1. Introduction

Traditional power networks are characterized by a limited number of centrally situated, high-capacity plants. Many countries are undergoing a swift transition to RE generation [

1]. The global energy industry is experiencing a profound revolution propelled by the imperative to address climate change, decrease greenhouse gas emissions, and shift towards sustainable energy sources [

2]. One of the primary measures is the enhanced incorporation of RES—specifically wind, solar, and hydropower—into electrical power systems [

3]. This transition, also known as the high penetration of RE, has accelerated due to technical innovations, favourable regulations, and decreasing costs of renewable technologies [

4]. This transformation offers significant environmental and economic advantages, although it also presents several technological and operational hurdles for grid operators. In contrast to traditional fossil fuel-based generation, renewable energy sources are intrinsically changeable, reliant on meteorological conditions, and regionally distributed [

5].These attributes can affect grid stability, reliability, and efficiency if inadequately handled [

6].

The research reveals that energy efficiency and RE technologies are fundamental components of the shift, and their synergies are equally significant [

4]. RE has the potential to fulfill two-thirds of world energy demand and significantly aid in the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions required to maintain the average global surface temperature increase below 2 °C by 2050 [

7]. A growing array of indications suggests a rapid energy transition that may significantly impact energy supply and demand in the forthcoming decades [

8].

The shift towards substantial RE integration in power systems is propelled by a confluence of environmental, economic, technical, and policy-related influences [

9]. These factors are reshaping the global energy framework and expediting the incorporation of RES such as solar, wind, and hydropower into electrical networks [

2]. Presented below is a systematic summary of these major factors in

Table 1.

This research examines the KK II Solar PV Plant, which is presumably one of the RE initiatives established under South Africa’s Renewable Energy Independent Power Producer Procurement Programme (REIPPPP) [

15]. KK II solar PV is in the Northern Cape, South Africa (many RE projects are situated there due to high solar irradiance). This PV plant has a total installed capacity of 75MW [

16]. Secondly, this study uses Metro Wind Van Stadens Wind Farm situated in the Eastern Cape, with an installed capacity of 27 MW, including 9 turbines of 3 MW each [

17].

Figure 1(a & b) elegantly illustrates a solar power plant at sunrise, representing the emergence of renewable energy options.

Figure 1 (c & d) illustrates the operation of wind energy, wherein these turbines transform kinetic wind energy into electricity, therefore enhancing a cleaner power system.

3. Design and Implementation of RE into the Grid

This section illustrates the integration of RE into the grid, outlining the mathematical methodologies employed in the construction of both wind farms and solar PV plants, aimed at diminishing the reliance on fossil fuels, which adversely impact both the environment and human health.

3.1. Uncertainty of Wind Power

Wind Energy Uncertainty signifies the unpredictable nature of wind energy generation resulting from the variability and limited controllability of wind resources. Unpredictability poses significant challenges for power system design, operation, and reliability, especially with the increasing integration of wind generation. The wind speed follows a Weibull distribution, with the probability density function (PDF) utilized for the wind variations.

The scaling index c may be derived from the average wind speed at a certain location, as seen in

Take into account the wind velocity, shape factor, and scale factor, referred to as

,

and

, respectively, where,

and

Then, the wind power output can be stated as

, and are recognized as cut-in wind speed, rated wind speed, and cut-out wind speed, respectively. is the rated power of a wind unit.

The probability of each condition is expressed by the following equation:

Where and represent the velocity restrictions in state w.

3.2. Unpredictability in Decentralized Solar Energy

The swift implementation of localized solar energy systems has revolutionized power generation by fostering sustainability and energy autonomy. The intrinsic unpredictability of solar energy generation presents considerable hurdles to grid stability, energy planning, and storage management [

36]. Weather unpredictability, seasonal fluctuations, and the geographic distribution of PV systems contribute to inconsistent energy production, complicating precise forecasting [

37]. The absence of centralized coordination among several small-scale producers complicates demand-supply equilibrium and grid integration.

The stochastic lighting intensity is the predominant component in solar generation. Numerous studies have shown that the probability density function adheres to the Beta distribution as

Whereby

stands for Gamma function,

and

are the considerations,

is the illumination intensity,

is the maximum value. The communication between the illumination intensity and the output power of a solar unit can be described as

Whererepresents the rated value and represents the rated output power of the solar unit.

This study used quasi-dynamic simulation, a modeling method that lies between steady-state and fully dynamic simulations. It illustrates the evolving behavior of a system over time in a simplified, often discontinuous or stepwise manner, rather than continuously recreating every transient characteristic. This method is utilized when extensive dynamic simulations are too resource-demanding or unnecessary, yet steady-state analysis does not sufficiently capture important time-dependent processes

3.3. Available Transfer Capability (ATC) on the Wind Farm

Available Transfer Capability (ATC) indicates the highest supplementary power transfer capacity in the transmission network that may be utilized without breaching system restrictions (including temperature, voltage, and stability constraints) after considering existing commitments. In the context of wind farms, ATC pertains to the extent of supplementary wind-generated electricity that can be integrated into the grid and supplied to load centers. This network utilizes the boundary to ascertain the available transfer capability of the wind farm, excluding the rest of the network, to evaluate losses, earnings, and energy output of the wind farm.

The total transfer capability (TTC) is less than the transmission reliability margin (TRM), which is lower than the capacity benefit margin (CBM), and is also smaller than the aggregate of existing transmission commitments (ETC). This research did not examine TRM or CBM. Consequently, the ATC may be calculated by deducting the TTC from the ETC.

Subjected to

Where B is the set of all buses,

is the active power at the generator I, and

is the active power demand at the bus

,

is the voltage phase angle between the bus

and

is the scalar parameter.

This approach is intended for computing the ATC utilizing Monte Carlo simulations with a sensitivity analysis.

3.4. Design of the Wind Farm and PV Plant

This section discusses the implementation of both the wind farm and solar photovoltaic plant within DIgSILENT PowerFactory software. It outlines the design of wind turbines by including wind speed, the wind power curve, wind power capacity, distribution, and correlation. Furthermore, it indicates the design of the solar PV plant and its load characteristics, offering detailed information on the solar PV plant before its integration into the grid.

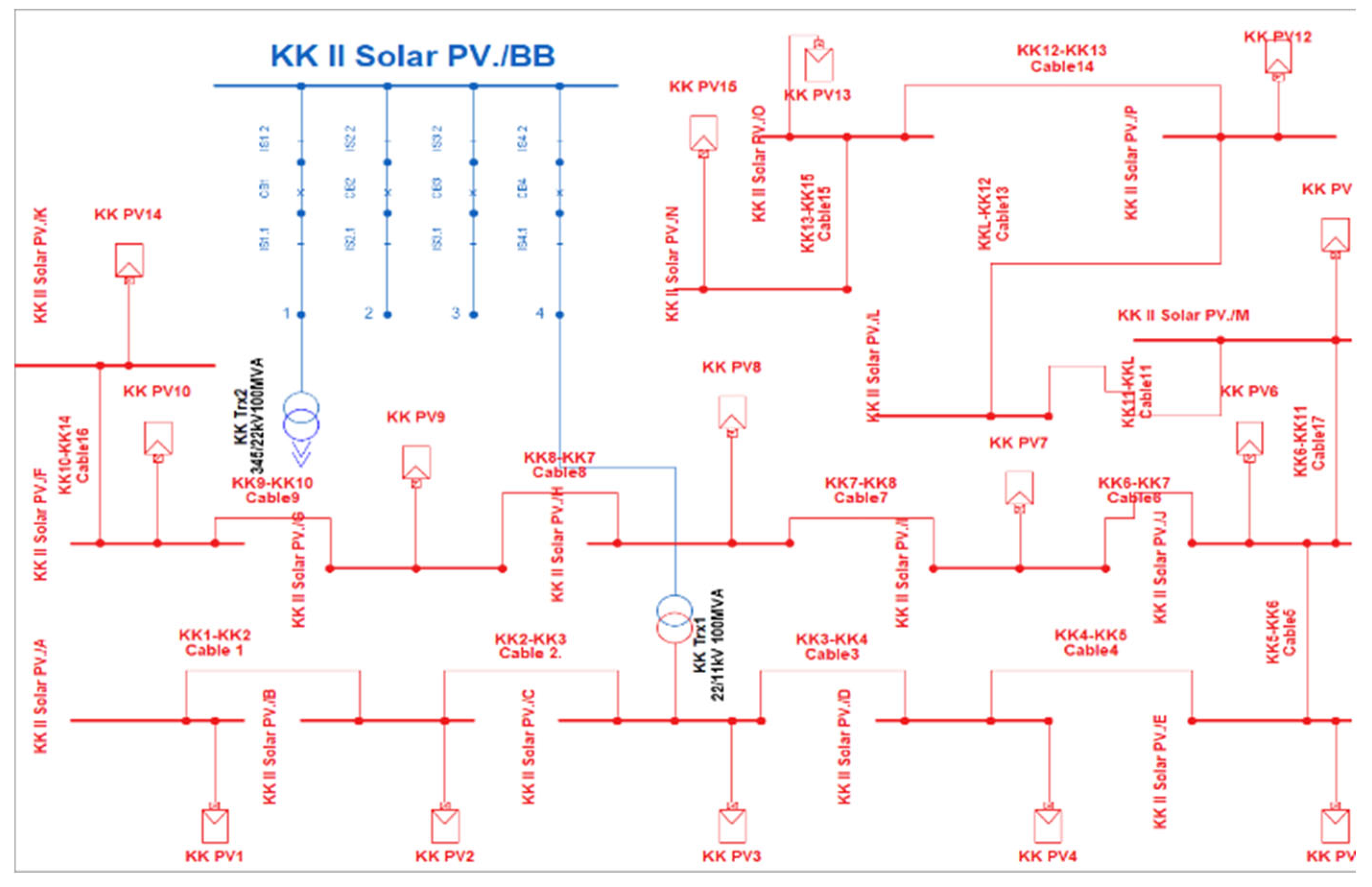

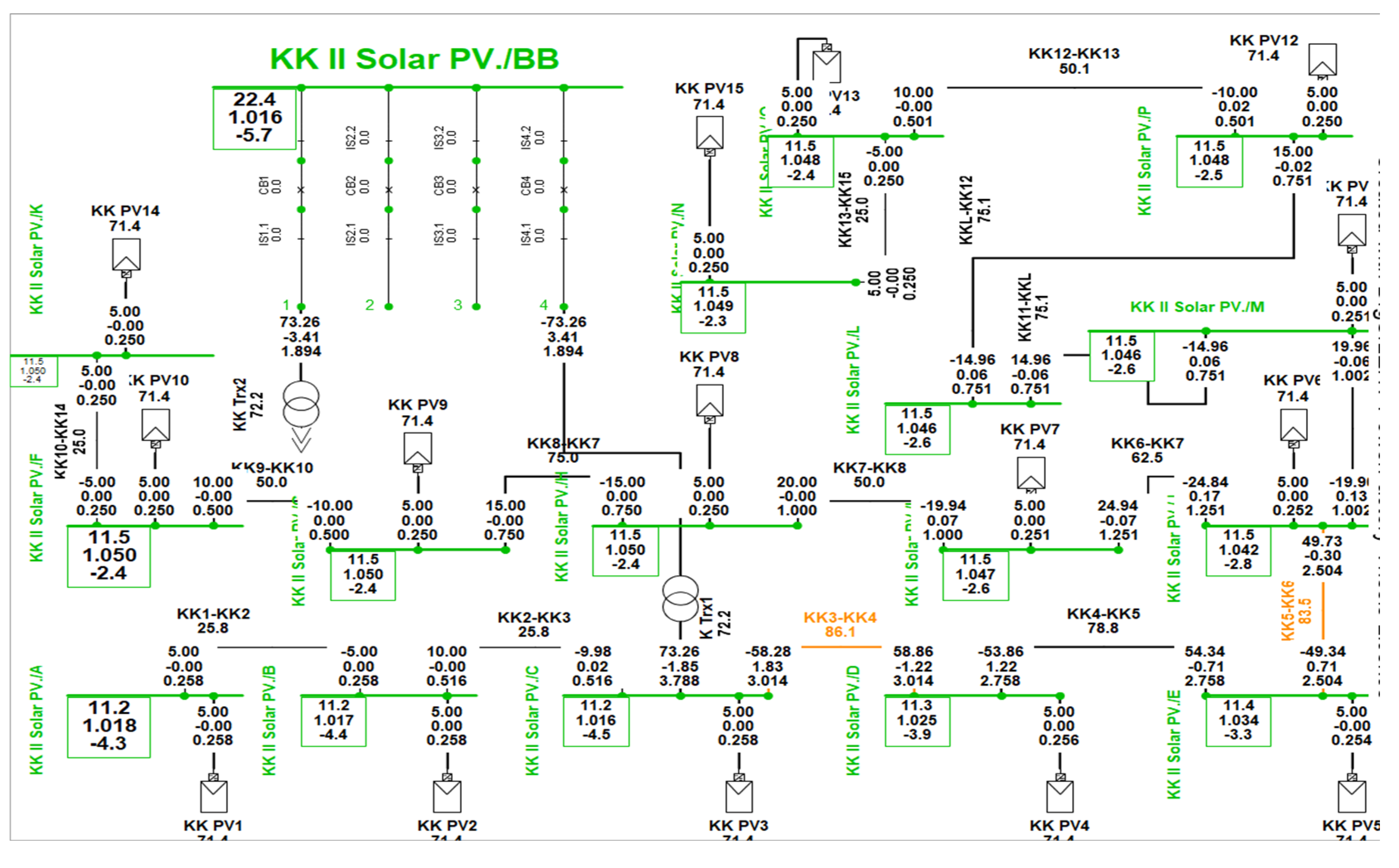

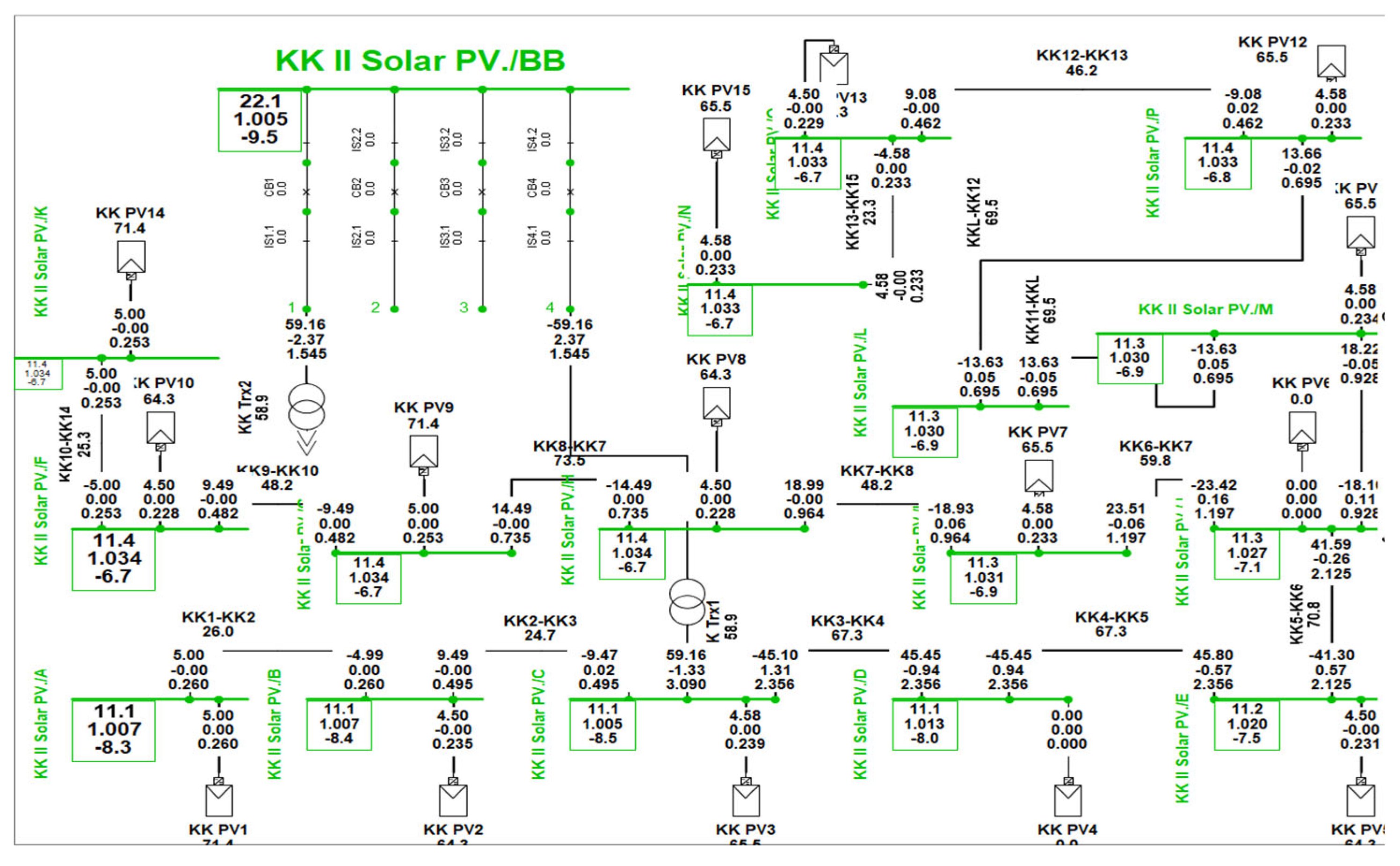

Figure 4 illustrates the KK II solar PV plant, with 15 solar PV units, each producing 5 MW, with an apparent power of 7 MVA and a power factor of 0.9, utilizing active power input for energy generation. The solar PV systems are interconnected by an 11kV busbar and a 1km cable. Additionally, a 100MVA step-up transformer with a voltage rating of 11/22kV is employed to elevate the voltage to 22kV in KK II Solar PV, as seen in

Figure 4.

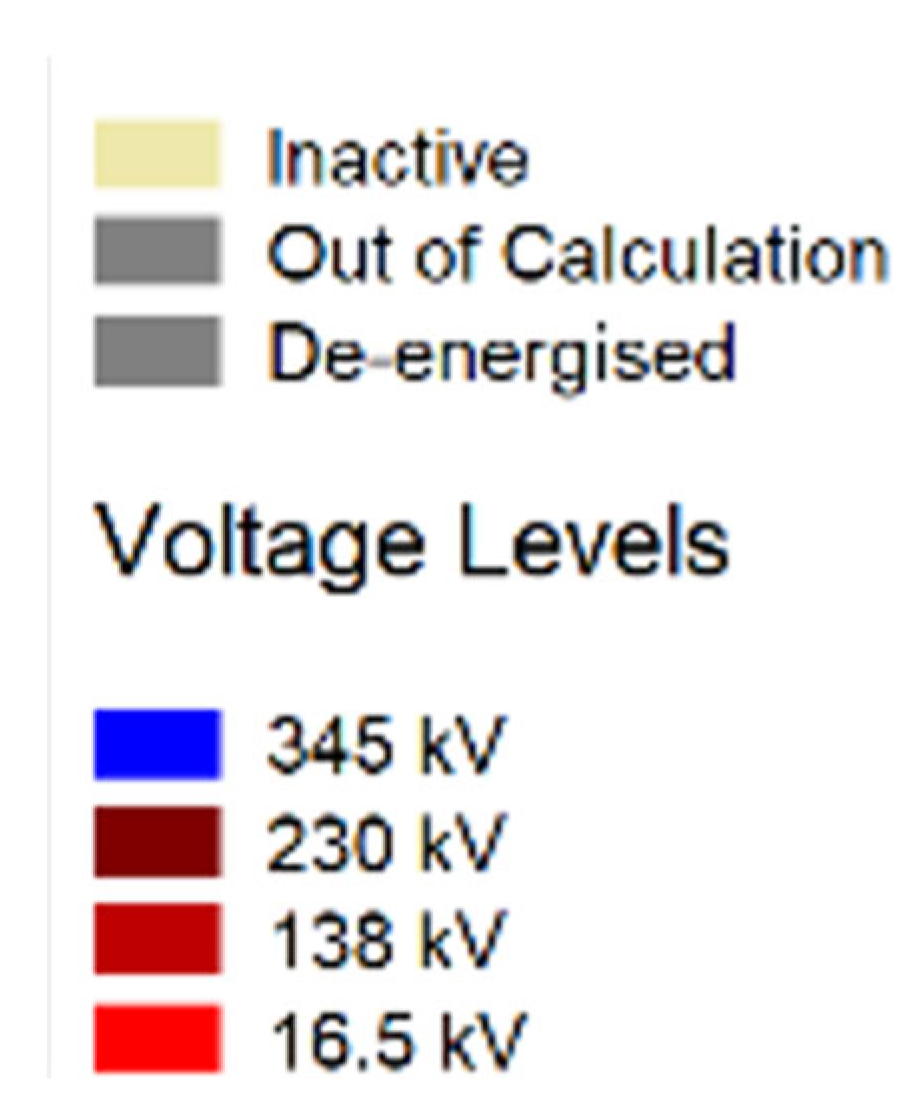

Figure 3 illustrates the voltage levels more effectively, with a minimum voltage of 16.5kV and a maximum voltage of 345kV.

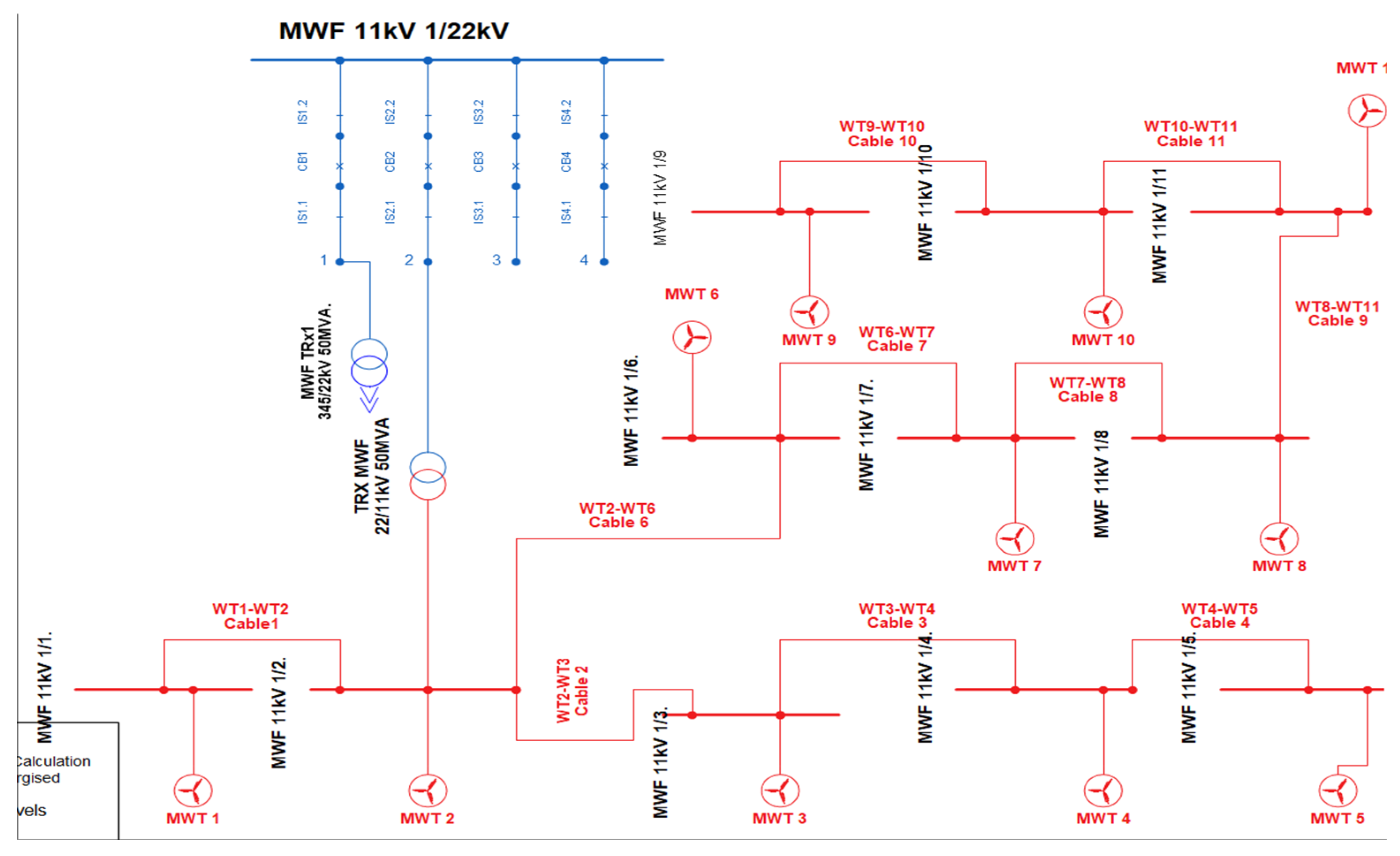

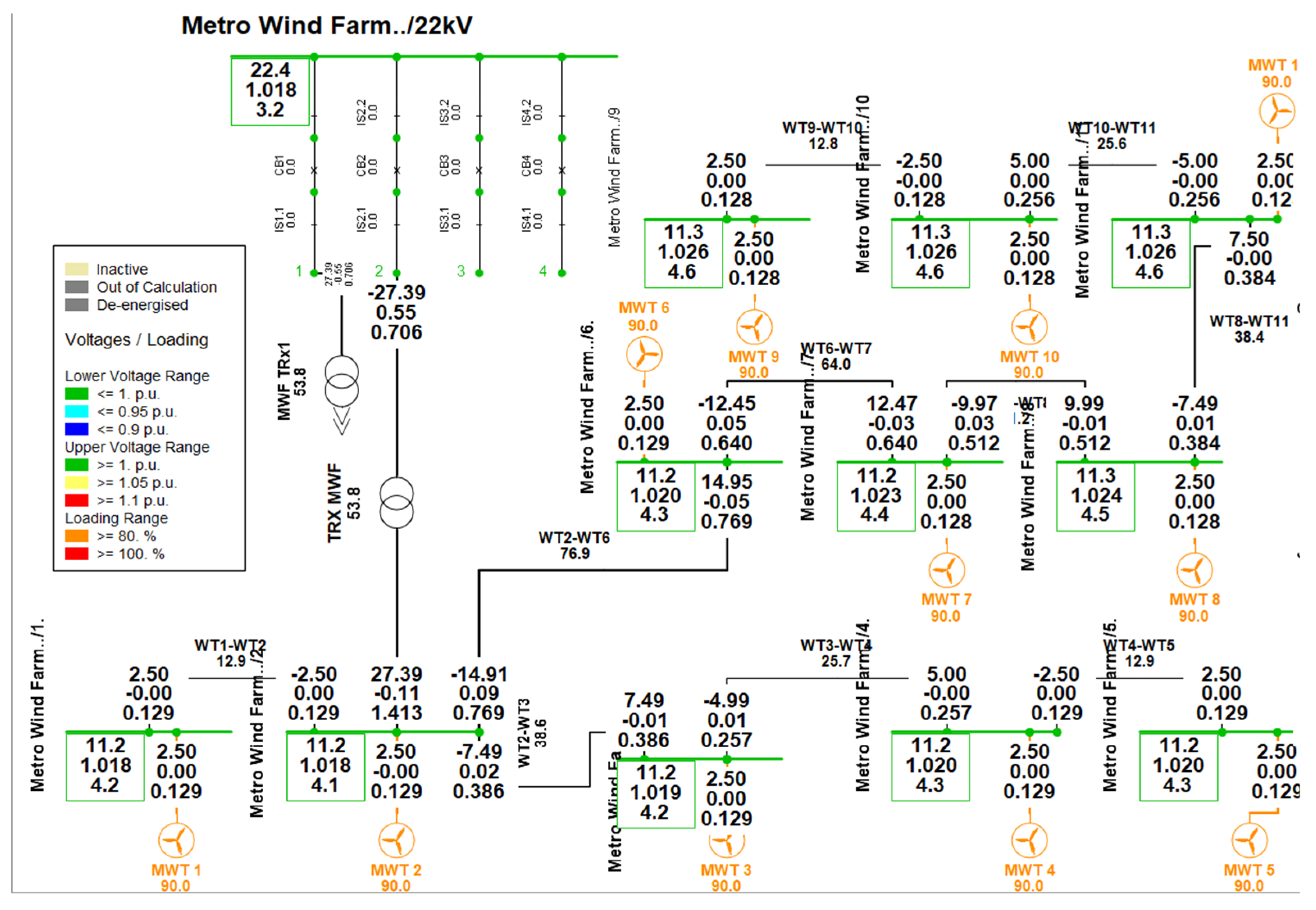

Figure 5 shows the wind farm integrated into the 39 bus England System, with 11 wind turbines, each rated at 2.778 MVA with a power factor of 0.9. The wind turbines are interconnected via an 11kV busbar and a 1km cable.

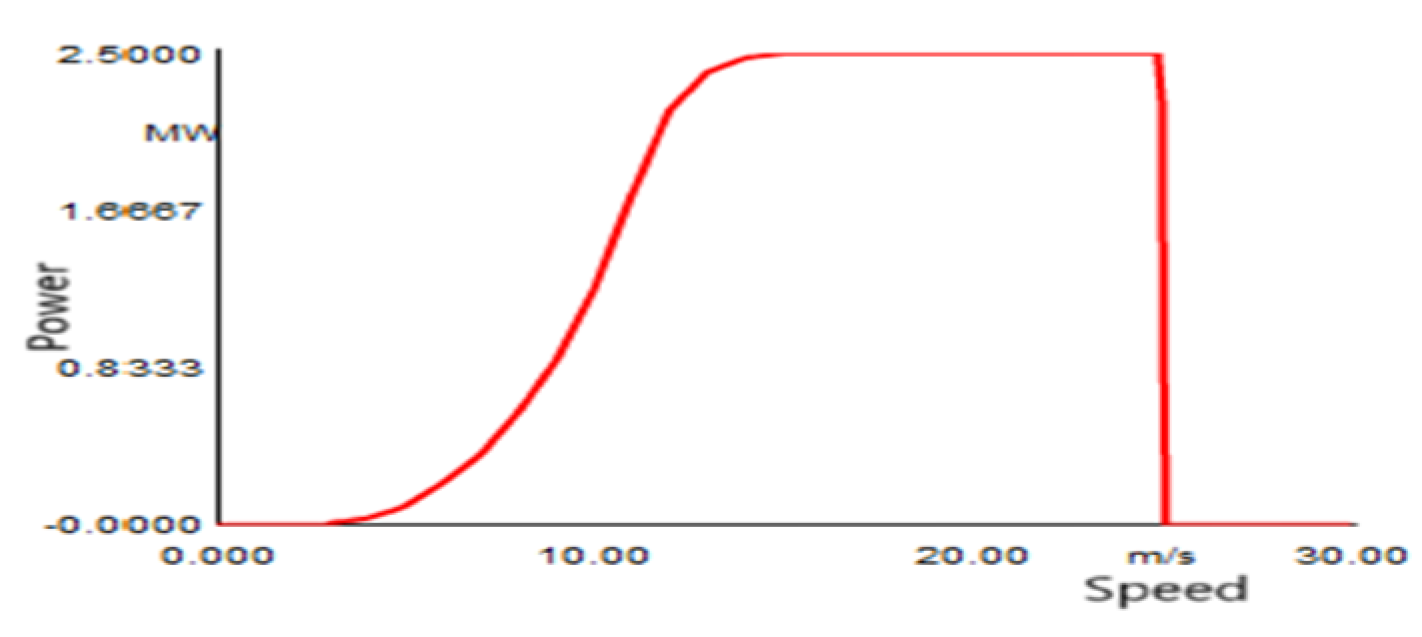

Figure 6 illustrates the wind power curve applicable to all wind turbines utilized in this study; it is evident from this curve that the turbines achieve maximum power production at a wind speed of 16 m/s.

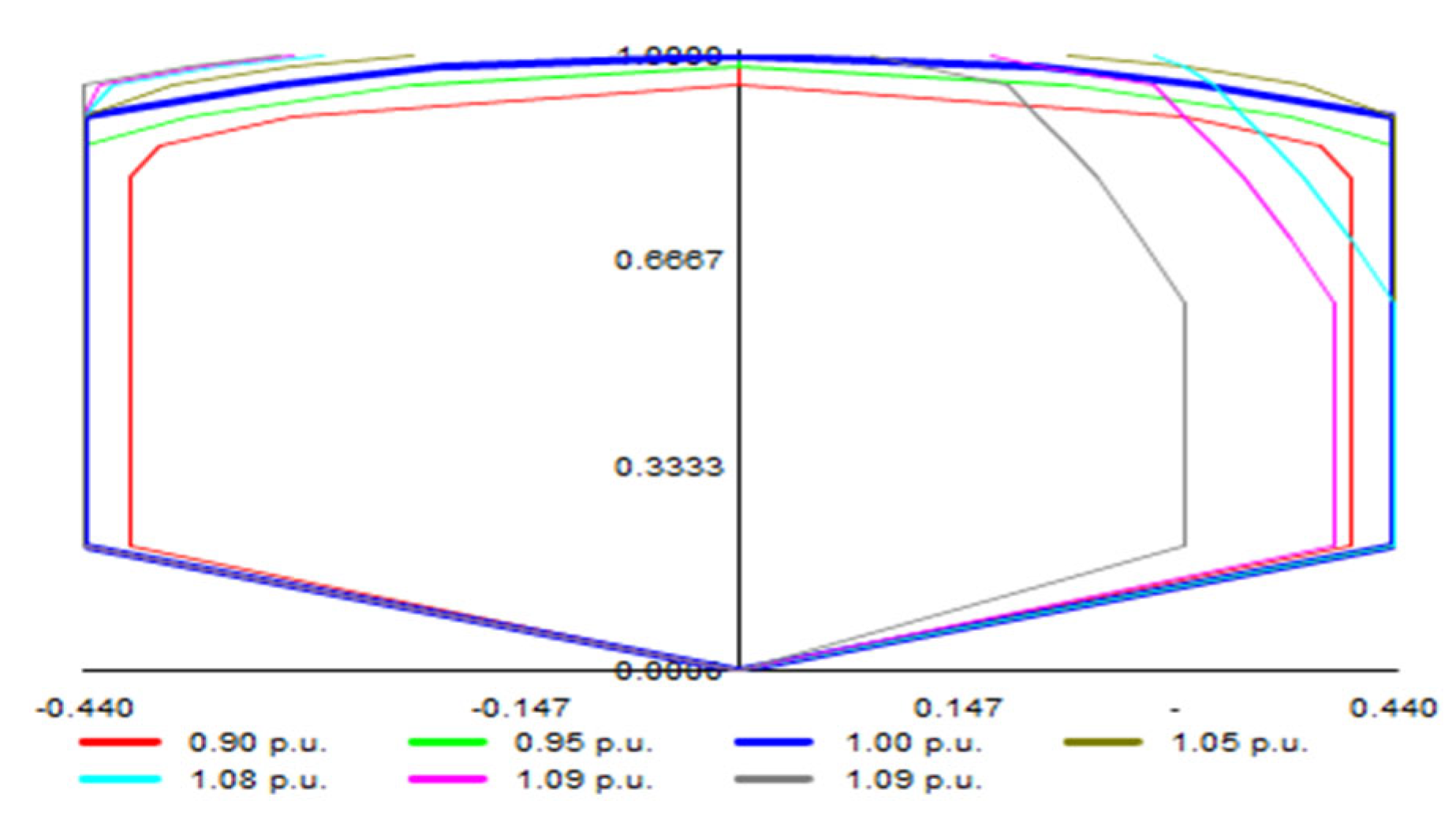

The wind power capability curve describes the operational limits of an electrical generator, specifying the restrictions on the active and reactive power it can produce. The circle defines the boundary of all operational locations as seen in

Figure 7.

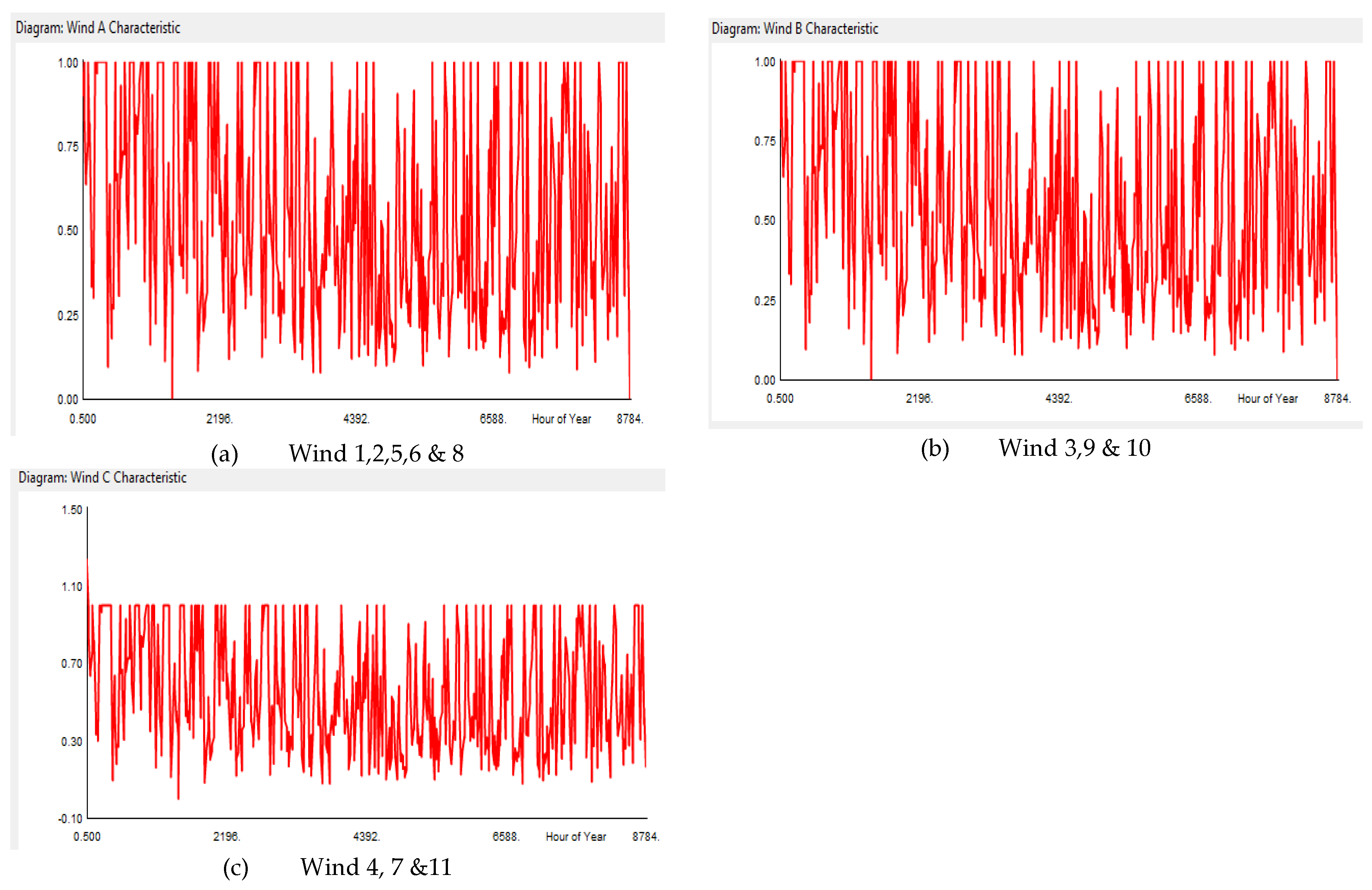

The subsequent characteristics of wind turbines dictate the quantity of wind generated, fluctuating bi-hourly throughout the year. Winds 1 and 8 exhibit identical temporal features as seen in

Figure 8, as do winds 3,9 and 10 as shown in (b).

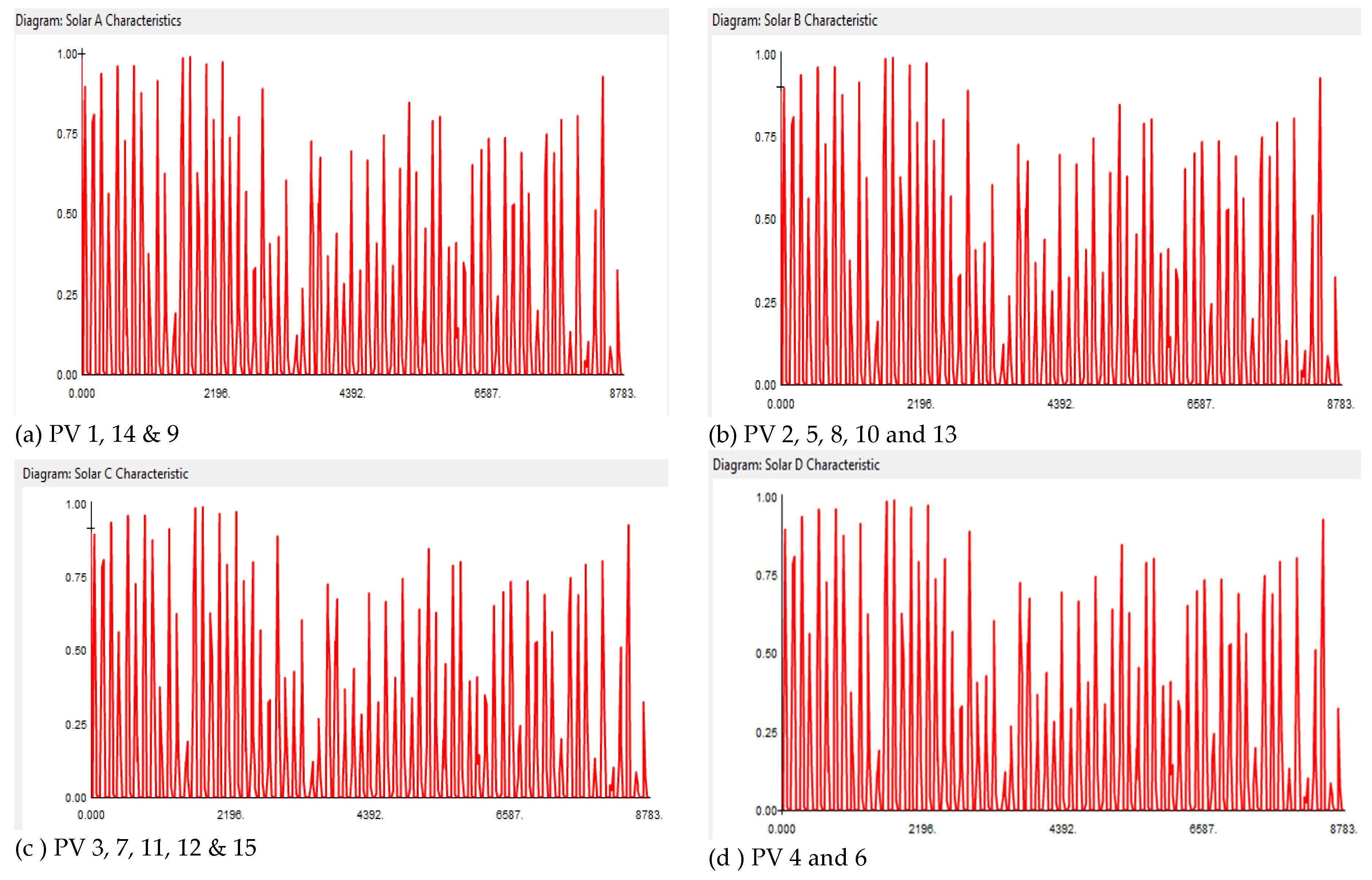

The periodic characteristics of the KK II solar PV Plant exhibit bi-hourly fluctuations throughout the year, resulting in considerable unpredictability in the generated output power, as seen in

Figure 9

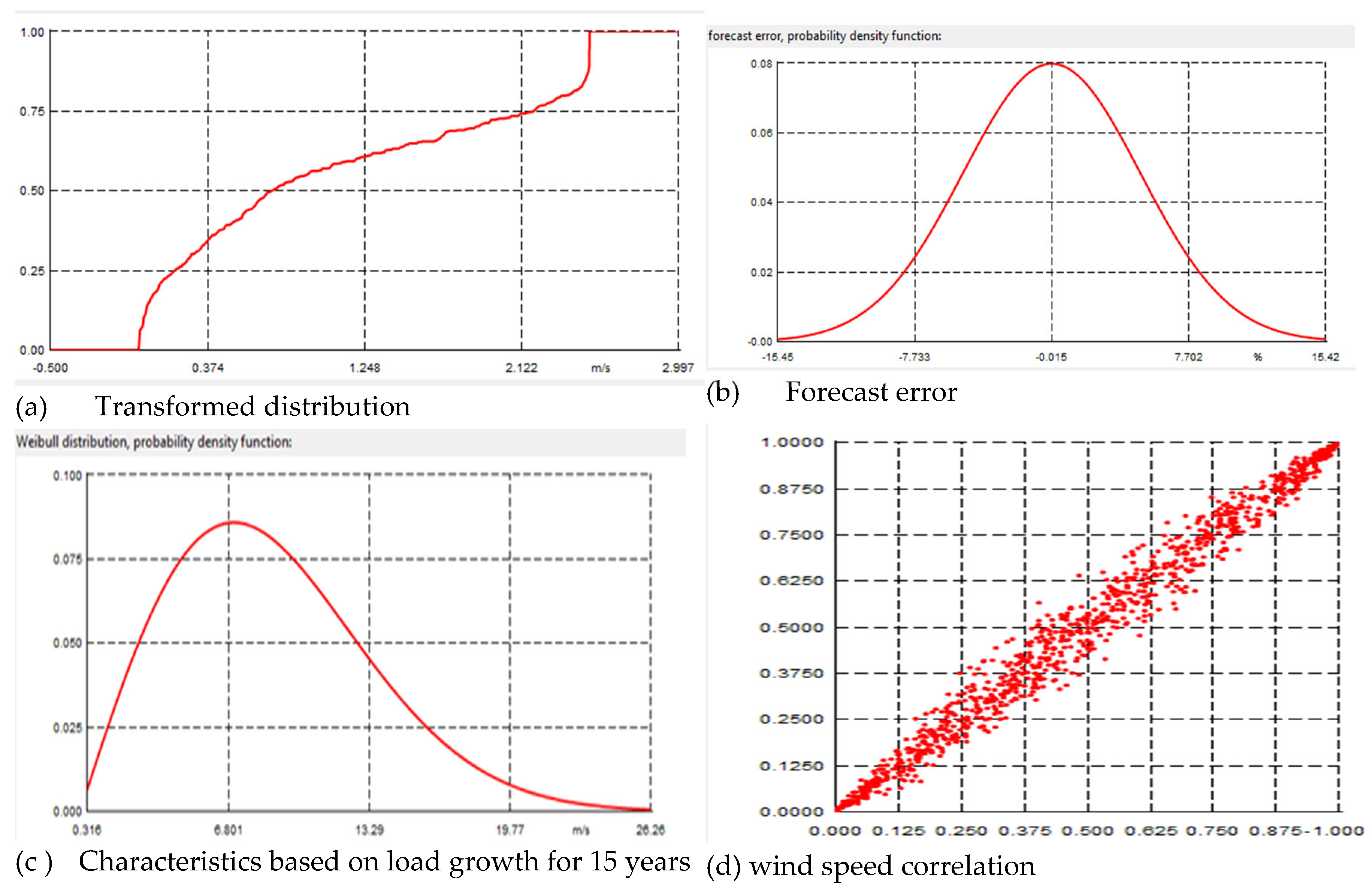

Figure 10 describes the characteristics assigned to both sources.

Figure 10(a) shows the transformed distribution assigned to the wind turbine, incorporating wind speed and the Weibull curve.

Figure 10 (b) depicts the allocation of prediction errors among generators and solar PV systems to forecast possible future mistakes.

Figure 10(c) illustrates the utilization of the Weibull distribution for wind speed, employing the shape and scale parameters provided in

Table 4.

Figure 10(d) illustrates the correlation distribution utilized to establish a relationship among the 11 wind turbines in the wind farm, with the correlation coefficient established at 0.99. A higher coefficient indicates a stronger relationship, with a value of 1 representing a perfect correlation.

4. Results

The case study is carried out and modeled in DIgSILENT PowerFactory, employing a wind farm located in the Northern Cape of South Africa, with an installed capacity of 75 MW. The 15 solar PV units, each having a capacity of 5 MW, are employed to produce energy from the KK II solar PV facility for the grid. It emphasizes the imperative of upgrading transmission lines to meet future demand while incorporating renewable energy into the current system, so improving electricity accessibility while accounting for the inherent power unpredictability of these sources. The findings are derived from load flow analysis employing the Newton-Raphson approach, while short- and long-term planning is executed via quasi-dynamic simulation to predict the potential available power across different periods. This method also enables the identification of whether the grid functions within allowable parameters, thereby reducing equipment overload and ensuring busbar values stay within acceptable levels to avoid grid instability.

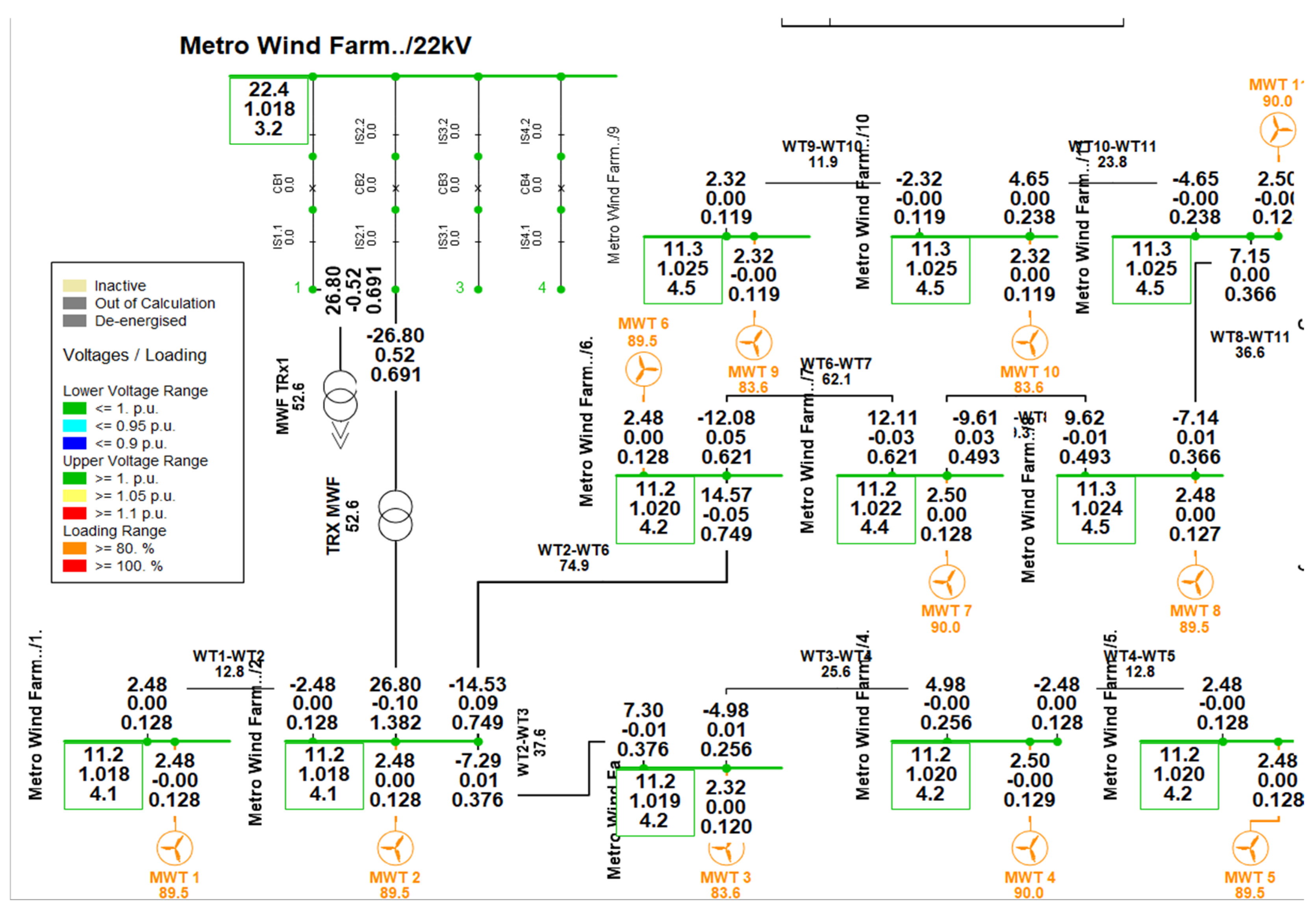

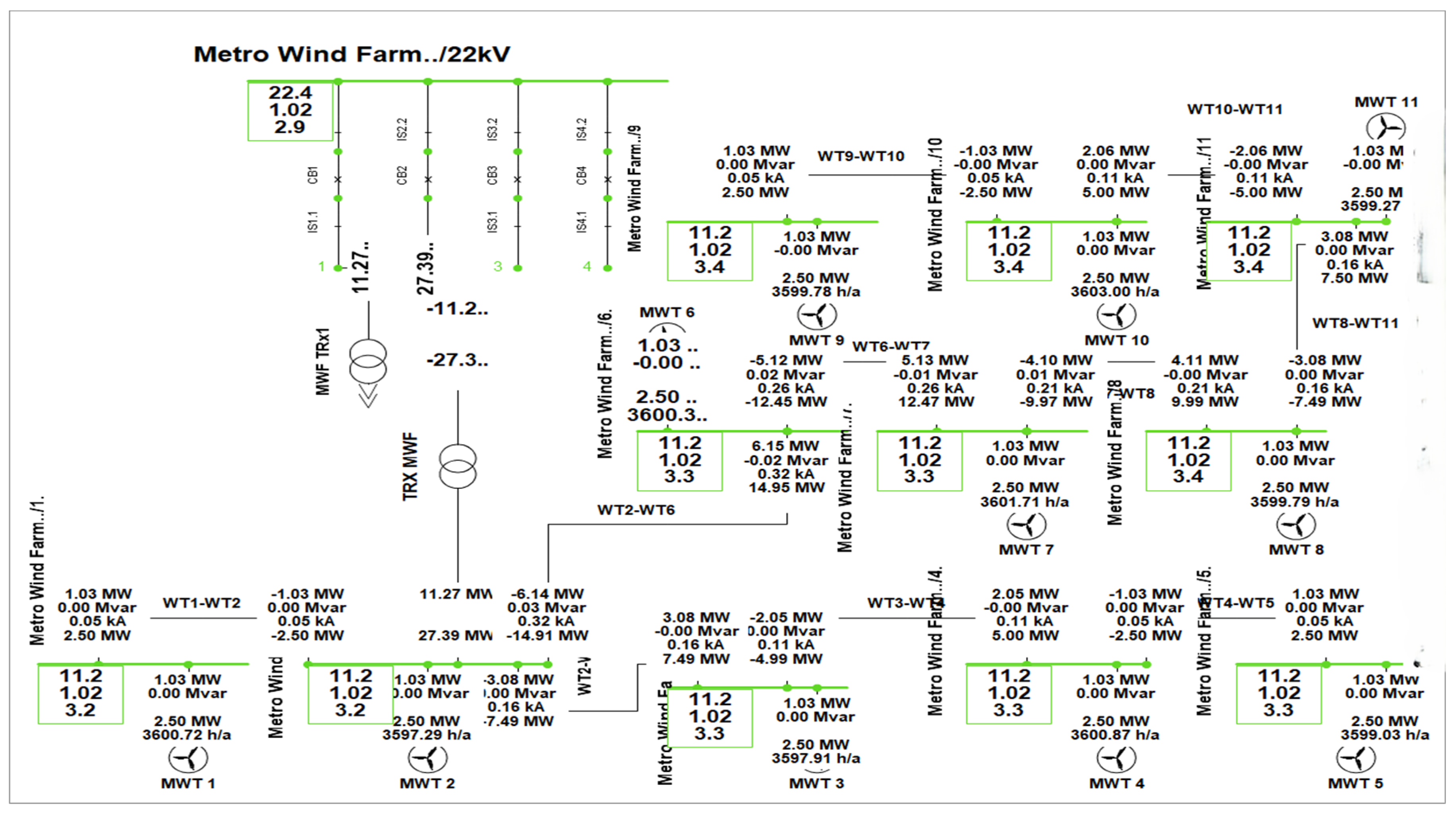

Figure 11 illustrates the simulated Metro wind farm, of 11 identical wind turbines, each generating 2.5 MW, which corresponds to 90% of their maximum capacity at a wind speed of 16 m/s. The total power generated is 27.39 MW, with minimal losses in the cables. This network indicates that the facility operates under typical conditions, as evidenced by the little box. Healthy components of the grid are represented by green in the little box in

Figure 11, whereas the unhealthy components are shown by blue or red, depending on whether the voltage is low or high.

Figure 12 represents the KK II solar PV plant, with 15 identical solar PV units, each generating 5 MW, or 71.4% of their total capacity. The total power output is 73.26 MW, with 1.74 MW lost in the cabling connecting the busbars. The KK II solar PV power system operates within acceptable parameters, hence improving system stability.

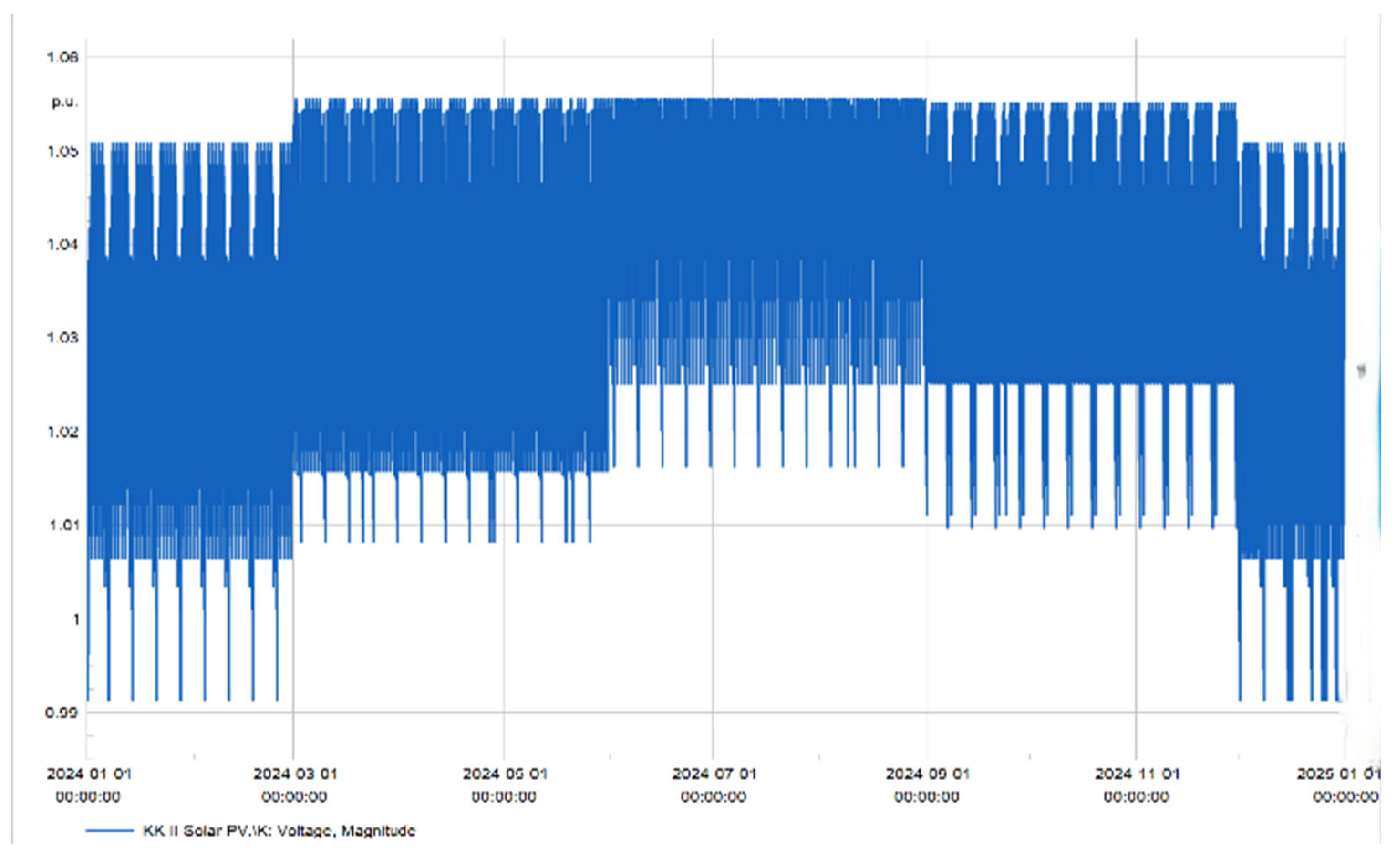

Figure 13 illustrates the p.u. voltage over one year for the busbar in the wind farm. Despite variations, all busbars within the network function within constrained limitations.

Figure 14 illustrates the metro wind farm undergoing quasi-dynamic simulation. Each wind turbine has distinct characteristics, as seen in

Figure 8, resulting in variations every thirty minutes throughout the year. It demonstrates that WT1 has differing active power levels relative to WT3

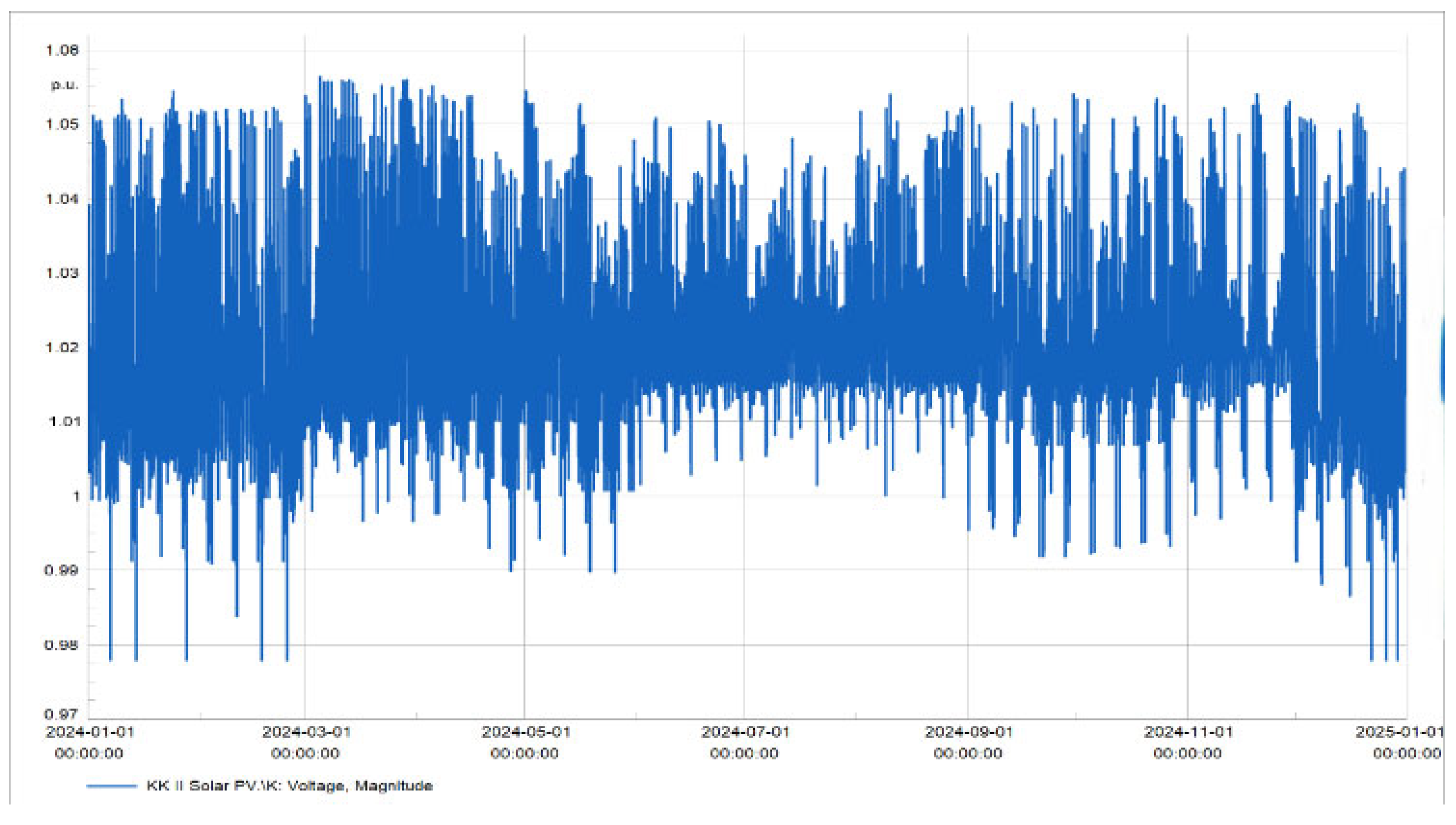

Figure 15 illustrates the solar power plant under quasi-dynamic simulation, containing 15 solar PV units with distinct characteristics, as previously detailed in

Figure 8. The figure demonstrates that PV1 differs from PV2 and PV3, highlighting the inherent uncertainty associated with RE. Furthermore, in contrast to

Figure 12, the PV plant is currently generating a total output of 59.16 MW

The variability in loading, evidenced by the non-uniform shape, contrasts with

Figure 13, suggesting an anomaly in the voltage at busbar K in

Figure 16. It illustrates that the PV plant functioned for one year, with the graph’s fluctuations indicating electricity production variations over different seasons, including vacations and weekends.

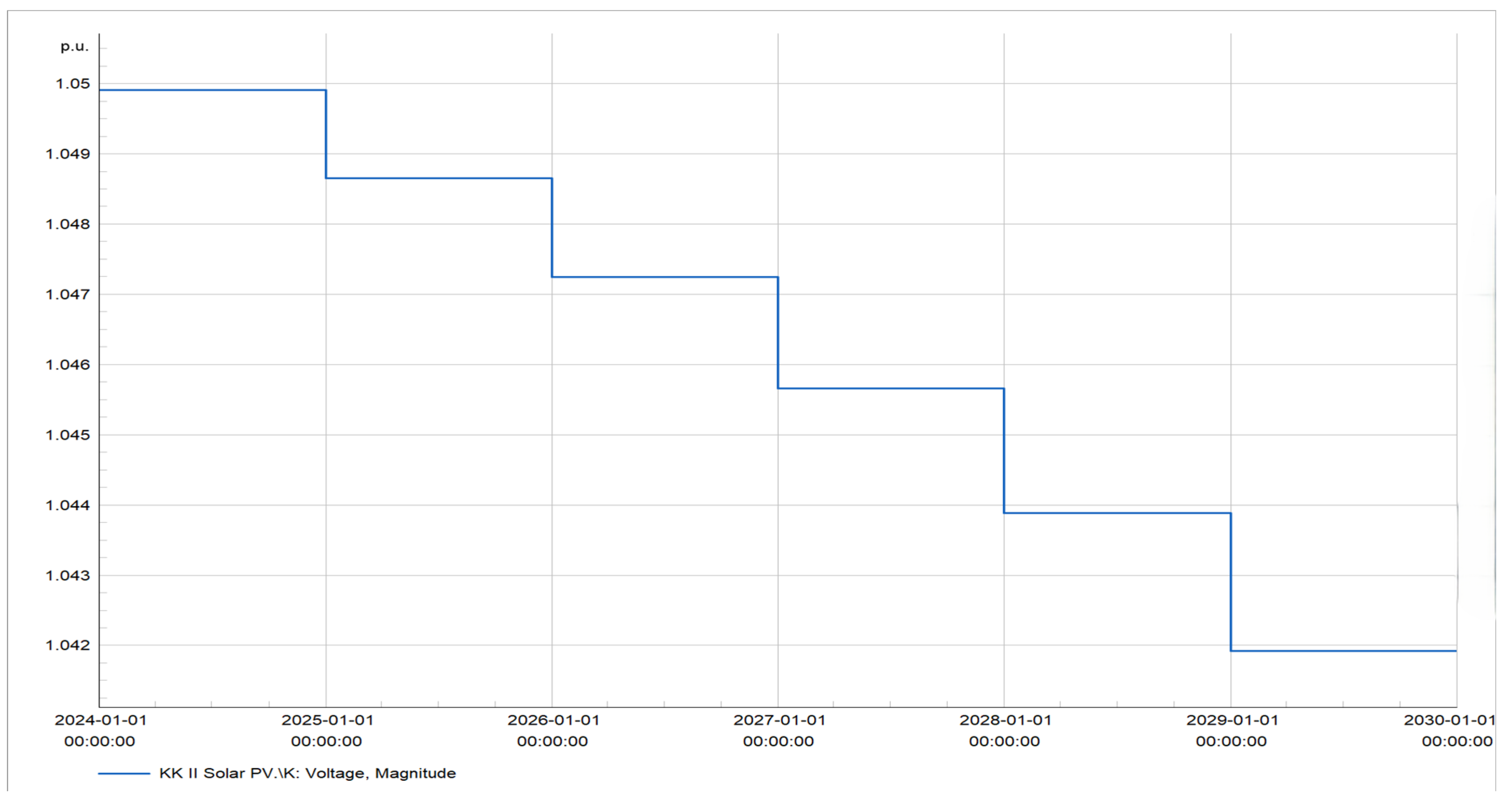

Figure 17 illustrates the busbar voltage p.u., indicating that all busbar voltages remain within permissible limits. Additionally, it is observed that the voltage decreases as load demand escalates.

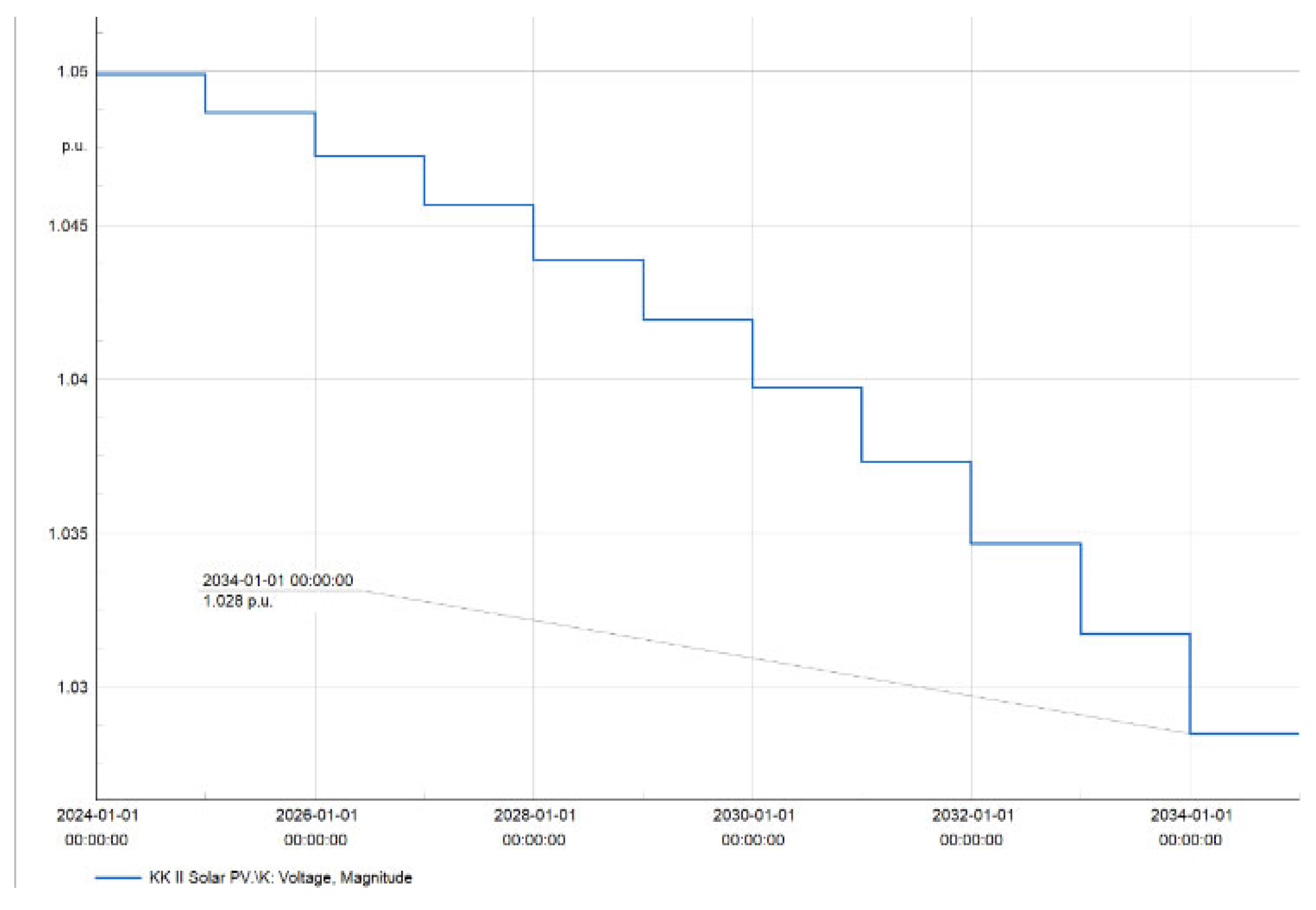

Figure 18 displays the line voltage in p.u, which is still within permissible limits despite having increased in comparison to

Figure 17. Moreover,

Figure 18. illustrates that the PV plant operated for a decade, from 2024 to 2034. As the load demand escalated, the voltages on the busbars dropped, although they remained within permissible limits.

In conclusion, it is essential to emphasize RE to mitigate the use of dwindling fossil fuels. This study demonstrates how to analyze the PV plant to guarantee that its connection to the grid does not threaten grid stability.

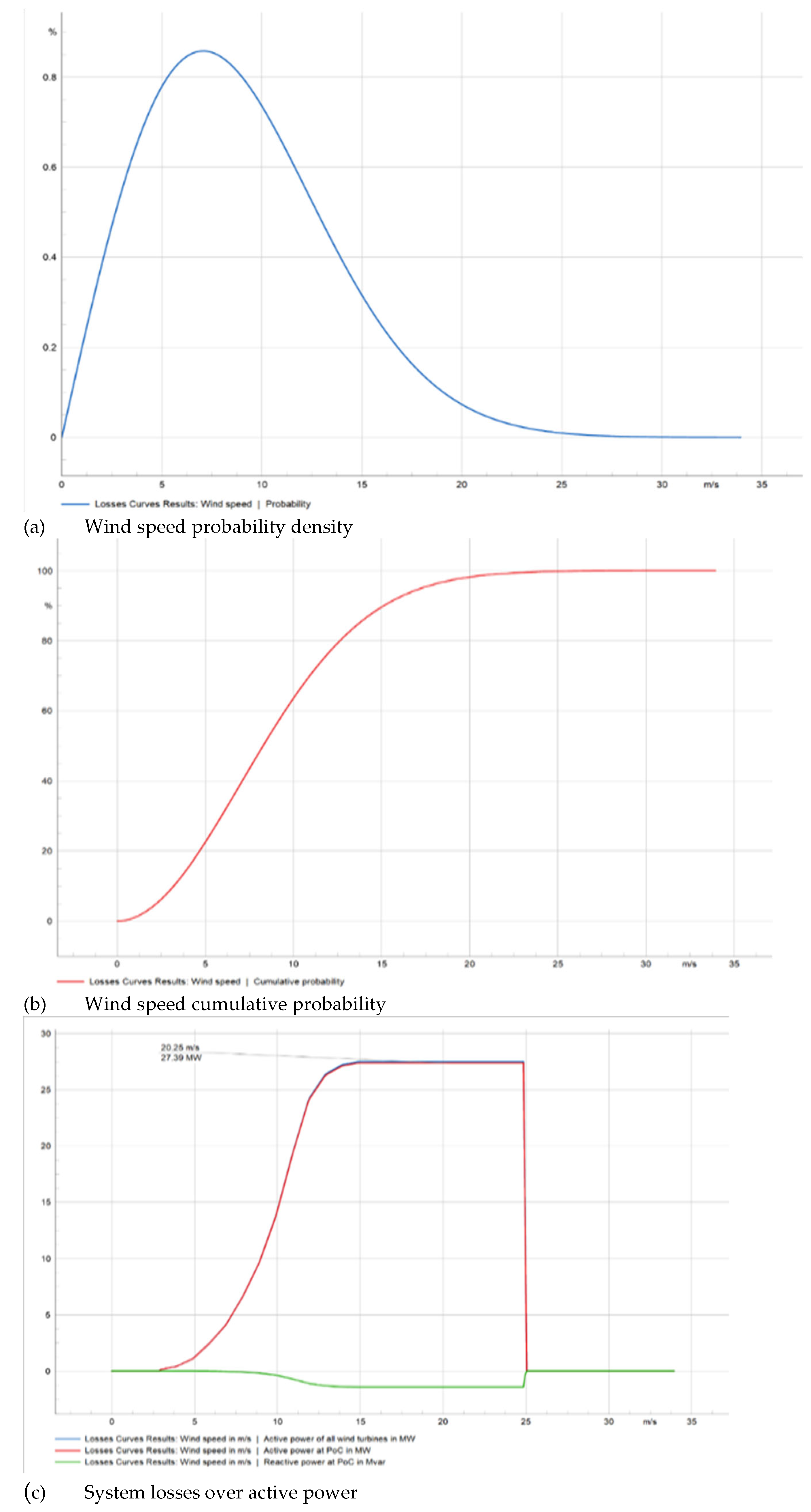

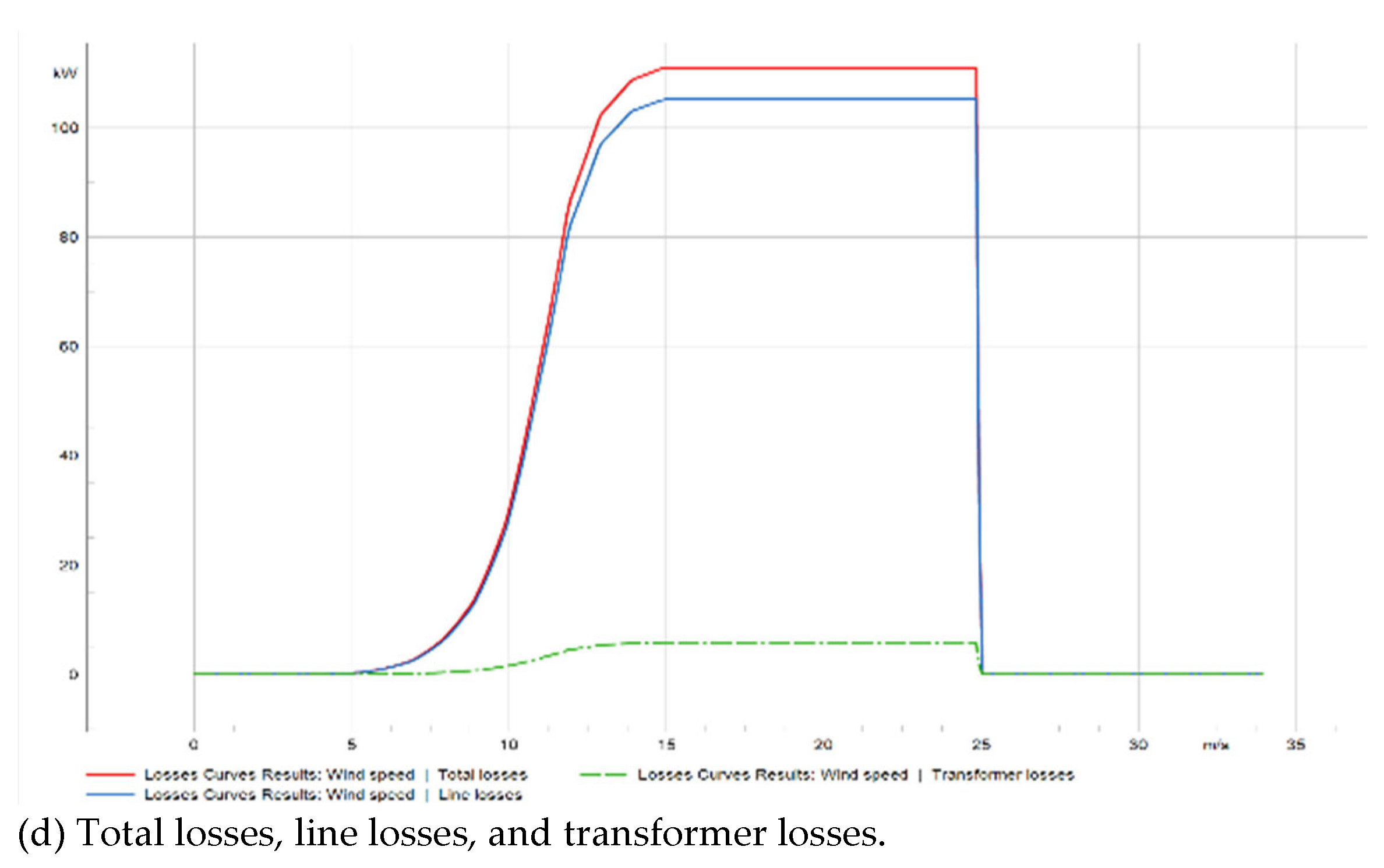

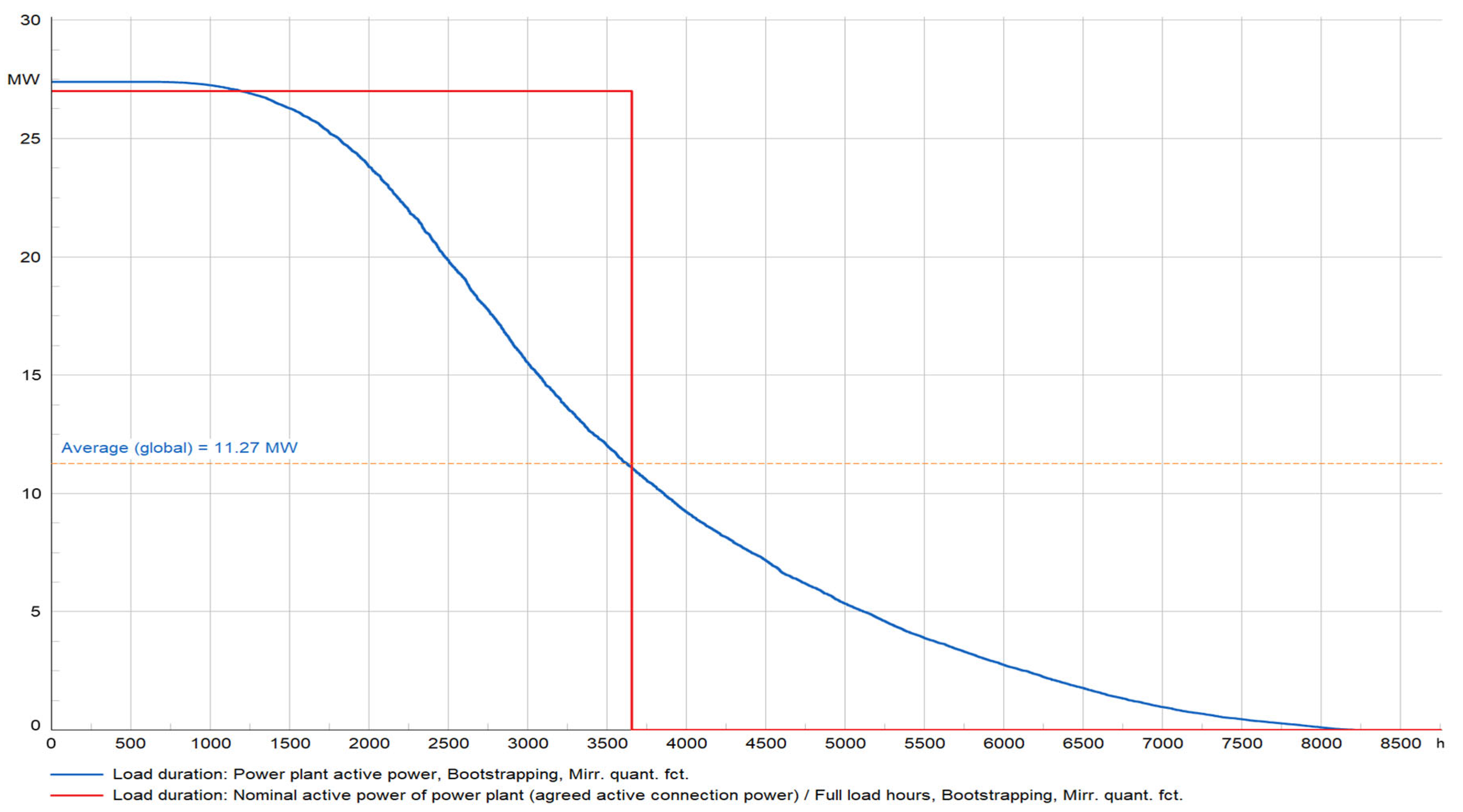

The energy study of the wind farm is executed utilizing a fundamental calculation method, which carries out a sequence of load flow computations over the spectrum of wind speeds from zero to the highest speed being evaluated. The wind farm consists of 11 wind turbines with uniform layouts. During the evaluation of wind speed, electrical losses in the network at each wind velocity are calculated by load flow analysis, considering the operational constraints of the turbine’s active and reactive power.

Consequently, yearly energy losses are calculated utilizing a Weibull distribution of the given wind speed. This tool, grounded in load flow calculations, facilitates the identification of essential metrics like losses, energy, and profit.

Figure 18. shows the fluctuation in wind speed with the electrical losses in the network calculated by load flow analysis for each wind speed.

Figure 19 (a) presents the probability density curve for wind speed, whereas

Figure 19 (b) displays the cumulative probability for wind speed.

Figure 19 (c) illustrates the upper section, which shows the active power losses and active power of all wind turbines at the point of common connection as a function of wind speed, while the lower section displays the reactive power at the point of common coupling.

Figure 19 (d) delineates the transformer losses inside the wind farm, encompassing both total losses and line losses.

Table 5 outlines the methodology employed to evaluate the wind farm, specifically the fundamental analysis used to assess losses, profitability, and energy output. Initially, a method referred to as the boundary tool was utilized to isolate the wind farm from the rest of the network, to evaluate the potential power transfer from the wind farm to the entire network, whereby the PoC is the Point of Common Coupling, and USD is the United States Dollar.

This study examines the management of uncertainty associated with RE through quasi-dynamic simulation, which can forecast power probabilities over extended periods. It also illustrates the grid’s reliability and stability, facilitating effective planning for the integration of RE into the system. This research is crucial as global attention increasingly shifts towards RE and the reduction of coal usage due to its detrimental effects. Additionally, it presents strategies for calculating losses, profits, and energy through basic analysis.

The second component performs a probabilistic analysis using the QMCS approach, evaluating the tariff over a one-year duration. This methodology evaluates probabilistic data inputs and generates stochastic outcomes, from which statistical measures like mean values and standard deviations may be obtained.

Figure 20 illustrates the wind farm undergoing probabilistic analysis, showing the mean power production for each wind turbine. MWT 7 has an average power output of 1.03 MW and an annual full load hour (FLH) of 3601.71 hours.

Figure 21 illustrates the wind farm undergoing probabilistic analysis, showing the mean power production for each wind turbine. MWT 7 has an average power output of 1.03 MW and an annual full load hour (FLH) of 3601.71 hours.

Table 5 and

Table 6 delineate the approaches utilized for the study of the wind farm, namely fundamental analysis and probabilistic analysis, in evaluating losses, profits, and energy output. A technology called the boundary tool was initially utilized to isolate the wind farm from the rest of the network in order to evaluate the potential power transfer from the wind farm to the entire network. A comparison of both tables reveals that the average power throughout the year is practically identical. Fundamental analysis generates more returns than probabilistic analysis; nevertheless, it also results in increased losses. Moreover, the probabilistic analysis indicates that the mean power output of each turbine ensures network stability and electrical capacity.

4. Discussion and Future Trends

The substantial integration of RE into the power grid is a pivotal aspect of the global energy transition, seeking to diminish reliance on fossil fuels, decrease greenhouse gas emissions, and bolster energy security. Integrating substantial amounts of renewable energy into the current grid infrastructure poses many technological, economic, and regulatory issues. This study used two renewable energy sources, namely solar PV plants and wind farms, to demonstrate the significance of integrating RE into the grid over an extended duration, considering the unpredictable power production associated with the incorporation of RE into the system. This work employs time characteristics linked to the operation of both wind turbines and solar PV plants to regulate power production, as seen in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9. Initially, both plants provide uniform power, as seen in

Figure 11 and

Figure 12, which is further illustrated by

Figure 13, showing the busbar with consistent voltage magnitude. The quasi-dynamic modelling tool demonstrates that the plants exhibit power variations based on their features over both short and long durations, further elucidated by figures 16, 17, and 18. Furthermore, the research examines the wind farm, initially employing the boundary tool to illustrate the power generated by the wind farm to the broader network. It also analyzes losses, profits, and energy production from the farm through both fundamental and probabilistic studies as shown in

Table 5 and

Table 6.

Future trends regarding the extensive integration of RE into the grid, emphasizing both technological advancements and structural developments, are anticipated to influence the energy landscape. Enhanced Grid Flexibility and ModernizationSmart Grids necessitate increased use of intelligent technology to regulate the real-time equilibrium of supply and demand. Enhanced forecasting that refined predictive instruments for sun, wind, and load fluctuations. Digitalization refers to the integration of Internet of Things (IoT), Artificial Intelligence (AI), and data analytics to enhance grid operations.

Figure 1.

Solar Plant and wind farm. [source: Google photos].

Figure 1.

Solar Plant and wind farm. [source: Google photos].

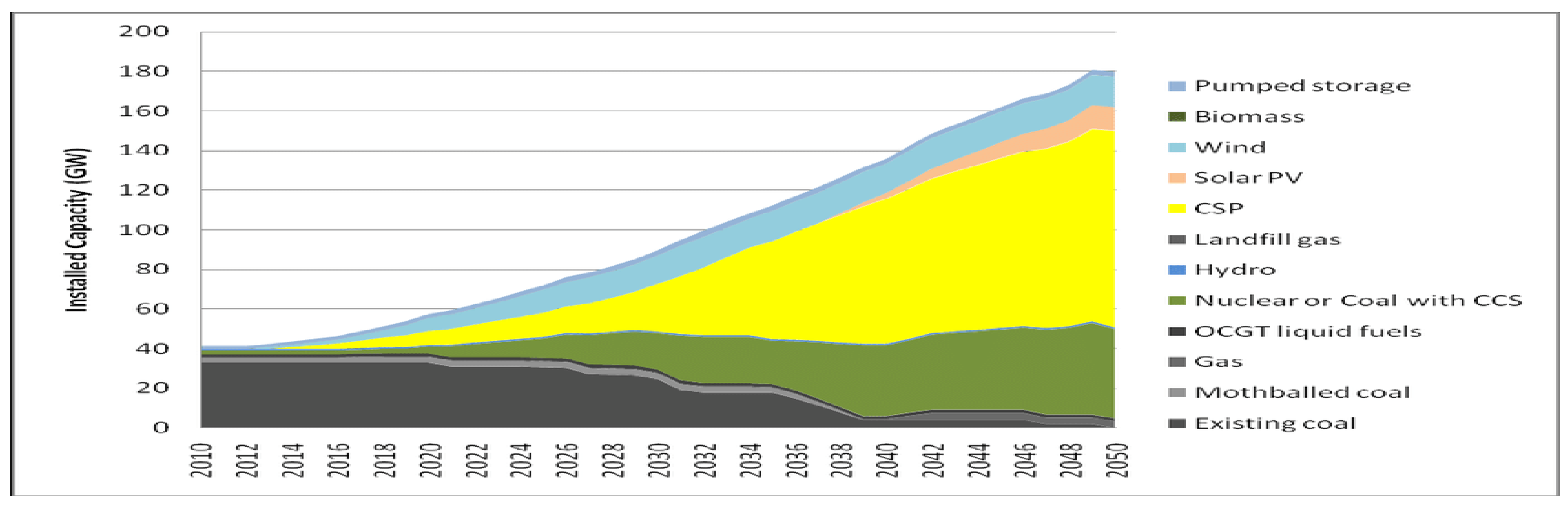

Figure 2.

Projected generation mix in SA. [source: draft integrated resource plan 2010-2050—South Africa Department of Energy].

Figure 2.

Projected generation mix in SA. [source: draft integrated resource plan 2010-2050—South Africa Department of Energy].

Figure 3.

Voltage levels.

Figure 3.

Voltage levels.

Figure 4.

KK II Solar PV Plant.

Figure 4.

KK II Solar PV Plant.

Figure 5.

Metro wind farm.

Figure 5.

Metro wind farm.

Figure 6.

Wind turbine speed.

Figure 6.

Wind turbine speed.

Figure 7.

Wind power capability curve.

Figure 7.

Wind power capability curve.

Figure 8.

Characteristic wind generator time.

Figure 8.

Characteristic wind generator time.

Figure 9.

Characteristic solar generator time.

Figure 9.

Characteristic solar generator time.

Figure 10.

distributed characteristics and wind speed correlation.

Figure 10.

distributed characteristics and wind speed correlation.

Figure 11.

Metro wind farm simulation network.

Figure 11.

Metro wind farm simulation network.

Figure 12.

KK II solar PV plant.

Figure 12.

KK II solar PV plant.

Figure 13.

KK II solar Busbar Voltage p.u for 1 year.

Figure 13.

KK II solar Busbar Voltage p.u for 1 year.

Figure 14.

Metro Wind Farm Under Quasi-Dynamic Simulation.

Figure 14.

Metro Wind Farm Under Quasi-Dynamic Simulation.

Figure 15.

KK II Solar PV Plant Under Quasi-Dynamic Simulation.

Figure 15.

KK II Solar PV Plant Under Quasi-Dynamic Simulation.

Figure 16.

KK II Solar PV Busbar Voltage (p.u) for 1 year under quasi-dynamic.

Figure 16.

KK II Solar PV Busbar Voltage (p.u) for 1 year under quasi-dynamic.

Figure 17.

Effect of Load growth over 5 year period.

Figure 17.

Effect of Load growth over 5 year period.

Figure 18.

KK II Solar PV Load forecast over 10 10-year period.

Figure 18.

KK II Solar PV Load forecast over 10 10-year period.

Figure 19.

Basic energy analysis results.

Figure 19.

Basic energy analysis results.

Figure 20.

Metro WF under Probabilistic analysis.

Figure 20.

Metro WF under Probabilistic analysis.

Figure 21.

Metro Wind Farm Annual load duration curve.

Figure 21.

Metro Wind Farm Annual load duration curve.

Table 1.

High RE Penetration Drivers.

Table 1.

High RE Penetration Drivers.

| Name |

Impact |

| Climate Change Mitigation [10]. |

Increasing RE penetration is driven by greenhouse gas reduction. |

| Policy and Regulation [11,12]. |

Government regulations, such as RE portfolio standards (RPS) and feed-in tariffs (FIT), have stimulated the expansion of renewable energy sources. |

| Cost Reductions [13]. |

Recently, solar PV panels, wind turbines, and battery storage devices have become cheaper, making renewables more viable. |

| Technological Advancements [14]. |

Power electronics, forecasting, and grid management innovations improve variable resource integration. |

Table 2.

South Africa’s Installed Power capacity.

Table 2.

South Africa’s Installed Power capacity.

| Installed power sources |

Installed capacity (MW) |

Installed capacity (%) |

| Thermal |

45489 |

78 |

| Gas |

2409 |

4 |

| Nuclear |

1840 |

3 |

| Wind |

2710 |

5 |

| Solar |

2323 |

4 |

| Hydro |

3393 |

6 |

Table 3.

RE concerns.

| Renewable Energy |

Uncertainty |

| Solar [27]. |

Local sun irradiance directly influences solar energy output, often managed by Beta. |

| Wind [28]. |

Wind velocity directly influences wind energy production, commonly modeled using the Weibull distribution. |

| Hydro [29]. |

Hydrological and hydraulic conditions influence hydropower plant production. |

Table 4.

Weibull curve parameters.

Table 4.

Weibull curve parameters.

| Parameter |

Value |

| Scale factor |

10m/s |

| Shape factor |

2 |

| Confidence level |

0.99999 |

| Wind speed step size |

0.1m/s |

Table 5.

Basic analysis of the wind farm.

Table 5.

Basic analysis of the wind farm.

| Basic Analysis |

| Average power of power park over a year |

11.3MW |

| Total annual net energy output at PoC |

98745MWh |

| Total Average electrical energy losses per year |

305.2MWh |

| Number of hours of the power park full load operation |

3668.5267 h |

| Loss of profit due to losses in feed-in operation |

15261.84 USD |

| profit |

4937249.24 |

Table 6.

probabilistic analysis of the wind farm.

Table 6.

probabilistic analysis of the wind farm.

| Probabilistic Analysis |

| Average power over a year |

11.27MW |

| Annual generation |

99007.2 MWh |

| Annual energy yield |

98703.9 MWh |

| Total Average Electrical energy losses per year |

303.3 MWh |

| Number of hours of power park full load operation |

3655.7001 h |

| Electrical losses (Price) |

15163.29 USD |

| Profit |

4935195.16 USD |