree of asymmetry in the three-phase system to be quantified for evaluating electrical power quality [

34,

35].

Where and correspond to the negative and positive sequence components of the voltage on bus k, respectively.

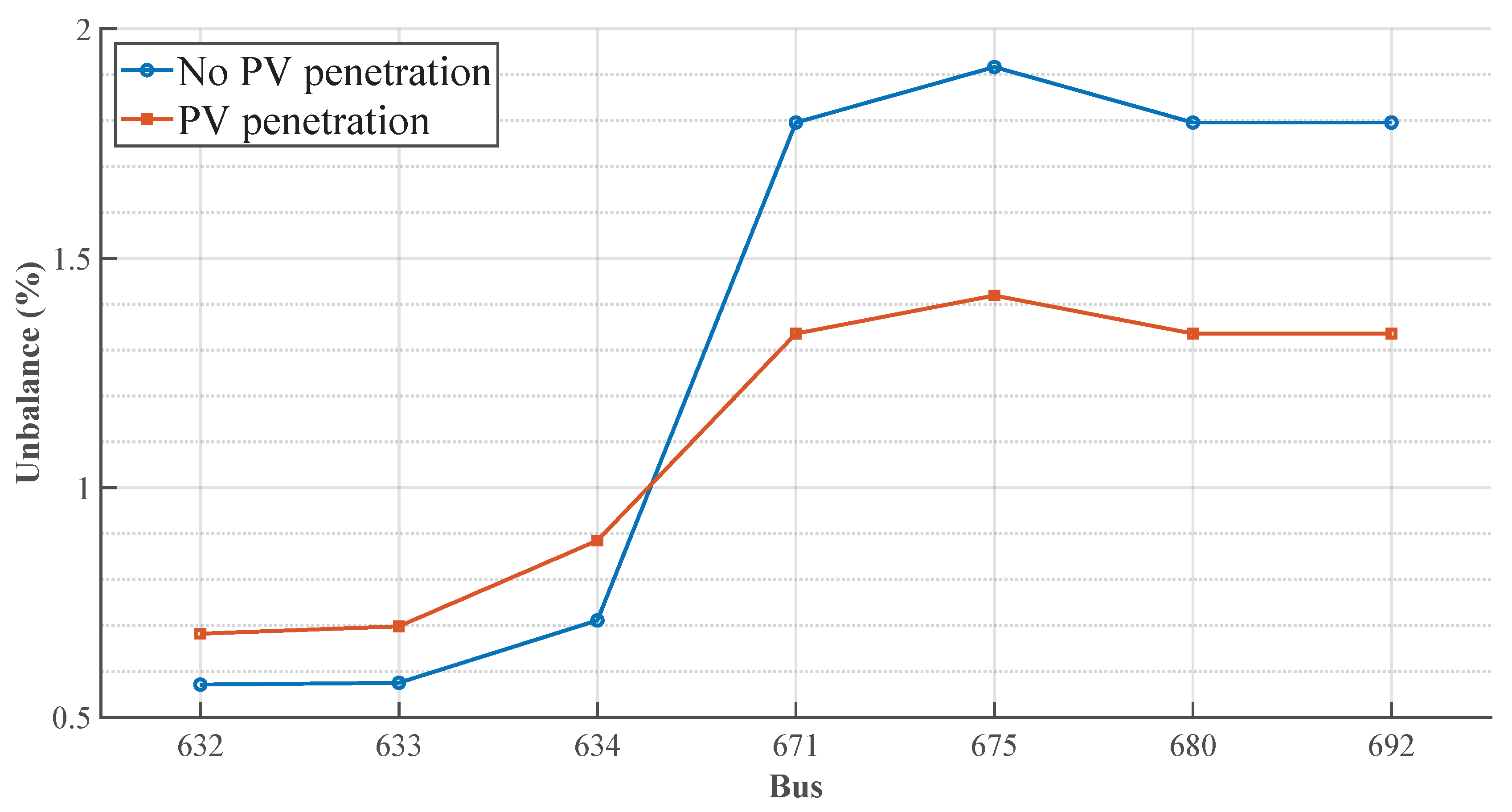

Figure 9 shows the behavior of voltage imbalance during maximum irradiance, both in the base case and in the PV penetration case. Nodes 632 and 633 initially record imbalance values of approximately 0.6%, whereas with PV generation, these increase to 0.72%. It should be noted that nodes such as node 634 are far from the reactive compensation zone, which is located at nodes 611 and 675.

Starting with bus 671, the imbalance initially reaches values close to the IEEE 1159-2019 reference limit. However, integrating PV generation reduced voltage imbalance, with improvements of up to 74% at nodes 671, 675, 680, and 692. This behavior indicates that PV generation improves voltage symmetry and reduces the presence of negative-sequence components. It is worth noting that the nodes not shown in the graph correspond to connection points with single-phase or two-phase loads, for which imbalance evaluation is not applicable.

4.3. Power Factor at the Nodes

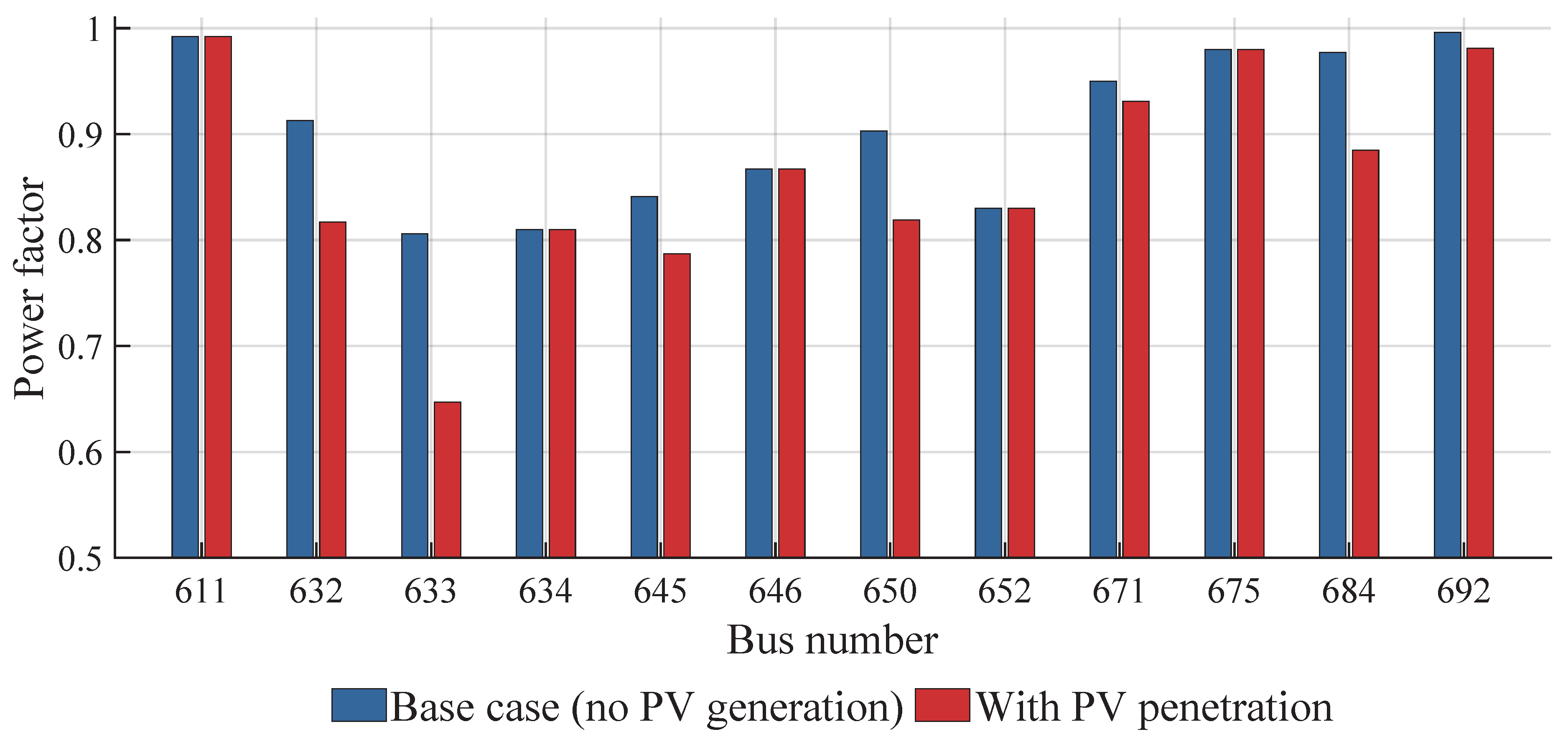

The power factor indicates the efficiency with which active power is used relative to the total power delivered.

Figure 10 shows the average PF values in the two scenarios, where the main node 650 has a PF of 0.903 p.u. in the initial case; however, during PV generation, this value is reduced to 0.819 per unit. This change is due to the decrease in the active component of the external source, resulting from the contribution of local generation, as reactive power is not compensated in the same proportion. Nodes 632, 633, and 684 are transfer nodes, which is why they have the lowest PF.

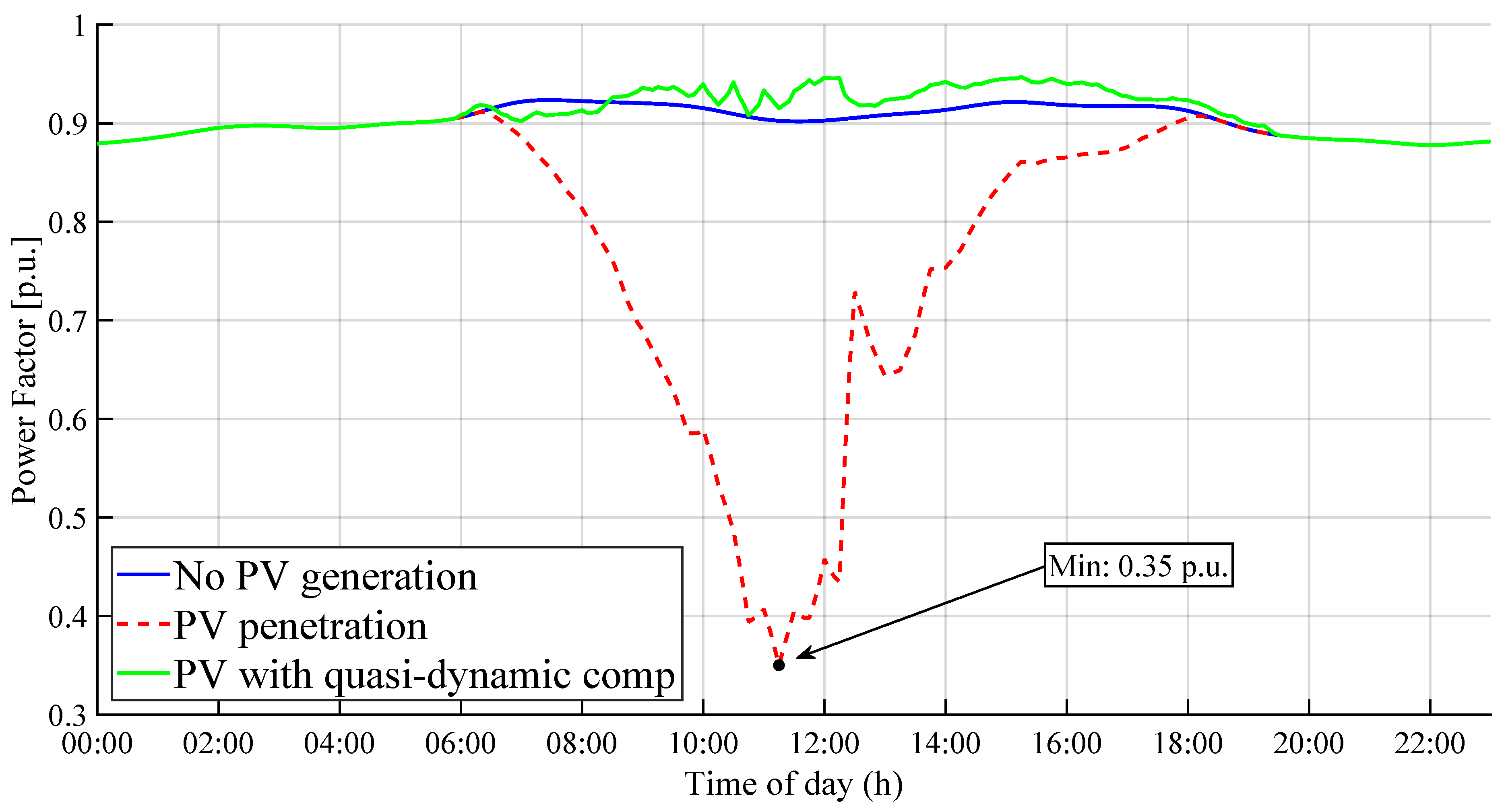

When performing an hourly analysis of the power factor at the main node, it is observed that the peak hours of PV generation (between 10:00 a.m. and 12:00 p.m.) coincide with a decrease in the power factor, reaching a minimum of 0.35 inductance. However, in Ecuador, Arconel Resolution 005/18 sets a minimum power factor of 0.92 for the primary grid. Therefore, to improve this condition, reactive power compensation is performed at the main node using a capacitor bank, adjusting the compensator tap in the quasi-dynamic simulation.

Figure 11 shows the behavior of the power factor throughout the day for the base case, solar generation, and reactive power compensation.

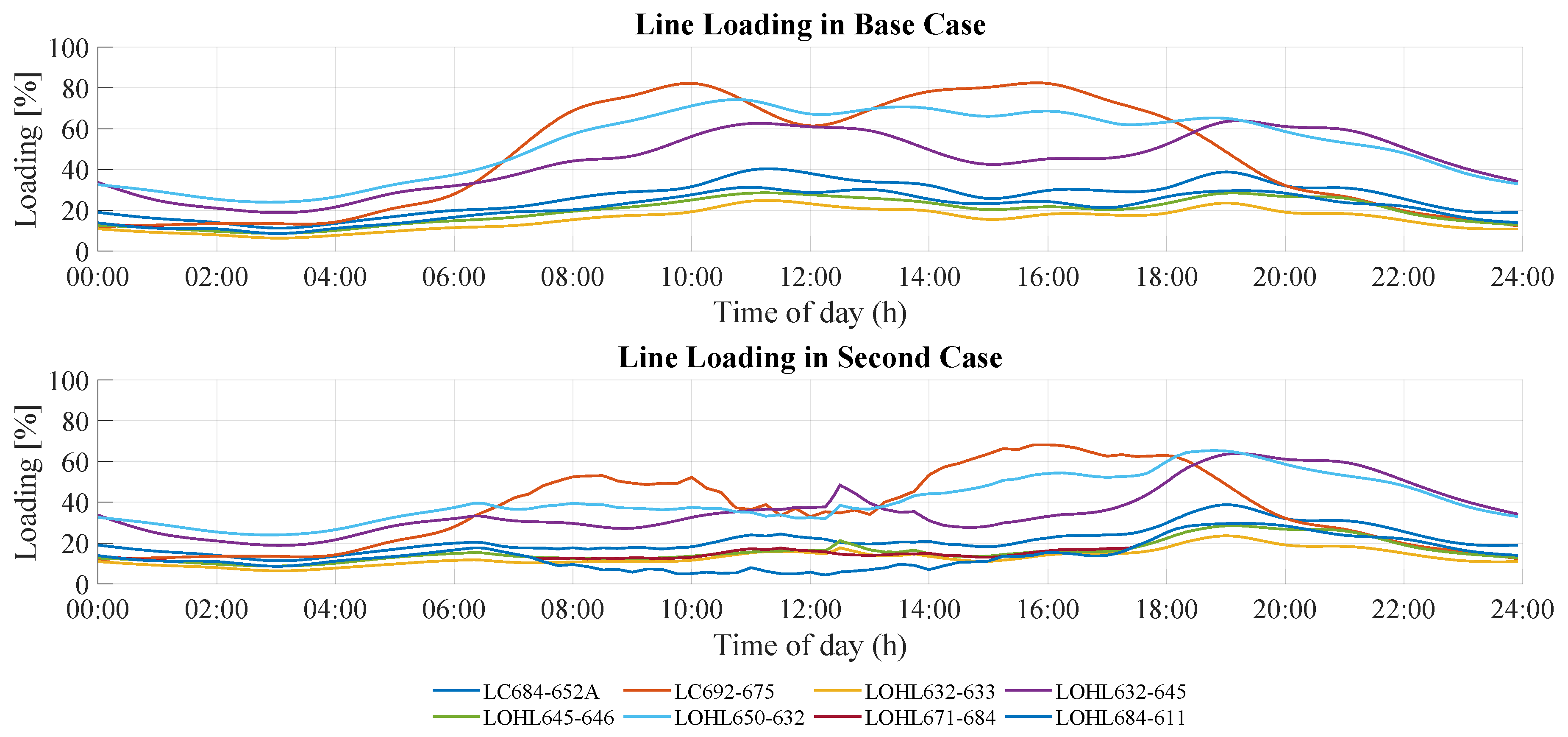

4.4. Line Loadability

Figure 12 shows the load capacity of the lines. With the integration of PV generation, there is an improvement in the loadability of the lines during the hours of highest PV injection, especially between 9:00 a.m. and 4:00 p.m., when, on several links such as 650-632, 692-675, and 632-645, the load capacity decreases by up to 60%.

5. Conclusions

The analysis reveals that the high penetration of photovoltaic power systems in distribution networks impacts the electrical grid in multiple ways. When solar energy penetration is low (in the morning and afternoon), the voltage profile improves. However, when certain integration levels are exceeded, the established voltage limits are not met (

Figure 8); likewise, it has been demonstrated that PV generation improves voltage symmetry, ensuring it remains within the limits recommended by IEEE 1559-2019. The deviation metrics (Ecs.

6,

7) indicate that the system voltage in general, both on average and in maximum deviation, tends to increase to values close to 0.05 p.u. (ADVS), and 0.066 p.u. (MDV), exceeding the threshold established by power quality standards such as IEEE 1159.

PV integration induces asymmetric impacts on voltage profiles during maximum irradiance (

Figure 7), reduces drops in distant nodes (611, 652), and generates overvoltages in nodes close to the capacitor banks (671, 675, 692), where levels of up to 1.07 p.u. were reached.

On the other hand, the fp in the main node (650) is reduced from 0.903 to 0.819 p.u. (

Figure 10), reaching minimums of 0.35 per unit during peak PV generation. This reduction exceeds the Ecuadorian regulatory limit specified in ARCONEL Resolution 005/18. It is attributed to the imbalance between the decrease in external active power and the increase in uncompensated reactive power. This problem is solved by installing a capacitor bank at the main node, which improves fp (

Figure 11) and keeps it within regulatory standards.

As for line load capacity, it is reduced by up to 60% on links 650-632, 692-675, and 632-645, helping decongest the grid and reduce energy losses.