1. Introduction

In Albania, electricity generation is predominantly derived from hydroelectric power plants located along the Drin River. Over the past decade, the country has seen the development of several small hydroelectric plants, collectively contributing a total capacity of approximately 600 MW [

1]. Consequently, electricity production is highly dependent on meteorological conditions, which can lead to fluctuations in supply. Furthermore, in recent years, the price of electricity has risen significantly, placing considerable strain on both household consumers and the industrial sector. In some cases, these price increases have led to the closure of production processes in certain industries, triggering broader economic repercussions. In response to these challenges, many consumers are turning to alternative electricity sources [

2,

3,

4].

As a result, there has been a shift toward renewable energy such as wind [

5,

6] and particularly solar power [

1]. Recently, several large-scale solar plants have been installed across Albania, contributing to the diversification of the energy mix. The benefits of solar power include ease of installation, minimal maintenance requirements, quick setup times, and environmental sustainability [

7,

8,

9]. The general types of PV solar panels that are commonly used in Albania include monocrystalline silicon (Mono-Si) panels, balck silicon (b/Si) panels, thin-film solar panels, bifacial solar panels, and building-integrated photovoltaics (BIPV) [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. Despite its favorable solar potential, Albania’s solar energy capacity remains modest compared to some of its regional neighbors. Countries like Kosovo, North Macedonia, and Serbia have made more significant strides in integrating solar power, driven by supportive policies and larger-scale projects [

15,

16]. Nevertheless, the deployment of solar power also presents challenges, such as the need for substantial land area and the fact that energy production is contingent upon sunlight availability. Given these considerations, it is essential to assess the impact of solar energy penetration on the power system in Albania. The increasing integration of renewable energy sources, particularly solar, has significant implications for the stability of electricity transmission [

17]. To enhance the integration of solar energy, it will be necessary to either build new or upgrade existing interconnection lines to increase export capacity. Additionally, to manage voltage levels at system nodes, solar plants must contribute in alignment with the transmission code, which may include the installation of reactors at critical nodes. The use of energy storage technologies will also play a crucial role in balancing grid supply and demand, as variations in solar generation can be mitigated by storing excess energy in batteries for later use [

18,

19,

20].

Based on highest levels of solar radiation in the country, “Fieri” region in Albania is indeed a very promising location for the installation of photovoltaic (PV) solar plants due to a combination of favorable environmental, logistical, and economic factors [

21]. This paper examines the influence of solar power plants in the “Fieri” region on the operation of the national power system. Based on it, four distinct scenarios have been considered, and several technical parameters related to electrical power quality are analyzed to determine the impact of solar energy integration. Initially, we assess voltage levels at key nodes and power losses in the transmission lines under steady-state conditions. Simulations are conducted using ETAP software to model the effects of solar energy penetration. The results suggest that the level of solar energy penetration directly affects both voltage stability and power losses within the transmission system. In particular, high levels of solar energy can challenge the system’s ability to meet the (N-1) reliability criterion [

22]. This issue arises from the existing network’s inability to accommodate the significant energy output from the solar plants in the “Fieri” region, which can lead to system instability. To mitigate these challenges, large-capacity battery storage systems could be installed at solar plants to stabilize the power grid [

23,

24,

25]. This approach represents a balanced scenario, reflecting a compromise between more conservative and optimistic forecasts.

2. The Current Landscape of Solar Energy Development in Albania

Solar energy is a very promising energy source for the future and its use is potential as it is an inexhaustible natural source of energy, it is the largest natural reserve of energy that is distributed everywhere in the world in large quantities, it is clean and its use does not require any other costs [

7]. It does not cause any risk of environmental pollution.

Table 1 presents data on electricity production for all categories of producers operating in Albania during 2023 [

1].

As shown in

Table 1, the main contributor to energy production during 2023 is by KESH sh.a, a public company.

Table 2 depict the annual radiation per day in most important regions in the republic of Albania.

In 2023, the total annual energy production from solar plants in Albania reached 80,874 MWh, accounting for approximately 1% of the country’s total energy production from generating units. Albania, benefiting from its favorable geographical location in the Mediterranean basin, enjoys optimal climatic conditions for harnessing solar radiation for electricity generation. The intensity and duration of solar radiation, along with factors such as air temperature and humidity, contribute significantly to the country’s solar energy potential.

Table 3 presents a selection of solar plants with substantial installed capacity commissioned in 2023.

Albania is situated in the western part of the Balkan Peninsula, along the eastern coasts of the Adriatic and Ionian Seas. The country lies between latitudes 39°38’ and 42°38’ and longitudes 19°16’ and 21°04’. Albania has significant solar energy potential, with regions across the country receiving solar radiation ranging from 1,185 kWh/m2 per year to 1,700 kWh/m2 per year. Notably, the western and southwestern parts of Albania receive even higher levels of solar radiation, reaching up to 2,200 kWh/m2 per year. In these regions, each square meter of horizontal surface can receive up to 2,200 kWh per year, with an average of approximately 1,700 kWh per year under typical weather conditions.

Table 2 presents the average solar energy production capacity across several regions of Albania throughout the year. Data from the Tirana and “Fieri” districts, where industrial activity is concentrated, show higher daily solar energy generation compared to other regions.

Table 3 further illustrates the expected expansion of energy sources, highlighting a significant number of new installations set to be connected to the transmission system. This anticipated growth underscores the need for dynamic development and increased investment to integrate these renewable energy sources into Albania’s electricity grid in the coming years.

3. Data on Solar Plants Installed in the Electric Power System in Fieri Region

As discussed in the previous section, several solar plants with significant capacity have been developed in Albania. This paper focuses on the solar plants built in the “Fieri” region. The total installed capacity of solar plants in this region is 1,390 MWp.

Table 4 presents a list of the solar plants installed in the “Fieri” area. The inverter groups are connected to the low-voltage side of the power transformer, operating at a voltage of 400 V. The high-voltage windings of the transformer are connected in parallel and linked to the substation via a 20 kV line.

To integrate these solar systems into the electrical grid, a dedicated electrical substation has been constructed in the “Fieri” region. This substation houses three transformers, each with a rated power of 200 MVA. The substation is connected to the national grid through a 220 kV transmission line.

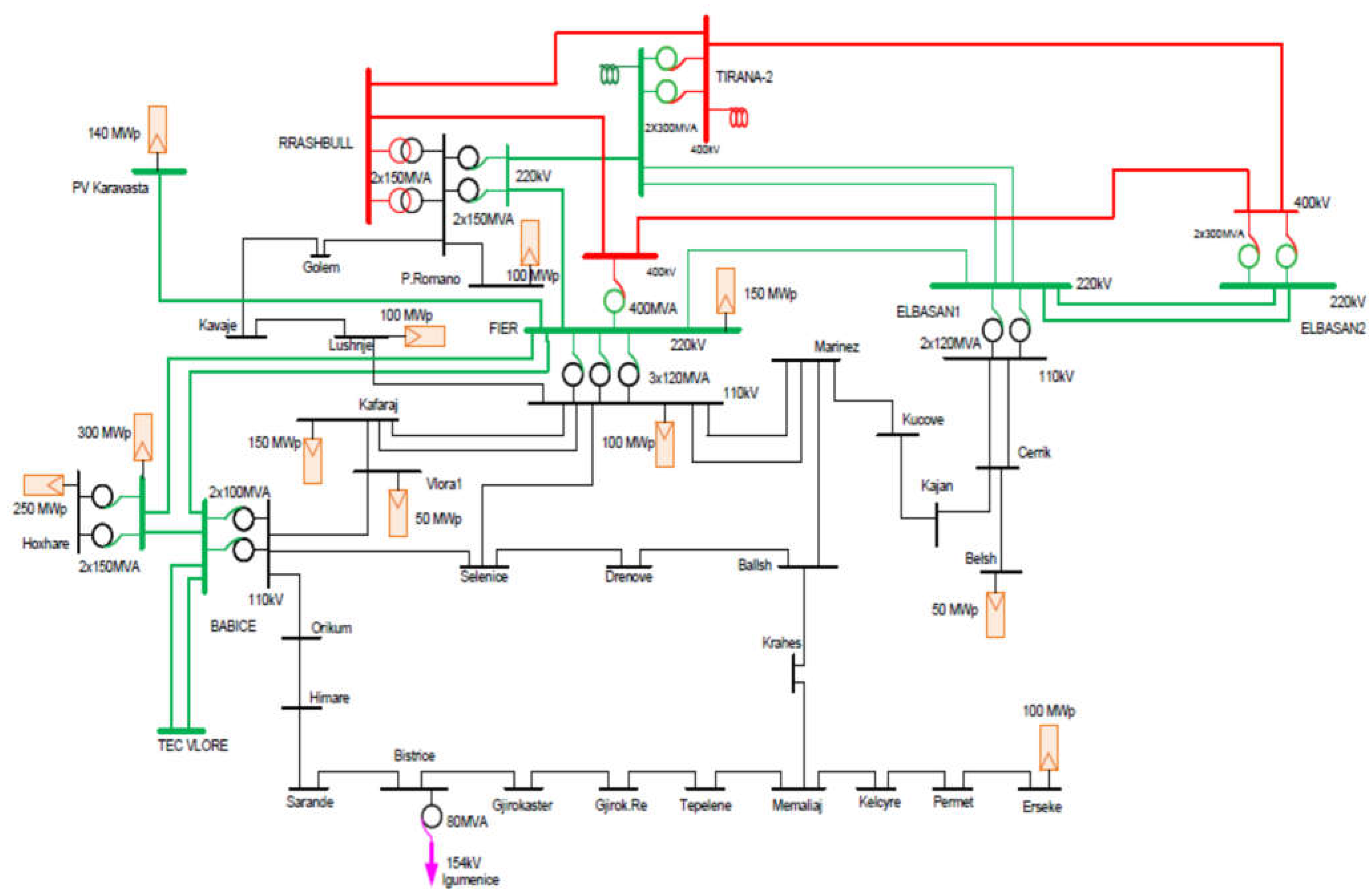

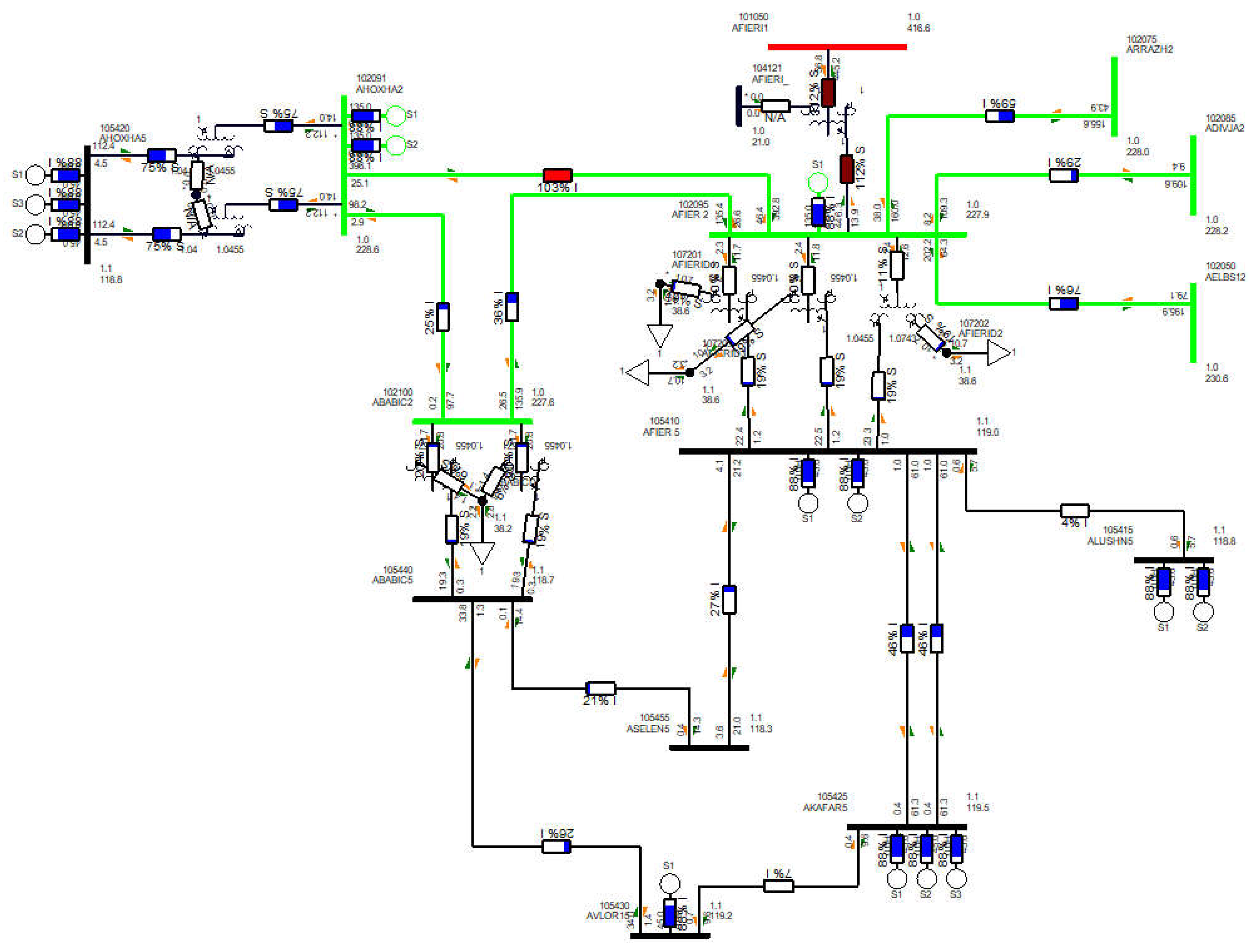

Figure 1 illustrates the single-line diagram showing the connection of the solar plants to the electrical power system.

4. Analysis of the Power System During Energy Penetration from Solar Power Plant Production

In this section, we analyze the electrical system of the Fier region, focusing on the integration of solar plants into the grid. As highlighted in previous sections, the network analysis for the “Fieri” region is particularly relevant due to the concentration of solar plants in this area. The findings from this analysis may also be applicable to other regions with a high concentration of solar energy resources.

In this study, we adopt a conservative approach to the development of solar resources by considering a scenario where 50% of the planned solar capacity is installed and commissioned in the “Fieri” region. Two primary cases are analyzed for the solar system in the “Fieri” region: In the first case, we evaluate the energy penetration from solar plants at 50% of their installed capacity. In the second case, we consider the full penetration of energy produced by solar plants at their maximum installed capacity.

In both cases, the power system load is assumed to be at its maximum value as well as at 70% of the maximum load.

The analyzed scenarios are as follows:

Scenario 1 – 50% of solar plant capacity, system load at 70% of maximum value.

Scenario 2 – 50% of solar plant capacity, system load at maximum value.

Scenario 3 – 100% of solar plant capacity, system load at 70% of maximum value

Scenario 4 – 100% of solar plant capacity, system load at maximum value.

For each scenario, we will analyze the following parameters: power flows, load levels on transmission lines and transformers, voltage profiles at system nodes, active power losses in the system, and compliance with the N-1 security criterion.

4.1. Scenario 1 – 50% of Solar Plant Capacity, System Load at 70% of Maximum Value

In this scenario, the transmission lines are underloaded, with transmission line losses amounting to approximately 37.4 MW.

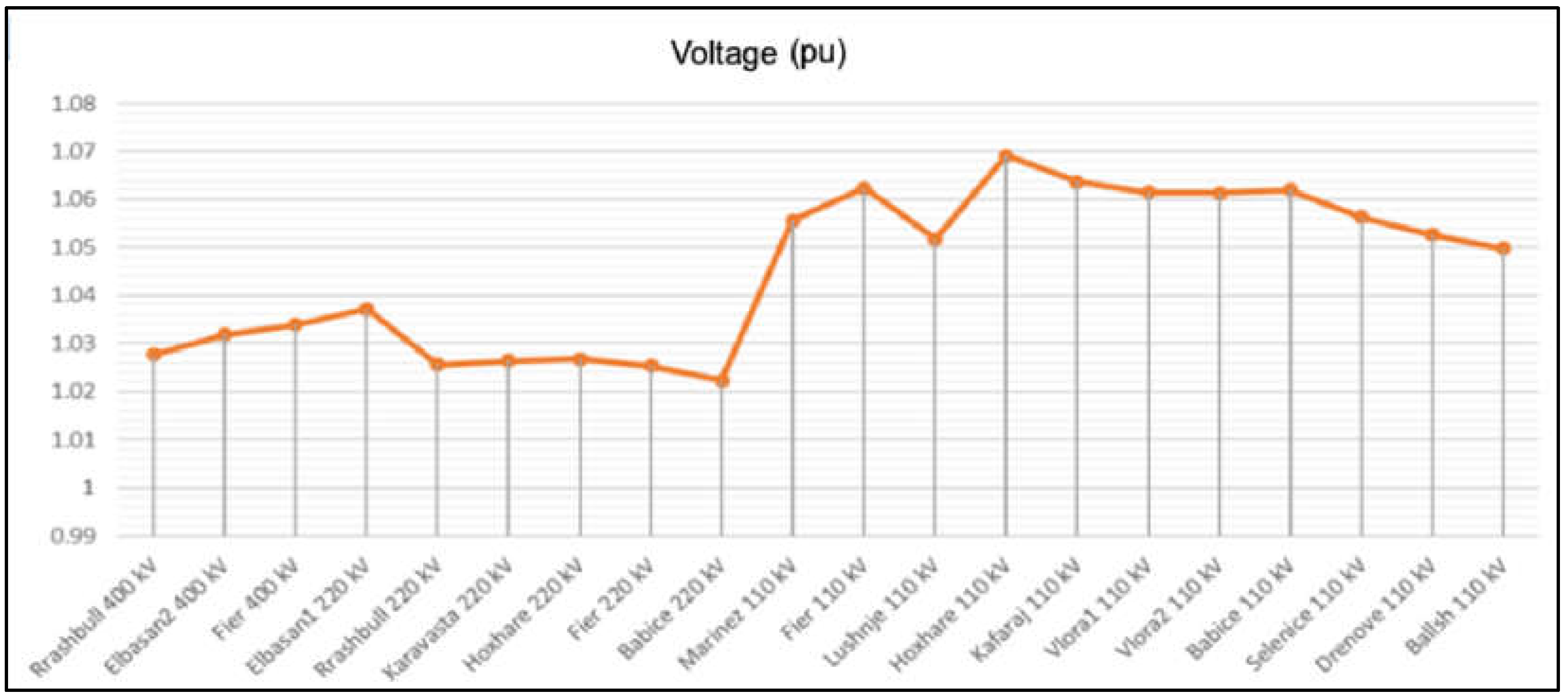

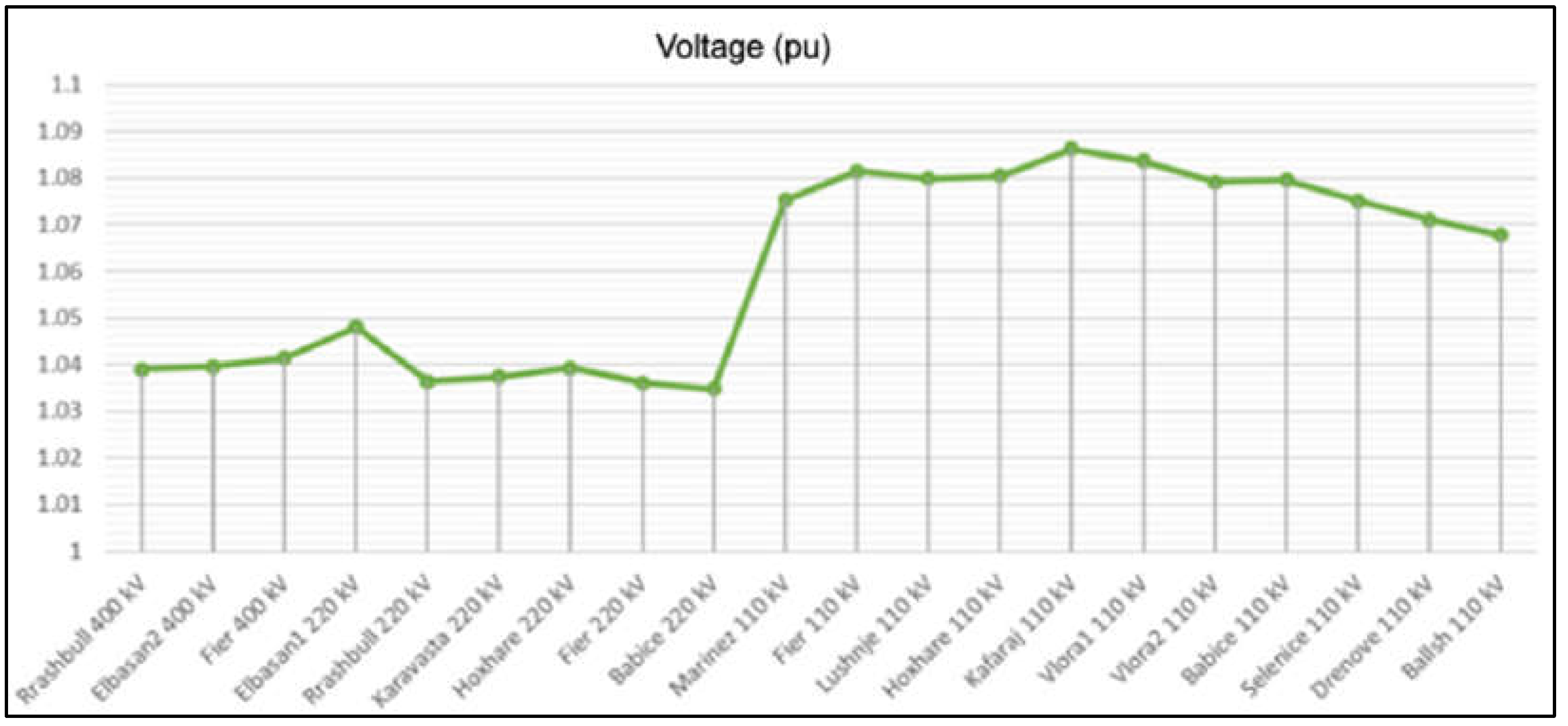

Figure 1 illustrates the voltage profile across the transmission lines in the “Fieri” region, as observed in Scenario 1. The simulation data from the “Hoxhare” node reveals that the voltage level is 7% above the nominal value. The electrical network in the “Fieri” region, under these conditions, complies with the N-1 security criterion. It is important to note that if one of the autotransformers at the “Hoxhare” substation is disconnected, the remaining autotransformer operates at approximately 91% of its capacity. Overall, the penetration of energy from 50% of the solar power plants in the “Fieri” region does not pose any significant issues for the stability or operation of the electrical system.

Figure 2.

Voltage profile of transmission lines in the “Fieri” region according to scenario 1.

Figure 2.

Voltage profile of transmission lines in the “Fieri” region according to scenario 1.

4.2. Scenario 2 – 50% of Solar Plant Capacity, System Load at Maximum Value

In this regime, all transmission lines are underloaded, and the Albanian power system operates in export mode. The total power losses in this scenario are approximately 31.7 MW.

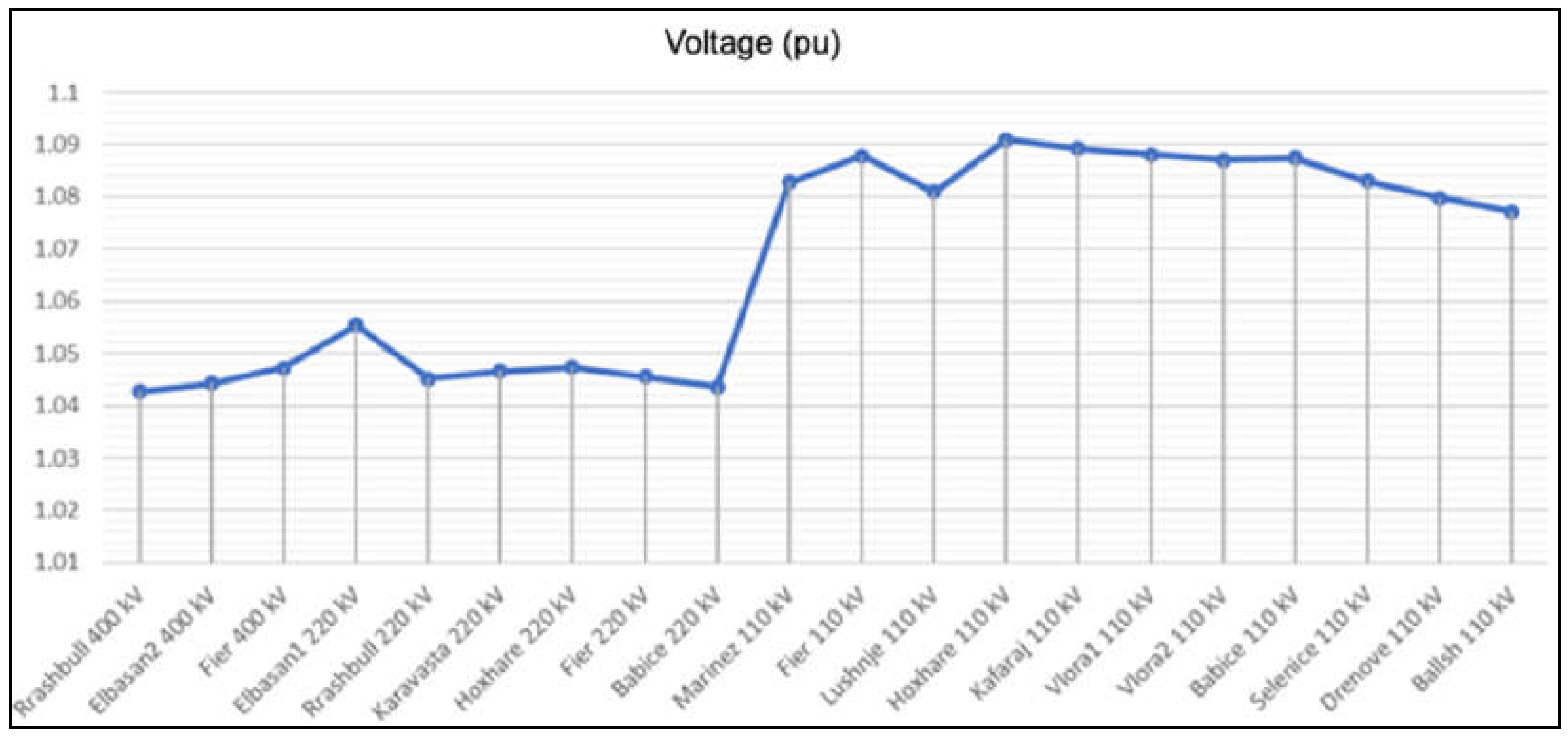

Figure 3 illustrates the voltage profile across the transmission lines in the “Fieri” region, as observed in Scenario 2.

The simulation data indicates that the voltage at the “Hoxhare” node reaches its highest level, 9% above the nominal value. The electrical power system in the “Fieri” region, under these conditions, complies with the N-1 security criterion. It is important to note that if one of the autotransformers at the “Hoxhare” substation is disconnected, the remaining autotransformer operates at approximately 91% of its capacity. In conclusion, the penetration of energy produced by solar plants, with 50% of the installed capacity in the “Fieri” region and a system load at 70% of its maximum value, does not present any issues for the stability of the electrical system.

4.3. Scenario 3 – 100% of Solar Plant Capacity, System Load at 70% of Maximum Value

This regime is characterized by a high penetration of energy production from solar power plants. In this scenario, the energy generated by the power plants not only meets domestic demand but also results in surplus production, with approximately 500 MW exported to the regional energy system. The 400/220 kV autotransformers at the “Fieri” substation and the 220 kV “Fieri – Hoxhare” transmission line experience slight overloading. In this regime, the active power losses in the system amount to approximately 56.5 MW.

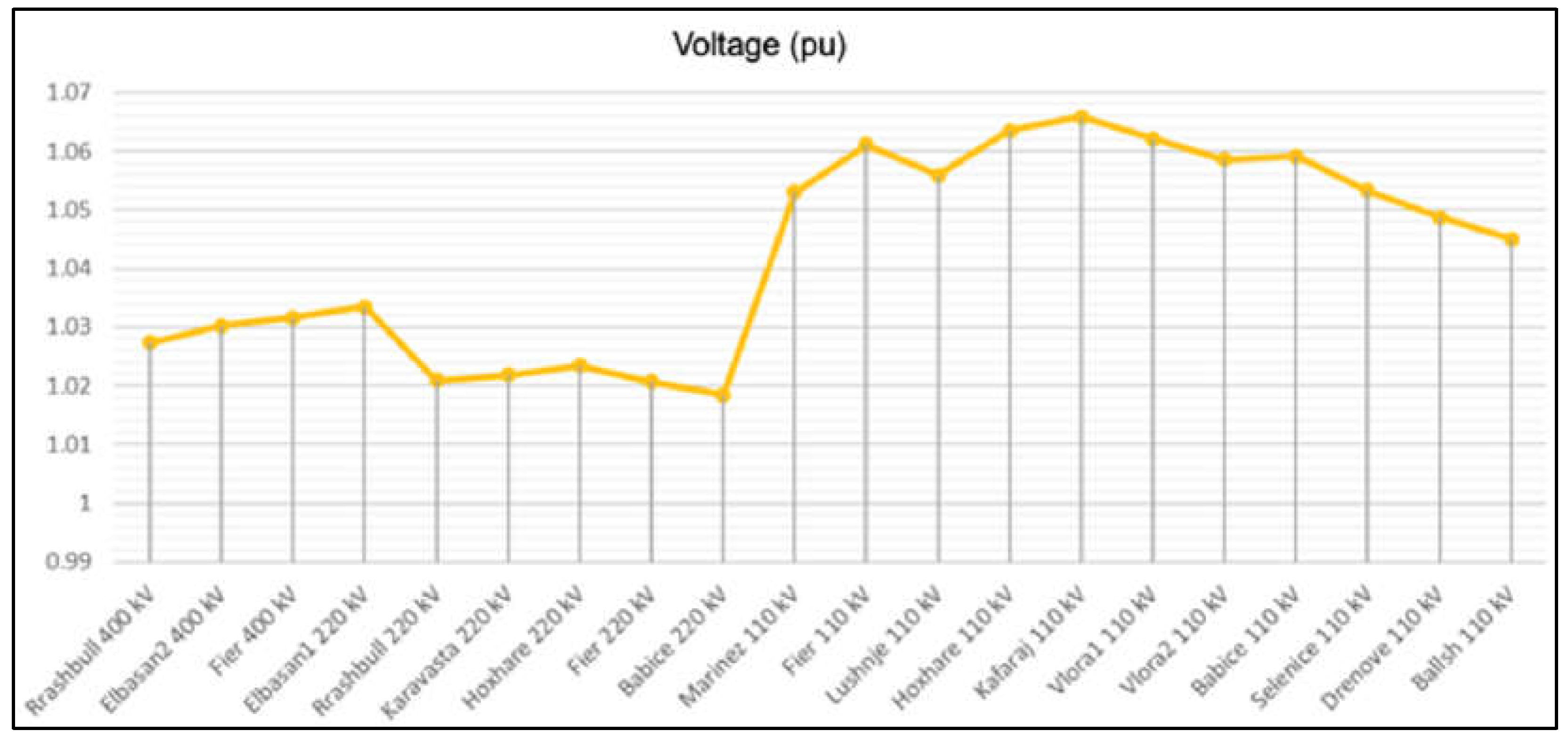

Figure 4 illustrates the voltage profile across the transmission lines in the “Fieri” region, as observed in Scenario 3.

4.4. Scenario 4 – 100% of Solar Plant Capacity, System Load at Maximum Value

This regime is also characterized by a high level of energy generation.

Figure 5 illustrates the distribution of power flows across the transmission lines. In this scenario, the Albanian power system operates in export mode, with a power export of 900 MW. As shown in

Figure 3, the 400/220 kV autotransformer at the “Fieri” substation and the 220 kV “Fieri – Hoxhare” transmission line are slightly overloaded, operating at 105-110% of their capacity.

In this regime, the active power losses in the system are approximately 55.9 MW.

Figure 6 depicts the voltage profile across the transmission lines in the “Fieri” region, as observed in Scenario 4. Simulation data from the “Kafaraj” node indicates that the highest voltage level reaches 8.5% above the nominal value.

Under these conditions, the electrical network in the “Fieri” region does not comply with the N-1 security criterion. Both the transmission line and the 400/220 kV autotransformer are overloaded. In some cases, if the 220 kV line in the region is disconnected, the overload on system components can rise to 140%. Additionally, a failure of the 400/220 kV autotransformer at the “Fieri” substation results in the overloading of the 220 kV transmission lines in the region.

5. Summary and Conclusions

The production of electricity using solar energy has significantly improved the efficient use of water resources in Albania. Additionally, the installation of solar power plants has reduced the country’s dependence on electricity imports from outside the region. Solar plants, as renewable energy sources, offer several advantages, including: the abundance and inexhaustibility of solar energy, its non-polluting nature, and the fact that it does not emit greenhouse gases or harmful waste. Furthermore, due to their simple construction and low maintenance costs, solar panels are primarily used for electricity generation.

However, the high penetration of solar energy into the grid presents certain challenges. These include increased system losses, high voltage levels (approaching maximum values at certain nodes), and the failure to meet the N-1 security criterion for system operation. These issues stem from the existing grid infrastructure, which is not designed to accommodate the substantial energy input from solar plants in the Fier region.

To improve the integration of solar energy into the electrical system, the following measures should be considered:

Strengthening interconnection lines: Given that the load on the electrical system is expected to increase moderately based on statistical data, simply absorbing additional generation from solar plants is insufficient. Enhancing interconnection lines will be necessary to export the excess energy produced.

Managing voltage levels: In addition to installing reactors at key nodes in the electrical system, solar plants should contribute to voltage regulation in accordance with the transmission code to ensure system stability.

Involving private sector investments: Increasing transmission capacities in specific regions with high solar resource potential, through private sector involvement, will be crucial for enhancing the grid’s ability to accommodate solar energy generation.

Upgrading transformer capacity: Static analysis of the electrical network in scenarios with significant solar penetration indicates a need to increase transformer capacities at local substations. Moreover, the creation of a new transformation node at the 400 kV level may also be required to support the increased generation.

Energy storage systems: Balancing grid supply and demand can be achieved through the use of energy storage technologies. Excess solar energy can be stored in batteries during periods of high generation and utilized when needed to smooth out fluctuations in power supply.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, all authors; methodology, all authors; validation, A.B. and A.E.; investigation, K.D.; data curation, B.L.; writing—original draft preparation, A.B. and K.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Polytechnic University of Tirana, Albania.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Author Energy Regulator Authority, Annual Report 2023. Available online: https://www.ere.gov.al/en/publications/annual-reports/annual-report-2023 (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Solar Power Europe. Global Solar Energy Market Outlook, 2017-2021. Available online: https://resources.solarbusinesshub.com/solar-industry-reports/item/global-market-outlook-2017-2021 (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Fuchs, A.; Lohmann, A.; Gebremedhin, A. Transitioning Towards a Sustainable Energy System: A Case Study of Baden-Württemberg. International Journal of Innovative Technology and Interdisciplinary Sciences 2024, 7, 157–197. [Google Scholar]

- Sara, E. , Vijay V., Gerald H., Brian K., Jeffrey L. Impact of Increasing Penetration of Solar Generation on Power Systems. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2013, 28, 893–901. [Google Scholar]

- Dhoska, K.; Bebi, E.; Markja, I.; Milo, P.; Sita, E.; Qosja, S. Modelling the wind potential energy for metallurgical sector in Albania. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baballëku, M.; Verzivolli, A.; Luka, R.; Zgjanolli, R. Fundamental Basic Wind Speed in Albania: An Adoption in Accordance with Eurocodes. Journal of Transactions in Systems Engineering 2023, 1, 56–72. [Google Scholar]

- Alirezaei, M.; Noori, M.; Tatari, O. Achieving the net zero energy building: Investigating the role of home automation technology. Energy and Buildings 2016, 130, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltawil, M.A.; Zhao, Z. Grid-connected photovoltaic power systems: Technical and potential problems-A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2010, 14, 112–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benöhr, M.; Gebremedhin, A. Photovoltaic systems for road networks. International Journal of Innovative Technology and Interdisciplinary Sciences 2021, 4, 672–684. [Google Scholar]

- Nazir, G.; Rehman, A.; Hussain, S.; Aftab, S.; Patil, S.A.; Aslam, M.; Hafez, A.A.A.; Kwang, H. Bifacial perovskite thin film solar cells: Pioneering the next frontier in solar energy. Nano Energy 2025, 134, 110523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhoska, K.; Spaho, E; Sinani, U. Fabrication of Black Silicon Antireflection Coatings to Enhance Light Harvesting in Photovoltaics. Eng. 2024, 5, 3358–3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumba, K.; Upender, P.; Buduma, P.; Sarkar, M.; Simon, S.P.; Gundu, V. Solar tracking systems: Advancements, challenges, and future directions: A review. Energy Reports 2024, 12, 3566–3583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosal, S.; De, D.; Kar Ray, D.; Roy, T. Condition Monitoring of Fixed and Dual Axis Tracker using Curve Fitting Technique. International Journal of Innovative Technology and Interdisciplinary Sciences 2023, 6, 1264–1272. [Google Scholar]

- Koysuren, O.; Dhoska, K.; Koysuren, H.N.; Markja, I.; Yaglikci, S.; Tuncel, B. SiO2/WO3/ZnO based self-cleaning coatings for solar cells. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2024, 110, 183–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Đurašković, J.; Konatar, M.; Radović, M. Renewable energy in the Western Balkans: Policies, developments and perspectives. Energy Reports 2021, 7, 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topalović, Z.; Haas, R. Role of Renewables in Energy Storage Economic Viability in the Western Balkans. Energies 2024, 17, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, S.M.; Khan, H.A.; Hussain, A.; Tariq, S.; Zaffar, N.A. Harmonic analysis of grid-connected solar PV systems with nonlinear household loads on low-voltage distribution networks. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13073709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco, C. Doig et al. “Comparison of voltage stability indices in IEEE-39 bus system using RTDS”, October 2012.

- Walling, R.A.; Saint, R.; Dugan, R.C.; Burke, J.; Kojovic, L.A. Summary of the impact of distributed resources on power distribution systems. IEEE Trans. Power Delivery. 2008, 23, 1636–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, K.; Achanta, S.; Rowland B.; and Kivi A. Mitigating the Impacts of Solars on the Power System. Power and Energy Automation Conference Spokane, Washington, USA, March 21–23, 2017.

- International Renewable Energy Agency: Albania’s Renewable Energy Sector. Available online: https://www.irena.org (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Zhang, Y.; Ma, C.; Lian, J.; Pang, X.; Qiao, Y.; Chaima, E. Optimal solar capacity of large-scale hydro-solar complementary systems considering power supply requirements and reservoir characteristics. Energy Converters. Journal 2019, 195, 597–608. [Google Scholar]

- Salama, H.S. Salama, H.S., Kotb, K.M., Vokony, I., Dán, A. The Role of Hybrid Battery–SMES Energy Storage in Enriching the Permanence of PV–Wind DC Microgrids: A Case Study. Eng. 2022, 3, 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., Wang, J.; Piao, Z.; Meng, X.; Sun, C.; Yuan, G.; Zhu, S. “Optimal allocation and operation of an energy storage system with high-penetration grid-connected solar systems”. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6154. [CrossRef]

- Armenta-Déu, C. , Sancho, L. Sustainable Charging Stations for Electric Vehicles. Eng. 2024, 5, 3115–3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).