1. Introduction

Urban areas are increasingly facing challenges associated with water scarcity, climate change, and population growth (Biswas et al. 2025; Kuhlemann et al. 2021; McDonald et al. 2011; Samantha Kuzma et al. 2023; Liu et al. 2025; Qadir et al. 2007; Tzanakakis et al. 2020; Friedler 2008). These dynamics place considerable pressure on conventional freshwater resources, while the ecological and social significance of urban green spaces continues to grow (Ravinandrasana und Franzke 2025). Green infrastructure contributes to climate regulation, biodiversity conservation, and human well-being, but its sustainable irrigation remains a major challenge in residential district development (Liu und Jensen 2018; Cheshmehzangi et al. 2021). Conventional irrigation practices, which predominantly rely on potable water, are not ecologically or economically viable in the long term.

Greywater reuse has emerged as a promising approach to reduce freshwater demand and support the irrigation of urban vegetation (Hamidi 2025; Leung et al. 2012). Greywater, defined as lightly polluted wastewater from showers, sinks, and washing machines (UN-Water 2020), is generated in large quantities and can be treated to meet non-potable standards (Capodaglio 2020; Eriksson et al. 2002). While numerous pilot projects and studies have highlighted its ecological and economic potential (van de Walle et al. 2023; Friedler 2008; Tripathy et al. 2024; Rajski et al. 2024; Godfrey et al. 2009; Juan et al. 2016; Rodríguez et al. 2025; Jakhar und Styszko 2025; Yoonus und Al-Ghamdi 2020; Souza et al. 2025), implementation in residential district planning remains limited (van de Walle et al. 2023). A key obstacle is the absence of systematic, transparent tools that enable planners and developers to evaluate the feasibility and benefits of greywater reuse in specific contexts (Ni et al.; Morris et al. 2021; Weingärtner 2013; Abdelkarim et al. 2023; van Oijstaeijen et al. 2020).

One of the foundational frameworks used in this field of work is - Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) that offers a structured framework for evaluating greywater reuse options by balancing environmental, social, technical and economic criteria. In the context of greywater reuse for irrigation, MCDA helps policy makers assess trade-offs between factors such as sewage quality, crop suitability, cost efficiency, user acceptance and long-term sustainability. Recent studies have demonstrated its effectiveness in identifying optimal reuse configurations for agricultural applications and urban water management (Paul et al. 2021; Torre et al. 2024; Filho et al. 2025). By quantifying trade-offs and weighting stakeholder preferences, MCDA enables transparent, evidence-based choices that enhance resource efficiency while minimizing health and environmental risks.

This study develops a comprehensive evaluation matrix that assesses the potential of greywater reuse in residential district development. The matrix integrates regulatory, technical, infrastructural, ecological, economic, and social factors into a structured framework. Its purpose is to provide decision-makers with a practical, easy-to-use tool for evaluating site-specific conditions and guiding the planning process.

2. Background and Literature Review

2.1. Greywater Reuse in Urban Context

To enable the reuse of greywater, it is essential to consider the applicable legal and regulatory frameworks. In most jurisdictions, treated greywater is classified as service water (Betriebswasser), which may be applied in various contexts including private households, municipal facilities, and commercial settings (Oteng-Peprah et al. 2018). Typical uses include toilet flushing and laundry, but also irrigation of gardens, cemeteries, sports facilities, horticultural operations, and agricultural land (van de Walle et al. 2023; Hadad et al. 2022; Morseletto et al. 2022; Vuppaladadiyam et al. 2019). In addition, service water may serve functions such as vehicle cleaning, fire-fighting, cooling, or sewer flushing (Verein deutscher Ingenieure (VDI) 2013; Ringelstein 2023).

Table 1 summarizes the common application areas of service water.

Practical experience demonstrates that greywater reuse has been successfully implemented in a variety of settings, including office buildings, student and senior residences, hotels, multi-family housing, residential developments, camping sites, and municipal street-cleaning operations (Fachvereinigung Betriebs- und Regenwassernutzung e. V. (fbr) 2009; Sayegh et al. 2021; König 2013; INTEWA 2021; ANCHOR Interreg North Sea 2025; Stec et al. 2025; Stec 2023; van de Walle et al. 2023).

2.2. Legal Situation in Germany

In parallel, a comprehensive literature review about regulatory frameworks was examined. A key reference was the review by Shoushtarian und Negahban-Azar 2020, which summarizes regulatory approaches across several countries. In total, 27 relevant guidelines and regulations were identified and added to the database.

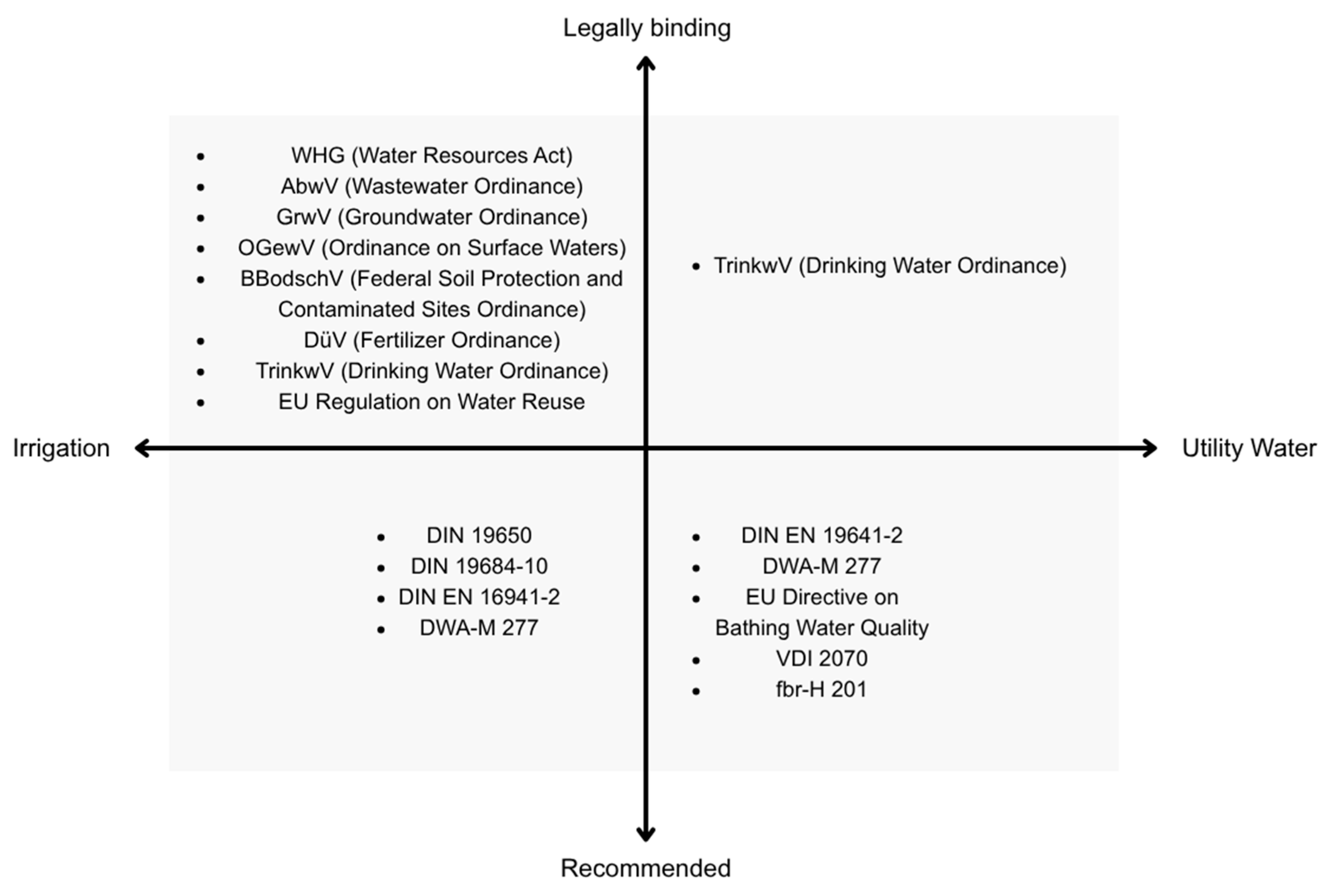

In many countries, the absence of a legal framework for greywater management impedes the development and implementation of reuse systems (van de Walle et al. 2023); likewise, in Germany, no overarching legal framework for greywater reuse currently exists. Instead, a complex system of binding laws, ordinances, and technical guidelines must be observed. While laws and ordinances are legally enforceable, norms and technical standards (such as DIN, DWA, or VDI guidelines) represent generally accepted rules of engineering practice and may gain binding force when explicitly referenced in legal texts. When treated greywater is applied as irrigation water, potential impacts on soils, plants, and consumers must be carefully assessed. This requires compliance with a broad range of environmental and health protection laws.

Figure 1 illustrates the regulatory instruments relevant to greywater reuse, particularly in the context of irrigation (Umweltbundesamt (UBA) 2016; Kohlhepp 2023). Selected ordinances are discussed in detail in order to highlight their relevance depending on the intended use and water quality requirements.

2.3. Treatment Requirements for Greywater as Irrigation Water in Germany

For the use of greywater as irrigation water, there are more advisory guidelines compared to other application purposes. The majority of these guidelines focus on the microbiological quality of the water, as shown in.

Table 2.

Overview of guidelines for greywater reuse by application (Kohlhepp 2023).

Table 2.

Overview of guidelines for greywater reuse by application (Kohlhepp 2023).

| Application for use as |

Regulation |

Microbiological parameters |

Physico-chemical parameters |

| Irrigation water |

EU Regulation 2020/741 (Europäische Union 2020): Minimum requirements for water reuse |

x |

x |

| DIN 19650 Hygienic aspects of irrigation water |

x |

|

| DIN 19684-10 Soil properties – Chemical laboratory tests – Part 10: Investigation and assessment of water in irrigation measures |

|

x |

| Irrigation water and utility water |

DIN EN 16941-2 On-site non-potable water supply systems – Part 2: Systems for the use of treated greywater |

x |

x |

| DWA-M 277 Guidelines for the design of plants for the treatment and use of greywater and greywater streams |

x |

x |

| Bathing water |

EU-Richtlinie 2006/7/EG 2006 Quality of bathing water and its management and repeal of Directive 76/160/EEC |

x |

|

At present, only the standard DIN EN 16941-2 explicitly addresses the use of greywater for irrigation and as service water. This standard applies to both irrigation and service water, defining microbiological as well as physico-chemical parameters. For service water applications, it additionally distinguishes between spray applications and non-spray applications. Due to the potential for aerosol formation, stricter requirements are imposed on spray applications, including parameters for Legionella. Furthermore, for service water, separate requirements are defined for laundry use and toilet flushing.

A direct comparison of the various guidelines for greywater reuse is often difficult, since different parameters are considered.

To ensure the safe use of greywater for both humans and the environment, appropriate protective measures should be derived from the results of a risk assessment for the respective application and use scenario. The following provides an overview of already established quality requirements for different usage scenarios, compiled from various standards and the EU Regulation on water reuse. Where requirements differed among sources, the most stringent requirement was adopted.

Table 3.

Compilation of the highest quality requirements from various guidelines by use type (Kohlhepp 2023; summarized from Europäische Union 2020; DIN 19650; DIN 19684-10; DIN EN 16941-2; DWA-M 277; EU-Richtlinie 2006/7/EG 2006).

Table 3.

Compilation of the highest quality requirements from various guidelines by use type (Kohlhepp 2023; summarized from Europäische Union 2020; DIN 19650; DIN 19684-10; DIN EN 16941-2; DWA-M 277; EU-Richtlinie 2006/7/EG 2006).

| Group |

Parameter |

Unit |

Irrigation (without Spraying) |

Toilet Flushing |

Laundry |

| Microbiological parameters |

Total coliforms |

CFU/100 ml |

< 1,000 |

< 1,000 |

10 |

| E. coli |

CFU/100 ml |

< 10 |

< 250 |

n/a |

| Intestinal enterococci |

CFU/100 ml |

< 100 |

< 100 |

n/a |

| P. aeruginosa |

CFU/100 ml |

< 100 |

< 100 |

< 100 |

| Faecal streptococci |

CFU/100 ml |

< 100 |

|

|

| Salmonella |

Count/1000 ml |

n/a |

|

|

| Legionella |

CFU/100 ml |

< 10 |

|

|

| Chemical-physical parameters |

O₂ saturation |

% |

> 50 |

> 50 |

> 50 |

| pH |

- |

6.5 to 9.5 |

6.5 to 9.5 |

6.5 to 9.5 |

| Turbidity |

NTU |

< 2 |

< 2 |

< 2 |

| BOD₅ |

mg/l |

< 5 |

< 5 |

< 5 |

| Chlorine |

mg/l |

< 0.5 |

< 2 |

< 2 |

| Bromine |

mg/l |

0 |

< 5 |

< 5 |

| TSS (Total suspended solids) |

mg/l |

< 10 |

|

|

| TDS (Total dissolved solids) |

mg/l |

< 500 |

|

|

| EC (Electrical conductivity) |

mS/cm |

< 0.3 |

|

|

| Salt |

g/l |

< 0.2 |

|

|

| SP (Sodium percentage) |

mmol/l |

< 60 |

|

|

| SAR (Sodium adsorption ratio) |

mmol/l |

< 6 |

|

|

| RSC (Residual sodium carbonate) |

mmol/l |

< 1.25 |

|

|

| Chloride |

mmol/l |

< 2 |

|

|

| Chloride |

mg/l |

< 70 |

|

|

| Boron |

mg/l |

0.3 to < 1 |

|

|

| Trace elements |

Aluminium |

mg/l |

0.5 |

|

|

| Arsenic |

mg/l |

0.1 |

|

|

| Lead |

mg/l |

0.1 |

|

|

| Boron |

mg/l |

1 |

|

|

| Cadmium |

mg/l |

0.01 |

|

|

| Chromium |

mg/l |

0.05 |

|

|

| Iron |

mg/l |

10 |

|

|

| Copper |

mg/l |

1 |

|

|

| Manganese |

mg/l |

1 |

|

|

| Molybdenum |

mg/l |

0.01 |

|

|

| Nickel |

mg/l |

0.5 |

|

|

| Mercury |

mg/l |

0.002 |

|

|

| Zinc |

mg/l |

2 |

|

|

For pollutants such as surfactants, antibiotic residues, and other pharmaceuticals, no threshold or guideline values have yet been defined in the cited sources. Similarly, most guidelines do not provide explicit requirements or fixed intervals for sampling frequency. Only Europäische Union 2020 (EU Regulation 2020/741) prescribes a minimum sampling frequency.

3. Methodology for Developing Evaluation Framework

MCDA comprises a set of decision-support approaches designed to address multi-objective problems (Belton und Stewart 2003). Its application has expanded considerably within the environmental sciences over the past decades (Paul et al. 2021; Torre et al. 2024; Daniel et al. 2023; Lienert et al. 2015; Huang et al. 2011; Bichai und Smeets 2015).

Gregory et al. 2012 identifies the initial phases of MCDA as (1) clarifying the decision context and (2) defining objectives and attributes.

3.1. Decision Context

The results of this research aimed to develop a comprehensive evaluation matrix for developers and planners addressing the irrigation of urban green spaces and the integration of greywater reuse. This evaluation matrix is intended to serve as a valuable tool for professionals in urban planning to implement sustainable and efficient practices in the management of water resources in urban green areas. With the evaluation matrix, potential developers are enabled to assess whether, and to what extent, their neighborhood is suitable for greywater reuse. The evaluation tool, which can be completed either by developers themselves or by a planner, has been designed for straightforward application through a simple scoring system, thereby allowing for a rapid preliminary assessment of potential. In addition, the framework allows for the integration of weighting, providing the option to place greater emphasis on specific criteria in line with stakeholder preferences and thereby enabling a more differentiated and context-sensitive evaluation.

3.2. Identifying Objectives and Attributes

This step involved a comprehensive review of studies to identify objectives and attributes for evaluating greywater utilization for irrigation of urban green spaces. These investigations focused on technical, economic, and legal aspects to establish a holistic approach for implementing sustainable water reuse practices.

The objectives of this review were - first, to review the legal frameworks in Germany in order to ensure compliance with water quality standards, greywater disposal regulations, and relevant building codes.

Secondly, the review aimed to assess existing and new building infrastructures with respect to storage, transport, and distribution capacities to ensure seamless integration.

Third, the objective was to assess greywater availability, which depends on the type of building or neighborhood use and the number of users. Greywater availability is further differentiated by source categories, since volumes may vary across substreams.

Fourth, the objective was to determine the required amount of greywater to be treated, derived from the intended use, because water demand varies according to specific uses. Fundamentally, only as much greywater should be treated as is approximately required.

Fifth, the objective was to ensure that treated greywater meets required quality standards by evaluating various treatment technologies—including filtration, disinfection, and membrane-based systems—with regard to both efficiency and applicability in residential contexts. In this context, we examined additional factors to optimize the integration of greywater in residential areas. These included (a) assessing water demand for urban green spaces to enable targeted and efficient allocation and (b) monitoring greywater quality with parameters suitable for AI-based processing and advanced indicators for continuous, adaptive oversight.

Sixth, the review aimed to assess the economic feasibility of greywater reuse by analyzing installation costs, potential freshwater savings, and associated environmental benefits, in order to derive actionable recommendations for households and commercial stakeholders.

Seventh, the objective was to address social acceptance within the community as a critical factor for the successful implementation of greywater reuse. Beyond technical, economic, and regulatory considerations, the long-term viability of such systems depends on the willingness of residents to adopt and support them.

These review steps established a complete understanding of potential and limitations for greywater reuse in urban contexts.

4. Results

The results of this study focus on the development of a comprehensive evaluation matrix designed to support developers and planners in assessing the potential for integrating greywater reuse into the irrigation of urban green spaces. The overarching goal was to provide a practical, scientifically grounded tool that enables professionals in urban planning to implement sustainable and efficient water management practices.

In the following sections, the results are presented in detail, beginning with the formulation of the objectives and the definition of the criteria for greywater reuse. The subsequent discussion elaborates on the scoring system and the role of weighting in refining the decision-making process. Furthermore, the research process revealed the necessity of including supplements to capture supplementary calculations, thereby ensuring transparency and traceability of the evaluation.

Together, these results provide both a methodological foundation and a practical decision-support tool for advancing the integration of greywater reuse in sustainable urban development.

4.1. Structure of the Evaluation Matrix

The evaluation matrix is designed to provide planners and developers with a transparent and systematic decision-support tool. Technical feasibility, economic viability, legal and regulatory compliance, ecological effects, and social acceptance were identified as decisive influencing factors within the literature review (Lück et al. 2025). These categories provided the foundation for structuring the evaluation matrix.

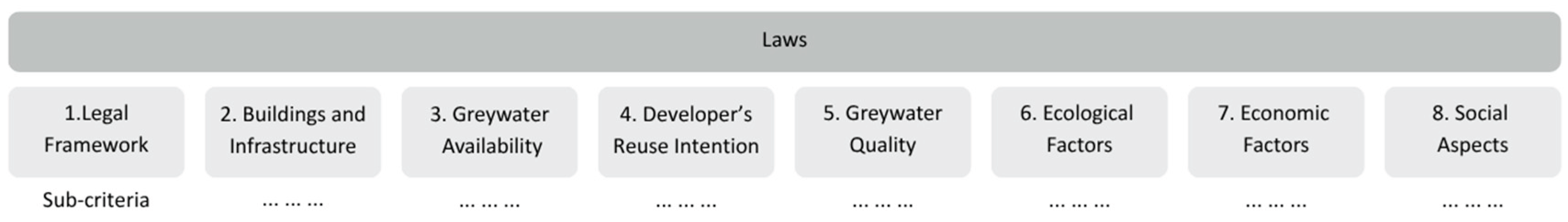

Figure 2.

Structure of the Evaluation Matrix.

Figure 2.

Structure of the Evaluation Matrix.

Each overarching categories of the evaluation matrix were subdivided into several sub-criteria that enable a detailed assessment of greywater reuse potential.

4.2. Weighting

Infrastructure projects are generally associated with multiple objectives that they are intended to serve. From the perspective of decision-makers, these sub-objectives may vary in urgency and importance. This can be expressed through the assignment of weights to the sub-objectives (Hillenbrand et al. 2018; Sartorius et al. 2016).

Weighting is often determined through surveys, for example, using methods based on the Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) (Saaty und Vargas 2013; Lück und Nyga 2017). In this study, the weighting of the main objectives by stakeholders (e.g., through pairwise comparison using AHP) could be incorporated into the model.

The category 1 “Legal Frameworks” was not included in the weighting, as it represents a knock-out criterion: if legal requirements cannot be fulfilled, the implementation of greywater reuse is not feasible.

Table 4 presents an example weighting of the seven categories of the evaluation matrix.

4.3. Scoring

For the evaluation process, a five-point Likert scale (Joshi et al. 2015; Koo und Yang 2025) was applied to ensure a standardized and transparent assessment of the defined criteria. The scale ranges from 1 to 5, where a score of 1 represents very low or no potential, and a score of 5 represents very high potential for greywater reuse. Intermediate values (2–4) allow for a nuanced differentiation of cases that do not fall at the extremes, thereby capturing gradual variations in suitability. The use of a Likert scale facilitates both comparability across criteria and the aggregation of results in the evaluation matrix. Furthermore, the scale is intuitive for practitioners, enabling its application not only by scientific experts but also by developers and planners with limited prior experience in greywater management.

Where additional data collection is necessary, supplement sheets are provided to assist users in completing the evaluation. Additionally, the criteria catalog provides detailed explanations, required data sources, and references to regulations. In this way, the tool allows both developers and planners to carry out systematic evaluations, ensuring comparability across projects

4.4. Detailed Description of Influencing Factors in the Evaluation Matrix

The evaluation matrix was designed to assess greywater reuse potential in residential districts in a transparent and replicable way. It combines the legal framework and further seven overarching categories and 26 criteria. Each category and its associated criteria are presented in detail in the following sections.

4.4.1. Category 1: Legal Aspects

The review of the legal and regulatory framework revealed that, while numerous applications for greywater reuse exist across private, municipal, and commercial contexts, the overarching legal situation in Germany remains fragmented. There is no single comprehensive regulation; instead, various laws, ordinances, and technical standards must be considered depending on the intended use.

A comparison of relevant guidelines shows that most regulatory attention is directed towards the microbiological quality of treated greywater, with fewer specifications addressing physicochemical parameters. Among the existing standards, DIN EN 16941-2 is the only one that explicitly targets greywater reuse for irrigation and service water, defining both microbiological and physicochemical requirements and distinguishing between applications with and without aerosol formation. In addition, the EU Regulation 2020/741 (Europäische Union 2020) provides minimum quality requirements and monitoring frequencies, though specific provisions for trace contaminants such as pharmaceuticals or surfactants remain absent. Overall, the analysis highlights the existence of multiple, partly overlapping frameworks with varying levels of detail, creating both opportunities and uncertainties for the practical implementation of greywater reuse in irrigation.

The legal framework category holds precedence over all other categories, since the feasibility of greywater reuse is fundamentally contingent upon its legal permissibility. The regulatory situation in this field is highly complex, involving numerous ordinances, standards, and technical guidelines. Consequently, an up-to-date legal review conducted by a qualified professional is strongly recommended.

Since different regulations apply depending on the type of greywater reuse, it is advisable that the other categories of the evaluation matrix are assessed first. In the initial application, it is therefore assumed that all legal requirements are fulfilled. Nevertheless, the legal framework is symbolically presented as the first criterion in both the catalog and the matrix, emphasizing its overriding importance.

Table 5.

Criteria of Category 1 with Scoring Options and Explanations, Data Sources and References (Kohlhepp et al. 2024).

Table 5.

Criteria of Category 1 with Scoring Options and Explanations, Data Sources and References (Kohlhepp et al. 2024).

4.4.2. Category 2: Building and Infrastructure

The feasibility of greywater reuse is strongly influenced by the condition of buildings, the availability of infrastructure for service water, and the space required for treatment systems. This category therefore comprises several criteria that assess both existing conditions and future adaptability.

Criterion 2.1: Condition of Buildings: Whether greywater reuse is feasible for the developer depends largely on the condition of the existing building and its piping system. In existing buildings, the installation of an additional wastewater pipeline is required. A complete renewal of the piping system may be sensible if the building is undergoing major renovation or full refurbishment.

Alternatively, state-of-the-art solutions from science and research can be considered, such as the use of a wastewater diverter or the retrofitting of an existing piping system by inserting a second pipe (Hörnlein et al. 2022).

The evaluation options for this criterion cover both new buildings or districts as well as existing structures. For existing buildings, the degree of renovation required plays an important role. This is reflected in the scoring categories, ranging from 2 (building with minor renovation needs) to 4 (complete renewal of the piping system required). Mixed forms combining new and existing buildings cannot be evaluated within this criteria catalog (see

Table 6).

Criterion 2.2: Infrastructure for Service Water: If the treated greywater is to be used as service water, an additional pipeline system is required alongside the potable water network. In some existing buildings, a non-potable water network may already exist due to previous rainwater use. This is considered in the evaluation. In certain cases, rainwater may in the future be infiltrated rather than used as service water in the building, or it may be supplemented with treated greywater.

In such scenarios, the existing non-potable water network can be modified and, if necessary, refurbished, significantly reducing effort and investment costs for the developer. It is also essential to assess whether a second piping system can be installed at all, given potential spatial, technical, or structural limitations. These aspects are reflected in the evaluation categories of this criterion.

Criterion 2.3: Available Space for Treatment: Depending on the chosen treatment technology, the required footprint for the installation can vary. For non-nature-based solutions in single buildings, an appropriately sized basement room is ideal, as it is better protected from external influences. Otherwise, a separate building or container for the installation must be constructed outside.

Nature-based systems require sufficient outdoor space, which must also be secured against external influences (e.g., fencing). In the evaluation categories, the availability of a sufficiently sized basement room is ranked more favorably than outdoor space, due to its advantages. The gradation is then determined by the specific spatial conditions (see

Table 6).

A first estimate of the required area can be made using a benchmark of 2 m² per m³ of treatment volume, as specified by ARIS 2023 for a fluidized bed reactor. This serves only as a rough guideline, since actual space requirements vary depending on the chosen treatment system.

All criteria in Category 2 must be assessed directly by the developer through their own estimation.

4.4.3. Category 3: Greywater Availability

Greywater availability depends on the type of use of the building or district as well as the number of users. In the criteria catalog, the number of users is represented in terms of inhabitants/ population equivalent (PE). This figure must either be estimated by the developer or derived from existing planning documents and then translated into the evaluation categories. The scoring system is designed such that the potential for greywater reuse increases with the number of inhabitants. For greywater treatment systems serving more than 50 IH, the highest score of 5 is assigned.

Greywater availability is further divided into criteria according to the different sources of greywater (Criterion 3.1 Showers/Bathtubs, Criterion 3.2 Washbasins, Criterion 3.3 Kitchen Sinks, Criterion 3.4 Dishwashers, Criterion 3.5 Washing Machines). This distinction is necessary because the volume of greywater varies depending on the specific sub-stream. In addition, the subdivision of individual greywater sub-streams is directly relevant for Criterion 5: Greywater Quality, where the source of greywater plays a decisive role in determining its suitability for reuse.

Table 7.

Criteria of Category 3 with Scoring Options and Explanations, Data Sources and References (Kohlhepp et al. 2024).

Table 7.

Criteria of Category 3 with Scoring Options and Explanations, Data Sources and References (Kohlhepp et al. 2024).

| 3. Greywater Availability |

|---|

| Criterion |

Assessment Options |

Explanation / Data Basis |

Source Reference |

3.1 Showers / Bathtubs

|

1 = 1–5 inhabitants (PE)

2 = 6–15 inhabitants (PE)

3 = 16–30 inhabitants (PE)

4 = 31–50 inhabitants (PE)

5 = more than 50 inhabitants (PE) |

The client (building owner) assesses greywater availability by indicating how many inhabitants (PE) contribute to each greywater substream.

This represents an evaluation by the client concerning the respective buildings within the neighborhood and the average occupancy per dwelling unit.

Since the volume of greywater differs significantly between substreams, the subcategories are weighted according to their share of the total greywater generation. This weighting cannot be altered. |

Average quantities of greywater by source (according to DWA-M 277) |

3.2 Washbasins

|

3.3 Kitchen sinks

|

3.4 Dishwashers

|

| 3.5 Washing machines |

4.4.4. Category 4: Intended Use

The intended use determines the volume of greywater that must be treated. Since water demand varies depending on the intended application, the different types of non-potable water use are divided into subcategories. Hence, the intended use of treated greywater can be evaluated under the following criteria: Criterion 4.1 service water for toilet flushing, Criterion 4.2 service water for washing machines, Criterion 4.3 service water for household cleaning, and Criterion 4.4 irrigation water for surrounding green areas and trees.

Similar to greywater availability, the required volume of non-potable water is assessed based on the number of inhabitants. For irrigation of green infrastructure, the evaluation is based on the number of trees and the square meters of green space to be irrigated. The scoring categories correspond to those used for greywater availability, with higher scores assigned as the number of users increases.

In principle, only as much greywater should be treated as is approximately needed for the intended use.

Table 8.

Criteria of Category 4 with Scoring Options and Explanations, Data Sources and References (Kohlhepp et al. 2024).

Table 8.

Criteria of Category 4 with Scoring Options and Explanations, Data Sources and References (Kohlhepp et al. 2024).

| 4. Developer’s Reuse Intention |

|---|

| Criterion |

Assessment Options |

Explanation / Data Basis |

Source Reference |

| 4.1 Use as service water for toilet flushing |

1 = 1–5 inhabitants / trees / m²

2 = 6–15 inhabitants / trees / m²

3 = 16–30 inhabitants / trees / m²

4 = 31–50 inhabitants / trees / m²

5 = more than 50 inhabitants / trees / m² |

The client (building owner) assesses the intended use by specifying for how many inhabitants (PE), trees, or square meters of green area the treated greywater is to be used.

This represents an evaluation by the client regarding the respective buildings in the neighborhood, the average occupancy per dwelling unit, as well as the number of relevant trees and the size of the green area. |

Average demand for service water (according to DWA-M 277)

Average irrigation demand for trees and green areas based on literature and empirical data |

| 4.2 Use as service water for washing machines |

| 4.3 Use as service water for household cleaning |

| 4.4 Use as irrigation water for surrounding green areas and trees |

4.4.5. Category 5: Greywater Quality

Greywater quality depends on the chosen greywater sub-stream. Based on the criterion 5.1 pollutant load, the appropriate treatment technology is selected in a later planning phase. Which sub-streams must be used depends on the balance between greywater availability and the intended reuse.

Ideally, it is sufficient to collect and treat lightly contaminated greywater from sanitary facilities. If more treated greywater is required, additional sub-streams must be included, which increases the pollutant load of the greywater.

With the help of Supplement 1 (Water Balance), it can be determined whether the available greywater is sufficient for the desired use and whether treatment of only the lightly contaminated sub-stream is adequate. The detailed functionality of Supplement 1 is explained in 0.

Following this assessment, the developer can evaluate the expected pollutant load (criterion 5.1) of the greywater to be reused. The evaluation distinguishes between very high, high, medium, low, and very low levels of contamination.

Table 9.

Criteria of Category 5 with Scoring Options and Explanations, Data Sources and References (Kohlhepp et al. 2024).

Table 9.

Criteria of Category 5 with Scoring Options and Explanations, Data Sources and References (Kohlhepp et al. 2024).

| 5. Greywater Quality |

|---|

| Criterion |

Assessment Options |

Explanation / Data Basis |

Source Reference |

| 5.1 Pollutant Load |

1 = very high contamination (e.g., greywater solely from washing machines and kitchens)

2 = high contamination (e.g., predominantly greywater from washing machines and kitchens)

3 = medium contamination (e.g., mixed greywater from all substreams)

4 = low contamination (e.g., from sanitary areas and washing machines or kitchens)

5 = very low contamination (e.g., from sanitary areas) |

Based on Criteria 3 and 4, a water balance must be prepared (use of Annex 1 – Water Balance is recommended).

Ideally, greywater availability from low-contamination substreams should exceed the required amount for the intended use, so that collection of highly contaminated substreams can be avoided.

If a large amount of treated greywater is needed, highly contaminated substreams may also be included. However, priority should be given to very low to moderately contaminated substreams. |

The detailed composition of the greywater is described in Chapter 4.3 of the present study. |

4.4.6. Category 6: Ecology

In order to assess the environmental conditions relevant for greywater reuse, three climate- and hydrology-related criteria were defined. These indicators reflect current challenges posed by climate change, droughts, and declining groundwater resources in Germany. Together, these criteria provide a structured basis for integrating climate variability and water resource stress into the evaluation matrix.

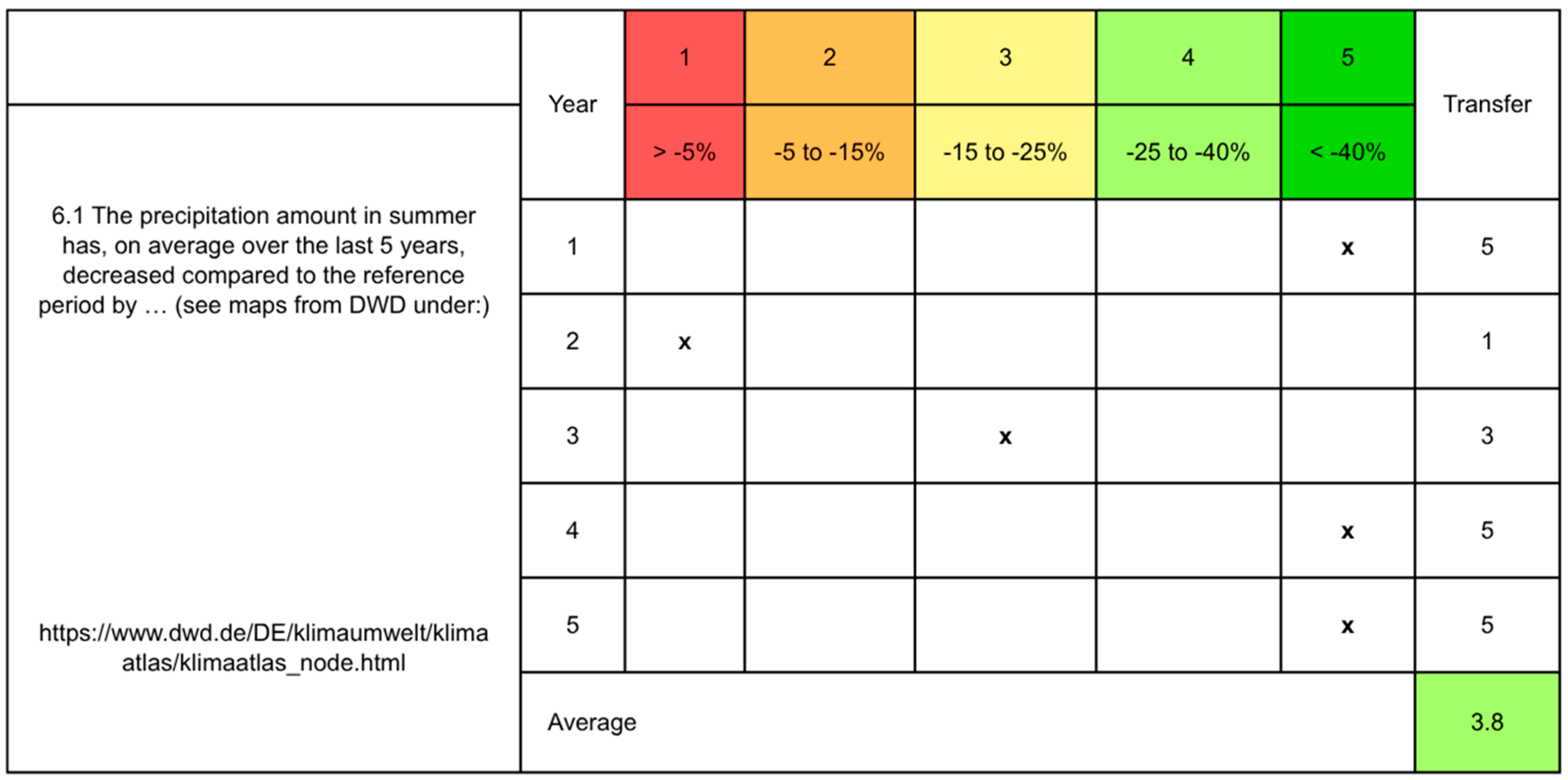

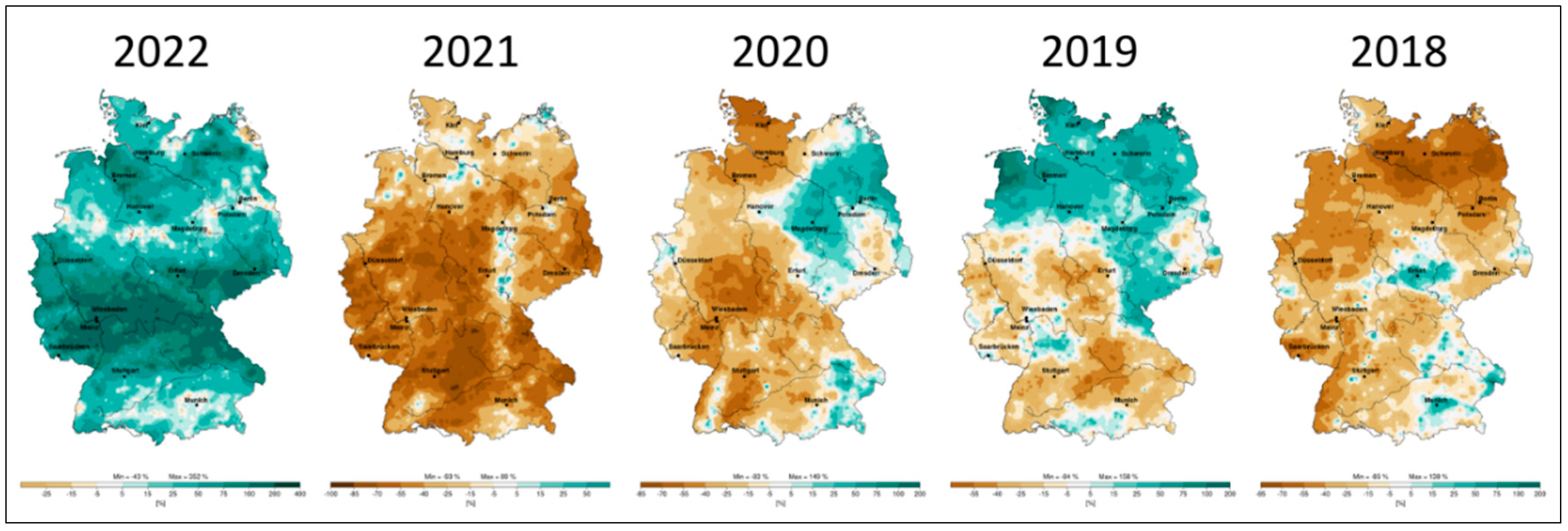

Criterion 6.1: Deviation of Summer Precipitation: In recent years, a noticeable shift in precipitation patterns has occurred, with rainfall increasingly concentrated in autumn and winter rather than in summer (Deutscher Wetterdienst (DWD) 2022b). Maps published by the German Weather Service (Deutscher Wetterdienst (DWD) 2022b) show the percentage deviation in precipitation compared to the reference period 1971–2000. These maps can be used to determine the changes in precipitation in the study area.

Because precipitation varies significantly from year to year, the last five years should be considered. To evaluate the individual years and calculate an average, Supplement 2 can be used (see for details section 0). This supplement includes DWD maps for the years 2018–2022. Where newer maps are required, a DWD web link (Deutscher Wetterdienst (DWD) 2022a) with the necessary settings is provided. The evaluation scale is based on the DWD map from 2020, which reflects mixed deviations in precipitation.

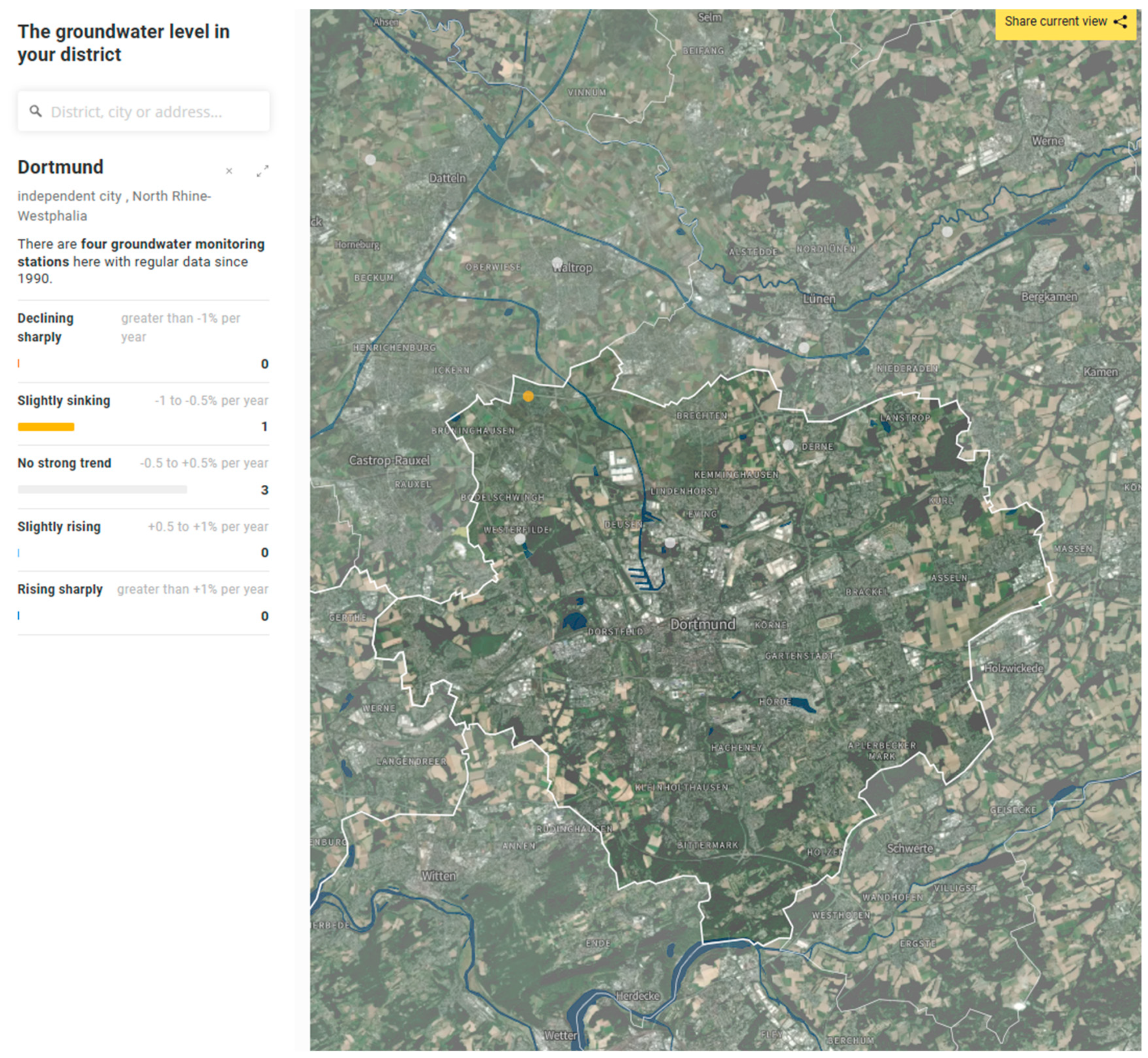

Criterion 6.2: Percentage of Declining Groundwater Levels in the Area: The proportion of declining groundwater levels is also an important indicator of the environmental situation in the study area. With the aid of the overview map available on the CORRECTIV 2023 website and Supplement 2, the developer can determine the percentage of measurement points where groundwater levels have decreased.

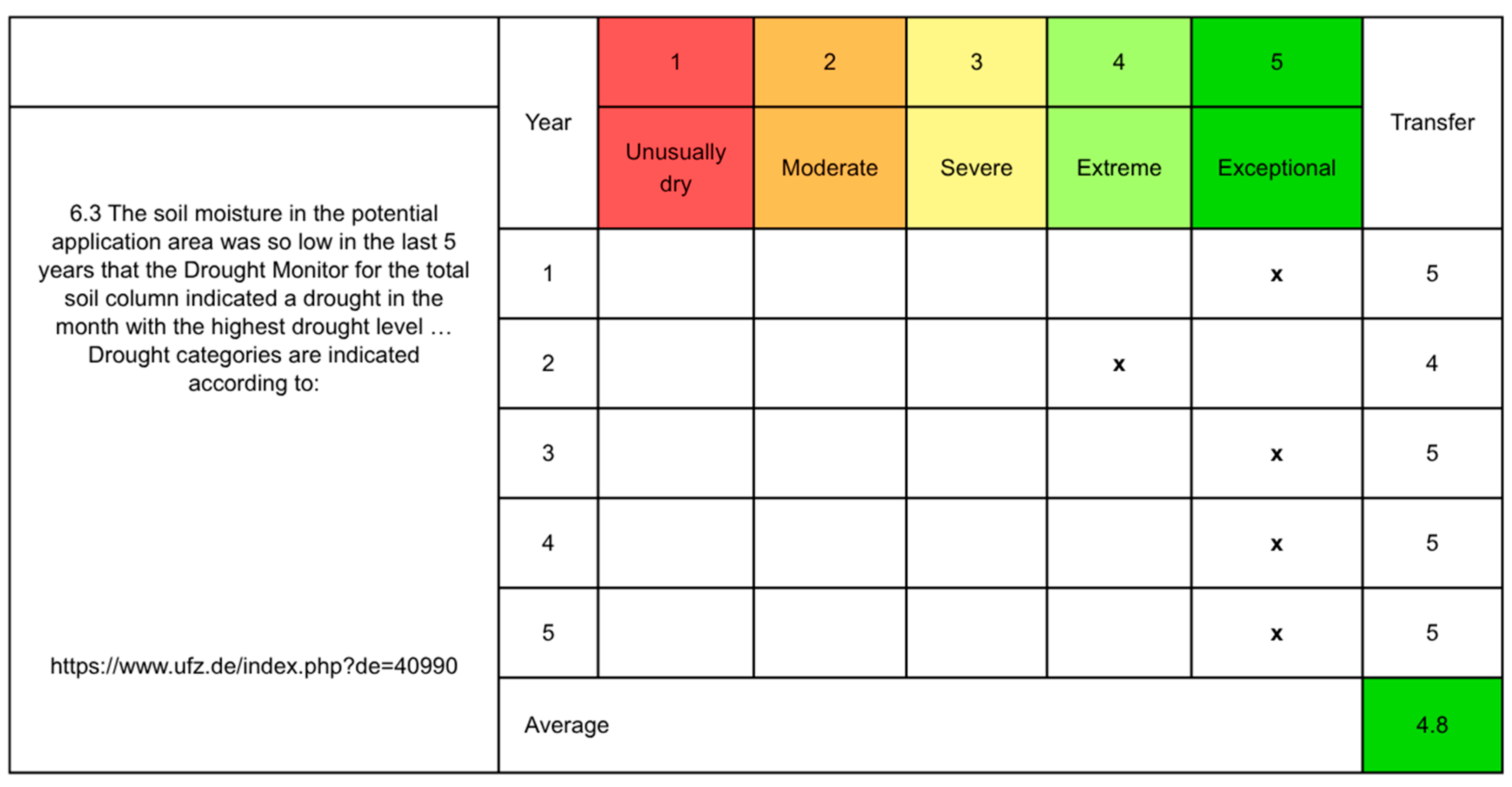

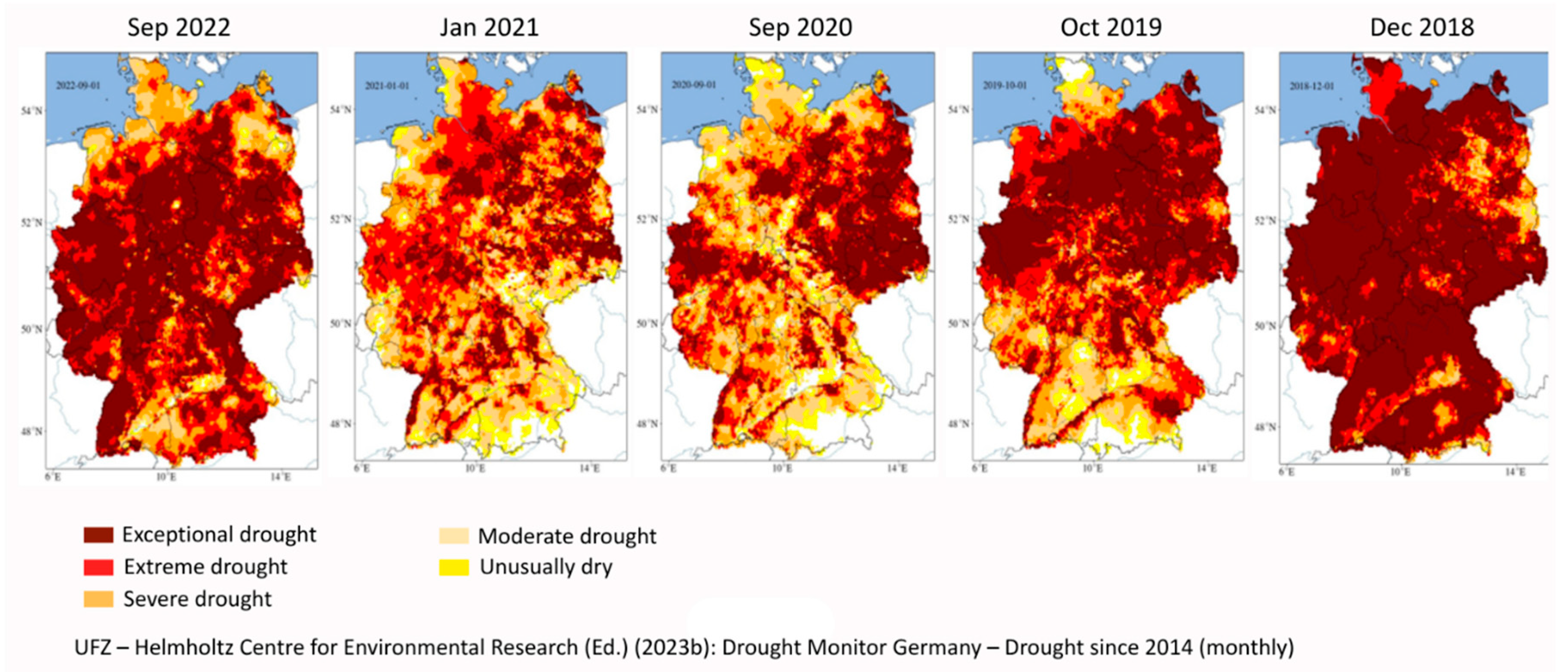

Criterion 6.3: Soil Moisture in the Last Five Years (Assessment of Drought): In recent years, Germany has experienced increasingly frequent droughts (Helmholtz Zentrum für Umweltforschung (UFZ) 2023b) . The UFZ Drought Monitor (Helmholtz Zentrum für Umweltforschung (UFZ) 2023a) provides maps that indicate the extent of drought conditions for each month of the year, allowing the developer to estimate drought severity in the study area for the past five years. For each year, the month with the most severe drought in the area must be selected by the developer.

This process is relatively demanding; therefore, Supplement 2 (see for details section 0) provides a table for recording interim values. The scaling of the evaluation categories corresponds directly to the classification used by the UFZ Drought Monitor (Helmholtz Zentrum für Umweltforschung (UFZ) 2023a).

Table 10.

Criteria of Category 6 with Scoring Options and Explanations, Data Sources and References (Kohlhepp et al. 2024).

Table 10.

Criteria of Category 6 with Scoring Options and Explanations, Data Sources and References (Kohlhepp et al. 2024).

| 6. Ecological Factors |

|---|

| Criterion |

Assessment Options |

Explanation / Data Basis |

Source Reference |

| 6.1 The amount of summer precipitation has decreased on average over the past 5 years compared to the reference period by … |

1 = > –5%

2 = –5% to –15%

3 = –15% to –25%

4 = –25% to –40%

5 = < –40% |

The maps provided by the DWD (example shown in Annex 2 Ecology, Section 2.1) indicate the percentage deviation from the reference period. The mean value of the relevant area can be assigned each year to one of the assessment categories in this criteria catalog. The average of the last five years is then calculated.

Alternatively, the online maps of the DWD (German Weather Service) can be used, which are available via the adjacent link. To obtain the correct maps, the following settings must be applied:

Element/Parameter: Precipitation

Type: Deviation

Year: Last 5 years

Month/Season: Summer |

https://www.dwd.de/DE/klimaumwelt/klimaatlas/klimaatlas_node.html |

| 6.2 The percentage of lowered groundwater levels in the area is … |

1 = < 5%

2 = 5–10%

3 = 10–20%

4 = 20–30%

5 = > 30% |

The adjacent link leads to the website of Correctiv, which provides an overview of groundwater level measurements in Germany in map form.

The relevant area must be selected, and the percentage of slightly and strongly decreasing groundwater levels in relation to the total number of measurement sites in the area must be calculated.

Annex 2 Ecology, Section 2.2 can also be used for this evaluation. The resulting percentage can then be compared with the assessment categories and entered accordingly into the evaluation matrix. |

https://correctiv.org/aktuelles/kampf-um-wasser/2022/10/25/klimawandel-grundwasser-in-deutschland-sinkt/?bbox=-2.932937931785631%2C45.200800967704936%2C24.2329379317853%2C55.79241409032102&zoom=4.716940586303015#tool |

| 6.3 In the potential application area, soil moisture has been so low in the past 5 years that the Drought Monitor has recorded a … during the month with the most severe drought |

1 = unusual dryness

2 = moderate drought

3 = severe drought

4 = extreme drought

5 = exceptional drought |

The maps provided by the UFZ (example maps in Annex 2 Ecology, Section 2.3) show, for each individual month, whether and to what extent drought occurred in recent years. Using these maps, it can be estimated which category the potential application area falls into. |

https://www.ufz.de/index.php?de=40990 |

4.4.7. Category 7: Economy

In addition to environmental aspects, economic conditions play a decisive role in evaluating the potential for greywater reuse. To capture these factors, six criteria were defined that reflect both external cost structures and the financial capacity of developers. Together, these indicators provide a comprehensive framework for linking cost dynamics and investment readiness with the feasibility of greywater reuse.

Criterion 7.1: Difference in Drinking Water Tariff: This criterion assesses the deviation of the local drinking water tariff compared to the national average. This provides an indication of whether greywater reuse has high or low potential. In 2022, the national average drinking water tariff in Germany was €1.83/m³ (Statistisches Bundesamt (DESTATIS) 2023).

Ideally, the developer should evaluate this criterion based on their contract with the local drinking water supplier. If no specific values are available, Supplement 3: Economy (see for details section 0) provides an approximate assessment by federal state, based on data from the Federal Statistical Office (Statistisches Bundesamt (DESTATIS) 2023). A link to the DESTATIS database is also included for access to more recent figures.

The scoring scale is based on calculated tariff differences in Supplement 3. Assuming an even distribution of 16 federal states across five categories, each scoring level corresponds to about 3.2 states. A difference of more than € 0.30/m³ places a state in the highest category, while lower differences are distributed evenly down to a positive deviation of less than € 0/m³.

Criterion 7.2: Percentage Increase in Drinking Water Costs in Recent Years: Unlike Criterion 7.1, this criterion evaluates the increase in drinking water tariffs over the past nine years. Again, local data should be used where possible. Otherwise, Supplement 3 provides data on cost increases per federal state. The classification of categories follows the same scheme as Criterion 7.1.

Criterion 7.3: Level of Wastewater Charges: Wastewater charges vary significantly depending on the regional wastewater association. Because of the high variability, no national reference values are available, so the absolute wastewater charge must be assessed.

The scoring scale is based on a linear interpolation of prices per cubic meter derived from the 2023 Wastewater Fee Ranking (IW Consult GmbH 2023). For a four-person household, annual wastewater charges range from €245.17 in Worms (equivalent to €1.34/m³) to €985.15 in Mönchengladbach (equivalent to €5.40/m³). The intermediate scoring levels in the matrix are calculated by linear interpolation between these extremes.

Criterion 7.4: Percentage Increase in Wastewater Charges in Recent Years: The percentage increase in wastewater charges must be determined from the actual fee statement of the local wastewater association. Due to the lack of consistent national data, the scoring scale for this criterion follows the same classification scheme as Criterion 7.2 (drinking water costs).

Criteria 7.5 and 7.6: Willingness to Invest and Cover Operating Costs: These criteria assess the willingness of the developer to invest in technologies with possibly longer amortization periods and to bear ongoing operating costs.

Because estimating actual investment and operating costs is highly complex—depending on system size, greywater quality, intended use, local conditions, and required treatment processes—the criteria are formulated in qualitative rather than quantitative terms. Scoring is thus based on the developer’s self-assessment of their readiness to allocate financial resources for investment and long-term operation.

Table 11.

Criteria of Category 7 with Scoring Options and Explanations, Data Sources and References (Kohlhepp et al. 2024).

Table 11.

Criteria of Category 7 with Scoring Options and Explanations, Data Sources and References (Kohlhepp et al. 2024).

| 7. Economic Factors |

|---|

| Criterion |

Assessment Options |

Explanation / Data Basis |

Source Reference |

| 7.1 The difference in drinking water charges compared to the national average currently amounts to … |

1 = ≤ 0.00

2 = 0.01–0.10

3 = 0.11–0.20

4 = 0.21–0.30

5 = > 0.30 |

This criterion assesses the difference between the actual local drinking water charge and the national average. The average drinking water price in 2022 was €1.83/m³.

Ideally, the local utility’s own cost statements for drinking water supply are used. Alternatively, the regional average values available from DESTATIS (Federal Statistical Office) can be referenced, categorized by federal state. The unit price must include the basic fee (€ per m³).

The relevant data for 2022 can be found in Annex 3 Economy, Section 3.1, or via the provided link to the current DESTATIS table.

As a reference to the national average, the DESTATIS table of current drinking water charges can also be used. |

https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Umwelt/Wasserwirtschaft/Tabellen/tw-08-entgelt-trinkwasserversorgung-tarifgeb-nach-tariftypen-2020-2022-land-bund.html |

| 7.2 Drinking water costs have increased between 2014 and 2022 (i.e., over the last 9 years) by … |

1 = < 0%

2 = 0–5%

3 = 5–10%

4 = 10–15%

5 = > 15% |

This criterion evaluates the actual price increase for drinking water from 2014 to 2022 (or the last nine years).

Ideally, own cost data from the local water supplier are used. Alternatively, the percentage increase can be derived from the regional averages available from DESTATIS, which list prices per m³ (including basic fee).

The relevant data can be found in Annex 3 Economy, Section 3.1 or accessed through the provided DESTATIS links. |

https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Umwelt/Wasserwirtschaft/Tabellen/tw-08-entgelt-trinkwasserversorgung-tarifgeb-nach-tariftypen-2020-2022-land-bund.html

https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Umwelt/Wasserwirtschaft/Tabellen/tw-06-entgelt-trinkwasserversorgung-tarifgeb-nach-tariftypen-2014-2016-land-bund.html

|

| 7.3 The wastewater charge amounts to … €/m³ |

1 = < 1.30

2 = 1.30–2.30

3 = 2.30–3.30

4 = 3.30–4.30

5 = > 4.30 |

Wastewater fees vary greatly depending on the responsible authority and local conditions. The total fee, including the basic charge, cannot be estimated using regional averages and must instead be determined using the local provider’s cost statements or obtained directly from the relevant authority (e.g., wastewater association).

The classification by €/m³ is based on the 2023 Wastewater Fee Ranking published by iW Consult (see source).

|

https://www.hausundgrund.de/sites/default/files/2023-06/Abwassergeb%C3%BChrenranking%202023%20Haus%20%26%20Grund%20Deutschland.pdf |

| 7.4 Wastewater costs have increased in the last 9 years by … |

1 = < 0%

2 = 0–5%

3 = 5–10%

4 = 10–15%

5 = > 15% |

Since wastewater charges differ greatly between providers, no uniform tables can be used. The percentage increase must be determined from the local utility’s cost records or requested from the relevant wastewater authority. |

Responsible wastewater authority |

| 7.5 I am … willing to invest in new technologies with a longer payback period |

1 = not willing

2 = rather not willing

3 = undecided

4 = rather willing

5 = willing |

The level of investment costs depends strongly on the treatment capacity, existing building structures, and the chosen treatment system. Data must be obtained directly from manufacturers if there is interest in greywater reuse. |

Treatment systems and their advantages/disadvantages, as well as system solutions, are presented in Guidebook Chapter 3.3.

|

| 7.6 I am … willing to invest in a technology with ongoing monthly operating costs |

1 = not willing

2 = rather not willing

3 = undecided

4 = rather willing

5 = willing |

Operating costs depend strongly on the chosen treatment system. Data must be obtained directly from manufacturers if there is interest in greywater reuse. |

Treatment systems and their advantages/disadvantages, as well as system solutions, are presented in Guidebook Chapter 3.3. |

4.4.8. Category 8: Social Aspects

Social factors are central to the successful implementation of greywater reuse. The acceptance and engagement of residents determine not only the feasibility of system integration but also its long-term sustainability. Four criteria were therefore defined: Criterion 8.1 addresses residents’ acceptance of greywater reuse, while Criterion 8.2 considers their willingness to engage with the technology in everyday life. Criterion 8.3 examines the implications for tenants’ utility costs, and Criterion 8.4 highlights the importance of residents’ well-being in relation to the maintenance of green spaces. Together, these indicators emphasize the role of social acceptance in shaping practical and user-oriented solutions for greywater reuse.

Criterion 8.1: Resident Acceptance of Greywater Reuse: Resident acceptance is a crucial factor, as the occupants are the end-users of the treated greywater and may come into direct contact with it. The assessment of this criterion can be based on the developer’s judgment or on surveys conducted among the affected residents.

Criterion 8.2: Willingness to Engage with the Technology: Ideally, tenants should be willing to engage with the technology of greywater treatment and understand its connection to their everyday practices. The developer can evaluate this willingness based either on personal assessment or by conducting surveys among residents.

Criterion 8.3: Level of Tenants’ Utility Costs: A positive social aspect of greywater reuse is the potential reduction of tenants’ utility costs. This criterion requires the developer to indicate whether operating costs (driven by drinking water and wastewater fees) have so far been passed on to tenants only minimally or to a significant degree.

Criterion 8.4: Well-being of Residents Due to Dried-Out Green Spaces: The well-being of residents can be enhanced by the presence of adequately maintained green spaces in their living environment. If these spaces dry out during summer, well-being may be negatively affected. This criterion therefore evaluates the extent to which green infrastructure would deteriorate without artificial irrigation.

Since no quantitative benchmark data could be identified for Category 8, the evaluation is conducted qualitatively, based on descriptive assessment rather than numerical values.

Table 12.

Criteria of Category 8 with Scoring Options and Explanations, Data Sources and References (Kohlhepp et al. 2024).

Table 12.

Criteria of Category 8 with Scoring Options and Explanations, Data Sources and References (Kohlhepp et al. 2024).

| 8. Social Aspects |

|---|

| Criterion |

Assessment Options |

Explanation / Data Basis |

Source Reference |

| 8.1 The residents’ acceptance of greywater reuse is … |

1 = not given

2 = rather not given

3 = neutral

4 = present

5 = fully present |

Assessment by the client (building owner) or based on a resident survey. |

... |

| 8.2 The residents’ willingness to engage with the technology is … |

1 = not given

2 = rather not given

3 = neutral

4 = present

5 = fully present |

Assessment by the client (building owner) or based on a resident survey. |

... |

| 8.3 The additional costs borne by residents in recent years, based on drinking and wastewater charges, were … |

1 = minimal

2 = rather low

3 = average

4 = slightly increased

5 = high |

Assessment by the client (building owner) with regard to the respective buildings within the neighbourhood. |

... |

| 8.4 Assessment of plants and green areas in relation to water shortage without additional irrigation, leading to a decline in tenant well-being |

1 = Green areas remain vital due to natural water balance

2 = Individual dry patches occur

3 = Increasingly dry patches occur

4 = The majority of the area is dried out

5 = Almost all green areas and hedges are dried out |

Assessment by the client (building owner). |

... |

4.5. Supplements to the Criteria Catalog

The supplements were developed to further simplify the application of the evaluation matrix. The following sections provide a detailed explanation of the three supplements on water balance (1), ecology (2), and economy (3).

4.5.1. Supplement 1: Water Balance

The first supplement automates the water balance that developers need to establish in order to determine the required greywater sub-streams. The only input required from the developer is the number of population equivalents (PE) for each greywater sub-stream and intended use. The daily greywater volume and the required amount of treated greywater for service water are then automatically calculated based on the reference values provided in DWA-M 277. Data for the irrigation of green areas and trees were derived as an example from part of a model neighborhood (Beyer et al. 2023).

At the end of the document, the supplement additionally verifies whether the generated greywater volume exceeds the greywater demand. The same verification is carried out specifically for lightly contaminated greywater.

Table 13.

Example of automatic calculation and verification of the water balance for 53 inhabitants (Kohlhepp 2023).

Table 13.

Example of automatic calculation and verification of the water balance for 53 inhabitants (Kohlhepp 2023).

| 3. Greywater availability |

| Greywater sub-stream |

Reference value

(DWA-M 277) |

Population Equivalent (PE) |

ltr/day |

| 3.1 Showers/bathtubs |

45.0 ltr/(PE x d) |

53 |

2,385 |

| 3.2 Handwash basins |

12.5 ltr/(PE x d) |

53 |

663 |

| Subtotal lightly polluted Greywater |

3,048 |

| 3.3 Kitchen sinks |

7.5 ltr/(PE x d) |

53 |

398 |

| 3.4 Dishwashers |

7.5 ltr/(PE x d) |

0 |

0 |

| 3.5 Washing machines |

12.5 ltr/(PE x d) |

53 |

663 |

| Subtotal heavily polluted Greywater |

1,060 |

| Total Greywater availability |

4,108 |

| 4. Developer’s Reuse Intention |

| Type of use |

Reference value

(DWA-M 277) |

Population Equivalent (PE) |

ltr/day |

| 4.1 As service water for toilet flushing |

33.0 ltr/(PE x d) |

53 |

1,749 |

| 4.2 As service water for washing machine |

15.0 ltr/(PE x d) |

0 |

0 |

| 4.3 As service water for household cleaning |

7.0 ltr/(PE x d) |

0 |

0 |

| Subtotal service water |

3,048 |

| 4.4 As irrigation water for trees |

20.0 ltr/(tree x d) |

17 |

340 |

| 4.4 As irrigation water for green areas |

7.5 ltr/(m2 green area x d) |

1560 |

1,092 |

| Subtotal irrigation water |

1,432 |

| Total usage demand |

3,181 |

4.5.2. Supplement 2: Ecology

The second supplement can be applied to all three ecological criteria (6.1 to 6.3).

Criterion 6.1: Deviation of Summer Precipitation: For the deviation in summer precipitation over the past five years, the percentage deviation must be read from the DWD maps (Deutscher Wetterdienst (DWD) 2022a). The supplement provides a table (Table 6) for recording the intermediate results for each year. In addition, the average rating is automatically calculated and displayed in the corresponding evaluation color, which then needs to be transferred into the criteria catalog.

Table 14.

Development of summer precipitation amounts compared to the reference period (Kohlhepp 2023).

Table 14.

Development of summer precipitation amounts compared to the reference period (Kohlhepp 2023).

On supplement 2, the DWD maps for the years 2018 to 2022 are already integrated (Deutscher Wetterdienst (DWD) 2022a). To maintain clarity, the maps are presented as small figures (see

Figure 3).

When the cursor is placed below a respective map in the Excel sheet, the image enlarges, allowing the percentage deviation to be conveniently read for the specific location. In addition, the maps can also be accessed via an attached link.

Criterion 6.2: Percentage of Declining Groundwater Levels in the Area: Criterion 6.2 can also be evaluated with the support of supplement 2. Using the overview map provided by CORRECTIV 2023, groundwater monitoring points in the affected area can be displayed. By clicking on the respective area with the cursor, more detailed information on the monitoring stations is revealed, as illustrated in

Figure 4.

The number of groundwater monitoring stations in the respective categories—strongly declining, slightly declining, no significant trend, slightly increasing, and strongly increasing—can then be transferred into supplement 2. The percentage share of declining monitoring stations is automatically calculated, and the corresponding evaluation color is displayed in the background. As in the previous case, a direct link to the online tool is included in supplement 2 (see

Table 7).

Table 15.

Automatic calculation of the shares of slightly and strongly declining groundwater levels (Kohlhepp 2023).

Table 15.

Automatic calculation of the shares of slightly and strongly declining groundwater levels (Kohlhepp 2023).

Criterion 6.3: Soil Moisture in the Last Five Years (Drought Assessment): The procedure for determining soil moisture follows the same approach as for Criterion 6.1. When retrieving the maps via the provided link, one map must be selected per year from the twelve available, identifying the month in which the assessed area experienced the driest conditions.

Figure 5 illustrates this procedure for the years 2018 to 2022 as an example.

The severity of drought for each year can then be recorded in the overview table (see

Table 8). As with the other criteria, the average value is automatically calculated.

Table 16.

Table for recording intermediate values from the Drought Monitor from Helmholtz Zentrum für Umweltforschung (UFZ) 2023a (Kohlhepp 2023).

Table 16.

Table for recording intermediate values from the Drought Monitor from Helmholtz Zentrum für Umweltforschung (UFZ) 2023a (Kohlhepp 2023).

4.5.3. Supplement 3: Economy

In supplement 3, the developer is not required to provide any additional information, as this sheet serves solely as supplementary reference material. It contains the average drinking water prices per federal state for the years 2014 and 2022, as well as the deviation of these prices from the national average and the percentage increase or decrease in drinking water tariffs over the past nine years. These values can be used as supporting information for the evaluation of Criteria 7.1 and 7.2. However, actual data from local water suppliers should be prioritized whenever available.

Table 17.

Compilation of drinking water charges and price development (Kohlhepp 2023; based on data from Statistisches Bundesamt (DESTATIS) 2023).

Table 17.

Compilation of drinking water charges and price development (Kohlhepp 2023; based on data from Statistisches Bundesamt (DESTATIS) 2023).

| |

Year |

Criterion 7.1 |

Criterion 7.2 |

Federal

State |

2022 |

2014 |

Deviation of the drinking water charge from the national average by federal states in 2022 |

Rating number |

Percentage increase/decrease of the drinking water charge from 2014 to 2022 |

Rating number |

| Germany |

1.83 |

1.69 |

0.00 |

... |

8.3 |

... |

| Baden-Württemberg |

2.33 |

2.0 |

0.50 |

5 |

14.2 |

4 |

| Bavaria |

1.78 |

1.48 |

-0.05 |

1 |

20.3 |

5 |

| Berlin |

1.81 |

1.81 |

-0.02 |

1 |

0.0 |

1 |

| Brandenburg |

1.57 |

1.53 |

-0.26 |

1 |

2.6 |

2 |

| Bremen |

2.44 |

1.98 |

0.61 |

5 |

23.2 |

5 |

| Hamburg |

1.93 |

1.77 |

0.10 |

2 |

9.0 |

3 |

| Hesse |

2.16 |

1.97 |

0.33 |

5 |

9.6 |

3 |

| Mecklenburg-Vorpommern |

1.60 |

1.61 |

-0.23 |

1 |

-0.6 |

1 |

| Lower Saxony |

1.43 |

1.22 |

-0.40 |

1 |

17.2 |

5 |

| North Rhine-Westphalia |

1.64 |

1.65 |

-0.19 |

1 |

-0.6 |

1 |

| Rhineland-Palatinate |

1.82 |

1.70 |

-0.01 |

1 |

7.1 |

3 |

| Saarland |

2.00 |

1.88 |

0.17 |

3 |

6.4 |

3 |

| Saxony |

2.01 |

1.94 |

0.18 |

3 |

3.6 |

2 |

| Saxony-Anhalt |

1.75 |

1.73 |

-0.08 |

1 |

1.2 |

2 |

| Schleswig-Holstein |

1.57 |

1.44 |

-0.26 |

1 |

9.0 |

3 |

| Thuringia |

2.08 |

2.00 |

0.25 |

4 |

4.0 |

2 |

4.6. Overview of Results

This study delivers a practical, scientifically grounded evaluation matrix to assess the potential for integrating greywater reuse into the irrigation of urban green spaces. The matrix operationalizes decision-making across eight domains: a knock-out legal category (whose non-compliance precludes implementation) and seven weighted categories covering buildings and infrastructure, greywater availability, intended use, greywater quality, ecological conditions, economic factors, and social aspects. The structure supports transparent, replicable appraisal by planners and developers.

A weighting option aligns the matrix with stakeholder priorities (e.g., via AHP-based pairwise comparison), while keeping Category 1 (Legal) outside the weighting as an exclusion criterion. Criterion-level scores are aggregated using a five-point Likert scale (1–5), where 1 denotes no or very low potential and 5 denotes very high potential; intermediate values capture gradations in suitability. To ensure usability, the tool employs a checkbox format and is accompanied by a criteria catalog specifying definitions, data needs, and normative references, thereby enhancing consistency and transparency across projects.

Three supplements streamline application: (1) an automated water balance to match greywater substreams with intended uses; (2) an ecology sheet to compile five-year summaries of summer precipitation deviations, groundwater-level trends, and drought severity; and (3) an economy sheet providing reference tariffs and tariff trends (while prioritizing local utility data). Collectively, the matrix, weighting option, scoring scheme, and supplements furnish a coherent results package that supports rapid screening, stakeholder-sensitive prioritization, and traceable documentation for the integration of greywater reuse in sustainable urban development.

4.7. Case Studies

4.7.1. Case Study 1: Micro-Apartments in Bergmannsgrün (Dortmund, Huckarde)

The evaluation matrix was applied to a planned new-build comprising ~53 micro-apartments within the Bergmannsgrün model district, a showcase project for the IGA 2027 emphasizing climate mitigation/adaptation, energy, and sustainable materials. Based on the developer’s reuse intention (VIVAWEST), treated greywater is primarily designated for irrigating surrounding green spaces (≈2,740 m² and 17 trees), with toilet flushing considered as a stabilizing year-round demand. Assuming one resident per unit, showers/handbasins/kitchen sinks and shared laundry yield high greywater availability (>50 PE per substream). Buildings & infrastructure score highly due to new-build planning and dual piping, while available plant space is rated moderate given basement/outdoor uncertainties. A water-balance supplement indicates that lightly polluted substreams alone do not entirely meet peak demand; adding the kitchen substream raises expected pollutant load (Category 4) but secures supply. Ecological indicators (five-year summer precipitation deficits, groundwater declines, and drought severity) yield a strong ecology score (≈4.3). Economic factors score low under state-level tariff proxies, though sensitivity tests show that using local tariff data (including base fees) can materially improve the “Investor” scenario. Social criteria are favorable given the district’s sustainability profile and ongoing resident engagement. Unweighted, the case returns an overall potential of ~3.8 (high), and scenario analyses (“Sustainability,” “Investor,” “User Well-being,” “Mixed Interests”) demonstrate that outcomes are particularly sensitive to economic inputs and to how seasonal irrigation demand is complemented by year-round uses (e.g., WC flushing).

Table 18.

Overview of results across the four scenarios in Dortmund (Kohlhepp 2023).

Table 18.

Overview of results across the four scenarios in Dortmund (Kohlhepp 2023).

| Category |

Sustainability |

Investor |

User benefit |

Mixed interests |

Without weighting |

| 2. Buildings and infrastructure |

15.0% |

20.0% |

12.5% |

20.0% |

14.3% |

| 3. Greywater availability |

15.0% |

5.0% |

5.0% |

20.0% |

14.3% |

| 4. Developer’s Reuse Intention |

15.0% |

10.0% |

20.0% |

10.0% |

14.3% |

| 5. Greywater quality |

5.0% |

5.0% |

10.0% |

12.5% |

14.3% |

| 6. Ecological Factors |

35.0% |

5.0% |

10.0% |

12.5% |

14.3% |

| 7. Economic Factors |

5.0% |

40.0% |

10.0% |

15.0% |

14.3% |

| 8. Social Aspects |

10.0% |

15.0% |

32.5% |

10.0% |

14.3% |

| Overall result |

4.0 |

3.4 |

3.6 |

3.9 |

3.8 |

| Deviation compared to without weighting |

0.2 |

-0.4 |

-0.2 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

Table 19.

Excerpt from the evaluation scale for results.

Table 19.

Excerpt from the evaluation scale for results.

| From |

To |

Potential Assessment |

| 2.5 |

< 3.5 |

Potential is moderate |

| 3.5 |

< 4.5 |

Potential is high |

4.7.2. Case Study 2: Reference Building in Weimar

To contextualize results, the matrix was transferred to an existing six-storey apartment block (pre-renovation baseline) in Weimar where mixed greywater from 11 units is already collected in a constrained basement. Under conservative assumptions (partial retrofitting complexity, limited space, no pre-existing service-water network), Buildings & infrastructure score lower than in the Dortmund case; greywater availability reflects ~22 residents with mixed appliance penetration. Intended use prioritizes WC flushing and laundry; pollutant load is favorable (primarily sanitary substreams), yielding a high greywater-quality score (5). Ecology is derived from DWD/UFZ/Correctiv sources for Weimar (mid-to-high scores across the three indicators). Economic scoring relies on state-level references (with local wastewater charges ~€1.75/m³ incl. base fee), and social criteria are assessed qualitatively. Across all four weighting scenarios, the Weimar object exhibits a moderate reuse potential, lower than Bergmannsgrün, with a wider spread among category scores (strong in quality, weak in intended use). Comparative sensitivity analysis indicates that (i) category divergences amplify weighting effects, (ii) robust local cost data (rather than state averages) are essential to avoid biasing economic outcomes, and (iii) refining the intended-use criterion to account for the ratio of demand to availability and intra-annual demand variability (e.g., irrigation seasonality) would improve discriminatory power and practical relevance of the matrix.

Table 20.

Overview of results across the four scenarios in Weimar (Kohlhepp 2023).

Table 20.

Overview of results across the four scenarios in Weimar (Kohlhepp 2023).

| Scenario |

Sustainability |

Investor |

User benefit |

Mixed interests |

Without weighting |

| Overall result |

3.2 |

2.8 |

2.9 |

3.1 |

3.1 |

| Deviation from unweighted result |

0.1 |

- 0.3 |

- 0.2 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

5. Discussion

This study proposes and tests a transparent, MCDA-based evaluation matrix to appraise the potential for integrating greywater reuse into the irrigation of urban green spaces in residential developments. By operationalizing eight domains—one legal knock-out category and seven assessable categories (buildings/infrastructure, availability, intended use, quality, ecology, economy, social)—the matrix translates a diffuse, multi-dimensional decision problem into a structured, traceable appraisal. The two case studies demonstrate that the framework is applicable to both new-build and existing contexts, supports early-stage screening, and highlights the trade-offs inherent in technical integration, seasonal demand, and stakeholder priorities.

A central insight is the primacy of legal permissibility. Treating the regulatory context as a knock-out category is appropriate because non-compliance makes any subsequent optimization moot. At the same time, the fragmented and evolving nature of standards implies that legal feasibility is time- and use-specific. Consequently, the requirement for an up-to-date, expert legal review should be retained as a procedural safeguard, and the matrix should be read as conditional on current compliance for the specified application (e.g., irrigation with/without aerosol formation).

The weighting mechanism proves valuable for embedding stakeholder preferences (e.g., via AHP pairwise comparisons) but also reveals sensitivity of outcomes to value judgements and data inputs. In Dortmund (Bergmannsgrün), scenario analyses (“Sustainability,” “Investor,” “User Well-being,” “Mixed Interests”) show that results shift notably when economic criteria are emphasized and when local tariffs (including base fees) replace state averages. In Weimar, a wider dispersion among category scores amplifies the effect of weight changes. These findings underscore the importance of (i) eliciting weights through a transparent participatory process, (ii) reporting robustness checks (e.g., one-way sensitivity, weight-swing analysis, or Monte-Carlo simulation over plausible weight intervals), and (iii) prioritizing project-specific data over proxy values wherever feasible.

Methodologically, the five-point Likert scoring enables consistent aggregation and comparability across diverse criteria while remaining accessible to practitioners. Nonetheless, the case studies highlight two refinements that would improve discriminative power and practical relevance. First, for intended use, scoring should incorporate the ratio of demand to availability and explicitly account for intra-annual variability (e.g., irrigation seasonality), acknowledging that biological treatment systems cannot be cycled off without cost or risk. Second, for availability, kitchen sinks and dishwashers could be combined into a single “kitchen” substream to better reflect compensating behaviors (absence of a dishwasher typically increases sink usage). These targeted adjustments would reduce structural bias and better align the matrix with operational realities.

The supplements are instrumental for transparency and reproducibility. The automated water-balance worksheet reduces calculation errors and clarifies the implications of adding (or avoiding) higher-load substreams for meeting demand. The ecology supplement operationalizes climate- and hydrology-relevant evidence (summer precipitation anomalies, groundwater trends, drought severity) over a five-year window, supporting site-adaptive interpretation rather than single-year snapshots. The economy supplement is helpful for first-pass screening, but the Dortmund analysis shows that relying on regional averages can misclassify projects; thus, local utility tariffs and fee structures should be obtained early and documented in the annexes to prevent systematic bias.

From a planning perspective, the matrix has three practical implications. First, it enables early design moves that stabilize system performance—e.g., pairing seasonal irrigation with year-round uses (toilet flushing) to maintain steady loading, protect process stability, and right-size storage. Second, it makes explicit the quality–technology linkage: maximizing lightly polluted substreams can reduce treatment stringency, energy use, and O&M costs, while still meeting non-potable standards. Third, the social dimension—resident acceptance and engagement—is not merely contextual but a determinant of long-term viability; structured communication and feedback loops should therefore be embedded in project governance and reflected in weighting where appropriate.

Several limitations merit attention. The current scoring does not yet integrate health risk assessment (e.g., Quantitative Microbial Risk Assessment (QMRA)) or life-cycle environmental impacts (LCA) (e.g., energy use, chemical consumption, and sludge management) of treatment options; future work should therefore couple the matrix with streamlined LCA and QMRA modules.Uncertainty is handled implicitly through sensitivity of weights and scenario testing; extending the approach with probabilistic ranges for key inputs (demand factors, tariff trajectories, drought frequency) would strengthen decision confidence. Finally, although the framework is developed for Germany, its structure is transferable; however, legal and quality requirements are jurisdiction-specific and must be re-parameterized accordingly.

In sum, the proposed evaluation matrix advances decision support for greywater reuse by combining legal feasibility, technical/infrastructural fit, environmental context, economic viability, and social acceptance within a single, usable instrument. The case studies confirm its diagnostic value and reveal where refinements—demand/availability ratios, seasonality handling, consolidated substreams, stronger local data—can enhance accuracy. With these enhancements and the addition of explicit risk and life-cycle modules, the matrix can provide a robust basis for evidence-based, stakeholder-sensitive planning of greywater reuse in ecologically oriented urban development.

6. Conclusions

This study developed and tested an MCDA-based evaluation matrix to assess the potential for integrating greywater reuse into the irrigation of urban green spaces in residential developments. The evaluation matrix enables systematic, transparent, and user-friendly assessment of reuse potential. The framework consolidates a legal knock-out category with seven assessable domains—buildings/infrastructure, greywater availability, intended use, greywater quality, ecology, economy, and social aspects—enabling transparent, replicable screening at early planning stages. Application to two contrasting cases (a new-build micro-apartment project and an existing multi-storey building) showed that the matrix is practicable, discriminative, and sensitive to local context. Results highlight three core insights: (i) legal permissibility is a prerequisite and must be verified with up-to-date expertise; (ii) economic inputs (especially locally specific tariffs and fee structures) strongly influence outcomes and should replace regional proxies wherever possible; and (iii) technical-infrastructural design benefits from pairing seasonal irrigation demands with year-round uses (e.g., toilet flushing) to stabilize operation and sizing. The supplements (water balance, ecology, economy) improved transparency and reduced calculation errors. Collectively, the matrix and materials provide a usable decision-support instrument that links scientific evidence with planning practice and stakeholder preferences.

For urban planners, housing developers, and policymakers, the evaluation matrix offers a practical instrument to assess the feasibility of greywater reuse in district development at an early stage. Its structured criteria enable transparent comparison across projects and provide a clear basis for decision-making. The matrix can support permit procedures, guide infrastructure planning, and foster stakeholder acceptance by presenting results in an accessible way. For practitioners, the combination of a straightforward scoring system with automated processes reduces complexity and facilitates integration into existing planning workflows. By ensuring adaptability to local conditions, the matrix also strengthens the potential for scaling greywater reuse across diverse urban contexts.

7. Outlook

Future work should strengthen and expand the presented framework along five complementary directions.

First, risk and sustainability analytics: The evaluation matrix should be coupled with quantitative risk and sustainability assessments, such as simplified Quantitative Microbial Risk Assessment (QMRA) for health protection and Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) or Techno-Economic Analysis (TEA) for environmental and economic performance. This would allow planners and policymakers to assess long-term trade-offs between safety, cost, and ecological benefit, thereby enhancing evidence-based decision-making.

Second, data quality and uncertainty management: To improve robustness, future applications should incorporate site-specific data instead of regional averages, supported by explicit treatment of uncertainty (e.g., sensitivity analyses, confidence intervals, or probabilistic scoring). Moreover, dynamic weighting mechanisms could be introduced to adapt to shifting stakeholder priorities and evolving socio-environmental conditions.